Abstract

Background

Transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive (TGE) people face barriers to abortion care and may consider abortion without clinical supervision.

Methods

In 2019, we recruited participants for an online survey about sexual and reproductive health. Eligible participants were TGE people assigned female or intersex at birth, 18 years and older, from across the United States, and recruited through The PRIDE Study or via online and in-person postings.

Results

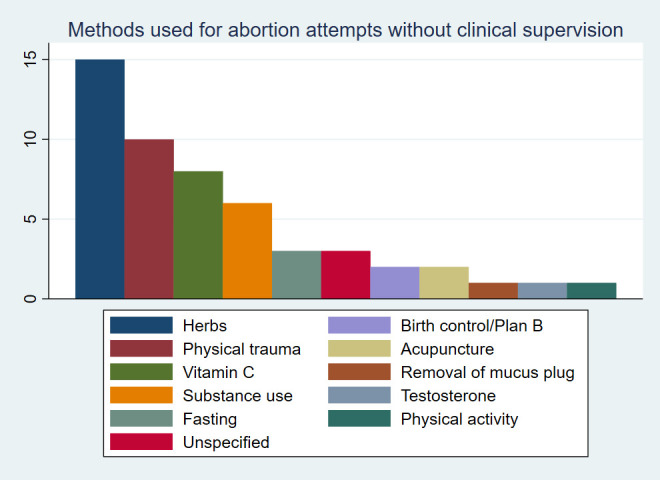

Of 1694 TGE participants, 76 people (36% of those ever pregnant) reported considering trying to end a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision, and a subset of these (n=40; 19% of those ever pregnant) reported attempting to do so. Methods fell into four broad categories: herbs (n=15, 38%), physical trauma (n=10, 25%), vitamin C (n=8, 20%) and substance use (n=7, 18%). Reasons given for abortion without clinical supervision ranged from perceived efficiency and desire for privacy, to structural issues including a lack of health insurance coverage, legal restrictions, denials of or mistreatment within clinical care, and cost.

Conclusions

These data highlight a high proportion of sampled TGE people who have attempted abortion without clinical supervision. This could reflect formidable barriers to facility-based abortion care as well as a strong desire for privacy and autonomy in the abortion process. Efforts are needed to connect TGE people with information on safe and effective methods of self-managed abortion and to dismantle barriers to clinical abortion care so that TGE people may freely choose a safe, effective abortion in either setting.

Keywords: abortion, induced, abortifacient agents, reproductive health, family planning services, reproductive rights, abortion, criminal

Key messages.

Transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive (TGE) people face structural and social barriers to clinical abortion care.

Nearly one in five TGE respondents who had ever been pregnant reported an attempt to end a pregnancy without clinical supervision.

Efforts are needed to connect TGE people with information on safe and effective methods of self-managed abortion and to dismantle barriers to clinical abortion care.

Introduction

Transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive (TGE) people (box 1) in the United States (US) plan for, carry and terminate pregnancies.1 2 At least 0.4%–0.6% of adults in the US identify as transgender.3 4 Many TGE people assigned female sex at birth and people with intersex conditions have and retain a uterus, ovaries and fallopian tubes,5–7 and some report sexual intercourse with sperm-producing partners.8 9 As a result, many TGE individuals and people with intersex conditions need pregnancy and abortion care. Yet, the specific family planning needs – particularly abortion – of these populations have been inadequately characterised.2 10 11

Box 1. Definitions of key terms.

Agender describes a person who does not identify with any gender identity, or whose gender identity is undefinable.

Cisgender describes a person whose gender identity aligns with the gender commonly associated with the sex that they were assigned at birth.

Intersex describes people assigned intersex at birth or who identify as intersex and have “natural variations in sex characteristics that do not seem to fit typical binary notions of male or female bodies”.39 These variations do not necessarily impact capacity for pregnancy.

Genderfluid describes a person whose gender identity changes over time.

Nonbinary and gender-expansive are overlapping terms that describe gender identities that are not limited to man or woman – this could be a combination of both or neither. Some individuals who identify as nonbinary and/or gender-expansive may also identify as transgender; some may not.

Transgender describes a person whose gender identity (eg, agender, man, nonbinary, woman) differs from the gender commonly associated with the sex that they were assigned at birth (ie, female, intersex, male).

