Abstract

Background

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by repetitive behaviours, cognitive rigidity/inflexibility, and social-affective impairment. Unfortunately, no gold-standard treatments exist to alleviate the core socio-behavioural impairments of ASD. Meanwhile, the prosocial empathogen/entactogen 3,4-methylene-dioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) is known to enhance sociability and empathy in both humans and animal models of psychological disorders.

Objective

We review the evidence obtained from behavioural tests across the current literature, showing how MDMA can induce prosocial effects in animals and humans, where controlled experiments were able to be performed.

Methods

Six electronic databases were consulted. The search strategy was tailored to each database. Only English-language papers were reviewed. Behaviours not screened in this review may have affected the core ASD behaviours studied. Molecular analogues of MDMA have not been investigated.

Results

We find that the social impairments may potentially be alleviated by postnatal administration of MDMA producing prosocial behaviours in mostly the animal model.

Conclusion

MDMA and/or MDMA-like molecules appear to be an effective pharmacological treatment for the social impairments of autism, at least in animal models. Notably, clinical trials based on MDMA use are now in progress. Nevertheless, larger and more extended clinical studies are warranted to prove the assumption that MDMA and MDMA-like molecules have a role in the management of the social impairments of autism.

Keywords: 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine; animal; autism spectrum disorder; human; MDMA; social behavior

1. INTRODUCTION

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder manifesting in early childhood [1, 2]. It is characterised by a triad of behavioural symptoms. These include social reciprocal communication and interaction impairment, motor stereotypies (repetitive behaviours), and cognitive rigidity. Each symptom appears to different extents in different individuals [1, 2]. They are the outcome of abnormal brain physiology developed as early as in utero [3]. Briefly, they involve both genetic and environmental risk factors, affecting synaptogenesis and axon motility downstream [4]. The amygdala and nucleus accumbens are purportedly involved [4].

ASD symptoms result in variable impacts on functioning across all domains of life [5-7]. 85% of children with ASD report difficulties at school, with 63% of those having social difficulties, and 52% of those having communication difficulties [8]. These difficulties continue into adulthood, with the majority of individuals with ASD being unemployed or underemployed [9], predictably leading to a considerably lower quality of life [10, 11]. The reported prevalence rates of ASD are rising worldwide [12], implicating an impending increase in disease burden, necessitating the need to develop more effective interventions, as well as treatments to support this population. While it remains unclear what is driving this increased prevalence in ASD [13], factors such as changes in reporting [14], increased awareness and changes in diagnostic criteria [15], among other theories [13], may be contributing factors. Nevertheless, it is imperative to develop more effective interventions and treatments to support this population.

There are currently no FDA-approved pharmacological treatments for the core impairments that define ASD [16]. Two medications are currently FDA-approved for the treatment of accessory traits, irritability and aggressiveness, in ASD: aripiprazole and risperidone. These are controversial for use, due to their adverse effects [16, 17].

A significant number of off-label medications have also been utilised, such as alpha-2 agonists, mood stabilisers, norepinephrine-reuptake inhibitors, serotonin-reuptake inhibitors, antipsychotics and opioid-receptor antagonists [18, 19]. The latter have either insufficient evidence of efficacy, or are only able to address different accessory symptoms of ASD, such as irritability and hyperactivity [18, 19]. In addition, addressing ASD comorbidities can be fraught with complexities. This includes the need to obtain prescriptions for these comorbid affective disorders (such as anxiety and depression) or comorbid neurological disorders (such as epilepsy) [20, 21].

No drugs have been approved for the core impairments in ASD [22, 23]. However, several drugs have shown early-stage evidence for the treatment of these core behaviours, such as bumetanide, pregnenolone, suramin, sulforaphane, folinic acid, propranolol, oxytocin, vasopressin antagonists, and arbaclofen [22, 23]. Furthermore, many non-pharmacological treatments for ASD also exist, though these fail to target core behavioural traits, or do not yet have a sufficient evidence base to be recommended for widespread clinical use [24]. Psychotherapeutic methods include applied behaviour analysis [25-27], meditation/mindfulness [28], early-childhood and parent education [29], cognitive behaviour therapy [30], music therapy [31], and social-skills training [32, 33]. However, these interventions represent a significant financial and time burden for the individuals with ASD and their families, and only address the accompanying traits of ASD (e.g. anxiety).

There have been numerous human studies undertaken on MDMA intake and social interaction, though most of them have been uncontrolled [34]. In contrast, animal models provide a controlled means to examine the potential impact of pharmacological treatments [35]. This means that the model chosen must hold an empirical and theoretical relationship to autism. The behaviours must be unambiguous and homologous between species (construct validity), the model must resemble autism in its clinical features (face validity), and the model must correctly predict clinical treatments for autism (predictive validity) [36].

An animal model of human psychiatric disease is a more ethically accepted way of exploring neurological aberrational mechanisms and drug treatments, where those drugs have not been approved for human use [37-39]. Rodents (mice and rats) have most commonly been used to model ASD pre-clinically, due to construct and face validity, as well as convenience of use in the laboratory [40, 41]. ASD can be environmentally or genetically induced in them, and treatments are then provided to assess alleviation of those induced ASD traits via specially tailored behavioural assays [42].

As far as we are aware, this would be the first systematic review of the studies encompassing animal and human behavioural effects of MDMA, which are relevant to ASD. We conclude that the prosocial behaviours induced by MDMA may counteract at least the social impairments in autism, at least based on support from animal models.

1.1. 3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)

MDMA is more commonly appreciated as the intended-for-consumption agent in ‘ecstasy’, and is known to have prosocial effects in humans [43-46]. In fact, historically it was used in psychotherapy since the early 1960s [47]. Specifically, MDMA increases emotional empathy and sociability [43, 45]. We stipulate, therefore, that various studies in animal models (and also in humans) may provide insights as to the role of MDMA in ameliorating the pathological lack of sociability featured in some individuals on the autism spectrum. MDMA rodent studies have indeed demonstrated that MDMA increases prosocial behaviour and decreases asocial behaviour, similar to MDMA’s effects on humans [43]. Moreover, a recent pilot trial on humans was fruitful in finding social anxiolytic effects of MDMA [48].

The prosocial effect of MDMA is considered to be mediated primarily by serotonin and oxytocin [44, 49-52]. The primary mechanism of action of MDMA is to act as a substrate for serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine monoamine transporters, such that their transport is reversed, thereby their respective synapses are saturated [53]. MDMA’s effects on serotonin release seem most relevant to the oxytocin release and prosocial effects [52] because serotoninergic neurons are known to stimulate oxytocin release [54]. MDMA is, however, also a direct agonist at some serotonin receptors. For example, MDMA has a relatively strong affinity for 5-HT1 and 5-HT2 receptors [55], which may also explain its effects on oxytocin and prosocial behaviour, as oxytocin secretion is mediated mostly by 5-HT1A [52, 56], 5-HT2C, and 5-HT4 receptors [56]. In rat models, MDMA activates oxytocinergic neurons in the supraoptic and paraventricular nuclei of the hypothalamus [52]. This induces oxytocin to be synthesised in these areas and released from the posterior pituitary gland into the peripheral blood [56]. Oxytocin, in turn, is likely to decrease amygdala activation and coupling, which normally triggers fear responses, thereby providing a mechanism for reduced social anxiety [57]. This response can vary between individuals, as one study found that variants of the OXTR gene influences the function/structure of oxytocin receptors on the amygdala, thereby modulating downstream impulses to the brainstem to regulate sympathetic and behavioural fear responses [58]. Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the OXTR gene have even been detected in autistic individuals) [59-61], further supporting the hypothesis that ASD may be at least in part an issue of decreased empathy and increased anxiety (via oxytocin effects on the amygdala and downstream) [59-61]. Whilst MDMA has not been tested on autistic brains, MDMA has shown decreased amygdalar activity in healthy brains [62-64]. Autism is dependent on synaptic plasticity, and there is also plenty of evidence that MDMA has effects on synaptic plasticity [65-67]. We direct the reader to an excellent review on the molecular effects of MDMA [68], as going more into detail is beyond the scope of this RCT-focused review.

