Significance

Populist movements have begun to challenge mainstream political parties, disrupt established norms, and engage in violence against democratic institutions. The movements are fueled by significant support from ordinary citizens who have become increasingly politically polarized. We show that risk-averse attitudes toward other identity groups can transform into affective polarization between supporters of different political parties, through a process of cultural evolution. The economic factors that drive risk aversion can also magnify the effects of unequal wealth, creating a dangerous feedback loop between polarization and inequality. However, redistribution via public goods that reduces inequality can both prevent the onset of political polarization and make it easier for coordinated efforts to reverse entrenched polarized attitudes.

Keywords: inequality, cultural evolution, polarization, risk aversion

Abstract

The form of political polarization where citizens develop strongly negative attitudes toward out-party members and policies has become increasingly prominent across many democracies. Economic hardship and social inequality, as well as intergroup and racial conflict, have been identified as important contributing factors to this phenomenon known as “affective polarization.” Research shows that partisan animosities are exacerbated when these interests and identities become aligned with existing party cleavages. In this paper, we use a model of cultural evolution to study how these forces combine to generate and maintain affective political polarization. We show that economic events can drive both affective polarization and the sorting of group identities along party lines, which, in turn, can magnify the effects of underlying inequality between those groups. But, on a more optimistic note, we show that sufficiently high levels of wealth redistribution through the provision of public goods can counteract this feedback and limit the rise of polarization. We test some of our key theoretical predictions using survey data on intergroup polarization, sorting of racial groups, and affective polarization in the United States over the past 50 y.

The political polarization of citizens is increasingly a concern throughout the world, as populist movements challenge mainstream parties in efforts to disrupt established institutions and democratic norms (1). Such trends have been especially manifest in the United States, where they have culminated in political violence such as at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville and the storming of the Capitol during the certification of the 2020 presidential election (2) (see also ref. 3).

There has been extensive debate about the nature and causes of mass polarization. The earliest work, focused on the distributions of voter policy preferences, cast considerable doubt as to whether mass polarization was an important phenomenon at all. That work continues to show that the public’s attitudes on policy issues have remained stable and centrist over many decades (4) (but see ref. 5; this debate is reviewed in ref. 6).

However, two other important facets of mass polarization have been rising. The first is the process of partisan sorting, where the policy preferences and group identities of a voter better align with their partisan attachments (7–9). The second is affective polarization, whereby individuals develop negative attitudes and behaviors toward members of the opposing party (10, 11).

Sorting and affective polarization appear to be strongly related to increasing intergroup conflict. The growth of intergroup antagonism has been shown to have multiple contributing factors, including economic adversity, racial animus, and a range of other socioeconomic factors (12–19). Recent work focusing on the cultural evolution of polarization along identity group lines (20) has shown that a rise in economic adversity or inequality can cause polarized behavioral strategies to take hold and become entrenched in a population, even when the adverse conditions that stimulated it are reversed (21).

Despite the important link between partisan sorting and intergroup conflict, there have been few analytical efforts to examine the joint dynamics of these processes. So, in this paper, we generalize the framework of Stewart et al. (20) to study the cultural evolution of group polarization and party sorting. In this model, out-group economic interactions are assumed to be more beneficial but more risky than in-group interactions (22–26), and adverse economic environments are assumed to favor risk aversion. We show that, when agents attend to both group and partisan identities in choosing interaction partners, this stimulates both the evolution of behavioral strategies that polarize along party lines and the sorting of group identities along party lines. These behaviors evolve in response to shifts in the economic environment and underlying inequality.

Efforts to mitigate risk aversion in disadvantaged groups via wealth redistribution, in the form of public goods, have the potential to counteract feedback loops that induce polarization. And yet, we show that low levels of redistribution can actually magnify underlying inequality and entrench polarization. But, more optimistically, we also find that sufficiently high levels of redistribution can indeed reduce the impact of inequality and even prevent the emergence of polarization.

Results

To study the cultural evolution of mass political polarization, we generalize a model previously developed to study intergroup polarization and economic interactions (20).

In this model, we assume that a large population of individuals comprises two distinct identity groups. These identities are assumed fixed, and thus correspond to a fixed feature of identity such as race, religious heritage, or socioeconomic background. Although such identities are fixed in the model, the salience of the identity, and therefore its impact on behavior, varies.

