Abstract

Background

Parent‐infant psychotherapy (PIP) is a dyadic intervention that works with parent and infant together, with the aim of improving the parent‐infant relationship and promoting infant attachment and optimal infant development. PIP aims to achieve this by targeting the mother’s view of her infant, which may be affected by her own experiences, and linking them to her current relationship to her child, in order to improve the parent‐infant relationship directly.

Objectives

1. To assess the effectiveness of PIP in improving parental and infant mental health and the parent‐infant relationship.

2. To identify the programme components that appear to be associated with more effective outcomes and factors that modify intervention effectiveness (e.g. programme duration, programme focus).

Search methods

We searched the following electronic databases on 13 January 2014: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, 2014, Issue 1), Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, BIOSIS Citation Index, Science Citation Index, ERIC, and Sociological Abstracts. We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials, checked reference lists, and contacted study authors and other experts.

Selection criteria

Two review authors assessed study eligibility independently. We included randomised controlled trials (RCT) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (quasi‐RCT) that compared a PIP programme directed at parents with infants aged 24 months or less at study entry, with a control condition (i.e. waiting‐list, no treatment or treatment‐as‐usual), and used at least one standardised measure of parental or infant functioning. We also included studies that only used a second treatment group.

Data collection and analysis

We adhered to the standard methodological procedures of The Cochrane Collaboration. We standardised the treatment effect for each outcome in each study by dividing the mean difference (MD) in post‐intervention scores between the intervention and control groups by the pooled standard deviation. We presented standardised mean differences (SMDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for continuous data, and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous data. We undertook meta‐analysis using a random‐effects model.

Main results

We included eight studies comprising 846 randomised participants, of which four studies involved comparisons of PIP with control groups only. Four studies involved comparisons with another treatment group (i.e. another PIP, video‐interaction guidance, psychoeducation, counselling or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)), two of these studies included a control group in addition to an alternative treatment group. Samples included women with postpartum depression, anxious or insecure attachment, maltreated, and prison populations. We assessed potential bias (random sequence generation, allocation concealment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, and other bias). Four studies were at low risk of bias in four or more domains. Four studies were at high risk of bias for allocation concealment, and no study blinded participants or personnel to the intervention. Five studies did not provide adequate information for assessment of risk of bias in at least one domain (rated as unclear).