1.2. Aims/rationale

We aim to show that, throughout the animal and human literature, MDMA has been shown to have prosocial effects at certain doses (subject to mode of administration and timing of dosing). Hence, clinical studies using MDMA to alleviate the social impairment in ASD are warranted to help establish MDMA as a clinically approved drug in ASD patients. Of note, MDMA could be able to manage a core impairment constituting ASD, which has never been directly addressed by an approved drug before. We also aim to investigate the animal and human literature to see whether MDMA has had effects on the other two core impairments in ASD, namely stereotypy and cognitive rigidity. This latter goal could shed light on the dose adjustments required to optimally reduce these other impairments in future human clinical studies, as well as acting on the social impairment we focus on in this review. We refer to both acute and chronic administration. Acute means a singular dose that is administered to the test animal or human, whereas chronic means several doses administered to the test animal or human over time. The exact timings of these doses are specified in the tables, alongside their respective study. Testing itself may occur between or after the chronic doses, and this is also specified for each study.

2. METHODS

2.1. Study Design

A systematic review of the literature exploring how MDMA influences the presentation of ASD-like characteristics, in particular social behaviours, in animals and humans, was conducted. Specifically, these are studies in rodent strains without autism-salient mutations or exposures, and humans without autism, as no preceding papers have tested MDMA in organisms with ASD.

2.2. Search Strategy

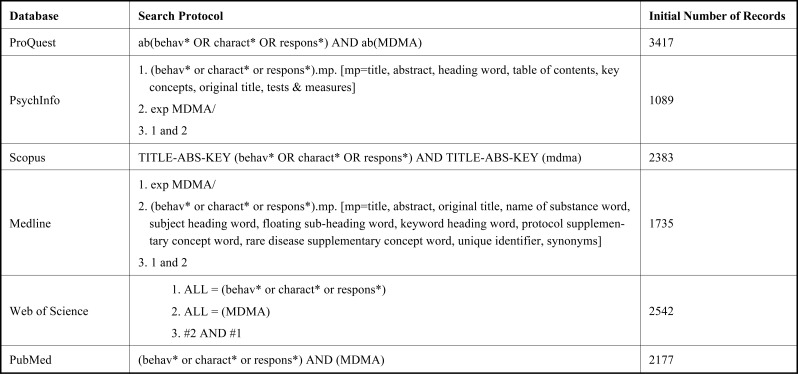

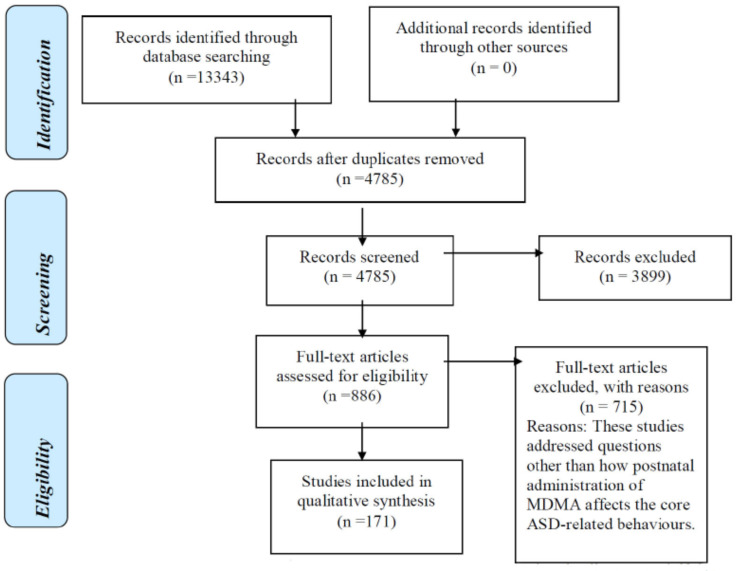

Six electronic databases including ProQuest, PsychInfo, Scopus, Medline, Web of Science and PubMed (search cut-off date: 21/05/20 inclusive) were consulted. The search strategy, tailored to each database, is detailed in Fig. (2). Only English-language studies were used. The study process is outlined via the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, illustrated in Fig. (1).

Fig. (2).

Search strategy, in each database, for both animal and human studies pertaining to the effects of MDMA on ASD-related behaviour.

Fig. (1).

The study numbers used in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines used for this study, for the animal behavioural tests.

2.3. Study Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review identifies literature examining the effects of postnatal MDMA administrations on the core behaviours affected in ASD, in rats and mice, other animals and humans. This includes MDMA treatment at any age past birth. These include social impairment, repetitive behaviour and cognitive rigidity [1, 2]. These diagnostic criteria are taken from DSM-5 and ICD-11, the current gold-standard reference texts for psychological disorders [1, 2] . To this end, the following behavioural tests have been included for rodents: 1) ultrasonic-vocalisation; 2) social-preference; 3) social-novelty-preference; 4) social-interaction; 5) open-field; 6) T/Y-maze; 7) marble-burying; and 8) novel-object-recognition. This review places no limits on age, species or cognitive abilities of the subjects. The inclusion criteria were behaviours core to ASD, behavioural experiments on animals, the use of MDMA to affect the behavioural results, and placebo-controlled studies. The exclusion criteria were applied to papers that only assessed the accessory behaviours to ASD and behaviours not related to ASD, drug self-administration or reinforcement studies, prenatal MDMA administration, or behaviours associated with disorders other than ASD (including Rett syndrome), drugs other than MDMA, uncontrolled studies, and serotonin syndrome. With rodents, approximately 3573 studies were screened, and 127 studies finally reviewed. With other animals, approximately 3456 studies were screened, and 16 studies finally reviewed. With humans, approximately 6205 studies were screened, and 49 studies finally reviewed. “Healthy” human subjects refer to non-autistic patients, whether MDMA-experienced or -naïve, and whether diagnosed with other psychological conditions or not. All were given singular or chronic MDMA doses.

2.4. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.4.1. Rodent and Non-rodent Animals

From animal studies, the data extracted were as follows: species and sex tested, sample size, dosage timing and frequency, dosage mass and route, treatment and testing ages, ambient temperature (as temperature was shown to influence behavioural outcomes with MDMA) [69], and results of the experimental animals as compared to the control group. The findings are summarised in Tables 1-9. In this review, dosage routes have been categorised as singular (only one dose for the subjects) and chronic (multiple doses for a subject). It is worth noting that some papers use the term, “sub-chronic”, to indicate multiple doses. Initial extraction of the data revealed that MDMA generally serves to increase intra-species sociable behaviours in rodents.

2.4.2. Humans

From human studies, the data extracted were as follows: the method of recruitment of the participants, the population type the participants were selected from, number of participants, sex ratio, mean age of the participants, the oral dose of MDMA administered (this was the only administration route used in humans), timing of doses administered, the time between MDMA intake and the first core-ASD-relevant measurement made, the relevant tests undertaken, the relevant results obtained, and the exact parameters taken into account for each relevant test. The findings are summarised in Tables 10 and 11. Initial extraction of the data revealed that MDMA generally serves to increase social behaviour and altruistic feelings in humans.

