Abstract

Background

Negatively charged procoagulant phospholipids, phosphatidylserine (PS) in particular, are vital to coagulation and expressed on the surface membrane of extracellular vesicles. No previous study has investigated the association between plasma procoagulant phospholipid clotting time (PPLCT) and future risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Objectives

To investigate the association between plasma PPLCT and the risk of incident VTE in a nested case‐control study.

Methods

We conducted a nested case‐control study in 296 VTE patients and 674 age‐ and sex‐matched controls derived from a general population cohort (The Tromsø Study 1994–2007). PPLCT was measured in platelet‐free plasma using a modified factor Xa‐dependent clotting assay. Logistic regression was used to estimate odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for VTE with PPLCT modelled as a continuous variable across quartiles and in dichotomized analyses.

Results

There was a weak inverse association between plasma PPLCT and risk of VTE per 1 standard deviation increase of PPLCT (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80–1.07) and when comparing those with PPLCT in the highest quartile (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.60–1.30) with those in the lowest quartile. Subjects with PPLCT >95th percentile had substantially lowered OR for VTE (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13–0.81). The inverse association was stronger when the analyses were restricted to samples taken shortly before the event. The risk estimates by categories of plasma PPLCT were similar for deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that high plasma PPLCT is associated with reduced risk of VTE.

Keywords: clotting, extracellular vesicles, phosphatidylserines, phospholipids, venous thromboembolism

Essentials.

Plasma procoagulant phospholipid (PPL) activity can be measured as PPL clotting time (PPLCT).

We investigated the association between PPLCT and risk of VTE in a nested case‐control study.

PPLCT above the 95th percentile was associated with lower risk of future VTE.

The association was stronger in analyses restricted to samples taken shortly before the VTE.

1. INTRODUCTION

Venous thromboembolism (VTE), encompassing deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE), is a common disease with an annual incidence of 1–2 per 1000 individuals. 1 , 2 VTE is associated with severe short‐ and long‐term complications, such as recurrent events, 3 postthrombotic syndrome, 4 post‐PE syndrome, 5 and death. 6 The incidence of VTE has been stable 7 or slightly increased during the past 2 decades, 8 , 9 and VTE has become a major economic burden and challenge to health care systems. 10 , 11 Therefore, there is a great need to identify novel biomarkers to improve risk stratification and unravel disease mechanisms to tailor preventive and treatment strategies with the long‐term goal to lower the incidence of the disease.

Phosphatidyl serine (PS) is a negatively charged phospholipid with procoagulant potential expressed at the surface of activated platelets and extracellular vesicles (EVs). 12 The presence of PS on the membrane surface facilitates the assembly of coagulation factors VII (FVII), FIX, and FX and prothrombin (FII), 13 and accelerates the activity of the tissue factor (TF):FVIIa complex by several orders of magnitude. 14 Furthermore, a strong relationship between plasma levels of PS‐positive EVs and procoagulant phospholipid (PPL) activity has been reported. 15 Hence, plasma PPL clotting time (PPLCT) may be considered as a measure of the potential to facilitate coagulation activation when blood is exposed to triggers of the coagulation system. Plasma PPLCT is the time to clot formation in seconds measured in platelet‐free plasma using a factor Xa‐dependent clotting assay. A high PPLCT indicates a low PPL activity.

Because most, 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 but not all 20 observational studies have reported elevated plasma levels of EVs in VTE, implying short plasma PPLCT, we hypothesized that prolonged PPLCT was associated with lowered risk of VTE. We therefore aimed to investigate the association between plasma PPLCT, measured by a modified factor Xa‐dependent clotting assay, and the risk of incident VTE in a nested case‐control study derived from the general population. In addition, we studied the effect of plasma procoagulant phospholipids on thrombin generation using the calibrated automated thrombinoscope (CAT) assay.

2. MATERIAL AND METHODS

2.1. Study population

The Tromsø Study is a large prospective single‐center population‐based cohort study with repeated health surveys of inhabitants of Tromsø, Norway. 21 The study participants were recruited from the fourth survey (1994–1995) of the Tromsø Study. All inhabitants aged 25 years and older living in the municipality of Tromsø were invited to participate, and 77% of those invited participated (n = 27,158). The participants were followed from the date of inclusion until an adjudicated incident VTE event, migration, death, or end of follow‐up (September 1, 2007). All first lifetime events of VTE occurring among the participants in this period were identified using the hospital discharge diagnosis registry, the autopsy registry, and the radiology procedure registry from the University Hospital of North Norway, which is the sole provider of diagnostic radiology and treatment of VTE in the Tromsø area. Trained personnel adjudicated and recorded each VTE by extensively reviewing medical records. The identification and adjudication process of VTEs has previously been described in detail. 22 In short, the adjudication criteria for VTE were presence of signs and symptoms of DVT or PE combined with objective confirmation by radiological procedures, which resulted in initiation of treatment (unless contraindications were specified). A VTE occurring in the presence of one or more provoking factors was classified as provoked. Provoking factors were: surgery or trauma (within 8 weeks before the event), acute medical condition (acute myocardial infarction, acute ischemic stroke, acute infections), immobilization (bed rest >3 days or confinement to wheelchair within the past 8 weeks, or long‐distance travel ≥4 h within the past 14 days), or other factors specifically described as provoking by a physician in the medical record (e.g., intravascular catheter).

