Abstract

Oxygen (O2) toxicity remains a concern, particularly to the lung. This is mainly related to excessive production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). Supplemental O2, i.e. inspiratory O2 concentrations (FIO2) > 0.21 may cause hyperoxaemia (i.e. arterial (a) PO2 > 100 mmHg) and, subsequently, hyperoxia (increased tissue O2 concentration), thereby enhancing ROS formation. Here, we review the pathophysiology of O2 toxicity and the potential harms of supplemental O2 in various ICU conditions. The current evidence base suggests that PaO2 > 300 mmHg (40 kPa) should be avoided, but it remains uncertain whether there is an “optimal level” which may vary for given clinical conditions. Since even moderately supra-physiological PaO2 may be associated with deleterious side effects, it seems advisable at present to titrate O2 to maintain PaO2 within the normal range, avoiding both hypoxaemia and excess hyperoxaemia.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s13054-021-03815-y.

Keywords: Hyperoxia, Hyperoxaemia, Reactive oxygen species, Reactive nitrogen species, ARDS, Sepsis, Trauma-and-haemorrhage, Traumatic brain injury, Subarachnoidal bleeding, Acute ischaemic stroke, Intracranial bleeding, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation, Myocardial infarction, Surgical site infection

Background

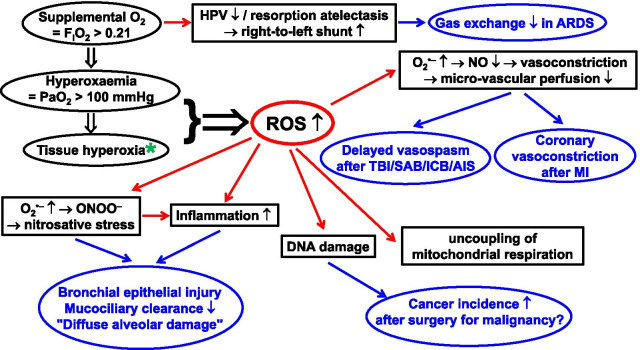

Since its discovery [1–3], oxygen (O2) has been recognised as “friend and foe” [4]. It is vital for aerobic respiration within the mitochondria, yet mitochondrial respiration also forms reactive oxygen species (ROS) [5], production of which relates to O2 concentration [6–8]. Supplemental O2, i.e. inspiratory O2 concentrations (FIO2) > 0.21, may cause hyperoxaemia (arterial PO2 > 100 mmHg) and subsequently increased ROS formation [9–11]. This is particularly pronounced during ischaemia/reperfusion (I/R) and/or hypoxia/re-oxygenation [6–8]. ROS are as “Janus-headed” as O2: ROS are vital for host defence, and also toxic [12]. Consequently, O2 toxicity, especially pulmonary, is a matter of concern [13–15], and optimal dosing remains unclear in critical care. This review discusses potential harms of O2 in various underlying critical illnesses. Figure 1 summarises the possible dangers of hyperoxia, highlighting pathophysiological mechanisms and their impact on specific disease conditions. The most important clinical studies are listed in Table 1; “Additional file 1” shows the complete study list.

Fig. 1.

Potential harm of hyperoxia. AIS acute ischaemic stroke; MI myocardial infarction; ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome; FIO2 fraction of inspired O2; HPV hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction; ICB intracranial bleeding; PaO2 arterial O2 partial pressure; NO nitric oxide; ONOO‒ peroxynitrite; O2•‒ superoxide anion; ROS reactive oxygen species; SAB subarachnoidal bleeding; TBI traumatic brain injury. * Note that while hyperoxia and hyperoxaemia are well defined as FIO2 > 0.21 and PaO2 > 100 mmHg, respectively, there is no general threshold for “tissue hyperoxia”, because the normal tissue PO2 depends on the macro- and microcirculatory perfusion and the respective metabolic activity. Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that PO2 levels as low as 0.3 – 0.7 mmHg suffice for correct functioning of the mitochondrial respiratory chain [17, 162]

Table 1.

Main features of the studies discussed in the text. ABG arterial blood gas; ACS acute coronary syndrome; AIS acute ischaemic stroke; AMI acute myocardial infarction; CI confidence interval; CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ED emergency department; GCS Glasgow coma score; GOSE Glasgow outcome scale extended; ICU intensive care unit; IQR interquartile range; ICB intracranial bleeding; mo month; MV mechanical ventilation; OR odds ratio; RCT randomised controlled trial; ROSC return of spontaneous circulation; SAB subarachnoidal bleeding; SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SpO2 pulse oximetry haemoglobin O2 saturation; SOFA sequential organ failure assessment; SSI surgical site infection; STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; TBI traumatic brain injury; TWA time-weighted average

| Study name | Design/sample size | Setting | Oxygenation parameter | Major findings | Ref. no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOTA | Meta-analysis/25 RCT, n = 16,037 | General ICU | “Conservative” vs. “Liberal”, i.e. lower vs. higher target according to individual study design | Higher mortality risk (relative risk 1.21 [95%CI 1.0–1.43]) with “liberal” O2 strategy (median baseline SpO2 96% [IQR 96–98%]) | 38 |

| ICU-ROX | Multicentre RCT/n = 965 | General ICU; MV | “Conservative” (lowest FIO2 possible keeping SpO2 between 91 and 97%) vs. “Usual” (no limit) | No difference in day 28 ventilator-free days and day 90/180 mortality | 39 |

| PROSPERO | Meta-analysis + Trial Sequential Analysis/36 RCT, n = 20,166 | General ICU | “Lower” vs. “Higher”, i.e. lower vs. higher target according to individual study design | No difference in mortality or morbidity | 42 |

| O2-ICU | Multicentre RCT/n = 400 | General ICU; expected ICU stay > 2 days; ≥ 2 SIRS criteria | Oxygenation target: PaO2 8–12 vs. 14–18 kPa (≈ 60–90 vs. 105–135 mmHg) | No difference in SOFA score; limitation: PaO2 < target in “high-normal oxygenation” group | 43 |

| LOCO2 | Multicentre RCT/n = 205 | ARDS | “Conservative” (PaO2 55–70 mmHg, SpO2 88–92%) vs. “Liberal” (PaO2 90–105 mmHg, SpO2 ≥ 96%) until day 7 | Premature halt for higher mortality in “Conservative” group (day 28: 34.3 vs. 26.5%; day 90: 44.4 vs. 30.4%); limitation: > 50% patients had PaO2 > upper level | 63 |

| HOT-ICU | Multicentre RCT / n = 2,888 | General ICU; acute hypoxemic respiratory failure | “Lower” (PaO2≈60 ± 7.5 mmHg) vs. “Higher” (PaO2≈90 ± 7.5 mmHg) | No difference in day 90 mortality | 64 |

| LUNG SAFE | Sub-study of multicentre, prospective, cohort study/ n = 2,005 | ARDS | Presence of day 1 “hyperoxemia” PaO2 > 100 mmHg), “sustained” (day 1 and day 2) or “excessive” O2 (FIO2 ≥ 0.6 + PaO2 > 100 mmHg) | 30% hyperoxaemia day 1, 12% “sustained hyperoxaemia”, 20% “excessive O2” | 65 |

| IMPACT | Multicentre retrospective/n = 16,326 | CPR; ABG within 24 h | PaO2 < 60 (“hypoxia”), 60–300 (“normoxia”), ≥ 300 mmHg (“hyperoxia”) | PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg significantly higher mortality 63(CI:60–66)% vs. normoxia 45[CI43-48]%) vs. hypoxia (57[CI56-59]%) | 68 |

| HYPER2S | Multicentre RCT/n = 442 | Septic shock within first 6 h; MV | FIO2 = 1.0 during first 24 h vs. “standard treatment” | Premature safety stop for higher mortality with “FIO2 = 1.0” (day 28: 43 vs. 35%, p = 0.12; day 90: 48 vs. 42%, p = 0.16); lower number of ventilator-free days, more serious adverse events despite lower SOFA at day 7 | 75 |

| HYPER2S | Post hoc analysis of multicentre RCT/n = 393 | Septic shock within first 6 h according to Sepsis-3; MV | FIO2 = 1.0 during first 24 h vs. “standard treatment” | Higher mortality with “FIO2 = 1.0” and lactate > 2 mmol/L (day 28: 57 vs. 44%); no effect lactate ≤ 2 mmol/L | 76 |

| ICU-ROX | Post hoc analysis of multicentre RCT/n = 251 | Sepsis; MV | “Conservative” (lowest FIO2 possible keeping SpO2 between 91 and 97%) vs. “Usual” (no limit) | Mortality day 90 “Conservative” 36.2 vs. “Usual” 29.2% (p = 0.24); “…point estimates of treatment effects consistently favoured usual O2 therapy…” | 77 |

| Multicentre, retrospective/n = 1,116 | TBI; MV | PaO2 < 10.0 kPa (≈ < 75 mmHg) or 10.0–13.3 kPa (≈ 75-100 mmHg) or PaO2 > 13.3 kPa (≈ > 100 mmHg) | PaO2 > 13.3 kPa no relationship to outcome | 86 | |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 2,894 | MV; 19% AIS, 32% SAB, 49% ICB | PaO2 < 60, 60–300 or ≥ 300 mmHg | PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg in-hospital mortality 57 vs. 46/47% (p < 0.001) | 87 | |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 432 | SAB; MV | 24 h TWA PaO2: “low”/“intermediate”/“high” (< 97.5/97.5–150/ > 150 mmHg) | TWA-PaO2: survivors 118(IQR90-155) vs. non-survivors 137(IQR104-167)mmHg (p < 001); multivariate analysis no relation between TWA-PaO2 and outcome | 91 | |