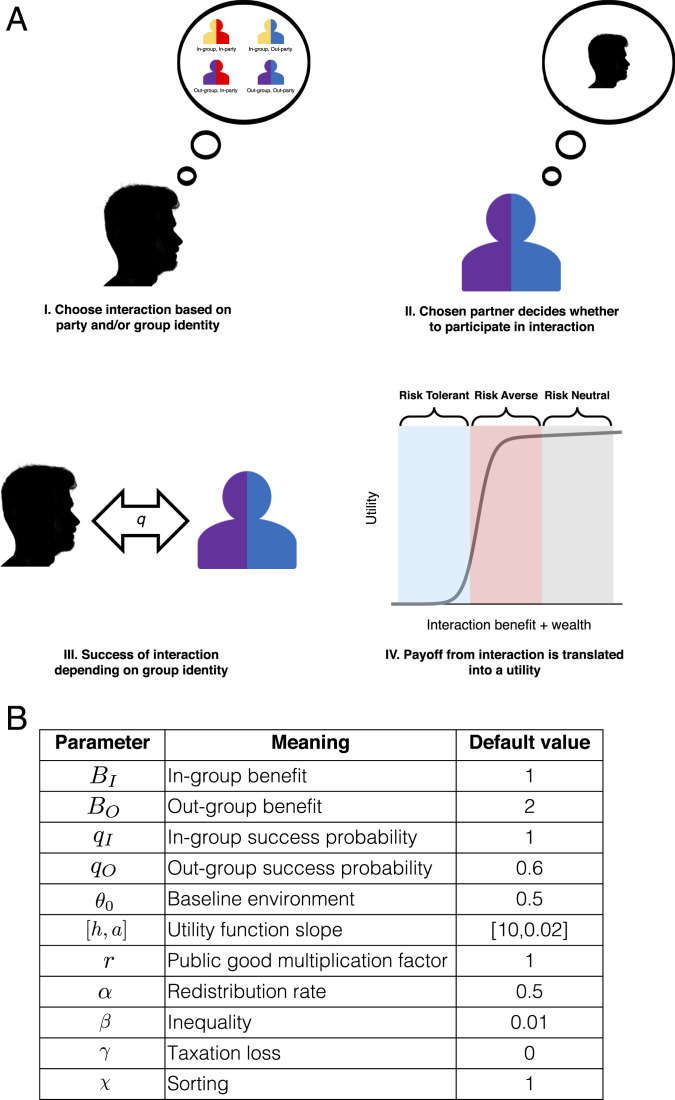

We assume that members of the population choose to interact with one another, using a one-dimensional strategy , that describes the probability of choosing an in-group member for an economic interaction, whereas the probability of choosing an out-group member is (Fig. 1 and Table 1). A large literature documents the prevalence of economic discrimination on the basis of group identities. For a recent review and critique, see ref. 27. That difference in partisan identifications can lead to economic discrimination is consistent with the experimental findings in refs. 28 and 29.

Fig. 1.

Model of social interaction and identity. (A) A focal individual (black) engages in beneficial economic interactions. (I) He first chooses a target for interaction (Table 1). In general, this decision may be based on both party and group identity. (II) The chosen target may then agree to engage or not, based on the identity of the focal individual. (III) If the pair interacts, the interaction is successful with probability if they share the same identity group, or if they belong to different identity groups. (IV) The benefit of a successful interaction is translated into a level of utility that depends on the underlying economic environment (denoted “wealth”) experienced by the focal individual. Depending on that environment, the agent’s utility function may be risk neutral (gray region), risk averse (red region), or risk tolerant (blue region), as described in Eq. 2. (B) The table shows default parameters for our analysis, although we vary these systematically in SI Appendix and show that our results are robust to parameter choice.

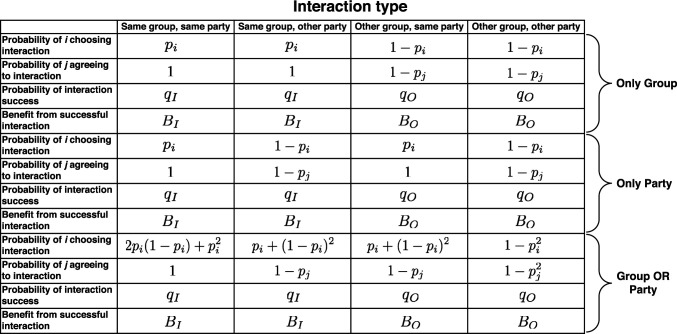

Table 1.

Summary of decision processes

|

We consider three decision processes for a focal individual i choosing an economic interaction. For each decision process, there is a probability of interaction given the identity of a potential target, and a probability of a target j consenting to interaction. If an interaction takes place, the probability of success, and the benefit generated, depend on the identity groups of the pair.

We assume that out-group interactions are more risky than in-group interactions. In particular, an in-group interaction has success probability , while an out-group interaction has success probability . Successful in-group interactions generate benefit , whereas out-group interactions generate benefit , such that the expected benefit of out-group interactions exceeds that of in-group interactions—that is, .

This asymmetry, in which out-group interactions generate greater potential benefits than in-group interactions (), may reflect the benefits of cultural or ideological diversity on the quality of joint enterprise, as seen, for example, in the quality of Wikipedia articles produced by an ideologically diverse team (26). These asymmetries may also be motivated by the expansion of economic gains and opportunities associated with the expansion of markets when groups are willing to trade and work with one another (30).

Finally, we assume that the state of the underlying economic environment, , determines the risk profile experienced by individuals as the benefits of their social interactions are translated into utility. The expected utility for a player is given by

| [1] |

where is the average strategy among out-group members. We have assumed that out-group interactions are only possible if both players are willing to interact with out-group members, whereas in-group interactions are always available (Table 1 and Materials and Methods). The function defines an individual’s utility as a function of material payoff and has the form

| [2] |

Here controls the steepness of the nonlinear sigmoid component of the curve, and controls the gradient of the linear component of the curve. This modified “S”-shaped utility function allows us to capture changes to risk aversion experienced by individuals as a function of the underlying economic environment, . Assuming , the utility function is maximally concave (risk averse) when , and is maximally convex (risk tolerant) when , and it becomes linear (risk neutral) when .

Intuitively, our utility function implies there is risk aversion when the underlying economic environment parameter is small but positive. In this regime, which may be thought of as analogous to a risk profile of an individual close to poverty, failures of economic interactions result in very sharp declines in utility—and so, in-group interactions are preferable to the more risky out-group interactions. But, when the underlying economic environment is very good (), risk aversion declines, and out-group interactions, which have greater expected returns, are preferable. Finally, when the underlying environment is so bad () that a successful economic interaction produces a sharp increase in utility, then risky out-group interactions become strongly preferred.

A version of this model of intergroup interaction has already shown (20) that both high polarization () and low polarization () are stable outcomes when the economic environment is strong; but only high polarization is stable as risk aversion increases. As a result, populations tend to become polarized when the underlying economic environment exogenously declines, and they remain polarized even if the economic environment subsequently improves.

We now generalize the framework to study mass political polarization, in which individuals have a fixed group identity and a sticky, but more malleable, partisan identity. We study how polarization along party lines can emerge as a consequence of risk aversion, as well as the extent to which group identities sort along party lines. We further allow for feedback between individual economic interactions and the overall state of the economic environment. Thus, the environmental dynamic is not exogenous, but rather is coupled to partisan identification and individual decisions about economic interactions. This coupling leads to a runaway process that accelerates the rise of polarization and also exacerbates economic inequality through its impact on intergroup interactions.

Model of Party Identity and Social Decisions.