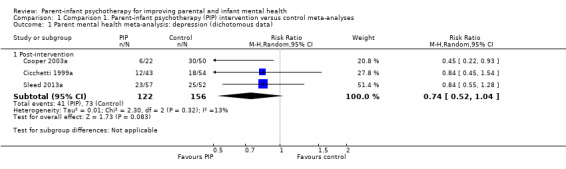

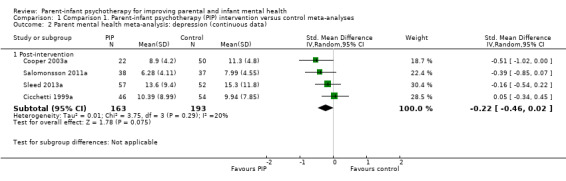

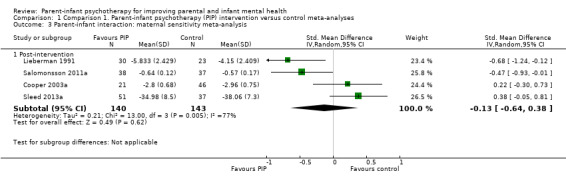

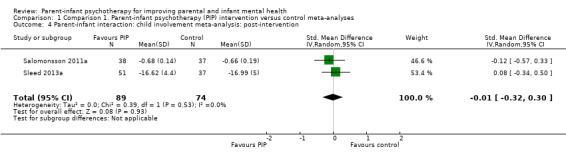

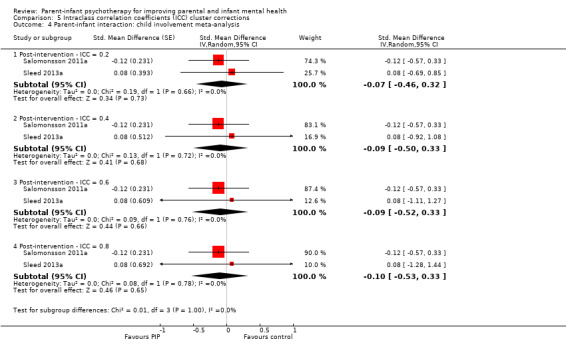

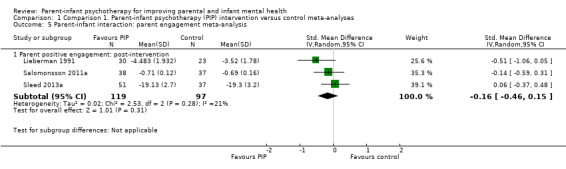

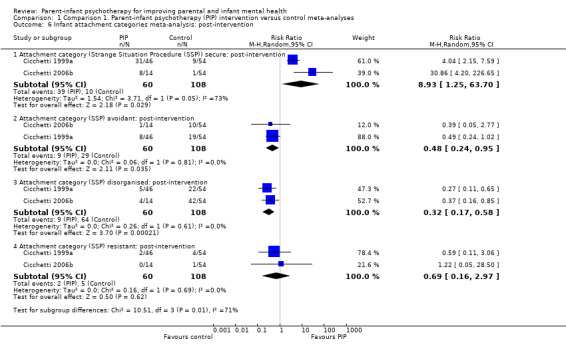

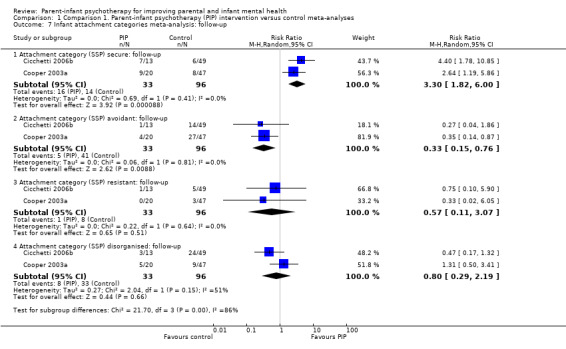

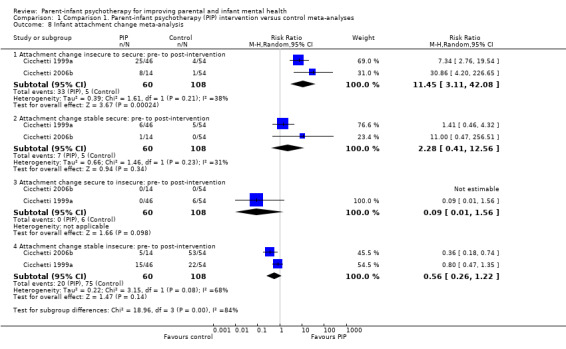

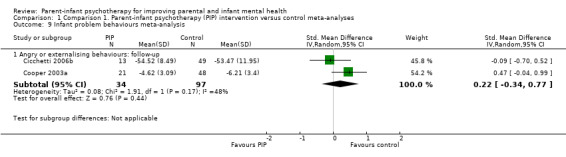

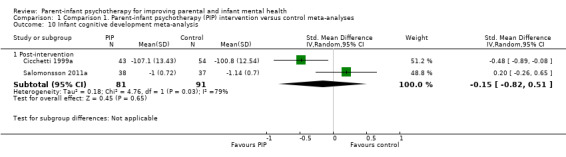

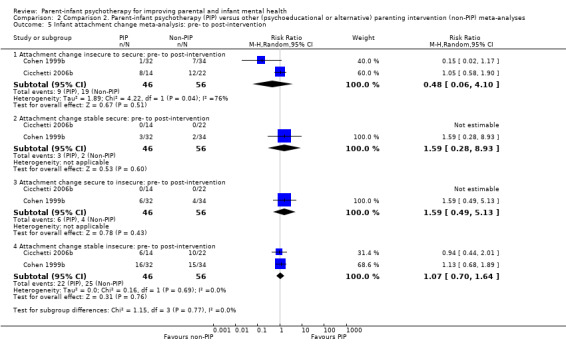

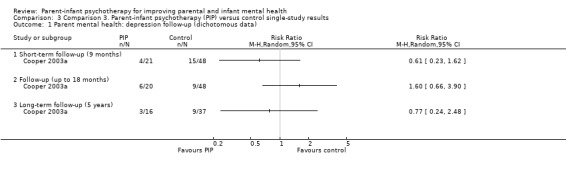

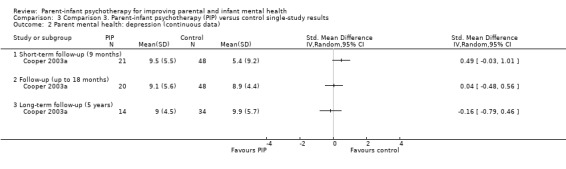

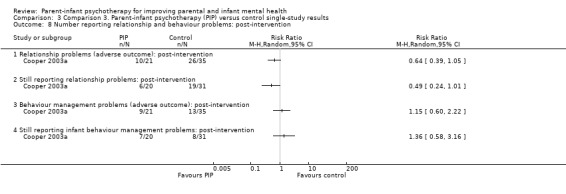

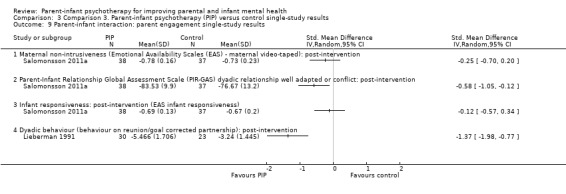

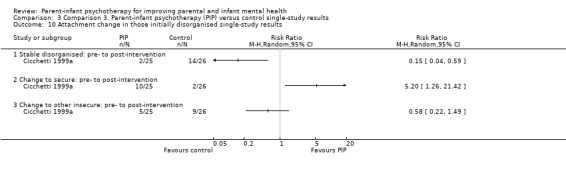

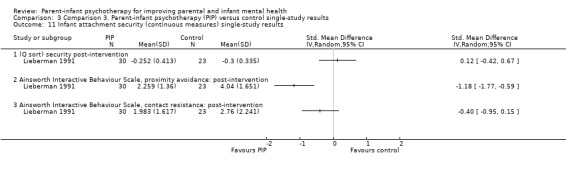

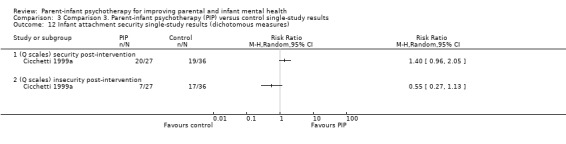

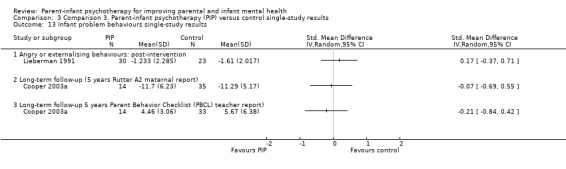

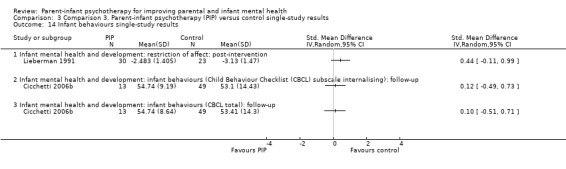

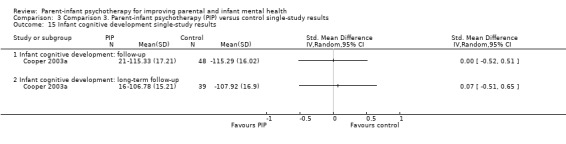

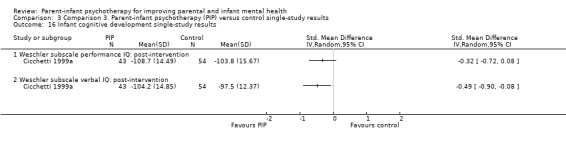

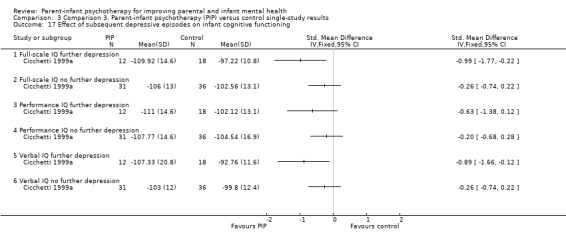

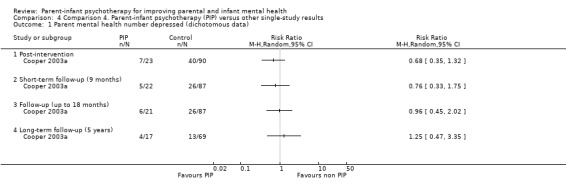

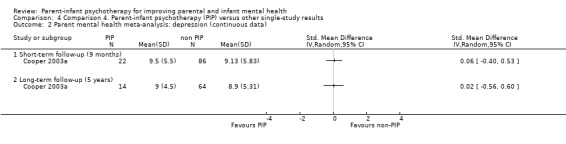

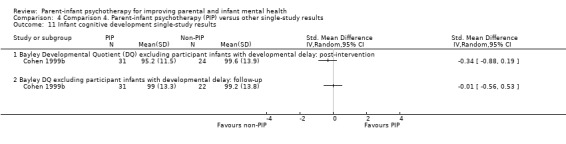

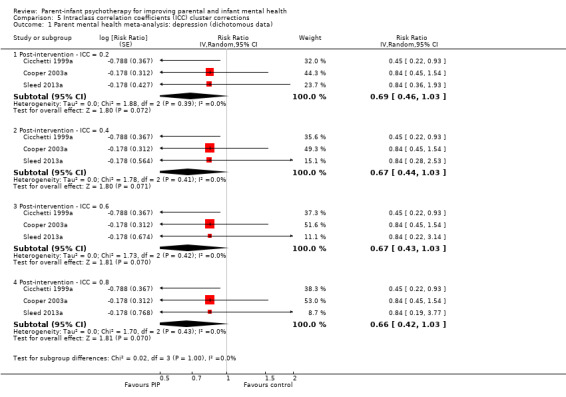

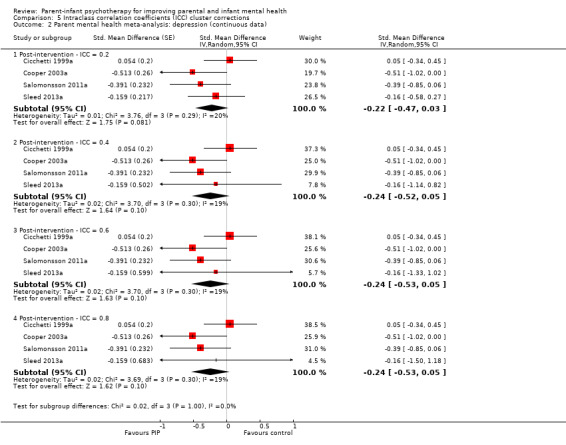

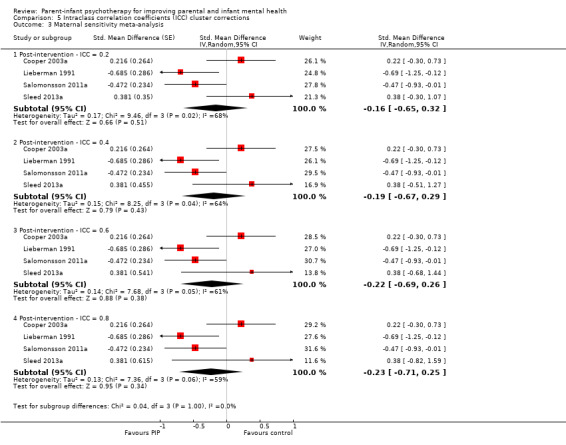

Six studies contributed data to the PIP versus control comparisons producing 19 meta‐analyses of outcomes measured at post‐intervention or follow‐up, or both, for the primary outcomes of parental depression (both dichotomous and continuous data); measures of parent‐child interaction (i.e. maternal sensitivity, child involvement and parent engagement; infant attachment category (secure, avoidant, disorganised, resistant); attachment change (insecure to secure, stable secure, secure to insecure, stable insecure); infant behaviour and secondary outcomes (e.g. infant cognitive development). The results favoured neither PIP nor control for incidence of parental depression (RR 0.74, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.04, 3 studies, 278 participants, low quality evidence) or parent‐reported levels of depression (SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.02, 4 studies, 356 participants, low quality evidence). There were improvements favouring PIP in the proportion of infants securely attached at post‐intervention (RR 8.93, 95% CI 1.25 to 63.70, 2 studies, 168 participants, very low quality evidence); a reduction in the number of infants with an avoidant attachment style at post‐intervention (RR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.95, 2 studies, 168 participants, low quality evidence); fewer infants with disorganised attachment at post‐intervention (RR 0.32, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.58, 2 studies, 168 participants, low quality evidence); and an increase in the proportion of infants moving from insecure to secure attachment at post‐intervention (RR 11.45, 95% CI 3.11 to 42.08, 2 studies, 168 participants, low quality evidence). There were no differences between PIP and control in any of the meta‐analyses for the remaining primary outcomes (i.e. adverse effects), or secondary outcomes.

