Abstract

BACKGROUND

Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is a rare autoimmune blistering disease that usually presents in the second or third trimester, with an incidence of 1 per 50000 pregnancies. PG tends to recur with an earlier onset and a more severe course in subsequent pregnancies. Skin biopsy markers can be confirmed by direct immunofluorescence staining.

CASE SUMMARY

Our patient was diagnosed with PG at 8 mo of gestation with fresh bullous lesion marks on the abdomen and limbs. Termination of the pregnancy was performed by cesarean section at 37 + 4 wk of gestation. The patient delivered an infant weighing 3620 gm. The infant had urticaria-like and vesicular skin lesions and was diagnosed with PG. The patient was discharged on prednisolone and in a satisfactory condition. The infant was discharged after anti-inflammatory therapy for one week.

CONCLUSION

PG is a rarely reported disease, and 10% of newborns develop mild clinical symptoms consisting of urticaria-like or vesicular skin lesions. We intend to remind clinicians to consider this condition when a patient presents with such lesions so that treatment can be started early and neonatal morbidity can be taken into account.

Keywords: Pemphigoid gestationis, Pregnancy, Newborn, Pemphigus, Fluorescent antibody techniqu, Case report

Core Tip: Pemphigoid gestationis (PG) is a rarely reported disease, and 10% of newborns develop mild clinical symptoms consisting of urticaria-like or vesicular skin lesions. Our patient was diagnosed with PG at 8 mo of gestation and was performed by cesarean section at 37 + 4 wk of gestation. The infant had urticaria-like and vesicular skin lesions and was diagnosed with PG. We intend to remind clinicians to consider this condition when a patient presents with such lesions so that treatment can be started early and neonatal morbidity can be taken into account.

INTRODUCTION

Pemphigoid gestation (PG) is an autoimmune bullous disease that occurs during pregnancy or the puerperium[1]. The main clinical manifestations are tension blisters and bullae with urticaria-like plaques, accompanied by pruritus[2]. For approximately 14%-25% of patients in the postpartum period, menstrual periods and oral contraceptive drugs may induce or aggravate the disease[3]. PG can induce fetal growth restriction, premature delivery, and neonatal skin involvement. It has also been reported to cause low birth weight[4]. This disease is very rare, the clinical manifestation and laboratory examination results are similar to bullous pemphigoid, and the exact pathogenesis of PG has not been clarified.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

A 30-year-old female presented with pruritic edematous erythema for 2 wk.

History of present illness

A 30-year-old female presented with a 2-wk history of pruritic edematous erythema on the trunk and extremities during her 32nd week of pregnancy with no inducing factors. These symptoms have never occurred before. She also had no history of drug or food allergies. Soon after, small bullae and vesicles developed at the periphery of the erythema; these healed readily with residual pigmentation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pemphigoid gestationis on the abdomen and limbs.

History of past illness

The patient had no history of any previous disease.

Personal and family history

There was no family history of PG.

Physical examination

No mucosal lesions were observed. The Nikolsky sign was negative.

Laboratory examinations

Laboratory findings were normal, including hematocrit, urine analysis, hepatic and renal function, electrolytes, glycemia, anti-streptolysin and C-reactive protein.

Imaging examinations

Obstetric ultrasonography indicated no abnormality in the fetus.

