Significance

Political polarization threatens democracy in America. This article helps illuminate what drives it, as well as what factors account for its asymmetric nature. In particular, we focus on positive feedback among members of Congress as the key mechanism of polarization. We show how public opinion, which responds to the laws legislators make, in turn drives the feedback dynamics of political elites. Specifically, we find that voters’ “policy mood,” i.e., whether public opinion leans in a more liberal or conservative direction, drives asymmetries in elite polarization over time. Our model also demonstrates that once self-reinforcing processes among elites reach a critical threshold, polarization rapidly accelerates. By tying together elite and voter dynamics, this paper presents a unified theory of political polarization.

Keywords: political polarization, nonlinear dynamics, political elites, public opinion, bifurcations

Abstract

Using a general model of opinion dynamics, we conduct a systematic investigation of key mechanisms driving elite polarization in the United States. We demonstrate that the self-reinforcing nature of elite-level processes can explain this polarization, with voter preferences accounting for its asymmetric nature. Our analysis suggests that subtle differences in the frequency and amplitude with which public opinion shifts left and right over time may have a differential effect on the self-reinforcing processes of elites, causing Republicans to polarize more quickly than Democrats. We find that as self-reinforcement approaches a critical threshold, polarization speeds up. Republicans appear to have crossed that threshold while Democrats are currently approaching it.

American policymakers are more polarized today than any time since the end of the Civil War. After a period of bipartisanship following World War II, Republican and Democratic political elites, typically defined as legislators and other elected officials, diverged dramatically. The resulting polarization threatens the long-term stability of America and “has triggered the epidemic of norm breaking that now challenges our democracy” (ref. 1, p. 204).

Despite clear evidence of its existence, explanations for polarization, such as changes to the media environment, interest group influence, and institutional factors, are often presented in a piecemeal fashion. We offer a unified model of mass and elite polarization that subsumes many of these explanations. In particular, we focus on two elite-level positive feedback mechanisms underpinning polarization: party self-reinforcement and reflexive partisanship. Party self-reinforcement involves sources of elite polarization being driven themselves by the polarization they create. Elites engage in reflexive partisanship when they support policies simply because the other side opposes them (2). We show that the former is more consistent with historical trends in elite polarization than the latter. In addition, we demonstrate that thermostatic input from voters drives temporal and asymmetric aspects of these polarization dynamics. Doing so demonstrates that elite polarization is not, in fact, “disconnected” from public opinion (3).

We use our model as a testbed to examine processes co-occurring in a two-party democratic system between elites, as well as between elites and citizens, and to explore the temporal aspects of these processes. The model is parsimonious, and thus analytically tractable, allowing us to focus in a principled way on the essential mechanisms that drive the complex process of polarization. We use the model to systematically test and compare hypotheses and rule out those hypotheses that yield temporal dynamics that are inconsistent with historical data.

Subsequently, we offer several contributions to the polarization literature. First, we find that, among the possible explanations examined here, polarization can be best explained by a positive feedback mechanism, which, by definition, yields a pattern of increasing returns (4). Positive feedback amplifies variations in ideological position while negative feedback attenuates variations in ideological position. As positive feedback grows, it can reach a critical threshold at which point amplifying and attenuating effects are balanced. When positive feedback, in the form of party self-reinforcement or reflexive partisanship, crosses that threshold, then ideological positions can rapidly become extreme. Second, we find that elite-level self-reinforcement can explain polarization in the United States. The asymmetry in the polarization comes from asymmetry in self-reinforcement driven by the dynamics of policy mood—an aggregate measure of the public’s ideology—wherein voters shift more frequently and for a longer duration to the right than to the left. Third, we rule out reflexive partisanship as a dominant mechanism since it does not explain asymmetric polarization even when driven by policy mood. The fact that reflexive partisanship is a mutual response undermines its asymmetric effect. Relatedly, we also demonstrate that the breakdown in norms of bipartisanship, i.e., the inverse of reflexive partisanship, cannot account for the rise of asymmetric polarization. Fourth, we rule out the (null) hypothesis that elites are merely responding to policy mood without a positive feedback mechanism.

Asymmetric Polarization

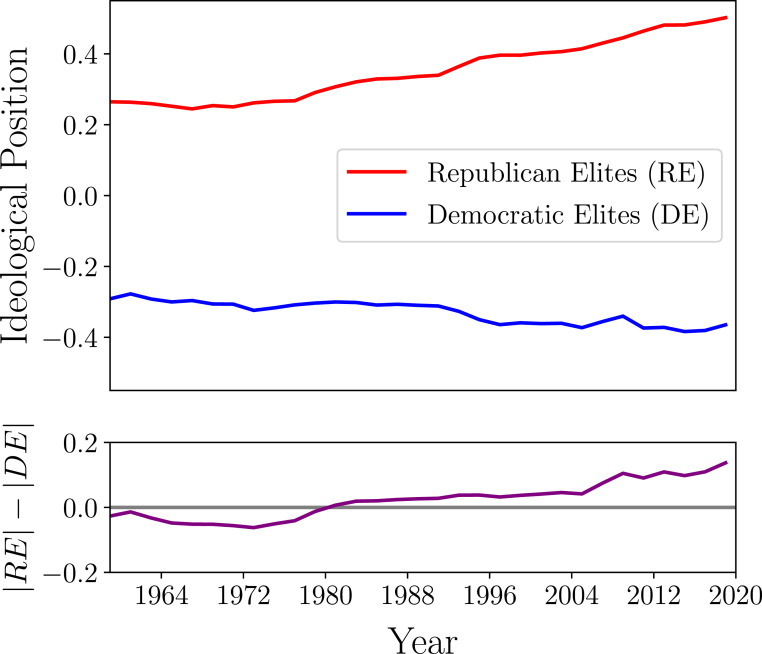

Any model of elite polarization must offer insight into one of its more notable characteristics: its asymmetry. While elites of both parties have polarized ideologically, Fig. 1 uses dynamic, weighted, nominal three-step estimation (DW-NOMINATE) scores to illustrate that this process has been more precipitous for Republicans in the US Congress, yielding a position that is currently more extreme than the Democratic Party’s (5–8). DW-NOMINATE uses roll-call votes to position legislators, based on how often they vote with or against one another, in a latent space that is most often referred to as ideology.* Most explanations for this asymmetry focus on processes occurring at the elite level both inside and outside of Congress. In Congress, researchers point to the emergence of successful conservative factions (12), as well as a particularly aggressive governing style among party leaders who use party discipline to harness members to their more extreme agendas (8).

Fig. 1.

DW-NOMINATE scores (first dimension) averaged across US Senate and House of Representatives.

Others point to elite-level factors occurring outside of Congress. Intellectuals or “coalition merchants” on both the right and the left began to craft distinct conservative and liberal ideologies in the 1930s (13), but the project of those on the right was more ambitious and successful in creating ideological homogeneity among interest groups, media outlets, and think tanks that both fueled and reinforced the rightward movement of the Republican Party (7). More recently, individuals and organizations with ties to the conservative movement, such as the Koch brothers and Americans for Prosperity, have used campaign funding as a means of keeping GOP members in line (14). While Democrats have no shortage of wealthy backers, their heterogeneous policy commitments may have offered some resistance to the ideological pressure exerted by donors. Such cross-cutting pressures are largely absent for business-friendly Republicans (5).