There were 462 individuals who experienced a VTE event during the follow‐up period (1994–2007). For each case, two age‐ and sex‐matched controls, who were alive at the index date of the corresponding VTE case, were randomly sampled from the source cohort (n = 924). In total, 349 (140 cases and 209 controls) lacked plasma samples and 67 (26 VTE cases and 41 controls) had plasma samples of insufficient quality (e.g., hemolysis). Hence, our study population consisted of 296 subjects with incident VTE and 674 age‐ and sex‐matched controls. The regional committee for medical and health research ethics approved the study, and all participants provided informed written consent.

2.2. Baseline measurements

At inclusion in Tromsø 4 (1994–1995), baseline information was collected by physical examinations, blood samples, and self‐administered questionnaires. All participants had their height (to the nearest centimeter) and weight (to the nearest 0.5 kg) measured, wearing light clothing and no shoes. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared (kg/m2). Information on previous cardiovascular disease and cancer was collected from the self‐administered questionnaires.

2.3. Handling of blood samples

Nonfasting blood samples were collected at baseline inclusion in Tromsø 4 (1994–1995) by venipuncture of an antecubital vein, with minimal stasis, into blood collection tubes containing ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K3‐EDTA 40 µL, 0.37 mol/L per tube) (Becton Dickinson, Meylan Cedex). Cell counts were performed using a Coulter Counter (Coulter Electronics). Platelet poor plasma (PPP) was prepared by centrifugation at 3000g for 10 min at room temperature. Plasma aliquots of PPP were transferred to 1‐ml cryovials (Greiner Laboratechnik, Nürtringen, Germany) and stored at −80°C.

2.4. Measurement of PPLCT in plasma

PPL clotting time was measured in platelet free (PFP) EDTA plasma using a modified factor Xa‐dependent clotting assay. 23 In short, PPP samples were thawed and centrifuged at 13,500g for 2 min to generate PFP. Phospholipid‐depleted plasma (PPLDP) used as a reagent in the assay was prepared from pooled citrated PFP (n = 18) centrifuged at 100,000g for 60 min at 16°C (Beckman Optima LE‐80K Ultracentrifuge, rotor SW40TI; Beckman Coulter). PPLDP was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use. Twenty‐five microliters of sample PFP was mixed with 25 μL of PPLDP and incubated for 2 minutes at 37°C, before the reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 μL prewarmed factor Xa reagent containing bovine factor Xa (0.1 U/ml) in 15 mM calcium chloride, 100 mM sodium chloride, and 20 mM HEPES buffer (pH 7.0). Clotting tests were carried out in duplicate on a StarT4 instrument from Diagnostica Stago (Asnières sur Seine Cedex, France) and measured in seconds of clotting time. The variation between runs were adjusted for by an internal standard. The technician carrying out the measurements was blinded to the identity and case‐control status of the samples. The PPL assay displayed low intra‐ and inter‐series coefficients of variation (CV) ranging from 2.8% to 4.1%.

2.5. Measurements of thrombin generation in plasma

Thrombin generation was assessed using a calibrated automated thrombinoscope and was performed as described by Hemker et al 24 and manufacturer's instructions (Thrombinoscope BV). Thrombin generation was measured in a Fluoroscan Ascent Fluorometer (Thermolabsystems OY) equipped with a dispenser. Fluorescence intensity was detected at wavelengths of 355 nm (excitation filter) and 460 nm (emission filter). Briefly, 40 µl of plasma was mixed with 40 µl Hepes buffer (20 mM Hepes and 140 mM NaCl) and pipetted into the wells of round bottom 96‐well microtiter plates (Immulon, Lab Consult, Lillestrøm, Norway). Ten microliters of TF solution (final concentration of 3 pM) (Innovin; Bade Behring) and 10 µl of a standardized phospholipid in solution (diluted 1:20) (UPTT; BioData Corporation) was added as triggers. Both TF and UPTT were diluted to the stated concentrations in Hepes buffer. The plasma samples measured were a combination of pooled citrated PFP and PPLDP added in ratios of 100:0, 80:20, 60:40, 40:60, 20:80, 10:90, and 0:100, respectively. For each experiment, a fresh mixture of 2.5 mM fluorogenic substrate (Z‐Gly‐Gly‐Arg‐AMC from Bachem, Bubendorf, Switzerland), 0.1 M CaCl2, 20 mM Hepes (Sigma Aldrich), and 60 mg/ml BSA (A‐7030, Sigma Aldrich) with pH 7.35 was prepared. Each dilution of PFP/PPLDP was assigned its own calibrator (Thrombinoscope BV, Maastricht, The Netherlands). The computer software calculated lag time (min), the time to peak (min), the peak of thrombin generation (nM), and the area under the thrombin generation curve (nM*min) and endogenous thrombin potential (ETP). Plasma samples were run in duplicate and each experiment was repeated three times.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.0.4. for Windows; R Foundation). Unconditional logistic regression models were used to estimate odds ratios (ORs) for VTE with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) with plasma PPLCT used as a continuous variable, discretized to quartiles, and dichotomized according to PPLCT ≤25th percentile versus PPLCT >95th percentile. We applied three adjustment models: model 1 included age and sex, model 2 included model 1 + BMI, and model 3 included model 2 + history of cardiovascular disease (CVD), history of cancer and platelet count. The PPLCT quartile cutoffs were determined using the control group.

