Abstract

Aim

To clarify the concept of psychological safety in a healthcare context and to provide the first theoretical framework for improving interpersonal relationships in the workplace to better patient care.

Design

A Rodgers’ concept analysis.

Methods

The concept analysis was conducted using a systematic search strategy on PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Ichushi‐Web.

Results

An analysis of 88 articles studying psychological safety in health care identified five attributes: perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks, strong interpersonal relationships, group‐level phenomenon, safe work environment for taking interpersonal risks and non‐punitive culture. The antecedents included structure/system factors, interpersonal factors and individual factors. The four consequences included performance outcomes, organizational culture outcomes, and psychological and behavioural outcomes.

Keywords: concept analysis, health care, interpersonal risk, learning behaviour, patient safety, psychological safety, reporting error, speaking up

1. INTRODUCTION

Improving patient safety is a top priority in health care around the world (WHO, 2019). According to the World Health Organization (2019), providing an open and blame‐free safety culture around incident reporting is crucial for maintaining patient safety. Meanwhile, the Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (2017) advises that a focus on collective improvement and teamwork is also crucial for patient safety. Establishing a sense of psychological safety in the clinical environment fosters these elements, allowing nurses to more effectively ensure patient safety.

2. BACKGROUND

The concept of psychological safety has been discussed across various disciplines and industries such as aviation, education and manufacturing. Common definitions of psychological safety include ‘feeling able to show and employ one's self without fear of negative consequences to self‐image, status, or career’ (Kahn, 1990, p. 708) and ‘a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk‐taking’ (Edmondson, 1999, p. 354). This concept's application has spread to the healthcare discipline since it is known to yield positive healthcare outcomes. Recent studies in health care have demonstrated that psychological safety influences patient safety, interprofessional collaboration, engagement in quality improvement work, learning from failures and reporting adverse events (Arnetz, Sudan, Goetz, Counts, & Arnetzet al., 2019; Greene et al., 2020; Hirak et al., 2012; O'Leary, 2016; Tucker et al., 2007). Thus, psychological safety is considered a critical factor to account for in projects that seek to better health care, including those interested in high‐quality nursing, effective teamwork and patient safety.

Although research on psychological safety has increased in the healthcare field, its definition in this context remains unclear. A concept taken from other domains should be critically considered about its utility and importance in a new domain (Meleis, 2017). However, little research has discussed psychological safety in a theoretical sense. For example, one study has described psychological safety using the same concept as trust (Kang et al., 2020); others have described psychological safety as a speaking‐up‐related climate, part of justice culture, or feeling of safety around innovation (Appelbaum et al., 2018; Schwappach et al., 2018; Zuber & Moody, 2018). The lack of theoretical underpinning may hinder the advancement in healthcare management in terms of ensuring a conducive environment for high‐quality care. Furthermore, few specific tools measure psychological safety in a healthcare context (O’Donovan et al., 2020). For example, Edmondson (1999) developed a scale to measure psychological safety in a general context including health care; meanwhile, Richard et al. (2017) developed a questionnaire measuring aspects such as psychological safety that influence speaking‐up behaviour among healthcare staff about patient safety concerns. Nonetheless, the lack of statistically rigorous measurements of psychological safety, specifically in the context of health care (O’Donovan et al., 2020), prevents the exploration of its antecedents and implications for healthcare management.

2.1. Research question

A concept analysis can clarify the structures of a concept and its relationships to other concepts. It also highlights implications for future scale development and clinical practices. Rodgers (2000) developed a concept analysis approach to describe a concept that changes in a context, allowing for its development and further research. Thus, this study aimed to identify the concept of psychological safety in a healthcare context through a Rodgers’ concept analysis and provide the first theoretical foundations for how such an understanding may better interpersonal relationships and patient care. Therefore, our research question was What are the attributes, antecedents and consequences of psychological safety in the context of health care?

3. THE STUDY

3.1. Design

This study used Rodgers’ evolutionary approach. Rodgers’ approach aims to capture changing and evolving concepts over time and develop a concept for further research and clinical practice. It includes the following six steps to analyse a concept: (1) identifying the concept of interest and associated expressions; (2) identifying and selecting an appropriate realm (setting and sample) for data collection; (3) collecting data relevant to identify the attributes of the concept, the antecedents, consequences and related concepts; (4) analysing the data in terms of the above characteristics of the concept; (5) identifying an exemplar of the concept, if appropriate; and (6) identifying implications, hypotheses and implications for further development of the concept (Rodgers, 2000, p.85).

3.2. Method

This concept analysis was conducted using a systematic search strategy on PubMed, CINAHL, PsycINFO and Ichushi‐Web, with no publication date limitation. Keywords used were as follows: “psychological safety [AB]” was used in PubMed, CINAHL and Ichushi‐Web; “psychological safety [AB]” AND (health care OR doctor OR physician OR nurs* OR hospital OR medic*) were used in PsycINFO. This study was undertaken in April 2020.

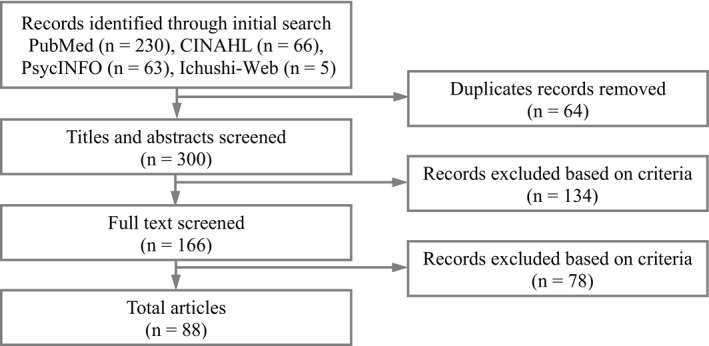

The search yielded 300 articles after removing duplicates. Articles that met the following inclusion criteria were selected: (1) focused on concepts of psychological safety, (2) conducted in health care, (3) employees completed a survey, (4) were not literature review articles, (5) was an empirical study, (6) not duplicated among databases and (7) other reasons, such as written in English and Japanese and availability of the full text. Two reviewers scanned the titles and abstracts of the articles. As shown in Figure 1, this procedure excluded 134 articles. Additionally, 78 articles were excluded through the full‐text scanning by the reviewers. Finally, this systematic strategy led to 88 articles. The PRISMA guideline was used for this concept analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of article selection

3.3. Analysis

As described by Rodgers (2000), a thematic analysis was conducted to identify the concept, and descriptions of attributes, antecedents and consequences were selected from each article. According to Rodgers’ approach, attributes constitute a real definition, an antecedent is a phenomenon before an instance of the concept, and a consequence is a result of the concept (Rodgers, 2000). The findings from the articles were put into the matrix sheet. Subsequently, they were categorized and organized the descriptions according to their similarities and trends. Finally, we again grouped the categories made to increase the level of abstraction. This analysis process was repeated until four researchers agreed on the whole process of categorizations and abstractions.

3.4. Ethics

We declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript. This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP19H03920. Furthermore, this concept analysis was not needed the Research Ethics Committee approval and the patient consent because our study analysed only published articles.

4. RESULTS

4.1. Overview of contexts and results

Table A1 in the Appendix lists the 88 articles analysed in this study. Of these 88 articles, 60 were published between 2016 and 2020. Fifty‐one articles cited definitions of psychological safety by Edmondson (1999). Fifty‐eight articles used instruments to measure psychological safety, of which 35 (60.3%) used self‐report measurements developed by Edmondson (1999). Additionally, 47 of the included articles were studies conducted in Northern America (United States: n = 47; Canada: n = 1), 26 in Europe (Western: n = 16; Northern: n = 9; Southern: n = 1) and 8 in Asia (Western: n = 4; Eastern: n = 2; Southeastern: n = 1; and Southern: n = 1).