Scholars have considered the possibility that citizens might be at least partially responsible for the asymmetric nature of elite polarization, but have largely dismissed the notion because it is not clear that Americans themselves are polarized (15, 16). Republican voters do appear to be more loyal to conservative doctrine, however, and less tolerant of compromise than Democratic voters (17).

Despite the insights these explanations offer, they are unsatisfactory for a variety of reasons. Some elite-focused explanations, such as the rise of conservative media and donor networks on the right, identify processes that began too recently to explain asymmetric polarization that began much earlier, although they almost certainly exacerbated the trend. Citizen-focused explanations, on the other hand, tend to be far too preoccupied with Republican voters and ignore almost two-thirds of the electorate, including independents and Democrats. Finally, most of these accounts do not recognize how processes occurring at the elite and citizen level are interconnected.

Self-Reinforcement, Reflexive Partisanship, and Additive Response Among Elites

Our model explains polarization through an interplay of positive feedback and negative feedback. Changes in the balance between positive and negative feedback are driven by citizen political preferences as represented by policy mood. We consider two fundamental positive feedback mechanisms that have been proposed in the literature to explain elite polarization: party self-reinforcement (hypothesis A) and reflexive partisanship (hypothesis B). We also consider the null hypothesis in which elites respond additively to citizens with no positive feedback mechanism (hypothesis C).

Self-Reinforcement.

Many polarizing processes exhibit positive feedback in the form of “a powerful self-reinforcing logic” (ref. 5, p. 45). For example, Pierson and Schickler (5) argue that as the parties polarize, interest groups have an incentive to join one of the parties’ coalitions. Once they do, their goal becomes to help it win at any cost. This can involve punishing defectors and eliminating moderating voices. This same logic, however, applies to any group of actors involved in the polarization process. For example, extremist party leaders can punish moderate members by backing their more extreme opponents in primaries. They can also employ party discipline to keep such members in line. Elite polarization may also trigger anger and distrust of the other side among voters, who, in turn, may elect more extreme representatives (18). When they do, it has the potential to exacerbate self-reinforcing elite polarizing processes.

Reflexive Partisanship.

Political elites may also be engaging in mutual polarization or reflexive partisanship (2), wherein one party will oppose a policy merely because the other side supports it. Policymakers often find it politically useful to “exploit and deepen division rather than seeking common ground” (ref. 2, p. 193). This may yield a cycle wherein one party becomes more extreme as a response to the other party’s increasing extremity.

Additive Response.

We also examine the possibility that political elites respond to voter preferences without any positive feedback mechanism. That is, we consider that elites may be adjusting their ideological positions through an additive response to changing signals from voters but independently of how moderate or extreme are their own and the other party’s positions.

Voter Policy Mood as Input to Elite Polarization

According to thermostatic models of public opinion, the relationship between policymaking and public opinion is dynamic (19). Citizens respond to policy outputs, and when these outputs are more liberal/conservative than their preferences, they communicate their desire for more conservative/liberal policies through surveys, through activism, and by voting out incumbents. Parties either adapt to these signals by revising their platforms, supporting different candidates, and voting for policies the public wants or they continue to lose elections (19, 20). A widely used measure of public opinion is referred to as the “policy mood,” which captures where aggregate public opinion falls along a liberal–conservative dimension (21). We hypothesize that asymmetries in the thermostatic dynamics of public opinion may explain the unbalanced trends we see in Fig. 1; if conservative swings in policy mood are more substantial, numerous, or prolonged than liberal swings, they will amplify the responsive dynamics of Republican elites more substantially than those of Democratic elites.

By feeding policy mood data into a model of elite opinion dynamics, we demonstrate that such asymmetries can indeed account for the polarization trends we see in historical data if political elites are assumed to respond through a self-reinforcing positive feedback (hypothesis A [hyp. A]). This suggests citizens do not have to be polarized themselves to contribute to elite polarization; they can contribute simply by amplifying the self-reinforcement dynamics of one of the parties.

Reflexive partisanship (hyp. B) can also explain polarization, but we show that it does not do as well as party self-reinforcement in capturing the trends in historical data; most notably, it falls short in explaining the asymmetry in polarization. We further demonstrate that polarization is not well explained if it is assumed that political elites respond to policy mood but not through a positive feedback (hyp. C). This is to be expected since this hypothesis fails to provide a mechanism for the observed pattern of increasing returns (4).

Model

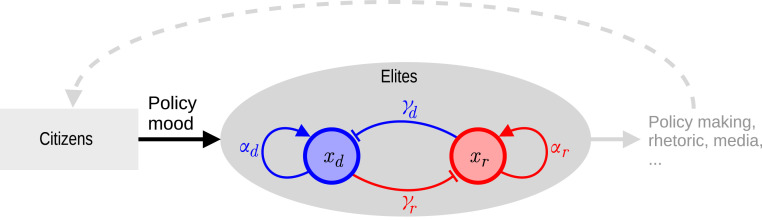

The model, illustrated in Fig. 2, describes the temporal dynamics of the ideological position of each of the two major elite populations in the US Congress. The influence of the changing position of US voters on the elites is introduced as an input to these dynamics. The model equations derive from the general model of opinion dynamics presented in refs. 22 and 23, which provides a versatile testbed for studying a wide range of behaviors in terms of a small number of parameters, even for a large number of independent decision makers forming opinions about multiple options (a specialization of this model is used in ref. 24). The versatility and analytical tractability of the model are central to our purpose: a principled and systematic investigation of key mechanisms that can help explain political polarization in the United States. The model is well suited to distinguishing among hypotheses, since it provides evidence to rule out a hypothesis that contradicts empirical data. The model can likewise be used to derive and evaluate potential strategies for depolarization.

Fig. 2.

Illustration of the model.

The general model of opinion dynamics (22, 23) describes processes that are inherently nonlinear: Inputs and exchanges in the model dynamics can strengthen key factors over time, but the resulting change in behavior is exhibited only once the strength of these factors increases beyond a critical threshold. Dynamics of this kind are observed ubiquitously in physical and biological systems as well as in social systems including, notably, in political polarization in the US Congress as measured by DW-NOMINATE scores (Fig. 1). See SI Appendix, section S1.A for details on the general model.

Elite Dynamics

We define and to represent the scalar ideological position of the Republican elites and the Democratic elites, respectively, in the US Congress at time , as measured in years. Ideological position is interpreted as center if it takes the value zero, liberal (left of center) if it takes a negative value, and conservative (right of center) if it takes a positive value.