2.4.3. Interspecies Focus

We take an inter-species perspective in investigating these behavioural effects of MDMA, in the form of a systematic literature review. This is because it is our intention to attempt to translate laboratory-controlled animal studies to their potential impact in humans, where such rigorous techniques cannot be trialled in humans directly [70].

3. RESULTS

Below, we summarise the general trends of behavioural effect that MDMA has had on animals and humans in the laboratory (placebo-controlled) experiments. Where we state “chronic” doses, these are doses delivered more than once. The timings of these dosages are specified for each study in the tables below. The act of repetitive grooming, whether self- or allo-grooming, is classed as repetitive behaviour in these studies, both by the respective study authors and ourselves, but we consider them also as possible signs of cognitive rigidity.

3.1. Core ASD Behaviour 1: Social Impairment

3.1.1. Rodents

There are 4 major tests, currently in the literature, testing social and communication behaviour among mice and rats of different strains. These are the ultrasonic-vocalisation test, the social-preference test, the social-novelty-preference test and the social-interaction test [71-73]. We have also included a novel-object-recognition test here, to see whether the behavioural effects seen in the social-novelty-preference test are dependent on social or general novelty. In the studies reviewed, a “conspecific” will be mentioned, which is a member of the same species (in these cases, a mouse or rat). Below, we summarise each of these tests along with the MDMA-induced alterations on the respective induced social impairments in rodents.

Each study is shown alongside the species, sex and sample size of the rodents tested (control and relevant treatment groups), whether the study used singular or chronic (multiple) dosing, and if they used chronic dosing, the timing of the doses; the dose and route (mode of injection) used, the ages the rodents were treated and tested at, the temperature of the testing environment, and the results obtained from the experiment in the treated rodents (where it is different from the results in the corresponding control rodents). s.c. = subcutaneous mode of injection.

Each study is shown alongside the species, sex and sample size of the rodents tested (control and relevant treatment groups), whether the study used singular or chronic (multiple) dosing, and if they used chronic dosing, the timing of the doses; the dose and route (mode of injection) used, the ages the rodents were treated and tested at, the temperature of the testing environment, and the results obtained from the experiment in the treated rodents (where it is different from the results in the corresponding control rodents). The studies used singular dosing. i.p. = intraperitoneal mode of injection.

Each study is shown alongside the species, sex and sample size of the rodents tested (control and relevant treatment groups), whether the study used singular or chronic (multiple) dosing, and since they used chronic dosing, the timing of the doses; the dose and route (mode of injection) used, the ages the rodents were treated and tested at, the temperature of the testing environment, and the results obtained from the experiment in the treated rodents (where it is different from the results in the corresponding control rodents). i.p. = intraperitoneal mode of injection.

3.1.1.1. Ultrasonic-vocalisation Tests

The ultrasonic-vocalisation test is performed prior to weaning of the pup, and is a measure of the pup’s ultrasonic vocalisation (USV) ability in response to being separated from its mother [74]. It is believed that the purpose of these distress calls is to induce the mother to retrieve the pup back to its home litter [75]. The normal USV emission by maternally separated rodents is shown to be increased in the rate of calls on PD 6-12, which persists till PD 15 and then declines [76]. Teratogenic agents administered in utero may result in deviations from this pattern as well as the sounds therein. In ASD rodents, MDMA caused the abnormal calls to return to having the normal decrease and subsequent increase in call rate that is observed in healthy rodents within a day [76].

We found one study where MDMA was given post-natally, and the pups were measured for vocalisation ability upon maternal separation (Table 1). The study shows that when 10 mg/kg MDMA is injected subcutaneously singularly to pups pre-weaning, call frequency (the number of calls emitted) decreases initially, then increases later within a day [76]. When the same is given multiple times at an earlier age, later ages show decreased frequency in proportion to dose [76].

Table 1.

Ultrasonic vocalisations (upon maternal separation) from postnatally MDMA-treated rodents, compared with control rodents.

| Study | Species | Sexes | Sexes Combined or Separated | Sample Size |

Singular/

Chronic Dosing |

Chronic Timing | Dose (mg/kg) | Route | Treatment Age (PD) | Testing Age (PD) | Temperature (°C) | Males | Females | Both | No. Pups per Mother |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winslow 1990 [76] | Rat | Both | Combined | 42 | Singular | NA | 0.5-10 | s.c. | 9-11 | 9-11 | 24 | NA | NA | Decreased rate of pup calls, increased locomotion. 10 mg/kg: call frequency decreased at 0.5 and 3 hours post-injection, increased at 10 and 24 hours post-injection. | 9-12 |

| Winslow 1990 [76] | Rat | Both | Combined | 36 | Chronic | 7 injections in total | 10 | s.c. | 1-4 | 6, 9, 12, 15 | 24 | NA | NA | PD 9-15: dose-dependent long-lasting decreased call rate |

9-12 |

3.1.1.2. Social-preference Tests

The social-preference test assesses a rodent’s preference to spend time with a conspecific vs. an inanimate object. Thus, the apparatus for the test consists of three chambers: a “home base” and two flanking chambers containing either a caged unknown sex- and age-matched conspecific or an “object”. Control rodents usually spend more time in and make more entries into, the chamber with the caged conspecific than the chamber with the empty cage, indicating social preference. Studies directly take this as a social-preference index, being the ratio of time spent in the conspecific chamber over either the time spent in the object chamber or the total time spent in all chambers. We found three studies where 3-15 mg/kg MDMA, given once intra-peritoneally approximately on PD 56-84, acutely increased rodent social preference (Table 2).

Table 2.

Social preferences in postnatally MDMA-treated rodents, compared with control rodents.

| Study | Species | Sexes | Sexes Combined or Separated | Sample Size | Singular/Chronic Dosing | Chronic Timing | Dose (mg/kg) | Route | Treatment Age (PD) | Testing Age (PD) | Temperature (°C) | Males | Females | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heifets 2019 [187] | Mouse | Both | NA | 36-80 | Singular | NA | 3, 7.5, 15 | i.p. | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7.5 and 15 mg/kg: dose-dependently increased |

| Kuteykin-Teplyakov 2014 [188] | Mouse | Males | NA | 59 | Singular | NA | 2, 3, 4, 6 | i.p. | 56-84 | 56-84 | 21 | 3 mg/kg: increased | NA | NA |

| Ramos 2016 [189] | Rat | Males | NA | 64 | Singular | NA | 2.5, 5 | i.p. | “Adult” (250-300g) | “Adult” (250-300g) | 21 | Well-handled, 5 mg/kg: increased. Minimally handled, 5 mg/kg: no effect. 2.5 mg/kg: no effect. | NA | NA |

3.1.1.3. Social-novelty-preference Tests

The social-novelty-preference test assesses a rodent’s preference to spend time with an unfamiliar conspecific over a familiar conspecific. The test uses the same set-up as the social-preference test, but the object (empty cage) is replaced by a new sex- and age-matched conspecific (the unfamiliar). The familiar is the previously encountered conspecific in the opposite flanking chamber. Studies directly take this as a social-novelty-preference index, being the ratio of time spent in the unfamiliar chamber over either the time spent in the familiar chamber or the total time spent in all chambers. We found one study where 5 or 10 mg/kg MDMA, given chronically intraperitoneally on PD 28-52, increased mouse social-novelty preference when tested later on PD 120 (Table 3). This therefore, also shows a long-lasting prosocial effect of the MDMA, which would increase the value of MDMA as a treatment.

Table 3.

