Significance

Sleep contributes to long-term memory formation after learning, but underlying mechanisms remain unclear. We found that post-learning sleep promoted the formation of dendritic filopodia and spines clustered with learning-inactive existing spines. A fraction of these filopodia was converted into new spines over extended periods of time. These findings provide insights into the role of post-learning sleep in regulating the number and location of new synapses via promoting dendritic filopodial formation.

Keywords: dendritic spines, filopodia, clustering, sleep

Abstract

Changes in synaptic connections are believed to underlie long-term memory storage. Previous studies have suggested that sleep is important for synapse formation after learning, but how sleep is involved in the process of synapse formation remains unclear. To address this question, we used transcranial two-photon microscopy to investigate the effect of postlearning sleep on the location of newly formed dendritic filopodia and spines of layer 5 pyramidal neurons in the primary motor cortex of adolescent mice. We found that newly formed filopodia and spines were partially clustered with existing spines along individual dendritic segments 24 h after motor training. Notably, posttraining sleep was critical for promoting the formation of dendritic filopodia and spines clustered with existing spines within 8 h. A fraction of these filopodia was converted into new spines and contributed to clustered spine formation 24 h after motor training. This sleep-dependent spine formation via filopodia was different from retraining-induced new spine formation, which emerged from dendritic shafts without prior presence of filopodia. Furthermore, sleep-dependent new filopodia and spines tended to be formed away from existing spines that were active at the time of motor training. Taken together, these findings reveal a role of postlearning sleep in regulating the number and location of new synapses via promoting filopodial formation.

Learning and memory consolidation are associated with the rewiring of neuronal network connectivity (1–3). Previous studies have shown that motor training leads to the formation and elimination of postsynaptic dendritic spines of pyramidal neurons in the primary motor cortex (M1) (4–8). Learning-induced new spines stabilize and persist over long periods of time (4). The extent of spine remodeling correlates with behavioral improvement after learning (4, 9), and the disruption of spine remodeling impairs learned motor behavior (10–12). These studies suggest that learning-induced new synapses contribute to changes in neuronal circuits that are likely important for the retention of learned behaviors (13, 14).

Cumulative evidence suggests that sleep affects synaptic structural plasticity in many brain regions (15–17). For example, sleep has been shown to promote spine formation and elimination in developing somatosensory and visual cortices (18, 19). In the motor cortex, sleep promotes branch-specific formation of new dendritic spines following motor learning and selectively stabilizes learning-induced new synaptic connections (11, 12). Sleep has also been shown to regulate dendritic spine numbers in hippocampal CA1 area (20–22). In addition, many lines of evidence have revealed the function of sleep in increasing, decreasing, or stabilizing synaptic strength and neuronal firing in various brain regions (23–31). Together, these studies strongly suggest that sleep has an important role in promoting synaptic structural plasticity in neuronal circuits during development and after learning.

While sleep promotes the formation of new spines after learning (12), it remains unknown how postlearning sleep regulates new synapse formation along dendritic branches. Synapse formation is a prolonged process often involving the generation of dendritic filopodia, thin and long protrusions without bulbous heads (32–35). These highly dynamic filopodia have been shown to initiate the contact with presynaptic axonal terminals and transform into new spines (36, 37). It is not known whether sleep promotes new spine formation via filopodia formation and subsequent transformation. Furthermore, it is also unclear whether sleep-dependent formation of new dendritic protrusions (filopodia and spines) is distributed on dendritic branches in a random or nonrandom manner. On the one hand, new synapses may be formed in clusters with synapses of similar functions to allow nonlinear summation of inputs important for increasing memory storage capacity (9, 38–43). On the other hand, new connections may be formed preferentially near less active/strong synapses to avoid competition for limited synaptic resources (44–47).

In this study, we found that dendritic filopodia and spines formed after motor training were partially clustered with existing spines on apical tuft dendrites of layer 5 (L5) pyramidal neurons in the mouse primary motor cortex. Posttraining sleep was critical for the clustered formation of new filopodia, some of which were transformed into new spines. In addition, the clustered new filopodia and spines tended to be formed near existing spines that were inactive at the time of motor training. These findings reveal a role for sleep in neuronal circuit plasticity by promoting clustered spine formation via dendritic filopodia near learning-inactive existing spines.

Results

Sleep Promotes Clustered Formation of New Filopodia and Spines with Existing Spines within 8 h after Motor Training.

Previous studies have shown that motor learning promotes the formation of new spines on apical tuft branches of L5 pyramidal neurons in the motor cortex (4, 5). Furthermore, motor learning–induced new spine formation is dependent on postlearning sleep (12). To better understand how motor training and subsequent sleep promote new spine formation, we examined the number and location of new spines and filopodia within individual dendritic segments in mice with undisturbed sleep and with sleep deprivation (SD) after rotarod motor training. SD was carried out by gentle handling between two imaging sessions and following motor training (Fig. 1A). Electroencephalography (EEG) and electromyography (EMG) recordings over 8 h showed that SD mice were awake 98.3 ± 0.02% of the time, whereas mice with undisturbed sleep were awake 29.4 ± 1.4% of the time (SI Appendix, Fig. S1).

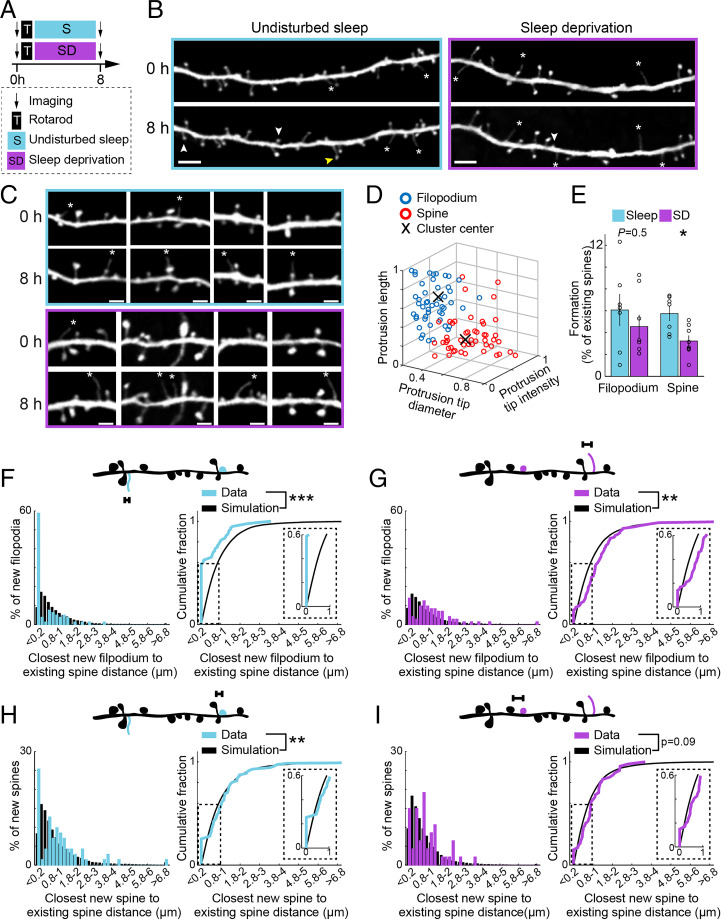

Fig. 1.