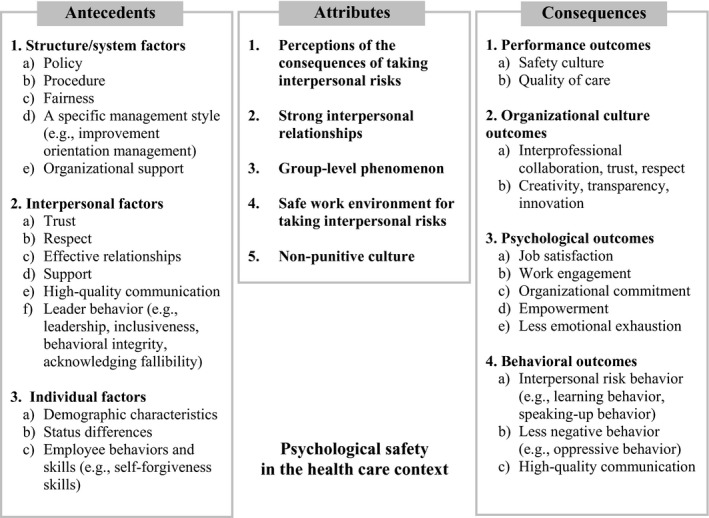

This concept analysis identified five attributes, three antecedents and four consequences. Figure 2 illustrates the conceptual model of psychological safety in the healthcare context based on the findings of this analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual model of psychological safety in the health care context

4.2. Attributes

4.2.1. Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks

The concept analysis found that psychological safety captured perceptions of the consequences of interpersonal risk behaviours in the work environment. Interpersonal risk behaviour has often caused team members to be labelled ignorant, incompetent and disturbers in work environments, including behaviours such as asking questions, reporting errors and bringing up concerns (Edmondson, 2019). For example, MacCurtain et al. (2018) described psychological safety as when employees feel safe voicing concerns and reporting problems and can trust their supervisor.

4.2.2. Strong interpersonal relationships

This attribute included a description of strong interpersonal relationships, such as trust and respect. For example, Albritton et al. (2019) described that a high level of psychological safety reflected a team climate of interpersonal trust and mutual respect.

4.2.3. Group‐level phenomenon

This attribute suggested that psychological safety was a group‐level phenomenon, although the first and second themes described psychological safety as an individual‐level concept, including individuals’ perceptions and feelings. Lee, Yang, and Chen (2016) described psychological safety as a shared belief among groups that facilitated the acceptability of behavioural risks.

4.2.4. Safe work environment for taking interpersonal risks

The concept analysis found that psychological safety concerns in the work environment were linked to interpersonal risk behaviours. Noah and Steve (2012) stated that the organizational work environment includes systems, procedures, practices, values and philosophies. Singer et al. (2015) identified psychological safety as a cultivated environment safe for interpersonal risk‐taking. Based on the definition of the work environment, the concept of psychological safety concerns the structure dimension in an organization that facilitates interpersonal risk.

4.2.5. Non‐punitive culture

Psychological safety was recognized as an organizational culture where team members were not punished or blamed even if they took interpersonal risks. According to previous studies, organizational culture is a wider concept than that of the work environment described in the previous category in this paper. Allaire and Firsirotu (1984) argued that organizational culture comprises three components: the structure of an organization; a cultural system including an organization's myths, ideology and values; and individual factors including employees’ experiences, personalities and cognitions. Lee et al. (2016) stated that teams possessed a common belief and a non‐punitive culture that accepted the risk of reporting behaviours when team members perceived psychological safety.

4.3. Antecedents

4.3.1. The structure/system factor

This theme included policy and procedures, fairness, organizational support and a specific management style. As an example of management style, Halbesleben and Rathert (2008) reported that an improvement orientation management style was a predictor of psychological safety.

4.3.2. Interpersonal factors

Interpersonal factors were identified as antecedents of psychological safety, including trust, respect, effective relationships, support, high‐quality communication and leader behaviour. Effective relationships involved interpersonal relationships among work teams, such as collegial teamwork and familiarity in the team. This analysis distinguishes support in this theme from organizational support described in the previous category. Support in this theme is particularly concerned with interpersonal support among team members in a work environment. Examples include support from leaders, team members and peers.

Additionally, high‐quality communication fosters psychological safety. High‐quality communication for psychological safety has the following features: frequent, open and honest communication.

Furthermore, this analysis found that leader behaviour was a prerequisite for psychological safety. Leader behaviour as an antecedent comprises leadership, inclusiveness, behavioural integrity and acknowledging employees’ fallibility. Various types of leadership were positively related to psychological safety, although there were mixed results among the selected articles. For instance, transformational leadership predicted psychological safety (Raes et al., 2013). A leader's inclusiveness, described as a leader's words and deeds that invite and appreciate others’ contributions (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006), facilitated psychological safety. Furthermore, behavioural integrity, defined as the perception of alignment between a leader's words and deeds (Simons, 2002), promoted psychological safety.

4.3.3. Individual factors

Individual factors included demographic characteristics, status differences and employees’ behaviours and skills.

Demographic characteristics were associated with psychological safety. For example, age was negatively related to psychological safety (Buljac‐Samardžić et al., 2018). Moreover, minorities perceive lower psychological safety than that of white employees (Derickson et al., 2015). Differences in status levels also influenced psychological safety. This analysis identified two types of status differences as antecedents. First, there were status differences in disciplines; for example, residents generally had lower status than physicians. Residents’ perceptions of power distance were related to psychological safety (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Second, status differences among disciplines were also antecedents. For instance, about psychological safety, physicians felt more than nurses, and nurses felt more than respiratory therapists in a neonatal intensive care unit (Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006).

Finally, employee behaviours and skills were identified as antecedents. Less incivility and more self‐forgiveness skills were associated with greater feelings of psychological safety.

4.4. Consequences

4.4.1. Performance outcomes

Psychological safety influenced safety culture in a team and quality of care, including patient safety, effective rescue, patient‐centred care, patient satisfaction and transition to professional practice.

4.4.2. Organizational culture outcomes

This theme of consequences included dimensions of interpersonal relationships and the culture/work environment. The analysis revealed that psychological safety facilitated interpersonal relationships such as interprofessional collaboration, teamwork and trust. Additionally, psychological safety influenced the dimensions of culture and work environment in a healthcare organization. Creativity, transparency and innovation appeared in work environments with high psychological safety. Furthermore, psychological safety created a climate of organizational learning.

4.4.3. Psychological outcomes

Psychological safety influenced healthcare providers’ psychological outcomes. Specifically, psychological safety enhanced job satisfaction, work engagement, organizational commitment and empowerment and led to less emotional exhaustion and stress. Additionally, psychological safety encouraged healthcare providers to engage in quality improvement work.

4.4.4. Behavioural outcomes

Finally, this analysis identified the dimensions of healthcare workers’ behavioural outcomes as consequences of psychological safety.

A high level of psychological safety allows healthcare workers to engage in interpersonal risk behaviours. Interpersonal risk behaviours include learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour, giving and seeking feedback, error‐seeking behaviour, extra‐role behaviour and implementation of new practices. Learning behaviour allows a team to obtain and process data that facilitates a team to adapt and improve (Edmondson, 1999). Furthermore, psychological safety engendered speaking‐up behaviour. Speaking‐up behaviour was referred to as an open statement of views or opinions about workplace matters (Premeaux & Bedeian, 2003). Specifically, reporting errors, suggesting ideas, bringing up concerns, asking questions, asking for help and sharing knowledge were identified as positive outcomes of psychological safety in health care.