In order to generalize the model outlined above and to capture the dynamics of mass political polarization, we assume that the population is composed of two identity groups and two political parties. Each individual has both a group identity and a party identity. In general, we assume an individual’s partisan identity can change, while their group identity is fixed. While this is a reasonable assumption for many group identities, others, such as religion and ethnicity, may switch to match one’s partisanship (31, 32). On the flip side, partisanship in the United States has been shown to be quite stable at the individual level, except in exceptional circumstances such as the realignment of White southerners following Civil Rights (33). But we can interpret party switching in our model as driven by generational change. The risks and benefits of economic interactions between individuals vary by group identity, but we assume that they are independent of party identity. We now consider two additional decision processes beyond that described above. In these versions, an individual’s strategy depends on both party and group identity. First, we describe a case in which the decision to interact with another player depends on their party identity alone, and, second, we consider a case in which both group identity and party identity are salient to interaction choices. Importantly, we assume that differences across these models are due to differences in the saliences of group and party identification, not the ability of agents to observe group or party identification. Future work may consider the case where partisanship must be inferred from group identity, or vice versa.

Table 1 summarizes the parameters and interaction probabilities in all three cases. A detailed description of the mathematical model is given in Materials and Methods, and further details of its analysis can be found in SI Appendix.

The key differences between the various decision processes summarized in Table 1 involve different probabilities that a player chooses a particular type of interaction, and different probabilities of that interaction being accepted by the other agent. When group identity alone is salient to choice of interaction partners, then out-group members may reject an interaction. When only party identity is salient, then out-party members may reject an interaction. When both group identity and party identity are salient, either an out-group or an out-party member may reject an interaction.

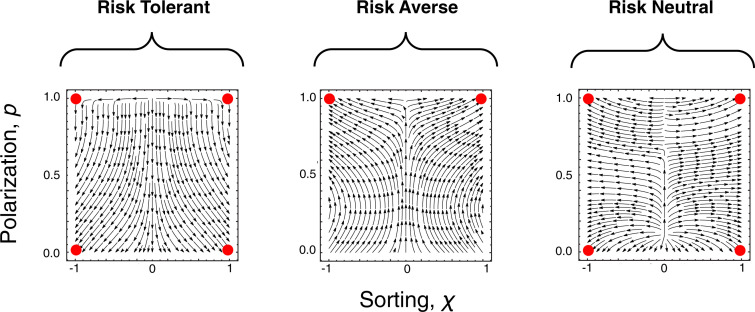

We show that, for all three decision processes, the dynamics of cultural evolution lead to bistability when the underlying economic environment makes individuals risk neutral or risk tolerant, with both a high-polarization and a low-polarization equilibrium as stable outcomes, and that this bistability is robust to the choice of parameters (see SI Appendix). However, if the environment becomes sufficiently risk averse, only the high-polarization equilibrium is stable. Thus a population faced with a sufficiently risk-averse environment moves toward a state of high polarization and remains there, even if the underlying environment subsequently improves and risk aversion declines (20). We explore the consequences of these dynamics for sorting of identity groups along party lines, and in the presence of redistribution via public goods.

Sorting.

In general, political parties and identity groups may be different in size. However, we make the simplifying assumption that both groups and parties are equal in size. If we denote the proportion of group 1 in party 1 as and the proportion of group 2 in party 2 as , the assumption of equal-sized groups and parties and groups means . Under this assumption, we can define the degree of sorting of identity groups along partisan lines via the simple expression

| [3] |

such that corresponds to identity groups distributed equally among the parties, while corresponds to party 1 perfectly aligned with group 1 and corresponds to party 2 perfectly aligned with group 1.

Inequality and Redistribution.

In our model, successful economic interactions not only benefit the pair of interacting individuals but also generate a contribution to a public good that benefits the population at large. To capture this public goods provision, we assume that the current economic environment is a linear function of the benefits generated by successful interactions,

| [4] |

where is the tax rate on wealth, captures the deadweight loss due to taxation, is the benefit multiplication factor of the public good, and is the baseline economic environment when no economic interactions occur. Here denotes the average benefit from economic interactions across the population. The “after tax” payoff received by an individual who generates benefit from economic interactions is thus . This model is motivated by political economic models of linear taxation (34). The consequences of alternative forms of taxation and public goods production offer a natural direction for future work.

Redistribution of public goods is particularly important in the presence of preexisting wealth inequality. A large body of empirical and theoretical work has demonstrated that inequality and polarization correlate and are likely causally linked (35, 36). To capture the effects of preexisting inequality, we assume that one identity group receives benefits from social interactions scaled by a factor while the other group receives . Thus, when , there is no baseline inequality, whereas, when , the wealthier group is around 100 times better off as a result of economic interactions than the poorer group, reflecting, for example, higher-paying jobs or the ability to invest their gains. Alternatively, the wealthier group can be modeled as experiencing a better baseline economic environment, as in ref. 20.

Joint Dynamics of Sorting and Polarized Attitudes.

We first consider the interdependence of sorting and polarization. We keep party size fixed such that a small change in can be thought of as two members of different identity groups and parties swapping parties. We explore this interdependence for both decision processes that account for group and party and those that account for party alone.

We find that, for both types of decision processes, low polarization favors high sorting—so that people change parties until parties are aligned with identity group. This is in contrast to a decision process that takes account only of group identity, where sorting has no effect on utility and therefore does not tend to evolve (see SI Appendix). Under the mixed scenario, in which interaction strategies attend to both group and party identity, high sorting evolves in all environments (Fig. 2). And so the model predicts, in general, that a shift from individuals paying attention to only group identity to individuals also paying attention to party identity will lead to sorting.

Fig. 2.

Polarization and sorting. Phase portraits illustrate the dynamics of polarization and degree of sorting under our model of economic interactions and party switching, with fixed identity groups. Arrows indicate the average selection gradient experienced by a local mutant against a monomorphic background (see Materials and Methods). Red dots indicate stable equilibria. (Left) When the decision process for social interactions considers group or party identity, both high and low polarization states are stable, but sorting is always high . (Center) However, when the environment is risk averse, only high polarization and high sorting are stable. (Right) And finally, when the environment is risk neutral, the system returns to bistable polarization with high sorting. These plots show dynamics for , , , , , and . The phase portraits here show the selection gradient experienced by a monomorphic population in which parties and groups are of equal size. Dynamics under alternate decision processes (Table 1) and different parameter choices are shown in SI Appendix.