Sleep promotes clustered formation of new filopodia and spines with existing spines within 8 h after motor training. (A) Schematic of experimental paradigm. After imaging and training, mice were either left undisturbed or subjected to SD. They were then imaged again to assess the effect of SD. (B) Example of new spines (white arrowheads), filopodia (asterisks), and filopodium transition into spine (yellow arrowhead) in a L5 pyramidal cell dendrite 8 h following rotarod training and sleep (Left) or rotarod training and SD (Right) (Scale bar: 5 µm). (C) Examples of new filopodia (asterisks) in L5 pyramidal cell dendrites 8 h following rotarod training and sleep (Top) or rotarod training and SD (Bottom) (Scale bar: 2 µm). (D) Characteristics of new protrusions following rotarod motor training in sleep and sleep-deprived animals. For each new protrusion (circle), its head intensity (normalized to adjacent shaft), head diameter, and length are plotted. Protrusions defined as spines and filopodia based on these morphological characteristics are color coded (red and blue respectively). X marks the center of each cluster based on K-means algorithm. A total of 51 new spines and 49 new filopodia from eight animals. Data from sleep and sleep-deprived animals were not different and were pooled together. (E) The percentage of dendritic filopodia and spines formed in sleep (blue) and sleep-deprived (purple) mice. Black circles: individual animals. A total of 7 and 8 mice in sleep and sleep-deprivation groups, respectively. (F) Top: schematic of distances measured on individual dendritic segments between new filopodium (blue) and existing spines (black). Left: distribution of closest distances measured (blue) and simulated (black, Materials and Methods) in animals left undisturbed following motor training. Right: Cumulative sum of closest distances measured (blue) saturate faster than simulated (black), showing new filopodia cluster with existing spines. Inset: enlargement of 0 to 1 µm distance. A total of 80 new filopodia in 42 dendrites from seven animals. (G) Similar as in F for animals subjected to SD. Following SD, new filopodia do not cluster with existing spines and are further away from existing spines than expected by chance. A total of 72 new filopodia in 44 dendrites from eight animals. (H) Similar as in F for new spines in animals with undisturbed sleep. Following sleep, new spines cluster with existing spines. A total of 71 new spines in 42 dendrites from seven animals. (I) Similar as in F for new spines in animals subjected to SD. Following SD, new spines do not cluster with existing spines and are randomly distributed. A total of 47 new spines in 44 dendrites from eight animals. Percent formation was tested using Mann–Whitney U test. Cumulative sums were tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Transcranial two-photon microscopy was used to image apical dendrites of L5 pyramidal neurons expressing yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) in the primary motor cortex of 1-mo-old mice with or without SD over a period of 8 h (Fig. 1 A and B). Consistent with previous studies (4, 5), we found that in 1-mo-old mice (t = 0 h), the majority of dendritic protrusions on apical dendrites of L5 pyramidal neurons were spines typically with a well-defined head (87.9 ± 1.07%, 5,270 total protrusions in 23 mice). A small fraction of the protrusions were filopodia that were longer, thinner protrusions without a bulbous head (12.02% ± 1.07%; Fig. 1 B and C). New spines and filopodia showed clear morphological separation in protrusion head diameter (0.53 ± 0.01 µm versus 0.3 ± 0.01 µm, P < 0.0001), normalized head intensity (0.27 ± 0.01 versus 0.11 ± 0.01, P < 0.0001), and total length (1.36 ± 0.11 µm versus 2.64 ± 0.13 µm, P < 0.0001; Fig. 1 C and D and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). These morphological differences between filopodia and spines support the view that filopodia are less mature structures than spines and serve as spine precursors (32–37, 48, 49).

In line with previous findings (12), the formation rate of training-related new filopodia over 8 h was comparable between mice with undisturbed sleep and mice with SD (Fig. 1E; 6.0 ± 1.4% versus 4.5 ± 1.03%, P = 0.5). Furthermore, we found that ∼94% of filopodia were formed directly from the dendritic shaft [31 out of 33 filopodia in mice with undisturbed sleep (n = 4); 15 out of 16 filopodia in mice with SD (n =4)]. Only ∼6% of filopodia were from spine heads (50–53), indicating vast majority of filopodia are originated from dendritic shaft in the motor cortex of 1-mo-old adolescent mice. To examine whether sleep may affect the distribution of newly formed filopodia along individual dendritic segments, we compared the location of new filopodia relative to the location of spines that already existed before training in mice with and without sleep. Specifically, we compared the closest distance measured between new filopodia and existing spines to the distance measured for simulated new filopodia independently generated from a random distribution (Fig. 1F and Materials and Methods). Interestingly, in mice with undisturbed sleep, new filopodia were not formed randomly along dendritic segments relative to existing spines but rather had a higher-than-expected chance to be formed very close (≤ 0.2 µm) to existing spines (Fig. 1F and Table 1; P < 0.0001). Unlike the simulated data, the measured closest distances between newly formed filopodia and existing spines exhibited a bimodal distribution with peaks around 0.2 and 0.8 µm (Fig. 1F; fit to Gaussian order 2, sum of squares due to errors (SSE) = 0.002, R2 = 0.99). Thus, within 8 h following rotarod training and sleep, new filopodia were partially clustered at ≤ 0.2 µm with existing spines. In contrast, new filopodia in SD animals were not clustered with existing spines (Fig. 1G and Table 1; P = 0.54), and their locations relative to existing spines on dendritic segments were further away than expected by random simulation (Fig. 1G; P < 0.01). The percentage of new filopodia that were ≤ 0.2 µm away from existing spines was significantly reduced in SD mice compared with undisturbed group (11.92 ± 4.5% versus 63.21 ± 8.6%, P < 0.001).

Table 1.

Percent protrusions that are ≤0.2 µm from existing spines relative to simulation

| Time/Figure | Condition | Protrusion type | Simulation 95% CI | Data | P value |

| 0 to 8 h (Fig. 1) | Sleep | New filopodia | 10.0 to 26.25% | 62.5% | P < 0.00001 |

| 0 to 8 h (Fig. 1) | SD | New filopodia | 8.33 to 25.69% | 16.6% | P = 0.54 |

| 0 to 8 h (Fig. 1) | Sleep | New spines | 8.45 to 25.35% | 25.3% | P = 0.03 |

| 0 to 8 h (Fig. 1) | SD | New spines | 8.51 to 31.91% | 14.8% | P = 0.8 |

| 0 to 24 h (Fig. 2) | Training | New spines | 9.75 to 20.73% | 26.2% | P < 0.00001 |

| 24 to 26 h (Fig. 3) | Retraining | New protrusions | 9.4 to 22.22% | 29.9% | P < 0.00001 |

| 0 to 8 h (SI Appendix, Fig. S5) | Treadmill training | New protrusions | 7.14 to 20.4% | 26.5% | P < 0.00001 |

Each row tests the clustering of new protrusions with existing spines for different conditions. For each condition, we simulated the locations of new protrusions onto dendritic segments 1,000 times (shuffles) to create the null distribution of distances between new protrusions and existing spines (Materials and Methods). For each shuffle, we examined the percent of simulated new protrusions that were ≤0.2 µm from existing spines and then calculated the 95% CI (fourth column). We then determined whether the real percent of clustered new protrusions in the data (fifth column) was statistically different from the simulated percent (P, sixth column). P was determined as 1 minus the ratio of shuffles for which the percent in the simulation was larger than the percent in the data.

As reported previously (12), we found that the formation rate of training-induced new spines over 8 h was significantly reduced in mice with SD as compared with mice with undisturbed sleep (Fig. 1E; 3.2 ± 0.4% versus 5.7 ± 0.6%, P = 0.02). Notably, similar to new filopodia, we observed that new spines also showed a higher-than-expected chance to be formed at ≤ 0.2 µm from existing spines in mice with undisturbed sleep but not in mice with SD (Fig. 1 H and I and SI Appendix, Fig. S3 and Table 1; P = 0.03 and 0.8 for sleep and SD, respectively). In mice with undisturbed sleep, the percentage of clustered new filopodia was significantly higher than that of clustered new spines (63.21 ± 8.6% versus 23.26 ± 7.3%, P < 0.01). Together, these results indicate that sleep promotes the clustered formation of new dendritic protrusions, especially filopodia, with existing spines within 8 h after motor training.

Sleep-Dependent Clustered Formation of New Filopodia Contributes to Clustered New Spine Formation 24 h after Training.