| SO2S | Multicentre RCT/n = 7,635 | AIS | Continuous (2-3L/min) vs. nocturnal nasal O2 vs. control | No difference in mortality and neurological outcome | 92 |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 24,148 | TBI; MV | PaO2 50 mmHg-increments; hyperoxia PaO2 > 300 mmHg | No relation PaO2 vs. mortality except for PaO2 < 60 mmHg and GCS > 12 | 93 | |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 3,699 | TBI; MV | PaO2 < 60, 60–300 vs. PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg | No relation PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg vs. GOSE < 5 at 6 mo | 95 | |

| Single centre retrospective/n = 688 | ED; MV, normoxia (PaO2 60-120 mmHg) on day 1 ICU | Hypoxia/normoxia/hyperoxia PaO2 < 60, 60–120, > 120 mmHg | Hyperoxia present in 43%; mortality 29.7 vs. 19.4 (normoxia) and 13.2 (hypoxia) % (p = 0.021 vs. normoxia) | 109 | |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 3,464 | Polytrauma; ICU within 24 h | Patient-hours with SpO2 90–96% (“normoxia”) vs. > 96% (“hyperoxia”); hyperoxia in 10%- FIO2 increments until d3 and d4-7 | Increased risk of mortality with higher FIO2 during hyperoxia | 114 | |

| IMPACT | Post hoc of multicentre retrospective/n = 4,459 | CPR; ABG within 24 h | Highest PaO2 24 h ICU | 100 mmHg PaO2-increments 24% mortality risk increase (OR1.24[CI1.18–1.31]) | 121 |

| Multicentre prospective/n = 280 | CPR; therapeutic hypothermia | PaO2 > 300 mmHg 1 or 6 h post-ROSC | 3% (OR1.03[CI1.02–1.05]) risk increase in poor neurological outcome per 1 h hyperoxia duration | 124 | |

| Multicentre retrospective/n = 12,108 | CPR; therapeutic hypothermia | PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg within 24 h | PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg mortality 59(CI56-61)% vs. 47(CI45-50% (60-300 mmHg)/58(CI57-58)% (< 60 mmHg) | 125 | |

| FINNRESUSCI | Multicentre prospective/n = 409 | CPR out-of-hospital | PaO2 < 75 (“low”), 75–150 (“middle”), 150–225 (“intermediate”), PaO2 > 225 mmHg (“high”) | No association between hyperoxia and neurological outcome | 126 |

| TTM | Post hoc analysis of multicentre RCT/n = 869 | CPR out-of-hospital; therapeutic hypothermia | PaO2, TWA PaO2 37 h post-ROSC; PaO2 > 40 kPa (≈PaO2 > 300 mmHg), 8 ≤ PaO2 ≤ 40 (≈60 ≤ PaO2 ≤ 300 mmHg), PaO2 < 8 kPa (≈PaO2 < 60 mmHg) | No association with 6-mo neurological outcome | 129 |

| Meta-analysis/7 RCT, n = 429 | CPR | “Higher” (“liberal”) vs. “lower” (“conservative”) O2 target | Mortality 50% liberal vs. 41% conservative, p = 0.04 | 130 | |

| ICU-ROX | Post hoc analysis of multicentre RCT/n = 166 | “Suspected hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy”; MV | “Conservative” (lowest FIO2 possible 91 ≤ SpO2 < 97%) vs. “Usual” (no limit) | Day 180: mortality 43% conservative vs. 59% “usual” (p = 0.15); “unfavourable neurological outcome” 55% conservative vs. 68% usual (p = 0.15) | 134 |

| DETO2X-SWEDEHEART | Multicentre RCT/n = 6629 | AMI | 6L/minO2 6-12 h | No effect on 1-year outcome | 138 |

| Oxygen Therapy in Acute Coronary Syndromes | Multicentre crossover RCT/n = 40,872 | ACS | 6-8L/minO2 vs. SpO2 90–95% | No effect on day 30-mortality | 140 |

| PROXI | Multicentre RCT/n = 1,386 | Elective/acute laparotomy | FIO2 0.8 vs. 0.3 until 2 h post-op | FIO2 0.8 19.1% vs. FIO2 0.3 20.1% SSI (p = 0.64) | 143 |

| Supplemental Oxygen in Colorectal Surgery | Single centre prospective/n = 5,749 | Major intestinal surgery > 2 h | FIO2 = 0.8 vs. 0.3 every 2 weeks alternating intervention study | 30d-SSI FIO2 = 0.8 10.8 vs. 11.0% (p = 0.85) | 144 |

| Intraoperative Inspiratory Oxygen Fraction and Postoperative Respiratory Complications | Multicentre retrospective/n = 79,322 | General surgery | Quintiles FIO2 0.31, 0.41, 0.52, 0.79 | Dose-dependent association FIO2 vs. day 7 “Major respiratory complications composite” and vs. day 30-mortality | 151 |

| WHO Meta-analysis/12 RCT, n = 5,976 | General surgery | FIO2 0.8 vs. 0.30–0.35 | FIO2 = 0.8 reduces SSI risk vs. 0.30–0.35 (OR0.80[CI0.64–0.99], p = 0.043): only general anaesthesia with tracheal intubation | 153 | |

| Single centre RCT/n = 210 | Open surgery for appendicitis | FIO2 = 0.8 vs. 0.30 until 2 h post-op | FIO2 = 0.8 SSI 5.6 vs.13.6% (p = 0.04); hospital stay 2.51 vs. 2.92 (p = 0.01) | 156 | |

| Cochrane Perioperative Oxygen Review | Meta-analysis/10 RCT, n = 1,458 | General surgery | “Higher” vs. “lower” FIO2 | “Higher” vs. “lower” FIO2 “very low evidence” serious adverse event risk | 157 |

| Meta-analysis/12 trials, n = 28,984 | General ICU; MV | FIO2 “low” vs. “high” (as defined by authors) | FIO2 “high”; no impact on pneumonia, ARDS, MV duration; FIO2 ≥ 0.8 increased risk of: atelectasis | 158 |

Pathophysiology

Oxygen generally exists as di-atomic molecule (O2); its two atoms bond to each other through single bonds leaving two unpaired electrons. O2 performs its actions through these unpaired electrons which act as radicals. ROS are even more reactive molecules formed through oxygen’s electron receptivity (e.g. superoxide, peroxide, and hydroxyl anion).

Over 90% of O2 consumption is utilised by mitochondria, predominantly for ATP production (oxidative phosphorylation), but also for heat generation through uncoupling, and superoxide production. O2 is the terminal electron acceptor at Complex IV of the electron transport chain (ETC), being reduced to water in this process. For each mole of glucose metabolised, anaerobic respiration (glycolysis) generates only 2 ATP moles compared to approximately 28–30 from oxidative phosphorylation. In health, 1–3% of mitochondrial O2 consumption is used at the ETC Complexes I and III to generate superoxide, an important signalling molecule [16]. Superoxide is necessary for enzyme processes, e.g. oxidases (catalysing oxidation–reduction reactions) and oxygenases (incorporating oxygen into a substrate). Activated immune cells utilise O2 for extra-mitochondrial ROS production: NADPH oxidase generates superoxide (“respiratory burst”) for phagocytosis. Unless overwhelmed by ROS over-production, antioxidant capacity (e.g. superoxide dismutase, glutathione, thioredoxin) prevents oxidative damage to DNA, proteins and lipids, and subsequent cell death.

O2 also affects the inflammatory response. Experimental models and volunteer and patient studies demonstrate that hyperoxia (and hypoxia) can induce pro- and anti-inflammatory responses, with both protective and harmful sequelae [17]. Hyperbaric oxygen is used to aid wound healing and treat gas gangrene, but may cause neurotoxicity. Whether the response to hyperoxia relates to its degree and/or duration, specific cell types, background inflammation, or other factors remains uncertain; clearly, O2 toxicity can be induced de novo without underlying pathology, predominant organs being lung, brain, and eye.

Pulmonary toxicity was first described by Lorrain Smith: pure O2 at hyperbaric pressures caused inflammatory pneumonitis [18]. At atmospheric pressure pneumonitis was seen after days in non-human primates breathing 60–100% O2 [19–21]. After initially affecting the airways (tracheobronchitis) with reduced mucociliary clearance [22], the lung parenchyma becomes involved. In humans, this occurs especially when the inspiratory PO2 is significantly enhanced in a hyperbaric environment. Initial complaints are retrosternal chest pain, then coughing and dyspnoea as a pneumonitis develops with pulmonary oedema and diffuse radiological lung shadowing. In healthy volunteers breathing 98–100% O2, chest pain commenced after 14 h, coughing and dyspnoea between 30 and 74 h [22]. Due to nitrogen washout [23], there may also be atelectasis in lung regions with low ventilation/perfusion ratios [24].

Whether hyperbaric vs. normobaric O2 toxicity mechanisms and onset are similar is unclear. Pulmonary injury was accelerated by hyperbaric hyperoxia, but was less inflammatory in character and driven by a neurogenic component that could be blocked by inhibiting neuronal nitric oxide synthase or vagal nerve transection [25]. Possible synergistic effects on O2 toxicity of underlying lung pathology are poorly characterised, especially at the more moderate degrees of hyperoxia inflicted on patients. This is, however, well-recognised with bleomycin toxicity where mild hyperoxia may be damaging [26].

