Abstract

Aim

This review aimed to examine and describe the published research on nursing home (NH) nurses' turnover intentions in their workplace.

Design

This study is a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines.

Methods

An electronic search was conducted for English and Korean articles to identify research studies published between 2009–2019 using CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, RISS, and DBpia.

Results

A total of six studies met the inclusion criteria and revealed NH nurses' turnover intentions. The factors influencing NH nurses' turnover intentions were identified and classified as individual and organizational factors. Among the various factors above, this study found that job satisfaction was the most influential factor in nurses' turnover intentions. Therefore, further efforts are required to increase NH nurses' job satisfaction to decrease turnover intention.

Keywords: nurse, nursing homes, turnover intention

1. INTRODUCTION

The number of elderly people (≥aged 65 years) across the globe has rapidly increased, reaching more than two billion worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020). As a result, the number of elderly people who lose their ability to take care of themselves continues to increase (Vermeerbergen et al., 2017). Often, elderly care cannot be satisfied at home; thus, the responsibility for elderly care has gradually transferred to society, and the number of nursing homes (NHs) has rapidly increased since the 1970s (Willemse et al., 2014). At the same time, securing an appropriate number of nurses who affect NH residents' health outcome is a major challenge due to the lack of nurses and their high turnover rate in NHs (White et al., 2020). The 1‐year turnover rate of NH nurses is between 19.0%–55.0% (Antwi & Bowblis, 2018; Castle et al., 2007; Cohen‐Mansfield, 1997).

A high nurse‐turnover rate in NHs makes it difficult to assess residents and implement management plans, reduces the intimacy between nurses and residents, makes it more difficult to detect complications and health failures due to the decreased nursing care continuity and affects residents' health outcome through poor supervision and education (Thomas et al., 2013). Accordingly, high nurse turnover in NHs relates to more pressure sores among residents (Trinkoff et al., 2013), use of antipsychotic medications (Shin et al., 2020), hospital admissions (Thomas et al., 2013) and mortality (Antwi & Bowblis, 2018). For organizations, high nurse turnover in NHs leads to substantial costs such as recruitment and training for new nursing staff (Griffeth et al., 2011; Uchida‐Nakakoji et al., 2016). Due to residents' health outcomes and the high costs of nursing turnover, NH nursing administrators and healthcare policymakers must be able to identify factors related to NH nurses' turnover.

Turnover intention is known as one of the best proxies for actual turnover (Alexander et al., 1998). Krausz et al. (1995) reported that before the turnover occurred to nurses, manifestations such as the turnover intention precede it. Therefore, identifying the factors related to nurses' turnover intentions and controlling the turnover rate is essential for NHs to increase residents' health outcome and increase the organization's profit. Some studies identified the predictors of NH nurses' turnover intentions (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kash et al., 2010; Kash et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2014; Park et al., 2009). Some studies reported individual factors, such as job satisfaction and job demand that affect NH nurses' turnover intentions (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kuo et al., 2014). Park et al. (2009) first investigated the factors related to NH nurses' turnover intentions in Korea and revealed the factors relate to turnover intentions among various individual factors (demographic and job characteristics). Additionally, nurses at paid NHs have low turnover intentions (Park et al., 2009). Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al. (2010) and Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al. (2010) investigated not only the individual factors but also the organizational factors that affect NH director of nurses' (DONs) turnover intentions.

Previous systematic reviews were conducted to review the factors associated with NH nurses' actual turnover (Cohen‐Mansfield, 1997) or turnover intentions of only acute care setting nurses (Falatah & Salem, 2018; Kim & Kim, 2011). Although turnover intention is a major prior manifestation of actual turnover, little attention is paid to the review of NH nurses' turnover intentions. This study provides the findings of a literature review regarding NH nurses' turnover intentions in their workplace, the related individual and organizational variables affecting their turnover intentions, and the degree of turnover intention. Understanding this finding is important to retain nurses in NHs. When the nursing community has a better and more diverse understanding of why nurses have turnover intentions, it provides the community an opportunity to address the issues and make appropriate changes to decrease nurses' turnover intentions. This understanding will lead to greater NH nurse retention and improve NH residents' health outcome.