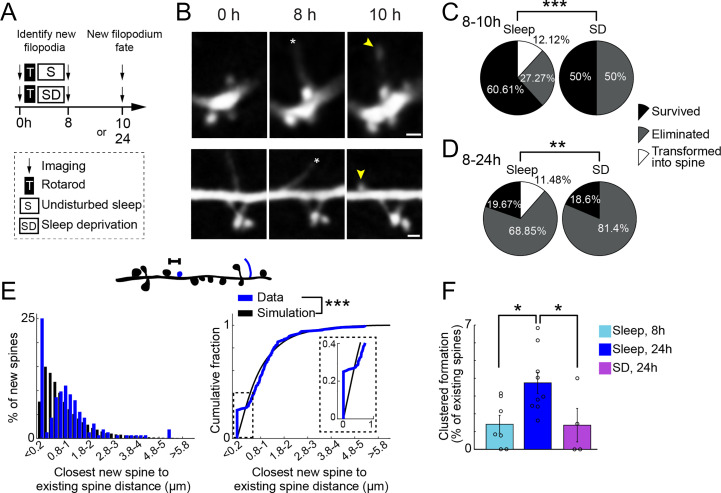

Many lines of evidence suggest that dendritic filopodia are highly dynamic structures involved in activity-dependent spinogenesis and synapse formation (32, 33). Given the finding that sleep promotes clustered formation of filopodia with existing spines over 8 h, it raises the possibility that some of the clustered filopodia may contribute to clustered spine formation over extended periods of time. To test this possibility, we followed all new filopodia that were formed over 8 h with or without posttraining sleep and examined their fate 2 h later (Fig. 2A). New filopodia remaining in the same location with similar filopodia-like morphological characteristics were classified as “survived.” New filopodia remaining in the same location transitioning to spine-like morphological characteristics were classified as “transformed into spines” (Fig. 2B). New filopodia not present in the later imaging session were classified as “eliminated.” We found that the fate of new filopodia distributed differently between sleep and SD animals (Fig. 2C; P < 0.0001): only in animals with sleep after learning were filopodia transformed into spines (12.12% of 33 new filopodia) between 8 to 10 h. Furthermore, these transformed filopodia were all originated from dendritic shafts, and 50% of them (2 out of 4) were located at ≤ 0.2 µm from existing spines. In contrast, none of new filopodia (0 out of 16) in SD animals were transformed into spines between 8 and 10 h.

Fig. 2.

Sleep-dependent clustered formation of new filopodia contributes to clustered new spine formation 24 h after training. (A) Schematic of experimental paradigm. The fate of new filopodia identified at 8 h was determined at either 10 h or 24 h. (B) Examples of new filopodia (asterisks) in L5 pyramidal cell dendrites 8 h following rotarod training and sleep that were transformed into new spines at 10 h (yellow arrowhead) (Scale bar: 1 µm). (C) New filopodia fate. Sleep and sleep-deprived animals were imaged again at 10 h to assess the fate of new filopodia (survived, eliminated, or transformed into spine). Only in sleep animals new filopodia were transformed into new spines. Sleep; 33 new filopodia in four mice. SD; 16 new filopodia in four mice. (D) Similar as in C for filopodia fate at 24 h. Only in sleep animals new filopodia were transformed into new spines. Sleep; 61 new filopodia in 4 mice. SD; 43 new filopodia in 4 mice. (E) Top: schematic of distances measured on individual dendritic segments between new spines (blue) and existing spines (black). Left: distribution of closest distances measured (blue) and simulated (black, Materials and Methods) in animals left undisturbed 24 h following motor training. Right: Cumulative sum of closest distances measured (blue) saturate faster than simulated (black), showing new spines cluster with existing spines 24 h following motor training. Inset: enlargement of 0 to 1 µm distance. A total of 164 new spines in 82 dendrites from nine animals. (F) The percentage of clustered new spines over existing spines formed 24 h following training in mice left undisturbed (blue) is larger than that formed 8 h following training in mice left undisturbed (light blue), as well as that formed 24 h following training in mice with SD (purple); 7, 9, and 4 mice, respectively. Distribution of new filopodia fate was tested using χ2 test. Cumulative sum was tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Percent clustered formation was tested using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Tukey–Kramer for multiple comparison. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Similar results were observed when we followed the fate of filopodia formed between 0 and 8 h at 24 h in mice with undisturbed sleep and SD (Fig. 2A). In mice with sleep, we found that 11.48% of filopodia (61 new filopodia) formed at 8 h were converted into new spines at 24 h. A total of 57.14% of these new spines (four out of seven) were located within 0.2 µm of existing spines. In the SD group, none of the filopodia (0 out of 43 new filopodia) became spines at 24 h (Fig. 2D; sleep versus SD, P < 0.01).

When the location of new spines relative to the location of existing spines was examined 24 h after motor training, we found that new spines were clustered with existing spines in mice with sleep (Fig. 2E and Table 1; P < 0.0001). Furthermore, the percentage of clustered new spines over existing spines was significantly lower at 8 h than at 24 h (Fig. 2F; 1.4 ± 0.5% versus 3.7 ± 0.5%, P = 0.03), suggesting that clustered new spine formation progresses and accumulates over time. In addition, the percentage of new spines clustered with existing spines was significantly higher at 24 h in mice with sleep than without (Fig. 2F; 3.7 ± 0.5% versus 1.3 ± 0.9%; P = 0.03). Together, these results suggest that sleep promotes clustered filopodia formation, which leads to clustered formation of spines observed at 24 h.

Retraining Promotes Rapid Spine Formation without Intermediate Filopodium Transformation.

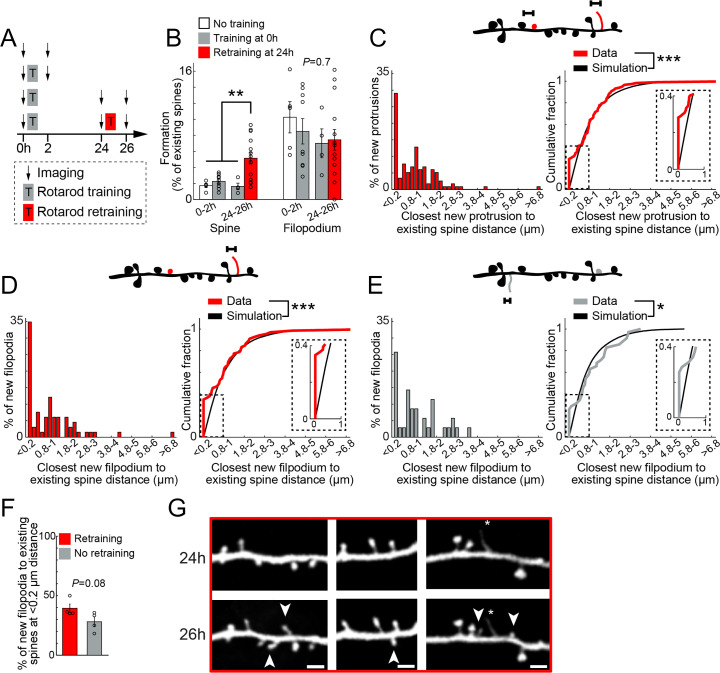

It has been shown that repetitive training over days induces new spines near previously formed new spines (9). To better understand clustered formation of new spines and filopodia, mice were subjected to a second training (retraining) session 24 h after the initial training. We found that the retraining further improves animals’ behavioral performance (18.17 ± 6.4% improvement following retraining, P = 0.03, 5 mice). Within 2 h after the initial training, the formation rate of new spines in trained mice was not significantly different from that in mice that did not receive motor training (Fig. 3 A and B; 2.2 ± 0.2% versus 1.7 ± 0.2%). In contrast, the formation rate of new spines was significantly higher within 2 h after retraining (24 h after the initial training) compared with animals receiving a single training session (Fig. 3 A and B; 5.14 ± 0.7% versus 1.6 ± 0.4%; P < 0.01). We did not see a significant effect on the formation rate of filopodia (Fig. 3 A and B; P = 0.7). These results suggest that retraining, not the initial training, causes rapid spine formation within 2 h.

Fig. 3.

Retraining promotes rapid spine formation without intermediate filopodium transformation. (A) Schematic of experimental paradigm. Animals either did not receive rotarod training, were trained once (training), or twice (retraining). Animals were imaged before and 2 h following training and retraining. Some animals were imaged in all four time points. (B) The percentage of dendritic spines and filopodia formed over 2 h in response to training (Left, gray versus white) and retraining (Right, red versus gray). Black circles: individual animals. Five and nine mice for no training and training, respectively. A total of 4 and 14 mice for no retraining and retraining, respectively. Retraining but not initial training led to rapid new spine formation within 2 h. (C) Top: schematic of distances measured on individual dendritic segments between retraining-induced new spines and filopodia (red) and existing spines (black). Left: distribution of closest distances measured in retraining animals. Right: Cumulative sum of closest distances measured (red) saturate faster than simulated (black, Materials and Methods), showing new protrusions following retraining cluster with existing spines. Inset: enlargement of 0 to 1 µm distance. A total of 117 new protrusions in 48 dendrites from five animals. (D) Similar as in C for new filopodia in retraining animals. Following retraining, new filopodia cluster with existing spines. A total of 66 new filopodia in 48 dendrites from five animals. (E) Similar as in C for new filopodia in animals receiving a single training session (no retraining). Similar to retraining, also in control new filopodia cluster with existing spines. A total of 35 new filopodia in 34 dendrites from four animals. (F) The percentage of new filopodia that are ≤ 0.2 µm from existing spines is similar in animals that did (red, 4 mice) or did not (gray, 4 mice) receive retraining. Black circles: individual animals. (G) Examples of retraining-induced new spines (arrowheads) at 26 h without prior filopodia presences at 24 h (Scale bar: 2 µm). Percent formation was tested using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Tukey–Kramer for multiple comparison. Cumulative sums were tested using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. New filopodia at ≤ 0.2 µm were tested using Mann–Whitney U test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