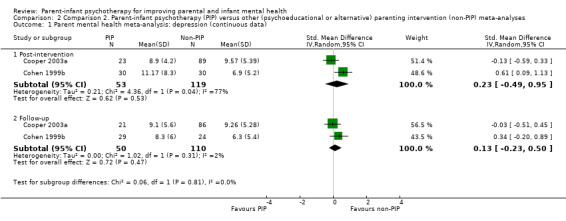

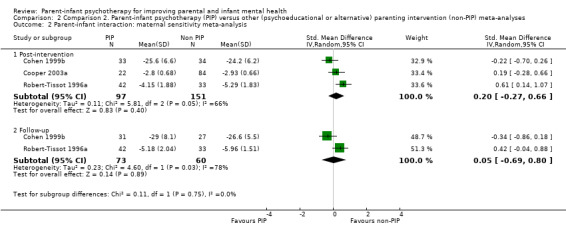

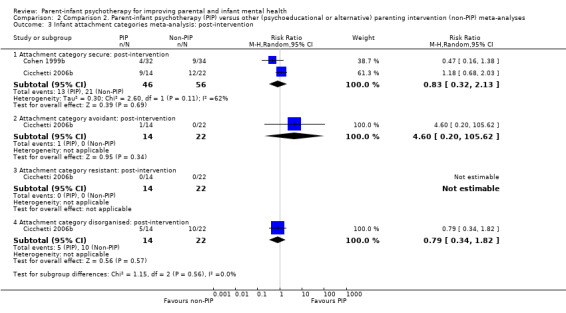

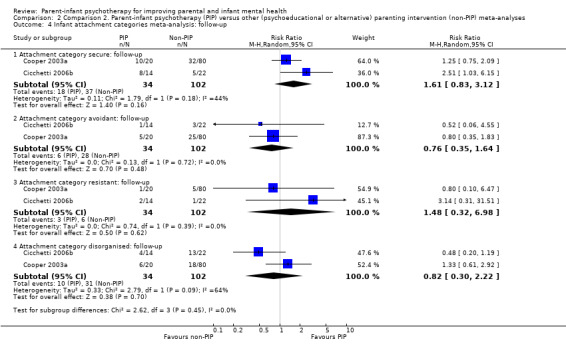

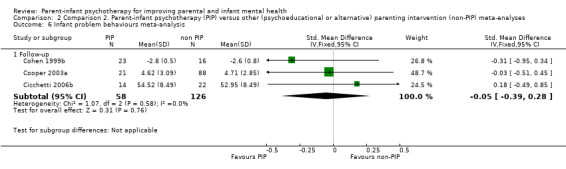

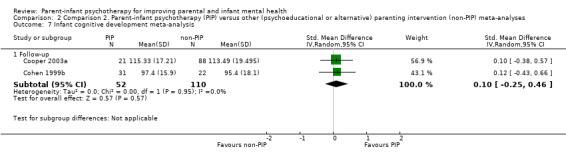

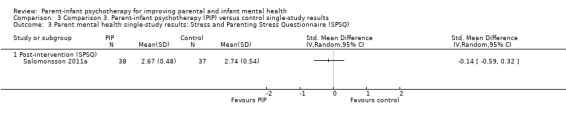

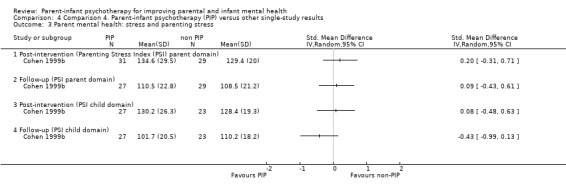

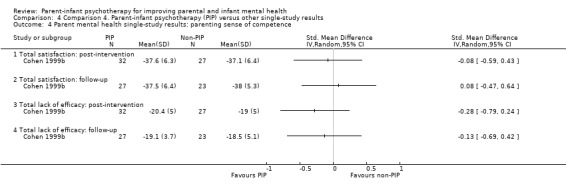

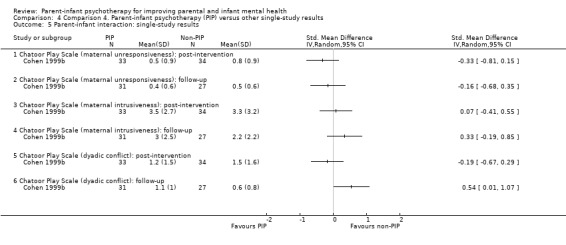

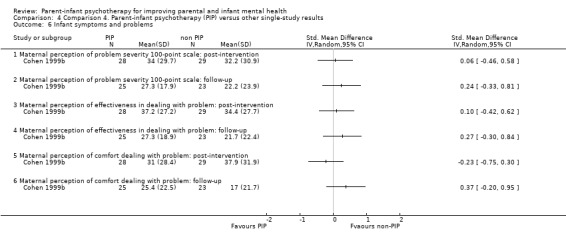

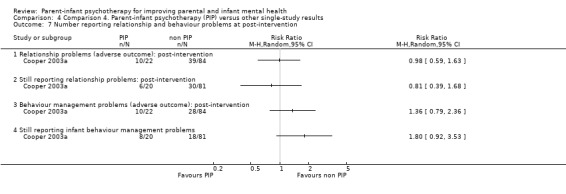

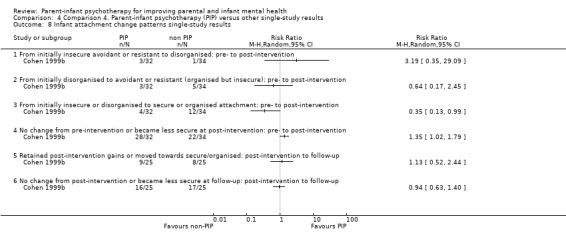

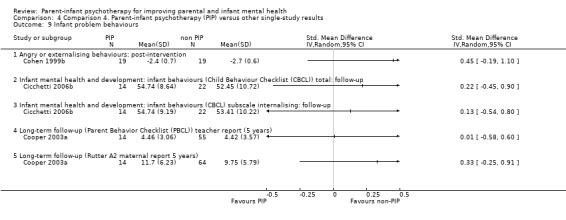

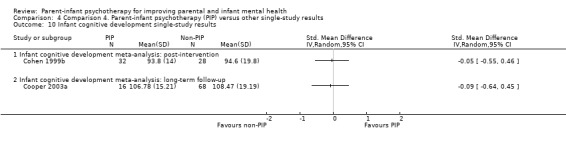

Four studies contributed data at post‐intervention or follow‐up to the PIP versus alternative treatment analyses producing 15 meta‐analyses measuring parent mental health (depression); parent‐infant interaction (maternal sensitivity); infant attachment category (secure, avoidant, resistant, disorganised) and attachment change (insecure to secure, stable secure, secure to insecure, stable insecure); infant behaviour and infant cognitive development. None of the remaining meta‐analyses of PIP versus alternative treatment for primary outcomes (i.e. adverse effects), or secondary outcomes showed differences in outcome or any adverse changes.

We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group (GRADE) approach to rate the overall quality of the evidence. For all comparisons, we rated the evidence as low or very low quality for parental depression and secure or disorganised infant attachment. Where we downgraded the evidence, it was because there was risk of bias in the study design or execution of the trial. The included studies also involved relatively few participants and wide CI values (imprecision), and, in some cases, we detected clinical and statistical heterogeneity (inconsistency). Lower quality evidence resulted in lower confidence in the estimate of effect for those outcomes.

Authors' conclusions

Although the findings of the current review suggest that PIP is a promising model in terms of improving infant attachment security in high‐risk families, there were no significant differences compared with no treatment or treatment‐as‐usual for other parent‐based or relationship‐based outcomes, and no evidence that PIP is more effective than other methods of working with parents and infants. Further rigorous research is needed to establish the impact of PIP on potentially important mediating factors such as parental mental health, reflective functioning, and parent‐infant interaction.

Keywords: Female, Humans, Infant, Mental Health, Parent‐Child Relations, Depression, Depression/diagnosis, Depression/therapy, Family Therapy, Family Therapy/methods, Father‐Child Relations, Mental Disorders, Mental Disorders/therapy, Mother‐Child Relations, Mother‐Child Relations/psychology, Object Attachment, Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic, Spouse Abuse

Plain language summary

Parent‐infant psychotherapy for improving parent and infant well‐being

Background

Parent‐infant psychotherapy (PIP) is intended to address problems in the parent‐infant relationship, and problems such as excessive crying and sleeping/eating difficulties. A parent‐infant psychotherapist works directly with the parent and infant in the home or clinic, to identify unconscious patterns of relating and behaving, and influences from the past that are impeding the parent‐infant relationship. Parents may be referred to this service (e.g. by a general practitioner in the UK) or may self refer to privately run services. The intervention is delivered to individual dyads but can also be delivered to small groups of parents and infants.

Review question

This review examined whether PIP is effective in improving the parent‐infant relationship, or other aspects of parent or infant functioning, and to identify the programme components that appear to be associated with more effective outcomes and factors that modify intervention effectiveness (e.g. programme duration, programme focus).

Study characteristics

We searched electronic databases and identified randomised controlled trials (RCTs, where participants are randomly allocated to one of two or more treatment groups) and one cluster randomised trial (where prisons rather than participants were used as the unit of randomisation), in which participants had been allocated to a receive PIP versus a control group, and which reported results using at least one standard measure of outcome (i.e. an instrument which has been tested to ensure that it reliably measures the outcome under investigation).

Evidence is current to 13 January 2014.

We identified eight studies with 846 randomised participants comparing either PIP with a no‐treatment control group (four studies) or comparing PIP with other types of treatment (four studies).

Key results

The studies comparing PIP with a no‐treatment control group contributed data to 19 meta‐analyses of the primary outcomes of parental mental health (depression), parent‐infant interaction outcomes of maternal sensitivity (i.e. the extent to which the caregiver responds in a timely and attuned manner), child involvement and parent positive engagement, and infant outcomes of infant attachment category (the infant's ability to seek and maintain closeness to primary caregiver ‐ infant attachment is classified as follows: 'secure' infant attachment is a positive outcome, which indicates that the infant is able to be comforted when distressed and is able to use the parent as a secure base from which to explore the environment. Infants who are insecurely attached are either 'avoidant' (i.e. appear not to need comforting when they are distressed and attempt to manage the distress themselves); or 'resistant' (i.e. unable to be comforted when distressed and alternate between resistance and anger). Children who are defined as ‘disorganised’ are unable to produce a coherent strategy in the face of distress and produce behaviour that is a mixture of approach and avoidance to the caregiver); and the secondary outcomes of infant behaviour and infant cognitive development (i.e. intellectual development, including thinking, problem solving and communicating).

In our analyses, parents who received PIP were more likely to have an infant who was securely emotionally attached to the parent after the intervention; this a favourable outcome but there is very low quality evidence to support it.

The studies comparing PIP with another model of treatment contributed data to 15 meta‐analysis assessments of primary outcomes, including parental mental health, parent‐infant interaction (maternal sensitivity); infant attachment and infant behaviour, or secondary infant outcomes such as infant cognitive development. None of these comparisons showed differences that favoured either PIP or the alternative intervention.

None of the comparisons of PIP with either a control or comparison treatment group showed adverse changes for any outcome.

We conclude that although PIP appears to be a promising method of improving infant attachment security, there is no evidence about its benefits in terms of other outcomes, and no evidence to show that it is more effective than other types of treatment for parents and infants. Further research is needed.

Quality of the evidence

The included studies were unclear about important quality criteria, had limitations in terms of their design or methods, or we judged that there was risk of bias in the trial. This lower quality evidence gives us less confidence in the observed effects.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Parent‐infant psychotherapy versus control for improving parental and infant mental health: parent mental health and infant attachment.

| Comparison 1: parent‐infant psychotherapy intervention versus control: parental and infant mental health | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with improving parental and infant mental health Settings: research clinic Intervention: parent‐infant psychotherapy intervention versus control | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Parent‐infant psychotherapy | |||||

| Parent mental health meta‐analysis: depression (dichotomous data) ‐ post‐intervention Number depressed | Study population | RR 0.74 (0.52 to 1.04) | 278 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control | |

| 468 per 1000 | 346 per 1000 (243 to 487) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 481 per 1000 | 356 per 1000 (250 to 500) | |||||

| Parent mental health meta‐analysis: depression (continuous data) ‐ post‐intervention Validated assessment scales for depression, lower scores are less depressed | The mean depression scores in the control group ranged from 7.99 to 15.3 | The mean depression in the intervention groups was

0.22 standard deviations lower

(0.46 lower to 0.02 higher). The mean depression score in the intervention group was 1.1 lower (2.2 lower to 0.1 higher) |

‐ | 356 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Scores estimated using an SMD: SMD ‐0.22, 95% CI ‐0.46 to 0.02. There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control |

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: post‐intervention ‐ attachment category (SSP) secure Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 8.93 (1.25 to 63.7) | 168 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Favours PIP (more infants secure in PIP) | |

| 93 per 1000 | 827 per 1000 (116 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 93 per 1000 | 830 per 1000 (116 to 1000) | |||||

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: post‐intervention ‐ attachment category (SSP) disorganised Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 0.32 (0.17 to 0.58) | 168 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Favours PIP (fewer infants disorganised in PIP) | |

| 593 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (101 to 344) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 593 per 1000 | 190 per 1000 (101 to 344) | |||||

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: follow‐up ‐ attachment category (SSP) secure Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 3.3 (1.82 to 6) | 129 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Favours PIP (more infants secure in PIP) | |

| 146 per 1000 | 481 per 1000 (265 to 875) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 146 per 1000 | 482 per 1000 (266 to 876) | |||||

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: follow‐up ‐ attachment category (SSP) disorganised Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 0.8 (0.29 to 2.19) | 129 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control | |

| 344 per 1000 | 275 per 1000 (100 to 753) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 341 per 1000 | 273 per 1000 (99 to 747) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PIP: parent‐infant psychotherapy; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference; SSP: Strange Situation Procedure. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias due to study designs, randomisation and allocation concealment; and not possible to blind participants or personnel. 2 Relatively few participants and wide confidence intervals. 3 Moderate to high levels of statistical heterogeneity.