Social-novelty preferences in postnatally MDMA-treated rodents, compared with control rodents.

| Study | Species | Sexes |

Sexes

Combined or Separated |

Sample Size |

Singular/

Chronic Dosing |

Chronic Timing |

Dose

(mg/kg) |

Route |

Treatment

Age (PD) |

Testing

Age (PD) |

Tempera-

ture (°C) |

Males | Females | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morley-Fletcher 2002 [190] | Mouse | Both | Separated | NA | Chronic | Once on each of 3 days, 2 days apart for each |

5, 10 | i.p. | 28, 38, 52 | 120 | 21 | Increased | Increased | NA |

3.1.1.4. Novel-object-recognition Tests

The novel-object-recognition test assesses novelty preference and memory for a new object replacing an existing familiar object. We have classed this in the “social impairment” tests in order to compare with the “social-novelty preference” tests. In control rodents, the norm is to spend more time with the unfamiliar than the familiar object, indicating a natural curiosity to explore the unexplored, and is indicative of an intact representation that the existing environment has changed.

We found 33 studies where MDMA was given mostly chronically postnatally, and the rodent offspring were measured for their tendency to spend more time exploring the unfamiliar/novel object than the familiar (Table 4). The studies show that giving mostly chronic 5-10 mg/kg MDMA, intraperitoneally or subcutaneously, actually exacerbates this loss in the rodent’s exploratory discrimination between the two objects, which is in contrast to our expected effect on social impairment (see social-novelty-preference test). This may confirm that if there is disinterest in both social and non-social novelty, this may indicate cognitive rigidity as opposed to social impairment, because MDMA appears to exacerbate cognitive rigidity (see below). Interestingly, one study shows that a higher temperature (28°C) exacerbates this supposed memory deficit more than a cooler temperature (16oC) [77].

Table 4.

Novel-object preferences in postnatally MDMA-treated rodents, compared with control rodents.

| Study | Species | Sexes |

Sexes Combined

or Separated |

Sample Size |

Singular/

Chronic Dosing |

Chronic Timing | Dose (mg/kg) | Route | Treatment Age (PD) | Testing Age (PD) | Temperature (°C) | Males | Females | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abad 2014 [191] | Rat | Males | NA | 14-18 | Chronic | Twice daily for 4 days | 20 | s.c. | 35 | 7 days after treatment ended | 26 | No effect | NA | NA |

| Abad 2016 [192] | Rat | Males | NA | 14-18 | Chronic | 3 times a day, every 3 hours, once a week for 2 weeks | 5 | NA | 28-49 | 28-49 | 26 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Abad 2016 [192] | Rat | Males | NA | 14-18 | Chronic | 3 times a day, every 3 hours, once a week for 2 weeks for another 3 weeks | 7.5 | NA | 49-70 | 49-70 | 26 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Abad 2016 [192] | Rat | Males | NA | 14-18 | Chronic | 3 times a day, every 3 hours, once a week for 2 weeks for another 3 weeks | 10 | NA | 70-91 | 70-91 | 26 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Able 2006 [193] | Rat | Males | NA | 40 | Chronic | Once every 2 hours, for 4 doses on 1 day | 15 | s.c. | 225-250g | 5 days later | 22 | No effect | NA | NA |

| Adeniyi 2016 [194] | Mouse | Males | NA | 10 | Chronic | 5 times over 10 days, at 2-day intervals | 2 | s.c. | 21 | 31, 32 | NA | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Bubenikova-Valesova 2010 [195] | Rat | Males | NA | NA | Chronic | 4 days | 2.5, 5 | s.c. | NA | NA | NA | No effect | NA | NA |

| Clemens 2007 [136] | Rat | Females | NA | 16 | Chronic | 1 injection per week, for 16 weeks | 8 | i.p. | 238g | 120 days later | 28 | NA | No effect | NA |

| Cohen 2005 [196] | Rat | Males | NA | 30 | Chronic | Twice a day (8 hours apart) | 20 | s.c. | 11-20 | 40-49 | 21 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Cohen 2005 [196] | Rat | Males | NA | 30 | Chronic | 4 times, at 2 intervals | 15 | s.c. | 82-100 | 131-129 | 21 | No effect | NA | NA |

| Edut 2011 [197] | Mouse | Males | NA | 34 | Singular | NA | 10 | i.p. | 25-30g | “Juvenile” | 23 | No effect | NA | NA |

| Edut 2014 [198] | Mouse | Males | NA | 18-26 | Singular | NA | 10 | i.p. | 25-30g | 7, 30 days later | 23 | No effect | NA | NA |

| García-Pardo 2017 [94] | Mouse | Males | NA | 45 | Singular | NA | 5, 10 | i.p. | 42 | 63, 64 | 35-37 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Llorente-Berzal 2013 [199] | Rat | Both | Separated | 55 | Chronic | Every 5 days, twice daily (4 hours apart) | 10 | s.c. | 30-45 | 75 | 22 | No effect | No effect | NA |

| Ludwig 2008 [200] | Rat | Males | NA | 39+ | Singular | Single injection | 5 | s.c. | “Adult” (242-275g) | 7 days later | NA | No effect | NA | NA |

| Ludwig 2008 [200] | Rat | Males | NA | 39+ | Chronic | 5 daily injections | 5 | s.c. | “Adult” (242-275g) | 7 days later | NA | No effect. Multiple doses: increased | NA | NA |

| Study | Species | Sexes |

Sexes Combined

or Separated |

Sample Size |

Singular/

Chronic Dosing |

Chronic Timing | Dose (mg/kg) | Route | Treatment Age (PD) | Testing Age (PD) | Temperature (°C) | Males | Females | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ludwig 2008 [200] | Rat | Males | NA | 39+ | Both | Chronic, then single | 5 | s.c. | “Adult” (242-275g) | 7 days later | NA | Multiple doses: increased | NA | NA |

| McGregor 2003 [77] | Rat | Males | NA | 32 | Chronic | 2 consecutive days, every hour for 4 hours | 5 | i.p. | 60-75 | 70-84 days later | 28, 16 | 28°C: reduced | NA | NA |

| Meyer 2008 [201] | Rat | Males | NA | NA | Chronic | 2 doses, 4 hours apart | 10 | s.c. | 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 | 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60 | 22-23 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Nawata 2010 [202] | Mouse | Males | NA | 10-30 | Singular | NA | 10 | i.p. | 30-35g | 30-35g | 23 | No effect | NA | NA |

| Nawata 2010 [202] | Mouse | Males | NA | 10-30 | Chronic | Once daily for 7 days | 10 | i.p. | 30-35g | 30-35g | 23 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Piper 2004 [203] | Rat | Males | NA | 16 | Chronic | On every 5th day, twice daily, intervals of 4 hours | 10 | s.c. | 35-60 | 65 | 22 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Piper 2005 [204] | Rat | Males | NA | 20 | Chronic | Hourly intervals over 4 hours, once every 5 days | 5 | s.c. | 35-60 | 67, 68, 69 | 22 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Piper 2008 [205] | Rat | Males | NA | 20-24 | Chronic | 4 doses, 1 each hour | 10 | s.c. | Young adult (307.7g) | Young adult | 23 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Rodsiri 2011 [206] | Rat | Males | NA | 21-24 | Chronic | Every 2 hours over 6 hours (3 injections) | 3, 6 | i.p. | 100-130g | 14 days later | 21 | 3 × 6 mg/kg: reduced. 6 mg/kg: no effect | NA | NA |

| Ros-Simo 2013 [207] | Mouse | Males | NA | 20-24 | Chronic | Twice, 6 hours apart | 20 | i.p. | 25 | 28 | 22 | Reduced, long-term | NA | NA |