Because the follow‐up time in the source cohort was long (>12 years for many persons), the results based on baseline PPLCT measurements could be influenced by regression dilution bias. 25 To investigate this, we performed analyses in which we restricted the maximum time from blood sampling in Tromsø 4 to the VTE events, while keeping all controls in the analyses. The logistic regression analyses on time restrictions were set to require at least 10 VTE events, and ORs were generated every time a VTE event occurred and plotted as a function of time from blood sampling to VTE.

Finally, generalized additive regression plots were generated to visualize the association over the continuum of PPLCT values by modelling PPLCT with a smoothing spline fit in a logistic model adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. We created a plot for the full follow‐up, as well as plots restricted to the first 3 and 6 years of follow‐up, respectively. We transformed PPLCT values to follow a perfect standard normal distribution (i.e., mean value of 0 and standard deviation of 1) before entering the analyses.

3. RESULTS

The distribution of characteristics of the study population at baseline across quartiles of plasma PPLCT is presented in Table 1. The mean age and BMI were similar, whereas the percentage of men (42.9% in Q1–47.8% in Q4) and the proportion of individuals with self‐reported CVD (13.5% in Q1–18.8% in Q4) increased across quartiles. In contrast, the proportion of individuals with self‐reported cancer decreased (7.1% in Q1–2.9% in Q4) across quartiles of PPLCT.

TABLE 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 970) across quartiles of PPL clotting time

| Clotting time (s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Q1 (26.5–51.7) |

Q2 (51.7–60.0) |

Q3 (60.0–71.5) |

Q4 (71.5–148.5) |

|

| Subjects, n | 252 | 243 | 230 | 245 |

| Age, y | 59 ± 14 | 61 ± 13 | 61 ± 14 | 61 ± 14 |

| Sex, % men (n) | 42.9 (108) | 47.7 (116) | 46.5 (107) | 47.8 (117) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.1 ± 4.5 | 26.6 ± 4.0 | 26.6 ± 4.4 | 26.5 ± 4.1 |

| CVD a , % (n) | 13.5 (34) | 16.0 (39) | 15.2 (35) | 18.8 (46) |

| Cancer a ,% (n) | 7.1 (18) | 6.2 (15) | 5.2 (12) | 2.9 (7) |

| WBC, 109/L | 7.2 ± 1.9 | 7.1 ± 3.3 | 6.8 ± 1.7 | 6.8 ± 1.9 |

| Platelet count, 109/L | 259 ± 57 | 247 ± 53 | 240 ± 47 | 230 ± 52 |

| Hematocrit, % | 41.5 ± 3.3 | 41.7 ± 3.6 | 41.4 ± 3.0 | 41.5 ± 3.4 |

Values are mean ±1 standard deviation or percentage with absolute numbers in parentheses.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease (myocardial infarction, angina, stroke); WBC, white blood cell count.

Self‐reported history of disease.

Characteristics of patients at VTE diagnosis are shown in Table 2. The mean age at the time of VTE was 68 years, 47% were men, and 59% of the events were DVT. The majority of the VTE events were provoked (60.1%), and the leading provoking factors were active cancer (27.7%), surgery or trauma (21.3%), and immobilization (18.2%).

TABLE 2.

Characteristics of the VTE patients (n = 296)

| Age at VTE, y | 68 ± 14 |

| Sex, % men | 47.0 (139) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 58.8 (174) |

| Pulmonary embolism | 41.2 (122) |

| Unprovoked VTE | 39.9 (118) |

| Provoked VTE | 60.1 (178) |

| Active cancer | 27.7 (82) |

| Surgery/trauma | 21.3 (63) |

| Immobilization | 18.2 (54) |

| Acute medical condition | 15.9 (47) |

| Other factors | 4.1 (12) |

Values are mean ±1 standard deviation or percentage with absolute numbers in parenthesis.

Abbreviation: VTE, venous thromboembolism.

The ORs of VTE across categories (quartiles and >95th percentile) and per 1 standard deviation (i.e., 14.5 s) increase in plasma PPLCT are shown in Table 3. There was a weak inverse association between plasma PPLCT and risk of VTE per 1 standard deviation increase of PPLCT (OR 0.93, 95% CI 0.80–1.07), and in subjects with PPLCT in the highest quartile (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.60–1.30) compared with those in the lowest quartile, in analyses adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. However, subjects with particularly prolonged PPLCT (>95th percentile) had lower ORs for VTE (OR 0.35, 95% CI 0.13–0.81) than those with PPLCT ≤25th percentile in analyses adjusted for age, sex, and BMI. Similar results were found for DVT and PE (Table 3), but the OR for PE (OR 0.14, 95% CI 0.01–0.69) was lower than for DVT (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.17–1.25) in analyses comparing individuals with PPLCT >95th percentile versus ≤25th percentile. Further adjustment for history of CVD, history of cancer, and platelet count had negligible influence on the results (Table 3, model 3). The ORs for unprovoked and provoked VTE, DVT, and PE were similar to those found in the overall analyses (data not shown).