2. AIMS AND METHODS

2.1. Aims

The aim of this review was to examine and describe the published literature on NH nurses' turnover intentions in their workplace.

2.2. Search methods

A literature search of six electronic bibliographic databases (CINAHL, PubMed, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, RISS and DBpia) was conducted in June 2020. The study's timeframe was restricted to the period from January 2009 to January 2019 to only examine papers with updated and relevant information concerning the presenting problem. Search terms included combinations of the following keywords: “nur” and “nursing home” or “residential facility” or “long term care facility” or “residential care” or “long term care setting” and “leave” or “turnover.” Reference lists from the included articles about NH nurses' intentions to leave their workplace were also screened to find literature not identified via electronic bibliographic databases. Only studies that met the following criteria were included in this study: (i) the sample (individual) had to include nurses (registered nurses [RNs] or licensed practical nurse [LPNs]); (ii) the sample (organization) had to include NHs; (iii) the languages had to be either in English or Korean because translators were not used; and (iv) studies published in peer‐reviewed journals. The exclusion criteria included articles which involved unlicensed nursing staff, such as CNAs (Certified Nursing Assistants), because the articles were likely to provide distorted results.

2.3. Search outcome

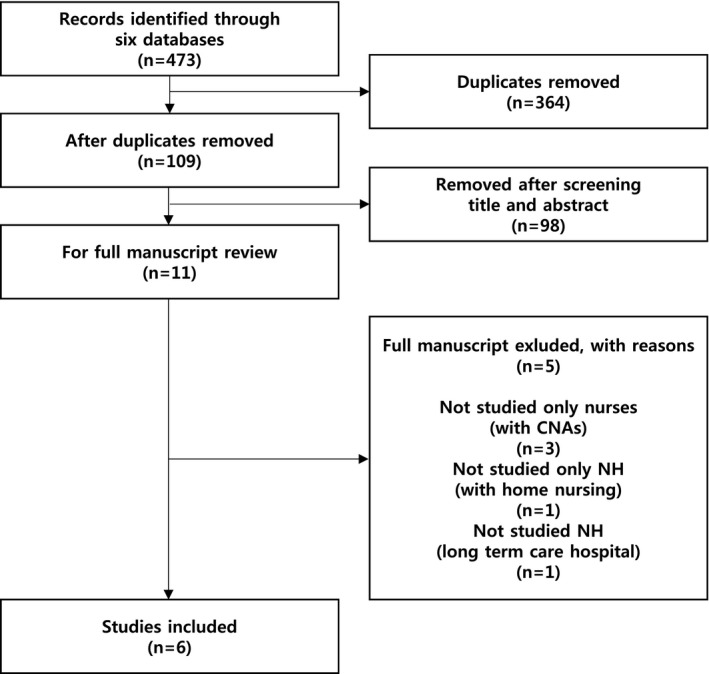

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analysis (PRISMA) diagram explains how articles were selected (Moher et al., 2009). In this study, the PRISMA guidelines directed the systematic review process (see Figure 1). The original search located 473 articles across the six databases. After duplicates were excluded, the initial search yielded 109 papers. Following this, two reviewers (author 1, research assistant 1) independently reviewed the titles and abstract of the remaining 109 papers. After screening their titles and abstracts, 11 papers remained. Inconsistencies and uncertainties about screening were discussed with the third reviewer (research assistant no. 2), to reach agreement. Of the remaining 11 papers, two reviewers (author 1, research assistant no. 1) assessed the full‐text for eligibility through inclusion and exclusion criteria. One reviewer (research assistant no. 2) contributed to resolving inconsistencies and uncertainty regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria of the study. After assessing, three papers' samples were RNs and CNAs, one paper's setting was NHs and home nursing, and one paper's setting was a long‐term care hospital. Finally, six papers remained, and six papers related to NH RNs' intentions to stay in their workplace were reviewed and synthesized.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for study selection (PRISMA)