TGE people face barriers to abortion care. These barriers include policy restrictions, as well as logistical factors including distance to the nearest provider, cost and time off from work.12 13 Compounding these barriers, TGE people additionally face limited healthcare provider knowledge, refusals, discrimination, and misgendering as a result of transphobia and cissexism.10 14

Self-managed abortion describes an attempt by a person to end a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision.15 Recent research has focused on demonstrating the effectiveness and safety of self-managed abortion with standardised abortifacient medications – specifically, misoprostol and mifepristone.16–19 While self-managed medication abortion using mifepristone and/or misoprostol is safe and effective,16 18–23 other methods – such as physical trauma and substance use – are known to be harmful, or lack reliable evidence.15 18 People attempt to end their pregnancies without clinical support for many reasons, including an inability to access clinic-based abortion care; fear of stigma or mistreatment within clinical settings18; a preference for ending a pregnancy in the privacy and comfort of a place of one’s choosing; and a preference for using methods not associated with contemporary allopathic medicine.24

Within the US, 1.2%–6.9% of clinic-based abortion patients report a prior attempt to end a pregnancy without clinical supervision.17 25 The proportion who attempt to do so may be higher among the general population of pregnant people;26 indeed, a nationally representative survey in the US estimated the lifetime prevalence of self-managed abortion at 7%.27 As the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic has restricted movement, forced clinic closures and disrupted livelihoods and contraceptive supply chains, conditions that lead to unintended pregnancy have been exacerbated.28 Consequently, the need for abortion may be higher than before, while access to clinical care is simultaneously more restricted.28 The need or preference for ending a pregnancy without clinical supervision may be particularly pronounced among marginalised TGE communities for whom barriers to care are already more formidable.10 11

We previously reported that 12% of a large sample of TGE respondents in the US reported at least one prior pregnancy;29 21% of these pregnancies ended in abortion.2 Estimates suggest that 462–530 transgender and nonbinary people had a facility-based abortion in the US in 2017;30 however, to our knowledge, no data exist on abortion attempts or experiences among TGE populations that happen outside of clinical settings. To improve understanding of the universe of abortion experiences among TGE people in the US, we conducted a national quantitative survey. We hypothesised that TGE people would report considering and attempting abortion without clinical supervision.

Methods

Study population

Between May and September 2019, we fielded an online survey about the sexual and reproductive health experiences, needs and preferences of TGE individuals who were assigned female or intersex at birth in the US. Eligible participants came from two sources: (1) the general public and (2) participants enrolled in The Population Research in Identity and Disparities for Equality (PRIDE) Study, an online national prospective cohort study of sexual and/or gender minority adults. The research platform, design and participant population of The PRIDE Study are documented elsewhere.31 Across both populations, eligible participants included any TGE person who was assigned female or intersex at birth, who was 18 years or older, resided in the US or its territories and could read and understand English. Participants from the general public were recruited via social media, in-person TGE community events, academic conferences and the study website. Participants from The PRIDE study were recruited to this survey from their personalised PRIDE study dashboard after direct notification by email and/or text message.

Data collection

We designed and administered the survey through Qualtrics (Qualtrics; Provo, UT, USA). Survey domains included pregnancy history, abortion history and sociodemographic characteristics. We programmed the survey to allow participants to input the terminology they used for their own bodies, and then displayed these terms back to the respondent in relevant survey questions. Further discussion of these methods and the full-text survey are previously published.32 A Community Advisory Team of TGE individuals, as well as the Research and Participant Advisory Committees of The PRIDE Study, co-developed and tested the survey questions with the core research team through a collaborative and iterative survey design process. We utilised Qualtrics’s features to guard against multiple responses from the same device using the same browser. On completing the survey, participants were entered into a raffle to win a US$50 electronic gift card; a total of US$5000 in gift cards was distributed.

Measures

Survey variables analysed herein included respondent sociodemographic characteristics, pregnancy history, and experiences considering or attempting to end a pregnancy without clinical supervision. Participants could share additional details in an open-ended question (box 2).

Box 2. Survey questions assessing respondent experiences with abortion without clinical supervision.

People make different choices about how to end an unwanted pregnancy. Some people may go to a hospital, clinic or doctor’s office to have an abortion, while other people may get information from the internet, a friend or a family member about medicines or herbs they can take on their own, or they may do something else to try to end a pregnancy on their own.