When we examined the location of retraining-induced new spines and filopodia along individual dendritic segments, we found that retraining-induced new protrusions were not randomly distributed along dendritic segments and were clustered with existing spines (Fig. 3C and Table 1; P < 0.0001), suggesting that the second motor training session promoted clustered formation similar to the effects of sleep. However, there are several differences between sleep and retraining-induced formation of new spines and filopodia. First, unlike sleep, the retraining experience did not affect the locations of retraining-induced new filopodia relative to existing spines along individual dendritic segments (Fig. 3 D and E; 1.02 ± 0.17 µm versus 1.06 ± 0.17 µm for retraining and no retraining respectively, P = 0.5), as well as the percent of new filopodia clustered with existing spines (Fig. 3F; 39.4 ± 3.5% versus 28.06 ± 4% for retraining and no retraining respectively, P = 0.08). Second, we observed that a high percentage of retraining-induced new spines (85.7%) were formed directly from the dendritic shafts without the presence of filopodia in the previous imaging session 2 h earlier (Fig. 3G). Together, these observations suggest that retraining promotes the clustered formation of new spines through mechanisms different from sleep-dependent filopodial formation and transformation into spines.

Interestingly, we found that the initial formation of new spines induced by rotarod training was not clustered relative to other new spines along dendritic segments (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C). However, retraining-induced new spines were clustered with new spines induced by the initial training and subsequent sleep over 24 h, and this clustering was maximal at ∼4 µm distance (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A, D, and E). These results are consistent with previous studies (8, 9), suggesting that repetitive training induces clustered formation of new spines at the range of ∼4 µm.

Clustered New Protrusions Are Formed near Inactive Existing Spines.

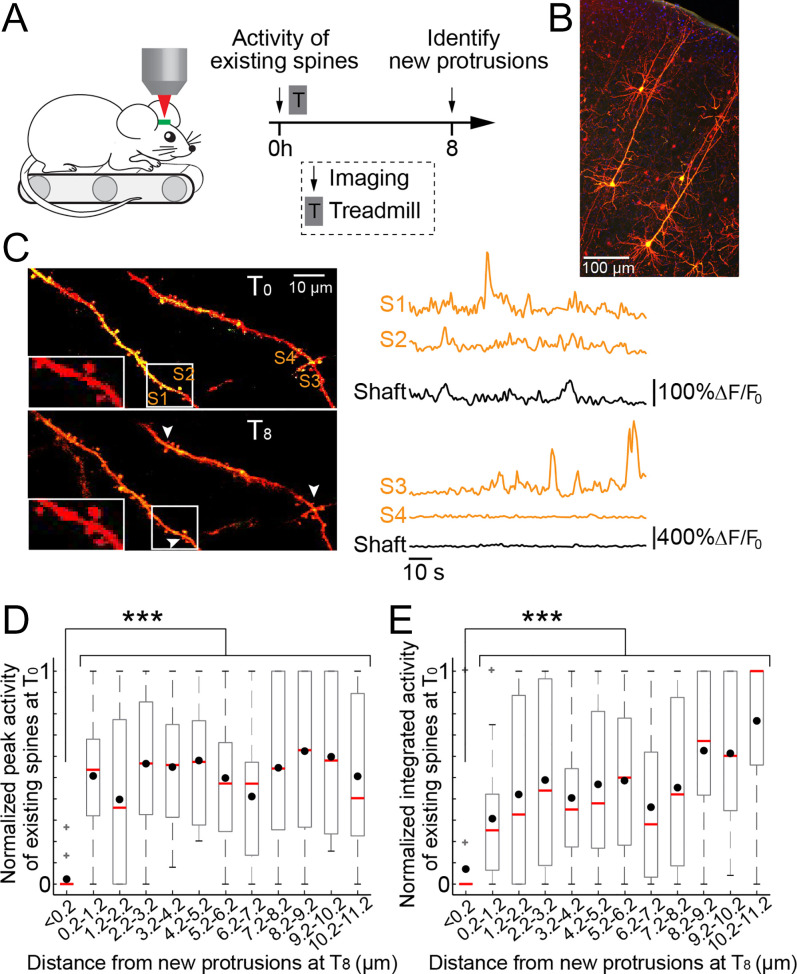

Previous studies have shown that active spines could trigger downstream signaling cascades and affect the plasticity of neighboring spines (54, 55). This raised the possibility that new spines/filopodia may preferentially form in close proximity to active existing spines. However, it is also possible that new spines/filopodia would rather form away from active existing spines to avoid competition for resources. To investigate these two possibilities, we measured the activity of existing spines at various distances from new protrusions that were formed 8 h following the training (Fig. 4A). In this experiment, head-restrained mice were trained to run on a custom-built treadmill under a two-photon microscope. We sparsely labeled L5 pyramidal neurons with both a genetically encoded Ca2+ indicator (GCaMP7s) and a red structural marker (tdTomato) (Fig. 4B and Materials and Methods). This enabled us to monitor the Ca2+ activity of existing spines in response to treadmill training and subsequently identify training-induced new spines and filopodia on the same dendritic segments 8 h later (Fig. 4 A–C).

Fig. 4.

Clustered new protrusions are formed near inactive existing spines. (A) Schematic of experimental paradigm. Ca2+ activity of existing spines was imaged in response to running on the treadmill before training. At 8 h later, the animals were imaged again, and training-induced new spines and filopodia were identified. (B) L5 pyramidal neurons were sparsely labeled with both GCaMP7s and tdTomato in M1. (C) Left: example of two dendrites from the same L5 pyramidal neuron at times 0 h (Top) and 8 h (Bottom). White rectangle box is enlarged on the Left. Arrowheads point to three new spines. Right: ΔF/F0 of single spines marked on the image and the dendritic shafts. (D) Normalized peak activity of existing spines at time 0 h in response to forward running on the treadmill as a function of their distance from where new spines and filopodia were formed 8 h later. Existing spines that are clustered (≤ 0.2 µm) with new protrusions are less active. Black dots indicate the mean. Red lines indicate the median. Gray box shows the 25th and the 75th percentile, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data point not considered outliers. Gray pluses show individual outliers. A total of 219 existing spines relative to 98 new protrusions from seven mice. (E) Similar as in D showing the normalized integrated activity of existing spines at time 0 h. Existing spines that are clustered (≤ 0.2 µm) with new protrusions are less active. A total of 219 existing spines relative to 98 new protrusions from seven mice. Activity of existing spines as a function of distance from new protrusions was tested using Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Tukey–Kramer test for multiple comparisons. ***P < 0.001.

Similar to the rotarod training, the treadmill running paradigm also led to an increase in spine formation (12) and clustered formation of new protrusions along dendritic segments (SI Appendix, Fig. S5 and Table 1). In mice running on the treadmill, we found that many existing spines showed Ca2+ transients either independently or in parallel to the dendritic Ca2+ activity (Fig. 4C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6). When the contribution of the dendritic shaft activity was subtracted from the spine activity (SI Appendix, Fig. S6), we found that at the time of motor training, the average peak, or integrated running-related Ca2+ activity of existing spines that were very close (≤ 0.2 µm) to where new spines or filopodia formed 8 h later were significantly lower than the activity of existing spines that were further away (P < 0.0001, Fig. 4 D and E). These results indicate that clustered formation (at ≤ 0.2 µm) of new spines/filopodia tend to be away from existing spines that are active at the time of motor training, potentially avoiding competition for limited resources.