2.4. Quality appraisal

Many tools, checklists and evaluation systems are available in the literature for each type of study such as CASP checklists and Cooper's checklist. Among them, Cooper (1998) proposed that the extraction of specific methodological characteristics of the study can evaluate the study's overall quality. Cooper (1998) presented a research question and sample demographics; included power analysis; reported the recruitment, response rate, instrument's reliability data and sample size; described the instrument's development; and established the instrument's validity as specific methodological characteristics of the study. Table 1 presents the six studies' methodological description. Two reviewers (author 1, research assistant no. 1) assessed six studies. If there was a disagreement about methodological description (Table 1), third reviewer (research assistant no.2) evaluated the research paper. Discussions were held until consensus among the three reviewer (author 1, research assistant no.1, 2). Although there was a lack of methodological research such as a lack of information about power analysis and response rate, all studies were included because the purpose of this study was to extensively review NH nurses' turnover intentions.

TABLE 1.

Methodological description of the studies reviewed

| Methodological details | Park et al. (2009) | Kash et al. (2010) | Kash et al. (2010) | Filipova (2011) | Kuo et al. (2014) | Chen et al. (2015) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research question presented | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Power analysis included | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Recruitment reported | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Response rate % | 86.4 | 97.0 | 56.0 | 21.4 | 48.1 | * |

| Demographic of the sample presented | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Sample size N = | 258 | 1,016 | 572 | 656 | 173 | 186 |

| Development of the instrument described | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Reliability data of the instruments reported | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Validity of the Instrument established | + | + | + | + | + | + |

+ = yes; − = no; * = No details available.

2.5. Data extraction/synthesis and analysis

The following data fields from the six selected studies were extracted and synthesized: author, year, country, sample and origin, design, factor analysed, study findings, and degree of turnover intention (see Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Summary of studies in the review

| No | Author (Year), Country | Sample and | Design | Factor analysed | Findings | Consider leaving NH | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Park et al. (2009). Korea | 280 RNs from 258 NHs in Korea | Cross sectional |

Individual factor: marital status, religion, education level, job position, income, age of the RN, years of clinical experience, years of NH experience, work type, satisfaction with current facility, number of turnover experience, job stress, job satisfaction Organizational factor: facility type, number of RNs, number of residents |

Individual factor: single (marital status), age of the RN ↑, years of clinical experience ↓, satisfaction with current facility↑, number of turnover experience↓, job stress ↓, job satisfaction↑ => RN turnover intention ↓ Organizational factor: paid NH(facility type) => RN turnover intention ↓ |

In 5‐pint Likert scale (with higher scores representing higher turnover intention), mean score was 3.12 | ||||

| 2 | Kash et al. (2010). US |

1,016 DONs from 626 NHs in US + The 2003 Texas Nursing Facility Medicaid Cost Report +The 2003 Area Resource File for Texas |

Cross sectional |

Individual factor: Years of education, Years worked at the facility, job satisfaction, perceptions of empowerment Certification in geriatrics or gerontology, pay) Organizational factor: Ownership type, Number of beds, Occupancy rate, RN HPRD, LVN turnover rate, CNA turnover rate, Case mix index, Proportion Medicare days, Proportion Medicaid days, Proportion private days, Reimbursement rate, |

Individual factor: Years of education ↓, job satisfaction ↑, perceptions of empowerment ↑, pay ↑ => DON turnover intention ↓ Organizational factor: Non‐profit (Ownership type), RN HPRD ↑, Proportion Medicaid days↓ => DON turnover intention ↓ |

In 5‐point Likert‐ scale and were recoded into a binary variable coded 1 if the respondent chose strongly agree, agree, or neutral as an answer. The dummy variable was coded 0 if the respondent answered with strongly disagree or disagree. mean score was 0.15 |

||||

| 3 | Kash et al. (2010). US |

572 DONs from 572 NHs in US +2003 The Texas Nursing Facility Medicaid Cost Report +The 2003 Area Resource File for Texas |

Cross sectional |

Individual factor: education level, years licensed, years of LTC employment, Years at current facility, Pay, Perception of regulatory stress, job satisfaction, perceptions of empowerment Organizational factor: ownership type, number of beds, Occupancy rate, professional staff ratio, agency staff ratio, reimbursement rate, case mix |