Summary of findings 2. Parent‐infant psychotherapy versus other (psychoeducational) parenting intervention: parent mental health and infant attachment.

| Comparison 2: parent‐infant psychotherapy versus other (psychoeducational) parenting intervention: parental and infant mental health | ||||||

| Patient or population: participants with improving parental and infant mental health Settings: research clinic Intervention: parent‐infant psychotherapy versus other (psychoeducational) parenting intervention | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Number of participants (studies) | Quality of evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control (other (psychoeducational) parenting intervention) | Parent‐infant psychotherapy | |||||

| Parent mental health meta‐analysis: depression continuous data ‐ post‐intervention Validated assessment scales for depression, lower scores are less depressed | The mean depression scores in the non‐PIP group ranged from 6.9 to 9.57 | The mean depression scores in the intervention groups were

0.23 standard deviations higher

(0.49 lower to 0.95 higher). The mean depression score in the intervention group was 1.2 higher (2.6 lower to 5.1 higher) (Cohen 1999b used as a representative study) |

‐ | 172 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | Scores estimated using an SMD: SMD 0.23, 95% CI ‐0.49 to 0.95. There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control |

| Parent mental health meta‐analysis: depression continuous data ‐ follow‐up (up to 18 months) Validated assessment scales for depression, lower scores are less depressed | The mean depression scores in the non‐PIP group ranged from 6.3 to 9.26 | The mean depression scores in the intervention groups were

0.13 standard deviations higher

(0.23 lower to 0.5 higher). The mean depression score in the intervention group was 0.70 higher (1.24 lower to higher) (Cohen 1999b used as a representative study) |

‐ | 160 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | Scores estimated using an SMD: SMD 0.13, 95% CI ‐0.23 to 0.5. There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control |

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: post‐intervention ‐ attachment category secure Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 0.83 (0.32 to 2.13) | 102 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | No statistically significant difference between groups | |

| 375 per 1000 | 311 per 1000 (120 to 799) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 405 per 1000 | 336 per 1000 (130 to 863) | |||||

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: post‐intervention ‐ attachment category disorganised Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 0.79 (0.34 to 1.82) | 36 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control | |

| 455 per 1000 | 359 per 1000 (155 to 827) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 455 per 1000 | 359 per 1000 (155 to 828) | |||||

| Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: follow‐up ‐ attachment category secure Ainsworth Strange Situation | Study population | RR 1.61 (0.83 to 3.12) | 136 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and alternative intervention | |

| 363 per 1000 | 584 per 1000 (301 to 1000) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 314 per 1000 | 506 per 1000 (261 to 980) | |||||

|

Infant attachment categories meta‐analysis: follow‐up ‐ attachment category disorganised Ainsworth Strange Situation |

Study population | RR 0.82 (0.3 to 2.22) | 136 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | There was no clear evidence of a difference between PIP and control | |

| 304 per 1000 | 249 per 1000 (91 to 675) | |||||

| Moderate | ||||||

| 408 per 1000 | 335 per 1000 (122 to 906) | |||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; PIP: parent‐infant psychotherapy; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference. | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Risk of bias due to study designs, including randomisation and allocation concealment; and not possible to blind participants or personnel. 2 Relatively few participants and wide confidence intervals. 3 Moderate to high levels of statistical heterogeneity.

Background

Description of the condition

Infant regulatory disturbances, such as excessive crying, feeding or sleeping difficulties, and bonding/attachment problems represent the main reasons for referral to infant mental health clinics (Keren 2001). The Copenhagen Child Cohort Study (6090 infants) found a population prevalence of such regulatory problems (including emotional and behavioural, eating and sleeping disorders) in children aged 1.5 years in the region of 18% (Skovgaard 2008; Skovgaard 2010). Some regulatory disturbances are stable over time with as many as 49.9% of infants and toddlers (aged 12 to 40 months) showing a continuity of emotional and behavioural problems one year after initial presentation (Briggs‐Gowan 2006). Problems of this nature are also significant predictors of longer‐term difficulties. For example, infant regulatory problems have a strong association with delays in motor, language and cognitive development, and continuing parent‐child relational problems (DeGangi 2000a; DeGangi 2000b). Difficult temperament, non‐compliance and aggression in infancy and toddlerhood (aged one to three years) are associated with internalising and externalising psychiatric disorders at five years of age (Keenan 1998). Insecure and disorganised attachment in infancy is also associated with poorer outcomes in childhood across a range of domains such as emotional, social and behavioural adjustment, scholastic achievement and peer‐rated social status (Berlin 2008; Granot 2001; Sroufe 2005a; Sroufe 2005b), particularly in the case of disorganised attachment, which is a significant predictor of significant later psychopathology (Green 2002).

Infant regulatory and attachment problems can best be understood in a relational context, and disturbances to the parent‐child relationship and parental psychosocial adversity are significant risk factors for infant emotional, behavioural, eating and sleeping disorders (Skovgaard 2008; Skovgaard 2010). Early research in the field of infant mental health and developmental psychology has highlighted the significant role that the infant's primary carer plays in regulating the infant (Beebe 2010; Sroufe 1997; Tronick 1989; Tronick 1997), but one systematic review found only modest correlations between 'maternal sensitivity' and infant attachment security (De Wolff 1997), prompting a search for more specific predictive factors. Research has focused on the specific nature or quality of the attunement or contingency between parent and infant (Beebe 2010), and the parent's capacity for what has been termed 'maternal mind‐mindedness' (Meins 2001) or 'reflective function' (Slade 2001).

Beebe developed the term 'mid‐range contingency' to refer to interaction in which both the parent's self regulation and the interactive regulation between parent and infant is in the mid‐range (Beebe 1988). Parents with low interactive tracking (e.g. resulting from withdrawal due to postnatal depression) are more likely to have infants who are insecurely attached, as are parents who have high interactive tracking (i.e. due to excessive vigilance resulting from anxiety) (Beebe 2010).

Parental reflective function refers to the parent's capacity to understand the infant's behaviour in terms of internal feeling states, and is strongly associated with maternal parenting behaviours, such as flexibility and responsiveness, while low maternal reflective function is associated with emotionally unresponsive maternal behaviours (withdrawal, hostility, intrusiveness) (Kelly 2005; Slade 2001; Slade 2005). Maternal reflective function is also associated with more optimal infant outcomes such as a greater use of the mother as a 'secure base' (i.e. the infant can be comforted by the primary carer when distressed, and able to explore the world in the presence of the carer when not distressed) (Kelly 2005). There is also a significant association between parental 'mind‐mindedness' (the parent's capacity to interpret what their child is thinking and feeling accurately) and later development, including attachment security at 12 months (Meins 2001).

Research has also highlighted a number of 'atypical' parenting behaviours that can be present during the postnatal period, including affective communication errors (e.g. mother positive while infant distressed), disorientation (frightened expression or sudden complete loss of affect) and negative‐intrusive behaviours (mocking or pulling infant's body) (Lyons‐Ruth 2005). A meta‐analysis of 12 studies found a strong association between disorganised attachment at 12 to 18 months of age and parenting behaviours characterised as 'anomalous' (i.e. frightening, threatening, looming), dissociative (haunted voice, deferential/timid) or disrupted (failure to repair, lack of response, insensitive/communication error) (Madigan 2006). These atypical parenting practices were identified in parents described as 'unresolved' with regard to previous trauma (Cicchetti 2006a; Cicchetti 2010; Jacobvitz 1997). However, disturbances to the mother‐infant relationship are common and are associated with a range of maternal problems, including postnatal depression (Murray 2003; Timmer 2011; Toth 2006), personality disorder (Crandell 2003; Newman 2008), psychotic disorders (Chaffin 1996), substance misuse (Suchman 2005; Tronick 2005), and domestic violence (Lyons‐Ruth 2003; Lyons‐Ruth 2005).

Description of the intervention

Since the mid‐1990s, a range of interventions (e.g. home visiting and parenting programmes) have been developed to address developmental problems in the infant, and problems in the parent‐infant relationship, with a view to promoting optimal infant development. These have mostly targeted the parent and used a range of techniques in their delivery (discussion, role play, watching video vignettes, and homework), with the aim of changing parenting behaviours and attitudes. Parent‐infant psychotherapy (PIP) in contrast is a dyadic intervention (or triadic if both parents are involved) that involves targeting the parent‐infant relationship (i.e. it is delivered to parent and infant together). A parent‐infant psychotherapist works by listening and observing the interaction, identifying the concerns and worries, and helping the parent observe and find different ways to relate to their baby. This work may take place in the home, clinic or hospital setting, and aims to address a wide range of problems that can arise during the antenatal and postnatal periods. The intervention is usually delivered to individual dyads but can also be delivered to small groups of dyads.

PIP focuses on improving the parent‐infant relationship and infant attachment security by targeting parental internal working models (i.e. representational world ‐ see below) and by working directly with the parent‐infant relationship in the room. The approach is essentially psychodynamic in that it involves identifying unconscious patterns of relating, and the earliest approach, developed by Selma Fraiberg (Fraiberg 1980), focused primarily on the mother's 'representational' world ('representation‐focused' approach) or the way in which the mother's current view of her infant was affected by interfering representations from her own history. The aim of such therapy was to help the mother to recognise the 'ghosts in the nursery' (i.e. the unremembered influences from her own past) and to link them to her current functioning, in order to improve the parent‐infant relationship directly, thereby facilitating new paths for growth and development for both mother and infant (Cramer 1988). Fraiberg's model has been further developed and evaluated by others (e.g. Lieberman 1991; Toth 2006), and representational and behavioural approaches have been combined (Cohen 1999a). For example, 'Watch, Wait and Wonder' (WWW) is an 'infant‐led' PIP that involves the mother spending time observing her infant's self initiated activity, accepting the infant's spontaneous and undirected behaviour, and being physically accessible to the infant (behavioural component). The mother then discusses her experiences of the infant‐led play with the therapist with a view to examining the mother's internal working models of herself in relation to her infant (representational component) (Cohen 1999a). PIP may also work with the father or other primary carer, or with two parents together.

The duration of the intervention depends on the presenting problems but typically ranges from five to 20 weeks, usually involving weekly sessions. Parents may be referred to this service by a clinician (e.g. general practitioner (GP) or health visitor in the UK) or may self‐refer to privately run services. PIP services typically target infants less than two years of age at the time of referral. This reflects the importance of the first two years of life in terms of children's later development (as described above).