Furthermore, high‐quality communication was built when healthcare providers felt psychological safety. In contrast, lack of psychological safety was associated with negative behaviours. For instance, the absence of psychological safety increased oppressive behaviour, disruptive behaviour, workarounds and bullying.

4.5. Model case

A new graduate nurse makes a mistake. At first, she/he is afraid to report the mistake, but the fear eventually disappears.

The psychologically safe unit allows the graduate nurse to report the mistake to the nurse manager. The unit has a policy of fostering a culture that does not punish others for reporting errors. The manager in the unit has implemented this policy by her/his words and deeds to keep her/his integrity. Moreover, the new graduate nurses have received support from other nurses in the unit. The policy and supportive relationships help the new nurses feel safe in reporting errors in the unit. In addition, the unit with high psychological safety influences their psychological and performance dimension. The new graduate nurses could engage in their work in the psychologically safe unit and transition successfully into professional practice.

This exemplar demonstrates the attributes, antecedents and consequences of psychological safety in a healthcare team, with a high level of it identified in this concept analysis. It can help nurse managers and researchers understand the concept of psychological safety in a clinical situation.

5. DISCUSSION

Our concept analysis identified the attributes, antecedents and consequences of psychological safety in a healthcare context. The concept of psychological safety is a multilevel phenomenon related to a unit culture that facilitates interpersonal risk behaviour. This study demonstrated that psychological safety in a healthcare work environment influenced proactive behaviours, such as asking questions, reporting errors and communicating openly. Additionally, psychological safety proved to be associated with strong interpersonal relationships and an effective culture that includes collaboration, trust and innovation, which ensure patient safety.

Many of the included articles were published in the past five years, suggesting that the concept of psychological safety in health care is still developing. More than half of the articles cited the definition or measurement developed by Edmondson (1999). This finding suggests that Edmondson's work has been instrumental in stimulating research on psychological safety in the healthcare field. Mounting research has yielded attributes of psychological safety that are unique to health care and demonstrated that antecedents and consequences reflect the context (in this case, health care).

We found five themes related to attributes. The theme of a group‐level phenomenon was considered an attribute specific to health care. This is in line with a previous study comparing the characteristics of healthcare and educational settings (Edmondson et al., 2016), which concluded that psychological safety as a group phenomenon was unique to the healthcare environment. In the educational context, differences in the perception of psychological safety existed between elementary and high schools. Centrally, in the healthcare context, differences in perception exist in a hospital; that is, there were differences between units, such as between surgical and medical units.

However, this analysis identified psychological safety as an individual‐level phenomenon, including themes of the perception of interpersonal risk and strong interpersonal relationships. Therefore, our findings suggest that psychological safety has both group and individual dimensions. We considered this finding to be complementary rather than contradictory. The theory of organizational culture (Allaire & Firsirotu, 1984) explains this complex characteristic of psychological safety. According to this theory, organizational culture consists of interpretations of what members experience in the group; in other words, a feeling of psychological safety among members is a prerequisite for building a culture of psychological safety in teams.

We also identified three antecedent themes (structure/system factors, interpersonal factors and individual factors). Specifically, the findings suggest that the theme of status differences was a unique antecedent in the healthcare context. A systematic review (Newman et al., 2017) analysing articles without limitations on disciplines had similarly identified status differences as an antecedent. Notably, this study found two types of status differences in the context of health care—in a discipline and among disciplines. Moreover, our findings indicated that, to establish psychological safety in healthcare organizations, it is necessary to reduce status gaps both in and among disciplines.

Four themes were identified as consequences of psychological safety. The theme of implementing new practices reflected the contextual characteristics of health care. As diseases and evidence‐based care evolve and new equipment and skills are periodically developed, healthcare providers must constantly try to implement new practices. Therefore, our results suggested that additional studies to examine the relationship between psychological safety and implementation of new practices are necessary to promote high performance in the healthcare environment. Furthermore, we found complex themes that were identified as both antecedents and consequences, including trust, interpersonal support and high‐quality communication. This finding implied that some of the antecedents and consequences of psychological safety influenced each other.

Our concept analysis has implications for further research. First, we recommend that further research develop a measurement including specific items that reflect the context of health care. Many of the selected articles used the measurement developed by Edmondson (1999). This measurement captures psychological safety in the general context and is composed of a single factor. An additional measurement that captures psychological safety in the context of health care reflecting the attributes found in this study is needed to obtain detailed suggestions for nursing managers. Therefore, the themes of attributes, antecedents and consequences in this analysis may help develop a new measurement tool. New measurements could also facilitate empirical studies that would establish a team culture of psychological safety.

Second, we recommend examining whether psychological safety is affected by national culture. Only a few articles conducted in Eastern cultures were selected, although this analysis used both English and Japanese databases. Newman et al. (2017) stated that national culture influences psychological safety. For instance, team members in a work environment in Western cultures perceive more psychological safety than those in Eastern cultures, as Western cultures are generally characterized by a low level of collectivism; thus, speaking‐up behaviour is considered to have minimal social cost. However, previous studies concluded that little is known about how psychological safety is influenced by differences in culture (Newman et al., 2017). Therefore, additional research in the healthcare field needs to be conducted in various countries to clarify cultural influences.

5.1. Limitations

Two limitations to this concept analysis were identified. First, the inclusion criteria for articles may have resulted in bias: This analysis included articles that referred to ‘psychological safety’ in the abstract; moreover, we excluded grey literature or articles written in languages other than English and Japanese. Therefore, we could have missed relevant articles. Second, this analysis used the search term “psychological safety,” which may have caused us to miss articles that expressed “psychological safety” using different terms. However, to minimize bias, we checked the surrogate terms of psychological safety and discussed the validity of the search term before conducting the search strategy.

5.2. Conclusion

This study demonstrated that psychological safety in a healthcare work environment influences proactive behaviours such as asking questions, reporting errors and open communication. Additionally, psychological safety is associated with strong interpersonal relationships and an effective culture that includes collaboration, trust and innovation, which ensure patient safety.

In clinical environments, nurse managers serve an important role in cultivating a constructive work environment. Nurse managers’ roles include improving quality and performance and encouraging collaboration among interprofessional staff and nurses. Our findings offer insights to help nurse managers enhance psychological safety in the workplace. First, nurse managers can build a unit with psychological safety through a set of procedures while adopting consistency, bias‐suppression, accuracy, correctability, representativeness and ethicality rules (Leventhal, 1980). Nurse managers consider these rules when making decisions, which allows them to achieve high‐quality care through psychological safety.

Second, nurse managers can build interpersonal relationships with high psychological safety through leadership behaviours consisting of inclusiveness and/or high‐quality communication. Specially, we recommend that nurse managers encourage staff nurses’ contributions to their unit and openly and frequently communicate with nurses and interprofessional staff. Nurse managers can use these behaviours to establish psychologically safe relationships that allow staff nurses to ask questions and provide better care with interprofessional collaboration.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Ayano Ito involved in design, data collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting the manuscript. Kana Sato involved in design, data collection and drafting the manuscript. Yoshie Yumoto and Miki Sasaki involved in interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript. Yasuko Ogata involved in design, interpretation of data and drafting the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We would like to thank the support of Japan Society for Promotion Science (JSPS).

1.

TABLE A1.

