Abstract

Cholecystokinin (CCK), the most abundant brain neuropeptide, is involved in relevant behavioral functions like memory, cognition, and reward through its interactions with the opioid and dopaminergic systems in the limbic system. CCK excites neurons by binding two receptors, CCK1 and CCK2, expressed at low and high levels in the brain, respectively. Historically, CCK2 receptors have been related to the induction of panic attacks in humans. Disturbances in brain CCK expression also underlie the physiopathology of schizophrenia, which is attributed to the modulation by CCK1 receptors of the dopamine flux in the basal striatum. Despite this evidence, neither CCK2 receptor antagonists ameliorate human anxiety nor CCK agonists have consistently shown neuroleptic effects in clinical trials. A neglected aspect of the function of brain CCK is its neuromodulatory role in mental disorders. Interestingly, CCK is expressed in pivotal inhibitory interneurons that sculpt cortical dynamics and the flux of nerve impulses across corticolimbic areas and the excitatory projections to mesolimbic pathways. At the basal striatum, CCK modulates the excitability of glutamate, the release of inhibitory GABA, and the discharge of dopamine. Here we focus on how CCK may reduce rather than trigger anxiety by regulating its cognitive component. Adequate levels of CCK release in the basal striatum may control the interplay between cognition and reward circuitry, which is critical in schizophrenia. Hence, it is proposed that disturbances in the excitatory/inhibitory interplay modulated by CCK may contribute to the imbalanced interaction between corticolimbic and mesolimbic neural activity found in anxiety and schizophrenia.

Keywords: Anxiety, cholecystokinin, dopamine, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamic acid, schizophrenia

1. INTRODUCTION

Cholecystokinin (CCK) is a member of a sulfated peptide family originally thought to be confined to the gastrointestinal tract but whose small form CCK8 is the most widely distributed neurotransmitter in the mammal brain [1]. It binds two receptor subtypes, namely CCK1 and CCK2, expressed at relatively low and high levels in the brain [2]. Relevant behavioral functions attributed to CCK are memory and cognition [3-6], reward-related behaviors [7-9], and more importantly, anxiety [10-16]. Yet systemic administration of selective CCK2 agonists like CCK4 and pentagastrin triggers panic in humans [10,17,18], CCK2 antagonists have never been proven to ameliorate human anxiety [19-21].

Despite the failed clinical trials, CCK continues to be a valid therapeutic target in psychiatry [22] due to its intermingled functional interplays with dopamine (DA) [23, 24], opioids [5], γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) [25], and glutamate [6]. Accordingly, it has been proposed to have a neuromodulatory function in a range of abnormal behaviors, from social isolation-induced aggression in Drosophila [26] to human anxiety [9] and schizophrenia [27]. Also, as a result of its neuromodulatory role, significant inter-individual differences have been found in response to the panicogenic CCK4 challenge [28-33]. In schizophrenics, rapidity of antipsychotic response to haloperidol and the Scale for the Assessment of the Negative Symptom was found negatively correlated with the levels of CCK in cerebrospinal fluid [34] and peripheral blood mononuclear cells [35], respectively. The role of CCK in mental health could be indirect.

The neurobiology of anxiety and shizophrenia is interwoven in some points [36]. CCK is interspersed in the excitatory-inhibitory neurons of corticolimbic areas [37] and mesolimbic pathways [38, 39] that malfunction in both panic disorder [40, 41] and schizophrenia [42-47]. CCK has co-evolved with GABA and glutamate [48] to colocalize in the interneurons that sculpt cortical dynamics [49]. CCK is likely to corelease with glutamate within the corticofugal projections to the basal striatum [50]. Starting from this body of evidence and using the analogy to a dimmer-switch, the premise of this review was to posit the neuromodulatory role of CCK in anxiety and schizophrenia.

2. PHYSIOLOGICAL ROLES OF CCK IN CORTICO-LIMBIC AREAS AND MESOLIMBIC PATHWAYS

2.1. CCK Function in Cortical Micro-circuitry Dynamics

CCK is widely distributed in GABAergic basket cells (CCK+-GABA BCs) of the isocortex [51, 52]. These interneurons are concentrated in layers IV and VI of the human cortex [53], and layers II and III, deep layer V, and layer VI in the rodent cortex [54]. In these areas, pyramidal neurons are the primary target of CCK [55]. CCK colocalizes with glutamate neurons and controls glutamatergic excitatory projections and local GABAergic BCs that gate signal flow and sculpt network dynamics [56]. CCK+-GABA BCs receive information from distinct sources and multiple modulatory systems, by mostly inhibitory [57] and to a lesser extent from glutamatergic afferents [58], thus integrating these inputs over longer time windows to shape and respond to subtleties of principal cell outputs [25, 59]. Cortical CCK is also expressed in the somatostatin Martinotti interneurons of the somatosensory cortex [60] which exerts inhibitory actions regulating the balance between bottom-up and top-down inputs across layers [61].

An important feature of the transmission at CCK+-GABA BCs and their downstream targets compared to their fast spiking parvalbumin immune-positive GABAergic BC counterparts (PV+-GABA BCs) is the accommodation of firing patterns from largely synchronous neurotransmitter release to an asynchronous mode during repetitive activation [37, 62, 63]. This strategic innervation enables both networks of GABAergic BCs, CCK+ and PV+ interneurons, to effectively control the gain of summated synaptic potentials and the action potential discharge of the target (pyramidal) cells. Such adapting discharge may enhance temporal integrative capacity of CCK+-GABA BCs [64], thereby making them responsive to combined input from temporally and physically more separated inputs [65]. A balance between CCK+-GABA and PV+-GABA BCs in a given cortical region is related to the type of processing that area performs. Inhibitory networks in the secondary cortex tend to favor the inclusion of CCK+-GABA BCs more than networks in the primary cortex [66]. CCK is likely to regulate the relationships between both BC interneurons [67], which may have an impact on anxiety [68].

In the basolateral amygdala (BLA), subpopulations of CCK+-GABA BCs are responsible for the anxiogenic effects of CCK [69, 70]. Glutamate-responsive GABAergic neurons rich in CCK2 receptors control the trafficking of nerve impulses from the cerebral cortex to the central amygdala to produce its disinhibition and to trigger anxiety-like behaviors [71]. The efferents of the principal (pyramidal) neurons of the BLA are under the influence of perisomatic CCK+-GABA BCs [72, 73] and the inhibition of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons [74] to modulate the cognitive component of anxiety and fear [75].

Finally, a body of evidence demonstrates that CCK is a potent anticonvulsant neuropeptide [76-78]. There is a loss of CCK+-GABA BCs synapses in animal models of epilepsy [79-82]. In humans, the content of CCK decreases in the tissue of the active focus of epileptic spiking [83]. CCK consistently modulates neuronal inhibitory projections in the cortex.

2.2. CCK and Hippocampal Electrical Oscillations

CCK is largely expressed in inhibitory interneurons BCs, the major subclass of GABA interneurons in the hippocampus [52, 63, 84-87], and the dentate gyrus or DG [88]. Except for a minority that innervates other CCKergic interneurons, most CCK+-GABA BCs of the hippocampus possess axons that cross considerable distances to synapse onto the somata and proximal dendrites of the pyramidal neurons [37]. They do so in parallel with the second inhibitory PV+-GABA BC network [86]. CCK might directly excite PV+-GABA BCs by activating CCK2 receptors [89] and efficiently interfere with action potential generation of PV+-GABA BCs [90]. CCK excitates PV+-GABA BCs and indirectly suppresses GABA release from CCK+-GABA BCs in neuronal microcircuits to gate, like a molecular switch, the different sources of perisomatic inhibition for pyramidal cells [91].

CCK released endogenously from hippocampal interneurons facilitates glutamatergic transmission [92]. This is of special relevance to the CA3 subfield, a key region of the hippocampus for the generation of behaviorally relevant synchronous activity patterns, where CCK+-GABA BCs underlie information processing [93, 94], schizophrenia [63], and the modulation of anxiety [95]. CCK is also present in efferent or afferent pathways originating from CCK+-pyramidal cells of the hippocampal formation and/or from the hippocampal subcortical nuclei, the supramammillary nuclei, and the dorsomedial nucleus of the hypothalamus [96]. Finally, CCK+ -GABA BCs are also modulators of neuronal circuits [91, 97] and assist in the maturation of glutamatergic synapses, i.e. activation of N-methyl -D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, via GABAergic depolarization of the dendrites of the principal cells [98].

