Abstract

The NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ strain (NOD scid gamma, NSG) is a severely immunodeficient inbred laboratory mouse used for preclinical studies because it is amenable to engraftment with human cells. Combining scid and Il2rgnull mutations results in severe immunodeficiency by impairing the maturation, survival and functionality of IL-2-dependent immune cells, including T, B and natural killer lymphocytes. While NSG mice are reportedly resistant to developing spontaneous lymphomas/leukemias, there are reports of hematopoietic cancers developing. In this study, we characterized the immunophenotype of spontaneous lymphoma/leukemia in 12 NSG mice (20 to 38 weeks old). The mice had a combination of grossly enlarged thymus, spleen, or lymph nodes, and variable histologic involvement of the bone marrow and other tissues. All 12 lymphomas were diffusely CD3-, TDT- and CD4-positive, and 11 of 12 were also positive for CD8, which together was consistent with precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (pre-T LBL). A subset of NSG tissues from all mice, and neoplastic lymphocytes from 8 of 12 cases had strong immunoreactivity for retroviral p30 core protein suggesting an association with a viral infection. These data highlight that NSG mice may develop T-cell lymphoma at low frequency necessitating the recognition of this spontaneously arising disease when interpreting studies.

Keywords: Mice, Lymphoma, Severe Combined Immunodeficiency, Interleukin Receptor Common gamma Subunit, Murine Leukemia Viruses

NSG mice have a severe immunodeficiency phenotype that is caused in part by a spontaneously arising mutation affecting V(D)J recombination, DNA double-strand break repair, and also a genetic modification resulting in loss of function of the common gamma chain of the IL2R. Prkdcscid mice with the Y4046X mutation have impaired V(D)J recombination and DNA double-strand break repair mechanisms thereby preventing the maturation of T and B cells, resulting in the severe combined immunodeficiency phenotype.1 The NOD/Lt congenic strain, which was crossed with the severe combined immunodeficiency (scid) mutation initially on the C.B-17 background (NOD.C.B-17-Prkdcscid, NOD-scid), also has unique immune system deficits including increased susceptibility to some viral infections, decreases in T-cell populations, reduction in the functions of NK cells, altered antigen presenting cell functions, and a lack of circulating complement.27,65 As a result of these genetic modifications and crosses, NSG mice have marked reductions in the numbers of mature T, B, natural killer (NK) and NKT cells as well as altered functions of other IL-2-dependent immune cells.63 NSG mice produce bone-marrow progenitors that are T, B and NK cell lineage-competent and that migrate to and settle in the thymus. However, intrathymic T-cell development to maturity does not occur because of early double-negative stage three (DN3) arrest and apoptosis, which is attributed to the synergistic effects of the scid and Il2rg mutations.11,45

While NSG mice are reportedly resistant to the development of lymphomas/leukemias, other strains of immunodeficient mice such as the NOD-scid mouse develop these cancers at high frequencies mainly because the thymocytes of NOD-scid mice are susceptible to spontaneous lymphomagenesis caused by a retroviral infection by Emv-30, an endogenous murine leukemia virus.13,51,61 In contrast, lymphomagenesis occurring in Prkdcscid mice is believed to be related to the long-known phenomenon of immunocompromised mice becoming “leaky” as evidenced by the detection of serum IgG and low numbers of mature lymphocyte populations.7,12 This “leakiness” resulting in immune dysregulation, and in some cases either B- or T-cell lymphoma/leukemia, is largely considered to be due to alternative maturation mechanisms that lymphocyte populations have evolved in order to survive when normal physiologic processes are perturbed.70

Mice with a severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) phenotype have abnormal maturation of T and B cells.1 Normal precursor T-cell development in the thymic cortex is divided into stages that can be differentiated by a combination of the markers CD4, CD8, CD25, and CD44. The first 4 stages are negative for both CD4 and CD8 with variable combinations of CD44 and CD25 that are defined as double-negative stages 1, 2, 3 and 4 (DN1-DN4). The 5th stage is positive for CD4 and CD8, which is classified as double-positive (DP). In contrast, scid thymi are variable in their content of cells expressing these markers. Usually scid thymocytes have a maturational arrest which prevents them from transitioning from the DN3 stage, in which cells have a CD4- CD8-CD44−CD25+ immunophenotype, to the DN4 stage, in which cells have a CD4- CD8-CD25-CD44- immunophenotype. This maturation arrest results in a severe decrease in total numbers of thymocytes and a rudimentary appearance to the thymus, lymph nodes and splenic white pulp.44 Developing B cell precursors in scid mice are arrested at the pro B cell stage.11 Induction of aspects of the humoral and adaptive immune responses in scid mice (leakiness) correlates with the genetic background, pathogen exposures, and increasing age. The predisposition for a leaky phenotype is considered a major reason for the development of spontaneous lymphomas in scid mice, and the resulting limited lifespans prohibit their use in long term studies.7,8,12,26 While leakiness associated with having the scid mutation is largely abated when backcrossed onto the NOD/Lt strain, the incidence of lymphomas remains even when re-derived in mice that are free of Emv-30 retrovirus.51,61

In Il2rgtm1Wjl (Il2rg; also known as ϒc or CD132) mice, genetic engineering and removal of part of exon 3 and exons 4 – 8 of the interleukin 2 receptor gamma chain gene causes loss of a portion of the extracellular domain and all of the transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains of the ϒc subunit. Consequently, the Il2rg signaling functions are affected causing a comparable phenotype as the human IL2RG deficiency.63,67 Il2rgtm1Wjl mice have rudimentary thymi and demonstrate a block in thymocyte maturation at the CD44+CD25+CD4-CD8- (DN2) to DN3 transition, which differs from that observed in NOD-scid mice. Nevertheless, compensatory signaling pathways exist, allowing a subset of thymocytes to progress through to α/β T-cell differentiation, as evidenced by the presence of mature peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive (SP) T cells by flow cytometry. ϒ/δ T cells, which are considered to be IL2-dependent, are not observed. Unlike NOD-scid mice, mature peripheral B cells are present in Il2rgtm1Wjl mice.11,17,45

Initially, NSG mice were reported to be resistant to developing hematopoietic malignancies such as lymphoma and leukemia.64 Therefore, as a model organism, NSG mice are considered to provide an advantage over C.B-17-scid and NOD-scid mice for both short and long term engraftment studies. However, there are sporadic reports of lymphoma and myeloid leukemia occurring in NSG mice.19,60,72 Spontaneous lymphomagenesis in NSG mice is not entirely unexpected especially since the Prkdcscid mutation was backcrossed onto the NOD/Lt strain, and both strains are well-characterized regarding age-dependent susceptibility for developing these neoplasms.13

An immunodeficient mouse closely related to the NSG is the NOG (NOD.CgPrkdcscid Il2rgtm1Sug/JicTac) mouse, which similarly carries the scid mutation on the NOD background but instead has a truncated ϒc subunit created by replacing parts of exons 7 and 8 of the ϒ-chain gene stopping its signaling functions even though formation of the heterotrimer complex of the IL2R still occurs.49 This method of inactivating the ϒ-chain gene differs from the genetic engineering used to create the NSG mouse, which has deletion of part of exon 3 and exons 4–8 resulting in loss of much of the ϒc extracellular domain and the entire transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains.10 The NOG mouse has been reported to develop CD3+ thymic lymphomas.28 While we and other groups have observed that lymphomas can also arise in NSG, there have been no detailed lineage characterizations of NSG lymphomas to date.60 In this study we have immunophenotyped 12 lymphomas arising spontaneously in NSG mice and found that select non-tumor tissues of all NSG mice were positive for the retroviral p30 core protein, which has been shown to cross-react with endogenous murine leukemia viruses.48 The majority of the lymphomas were also strongly immunopositive for p30. We discuss the implications of these observations in relation to other immunocompromised mouse strains and for research studies involving NSG mice.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

A review of archived tissues from 201 NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid Il2rgtm1Wjl/SzJ (NSG, JAX stock #005557) mice necropsied at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) between 2015 and 2018 revealed a subset of 12 mice with lymphoma.14,64 These 201 NSG were from a research and breeding colony of 6116 animals in the same time frame. All mice were housed at SJCRH under strict specific pathogen free barrier practices (sterilized water, food, bedding, cages, administration of acidified water) and using aseptic handling techniques (including the use of laminar flow hoods, and personal protective equipment and hair coverings) based on their increased susceptibility to opportunistic bacterial infections.19 Mice were tested and reported as negative for the following pathogens: Helicobacter spp., Mycoplasma pulmonis, Pneumocystis carinii, Sendai virus, mouse parvovirus [MPV], mouse hepatitis virus [MHV], minute virus of mice [MVM], Theiler murine encephalomyelitis virus, epizootic diarrhea of infant mice [EDIM], pneumonia virus of mice [PVM], reovirus, K virus, polyoma virus, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus [LCMV], mouse adenovirus [MAV], ectromelia virus, and both murine ecto- and endoparasites. Mice were assigned to animal protocols approved by the SJCRH’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were euthanized in an atmosphere of 100% CO2 or died before illness was detected.

Clinical pathology and microbiology data

Whole blood was collected into tubes with EDTA anticoagulant (BD Microtainer, BD Diagnostics) for the complete blood count analysis (CBC) and peripheral blood smear using an intracardiac collection technique as a terminal procedure. Approximately 20 microliters of EDTA-treated blood were used for analysis on the ForCyte Hematology Analyzer (Oxford Science, Inc.). Peripheral blood smears were prepared, methanol fixed and a Wright-Giemsa stain was applied. For the aerobic blood culture 50–75 microliters of blood was obtained separately and placed into an aerobic bottle using aseptic technique for testing. The available CBC analyses, peripheral blood smears and microbiology data for all mice were reviewed and interpreted by a board-certified veterinary pathologist (HT).

Histopathology

Where possible, tissues from all major organs were collected and processed for histopathologic evaluation. All sampled tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin and reviewed by light microscopy and interpreted by three board-certified veterinary pathologists (HT, LJJ, JER). Mitotic counts were determined for 12 of 12 cases by a board-certified pathologist (HT). The count was based on the assessment of 10 random high power fields with an area calculated as 2.37mm2 using a Nikon Eclipse Ni microscope (400x objective/ 0.95, 10x ocular with field number of 22 mm). Counts were determined starting in the most proliferative area and then moving to nine additional randomly selected areas in samples of either thymus or spleen containing lymphoma/leukemia.

Immunohistochemistry

All formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 4 μm, mounted on positive charged glass slides (Superfrost Plus; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and dried at 60°C for 20 minutes. The IHC procedures and antibodies used for mouse tissue to detect hematolymphoid antigens CD5, CD3ε, terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase (TDT), CD25, CD44, CD4, CD8, CD117, PAX5, B220, CD45 (mouse specific), CD43, MPO, CD68 and GATA 1 were as previously described.53 The primary antibodies used in this study and the IHC procedures for human NUMA1, human CD45 and p30, a retrovirus associated protein, are listed in Table 1. The p30 antibody has been previously published as being cross-reactive with endogenous retroviruses, specifically endogenous murine leukemia viruses.23,48,55 CD1 mouse tissues were used as a positive control for interpreting p30 labeling.55 C57BL/6 (B6) mouse tissues were used as negative controls for the p30 antibody since B6 mice have been reported to have undetectable ecotropic MuLV.72 All IHCs were reviewed by light microscopy and interpreted by two board-certified veterinary pathologists (HT, JER). Positive immunoreactivity for hematolymphoid antigens was defined as having at least 20% of the neoplastic cells showing appropriate labeling patterns by visual assessment.5

Table 1.