FINAL DIAGNOSIS

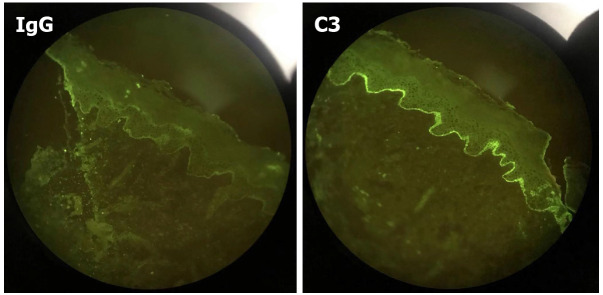

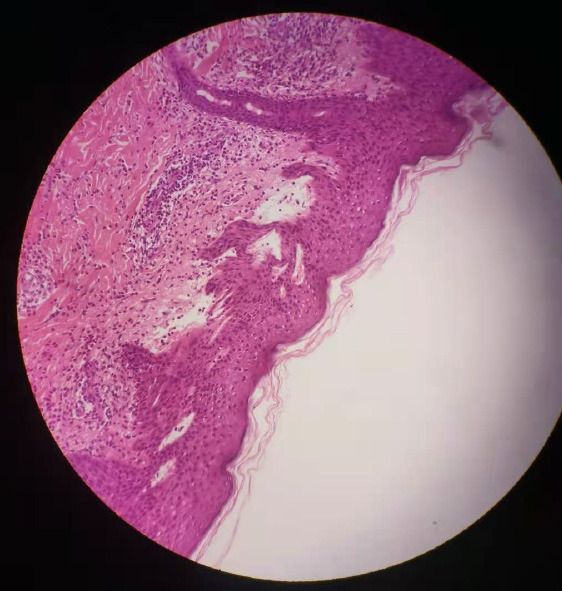

A clinical diagnosis of PG was made. This was supported by histology that showed a dermoepidermal blister with conspicuous eosinophils within the blister and in the papillary dermis. Further investigation identified that the skin biopsy showed subepidermal blister with eosinophils and lymphocytes within the cavity and in the superficial dermis (Figure 2). Direct immunofluorescence (DIF) showed linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone in the absence of IgG (Figure 3). Indirect immunofluorescence (IIF) was negative. Anti-BP180 was positive (90 normal range < 20 IU/mL), and anti-BP230 was negative. Thus, a diagnosis of PG was made.

Figure 2.

Skin with a sub-epidermal blister with eosinophils and lymphocytes within the cavity and in superficial dermis of pemphigoid gestationis in pregnancy (hematoxylin and eosin 100×).

Figure 3.

Linear deposition of C3 along the basement membrane zone with the absence of IgG (direct immunofluorescence) of pemphigoid gestationis in pregnancy.

TREATMENT

Prednisone was administered orally at a dose of 25 mg. Four weeks later, the prednisone was tapered to 20 mg gradually with no new lesions appearing. Many red spots and pigmentation were left on the body and limbs. During the pregnancy, regular prenatal visits were conducted to help to monitor the health of the patient and her baby.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

A multidisciplinary (obstetrics, dermatology, pathology, and neonatology) discussion was initiated during the patient’s late pregnancy (37 wk of pregnancy ) to determine the timing and method of delivery. For this patient with obstetrical factors (scarred uterus), a cesarean section at 37 + 4 wk of gestation was recommended. All the decisions were fully communicated with the patient and her family members. The Apgar score of the infant was 10 points, and the weight of the infant was 3620 g. After the placenta was delivered, a pathology specimen and umbilical cord blood was collected for examination. Prednisone was administered orally at a dose of 20 mg with no postoperative symptoms.