For interaction strategies that account only for party identity, however, high polarization favors low sorting (SI Appendix, Fig. S2) when the environment does not induce risk aversion. This arises because, when players focus only on party identity and only interact with their own party, expected payoffs can be maximized by making the parties well mixed with respect to identity group, without any risk of failed interactions due to out-group members refusing to participate in an interaction (Table 1). However, when group identity is visible and salient for interactions, this is not possible.

Identity Group Structure.

We explored the coevolution of sorting and affective polarization as a function of the size and number of identity groups (see Materials and Methods). We find that, when there is pressure to keep parties of equal size, sorting evolves alongside polarization (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). We also explored the impact of group size and structure on the evolution of polarization and sorting (SI Appendix, section 3). We find that, as the number of identity groups increases, the degree of polarization and sorting declines, because interacting exclusively with an in-group becomes increasingly difficult (SI Appendix, Fig. S10). We also find that, when there are two identity groups of different sizes, the larger identity group becomes less sorted than the smaller group (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). Finally, we explored the effect of having one large identity group and multiple smaller identity groups. Under this scenario, we find that sorting and polarization remain high, with one party becoming heterogeneous (i.e., made up of many small identity groups) and the other remaining largely homogeneous (SI Appendix, Fig. S11).

Attention to Party.

So far, we have described the evolution of affective polarization when people pay attention to both group and party identity, and when people pay attention to group identity alone. Next, we considered the effects of varying attention to party identity on the dynamics of sorting and polarization (SI Appendix, section S3). We find that, whereas polarization in response to risk aversion evolves regardless of the degree of attention paid to party identity, sorting increases rapidly with attention to party identity (SI Appendix, Fig. S9), suggesting a feedback loop in which increasingly salient party identities lead to sorting, which further increases the salience of party identity.

Race, Party, and Sorting.

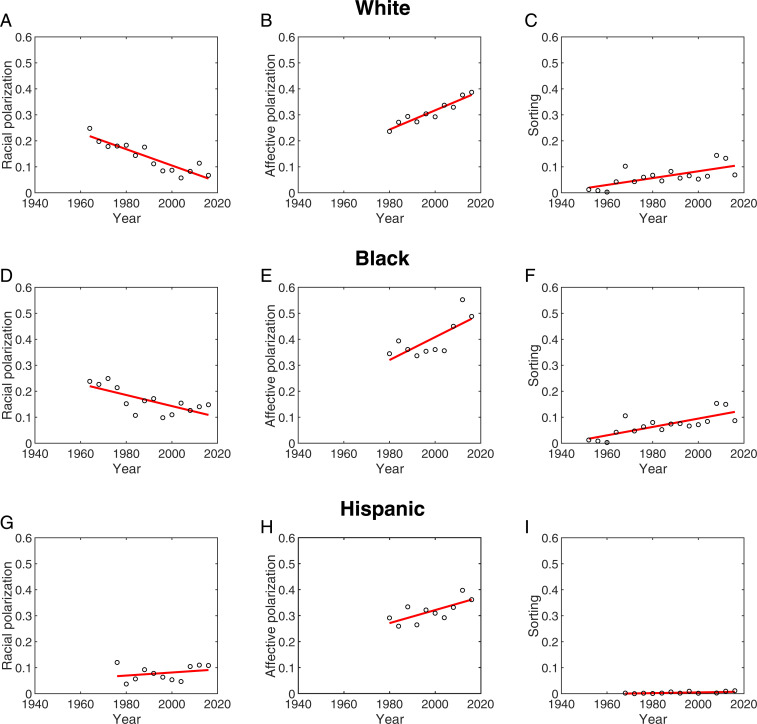

Our model predicts that individuals who take into account both group and party identity when making economic decisions will tend to evolve to a state in which group and party identity align. To examine this theoretical prediction, we looked at the salience of racial identity, party identity, and sorting of people identifying as White, Black, or Hispanic in US presidential elections between 1964 and 2016. Using American National Election Survey (ANES) data, we calculated the affective polarization and in-group favorability toward one’s own racial group versus people from other racial groups, as well as the degree of sorting, measured by the variance in party preference explained by racial identity (Fig. 3 and SI Appendix) (37).

Fig. 3.

Increasing salience of party identity in the United States. We looked at (A, D, and G) in-group favorability and (B, E, and H) affective polarization among White, Black, and Hispanic respondents in ANES data at each presidential election over the past eight decades. While in-group favorability toward racial in-group versus racial out-group declines over time among (A) White () and (D) Black () respondents, there is no significant change among Hispanic respondents (H). Affective polarization increases among (B) White (), (E) Black (), and (H) Hispanic () respondents, indicating a relative decline in the salience of racial identity and an increase in party identity among both the White and the Black groups, and a correspondingly weaker change among the Hispanic group. Sorting of racial groups along party lines has increased among (C) White () and (F) Black () respondents, but shows a much weaker change among (I) Hispanic respondents (). Sorting is measured by the variance in party preference explained by racial identity.

We find that the salience of racial identity (measured by the in-group favorability among respondents) has declined over time among White and Black respondents, and remained stable among Hispanic respondents. At the same time, the salience of party has increased (measured by affective polarization among White respondents) among all groups, with the most significant effect among White and Black respondents. A corresponding increase is also seen in the degree of sorting among White and Black respondents, with Hispanic sorting showing only a slight increase. This suggests a shift in which individuals pay relatively greater attention to party identity over time, and also become more sorted with respect to racial identity. This pattern is consistent the predictions of our model (Fig. 2)—namely, that, as attention is increasingly paid to party, this will induce sorting of group identities along party lines.

Redistribution, Inequality, and Polarization.

According to our model, increased polarization arises as a result of risk aversion in a poor economic environment. In general, however, different identity groups may experience different economic environments. In particular, when there is inequality such that some groups possess less wealth than others, they are more likely to be risk averse and thus become polarized. Such inequality can lead to the evolution of polarization in the whole population (20). However, redistribution via public goods can reduce inequality, and might improve the overall economic environment.