| Schulz 2013 [208] | Rat | Males | NA | 24 | Chronic | Once daily for 10 days, twice daily (4 hours apart) for 5 days | 7.5 | s.c. | “Adult” (230-300g) | 40-65, 80-105 | 22 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Shortall 2012 [209] | Rat | Both | Combined | 16 | Chronic | Once daily for 7 days | 5 | i.p. | 170-205g | 7 days later | NA | NA | NA | No effect |

| Shortall 2013 [210] | Rat | Males | NA | 12-16 | Chronic | 2 consecutive days a week, for 3 weeks | 10 | i.p. | Young adult | Young adult | 21 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Skelton 2008 [211] | Rat | Males | NA | 63 | Chronic | 4 per day (2 hours apart), 1 day per week, 5 weeks (1-week intervals) | 15 | s.c. | 225-250g | 35-39 days later | 22 | No effect | NA | NA |

| van Nieuwenhuijzen 2010 [212] | Rat | Males | NA | 24 | Chronic | Daily over 10 days | 5 | i.p. | 220-300g | 220-300g | 21 | Reduced | NA | NA |

| Vorhees 2007 [213] | Rat | Both | Separated | 160 | Chronic | Every 2 hours, each day | 40 once a day, 20 twice a day, or 10 four times a day | s.c. | 11-20 | 64-68 | 21 | No effect | No effect | NA |

| Vorhees 2009 [214] | Rat | Both | Separated | NA | Chronic | 4 doses, every 2 hours each day | 10, 15, 20, 25 | s.c. | 1-20 | 60 | 21 | No effect | No effect | NA |

3.1.1.5. Social-interaction Tests

The social-interaction test is a simple and direct test of social interaction. The test rodent and a conspecific of the same treatment group are placed in an open arena and their behaviour monitored. Different behavioural acts are measured, and specialist terms are listed in Table 5.1.

We found 59 studies where MDMA was given singularly or chronically postnatally, and the rodents observed for their inter-conspecific social interactions (Table 5). The studies show that singular doses of 5-10 mg/kg MDMA, given intraperitoneally, increases prosocial behaviour and decreases asocial behaviour. Interestingly, at these same doses, chronic dosing has the opposite effect: decreasing prosocial behaviour and increasing asocial behaviour (Table 5). One study was an exception to this [78], where 5-20 mg/kg MDMA given twice daily over 3 days actually increased the duration of social investigation. On either side of the dosage window, 5-10 mg/kg MDMA, this opposite effect is also seen: decreased prosocial behaviour and increased asocial behaviour (Table 5).

Table 5.

Social-interaction behaviours in postnatally MDMA-treated rodents, compared with control rodents.

| Study | Species | Sexes | Sexes Combined or Separated | Sample Size |

Singular/

Chronic Dosing |

Chronic Timing | Dose (mg/kg) | Route | Treatment Age (PD) | Testing Age (PD) | Temperature (°C) | Social Restriction | Males | Females | Both |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ando 2006 [87] | Rat | Males | NA | 34 | Either | 1 or 2 days (49 days apart) | 15 | i.p. | 49-56 | 49-56 | 21 | Nil | Decreased regular total social-interaction time, locomotion, self-grooming, rearing. Increased adjacent-lying time (more than social-interaction decrease). | NA | NA |

| Ando 2006 [87] | Rat | Males | NA | 34 | Either | 1 or 2 days (49 days apart) | 15 | i.p. | 49-56 | 70-77 | 21 | Nil | 3 weeks later, dosed on 1st day: increased aggression, rearing and line crossings. Acute, dosed on 2nd day: increased total time of social behaviour (adjacent lying), total number of non-social activities and line crossings. |

NA | NA |

| Ando 2010 [215] | Rat | Males | NA | 24 | Singular | NA | 15, 30 | i.p. | 42-49 | 222-229 | 21 | Nil | Fewer line crossings. No change in duration or number of social interactions, aggressive behaviours. | NA | NA |

| Bull 2003 [133] | Rat | Males | NA | 24 | Chronic | Twice daily | 15 | i.p. | 28-30 | 50 | 21 | Nil | Reduced total social interaction. | NA | NA |

| Bull 2003 [216] | Rat | Both | NA | NA | Chronic | Four times daily, for 2 consecutive days | 5 | i.p. | 28 | 84 | NA | Nil | After 54 days' abstinence, social interaction decreased by 27% | NA | NA |

| Bull 2004 [132] | Rat | Males | NA | 32 | Chronic | Each of 4 hours | 5 | i.p. | 28 | 84 | 21 | Nil | Increased social anxiety, decreased total social interaction. | NA | NA |

| Cagiano 2008 [84] | Rat | Males | NA | 90 | Singular | NA | 0.3, 1, 3 | i.p. | “Adult” | “Adult” | 20-22 | Nil | 3 mg/kg: increased time till intromission and ejaculation, decreased copulatory activity. | NA | NA |

| Clemens 2004 [217] | Rat | Males | NA | 24-30 | Chronic | 4 injections in 1 day, 2 hours apart | 2.5, 5 | i.p. | 376g | 28 days later | 28 | Nil | Increased total locomotor activity. 5 mg/kg: reduced social-interaction time. | NA | NA |

| Clemens 2005 [218] | Rat | Females | NA | 16-18 | Chronic | Every 2 hours in 1 day, 4 times | 4 | i.p. | 281g | 42 days later | 28 | Nil | NA | Less social interaction. | NA |

| Clemens 2007 [136] | Rat | Females | NA | 32 | Chronic | 1 injection per week for 16 weeks | 8 | i.p. | 238g | 49 days later | 28 | Nil | NA | Decreased total social-interaction time. | NA |

| Clemens 2007 [136] | Rat | Females | NA | 16 | Chronic | 1 injection per week for 16 weeks | 8 | i.p. | 238g | 113 days later | 28 | Nil | NA | Reduced social-interaction time. | NA |

Interestingly, one study saw a difference in MDMA’s effects on aggressive vs. timid mice: whilst MDMA increased timidity in both types of mice, MDMA increased social behaviour in aggressive mice, and decreased social behaviour in timid mice [79]. Timidity was determined in a preliminary interaction test where mice would be defined as “timid” if they showed no attack, but significant defensive-escape behavior, even in the absence of partner aggression, when placed in a neutral arena with a conspecific [79]. If timidity is a factor in influencing sociability, this finding would make sense, since excessively timid mice would not be inclined to socialise, and aggressive mice without tempering with timidity would not be inclined to socialise. However, timid rats were more likely to become aggressive when a young intruder is introduced into the cage, when given MDMA chronically at 6 mg/kg [80].

Each study is shown alongside the species, sex and sample size of the rodents tested (control and relevant treatment groups), whether the study used singular or chronic (multiple) dosing, and if they used chronic dosing, the timing of the doses; the dose and route (mode of injection) used, the ages the rodents were treated and tested at, the temperature of the testing environment, and the results obtained from the experiment in the treated rodents (where it is different from the results in the corresponding control rodents). i.p. = intraperitoneal mode of injection; s.c. = subcutaneous mode of injection.

Each study is shown alongside the species, sex and sample size of the rodents tested (control and relevant treatment groups), whether the study used singular or chronic (multiple) dosing, and if they used chronic dosing, the timing of the doses; the dose and route (mode of injection) used, the ages the rodents were treated and tested at, the temperature of the testing environment, the duration of social restriction (isolation) enforced before testing, and the results obtained from the experiment in the treated rodents (where it is different from the results in the corresponding control rodents). i.p. = intraperitoneal mode of injection; s.c. = subcutaneous mode of injection.