Antibodies and Methods used for Immunohistochemistry

| Antibody | Type | Concentration | Supplier |

|---|---|---|---|

| NUMA1 HUMAN | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:75 | Lifespan Biosciences, LS-B11047a |

| CD5 | Mouse monoclonal, IgG1κ | 1:200 | Pharmingen, 553017 |

| CD3ε | Goat polyclonal | 1:1000 | SantaCruz, sc-1127 |

| TDT | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:250 | Supertechs, 004 |

| CD25/IL2Rα | Rabbit monoclonal | 1:30 | Abcam, ab231441 |

| CD44 | Rat monoclonal, IgG2bκ | 1:200 | PharMingen, 550538 |

| CD4 | Rat monoclonal, IgG1κ | 1:40 | eBiosciences, 14–9766 |

| CD8 | Rat monoclonal, IgG2a, lambda | 1:200 | eBiosciences, 14–0808-82 |

| CD117/CKIT | Goat polyclonal | 1:1000 | R&D Systems, AF1356 |

| PAX5 | Rabbit monoclonal | 1:1000 | Abcam, ab109443 |

| CD45R/B220 | Rat IgG2aκ | 1:8000 | PharMingen, 553084 |

| CD45 HUMAN | Mouse monoclonal, IgG1κ | RTUb | Ventana, 760–2505c |

| CD45 MOUSE | Rat LOU/C, LOU/M, IgG2bκ | 1:500 | PharMingen, 553076 |

| CD43 MOUSE | Rat DA x LOU IgG2a, κ | 1:25 | PharMingen, 552366 |

| MPO | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:1200 | DAKO, A0398 |

| CD68 | Rat Ig2a | 1:1000 | BioRad, MCA1957 |

| GATA1 | Rabbit polyclonal | 1:4000 | Abcam, ab131456 |

| RLV p30 | Goat polyclonala | 1:10,000 | Non-commercially available d |

Heat-induced epitope retrieval, Cell conditioning media 2 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ), 32 minutes; Visualization with DISCOVERY OmniMap anti-Rb HRP (760–4311; Ventana Medical Systems), DISCOVERY ChromoMap DAB kit (760–159; Ventana Medical Systems) or DISCOVERY ChromoMap Purple kit (760–229; Ventana Medical Systems)

RTU: ready to use

Heat-induced epitope retrieval, Cell conditioning media 1 (Ventana Medical Systems, Tucson, AZ); Visualization with biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse IgG secondary antibody (Abcam, ab133469), DISCOVERY OmniMap anti-Rb HRP (760–4311; Ventana Medical Systems), DISCOVERY ChromoMap DAB kit (760–159; Ventana Medical Systems) or DISCOVERY ChromoMap Purple kit (760–229; Ventana Medical Systems)

Heat-induced epitope retrieval, Epitope Retrieval solution 1 (ER1), 20 minutes; Visualization with rabbit anti-goat (BA-5000; Vector Laboratories), Bond Polymer Refine Detection (DS9800, Leica Biosystems); Rauscher leukemia virus p30 antibody was a gift from Dr. Sandra Ruscetti

RESULTS

Clinical data of NSG mice with spontaneous lymphoma/leukemia

Ten female and 2 male SJCRH NSG mice between 20 to 38 weeks of age were diagnosed with lymphoma/leukemia (Table 2). In the NSG colony, the overall incidence of lymphoma was determined to be 0.2% based on a NSG population of 6116 during the 2015 to 2018 time period at our institution. Of the 201 NSG mouse necropsies during that time period, 12 (6%) had lymphoma. Therefore, the true incidence for NSG lymphomas in our institution was calculated to be between 0.2 and 6% because not all NSG mice were necropsied.

Table 2.

Clinical Features of NSG Mice with Lymphomas/Leukemias

| Case | Sex | Age (weeks) | Leukocytes X103/µL | Lymphocytes X103/µL (%) | Monocytes X103/µL (%) | Blood Culture | Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | n/p | 4.52a,b | 0.52 (11.4) | 0.69 (15.3) | n/d | Yesc |

| 2 | M | 20 | 5.86a | 0.15 (2.5) | 0.13 (2.2) | n/d | Yesc |

| 3 | M | 20 | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Yesc |

| 4 | F | n/p | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Yesc |

| 5 | F | n/p | 20.04a | 6.67 (33.2) | 0.53 (2.6) | n/d | Yesc,d |

| 6 | F | n/p | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Yesc |

| 7 | F | n/p | n/d | n/d | n/d | n/d | Yesc,d |

| 8 | F | 25 | 6.46a | 1.19 (18.3) | 1 (15.4) | No growth | No |

| 9 | F | 24 | 1.56 | 0.54 (34.8) | 0.07 (4.6) | S. xylosus | Yesc |

| 10 | F | 20 | 17.74a | 5.81 (32.7) | 3.12 (17.5) | No growth | No |

| 11 | F | 38 | 5.08a | 0.89 (17.4) | 0.41 (8.1) | No growth | Yese |

| 12 | F | 35 | 1.74 | 0.24 (13.5) | 0.05 (3.1) | K. pneumoniae; S. lentus | Yese |

Abbreviations: F, female; M, male; n/p, not provided; n/d, not done

Lymphoblasts detected in blood smear

Human B-LBL & mouse T-LBL co-present

Received human cells

Received irradiation

NSG mice are severely immunocompromised and highly susceptible to opportunistic infections not only from commonly encountered murine pathogens but also commensal flora and environmental organisms.19 Furthermore, these mice may independently or concurrently have other age-related conditions such as degenerative diseases and cancer.60 We observed that all NSG mice submitted for necropsy evaluation demonstrated clinical signs of being thin and hunched necessitating their removal from a study or from the breeder room. Seven of the 12 mice were clinically suspected of having study-related pathologies. Five of 12 mice were suspected to have an opportunistic infection. Three of these mice had blood cultures reported as no growth, and 2 had bacteremia in addition to the diagnosis of a lymphoma/leukemia.

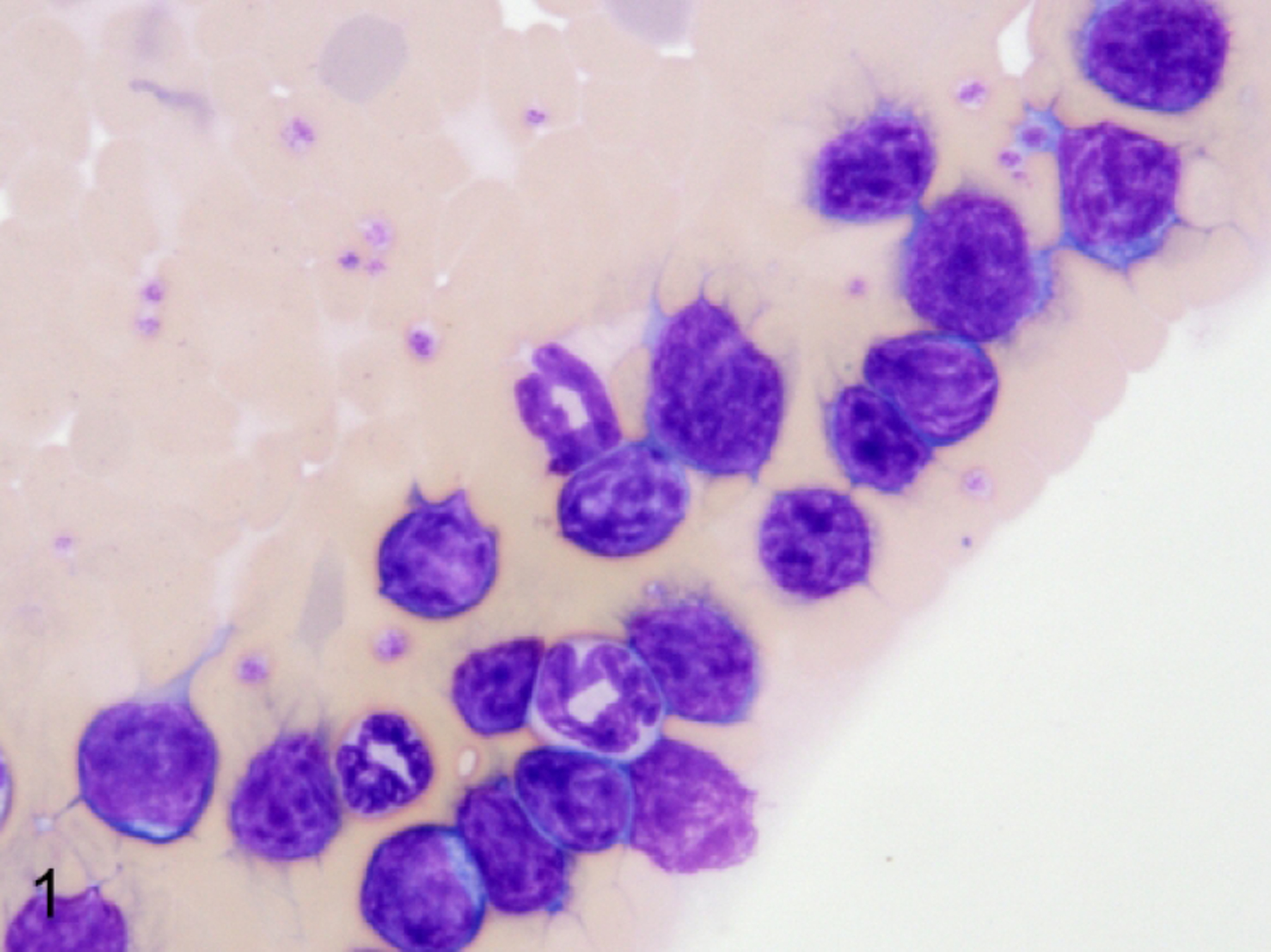

The peripheral blood smears of six of the mice diagnosed with lymphoma were available for evaluation (cases 1, 2, 5, 8, 10 and 11). Five of the six mice had evidence of lymphoma/leukemia in the peripheral blood (Figure 1) as well as bone marrow involvement (Table 3). Case 2 did not have evidence of lymphoma/leukemia in either the peripheral blood or bone marrow. Lymphoma/leukemia diagnosis on peripheral blood smear correlated with increases in leukocyte, lymphocyte and monocyte counts based on reference controls generated in-house for leukocyte, lymphocyte and monocyte counts in naïve NSG mice (Table 2). Additionally, mice with lymphoma also had increases in automated counts for leukocytes, lymphocytes and/or monocytes when compared with reference intervals published for the initial characterizations of NSG mice.62

Figure 1.

Lymphoma with leukemic phase, peripheral blood smear, NSG mouse, case 11. Medium-sized lymphoblasts are visible throughout the feathered edge of the smear and rarely within the body of the smear. Blasts have scant cytoplasm and a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio. Nuclei are round with finely dispersed chromatin and prominent nucleoli. Modified Wright-Giemsa.

Table 3.