We use Monte Carlo simulations to explore the impact of such redistribution on the dynamics of mass polarization in the presence of inequality. In particular, we focus on situations in which the range of (Eq. 4) encompasses different economic environments, ranging from risk neutral through risk averse and risk tolerant.

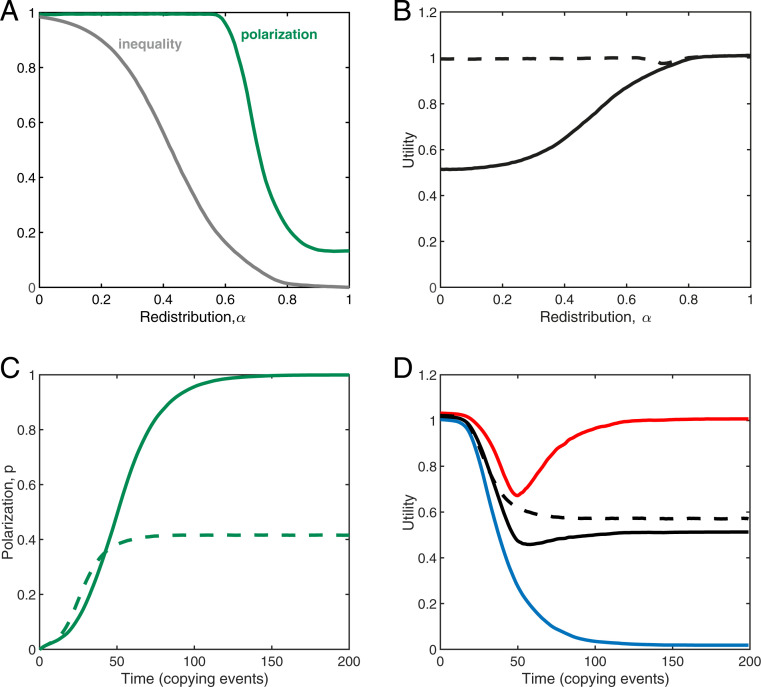

Fig. 4 shows the effect of redistribution and inequality on the dynamics of polarization. We see that sufficient redistribution can reduce both inequality and polarization, although a high degree of redistribution is required to prevent polarization. This effect holds when public goods are purely redistributive ( in Eq. 4), and when public goods increase the overall wealth of the population () (SI Appendix, Fig. S13). When taxation produces a deadweight loss (; Eq. 4), it becomes harder to reduce polarization via redistribution (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

Fig. 4.

Redistribution and inequality. (A and B) Ensemble mean equilibria and (C and D) time trajectories for a population initialized in a low-polarization state, from individual-based simulations in the presence of wealth redistribution (Eq. 4). We show results in the case of no underlying economic inequality, (dashed lines), as well the case of high underlying inequality, (solid lines). Results shown here arise from a decision process that attends to group or party identity, and sorting is fixed exogenously at . (A) When public goods are not multiplicative ( and ), and redistribution is absent (), overall inequality (gray line, measured as the relative difference in utility; see SI Appendix) and polarization (green line) are high. With increasing rates of redistribution, first, overall inequality and, then, polarization decline to zero. (B) Increasing redistribution increases overall utility toward the level achieved when underlying inequality is absent. (C) When public goods increase overall utility ( and ), redistribution (here ) can act to magnify both polarization and inequality over time, compared to a fixed environment without feedback via redistribution. (D) Overall inequality initially has a relatively small impact on population mean utility in a population initialized in a low-polarization state (black lines), but redistribution is seen to magnify the effects of underlying inequality, with the richer group (red line) experiencing a transient decline in utility as polarization evolves before returning to a value close to maximum, while the poorer group (blue line) suffers an irreversible decline toward utility close to zero. Plots show ensemble mean values across replicate simulations, for groups of 1,000 individuals each. Success probabilities and benefits are fixed at , , , with and , while . Evolution occurs via the copying process (see Materials and Methods) with selection strength , mutation rate , and mutation size .

Although sufficient redistribution can reduce inequality and polarization, it is also important to note that the effect of feedback between individual economic interactions and the overall economic environment that arises as a result of redistribution can facilitate the evolution of polarization compared to a high-quality stable environment (i.e., fixed ; Fig. 4C) in which polarization does not evolve. Thus, introducing feedback between individual interactions and the environment through low or intermediate levels of redistribution can make things worse, by both failing to reduce inequality and facilitating the evolution of polarization (Fig. 4 C and D).

We exogenously varied the amount of sorting, . Sorting tends to increase polarization, but it can have complex effects on levels of inequality and population average utility. This is because intermediate levels of polarization tend to result in lower levels of utility. Where reducing sorting can also reduce polarization to low levels, it has a beneficial effect in reducing inequality and increasing population average utility (see SI Appendix).

Inequality Reduces Average Utility.

We also explored the impact of inequality on population average utility. In general, underlying inequality resulting from lower income from economic interactions tends to reduce the population average utility compared to the case where average income remains the same but there is no inequality (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Figs. S12 and S13). This is because the poorer group tends to experience the risk-averse environment in which failed interactions produce a sharp decline in utility.

Recovery from Polarization.

For a wide range of parameter values, the system is bistable, with both high- and low-polarization equilibria maintained unless the environment is risk averse (see SI Appendix). Until this point, we have focused on the conditions under which a population will evolve from a low- to a high-polarization state—that is, the conditions under which the low-polarization equilibrium is lost. However, recovering low polarization once high polarization has evolved requires a switch from one equilibrium to another. In practice, this may occur as the result of an environmental shock (see SI Appendix) or as a result of coordinated action in which a sufficient number of individuals simultaneously adopt a low-polarization strategy to move the population to a state that is then attracted to a low-polarization equilibrium. The threshold frequency of individuals required to achieve this transition is determined by the size of basin of attraction for the high-polarization equilibrium.