As to the DG, CCK+-GABA BCs release GABA in a highly asynchronous manner to generate long-lasting inhibition of the brain [62]. The inhibitory control in the hilar region is qualitatively different from other cortical areas [99]. CCK+-GABA BC somas almost exclusively reside at the subgranular hilar border and polymorphic layer [88]. Synaptic inhibitory interactions exist between CCK+ hilar commissural, associational path cells [88], among CCK+ Schaffer collateral associated interneurons in the stratum radiatum [100]; and between homologous pairs of CCK+-GABA BCs [101]. Certain essential cognitive processes require the precise temporal interplay between excitatory pyramidal cells and inhibitory interneurons in the hippocampus [102]. CCK+-GABA BCs may play a role in the generation and information processing of theta (4-10 Hz) oscillations [103]. The numerous GABAergic inputs to CCK+-GABA BCs do undergo long-term potentiation (LTP) during theta burst stimulation of the hippocampus, presumably leading to disinhibition of pyramidal cells during theta rhythm-associated behavioral states [64]. CCK occupies a privileged position to control the function of the first region where all sensory modalities merge together to build unique representations and memories that bind stimuli together.

2.3. CCK Role in Learning and Memory

Of relevance, CCK+-GABA BCs release glutamate in their efferents to principal cells [49, 52, 104, 105], being their activity critical for working memory retrieval [6]. The glutamate released under the control of these interneurons activates NMDA receptors, which subsequently stimulates cortical CCK expression [106]. In the hippocampus, CCK expression enhances glutamate [107], modulates NMDA receptors [108], and enhances long-term potentiation via CCK2 receptors [109]. There is evidence that CCK participates in both associative [106] and social memories [3]. Because CCK+-GABA BCs are critical for a correct behavioral function [110], CCK disturbances may underlie the learning deficits that are associated with anxiety disorders [111] and schizophrenia [44,112].

2.4. Cortical Modulation of Striatal DA Neurotransmission by CCK and Glutamate

Glutamatergic cortifugal pathways from wide areas of the cortex converge the striatum [113] and the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to enhance the discharge of dopamine (DA) in the nucleus accumbens [114]. CCK colocalizes with DA in the pathways ascending from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens [23], where it intimately modulates DA release at the presynaptic terminals through CCK1 and CCK2 receptors [7]. Crossed corticostriatal projections containing releasable CCK and glutamate project onto the terminal fields of the striatal/accumbens neurons [50]. Of special interest are the CCK projections arising from the mPFC [115], which control DA release in the nucleus accumbens [116]. Corticostriatal CCK neurons, which probably have glutamate as their co-transmitter, might promote goal-directed behaviors [39]. Therefore, dysfunction of CCK [8, 117-121] and glutamate transmission [46] in these pathways may provoke adaptational deficits, impulsive behaviors, and schizophrenia.

In the striatum, cortical glutamate projections establish complex interactions with DA via NMDA and D2D receptors to tonically regulate CCK expression [122]. In turn, CCK released in the striatum may modulate the excitability of glutamate via CCK1 and CCK2 receptors [123], as well as of other amino acids and opioids also released by neostriatal neurons [124]. In addition, activation of CCK2 receptors in striatal neurons stimulates GABA neurotransmission [38], the main output toward the thalamus and a putative site of pharmacological intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia [125]. In agreement with this hypothesis, some evidence suggests that CCK2 antagonists inhibit the activity of DA neurons [126]. How exactly CCK is coreleased with glutamate to impact on accumbal DA turnover is not known and should be considered in future research since disturbances of the basal striatum are the cause of cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia [46, 127].

3. PHARMACOLOGY OF CCK+-GABA BCs

3.1. CCK1 and CCK2 Receptors

The activation of G protein-coupled CCK2 receptors facilitates the excitability of pyramidal neurons [128, 129] and control GABA released by CCK+ BCs [130]. CCK can signal not only through the CCK+-GABA BCs, but even within the PV+-GABA BCs to provide divergence and specificity to its effects [89]. Despite the high density of CCK2 receptors in the cortex, the role of CCK1 receptors in anxiety cannot be overlooked even if the absence of specific ligands for the CCK1 receptor has complicated its study [131]. At this point, it should be considered that CCK-induced anxiety implies the activation of both CCK1 and CCK2 receptors in the cortex [132], that stress-induced fear conditioning upregulates the expression of both CCK1 and CCK2 receptors in the BLA [133], and also that highly specific CCK1 antagonists may have some anxiolytic-like effects in animal models [134].

3.2. Retrograde Inhibition of CCK+-GABA BCs by Endocannabinoids

CCK+-GABA BCs are downstream the activation of cannabinoid 1 (CB1) receptors in rodents [91, 135-139] and in the monkey [140]. The release of GABA from CCK+ interneurons is under the homosynaptic tonic inhibition of endocannabinoids (eCBs) [141] via CB1 activation [142]. In hippocampal networks, cannabinoid-mediated modulation largely operates via presynaptic receptors located on CCK+-GABA BC terminals [143, 144]. GABA released by these interneurons is also subjected to both direct and indirect modulation of acetylcholine and glutamate [141]. Synaptic facilitation between CCK+-Shaffer collateral afferent interneurons is likely to modify the onset of CB1-mediated retrograde inhibition to affect spike timing and the expression of anxiety [100].

In the cortex, CB1 and CCK2 receptors modulate cortical GABAergic neurotransmission and anxiety in opposite directions [145]. eCB-signaling machinery controls the excitability of BLA pyramidal neurons [146, 147], as well as the dynamic regulation of perisomatic inhibition [148], through the retrograde activation of CB1 receptors [139, 149]. Also, in the BLA, the eCB-CCK interplay is required for the extinction of aversive memories [150]. CB1 receptors are located in the amygdala projection CCK+-glutamatergic neurons to the nucleus accumbens that control mood stability [151]. A cooperation between glutamate and CCK via CCK2 occurs during the induction and regulation of the eCB-mediated retrograde signaling in cortical and amygdaloid regions [152]. Because CB1 receptors widely mediate endocannabinoid effects on glutamatergic and GABAergic transmission to modulate cortical networks and the expression of anxiety and fear [153], the role of CCK-CB1-glutamate interactions in fear-related psychiatric diseases [154, 155] awaits further research.

3.3. Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapsis in CCK+-GABA BCs

The dendrites of the CCK+-GABA BCs receive both glutamatergic afferents and GABAergic [56]. While glutamate activates NMDA receptors to release CCK [156], GABA activates GABAB receptors in the dendritic terminals of CCK+-GABA BCs, which are present at higher densities than in PV+-GABA BCs [157]. In the hippocampus, dendritic inhibition is also induced by somatostatin to modulate the activity pattern of CCK+-GABA BCs and the flow of information toward the DG circuitry [88]. As to CCK+-GABA BC terminals, GABAB auto-receptors reduce perisomatic inhibition of pyramidal cells in hippocampal networks [158], while glutamate released by these terminals [49] activates metabotropic and kainate receptors [52]. Postsynaptically, GABAB receptors mediate the long-term depression induced by the GABA released from CCK+-GABA BCs [159], whereas GABAA mediates the neuronal inhibition induced by PV+-GABA BCs on principal neurons [37]. The activation of GABAB receptors attenuates the anxiogenic effects of CCK in the hippocampus [160, 161], suggesting that GABAB agonists might be useful in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal [162].

Where GABA attenuates excitability, the vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons provide network disinhibition in the hippocampal formation. VIP coexists with CCK in the subset of GABA BCs that control the activity of GABAergic granule cells via perisomatic inhibition [85, 163, 164]. VIP interneurons are specialized in synchronized pyramidal neuron ensembles along the hippocampal-subicular axis that may be necessary for memory consolidation [165] and in modulating emotional processes and adaptive responses to stressful stimuli [166]. VIP interneurons regulate the information flow across hippocampus-prefrontal networks to drive avoidance behavior [167]. VIP [168] and CCK [169] mediates neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus, a process critical for mood homeostasis [170]. NPY locally affects the activity of CCK+-GABA BCs to change the way these interneurons process extra-hippocampal afferent information, influencing hippocampal function and its network excitability during normal and pathological oscillatory activities. [171]. Dysfunctional NPY+ interneurons trigger anxiety [110, 172-175] and schizophrenia [176] via CCK+-GABA BCs.

4. CCK-MEDIATED NEUROMODULATION OF ANXIETY AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

4.1. The CCK Dichotomy in Anxiety-related Pain and Fear

CCK interacts with endogenous opioids [5] to reduce anxiety in animal models [177] and to modulate the affective component of pain in humans [178]. Nevertheless, the precise nature of their interactive influence remains elusive. While antagonistic CCK-opioid interactions trigger anxiety-induced hyperalgesia [5, 178-180], activation of CCK2 receptors [181] and eCB [182] may even produce stress-induced analgesia. This dichotomy points to the PAG, which works like a dimmer-switch of fear-motivated behaviors [183]. The PAG is where the administration of CCK may either elicit or inhibit anxiety-like responses [184], where CCK both opposes and reinforces the anxiolytic effects of opioids and eCBs [185], and where CCK elicits either defense/avoidance [186] or aggression behaviors [187]. Finally, neuromodulation of anxiety extends to the amygdala and the nucleus accumbens, where CCK increases arousal and enhances fear extinction, respectively [188].