Anatomic Distribution of Lymphomas/leukemias Arising in NSG Mice

| Case | Hta | Lu | Kid | Liv | Adr | Spl | Thy | LN | Dig | Repro | Sk | CNS | BM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | n/pb | − | − | − | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | − |

| 3 | n/p | + | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | + |

| 4 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | n/p | − | + | − | − | + |

| 5 | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | n/p | − | − | − | − | + |

| 6 | + | + | − | − | − | + | + | n/p | − | + | − | − | + |

| 7 | n/p | n/p | n/p | + | n/p | + | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | n/p | + |

| 8 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| 9 | + | + | − | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | + |

| 10 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| 11 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − | + | + |

| 12 | + | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | − | − | + | + |

Ht: Heart, Lu: Lung, Kid: Kidney, Liv: Liver, Adr: Adrenal gland, Spl: Spleen, Thy: Thymus, LN: Lymph node including pulmonary, abdominal and peripheral locations, Dig: Digestive system the pancreas and small and large intestines, Repro: Reproductive tissues, Sk: Haired skin

CNS: Central nervous system, BM: Bone marrow

n/p: not provided for histopathology review

Gross and histomorphologic features of lymphomas/leukemias arising spontaneously in NSG mice

The frequent gross lesions of moribund mice submitted for a full pathologic examination were enlargement of rudimentary thymic tissues, splenomegaly, and enlargement of some of the rudimentary lymph nodes. Additionally there was variable hepatomegaly and scattered nodules within the heart, lungs, kidneys, reproductive tissues, and brain and meninges. The lymphomas/leukemias involved the following tissues as viewed by light microscopy (Table 3): thymus (100%, 10 of 10), bone marrow (92%, 11 of 12), lungs (91%, 10 of 11), spleen (91%,10 of 11), heart (90%, 9 of 10), liver (82%, 9 of 11), meninges/ central nervous system (70%, 7 of 10), kidneys (60%, 6 of 10), reproductive tissues (50%, 5 of 10), lymph nodes (50%, 3 out of 6), pancreas (20%, 2 of 10), adrenal glands (20%, 2 of 10), small intestine (10%, 1 of 10) and skin (10%, 1 of 10).

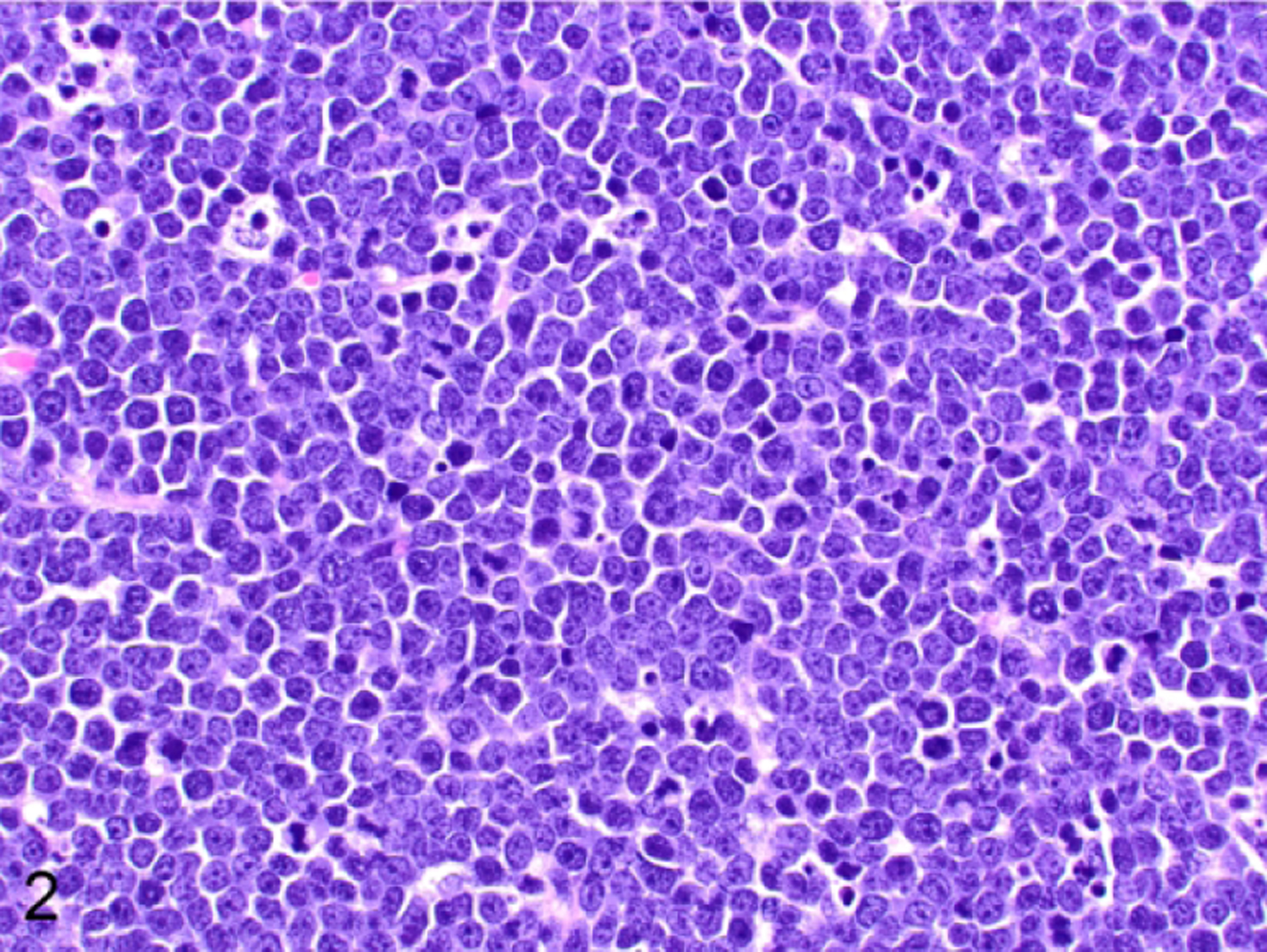

The 12 lymphoid neoplasms occurring in SJCRH NSG mice were classified as precursor T lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia (pre-T-LBL) using the characteristics of lymphoma/leukemia subtypes as outlined by the Bethesda classification of murine lymphoid neoplasms.42 Neoplastic lymphocytes were arranged in sheets of cells expanding and effacing large regions of the rudimentary thymus (Figure 2), spleen (Supplemental Fig S1), and lymph nodes (Supplemental Fig S2). Lymphoma was also observed in the kidneys (Supplemental Fig S3) and the brain. Neoplastic cells formed periportal (Supplemental Fig S4) and sinusoidal infiltrates in the liver, and perivascular and peribronchiolar aggregates in the lungs. In the one case that had involvement of the skin, neoplastic cells formed a distinct focus within the dermis. Epitheliotropism was not observed. Neoplastic round cells were characterized as medium-sized lymphocytes that were approximately 1.5 to 3 times larger than an erythrocyte (the erythrocytes measured approximately 5–6 µM). Neoplastic lymphocytes had a blastic appearance consisting of scant cytoplasm and round nuclei having fine chromatin with inconspicuous or 1–2 small centralized nucleoli. Mitotic count was determined to be 6.8/10 HPF based on 12 of 12 cases.

Figure 2.

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, thymus, NSG mouse, case 2. The neoplastic lymphocytes have scant cytoplasm and round nuclei. The nuclei have a fine chromatin pattern with either centralized or inconspicuous nucleoli. Mitoses are frequent, and there are scattered tingible-body macrophages. Hematoxylin and eosin.

Differentiation of species-specific lymphomas with morphologic similarities

Ten of the 12 mice were included in preclinical studies (Table 2). Two mice were part of the SJCRH NSG breeder colony and did not receive any experimental manipulations. Three mice had been implanted with a human solid tumor in the flank region. Neither lymphovascular invasion nor metastases were observed in these xenotransplants. Seven of the NSG mice in which lymphoma of mouse origin arose had been implanted with human lymphoblastic lymphoma cells taken from different patients. Two of these mice were reported to have received irradiation prior to engraftment with human cells.

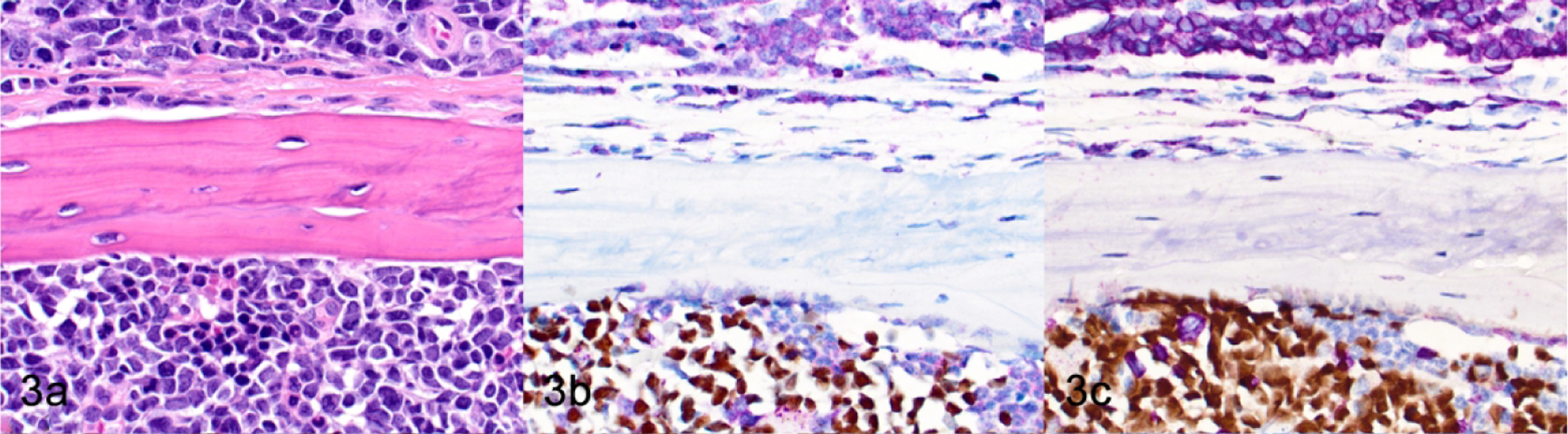

Only one of the five non-irradiated NSG mice xenotransplanted with human lymphoma also had a human B cell lymphoblastic lymphoma. Morphologically, the two lymphomas in this mouse were indistinguishable (Figure 3a), but the human and mouse origins of the two lymphomas were confirmed by IHC as follows. The human B cell lymphoma in this case expressed human-specific CD45 (not shown) and an antigen expressed on the nuclear mitotic apparatus protein 1 of human cells (NUMA1, human specific, Figure 3b); it was negative for mouse-specific CD45 (Figure 3b) and mouse specific CD43 (not shown). A double IHC for both PAX5 and CD3ε did not show overlapping labeling in the same tissue section which was useful for distinguishing between the human and murine lymphomas, respectively (Figure 3c).

Figure 3.