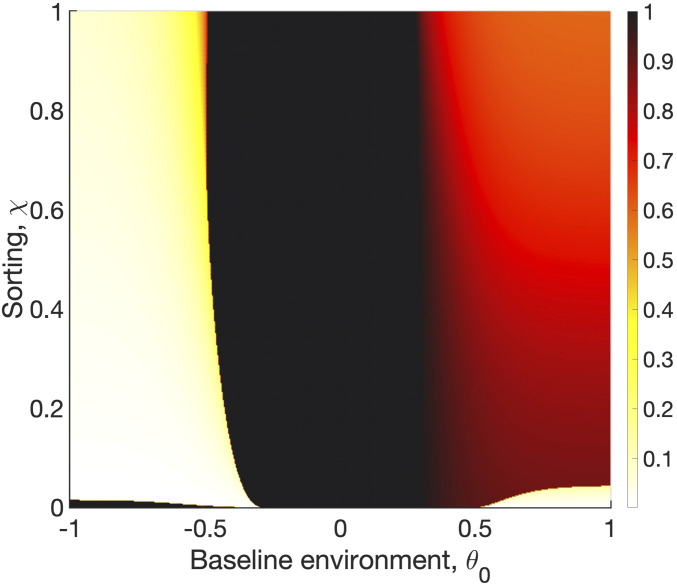

We calculated the frequency required for escape—the proportion of the population that must simultaneously adopt a low-polarization behavior to escape the high-polarization equilibrium (Fig. 5) as a function of the baseline economic environment () and the degree of sorting (). We find that, for many environments, escape is easiest following an economic shock (i.e., a poor environment) in which the population becomes risk tolerant. However, we also find that, once the economic environment is sufficiently advantageous, such that risk aversion is lessened, escape from polarization is feasible, especially if the degree of sorting is also low. Thus, addressing polarization, absent an economic catastrophe, requires first improving the economic environment, minimizing sorting, and then engaging in sufficient coordinated action for a subset of the population to adopt low-polarization behavior, followed by the spread of low-polarization behavior by social contagion.

Fig. 5.

Recovering from polarization. We numerically calculated the size of the basin of attraction for the high-polarization state, which determines the escape frequency—that is, the proportion of the population that must simultaneously adopt a low-polarization behavior to escape the high-polarization equilibrium. We show the escape frequency as a function of the baseline environment, , and the (fixed) degree of sorting, . For intermediate values of theta, risk aversion means that it becomes increasingly difficult to reverse polarization (higher escape frequency, darker colors). However, when the environment is very bad, and risk tolerance dominates, or if the environment is very good, it becomes possible to reverse polarization through the coordinated behavior of small frequency of low-polarization individuals. When the environment is good and sorting is low, polarization is easiest to reverse without entering a highly deleterious environment. Other parameters are set to , , , with and , while , , , and unless otherwise stated.

Discussion

Our model provides a framework for connecting the effects of intergroup animus, economic adversity, and mass political polarization through the lens of cultural evolution (38, 39). We focus on polarization expressed through loss of positive social interactions with members of an out-party (10, 11), and sorting of identity groups along party lines (7–9). We show that attending to party identity when deciding who to interact with is sufficient to translate intergroup polarization stimulated by adverse economic conditions into political polarization between members of opposing parties (Fig. 2). We further show that, if party identity is able to evolve alongside behavioral strategies, this can also lead to sorting of identity groups along party lines (Fig. 3). We then show that feedback between individuals’ economic interactions and the overall economic environment can lead to increased polarization and amplify the effects of underlying inequality between groups (Fig. 4). These effects are magnified when identity groups are sorted along party lines, but can be mitigated or prevented entirely if redistribution of wealth via public goods is put in place to combat inequality (Figs. 4 and 5).

In performing simulations on redistribution (Fig. 4), we used fixed levels of sorting, on the basis that changes to party identity can be assumed slow compared to changes in interaction strategy. However, if the evolution of sorting occurs rapidly, situations may arise in which members of different parties experience divergent selection pressures, raising the possibility that different levels of polarization may arise in some subsets of the population and not others. We find (SI Appendix, Fig. S11) that, when a population is made up of one large and many small identity groups, the dynamics of sorting tend to make the large group form one homogeneous party, and the smaller groups bands together to form a more diverse party, with both parties exhibiting high levels polarization—a situation reminiscent of the major US political parties today. Exploring how effects such as these interact with inequality is a natural direction for future work.

In our model, we specify a mechanism, based on pairwise economic interactions, such as trade, employment decisions, and social cooperation, that leads to the risk aversion that drives polarization. The risk aversion we describe depends on the rapid decline in utility (Eq. 2), which may reflect either perceived or actual loss of income. Although one might expect, on the basis of our model, that richer groups should be less polarized and more heterogeneous in their interactions, we find here (SI Appendix, Fig. S12) and in previous work (20) that polarization rapidly spreads to the whole population, including to risk-tolerant individuals, once it takes hold among a risk-averse subset.

Empirical trends of racial and affective polarization and sorting are consistent with our model (Fig. 3), but the drivers of increased party salience are complex. We find (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) that an increase in the salience of party identity can be beneficial under some circumstances; however, it is important to note that such changes are likely driven by other factors, as well. For example, social desirability bias can lead to reduced racial polarization (40) while allowing interparty animus to remain high. In addition, there is evidence (41) that increased affective polarization is partly driven by exogenous factors such as media environment and lack of contact opportunity with out-group members resulting in induced homophily (42). The interaction between such structural forces and the dynamics of cultural evolution described is an important topic for future research.

Our work focuses on affective polarization and sorting with respect to identity groups among the electorate. However, attempts to prevent and reverse polarization must also take account of the mechanisms that enable elite (43, 44) and ideological polarization (44, 45), and must account for the role of factors such as geography (46) and population and social network structure (47–49) in producing mass polarization, in addition to the intergroup and economic factors studied here. We must also remain alert to the circumstances under which polarization can provide benefits (50, 51) (e.g., SI Appendix, Fig. S12 in which increased sorting can increase polarization but reduce inequality).