List of included articles

| No. | Authors | Purposes of study | Attribute | Antecedent | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Agius et al. (2008), United Kingdom | To explore primary educators’ perceptions on modern process consultants at hospitals and the impacts of modernization on their roles | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work |

| 2 | Albritton et al. (2019), Ghana | To analyse the relationships between psychological safety, learning behaviour and quality improvement implementation | Strong interpersonal relationship | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Support, creativity Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 3 | Alingh et al. (2019), Netherlands | To explore the relationships between specific management styles, safety climate, psychological safety and speaking‐up behaviour | ‐ |

Structure/system factor— Commitment‐based safety management Interpersonal factor— Leader behaviour |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour, bringing up concerns, high‐quality communication, learning behaviour |

| 4 | Appelbaum et al. (2018), United States | To establish the validity of two instruments that assess the learning environment perceptions in the clinical environment | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 5 | Appelbaum et al. (2016), United States | To explore relationships between power distance and inclusiveness on psychological safety and reporting behaviour | ‐ |

Structure/system factor— Policy, Procedure Interpersonal factor— Inclusiveness Individual factor— Status differences, less fear of being ignorant, incompetent, disruptive |

Performance outcome— High patient safety Behavioural outcome— Reporting errors, intention to report adverse events |

| 6 | Arnetz et al. (2019), United States | To identify organizational determinants of bullying and the resulting work disengagement among nurses | Strong interpersonal relationship | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Work engagement Behavioural outcome— Reporting adverse events, less bullying |

| 7 | Arnetz et al. (2019), United States | To examine associations between work environment, specific stress biomarkers and patient outcomes about the quality of nurse care | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Psychological outcome— Work engagement, less stress Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting errors, less bullying |

| 8 | Baik and Zierler (2019), United States | To explore experiences and perceptions about team intervention, including the Team Strategies and Tool to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety (STEPPS)® training and the structured interdisciplinary bedside rounds (SIBR) process | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Bringing up concerns, asking questions, sharing information |

| 9 | Barling et al. (2018), Canada | To examine the effects of various leadership behaviours by surgeons on team performance | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor — Transformational leadership, coaching, less abusive supervision |

Behavioural outcome— Implementation of new practices, bullying |

| 10 | Basit (2017), Malaysia | To examine the mediator roles of psychological safety and feelings of obligation between trust in supervisors and job engagement | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks |

Interpersonal factor — Effective relationship, support from leader, trust (leader–member) |

Psychological outcome— Work engagement, obligation feeling Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, asking questions |

| 11 | Bindels et al. (2018), Netherlands | To explore how physicians conceptualize and experience reflection in their professional practice | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome— high patient safety Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 12 | Bradley et al. (2017), United States | To develop a scale for assessing organizational culture about efforts to reduce mortality in hospitals and assess the validity and reliability of the scale | Group‐level phenomenon | ‐ | ‐ |

| 13 | Brown and McCormack (2011), Northern Ireland | To explore the factors that enhanced pain management practices for older people | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome — Person‐centred care |

| 14 | Brown and McCormack (2016), Northern Ireland | To explore the facilitators that allowed the healthcare team to analyse their practice and enhance quality of care | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor – Effective relationship, leadership, support, respect |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, less oppressive behaviour |

| 15 | Buljac‐Samardžić et al. (2018), Netherlands | To analyse the relationship between psychological safety, psychological detachment and patient safety | ‐ |

Individual factor— Gender, age |

Organizational culture outcome— Support Psychological outcome— Work engagement, more psychological detachment Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour, sharing knowledge, reporting errors, feedback behaviour, extra‐role behaviour |

| 16 | Carmeli and Zisu (2009), Israel | To explore the relationships between organizational trust, perceived organizational support, psychological safety and internal auditing | Group‐level phenomenon |

Structure/system factor— Support from organization Interpersonal factor— Trust |

Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting errors, feedback behaviour |

| 17 | Clark et al. (2014), United States | To investigate the influence of role definition as moderator between safety climate and organizational citizenship behaviour among nurses | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 18 | Colet et al. (2018), Saudi Arabia | To investigate nurses’ perceptions of climate for preventing infections and explore its predictors | ‐ |

Individual factor— Nationality, clinical experience |

‐ |

| 19 | Cuellar et al. (2018), United States | To investigate the influence of various practice ownerships on work environment, culture of learning behaviour, psychological safety and burnout | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 20 | Curry et al. (2018), EU countries | To explore the influence of organizational culture and improve hospital performance on care by implementing an intervention | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment, supportive relationships, power‐sharing Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 21 | Curşeu (2013), Netherlands | To explore the relationships between diversity in team, communication, trust, psychological safety and learning behaviour | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Frequency of communication |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour |

| 22 | De Brún and McAuliffe (2020), Ireland | To theoretically understand the contextual conditions and mechanisms to promote collective leadership and the outcomes | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Frequency of communication, open communication |

Performance outcome— Patient satisfaction, safety culture Organizational culture outcome— Effective teamwork, power‐sharing, conflict management Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction, engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Sharing knowledge |

| 23 | Derickson et al. (2015), United States | To explore the relationship between psychological safety and the willingness to report errors | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Inclusiveness Individual factor— Race, status difference |

Behavioural outcome—s Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour, reporting errors |

| 24 | Edmondson et al. (2001), United States | To examine the relationship between psychological safety, collective learning and implementation of new routines | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Leader behaviour |

Organizational culture outcome— Coordination Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour, implementation of new practices |

| 25 | Edmondson et al. (2016), United States | To compare and understand the characteristics of psychological safety in 26 healthcare and education organizations | Group‐level phenomenon |

Interpersonal factor— Inclusiveness, acknowledgement of mistakes and fallibility, acceptance, support from leader, respect Individual factor— Status difference |

Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, asking for help |

| 26 | Erichsen Andersson et al. (2018), Sweden | To examine the process of a knowledge translation intervention to improve hand hygiene and aseptic techniques | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome – Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome – Learning behaviour, implementation of new practices, less disruptive behaviours |

| 27 | George, Elwy et al. (2020), United States | To explore the relationship between the perceptions of organizational culture and adverse events | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome— Safety culture Psychological outcome— Work engagement Behavioural outcome— Bringing up concerns |

| 28 | George, Parker et al. (2020), United States | To describe and compare the approaches used to select safety priorities | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Behavioural outcome— Bringing up concerns |

| 29 | Gilmartin et al. (2019), United States | To describe the intervention for quality improvement experience and evaluate the effectiveness | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour, suggesting ideas |

| 30 | Gilmartin et al. (2018), United States | To explore the relationship between perceptions of psychological safety and reports of non‐adherence to the central line insertion checklist at the unit level | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting errors, suggesting ideas |

| 31 | Gong et al. (2019), China | To explore the relationships between psychological safety, ethical leadership, feedback seeking and the effect of power distance | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Ethical leadership Individual factor— Power distance |

Behavioural outcome— Feedback behaviour |

| 32 | Grant et al. (2014), Unites States | To measure emotional exhaustion, self‐verification, psychological safety and external rapport in surveys before and after the interventions | ‐ |

Individual factor— Self‐reflective titles |

Psychological outcome— Less emotional exhaustion Behavioural outcome— Asking for help, expressing oneself |

| 33 | Greene et al. (2020), United States | To examine relationships between psychological safety and practices to prevent specific infections | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome— Patient safety, safety culture Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 34 | Halbesleben and Rathert (2008), United States | To examine the relationship between climate for continuous quality improvement, psychological safety and workarounds | Group‐level phenomenon |

Structure/system factor— Organizational/team structure, improvement orientation management, support from organization Interpersonal factor— High‐quality communication, behavioural integrity, support from leader, trust (leader–member, member–member), respect |

Performance outcome— Patient safety Behavioural outcome— Fewer workarounds |

| 35 | Halbesleben et al. (2013), United States | To examine the relationships between psychological safety, behavioural integrity, safety compliance and occupational injuries | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor — Trust |