For the Republican elite, we let represent an underlying conservative bias in ideological position at time . Republican self-reinforcement level denotes the strength, at time , with which the Republican elite reinforces its own ideological position. Republican reflexive partisanship level denotes the strength, at time , with which the Republican elite adjusts its ideological position in direct response to the changing ideological position of the Democratic elite. For the Democratic elite, we let represent an underlying liberal bias in ideological position at time . Democratic self-reinforcement level denotes the strength, at time , with which the Democratic elite reinforces its own ideological position. Democratic reflexive partisanship level denotes the strength, at time , with which the Democratic elite adjusts its ideological position in direct response to the changing ideological position of the Republican elite. The parameter represents the time scale (in years) of changing elite ideological position.

The model defines the rate of change of each of the two elite populations’ ideological positions as follows:

| [1] |

| [2] |

For derivation from the general model see SI Appendix, section S1.A.

For and , the products in [1] and in [2] represent self-reinforcement of ideological position among the Republican elites and the Democratic elites, respectively. To see that these terms provide positive feedback, assume that and at time . Then and drives to be more positive (conservative). Likewise, and drives to be more negative (liberal).

For and , the products in [1] and in [2] represent reflexive partisanship by the Republican elites and the Democratic elites, respectively. To see that these terms provide positive feedback, assume that and at time . Then and this drives to be more positive (conservative). Likewise, and this drives to be more negative (liberal).

In the absence of a positive feedback response of either type, we have that and the dynamics in [1] and [2] are linear. Then responds additively to and responds additively to , where we interpret and as input signals.

The hyperbolic tangent function “” provides a smooth, nonlinear “saturating” bound (between −1 and +1) on the value of its argument, which in [1] and [2] is the sum of the positive feedback terms from self-reinforcement and reflexive partisanship. This saturating function slows down the acceleration of ideological position away from center when the positive feedback gets very large. Without the function, the ideological positions could diverge without bound and at rates that are inconsistent with empirical data. We note further that saturating functions on positive feedback terms are applied in a wide range of models of natural phenomena, including political polarization (25).

The terms in [1] and in [2] provide a negative feedback that represents a nominal resistance to changing ideological position away from center. Negative feedback and positive feedback counteract each other, and there is a critical threshold where they are of equal magnitude. When positive feedback is smaller than negative feedback, ideological position is regulated close to center (tracking the bias value). When positive feedback is larger than negative feedback, ideological position can diverge significantly away from the center (and the bias value). A rigorous description and proof of these behaviors using bifurcation theory are provided in SI Appendix, section S1.B; see also SI Appendix, Fig. S1.

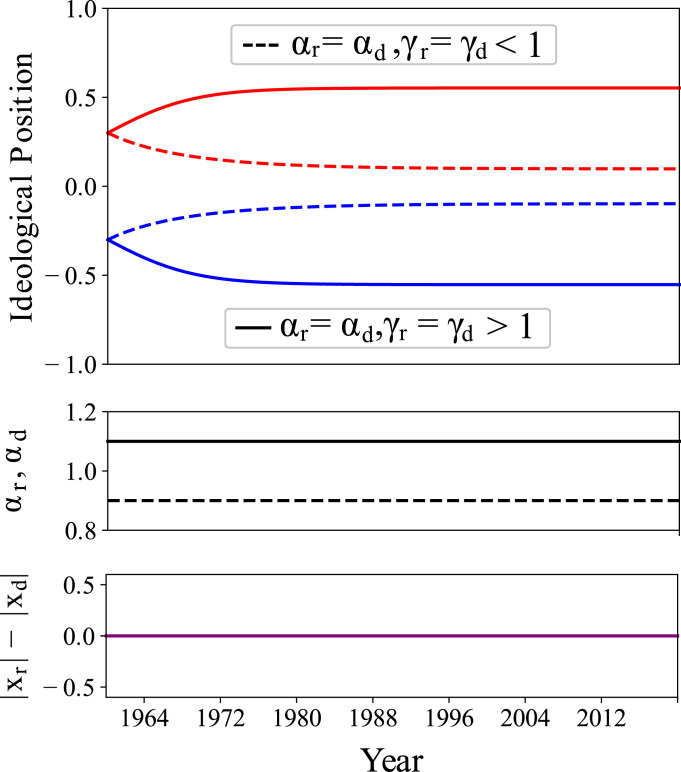

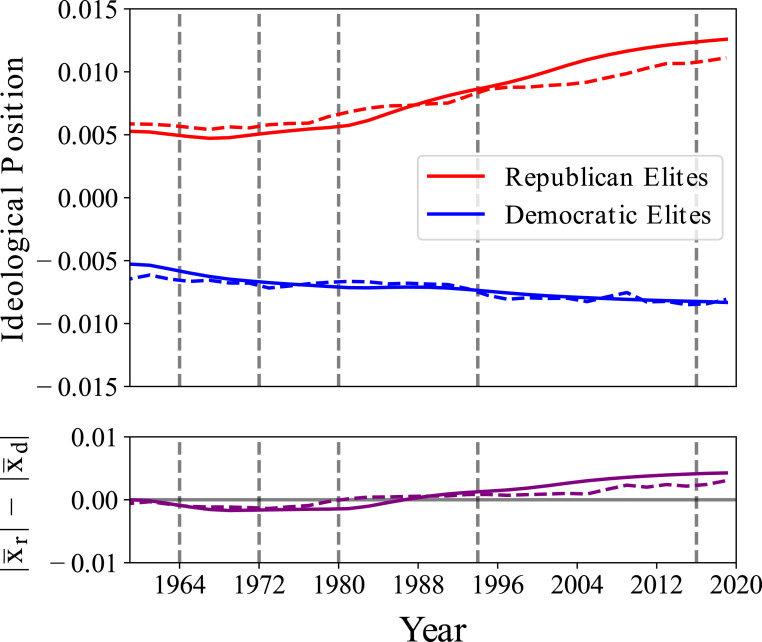

In Fig. 3, we illustrate how the modeled temporal dynamics of ideological position differ for positive feedback below the critical threshold compared to above the critical threshold. We use symmetric initial conditions ( and in 1959) and symmetric constant biases ( and ). We set y as a default for comparative purposes only. We let and . The critical value corresponds to equal positive and negative feedback terms. When , negative feedback dominates and and converge to near-center values (dashed lines). When , positive feedback dominates and and diverge significantly away from the center (solid lines). Because of the symmetry in parameters, the plots are identical for and if (dashed lines) and (solid lines).

Fig. 3.

Comparison of below-threshold and above-threshold positive feedback illustrates the interplay of positive and negative feedback mechanisms in the nonlinear model dynamics ([1] and [2]). Plotted as a function of time in years starting in 1959 are (Top) (red) and (blue); (Middle) ; and (Bottom) . Initial conditions are and . Parameters are y, , . Dashed lines correspond to and or and . Because or , negative feedback dominates and and are regulated toward the center. Solid lines correspond to and or and . Because or , positive feedback dominates and and diverge significantly away from center.