TABLE 3.

Odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) for venous thromboembolism (VTE), deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism, per standard deviation (SD) increase and across increasing quartiles of procoagulant phospholipid (PPL) clotting time (s)

| PPL clotting time (s) |

Cases n |

Controls n |

Model 1 OR (95% CI) |

Model 2 OR (95% CI) |

Model 3 OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venous thromboembolism | |||||

| Per SD | 296 | 674 | 0.94 (0.81–1.08) | 0.93 (0.80–1.07) | 0.95 (0.82–1.10) |

| Q1 (26.5–54.3) | 83 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Q2 (54.3–63.5) | 74 | 169 | 0.89 (0.61–1.30) | 0.87 (0.59–1.27) | 0.84 (0.57–1.24) |

| Q3 (63.5–74.5) | 63 | 167 | 0.77 (0.52–1.13) | 0.75 (0.51–1.12) | 0.77 (0.51–1.15) |

| Q4 (74.5–148.5) | 76 | 169 | 0.92 (0.63–1.34) | 0.89 (0.60–1.30) | 0.94 (0.64–1.40) |

| ≤25% (26.5–54.3) | 83 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| >95% (89.9–148.5) | 6 | 34 | 0.36 (0.13–0.83) | 0.35 (0.13–0.81) | 0.32 (0.10–0.78) |

| Deep vein thrombosis | |||||

| Per 1 SD increase | 174 | 674 | 0.98 (0.83–1.17) | 0.97 (0.82–1.15) | 0.98 (0.82–1.18) |

| Q1 (26.5–54.3) | 50 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Q2 (54.3–63.5) | 32 | 169 | 0.64 (0.39–1.05) | 0.63 (0.38–1.03) | 0.57 (0.34–0.94) |

| Q3 (63.5–74.5) | 47 | 167 | 0.96 (0.61–1.51) | 0.95 (0.60–1.49) | 0.90 (0.59–1.51) |

| Q4 (74.5–148.5) | 45 | 169 | 0.91 (0.57–1.43) | 0.87 (0.55–1.38) | 0.90 (0.56–1.45) |

| ≤25% (26.5–54.3) | 50 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| >95% (89.9–148.5) | 5 | 34 | 0.50 (0.16–1.25) | 0.50 (0.16–1.25) | 0.43 (0.12–1.15) |

| Pulmonary embolism | |||||

| Per 1 SD increase | 122 | 674 | 0.88 (0.71–1.06) | 0.87 (0.71–1.06) | 0.90 (0.73–1.11) |

| Q1 (26.5–54.3) | 33 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| Q2 (54.3–63.5) | 42 | 169 | 1.26 (0.76–2.09) | 1.22 (0.73–2.04) | 1.23 (0.74–2.08) |

| Q3 (63.5–74.5) | 16 | 167 | 0.49 (0.25–0.90) | 0.48 (0.25–0.89) | 0.51 (0.26–0.95) |

| Q4 (74.5–148.5) | 31 | 169 | 0.92 (0.54–1.58) | 0.89 (0.52–1.54) | 0.98 (0.56–1.71) |

| ≤25% (26.5–54.3) | 33 | 169 | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) | 1 (ref) |

| >95% (89.9–148.5) | 1 | 34 | 0.15 (0.01–0.72) | 0.14 (0.01–0.69) | 0.15 (0.01–0.76) |

Model 1: adjusted for age and sex. Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index. Model 3: age, sex, body mass index, history of cardiovascular disease, cancer, and platelet count. 1 standard deviation (SD) of PPLCT = 14.5 s.

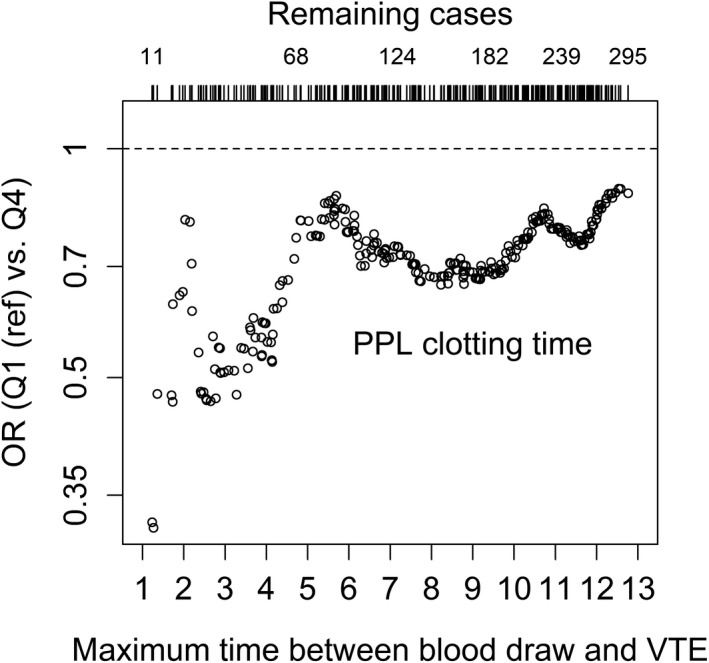

To consider the possibility of underestimating ORs because of regression dilution bias, we estimated ORs for VTE among subjects with the highest (highest quartile) versus lowest (lowest quartile) plasma PPLCT as a function of time between blood sampling and the VTE events (Figure 1). The inverse association between high plasma PPLCT and VTE was stronger with shortened time between the blood sampling and the VTE events. The ORs for DVT and PE as a function of time between blood sampling and events showed similar patterns as the ORs for overall VTE (data not shown).