Have you ever CONSIDERED trying to end a pregnancy on your own, without medical supervision? (Yes/No)

Have you ever ATTEMPTED trying to end a pregnancy on your own, without medical supervision? (Yes/No)

Please tell us in your own words about how you attempted to end your pregnancy without medical supervision. (Free response)

Sociodemographic characteristics measured included age at the time of the survey, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, intersex identity, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, education level, health insurance coverage and zip code. We recoded zip codes into US Census Bureau regions. Multiple selections were allowed for gender identity, sexual orientation and race/ethnicity as well as writing in additional responses for gender identity and sexual orientation. Any respondent who reported a gender identity or qualifier other than “woman” or “cisgender woman” (in free text or provided answer choices) and who also reported being assigned female or intersex at birth was considered to be a TGE person.

Data analysis

We used Stata 15.1 (StataCorp; College Station, TX, USA) to analyse responses to closed-ended questions. We calculated frequencies and percentages for all study measures for the full study sample, and separately for those who reported a pregnancy, reported any abortion, considered ending a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision, and attempted to end a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision. We summarised and described all reported attempts (regardless of abortion success). We used Microsoft Excel to analyse open-ended responses. Specifically, we categorised write-in responses based on three a priori identified themes – the rationale for, methods of, and outcome of the abortion attempt(s) – and iteratively looked for patterns across responses.

Ethical review

The Institutional Review Boards of Stanford University and the University of California, San Francisco provided ethical review and approval for the study. All participants indicated their informed consent to participate prior to viewing the survey questions.

Patient and public involvement

To ensure that this study represented the needs and interests of TGE community members, we recruited individual members of the public who identified as TGE for a community advisory team to contribute to the design, conduct, reporting and dissemination of the study.32

Results

Characteristics of the study population

Overall, 1694 TGE respdonents provided reproductive history data. These survey respondents were young (median 27 years, IQR 23–33 years), primarily white, and had a range of gender identities and sexual orientations (table 1). Of 210 respondents who had ever been pregnant, 76 (36%) reported considering abortion without clinical support, and a subset of these (n=40, 19%) reported attempting abortion without clinical support. Among respondents who reported attempting abortion without clinical supervision the median age was 32 (IQR 28–38) years, nearly all were insured, most identified as white, 40% were parents and 59% had completed 4 years at college or a graduate degree. The most common gender identities in this subset were genderqueer, nonbinary, and transgender man; most participants (75%) identified with “queer” as their sexual orientation, and four participants (10%) identified as intersex.

Table 1.

Respondent sociodemographic characteristics, overall and by abortion history, in an online sample of transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive (TGE) individuals assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States (n=1694)

| Sample characteristics | All respondents (n=1694) |

Reported a pregnancy (n=210) | Reported an abortion (n=67) |

Reported considering non-clinical abortion (n=76) |

Reported attempting

non-clinical abortion (n=40) |

|||||

| Median age (IQR) (years) | 27 | (23–33) | 35 | (29–42) | 33 | (27–41) | 32 | (27–38) | 32 | (28–38) |

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age categories (years) | ||||||||||

| 18–19 | 150 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–24 | 469 | 28 | 21 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 12 | 16 | 6 | 15 |

| 25–29 | 447 | 26 | 38 | 18 | 15 | 22 | 17 | 22 | 9 | 23 |

| 30–34 | 284 | 17 | 44 | 21 | 12 | 18 | 16 | 21 | 10 | 25 |

| 35–39 | 149 | 9 | 39 | 19 | 12 | 18 | 14 | 18 | 9 | 23 |

| 40–44 | 88 | 5 | 28 | 13 | 7 | 10 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 8 |

| 45–49 | 38 | 2 | 13 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 50–54 | 31 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 55–59 | 20 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| 60–79 | 18 | 1 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender identity* | ||||||||||

| Agender | 226 | 13 | 34 | 16 | 16 | 24 | 15 | 20 | 7 | 18 |

| Cisgender man† | 1 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cisgender woman‡ | 94 | 6 | 17 | 8 | 4 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Genderqueer | 655 | 39 | 95 | 45 | 34 | 51 | 39 | 51 | 22 | 55 |

| Man | 293 | 17 | 19 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 8 | 11 | 7 | 18 |

| Nonbinary | 868 | 51 | 110 | 52 | 42 | 63 | 49 | 65 | 23 | 58 |

| Transgender man | 662 | 39 | 70 | 33 | 26 | 39 | 24 | 32 | 15 | 38 |

| Transgender woman | 4 | 0.2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Two-spirit | 26 | 2 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Woman‡ | 204 | 12 | 20 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 8 |

| Additional gender identity | 197 | 12 | 24 | 11 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 15 |

| Prefer not to say | 2 | 0.1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple gender identities | 1036 | 61 | 118 | 56 | 42 | 63 | 49 | 65 | 29 | 73 |

