Significance

This study reveals a mechanism for effector perception by a plant NLR immune receptor that contains an integrated domain (ID) that mimics an authentic effector target. The Arabidopsis immune receptors RRS1 and RPS4 detect the Pseudomonas syringae pv. pisi secreted effector AvrRps4 via a WRKY ID in RRS1. We used structural biology to reveal the mechanisms of AvrRps4C–WRKY interaction and demonstrated that this binding is essential for effector recognition in planta. Our analysis revealed features of the WRKY ID that mediate perception of structurally distinct effectors from different bacterial pathogens. These insights could enable engineering NLRs with novel recognition specificities, and enhance our understanding of how effectors interact with host proteins to promote virulence.

Keywords: disease resistance, effector proteins, virulence, protein structure, plant biology

Abstract

Plants use intracellular nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and leucine-rich repeat (LRR)–containing immune receptors (NLRs) to detect pathogen-derived effector proteins. The Arabidopsis NLR pair RRS1-R/RPS4 confers disease resistance to different bacterial pathogens by perceiving the structurally distinct effectors AvrRps4 from Pseudomonas syringae pv. pisi and PopP2 from Ralstonia solanacearum via an integrated WRKY domain in RRS1-R. How the WRKY domain of RRS1 (RRS1WRKY) perceives distinct classes of effector to initiate an immune response is unknown. Here, we report the crystal structure of the in planta processed C-terminal domain of AvrRps4 (AvrRps4C) in complex with RRS1WRKY. Perception of AvrRps4C by RRS1WRKY is mediated by the β2-β3 segment of RRS1WRKY that binds an electronegative patch on the surface of AvrRps4C. Structure-based mutations that disrupt AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interactions in vitro compromise RRS1/RPS4-dependent immune responses. We also show that AvrRps4C can associate with the WRKY domain of the related but distinct RRS1B/RPS4B NLR pair, and the DNA-binding domain of AtWRKY41, with similar binding affinities and how effector binding interferes with WRKY–W-box DNA interactions. This work demonstrates how integrated domains in plant NLRs can directly bind structurally distinct effectors to initiate immunity.

Plants coevolve with their pathogens, resulting in extensive genetic variation in host immune receptor and pathogen virulence factor (effector) repertoires (1). To enable host colonization, pathogenic microbes deliver effector proteins into host cells that suppress host immune responses and elevate host susceptibility by manipulating host physiology (2, 3). Plants have evolved surveillance mechanisms to detect and then activate defenses that combat pathogens, and detect host-translocated effectors via nucleotide-binding domain (NBD) and leucine-rich repeat (LRR)–containing receptors (NLRs) (4). NLR genes are highly diverse, showing both copy-number and presence/absence of polymorphisms, and different alleles can exhibit distinct effector recognition specificities (5, 6). As described by the gene-for-gene model, plant NLRs usually recognize a single effector (7). However, NLRs capable of responding to multiple effectors are known (5, 8, 9).

NLRs typically contain an N-terminal Toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) or coiled-coil (CC) domain, a central NBD (NB-ARC [NBD shared with APAF-1, various R proteins, and CED-4]), and a C-terminal LRR domain (6). In addition to these canonical domains, some NLRs have evolved to carry integrated domains that mimic effector virulence targets and facilitate immune activation by directly binding effectors (10–15). Interestingly, integrated domain-containing NLRs (NLR-IDs) usually function with a paired helper NLR, which is required for immune signaling (10, 16).

The Arabidopsis NLR pair RRS1-R/RPS4 is a particularly interesting NLR-ID/NLR pair that confers resistance to bacterial pathogens Pseudomonas syringae and Ralstonia solanacearum, and also to a fungal pathogen (Colletotrichum higginsianum) where the effector is unknown (17–20). RRS1-R contains an integrated WRKY domain near its C terminus (RRS1WRKY), which interacts with two structurally distinct type III secreted bacterial effectors, AvrRps4 from P. syringae pv. pisi and PopP2 from R. solanacearum (13, 14, 21, 22). The RRS1WRKY domain may mimic the DNA-binding domain of WRKY transcription factors (TFs), the putative virulence targets of AvrRps4 and PopP2, to enable immune perception of these effectors (13). Two alleles of RRS1 have been identified that differ in the length of the C-terminal extension after the WRKY domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). RRS1-R, from the accession Ws-2, has a 101–amino acid C-terminal extension beyond the end of the WRKY domain, and can perceive AvrRps4 and PopP2, while RRS1-S from Col-0, which perceives AvrRps4 but not PopP2, is likely a derived allele with a premature stop codon, and has only an 18–amino acid C-terminal extension (23). Most Arabidopsis ecotypes also carry a paralogous and genetically linked RRS1B/RPS4B NLR pair, which only perceives AvrRps4 (24). RRS1B/RPS4B share a similar domain architecture with RRS1/RPS4, including 60% sequence identity in the integrated WRKY domain.

AvrRps4 is proteolytically processed in planta to produce a 133–amino acid N-terminal fragment (AvrRps4N) and an 88–amino acid C-terminal fragment (AvrRps4C) (25, 26). Previous studies have highlighted the role of AvrRps4C in triggering RRS1/RPS4-dependent immune responses (25, 26). AvrRps4N has been reported to potentiate immune signaling from AvrRps4C (27, 28). PopP2 is sequence and structurally distinct from AvrRps4 and has an acetyltransferase activity that is likely related to its role in virulence. The structural basis of PopP2 perception by RRS1WRKY has been determined (29), but how RRS1WRKY binds AvrRps4C and whether this is via a shared or different interface to PopP2 is unknown.

Here, we determined the structural basis of AvrRps4C recognition by the integrated WRKY ID of RRS1. The recognition of AvrRps4C is mediated by the β2-β3 segment of RRS1WRKY, the same region used to bind PopP2. This segment interacts with surface-exposed acidic residues of AvrRps4C. Structure-informed mutagenesis at the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interface identifies AvrRps4 residues required for protein–protein interactions in vitro and in planta and AvrRps4 perception and immune responses. Residues mediating the interaction of AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY are conserved in both the RRS1BWRKY and the DNA-binding domain of WRKY TFs, and AvrRps4C mutants that prevent interaction with RRS1WRKY also disrupt binding to AtWRKY41. This supports the hypothesis that the RRS1WRKY mimics host WRKY TFs through a shared effector-binding mechanism. We also show that AvrRps4C prevents the interaction of RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41 with W-box DNA, most likely via steric blocking, at the same WRKY domain site acetylated by PopP2.

Results

AvrRps4C Interacts with the Integrated WRKY Domain of RRS1 In Vitro.