FIGURE 1.

Estimated odds ratios (OR) for venous thromboembolism (VTE) by procoagulant phospholipid clotting time (PPLCT) quartile 4 compared with quartile 1. Each circle represents an analysis for a given maximum time between blood draw and VTE. At each time restriction, only VTE cases with a time below this maximum were included in the analysis, whereas all controls were included. The analysis is adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index

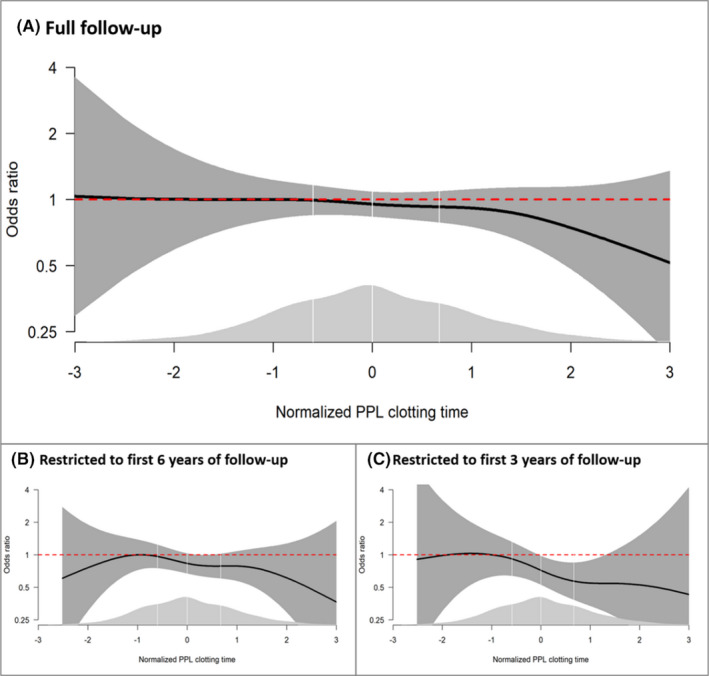

The ORs of VTE over the continuum of PPLCT are visualized in Figure 2. When analyses were performed with full follow‐up time, it was clear that the inverse association occurred at the upper extreme of the PPLCT values (Figure 2A). In analyses restricted to the first 6 (Figure 2B) and 3 years of follow‐up (Figure 2C), the association was stronger and showed a more linear pattern.

FIGURE 2.

Odds ratios (ORs) of venous thromboembolism (VTE) as a function of procoagulant phospholipid clotting time (PPLCT) in a generalized additive regression model adjusted for age, sex, and body mass index. Panel A shows the results for the full follow‐up, whereas panels B and C show the results of analyses restricted to the first 6 and 3 years of follow‐up, respectively. The solid lines indicate ORs, and the surrounding shaded areas show the 95% confidence intervals. PPLCT values were transformed to follow a perfect standard normal distribution (mean value of 0 and standard deviation of 1) before entering the analyses. The distribution of PPLCT is shown as density plots (light gray) at the bottom; white vertical lines indicate quartile cutoffs