| Sex assigned at birth | ||||||||||

| Female | 1684 | 99 | 208 | 99 | 67 | 100 | 75 | 99 | 39 | 98 |

| Not listed | 10 | 0.6 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Identifies as intersex | ||||||||||

| Yes | 69 | 4 | 12 | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 10 |

| Prefer not to say | 21 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sexual orientation* | ||||||||||

| Asexual | 252 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 5 | 8 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 13 |

| Bisexual | 571 | 34 | 68 | 32 | 24 | 36 | 23 | 30 | 11 | 28 |

| Gay | 348 | 21 | 47 | 22 | 16 | 24 | 16 | 21 | 12 | 30 |

| Lesbian | 218 | 13 | 26 | 12 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Pansexual | 418 | 25 | 74 | 35 | 29 | 43 | 25 | 33 | 11 | 28 |

| Queer | 1150 | 68 | 142 | 68 | 50 | 75 | 58 | 76 | 30 | 75 |

| Questioning | 69 | 4 | 7 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Same-gender loving | 111 | 7 | 17 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Straight/heterosexual | 61 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Another sexual orientation | 129 | 8 | 17 | 8 | 6 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 3 | 8 |

| Missing | 21 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple sexual orientations | 1010 | 60 | 126 | 60 | 44 | 66 | 45 | 59 | 24 | 60 |

| Race/ethnicity* | ||||||||||

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 42 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 13 |

| Asian, Central | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian, East | 41 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Asian, South | 19 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 8 |

| Asian, Southeast | 25 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Black or African American | 67 | 4 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 101 | 6 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 8 |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 24 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander | 5 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| White | 1472 | 87 | 190 | 91 | 65 | 97 | 67 | 88 | 35 | 88 |

| Unknown | 12 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Another race | 41 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| None of these | 4 | 0.2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| Missing | 79 | 5 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Multiple racial/ethnic identities | 202 | 12 | 34 | 16 | 13 | 19 | 15 | 20 | 10 | 25 |

| Education level | ||||||||||

| High school degree or less | 141 | 8 | 13 | 6 | 6 | 9 | 9 | 12 | 5 | 13 |

| Some college, trade or technical school | 410 | 24 | 54 | 26 | 18 | 27 | 17 | 22 | 11 | 28 |

| College degree | 519 | 31 | 64 | 31 | 16 | 24 | 18 | 24 | 7 | 18 |

| Some graduate or professional study | 125 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Graduate or professional degree | 410 | 24 | 71 | 34 | 23 | 34 | 25 | 33 | 15 | 38 |

| Missing | 89 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 |

| Has health insurance | ||||||||||

| Yes | 1512 | 89 | 190 | 90 | 62 | 93 | 71 | 93 | 38 | 95 |

| No | 92 | 5 | 12 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 5 |

| Prefer not to say | 10 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Missing | 80 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| United States Census region | ||||||||||

| Midwest | 304 | 18 | 34 | 16 | 13 | 19 | 14 | 18 | 10 | 25 |

| Northeast | 411 | 24 | 45 | 21 | 14 | 21 | 18 | 224 | 8 | 20 |

| South | 326 | 19 | 44 | 21 | 11 | 16 | 16 | 21 | 10 | 25 |

| West | 468 | 28 | 66 | 31 | 22 | 33 | 23 | 30 | 11 | 28 |

| Missing | 185 | 11 | 21 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 3 |

| Ever pregnant | 210 | 12 | 210 | 100 | 67 | 100 | 76 | 100 | 40 | 100 |

| Is a parent | ||||||||||

| Yes | 200 | 12 | 113 | 54 | 20 | 30 | 34 | 45 | 16 | 40 |

| No | 1420 | 84 | 92 | 44 | 46 | 69 | 41 | 54 | 24 | 60 |

| Missing | 74 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

*Respondents could select multiple responses for gender identity, sexual orientation and race/ethnicity. Categories include anyone who selected that option and, as such, respondents can be represented in more than one category for each of these characteristics.

†The respondent who selected “cisgender man” was assigned female sex at birth and was eligible to participate.

‡Respondents who selected “cisgender woman” and/or “woman” also selected at least one other gender identity other than “cisgender woman” or “woman”.