There have also been temperature, inter-sex-interaction and group effects seen. Similar to human studies with MDMA, a study found that the higher temperature increased social interaction more than the lower temperature [69]. In fact, some studies deliberately increased the testing temperature to 28oC, in order to amplify these social effects [81-83]. Only one study investigated inter-sex interactions, and found that singular 3 mg/kg MDMA decreased the inclination to copulate [84], similar to the doses below 5 mg/kg MDMA, which decreased prosocial behaviour. A study also found that group-housed mice became more physically active, more so than single-housed mice, when given MDMA; and that social interaction duration was increased in the group-housed and not the single-housed group [85]. This is similar to human studies where prosocial effects of MDMA appear enhanced when taken in groups of people [86].

Some interesting effects are noted as follows: one study found a difference between acute and chronic effects of MDMA: when tested on the same day, prosocial behaviour was increased in MDMA-treated rats; when tested 3 weeks later, asocial behaviour was increased a day later, but when dosed again, it acutely increased prosocial behaviour [87]. One study’s singular 8 mg/kg dose caused decreased social exploration [88], another study’s singular 5-10 mg/kg dose also decreased social exploration [89], and another’s singular 5 mg/kg increased asocial behaviours [90]. Notably, these studies socially isolated their animals for 30 days prior to testing, to increase aggressive behaviour [88-90]. Perhaps, in these cases, MDMA’s effects could not entirely overcome that increased aggressive behaviour. Some studies had a significant time delay between testing and treating: 65, 70 and 21 days [91-93], with surprising results of decreased prosocial behaviour [91-93] and increased asocial behavior [93]. One study used social defeat as a variable to influence social interaction, where they used 30 mins. of isolating the test rodent before testing, to induce aggression during testing [94]. Three other studies gave surprising results: social and prosocial behaviours were decreased when MDMA was given at a singular 5-10 mg/kg [95-97].

To summarise the social behavioural tests in rodents, USV calls increased gradually in emission rate when 10 mg/kg MDMA is given singularly or chronically postnatally (Table 1). Rodents’ preference to spend time with a conspecific over an object, or an unfamiliar conspecific over a familiar, increases when given 5-10 mg/kg MDMA singularly or chronically postnatally (Tables 2, 3). Social behavioural results are mixed between the studies, when 5-10 mg/kg MDMA is given singularly or chronically postnatally (Table 5). The literature also shows reports of chronic effects, whereby MDMA-treated rodents retain these prosocial effects (Tables 3, 4, 5).

3.1.2 Other Animals

Most of the non-rodent animal studies focused on social behaviour after MDMA treatment. Since dosage effects are different between species, we will observe each animal model in turn. Four studies tested the behavioural effects of MDMA on monkeys [98-101]. They found that chronic administration of 1.5 mg/kg s.c. [98], or singular dose of 0.03-3 mg/kg i.m. [100] increased prosocial behaviour. Interestingly, Pitts et al. (2017) showed that with lower doses, it was the S(+) MDMA enantiomer that increased this gregariousness more, and at higher doses, the R(−) MDMA enantiomer increased affiliative behaviour more. Chronic 1.5 mg/kg (p.o. and especially i.m.) increased vigilance, indicating perhaps decreased social trust [101]. But the studies also found that chronic 12 mg/kg p.o. decreased vocalisations [99], and that both 12 mg/kg p.o. and 20 mg/kg i.g. [102] induced serotonin behaviour, indicating this range was an unnecessarily high dose.

Four studies examined ASD-specific behaviour in MDMA-treated fish, in particular social behaviour [103-106]. They found that when 1 or 5 mg/kg MDMA was singularly intramuscularly injected into electric fish, asocial behaviour decreased and prosocial behaviour increased [103]. Interestingly, in zebrafish, singularly immersing the animals in 80 mg/L actually increased the distance between adjacent fish and shortened the duration spent near each other [104]. This may be explained by the fact that in one study, which tested for general anxiety in zebrafish, immersing the animals in 0.25-120 mg/L increased the chance of the fish entering and dwelling at the top of the fish tank [107], indicating reduced anxiety. This is because fish tend to become anxious towards the water’s surface as there is a greater risk of predation there [108, 109], and shoaling behaviour is generally a result of alarm pheromones dissipated among the fish [104, 110]. Ponzoni et al. (2016, 2017) found that a singular intramuscular injection of 0.1-10 mg/kg MDMA increased social preference [105, 106]. Two studies looked at social behaviour in singularly MDMA-immersed octopodes [111, 112]. They found that when octopodes were doused in 0.5-0.005 mg/kg MDMA solution, not only did social preference increase [111, 112], but so did voluntary body contact between the animals [112].

3.1.3 Humans

The human studies tested MDMA effects on non-autistic subjects, except for one study which looked specifically at the effects of MDMA on social anxiety in autistic adults [48]. In this study, autism was diagnosed if the subject fulfilled Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders- Fourth Edition Axis I Research Version (SCID-I-RV) or Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS-2 Module 4) criteria. The assessments in all studies were between subjects, where one group were given MDMA and the other placebo. Most studies assessed mostly chronically given 1.5 mg/kg (often by an absolute dose of 100 mg) which may increase the likelihood of finding positive results. We assume a linear positive relationship (gradient: 1.5 mg/kg per 100 mg; intersect: 0 mg/kg = 0 mg) between mg/kg and mg, and convert absolute doses to per kg of participant body weight accordingly. Each study had its own method of measuring social outcomes, therefore classifying into types of tests (as able to be done for the rodent model) would be inaccurate. Specific details of these tests are therefore listed in the tables for each respective study.

As shown in Table 10, all doses increased prosocial behaviour. This includes mostly self-perceptions of extroversion, openness, sociability, talkativeness, thoughtfulness or caring, sensitivity, friendliness, insightfulness of others, gregariousness or desire to be with others, empathy, lovingness, playfulness, closeness to others. Interestingly, social interaction increased more at 0.5 mg/kg than 1 mg/kg in one study [86], and playfulness and lovingness increased more at 1.5 than 0.75 mg/kg (chronic dosing).

Table 10.

Social behaviour in postnatally MDMA-treated subjects, compared with placebo-treated subjects.

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baggott 2016 [284] | Newspaper, online adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, MDMA-experienced | 12 | 6 female, 6 male | 29 | 1.5 mg/kg | Singular | 1.5 hours | Self-reports of social anxiety and interpersonal functioning | Decreased social anxiety; increased affiliative (nurturance/communion) feelings | Apprehension towards being judged; dominance/agency and nurturance/communion | ||||||||

| Baggott 2015 [285] | Newspaper, community bulletin board, online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, Caucasian | 35 | 12 female, 23 male | 24.3 | 1.5 mg/kg | Singular | 4 hours | Verbal recounts of significant others and own emotions | Increased words with social/sexual content. No sex differences. Increased words with factual, decreased words with psychological, content about target person. No changes in phrases referring to relationship to target person, decreased words relating to body of target person and increased words related to cognition and insight | Names of 3 personally important people, altered use of words, discussion topics, number of words spoken, isolated descriptions of target person, proportion and number of phrases describing relationship to target person, words relating to target person's body vs. cognition and insight, drug-related emotions (including social); words with social, negative and positive valence | ||||||||

| Bajger 2015 [286] | Word of mouth, online and newspaper adverts, poster flyers | Black, Hispanic, white | 12 | 3 female, 9 male | 28.9 | 50, 100 mg (~0.75, 1.5 mg/kg) | Twice daily over 5 days | 60 mins. | Self-reports of affect | Repeated dose: increased gregariousness, decreased preference for solitude, 100 mg: increased time spent verbally communicating with others | Private and social (talking and silence) time, mood, preference for solitude or gregariousness, effects of singular vs. repeated doses | ||||||||