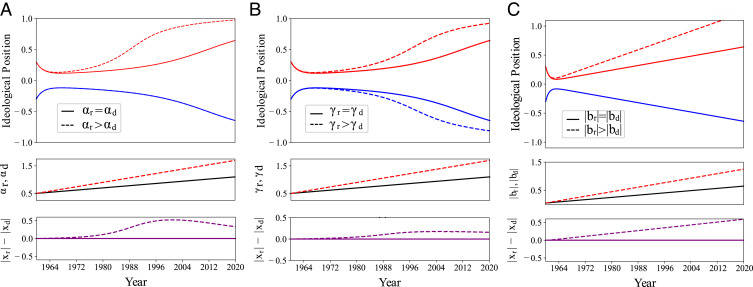

In Fig. 4, we compare the modeled temporal dynamics in [1] and [2] for the three hypotheses on the response mechanism for political elites. We illustrate how and evolve over time with a linear increase of party self-reinforcement levels , (hyp. A); reflexive partisanship levels , (hyp. B); and additive inputs , (hyp. C), in Fig. 4 A–C, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the model dynamics ([1] and [2]) for the three hypotheses on political elite response mechanism. Plotted as a function of time in years starting in 1959 are (A–C, Top) (red) and (blue); (A–C, Middle) (black is overlay of solid red, solid blue, and dashed blue); and (A–C, Bottom) (purple). For all simulations, , , and y. (A) Positive feedback from self-reinforcement (hyp. A): comparison of symmetric versus asymmetric increase in and over time. , , , and . Solid lines correspond to the symmetric conditions . While , and remain near the center, and when , they diverge symmetrically away from the center. Dashed lines correspond to the asymmetric conditions . In this case diverges sooner and ultimately more significantly than since sooner than . (B) Positive feedback from reflexive partisanship (hyp. B): comparison of symmetric versus asymmetric increase in and over time. Conditions are identical to those for A except that the roles of and are swapped and the roles of and are swapped. For the symmetric conditions (solid lines), and diverge symmetrically away from the center. For the asymmetric conditions (dashed lines), the asymmetry in the divergence of and is not as significant as in A. (C) Additive response (hyp. C): comparison of symmetric versus asymmetric increase in and over time. , and . Solid lines correspond to the symmetric conditions and dashed lines to . and linearly track and , respectively.

In Fig. 4A, party self-reinforcement levels and increase linearly in time with reflexive partisanship levels and biases and . When the positive feedback is below the critical threshold for either party, i.e., (respectively, ), then (respectively, ) remains close to the small bias; whereas after the positive feedback crosses above the critical threshold, i.e., (respectively, ), then (respectively, magnitude of ) grows significantly. It follows then that when and change symmetrically (solid lines), i.e., when , polarization is symmetric, and when and change asymmetrically (dashed lines), e.g., when increases at twice the rate as , polarization is asymmetric. We can also observe in Fig. 4A that (respectively, ) is very sensitive to changes in (respectively, ) near the critical value (respectively, ) and fairly insensitive to changes away from the critical value.

Fig. 4B shows the analogous simulation results for reflexive partisanship levels , increasing linearly in time with self-reinforcement levels and biases and . When and change symmetrically (solid lines), i.e., when , polarization is symmetric, as in Fig. 4A. However, when and change asymmetrically (dashed lines), e.g., when increases at twice the rate as , polarization is still much less asymmetric than in Fig. 4A. This lack of asymmetry in the temporal evolution of and can be attributed to the mutual influence of one position on the other. Even in the case that is significantly smaller than , if grows large, then the positive feedback term that drives up the magnitude of in [2] can get large enough to dominate the negative feedback and cause to diverge. This explains how (dashed blue line) in Fig. 4B starts to polarize even while and as a result the asymmetry in the polarization is relatively small. We show in SI Appendix, Fig. S2 that must be larger, by several orders of magnitude, than to get the same magnitude of asymmetry in polarization as observed in Fig. 4A.

Fig. 4C shows simulation results for the magnitude of inputs and increasing linearly in time with self-reinforcement and reflexive partisanship levels . For this hypothesis, and track the linear trajectories of and , respectively. There is no positive feedback and thus no critical threshold or increasing returns.

The model in [1] and [2] can also be derived as the population-average model reduction of an agent-based model that describes the evolution over time of each individual elite member’s ideological position. This agent-based model is described in SI Appendix, section S4. In SI Appendix, Figs. S9–S12, we provide simulations of the agent-based model with 50 Republican elites and 50 Democratic elites and show how our low-dimensional model of a Republican elite population and a Democratic elite population well represents a model of all 100 individuals, even when small individual differences in the single-agent dynamics are present in each group.

Voters and Policy Mood Input

To determine the role that aggregate public opinion preferences have played in driving asymmetric elite polarization, we seed our model of opinion dynamics with James Stimson’s (26) annual policy mood data. To create this measure, Stimson collected a large number of domestic policy survey questions and used a dyad ratio algorithm to extract latent dimensions of public opinion. The policy mood measure used here captures the first dimension and is commonly referred to as a left–right measure of ideology (21).

In modeling how members of the US Congress adapt their ideological positions to policy mood (PM) variations (20), it is natural to assume that they ignore minute jumps in public opinion. To model the effective PM input from voters to elite, we thus pass the PM data through a cascade of two filters (see SI Appendix, section S3 for details). The first one is a first-order high-pass filter, which extracts PM variations and removes any PM offset, i.e., puts the “zero” level at the average of the PM over time. The second one is a first-order low-pass filter, which removes high-frequency PM jitter. The PM data and the resulting filtered PM signal, , are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S8.

is also plotted in Fig. 5A. While a higher policy mood score usually indicates a more liberal mood, here we reverse the scale so it is consistent with the DW-NOMINATE scale. Observe that peaks (conservative swings) and valleys (liberal swings) of the filtered policy mood signal in Fig. 5A capture relevant historical events remarkably well. Conservative peaks occur just after passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, during the Reagan and Republican “Revolutions” of the 1980s and 1990s, and just prior to the election of President Trump. Liberal valleys occur in the middle of the Civil Rights Movement, following Watergate, in the waning years of the Reagan and George W. Bush presidencies, and recently as we approached the end of Trump’s single term in office. This is no surprise, as scholars have noted that policy mood peaks and valleys often coincide with a new party assuming the presidency (20, 27).