Performance outcome — Safety culture Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting behaviours |

| 36 | Hesselgreaves and MacVicar (2012), Scotland | To explore trainees’ perspectives to understand the impact of practice‐based small‐group learning on curriculum needs, preparation for independent practice and facilitator learning | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 37 | Hirak et al. (2012), Israel | To analyse the relationship between leader inclusiveness, members’ perceptions of psychological safety, learning from failures and unit performance | ‐ |

Structure/system factor— Support from organization Interpersonal factor — Inclusiveness, acknowledgement of mistakes and fallibility, accessibility to leader, openness |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, suggesting ideas, bringing up concerns, expressing oneself |

| 38 | Huddleston and Gray (2016), United States | To explore nurses’ perceptions of a healthy Work environment setting and define the characteristics of a healthy work environment | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 39 | Jain et al. (2016), United States |

To explore the role of psychological safety as a key factor to improve team communication |

‐ |

Structure/system factor— Geographic dispersion Interpersonal factor— Familiarity, leader behaviour, status difference |

Organizational culture outcome— Collaboration, effective teamwork Behavioural outcome— Suggesting ideas, sharing knowledge, open communication |

| 40 | Kang et al. (2020), Unites States | To examine the relationships between employee engagement, patient satisfaction and various organizational culture characteristics, including psychological safety, fairness and innovation | Group‐level phenomenon |

Structure/system factor— Fairness |

Performance outcome— Patient satisfaction Psychological outcome— Work engagement, positive emotion, empowerment |

| 41 | Keitz et al. (2019), United States | To examine the influence of clinical learning experiences on career choices and considerations about future employment | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction, engagement in improvement work, less turnover intention Behavioural outcome Reporting errors |

| 42 | Kessel et al. (2012), German | To examine the impact of psychological safety on the process of sharing knowledge and creative performance in teams | Group‐level phenomenon, strong interpersonal relationships | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour, sharing knowledge, frequent communication |

| 43 | Klingberg et al. (2018), Switzerland | To estimate the influence of incivility on psychological safety among physicians in an emergency department | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Less incivility |

Organizational culture outcome— Innovation Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 44 | Kolbe et al. (2013), Switzerland | To develop a debriefing approach for simulation training and demonstrate its effectiveness | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 45 | Lazzara et al. (2015), United States | To examine the effect of telemedicine on team attitudes, behaviours, cognitions and climates | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 46 | Lee et al. (2016), United Kingdom, Taiwan | To examine the factors that allowed nurses to report incidents | Non‐punitive culture, group‐level phenomenon | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, reporting incidents, intention to report incidents, suggesting ideas, intention to ask questions, intention to discuss incidents |

| 47 | Leroy et al. (2012), Belgium | To understand the influence of leader integrity on safety climate and patient safety outcomes | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Reporting errors |

| 48 | Lyman, Ethington et al. (2017), United States | To describe the process to reach excellent clinical performance in a team and examine the relationship between psychological safety and organizational learning | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Support Psychological outcome — Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, reporting hazardous situations |

| 49 | Lyman, Shaw et al. (2017), United States | To discover new insights about organizational learning in hospital units | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Ethical leadership, change‐oriented leadership, inclusiveness, trust (leader–member) |

Psychological outcome — Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 50 | Lyman et al. (2020), United States | To describe the experiences on psychological safety perceived by new graduate Registered Nurses | Group‐level phenomenon |

Structure/system factor— Spending time, supportive system Interpersonal factor— Effective relationship, support from leader, support from members, trust |

Performance outcome— Transition to professional practice Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Psychological outcome — Work environment, commitment to patient safety Behavioural outcome— Speaking up about problems, sharing ideas |

| 51 | MacCurtain et al. (2018), Ireland | To examine the relationships between a bystander's perception of psychological safety and their response to witnessing bullying | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks, group‐level phenomenon, strong interpersonal relationships | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Reporting problems, bringing up concerns, less bullying |

| 52 | Martland, et al. (2016), Australia | To explore the communication process between clinicians that facilitated the activation of rapid response teams | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour |

|

| 53 | MacCurtain et al. (2018), United States | To describe the experiences of psychological safety and explore the factors to build a psychological safety climate | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 54 | Nembhard and Edmondson (2006), United States | To examine the relationship between professional status, leader inclusiveness, psychological safety in teams and engagement in quality improvement | Group‐level phenomenon |

Interpersonal factor — Leadership, inclusiveness Individual factor— Status differences among disciplines, experience year |

Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, implementation of new practices |

| 55 | O'Leary (2016)Ireland | To explore the influence of psychological safety on the development of interdisciplinary teams | Non‐punitive culture |

Interpersonal factor — Inclusiveness, acknowledgement of mistakes and fallibility, empowerment, respect |

Organizational culture outcome— Collaboration, effective teamwork Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, asking questions, sharing knowledge, effective discussion |

| 56 | Ortega et al. (2013), Spain | To examine the relationship between team learning and performance and team beliefs about the interpersonal context, including psychological safety, task interdependence and potency | Group‐level phenomenon | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting errors |

| 57 | Pannick et al. (2017), United Kingdom | To examine the impact of an intervention for identifying clinical challenges and planning to resolve them | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 58 | Pogorzelska‐Maziarz et al. (2016), United States | To examine the validity of a psychometric tool to measure the organizational climate and prevent infections | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 59 | Prestia et al. (2017), United States | To describe nurses’ experiences with moral distress | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome– Interpersonal risk behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour |

| 60 | Prottas and Nummelin (2018), United Status | To explore the relationships between the perceptions of a manager's belief in Theory X or Y, psychological safety, organizational citizenship behaviour, quality of care, patient satisfaction and the employing entity | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome– Creativity Behavioural outcome– Learning behaviour, sharing knowledge, organizational citizenship behaviour |

| 61 | Raes et al. (2013), Belgium | To explore when and how teams engage in team learning behaviours | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Leader behaviour, transformational leadership |

Organizational culture outcome— Conflict management Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour |

| 62 | Rahmati and Poormirzaei (2018), Iran | To predict nurses’ psychological safety by considering forgiveness dimensions | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks |

Individual factor— Self‐forgiveness |

Psychological outcome— Forgiveness Behavioural outcome— Reporting errors, suggesting ideas |

| 63 | Ramana Feeser et al. (2019), United States | To examine the relationship between organizational support and psychological safety and explore the factors associated with the perception of the learning environment | Group‐level phenomenon |

Individual factor— Status difference |

Organizational culture outcome— Collaboration, creativity Psychological outcome— Engagement in improvement work, commitment, positive emotion Behavioural outcome— Suggesting ideas, asking for help. Feedback behaviour, admitting mistakes |

| 64 | Rathert et al. (2009), United States | To explore a theoretical framework of the work environment for continuous quality improvement and examine the relationships between the work environment, psychological safety, organizational commitment, engagement and patient safety | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome— Patient safety, patient‐centred care Psychological outcome— Satisfaction, work engagement, engagement in improvement work, organizational commitment Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, fewer workarounds |

| 65 | Richard et al. (2017), Switzerland | To develop a questionnaire to assess speaking‐up behaviour about patient safety | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Engagement in learning Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour, bringing up concerns, feedback behaviour |

| 66 | Scheepers, et al. (2018), Netherlands | To investigate the relationship between perceptions of psychological safety and the feedback on performance received from peers | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Peer support, trust |