| Bedi 2014 [287] | Adverts | Healthy, ecstasy-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 13 | 4 female, 9 male | 24.5 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | Singular | Mood: 65 mins.; speech: 130 mins. | Verbal recounts of significant others | 1.5 mg/kg: words had increased proximity to “friend”, “support”, “intimacy”, “rapport”. 0.75 mg/kg: words had increased proximity to “empathy” | Degrees of “compassion”, “empathy”, “forgive”, “friend”, “intimacy”, “love”, “rapport”, “support”, “talk”, “confident” | ||||||||

| Bedi 2010 [288] | Internet adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, ecstasy-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 21 | 9 female, 12 male | 24.4 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 4 times, 5/+-day intervals | Mood: 0; emotion recognition: 65 mins. | Self-reports of mood, emotion-recognition tasks | 1.5 mg/kg: increased ratings of “loving”, “friendly”, “playfulness”, decreased accuracy of facial fear recognition in others, increased likelihood of misclassifying emotional expressions as neutral. 0.75 mg/kg: increased ratings of “loneliness” | Moods: “Sociable”, “Playful”, “Loving”, “Lonely”. Friendliness: “‘friendly”, “agreeable”, “helpful”, “forgiving”, “good-natured”, “warm-hearted”, “good-tempered”, “kindly”. Facial cues: anger, fear, happiness, sadness Vocal tones: happy, sad, angry, fearful; with high/low emotional intensities |

||||||||

| Bedi 2009 [64] | Online adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, right-handed, ecstasy-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 9 | 2 female, 7 male | 24 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 6/+-day intervals, doses in ascending order | Mood: 0; emotion recognition: 45 mins. | Mood, facial emotion recognition | Increased ratings of sociability, no effect on accuracy of emotion recognition | Moods: sociability and friendliness. Facial emotion recognition (happy, neutral, angry, fearful) for “pleasant”, “neutral”, “unpleasant” | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| Bershad 2017 [289] | Newspaper, bulletin board, online adverts | Healthy, ecstasy-experienced | 39 | 9 female, 30 male | 24.1 | 0.5, 1 mg/kg | Twice (same dose), 7 days apart | 60 mins. | Self-reports of moods, public-speaking task | 1 mg/kg: increased stress, tension, insecurity. 0.5, 1 mg/kg: increased perceptions of public speaking being challenging and threatening | Self-ratings of stress, tension, insecurity; stressfulness and challenge of public speaking | ||||||||

| Bershad 2016 [290] | Flyers, online adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, Caucasian, occasional MDMA users | 68 | 29 female, 39 male | 23.8 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 5/+-day intervals | 30 mins. | Self-reports of mood | Increased sociability | Degrees of “lonely”, “sociable,” “loving,” “playful,” “friendly”, “confident” | ||||||||

| Bershad 2019 [291] | University campus and surrounds | Healthy, MDMA-experienced | 36 | 18 female, 18 male | 24.8 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions, 2/+ days apart | 30 mins. | Subjective ratings of mood states and touch stimuli, psychophysiological responses, visual attention to emotional faces | Increased feelings of being “insightful”, “playful”; dose-dependently increased ratings of pleasantness of experienced affective touch; 1.5mg/kg: MDMA increased total number of times participants looked toward happy faces; increased zygomatic activity (smiling when looking at others affectively touching) |

“Sociable,” “Confident,” “Lonely,” “Playful,” “Loving,” “Friendly,” and ‘Restless”; “pleasantness” upon being physically touched or observation of physical touching between others; activity of zygomatic (smiling) and corrugator (frowning) muscles; eye movements for attention bias | ||||||||

| Cami 2000 [292] | Word of mouth | MDMA-experienced, healthy, mostly smokers | 8 | Male | 26.5 | 75, 125 mg (~ 1.1, 1.9 mg/kg) | 4 sessions, 1/+-week intervals | 1 hour | Mood states | No effect on friendliness | Self-ratings of friendliness | ||||||||

| Clark 2015 [148] | Flyers, posters, word of mouth | Mostly Caucasian | 33 | 16 female, 17 male | 24.5 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | Singular | 30 mins. | Subjective drug effects | Increased prosocial feelings of “loving” and “insightful” | Self-ratings of “playful,” “loving”, “insightful” | ||||||||

| Corey 2016 [114] | Psychotherapy patients | Caucasian, PTSD patients | 20 | 18 female, 5 male | 40.5 | 125 mg (~1.9 mg/kg), 62.5 mg/kg | 1-3 times | Large dose, then smaller dose after 2 hours | Talk sessions | Increased ensuic, empathic, entactic utterances | Utterances where patients initiated empathic, entactic or ensuic topics | ||||||||

| Danforth 2018 [48] | Internet adverts, word of mouth, clinician referrals | Healthy, MDMA-naïve | 12 | 16.7% female (all MDMA), 83.3% male | 31.3 | 75, 100, 125 mg (~ 1.1, 1.5, 1.9 mg/kg) | Twice, 1-month interval | 1 day | Social anxiety | Decreased social anxiety, also at 6-month follow-up | Change from baseline, of social anxiety scores, over time | ||||||||

| de Wit 2011 [293] | Online adverts, word of mouth | MDMA-experienced polydrug users, mostly Caucasian smokers | 9 | 2 female, 7 male | 24 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | Ascending order, 6 days apart | 0 | Mood states, emotion recognition | 1.5 mg/kg: increased sociability (and insignificant trend towards friendliness). No effect on emotion-recognition time or accuracy | Sociability and friendliness, emotion-recognition time and accuracy | ||||||||

| Dolder 2018 [294] | University | Mostly MDMA-naïve | 24 | 12 female, 12 male | 22.6 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) | 4 sessions, 7/+-day intervals | Mood 0; emotion recognition: 2.5 hours | Mood states, facial emotion recognition | Increased “happiness”, “open”, “trust”, “feeling close to others”, “I want to be with other people”, “I want to hug someone”, “well-being”, “emotional | “Happy,” “concentration,” “open,” “trust,” “feeling close to others,” “I want to be with other people,” “I want to hug someone”, | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | excitation”, “extraversion”, “introversion”, impaired recognition of fearful faces, increased misclassification of emotions as happy, increased sexual measures - “tingly all over,” “sensitive to touch,” “enthusiastic,” “warm all over,” “flushed,” “heart beats faster,” “seductive”, “enthusiastic,” “warm all over,” “passionate,” “sensual,” “pleasure,” “heart beats faster,” “happy,” “powerful,” “forget about all else”, “anticipatory” | sexual - “tempted”, “passionate”, “seductive”, “attractive”, “sensitive to touch”, “stimulated”, “excited”, “heart beats faster”, “anxious”, “displeasure”, “repulsion”, “angry”, “driven”, “urge to satisfy”, “horny”, “impatient”. Accuracy for degrees of happiness, sadness, anger, and fear facial expressions, misclassification of expressions as neutral | ||||||||

| Dumont 2009 [44] | Internet and drug-testing service adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced | 14 | 3 female, 12 male | 21.1 | 100 mg (~1.5 mg/kg) | 7-day interval | 0 | Subjective amicability and gregariousness | Subjective amicability were positively correlated with MDMA concentrations, but subjective gregariousness was not. (NB: Both subjective amicability and subjective gregariousness were positively correlated with oxytocin concentrations; measures had stronger correlations with oxytocin than MDMA). | Measures of antagonistic/amicable, withdrawn/gregarious | ||||||||