Discussion

The impact of sleep on synaptic connectivity remains debated. Some evidence shows sleep promotes general synaptic weakening to counteract net synaptic strengthening during awake states, supporting a role of sleep in synaptic homeostatic downscaling (16, 23, 56). Other studies indicate sleep promotes synapse formation and stabilization, suggesting a role of sleep in facilitating the rewiring and maintenance of synaptic circuits (11, 12, 26, 57–59). We found that sleep promotes the formation of new filopodia and spines near existing spines at very short distances (≤ 0.2 µm). Some of those filopodia were converted into clustered new spines over time. These results point to a role of sleep in determining locations of new synapses by regulating the formation of filopodia and spines within individual dendritic segments following motor training. They also suggest that sleep contributes to the rewiring, not simply homeostatic downscaling, of neuronal circuits.

Previous timelapse imaging studies in neuronal cultures and brain slices have shown that spines are formed either directly from dendritic shafts or are transformed from dendritic filopodia (32, 60). Unlike spines that last for hours to months, the vast majority of dendritic filopodia undergo rapid extension and retraction within minutes to hours (32, 33, 35, 48, 60–62). Consistent with the role of filopodia in spinogenesis and synapse formation, a small fraction of these highly dynamic filopodia are found to be transformed into persistent spines in the living mouse cortex (35, 48). While many nascent filopodia do not bear any synaptic contacts, some could make several contacts with multiple axons (36). In addition, electron microscopic studies show that dendritic filopodia may form synaptic contact with axonal terminals within hours (63–65). Together, these findings support a view that highly dynamic dendritic filopodia sample and initiate contacts with the surrounding axons and if successful, are transformed into dendritic spines with synapses (35, 60, 66–68). Our findings suggest that sleep promotes clustered formation of filopodia near existing spines whereas retraining induces new spines directly from dendritic shafts. Thus, sleep does not appear to simply serve as the role of “offline retraining,” underscoring the unique role of sleep in learning-induced changes of synaptic connections by regulating the genesis of filopodia and their maturation to spines.

The signaling mechanisms driving sleep- and retraining-dependent filopodium/spine formation remain to be determined. The direct growths of both spines and filopodia from dendrites have been observed in response to increased neuronal activity and local glutamate application (33, 51, 69, 70). Glutamate release has been shown to induce the formation of either filopodia (33, 51, 71, 72) or spines (73), depending on the level and pattern of stimuli, as well as the activation of NMDA receptors on postsynaptic dendrites. It is thus possible that glutamate release from active presynaptic terminals during sleep differs substantially from that during retraining, leading to differential induction of filopodia and spines, respectively. Notably, we found new protrusions tend to be formed away from active existing spines during motor training. This observation raises an intriguing possibility that the growth of new filopodia and spines near inactive, rather than active, existing spines may be related to competition for resources within sub-µm distances. As existing spines that are stimulated/activated need resources for their expression of synaptic potentiation (74, 75), new spines and nearby existing spines (at ≤ 0.2 µm) with potentially different functions may not compete for synaptic building blocks required for synaptic plasticity at the same time). Future studies are needed to investigate such a possibility and whether sleep also promotes the formation of new filopodia/spines preferentially near less-active existing synapses in response to learning in other brain regions.

Materials and Methods

Experimental Animals.

Mice expressing YFP in L5 pyramidal neurons (Thy1-YFP H-line) or wild-type mice (C57BL/6) were group housed (five per cage) in New York University Medical Center (NYUMC) Skirball animal facilities. Mice were maintained at 22 ± 2 °C with a 12-h light:dark cycle. All experiments were conducted during the light cycle between 08:00 and 18:00. Food and water were available at libitum. Animals of both sexes (1-mo-old) were used for all the experiments in accordance with ethical regulations and the NYUMC guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at NYUMC.

Rotarod and Treadmill Training.

An EZRod system with a test chamber (44.5 × 14 × 51 cm dimensions) was used in this study similarly as was previously described (12). Specifically, animals were placed on the motorized rod (30 mm in diameter) in the chamber. The rotation speed gradually increased from 0 to 100 r. p. m. over the course of 3 min. The time latency and rotation speed were recorded when the animal was unable to keep up with the increasing speed and fell. Rotarod training/testing was performed in one 30-min session (20 trials, training and retraining conditions) or one 60-min session (40 trials, sleep and SD conditions). Performance was measured as the average speed animals achieved during the training session.

A custom-built free-floating treadmill (96 cm × 56 cm × 61 cm dimensions) was also used for motor training in this study as was previously described (12). Specifically, head-fixed animals were placed on a custom-made head holder/body support device that allowed the micrometal bars (attached to the animal's skull) to be mounted so that the mouse forelimbs were positioned on top of the treadmill belt and its head was below the microscope objective. Mice were allowed to only move their forelimbs for locomotion. The treadmill belt was cut out of black rubber sheets (0.031’’) and was connected to a motor (Dayton, Model 2L010, Grainger) driven by a DC power supply (Extech). During motor training and at the onset of a running trial, the motor was turned on and the treadmill belt speed gradually increased from 0 cm/s to 8 cm/s within ∼3 s. The speed of 8 cm/s was kept for the rest of the trial as the animals were forced to run forward. Training was performed in two 30-min sessions interleaved by 10-min rest in which the treadmill motor was turned off. Performance was measured by analyzing animals’ gait patterns. To assay gait patterns, mouse forelimbs were coated into ink and animals ran on white construction paper. Footprints were analyzed offline as previously described (76, 77). Previous studies have suggested that the treadmill motor task involves motor skill learning similar as the rotarod task. First, similar to rotarod training, mice subjected to the treadmill running demonstrated rapid (over hours) and slow (over days) phases of behavioral improvement (76). Second, the behavioral improvement is dependent on activity in the M1 (76) and on synaptic plasticity within the M1 (77). Third, treadmill training induces rapid new spine formation similar to rotarod training (12).

SD.

SD was achieved through gentle handling over a period of ∼7 h after the first imaging session and rotarod training. Specifically, mice were gently touched with a cotton applicator for 1 to 2 s whenever they displayed signs of drowsiness. On average, mice were touched ∼23 times per hour during the period of SD.

Imaging Dendritic Spine Structural Plasticity in Awake, Head-Restrained Mice.

Dendritic spines on apical tuft dendrites of L5 pyramidal neurons were examined in longitudinal studies by imaging the mouse motor cortex through a thinned-skull window as described previously (12, 78). Briefly, 1-mo-old mice expressing YFP were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (10 mg/kg). The mouse head was shaved, and the skull surface was exposed with a midline scalp incision. The periosteum tissue over the skull surface was removed without damaging the temporal and occipital muscles. A head holder composed of two parallel micrometal bars was attached to the animal’s skull to help restrain the animal’s head and reduce motion-induced artifact during imaging. In some animals, four electrodes were implanted to allow simultaneous imaging and EEG/EMG recording in the same animal. Two electrodes were used for recording epidural EEG and two for recording EMG. Each electrode was made by soldering one end of an epoxy-coated silver wire (0.005 inch in diameter) to a connector pin. One EEG electrode was placed over the left frontal cortex (at 2 mm lateral to midline, 2 mm anterior to bregma) and another on the cerebellum (at midline, 1 mm posterior to lambdoid suture). Before the electrode implantation, a small area of skull (each ∼0.2 mm in diameter) was thinned with a high-speed drill and carefully removed with forceps. The electrodes were bent at 1 mm from the tip of the silver wire and carefully inserted under the skull above the dural matter. The electrodes were fixed by cyanoacrylate-based glue and further stabilized by dental cement. Two electrodes for EMG recording were placed on the nuchal muscle. After attachment of the head holder and implantation of the EEG/EMG electrodes, thinned skull windows were made with high-speed microdrills. Skull thickness was reduced to about 20 µm over a small region (200 × 200 µm) above the M1 based on stereotaxic coordinates (at 1.0 mm posterior to bregma and 1.5 mm lateral to midline). Completed cranial window was covered with silicon elastomer and the animals were returned to their home cages to recover.

Before imaging, mice were given 1 d to recover from the surgery related anesthesia and habituated for a few times (10 min each) in the imaging apparatus to minimize potential stress effects due to head restraining and awake imaging. A two-photon microscope (Olympus FV1000MPE) equipped with a Ti:Sapphire laser (MaiTai DeepSee Spectra Physics) tuned to 920 nm was used to acquire images (60× water immersion lens, numerical aperture [N.A.] = 1.1). Two to three stacks of image planes (66.7 × 66.7 μm; 512 × 512 pixel) within a depth of 100 μm from the pial surface were collected at each time point, yielding a full three-dimensional (3D) data set of dendrites in the area of interest. The animals were head restrained during image acquisition which took ∼15 min and immediately released to their original home cage, where they stayed until the next imaging and/or motor training sessions. For reimaging of the same region, thinned regions were identified based on maps of the brain vasculature and low-magnification stack (200 × 200 μm; 512 × 512 pixel) of fluorescently labeled neuronal processes.