Individual factor: Job satisfaction ↑, pay↑, level of empowerment ↑, education level ↓ => DON turnover intention ↓ Organizational factor: non‐profit (ownership type) => DON turnover intention ↓ |

In 5‐point Likert‐ scale and were recoded into a binary variable coded 1 if the respondent chose strongly agree, agree, or neutral as an answer. The dummy variable was coded 0 if the respondent answered with strongly disagree or disagree. (1) turnover intention in next 12 months: mean score was 0.15 (2) turnover intention in next 24 months: mean score was 0.15 |

||||

| 4 | Filipova (2011). US | 656 licensed nurses from 110 NHs in US | Cross sectional | Individual factor: perceived organizational support, organizational commitment, job satisfaction, ethical climate | Individual factor: job satisfaction ↑, organizational commitment ↑ => nurse turnover intention ↓ | In 5‐point Likert‐ scale (with higher scores representing higher turnover intention), mean score was 2.6 | ||||

| 5 | Kuo et al. (2014). Taiwan | 173 nurses 110 NHs in Taiwan | Cross sectional | Individual factor: work stress, job satisfaction | Individual factor: job satisfaction ↑ => nurse‐turnover intention ↓ |

In 5‐point Likert‐ scale, 4 items (with higher scores representing higher turnover intention), mean score was 10.01 |

||||

| 6 | Chen et al. (2015). Taiwan | 186 licensed nurses (RN and LPN) from 25 NHs in Taiwan | Cross sectional | Individual factor: Intrinsic job satisfaction, Extrinsic job satisfaction, Job demand | Individual factor: Intrinsic job satisfaction↑, Extrinsic job satisfaction↑, Job demand ↑=> Nurse (RN and LPN) turnover intention ↓ | 12% of nurses were high turnover intention, 57% were middle turnover intention, 31% were low turnover intention | ||||

Abbreviations: DON, director of nursing; HPRD, hours per resident day; LPN, licensed practical nurse; LTC, long‐term care; LVN, licensed vocational nurse; NH, nursing home; RN, Registered Nurse.

2.6. Ethical considerations

No ethical clearance was required for this review.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Study characteristics

In this review, all six studies used a cross‐sectional design with observational study (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2014; Park et al., 2009; see Table 2).

The studies were conducted in Korea (Park et al., 2009), the United States (Filipova, 2011; Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010), and Taiwan (Chen et al., 2015; Kuo et al., 2014). These studies' findings were published in English (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2014; Park et al., 2009) and Korean (Park et al., 2009). The nurse sample size ranged from 173 nurses to 1,016 nurses. As for turnover intention determinants, all studies considered individual factors (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2014; Park et al., 2009) and three studies considered organizational factors (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Park et al., 2009).

3.2. Turnover intention determinants

In this review, turnover intention determinants were categorized into individual and organizational factors.

3.2.1. Individual factors

Demographic and psychosocial factors were recognized within the individual factors.

Demographic factors

Three of the six studies examined and reported that statistically significant relationships exist between the demographic factors and DONs' turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Park et al., 2009). Older nurses had fewer turnover intentions (Park et al., 2009). Lower educational levels associated with lower DON turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010), whereas Park et al. (2009) reported that educational level did not have a statistically significant relationship with RNs' turnover intentions. Higher perceived pay competitiveness associated with lower DON turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010), whereas Park et al. (2009) reported that pay did not have a statistically significant relationship with turnover intention. Single nurses were less likely to leave the NH (Park et al., 2009). Regarding experience, nurses with lower years of clinical experience had lower turnover intentions (Park et al., 2009), whereas years licensed, years of clinical experience, years of NH employment and years at current NH did not have a statistically significant relationship with turnover intention (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Park et al., 2009). Lower numbers of turnover experiences associated with lower RN turnover intentions (Park et al., 2009). Some demographic factors such as religion, job position, work type and possession of certification in geriatrics or gerontology did not associate with turnover intention (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Park et al., 2009).