Neurotoxicity was described over a century ago [27]: 3Atm of O2 produced convulsions and death. Seizures or syncope occurred after 40 min at 4Atm O2, and within 5 min at 7Atm [28]. This was usually preceded by milder symptoms such as tunnel vision, tinnitus, twitching, confusion, and vertigo. The impact of high concentration normobaric O2 on neurotoxicity, however, is unclear.

Mitochondrial ROS production increases either with O2 deficit or excess, but particularly during excess O2 (hyperoxia). This can occur in sepsis and/or I/R injury, i.e. whole-body (e.g. resuscitation from cardiac arrest or major haemorrhage), or organ-specific (e.g. revascularisation after myocardial infarction or stroke). A similar injury may be induced by acute hypoxaemia followed by rapid correction (hypoxia/re-oxygenation-injury). The impact of reperfusion injury may be as severe as the ischaemic insult. Although preclinical and clinical studies are not consistent [29–31], reperfusion injury is generally exacerbated by hyperoxia. The hyperoxia effect may be exacerbated by acidification of the hypoxic tissues; the right-shifted oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve of blood (re-)entering the hypoxic tissue augments O2 release, with a subsequent increase in superoxide production [31].

Teleologically, the body has not evolved to deal with high tissue O2 tensions. Tissues not metabolising adequately, e.g. due to toxins or switching off (“hibernating”) in response to hypoperfusion, reduce O2 utilisation. As a normal protective response, negative feedback signals reduce local blood flow by vasoconstriction to mitigate local build-up of O2 and subsequent toxicity. Acute hyperoxia thus induces vasoconstriction, reducing local blood flow [32], particularly in the cerebral and coronary vasculature [5–7]. This vasoconstriction is in part related to reduced release of nitric oxide (NO) from S-nitrosohaemoglobin binding [33]. Vasoconstriction has been shown in patients with and without coronary artery disease, where supplemental O2 reduced cardiac output and coronary sinus blood flow [34, 35]. Seizures associated with neurological O2 toxicity occur with paradoxical vasodilation during hyperbaric hyperoxia [6].

General ICU patients

The Oxygen-ICU trial was the first major study to suggest clinically important harm from liberal O2 administration in a general ICU population [36]. This single-centre, RCT included 480 patients expected to stay in the ICU for at least 72 h. ICU mortality was 20.2% with conventional and 11.6% with conservative O2 therapy. Around two-thirds of patients included were mechanically ventilated at baseline, around a third had shock, and the illness acuity was relatively low. The difference was statistically significant although the study was stopped early after a non-preplanned interim analysis, and the magnitude of the reported treatment effect was larger than hypothesised [36]. Given the variety of mechanisms of death in ICU patients [37], such a high proportion of deaths in a heterogeneous population of ICU patients is unlikely to be attributable to the dose of O2 therapy used. However, the Oxygen-ICU trial [37] did highlight the need for further investigation.

Subsequently, the IOTA systematic review and meta-analysis [38] reported that conservative O2 use in acutely ill adults significantly reduced in-hospital mortality. Although these findings were concordant with the Oxygen-ICU trial [36], they provided only low certainty evidence: First, the Oxygen-ICU trial [36] contributed 32% of the weight to the mortality analysis. Second, predominant conditions were acute myocardial infarction and stroke, and a range of O2 regimens were tested so that the analysis provided only indirect evidence about the optimal O2 regimen for patients in the ICU. Third, the overall mortality treatment effect estimates were imprecise. Finally, an updated systematic review and meta-analysis found no evidence of benefit or harm comparing higher vs. lower oxygenation strategies in acutely ill adults [39].

The multicentre randomised ICU-ROX trial found that conservative O2 therapy did not significantly affect the primary end point of number of days alive and free from mechanical ventilation (ventilator-free days) compared with usual (liberal) O2 therapy [40]. Overall, 32.2% of conservative and 29.7% of usual O2 patients died in hospital. While these findings provide some reassurance to clinicians about the safety of the liberal O2 use that occurs in standard practice, they do not exclude clinically important effects of the O2 regimens tested on mortality risk. Indeed, based on the distribution of data, there is a 46% chance that conservative O2 therapy increases absolute mortality by more than 1.5% points, and a 19% chance that conservative O2 therapy decreases absolute mortality by more than 1.5% points [41, 42]. Finally, a recent RCT conducted in ICU patients fulfilling the systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, found no significant difference between high-normal and low-normal oxygenation targets for non-respiratory organ dysfunction over the first 14 days, or in Day-90 mortality [43]. Accordingly, the most appropriate dose of O2 to give to adult ICU patients remains uncertain.

ARDS

Clinicians should titrate O2 therapy to avoid both hypoxaemia and hyperoxaemia. While the harmful effects of tissue hypoxia are clearly understood [44], over-correction leads to tissue hyperoxia which may also be deleterious. Hyperoxia injures the lung via ROS production, causing oxidant stress with pro-inflammatory and cytotoxic effects [35, 45, 46]. Pathophysiologic consequences include arterial vasoconstriction [35, 47–49], alveolar-capillary “leak” and even fibrogenesis [50, 51]. Clinicians use higher FIO2 than necessary to correct hypoxia in the critically ill [52], possibly to avoid (occult) tissue hypoxia [53, 54], to provide a “buffer” should rapid clinical deterioration occur, or because the consequences of hyperoxia are considered less severe. The lack of clearly defined targets for PaO2 and/or SaO2 is also an issue. The ARDS Network trials targeted a PaO2 of 55-80 mmHg [55], while the British Thoracic Society suggests a target SpO2 of 94–98% in acutely ill patients [56].

In ARDS, the potential for hyperoxia to impact outcomes is further complicated by the severity of gas exchange impairment. Specifically, extreme hyperoxaemia (i.e. PaO2 > 300 mmHg), associated with harm in other critically ill populations, is impossible to achieve in ARDS (see Table 1). However, moderate hyperoxaemia is possible and could be harmful as well [57]. Furthermore, high FIO2 can directly injure the lung [58], sensitise it to subsequent injury [59], adversely affect its innate immune response [60], and worsen ventilation-induced injury [61, 62]. It is therefore necessary to distinguish between hyperoxaemia and high FIO2 use when assessing the effects of hyperoxia on the lung.

The recent LOCO2 trial in ARDS was stopped early for futility and safety concerns regarding mesenteric ischaemia in the conservative O2 group. Moreover, 90-day mortality was significantly higher in patients receiving conservative O2 therapy [63]. The HOT-ICU trial studied ICU patients with acute hypoxaemic respiratory failure and found no difference in 90-day mortality between conservative and liberal PaO2 targets [64]. In the LUNG SAFE observational cohort study, both systemic hyperoxaemia and excess FIO2 use were prevalent, with frank hyperoxaemia (30% of patients) more prevalent than hypoxaemia in early ARDS [65]. Two-thirds of these patients received excess O2 therapy. Hyperoxaemia did not appear to be used as a “buffer” in unstable patients: frequency was similar in shocked patients. While a similar proportion of patients were hyperoxaemic on day-2, higher FIO2 use did decrease. Both hyperoxaemia and excess O2 use were mostly transient, although more sustained hyperoxaemia was seen. Reassuringly, no relationship was found between the degree and duration of hyperoxaemia, or excessive O2 use, and mortality in early ARDS.

While these findings contrast with findings in other ICU cohorts, a key differentiating factor is the reduced potential for extreme hyperoxia in ARDS patients. The potential for harm from hyperoxia appears to be related to the severity of hyperoxaemia [54, 61, 66, 67]; those with relatively preserved lung function are at greatest risk [68]. However, no dose–response relation was found between PaO2 and mortality [67]. Hence, paradoxically, patients with ARDS may be at less risk as they are unable to achieve extreme degrees of hyperoxia. A recent observational study suggested a U-shaped relationship between PaO2 and mortality in ARDS patients; patients with a time-weighted PaO2 of 93.8-105 mmHg had the lowest mortality risk [69]. Intriguingly, this range is near identical to the “liberal” target PaO2 range targeted in the LOCO2 [63]. Hence, much remains to be learned about optimal targeting of PaO2 in patients with ARDS.

Sepsis and septic shock

Theoretically, hyperox(aem)ia might help septic patients due to its vasoconstrictor effect, counteracting hypotension [6–8], and to the antibacterial effects of O2 [70, 71]. However, hyperoxaemia did not affect cardiac output in septic patients [72]. The number of days with PaO2 > 120 mmHg was an independent risk factor for ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) [73]; however, these patients had other risk factors, e.g. more frequent use of proton pump inhibitors and sedatives, higher incidence of circulatory shock with prolonged and higher catecholamine infusion rates, and more red blood cell transfusion. In an observational study on VAP patients, the same group reported that hyperoxaemia did not affect mortality [74]. The HYPER2S RCT [75] compared standard therapy vs. 100% O2 over the first 24 h after diagnosing septic shock. Despite a significantly lower SOFA score at day 7, the trial was prematurely stopped due to higher, albeit not statistically significant mortality in the hyperoxia group at Day-28 and Day-90. The hyperoxia group had significantly more serious adverse events, including ICU-acquired weakness (p = 0.06). A post hoc analysis based on Sepsis-3 criteria found increased Day-28 mortality in patients with hyperlactataemia > 2 mmol/L (p = 0.054), but not with normal lactate levels [76]. The authors speculated that a hyperoxaemia-related increase in tissue O2 availability may have led to excess ROS production and, consequently, oxidative stress-related tissue damage.