4.2. CCK2 Receptors and the Adaptation to Stress

Some evidence casts a shadow of doubt over whether the activation of CCK2 receptors triggers anxiety [14]. For instance, CCK2-KO mice do not consistently behave less anxious than their wild-type littermates [189-191] and have problems adapting to the environment [192]. Also, CCK-KO mice exhibit an anxious trait [193], suggesting that CCK may not generate anxiety directly. CCK2 receptors modulate the CCK tone, which in turn contributes to anxiety expression [194]. In this situation, the release of CCK anticipates the occurrence of stress [195] and provides relief both during and after stress [196, 197]. Moreover, CCK signaling in the lateral amygdala is required for the recovery from fear [198]. Thus, it is not surprising that in one clinical trial, the baseline of panic attack frequency in panic disorder patients under chronic treatment with CCK2 receptor antagonist was greater than in the placebo group [20]. In this vein, the panic challenge with CCK4, the gold standard CCK2 agonist, inhibits the HPA axis and produces a reduction of anxiety [199]. The association between CCK gene expression and post-traumatic stress disorder [133, 200] supports the notion that certain levels of CCK2 receptor activity might be necessary to restore the normal levels of anxiety [201].

4.3. CCK and the Fine Tuning of DA Turnover

The colocalization of CCK and DA in the mesolimbic pathways [23] justified the interest of CCK as a pharmacological target of schizophrenia [202, 203]. Given the influence of CCK on accumbal DA [7, 187, 204, 205], it was believed that CCK agonists may be a promising treatment of those mental disorders that resulted from excessive DA release [206, 207]. Neither the CCK agonism therapy [202] nor the altered DAergic predictions in schizophrenia [208] were accurate.

CCK neurotransmission mediates DA turnover [7,209]. As a result of schizophrenia, CCK gene expression is reduced in the entorhinal cortex [210], limbic lobe [211,212], frontal and temporal lobes [213], while the concentration of CCK decreases in cerebrospinal fluid [34,214]. Moreover, there is a loss of CCK binding sites in the cortex and the hippocampus [215,216] and reduced CCK neurotransmission in the frontal cortex [217]. In contrast, CCK expression is enhanced in the midbrain DA cells of schizophrenic brains [218]. Similar to CCK, there is a co-occurrence of high and low DA activities in mesolimbic DA neurons and preprontal cortex, respectively, in schizophrenia [208].

Frontal cortico-accumbens glutamatergic and mesolimbic dopaminergic afferent interactions [47] along with disturbances in the cell firing within the basal striatum participate in the physiopathology of schizophrenia [219-221]. CCK1 receptors occupy a pivotal position at this interface due to their localization in the somatodendritic region of DA neurons of the VTA in rodents [222] and monkeys [223] as well as in the DAergic terminals of the caudal nucleus accumbens [7], and striatal spiny neurons [123] from where they modulate DA release [224, 225] to enhance reward-related behaviors [8, 9, 177, 226]. Interestingly, strong genetic evicence connects CCK1 receptors to schizophrenia [177, 227]. It is also hypothesized that the CCK1 receptor may be a potential link of the comorbidity of schizophrenia and substance of abuse [228], since it may kindle DA release in the accumbens to the detriment of DA neurotransmission in the cortex.

5. THE DIMMER-SWITCH-LIKE NEUROMODULA-TION OF CCK IN ANXIETY AND SCHIZOPHRENIA

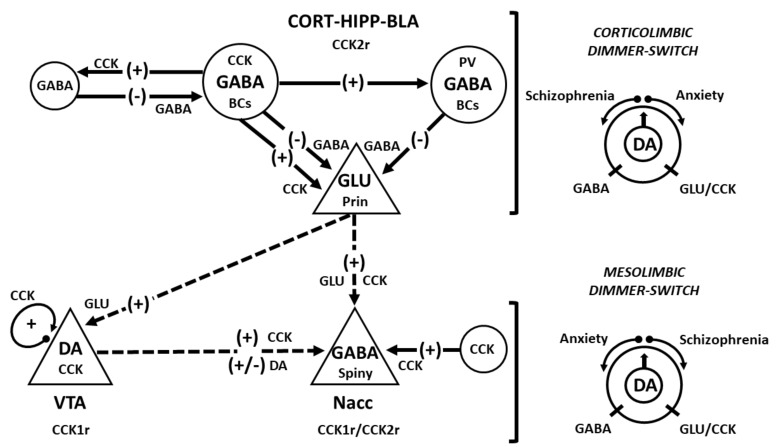

The puzzling role of CCK in anxiety and schizophrenia could be explained using the analogy of a dimmer switch that simultaneously turns up and down the levels of both cognitive processing and motivation to adjust behavioral states (Fig. 1). The first node point of this model may operate through the GABA-glutamate interplay in corticolimbic areas, including the hippocampus [37, 52] to shift cortical dynamics from synchronous to asynchronous when appropriate and thus facilitate information processing and behavioral performance [67,229]. Failure in CCK2 receptors, and perhaps in CCK1 receptors in corticolimbic areas [132, 133, 194], may lead to maladaptive learning and anxiety [117, 230]. A second dimmer swicht may consist of the interface of cortico-accumbal and mesolimbic pathways, i.e. the nucleus accumbens, which dims the salience of stimuli signaled by patterns of DAergic discharge [220].

Although anxiety is inextricably related to the first episode of psychosis, or acute relapses [231], this temporal precedence is not equivalent to causality. It better suggests that anxiety may be the catalyst that triggers distressing experiences of psychosis in more vulnerable individuals [36]. Psychosis and anxiety are triggered by a common cause, the imbalances in the DA innervation, both in terms of phasic activation and attenuation of tonic DA [232]. A sustained deficiency in mesocortical DA function [208, 233] is likely to alter the fronto–striato–thalamic pathway [234] during the early stages of schizophrenia. The prefrontal cortex, a structure critically involved in both the vulnerability to stress and the cognitive deficits in schizophrenia [235], is influenced by the release of DA from the midbrain. In turn, a deficit in glutamatergic projection from the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex to midbrain DAergic neurons might alter some cognitive circuitries [236], thus affecting working memory in schizophrenia [237]. Given the direct control of striatal DA release by glutamatergic corticostriatal afferents [238], an increment of the CCK tone may compensate a deficitary working memory [6] at the expense of increasing the occurrence of anxiety at the beginning of schizophrenia [36]. As schizophrenia progresses, the overstimulation of CCK may lead to an internalization of the CCK2 receptor [239], which would account for the reduction of CCK2 binding sites observed in post-mortem schizophrenic brains [216, 217].

CCK is not only a dimmer-switch of GABA, but also of DA (see the graphical abstract). The interplay between cognition and reward circuitries in schizophrenia [221] depends on how CCK modulates accumbal DA turnover [9], which is either enhanced by cortical glutamate and likely CCK via CCK1 receptors [224, 225] or dimed by striatal GABA through CCK2 receptors [38]. Cognitive performance in mental health and disease relies on the adequate levels of CCK expression in both cortical areas [240], and in mesolimbic pathways [188], which is likely to be the cornerstone of the excitatory-inhibitory dynamics in limbic neural networks. Given its multi-functional molecular switch role in neuronal circuits [91], CCK could work as the universal dimmer of many neurotransmitters during the adjustments at the onset of mental illnesses.

CONCLUSION

In sum, the neuromodulatory role of CCK may be compared to the work of a dimmer-switch that may turn up (via glutamate plus CCK), and down (via GABA), the flux of DA-mediated neurotransmission across corticomesolimbic neural formations. That could explain the anxiety linked to the withdrawal of drugs, including alcohol. This hypothesis would strongly support the development of new partial CCK1 and CCK2 receptor agonists with varied grades of CCK receptor selectivity for the treatment of anxiety and schizophrenia.

Fig. (1).