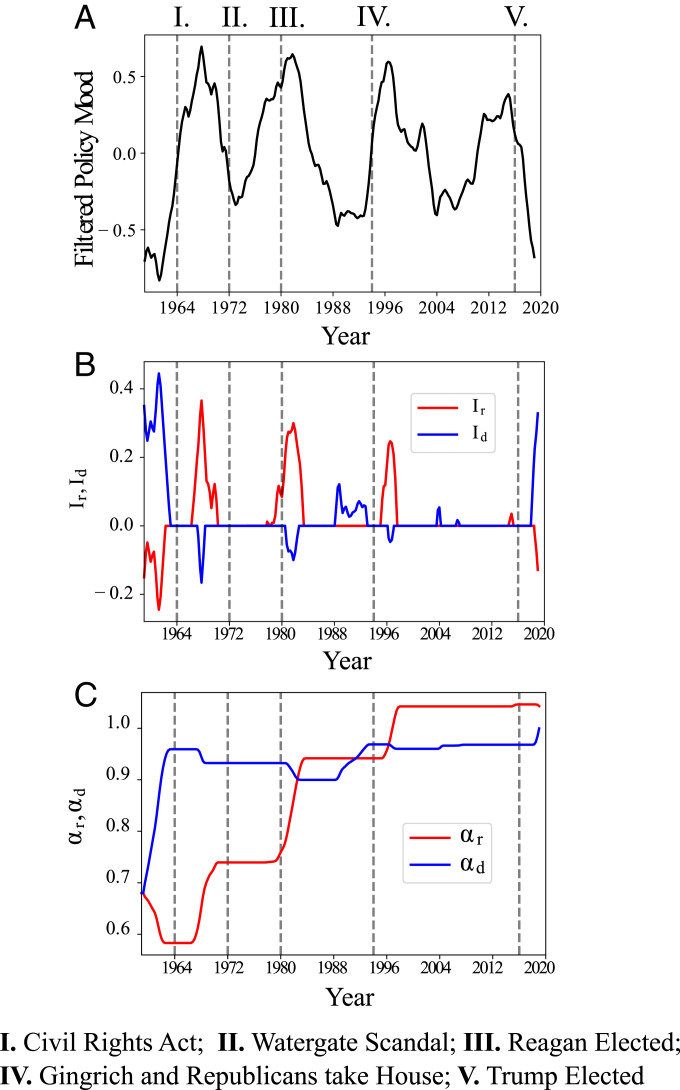

Fig. 5.

Illustration of how policy mood is used as an input to the model of elite dynamics ([1] and [2]). Plotted as a function of time in years are (A) the filtered policy mood ; (B) policy mood inputs and , each of which is a function ([5]) of the filtered policy mood ; and (C) the response of and to the policy mood input as modeled by [6] and [7] with . Vertical lines mark five notable events in recent US history. Observe that crosses the critical threshold of 1 just after event IV (Gingrich and Republicans take the House). Initial conditions and model parameters: , , , and .

The policy mood inputs and to Republican and Democratic elites are obtained by transforming through a generic nonlinearity

| [3] |

| [4] |

where is a function such that and is the basal elite ideological drive.

Because elites are sensitive only to policy mood variations, and thus insensitive to any policy mood offset in either direction, we have filtered the PM so that the signal has (close to) zero average. Doing so, however, implies that, in the long run, a linear function in the definitions 3 and 4 of the policy mood inputs to elites, and , cannot lead to any marked asymmetry in polarization. We assume that elites possess a threshold above which they become sensitive to policy mood swings and below which they are insensitive to them. This dead zone is akin to an “electoral blind spot” or “the policy region over which aggregate electorates do not enforce their preferences” (ref. 28, p. 577). Party elites know that voters will not enforce their preferences in this zone because they do not know enough about policy to be able to tell relatively moderate policy proposals apart (28) and because many issues are not salient enough to attract voters’ attention in the first place (29). Thus, only more extreme swings in policy mood will force elites to take notice and respond.

By assuming the existence of this dead zone, we define to be the nonlinear function

| [5] |

where and are upper and lower sensitivity thresholds, respectively. To allow for differences between parties we let and be the sensitivity thresholds for the Republicans and and those for the Democrats. Then, the policy mood input is as defined in [3] with and as in [4] with .

Policy Mood Input Drives Elite Self-Reinforcement Dynamics.

We first consider hyp. A. To account for the thermostatic adaptation of policymakers to policy mood, we let the policy mood inputs and affect elite dynamics through the self-reinforcing levels and . Elites cannot respond to changes in policy mood instantaneously. Their response must take the form of either adaptation, which involves advocating and enacting new policies, or selection, which involves electing new representatives. Both processes take time, which is why responsiveness is usually gradual and incremental (30).

To model the overall sensitivity of elite dynamics to PM, the rates of change of and are proportional to the policy mood inputs with the same proportionality constant :

| [6] |

| [7] |

Motivated by the empirical data (20, 27), the model captures a conservative/liberal shift of the public leading to a conservative/liberal shift of both parties of Congress through modulation of their ideological self-reinforcement.

The central hypothesis we propose with our modeling assumptions is that a large conservative swing in policy mood [] leads to an increase in the Republican elite ideological self-reinforcement if and a decrease in the Democratic elite ideological self-reinforcement if . Likewise, a large liberal swing in policy mood [] leads to an increase in the Democratic elite ideological self-reinforcement if and a decrease in the Republican elite ideological self-reinforcement if . And this can lead to a (possibly asymmetric) increase of the net polarizing positive feedback.

Policy Mood Input Drives Elite Reflexive Partisanship Dynamics.

To test hyp. B we consider our central hypothesis applied to reflexive partisanship levels and rather than self-reinforcement levels. To model this we apply and as input to dynamic changes in and , analogous to (and instead of) [6] and [7] with and small.

Policy Mood Input Drives Elite Additive Input Dynamics.

To test hyp. C we consider our central hypothesis applied to additive inputs and . To model this we apply and as input to dynamic changes in and , analogous to (and instead of) [6] and [7] with .

The simulations in the rest of this paper assume hyp. A where we let the time scale associated with the evolution of elite ideological position be y. We also explore other times scales and their implications in SI Appendix (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Simulations for hyp. B and hyp. C are presented in SI Appendix, along with details on our rigorous and robust analysis and comparison of how well each hypothesis captures the trends in the historical data on polarization and its asymmetry.

Results

Nonlinear Elite Response to Policy Mood Underlies Asymmetric Elite Dynamics.

The policy mood inputs and to the Republican and Democratic elites, respectively, are plotted as a function of time in Fig. 5B in the case that all sensitivity thresholds are the same: . The peaks in Fig. 5B reveal that swings in policy mood become smaller over time, at least until the one occurring in response to the Trump presidency. This could suggest that policy mood is becoming more stable, but it also may reflect that the issue preferences of Americans have been polarizing to a certain degree and becoming more rigid.

As can be observed in the plots of and , the nonlinearity in highlights the alignment of policy mood swings with key historical events. It also highlights that Republican policy mood swings are larger in magnitude and more prolonged than Democratic policy mood swings. This is the key difference that drives asymmetric elite polarization in our model.

We consider sensitivity thresholds that are symmetric between Republican and Democratic elites. In SI Appendix, Fig. S4, we explore the possibility of asymmetric thresholds—specifically that Republican elites might be less responsive to leftward swings than Democratic elites to rightward swings. The simulation results suggest Republicans would have crossed the critical threshold for “runaway” polarization much earlier (closer to 1980 than 1990) and that the asymmetric nature of elite polarization overall would have been much worse.

Policy Mood Input to Elite Self-Reinforcement Drives Asymmetric Polarization.

Each Republican/Democratic policy mood swing, as reflected in the input /, leads to a sharp increase in Republican/Democratic ideological self-reinforcement and a modest decrease in Democratic/Republican ideological self-reinforcement. The asymmetry in conservative versus liberal policy mood swings translates into asymmetric temporal evolution of the modeled ideological self-reinforcement levels and (Fig. 5C).