Performance outcome— Safety culture Organizational culture outcome— Trust Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction, engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, reporting adverse events, bringing up concerns, sharing knowledge, feedback behaviour |

| 67 | Schulze et al. (2016), Switzerland | To develop and evaluate a training programme including an airway algorithm for pulmonologists using non‐anaesthesiologist administered propofol sedation | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 68 | Schwappach and Gehring (2015), United States | To examine the impact of practice ownership on the work environment, a climate of learning, psychological safety and burnout | ‐ | ‐ | ‐ |

| 69 | Schwappach and Niederhauser (2019), Switzerland | To examine speaking‐up‐related behaviour and climate for the first time in psychiatric hospitals | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 70 | Schwappach and Richard (2018), Switzerland | To examine the frequencies of speaking‐up behaviours and the relationship between safety climate and speaking‐up behaviours and withholding voice behaviours | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective teamwork Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 71 | Schwappach et al. (2018), Austria | To examine the speaking‐up behaviour and psychological safety as a safety climate | ‐ |

Individual factor— Status differences among disciplines |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 72 | Shea et al. (2018), Australia | To examine the associations with workplace type, strategies for occupational violence and aggression, and support after incidents | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Support |

| 73 | Sholomovich and Magnezi (2017), Israel | To examine the correlation between the psychological safety of an organization's nursing staff and its sense of personal responsibility for avoiding transmission of infections | ‐ |

Structure/system factor Support from organization Individual factor— Status differences among disciplines |

Performance outcome— Safety culture Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, learning behaviour, implementation of new practices |

| 74 | Singer et al. (2015), United States | To examine the relationships between learning‐oriented behaviours by managers and quality and safety performance in the interdisciplinary teams | Safe work environment for taking interpersonal risks | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective work environment Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 75 | Smith et al. (2018), United States | To explore the impact of interpersonal and organizational factors on failure to rescue | ‐ | ‐ |

Performance outcome— Effective rescue Behavioural outcome— Bringing up concerns e – |

| 76 | Stühlinger et al. (2019), Switzerland | To investigate the mechanisms between shared professional language, quality of care, and job satisfaction and examine the role of psychological safety and relational coordination as mediators | ‐ | Interpersonal factor—Effective relationship, high‐quality communication |

Organizational culture outcome— Open atmosphere, conflict management Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour |

| 77 | Swendiman et al. (2019), United States | To describe the personal qualities and teaching methods practised by effective surgical educators | Group‐level phenomenon | ‐ |

Performance outcome— Patient safety Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction |

| 78 | Torralba et al. (2016), United States | To explore the facilitators of psychological safety and the impact of psychological safety on satisfaction with the clinical learning environment | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction |

| 79 | True et al. (2014), United States | To explore teamwork support factors and their impact on team‐based task delegation | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— High‐quality communication |

| 80 | Tucker et al. (2007), United States | To examine the influence of best practice transfer, team learning and process change on the implementation of new practices | ‐ | ‐ |

Psychological outcome— Job satisfaction, engagement in improvement work Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, less disruptive behaviours |

| 81 | Wakatsuki et al. (2018), United States | To describe residents’ perceptions of behaviours by the best teachers | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, asking questions |

|

| 82 | Wakeam et al. (2014), United States | To explore the influence of organizational factors, including psychological safety about failure to rescue | ‐ |

Structure/system factor— Constant team structure |

Performance outcome— Effective rescue Behavioural outcome— High‐quality communication |

| 83 | Wholey et al. (2014), United States | To examine the effect of leadership on interdependence, constructive climate, coordination and improvement initiatives | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Leadership, inclusiveness |

Organizational culture outcome — Coordination Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour |

| 84 | Wilkens and London (2006), United States | To examine relationships between group climate (learning orientation, psychological safety and self‐disclosure), process (feedback and conflict) and performance | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks, group‐level phenomenon | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Learning behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour, bringing up concerns, asking for help |

| 85 | Yanchus et al. (2014), United States | To explore employee's perceptions of communication and experiences of psychological safety in the clinical environment | Perceptions of the consequences of taking interpersonal risks |

Interpersonal factor— Open communication, honest communication, trust (leader–member) |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour, high‐quality communication |

| 86 | Yanchus et al. (2020), United States | To examine the workplace antecedents of engagement and disengagement and clarify the concepts of engagement and disengagement | ‐ |

Interpersonal factor— Effective relationship, teamwork |

Organizational culture outcome— Effective interprofessional relationship Psychological outcome— Work engagement |

| 87 | Zhou et al. (2018), China | To explore the differences in perception of safety climate among different departments and job types | ‐ | ‐ |

Behavioural outcome— Speaking‐up behaviour |

| 88 | Zuber and Moody (2018), United States | To identify the conditions that allowed nurses to consider behaviours for innovation and change | ‐ | ‐ |

Organizational culture outcome— Innovation Behavioural outcome— Interpersonal risk behaviour, speaking‐up behaviour |

Ito, A. , Sato, K. , Yumoto, Y. , Sasaki, M. , & Ogata, Y. (2022). A concept analysis of psychological safety: Further understanding for application to health care. Nursing Open, 9, 467–489. 10.1002/nop2.1086

Funding information

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI, Grant Number JP19H03920

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the Appendix of this article.