Data Analysis of Spine Structural Plasticity.

All data analysis of spine remodeling was performed blind to treatment conditions as described previously (12). Dendritic branches were sampled within a 200 × 200 µm area imaged at 0 to 100 µm distance below the pia surface. The same dendritic segments were identified from 3D stacks taken at different time points with high image quality (ratio of signal to background noise > 4:1). The number and location of dendritic protrusions (protrusion lengths were more than one-third of the dendritic shaft diameter) were identified. Filopodia were identified as long, thin structures (larger than twice the average spine length, ratio of head diameter to neck diameter < 1.2:1 and ratio of length to neck diameter > 3:1). The remaining dendritic protrusions were classified as spines. No subtypes of spines were distinguished in our analysis. 3D stacks were used to ensure that tissue movements and rotation between imaging intervals did not influence spine/filopodium identification. Spines or filopodia were considered as identical between views if their positions were unchanged with respect to adjacent landmarks. Our quantitative analysis shows that we can measure the distance between two adjacent stable spines with an accuracy of 0.2 µm in 95% of the cases (2 SDs).

The percentage of spine/filopodium formation is presented as the number of spines/filopodia formed between the first and second view divided by the total number of spines observed at the first view. If a protrusion categorized as a filopodium changes to spine at a later time point, we would count this event as spine formation. If a protrusion changes from a spine to a filopodium, we would count the event as spine elimination.

The location of all protrusions along individual dendritic segments were extracted relative to the same starting point on the dendrite. Protrusions located at the same distance along the dendrite relative to its starting point but pointing at different directions in 3D space were determined to have the same location. In order to determine if new protrusions are formed randomly along individual dendritic segments, we calculated the closest distance between the location of new protrusion and the location of either 1) spines that existed at the first imaging session, 2) other new protrusions formed in response to the same training experience during the same time frame, and 3) new protrusions formed at different time frames in response to different training experiences (i.e., new protrusions formed at 0 to 24 h in response to training at time 0 h relative to new protrusions formed at 24 to 26 h in response to retraining at time 24 h). We then compared the distances measured from the data to distances measured from a simulation. We used custom-written Matlab codes to simulate the formation of new protrusions along the dendritic segments. The simulation was conducted under the assumption that new protrusions are formed independently and randomly along dendritic segments. We therefore randomly and independently generated new protrusions on dendritic segments according to the dendrites’ lengths and the number of new protrusions formed on each dendrite as measured in the data. We then calculated the closest distance between the location of the simulated new protrusion and the location of either 1) existing spines as observed in the data, 2) other simulated new protrusions as observed in the data, and 3) new protrusions formed at different time points as observed in the data. Finally, we repeated this process in the simulated data 1,000 times to produce the null distribution of closest distances along dendritic segments under the assumption of random new protrusion formation. We compared the cumulative probabilities of the closest distances measured and simulated using Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Additionally, we found the best model to fit the closest distance distribution (in a least-square sense) using Matlab Curve Fitting toolbox. We estimated the fit of the model to the data using R-square and the SSE statistics. Finally, we tested whether new protrusions were clustered at ≤0.2 µm with existing spines by comparing the percent of clustered new protrusions in the data with the simulated percent (Table 1).

We examined whether training-induced new spines were formed randomly onto dendritic segments by also comparing their location with the location of new spines formed in animals that did not receive training (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). Here, we defined the percentage of clustering as the number of new spines forming consecutively (with no prior interleaving existing spines) divided by the total number of new spines. We compared animals that did or did not receive training using the Mann–Whitney U test.

In SI Appendix, Fig. S3, we classified the sibling branch of the same L5 pyramidal neuron with higher spine formation as a “high-formation branch” (HFB) and the other as a “low-formation branch” (LFB). We then examined whether posttraining sleep facilitates clustered spine and filopodium formation on HFB or LFB.

In Figs. 1 B and C, 2B, and 3G, for image display we manually removed fluorescent structures near and out of the focal plane of the dendrites of interest from the image stacks using Adobe Photoshop. The modified image stacks were then projected to generate two-dimensional images and adjusted for contrast and brightness.

EEG/EMG Recording and Analysis.

Between imaging sessions, EEG/EMG was recorded with band pass setting of 0.1 to 100 Hz and digitized at 10 KHz. EEG/EMG data were visually scored for the states of wake and sleep. Wake state was identified by lower amplitude and higher frequency (>10 Hz) of EEG activity and medium to high muscle activity. Rapid eye movement (REM) sleep was identified by lower amplitude and higher frequency (>10 Hz) of EEG activity and low muscle activity. Non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep was identified by higher amplitude and lower frequency (<10 Hz) of EEG activity and low muscle activity.

Imaging Dendritic Spine Calcium Activity and Structural Plasticity in Awake, Head-Restrained Mice.

Genetically encoded calcium indicator GCaMP7 slow (s) and the fluorescent protein tdTomato were used for imaging calcium and structure simultaneously in single L5 pyramidal neurons in the M1 [at 0.2 mm anterior to bregma and 1.2 mm lateral to midline (79)]. Recombinant adeno-associated viruses AAV9-CaMKII-Cre, AAV9-Flex-Syn-GCaMP7s, and AAV9-Flex-CAG-tdTomato were used to drive the expression of GCaMP7s and tdTomato in L5 pyramidal neurons [≥1 × 1013 (vg/mL) titer; Addgene]. AAV-CaMKII-Cre virus was diluted 1:12.5K-25K in artificial cerebrospinal fluid containing fast green dye (final concentration of 0.1%) to assist the viral transduction. This dilution was then combined with the other two viruses so that the final solution was composed of 80% GCaMP7s, ∼17% tdTomato, and the rest was diluted Cre. This viral combination allowed for sparse double labeling of pyramidal neurons, with usually one to two pyramidal neurons labeled within the imaging field of view. Sparse expression ensures correct identification of fluorescence signals for both structure and calcium and is especially important for the identification of fluorescence signals from small spines and filopodia structures. Viral delivery into M1 was done via intracranial neonatal injection (80). Specifically, mice at postnatal day (P) 2 were anesthetized by hypothermia before injection. Following cessation of movement, 200 to 300 nL viral solution was injected intracranially using a glass microelectrode with a beveled tip. The injection site was located two-thirds of the distance between lambda and the confluence of sinuses to a depth of 300 to 500 µm below the pia surface. Following successful injections fast green dye was visible and retained within the cortex. After injection, pups were placed on a warm heating pad until they regained normal color and resumed movement and then returned to their mothers. About 4 wk after viral injection, L5 pyramidal neurons were imaged using two-photon microscopy.

For simultaneous calcium and structure imaging, a circular craniotomy (1.0 to 1.5 mm diameter) was made above the M1 following implantation of the head holder (as described in imaging of dendritic spine plasticity for Thy1-YFP animals). The craniotomy was covered with a round glass coverslip (World Precision Instruments, coverslips, 5 mm diameter) custom to the size of the bone removed and glued to the skull, as previously described (12, 77).

Mice were head restrained in the imaging apparatus on top of the custom-built free-floating treadmill. Before imaging, mice were habituated to the imaging/treadmill apparatus (same as Thy1-YFP animals). A two-photon microscope (Bruker) equipped with a Ti:Sapphire laser (MaiTai DeepSee Spectra Physics) tuned to 920 nm was used to acquire images (25× water immersion lens, N.A. = 1.05). Image acquisition was performed using Bruker PrairieView version 5.4 software. First, we scanned the imaging field of view to map the dendrites and determine successful double labeling of GCaMP7 and tdTomato. We followed the dendrites from their tip in layer 1, down to their nexus and all the way down to the soma to make sure they originated from a L5 pyramidal neuron. Animals in which double labeling was not successful and/or was not restricted to L5 were used for other experiments or discarded. Second, we collected two to three stacks of image planes (100 × 100 μm; 512 × 512 pixel, or 154 × 154 μm; 640 × 640 pixel) centered on the dendrites of the labeled neuron within a depth of 80 µm from the pial surface. Then, we acquired timelapse images during forward running treadmill training at two to four focal planes (100 to 130 × 100 to 130 μm; 380 to 490 × 380 to 490 pixel, variability was to maximize dendritic coverage versus image resolution) at frame rate of 3.6 Hz. We imaged a total of 5 min of treadmill training per focal plane within the first ∼20 min of treadmill training. Mice then received the remaining of their treadmill training (60 min in total) and were released back to their home cage. About 7 h later, mice were brought back to the imaging apparatus and reimaged to detect structural changes.