The opposite hypothesis, i.e. attenuation of oxidative stress-induced tissue damage by reducing O2 exposure did not beneficially influence outcome in septic patients either. A post hoc analysis of the ICU-ROX trial [40] of the septic cohort showed no statistically significant difference with respect to ventilator-free days or Day-90 mortality for the “conservative” when compared to the “usual” oxygenation [77]. Point estimates of treatment effects even favoured the latter. Hence, it seems reasonable to avoid PaO2 > 100-120 mmHg due to the possible deleterious consequences of excess tissue O2 concentrations in the presence of sepsis-related impairments of cellular O2 extraction [78].

Acute brain injury

Increasing FIO2 in acutely brain-injured patients, alongside other clinical interventions [79], can improve brain tissue PO2 (PbtO2) [80, 81]. The effects of normobaric hyperoxia are less significant in large hypoperfused brain regions [82], but highly relevant in small pericontusional areas [83]. Moreover, incremental FIO2 increased cerebral excitotoxicity in severe traumatic brain injury (TBI) [84]. The association of hyperoxia with outcome is even more controversial. After TBI, both hypoxaemia and hyperoxia were [85] or were not [86] independently associated with worse outcome. In two retrospective studies, including a mixed population of brain-injured patients, hyperoxaemia, defined as PaO2 > 300 mmHg [87] or > 120 mmHg [88], was associated with increased in-hospital mortality and poor neurological outcome, even after adjusting for confounders. Patients with subarachnoid haemorrhage exposed to higher PaO2 levels were also more likely to develop cerebral vasospasm [89, 90]; however, a retrospective analysis of patients needing mechanically ventilation did not find any relation between time-weighted PaO2 and outcome [91]. Studies in acute ischaemic stroke in general [92], and in a sub-group needing mechanical ventilation [93], found no association between outcome and PaO2 within the first 24 h. Even early hyperoxaemia (PaO2 > 300 mmHg) did not affect mortality in mechanically ventilated TBI patients, notwithstanding severity on admission [94, 95]. Finally, PaO2≈150-250 mmHg within the first 24 h post-TBI was associated with better long-term functional outcome after TBI [96]; however, the study excluded patient who died. Normobaric hyperoxia combined with intravenous thrombolysis was associated with more favourable neurological outcome than thrombolysis alone after ischaemic stroke [97].

Prospective studies have evaluated the effects of targeted hyperoxia after acute brain injury: Small studies in patients with acute ischaemic stroke not eligible for thrombolysis found either transient clinical improvement and smaller infarct size with high-flow O2 [98, 99] or no effect of normobaric hyperoxia [100]. In a small RCT in mechanically ventilated TBI patients, FIO2 = 0.8 (vs. 0.5) improved 6-month neurological outcome [101], but conclusions should be cautioned due to methodological concerns. Exposure to FIO2 = 0.7 or 0.4 for up to 14 days after TBI influenced neither markers of oxidative stress or inflammation nor neurological outcome [102]. Finally, the Normobaric-Oxygen-Therapy-in-Acute-Ischemic–Stroke-Trial (NCT00414726) was prematurely halted after inclusion of 85/240 patients because of higher mortality in the high-flow O2 group, although most deaths occurred following early withdrawal of life-support.

It remains open in acute brain injury, whether normoxaemia vs. targeted hyperoxaemia influences brain function and neurological recovery. Optimal PaO2 targets, study populations, and specific forms of brain injury are currently unknown.

Trauma-and-haemorrhage

Supplemental O2 is used because increasing the amount of physically dissolved O2 during blood loss-related reductions in O2 transport is thought to faster repay a tissue O2 debt [103]. Despite its vasoconstrictor properties [6–8], ventilation with 100% O2 during experimental haemorrhage improved tissue PO2 [104] and attenuated organ dysfunction [105, 106].

However, PaO2 > 100 mmHg may enhance ROS formation [9–11], especially during I/R and/or hypoxia/re-oxygenation, e.g. resuscitation from trauma-and-haemorrhage [6–8].

A recent retrospective study in patients with prehospital emergency anaesthesia demonstrated that hyperoxia was present in most patients upon arrival in the hospital, however without relation to outcome [107]. Clinical data on the impact of hyperoxia on morbidity and mortality remain equivocal. No association was seen between mortality and PaO2 in the first 24 h (median Injury Severity Score ISS = 29) [108]. Another observational study noted that 44.5% of patients mechanically ventilated in the emergency department had hyperoxaemia, this cohort having a higher Day-28 mortality [109]. From a French trauma registry (median ISS = 16), univariate analysis showed that admission PaO2 > 150 mmHg coincided with a higher mortality, however, propensity score matching yielded the opposite result, namely supra-physiological PaO2 levels were associated with significantly lower mortality [110]. Lower Day-28 mortality and less nosocomial pneumonia were seen in patients early after blunt chest trauma [111]. An analysis of 864,340 trauma patients (median ISS = 9) investigated the impact of supplemental O2 in the ED; in all three patient categories predefined according to incremental SpO2, supplemental O2 was associated with a significantly higher ARDS incidence and mortality [112]. A retrospective analysis of patients with ISS ≥ 16 studied the impact of PaO2 ≥ 300 mmHg during resuscitation [113]; while prolonged ICU stay was seen in patients not intubated in the ED, no effect was seen in the sicker cohort of mechanically ventilated patients. Finally, a retrospective multicentre study of trauma patients found SpO2 > 96% over the first seven days was common place; the adjusted mortality risk was higher with greater FIO2 [114]. The currently recruiting “Strategy-to-Avoid-Excessive-Oxygen-for-Critically-Ill-Trauma-Patients (SAVE-O2)” (NCT04534959) will address any causality between hyperoxia and outcome.

Despite O2 supplementation being common practice in patients with pronounced blood loss, no optimal target for PaO2 is available.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation and myocardial infarction

During cardiac arrest, PbtO2 drops rapidly to levels close to zero [115]. With cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) PbtO2 increases slowly, driven by the achieved cerebral perfusion pressure [116]. Guidelines recommend ventilation with 100%O2 even though no clinical study has compared this against lower FIO2 [117]. Observational data suggest an association between higher PaO2 during CPR and a higher likelihood of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival, and neurological outcome [118, 119]. After ROSC blood and brain PO2 levels increase; mostly, this appears inevitable as FIO2 titration is impossible during CPR [120]. Given the connection between hyperoxia and ROS formation, there has been great interest in assessing whether avoidance of hyperoxaemia in the post-arrest phase could mitigate brain injury. Results are conflicting, either showing an association between hyperoxia and poor outcome [68, 121–124], or not [125–129]. Smaller randomised trials and sub-group analysis from larger trials have also been performed [130]. Overall, the evidence suggests that lower rather than higher O2 targets are beneficial, even though any sweet spot for optimal PaO2 is unknown [131]. The COMACARE pilot trial compared different PaO2 targets and found no difference in two brain injury biomarkers [132, 133]. A sub-group analysis of the ICU-ROX study showed improved outcomes in restrictive compared to liberal O2 treated patients at risk of hypoxic brain injury [134]. Opposite findings were seen in a sub-group of the HOT-ICU trial [64]. Current guidelines recommend targeting strict normox(aem)ia. The evidence suggests a signal to harm and, importantly, no indication of benefit from extreme hyperox(aem)ia; thus, this should be avoided [135].

Supplemental O2 use has been standard practice for decades in acute myocardial infarction (AMI) [136]. Studies have nonetheless suggested side effects including coronary artery vasoconstriction [137]. Several large studies have shown either harm or lack of benefit from supplemental O2 use in patients without hypoxaemia [138, 139]. A large cluster randomised controlled trial of > 40,000 patients with acute coronary syndrome (including patients with AMI) found no benefit with supplemental O2 use overall, but evidence was inconclusive in patients with ST-elevation AMI [140]. Importantly, these trials included patients without hypoxaemia [138, 140]. Despite the lack of high-quality evidence, it appears prudent to avoid hypoxaemia (SaO2 < 90%) in AMI patients.

Perioperative hyperoxia

Trials of intraoperative hyperoxia have mainly been performed in elective surgery to prevent surgical wound infection through increased tissue oxygenation [141, 142]. Initial enthusiasm was followed by larger trials with similar wound complication frequencies with FiO2 = 0.80 vs. 0.30 perioperatively [143, 144]. Concerns have been raised by shorter cancer-free survival in patients given FiO2 = 0.80 [145, 146]. A higher FIO2 is used to ensure adequate or, in some cases, supranormal end-organ oxygenation, although there is sparse evidence of benefit.

Both preoxygenation and high intraoperative FIO2 can cause resorption atelectasis [147], especially in patients with pulmonary comorbidity, as general anaesthesia itself reduces functional residual capacity and causes airway closure [148]. As ventilation-perfusion mismatch and shunt contribute to impaired oxygenation, use of FIO2 = 0.30–0.35 is therefore considered normal during general anaesthesia [149, 150]. FIO2 ≥ 0.80 caused significant atelectasis during preoxygenation, but this can be eliminated with a recruitment manoeuvre followed by 5-10cmH2O PEEP [14], which clearly is not common practice. Failure to correct such iatrogenic atelectasis may trigger the use of excessive perioperative FIO2. In a large observational study [151], high intraoperative FIO2 was dose-dependently associated with major pulmonary complications and mortality after adjustment for all relevant risk factors. This association has not yet been confirmed in RCTs [152].