Diagram of the dimmer-switch hypothesis regarding the role of CCK in anxiety and schizophrenia. The diagram shows the main circuitry of the corticomesolimbic system: (1) interneurons (circles) forming microcircuitries connected by solid-arrow lines and (2) projection neurons (triangles) with their efferents like dashed-arrow lines. Inhibition (negative signs) is produced by GABA, which interacts with GABAA and GABAB receptors located in principal glutamatergic cells (not shown). Excitatory (positive signs) impulses are transmitted by CCK and glutamate (GLU). The CCK2 receptor (CCK2r) predominates in corticolimbic areas, while the CCK1 receptor (CCK1r) is more abundant in the VTA. Both CCK1r and CCK2r are present presynaptically in DAergic terminals and postsynaptically in striatal neurons. CCK is co-released with DA, which has both excitatory (via D1D receptors) and inhibitory (via D2D receptors) effects on accumbal GABAergic (spiny) neurons. The putative disequilibriums in corticomesolimbic pathways are represented by dimmer-switches. The hypothesis posits hyperactivity of corticolimbic areas (excessive GLU by dysregulated CCK) is detrimental to the mesolimbic pathways in the development of anxiety. In contrast, if the activity of the mesolimbic pathways was unusually higher (fast DA turnover) than in corticolimbic areas (excess of GABA), it may progress to schizophrenia. Abbreviations: basket cells (BCs); basolateral amygdala (BLA), cortex (Cort), hippocampus (Hypp), principal/pyramidal neurons (Prin); parvalbumin (PV), nucleus accumbens (Nacc), and ventral tegmental area (VTA).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Prof. Margery Beinfeld from Tufts University for the proofreading of the manuscript.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- BCs