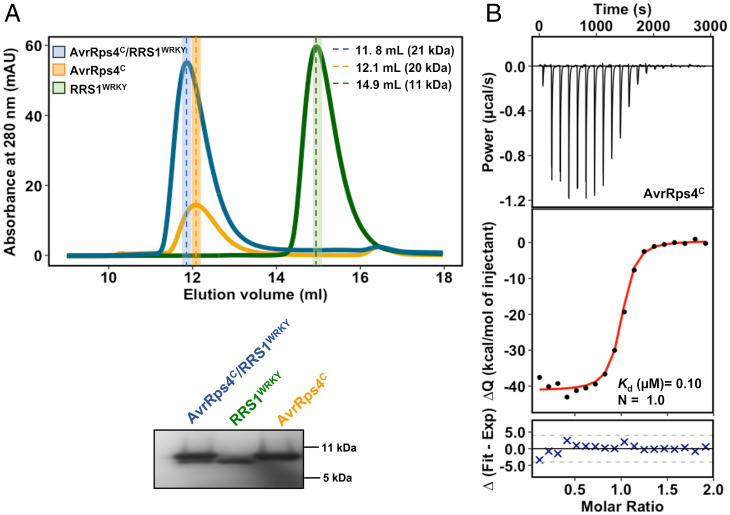

To investigate how AvrRps4C interacts with the RRS1WRKY domain, constructs comprising residues 134 to 221 of AvrRps4C (the in planta processed C-terminal fragment) and residues 1194 to 1273 of RRS1-R (corresponding to the RRS1WRKY domain) were separately expressed in Escherichia coli and proteins were purified via a combination of immobilized metal-affinity chromatography (IMAC) via 6×His tags and gel filtration (Superdex 75 26/60 and Superdex S75 16/60) (see SI Appendix, Materials and Methods for full details). We qualitatively assessed the interaction of purified AvrRps4C with RRS1WRKY using analytical gel filtration chromatography. Individually, the proteins displayed well-separated elution profiles. RRS1WRKY eluted at a volume (Ve) of 14.9 mL and AvrRps4C eluted at a Ve of 12.1 mL (Fig. 1A). Following incubation of a 1:1 molar ratio of the proteins, we observed a new elution peak with an earlier Ve of 11.8 mL, and a lack of absorption peaks for the separate proteins (Fig. 1A). This demonstrates complex formation in vitro and suggests a 1:1 stoichiometry of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex.

Fig. 1.

AvrRps4C interacts with the WRKY domain of RRS1 in vitro. (A) Analytical gel filtration traces (using a Superdex 75 10/300 column) for AvrRps4C alone (gold), RRS1WRKY alone (green), and AvrRps4C with RRS1WRKY (blue) with sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gels of relevant fractions. An equimolar ratio of AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY was used for the analysis. AvrRps4C runs as a dimer in vitro. Poor absorbance for AvrRps4C at 280 nm is due to its low molar extinction coefficient. (B) ITC titrations of AvrRps4C with RRS1WRKY. (B, Upper) Raw processed thermogram after baseline correction and noise removal. (B, Lower) The experimental binding isotherm obtained for the interaction of AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY together with the global fitted curves (displayed in red) were obtained from three independent experiments using AFFINImeter software (61). Kd and binding stoichiometry (N) were derived from fitting to a 1:1 binding model.

We then determined the binding affinities of the interaction using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC). Titration of AvrRps4C into a solution of RRS1WRKY resulted in an exothermic binding isotherm with a fitted dissociation equilibrium constant (Kd) of 0.103 μM (Fig. 1B) and stoichiometry of 1:1. The thermodynamic parameters of the interaction are given in SI Appendix, Table S1. As RRS1WRKY may be a mimic of WRKY TFs, we explored the binding kinetics of AvrRps4C with AtWRKY41 and AtWRKY70 by ITC [previous reports have shown that AvrRps4 interacts with these proteins in yeast two-hybrid assay and by in planta coimmunoprecipitation (13, 30)]. We chose AtWRKY41 for further study as this protein expressed and purified stably from E. coli. AvrRps4C interacted with AtWRKY41 with a Kd of 0.02 μM, and with similar thermodynamic parameters as RRS1WRKY (SI Appendix, Fig. S2 and Table S1).

Crystal Structure of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY Complex.

To reveal the molecular basis of the AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY interaction, we coexpressed the proteins in E. coli, purified the complex, and obtained crystals that diffracted with 2.65-Å resolution at the Diamond Light Source (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods). The crystal structure of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex was solved by molecular replacement using the structure of RRS1WRKY (from the PopP2–RRS1WRKY complex, Protein Data Bank [PDB] ID code 5W3X) and AvrRps4C (PDB ID code 4B6X) as models (SI Appendix, Materials and Methods). X-ray data collection, refinement, and validation statistics are shown in SI Appendix, Table S2.

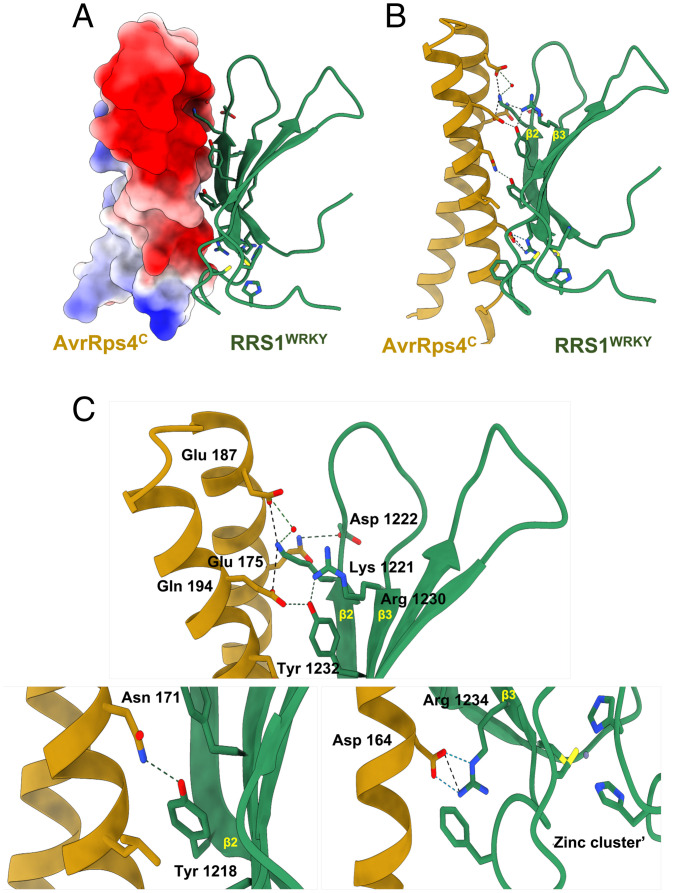

The structure comprises a 1:1 complex of AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY (Fig. 2A), which supports the 1:1 binding model in ITC. Overall, AvrRps4C adopts the same antiparallel α-helical CC structure in both free [PDB ID code 4B6X (26)] and complexed forms, with an rmsd of 0.66 Å over 59 Cα atoms (SI Appendix, Fig. S3A). Also, RRS1WRKY adopts a conventional WRKY domain fold [rmsd of 2.03 Å over 61 Cα atoms compared with AtWRKY1, PDB ID code 2AYD (31)] comprising a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet (β2 to β5) stabilized by a zinc ion (C2H2 type). Comparison of RRS1WRKY in the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY and PopP2–RRS1WRKY complex (PDB ID code 5W3X) structures reveals high conformational similarity, with an rmsd of 1.81 Å over 64 Cα atoms. The characteristic WRKY sequence signature motif WRKYGQK maps to the β2-strand of RRS1WRKY and is directly involved in contacting AvrRps4C (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Figs. S3A and S4). The same surface, including the β2-β3 strands of RRS1WRKY, forms contacts with PopP2 in the PopP2–RRS1WRKY complex (29) (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), and mutants at this surface showed it to be essential for PopP2 recognition.

Fig. 2.

Structure of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex. (A) Electrostatic surface representation of AvrRps4C in the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY crystal structure displaying a prominent negative patch in AvrRps4 at the interacting interface. (B) Schematic representation of AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY, highlighting interfacing residues. AvrRps4C is shown in gold cartoon and RRS1WRKY is shown in green with surface-exposed side chains as sticks. (C) Close-up view of the interactions of AvrRps4C with the β2-β3 segment of RRS1WRKY. Hydrogen bonds are shown as dashed lines, and water molecules are depicted as red spheres. The Zn2+ ion is also displayed.

The AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY–Binding Interface Is Dominated by Electrostatic and Polar Interactions.

The total interface area buried in the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex is 591.8 Å2, encompassing 12.3% (589.7 Å2) and 11.9% (593.9 Å2) of the total accessible surface areas of the effector and integrated domain, respectively [as calculated by PDBePISA (32); full details are given in SI Appendix, Table S3]. The binding interface between AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY is largely formed by residues from the β2-β3 strand of RRS1WRKY, which present a positive surface patch that interacts with acidic residues on the surface of AvrRps4C (Fig. 2A, SI Appendix, Fig. S3B, and Movie S1). The interaction between the β2-segment of RRS1WRKY, which harbors the WRKYGQK motif, and AvrRps4C includes hydrogen bonds and/or salt-bridge interactions involving Tyr1218 and Lys1221 of RRS1WRKY and AvrRps4 Glu175, Glu187, and Asn171. Notably, the side chain of RRS1WRKY Lys1221 protrudes into an acidic cleft on the surface of AvrRps4C to contact the side chains of both AvrRps4 Glu175 and Glu187 (Fig. 2 B and C and Movie S1). The OH atom of RRS1WRKY Tyr1218 forms a hydrogen bond with the ND2 atom of AvrRps4 Asn171 (Fig. 2 B and C). Additional intermolecular contacts are formed by the β2-β3 loop of RRS1WRKY involving the backbone carbonyl oxygen and nitrogen of Asp1222, which form hydrogen bonds with the side chains of AvrRps4 Asn190 and Gln194. The complex between AvrRps4C and RRS1WRKY is further stabilized by the β3-strand of RRS1WRKY that forms hydrogen bonds and salt-bridge interactions via side chains of RRS1WRKY Arg1230, Tyr1232, and Arg1234 to AvrRps4 Glu175 and Asp164 (Fig. 2 B and C). A detailed interaction summary is provided in SI Appendix, Table S4.

Structure-Based Mutations in AvrRps4C Perturb Binding to RRS1WRKY In Vitro.

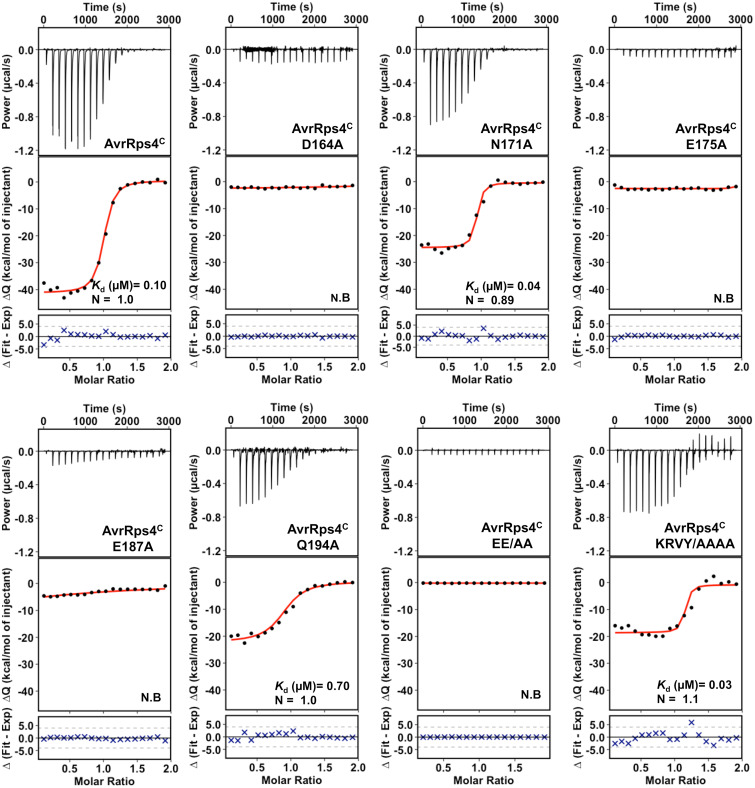

To evaluate the contribution of residues at the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interface to complex formation in vitro, we generated six structure-guided mutants in AvrRps4C (native amino acid to Ala) and tested the effect on protein interactions by ITC. Each AvrRps4C mutant was purified from E. coli under the same conditions as for the wild-type protein, and proper folding was evaluated by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). ITC titrations were carried out as for the wild-type interactions. Individual ITC isotherms are shown in Fig. 3, and the thermodynamic parameters of the interactions are shown in SI Appendix, Table S1. We found that mutating AvrRps4 residues Asp164 (D164A), Glu175 (E175A), Glu187 (E187A), and double mutant Glu175/Glu187 (EE/AA) essentially abolished complex formation in vitro (Fig. 3). Mutations in residues Asn171 (N171A) and Gln194 (Q194A) retained binding to RRS1WRKY, with N171A displaying wild-type levels and Q194A showing an approximately sevenfold reduction in affinity. Besides structure-guided mutants, we also tested binding of an AvrRps4 quadruple mutant, carrying mutations in the N-terminal KRVY motif (KRVY/AAAA) [previously identified to be essential for the virulence activity and perception of AvrRps4 (25)], with RRS1WRKY. Unlike most interface mutants, the AvrRps4C KRVY/AAAA mutant retained wild type–like binding affinity with RRS1WRKY (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Structure-guided mutants of AvrRps4C at the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interface disrupt interaction with RRS1WRKY in vitro. ITC titrations of wild-type AvrRps4C and mutants with RRS1WRKY. (Upper) Raw processed thermograms after baseline correction and noise removal. (Lower) Experimental binding isotherms obtained for the interaction of AvrRps4C wild type and mutants with RRS1WRKY together with the global fitted curves (displayed in red) obtained from three independent experiments using AFFINImeter software (61). Kd was derived from fitting to a 1:1 binding model. N.B., nonbinding.

Since AvrRps4C binds RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41 with similar affinity (SI Appendix, Fig. S2), we tested the impact of the AvrRps4C EE/AA double mutant on the binding to AtWRKY41. We found that this mutant also abolishes interaction with AtWRKY41, suggesting the same AvrRps4-binding interface is shared with different WRKY proteins (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Structure-Based Mutations in AvrRps4 Prevent RRS1/RPS4-Mediated Cell Death in Nicotiana tabacum.