Based on a sub-group analysis in a systematic review, the World Health Organization proposed using FIO2 = 0.80 in all intubated patients to prevent postoperative wound infections [153]. This engendered controversial discussion [154, 155]. Most of the evidence for risks and benefits of hyperoxia during emergency surgery arise from RCTs of 385 laparotomy procedures and 210 open appendicectomies [143, 156]. While wound infections were significantly reduced with FIO2 = 0.80 in the appendicectomy study, the frequencies of surgical site infections, serious adverse events and mortality did not differ in the laparotomy trial [156, 157].

Acute perioperative patients should be carefully treated with respect to their ongoing medical conditions; most current evidence suggests greatest safety with O2 titration to normoxaemia.

Conclusions

Current evidence suggests that PaO2 > 300mmmHg should be avoided in most ICU patients. It remains uncertain whether there is a “sweet spot” PaO2 target, which may vary for given clinical conditions. Systematic reviews using trial sequential analysis to take into account high vs. low bias risk found no effect (including all patients [39]) or increased mortality (including only ICU patients [157]) from higher oxygenation targets. Certainty evidence was low with futility for a 15% relative mortality risk increase. The currently recruiting “Mega-Randomised-Registry-Trial-Comparing-Conservative-vs.-Liberal-Oxygenation (Mega-ROX trial)” (CTG1920-01) in 40,000 patients should provide any “ideal target PaO2”: The trial tests the hypothesis that conservative vs. liberal O2 targets reduce mortality by 1.5% points in mechanically ventilated, adult ICU patients, i.e. 1,500 lives saved for every 100,000 patients treated. Since both conservative and liberal O2 therapy may be best for certain patients, several parallel trials will evaluate pre-specified hypotheses in specific patient cohort patients accompanied by separate power calculations. For example, anticipating heterogeneity of treatment response, in septic patients or patients with acute brain pathologies (other than hypoxic brain injuries), the trial will test the opposite hypothesis that liberal (rather than conservative) O2 will reduce mortality. Finally, the trial design cannot exclude that for some patient sub-groups, a different window of O2 exposure is most suited.

So far, it appears prudent to target PaO2 values within the normal range, i.e. carefully titrating PaO2 to avoid both hypoxaemia and excess hyperoxaemia [158], particular as no clinically useful biomarker of O2 toxicity is available, and data on the effects of hyperoxia on markers of oxidative stress are equivocal [10, 159–161].

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Main features of the studies discussed in the text. ABG arterial blood gas; ACS acute coronary syndrome; AIS acute ischaemic stroke; AMI acute myocardial infarction; CI confidence interval; CPR cardiopulmonary resuscitation; d day; ED emergency department; GCS Glasgow coma score; GOS Glasgow outcome scale; GOSE Glasgow outcome scale extended; ICU intensive care unit; IQR interquartile range; ICB intracranial bleeding; mo month; MV mechanical ventilation; OR odds ratio; PPI proton pump inhibitor; RBC red blood cell; RCT randomised controlled trial; ROSC return of spontaneous circulation; SAB subarachnoidal bleeding; SIRS systemic inflammatory response syndrome; SpO2 pulse oximetry haemoglobin O2 saturation; SOFA sequential organ failure assessment; SSI surgical site infection; STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction; TBI traumatic brain injury; TWA time-weighted average; VAP ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Authors' contributions

M. Singer contributed to subchapter on pathophysiology; PJY contributed to subchapter on general ICU population; JGL contributed to subchapter on ARDS; PA contributed to subchapter on sepsis and septic shock; FST contributed to subchapter on acute brain injury; PR contributed to subchapter on trauma-and-haemorrhage; M. Skrifvars contributed to subchapter on CPR and MI; CSM contributed to subchapter on perioperative hyperoxia. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. PR was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG, German Research Foundation), Project-ID 251293561, CRC 1149. This research was conducted during the tenure of a Health Research Council of New Zealand Clinical Practitioner Research Fellowship held by PY. The Medical Research Institute of New Zealand is supported by independent research organisation funding from the Health Research Council of New Zealand.

Availability of data materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests..

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References:

- 1.West JB. Carl Wilhelm Scheele, the discoverer of oxygen, and a very productive chemist. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;307(11):L811–L816. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00223.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West JB. Joseph Priestley, oxygen, and the enlightenment. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2014;306(2):L111–L119. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00310.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.West JB. The collaboration of Antoine and Marie-Anne Lavoisier and the first measurements of human oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2013;305(11):L775–L785. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00228.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leverve XM. To cope with oxygen: a long and still tumultuous story for life. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(2):637–638. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E31816296AD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asfar P, Singer M, Radermacher P. Understanding the benefits and harms of oxygen therapy. Intensive Care Med. 2015;41(6):1118–1121. doi: 10.1007/s00134-015-3670-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hafner S, Beloncle F, Koch A, Radermacher P, Asfar P. Hyperoxia in intensive care, emergency, and peri-operative medicine: Dr. Jekyll or Mr. Hyde? A 2015 update. Ann Intensive Care. 2015;5(1):42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Demiselle J, Calzia E, Hartmann C, Messerer DAC, Asfar P, Radermacher P, Datzmann T. Target arterial PO2 according to the underlying pathology: a mini-review of the available clinical data. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11(1):88. doi: 10.1186/s13613-021-00872-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turrens J. Mitochondrial formation of reactive oxygen species. J Physiol. 2003;552(Pt 2):335–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.049478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jamieson D, Chance B, Cadenas E, Boveris A. The relation of free radical production to hyperoxia. Annu Rev Physiol. 1986;48:703–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.48.030186.003415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khaw KS, Wang CC, Ngan Kee WD, Pang CP, Rogers MS. Effects of high inspired oxygen fraction during elective caesarean section under spinal anaesthesia on maternal and fetal oxygenation and lipid peroxidation. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88(1):18–23. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafner C, Pramhas S, Schaubmayr W, Assinger A, Gleiss A, Tretter EV, Klein KU, Schrabert G. Brief high oxygen concentration induces oxidative stress in leukocytes and platelets – a randomised cross-over pilot study in healthy male volunteers. Shock. 2021 doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000001728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Magder S. Reactive oxygen species: toxic molecules or spark of life? Crit Care. 2006;10(1):208. doi: 10.1186/cc3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Warren CPW. The introduction of oxygen for pneumonia as seen through the writings of two McGill University professors, William Osler and Jonathan Meakins. Can Respir J. 2005;12(2):81–85. doi: 10.1155/2005/146951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clark JM, Lambertsen CJ. Pulmonary oxygen toxicity: a review. Pharmacol Rev. 1971;23(2):37–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hochberg CH, Semler MW, Brower RG. Oxygen toxicity in critically ill adults. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021;204(6):632–641. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202102-0417CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rhee SG. Cell signalling. H2O2, a necessary evil for cell signaling. Science. 312(5782):1882–3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Sjöberg F, Singer M. The medical use of oxygen: a time for critical reappraisal. J Intern Med. 274(6):505–28. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Smith JL. The pathological effects due to increase of oxygen tension in the air breathed. J Physiol. 1899;24(1):19–35. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1899.sp000746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jackson RM. Pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Chest. 1985;88(6):900–905. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.6.900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robinson FR, Casey HW. Weibel .Animal model: Oxygen toxicity in nonhuman primates. Am J Pathol. 1974;76(1):175–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fracica PJ, Knapp MJ, Piantadosi CA, Takeda K, Fulkerson WJ, Coleman RE, Wolfe WG, Crapo JD. Responses of baboons to prolonged hyperoxia: physiology and qualitative pathology. J Appl Physiol. 1991;71(6):2352–2362. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1991.71.6.2352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Crapo JD, Hayatdavoudi G, Knapp MJ, Fracica PJ, Wolfe WG, Piantadosi CA. Progressive alveolar septal injury in primates exposed to 60% oxygen for 14 days. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(6 Pt 1):L797–806. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.267.6.L797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calzia E, Asfar P, Hauser B, Matejovic M, Ballestra C, Radermacher P, Georgieff M. Hyperoxia may be beneficial. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(10 Suppl):S559–S568. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f1fe70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dantzker DR, Wagner PD, West JB. Instability of lung units with low V̇A/Q ratio during O2 breathing. J Appl Physiol. 1975;38(5):886–895. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demchenko IT, Welty-Wolf KE, Allen BW, Piantadosi CA. Similar but not the same: normobaric and hyperbaric pulmonary oxygen toxicity, the role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;293(1):L229–L238. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00450.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tryka AF, Godleski JJ, Brain JD. Differences in effects of immediate and delayed hyperoxia exposure on bleomycin-induced pulmonic injury. Cancer Treat Rep. 1984;68(5):759–764. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bert PL. Pression Barométrique: Recherches de Physiologie Expérimentale. Paris: G. Masson; 1878. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Behnke AR, Johnson FS, Poppen JR, Motley EP. The effect of oxygen on man at pressures from 1 to 4 atmospheres. Am J Physiol. 1934;110:565–572. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellman PI, Alvis JS, Tache-Leon C, Singh R, Reece TB, Kern JA, Tribble CG, Kron IL. Hyperoxic ventilation exacerbates lung reperfusion injury. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;130:1440. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mariero LH, Rutkovskiy A, Stensløkken KO, Vaage J. Hyperoxia during early reperfusion does not increase ischemia/reperfusion injury. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2011.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wolbarsht ML, Fridovich I. Hyperoxia during reperfusion is a factor in reperfusion injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 1989;6:61–62. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(89)90161-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsai A, Cabrales P, Winslow R, Intaglietta M. Microvascular oxygen distribution in the awake hamster window chamber model during hyperoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;285:H1537–H1545. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00176.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stamler JS, Jia L, Eu JP, McMahon TJ, Demchenko IT, Bonaventura J, Gernert K, Piantadosi CA. Blood flow regulation by S-nitrosohemoglobin in the physiological oxygen gradient. Science. 1997;276(5321):2034–2037. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganz W, Donoso R, Marcus H, Swan HJ. Coronary hemodynamics and myocardial oxygen metabolism during oxygen breathing in patients with and without coronary artery disease. Circulation. 1972;45:763–768. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.4.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McNulty PH, Robertson BJ, Tulli MA, Hess J, Harach LA, Scott S, Sinoway LI. Effect of hyperoxia and vitamin C on coronary blood flow in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(5):2040–2045. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00595.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Girardis M, Busani S, Damiani E, Donati A, Rinaldi L, Marudi A, Morelli A, Antonelli M, Singer M. Effect of conservative vs conventional oxygen therapy on mortality among patients in an intensive care unit: the Oxygen-ICU randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;316(15):1583–1589. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.11993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ridgeon E, Bellomo R, Myburgh J, Saxena M, Weatherall M, Jahan R, Arawwawala D, Bell S, Butt W, Camsooksai J, Carle C, Cheng A, Cirstea E, Cohen J, Cranshaw J, Delaney A, Eastwood G, Eliott S, Franke U, Gantner D, Green C, Howard-Griffin R, Inskip D, Litton E, MacIsaac C, McCairn A, Mahambrey T, Moondi P, Newby L, O'Connor S, Pegg C, Pope A, Reschreiter H, Richards B, Robertson M, Rodgers H, Shehabi Y, Smith I, Smith J, Smith N, Tilsley A, Whitehead C, Willett E, Wong K, Woodford C, Wright S, Young P. Validation of a classification system for causes of death in critical care: an assessment of inter-rater reliability. Crit Care Resusc. 2016;8(1):50–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chu DK, Kim LH, Young PJ, Zamiri N, Almenawer SA, Jaeschke R, Szczeklik W, Schunemann HJ, Neary JD, Alhazzani W. Mortality and morbidity in acutely ill adults treated with liberal versus conservative oxygen therapy (IOTA): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1693–1705. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30479-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barbateskovic M, Schjørring OL, Krauss SR, Meyhoff CS, Jakobsen JC, B Rasmussen BS, Perner A, Jørn Wetterslev J. Higher vs lower oxygenation strategies in acutely ill adults: a systematic review with meta-analysis and trial sequential analysis. Chest. 2021;159(1):154–73. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.ICU-ROX Investigators and the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group, Mackle D, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Beasley R, Deane A, Eastwood G, Finfer S, Freebairn R, King V, Linke N, Litton E, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Panwar R, Young P; ICU-ROX investigators the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Conservative oxygen therapy during mechanical ventilation in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2020 Mar 12;382(11):989–98. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Young PJ, Bagshaw SM, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Mackle D, Pilcher D, Landoni G, Nichol A, Martin D. O2, do we know what to do? Crit Care Resusc. 2019;21(4):230–232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Young PJ, Bellomo R. The risk of hyperoxemia in ICU patients: much ado about O2. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(11):1333–1335. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201909-1751ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gelissen H, de Grooth HJ, Smulders Y, Wils EJ, de Ruijter W, Vink R, Smit B, Röttgering J, Atmowihardjo L, Girbes A, Elbers P, Tuinman PR, Oudemans-van Straaten H, de Man A. Effect of low-normal vs high-normal oxygenation targets on organ dysfunction in critically ill patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;326(10):940–948. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.MacIntyre NR. Tissue hypoxia: implications for the respiratory clinician. Respir Care. 2014;59(10):1590–1596. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brueckl C, Kaestle S, Kerem A, Habazettl H, Krombach F, Kuppe H, Kuebler WM. Hyperoxia-induced reactive oxygen species formation in pulmonary capillary endothelial cells in situ. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006;34(4):453–463. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0223OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mantell LL, Lee PJ. Signal transduction pathways in hyperoxia-induced lung cell death. Mol Genet Metab. 2000;71(1–2):359–370. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2000.3046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bak Z, Sjöberg F, Rousseau A, Steinvall I, Janerot-Sjoberg B. Human cardiovascular dose-response to supplemental oxygen. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2007;191(1):15–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2007.01710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mak S, Egri Z, Tanna G, Coleman R, Newton GE. Vitamin C prevents hyperoxia-mediated vasoconstriction and impairment of endothelium dependent vasodilation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2002;282:H2414–H2421. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00947.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reinhart K, Spies CD, Meier-Hellmann A, Bredle DL, Hannemann L, Specht M, Schaffartzik W. N-acetylcysteine preserves oxygen consumption and gastric mucosal pH during hyperoxic ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151(3 Pt 1):773–779. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis WB, Rennard SI, Bitterman PB, Crystal RG. Pulmonary oxygen toxicity. Early reversible changes in human alveolar structures induced by hyperoxia. N Engl J Med. 1983;309(15):878–83. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Kapanci Y, Tosco R, Eggermann J, Gould VE. Oxygen pneumonitis in man. Light- and electron-microscopic morphometric studies Chest. 1972;62(2):162–169. doi: 10.1378/chest.62.