How the intervention might work

The logic model underpinning representational forms of PIP is that changes to the mother's representations (internal working models) will improve the mother's sensitivity and behaviour towards her infant (e.g. Lieberman 1991), thereby reducing distorted projections and making it possible for her to see the infant as someone with a 'mind of their own'. Maternal sensitivity is strongly associated with more optimal parent‐infant interaction, which, in turn, is associated with infant attachment security (De Wolff 1997). Secure attachment is associated with resilience and optimal social functioning (Sroufe 2005a; Sroufe 2005b), while both insecure (Berlin 2008; Granot 2001; Lecce 2008; Sroufe 2005a; Sroufe 2005b), and disorganised attachment are associated with a range of compromised outcomes (Green 2002; Lyons‐Ruth 2005). The addition of behavioural components provides opportunities for parent and infant to interact, which then become the focus of exploratory discussions between therapist and parent, aimed once again at changing maternal representations about the infant (Cohen 1999a). The empathic relationship between the therapist and parent also plays a key role in helping parents to revise their internal working models (Toth 2006).

Why it is important to do this review

Parent‐infant interaction is a significant factor in infant mental health (Fonagy 2002), and problems with the parent‐infant relationship are common (Keren 2001). Government policy internationally is increasingly emphasising the importance of early intervention and the need to develop empirically derived models that can support vulnerable parents and their children, and this reflects an increased recognition at policy level that both health and social inequalities have their origins in early parent‐infant interaction (Field 2010), and that the social gradient in children's access to positive early experiences needs to be addressed (Marmot 2010).

There is a growing body of evidence pointing to the effectiveness of PIP in terms of improving both parental functioning (Cohen 1999a; Cohen 2002), and fostering secure attachment relationships in young children (Toth 2006), and there is some evidence to suggest that different forms of the therapy may be differentially effective for parents with different types of attachment insecurity (Bakermans‐Kranenburg 1998).

However, to date, there has been only one 'thematic' summary of the evidence about the effectiveness of PIP (Kennedy 2007), which did not involve a systematic search for evidence. As such, there is a need for a systematic review to identify whether this unique method of working has benefits for parents (both mothers and fathers) and infants, and whether the outcome is affected by the duration or content of the intervention.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of PIP in improving parental and infant mental health and the parent‐infant relationship.

To identify the programme components that appear to be associated with more effective outcomes and factors that modify intervention effectiveness (e.g. programme duration, programme focus).

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We pre‐specified our methods for this review in the protocol (Barlow 2013).

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi‐randomised controlled trials (quasi‐RCTs) in which participants had been randomly allocated to an experimental or a control group, the latter being a waiting‐list, no treatment, treatment‐as‐usual (normal service provision) or a placebo control group. We defined quasi‐RCTs as trials where allocation was done on the basis of a pseudo‐random sequence, for example, odd or even hospital number, date of birth or alternation (Higgins 2011). We also included studies comparing two different therapeutic modalities (i.e. without a control group).

Types of participants

We included studies involving parent‐infant dyads in which the parent was experiencing mental health problems, domestic abuse or substance dependency, with or without the infant showing signs of attachment or dysregulation problems, or both attachment and dysregulation problems. We included all infants irrespective of the presence of problems such as low birthweight, prematurity or disabilities. We included studies targeting infants and toddlers in which the mean age of the infant participants was 24 months or less at the point of referral. We included studies targeting all parents (i.e. including fathers, birth parents, adoptive and kinship parents, but not foster parents).

Types of interventions

We included studies that had evaluated the effectiveness of PIP programmes in which the intervention met all of the following criteria:

underpinned by a psychodynamic model that involved making unconscious patterns of relating by targeting the parent‐therapist transference; parental internal working models or representations (i.e. the way in which the mother's current view of her infant was affected by interfering representations or unremembered influences from her own history, and to link them to her current functioning, in order to improve the parent‐infant relationship directly, thereby facilitating new paths for growth and development for both mother and infant);

delivered jointly to both parent and infant with a focus on the parent‐infant relationship/interaction and aimed primarily at improving infant attachment security, socio‐emotional functioning, or both, via the parent‐infant relationship/interaction;

delivered by a parent‐infant psychotherapist/specialist on a dyadic basis or to dyads in groups, in any setting (clinic, hospital or home), over any period of time.

We also included studies of PIPs that used additional components (i.e. provided they still met the core inclusion criteria). We excluded studies of interventions that were delivered to the parent or parents alone (e.g. interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) or that were dyadic but primarily psychoeducational or based on other therapeutic models (e.g. behavioural or cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT)). We excluded studies of stand‐alone video‐interaction guidance interventions but not studies in which video feedback had been incorporated into a PIP that met the above criteria.

Types of outcome measures

We extracted data for the following outcomes at both post‐intervention and follow‐up, provided they had been measured using a standardised parent‐report or independent observation of the type listed as examples for each outcome below.

Primary outcomes

Parent outcomes

Parental mental health including, for example, depression* (e.g. Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (Beck 1961); anxiety (e.g. Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck 1988); parenting stress (e.g. Parenting Stress Index (PSI) (Abidin 1983).

Parent‐infant relationship outcomes

Parent‐infant interaction including, for example, Child‐Adult Relationship Experimental‐Index (CARE‐Index) (Crittenden 2001), Emotional Availability Scales (EAS) (Biringen 1993), Parent‐Child Early Relational Assessment (PC‐ERA) (Clark 1985), Dyadic Parent‐Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS) (Robinson 1981), Nursing Child Assessment of Feeding Scale (NCAFS) (Barnard 1978a), or the Nursing Child Assessment Teaching Scale (NCATS) (Barnard 1978b); Maternal Sensitivity Scale (MSS) (Ainsworth 1974), Atypical Maternal Behavior Instrument for Assessment and Classification (AMBIANCE) (Bronfman 1999), or Frightened/Frightening (FR) Coding System (Main 1992).

Infant outcomes

Infant emotional well‐being including, for example, infant attachment* measures such as the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) (Ainsworth 1971), Preschool Measure of Attachment (PMA) (Crittenden 1992), or other measures of emotional and behavioural adjustment such as the Infant and Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (ITSEA) (Carter 2000), Eyberg Child Behaviour Inventory (ECBI) (Eyberg 1978), Behaviour Screening Questionnaire (BSQ) (Richman 1971), and the Child Behaviour Questionnaire (CBQ) (Rutter 1970).

Adverse effects

Adverse effects of interventions were included as an outcome, including a worsening of outcome on any of the included measures.

Secondary outcomes

Parent outcomes

Parental reflective function including, for example, Parent Development Interview (PDI) (Slade 2004).

Infant outcomes

Infant stress including, for example, salivary or urinary cortisol measured in standardised units such as micrograms per decilitre (μg/dL) or nanograms per millilitre (ng/mL).

Infant development including, for example, social, emotional, cognitive and motor development using the Bayley Scales (Bayley 1969).

*For the comparison of PIP versus control, we used the primary outcomes of parental depression at post‐intervention and infant attachment at post‐intervention and follow‐up to complete Table 1. For the comparison of PIP versus alternate intervention in Table 2, we used the primary outcomes of parental depression at post‐intervention and follow‐up, and for infant attachment, we used outcomes from post‐intervention and follow‐up.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases on 13 January 2014 without restrictions on language, date or publication status. We applied RCT filters where appropriate (see Appendix 1).

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) 2014 ( Issue 1), part of The Cochrane Library.

Ovid MEDLINE, 1950 to 10 January 2014.

EMBASE (Ovid), 1980 to January week 1 2014.

CINAHL (EBSCO), 1982 to current.

PsycINFO (Ovid), 1806 to January week 1 2014.

BIOSIS Citation Index (ISI), all available years.

SSCI (Web of Science), 1970 to current.

ERIC (ProQuest), 1966 to current.

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest), 1952 to current.

We also searched the metaRegister of Controlled Trials (mRCT) on 20 January 2014 (Appendix 2).

Searching other resources

We contacted authors and experts in the field to identify unpublished studies. We handsearched reference lists of articles identified through database searches for further relevant studies. We also examined bibliographies of systematic and non‐systematic review articles to identify relevant studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

Two review authors (CB and JB) screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified by the searches to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria and independently assessed full copies of papers that appeared to meet the inclusion criteria. We resolved any uncertainties by discussion with a third review author (NM).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (CB and SL) independently extracted data using an identical data extraction form and entered the data into Review Manager 5 software (RevMan 2012). Where data were not available in the published trial reports, we contacted study investigators to supply missing information. We extracted information regarding: study design, measurement of delivery fidelity, participant characteristics, primary and secondary outcome measures, and data.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (CB, SL) carried out 'Risk of bias' assessments using The Cochrane Collaboration 'Risk of bias' assessment tool (Higgins 2011). We resolved differences by consultation with a third review author (JB or NM). We assessed each trial in the following areas: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting and other sources of bias, including whether there was any assessment of the distribution of confounders. Where there was insufficient information in the trial report to make a judgement, we contacted trial investigators for further information.

We assessed all domains as being at low, high or unclear (uncertain) risk of bias.

We used 'Risk of bias' assessments in the synthesis of data, to interpret findings for specific outcomes and to comment on the quality of the evidence.

Sequence generation

We assessed the method used to generate the allocation sequence to identify whether it had produced comparable groups.

Allocation concealment

We assessed the method used to conceal allocation sequence to assess its adequacy in terms of whether the intervention schedules could have been foreseen in advance of, or during, recruitment.

Blinding

We assessed whether any steps were taken to blind participants and personnel, and to blind outcome assessors to the intervention that participants received.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed whether incomplete data was dealt with adequately, and how data on attrition and exclusions were reported in comparison with the total number of participants randomised. Where studies did not report intention‐to‐treat (ITT) analyses, we attempted to obtain missing data by contacting the study authors.

Selective outcome reporting

We assessed whether any attempt had been made to reduce the possibility of selective outcome reporting.

Other sources of bias

We examined baseline or pre‐treatment means, where available, to assess whether there was any imbalance in terms of participant characteristics that were strongly related to outcome measures and that could cause bias in intervention effect estimates (Higgins 2011, Chapter 8.14.1.2).

We assessed whether the study was free of other problems that could have put it at a high risk of bias (e.g. contamination).

Measures of treatment effect

Dichotomous outcome data

For dichotomous endpoint measures, we present the number of parents or infants who showed an improvement as a proportion of the total number of parents/infants treated. We calculated risk ratios (RR) by dividing the risk in one group with the risk in the other group, and present these with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and standard deviations.

Not all dichotomous measures indexed relative risks of improvement over time and, for some measures, we provided the relative risk of a positive state (e.g. secure attachment) at post‐intervention.