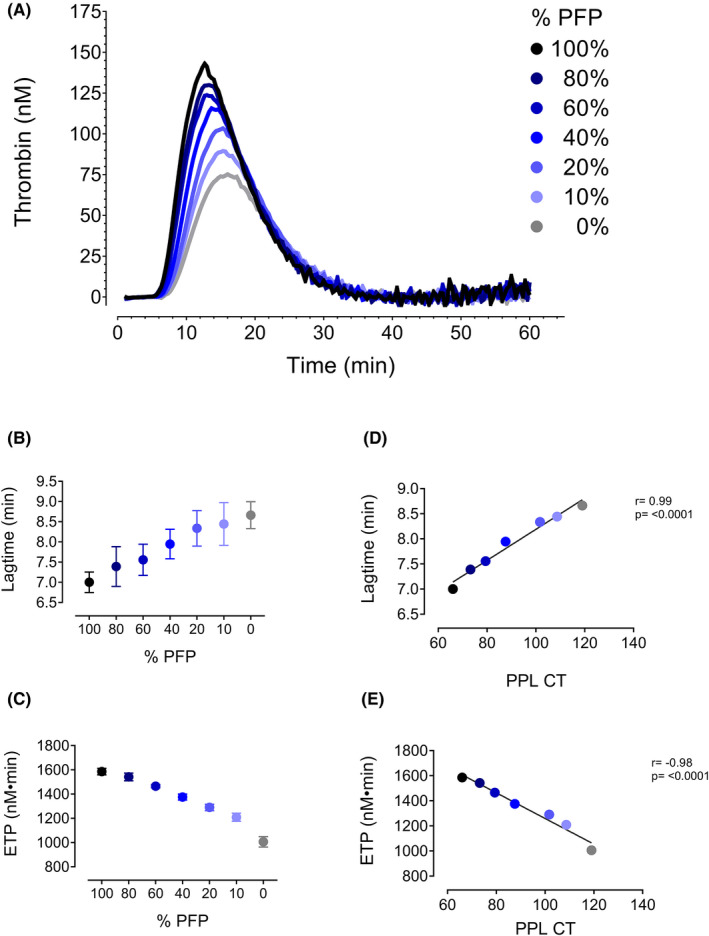

To study the effect of plasma procoagulant phospholipids on thrombin generation, mixtures of pooled PFP and PPLDP were analyzed using the CAT assay. As shown in Figure 3A, thrombin generation declined in a dose‐dependent manner with declining percentage of PFP added (i.e., declining levels of PPL). A clear dose‐response relationship was observed between plasma PPL levels and parameters of the CAT assay (i.e., lag‐time and ETP) (Figure 3B and 3C). The PPLCT correlated strongly with both lag time (r = 0.99, p ≤ 0.0001, Figure 3D) and ETP (r = −0.98, p ≤ 0.0001, Figure 3E).

FIGURE 3.

Pooled platelet‐free plasma (PFP) was mixed in varying ratios (100%, 80%, 60%, 40%, 20%, 10%; and 0%) with phospholipid‐depleted plasma (PPLDP) and run on the CAT assay. (A) Thrombin generation curves. A dose‐dependent relationship was observed for both (B) lag time and (C) ETP and % PFP added to the reaction. PPL clotting time (PPLCT) correlates strongly with both (D) lag time and (E) ETP

4. DISCUSSION

We investigated the association between plasma PPLCT and future risk of VTE in a population‐based nested case‐control study. Prolonged PPLCT displayed a modest inverse association with VTE risk both when PPLCT were used as a continuous and as a categorized variable in the logistic regression models. However, extremely prolonged PPLCT (above the 95th percentile) was associated with lowered risk of VTE (OR 0.35) compared with PPLCT in the lowest quartile. Similar results were observed in subgroup analysis for PE and DVT. The results appeared to be influenced by regression dilution bias because the ORs for VTE by plasma PPLCT decreased substantially with shortened time between blood collection and the VTE events. Our findings support the hypothesis of an inverse association between plasma PPLCT and VTE risk.

Our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to investigate the association between plasma PPLCT and future risk of VTE in the general population. In a recent cross‐sectional study including 100 patients referred to the emergency department under suspicion of VTE, plasma PPLCT, assessed by the STA Procoag PPL assay (Diagnostica Stago), did not discriminate between patients with (n = 31) and without VTE. 26 The lack of discriminatory diagnostic power by the PPL assay may have been diluted by other conditions associated with shortened PPLCT among patients without VTE. However, this does not exclude the potential association between plasma PPLCT and future risk of VTE. Further, plasma levels of modifiable biomarkers, such as PPLCT, are expected to change over time. Fluctuations in the exposure variable during follow‐up will lead to the phenomenon called regression dilution bias, 25 which usually results in an underestimation of the true association between exposure and outcome. Accordingly, we found that the risk estimates for VTE declined substantially with shortened time between measurement of plasma PPLCT and the VTE events.

Circumstantial evidence supports an association between plasma PPLCT and the risk of future VTE. First, the PPLCT is inversely associated with annexin V‐positive EVs 15 , 27 and high plasma levels of EVs are associated with VTE risk in most, 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 but not all studies. 20 , 28 Second, in a cross‐sectional study including plasma samples from 100 healthy individuals and patients with obstructive sleep apnea, plasma PPLCT showed strong and inverse correlations to parameters of thrombin generation, such as ETP and peak thrombin concentration, using the CAT assay with the addition of minimal amounts of phospholipids and tissue factor (1 pM) to trigger thrombin generation. 27 Accordingly, we demonstrated a clear dose‐response relationship between plasma PPLCT and parameters of the CAT assay. In addition, several studies have shown that parameters of the CAT assay, particularly lag time and ETP, are associated with incident 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 and recurrent 34 , 35 , 36 VTE. Third, carriers of rare (e.g., deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and S) 37 and common (e.g., factor V Leiden and the prothrombin mutation G20210A) 38 , 39 prothrombotic genotypes had significantly shorter plasma PPLCT than noncarriers, providing indirect evidence for lower risk of VTE with prolonged plasma PPLCT.

Although we observed an inverse association of PPLCT with both DVT and PE, the OR for PE (0.14) was lower than that of DVT (0.50). The potential biological mechanism for this difference is not known. Because only 50% of PEs originate from DVTs, 40 this may suggest that prolonged PPLCT was accompanied by less thrombus formation at other anatomical sites vulnerable for embolization (e.g., right atrium associated with atrial fibrillation 41 ) or in situ thrombus formation within the lungs. However, the apparent effect difference could also be a chance finding because the subgroups are small.

Strengths of our study include recruitment of VTE patients from a population‐based cohort with age‐ and sex‐matched controls from the same source population in which blood samples were collected before the VTE event. This allows assumptions on the direction of the observed association between plasma PPLCT and VTE. Further, the modified FXa‐dependent PPL clotting assay is highly sensitive and displayed a low CV of ≤4%. A limitation with our study is that plasma samples used were collected in 1994–1995 and stored at −80°C until analysis >20 years later. The long storage time, as well as freezing and thawing, might possibly affect the plasma PPLCT. However, it is unlikely that it would affect our end results because the potential effects would be similar for both cases and controls. Moreover, the PPL levels were only measured in baseline samples, whereas potential changes during follow‐up were not accounted for. This might lead to an underestimation of the true association between plasma levels of PPLCT and VTE risk because of regression dilution bias. 25 In our study, some plasma samples were excluded due to either missing samples or poor plasma quality. The plasma samples were missing completely at random; hence, there was no selection bias.