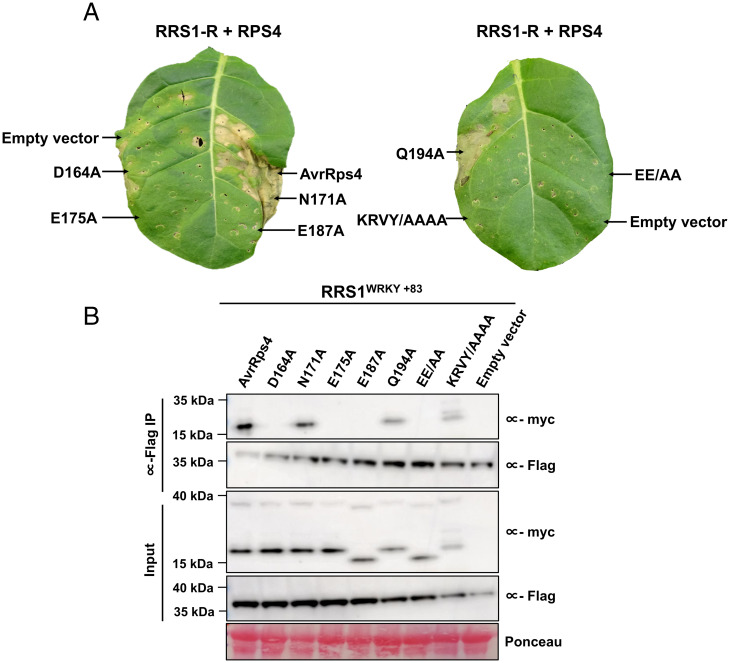

To validate the biological relevance of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interface observed in the crystal structure, we tested the effect of the AvrRps4C mutants above on RRS1-R/RPS4–mediated immunity by monitoring the cell-death response in N. tabacum. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression of wild-type AvrRps4 triggers a hypersensitive cell-death response (HR) 5 d post infiltration when coexpressed with RRS1-R/RPS4 (Fig. 4A). The previously characterized inactive AvrRps4 KRVY/AAAA mutant (25, 26) was used as a negative control. We found that AvrRps4 mutations at positions D164, E175, and E187 and the double mutant E175/E187 prevented RRS1-R/RPS4–dependent cell-death responses, consistent with their loss of binding to RRS1WRKY in vitro (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the N171A mutation, which retained its binding to RRS1WRKY in vitro, displayed wild type–like cell death–inducing activity, and Q194A with an approximately sevenfold reduction in RRS1WRKY affinity consistently exhibited a weaker cell-death response. Expression of all mutants was confirmed by immunoblotting (Fig. 4B). In addition to RRS1-R/RPS4, we also explored the effect of AvrRps4 structure-based mutations on RRS1-S/RPS4–dependent cell death in N. tabacum (SI Appendix, Figs. S1 and S6A). We found that AvrRps4 variants elicited similar immune responses when transiently coexpressed with RRS1-S/RPS4 or RRS1-R/RPS4.

Fig. 4.

Structure-guided mutants of AvrRps4 at the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interface compromise RRS1-R/RPS4–mediated cell-death responses and in vivo binding in Nicotiana. (A) Representative leaf images showing RRS1-R/RPS4–mediated cell-death response to wild-type structure-guided mutants of AvrRps4. Agroinfiltration assays were performed in 4- to 5-wk-old N. tabacum leaves, and cell death was assessed at 4 d post infiltration. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP) of RRS1-RWRKY+83 (6×His/3×FLAG-tagged) with AvrRps4 and variants (4×myc-tagged) in N. benthamiana. Blots show protein accumulations in total protein extracts (input) and immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-FLAG magnetic beads when probed with appropriate antisera. Empty vector was used as a control. The experiment was repeated at least three times, with similar results.

Loss of Cell Death in N. tabacum Correlates with the Loss of Binding to RRS1WRKY In Vivo.

To determine whether loss of RRS1-R/RPS4–mediated HR in transient assays correlates with the loss of AvrRps4 binding to RRS1WRKY in vivo as well as in vitro, we performed coimmunoprecipitation assays using full-length C-terminal 4×myc-tagged AvrRps4 constructs and C-terminal 6×His/3×FLAG-tagged constructs of RRS1-RWRKY+83 (equivalent to RRS1-D5/6R as defined in ref. 23). Wild-type AvrRps4 associates with RRS1-RWRKY+83 in its in planta processed form (Fig. 4B). Consistent with the cell-death phenotype and in vitro binding data, no association between AvrRps4 mutants D164A, E175A, E187A, or EE/AA and RRS1WRKY+83 was detected (Fig. 4B). Further, we observed wild-type levels of association of AvrRps4 N171A with RRS1WRKY+83, while AvrRps4 Q194A appeared to coimmunoprecipitate weakly. The AvrRps4 KRVY/AAAA mutant displayed wild type–like binding affinity toward RRS1WRKY+83, as observed previously (26).

Structure-Guided Mutations in AvrRps4 Prevent HR in Arabidopsis.

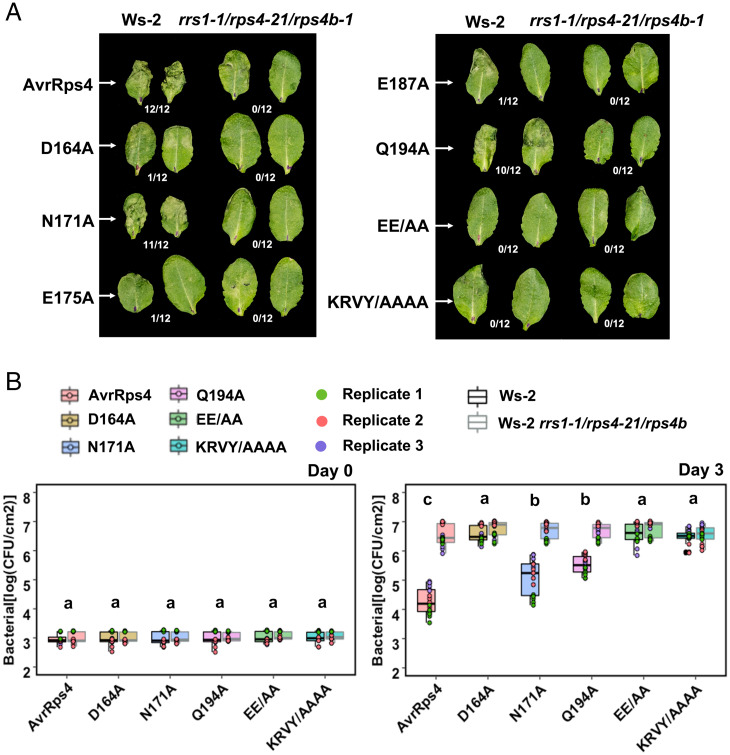

Next, we investigated the impact of AvrRps4 structure-guided mutations on the activation of RRS1-R/RPS4–dependent immune responses using HR assays in Arabidopsis. Constructs carrying full-length AvrRps4 wild type and mutants, flanked by a 126-bp native AvrRps4 promoter, were delivered into plant cells by infiltration using the Pf0-EtHAn (Pseudomonas fluorescens effector-to-host analyzer, hence Pf0) system (33). HR assays used Arabidopsis ecotype Ws-2 (encoding RRS1-R/RPS4 and RPS4B/RRS1B) and Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1 (RRS1-R/RPS4/RPS4B triple-knockout) lines and were scored at 20 h post infiltration. Pf0 carrying wild-type AvrRps4 triggered HR in Ws-2, but not in Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1, as previously reported (13, 26). AvrRps4 KRVY/AAAA, an HR inactive mutant, was used as a negative control (26). The structure-guided mutants AvrRps4 D164A, E175A, E187A, and EE/AA all showed a complete loss of HR in Ws-2, with AvrRps4 Q194A showing a weaker HR and N171A showing a wild type–like phenotype (Fig. 5A). None of the AvrRps4 variants triggered HR in Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1 (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5.

Structure-guided mutants of AvrRps4 compromise RRS1-R/RPS4–dependent recognition specificities and restriction of bacterial growth in Arabidopsis. (A) HR assay in different Arabidopsis accessions using P. fluorescens Pf0-1 secreting AvrRps4 wild type and structure-guided mutants. Constructs were delivered to the Arabidopsis Ws-2 and rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1 knockout background and HR was recorded 20 h post infiltration. Fraction refers to the number of leaves showing HR of 12 randomly inoculated leaves. This experiment was repeated at least three times with similar results. (B) In planta bacterial growth assays of Pto DC3000 secreting AvrRps4 wild type and mutant constructs. Bacterial suspensions with OD600 = 0.001 were pressure-infiltrated into the leaves of 4- to 5-wk-old Arabidopsis plants. Values are plotted from three independent experiments (denoted in different colors). Statistical significance of the values was calculated by one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey honestly significant difference analysis. Letters above the data points denote significant differences (P < 0.05). A detailed statistical summary can be found in SI Appendix, Table S5. CFU, colony forming unit.