Psychosocial factors

Job satisfaction is defined as “the favourable or unfavourable attitude the employees have toward their jobs” (Lum et al., 1998). In this review, all studies reported that high job satisfaction correlated with a low turnover intention of NH nurses (Chen et al., 2015; Filipova, 2011; Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010; Kuo et al., 2014; Park et al., 2009). Among them, Chen et al. (2015) examined job satisfaction by differentiating it into internal job satisfaction (i.e. satisfaction with factors inherent in their job) and external job satisfaction (i.e. satisfaction with factors that are external to the nature of their job) and reported that higher internal and external job satisfaction predicted the lower turnover intention. Job demand is seen as “the psychological stressors about work such as a heavy workload, insufficient time, and fast‐paced and difficult work” (Tuomi et al., 2016). Chen et al. (2015) indicated that low job demand associated with low turnover intention. In the same vein, nurses with low job stress had low turnover intentions (Park et al., 2009). However, Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al. (2010) reported that no statistically significant relationships exist between job stress and DONs' turnover intentions, and Kuo et al. (2014) reported that no statistically significant relationships exist between job stress and nurses' turnover intentions. Empowerment is defined as the “perception of level of freedom and control, psychological investment in and commitment to the job, and ability to influence organizational goals and processes.” Higher empowerment associated with lower DON turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010). Organizational commitment is defined as “one's general affective response toward the organization.” Negative correlations exist between organizational commitment and turnover intention (Filipova, 2011).

3.2.2. Organizational factors

Nursing home, nurse staffing and resident characteristics were recognized within organizational factors.

Nursing home characteristics

One study reported that the turnover intentions of nurses working at paid NHs is lower than that of nurses working at free NHs (Park et al., 2009). Two studies reported that DONs working at non‐profit NHs have lower turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010). Other factors, such as the number of beds and occupancy rate, did not have a statistically significant association with turnover intention.

Nurse staffing characteristics

Among the various nurse staffing characteristics, only RN HPRD significantly affected DONs' turnover intentions (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010). The higher the RN HPRD, the lower the turnover intention (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010). Other factors did not have a statistically significant association with turnover intention.

Resident characteristics

Regarding resident characteristics, Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al. (2010) reported that DON turnover intention was lower when the proportion of residents' Medicaid days was lower. Other factors did not have a statistically significant association with nurse‐turnover intention.

3.3. The degree of NH nurses' turnover intentions

Nursing home nurses' turnover intentions differed country to country and from study to study (see Table 2). The results of all studies should be interpreted carefully due to the wide variety of measurements used to measure turnover intention.

4. DISCUSSION

The literature review of nurses' turnover intentions was biased toward studying acute‐care settings. In this study, six studies of NH nurses' turnover intentions were reviewed and synthesized. A number of factors affecting nurses' turnover intentions were identified, including individual and organizational factors. This literature review also identified the degree of NH nurses' turnover intentions, which varied across studies.

According to this review, all studies identified job satisfaction as an individual factor related to nurses' turnover intentions. Therefore, strategies to improve NH nurses' job satisfaction is important to reduce their turnover intentions. Factors that determine nurses' job satisfaction vary. Among them, Kuo et al. (2014) reported that reducing overtime is a key strategy to decrease nurses' turnover intentions. The Taiwanese government recommends 40 hr of work per week, but nurses at a Taiwan NH work an average of 46.37 hr per week, which associates with a high turnover rate of Taiwan NH nurses (Kuo et al., 2014). A study of nurses at long‐term care hospitals in Japan found that nurses' overtime is a major factor that decreases nurses' intention to stay in their workplace (Eltaybani et al., 2018). Also, Farahani et al. (2016) reported that overtime is the main cause of turnover in Iranian hospital nurses. As such, the nurses' overtime is associated with poor health outcome for NH residents such as occurrence of pressure ulcers, catheter‐associated urinary tract infection and mortality (Antwi & Bowblis, 2018; Stone et al., 2007). It is also reported that nurses' overtime is related to the nurses' drowsy driving, overweight, fatigue, burnout, varicose vein and needlestick injuries (Barker and Nussbaum, 2011; Portela et al., 2005; Trinkoff et al., 2007) as well as nurse outcomes such as turnover intention and actual turnover, and appropriate nurses should be assigned to eradicate overtime work (Bae & Fabry, 2014; Stimpfel et al., 2012). NH administrators need to be aware of overtime's adverse outcome and establish overtime guidelines. Guidelines for eradicating overtime should specify personal and organizational efforts to reduce turnover, increase patients' health and establish a safe working environment. Also, it is needed to government‐level monitoring of compliance.