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Itagaki T, Nakano Y, Okuda N, Izawa M, Onodera M, Imanaka H, Nishimura M. Hyperoxemia in mechanically ventilated, critically ill subjects: incidence and related factors. Respir Care. 2015;60(3):335–340. doi: 10.4187/respcare.03451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Graaff AE, Dongelmans DA, Binnekade JM, de Jonge E. Clinicians' response to hyperoxia in ventilated patients in a Dutch ICU depends on the level of FiO2. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37(1):46–51. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-2025-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Helmerhorst HJF, Arts DL, Schultz MJ, van der Voort PHJ, Abu-Hanna A, de Jonge E, van Westerloo DJ. Metrics of arterial hyperoxia and associated outcomes in critical care. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(2):187–195. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Network TARDS. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(18):1301–1308. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Driscoll BR, Howard LS, Earis J, Mak V, British Thoracic Society Emergency Oxygen Guideline G, Group BTSEOGD. BTS guideline for oxygen use in adults in healthcare and emergency settings. Thorax. 2017;72(Suppl 1):ii1-ii90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Aggarwal NR, Brower RG, Hager DN, Thompson BT, Netzer G, Shanholtz C, Lagakos A, Checkley W, National Institutes of Health Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Network Investigators. Oxygen exposure resulting in arterial oxygen tensions above the protocol goal was associated with worse clinical outcomes in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2018;46(4):517–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 58.Yamada M, Kubo H, Kobayashi S, Ishizawa K, Sasaki H. Interferon-γ: a key contributor to hyperoxia-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2004;287(5):L1042–L1047. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00155.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aggarwal NR, D'Alessio FR, Tsushima K, Files DC, Damarla M, Sidhaye VK, Fraig MM, Polotsky VY, King LS. Moderate oxygen augments lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298(3):L371–L381. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00308.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baleeiro CE, Wilcoxen SE, Morris SB, Standiford TJ, Paine R. Sublethal hyperoxia impairs pulmonary innate immunity. J Immunol. 2003;171(2):955–963. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helmerhorst HJF, Schouten LRA, Wagenaar GTM, Juffermans NP, Roelofs J, Schultz MJ, de Jonge E, van Westerloo D. Hyperoxia provokes a time- and dose-dependent inflammatory response in mechanically ventilated mice, irrespective of tidal volumes. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0142-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li LF, Liao SK, Ko YS, Lee CH, Quinn DA. Hyperoxia increases ventilator-induced lung injury via mitogen-activated protein kinases: a prospective, controlled animal experiment. Crit Care. 2007;11(1):R25. doi: 10.1186/cc5704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Barrot L, Asfar P, Mauny F, Winiszewski H, Montini F, Badie J, Quenot JP, Pili-Floury S, Bouhemad B, Louis G, Souweine B, Collange O, Pottecher J, Levy B, Puyraveau M, Vettoretti L, Constantin JM, Capellier G, LOCO2 Investigators and REVA Research Network. Liberal or conservative oxygen therapy for Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(11):999–1008. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Schjørring OL, Klitgaard TL, Perner A, Wetterslev J, Lange T, Siegemund M, Bäcklund M, Keus F, Laake JH, Morgan M, Thormar KM, Rosborg SA, Bisgaard J, Erntgaard AES, Lynnerup AH, Pedersen RL, Crescioli E, Gielstrup TC, Behzadi MT, Poulsen LM, Estrup S, Laigaard JP, Andersen C, Mortensen CB, Brand BA, White J, Jarnvig IL, Møller MH, Quist L, Bestle MH, Schønemann-Lund M, Kamper MK, Hindborg M, Hollinger A, Gebhard CE, Zellweger N, Meyhoff CS, Hjort M, Bech LK, Grøfte T, Bundgaard H, Østergaard LHM, Thyø MA, Hildebrandt T, Uslu B, Sølling CG, Møller-Nielsen N, Brøchner AC, Borup M, Okkonen M, Dieperink W, Pedersen UG, Andreasen AS, Buus L, Aslam TN, Winding RR, Schefold JC, Thorup SB, Iversen SA, Engstrøm J, Kjær MN, Rasmussen BS; HOT-ICU Investigators.. Lower or higher oxygenation targets for acute hypoxemic respiratory failure. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(14):1301–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Madotto F, Rezoagli E, Pham T, Schmidt M, McNicholas B, Protti A, Panwar R, Bellani G, Fan E, van Haren F, Brochard L, Laffey JG; LUNG SAFE Investigators and the ESICM Trials Group. Hyperoxemia and excess oxygen use in early acute respiratory distress syndrome: insights from the LUNG SAFE study. Crit Care. 2020 Mar 31;24(1):125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.de Jonge E, Peelen L, Keijzers PJ, Joore H, de Lange D, van der Voort PH, Bosman RJ, de Waal RA, Wesselink R, de Keizer NF. Association between administered oxygen, arterial partial oxygen pressure and mortality in mechanically ventilated intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2008;12(6):R156. doi: 10.1186/cc7150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Palmer E, Post B, Klapaukh R, Marra G, MacCallum NS, Brealey D, Ercole A, Jones A, Ashworth S, Watkinson P, Beale R, Brett SJ, Young JD, Black C, Rashan A, Martin D, Singer M, Harris S. The association between supraphysiologic arterial oxygen levels and mortality in critically ill patients. A multicenter observational cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(11):1373–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Shapiro NI, Angelos MG, Milcarek B, Hunter K, Parrillo JE, Trzeciak S; Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators. Association between arterial hyperoxia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest and in-hospital mortality. JAMA. 2010;303(21):2165–71. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 69.Boyle AJ, Holmes DN, Hackett J, Gilliland S, McCloskey M, O'Kane CM, Young P, Di Gangi S, McAuley DF. Hyperoxaemia and hypoxaemia are associated with harm in patients with ARDS. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21(1):285. doi: 10.1186/s12890-021-01648-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Knighton DR, Halliday B, Hunt TK. Oxygen as an antibiotic. The effect of inspired oxygen on infection. Arch Surg. 1984;119(2):199–204. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Knighton DR, Fiegel VD, Halverson T, Schneider S, Brown T, Wells CL. Oxygen as an antibiotic. The effect of inspired oxygen on bacterial clearance. Arch Surg. 1990;125(1):97–100. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Smit B, Smulders YM, van der Wouden JC, Oudemans-van Straaten HM, Spoelstra-de Man AME. Hemodynamic effects of acute hyperoxia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-1968-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Six S, Jaffal K, Ledoux G, Jaillette E, Wallet F, Nseir S. Hyperoxemia as a risk factor for ventilator-associated pneumonia. Crit Care. 2016;20(1):195. doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1368-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Six S, Rouzé A, Pouly O, Poissy J, Wallet F, Preau S, Nseir S. Impact of hyperoxemia on mortality in critically ill patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6(21):417. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.10.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Asfar P, Schortgen F, Boisramé-Helms J, Charpentier J, Guérot E, Megarbane B, Grimaldi D, Grelon F, Anguel N, Lasocki S, Henry-Lagarrigue M, Gonzalez F, Legay F, Guitton C, Schenck M, Doise JM, Devaquet J, Van Der Linden T, Chatellier D, Rigaud JP, Dellamonica J, Tamion F, Meziani F, Mercat A, Dreyfuss D, Seegers V, Radermacher P; HYPER2S Investigators; REVA research network. Hyperoxia and hypertonic saline in patients with septic shock (HYPERS2S): a two-by-two factorial, multicentre, randomised, clinical trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5(3):180–190. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Demiselle J, Wepler M, Hartmann C, Radermacher P, Schortgen F, Meziani F, Singer M, Seegers V, Asfar P; HYPER2S investigators. Hyperoxia toxicity in septic shock patients according to the Sepsis-3 criteria: a post hoc analysis of the HYPER2S trial. Ann Intensive Care. 2018;8(1):90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 77.Young P, Mackle D, Bellomo R, Bailey M, Beasley R, Deane A, Eastwood G, Finfer S, Freebairn R, King V, Linke N, Litton E, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Panwar R, ICU-ROX Investigators the Australian New Zealand Intensive Care Society Clinical Trials Group. Conservative oxygen therapy for mechanically ventilated adults with sepsis: a post hoc analysis of data from the intensive care unit randomized trial comparing two approaches to oxygen therapy (ICU-ROX). Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(1):17–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 78.Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(18):1726–1734. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1208943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Myers RB, Lazaridis C, Jermaine CM, Robertson CS, Rusin CG. Predicting intracranial pressure and brain tissue oxygen crises in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(9):1754–1761. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pascual JL, Georgoff P, Maloney-Wilensky E, Sims C, Sarani B, Stiefel MF, LeRoux PD, Schwab CW. Reduced brain tissue oxygen in traumatic brain injury: are most commonly used interventions successful? J Trauma. 2011;70(3):535–546. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31820b59de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Okonkwo DO, Shutter LA, Moore C, Temkin NR, Puccio AM, Madden CJ, Andaluz N, Chesnut RM, Bullock MR, Grant GA, McGregor J, Weaver M, Jallo J, LeRoux PD, Moberg D, Barber J, Lazaridis C, Diaz-Arrastia RR. Brain oxygen optimization in severe traumatic brain injury phase-II: a phase II randomized trial. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(11):1907–1914. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Hlatky R, Valadka AB, Gopinath SP, Robertson CS. Brain tissue oxygen tension response to induced hyperoxia reduced in hypoperfused brain. J Neurosurg. 2008;108(1):53–58. doi: 10.3171/JNS/2008/108/01/0053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Veenith TV, Carter EL, Grossac J, Newcombe VF, Outtrim JG, Nallapareddy S, Lupson V, Correia MM, Mada MM, Williams GB, Menon DK, Coles JP. Use of diffusion tensor imaging to assess the impact of normobaric hyperoxia within at-risk pericontusional tissue after traumatic brain injury. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2014;34(10):1622–1627. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Quintard H, Patet C, Suys T, Marques-Vidal P, Oddo M. Normobaric hyperoxia is associated with increased cerebral excitotoxicity after severe traumatic brain injury. Neurocrit Care. 2015;22(2):243–250. doi: 10.1007/s12028-014-0062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Davis DP, Meade W, Sise MJ, Kennedy F, Simon F, Tominaga G, Steele J, Coimbra R. Both hypoxemia and extreme hyperoxemia may be detrimental in patients with severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma. 2009;26(12):2217–2223. doi: 10.1089/neu.2009.0940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Raj R, Bendel S, Reinikainen M, Kivisaari R, Siironen J, Lång M, Skrifvars M. Hyperoxemia and long-term outcome after traumatic brain injury. Crit Care. 2013;17(4):R177. doi: 10.1186/cc12856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Rincon F, Kang J, Maltenfort M, Vibbert M, Urtecho J, Athar MK, Jallo J, Pineda CC, Tzeng D, McBride W, Bell R. Association between hyperoxia and mortality after stroke: a multicenter cohort study. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(2):387–396. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182a27732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.López HV, Vivas MF, Ruiz RN, Martínez JR, Navaridas BG, Villa MG, Lázaro CL, Rubio RJ, Ortiz AM, Lacal LA, Diéguez AM. Association between post-procedural hyperoxia and poor functional outcome after mechanical thrombectomy for ischemic stroke: an observational study. Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):59. doi: 10.1186/s13613-019-0533-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Fukuda S, Koga Y, Fujita M, Suehiro E, Kaneda K, Oda Y, Ishihara H, Suzuki M, Tsuruta R. Hyperoxemia during the hyperacute phase of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage is associated with delayed cerebral ischemia and poor outcome: a retrospective observational study. J Neurosurg. 2021;134(1):25–32. doi: 10.3171/2019.9.JNS19781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Reynolds RA, Amin SN, Jonathan SV, Tang AR, Lan M, Wang C, Bastarache JA, Ware LB, Thompson RC. Hyperoxemia and cerebral vasospasm in aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2021;35(1):30–38. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01136-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lång M, Raj R, Skrifvars MB, Koivisto T, Lehto H, Kivisaari R, von Und Zu Fraunberg M, Reinikainen M, Bendel S. Early Moderate Hyperoxemia Does Not Predict Outcome After Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2016;78(4):540–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 92.Roffe C, Nevatte T, Sim J, Bishop J, Ives N, Ferdinand P, Gray R; Stroke Oxygen Study Investigators and the Stroke Oxygen Study Collaborative Group. Effect of routine low-dose oxygen supplementation on death and disability in adults with acute stroke: the stroke oxygen study randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2017;318(12):1125–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Young P, Beasley R, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Eastwood GM, Nichol A, Pilcher DV, Yunos NM, Egi M, Hart GK, Reade MC, Cooper DJ; Study of Oxygen in Critical Care (SOCC) Group. The association between early arterial oxygenation and mortality in ventilated patients with acute ischaemic stroke. Crit Care Resusc. 2012;14(1):14–9. [PubMed]