Data Analysis of Calcium Activity and Structural Plasticity.

Structural changes and protrusion locations were extracted similarly to that in Thy1-YFP animals across the full length of the dendrites, regardless of specific focal planes imaged during the treadmill training. Calcium activity and structural plasticity were extracted and analyzed blind to one another by two different experimentalists and were then matched to determine activity relative to structural plasticity.

During running trials, the lateral movement of the images was typically less than 1 µm. Vertical movements were infrequent and minimized due to flexible belt design, two micrometal bars attached to the animal’s skull by dental acrylic, and a custom-built body support to minimize spinal cord movements generated by the hind limbs. All timelapse images from each individual field of view were motion corrected and referenced to a single template frame using cross-correlation image alignment [TurboReg plugin for ImageJ (81)]. Regions-of-interest (ROIs) corresponding to spines and apical tuft dendrites were selected manually in the green channel based on visually identifiable structures in the red channel. All the pixels inside the ROI were averaged to obtain a time-series fluorescence trace for each ROI. This process was done manually to overcome contamination of the signal in these small structures by nearby structures due to remaining small lateral movements of the images. Background fluorescence was calculated as the average over the fifth percentile pixel value per frame and subtracted from the time-series fluorescence traces. The baseline (F0) of the fluorescence trace was estimated by detecting inactive portions of the trace using an iterative procedure (77). The ΔF/F0 was calculated as ΔF/F0 = (F − F0) / F0 × 100%. We removed contributions to the spine calcium activity originating from the dendritic shaft calcium activity. We estimated the coefficients of the robust linear regression of the ΔF/F0 calculated for the spine versus the ΔF/F0 calculated for its parent dendrite. We multiplied the ΔF/F0 of the dendrite by the slope of the fitted regression line and subtracted this scaled version of dendritic activity from the ΔF/F0 calculated for the spine to obtain a shaft independent spine calcium signal.

For each spine, we identified calcium transients from their ΔF/F0 signal during treadmill training and created activity transient traces. Transients were defined if the ΔF/F0 signal crossed a threshold of 1.96 times the error around the mean (>1.96 SD of the ΔF/F0 signal, equivalent to 95% of a normal distribution). The start and end times of the transients were defined as the times when the derivative of the ΔF/F0 signal outside the threshold crossing was below 25%. We then created the activity transient traces in which all data points apart from detected transients were set to zero, and all data points at detected transients were set to their original ΔF/F0 values. Finally, for each spine we determined the peak activity value and the total integrated activity from their activity transient traces.

Statistics.