Basket cells

- PV

Parvalbumin

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

FUNDING

None.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dockray G.J. Cholecystokinins in rat cerebral cortex: identification, purification and characterization by immunochemical methods. Brain Res. 1980;188(1):155–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90564-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Innis R.B., Snyder S.H. Distinct cholecystokinin receptors in brain and pancreas. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1980;77(11):6917–6921. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.11.6917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lemaire M., Piot O., Roques B.P., Böhme G.A., Blanchard J.C. Evidence for an endogenous cholecystokininergic balance in social memory. Neuroreport. 1992;3(10):929–932. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daugé V., Léna I. CCK in anxiety and cognitive processes. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1998;22(6):815–825. doi: 10.1016/S0149-7634(98)00011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hebb A.L., Poulin J.F., Roach S.P., Zacharko R.M., Drolet G. Cholecystokinin and endogenous opioid peptides: interactive influence on pain, cognition, and emotion. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2005;29(8):1225–1238. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nguyen R., Venkatesan S., Binko M., Bang J.Y., Cajanding J.D., Briggs C., Sargin D., Imayoshi I., Lambe E.K., Kim J.C. Cholecystokinin-expressing interneurons of the medial prefrontal cortex mediate working memory retrieval. J. Neurosci. 2020;40(11):2314–2331. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1919-19.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaccarino F.J. Nucleus accumbens dopamine-CCK interactions in psychostimulant reward and related behaviors. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1994;18(2):207–214. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(94)90025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crespi F., Corsi M., Reggiani A., Ratti E., Gaviraghi G. Involvement of cholecystokinin within craving for cocaine: role of cholecystokinin receptor ligands. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2000;9(10):2249–2258. doi: 10.1517/13543784.9.10.2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rotzinger S., Vaccarino F.J. Cholecystokinin receptor subtypes: role in the modulation of anxiety-related and reward-related behaviours in animal models. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 2003;28(3):171–181. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bradwejn J., Koszycki D., Meterissian G. Cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide induces panic attacks in patients with panic disorder. Can. J. Psychiatry. 1990;35(1):83–85. doi: 10.1177/070674379003500115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harro J., Vasar E., Bradwejn J. CCK in animal and human research on anxiety. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14(6):244–249. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90020-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moran T.H., Schwartz G.J. Neurobiology of cholecystokinin. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1994;9(1):1–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourin M., Malinge M., Vasar E., Bradwejn J. Two faces of cholecystokinin: anxiety and schizophrenia. Fundam. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;10(2):116–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1996.tb00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Megen H.J., Westenberg H.G., den Boer J.A., Kahn R.S. Cholecystokinin in anxiety. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1996;6(4):263–280. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(96)00038-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H., Wong P.T., Spiess J., Zhu Y.Z. Cholecystokinin-2 (CCK2) receptor-mediated anxiety-like behaviors in rats. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2005;29(8):1361–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koszycki D., Prichard Z., Fiocco A.J., Shlik J., Kennedy J.L., Bradwejn J. CCK-B receptor gene and response to cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide in healthy volunteers. Peptides. 2012;35(1):9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bradwejn J., Koszycki D. Cholecystokinin and panic disorder: past and future clinical research strategies. Scand. J. Clin. Lab. Invest. Suppl. 2001;234(Suppl. 234):19–27. doi: 10.1080/713783681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zwanzger P., Domschke K., Bradwejn J. Neuronal network of panic disorder: the role of the neuropeptide cholecystokinin. Depress. Anxiety. 2012;29(9):762–774. doi: 10.1002/da.21919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abelson J.L. Cholecystokinin in psychiatric research: a time for cautious excitement. J. Psychiatr. Res. 1995;29(5):389–396. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00027-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer M.S., Cutler N.R., Ballenger J.C., Patterson W.M., Mendels J., Chenault A., Shrivastava R., Matzura-Wolfe D., Lines C., Reines S. A placebo-controlled trial of L-365,260, a CCKB antagonist, in panic disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 1995;37(7):462–466. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(94)00190-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rodgers R.J., Johnson N.J. Cholecystokinin and anxiety: promises and pitfalls. Crit. Rev. Neurobiol. 1995;9(4):345–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu Y., Dang M., Li H., Jin X., Yang W. Identification of genes related to mental disorders by text mining. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98(42):e17504. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hökfelt T., Rehfeld J.F., Skirboll L., Ivemark B., Goldstein M., Markey K. Evidence for coexistence of dopamine and CCK in meso-limbic neurones. Nature. 1980;285(5765):476–478. doi: 10.1038/285476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rotzinger S., Bush D.E., Vaccarino F.J. Cholecystokinin modulation of mesolimbic dopamine function: regulation of motivated behaviour. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;91(6):404–413. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910620.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freund T.F., Katona I. Perisomatic inhibition. Neuron. 2007;56(1):33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Agrawal P., Kao D., Chung P., Looger L.L. The neuropeptide Drosulfakinin regulates social isolation-induced aggression in Drosophila. J. Exp. Biol. 2020;223(Pt 2):jeb207407. doi: 10.1242/jeb.207407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feifel D., Swerdlow N.R. The modulation of sensorimotor gating deficits by mesolimbic cholecystokinin. Neurosci. Lett. 1997;229(1):5–8. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(97)00409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koszycki D., Zacharko R.M., Bradwejn J. Influence of personality on behavioral response to cholecystokinin-tetrapeptide in patients with panic disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1996;62(2):131–138. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02819-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aluoja A., Shlik J., Vasar V., Kingisepp P.H., Jagomägi K., Vasar E., Bradwejn J. Emotional and cognitive factors connected with response to cholecystokinin tetrapeptide in healthy volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1997;66(1):59–67. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)02948-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Le Mellédo J.M., Merani S., Koszycki D., Bellavance F., Palmour R., Gutkowska J., Steinberg S., Bichet D.G., Bradwejn J. Sensitivity to CCK-4 in women with and without premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) during their follicular and luteal phases. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(1):81–91. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00057-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maron E., Tõru I., Mäemets K., Sepp S., Vasar V., Shlik J., Zharkovsky A. CCK-4-induced anxiety but not panic is associated with serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in healthy subjects. J. Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(4):460–464. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hinkelmann K., Yassouridis A., Mass R., Tenge H., Kellner M., Jahn H., Wiedemann K., Wolf K. CCK-4: Psychophysiological conditioning elicits features of spontaneous panic attacks. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2010;44(16):1148–1153. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tõru I., Aluoja A., Võhma U., Raag M., Vasar V., Maron E., Shlik J. Associations between personality traits and CCK-4-induced panic attacks in healthy volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178(2):342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beinfeld M.C., Garver D.L. Concentration of cholecystokinin in cerebrospinal fluid is decreased in psychosis: relationship to symptoms and drug response. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 1991;15(5):601–609. doi: 10.1016/0278-5846(91)90050-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mauri M.C., Rudelli R., Vanni S., Panza G., Sicaro A., Audisio D., Sacerdote P., Panerai A.E. Cholecystokinin, beta-endorphin and vasoactive intestinal peptide in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of drug-naive schizophrenic patients treated with haloperidol compared to healthy controls. Psychiatry Res. 1998;78(1-2):45–50. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(97)00145-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hartley S., Barrowclough C., Haddock G. Anxiety and depression in psychosis: a systematic review of associations with positive psychotic symptoms. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2013;128(5):327–346. doi: 10.1111/acps.12080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Armstrong C., Soltesz I. Basket cell dichotomy in microcircuit function. J. Physiol. 2012;590(4):683–694. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.223669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Connor W.T. Functional neuroanatomy of the ventral striopallidal GABA pathway. New sites of intervention in the treatment of schizophrenia. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2001;109(1):31–39. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0270(01)00398-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hökfelt T., Blacker D., Broberger C., Herrera-Marschitz M., Snyder G., Fisone G., Cortés R., Morino P., You Z.B., Ogren S.O. Some aspects on the anatomy and function of central cholecystokinin systems. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2002;91(6):382–386. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0773.2002.910617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nikolaus S., Antke C., Beu M., Müller H.W. Cortical GABA, striatal dopamine and midbrain serotonin as the key players in compulsive and anxiety disorders--results from in vivo imaging studies. Rev. Neurosci. 2010;21(2):119–139. doi: 10.1515/REVNEURO.2010.21.2.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zwanzger P., Zavorotnyy M., Gencheva E., Diemer J., Kugel H., Heindel W., Ruland T., Ohrmann P., Arolt V., Domschke K., Pfleiderer B. Acute shift in glutamate concentrations following experimentally induced panic with cholecystokinin tetrapeptide--a 3T-MRS study in healthy subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2013;38(9):1648–1654. doi: 10.1038/npp.2013.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bachus S.E., Kleinman J.E. The neuropathology of schizophrenia. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl. 11):72–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hashimoto T., Arion D., Unger T., Maldonado-Avilés J.G., Morris H.M., Volk D.W., Mirnics K., Lewis D.A. Alterations in GABA-related transcriptome in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex of subjects with schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2008;13(2):147–161. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Curley A.A., Lewis D.A. Cortical basket cell dysfunction in schizophrenia. J. Physiol. 2012;590(4):715–724. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu W., MacDonald M.L., Elswick D.E., Sweet R.A. The glutamate hypothesis of schizophrenia: evidence from human brain tissue studies. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2015;1338:38–57. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jauhar S., McCutcheon R., Borgan F., Veronese M., Nour M., Pepper F., Rogdaki M., Stone J., Egerton A., Turkheimer F., McGuire P., Howes O.D. The relationship between cortical glutamate and striatal dopamine in first-episode psychosis: a cross-sectional multimodal PET and magnetic resonance spectroscopy imaging study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(10):816–823. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(18)30268-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roberts C.R., McCollum L.A., Schoonover K.E., Mabry S.J., Roche J.K., Lahti A.C. Ultrastructural evidence for glutamatergic dysregulation in schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 2020;••• doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2020.01.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sobrido-Cameán D., Yáñez-Guerra L.A., Robledo D., López-Varela E., Rodicio M.C., Elphick M.R., Anadón R., Barreiro-Iglesias A. Cholecystokinin in the central nervous system of the sea lamprey Petromyzon marinus: precursor identification and neuroanatomical relationships with other neuronal signalling systems. Brain Struct. Funct. 2020;225(1):249–284. doi: 10.1007/s00429-019-01999-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pelkey K.A., Calvigioni D., Fang C., Vargish G., Ekins T., Auville K., Wester J.C., Lai M., Mackenzie-Gray Scott C., Yuan X., Hunt S., Abebe D., Xu Q., Dimidschstein J., Fishell G., Chittajallu R., McBain C.J. Paradoxical network excitation by glutamate release from VGluT3+ GABAergic interneurons. eLife. 2020;9:e51996. doi: 10.7554/eLife.51996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Herrera-Marschitz M., Meana J.J., Hökfelt T., You Z.B., Morino P., Brodin E., Ungerstedt U. Cholecystokinin is released from a crossed corticostriatal pathway. Neuroreport. 1992;3(10):905–908. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199210000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kawaguchi Y., Kondo S. Parvalbumin, somatostatin and cholecystokinin as chemical markers for specific GABAergic interneuron types in the rat frontal cortex. J. Neurocytol. 2002;31(3-5):277–287. doi: 10.1023/A:1024126110356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Somogyi J., Baude A., Omori Y., Shimizu H., El Mestikawy S., Fukaya M., Shigemoto R., Watanabe M., Somogyi P. GABAergic basket cells expressing cholecystokinin contain vesicular glutamate transporter type 3 (VGLUT3) in their synaptic terminals in hippocampus and isocortex of the rat. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19(3):552–569. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2003.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhu Q., Ke W., He Q., Wang X., Zheng R., Li T., Luan G., Long Y-S., Liao W-P., Shu Y. Laminar distribution of neurochemically-identified interneurons and cellular co-expression of molecular markers in epileptic human cortex. Neurosci. Bull. 2018;34(6):992–1006. doi: 10.1007/s12264-018-0275-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burgunder J.M., Young W.S., III Cortical neurons expressing the cholecystokinin gene in the rat: distribution in the adult brain, ontogeny, and some of their projections. J. Comp. Neurol. 1990;300(1):26–46. doi: 10.1002/cne.903000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gallopin T., Geoffroy H., Rossier J., Lambolez B. Cortical sources of CRF, NKB, and CCK and their effects on pyramidal cells in the neocortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2006;16(10):1440–1452. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tremblay R., Lee S., Rudy B. Rudy. B. GABAergic interneurons in the neocortex: From cellular properties to circuits. Neuron. 2016;91(2):260–292. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mátyás F., Freund T.F., Gulyás A.I. Convergence of excitatory and inhibitory inputs onto CCK-containing basket cells in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2004;19(5):1243–1256. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2004.03225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nissen W., Szabo A., Somogyi J., Somogyi P., Lamsa K.P. Cell type-specific long-term plasticity at glutamatergic synapses onto hippocampal interneurons expressing either parvalbumin or CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J. Neurosci. 2010;30(4):1337–1347. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3481-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu X., Liu S. Cholecystokinin selectively activates short axon cells to enhance inhibition of olfactory bulb output neurons. J. Physiol. 2018;596(11):2185–2207. doi: 10.1113/JP275511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wang Y., Toledo-Rodriguez M., Gupta A., Wu C., Silberberg G., Luo J., Markram H. Anatomical, physiological and molecular properties of Martinotti cells in the somatosensory cortex of the juvenile rat. J. Physiol. 2004;561(Pt 1):65–90. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.073353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Naka A., Veit J., Shababo B., Chance R.K., Risso D., Stafford D., Snyder B., Egladyous A., Chu D., Sridharan S., Mossing D.P., Paninski L., Ngai J., Adesnik H. Complementary networks of cortical somatostatin interneurons enforce layer specific control. eLife. 2019;8:e43696. doi: 10.7554/eLife.43696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hefft S., Jonas P. Asynchronous GABA release generates long-lasting inhibition at a hippocampal interneuron-principal neuron synapse. Nat. Neurosci. 2005;8(10):1319–1328. doi: 10.1038/nn1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kohus Z., Káli S., Rovira-Esteban L., Schlingloff D., Papp O., Freund T.F., Hájos N., Gulyás A.I. Properties and dynamics of inhibitory synaptic communication within the CA3 microcircuits of pyramidal cells and interneurons expressing parvalbumin or cholecystokinin. J. Physiol. 2016;594(13):3745–3774. doi: 10.1113/JP272231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Evstratova A., Chamberland S., Topolnik L. Cell type-specific and activity-dependent dynamics of action potential-evoked Ca2+ signals in dendrites of hippocampal inhibitory interneurons. J. Physiol. 2011;589(Pt 8):1957–1977. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.204255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Glickfeld L.L., Scanziani M. Distinct timing in the activity of cannabinoid-sensitive and cannabinoid-insensitive basket cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2006;9(6):807–815. doi: 10.1038/nn1688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Whissell P.D., Cajanding J.D., Fogel N., Kim J.C. Comparative density of CCK- and PV-GABA cells within the cortex and hippocampus. Front. Neuroanat. 2015;9:124. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2015.00124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Freund T.F. Interneuron Diversity series: Rhythm and mood in perisomatic inhibition. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26(9):489–495. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00227-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Çaliskan G., Müller I., Semtner M., Winkelmann A., Raza A.S., Hollnagel J.O., Rösler A., Heinemann U., Stork O., Meier J.C. Identification of parvalbumin interneurons as cellular substrate of fear memory persistence. Cereb. Cortex. 2016;26(5):2325–2340. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhw001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Truitt W.A., Johnson P.L., Dietrich A.D., Fitz S.D., Shekhar A. Anxiety-like behavior is modulated by a discrete subpopulation of interneurons in the basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2009;160(2):284–294. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.01.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Del Boca C., Lutz P.E., Le Merrer J., Koebel P., Kieffer B.L. Cholecystokinin knock-down in the basolateral amygdala has anxiolytic and antidepressant-like effects in mice. Neuroscience. 2012;218:185–195. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pérez de la Mora M., Hernández-Gómez A.M., Arizmendi-García Y., Jacobsen K.X., Lara-García D., Flores-Gracia C., Crespo-Ramírez M., Gállegos-Cari A., Nuche-Bricaire A., Fuxe K. Role of the amygdaloid cholecystokinin (CCK)/gastrin-2 receptors and terminal networks in the modulation of anxiety in the rat. Effects of CCK-4 and CCK-8S on anxiety-like behaviour and [3H]GABA release. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007;26(12):3614–3630. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chung L., Moore S.D. Cholecystokinin enhances GABAergic inhibitory transmission in basolateral amygdala. Neuropeptides. 2007;41(6):453–463. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chung L., Moore S.D. Neuropeptides modulate compound postsynaptic potentials in basolateral amygdala. Neuroscience. 2009;164(4):1389–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lee S., Kim J.H. Basal Forebrain cholinergic-induced activation of cholecystokinin inhibitory neurons in the basolateral amygdala. Exp. Neurobiol. 2019;28(3):320–328. doi: 10.5607/en.2019.28.3.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Berntson G.G., Sarter M., Cacioppo J.T. Anxiety and cardiovascular reactivity: the basal forebrain cholinergic link. Behav. Brain Res. 1998;94(2):225–248. doi: 10.1016/S0166-4328(98)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhang L.X., Smith M.A., Kim S.Y., Rosen J.B., Weiss S.R., Post R.M. Changes in cholecystokinin mRNA expression after amygdala kindled seizures: an in situ hybridization study. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1996;35(1-2):278–284. doi: 10.1016/0169-328X(95)00230-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ferraro G., Sardo P. Cholecystokinin-8 sulfate modulates the anticonvulsant efficacy of vigabatrin in an experimental model of partial complex epilepsy in the rat. Epilepsia. 2009;50(4):721–730. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lambrechts D.A., Brandt-Wouters E., Verschuure P., Vles H.S., Majoie M.J. A prospective study on changes in blood levels of cholecystokinin-8 and leptin in patients with refractory epilepsy treated with the ketogenic diet. Epilepsy Res. 2016;127:87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Fetissov S.O., Jacoby A.S., Brumovsky P.R., Shine J., Iismaa T.P., Hökfelt T. Altered hippocampal expression of neuropeptides in seizure-prone GALR1 knockout mice. Epilepsia. 2003;44(8):1022–1033. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.51402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chen S., Kobayashi M., Honda Y., Kakuta S., Sato F., Kishi K. Preferential neuron loss in the rat piriform cortex following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus. Epilepsy Res. 2007;74(1):1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wyeth M.S., Zhang N., Mody I., Houser C.R. Selective reduction of cholecystokinin-positive basket cell innervation in a model of temporal lobe epilepsy. J. Neurosci. 2010;30(26):8993–9006. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1183-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sun C., Sun J., Erisir A., Kapur J. Loss of cholecystokinin-containing terminals in temporal lobe epilepsy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2014;62:44–55. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2013.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Iadarola M.J., Sherwin A.L. Alterations in cholecystokinin peptide and mRNA in actively epileptic human temporal cortical foci. Epilepsy Res. 1991;8(1):58–63. doi: 10.1016/0920-1211(91)90036-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nunzi M.G., Gorio A., Milan F., Freund T.F., Somogyi P., Smith A.D. Cholecystokinin-immunoreactive cells form symmetrical synaptic contacts with pyramidal and nonpyramidal neurons in the hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;237(4):485–505. doi: 10.1002/cne.902370406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hájos N., Acsady L., Freund T.F. Target selectivity and neurochemical characteristics of VIP-immunoreactive interneurons in the rat dentate gyrus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1996;8(7):1415–1431. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1996.tb01604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Pawelzik H., Hughes D.I., Thomson A.M. Physiological and morphological diversity of immunocytochemically defined parvalbumin- and cholecystokinin-positive interneurones in CA1 of the adult rat hippocampus. J. Comp. Neurol. 2002;443(4):346–367. doi: 10.1002/cne.10118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Pelkey K.A., Chittajallu R., Craig M.T., Tricoire L., Wester J.C., McBain C.J. Hippocampal GABAergic inhibitory interneurons. Physiol. Rev. 2017;97(4):1619–1747. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Savanthrapadian S., Meyer T., Elgueta C., Booker S.A., Vida I., Bartos M. Synaptic properties of SOM- and CCK-expressing cells in dentate gyrus interneuron networks. J. Neurosci. 2014;34(24):8197–8209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5433-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee S.Y., Földy C., Szabadics J., Soltesz I. Cell-type-specific CCK2 receptor signaling underlies the cholecystokinin-mediated selective excitation of hippocampal parvalbumin-positive fast-spiking basket cells. J. Neurosci. 2011;31(30):10993–11002. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1970-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hioki H., Sohn J., Nakamura H., Okamoto S., Hwang J., Ishida Y., Takahashi M., Kameda H. Preferential inputs from cholecystokinin-positive neurons to the somatic compartment of parvalbumin-expressing neurons in the mouse primary somatosensory cortex. Brain Res. 2018;1695:18–30. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.05.