In addition to Ws-2, we also performed a parallel set of experiments in Arabidopsis ecotype Col-0 (which encodes the RRS1-S allele) and the Col-0 rrs1-3/rrs1b-1 (RRS1-S/RRS1B double-knockout) line. Overall, we observed a weaker HR toward AvrRps4 wild type and mutants in Col-0 in comparison with Ws-2. Nevertheless, a similar pattern of HR phenotypes was observed in Col-0 compared with Ws-2, and none of the AvrRps4 variants triggered HR in the Col-0 rrs1-3/rrs1b-1 line (SI Appendix, Fig. S6B). The pattern of HR phenotypes conferred by the AvrRps4 interface mutants further validates the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY structure and the role of these residues in recognition of AvrRps4 by the RRS1/RPS4 receptor pair.

Loss of HR Correlates with Bacterial Growth in Arabidopsis.

Having demonstrated the role of AvrRps4 interface residues in effector-triggered HR in Arabidopsis, we next investigated their effects on bacterial growth. We performed bacterial growth assays on Arabidopsis ecotypes Ws-2, Col-0, Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1, and Col-0 rrs1-3/rrs1b-1 using the P. syringae pv. tomato (Pto) DC3000 strain carrying AvrRps4 wild type or structure-based mutants. Since both the single mutants AvrRps4 E175A and E187A displayed the same impaired HR as the double AvrRps4 EE/AA mutant in previous assays, we focused on AvrRps4 EE/AA only for this assay. Bacterial growth was scored at 3 d post infection. Pto DC3000 carrying wild-type AvrRps4 displayed reduced growth on Ws-2 when compared with the mutant background (Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1), presumably due to the activation of RRS1-R/RPS4–dependent immunity (Fig. 5B). The effector mutants AvrRps4 D164A, EE/AA, and KRVY/AAAA, which displayed a complete loss of HR in Ws-2, showed a severe or complete lack of restriction of bacterial growth in Ws-2 (Fig. 5B). Pto DC3000:AvrRps4 Q194A and Pto DC3000:AvrRps4 N171A showed reduced bacterial growth (but not full restriction) when compared with wild-type AvrRps4, even though they displayed a similar cell-death phenotype in N. tabacum (albeit weaker for AvrRps4 Q194A) and HR in Arabidopsis (Figs. 4A and 5A). All the Pto DC3000:AvrRps4 variants tested displayed indistinguishable bacterial growth in the RRS1-R/RPS4 loss-of-function line (Fig. 5B). Finally, all the Pto DC3000:AvrRps4 variants displayed similar bacterial growth profiles in the Col-0 and Col-0 rrs1-3/rrs1b-1 line when compared with Ws-2 and Ws-2 rrs1-1/rps4-21/rps4b-1 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6C).

The RRS1B/RPS4B Immune Receptor Pair Displays Similar Recognition Specificities toward AvrRps4 Variants as RRS1/RPS4.

In addition to RRS1/RPS4, the RRS1B/RPS4B pair can confer recognition of AvrRps4 in Arabidopsis (24). Sequence alignment revealed an overall 60% amino acid identity of the integrated WRKY domains from RRS1 and RRS1B, with the WRKYGQK motif and all residues interfacing with AvrRps4C conserved (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). To explore AvrRps4 recognition by RRS1B/RPS4B, we performed ITC titrations of RRS1BWRKY with wild-type AvrRps4C in vitro. We found that RRS1BWRKY binds to AvrRps4C three times more weakly than RRS1WRKY (SI Appendix, Fig. S7), possibly due to subtle changes imposed by residues outside the direct binding interface. When comparing the binding kinetics with the strength of immune responses in planta, we observed a weaker RRS1B/RPS4B-dependent HR to AvrRps4 compared with RRS1/RPS4. Nonetheless, both NLR pairs displayed a similar profile of immune responses toward the AvrRps4 structure-guided mutants in transient cell-death assays and in Arabidopsis HR assays (SI Appendix, Fig. S7).

AvrRps4C Interferes with WRKY–W-Box DNA Interactions.

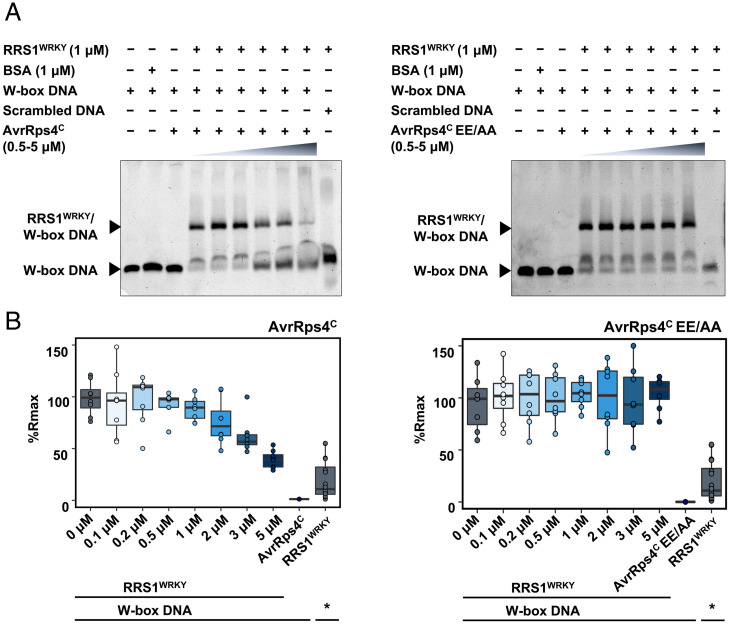

To regulate gene expression, WRKY TFs bind to specific W-box DNA motifs in the promoters of their target genes (34–36). Intriguingly, the majority of the AvrRps4-interacting residues are conserved within the DNA-binding domain of WRKY TFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 and Movie S2) and are indispensable for DNA binding (34). To test if AvrRps4 interferes with the W-box DNA-binding activity of RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41, we preincubated increasing concentrations of AvrRps4C and the AvrRps4C EE/AA mutant (as a negative control) and studied their effect on the DNA-binding capacity of RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41 using both electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA)– and surface plasmon resonance (SPR)–based assays. We found that the interaction of RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41 with W-box DNA was reduced after preincubation with increasing concentrations of AvrRps4C but not the AvrRps4C EE/AA mutant (Fig. 6 and SI Appendix, Figs. S8–S10), revealing that AvrRps4C interferes with WRKY binding to W-box DNA.

Fig. 6.

AvrRps4 interferes with W-box DNA binding by the RRS1WRKY domain. (A) EMSA of DNA binding by RRS1WRKY following preincubation of increasing concentrations of AvrRps4C or AvrRps4C EE/AA mutant. Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used as a negative control for W-box DNA binding. Scrambled DNA was used as a negative control to test the specificity of RRS1WRKY to W-box DNA. The experiment was repeated three times with similar results. (B) An SPR ReDCaT assay was performed using W-box and scrambled DNA (as a negative control). Percentage of normalized response (% Rmax) of RRS1WRKY binding to W-box DNA and scrambled DNA (denoted by an asterisk) immobilized on a ReDCaT SPR chip. Titrations were performed following preincubation of 2 μM RRS1WRKY with increasing concentrations of AvrRps4C wild type and AvrRps4C EE/AA mutant. The experiment was performed in eight replicates (each dot represents one replicate).