The impact of underlying inequality on the evolution of polarization, and the amplification of the effects of inequality via economic feedback, illustrate the need to think carefully about mass political polarization in the context of intergroup conflict and the economic environment (2, 35). This is particularly true when assessing ways to prevent or reverse mass polarization. The success of redistribution in stemming the tide of polarization in our model is striking, and it suggests a possible path for preventing such attitudes from taking hold in the future. We emphasize, though, that this strategy is only possible if implemented in a population that is not already polarized, in an environment that supports low polarization. Once polarization sets in, it typically remains stable under individual-level evolutionary dynamics, even when the economic environment improves or inequality is reversed. The only remedy for reversing a polarized state, under our analysis, requires either a shock (SI Appendix, Fig. S14) or a sufficiently good economic environment coupled with collective action by a portion of the population who change strategies simultaneously.

Materials and Methods

In this section, we describe the decision process, the calculation of utility and selection gradient, and the copying process used in simulations. Further analysis of the model can be found in SI Appendix.

Measure of Inequality.

Throughout, we adopt a simple measure of inequality: the difference in relative utility between the two groups that is, , where is the average utility of the richer group and is the utility of the poorer group.

Decision Process.

Table 1 gives the probability for a focal player choosing to interact with a given player based on the identity of and the decision process adopted by . In order to calculate the utility of given a decision process, we must calculate the probability distribution for the next interaction participates in, conditional on an interaction occurring. That is, we must weight the probability of interactions given in Table 1 by the number of individuals in each group, and normalize the distribution. This corresponds to a process in which the focal player randomly draws an individual from the population and then decides to pursue an interaction with that individual based on the probabilities given in Table 1. These normalized distributions are given below for the decision process that takes account of only party identity, and for the decision process that takes account of group or party identity. Note that, if the decision process takes account of group identity only, no normalization is required, since the degree of sorting does not impact the probability of interaction.

Only Party Identity.

Under this decision process, the probability of an individual belonging to group 1 and party 1 choosing to interact with an individual with identity is , where indexes the group identity or and indexes the party identity, and is the frequency of individuals from group 1 in party 1 (and, by symmetry, the number of individuals from group 2 in party 2). We then have

| [5] |

where is the proportion of identity group that also belong to party .

Party or Group Identity.

Under this decision process, the probability of an individual who belongs to group 1 and party 1 choosing to interact with an individual with identity is . We then have

| [6] |

This decision strategy reflects a situation in which an individual sees someone as a member of their in-group if they share either the same group or the same party identity, and weights both of those dimensions of identity equally. We explore an “and”-type decision process in SI Appendix.

Expected Utility.

In order to explore the evolutionary dynamics of polarization, we calculate the expected utility of a mutant strategy , which deviates by a small amount from the resident strategy employed by the rest of the population. Using Eqs. 5 and 6 above, we can now write down the expected fitness for such a mutant under a given decision process. When players only attend to party identity, the utility of such a mutant is

| [7] |

whereas the utility of a mutant when players attend to party or group is

| [8] |

Selection Gradient.

We can now calculate the average selection gradient (52, 53) experienced by the mutant , which is given by

| [9] |

When the selection gradient is positive, the mutant has an advantage over the resident strategy, on average. Note, however, that, when , different individuals experience different effects from the same mutation. This issue is discussed in more detail in SI Appendix. We can also calculate the effect of a small change to the degree of sorting in the population by calculating the gradient

| [10] |

When is positive, the average effect of an increase in sorting is to increase the average utility of the population. It is Eqs. 5–10 that are used to produce Figs. 2 and 3 (see also SI Appendix).

Evolutionary Simulations.

In order to simulate the evolutionary dynamics of this system, we consider a population evolving under a “copying process” (54) in which individuals are able to observe the utility of other individuals and compare it to their own. The dynamics of the model are as follows: An individual is chosen at random from a population of fixed size . A second individual is then chosen at random for her to “observe.” If has utility and has utility , then chooses to copy the strategy of with probability , where scales the “strength of selection” of the evolutionary process. Note that, if , the probability of copying the behavior of is close to one, whereas, if , the probability is close to zero. Individual-based simulations used to produce Figs. 4 and 5 were performed under the copying process using populations composed of two identity groups of size individuals, with sorting of groups among parties fixed. Mean trajectories were determined from an ensemble of sample paths. Simulations were run for copying events to find equilibria. Mutations were assumed to occur at a rate per copying event, with the target of the mutation chosen randomly from the population. Mutations were assumed to be local such that the target of the mutation had its strategy perturbed by , with mutations that increase and decrease equally likely, and we impose the appropriate boundary conditions to ensure that strategies were physical.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank participants of the PNAS Conference on the Dynamics of Political Polarization, held (virtually) in January 2021, and especially Stuart Feldman for feedback and suggestions for research. We also thank Joanna Bryson for helpful feedback and discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2102140118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

Previously published data were used for this work (https://electionstudies.org).

References

- 1.Mudde C., Kaltwasser C. R., Populism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ahler D. J., The group theory of parties: Identity politics, party stereotypes, and polarization in the 21st century. Forum 16, 3–22 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mason L., Kalmoe N. P., What you need to know about how many Americans condone political violence — and why. The Washington Post, 11 January 2021. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2021/01/11/what-you-need-know-about-how-many-americans-condone-political-violence-why/. Accessed 13 August 2021.

- 4.Fiorina M. P., Abrams S. J., Pope J. C., Culture War? The Myth of a Polarized America (Pearson Longman, New York, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abramowitz A., The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy (Yale University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty N., Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, New York, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Levendusky M. S., The Partisan Sort: How Liberals Became Democrats and Conservatives Became Republican (University of Chicago Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mason L., ‘I disrespectfully agree’: The differential effects of partisan sorting on social and issue polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 128–145 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mason L., Wronski J., One tribe to bind them all: How our social group attachments strengthen partisanship. Polit. Psychol. 39, 257–277 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyengar S., Sood G., Lelkes Y., Affect, not ideology: A social identity perspective on polarization. Public Opin. Q. 76, 405–431 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mason L., A cross-cutting calm: How social sorting drives affective polarization. Public Opin. Q. 80, 351–377 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schaffner B. F., MacWilliams M., Nteta T., Understanding white polarization in the 2016 vote for president: The sobering role of racism and sexism. Polit. Sci. Q. 133, 9–34 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luttig M. D., Federico C. M., Lavine H., Supporters and opponents of Donald Trump respond differently to racial cues: An experimental analysis. Research Politics 4, 10.1177/2053168017737411 (2017). [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sides J., Tesler M., Vavreck L., The 2016 US election: How Trump lost and won. J. Democracy 28, 34–44 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Inglehart R., Norris P., Trump, Brexit, and the rise of populism: Economic havenots and cultural backlash. SSRN [Preprint] (2016). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2818659 (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- 16.Tesler M., In a Trump-Clinton match-up, racial prejudice makes a striking difference. The Washington Post, 25 May 2016. https://washingtonpost.com/news/monkey-cage/wp/2016/05/25/in-a-trump-clinton-match-up-theres-a-striking-effect-of-racial-prejudice/. Accessed 13 August 2021.