From an organizational perspective, nurse turnover in non‐profit NHs was lower than that of for‐profit NHs (Kash, Naufal, Cortés, et al., 2010; Kash, Naufal, Dagher, et al., 2010). Profit‐driven NHs struggle to minimize expenditures, which may lead to low nurse staffing and higher nurse‐turnover intentions (Kwon & Hong, 2015). Due to minimizing for‐profit NHs' expenditures, for‐profit NHs often have poor work environments and higher numbers of nurses dissatisfied with their jobs (White et al., 2020). Also, Bos et al. (2017) reported worse results with regard to nurse staffing well‐being and resident well‐being compared to non‐profit NHs. Modifying the work environment and increasing staffing levels could be costly to NHs; however, reduced turnover intentions and actual nurse turnover will likely save NH expenditures.

Nurse‐turnover intention can start as a withdrawal process. First, nurses leave their organization; then, they leave the profession entirely (Morrell, 2005). If NH administrators are able to stop this first step, NH nurses will not quit their professional jobs (Flinkman et al., 2010). Therefore, NH administrators must periodically investigate nurses' turnover intentions through a self‐report survey or by interviewing the nurses. They must also try to find the reasons why NH nurses have turnover intentions through in‐depth interviews with nurses. This review will help understand NH nurses' turnover intentions. As a result of the review, age, pay, marital status, clinical experience, position, job satisfaction, HPRD and profit/ non‐profit are related to turnover intention, administrators should take this into account to hire and manage nurses and create a working environment. Furthermore, it is necessary to provide an intervention programme related to these variables and to conduct studies on what changes occur in the nurses' turnover intention.

This review includes several limitations. First, although this review was based on an comprehensive search strategy, the limited number of included studies may limit the ability to explain the factors related to NH nurses' turnover intentions. Second, only the findings from previously published articles in English and Korean were extracted and used in this review. Therefore, future studies should include all studies published in different languages. Third, conclusions in this study are based only cross‐sectional design studies. Studies that applies various designs that can confirm causality needs to be conducted, and conclusions need to be made based on the results derived here.

5. CONCLUSION

This study reviewed and synthesized the findings of six studies. The reasons for NH nurses' turnover intentions are complicated. Various factors classified as individual and organizational factors can impact nurses' turnover intentions. Individual factors comprise demographic and psychosocial factors. Organizational factors comprise NH, nurse staffing and resident characteristics. Among the various factors above, this study found that job satisfaction was the most influential factor in nurses' turnover intentions. Therefore, efforts such as reducing overtime, increasing compensation and improving nurses' working environments are required to increase NH nurses' job satisfaction. This review of studies related to NH nurses' intentions to stay in their workplace found that study results can help healthcare professionals, administrative staff and policymakers establish strategies to decrease nurses' turnover intentions.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

None.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None.

Lee, J. (2022). Nursing home nurses' turnover intention: A systematic review. Nursing Open, 9, 22–29. 10.1002/nop2.1051

Funding information

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (2020R1I1A1A01066972)