- 94.O’Briain D, Nickson C, Pilcher DV, Udy AA. Early hyperoxia in patients with traumatic brain injury admitted to intensive care in Australia and New Zealand: a retrospective multicenter cohort study. Neurocrit Care. 2018;29(3):443–451. doi: 10.1007/s12028-018-0553-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Weeden M, Bailey M, Gabbe B, Pilcher D, Bellomo R, Udy A. Functional outcomes in patients admitted to the intensive care unit with traumatic brain injury and exposed to hyperoxia: a retrospective multicentre cohort study. Neurocrit Care. 2021;34(2):441–448. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01033-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Alali AS, Temkin N, Vavilala MS, Lele AV, Barber J, Dikmen S, Chesnut RM. Matching early arterial oxygenation to long-term outcome in severe traumatic brain injury: target values. J Neurosurg. 2019;132(2):537–544. doi: 10.3171/2018.10.JNS18964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Li N, Wu L, Zhao W, Dornbos D, Wu C, Li W, Wu D, Ding J, Ding Y, Xie Y, Ji X. Efficacy and safety of normobaric hyperoxia combined with intravenous thrombolysis on acute ischemic stroke patients. Neurol Res. 2021;15:1–6. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2021.1939234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Singhal AB, Benner T, Roccatagliata L, Koroshetz WJ, Schaefer PW, Lo EH, Buonanno FS, Gonzalez RG, Sorensen AG. A pilot study of normobaric oxygen therapy in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2005;36(4):797–802. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158914.66827.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wu O, Benner T, Roccatagliata L, Zhu M, Schaefer PW, Sorensen AG, Singhal AB. Evaluating effects of normobaric oxygen therapy in acute stroke with MRI-based predictive models. Med Gas Res. 2012;2(1):5. doi: 10.1186/2045-9912-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Padma MV, Bhasin A, Bhatia R, Garg A, Singh MB, Tripathi M, Prasad K. Normobaric oxygen therapy in acute ischemic stroke: A pilot study in Indian patients. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2010;13(4):284–288. doi: 10.4103/0972-2327.74203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Taher A, Pilehvari Z, Poorolajal J, Aghajanloo M. Effects of normobaric hyperoxia in traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Trauma Mon. 2016;21(1):e26772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 102.Lång M, Skrifvars MB, Siironen J, Tanskanen P, Ala-Peijari M, Koivisto T, Djafarzadeh S, S Bendel S. A pilot study of hyperoxemia on neurological injury, inflammation and oxidative stress. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2018;62(6):801–10. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Barbee RW, Reynolds PS, Ward KR. Assessing shock resuscitation strategies by oxygen debt repayment. Shock. 2010;33(2):113–122. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181b8569d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Dyson A, Simon F, Seifritz A, Zimmerling O, Matallo J, Calzia E, Radermacher P, Singer M. Bladder tissue oxygen tension monitoring in pigs subjected to a range of cardiorespiratory and pharmacological challenges. Intensive Care Med. 2012;38(11):1868–1876. doi: 10.1007/s00134-012-2712-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Knöller E, Stenzel T, Broeskamp F, Hornung R, Scheuerle A, McCook O, Wachter U, Vogt JA, Matallo J, Wepler M, Gässler H, Gröger M, Matejovic M, Calzia E, Lampl L, Georgieff M, Möller P, Asfar P, Radermacher P, Hafner S. Effects of hyperoxia and mild therapeutic hypothermia during resuscitation from porcine hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:e264–e277. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000001412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Hartmann C, Loconte M, Antonucci E, Holzhauser M, Hölle T, Katzsch D, Merz T, McCook O, Wachter U, Vogt JA, Hoffmann A, Wepler M, Gröger M, Matejovic M, Calzia E, Georgieff M, Asfar P, Radermacher P, Nussbaum BL. Effects of hyperoxia during resuscitation from hemorrhagic shock in swine with preexisting coronary artery disease. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(12):e1270–e1279. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000002767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Leitch P, Hudson AL, Griggs JE, Stolmeijer R, Lyon RM, Ter Avest E; Air Ambulance Kent Surrey Sussex. Incidence of hyperoxia in trauma patients receiving pre-hospital emergency anaesthesia: results of a 5-year retrospective analysis. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2021;29(1):134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Russell DW, Janz DR, Emerson WL, May AK, Bernard GR, Zhao Z, Koyama T, Ware LB. Early exposure to hyperoxia and mortality in critically ill patients with severe traumatic injuries. BMC Pulm Med. 2017;17(1):29. doi: 10.1186/s12890-017-0370-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Page D, Ablordeppey E, Wessman BT, Mohr NM, Trzeciak S, Kollef MH, Roberts BW, Fuller BM. Emergency department hyperoxia is associated with increased mortality in mechanically ventilated patients: a cohort study. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1926-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Baekgaard J, Abback PS, Boubaya M, Moyer JD, Garrigue D, Raux M, Champigneulle B, Dubreuil G, Pottecher J, Laitselart P, Laloum F, Bloch-Queyrat C, Adnet F, Paugam-Burtz C; Traumabase® Study Group. Early hyperoxemia is associated with lower adjusted mortality after severe trauma: Results from a French registry. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 111.Duclos G, Rivory A, Rességuier N, Hammad E, Vigne C, Meresse Z, Pastène B, Xavier- D'journo XB, Jaber S, Zieleskiewicz L, Leone M. Effect of early hyperoxemia on the outcome in servere blunt chest trauma: A propensity score-based analysis of a single-center retrospective cohort. J Crit Care. 2021;63:179–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Christensen MA, Steinmetz J, Velmahos G, Rasmussen LS. Supplemental oxygen therapy in trauma patients: An exploratory registry-based study. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2021 doi: 10.1111/aas.13829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Yamamoto R, Fujishima S, Sasaki J, Gando S, Saitoh D, Shiraishi A, Kushimoto S, Ogura H, Abe T, Mayumi T, Kotani J, Nakada TA, Shiino Y, Tarui T, Okamoto K, Sakamoto Y, Shiraishi SI, Takuma K, Tsuruta R, Masuno T, Takeyama N, Yamashita N, Ikeda H, Ueyama M, Hifumi T, Yamakawa K, Hagiwara A, Otomo Y; Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) Focused Outcomes Research in Emergency Care in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Sepsis and Trauma (FORECAST) Study Group. Hyperoxemia during resuscitation of trauma patients and increased intensive care unit length of stay: inverse probability of treatment weighting analysis. World J Emerg Surg. 2021;16(1):19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 114.Douin DJ, Anderson EL, Dylla L, Rice JD, Jackson CL, Wright FL, Bebarta VS, Schauer SG, Ginde AA. Association between hyperoxia, supplemental oxygen, and mortality in critically injured patients. Crit Care Explor. 2021;3(5):e0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 115.Imberti R, Bellinzona G, Riccardi F, Pagani M, Langer M. Cerebral perfusion pressure and cerebral tissue oxygen tension in a patient during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Intensive Care Med Intensive Care Med. 2003;29(6):1016–1019. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1719-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Nelskylä A, Nurmi J, Jousi M, Schramko A, Mervaala E, Ristagno G, Skrifvars MB. The effect of 50% compared to 100% inspired oxygen fraction on brain oxygenation and post cardiac arrest mitochondrial function in experimental cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2017;116:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2017.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Soar J, Nolan JP, Böttiger BW, Perkins GD, Lott C, Carli P, Pellis T, Sandroni C, Skrifvars MB, Smith GB, Sunde K, Deakin CD, Adult advanced life support section Collaborators. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation, Section 3. Adult advanced life support Resuscitation. 2015;2015(95):100–147. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Spindelboeck W, Gemes G, Strasser C, Toescher K, Kores B, Metnitz P, Haas J, Prause G. Arterial blood gases during and their dynamic changes after cardiopulmonary resuscitation: A prospective clinical study. Resuscitation. 2016;106:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2016.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Spindelboeck W, Schindler O, Moser A, Hausler F, Wallner S, Strasser C, Haas J, Gemes G, Prause G. Increasing arterial oxygen partial pressure during cardiopulmonary resuscitation is associated with improved rates of hospital admission. Resuscitation. 2013;84:770–775. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Young P, Bailey M, Bellomo R, Bernard S, Dicker B, Freebairn R, Henderson S, Mackle D, McArthur C, McGuinness S, Smith T, Swain A, Weatherall M, Beasley R. HyperOxic Therapy OR NormOxic Therapy after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (HOT OR NOT): a randomised controlled feasibility trial. Resuscitation. 2014;85:1686–1691. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Kilgannon JH, Jones AE, Parrillo JE, Dellinger RP, Milcarek B, Hunter K, Shapiro NI, Trzeciak S, Emergency Medicine Shock Research Network (EMShockNet) Investigators. Relationship between supranormal oxygen tension and outcome after resuscitation from cardiac arrest. Circulation. 2011;123(23):2717–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 122.Janz DR, Hollenbeck RD, Pollock JS, McPherson JA, Rice TW. Hyperoxia is associated with increased mortality in patients treated with mild therapeutic hypothermia after sudden cardiac arrest. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(12):3135–3139. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182656976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wang CH, Huang CH, Chang WT, Tsai MS, Lu TC, Yu PH, Wang AY, Chen NC, Chen WJ. Association between early arterial blood gas tensions and neurological outcome in adult patients following in-hospital cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2015;89:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]