- 17.Arnorsson A., Zoega G., On the causes of Brexit. SSRN [Preprint] (2016). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2851396 (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- 18.Kolko J., Trump was stronger where the economy is weaker. Five Thirty Eight (2016). https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/trump-was-stronger-where-the-economyis-weaker/. Accessed 13 August 2021.

- 19.Mitrea E. C., Mühlböck M., Warmuth J., Extreme pessimists? Expected socioeconomic downward mobility and the political attitudes of young adults. Polit. Behav. 43, 785–811 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart A. J., McCarty N., Bryson J. J., Polarization under rising inequality and economic decline. Sci. Adv. 6, eabd4201 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macy M. W., Ma M., Tabin D. R., Gao J., Szymanski B. K., Polarization and tipping points. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102144118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruef M., Strong ties, weak ties and islands: Structural and cultural predictors of organizational innovation. Ind. Corp. Change 11, 427–449 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Woolley A. W., Chabris C. F., Pentland A., Hashmi N., Malone T. W., Evidence for a collective intelligence factor in the performance of human groups. Science 330, 686–688 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martinez M. A., Aldrich H. E., Networking strategies for entrepreneurs: Balancing cohesion and diversity. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 17, 7–38 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carruthers P., Smith P. K., Eds., Theories of Theories of Mind (Cambridge University Press, 1996). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shi F., Teplitskiy M., Duede E., Evans J. A., The wisdom of polarized crowds. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3, 329–336 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Charles K. K., Guryan J., Studying discrimination: Fundamental challenges and recent progress. Annu. Rev. Econ. 3, 479–511 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConnell C., Margalit Y., Malhotra N., Levendusky M., The economic consequences of partisanship in a polarized era. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 62, 5–18 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iyengar S., Westwood S. J., Fear and loathing across party lines: New evidence on group polarization. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 690–707 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Becker G. S., The Economics of Discrimination (University of Chicago Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egan P. J., Identity as dependent variable: How Americans shift their identities to align with their politics. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 64, 699–716 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margolis M. F., How politics affects religion: Partisanship, socialization, and religiosity in America. J. Polit. 80, 30–43 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Green D., Palmquist B., Schickler E., Partisan Hearts and Minds (Yale University Press, 2008). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Meltzer A. H., Richard S. F., A rational theory of the size of government. J. Polit. Econ. 89, 914–927 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCarty N. M., Poole K. T., Rosenthal H., Polarized America: The Dance of Ideology and Unequal Riches (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, ed. 2, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voorheis J., McCarty N., Shor B., Unequal incomes, ideology and gridlock: How rising inequality increases political polarization. SSRN [Preprint] (2015). https://ssrn.com/abstract=2649215 (Accessed 20 August 2021).

- 37.Stanford University; University of Michigan; The American National Election Studies. Time series cumulative data file (1948-2016) . https://electionstudies.org/data-center. Accessed 13 August 2021.

- 38.Boyd R., Richerson P. J., Culture and the Evolutionary Process (University of Chicago Press, 1985). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cavalli-Sforza L. L., Feldman M. W., Cultural Transmission and Evolution: A Quantitative Approach (Princeton University Press, 1981). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Khalid A., How white liberals became woke, radically changing their outlook on race. National Public Radio, 1 October 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/10/01/763383478/how-white-liberals-became-woke-radically-changing-their-outlook-on-race. Accessed 13 August 2021.

- 41.Iyengar S., Lelkes Y., Levendusky M., Malhotra N., Westwood S. J., The origins and consequences of affective polarization in the United States. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 22, 129–146 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kossinets G., Watts D., Origins of homophily in an evolving social network. Am. J. Sociol. 115, 405–450 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flamino J., et al. , Shifting polarization and Twitter news influencers between two U.S. presidential elections. arXiv [Preprint] (2021). https://arxiv.org/pdf/2111.02505.pdf (Accessed 24 November 2021).

- 44.Leonard N. E., Lipsitz K., Bizyaeva A., Franci A., Lelkes Y., The nonlinear feedback dynamics of asymmetric political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102149118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Axelrod R., Daymude J. J., Forrest S., Preventing extreme polarization of political attitudes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102139118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chu O. J., Donges J. F., Robertson G. B., Pop-Eleches G., The micro-dynamics of spatial polarization: A model and an application to survey data from Ukraine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2104194118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stewart A. J., et al. , Information gerrymandering and undemocratic decisions. Nature 573, 117–121 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Santos F. P., Lelkes Y., Levin S. A., Link recommendation algorithms and dynamics of polarization in online social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102141118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tokita C. K., Guess A. M., Tarnita C. E., Polarized information ecosystems can reorganize social networks via information cascades. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102147118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kawakatsu M., Lelkes Y., Levin S. A., Tarnita C. E., Interindividual cooperation mediated by partisanship complicates Madison's cure for “mischiefs of faction.” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102148118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vasconcelos V. V., et al. , Segregation and clustering of preferences erode socially beneficial coordination. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102153118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mullon C., Keller L., Lehmann L., Evolutionary stability of jointly evolving traits in subdivided populations. Am. Nat. 188, 175–195 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Leimar O., Multidimensional convergence stability. Evol. Ecol. Res. 11, 191–208 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Traulsen A., Nowak M. A., Pacheco J. M., Stochastic dynamics of invasion and fixation. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 74, 011909 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Previously published data were used for this work (https://electionstudies.org).