Concurrent murine lymphoma/leukemia and human B-ALL in the same host, sternum, NSG mouse, case 1. A spontaneous murine lymphoma is present in the parietal tissues of the thoracic wall (top of image), and human B-ALL cells are engrafted in the murine sternal bone marrow (bottom of image). (a) HE. (b) The murine lymphoma cells and non-neoplastic murine hematopoietic cells have immunoreactivity for mouse-specific CD45 (purple). The human B-ALL cells have nuclear immunoreactivity for human-specific NUMA1 (brown). (c) Murine lymphoma cells have immunoreactivity for CD3ε (purple). Engrafted human B-ALL cells have nuclear immunoreactivity for PAX5 (brown).

Immunophenotype of NSG lymphomas

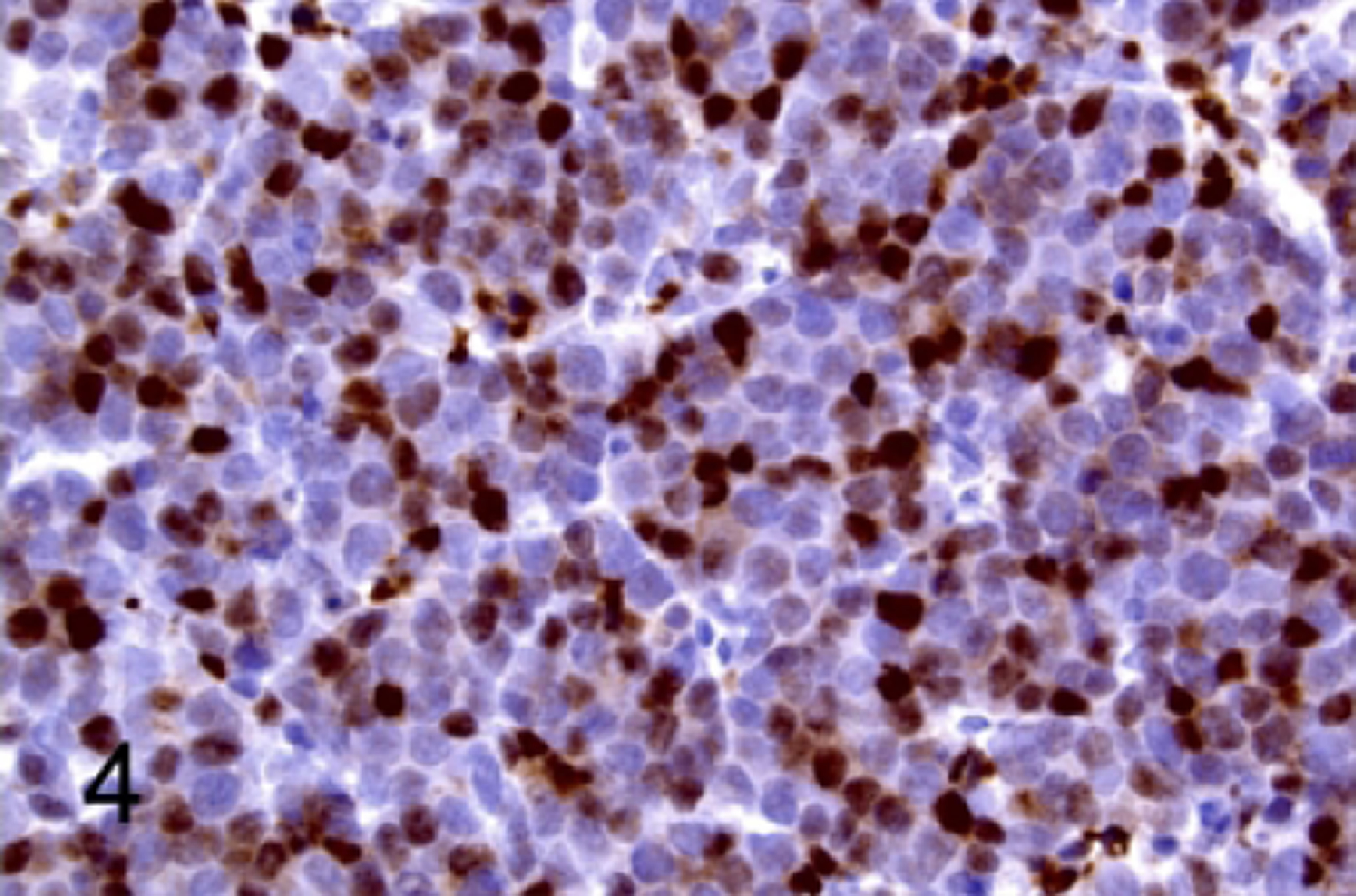

The classification of T-cell proliferations as either reactive or neoplastic requires the evaluation of multiple antigen markers and the anatomic pattern.20,53,54 To determine whether the lymphoproliferations we observed were neoplastic or a reactive change, we analyzed populations within the thymus and the spleen by IHC for pan-T antigens, stage-specific developmental markers, and additional B cell, myeloid and erythroid antigens (Table 4). Antigen expression in all 12 of the NSG T-cell lymphomas/leukemias was consistent with an immature T-cell phenotype, with positive immunolabeling for CD3 (100%, 12 of 12; Figure 3c, top), TDT (100%, 12 of 12; Figure 4), and CD25 (50%, 6 of 12; Figure 5) and lack of immunolabeling for CD44 (Figure 6) and CD117/KIT (not shown). Lymphomas were positive for CD4 (100%, 12 of 12; Figure 7a), CD8 (92%, 11 of 12; Figure 7b), and co-expressed CD4 and CD8 (92%, 11 of 12; Figure 7c). Many lymphomas/leukemias showed a loss of CD5 immunolabeling (58%, 7 of 12; not shown). Lymphomas did not appear to have aberrant antigen expression of B lymphoid antigens PAX5 (Figure 3c, top) and B220 (not shown), or of myeloid antigens MPO (not shown), CD68 (not shown), or GATA 1 (not shown). According to the expression pattern of the panel of markers that were tested by IHC, two general categories of TDT+, immature T lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia could be readily identified based on the developmental expression of normal T cell maturation stages: CD3+CD44-CD25+CD4+CD8+ (92%, 11 of 12 mice) or CD3+CD44- CD25+CD4+CD8- (8%, 1 of 12 mice).

Table 4.

Immunophenotype of Lymphomas/leukemias Arising in NSG Mice

| Case | CD3 | TDT | CD25 | CD44 | CD4 | CD8 | CD5 | CD117 | CD43Mb | PAX5 | CD45Mb | CD45Hc | NUMA1Hc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | +/− a | + | + | + |

| 2 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 3 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 4 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 5 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 6 | + | + | + | − | + | − | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 7 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 8 | + | + | + | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 9 | + | + | + | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 10 | + | + | − | − | + | + | − | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 11 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

| 12 | + | + | − | − | + | + | + | − | + | − | + | − | − |

Human B-LBL & mouse T-LBL co-present

M: Mouse specific

H: Human specific

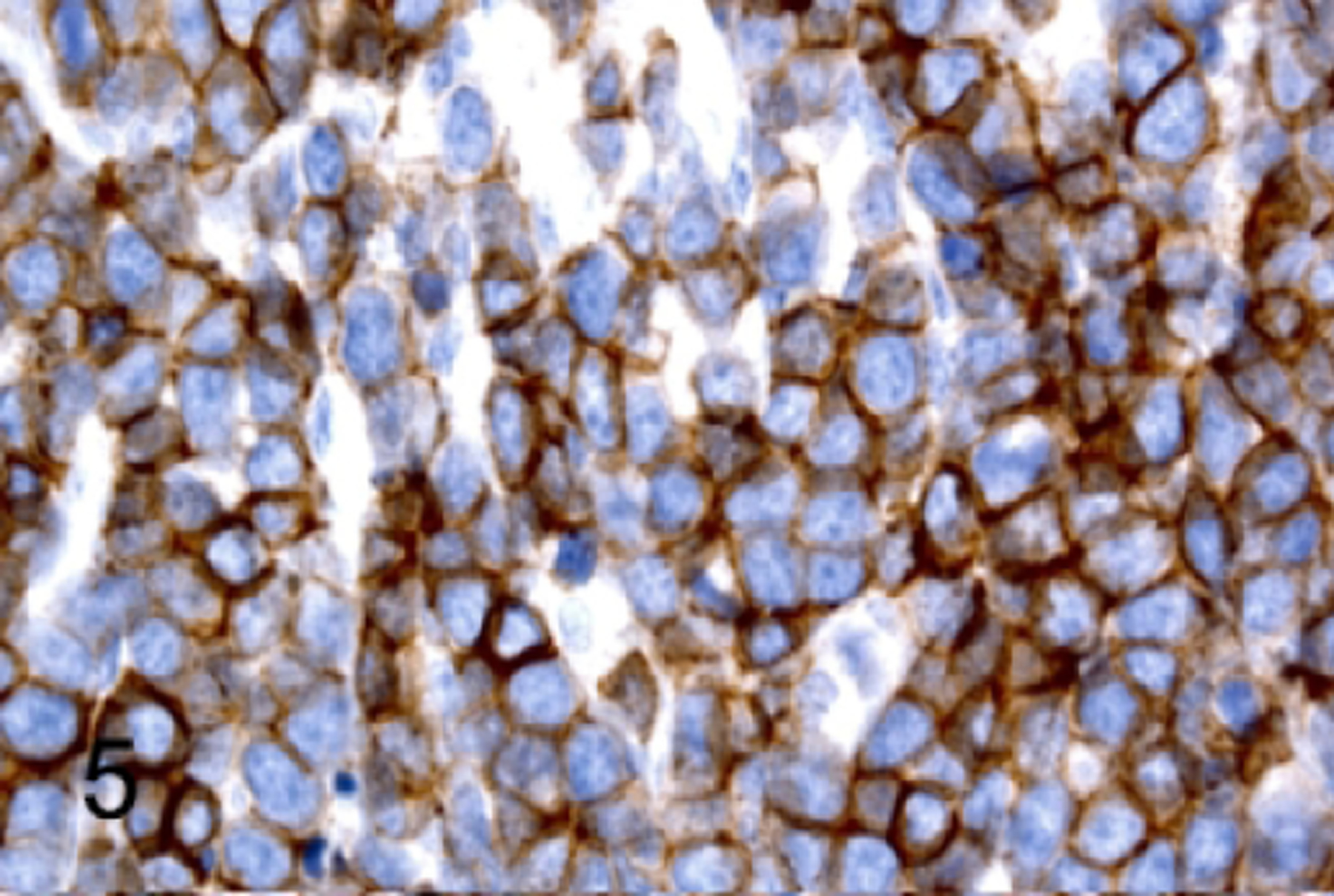

Figure 4.

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, thymus, NSG mouse, case 2. Neoplastic cells have immunoreactivity for TDT.

Figure 5.

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, thymus, NSG mouse, case 3. Neoplastic cells have immunoreactivity for CD25.