REFERENCES

- Agius, S. J. , Willis, S. C. , McArdle, P. J. , & O’Neill, P. A. (2008). Managing change in postgraduate medical education: Still unfreezing? Medical Teacher, 30(4), e87–e94. 10.1080/01421590801929976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albritton, J. A. , Fried, B. , Singh, K. , Weiner, B. J. , Reeve, B. , & Edwards, J. R. (2019). The role of psychological safety and learning behavior in the development of effective quality improvement teams in Ghana: An observational study. BMC Health Services Research, 19, 385. 10.1186/s12913-019-4234-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alingh, C. W. , van Wijngaarden, J. D. H. , van de Voorde, K. , Paauwe, J. , & Huijsman, R. (2019). Speaking up about patient safety concerns: The influence of safety management approaches and climate on nurses’ willingness to speak up. BMJ Quality & Safety, 28(1), 39–48. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-007163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allaire, Y. , & Firsirotu, M. E. (1984). Theories of organizational culture. Organization Studies, 5, 193–226. 10.1177/017084068400500301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, N. P. , Dow, A. , Mazmanian, P. E. , Jundt, D. K. , & Appelbaum, E. N. (2016). The effects of power, leadership and psychological safety on resident event reporting. Medical Education, 50, 343–350. 10.1111/medu.12947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, N. P. , Santen, S. A. , Aboff, B. M. , Vega, R. , Munoz, J. L. , & Hemphill, R. R. (2018). Psychological safety and support: Assessing resident perceptions of the clinical learning environment. Journal of Graduate Medical Education, 10(6), 651–656. 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00286.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnetz, J. , Sudan, S. , Goetz, C. , Counts, S. , & Arnetz, B. (2019). Nurse work environment and stress biomarkers: Possible implications for patient outcomes. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61, 676–681. 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik, D. , & Zierler, B. (2019). Clinical nurses’ experiences and perceptions after the implementation of an interprofessional team intervention: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(3–4), 430–443. 10.1111/jocn.14605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barling, J. , Akers, A. , & Beiko, D. (2018). The impact of positive and negative intraoperative surgeons’ leadership behaviors on surgical team performance. American Journal of Surgery, 215(1), 14–18. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basit, A. A. (2017). Trust in supervisor and job engagement: Mediating effects of psychological safety and felt obligation. Journal of Psychology, 151(8), 701–721. 10.1080/00223980.2017.1372350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindels, E. , Verberg, C. , Scherpbier, A. , Heeneman, S. , & Lombarts, K. (2018). Reflection revisited: How physicians conceptualize and experience reflection in professional practice – A qualitative study. BMC Medical Education, 18(1), 105. 10.1186/s12909-018-1218-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, E. H. , Brewster, A. L. , Fosburgh, H. , Cherlin, E. J. , & Curry, L. A. (2017). Development and psychometric properties of a scale to measure hospital organizational culture for cardiovascular care. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 10(3). 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.116.003422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. , & McCormack, B. G. (2011). Developing the practice context to enable more effective pain management with older people: An action research approach. Implementation Science, 6, 9. 10.1186/1748-5908-6-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, D. , & McCormack, B. (2016). Exploring psychological safety as a component of facilitation within the promoting action on research implementation in health services framework. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 25(19–20), 2921–2932. 10.1111/jocn.13348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buljac‐Samardžić, M. , Dekker‐van Doorn, C. , & Van Wijngaarden, J. (2018). Detach yourself: The positive effect of psychological detachment on patient safety in long‐term care. Journal of Patient Safety, 14, e45‐e46. do: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeli, A. , & Zisu, M. (2009). The relational underpinnings of quality internal auditing in medical clinics in Israel. Social Science and Medicine, 68(5), 894–902. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.12.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark, O. L. , Zickar, M. J. , & Jex, S. M. (2014). Role definition as a moderator of the relationship between safety climate and organizational citizenship behavior among hospital nurses. Journal of Business and Psychology, 29(1), 101–110. 10.1007/s10869-013-9302-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colet, P. C. , Cruz, J. P. , Cacho, G. , Al‐Qubeilat, H. , Soriano, S. S. , & Cruz, C. P. (2018). Perceived infection prevention climate and its predictors among nurses in Saudi Arabia. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 50(2), 134–142. 10.1111/jnu.12360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuellar, A. , Krist, A. H. , Nichols, L. M. , & Kuzel, A. J. (2018). Effect of practice ownership on work environment, learning culture, psychological safety, and burnout. The Annals of Family Medicine, 16(Suppl 1), S44–S51. 10.1370/afm.2198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curry, L. A. , Brault, M. A. , Linnander, E. L. , McNatt, Z. , Brewster, A. L. , Cherlin, E. , Flieger, S. P. , Ting, H. H. , & Bradley, E. H. (2018). Influencing organisational culture to improve hospital performance in care of patients with acute myocardial infarction: A mixed‐methods intervention study. BMJ Quality & Safety, 27(3), 207–217. 10.1136/bmjqs-2017-006989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curşeu, P. L. (2013). Demographic diversity, communication and learning behaviour in healthcare groups. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management, 28(3), 238–247. 10.1002/hpm.2130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brún, A. , & McAuliffe, E. (2020). Identifying the context, mechanisms and outcomes underlying collective leadership in teams: Building a realist programme theory. BMC Health Services Research, 20(1), 261. 10.1186/s12913-020-05129-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derickson, R. , Fishman, J. , Osatuke, K. , Teclaw, R. , & Ramsel, D. (2015). Psychological safety and error reporting within veterans health administration hospitals. Journal of Patient Safety, 11, 60–66. 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44, 350–383. 10.2307/2666999 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. C. (2019). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. C. , Bohmer, R. M. , & Pisano, G. P. (2001). Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 685–716. 10.2307/3094828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edmondson, A. C. , Higgins, M. , Singer, S. , & Weiner, J. (2016). Understanding psychological safety in health care and education organizations: A comparative perspective. Research in Human Development, 13, 65–83. 10.1080/15427609.2016.1141280 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Erichsen Andersson, A. , Frödin, M. , Dellenborg, L. , Wallin, L. , Hök, J. , Gillespie, B. M. , & Wikström, E. (2018). Iterative co‐creation for improved hand hygiene and aseptic techniques in the operating room: Experiences from the safe hands study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 2. 10.1186/s12913-017-2783-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, J. , Elwy, A. R. , Charns, M. P. , Maguire, E. M. , Baker, E. , Burgess, J. F. Jr , & Meterko, M. (2020). Exploring the association between organizational culture and large‐scale adverse events: Evidence from the Veterans Health Administration. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 46(5), 270–281. 10.1016/j.jcjq.2020.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George, J. , Parker, V. A. , Sullivan, J. L. , Greenan, M. A. , Chan, J. , Shin, M. H. , Chen, Q. , Shwartz, M. , & Rosen, A. K. (2020). How hospitals select their patient safety priorities: An exploratory study of four Veterans Health Administration hospitals. Health Care Management Review, 45(4), E56–E67. 10.1097/HMR.0000000000000260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin, H. , Lawrence, E. , Leonard, C. , McCreight, M. , Kelley, L. , Lippmann, B. , Coy, A. , & Burke, R. E. (2019). Brainwriting premortem: A novel focus group method to engage stakeholders and identify preimplementation barriers. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 34(2), 94–100. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin, H. M. , Langner, P. , Gokhale, M. , Osatuke, K. , Hasselbeck, R. , Maddox, T. M. , & Battaglia, C. (2018). Relationship between psychological safety and reporting nonadherence to a safety checklist. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 33(1), 53–60. 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Z. , Van Swol, L. , Xu, Z. , Yin, K. , Zhang, N. , Gul Gilal, F. , & Li, X. (2019). High‐power distance is not always bad: Ethical leadership results in feedback seeking. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2137. 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant, A. M. , Berg, J. M. , & Cable, D. M. (2014). Job titles as identity badges: How self‐reflective titles can reduce emotional exhaustion. Academy of Management Journal, 57(4), 1201–1225. 10.5465/amj.2012.0338 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Greene, M. T. , Gilmartin, H. M. , & Saint, S. (2020). Psychological safety and infection prevention practices: Results from a national survey. American Journal of Infection Control, 48, 2–6. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05619.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R. B. , Leroy, H. , Dierynck, B. , Simons, T. , Savage, G. T. , McCaughey, D. , & Leon, M. R. (2013). Living up to safety values in health care: The effect of leader behavioral integrity on occupational safety. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 18(4), 395–405. 10.1037/a0034086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben, J. R. , & Rathert, C. (2008). The role of continuous quality improvement and psychological safety in predicting work‐arounds. Health Care Management Review, 33, 134–144. 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304505.04932.62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesselgreaves, H. , & MacVicar, R. (2012). Practice‐based small group learning in GP specialty training. Education for Primary Care, 23(1), 27–33. 10.1080/14739879.2012.11494067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirak, R. , Peng, A. C. , Carmeli, A. , & Schaubroeck, J. M. (2012). Linking leader inclusiveness to work unit performance: The importance of psychological safety and learning from failures. Leadership Quarterly, 23, 107–117. 10.1016/j.leaqua.2011.11.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huddleston, P. , & Gray, J. (2016). Describing nurse leaders’ and direct care nurses’ perceptions of a healthy work environment in acute care settings, Part 2. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 46(9), 462–467. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain, A. K. , Fennell, M. L. , Chagpar, A. B. , Connolly, H. K. , & Nembhard, I. M. (2016). Moving toward improved teamwork in cancer care: The role of psychological safety in team communication. Journal of Oncology Practice, 12(11), 1000–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work. Academy of Management Journal, 33, 692–724. 10.2307/256287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, J. Y. , Lee, M. K. , Fairchild, E. M. , Caubet, S. L. , Peters, D. E. , Beliles, G. R. , & Matti, L. K. (2020). Relationships among organizational values, employee engagement, and patient satisfaction in an Academic Medical Center. Mayo Clinic Proceedings: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes, 4(1), 8–20. 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2019.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keitz, S. A. , Aron, D. C. , Brannen, J. L. , Byrne, J. M. , Cannon, G. W. , Clarke, C. T. , Gilman, S. C. , Hettler, D. L. , Kaminetzky, C. P. , Zeiss, R. A. , Bernett, D. S. , Wicker, A. B. , & Kashner, T. M. (2019). Impact of clinical training on recruiting graduating health professionals. The American Journal of Managed Care, 25(4), e111–e118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessel, M. , Kratzer, J. , & Schultz, C. (2012). Psychological safety, knowledge sharing, and creative performance in healthcare teams. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21(2), 147–157. 10.1111/j.1467-8691.2012.00635.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klingberg, K. , Gadelhak, K. , Jegerlehner, S. N. , Brown, A. D. , Exadaktylos, A. K. , & Srivastava, D. S. (2018). Bad manners in the Emergency Department: Incivility among doctors. PLoS One, 13(3), e0194933. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, M. , Weiss, M. , Grote, G. , Knauth, A. , Dambach, M. , Spahn, D. R. , & Grande, B. (2013). TeamGAINS: A tool for structured debriefings for simulation‐based team trainings. BMJ Quality & Safety, 22(7), 541–553. 10.1136/bmjqs-2012-000917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzara, E. H. , Benishek, L. E. , Patzer, B. , Gregory, M. E. , Hughes, A. M. , Heyne, K. , Salas, E. , Kuchkarian, F. , Marttos, A. , & Schulman, C. (2015). Utilizing telemedicine in the trauma Intensive Care Unit: Does it impact teamwork? Telemedicine and e‐Health, 21(8), 670–676. 10.1089/tmj.2014.0074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.‐H. , Yang, C.‐C. , & Chen, T.‐T. (2016). Barriers to incident‐reporting behavior among nursing staff: A study based on the theory of planned behavior. Journal of Management and Organization, 22, 1–18. 10.1017/jmo.2015.8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Leroy, H. , Dierynck, B. , Anseel, F. , Simons, T. , Halbesleben, J. R. , McCaughey, D. , Savage, G. T. , & Sels, L. (2012). Behavioral integrity for safety, priority of safety, psychological safety, and patient safety: A team‐level study. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(6), 1273–1281. 10.1037/a0030076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal, G. S. (1980). What should be done with equity theory? New approaches to the study of fairness in social relationships. In Gergen K., & Willis R. (Eds.), Social exchange: Advances in theory and research (pp. 167–218). Plenum Press. 10.1007/978-1-4613-3087-5_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, B. , Ethington, K. M. , King, C. , Jacobs, J. D. , & Lundeen, H. (2017). Organizational learning in a cardiac intensive care unit: A learning history. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 36(2), 78–86. 10.1097/DCC.0000000000000233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, B. , Shaw, L. , & Moore, C. (2017). Organizational learning in an orthopaedic unit: A learning history. Orthopaedic Nursing, 36(6), 424–431. 10.1097/NOR.0000000000000403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, B. , Gunn, M. M. , & Mendon, C. R. (2020). New graduate registered nurses’ experiences with psychological safety. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(4), 831–839. 10.1111/jonm.13006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacCurtain, S. , Murphy, C. , O’Sullivan, M. , MacMahon, J. , & Turner, T. (2018). To stand back or step in? Exploring the responses of employees who observe workplace bullying. Nursing Inquiry, 25, e12207. 10.1111/nin.12207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martland, J. , Chamberlain, D. , Hutton, A. , & Smigielski, M. (2016). Communication and general concern criterion prior to activation of the rapid response team: A grounded theory. Australian Health Review, 40(5), 477–483. 10.1071/AH15123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meleis, A. I. (2017). Theoretical nursing: Development and progress, 6th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Nembhard, I. M. , & Edmondson, A. C. (2006). Making it safe: The effects of leader inclusiveness and professional status on psychological safety and improvement efforts in health care teams. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27, 941–966. 10.1002/job.413 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman, A. , Donohue, R. , & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27, 521–535. 10.1016/j.hrmr.2017.01.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noah, Y. , & Steve, M. (2012). Work environment and job attitude among employees in a Nigerian work organization. Journal of Sustainable Society, 1, 36–43. 10.11634/21682585140398 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donovan, R. , Van Dun, D. , & McAuliffe, E. (2020). Measuring psychological safety in healthcare teams: Developing an observational measure to complement survey methods. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 20, 203. 10.1186/s12874-020-01066-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary, D. F. (2016). Exploring the importance of team psychological safety in the development of two interprofessional teams. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 30, 29–34. 10.3109/13561820.2015.1072142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (2017). The economics of patient safety in primary and ambulatory care: Flying blind. Retrieved from The‐Economics‐of‐Patient‐Safety‐in‐Primary‐and‐Ambulatory‐Care‐April2018.pdf (oecd.org).