Both and are overall increasing, which leads to increasing polarization as illustrated in Fig. 6. This is consistent with the mechanistic explanation illustrated in Fig. 4A. The Republican self-reinforcement level remains well below the threshold for runaway polarization (equal to 1 in our model) until around 1980, corresponding to the beginning of the Reagan period. Around that date, undergoes a dramatic increase, which brings the Republican elite close enough to the runaway polarization threshold to see escalating polarization. In line with empirical data (Fig. 1), a second Republican polarization bump is observed during the Newt Gingrich era. This second bump pushes above the threshold for runaway polarization.

Fig. 6.

Simulation results of model dynamics ([1] and [2]) with self-reinforcement levels and changing as shown in Fig. 5C in response to policy mood input and shown in Fig. 5B according to dynamics ([6] and [7]) with nonlinear function defined by [5] with . Initial conditions and model parameters: , , , , , and .

According to the model results of Fig. 6, Democratic elites had two periods of leftward movement: in the early 1960s and again in the early 1990s. The latter accords with empirical data but the former does not. This suggests Democratic elites may have missed an opportunity to capitalize fully on a leftward swing in policy mood. It could also reflect the ideological heterogeneity of the Democratic coalition. A Democratic party that includes both liberals and conservatives would be less likely to fully embrace a liberal policy mood signal than a party that contains only liberals. After the Civil Right Act in 1964, conservatives steadily sorted out of the Democratic party, likely increasing its responsiveness to public opinion.

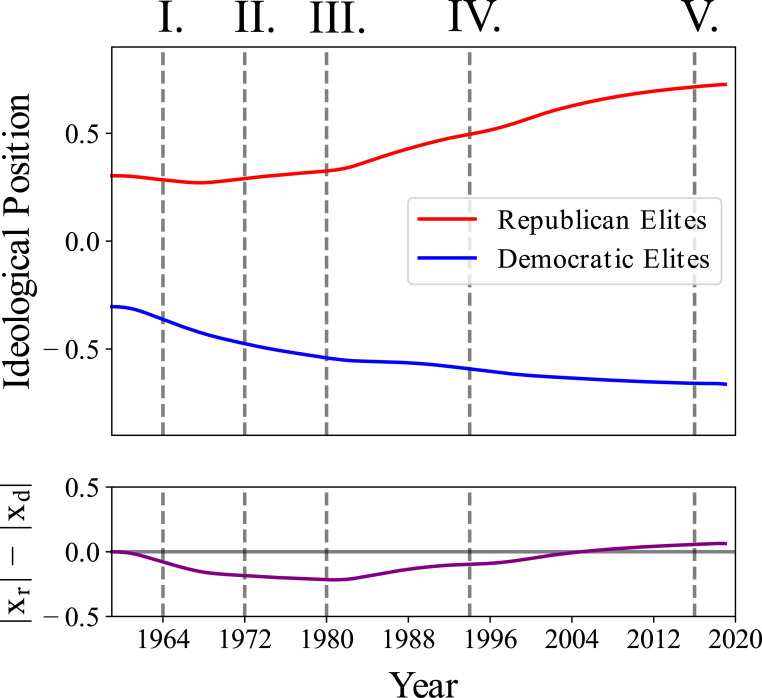

We can adjust our model to allow for Democratic responsiveness to large liberal policy mood swings to start relatively small and grow over time by letting the sensitivity threshold decrease over time in a linear fashion across the 1960s and 1970s, as shown in Fig. 7A. Fig. 7 shows that this modification reduces Democratic polarization in the early 1960s and lets our model better approximate the empirical data (Fig. 8). The smaller leftward movement of the Democrats in the early 1960s distinguishes Fig. 7 B and C from Fig. 5 B and C, respectively. In line with empirical data (Fig. 1), a marked Republican polarization begins substantially earlier than Democratic polarization. The Democratic self-reinforcement level remains below the threshold for runaway polarization in Figs. 5C and 7C, although there is a steep increase recently during the Trump presidency.

Fig. 7.

Increasing Democratic responsiveness to liberal policy mood swings. Democratic elites gradually become more responsive over time to policy mood swings throughout the 1960s and 1970s, as modeled by the time-varying plotted in A. The other sensitivity thresholds are , as in Fig. 6. All other parameters and initial conditions are the same as in Fig. 6. (B and C) The resulting policy mood inputs and (B) and response of and (C) to these policy mood inputs. (D) The qualitative trends in ideological positions and the asymmetry in the polarization can be compared to the DW-NOMINATE scores in Fig. 1; see Fig. 8.

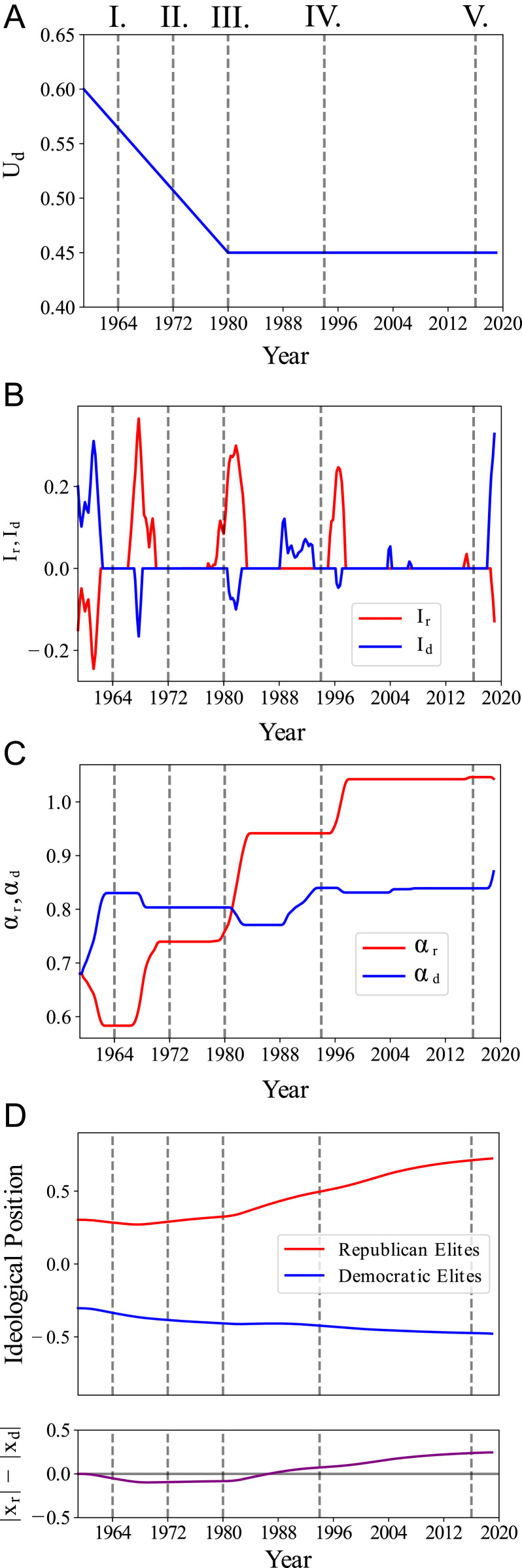

Fig. 8.