Methods and outcomes for abortion attempts without clinical supervision

Among the 40 respondents who reported ever attempting to end a pregnancy without clinical supervision, 35 (88%) described one or more methods used to do so. Methods reported fell into four broad categories: herbs (n=15, 38%), physical trauma (n=10, 25%), vitamin C (n=8, 20%) and substance use (n=7, 18%) (figure 1). Two of the ten individuals classified as using physical trauma reported either “uterine massage” or pressing “firmly” on their abdomen; other examples referenced insertion of objects such as the following: “I tried sticking a needle into my front hole” (man/transgender man respondent; Middle Eastern/North African; Northeastern US). Less frequently mentioned methods included fasting (n=3, 8%), acupuncture (n=2, 5%), use of birth control or emergency contraception (n=2, 5%), continued use of testosterone (n=1, 3%), manual attempts to remove the mucus plug (n=1, 3%) and excessive physical activity (n=1, 3%). Four participants reported searching online for methods to end their pregnancy (10%): one used vitamin C, one used herbs, and two did not report the method used.

Figure 1.

Methods used for abortion attempts without clinical supervision reported in an online sample of transgender, nonbinary and gender-expansive (TGE) individuals assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States (n=40 of 1694 respondents reported an abortion attempt without clinical supervision).

In write-in responses, 13 (33%) respondents shared the outcome of one or more abortion attempts from 14 pregnancies: nine pregnancies ended in miscarriage or the return of menses, four ended in a subsequent clinic-based abortion after their initial abortion attempt failed and one ended in birth. A participant who reported a miscarriage wrote:

I drank a lot of alcohol, took a mild overdose of my prescriptions, repeatedly hit my lower abdomen with a hammer, and then stopped eating for a few days. At the end of the week, I miscarried. [Genderfluid/genderqueer/nonbinary respondent; identified as intersex; white; region unknown]

Another respondent, for whom the abortion attempt was unsuccessful, described their experience:

I'd rather not share the details. It did not work, the pregnancy ended in a slightly premature healthy baby whom I am primary caregiver for (love him, don't regret him, but do regret not being able to access abortion). [Genderqueer/nonbinary respondent; identified as intersex; white; Western US]

Context of abortion attempts without clinical supervision

In open-ended responses (box 3), several respondents described their reasons for attempting to end a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision, including barriers to clinical care such as insurance coverage, gestational age limits, provider bias, as well as complications from comorbidities or the fear of a partner finding out. Other participants did not provide a reason. Some participants described more than one pregnancy for which abortion was attempted without clinical supervision. Five respondents (13%) described difficult situations that influenced their attempt to end a pregnancy without clinical supervision, including suicide attempts, intimate partner violence or other physical harm, or fear of harm to themselves. Some responses indicated a fear for personal safety if anyone discovered the pregnancy – a fear that precluded the respondent from seeking care from a clinician at a health facility.

Box 3. Free-text responses about the context surrounding their abortion attempt without clinical supervision.

Respondents who attempted abortion on their own after being denied clinical care

“I was denied access to abortion for a tubal pregnancy by a Christian doctor for my third pregnancy. I attempted to use herbs and acupuncture and uterine massage to end that pregnancy. Eventually able to get to [clinic name] for termination. Had infection and complications due to delay.” [Genderqueer/man/transgender man respondent; Middle Eastern/North African, white; region unknown]

“I was raped, and refused abortion access as I was past [state’s] cut off (with my [comorbidity], I didn't discover my pregnancy till 16 weeks). I ingested copious amount of black and blue cohosh to induce uterine contractions, used evening primrose oil to soften my cervix, then attempted to remove my mucus plug manually.” [Genderfluid/pangender/two-spirit respondent; Cherokee; Midwestern US]

Respondents who attempted abortion on their own without accessing clinical care

“I tested pregnant with three brands of sticks, I used them at work and school and the store bathroom so he wouldn’t see. I couldn’t go to the doctor to confirm it. I was terrified I would be killed. I looked and read online about the things people try, I did a lot to make myself very sick very quickly. It was stupid, I could have died. I spent a day and a half unconscious or crying in the bathroom I felt so sick, more in bed. The funny thing is he acted concerned. I cleaned it all off of me and felt lucky. I had a normal period a couple months after.” [Agender/genderqueer/nonbinary respondent; white; Western US]

“[I used] blunt force to abdomen. Considered drinking poison, as my insurance did not cover an abortion. Luckily, I was able to get on state insurance which did cover the procedure, so it did not come to that. I 100% would have done it. Dying was a better alternative to forced pregnancy.” [Nonbinary respondent; white; Western US]

Discussion

In a national survey of TGE people assigned female or intersex at birth who had been pregnant, we found that more than one in three respondents had considered ending a pregnancy on their own without clinical supervision, and that nearly one in five had attempted to do so. Reported abortion methods ranged from ingesting herbs and vitamin C to physical trauma to testosterone use, among other unsafe or ineffective methods. Notably, not a single person reported using misoprostol or mifepristone – the World Health Organization (WHO)-recommended abortion medications – to self-manage an abortion.33 This may reflect a need for accurate information about medication abortion, as well as a lack of information about the safety and effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion,20 and how to access these medications.