- Ortega, A. , Sánchez‐Manzanares, M. , Gil, F. , & Rico, R. (2013). Enhancing team learning in nursing teams through beliefs about interpersonal context. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(1), 102–111. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2012.05996.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pannick, S. , Archer, S. , Johnston, M. J. , Beveridge, I. , Long, S. J. , Athanasiou, T. , & Sevdalis, N. (2017). Translating concerns into action: A detailed qualitative evaluation of an interdisciplinary intervention on medical wards. British Medical Journal Open, 7(4), e014401. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pogorzelska‐Maziarz, M. , Nembhard, I. M. , Schnall, R. , Nelson, S. , & Stone, P. W. (2016). Psychometric evaluation of an instrument for measuring organizational climate for quality: Evidence from a national sample of infection preventionists. American Journal of Medical Quality, 31(5), 441–447. 10.1177/1062860615587322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Premeaux, S. F. , & Bedeian, A. G. (2003). Breaking the silence: The moderating effects of self‐monitoring in predicting speaking up in the workplace. Journal of Management Studies, 40, 1537–1562. 10.1111/1467-6486.00390 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prestia, A. S. , Sherman, R. O. , & Demezier, C. (2017). Chief nursing officers’ experiences with moral distress. JONA: The Journal of Nursing Administration, 47(2), 101–107. 10.1097/NNA.0000000000000447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prottas, D. J. , & Nummelin, M. R. (2018). Theory X/Y in the health care setting: Employee perceptions, attitudes, and behaviors. The Health Care Manager, 37(2), 109–117. 10.1097/HCM.0000000000000210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raes, E. , Decuyper, S. , Lismont, B. , Van den Bossche, P. , Kyndt, E. , Demeyere, S. , & Dochy, F. (2013). Facilitating team learning through transformational leadership. Instructional Science, 41, 287–305. 10.1007/s11251-012-9228-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rahmati, A. , & Poormirzaei, M. (2018). Predicting nurses’ psychological safety based on the forgiveness skill. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 23(1), 40–44. 10.4103/ijnmr.IJNMR_240_16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramana Feeser, V. , Zemore, Z. , Appelbaum, N. , Santen, S. A. , Moll, J. , Aboff, B. , & Hemphill, R. R. (2019). Analysis of the emergency medicine clinical learning environment. AEM Education and Training, 3(3), 286–290. 10.1002/aet2.10356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rathert, C. , Ishqaidef, G. , & May, D. R. (2009). Improving work environments in health care: Test of a theoretical framework. Health Care Management Review, 34, 334–343. 10.1097/HMR.0b013e3181abce2b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard, A. , Pfeiffer, Y. , & Schwappach, D. (2017). Development and psychometric evaluation of the speaking up about patient safety questionnaire. Journal of Patient Safety. Advance Online Publication, 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers, B. L. (2000). Concept analysis: An evolutionary view. In Rodgers B. L., & Knafl K. A. (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications, 2nd ed. (pp. 77–102). W. B. Saunders. [Google Scholar]