Continuous outcome data

For the meta‐analyses of continuous outcomes, we estimated the mean differences (MDs) between groups. In the case of continuous outcome measures, where data were reported on different scales, we analysed data using the standardised mean difference (SMD), calculated by dividing the MD in post‐intervention scores between the intervention and control groups by the standard deviation. We presented the SMDs and 95% CIs for all meta‐analyses and individual outcomes from individual studies (i.e. where no meta‐analysis was undertaken).

Where the above data were not available, we present significance levels reported in the paper.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

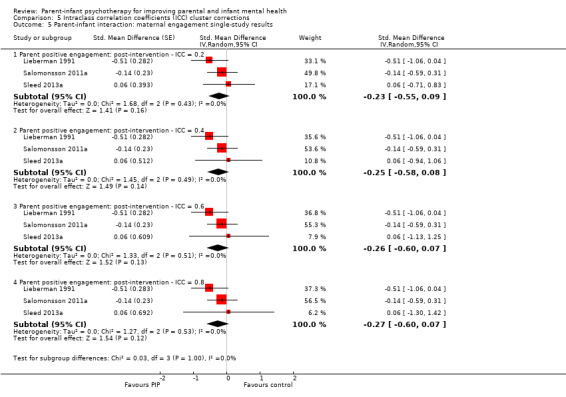

The randomisation of clusters can result in an overestimate of the precision of the results (with a higher risk of a Type I error) where their use has not been compensated for in the analysis. One study employed cluster‐randomisation (Sleed 2013a, mother and baby units in prisons). We explored the impact of the inclusion of data from this study in the meta‐analyses by imputing a set of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) (0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.8) (i.e. we were unable to identify external evidence for a reasonable ICC and for this reason, we selected multiple values for ICCs). We calculated the inflated standard errors that accounted for clustering by multiplying the original standard errors with the square root of the associated design effects (see Higgins 2011, Chapter 16.3.6).

Studies with multiple treatment groups

For studies where there was more than one active intervention and only one control group, we selected the intervention that most closely matched our inclusion criteria and excluded the others (see Higgins 2011, Chapter 16.5.4).

Dealing with missing data

We assessed missing data and attrition for each included study and reported them in the 'Risk of bias' tables. Where appropriate, we contacted authors to supply data missing from included studies. Where missing data could not be provided, we have reported this and the available data only (i.e. we used no imputation).

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed clinical heterogeneity by examining the extent of between‐trial differences, including methods, populations, interventions, whether the delivery of the intervention was monitored (to ascertain fidelity), and outcomes.

We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic. The importance of the observed I2 value is dependent on the magnitude and direction of effects and strength of evidence for heterogeneity (e.g. P value from the Chi2 test, or a CI for I2 statistic) (Higgins 2002), and we have interpreted an I2 greater than 50% as evidence of substantial heterogeneity.

Where we performed a Chi2 test of heterogeneity, we interpreted a significance level less than 0.10 as evidence of heterogeneity. We carried out the tau2 estimates for each meta‐analysis and presented Chi2 values, P values, tau2 statistic and I2 statistic.

Assessment of reporting biases

Due to the small number of included studies, we were unable to assess reporting biases. For more information on how we will assess reporting bias in future updates of this review, see Barlow 2013 and Appendix 3.

Data synthesis

We undertook meta‐analysis where there was sufficient clinical homogeneity in the intervention delivered, the characteristics of the study participants (e.g. age or the definition of 'at risk' participants), and the outcome measures. We made the decision about combining data post hoc based on the categories of interventions, participants, and outcomes identified in the reviewed literature. We combined data using a random‐effects model. We calculated overall effects using inverse variance methods.

All analyses included all participants in the treatment groups to which they were allocated, whenever possible.

While we attempted to combine data where at all possible, there were some circumstances where it was not possible; for example, where some studies reported the same outcome using different formats (e.g. dichotomous and continuous), we have carried out two separate analyses. For single outcomes, we presented the individual effect sizes and 95% CIs.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We explored possible reasons for heterogeneity by scrutinising the studies to assess the extent of between‐trial differences (e.g. age of infant, presenting problems, programme duration, programme focus, and whether or not the intervention was delivered as intended).

We had planned to carry out additional subgroup analyses (Barlow 2013), but there were too few included studies in each meta‐analysis to do this (see Appendix 3 for details).

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted a sensitivity analysis using a fixed‐effect model and a random‐effects model. We intended to re‐analyse the data excluding studies on the basis of design (Barlow 2013), but there were too few included studies in each meta‐analysis to do this (see Appendix 3 for details).

'Summary of findings' tables

We presented the findings of our review in 'Summary of findings' tables (Table 1; Table 2), which provide a transparent and simple tabular format of the review's primary outcomes that may be important to parents and decision makers. For the comparison of PIP versus control, we presented findings for the outcomes of parent mental health (depression) at post‐intervention, and infant attachment at post‐intervention and follow‐up. For PIP versus alternative intervention, we presented findings for the outcomes of parent mental health (depression) at post‐intervention and follow‐up, and infant attachment at post‐intervention and follow‐up. We used GRADEpro software to construct the tables (GRADEpro 2014). The tables present information about the body of evidence (e.g. number of studies), the judgements about the underlying quality of evidence, key statistical results, and a grade for the quality of evidence for each outcome. We used the Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system to describe the quality of the evidence and the strength of recommendation (GRADE 2013; Guyatt 2011). We expressed the quality of evidence on a four‐point adjectival scale from 'high' to 'very low'. We gave evidence from RCT data initially a high quality rating but downgraded it if there was unexplained clinically important heterogeneity, the study methodology had a risk of bias, the evidence was indirect, there was important uncertainty around the estimate of effect, or there was evidence for publication bias. Therefore, it was possible for RCT data to have a very low quality of evidence if several of these concerns were present.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

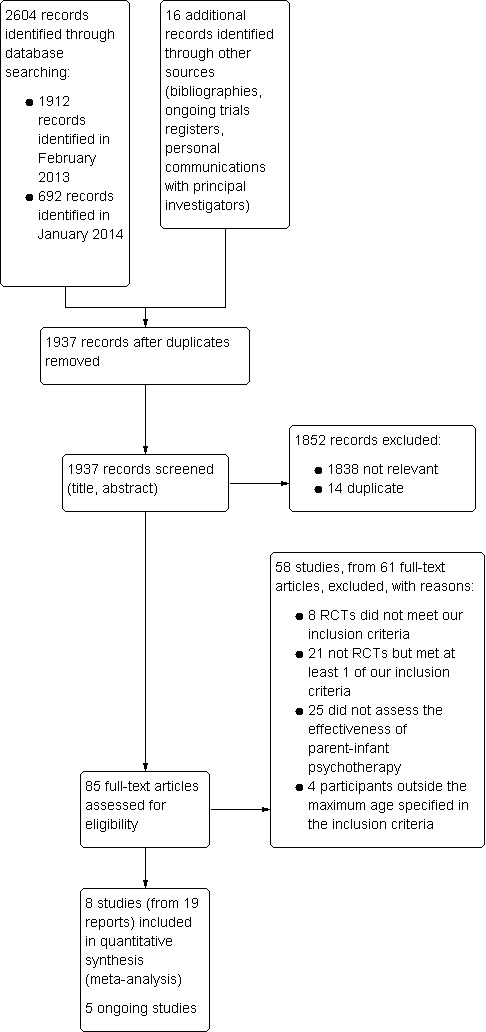

Electronic searches in February 2013 and updated in January 2014 identified 2604 records (for search results, see Appendix 4). The January 2014 search included a correction to the EMBASE search strategy. We identified 16 additional records through other sources. After we removed duplicates, we screened 1937 records. We obtained and scrutinised 85 potentially relevant records, and 61 of these reports (58 studies) did not meet the inclusion criteria and we excluded them (see Characteristics of excluded studies). We included eight studies (from 19 reports of trials) (see Characteristics of excluded studies), and identified five ongoing studies (see Characteristics of ongoing studies) (Figure 1).

1.

Study flow diagram

Our included studies were: Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Cohen 1999b; Cooper 2003a; Lieberman 1991; Robert‐Tissot 1996a; Salomonsson 2011a; and Sleed 2013a. These were grouped as follows:

Cicchetti 1999a comprised three reports (Cicchetti 1999b; Cicchetti 2000; Toth 2006);

Cicchetti 2006b comprised three reports (Cicchetti 2006a; Cicchetti 2011a; Stronach 2013);

Cohen 1999b comprised three reports (Cohen 1999a; Cohen 2000; Cohen 2002);

Cooper 2003a comprised two reports (Cooper 2003b; Murray 2003);

Lieberman 1991 was a single report;

Robert‐Tissot 1996a comprised two reports (Cramer 2002; Robert‐Tissot 1996b);

Salomonsson 2011a comprised three reports (Salomonsson 2011b; Salomonsson 2011c; Salomonsson 2011d); and

Sleed 2013a was a single published report; further details can be found on the Anna Freud Centre's website (Anna Freud 2014).

In both studies conducted by Cicchetti et al. (Cicchetti 1999a and Cicchetti 2006b), each subsequent publication reported on a subset of the main study for which data were available, therefore some details, such as participant demographics, were reported differently in each publication. We have summarised these differences in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Included studies

Three studies were conducted in the USA (Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Lieberman 1991), two in the UK (Cooper 2003a; Sleed 2013a); and one each in Canada (Cohen 1999b), Switzerland (Robert‐Tissot 1996a), and Sweden (Salomonsson 2011a).

Methods

All of the included studies were RCTs. Some of the studies also recruited or compared results from a non‐randomised control group (Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Robert‐Tissot 1996a); we have not included the results from these non‐randomised arms in this review.

Design

Three studies employed a two‐arm RCT design in which participants were randomised either to PIP or a control (treatment‐as‐usual) condition (Cicchetti 1999a; Lieberman 1991; Salomonsson 2011a), one other employed a cluster‐randomised trial design in which mother and baby units in UK prisons were allocated to either the treatment (PIP) or a control standard care condition (Sleed 2013a). We included these studies in analyses of PIP versus control (control being no intervention or treatment‐as‐usual).

Two studies compared PIP with another treatment: one compared PIP that followed Fraiberg's model (Fraiberg 1987), and hereafter referred to as psychodynamic psychotherapy (PPT), with an 'infant‐led' PIP called WWW (Cohen 1999b); and the second compared PIP with interaction guidance (Robert‐Tissot 1996a). We included these studies in analyses of PIP versus an alternative intervention.

One study employed a three‐arm parallel group design in which PIP (also called child‐parent psychotherapy (CPP)) was compared with a psychoeducational parenting intervention (PPI), derived from the preventive home visiting work of David Olds and colleagues (Olds 1998), and a control community standard care condition (Cicchetti 2006b). This three‐arm study contributed data to both analyses of PIP versus control and PIP versus an alternative intervention. To avoid double counting, we split the number of participants in the common group (i.e. the PIP group).