This study is limited by convenience sampling, as no population-based sampling frame exists for TGE people assigned female or intersex at birth. Thus, the results may not be representative of all TGE experiences with attempting abortion without clinical supervision in the US. Further, while 22% of respondents identified with a race or ethnicity other than “white”, representation from some racial and ethnic groups was low. Given established disparities in access to clinic-based abortion34 this limitation is particularly relevant. Additionally, because we measured age and other sociodemographic characteristics at the time of survey initiation and not at the time of the abortion attempt, we cannot tie these characteristics to any specific abortion attempt. Similarly, we did not ask whether respondents identified as TGE at the time of their pregnancy, which limited our ability to assess the role of transphobia and cissexism in their abortion experience.

The strengths of this study balance the limitations. This is the largest existing sample of TGE people reporting on abortion attempts without clinical supervision. The study had integral involvement of several community advisory teams comprised of TGE individuals and recruitment from community-dwelling as opposed to clinic-based populations.

Our findings indicate that barriers to clinical abortion care may lead to TGE individuals attempting to utilise alternative abortion methods (some safe, some highly unsafe) without clinical supervision. This choice was sometimes made out of preference for non-clinical methods; but in more instances, the decision was made because clinical care was not a safe or accessible option. Efforts are needed to amplify organisations and platforms that provide high-quality, evidence-based information about self-managed medication abortion options, such as Abortion On Our Own Terms, as well as mobile phone apps such as Euki. Beyond medications, many community-based networks use herbs to induce abortion; peer-reviewed data on the safety and effectiveness of these herbal methods are needed.18 For some TGE people, self-managed medication abortion information may empower them to have a safe, effective abortion in the setting and circumstances of their choosing. For others, self-managed medication abortion is a critical harm reduction strategy when an abortion is needed, but clinical care is inaccessible.

In parallel, many systemic barriers need to be dismantled to ensure that clinical abortion care is an accessible and affirming option for all TGE people. Abortion providers should implement steps to improve the inclusivity of abortion clinics for TGE patients, such as adopting gender-neutral intake forms and signage as well as using gender-inclusive language (eg, “people” or “individuals” instead of “women”).11 35 Further, clinicians and counsellors could benefit from training on providing inclusive and affirming abortion care for TGE people.36 37 At the policy level, the long called-for issue of expanding health insurance coverage to cover the costs of abortion care could address reported financial barriers.13 Increasing awareness of and removing barriers to medication abortion via telemedicine may be particularly impactful for TGE communities, as telemedicine may reduce logistical and discriminatory barriers to clinical abortion care while providing access to a preferred method of abortion.2 38

Conclusions

Data from our study provide new and critical insights about non-clinical abortion experiences among TGE people including the nuanced and often fraught contexts in which abortion attempts take place. The reported experiences highlight systemic discrimination and barriers to abortion care for TGE individuals that clinicians, researchers, policymakers and advocates must urgently work to address. Building on the findings of this study, additional research is needed to understand how to facilitate information access so that any person who chooses to self-manage an abortion has the information to do so safely and effectively.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Amy Allina for her thoughtful review of this manuscript, and to Marguerite Campbell, Lyndon Cudlitz, Mary Durden, Anna Katz, Avery Lesser-Lee, Laz Letcher and Anei Reyes for their support in developing the survey and preparing results. The authors acknowledge the courage and dedication of The PRIDE Study participants for sharing their stories; the careful attention of PRIDEnet Participant Advisory Committee (PAC) members for reviewing and improving every study application; and the enthusiastic engagement of PRIDEnet Ambassadors and Community Partners for bringing thoughtful perspectives as well as promoting enrollment and disseminating findings. For more information, please visit https://pridestudy.org/pridenet.

Footnotes

Contributors: HM, LF, JH, JO-M and AS conceived of the study and obtained funding. HM, LF, JH, JO-M, AS, MRL and EAG designed the survey instrument. HM, LF, JH, JO-M, AS, EAG, MRL, AF, MRC and MEL supported recruitment. HM, JO-M and MRL managed data collection. HM, LF and SR conducted analyses. HM wrote the initial draft with revisions and additional writing contributions from all authors: HM, JO-M, CG, EAG, MRL, SR, LF, JH, AS, AF, MRC and MEL.