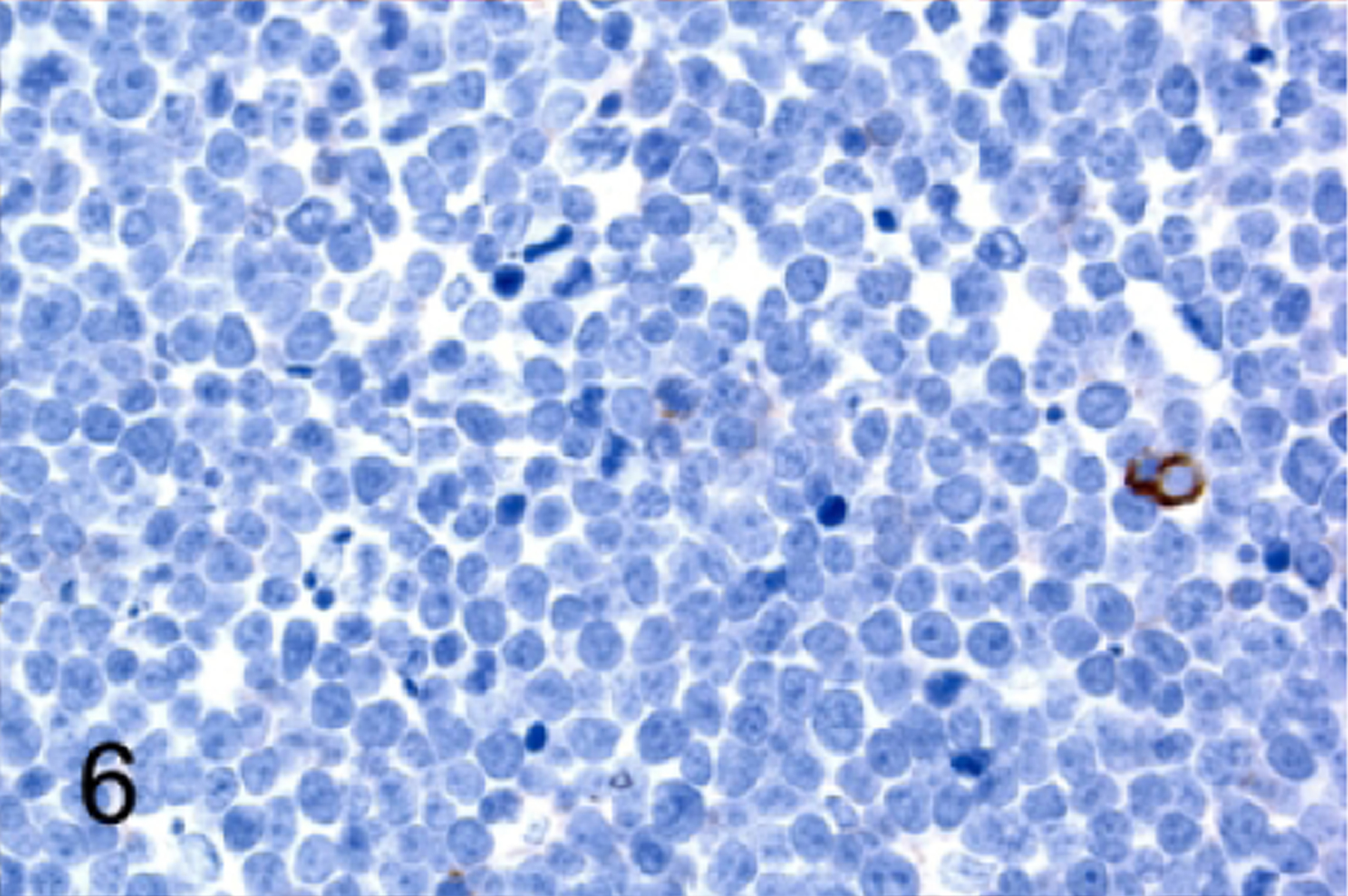

Figure 6.

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, thymus, NSG mouse, case 3. Neoplastic cells do not express CD44.

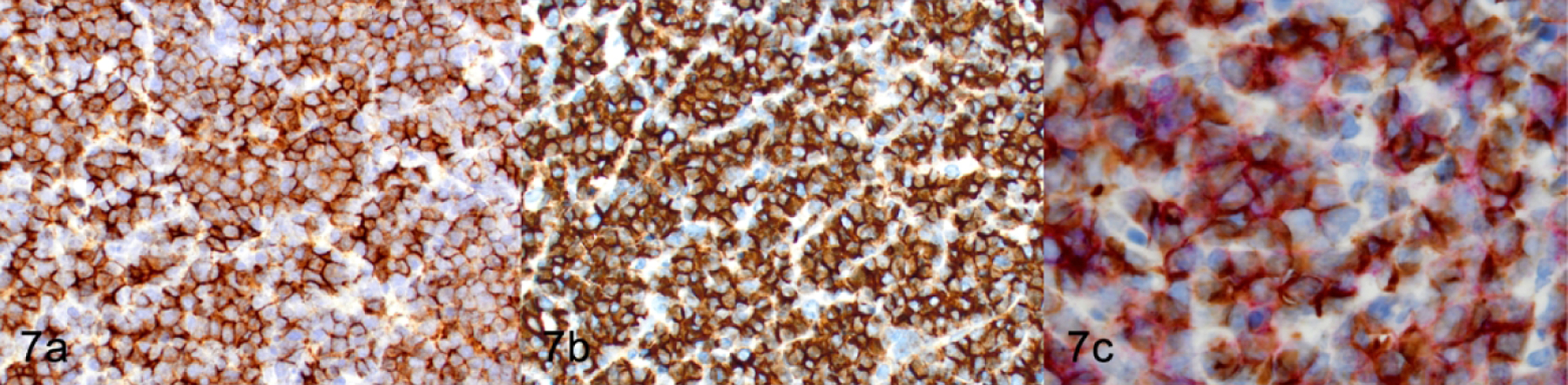

Figure 7.

T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia, thymus, NSG mouse, Case 2. (a) IHC for CD4. (b) IHC for CD8 (c) Double IHC for CD4 (purple) and CD8 (brown).