Discussion

Despite recent advances, structural knowledge of how diverse integrated domains in plant NLRs perceive pathogen effectors is limited. Here, we investigated how the integrated WRKY domain of the Arabidopsis NLR RRS1 binds to the Pseudomonas effector AvrRps4, and how this underpins RRS1/RPS4-dependent immunity in planta. Further, through this work, we gained insights into interfaces in the RRS1WRKY domain that are crucial for perception of two structurally unrelated effectors from distinct bacterial pathogens, which may have implications for NLR integrated domain engineering.

Transcriptional reprogramming upon NLR activation is well-established as an early immune response in plants (37–39), and direct interactions between NLRs and TFs have been reported (40–44). WRKY TFs are important molecular players in the regulation of plant growth and development and abiotic and biotic stresses (35, 36, 45). Typically, WRKY TFs target genes by binding W-box DNA in promoters, via a signature amino acid motif, WRKYGQK, to either promote or repress transcription (34, 46–48). As WRKY TFs play an important role in plant immunity, it is unsurprising that they are often found as integrated domains in NLR immune receptors (49), supporting the hypothesis that pathogen effectors enhance virulence by targeting WRKY TFs. Therefore, understanding how effectors bind to WRKY integrated domains may inform how effector/WRKY binding promotes disease. The structure of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex reveals that the effector directly interacts with the DNA-binding WRKYGQK motif, likely rendering it unavailable for binding to DNA (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 and Movie S2). AvrRps4C binds to AtWRKY41 with similar thermodynamic parameters to RRS1WRKY, and interface mutants that prevent AvrRps4C interaction with RRS1WRKY prevent interaction with AtWRKY41, supporting the hypothesis that AvrRps4C binds different WRKY proteins via a similar interface. WRKY TFs bind W-box DNA sequences in the promoters of their target genes. We used EMSAs and SPR assays to observe how the interaction of AvrRps4C with RRS1WRKY or AtWRKY41 affects the binding of these proteins to a generic W-box DNA sequence. Preincubation of RRS1WRKY and AtWRKY41 with increasing amounts of AvrRps4C reduced DNA-binding activity, whereas preincubation with AvrRps4 EE/AA showed no significant difference (Fig. 6 and SI Appendix, Figs. S8–S10). WRKY domain residues interacting with AvrRps4C are well-conserved in these TFs (SI Appendix, Fig. S11), suggesting that AvrRps4 could interfere with and sterically block DNA binding of multiple WRKY TFs, thus promoting virulence. In addition to WRKY TFs, a recent publication suggests AvrRps4 can interact with BTS (nucleus-located Fe sensor BRUTUS) domains to affect pathogen colonization (50). Understanding whether these functions are related requires further investigation.

Comparing the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY structure with that of PopP2–RRS1WRKY (29) reveals an overlapping binding site for the effectors, primarily mediated by the β2-β3 segment of the WRKY domain (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 and Movie S2). The second lysine of the WRKYGQK motif, Lys1221, is acetylated by PopP2, abolishing the affinity of the WRKY domain for W-box DNA (13, 14, 29). Intriguingly, this acetylation event also abolished the association of AvrRps4C with RRS1WRKY (13), highlighting the important role of this interface in mediating the association of RRS1WRKY with both effectors. It also highlights the likely shared role of these effectors in preventing interaction of WRKY domains with DNA as their virulence activity, either via enzymatic modification or steric blocking.

Studies with the NLR pair Pik from rice have shown that the strength of effector binding to integrated domains in vitro can correlate with immune responses in planta (51–53). Of the AvrRps4 mutants we tested to validate the RRS1WRKY interface, all except N171A and Q194A prevented binding in vitro (by ITC) and in planta (by coimmunoprecipitation), and these did not give cell death in Nicotiana species when coexpressed with either RRS1-R/RPS4 or RRS1-S/RPS4. Further, they did not give HR or restrict bacterial growth in Arabidopsis Ws-2 or Col-0 ecotypes (except for a partial restriction of bacterial growth for the D164A mutation in the Col-0 background). The N171A mutant retained the same level of binding as wild type in vitro, and displayed the same in planta phenotypes, although restriction of bacterial growth in Arabidopsis was reduced compared with wild type in both Ws-2 and Col-0 ecotypes. Finally, the Q194A mutant showed a reduced binding in vitro (approximately sevenfold compared with wild type) but maintained an HR in Arabidopsis as well as displaying a restriction of bacterial growth in Arabidopsis, albeit reduced compared with wild type. Interestingly, this mutant consistently showed a qualitative reduction in the intensity of cell death in Nicotiana. Taken together, these AvrRps4 mutations validate the complex with RRS1WRKY in that they prevent interaction in vitro and in planta, but they are not sufficient to determine whether strength of binding in vitro can directly correlate with in planta phenotypes. Further studies, including additional mutants, will be required to study this in the RRS1/RPS4 system.

Structural studies of singleton NLRs have shown that interactions between effectors and multiple domains within an NLR can be essential for activation (54–57). It is yet to be established whether this is also the case for effector perception involving paired NLRs with integrated domains, although the rice blast pathogen effector AVR-Pia immunoprecipitates with its sensor NLR Pia-2 (RGA5) when the integrated HMA domain has been deleted. However, this interaction does not promote immune responses in planta (58). Although unresolved in the structure of AvrRps4C alone, or in complex with RRS1WRKY, the N-terminal KRVY motif is known to be required for both the virulence activity of the effector and its perception by RRS1/RPS4 (25, 26). Here, we verified that the quadruple mutant AvrRps4 KRVY/AAAA retains interaction with RRS1WRKY at wild-type levels in vitro and in vivo, but did not trigger RRS1/RPS4-dependent responses in our in planta assays. This suggests that while binding of AvrRps4 to the RRS1WRKY domain is essential for immune activation, an additional interaction mediated by the N-terminal region of the effector to a region of RRS1 and/or RPS4 outside this domain is also required for initiation of defense. Further studies are required to determine how additional receptor domains outside of integrated domains in NLR-IDs contribute to receptor function.

The Arabidopsis NLR pair RRS1B/RPS4B perceives AvrRps4, but not PopP2 (24). Phylogenetically, the RRS1 WRKY belongs to group III of the WRKY superfamily, whereas RRS1BWRKY is grouped into group IIe (14, 24, 48). Here we found that AvrRps4C binds RRS1BWRKY with threefold lower affinity and RRS1B/RPS4B shows a similar pattern of recognition specificity in planta but with reduced phenotypes compared with RRS1/RPS4. A full investigation addressing why AvrRps4 shows differential interaction strength and phenotypes between RRS1 and RRS1B is beyond the scope of this work, but will be a direction for future research.

The unique ability of RRS1/RPS4 to perceive two effectors that differ both in sequence and structure, via the same integrated domain, highlights the potential for engineering of sensor NLRs to recognize diverse effectors. Recently, the range of rice blast pathogen effectors recognized by the integrated HMA domain of Pia-2 (RGA5) has been expanded by molecular engineering (58). However, this expanded recognition was toward structurally related effectors and may not be via a shared interface. Further, although cell-death responses were observed in Nicotiana benthamiana, the engineered NLR was not able to deliver an expanded disease resistance profile in transgenic rice. This suggests we still require a better understanding of how NLR-IDs interact with effectors, and their partner helper NLRs, to enable bespoke engineering of disease resistance.

Materials and Methods

Gene Cloning.