Comparison of simulation results (solid lines) of Fig. 7 with DW-NOMINATE scores (dashed lines) of Fig. 1, after normalization. Bottom panel compares the asymmetry in polarization in the simulation (solid purple line) with that in the DW-NOMINATE scores (dashed purple line).

We emphasize that no data fitting was performed in obtaining Figs. 5–8. The largely agnostic linear filtering and threshold nonlinearity applied to policy mood data are responsible for the sharply asymmetric course of voter influence over elites. These results are independent of modeling details, for the most part, and robust to parameter variations. In other words, the results are intrinsic to the policy mood data. The results are also agnostic to whether or not the voters are polarized. The resulting asymmetric increase in polarizing positive feedback is both in line with existing self-reinforcement theory of polarization and unique, in that it connects those theories to an asymmetric influence of policy mood over elites.

We evaluate how well the results of Fig. 7 match the DW-NOMINATE scores by plotting in Fig. 8 both the normalized simulated trajectories, and , and the normalized DW-NOMINATE scores (see SI Appendix, section S2.F for details on the normalization). The difference curves (purple) in Fig. 8, Bottom measure the asymmetry in the polarization: The simulation (solid curve) slightly overpredicts the asymmetry in the DW-NOMINATE scores (dashed curve) after 1996. This suggests that the asymmetry in elite polarization could have been worse, given how much swings in policy mood have favored conservatives over the last half century.

There are four key parameters in the model that can make a significant difference in how well the results match the DW-NOMINATE scores and their asymmetry. In SI Appendix, section S2.F, we present a robust analysis of hyp. A where we computed the equivalent of Fig. 8 from 1979 to 2019 over a range of values for each of these four key parameters: , , , and , where , , , and . Each of the 4,000 simulations corresponds to a different combination of parameter values, and for each one we computed the mean-square error (MSE) of normalized trajectories compared to normalized DW-NOMINATE scores. Over the 4,000 simulations, the lowest MSE is , achieved with and , yielding a difference curve that closely captures the polarization asymmetry in the data. We evaluate how well asymmetry is captured with two measures (SI Appendix, Table S2). The first one is the mean-square error in the difference curves (MSEdif). The second one is the “polarization asymmetry index (PAI),” which is the ratio of the simulated difference to the DW-NOMINATE score difference in 2019 (after normalization). Here, MSEdif = 5.00 and PAI = 0.80. The PAI indicates that the results slightly underpredict the asymmetry. This is consistent with the relatively large having more of a moderating effect on than on since the biggest swings during the period analyzed were to the right.

Alternative and Null Hypotheses: Reflexive Partisanship, the Breakdown of Norms, and Additive Response.

We consider and reject our alternative and null hypotheses on elite response mechanisms. Considering hyp. B, we let the asymmetric policy mood drive the elite reflexive partisanship levels . However, as predicted by Fig. 4B, applying the policy mood inputs and to the reflexive partisanship levels and does not lead to asymmetric polarization. This is the result of the mutual response associated with reflexive partisanship, which is independent of the ratio of to . This is illustrated in SI Appendix, Fig. S5A, which shows virtually no asymmetry in the results analogous to Fig. 6, i.e., with policy mood input to and given as in [6] and [7] with and as given by Fig. 5B and . Similarly, SI Appendix, Fig. S5B shows virtually no asymmetry in the results analogous to Fig. 7, i.e., with policy mood input to and given as in [6] and [7] with and as given by Fig. 7B and . We plot the equivalent of Fig. 8 in SI Appendix, Fig. S6, where we see gross underprediction of asymmetry in polarization.

To make rigorous our rejection of reflexive partisanship as the dominant elite response mechanism, we performed the analogous robust analysis of hyp. B as for hyp. A, running 4,000 simulations over the same combinations of parameters. As reported in SI Appendix, Table S2, the lowest MSE is , achieved with and , which underperforms compared to hyp. A. Further, as the plot in SI Appendix, Table S2 shows, even with a best choice of parameters, the simulation under hyp. B can still not capture the asymmetry in polarization in the data (MSEdif = 6.23 and PAI = 0.57).

Considering hyp. C, the null hypothesis, we let the asymmetric policy mood drive the elite additive input levels , . However, as predicted by the theory and illustrated in Fig. 4C, the simulated trajectories simply track the policy mood. To make rigorous our rejection of additive response as a mechanism that can explain the data, we performed the analogous robust analysis of hyp. C as for hyp. A and hyp. B, running 4,000 simulations over combinations of the same four parameters. As reported in SI Appendix, Table S2, the lowest MSE is , achieved with and , which reflects relatively poor performance overall. Importantly, as seen in the plot in SI Appendix, Table S2, even with best parameters, the simulation under hyp. C is not at all representative of the asymmetry in polarization in the data (MSEdif = 17.39 and PAI = 0.45).

We additionally hypothesized that perhaps it was not increasing reflexive partisanship but the breakdown of bipartisan norms, which began in the 1970s, that accounts for the rise of asymmetric polarization (31). To test this, we used the same conditions as in Fig. 6 but applied a small negative , where . As SI Appendix, Fig. S7 suggests, even if norms of bipartisanship had endured, it would not have prevented the rise of asymmetric polarization.

We have used estimates of citizen preferences from data (policy mood) as input to our model of the evolution over time of the ideological position of elites. We have compared model output to estimates of ideology from data (DW-NOMINATE scores). Parameters , , , and and variables and are not so easily estimated from data. However, we have shown that for reasonable choices of parameters the model robustly provides output that is consistent with the historical data and, with it, predictions on trends in variables. For a future work, we propose using extended Kalman filtering for our nonlinear model, much as linear Kalman filtering was used in ref. 20. As suggested in ref. 20, extracting the model parameters that best explain historical data constitutes a regression on aggregated macroscopic variables and parameters, such as party self-reinforcement or sensitivity to policy mood swings.

Conclusion

Social scientists have offered a wide range of explanations for the rise of elite polarization in the United States. By focusing on feedback mechanisms, our model integrates the various explanations for polarization within a single framework. Interest group pressure, increases in party discipline, ideological sorting, changes to the media environment, and other suggested hypotheses are different manifestations of reinforcement that drive polarization upward and that feed off one another.

This article underscores why it is so important to understand how political processes reinforce themselves and each other through positive feedback and, therefore, connects polarization to a broader literature on path dependency and self-reinforcement (4, 5, 32). Social processes such as polarization are dynamic—just as so many processes in nature are—and our models must reflect that. In fact, by ruling out hyp. C, we show that explanations that do not account for positive feedback cannot account for historical patterns of polarization. Viewing polarization through this lens reveals critical thresholds or moments when processes become difficult if not impossible to reverse. Our model suggests that this threshold has been crossed by Republicans in Congress and may very soon be breached by Democrats.

Our results also demonstrate that a critical threshold divides a state envisioned by the Responsible Party Model wherein the political parties are distinct, effective, and accountable to the voters and a state that begets unchecked polarization driven by self-reinforcement. Political scientists are, perhaps, more aware than most that democracies die and that polarization can be a leading cause in their demise (1). The authors of the 1950 American Political Science Association report calling for the parties to differentiate themselves could not have imagined where those parties would end up 70 y later. They did emphasize that the parties should not only offer distinct policy platforms but also be “effective” or “able to cope with the great problems of modern government” (ref. 33, p. 17). There may be an optimal level of differentiation beyond which effectiveness is harmed (34).