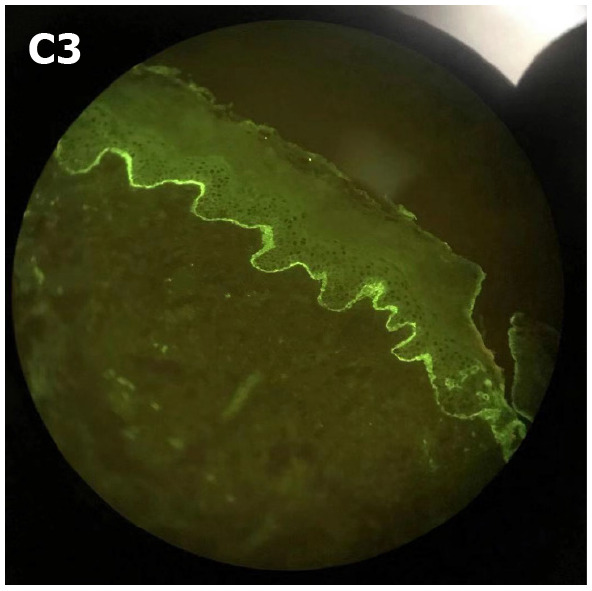

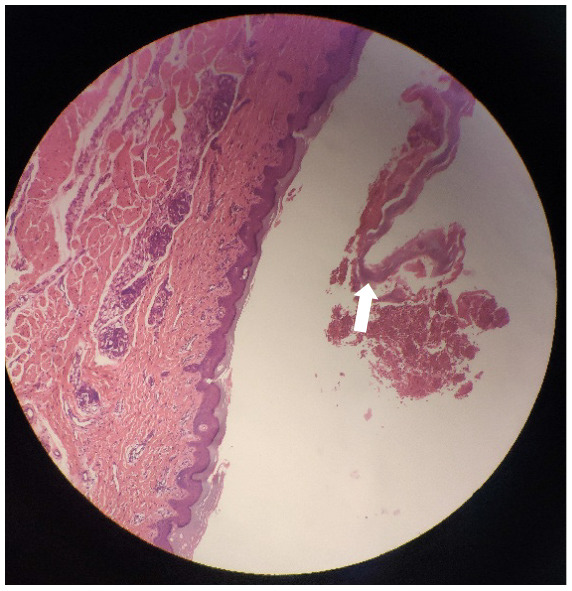

After examining the newborn, we found that the infant had vesicles and pustules on the palms and soles and erosions on the face and trunk (Figure 4). The skin biopsy showed another layer of epithelium over the normal epithelium with eosinophil and lymphocyte infiltration (Figure 5). DIF showed linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone, similar to that observed in the mother (Figure 6). Anti-BP180 was positive (100 normal range < 20 IU/mL). Anti-BP230 was negative.

Figure 4.

The first day after birth of the infant: Urticaria-like and vesicular skin lesions in neonatal pemphigoid gestationis.

Figure 5.

Skin biopsy of the infant showed another layer of epithelium over the normal epithelium with eosinophils and lymphocytes infiltration.

Figure 6.

Direct immunofluorescence of the infant showed linear deposits of C3 along the basement membrane zone similar to her mother.

Intensive monitoring and anti-infection treatment with penicillium legume intravenous injection for the infant were given. With local use of astringent and bactericidal drugs, the infant's rash gradually improved after 1 wk (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The seventh day after birth of the infant.

DISCUSSION

PG can be diagnosed in several ways: clinical symptoms, histological findings, DIF or IIF, and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. In our patient, DIF showed a linear deposit of C3 along the basement membrane zone in the absence of IgG. In a retrospective study of 25 cases of PG, fourteen patients presented the same DIF pattern as our patient[5]. Linear C3 deposits were observed in 100% of patients, and linear IgG deposits were observed in 25%-50% of patients, which indicated that C3 was pathognomonic to the disease[3]. This is the most important and commonly used PG detection method[6].

Treatment, which prevents the formation of herpes and controls itching symptoms depends on the stage and severity of the disease[7]. Topical glucocorticoids and orally administered antihistamine drugs can be used in mild cases. Oral corticosteroids (prednisone 0.5-1 mg/kg/d) or even intravenous gamma globulin may be used in severe cases[8]. PG is usually in remission for weeks to months after delivery, with a few cases extending to 2 years after delivery.

Most pregnant women with PG can deliver a healthy newborn after full-term pregnancy, via natural delivery or cesarean section for obstetric indications[9]. Due to the passive transfer of IgG1 antibody from mother to fetus, 10% of newborns with PG develop clinical symptoms, including urticaria or vesicular skin lesions, and have an increased risk of premature delivery and low birth weight[10]. There is no evidence of an association between medication regimens and fetal outcomes, and adverse pregnancy outcomes appear to be more closely associated with higher antibody titers in maternal serum and neonatal cord blood[11].

In this patient, multidisciplinary (obstetrics, dermatology, pathology, and neonatology) discussion was initiated during the patient’s late pregnancy (37 wk of pregnancy) to determine the timing and method of delivery. For this patient, who had obstetrical factors, a cesarean section at 37 + 4 wk of gestation pregnancy was recommended.