For in vitro studies, the gene fragments of AvrRps4C (Gly134 to Gln221), RRS1WRKY (Ser1194 to Thr1273), RRS1BWRKY (Asn1164 to Thr1241), and AtWRKY41 (Thr125 to Ile204) were cloned in various pOPIN expression vectors using an in-fusion cloning strategy as described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

For transient assays in N. tabacum and N. benthamiana, domesticated genomic fragments encoding RRS1-R, RRS1-S, RRS1B, RPS4, and RPS4B were cloned into binary vector pICSL86977 under a 35S (CaMV) promoter with a C-terminal 6×His/3×FLAG tag using the Golden Gate assembly method as described (23). Similar cloning techniques were used to generate constructs expressing RRS1WRKY+83. Full-length AvrRps4 (P. syringae pv. pisi) was PCR-amplified from published constructs (13, 23, 26) and assembled with a C-terminal 4×myc tag in binary vector pICSL86977 under the control of the 35S (CaMV) promoter using the Golden Gate assembly method. DNA encoding each mutation was synthesized and cloned into pICSL86977 as described above.

For HR and bacterial growth assays in Arabidopsis, full-length AvrRps4 and variants were cloned into a Golden Gate–compatible pEDV3 vector with a C-terminal 4×myc tag.

Protein Production and Purification.

Plasmids expressing the in planta processed C-terminal fragment of AvrRps4 (AvrRps4C) and integrated WRKY domain of RRS1 (RRS1WRKY) were expressed in E. coli SHuffle cells. The proteins were purified via IMAC followed by size-exclusion chromatography. Purified fractions were pooled and concentrated to 15 mg/mL and used for further studies. Detailed procedures are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Crystallization and Structure Determination.

Crystals of the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex were obtained from a 1:1 solution of 15 mg/mL protein with 0.8 M potassium sodium tartrate tetrahydrate, 0.1 M sodium Hepes (pH 7.5). Diffraction data were collected at the Diamond Light Source on the i03 beamline and processed in the P61/522 space group. The structure was determined by molecular replacement using the model of a monomer of AvrRps4C (PDB ID code 4B6X) and the RRS1WRKY from the PopP2–RRS1WRKY complex (PDB ID code 5W3X) as the search model. Further details are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods. X-ray data collection and refinement statistics are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S2.

In Vitro Protein–Protein Interaction Studies.

AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY complex formation in vitro was studied using analytical gel filtration chromatography and ITC. The effect of structure-guided mutations on the AvrRps4C–RRS1WRKY interaction in vitro was investigated using ITC as described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Transient Cell-Death Assays and Coimmunoprecipitation Studies.

Agrobacterium-mediated transient cell-death assays were performed in N. tabacum and coimmunoprecipitation assays were performed in N. benthamiana. Detailed information concerning plant materials, growth conditions, plasmid construction, and immunoblotting are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Arabidopsis HR Assays and Bacterial Growth Assays.

Bacterial strains P. fluorescens Pf0-EtHAn and Pto DC3000 were used for HR or in planta bacterial growth assays, respectively. The Arabidopsis accessions Ws-2 and Col-0 were used as wild type for all the assays in this study. Further details about plant materials, growth conditions, plasmid construction and mobilization, pathogen infection assays, and bacterial growth assays are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

WRKY–W-Box DNA Interaction: EMSA.

Complementary single-stranded DNA fragments encoding the W-box DNA sequence (forward strand: 5′-CGCCTTTGACCAGCGC-3′) were synthesized by IDT. EMSAs were performed using a Cy3-labeled W-box DNA probe in a reaction buffer containing 10 mM Tris⋅Cl (pH 7.5), 50 mM KCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, and 5% glycerol as described in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

WRKY–W-Box DNA Interaction: SPR Assay.

Complementary single-stranded DNA fragments encoding the W-box DNA sequence were synthesized by IDT. For SPR assays, the forward strand encoded the W-box DNA sequence (5′-CGCCTTTGACCAGCGC-3′) while the complementary reverse strand added an extra 20-bp ReDCaT sequence (5′-CCTACCCTACGTCCTCCTGC-3′) to complement the linker DNA added to the SA chip. The double-stranded DNA was then diluted to a working concentration of 1 μM. SPR measurements were performed at 25 °C using the reusable DNA capture technique (ReDCaT) as described (59, 60) and using a Biacore 8K System (Cytiva). Further details are provided in SI Appendix, Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the European Research Council (Proposal 669926, “ImmunityByPairDesign”); the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC) Norwich Research Park Biosciences Doctoral Training Partnership, UK (Grant BB/M011216/1); the UKRI BBSRC, UK (Grants BB/P012574 and BBS/E/J/000PR9795); and the BBSRC Future Leader Fellowship (Grant BB/R012172/1). We thank Julia Mundy and Professor David Lawson from the John Innes Centre (JIC) Biophysical Analysis and X-Ray Crystallography platform for their support with CD spectroscopy, protein crystallization, and X-ray data collection; Andrew Davies and Phil Robinson from JIC Scientific Photography for their help with leaf imaging; and Dr. Tung Lee for advice on EMSAs. We also thank Dr. Kee Hoon Sohn for helpful suggestions for triparental mating and other members of the M.J.B. and J.D.G.J. laboratories for discussions.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2113996118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.