One study employed a randomised four‐arm comparison of routine primary care, non‐directive counselling, CBT, and psychodynamic (PIP) therapy (Cooper 2003a). For the purposes of this review, we aggregated data from the counselling and CBT arms and compared this with the PIP therapy arm, in analyses of PIP versus alternative intervention.

Participants

The eight included studies initially randomised 846 participants. The number of participants randomised in each trial ranged from 59 (Lieberman 1991) to 193 (Cooper 2003a) parent‐infant dyads. The intervention was directed at mothers in all of the included studies (fathers were not excluded in Robert‐Tissot 1996a, but no separate data for the intervention groups was included in the published report or available from the investigator).

In all eight included studies, the mean age of the infant participants was under 24 months at study enrolment. In one study, the infants were eight weeks old at study entry (Cooper 2003a). We included two studies which stated that the age of some the participating infants was 30 months at study entry but the mean age still met our inclusion criteria (in Cohen 1999b, the mean age in the two intervention groups was 21.5 months (SD = 6.5) in the WWW arm and 19.2 months (SD = 6.1) in the PIP ('PPT') arm, range 10‐30 months; in Robert‐Tissot 1996a the mean age at pretreatment assessment was 15.6 months and ranged from 2 to 30 months (SD = 8.4). The report of Lieberman 1991 stated that the intervention was delivered to infants aged 12 months with infants being 11 to 14 months old at study entry. Cicchetti 1999a stated that the mean age of all the infants in the study (i.e. both the intervention and the control groups) was 20.4 months (SD = 2.38); in Cicchetti 2006b the mean age was 13.31 months (SD = 0.81). In Salomonsson 2011a the mean age of the infants was 4.4 months (SD = 2.4) in the PIP group and 5.9 months (SD = 3.8) in the control group; the maximum age of the infants at study entry was less than < 18 months. In Sleed 2013a, infants were aged 1‐23 months in the intervention group with a mean age of 4.9 months (SD = 4.5; range = 0.2‐23.0 months); in the control group, the mean age was 4.4 months (SD = 4.6; range = 0.1‐18.5 months). Cicchetti 1999a, Cicchetti 2006b, and Cooper 2003a did not state the maximum age of the infants at enrolment.

The eight included studies investigated the effectiveness of PIP with a range of clinical groups, including depressed mothers (Cicchetti 1999a; Cooper 2003a); maltreating parents (Cicchetti 2006b); incarcerated mother‐infant dyads (Sleed 2013b); parents experiencing a range of infant problems (Cohen 1999b; Robert‐Tissot 1996a); mothers with concerns about their own role as mothers, well‐being of the infants, or the mother‐infant relationship (Salomonsson 2011a); and parents of infants at risk of anxious attachment because their mothers are emotionally unavailable (Lieberman 1991).

Two studies reported the population groups to be either Caucasians (94.5% Caucasian in Cicchetti 1999a) or European Caucasian infants (Robert‐Tissot 1996a); or in a third study, American Hispanic (recently immigrated from Mexico or Central America) (Lieberman 1999). Three studies reported the proportion of participants from a minority race or ethnicity: in Cicchetti 2006b, overall, 74.1% of the randomised participants were described as minority race or ethnicity (Cicchetti 2006a) and in Sleed 2013a over one‐half were white and the remaining "Asian, Mixed or other"; in Salomonsson 2011a, 11% in the PIP group and 22% in the control group were described as 'immigrant' (Salomonsson 2011a). Two studies did not report participant ethnicity (Cohen 1999b; Cooper 2003a).

Recruitment

Cicchetti 1999a recruited from a community sample of mothers with a history of depressive disorder via referrals from mental health professionals and through notices placed in the community. Cicchetti 2006b recruited maltreating mothers (i.e. child protection services identified infants known to have been maltreated or who were living in maltreating families with the biological mothers). Cooper 2003a recruited from hospital birth records and after screening for mood disturbances. Cohen 1999b and Robert‐Tissot 1996a used referrals made by the parents or by medical mental health and child welfare professionals for feeding, sleeping, and behaviour problems. Lieberman 1991 recruited dyads from paediatric clinics at large teaching hospitals and neighbourhood health clinics, targeting recent Latino immigrants at risk of anxious attachment due to parental unavailability. Sleed 2013a liaised with the mother and baby unit staff of the women's prisons to identify mother‐infant dyads who would be willing to take part. Salomonsson 2011a recruited mothers through information provided at the delivery ward of the hospital and at parenting internet sites.

Interventions

All included studies involved the delivery of PIP, which had its origins in the work of Selma Fraiberg (Fraiberg 1975; Fraiberg 1980), and was based on a psychodynamic model. Only three of the included studies used manualised programmes (Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Sleed 2013a).

Parent‐infant psychotherapy

Lieberman 1991 delivered PIP in unstructured weekly sessions. There was no didactic teaching and the therapists sought to alleviate the mothers' psychological conflicts about their children through observations.

Cicchetti 1999a and Cicchetti 2006b employed manualised infant‐parent psychotherapy. Mothers and their infants attended conjoint therapy sessions. Insights gained by the therapist were used to increase maternal sensitivity, responsivity, and attunement to the child.

In Cohen 1999b, in the PIP ('PPT') arm, the mother and infant played while the therapist's observations were used to draw the mother's attention to her infant's needs and signals. In the infant‐led psychotherapy (WWW), mothers and infants played on the floor, and mothers were instructed to interact only at the infant's initiative. The therapist engaged in a parallel process of 'watching, waiting, wondering' about the interactions between mother and infant and did not intervene.

Salomonsson 2011a also employed a form of infant‐led psychotherapy, in which the analyst received and emotionally processed the infant's distress and communicated it back to the infant in a form that the infant could assimilate, in the presence of the mother.

Robert‐Tissot 1996a employed a method of PIP that was explicitly based on the work of Fraiberg. The therapist listened to the mother's concerns, anxieties and narratives, and examined the relationship between the therapist, mother and infant in terms of the core conflictual relationship between the mother and infant. An emphasis was placed on fostering a positive therapeutic alliance.

Cooper 2003a employed brief psychodynamic parent‐infant therapy, which focused on the therapist exploring the mother's representations of the experience of motherhood in terms of her own experiences of being parented.

Only one study employed a group‐based therapy (Sleed 2013a). "New Beginnings" was conducted over eight sessions that were delivered over a four‐week period. The groups were comprised of up to six mother‐baby dyads and two parent‐infant psychotherapists as facilitators. The topics of each session were selected and examined in terms of their potential as triggers of the attachment relationship.

Further details about the specifics of the psychodynamic therapy, and intervention of all the included studies, can be found in the Characteristics of included studies table.

Duration of intervention

The duration of the therapies ranged from eight sessions (Sleed 2013a) to between 46 and 49 weeks (Cicchetti 2006b).

Site of delivery of intervention

Robert‐Tissot 1996a delivered the intervention and assessed outcomes in a research clinic. Cooper 2003a delivered the intervention in the participants' homes, and Cicchetti 2006b and Lieberman 1991 delivered the intervention in the client's home and the assessment of outcome in university research facilities. Cohen 1999b delivered the intervention in a playroom at a children's mental health centre. Sleed 2013a delivered the intervention in the mother and baby units of several women's prisons in the UK. It is unclear where Salomonsson 2011a and Cicchetti 1999a delivered the intervention, although outcome assessments were made in the research clinic setting.

Monitoring treatment fidelity

The delivery of the intervention was monitored in all included studies and therapists were highly trained and supervised during the intervention.

Comparisons

Four studies compared PIP with a treatment‐as‐usual control condition (Cicchetti 1999a; Lieberman 1991; Salomonsson 2011a; Sleed 2013a). The control condition in Cicchetti 1999a was not described but assumed to be treatment‐as‐usual in which all participants were able to access other mental health treatments; and in Lieberman 1991 was not described but assumed to be normal service provision. In Sleed 2013a, mothers and babies in both groups had access to standard health and social care provision as provided by the prison service. In Salomonsson 2011a, the control condition involved access to the local child health centre responsible for check‐ups from birth to six years of age, antidepressants, and brief psychotherapies.

Two studies compared PIP with alternative interventions, including a behavioural and infant‐led PIP (i.e. WWW) (Cohen 1999b); and Interaction Guidance (Robert‐Tissot 1996a).

One study employed a three‐arm trial design in which PIP was compared with a home visitation intervention delivered over 12 months (i.e. a preventive intervention, involving home visitations scheduled weekly over a 12‐month period) and a treatment‐as‐usual control (Cicchetti 2006b).

Cooper 2003a employed a four‐arm study in which PIP was compared with a control condition (i.e. routine primary care provided by the primary healthcare team), and two alternative interventions (CBT and non‐directive counselling).

Outcomes

Timing of outcome assessment

In Cicchetti 1999a, post‐intervention outcomes were assessed when the child was 36 months of age. In Cicchetti 2006b, all outcomes were assessed at post‐intervention (i.e. when the children were aged 26 months) (Stronach 2013), but cortisol levels were assessed at 12 months' follow‐up (when the children were approximately 38 months of age) (Cicchetti 2011a). Cohen 1999b reported outcomes at post‐intervention and six‐month follow‐up (Cohen 2002). Lieberman 1991 assessed outcomes at post‐intervention (24 months of age). Robert‐Tissot 1996a assessed outcomes immediately post‐intervention and at six‐month follow‐up (when the children were approximately 26 months of age). Long‐term follow‐up interviews at pre‐adolescence were also reported (Cramer 2002), but the results were not presented separately for the intervention groups and we were unable to obtain further information. Sleed 2013a assessed outcomes immediately post‐intervention (range one to 25 months of age) and two months after the end of treatment when the infants were three to 27 months of age. Cooper 2003a presented results immediately post‐intervention and at nine‐month, 18‐month and five‐year follow‐up. Salomonsson 2011a reported post‐intervention outcomes only.

Outcomes

The included studies reported a range of outcomes relating to parental mental health, parent‐infant interactions and infant development (i.e. attachment, behaviour, cognitive, and mental development).

Primary outcomes

Parent outcome

Five studies measured maternal depression using a number of self report measures (e.g. BDI; Beck 1978) (Cicchetti 1999a; Cohen 1999b), Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Salomonsson 2011a), and Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES‐D) (Sleed 2013a). In two studies, the number of number of depressive episodes was reported using criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ‐ Third Edition ‐ Revised (DSM‐III‐R) (Cohen 1999b; Cooper 2003a).