Funding: AS, CG, HM, JH, JO-M, LF and SR were partially supported by the Society of Family Planning (Grant Number SFPRF11-II1). AF was partially supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (Grant Number K23DA039800). JO-M was partially supported by the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive, and Kidney Disorders (Grant Number K12DK111028). MRC was partially supported by a Clinical Research Training Fellowship from the American Academy of Neurology and the Tourette Association of America. Research reported in this article was partially funded through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Award (Award Number PPRN-1501-26848) to MRL. The statements in this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, nor of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: MRL has consulted for Hims, Inc. (2019–present) and Folx, Inc. (2020). JO-M has consulted for Sage Therapeutics (5/2017) in a one-day advisory board, Ibis Reproductive Health (a non-for-profit research group 2017–present), Hims, Inc. (2019–present) and Folx, Inc. (2020–present). JH is consultant advisor for Plume, Inc. (2020–present). None of these roles present a conflict of interest with this work as described here. All other authors report no conflict of interest.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Per agreements in the informed consent materials with participants, the authors cannot make the data publicly available. However, in support of transparency in research, we can discuss secure ways to make de-identified quantitative (not qualitative) data available on a per-request basis. Interested researchers should contact the corresponding author (hmoseson@ibisreproductivehealth.org).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1. Light A, Wang L-F, Zeymo A, et al. Family planning and contraception use in transgender men. Contraception 2018;98:266–9. 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moseson H, Fix L, Ragosta S, et al. Abortion experiences and preferences of transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2020. 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.09.035. [Epub ahead of print: 25 Sep 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Flores AR, Herman JL, Gates GJ. How many adults identify as transgender in the United States? Los Angeles, CA: The Williams Institute, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meerwijk EL, Sevelius JM. Transgender population size in the United States: a meta-regression of population-based probability samples. Am J Public Health 2017;107:e1–8. 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Beckwith N, Reisner SL, Zaslow S, et al. Factors associated with gender-affirming surgery and age of hormone therapy initiation among transgender adults. Transgend Health 2017;2:156–64. 10.1089/trgh.2017.0028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Batavia JP, Kolon TF. Fertility in disorders of sex development: a review. J Pediatr Urol 2016;12:418–25. 10.1016/j.jpurol.2016.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rowlands S, Amy J-J. Preserving the reproductive potential of transgender and intersex people. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care 2018;23:58–63. 10.1080/13625187.2017.1422240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Reisner SL, Perkovich B, Mimiaga MJ. A mixed methods study of the sexual health needs of New England transmen who have sex with nontransgender men. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2010;24:501–13. 10.1089/apc.2010.0059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bauer GR, Redman N, Bradley K, et al. Sexual health of trans men who are gay, bisexual, or who have sex with men: results from Ontario, Canada. Int J Transgend 2013;14:66–74. 10.1080/15532739.2013.791650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fix L, Durden M, Obedin-Maliver J. Stakeholder perceptions and experiences regarding access to contraception and abortion for transgender, non-binary, and gender-expansive individuals assigned female at birth in the U.S.. Arch Sex Behav 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Moseson H, Zazanis N, Goldberg E, et al. The imperative for transgender and gender nonbinary inclusion: beyond women's health. Obstet Gynecol 2020;135:1059–68. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA, Jones RK, et al. Denial of abortion because of provider gestational age limits in the United States. Am J Public Health 2014;104:1687–94. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jones RK, Upadhyay UD, Weitz TA. At what cost? Payment for abortion care by U.S. women. Womens Health Issues 2013;23:e173–8. 10.1016/j.whi.2013.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Harb CYW, Pass LE, De Soriano IC, et al. Motivators and barriers to accessing sexual health care services for transgender/genderqueer individuals assigned female sex at birth. Transgend Health 2019;4:58–67. 10.1089/trgh.2018.0022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Grossman D, Holt K, Peña M, et al. Self-induction of abortion among women in the United States. Reprod Health Matters 2010;18:136–46. 10.1016/S0968-8080(10)36534-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Moseson H, Bullard KA, Cisternas C, et al. Effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion between 13 and 24 weeks gestation: a retrospective review of case records from accompaniment groups in Argentina, Chile, and Ecuador. Contraception 2020;102:91–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fuentes L, Baum S, Keefe-Oates B, et al. Texas women's decisions and experiences regarding self-managed abortion. BMC Womens Health 2020;20:6. 10.1186/s12905-019-0877-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Moseson H, Herold S, Filippa S, et al. Self-managed abortion: a systematic scoping review. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020;63:87-110. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Foster AM, Arnott G, Hobstetter M. Community-based distribution of misoprostol for early abortion: evaluation of a program along the Thailand-Burma border. Contraception 2017;96:242–7. 10.1016/j.contraception.2017.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Moseson H, Jayaweera R, Raifman S, et al. Self-managed medication abortion outcomes: results from a prospective pilot study. Reprod Health 2020;17:164. 10.1186/s12978-020-01016-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Stillman M, Owolabi O, Fatusi AO, et al. Women's self-reported experiences using misoprostol obtained from drug sellers: a prospective cohort study in Lagos State, Nigeria. BMJ Open 2020;10:e034670. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-034670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Gerdts C, Jayaweera RT, Baum SE, et al. Second-trimester medication abortion outside the clinic setting: an analysis of electronic client records from a safe abortion hotline in Indonesia. BMJ Sex Reprod Health 2018;44:286–91. 10.1136/bmjsrh-2018-200102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Aiken ARA, Digol I, Trussell J, et al. Self reported outcomes and adverse events after medical abortion through online telemedicine: population based study in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland. BMJ 2017;357:j2011. 10.1136/bmj.j2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aiken ARA, Broussard K, Johnson DM, et al. Motivations and experiences of people seeking medication abortion online in the United States. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2018;50:157–63. 10.1363/psrh.12073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jones RK. How commonly do US abortion patients report attempts to self-induce? Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011;204:23.e1–23.e4. 10.1016/j.ajog.2010.08.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moseson H, Filippa S, Baum SE, et al. Reducing underreporting of stigmatized pregnancy outcomes: results from a mixed-methods study of self-managed abortion in Texas using the list-experiment method. BMC Womens Health 2019;19:113. 10.1186/s12905-019-0812-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ralph L, Foster DG, Raifman S, et al. Prevalence of self-managed abortion among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2029245. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lindberg LD, Bell DL, Kantor LM. The sexual and reproductive health of adolescents and young adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 2020;52:75–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moseson H, Fix L, Hastings J, et al. Pregnancy intentions and outcomes among transgender, nonbinary, and gender-expansive people assigned female or intersex at birth in the United States: results from a national, quantitative survey. Int J Transgend Health 2020;133:1–12. 10.1080/26895269.2020.1841058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jones RK, Witwer E, Jerman J. Transgender abortion patients and the provision of transgender-specific care at non-hospital facilities that provide abortions. Contracept X 2020;2:100019. 10.1016/j.conx.2020.100019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lunn MR, Capriotti MR, Flentje A, et al. Using mobile technology to engage sexual and gender minorities in clinical research. PLoS One 2019;14:e0216282. 10.1371/journal.pone.0216282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Moseson H, Lunn MR, Katz A, et al. Development of an affirming and customizable electronic survey of sexual and reproductive health experiences for transgender and gender nonbinary people. PLoS One 2020;15:e0232154. 10.1371/journal.pone.0232154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. World Health Organization (WHO) . Medical management of abortion, 2018. Available: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/278968/9789241550406-eng.pdf?ua=1 [PubMed]