References

- 1.Dodds P. N., Rathjen J. P., Plant immunity: Towards an integrated view of plant-pathogen interactions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 11, 539–548 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mukhi N., Gorenkin D., Banfield M. J., Exploring folds, evolution and host interactions: Understanding effector structure/function in disease and immunity. New Phytol. 227, 326–333 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan M., Seto D., Subramaniam R., Desveaux D., Oh, the places they’ll go! A survey of phytopathogen effectors and their host targets. Plant J. 93, 651–663 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones J. D. G., Dangl J. L., The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323–329 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bentham A. R., et al. , A molecular roadmap to the plant immune system. J. Biol. Chem. 295, 14916–14935 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones J. D. G., Vance R. E., Dangl J. L., Intracellular innate immune surveillance devices in plants and animals. Science 354, aaf6395 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flor H. H., Current status of the gene-for-gene concept. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 9, 275–296 (1971). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barragan A. C., Weigel D., Plant NLR diversity: The known unknowns of pan-NLRomes. Plant Cell 33, 814–831 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Duxbury Z., et al. , Pathogen perception by NLRs in plants and animals: Parallel worlds. BioEssays 38, 769–781 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cesari S., Bernoux M., Moncuquet P., Kroj T., Dodds P. N., A novel conserved mechanism for plant NLR protein pairs: The “integrated decoy” hypothesis. Front. Plant Sci. 5, 606 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nishimura M. T., Monteiro F., Dangl J. L., Treasure your exceptions: Unusual domains in immune receptors reveal host virulence targets. Cell 161, 957–960 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maqbool A., et al. , Structural basis of pathogen recognition by an integrated HMA domain in a plant NLR immune receptor. eLife 4, e08709 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sarris P. F., et al. , A plant immune receptor detects pathogen effectors that target WRKY transcription factors. Cell 161, 1089–1100 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le Roux C., et al. , A receptor pair with an integrated decoy converts pathogen disabling of transcription factors to immunity. Cell 161, 1074–1088 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cesari S., et al. , The rice resistance protein pair RGA4/RGA5 recognizes the Magnaporthe oryzae effectors AVR-Pia and AVR1-CO39 by direct binding. Plant Cell 25, 1463–1481 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adachi H., Derevnina L., Kamoun S., NLR singletons, pairs, and networks: Evolution, assembly, and regulation of the intracellular immunoreceptor circuitry of plants. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 50, 121–131 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huh S. U., et al. , Protein-protein interactions in the RPS4/RRS1 immune receptor complex. PLoS Pathog. 13, e1006376 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Narusaka M., Hatakeyama K., Shirasu K., Narusaka Y., Arabidopsis dual resistance proteins, both RPS4 and RRS1, are required for resistance to bacterial wilt in transgenic Brassica crops. Plant Signal. Behav. 9, e29130 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gassmann W., Hinsch M. E., Staskawicz B. J., The Arabidopsis RPS4 bacterial-resistance gene is a member of the TIR-NBS-LRR family of disease-resistance genes. Plant J. 20, 265–277 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hinsch M., Staskawicz B., Identification of a new Arabidopsis disease resistance locus, RPs4, and cloning of the corresponding avirulence gene, avrRps4, from Pseudomonas syringae pv. pisi. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 9, 55–61 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deslandes L., et al. , Physical interaction between RRS1-R, a protein conferring resistance to bacterial wilt, and PopP2, a type III effector targeted to the plant nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 8024–8029 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tasset C., et al. , Autoacetylation of the Ralstonia solanacearum effector PopP2 targets a lysine residue essential for RRS1-R-mediated immunity in Arabidopsis. PLoS Pathog. 6, e1001202 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y., et al. , Distinct modes of derepression of an Arabidopsis immune receptor complex by two different bacterial effectors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, 10218–10227 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saucet S. B., et al. , Two linked pairs of Arabidopsis TNL resistance genes independently confer recognition of bacterial effector AvrRps4. Nat. Commun. 6, 6338 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sohn K. H., Zhang Y., Jones J. D., The Pseudomonas syringae effector protein, AvrRPS4, requires in planta processing and the KRVY domain to function. Plant J. 57, 1079–1091 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sohn K. H., Hughes R. K., Piquerez S. J., Jones J. D. G., Banfield M. J., Distinct regions of the Pseudomonas syringae coiled-coil effector AvrRps4 are required for activation of immunity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 16371–16376 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Su J., et al. , The conserved arginine required for AvrRps4 processing is also required for recognition of its N-terminal fragment in lettuce. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 34, 270–278 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halane M. K., et al. , The bacterial type III-secreted protein AvrRps4 is a bipartite effector. PLoS Pathog. 14, e1006984 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Z.-M., et al. , Mechanism of host substrate acetylation by a YopJ family effector. Nat. Plants 3, 17115 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mukhtar M. S., et al. ; European Union Effectoromics Consortium, Independently evolved virulence effectors converge onto hubs in a plant immune system network. Science 333, 596–601 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Duan M.-R., et al. , DNA binding mechanism revealed by high resolution crystal structure of Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY1 protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1145–1154 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krissinel E., Henrick K., Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J. Mol. Biol. 372, 774–797 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thomas W. J., Thireault C. A., Kimbrel J. A., Chang J. H., Recombineering and stable integration of the Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae 61 hrp/hrc cluster into the genome of the soil bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Pf0-1. Plant J. 60, 919–928 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xu Y. P., Xu H., Wang B., Su X.-D., Crystal structures of N-terminal WRKY transcription factors and DNA complexes. Protein Cell 11, 208–213 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wani S. H., Anand S., Singh B., Bohra A., Joshi R., WRKY transcription factors and plant defense responses: Latest discoveries and future prospects. Plant Cell Rep. 40, 1071–1085 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X., Li C., Wang H., Guo Z., WRKY transcription factors: Evolution, binding, and action. Phytopathol. Res. 1, 13 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsuda K., Somssich I. E., Transcriptional networks in plant immunity. New Phytol. 206, 932–947 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ng D. W. K., Abeysinghe J. K., Kamali M., Regulating the regulators: The control of transcription factors in plant defense signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 19, 3737 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jacob F., et al. , A dominant-interfering camta3 mutation compromises primary transcriptional outputs mediated by both cell surface and intracellular immune receptors in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 217, 1667–1680 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhai K., et al. , RRM transcription factors interact with NLRs and regulate broad-spectrum blast resistance in rice. Mol. Cell 74, 996–1009.e7 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Townsend P. D., et al. , The intracellular immune receptor Rx1 regulates the DNA-binding activity of a Golden2-like transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 293, 3218–3233 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu F., et al. , NLR-associating transcription factor bHLH84 and its paralogs function redundantly in plant immunity. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1004312 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang C., et al. , Barley MLA immune receptors directly interfere with antagonistically acting transcription factors to initiate disease resistance signaling. Plant Cell 25, 1158–1173 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X., Inoue H., Hayashi N., Jiang C.-J., Takatsuji H., CC-NBS-LRR-type R proteins for rice blast commonly interact with specific WRKY transcription factors. Plant Mol. Biol. Report 34, 533–537 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jiang J., et al. , WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 59, 86–101 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamasaki K., et al. , Structural basis for sequence-specific DNA recognition by an Arabidopsis WRKY transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 7683–7691 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciolkowski I., Wanke D., Birkenbihl R. P., Somssich I. E., Studies on DNA-binding selectivity of WRKY transcription factors lend structural clues into WRKY-domain function. Plant Mol. Biol. 68, 81–92 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eulgem T., Rushton P. J., Robatzek S., Somssich I. E., The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 5, 199–206 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sarris P. F., Cevik V., Dagdas G., Jones J. D. G., Krasileva K. V., Comparative analysis of plant immune receptor architectures uncovers host proteins likely targeted by pathogens. BMC Biol. 14, 8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xing Y., et al. , Bacterial effector targeting of a plant iron sensor facilitates iron acquisition and pathogen colonization. Plant Cell 33, 2015–2031 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.De la Concepcion J. C., et al. , Polymorphic residues in rice NLRs expand binding and response to effectors of the blast pathogen. Nat. Plants 4, 576–585 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De la Concepcion J. C., et al. , Protein engineering expands the effector recognition profile of a rice NLR immune receptor. eLife 8, e47713 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maidment J. H. R., et al. , Multiple variants of the fungal effector AVR-Pik bind the HMA domain of the rice protein OsHIPP19, providing a foundation to engineer plant defense. J. Biol. Chem. 296, 100371 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin R., et al. , Structure of the activated ROQ1 resistosome directly recognizing the pathogen effector XopQ. Science 370, eabd9993 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma S., et al. , Direct pathogen-induced assembly of an NLR immune receptor complex to form a holoenzyme. Science 370, eabe3069 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang J., et al. , Ligand-triggered allosteric ADP release primes a plant NLR complex. Science 364, eaav5868 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J., et al. , Reconstitution and structure of a plant NLR resistosome conferring immunity. Science 364, eaav5870 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cesari S., et al. , Design of a new effector recognition specificity in a plant NLR immune receptor by molecular engineering of its integrated decoy domain. bioRxiv [Preprint] (2021). 10.1101/2021.04.24.441256 (Accessed 12 October 2021). [DOI]

- 59.Stevenson C. E. M., Lawson D. M., Analysis of protein-DNA interactions using surface plasmon resonance and a ReDCaT chip. Methods Mol. Biol. 2263, 369–379 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Stevenson C. E. M., et al. , Investigation of DNA sequence recognition by a streptomycete MarR family transcriptional regulator through surface plasmon resonance and X-ray crystallography. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 7009–7022 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Piñeiro Á., et al. , AFFINImeter: A software to analyze molecular recognition processes from experimental data. Anal. Biochem. 577, 117–134 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All study data are included in the article and/or supporting information.