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lee S.Y., Soltesz I. Cholecystokinin: a multi-functional molecular switch of neuronal circuits. Dev. Neurobiol. 2011;71(1):83–91. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Deng P-Y., Xiao Z., Jha A., Ramonet D., Matsui T., Leitges M., Shin H-S., Porter J.E., Geiger J.D., Lei S. Cholecystokinin facilitates glutamate release by increasing the number of readily releasable vesicles and releasing probability. J. Neurosci. 2010;30(15):5136–5148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5711-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Del Pino I., Brotons-Mas J.R., Marques-Smith A., Marighetto A., Frick A., Marín O., Rico B. Abnormal wiring of CCK+ basket cells disrupts spatial information coding. Nat. Neurosci. 2017;20(6):784–792. doi: 10.1038/nn.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Whissell P.D., Bang J.Y., Khan I., Xie Y.F., Parfitt G.M., Grenon M., Plummer N.W., Jensen P., Bonin R.P., Kim J.C. Selective activation of cholecystokinin-expressing GABA (CCK-GABA) neurons enhances memory and cognition. eNeuro. 2019;•••:6. doi: 10.1523/ENEURO.0360-18.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Engin E., Smith K.S., Gao Y., Nagy D., Foster R.A., Tsvetkov E., Keist R., Crestani F., Fritschy J.M., Bolshakov V.Y., Hajos M., Heldt S.A., Rudolph U. Modulation of anxiety and fear via distinct intrahippocampal circuits. eLife. 2016;5:e14120. doi: 10.7554/eLife.14120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Greenwood R.S., Godar S.E., Reaves T.A., Jr, Hayward J.N. Cholecystokinin in hippocampal pathways. J. Comp. Neurol. 1981;203(3):335–350. doi: 10.1002/cne.902030303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Földy C., Lee S.Y., Szabadics J., Neu A., Soltesz I. Cell type-specific gating of perisomatic inhibition by cholecystokinin. Nat. Neurosci. 2007;10(9):1128–1130. doi: 10.1038/nn1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morozov Y.M., Freund T.F. Postnatal development and migration of cholecystokinin-immunoreactive interneurons in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2003;120(4):923–939. doi: 10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Acsády L., Katona I., Martínez-Guijarro F.J., Buzsáki G., Freund T.F. Unusual target selectivity of perisomatic inhibitory cells in the hilar region of the rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 2000;20(18):6907–6919. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-18-06907.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ali A.B. Presynaptic Inhibition of GABAA receptor-mediated unitary IPSPs by cannabinoid receptors at synapses between CCK-positive interneurons in rat hippocampus. J. Neurophysiol. 2007;98(2):861–869. doi: 10.1152/jn.00156.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Daw M.I., Tricoire L., Erdelyi F., Szabo G., McBain C.J. Asynchronous transmitter release from cholecystokinin-containing inhibitory interneurons is widespread and target-cell independent. J. Neurosci. 2009;29(36):11112–11122. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5760-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Keimpema E., Straiker A., Mackie K., Harkany T., Hjerling-Leffler J. Sticking out of the crowd: the molecular identity and development of cholecystokinin-containing basket cells. J. Physiol. 2012;590(4):703–714. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.224386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Li S., Xu J., Chen G., Lin L., Zhou D., Cai D. The characterization of hippocampal theta-driving neurons - a time-delayed mutual information approach. Sci. Rep. 2017;7(1):5637. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05527-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wyeth M.S., Zhang N., Houser C.R. Increased cholecystokinin labeling in the hippocampus of a mouse model of epilepsy maps to spines and glutamatergic terminals. Neuroscience. 2012;202:371–383. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.11.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Fasano C., Rocchetti J., Pietrajtis K., Zander J-F., Manseau F., Sakae D.Y., Marcus-Sells M., Ramet L., Morel L.J., Carrel D., Dumas S., Bolte S., Bernard V., Vigneault E., Goutagny R., Ahnert-Hilger G., Giros B., Daumas S., Williams S., El Mestikawy S. Regulation of the hippocampal network by VGLUT3-positive CCK- GABAergic basket cells. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2017;11:140. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2017.00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Chen X., Li X., Wong Y.T., Zheng X., Wang H., Peng Y., Feng H., Feng J., Baibado J.T., Jesky R., Wang Z., Xie H., Sun W., Zhang Z., Zhang X., He L., Zhang N., Zhang Z., Tang P., Su J., Hu L.L., Liu Q., He X., Tan A., Sun X., Li M., Wong K., Wang X., Cheung H.Y., Shum D.K., Yung K.K.L., Chan Y.S., Tortorella M., Guo Y., Xu F., He J. Cholecystokinin release triggered by NMDA receptors produces LTP and sound-sound associative memory. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116(13):6397–6406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816833116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Gabriel S., Grützmann R., Lemke M., Gabriel H.J., Henklein P., Davidowa H. Interaction of cholecystokinin and glutamate agonists within the dLGN, the dentate gyrus, and the hippocampus. Brain Res. Bull. 1996;39(6):381–389. doi: 10.1016/0361-9230(96)00030-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gronier B., Debonnel G. Electrophysiological evidence for the implication of cholecystokinin in the modulation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate response by sigma ligands in the rat CA3 dorsal hippocampus. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353(4):382–390. doi: 10.1007/BF00261434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lemaire M., Barnéoud P., Böhme G.A., Piot O., Haun F., Roques B.P., Blanchard J.C. CCK-A and CCK-B receptors enhance olfactory recognition via distinct neuronal pathways. Learn. Mem. 1994;1(3):153–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Schmidt M.J., Horvath S., Ebert P., Norris J.L., Seeley E.H., Brown J., Gellert L., Everheart M., Garbett K.A., Grice T.W., Caprioli R.M., Mirnics K. Modulation of behavioral networks by selective interneuronal inactivation. Mol. Psychiatry. 2014;19(5):580–587. doi: 10.1038/mp.2013.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bourin M. 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Guo J.Y., Ragland J.D., Carter C.S. Memory and cognition in schizophrenia. Mol. Psychiatry. 2019;24(5):633–642. doi: 10.1038/s41380-018-0231-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Storm-Mathisen J., Leknes A.K., Bore A.T., Vaaland J.L., Edminson P., Haug F.M., Ottersen O.P. First visualization of glutamate and GABA in neurones by immunocytochemistry. Nature. 1983;301(5900):517–520. doi: 10.1038/301517a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Geisler S., Derst C., Veh R.W., Zahm D.S. Glutamatergic afferents of the ventral tegmental area in the rat. J. Neurosci. 2007;27(21):5730–5743. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0012-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Morino P., Mascagni F., McDonald A., Hökfelt T. Cholecystokinin corticostriatal pathway in the rat: evidence for bilateral origin from medial prefrontal cortical areas. Neuroscience. 1994;59(4):939–952. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90297-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.You Z.B., Tzschentke T.M., Brodin E., Wise R.A. Electrical stimulation of the prefrontal cortex increases cholecystokinin, glutamate, and dopamine release in the nucleus accumbens: an in vivo microdialysis study in freely moving rats. J. Neurosci. 1998;18(16):6492–6500. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-16-06492.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Harro J., Marcusson J., Oreland L. Alterations in brain cholecystokinin receptors in suicide victims. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1992;2(1):57–63. doi: 10.1016/0924-977X(92)90037-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Löfberg C., Agren H., Harro J., Oreland L. Cholecystokinin in CSF from depressed patients: possible relations to severity of depression and suicidal behaviour. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 1998;8(2):153–157. doi: 10.1016/S0924-977X(97)00046-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Ballaz S.J., Akil H., Watson S.J. The CCK-system mediates adaptation to novelty-induced stress in the rat: a pharmacological evidence. Neurosci. Lett. 2007;428(1):27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Nordin C., Sjödin I. CSF cholecystokinin, gamma-aminobutyric acid and neuropeptide Y in pathological gamblers and healthy controls. J. Neural Transm. (Vienna) 2007;114(4):499–503. doi: 10.1007/s00702-006-0593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Jahangard L., Solgy R., Salehi I., Taheri S.K., Holsboer-Trachsler E., Haghighi M., Brand S. Cholecystokinin (CCK) level is higher among first time suicide attempters than healthy controls, but is not associated with higher depression scores. Psychiatry Res. 2018;266:40–46. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ding X.Z., Mocchetti I. Regulation of cholecystokinin mRNA content in rat striatum: a glutamatergic hypothesis. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1992;263(1):368–373. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Davidowa H., Albrecht D., Gabriel H.J., Heublein S., Wetzel K. Cholecystokinin excites neostriatal neurons in rats via CCKA or CCKB receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1995;7(12):2364–2369. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1995.tb01033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.You Z.B., Pettersson E., Herrera-Marschitz M., Hökfelt T., Terenius L., Nylander I., Goiny M., Hughes J., O’Connor W.T., Ungerstedt U. Modulation of striatal aspartate and dynorphin B release by cholecystokinin (CCK-8) studied in vivo with microdialysis. Neuroreport. 1994;5(17):2301–2304. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199411000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Fuxe K., Hökfelt T., Ljungdahl A., Agnati L., Johansson O., Perez de la Mora M. Evidence for an inhibitory gabergic control of the meso-limbic dopamine neurons: possibility of improving treatment of schizophrenia by combined treatment with neuroleptics and gabergic drugs. Med. Biol. 1975;53(3):177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Rasmussen K. CCK, schizophrenia, and anxiety. CCK-B antagonists inhibit the activity of brain dopamine neurons. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994;713:300–311. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb44078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Simpson E.H., Kellendonk C., Kandel E. A possible role for the striatum in the pathogenesis of the cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia. Neuron. 2010;65(5):585–596. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Chung L., Moore S.D. Cholecystokinin excites interneurons in rat basolateral amygdala. J. Neurophysiol. 2009;102(1):272–284. doi: 10.1152/jn.90769.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wang S., Zhang A.P., Kurada L., Matsui T., Lei S. Cholecystokinin facilitates neuronal excitability in the entorhinal cortex via activation of TRPC-like channels. J. Neurophysiol. 2011;106(3):1515–1524. doi: 10.1152/jn.00025.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pérez de la Mora M., Hernandez-Gómez A.M., Méndez-Franco J., Fuxe K. Cholecystokinin-8 increases K(+)-evoked [3H] gamma-aminobutyric acid release in slices from various brain areas. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;250(3):423–430. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90029-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ballaz S. The unappreciated roles of the cholecystokinin receptor CCK(1) in brain functioning. Rev. Neurosci. 2017;28(6):573–585. doi: 10.1515/revneuro-2016-0088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Li H., Ohta H., Izumi H., Matsuda Y., Seki M., Toda T., Akiyama M., Matsushima Y., Goto Y., Kaga M., Inagaki M. Behavioral and cortical EEG evaluations confirm the roles of both CCKA and CCKB receptors in mouse CCK-induced anxiety. Behav. Brain Res. 2013;237:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2012.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Feng T., Yang S., Wen D., Sun Q., Li Y., Ma C., Cong B. Stress-induced enhancement of fear conditioning activates the amygdalar cholecystokinin system in a rat model of post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuroreport. 2014;25(14):1085–1090. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0000000000000232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ballaz S., Barber A., Fortuño A., Del Río J., Martin-Martínez M., Gómez-Monterrey I., Herranz R., González-Muñiz R., García-López M.T. Pharmacological evaluation of IQM-95,333, a highly selective CCKA receptor antagonist with anxiolytic-like activity in animal models. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121(4):759–767. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Kawaguchi Y., Kubota Y. GABAergic cell subtypes and their synaptic connections in rat frontal cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 1997;7(6):476–486. doi: 10.1093/cercor/7.6.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Marsicano G., Lutz B. Expression of the cannabinoid receptor CB1 in distinct neuronal subpopulations in the adult mouse forebrain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 1999;11(12):4213–4225. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Beinfeld M.C., Connolly K. Activation of CB1 cannabinoid receptors in rat hippocampal slices inhibits potassium-evoked cholecystokinin release, a possible mechanism contributing to the spatial memory defects produced by cannabinoids. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;301(1):69–71. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)01591-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang Y., Gupta A., Toledo-Rodriguez M., Wu C.Z., Markram H. Anatomical, physiological, molecular and circuit properties of nest basket cells in the developing somatosensory cortex. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12(4):395–410. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.4.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Vereczki V.K., Veres J.M., Müller K., Nagy G.A., Rácz B., Barsy B., Hájos N. Synaptic organization of perisomatic GABAergic inputs onto the principal cells of the mouse basolateral amygdala. Front. Neuroanat. 2016;10:20. doi: 10.3389/fnana.2016.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Eggan S.M., Melchitzky D.S., Sesack S.R., Fish K.N., Lewis D.A. Relationship of cannabinoid CB1 receptor and cholecystokinin immunoreactivity in monkey dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Neuroscience. 2010;169(4):1651–1661. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Neu A., Földy C., Soltesz I. Postsynaptic origin of CB1-dependent tonic inhibition of GABA release at cholecystokinin-positive basket cell to pyramidal cell synapses in the CA1 region of the rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 2007;578(Pt 1):233–247. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.115691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Ali A.B., Todorova M. Asynchronous release of GABA via tonic cannabinoid receptor activation at identified interneuron synapses in rat CA1. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2010;31(7):1196–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Katona I., Sperlágh B., Sík A., Käfalvi A., Vizi E.S., Mackie K., Freund T.F. Presynaptically located CB1 cannabinoid receptors regulate GABA release from axon terminals of specific hippocampal interneurons. J. Neurosci. 1999;19(11):4544–4558. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-11-04544.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lawrence J.J. Homosynaptic and heterosynaptic modes of endocannabinoid action at hippocampal CCK+ basket cell synapses. J. Physiol. 2007;578(Pt 1):3–4. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Antonelli T., Tomasini M.C., Mazza R., Fuxe K., Gaetani S., Cuomo V., Tanganelli S., Ferraro L. Cannabinoid CB1 and cholecystokinin CCK2 receptors modulate, in an opposing way, electrically evoked [3H]GABA efflux from rat cerebral cortex cell cultures: possible relevance for cortical GABA transmission and anxiety. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009;329(2):708–717. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.150649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Yoshida T., Uchigashima M., Yamasaki M., Katona I., Yamazaki M., Sakimura K., Kano M., Yoshioka M., Watanabe M. Unique inhibitory synapse with particularly rich endocannabinoid signaling machinery on pyramidal neurons in basal amygdaloid nucleus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108(7):3059–3064. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012875108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Rovira-Esteban L., Péterfi Z., Vikór A., Máté Z., Szabó G., Hájos N. Morphological and physiological properties of CCK/CB1R-expressing interneurons in the basal amygdala. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017;222(8):3543–3565. doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1417-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Vogel E., Krabbe S., Gründemann J., Wamsteeker Cusulin J.I., Lüthi A. Projection-specific dynamic regulation of inhibition in amygdala micro-circuits. Neuron. 2016;91(3):644–651. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2016.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Barsy B., Szabó G.G., Andrási T., Vikór A., Hájos N. Different output properties of perisomatic region-targeting interneurons in the basal amygdala. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2017;45(4):548–558. doi: 10.1111/ejn.13498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Chhatwal J.P., Gutman A.R., Maguschak K.A., Bowser M.E., Yang Y., Davis M., Ressler K.J. Functional interactions between endocannabinoid and CCK neurotransmitter systems may be critical for extinction learning. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):509–521. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Shen C.J., Zheng D., Li K.X., Yang J.M., Pan H.Q., Yu X.D., Fu J.Y., Zhu Y., Sun Q.X., Tang M.Y., Zhang Y., Sun P., Xie Y., Duan S., Hu H., Li X.M. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors in the amygdalar cholecystokinin glutamatergic afferents to nucleus accumbens modulate depressive-like behavior. Nat. Med. 2019;25(2):337–349. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0299-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Omiya Y., Uchigashima M., Konno K., Yamasaki M., Miyazaki T., Yoshida T., Kusumi I., Watanabe M. VGluT3-expressing CCK-positive basket cells construct invaginating synapses enriched with endocannabinoid signaling proteins in particular cortical and cortex-like amygdaloid regions of mouse brains. J. Neurosci. 2015;35(10):4215–4228. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4681-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Papagianni E.P., Stevenson C.W. Cannabinoid regulation of fear and anxiety: an update. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(6):38. doi: 10.1007/s11920-019-1026-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Bowers M.E., Ressler K.J. Interaction between the cholecystokinin and endogenous cannabinoid systems in cued fear expression and extinction retention. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2015;40(3):688–700. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Vargish G.A., Pelkey K.A., Yuan X., Chittajallu R., Collins D., Fang C., McBain C.J. Persistent inhibitory circuit defects and disrupted social behaviour following in utero exogenous cannabinoid exposure. Mol. Psychiatry. 2017;22(1):56–67. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Bandopadhyay R., de Belleroche J. Regulation of CCK release in cerebral cortex by N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors: sensitivity to APV, MK-801, kynurenate, magnesium and zinc ions. Neuropeptides. 1991;18(3):159–163. doi: 10.1016/0143-4179(91)90108-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Booker S.A., Althof D., Degro C.E., Watanabe M., Kulik Á., Vida I. Differential surface density and modulatory effects of presynaptic GABAB receptors in hippocampal cholecystokinin and parvalbumin basket cells. Brain Struct. Funct. 2017;222(8):3677–3690. doi: 10.1007/s00429-017-1427-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Dugladze T., Maziashvili N., Börgers C., Gurgenidze S., Häussler U., Winkelmann A., Haas C.A., Meier J.C., Vida I., Kopell N.J., Gloveli T. GABA(B) autoreceptor-mediated cell type-specific reduction of inhibition in epileptic mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110(37):15073–15078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1313505110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Jappy D., Valiullina F., Draguhn A., Rozov A. GABABR-dependent long-term depression at hippocampal synapses between CB1-positive interneurons and CA1 pyramidal cells. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2016;10:4. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2016.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Rezayat M., Roohbakhsh A., Zarrindast M.R., Massoudi R., Djahanguiri B. Cholecystokinin and GABA interaction in the dorsal hippocampus of rats in the elevated plus-maze test of anxiety. Physiol. Behav. 2005;84(5):775–782. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Hajizadeh Moghaddam A., Hosseini R.S., Roohbakhsh A. Anxiogenic effect of CCK8s in the ventral hippocampus of rats: possible involvement of GABA(A) receptors. Pharmacol. Rep. 2012;64(1):45–53. doi: 10.1016/S1734-1140(12)70729-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Augier E., Dulman R.S., Damadzic R., Pilling A., Hamilton J.P., Heilig M. The GABAB positive allosteric modulator ADX71441 attenuates alcohol self-administration and relapse to alcohol seeking in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42(9):1789–1799. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Kosaka T., Kosaka K., Tateishi K., Hamaoka Y., Yanaihara N., Wu J.Y., Hama K. GABAergic neurons containing CCK-8-like and/or VIP-like immunoreactivities in the rat hippocampus and dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. 1985;239(4):420–430. doi: 10.1002/cne.902390408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Sloviter R.S., Nilaver G. Immunocytochemical localization of GABA-, cholecystokinin-, vasoactive intestinal polypeptide-, and somatostatin-like immunoreactivity in the area dentata and hippocampus of the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 1987;256(1):42–60. doi: 10.1002/cne.902560105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Francavilla R., Villette V., Luo X., Chamberland S., Muñoz-Pino E., Camiré O., Wagner K., Kis V., Somogyi P., Topolnik L. Connectivity and network state-dependent recruitment of long-range VIP-GABAergic neurons in the mouse hippocampus. Nat. Commun. 2018;9(1):5043. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-07162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Ivanova M., Belcheva S., Belcheva I., Stoyanov Z., Tashev R. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 167.Lee A.T., Cunniff M.M., See J.Z., Wilke S.A., Luongo F.J., Ellwood I.T., Ponnavolu S., Sohal V.S. VIP interneurons contribute to avoidance behavior by regulating information flow across hippocampal-prefrontal networks. Neuron. 2019;102(6):1223–1234.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Zaben M., Sheward W.J., Shtaya A., Abbosh C., Harmar A.J., Pringle A.K., Gray W.P. The neurotransmitter VIP expands the pool of symmetrically dividing postnatal dentate gyrus precursors via VPAC2 receptors or directs them toward a neuronal fate via VPAC1 receptors. Stem Cells. 2009;27(10):2539–2551. doi: 10.1002/stem.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Reisi P., Ghaedamini A.R., Golbidi M., Shabrang M., Arabpoor Z., Rashidi B. Effect of cholecystokinin on learning and memory, neuronal proliferation and apoptosis in the rat hippocampus. Adv. Biomed. Res. 2015;4:227. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.166650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.David D.J., Wang J., Samuels B.A., Rainer Q., David I., Gardier A.M., Hen R. Implications of the functional integration of adult-born hippocampal neurons in anxiety-depression disorders. Neuroscientist. 2010;16(5):578–591. doi: 10.1177/1073858409360281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Ledri M., Sørensen A.T., Erdelyi F., Szabo G., Kokaia M. Tuning afferent synapses of hippocampal interneurons by neuropeptide Y. Hippocampus. 2011;21(2):198–211. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Kim H., Whang W.W., Kim H.T., Pyun K.H., Cho S.Y., Hahm D.H., Lee H.J., Shim I. Expression of neuropeptide Y and cholecystokinin in the rat brain by chronic mild stress. Brain Res. 2003;983(1-2):201–208. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(03)03087-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Heberlein A., Bleich S., Kornhuber J., Hillemacher T. Neuroendocrine pathways in benzodiazepine dependence: new targets for research and therapy. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(3):171–181. doi: 10.1002/hup.911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 174.Bowers M.E., Choi D.C., Ressler K.J. Neuropeptide regulation of fear and anxiety: Implications of cholecystokinin, endogenous opioids, and neuropeptide Y. Physiol. Behav. 2012;107(5):699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2012.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 175.Comeras L.B., Herzog H., Tasan R.O. Neuropeptides at the crossroad of fear and hunger: a special focus on neuropeptide Y. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2019;1455(1):59–80. doi: 10.1111/nyas.14179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 176.Cáceda R., Kinkead B., Nemeroff C.B. Involvement of neuropeptide systems in schizophrenia: human studies. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 2007;78:327–376. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7742(06)78011-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]