In conclusion, results from our nested case‐control study indicate an inverse association between plasma PPLCT (measured by a modified FXa‐dependent PPL clotting assay) and the risk of future VTE. Moreover, we demonstrated a clear relationship between plasma PPLCT and thrombin generation parameters. Subjects with PPLCT above the 95th percentile had particularly low risk of future VTE, and the results were strongly influenced by regression dilution bias. Further studies are needed to validate our findings and unravel the mechanisms behind this observation.

RELATIONSHIP DISCLOSURE

The authors state that they have no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C. Ramberg planned experiments, analyzed data, and wrote and revised the manuscript. L. Wilsgård and N. Latysheva planned and performed experiments and revised the manuscript. S.K. Brækkan analyzed data and revised the manuscript. K. Hindberg performed statistical analysis and revised the manuscript. O. Snir planned experiments, analyzed data, and revised the manuscript. T. Sovershaev revised the manuscript. J.‐B. Hansen conceived and designed the study, analyzed data, and participated in writing and revision of the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thrombosis Research Center (TREC) was supported by an independent grant from Stiftelsen Kristian Gerhard Jebsen.

Ramberg C, Wilsgård L, Latysheva N, et al. Plasma procoagulant phospholipid clotting time and venous thromboembolism risk. Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2021;5:e12640. doi: 10.1002/rth2.12640