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

REFERENCES

- Alexander, J. A. , Lichtenstein, R. , Oh, H. J. , & Ullman, E. (1998). A causal model of voluntary turnover among nursing personnel in long‐term psychiatric settings. Research in Nursing & Health, 21(5), 415–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antwi, Y. A. , & Bowblis, J. R. (2018). The impact of nurse turnover on quality of care and mortality in nursing homes: Evidence from the great recession. American Journal of Health Economics, 4(2), 131–163. 10.1162/ajhe_a_00096 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bae, S. H. , & Fabry, D. (2014). Assessing the relationships between nurse work hours/overtime and nurse and patient outcomes: Systematic literature review. Nursing Outlook, 62(2), 138–156. 10.1016/j.outlook.2013.10.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker, L. M. , & Nussbaum, M. A. (2011). Fatigue, performance and the work environment: A survey of registered nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 67(6), 1370–1382. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05597.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos, A. , Boselie, P. , & Trappenburg, M. (2017). Financial performance, employee well‐being, and client well‐being in for‐profit and not‐for‐profit nursing homes: A systematic review. Health Care Management Review, 42(4), 352–368. 10.1097/hmr.0000000000000121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle, N. G. , Engberg, J. , & Men, A. (2007). Nursing home staff turnover: Impact on nursing home compare quality measures. The Gerontologist, 47(5), 650–661. 10.1093/geront/47.5.650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, I. H. , Brown, R. , Bowers, B. J. , & Chang, W. Y. (2015). Job demand and job satisfaction in latent groups of turnover intention among licensed nurses in Taiwan nursing homes. Research in Nursing & Health, 38(5), 342–356. 10.1002/nur.21667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen‐Mansfield, J. (1997). Turnover among nursing home staff: A review. Nursing Management, 28(5), 59. 10.1097/00006247-199705010-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, H. (1998). Synthesizing research: A guide for literature reviews, 3rd edn. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Eltaybani, S. , Noguchi‐Watanabe, M. , Igarashi, A. , Saito, Y. , & Yamamoto‐Mitani, N. (2018). Factors related to intention to stay in the current workplace among long‐term care nurses: A nationwide survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 80, 118–127. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falatah, R. , & Salem, O. A. (2018). Nurse turnover in the kingdom of Saudi Arabia: An integrative review. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(6), 630–638. 10.1111/jonm.12603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farahani, M. A. , Oskouie, F. , & Ghaffari, F. (2016). Factors affecting nurse turnover in Iran: A qualitative study. Medical Journal of the Islamic Republic of Iran, 30, 356. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipova, A. A. (2011). Relationships among ethical climates, perceived organizational support, and intent‐to‐leave for licensed nurses in skilled nursing facilities. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30(1), 44–66. 10.1177/0733464809356546 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flinkman, M. , Leino‐Kilpi, H. , & Salanterä, S. (2010). Nurses’ intention to leave the profession: Integrative review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 66(7), 1422–1434. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05322.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffeth, R. W. , Hom, P. W. , & Gaertner, S. (2011). A meta‐analysis of antecedents and correlates of employee turnover: Update, moderator tests, and research implications for the next millennium. Journal of Management, 26(3), 463–488. 10.1016/S0149-2063(00)00043-X [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kash, B. A. , Naufal, G. S. , Cortés, L. , & Johnson, C. E. (2010). Exploring factors associated with turnover among registered nurse (RN) supervisors in nursing homes. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 29(1), 107–127. 10.1177/2F0733464809335243 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kash, B. A. , Naufal, G. S. , Dagher, R. K. , & Johnson, C. E. (2010). Individual factors associated with intentions to leave among directors of nursing in nursing homes. Health Care Management Review, 35(3), 246–255. 10.1097/hmr.0b013e3181dc826d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. K. , & Kim, M. J. (2011). A review of research on hospital nurses' turnover intention. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration, 17(4), 538–550. 10.11111/jkana.2011.17.4.538 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz, M. , Koslowsky, M. , Shalom, N. , & Elyakim, N. (1995). Predictors of intentions to leave the ward, the hospital, and the nursing profession: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(3), 277–288. 