NSG lymphomas express the retrovirus associated p30 core protein

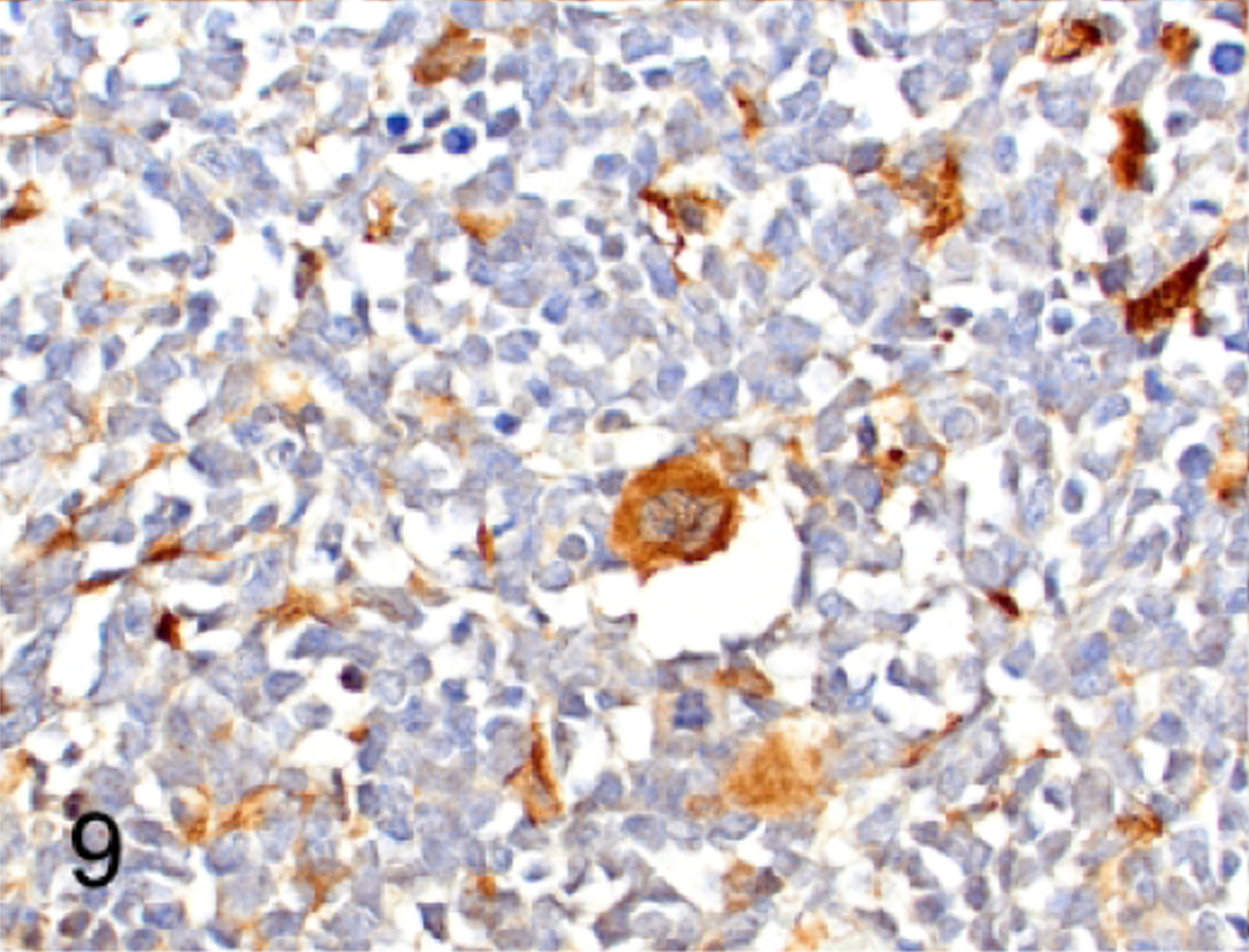

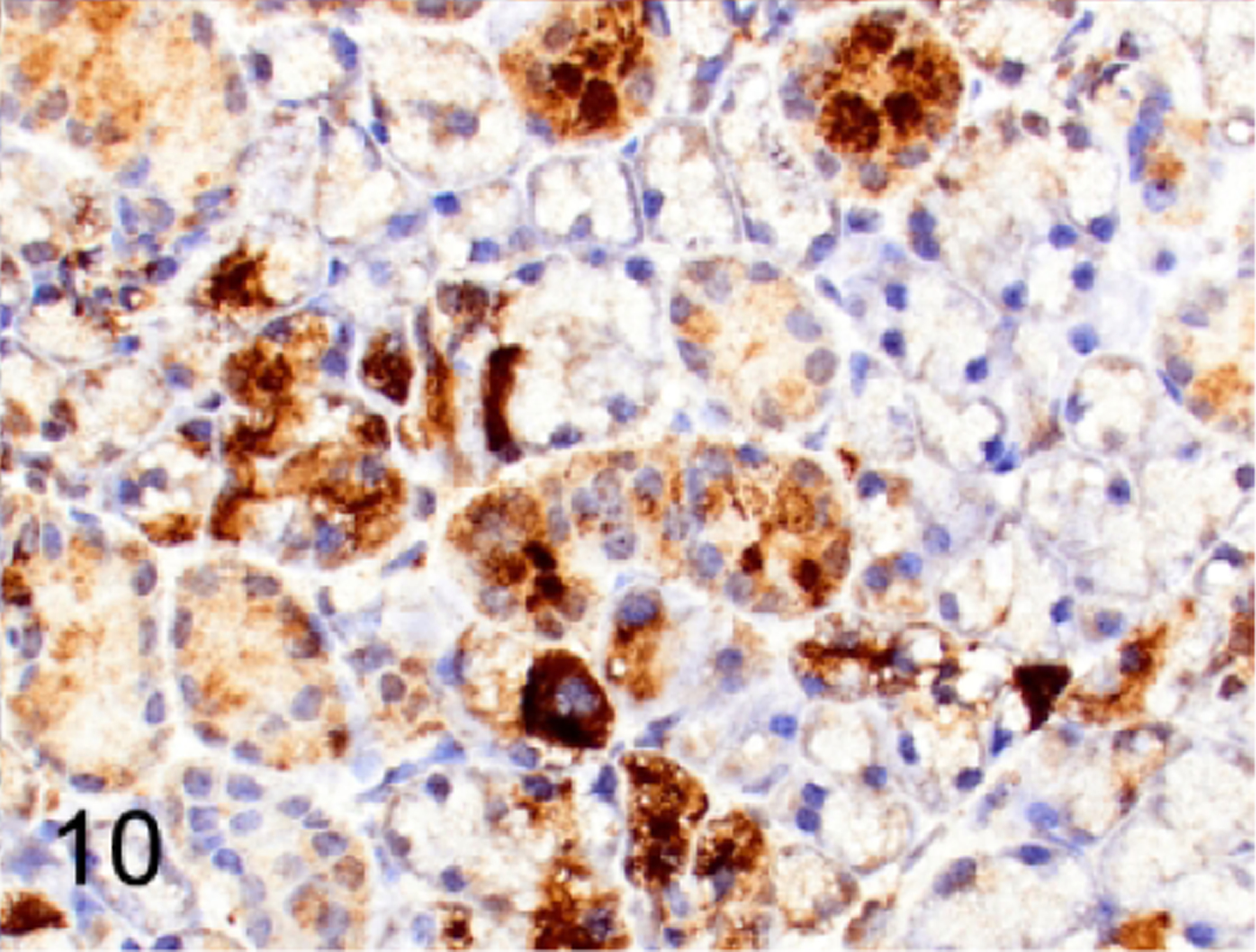

Because retroviral infection is correlated with spontaneous lymphomagenesis in mice, we assessed sections of lymphoma within the spleen, thymus, bone marrow, liver, lung, lymph nodes and salivary gland for immunoreactivity with retroviral p30 antibody. Strong expression of p30 antigen was detected by IHC in 8 of 12 lymphomas (67%, Figure 8). The neoplastic lymphocytes in the other 4 of 12 mice (33%) had low intensity to equivocal labeling for p30. However, p30 was detected in normal megakaryocytes in spleen or bone marrow (Figure 9) and in acinar and ductal epithelium of salivary glands (Figure 10) and mammary glands (not shown) in all 12 NSG mice with lymphoma. We also confirmed that there was p30 expression in the same tissues in two naïve NSG mice, one male and one female, which did not have either clinical or histopathologic evidence of disease.

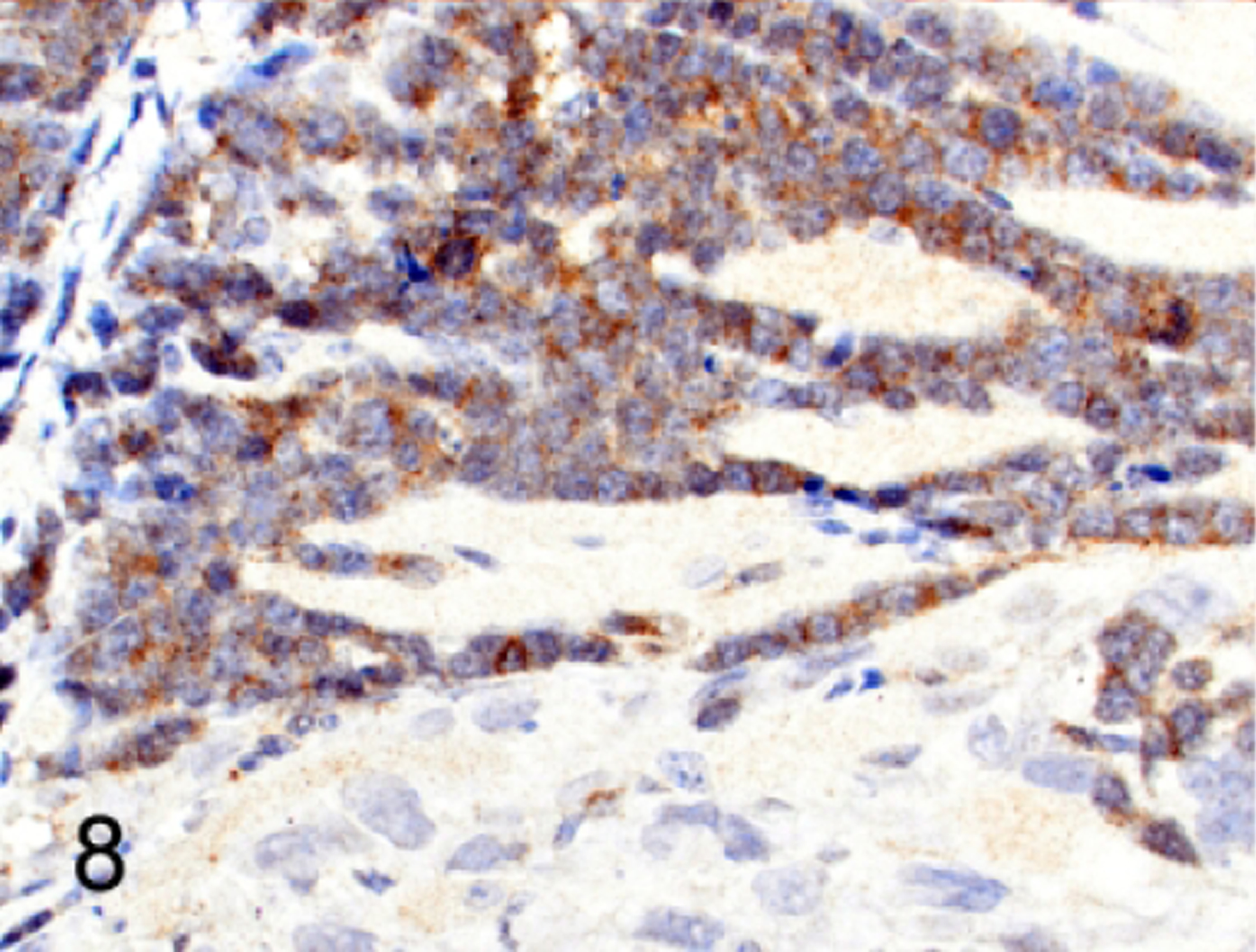

Figure 8.

Lymphoma, upper femur, NSG mouse, case 3. Murine lymphoma cells have cytoplasmic immunoreactivity for retroviral p30. The adjacent human solid xenograft tumor cells are negative for p30.

Figure 9.

Human lymphoma engrafted into mouse bone marrow, sternum, case 1. NSG bone marrow megakaryocytes are immunolabeled for retroviral protein p30 adjacent to an area where human B lymphoblastic lymphoma cells have engrafted. There are scattered bone marrow stromal cells that also have immunoreactivity for p30. The human B-LBL cells are negative for p30.

Figure 10.

Normal submandibular salivary gland, NSG mouse, case 5. Scattered acini and many ductal epithelia are immunolabeled for p30.

DISCUSSION

Our findings indicate that progenitor lymphoid cells in NSG mice have the potential to undergo neoplastic transformation and form lymphomas/leukemias that most closely identify with precursor T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia as described in the Bethesda classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice.42 The lymphomas were TDT+ and either double-positive (CD4+CD8+) or single-positive (CD4+ only) further supporting the diagnosis of a T-cell lymphoma arising from immature populations. Tdt is a transcriptional regulator that is responsible for generating N-diversity during the V(D)J recombination process. This lymphocyte-specific antigen is expressed in immature cells during lymphocyte development. Specifically, it is expressed in the early maturational stages including pro-T, pre-T and DP T cells as well as pro-B cells in mice.16,47 T-cell maturation stages can be assessed using IHC approaches although overlap in marker expression exists between some stages. Additionally, the development of neoplasms may not follow the normal patterns of differentiation. Therefore, it is not always possible to provide a clear distinction between pro-T and pre-T cell subsets, cortical thymocytes (CD4+CD8+, DP), medullary thymocytes (CD4+CD8- SP or CD8+CD4- SP) and post thymic T cells (CD4+CD8- SP or CD8+CD4- SP). Therefore, T-cell lymphomas/leukemias can sometimes only be classified broadly as either immature (TDT+) or mature (TDT-) based on whether or not they express TDT when using IHC only.53,54

Half of the NSG lymphomas in this report were positive for CD25, which is more commonly used to identify early developmental stages of T cells in mice. Human T-cell leukemias/lymphomas universally overexpress CD25.71 It is hypothesized that CD25 permits cell proliferation, expansion and survival, which account for the poor outcome associated with lymphoid neoplasms expressing this marker.18,76 CD5 is another marker used for assessing T-cell development and is expressed on most immature and mature T cells and NKT cells. Five of the 12 lymphoma/leukemias expressed CD5 while most did not appear to have detectable levels. CD5 loss is not uncommon for T-cell lymphomas/leukemias and helps to further distinguish that the lymphoproliferations observed in the 12 NSG mice were neoplastic.53 All lymphomas were negative for CD117. Loss of CD117 suggests that lymphomas do not have an early T-cell precursor phenotype. CD117 has a role in the expansion of CD3-CD4-CD8- T cell progenitors of bone marrow origin, which are not irreversibly committed to the T cell lineage and may progress towards either myeloid or dendritic cell differentiation.57,58 Indeed, the NSG lymphomas were negative for other myeloid markers. Therefore, the clinical findings, morphology and immunophenotype are sufficient to support that the spontaneous lymphoproliferations in NSG mice are neoplastic.

When histopathology and immunophenotyping are unclear, establishing clonality can be helpful for determining whether or not a lymphoproliferation is neoplastic or a benign hyperplasia. Establishing clonality for T-cell malignancies is not always straightforward as the expansion of T-cell subclones is necessary for antigen-specific responses. Therefore, predominance of T-cell clones may occur in some reactive conditions. Because the presence of clonal T-cell populations does not prove malignancy it cannot be relied upon as a gold standard for diagnosing such diseases alone. Molecular techniques, such as tests of clonality, are considered to be beneficial in a minority of human lymphoma cases and only when used in conjunction with morphology and immunophenotyping. Using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded samples to determine clonality also provides challenges in testing and the consistent interpretation of results.6,33,66 In all, our interpretation that the NSG lymphoproliferations are consistent with the diagnosis of lymphomas are comparable to what is described for the immunophenotype of pediatric T lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma, which is also derived from immature T cells.9,47,50

The overall incidence of T-cell lymphoma in our NSG mice is similar to what has been reported for NOG mice, which is around 0.7%.28 NOG and NSG mouse colonies appear to develop lymphoma at a lower frequency than what has been reported for lymphomas arising in either NOD-scid mice (67%) or C.B-17-scid mice (15–20%).15,43,46 The differences in lymphomagenesis among these strains may be related to the functions of any residual immune cell subpopulations or from environmental exposures. While the NSG and NOG mice examined in our report and other published studies have small sample sizes, are often limited in the scope of available clinical data, and subject to selection biases, the potential differences in tumor frequencies and growth kinetics still warrant further examination and comparison with other immunodeficient mice. Understanding the mechanisms of lymphomagenesis in NSG mice may help to better discern the role of the IL2Rϒ chain in lymphomagenesis.