Handling Editor: Dr Suzanne Cannegieter

Handling Editor: Dr Suzanne Cannegieter

Handling Editor: Dr Suzanne Cannegieter

REFERENCES

- 1. Rosendaal FR. Causes of venous thrombosis. Thromb J. 2016;14:24. doi: 10.1186/s12959-016-0108-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Silverstein MD, Heit JA, Mohr DN, Petterson TM, O'Fallon WM, Melton LJ 3rd. Trends in the incidence of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a 25‐year population‐based study. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:585‐593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heit JA. Epidemiology of venous thromboembolism. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:464‐474. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Prandoni P, Kahn SR. Post‐thrombotic syndrome: prevalence, prognostication and need for progress. Br J Haematol. 2009;145:286‐295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2009.07601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Klok FA, van der Hulle T, den Exter PL, Lankeit M, Huisman MV, Konstantinides S. The post‐PE syndrome: a new concept for chronic complications of pulmonary embolism. Blood Rev. 2014;28:221‐226. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2014.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arshad N, Bjori E, Hindberg K, Isaksen T, Hansen JB, Braekkan SK. Recurrence and mortality after first venous thromboembolism in a large population‐based cohort. J Thromb Haemost. 2017;15:295‐303. doi: 10.1111/jth.13587 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heit JA, Ashrani A, Crusan DJ, McBane RD, Petterson TM, Bailey KR. Reasons for the persistent incidence of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:390‐400. doi: 10.1160/TH16-07-0509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Huang W, Goldberg RJ, Anderson FA, Kiefe CI, Spencer FA. Secular trends in occurrence of acute venous thromboembolism: the Worcester VTE study (1985–2009). Am J Med. 2014;127(9):829‐839.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.03.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arshad N, Isaksen T, Hansen JB, Braekkan SK. Time trends in incidence rates of venous thromboembolism in a large cohort recruited from the general population. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32:299‐305. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0238-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Raskob GE, Angchaisuksiri P, Blanco AN, et al.; ISTH Steering Committee for World Thrombosis Day . Thrombosis: a major contributor to the global disease burden. J Thromb Haemost. 2014;12:1580‐1590. doi: 10.1111/jth.12698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grosse SD, Nelson RE, Nyarko KA, Richardson LC, Raskob GE. The economic burden of incident venous thromboembolism in the United States: a review of estimated attributable healthcare costs. Thromb Res. 2016;137:3‐10. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2015.11.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Owens AP 3rd, Mackman N. Microparticles in hemostasis and thrombosis. Circ Res. 2011;108:1284‐1297. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.233056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zwaal RF, Comfurius P, Bevers EM. Lipid‐protein interactions in blood coagulation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1376:433‐453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ruf W, Rehemtulla A, Morrissey JH, Edgington TS. Phospholipid‐independent and ‐dependent interactions required for tissue factor receptor and cofactor function. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:2158‐2166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Connor DE, Exner T, Ma DD, Joseph JE. Detection of the procoagulant activity of microparticle‐associated phosphatidylserine using XACT. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis. 2009;20:558‐564. doi: 10.1097/MBC.0b013e32832ee915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chirinos JA, Heresi GA, Velasquez H, et al. Elevation of endothelial microparticles, platelets, and leukocyte activation in patients with venous thromboembolism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1467‐1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Campello E, Spiezia L, Radu CM, et al. Endothelial, platelet, and tissue factor‐bearing microparticles in cancer patients with and without venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2011;127:473‐477. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bucciarelli P, Martinelli I, Artoni A, et al. Circulating microparticles and risk of venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2012;129:591‐597. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.08.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jamaly S, Basavaraj MG, Starikova I, Olsen R, Braekkan SK, Hansen JB. Elevated plasma levels of P‐selectin glycoprotein ligand‐1‐positive microvesicles in patients with unprovoked venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost. 2018;16(8):1546‐1554. doi: 10.1111/jth.14162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ye R, Ye C, Huang Y, Liu L, Wang S. Circulating tissue factor positive microparticles in patients with acute recurrent deep venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2012;130:253‐258. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2011.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jacobsen BK, Eggen AE, Mathiesen EB, Wilsgaard T, Njolstad I. Cohort profile: the Tromso study. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:961‐967. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyr049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Braekkan SK, Borch KH, Mathiesen EB, Njolstad I, Wilsgaard T, Hansen JB. Body height and risk of venous thromboembolism: the Tromso Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;171:1109‐1115. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ramberg C, Jamaly S, Latysheva N, et al. A modified clot‐based assay to measure negatively charged procoagulant phospholipids. Sci Rep. 2021;11:9341. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-88835-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hemker HC, Giesen P, Al Dieri R, et al. Calibrated automated thrombin generation measurement in clotting plasma. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2003;33:4‐15. doi: 10.1159/000071636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hutcheon JA, Chiolero A, Hanley JA. Random measurement error and regression dilution bias. BMJ. 2010;340:c2289. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Riva N, Vella K, Hickey K, et al. Biomarkers for the diagnosis of venous thromboembolism: D‐dimer, thrombin generation, procoagulant phospholipid and soluble P‐selectin. J Clin Pathol. 2018;71:1015‐1022. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2018-205293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ayers L, Harrison P, Kohler M, Ferry B. Procoagulant and platelet‐derived microvesicle absolute counts determined by flow cytometry correlates with a measurement of their functional capacity. J Extracell Vesicles. 2014;3(1):25348. doi: 10.3402/jev.v3.25348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Owen BA, Xue A, Heit JA, Owen WG. Procoagulant activity, but not number, of microparticles increases with age and in individuals after a single venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2011;127:39‐46. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.10.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. van Hylckama VA, Christiansen SC, Luddington R, Cannegieter SC, Rosendaal FR, Baglin TP. Elevated endogenous thrombin potential is associated with an increased risk of a first deep venous thrombosis but not with the risk of recurrence. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:769‐774. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06738.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hoiland II, Liang RA, Hindberg K, et al. Associations between complement pathways activity, mannose‐binding lectin, and odds of unprovoked venous thromboembolism. Thromb Res. 2018;169:50‐56. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.06.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lutsey PL, Folsom AR, Heckbert SR, Cushman M. Peak thrombin generation and subsequent venous thromboembolism: the Longitudinal Investigation of Thromboembolism Etiology (LITE) study. J Thromb Haemost. 2009;7:1639‐1648. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03561.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Segers O, van Oerle R, ten Cate H, Rosing J, Castoldi E. Thrombin generation as an intermediate phenotype for venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2010;103:114‐122. doi: 10.1160/TH09-06-0356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Besser M, Baglin C, Luddington R, van Hylckama VA, Baglin T. High rate of unprovoked recurrent venous thrombosis is associated with high thrombin‐generating potential in a prospective cohort study. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1720‐1725. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03117.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Eichinger S, Hron G, Kollars M, Kyrle PA. Prediction of recurrent venous thromboembolism by endogenous thrombin potential and D‐dimer. Clin Chem. 2008;54:2042‐2048. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. van Hylckama VA, Baglin CA, Luddington R, MacDonald S, Rosendaal FR, Baglin TP. The risk of a first and a recurrent venous thrombosis associated with an elevated D‐dimer level and an elevated thrombin potential: results of the THE‐VTE study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:1642‐1652. doi: 10.1111/jth.13043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hron G, Kollars M, Binder BR, Eichinger S, Kyrle PA. Identification of patients at low risk for recurrent venous thromboembolism by measuring thrombin generation. JAMA. 2006;296:397‐402. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.4.397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Campello E, Spiezia L, Radu CM, et al. Circulating microparticles and the risk of thrombosis in inherited deficiencies of antithrombin, protein C and protein S. Thromb Haemost. 2016;115:81‐88. doi: 10.1160/TH15-04-0286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Campello E, Spiezia L, Radu CM, et al. Circulating microparticles in carriers of factor V Leiden with and without a history of venous thrombosis. Thromb Haemost. 2012;108:633‐639. doi: 10.1160/TH12-05-0280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Campello E, Spiezia L, Radu CM, et al. Circulating microparticles in carriers of prothrombin G20210A mutation. Thromb Haemost. 2014;112:432‐437. doi: 10.1160/TH13-12-1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. van Langevelde K, Sramek A, Vincken PW, van Rooden JK, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC. Finding the origin of pulmonary emboli with a total‐body magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging technique. Haematologica. 2013;98:309‐315. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2012.069195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Enga KF, Rye‐Holmboe I, Hald EM, et al. Atrial fibrillation and future risk of venous thromboembolism:the Tromso study. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13:10‐16. doi: 10.1111/jth.12762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]