The newborn had vesicles and pustules on the palms and soles and erosions on the face and trunk. Her oral mucosa was not involved, and the skin lesions subsided rapidly without any proliferative changes. Therefore, the clinical manifestations of skin lesions in the infant were significantly different from those in the mothers. Additionally, anti-BP180 was positive (100 normal range < 20 IU/mL) and significantly higher than that of the mother. The diagnosis was confirmed by referencing the clinical history, histopathological examination and immunofluorescence examination of the mother and the infant. Neonatal pemphigoid is a self-healing disease, and most infants can resolve the skin lesions within 1 mo, so the treatment is mainly symptomatic treatment to prevent secondary infection of skin lesions. Short-term topical use of glucocorticoids may be considered for those with more frequent rashes. In this case, no special treatment was given to the infant, and the skin lesion subsided rapidly.

CONCLUSION

PG is a rarely reported disease, and 10% of newborns develop mild clinical symptoms consisting of urticaria-like or vesicular skin lesions[12]. We intend to remind clinicians to consider this condition when a patient presents with such lesions so that treatment can be started early and neonatal morbidity can be taken into account.

In the management of pregnant women with PG, a multidisciplinary team should be assembled quickly to develop a treatment plan; obstetricians, dermatologists, pediatricians, and pathologists should collaborate in the multidisciplinary approach to treating maternal, fetal, and neonatal complications.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine for their assistance with this research.

Footnotes

Informed consent statement: Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this report and any accompanying images.

Conflict-of-interest statement: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

CARE Checklist (2016) statement: The authors have read the CARE Checklist (2016), and the manuscript was prepared and revised according to the CARE Checklist (2016).

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review started: January 7, 2021

First decision: July 16, 2021

Article in press: October 20, 2021

Specialty type: Obstetrics and gynecology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Tolunay HE S-Editor: Zhang H L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang H

Contributor Information

Hai-Ning Jiao, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China.

Ye-Ping Ruan, Department of Dermatology, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China.

Yan Liu, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China.

Meng Pan, Department of Dermatology, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China.

Hui-Ping Zhong, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Rui-Jin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine, Shanghai 200025, China. zhp10392@rjh.com.cn.

References

- 1.Almeida FT, Sarabando R, Pardal J, Brito C. Pemphigoid gestationis successfully treated with intravenous immunoglobulin. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;2018 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-224346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kukkamalla RM, Bayless P. Pemphigoid Gestationis. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med. 2019;3:79–80. doi: 10.5811/cpcem.2018.11.39258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semkova K, Black M. Pemphigoid gestationis: current insights into pathogenesis and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2009;145:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2009.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Fouzan AW, Galadari I, Oumeish I, Oumeish OY. Herpes gestationis (Pemphigoid gestationis) Clin Dermatol. 2006;24:109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tani N, Kimura Y, Koga H, Kawakami T, Ohata C, Ishii N, Hashimoto T. Clinical and immunological profiles of 25 patients with pemphigoid gestationis. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172:120–129. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sävervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Pemphigoid gestationis: current perspectives. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2017;10:441–449. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S128144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sentürk S, Dilek N, Tekin YB, Colak S, Gündoğdu B, Güven ES. Pemphigoid gestationis in a third trimester pregnancy. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2014;2014:127628. doi: 10.1155/2014/127628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi CC, Wang SH, Charles-Holmes R, Ambros-Rudolph C, Powell J, Jenkins R, Black M, Wojnarowska F. Pemphigoid gestationis: early onset and blister formation are associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:1222–1228. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin L, Zeng X, Chen Q. Pemphigus and pregnancy. Analysis and summary of case reports over 49 years. Saudi Med J. 2015;36:1033–1038. doi: 10.15537/smj.2015.9.12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sävervall C, Sand FL, Thomsen SF. Dermatological Diseases Associated with Pregnancy: Pemphigoid Gestationis, Polymorphic Eruption of Pregnancy, Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy, and Atopic Eruption of Pregnancy. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:979635. doi: 10.1155/2015/979635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lehman JS, Mueller KK, Schraith DF. Do safe and effective treatment options exist for patients with active pemphigus vulgaris who plan conception and pregnancy? Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:783–785. doi: 10.1001/archderm.144.6.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roth MM. Pregnancy dermatoses: diagnosis, management, and controversies. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2011;12:25–41. doi: 10.2165/11532010-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]