- 34. Dehlendorf C, Harris LH, Weitz TA. Disparities in abortion rates: a public health approach. Am J Public Health 2013;103:1772–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301339 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Obedin-Maliver J. Time for OBGYNs to care for people of all genders. J Womens Health 2015;24:109–11. 10.1089/jwh.2015.1518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Paradiso C, Lally R, Knowledge NP. Attitudes, and beliefs when caring for transgender people. Transgender health 2018;3:47–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. White W, Brenman S, Paradis E, et al. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender patient care: medical students' preparedness and comfort. Teach Learn Med 2015;27:254–63. 10.1080/10401334.2015.1044656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Aiken A, Lohr PA, Lord J, et al. Effectiveness, safety and acceptability of no-test medical abortion provided via telemedicine: a national cohort study. BJOG 2021. 10.1111/1471-0528.16668. [Epub ahead of print: 18 Feb 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Legal L. Intersex 101, 2015. Available: https://www.lambdalegal.org/blog/20151026_intersex-101

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Per agreements in the informed consent materials with participants, the authors cannot make the data publicly available. However, in support of transparency in research, we can discuss secure ways to make de-identified quantitative (not qualitative) data available on a per-request basis. Interested researchers should contact the corresponding author (hmoseson@ibisreproductivehealth.org).