10.1002/job.4030160308 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo, H. T. , Lin, K. C. , & Li, I. C. (2014). The mediating effects of job satisfaction on turnover intention for long‐term care nurses in Taiwan. Journal of Nursing Management, 22(2), 225–233. 10.1111/jonm.12044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, H. , & Hong, K. (2015). The effect of publicness on the service quality in long‐term care facilities. Korean Journal of Social Welfare, 67(3), 253–280. 10.20970/kasw.2015.67.3.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lum, L. , Kervin, J. , Clark, K. , Reid, F. , & Sirola, W. (1998). Explaining nursing turnover intent: Job satisfaction, pay satisfaction, or organizational commitment? Journal of Organizational Behavior: The International Journal of Industrial, Occupational and Organizational Psychology and Behavior, 19(3), 305–320. [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D. , Liberati, A. , Tetzlaff, J. , Altman, D. G. & Prisma Group . (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell, K. (2005). Towards a typology of nursing turnover: The role of shocks in nurses’ decisions to leave. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 49(3), 315–322. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03290.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, Y. O. , Lee, K. J. , Cho, E. , & Park, H. J. (2009). Factors affecting turnover intention of nurses in long‐term care facilities for elderly people. Journal of Korean Gerontological Nursing, 11(1), 81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Portela, L. F. , Rotenberg, L. , & Waissmann, W. (2005). Health, sleep and lack of time: Relations to domestic and paid work in nurses. Revista De Saúde Pública, 39(5), 802–808. 10.1590/S0034-89102005000500016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin, J. H. , Choi, G. Y. , & Lee, J. (2020). Impact of nurse staffing, skill mix and stability on resident health outcomes in Korean nursing homes. Journal of Korean Gerontological Nursing, 22(4), 291–303. 10.17079/jkgn.2020.22.4.291 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stimpfel, A. W. , Sloane, D. M. , & Aiken, L. H. (2012). The longer the shifts for hospital nurses, the higher the levels of burnout and patient dissatisfaction. Health Affairs, 31(11), 2501–2509. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone, P. W. , Mooney‐Kane, C. , Larson, E. L. , Horan, T. , Glance, L. G. , Zwanziger, J. , & Dick, A. W. (2007). Nurse working conditions and patient safety outcomes. Medical Care, 571–578. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3180383667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, K. S. , Mor, V. , Tyler, D. A. , & Hyer, K. (2013). The relationships among licensed nurse turnover, retention, and rehospitalization of nursing home residents. The Gerontologist, 53(2), 211–221. 10.1093/geront/gns082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff, A. M. , Han, K. , Storr, C. L. , Lerner, N. , Johantgen, M. , & Gartrell, K. (2013). Turnover, staffing, skill mix, and resident outcomes in a national sample of US nursing homes. The Journal of Nursing Administration, 43(12), 630–636. 10.1097/nna.0000000000000004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkoff, A. M. , Le, R. , Geiger‐Brown, J. , & Lipscomb, J. (2007). Work schedule, needle use, and needlestick injuries among registered nurses. Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology, 28(2), 156–164. 10.1086/510785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomi, J. , Aimala, A. M. , & Žvanut, B. (2016). Nursing students' well‐being using the job‐demand‐control model: A longitudinal study. Nurse Education Today, 45, 193–198. 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uchida‐Nakakoji, M. , Stone, P. W. , Schmitt, S. , Phibbs, C. , & Wang, Y. C. (2016). Economic evaluation of registered nurse tenure on nursing home resident outcomes. Applied Nursing Research, 29, 89–95. 10.1016/j.apnr.2015.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vermeerbergen, L. , Van Hootegem, G. , & Benders, J. (2017). A comparison of working in small‐scale and large‐scale nursing homes: A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 67, 59–70. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, E. M. , Aiken, L. H. , Sloane, D. M. , & McHugh, M. D. (2020). Nursing home work environment, care quality, registered nurse burnout and job dissatisfaction. Geriatric Nursing, 41(2), 158–164. 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2019.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willemse, B. M. , Depla, M. F. I. A. , Smit, D. , & Pot, A. M. (2014). The relationship between small‐scale nursing home care for people with dementia and staff's perceived job characteristics. International Psychogeriatrics, 26(5), 805–816. 10.1017/s1041610214000015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). What is the decade of healthy ageing? Available online: https://www.who.int/initiatives/decade‐of‐healthy‐ageing Accessed on November 5, 2020. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.