Our model finds that public opinion has an important role to play in the asymmetric nature of elite polarization. However, rather than mass polarization driving elite polarization (or vice versa), we argue that shifts in aggregate public opinion, i.e., not necessarily mass polarization, can drive asymmetric elite polarization. This finding is all the more remarkable because researchers have not, as far as we know, noted that swings in policy mood are asymmetric, either in magnitude or in duration. These differences, compounded over time, can account for the asymmetry we observe in elite polarization. That said, while we treat policy mood as an input in our analysis, future research could extend our model and use instead DW-NOMINATE scores as inputs to then model policy mood.

While our model suggests that policy mood plays an important role in the asymmetric nature of elite polarization, it also suggests that reflexive partisanship does not. Although scholars have suggested antipathy toward the opposing party might be stronger among Republicans (35), reflexive partisanship cannot account for the magnitude of the asymmetry observed in the system even if this is the case. This is because the polarizing effects of such antipathy outweigh its asymmetric effects.

Finally, perhaps one of the most sobering results of our analysis is that we find that as self-reinforcement increases, parties become increasingly less responsive to policy mood. Once self-reinforcement, driven by policy mood, crosses a critical threshold, polarization dynamics become completely dominated by positive feedback. Hence, while public opinion can drive initial polarization, it may be relatively powerless to stop it. Future research might test the limits of this finding, however. For instance, it might consider how an abrupt and sustained leftward swing in public opinion could affect current levels of polarization.

Additionally, while our model primarily looks backward, and explains the polarization dynamics of the last 70 y, future research can use the model as a testbed to evaluate mechanisms for decreasing polarization. For instance, assuming that policy mood continues to have a conservative bias, would decreasing Republican sensitivity to it overcome the positive feedback effects identified here? Turning to the agent-based version of the model, how many and which legislators need to exogenously decrease their sensitivity to positive feedback to decrease polarization? In other words, can one senator, perhaps centrally located, unilaterally decrease polarization? Agent-based models could also be used to examine the role of party heterogeneity on self-reinforcement and, ultimately, polarization. We hope this model will provide researchers with a simple but powerful tool for exploring ways to mitigate, if not reverse, the polarization dynamics that are threatening the long-term stability of this country.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the anonymous reviewers for many helpful comments. This research was supported by Direcciòn General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), through the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT) research grant IN102420, and by Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología (Conacyt) through the research grant CB-A1-S-10610 (to A.F.) and by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program under Grant DGE-2039656 (to A.B.). Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the NSF.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/ doi:10.1073/pnas.2102149118/-/DCSupplemental.

*There is currently a debate about the extent to which ideal point estimates, such as DW-NOMINATE scores, reflect ideological or partisan conflict (9, 10) or merely voting coalitions (11). The fact that this article shows ideological swings in aggregate public opinion contribute to polarization dynamics, as reflected in DW-NOMINATE scores, suggests they do in fact capture some element of ideology. If DW-NOMINATE is, in fact, solely a measure of voting coalitions, our model is still valuable as it demonstrates that the political behavior of governmental elites is responsive to policy mood. (We are grateful to an anonymous reviewer for making this point.)

Data Availability

All study data are included in this article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Levitsky S., Ziblatt D., How Democracies Die (Broadway Books, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee F. E., Beyond Ideology: Politics, Principles, and Partisanship in the US Senate (University of Chicago Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorina M., Abrams S., Disconnect: The Breakdown of Representation in American Politics (University of Oklahoma Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pierson P., Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 94, 251–267 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pierson P., Schickler E., Madison’s constitution under stress: A developmental analysis of political polarization. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 23, 37–58 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty N., Polarization: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grossmann M., Hopkins D. A., Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats (Oxford University Press, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mann T., Ornstein N., It’s Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism (Basic Books, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee F. E., Patronage, logrolls, and “polarization”: Congressional parties of the gilded age, 1876-1896. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 30, 116 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCarty N., In defense of DW-NOMINATE. Stud. Am. Polit. Dev. 30, 172 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gailmard S., Jenkins J. A., Distributive politics and congressional voting: Public lands reform in the Jacksonian era. Public Choice 175, 259–275 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiSalvo D., Engines of Change: Party Factions in American Politics, 1868-2010 (Oxford University Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Noel H., Political Ideologies and Political Parties in America (Cambridge University Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skocpol T., Hertel-Fernandez A., The Koch network and Republican Party extremism. Perspect. Polit. 14, 681–699 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abramowitz A., The Disappearing Center: Engaged Citizens, Polarization, and American Democracy (Yale University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiorina M., Abrams S., Pope J., Culture War: The Myth of a Polarized America (Longman, 2005). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lelkes Y., Sniderman P. M., The ideological asymmetry of the American party system. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 46, 825–844 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Webster S. W., American Rage: How Anger Shapes our Politics (Cambridge University Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wlezien C., The public as thermostat: Dynamics of preferences for spending. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 39, 981–1000 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Erikson R., MacKuen M., Stimson J., The Macro Polity (Cambridge University Press, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stimson J., Public Opinion in America: Moods, Cycles, and Swings (Routledge, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bizyaeva A., Franci A., Leonard N. E., Nonlinear opinion dynamics with tunable sensitivity. arXiv [Preprint] (2020). https://arxiv.org/abs/2009.04332 (Accessed 6 September 2021).

- 23.Franci A., Bizyaeva A., Park S., Leonard N. E., Analysis and control of agreement and disagreement opinion cascades. Swarm Intell. 15, 47–82 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos F. P., Lelkes Y., Levin S. A., Link recommendation algorithms and dynamics of polarization in online social networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e102141118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Callander S., Carbajal J. C., Cause and effect in political polarization: A dynamic analysis. J. Polit. Econ., in press.

- 26.Stimson J., Data from “Public Policy Mood” (2021). https://stimson.web.unc.edu/data/ (Accessed 6 September 2021).

- 27.Soroka S., Wlezien C., Degrees of Democracy: Politics, Public Opinion, and Policy (Cambridge University Press, 2010). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bawn K., et al., A theory of political parties: Groups, policy demands and nominations in American politics. Perspect. Polit. 10, 571–597 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Highton B., Issue accountability in US House elections. Polit. Behav. 41, 349–367 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Caughey D., Warshaw C., Policy preferences and policy change: Dynamic responsiveness in the American states, 1936–2014. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 112, 249–266 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mann T., Ornstein N., The Broken Branch: How Congress is Failing America and How to Get it Back on Track (Oxford University Press, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Page S., Path dependence. Quart. J. Polit. Sci. 1, 87–115 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toward a more responsible two party system: A report of the Committee on Political Parties. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 44, 1–96 (1950). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Binder S. A., Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock (Brookings Institution Press, 2004). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason L., Uncivil Agreement: How Politics Became our Identity (University of Chicago Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in this article and/or SI Appendix.