One key question that our study highlights is the mechanism by which spontaneous lymphomas develop in a subpopulation of susceptible NSG mice. The disruption of the thymic niche in mice that have loss of IL2Rϒ alone or in combination with a RAG deficiency can result in thymocytes acquiring genetic alterations leading to T-cell lymphomagenesis. In one study the engraftment of newborn thymic tissue into T-cell deficient Rag−/−ϒc −/−KitW/Wv mice caused autonomous T-cell development persisting to the DP stage and transplantable atypical lymphoproliferations in multiple organs. Furthermore, progenitor cells taken from the bone marrow of either Rag2−/− ϒc−/− or ϒc−/− mice and transplanted into wild-type mice could undergo lymphomagenesis, with T-ALL development recorded in 50% and 38% of the mutant mice, respectively. T-ALL did not develop in either the Rag1−/− or KitW/Wv mutant mice in which bone marrow T cell committed progenitors were shown to provide a continuous migration to the thymus.37 These data suggest that thymocytes that cannot respond to essential thymus cytokines and fail to undergo canonical maturation processes, such as the thymocytes of NSG mice, can become genomically unstable.

As previously discussed, the non-neoplastic T-cell phenotype in mice with the C.B-17-scid mutation is CD44-CD25+ (DN3).15,51,59, The NSG lymphomas are predominantly CD4+CD8+ DP and occasionally CD4+CD8- SP, similar to that reported in C.B-17-scid and NOD-scid mice.17,25,28,31 From our data and other published reports the phenotype of lymphomas in mice having a scid mutation alone is characteristic of a more mature DP stage than the DN3 stage. These data suggest other factors are at work in promoting the transition from DN3 to DP in DN3 thymocytes undergoing lymphomagenesis. Defective Trp53, Notch1 mutations, alterations to WNT pathway signaling, upregulation of BCL2 and irradiation have all been implicated in promoting the passage of lymphoma cells from the DN3 blockage into the DP stage of maturation.31,44

Expression of pre-TCR is important for the survival of thymocytes and their progression to maturation. Lymphocytes with the scid phenotype arrest as DN3 thymocytes, which do not express pre-TCR and are expected to undergo cell death in the absence of any genetic changes.59 Wnt pathway signaling, which is suppressed by p53, functions in parallel to the pre-TCR signaling.32,74 Therefore, abrogation of the thymocyte arrest at DN3 via activation of the Wnt pathway or p53 inactivation, may suffice for further immature T-cell development beyond the DN3 thymocyte stage. Inactivation of p53 has been shown to facilitate differentiation of arrested DN3 thymocytes to DP thymocytes.44,74 Over-expression of BCL-2 has also been shown to promote differentiation of thymocytes from the CD4-CD8-CD25+(DN3) to CD4+CD8+ (DP) stage despite their lack of a TCR-CD3 complex in Rag-1 deficient mice.35

NOTCH1 is required for normal T-cell development and plays an important role in regulating β-selection in CD4-CD8- DN thymocytes, but its role in the development of CD4+CD8+ DP thymocytes is not as well established. However, it has been demonstrated in Rag deficient mice that constitutive Notch signaling can promote the progression of DN thymocytes to DP thymocytes in the absence of pre-TCR signaling.39 Notch expression must be precisely regulated as constitutive Notch signaling leads to development of T-cell lymphoma. Chromosomal translocations and acquired gain-of-function mutations affecting NOTCH1 signaling in developing thymocytes of humans and mice cause neoplastic transformation through unlimited self-renewal and a stage-specific developmental arrest.2,21,52 Gain-of-function mutations of Notch genes are frequently associated with mouse models of T-ALL and human T-ALL.38,75 Alterations in Notch have been discovered in a high fraction of mouse lymphomas arising in T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemia prone mice including C.B-17-scid, NOD-scid and Rag deficient mice.3,25,40,73 Notch has also been shown to interact with multiple cellular pathways, and it can cooperate with other oncogenes leading to lymphoma, as occurs with Myc in mouse lymphoma/leukemia models.38,69,75

Another mechanism of lymphomagenesis in NSG mice was explored in this study, that of retroviral-induced transformation. Mouse hematopoietic neoplasms arising from viral infections have previously been reported in mice with or without irradiation, chemical exposure, or genetic manipulation.23,41,48,55 Our data demonstrated that T-cell lymphomas arising in NSG mice can harbor murine retroviruses that can be observed in DP T lymphocytes by immunohistochemistry. The genomes of inbred laboratory mice commonly contain endogenous retroviral elements, including murine leukemia viruses.41 While murine leukemia retrovirus antigen (MuLV) was not initially detected by immunofluorescence labeling methods in T-cell lymphomas that developed in irradiated scid mice,34 the presence of a Type D retrovirus was demonstrated in thymic lymphomas arising in two C.B-17-scid mice.56 Thymic lymphomas in NOD/LtSz-scid mice have been reported to be associated with expression of an endogenous ecotropic murine leukemia provirus (Emv-30) that maps to the proximal region of chromosome 11.51 Interestingly Emv30null NOD-scid mice, which were developed to improve the use of this strain for adoptive transfer studies, still develop thymic lymphomas indicating that other factors are also necessary for T leukemogenesis.61

In humans, random retroviral integration into the host cell DNA may disrupt genes associated with T-cell development, which subsequently leads to an acute T-lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL). In clinical trials, the administration of the ϒc gene into CD34+ bone marrow cells using a gammaretroviral vector to treat IL2RG deficiency in human infants was correlated with the development of T-ALL in a subset of patients. These leukemias were determined to develop from T cells with α/β receptors and had the chromosomal translocation t(11;14). Through cloning and sequencing of host-viral DNA junction fragments, random insertion events at common integration sites beside proto-oncogenes were identified, most notably in association with LMO2, which is implicated in T leukemogenesis.22,71 Thus, it is conceivable that proviral reinsertion of retrovirus near genes that influence growth and apoptosis could also be an important mutagenic event in some NSG lymphomas.

Overexpression of cMyc promotes T-cell and B-cell lymphomagenesis in mice.36 More recently, mutated Notch1 has been shown to contribute to mouse T-cell leukemia by directly inducing the expression of cMyc causing mRNA levels to increase in 14 primary mouse T-cell leukemias that harbored Notch1 mutations.62 They further demonstrated that MuLV was inserted in the Notch1 or cMyc locus of these 14 leukemia lines which likely results in expression of constitutively active Notch1 and cMyc proteins leading to leukemia. These data suggest a mechanism whereby MuLV insertion into either the Notch1 or cMyc locus may account for the occurrence of the lymphomas in the NSG mice in this study.

More recently, an endogenous MuLV that originated from the EMV 30 provirus has been confirmed to be associated with the induction of acute myeloid leukemia in NSG mice.72 The NOD-scid mouse and the NSG mouse share two similar genetically altered mouse genetic backgrounds, the NOD mouse and the C.B-17-Prkdcscid mouse. The NOD mouse originates from the Swiss mouse line, and it is well recognized that lymphomas occur in a variety of mouse strains (CD-1, CFW) of the Swiss background in association with endogenous MuLV.4,55,68 Lymphomas are reported to occur in NOD/LT mice, so it is not surprising they harbor endogenous retroviruses since they are also of the Swiss background. Therefore, our data and that of others support the idea that the NOD/LT mouse is more than likely the source of the retrovirus confirmed to be present in the NOG and NSG mouse.51,72 However, the scid mouse cannot be definitively dismissed as being the source of the retrovirus in the NOG and NSG mice for the BALB/c mouse has also been reported to harbor an ecotropic provirus on chromosome 5, and the C.B-17-scid mouse is of the BALB/c background.4,8,24,30 However, it has been shown that the NOD/LT, NOD-scid and NSG strains harbor the EMV30 provirus suggesting the NOD/LT mouse is the most probable source of the retroviral contamination of the NSG mouse.51,72

The recognition that spontaneous lymphomas arise in NSG has implications for a correct interpretation of pre-clinical research studies. The occurrence and dissemination of two different species-specific lymphomas with morphologic similarities in the same NSG mouse transplanted with human cells highlights that both spontaneous and experimentally induced lymphomas may occur in NSG mice and can be distinguishable with IHC. We have also shown that the retroviral major core protein p30 is detectable by IHC in untransformed tissues and in lymphomas of NSG mice. Therefore, pathologists should be aware of the presence of a retrovirus in the NSG mouse and its possible association with spontaneous T lymphomagenesis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The following authors (HT, LJJ, JER) contributed to the conception or design of the study. All authors contributed to portions of the data acquisition and interpretation (HT, LJJ, AF, PV, JER). The following authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript and critically revising the manuscript (HT, JER). The authors would like to thank Dr. Sandra Ruscetti, the National Cancer Institute, Frederick, Maryland, for providing the goat anti-RLV p30 antibody. Additionally the authors would like to thank Dr. Jerrold M. Ward for his input on MuLV. The research in this study was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute of the National Institutes of Health under the Award Number P30CA021765. The work was also supported in part by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