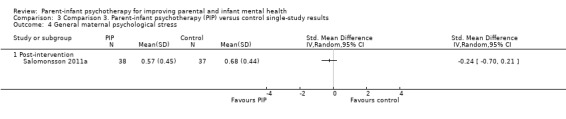

Cohen 1999b measured parent stress using the PSI (Abidin 1986), and parenting sense of competence using the Parenting Sense of Competence (PSOC) scale (Johnston 1989). Salomonsson 2011a reported scores on the Swedish equivalent of the PSI (the Swedish Parenting Stress Questionnaire; SPSQ) and a measure of general psychological stress, the General Severity Index (GSI) of the Symptom Checklist ‐ 90 (SCL‐90) (Derogatis 1994).

Parent‐infant relationship outcomes

Six studies measured mother‐infant interaction during play using video‐taped sessions, which were then analysed and coded. Cohen 1999b measured dyadic reciprocity, dyadic conflict, maternal intrusiveness, and maternal unresponsiveness using the Chatoor Play Scale (Chatoor 1986). Lieberman 1991 measured maternal initiation of interaction, behaviour on reunion (goal‐corrected partnership) and maternal child‐rearing attitudes (control aggression, encourage reciprocity and awareness of complexity in child rearing). Robert‐Tissot 1996a measured controlling or unresponsive behaviour using the CARE‐Index (Crittenden 1981). Sleed 2013a used the Coding Interactive Behavior (CIB) for parent positive engagement and child involvement. Cooper 2003a assessed maternal warmth, responsiveness, and acceptance using the Global Rating Scales (GRS; Murray 1996). Salomonsson 2011a assessed sensitivity, structuring, non‐intrusiveness and non‐hostility; and two infant dimensions: responsiveness and involvement using the EAS.

Robert‐Tissot 1996a measured maternal sensitivity using the CARE‐Index (Crittenden 1981); Lieberman 1991 measured maternal empathic responsiveness (sensitivity) coded from video‐taped free‐play measures; and Sleed 2013a used the CIB for dyadic attunement/maternal sensitivity. Cooper 2003a assessed maternal sensitivity using the GRS (Murray 1996). Salomonsson 2011a assessed sensitivity using the EAS.

Infant outcomes

Five studies measured infant attachment (Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Cohen 1999b; Cooper 2003a; Lieberman 1991). Cicchetti 1999a used the Attachment Q‐Set (AQS) (Waters 1995). Three studies assessed infant attachment using the SSP (Cicchetti 2006b; Cohen 1999b; Cooper 2003a). The SSP categorises infant attachment styles into one of four classifications: secure, insecure avoidant, insecure resistant or disorganised attachment (Ainsworth 1971). Secure attachment is a favourable outcome. Lieberman 1991 measured security of attachment using the 90‐item Attachment Q‐sort, which is a refinement of the original Q‐set (AQS) (Waters 1985), and is an observation‐based report, obtained by home visitors at follow‐up only. Lieberman 1991 also assessed dyadic behaviour on reunion, proximity avoidance and resistance, behaviour on reunion and goal‐corrected partnership, using the Ainsworth Interactive Behaviour Scales (modelled on the SSP but with 10‐minute episodes suitable for younger children; Ainsworth 1978).

One study assessed the mean number of angry or externalising behaviours and restriction of affect using a non‐standardised rating of video‐taped interactions (Lieberman 1999). One study used the Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; Achenbach 1992) (Cicchetti 2006b). One study measured infant behaviour using the Behavioural Screening Questionnaire (BSQ), and the Rutter Parent A2 Scale (maternal report) and Parent Behavior Checklist (PBCL ‐ teacher report) (Cooper 2003a).

Adverse effects

Three studies (Cicchetti 1999a; Cicchetti 2006b; Cohen 1999b) measured adverse effects in terms of the potential adverse impact of the intervention on attachment security (i.e. measured change from secure to insecure attachment).

Secondary outcomes

Parent outcomes

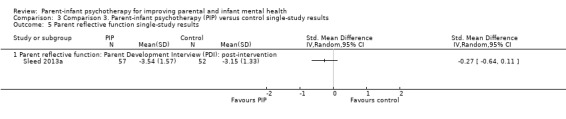

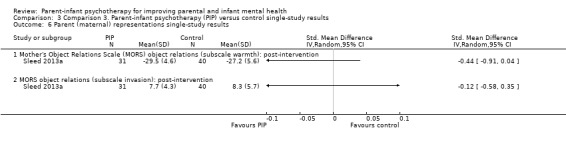

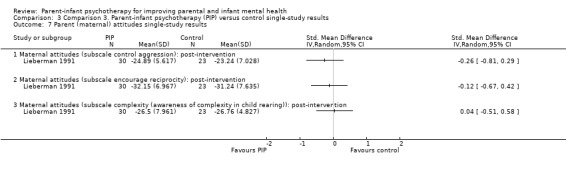

One study measured maternal representations using the Mother's Object Relations Scale (MORS) (Danis 2005; a self‐report measure) and the PDI (Slade 2004; a structured interview, objective report) (Sleed 2013a); and one study measured maternal attitudes using the Egeland 1979 abbreviated version of the Maternal Attitude Scale (MAS; Cohler 1970) (Lieberman 1991).

Infant outcomes

In one study, infant symptoms were obtained by asking the mother to list the primary problems present at the time of referral for help and to rate these on a 100‐point scale for severity, degree of difficulty, and perceptions of effectiveness and comfort in dealing with problems (Cohen 1999b).

Infant functioning and cognitive development were measured in Cohen 1999b using the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID) I or II (Bayley 1969; Bayley 1993), to derive a Developmental Quotient (DQ); and the BSID Mental Development Index (MDI) (Bayley 1969) in Cooper 2003a. The infant's cognitive development (infant IQ) was assessed in Cicchetti 1999a using the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence (WPPSI‐R; Wechsler 1989). Salomonsson 2011a measured infant functioning using the Ages and Stages Questionnaire (ASQ).

Cicchetti 2006b measured infant stress using samples of morning salivary cortisol (expressed as micrograms per decilitre; μg/dL), but the results were aggregated for both intervention groups and we were unable to obtain disaggregated data.

Excluded studies

We formally excluded 58 studies, details of which can be found in the Characteristics of excluded studies table. Of these, eight were RCTs but did not fit our inclusion criteria. Twenty‐one were not RCTs but otherwise met at least one of our inclusion criteria. Twenty‐five studies did not assess the effectiveness of PIP. In three RCTs of PIP (Lieberman 2005; Smyrnios 1993; Toth 2002), the age of the children was outside the maximum age specified in the inclusion criteria for this review.

Risk of bias in included studies

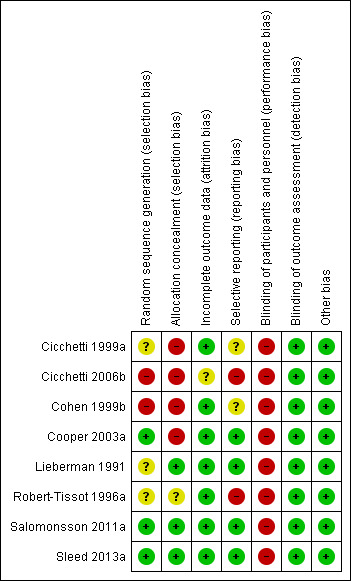

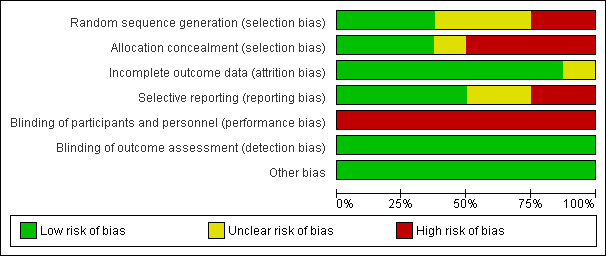

We presented the 'Risk of bias' tables for each included study beneath the Characteristics of included studies table. Figure 2 shows a summary of risk of bias across all studies; Figure 3 shows the results as percentages. For all studies rated as unclear risk of bias, when contacted, the study investigators were unable to provide further details.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies

Allocation

We judged three of the included studies as being at low risk of bias because adequate methods were used to generate the randomisation sequence (Cooper 2003a; Salomonsson 2011a; Sleed 2013a).

The method used to generate the randomisation sequence in Robert‐Tissot 1996a was unclear. Cicchetti 1999a and Lieberman 1991 used block randomisation procedures; they assigned infants to the intervention of control group by blocks stratified for infant sex and birth order (first, later), but the method of randomisation was unclear.

In Cicchetti 2006b, we judged the risk of bias due to randomisation methods as high because some of the control participants who were originally assigned to PPI or infant‐parent psychotherapy (IPP; also called CPP) declined, and the study investigators presented results for this group of decliners in the same group as the community standard care randomised group. We judged Cohen 1999b to be at high risk of bias for random sequence generation because randomisation was inadequate in one‐third of the cases in which assignment was dependent on therapist caseload and availability for time of treatment; in two‐thirds of the cases, assignment was done using a random numbers table.

Three studies concealed allocation sequence (Lieberman 1991; Salomonsson 2011a; Sleed 2013a). In one study, we could not obtain details about allocation concealment (Robert‐Tissot 1996a), and we rated this as unclear. We judged four studies to be at high risk of bias in terms of allocation concealment: Cicchetti 1999a and Cicchetti 2006b did not use a preset allocation sequence; Cohen 1999b did not provide details about allocation concealment, and allocation of one‐third of the participants was based on therapist availability (therefore, it could not have been concealed); and the allocation sequence was not concealed in Cooper 2003a.

Blinding

Performance bias

Due to the nature of the interventions, it was not possible to blind both the participants and personnel to group allocation.

Detection bias

We rated blinding of outcome assessment as low in all of the included studies. Although it is not possible to blind participants and personnel to the allocation given the nature of the treatment, the investigators of the included studies made efforts to ensure that, where possible, those who were involved in the measurement of outcomes were blind to the initial allocation. For four studies, the blinding of outcome assessors was complete. In Robert‐Tissot 1996a, the researchers who coded mother‐infant interactions and analysed and coded the responses to the different questionnaires were blind to the treatment condition. In Cooper 2003a, the outcome assessors were blinded to the allocation. In Sleed 2013a, coders were blind for PDI, and CIB coding was carried out by trained coders who were blind to both the group and time point. In Cicchetti 1999a, outcome assessment was conducted with toddlers, with their mothers present, by an experimenter unaware of experimental hypotheses and the diagnostic and intervention status of participants in the study.