All the image and data analysis described in the paper were performed using toolboxes and custom code in NIH Image J and MathWorks MATLAB software. Data are presented as average ± SEM unless otherwise noted. Sample sizes were chosen to ensure adequate power with the statistical tests while minimizing the number of animals used in compliance with ethical guidelines. We used Mann–Whitney U test to compare two groups and Kruskal–Wallis test to compare more than two groups. Kruskal–Wallis tests were followed by Tukey–Kramer test for multiple comparisons. We used Kolmogorov–Smirnov test to compare the cumulative sum of protrusions’ location distances. All tests were conducted as two-sided tests. Significance level was determined at 5%.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council (RGC/ECS 27103715, RGC/GRF 17128816, RGC/GRF 17102120 to C.S.W.L.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC/General Program 31571031 to C.S.W.L.), the Health and Medical Research Fund (HMRF 03143096 to C.S.W.L.), Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (2018B030332001), and Shenzhen Science and Technology Innovation Funds (JCYJ20180504165435326, JCYJ 20180302150304250 to Y.B.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2114856118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Bhatt D. H., Zhang S., Gan W. B., Dendritic spine dynamics. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 71, 261–282 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yuste R., Bonhoeffer T., Morphological changes in dendritic spines associated with long-term synaptic plasticity. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24, 1071–1089 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buonomano D. V., Merzenich M. M., Cortical plasticity: From synapses to maps. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 21, 149–186 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang G., Pan F., Gan W. B., Stably maintained dendritic spines are associated with lifelong memories. Nature 462, 920–924 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu T., et al. , Rapid formation and selective stabilization of synapses for enduring motor memories. Nature 462, 915–919 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma L., et al. , Experience-dependent plasticity of dendritic spines of layer 2/3 pyramidal neurons in the mouse cortex. Dev. Neurobiol. 76, 277–286 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters A. J., Chen S. X., Komiyama T., Emergence of reproducible spatiotemporal activity during motor learning. Nature 510, 263–267 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reiner B. C., Dunaevsky A., Deficit in motor training-induced clustering, but not stabilization, of new dendritic spines in FMR1 knock-out mice. PLoS One 10, e0126572 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fu M., Yu X., Lu J., Zuo Y., Repetitive motor learning induces coordinated formation of clustered dendritic spines in vivo. Nature 483, 92–95 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hayashi-Takagi A., et al. , Labelling and optical erasure of synaptic memory traces in the motor cortex. Nature 525, 333–338 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li W., Ma L., Yang G., Gan W. B., REM sleep selectively prunes and maintains new synapses in development and learning. Nat. Neurosci. 20, 427–437 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang G., et al. , Sleep promotes branch-specific formation of dendritic spines after learning. Science 344, 1173–1178 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chklovskii D. B., Mel B. W., Svoboda K., Cortical rewiring and information storage. Nature 431, 782–788 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters A. J., Liu H., Komiyama T., Learning in the rodent motor cortex. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 40, 77–97 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Seibt J., Frank M. G., Primed to sleep: The dynamics of synaptic plasticity across brain states. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 13, 2 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tononi G., Cirelli C., Sleep and the price of plasticity: From synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron 81, 12–34 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feld G. B., Born J., Sculpting memory during sleep: Concurrent consolidation and forgetting. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 44, 20–27 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang G., Gan W. B., Sleep contributes to dendritic spine formation and elimination in the developing mouse somatosensory cortex. Dev. Neurobiol. 72, 1391–1398 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maret S., Faraguna U., Nelson A. B., Cirelli C., Tononi G., Sleep and waking modulate spine turnover in the adolescent mouse cortex. Nat. Neurosci. 14, 1418–1420 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havekes R., et al. , Sleep deprivation causes memory deficits by negatively impacting neuronal connectivity in hippocampal area CA1. eLife 5, e13424 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gisabella B., Scammell T., Bandaru S. S., Saper C. B., Regulation of hippocampal dendritic spines following sleep deprivation. J. Comp. Neurol. 528, 380–388 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Spano G. M., et al. , Sleep deprivation by exposure to novel objects increases synapse density and axon-spine interface in the hippocampal CA1 region of adolescent mice. J. Neurosci. 39, 6613–6625 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Vivo L., et al. , Ultrastructural evidence for synaptic scaling across the wake/sleep cycle. Science 355, 507–510 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diering G. H., et al. , Homer1a drives homeostatic scaling-down of excitatory synapses during sleep. Science 355, 511–515 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miyamoto D., Marshall W., Tononi G., Cirelli C., Net decrease in spine-surface GluA1-containing AMPA receptors after post-learning sleep in the adult mouse cortex. Nat. Commun. 12, 2881 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chauvette S., Seigneur J., Timofeev I., Sleep oscillations in the thalamocortical system induce long-term neuronal plasticity. Neuron 75, 1105–1113 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torrado Pacheco A., Bottorff J., Gao Y., Turrigiano G. G., Sleep promotes downward firing rate homeostasis. Neuron 109, 530–544.e6 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hengen K. B., Torrado Pacheco A., McGregor J. N., Van Hooser S. D., Turrigiano G. G., Neuronal firing rate homeostasis is inhibited by sleep and promoted by wake. Cell 165, 180–191 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donlea J. M., Thimgan M. S., Suzuki Y., Gottschalk L., Shaw P. J., Inducing sleep by remote control facilitates memory consolidation in Drosophila. Science 332, 1571–1576 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frank M. G., Cantera R., Sleep, clocks, and synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. 37, 491–501 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Frank M. G., Issa N. P., Stryker M. P., Sleep enhances plasticity in the developing visual cortex. Neuron 30, 275–287 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ziv N. E., Smith S. J., Evidence for a role of dendritic filopodia in synaptogenesis and spine formation. Neuron 17, 91–102 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Portera-Cailliau C., Pan D. T., Yuste R., Activity-regulated dynamic behavior of early dendritic protrusions: Evidence for different types of dendritic filopodia. J. Neurosci. 23, 7129–7142 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Korobova F., Svitkina T., Molecular architecture of synaptic actin cytoskeleton in hippocampal neurons reveals a mechanism of dendritic spine morphogenesis. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 165–176 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zuo Y., Lin A., Chang P., Gan W. B., Development of long-term dendritic spine stability in diverse regions of cerebral cortex. Neuron 46, 181–189 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fiala J. C., Feinberg M., Popov V., Harris K. M., Synaptogenesis via dendritic filopodia in developing hippocampal area CA1. J. Neurosci. 18, 8900–8911 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lohmann C., Bonhoeffer T., A role for local calcium signaling in rapid synaptic partner selection by dendritic filopodia. Neuron 59, 253–260 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Govindarajan A., Kelleher R. J., Tonegawa S., A clustered plasticity model of long-term memory engrams. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 575–583 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lai C. S. W., Adler A., Gan W. B., Fear extinction reverses dendritic spine formation induced by fear conditioning in the mouse auditory cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 9306–9311 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frank A. C., et al. , Hotspots of dendritic spine turnover facilitate clustered spine addition and learning and memory. Nat. Commun. 9, 422 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeBello W., Zito Z., “Within a Spine’s reach” in The Rewiring Brain: A Computational Approach to Structural Plasticity in the Adult Brain, Ooyen A. V., Butz-Ostendorf M., Eds. (Elsevier, 2017), chap. 14, pp. 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kastellakis G., Poirazi P., Synaptic clustering and memory formation. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 12, 300 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Poirazi P., Mel B. W., Impact of active dendrites and structural plasticity on the memory capacity of neural tissue. Neuron 29, 779–796 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Triesch J., Vo A. D., Hafner A. S., Competition for synaptic building blocks shapes synaptic plasticity. eLife 7, e37836 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Royer S., Paré D., Conservation of total synaptic weight through balanced synaptic depression and potentiation. Nature 422, 518–522 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes S. J., et al. , Deprivation-induced homeostatic spine scaling in vivo is localized to dendritic branches that have undergone recent spine loss. Neuron 96, 871–882.e5 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bourne J. N., Harris K. M., Coordination of size and number of excitatory and inhibitory synapses results in a balanced structural plasticity along mature hippocampal CA1 dendrites during LTP. Hippocampus 21, 354–373 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Grutzendler J., Kasthuri N., Gan W. B., Long-term dendritic spine stability in the adult cortex. Nature 420, 812–816 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zuo Y., Yang G., Kwon E., Gan W. B., Long-term sensory deprivation prevents dendritic spine loss in primary somatosensory cortex. Nature 436, 261–265 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Majewska A., Sur M., Motility of dendritic spines in visual cortex in vivo: Changes during the critical period and effects of visual deprivation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 16024–16029 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richards D. A., et al. , Glutamate induces the rapid formation of spine head protrusions in hippocampal slice cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 6166–6171 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ueda Y., Hayashi Y., PIP3 regulates spinule formation in dendritic spines during structural long-term potentiation. J. Neurosci. 33, 11040–11047 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Weinhard L., et al. , Microglia remodel synapses by presynaptic trogocytosis and spine head filopodia induction. Nat. Commun. 9, 1228 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harvey C. D., Yasuda R., Zhong H., Svoboda K., The spread of Ras activity triggered by activation of a single dendritic spine. Science 321, 136–140 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Murakoshi H., Wang H., Yasuda R., Local, persistent activation of Rho GTPases during plasticity of single dendritic spines. Nature 472, 100–104 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gilestro G. F., Tononi G., Cirelli C., Widespread changes in synaptic markers as a function of sleep and wakefulness in Drosophila. Science 324, 109–112 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aton S. J., et al. , Mechanisms of sleep-dependent consolidation of cortical plasticity. Neuron 61, 454–466 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cary B. A., Turrigiano G. G., Stability of neocortical synapses across sleep and wake states during the critical period in rats. eLife 10, e66304 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huber R., Born J., Sleep, synaptic connectivity, and hippocampal memory during early development. Trends Cogn. Sci. 18, 141–152 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dailey M. E., Smith S. J., The dynamics of dendritic structure in developing hippocampal slices. J. Neurosci. 16, 2983–2994 (1996). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunaevsky A., Blazeski R., Yuste R., Mason C., Spine motility with synaptic contact. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 685–686 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tashiro A., Dunaevsky A., Blazeski R., Mason C. A., Yuste R., Bidirectional regulation of hippocampal mossy fiber filopodial motility by kainate receptors: A two-step model of synaptogenesis. Neuron 38, 773–784 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Knott G. W., Holtmaat A., Wilbrecht L., Welker E., Svoboda K., Spine growth precedes synapse formation in the adult neocortex in vivo. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 1117–1124 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Nägerl U. V., Köstinger G., Anderson J. C., Martin K. A., Bonhoeffer T., Protracted synaptogenesis after activity-dependent spinogenesis in hippocampal neurons. J. Neurosci. 27, 8149–8156 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Marrs G. S., Green S. H., Dailey M. E., Rapid formation and remodeling of postsynaptic densities in developing dendrites. Nat. Neurosci. 4, 1006–1013 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jontes J. D., Smith S. J., Filopodia, spines, and the generation of synaptic diversity. Neuron 27, 11–14 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Portera Cailliau C., Yuste R., On the function of dendritic filopodia [in Spanish]. Rev. Neurol. 33, 1158–1166 (2001). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yuste R., Bonhoeffer T., Genesis of dendritic spines: Insights from ultrastructural and imaging studies. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 5, 24–34 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Engert F., Bonhoeffer T., Dendritic spine changes associated with hippocampal long-term synaptic plasticity. Nature 399, 66–70 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Toni N., Buchs P. A., Nikonenko I., Bron C. R., Muller D., LTP promotes formation of multiple spine synapses between a single axon terminal and a dendrite. Nature 402, 421–425 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mattison H. A., Popovkina D., Kao J. P., Thompson S. M., The role of glutamate in the morphological and physiological development of dendritic spines. Eur. J. Neurosci. 39, 1761–1770 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maletic-Savatic M., Malinow R., Svoboda K., Rapid dendritic morphogenesis in CA1 hippocampal dendrites induced by synaptic activity. Science 283, 1923–1927 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kwon H. B., Sabatini B. L., Glutamate induces de novo growth of functional spines in developing cortex. Nature 474, 100–104 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Govindarajan A., Israely I., Huang S. Y., Tonegawa S., The dendritic branch is the preferred integrative unit for protein synthesis-dependent LTP. Neuron 69, 132–146 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schuman E. M., Dynes J. L., Steward O., Synaptic regulation of translation of dendritic mRNAs. J. Neurosci. 26, 7143–7146 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cichon J., Gan W. B., Branch-specific dendritic Ca(2+) spikes cause persistent synaptic plasticity. Nature 520, 180–185 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Adler A., Zhao R., Shin M. E., Yasuda R., Gan W. B., Somatostatin-expressing interneurons enable and maintain learning-dependent sequential activation of pyramidal neurons. Neuron 102, 202–216.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yang G., Pan F., Chang P. C., Gooden F., Gan W. B., Transcranial two-photon imaging of synaptic structures in the cortex of awake head-restrained mice. Methods Mol. Biol. 1010, 35–43 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Tennant K. A., et al. , The organization of the forelimb representation of the C57BL/6 mouse motor cortex as defined by intracortical microstimulation and cytoarchitecture. Cereb. Cortex 21, 865–876 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kim J. Y., et al. , Viral transduction of the neonatal brain delivers controllable genetic mosaicism for visualising and manipulating neuronal circuits in vivo. Eur. J. Neurosci. 37, 1203–1220 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thevenaz P., Ruttimann U. E., Unser M., A pyramid approach to subpixel registration based on intensity. IEEE Trans. Image Process 7, 27–41 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or SI Appendix.