No author declares a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Araki R, Fujimori A, Hamatani K, et al. Nonsense mutation at Tyr-4046 in the DNA-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit of severe combined immune deficiency mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94(6):2438–2443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Armstrong SA, Look AT. Molecular genetics of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2005;23(26):6306–6315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashworth TD, Pear WS, Chiang MY, et al. Deletion-based mechanisms of Notch1 activation in T-ALL: key roles for RAG recombinase and a conserved internal translational start site in Notch1. Blood 2010;116(25):5455–5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beck JA, Lloyd S, Hafezparast M, et al. Genealogies of mouse inbred strains. Nat Genet 2000;24:23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bene MC, Castoldi G, Knapp W, et al. Proposals for the immunological classification of acute leukemias. European Group for the Immunological Characterization of Leukemias (EGIL). Leukemia 1995;9(10):1783–1786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosma MJ. B and T cell leakiness in the scid mouse mutant. Immunodefic Rev 1992;3(4):261–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosma MJ, Carroll AM. The SCID mouse mutant: definition, characterization, and potential uses. Annu Rev Immunol 1991;9(1):323–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burkhardt B Paediatric lymphoblastic T-cell leukaemia and lymphoma: one or two diseases? Br J Haematol 2010;149(5):653–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor γ chain. Immunity 1995;2(3):223–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll AM, Bosma MJ. T-lymphocyte development in scid mice is arrested shortly after the initiation of T-cell receptor delta gene recombination. Genes Dev 1991;5(8):1357–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll AM, Hardy RR, Petrini J, Bosma MJ. T cell leakiness in scid mice. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 1989;152:117–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiu PPL, Ivakine E, Mortin-Toth S, Danska JS. Susceptibility to Lymphoid Neoplasia in Immunodeficient Strains of Nonobese Diabetic Mice. Cancer Res 2002;62(20):5828–5834. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coughlan AM, Harmon C, Whelan S, et al. Myeloid Engraftment in Humanized Mice: Impact of Granulocyte-Colony Stimulating Factor Treatment and Transgenic Mouse Strain. Stem Cells Dev 2016;25(7):530–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Custer RP, Bosma G, Bosma M. Severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) in the mouse: Pathology, reconstitution, neoplasms. Am J Pathol 1985;120(3):464–477. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Primio R, Trubiani O, Bollum FJ. Ultrastructural localization of Terminal deoxynucleotidyl Transferase (TdT) in rat thymocytes. Thymus 1992;19(3):183–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Di Santo JP, Aifantis I, Rosmaraki E, et al. The common cytokine receptor gamma chain and the pre-T cell receptor provide independent but critically overlapping signals in early alpha/beta T cell development. J Exp Med 1999;189(3):563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flynn MJ, Hartley JA. The emerging role of anti-CD25 directed therapies as both immune modulators and targeted agents in cancer. Br J Haematol 2017;179(1):20–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Foreman O, Kavirayani AM, Griffey SM, Reader R, Shultz LD. Opportunistic bacterial infections in breeding colonies of the NSG mouse strain. Vet Pathol 2011;48(2):495–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gorczyca W, Weisberger J, Liu Z, et al. An approach to diagnosis of T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders by flow cytometry. Cytometry 2002;50(3):177–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grabher C, von Boehmer H, Look AT. Notch 1 activation in the molecular pathogenesis of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Rev Cancer 2006;6(5):347–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hacein-Bey-Abina S, Le Deist F, Carlier F, et al. Sustained correction of X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency by ex vivo gene therapy. N Engl J Med 2002;346(16):1185–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartley JW, Evans LH, Green KY, et al. Expression of infectious murine leukemia viruses by RAW264.7 cells, a potential complication for studies with a widely used mouse macrophage cell line. Retrovirology 2008;5(1):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ihle J, Joseph D, Domotor J. Genetic linkage of C3H/HeJ and BALB/c endogenous ecotropic C-type viruses to phosphoglucomutase-1 on chromosome 5. Science 1979;204(4388):71–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jeannet R, Mastio J, Macias-Garcia A, et al. Oncogenic activation of the Notch1 gene by deletion of its promoter in Ikaros-deficient T-ALL. Blood 2010;116(25):5443–5454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jhappan C, Morse HC 3rd, Fleischmann RD, Gottesman MM, Merlino G. DNA-PKcs: a T-cell tumour suppressor encoded at the mouse scid locus. Nat Genet 1997;17(4):483–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kataoka S, Satoh J, Fujiya H, et al. Immunologic Aspects of the Nonobese Diabetic (NOD) Mouse: Abnormalities of Cellular Immunity. Diabetes 1983;32(3):247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kato C, Fujii E, Chen YJ, et al. Spontaneous thymic lymphomas in the non-obese diabetic/Shi-scid, IL-2R gamma (null) mouse. Lab Anim 2009;43(4):402–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozak C, Rowe W. Genetic mapping of the ecotropic murine leukemia virus-inducing locus of BALB/c mouse to chromosome 5. Science 1979;204(4388):69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lai L, Liu H, Wu X, Kappes JC. Moloney Murine Leukemia Virus Integrase Protein Augments Viral DNA Synthesis in Infected Cells. J Virol 2001;75(23):11365–11372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lieberman M, Hansteen GA, Waller EK, Weissman IL, Sen-Majumdar A. Unexpected effects of the severe combined immunodeficiency mutation on murine lymphomagenesis. J Exp Med 1992;176(2):399–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Linette GP, Grusby MJ, Hedrick SM, Hansen TH, Glimcher LH, Korsmeyer SJ. Bcl-2 is upregulated at the CD4+ CD8+ stage during positive selection and promotes thymocyte differentiation at several control Points. Immunity 1994;1(3):197–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marinkovic D, Marinkovic T, Mahr B, Hess J, Wirth T. Reversible lymphomagenesis in conditionally c-MYC expressing mice. Int J Cancer 2004;110(3):336–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martins VC, Busch K, Juraeva D, et al. Cell competition is a tumour suppressor mechanism in the thymus. Nature 2014;509(7501):465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medeiros LJ, You MJ, Hsi ED. T-Lymphoblastic Leukemia/Lymphoma. Am J Clin Pathol 2015;144(3):411–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michie AM, Chan AC, Ciofani M, et al. Constitutive Notch signalling promotes CD4 CD8 thymocyte differentiation in the absence of the pre-TCR complex, by mimicking pre-TCR signals. Int Immunol 2007;19(12):1421–1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Minuzzo S, Agnusdei V, Pusceddu I, et al. DLL4 regulates NOTCH signaling and growth of T acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells in NOD/SCID mice. Carcinogenesis 2015;36(1):115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morse HC 3rd: Retroelements in the Mouse. In: Fox J, ed. The Mouse in Biomedical Research Burlington, MA: Academic Press; 2007: 269–279. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morse HC 3rd, Anver MR, Fredrickson TN, et al. Bethesda proposals for classification of lymphoid neoplasms in mice. Blood 2002;100(1):246–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murphy WJ, Durum SK, Anver MR, et al. Induction of T cell differentiation and lymphomagenesis in the thymus of mice with severe combined immune deficiency (SCID). J Immunol 1994;153(3):1004–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nacht M, Strasser A, Chan YR, et al. Mutations in the p53 and SCID genes cooperate in tumorigenesis. Genes Dev 1996;10(16):2055–2066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nakajima H, Noguchi M, Leonard WJ. Role of the common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc) in thymocyte selection. Immunol Today 2000;21(2):88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nishimura M, Wakana S, Kakinuma S, et al. Low frequency of Ras gene mutation in spontaneous and gamma-ray-induced thymic lymphomas of scid mice. Radiat Res 1999;151(2):142–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Notarangelo LD, Kim M-S, Walter JE, Lee YN. Human RAG mutations: biochemistry and clinical implications. Nat Rev Immunol 2016;16(4):234–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.O’Brien SJ, Simonson JM, Davis S. Deposition of retrovirus associated antigens (p30 and gp70) on cell membranes of feline and murine leukaemia virus infected cells. J Gen Virol 1978;38(3):483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ohbo K, Suda T, Hashiyama M, et al. Modulation of hematopoiesis in mice with a truncated mutant of the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain. Blood 1996;87(3):956–967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Patel JL, Smith LM, Anderson J, et al. The immunophenotype of T-lymphoblastic lymphoma in children and adolescents: a Children’s Oncology Group report. Br J Haematol 2012;159(4):454–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Prochazka M, Gaskins HR, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. The nonobese diabetic scid mouse: model for spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1992;89(8):3290–3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pui CH, Robison LL, Look AT. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 2008;371(9617):1030–1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rehg J, Ward J. Application of immunohistochemistry in toxicologic pathology of the hematolymphoid system. In: Parker G, ed. Immunopathology in Toxicology and Drug Development: Volume 1, Immunobiology, Investigative Techniques, and Special Studies New York: Springer International Publishing; 2017: 489–551. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rehg JE, Bush D, Ward JM. The Utility of Immunohistochemistry for the Identification of Hematopoietic and Lymphoid Cells in Normal Tissues and Interpretation of Proliferative and Inflammatory Lesions of Mice and Rats. Toxicol Pathol 2012;40(2):345–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rehg JE, Rahija R, Bush D, Bradley A, Ward JM. Immunophenotype of Spontaneous Hematolymphoid Tumors Occurring in Young and Aging Female CD-1 Mice. Toxicol Pathol 2015;43(7):1025–1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ristevski S, Purcell DF, Marshall J, et al. Novel endogenous type D retroviral particles expressed at high levels in a SCID mouse thymic lymphoma. J Virol 1999;73(6):4662–4669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rodewald H-R, Kretzschmar K, Swat W, Takeda S. Intrathymically expressed c-kit ligand (stem cell factor) is a major factor driving expansion of very immature thymocytes in vivo. Immunity 1995;3(3):313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodewald H-R, Ogawa M, Haller C, Waskow C, DiSanto JP. Pro-Thymocyte Expansion by c-kit and the Common Cytokine Receptor γ Chain Is Essential for Repertoire Formation. Immunity 1997;6(3):265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rothenberg EV, Chen D, Diamond RA. Functional and Phenotypic Analysis of Thymocytes in Scid Mice - Evidence for Functional-Response Transitions before and after the Scid Arrest Point. J Immunol 1993;151(7):3530–3546. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Santagostino SF, Arbona RJR, Nashat MA, White JR, Monette S. Pathology of Aging in NOD scid gamma Female Mice. Vet Pathol 2017;54(5):855–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Serreze DV, Leiter EH, Hanson MS, et al. Emv30null NOD-scid Mice: An Improved Host for Adoptive Transfer of Autoimmune Diabetes and Growth of Human Lymphohematopoietic Cells. Diabetes 1995;44(12):1392–1398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sharma VM, Calvo JA, Draheim KM, et al. Notch1 contributes to mouse T-cell leukemia by directly inducing the expression of c-myc. Mol Cell Biol 2006;26(21):8022–8031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shultz LD, Goodwin N, Ishikawa F, Hosur V, Lyons BL, Greiner DL. Human cancer growth and therapy in immunodeficient mouse models. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2014;2014(7):694–708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, et al. Human Lymphoid and Myeloid Cell Development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2R null Mice Engrafted with Mobilized Human Hemopoietic Stem Cells. J Immunol 2005;174(10):6477–6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shultz LD, Schweitzer PA, Christianson SW, et al. Multiple defects in innate and adaptive immunologic function in NOD/LtSz-scid mice. J Immunol 1995;154(1):180–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Suzuki K, Nakajima H, Saito Y, Saito T, Leonard WJ, Iwamoto I. Janus kinase 3 (Jak3) is essential for common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc)-dependent signaling: comparative analysis of γc, Jak3, and γc and Jak3 double-deficient mice. Int Immunol 2000;12(2):123–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Taddesse-Heath L, Chattopadhyay SK, Dillehay DL, et al. Lymphomas and high-level expression of murine leukemia viruses in CFW mice. J Virol 2000;74(15):6832–6837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tan Q, Brunetti L, Rousseaux MWC, et al. Loss of Capicua alters early T cell development and predisposes mice to T cell lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2018;115(7):E1511–E1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tangye SG, Pelham SJ, Deenick EK, Ma CS. Cytokine-Mediated Regulation of Human Lymphocyte Development and Function: Insights from Primary Immunodeficiencies. J Immunol 2017;199(6):1949–1958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Thrasher AJ, Gaspar HB, Baum C, et al. Gene therapy: X-SCID transgene leukaemogenicity. Nature 2006;443(7109):E5–6; discussion E6–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Triviai I, Ziegler M, Bergholz U, et al. Endogenous retrovirus induces leukemia in a xenograft mouse model for primary myelofibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2014;111(23):8595–8600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tsuji H, Ishii-Ohba H, Noda Y, Kubo E, Furuse T, Tatsumi K. Rag-dependent and Rag-independent mechanisms of Notch1 rearrangement in thymic lymphomas of Atm(−/−) and scid mice. Mutat Res 2009;660(1–2):22–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wu L, Strasser A: “Decisions, decisions ...”. β-catenin–mediated activation of TCF-1 and Lef-1 influences the fate of developing T cells. Nat Immunol 2001;2:823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.You Q, Su H, Wang J, Jiang J, Qing G, Liu H. Animal models of T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia: mimicking the human disease. Journal of Bio-X Research 2018;1(1):32–40. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yui MA, Feng N, Rothenberg EV. Fine-scale staging of T cell lineage commitment in adult mouse thymus. J Immunol 2010;185(1):284–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.