| Frye 2014 [145] | Flyers, online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 36 | 18 female, 18 male | 24.6 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 96/+-hour intervals | Mood: 30 mins.; social rejection: 2.75 hours | Mood effects, reactions to social-rejection simulation, correct perceptions of social-exclusion manipulations | Increased “loving” (before and after social-rejection paradigm). Reduced decreasing effect of rejection on mood and self-esteem. Increased perceived percentage of inclusive throws under rejection condition | Self-ratings of ‘Insightful’, ‘Sociable’, ‘Confident’, ‘Lonely’, ‘Playful’, ‘Loving’, and ‘Friendly’, special emphasis on ‘Loving’. Reactions to social rejection: “I felt sad”, “I felt somewhat inadequate during the game”, “I felt like an outsider during the game”, with recollection of number of ball throws (social inclusions) received | ||||||||

| Gabay 2018 [146] | Community | MDMA-experienced | 20 | Male | 24.8 | 100 mg (~ 1.5 mg/kg) | 2 sessions, 1/+ weeks apart | 95 mins. | Preferences of resource distribution amongst others, social-reward measures | Lower probability of rejecting unfair offers in the first-person condition, but not the third-party condition. Increased average percentage offer, prosocial interaction | Preference measures: “unfair” (selfish), “fair” (equal), “hyper-fair” (altruistic) offers. Social-reward measures: admiration, negative social potency, passivity, prosocial interactions, sexual relationships, sociability. | ||||||||

| Gabay 2019 [147] | Community | MDMA-experienced | 20 | Male | 24.8 | 100 mg (~ 1.5 mg/kg) | 2 sessions, 1/+ weeks apart | 95 mins. | Mood states, Prisoner's Dilemma (cooperation vs. | Reduced accuracy in identifying fear and anger. Increased cooperation on the second run of the Prisoner's Dilemma. | Social decision-making and changes in trust (during social interaction), facial emotion recognition (happy, sad, fear, or anger - with intensities; identifying and degree of empathising with emotion) | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | betrayal, when forced to choose), emotion recognition, cognitive and affective empathy | Increased probability of a cooperative decision with trustworthy opponent, but not untrustworthy opponent or game server (neutral). Increased proportion of participants continuing to cooperate after first decision to compete by opponent. Maintained overall level of cooperation (declined with placebo) | |||||||||

| Harris 2002 [295] | NA | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, Caucasian | 8 | 3 female, 5 male | 24-39 | 0.5, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 7/+days apart | 30 mins. | Mood states | 1.5 mg/kg: increased yes responses to “Have you had a greater feeling of love for others?” and “Have you liked having people around more?”, insignificant trend towards increased “friendly” self-ratings and “closeness to others” |

Degrees of Closeness to Others, Energetic, Talkative, Friendly, Confident, Insightful, Anxious. “Have you had a greater feeling of love for others?” and “Have you liked having people around more?” |

||||||||

| Holze 2020 [296] | University campus | Healthy, over-25-year-olds | 28 | 14 females, 14 males | 28 | 125 mg | Singular | 30 mins. | Mood states | Increased prosocial feelings of “talkative”, “open”, “extraversion”, and general positive feelings of “well-being”, “blissful state”, “positive mood”, “ineffability” | “Talkative”, “open”, “ego dissolution” | ||||||||

| Hysek 2012 [51] | University campus | Healthy, mostly MDMA-naïve | 48 | 24 female, 24 male | 26 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) | 3 sessions, 10/+ days apart | Eye-reading: 90 mins.; mood: 0 | Identifying emotions/thoughts from eye regions of others; mood states | Increased accuracy in reading positive emotions from the eye region, decreased accuracy in reading negative. No change in neutral emotions or total score. Increased “closeness,” “open,” and “talkative” mood self-reports | Total number of correct discriminations of eye-reading test; subscores computed for positive, negative, neutral emotional valences. Prosocial effects: degrees of “closeness to others,” “open,” and “talkative.” | ||||||||

| Hysek 2014 [45] | University campus | Healthy, mostly MDMA-naïve | 32 | 16 female, 16 male | 25 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) | 10/+ days apart | Empathy test: 3 hours | Mood states, cognitive and emotional empathy, interpersonal reactivity, social value orientation, facial affect recognition | Increased self-ratings of “happy”, “open” and “close to others”, implicit and explicit emotional empathy for positive emotions in men only, increased empathy and prosocial behaviour in men to become comparable to that in women. | Prosociality: ‘happy’, ‘open’, ‘close to others’, inferring mental states (cognitive empathy) degree to which participant felt for individual in picture (explicit emotional empathy), and degree to which participant was aroused by the scene (implicit empathy), trait empathy, social behaviour by resource allocation (degree of maximising allocation for other person) with inequality aversion and joint gain maximisation, accuracy in identifying emotions from facial expressions | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | Increased prosociality in men but not women (resource allocation). Promoted shift from joint gain maximization to inequality aversion. Impaired accuracy of emotion recognition, especially in women (insignificant in men), impaired recognition of fearful, angry, disgusted and surprised faces. Impaired recognition accuracy for fearful, angry and sad faces, only in women. Increased detection threshold for fearful faces | |||||||||

| Hysek 2012 [297] | NA | Healthy, ecstasy-naïve | 16 | 8 female, 8 male | 26.1 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) |

10/+ days apart | 0 | Mood states | Increased “open,” “closer to others,” and more “talkative”, “extroversion” | Degrees of “closeness to others,” “talkative,” and “open”, “extroversion” and “introversion” | ||||||||

| Kirkpatrick 2015 [46] | Newspaper, community bulletin board, online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 32 | 9 female, 23 male, mostly Caucasian | 24.9 | 0.5, 1 mg/kg |

3 sessions, 5/+ days apart | 60 mins. | Generosity towards stranger | 1.0 mg/kg: increased generosity toward friend, but not stranger. 0.5 mg/kg: increased generosity toward a stranger, in females | Point at which participant switches from decision to monetarily benefit selves vs. others | ||||||||

| Kirkpatrick 2014 [298] | Different institutes | Healthy, mostly MDMA-experienced | 220 | 44% female, 66% male | 25.4 | 1.5 mg/kg, 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) |

NA | NA | Mood states | Increased closeness to others | Degrees of “closeness to others” | ||||||||

| Kirkpatrick 2015 [86] | Posters, print, internet adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, MDMA-experienced | 33 | 9 female, 24 male | Early 20s | 0.5, 1 mg/kg |

3 sessions | 1.5 mins. | Mood states, social interaction, perceptions of others and selves | Increased social interaction (mostly by talking), especially 0.5 mg/kg. 1 mg/kg: rated another as more socially attractive | Degrees of prosocial effects (“confident,” “friendly,” “insightful,” “loving,” “lonely,” “playful,” “sociable”). Proportion of 1.5 min intervals interacting or talking. Level of erceived social attractiveness and physical attractiveness of another person. Level of attention, interest, understanding, and empathy of another person, participant's own level of responsiveness toward another. Perception of their own levels of social affiliation and social power or status. | ||||||||

| Kirkpatrick 2012 [299] | Word of mouth, newspaper and online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, mostly polydrug users | 11 | 2 female, 9 male | 29.3 | 100 mg (~1.5 mg/kg) | 4 sessions, 2 days' washout period | 7.5 hours | Video recordings of social interaction, with 2 films played | No effect on social interaction | Private (time spent in bathroom/bedroom) and social (time spent in the recreational area). Social time: time spent talking and time spent in silence. Total minutes spent engaging in each behavior per day. | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| Kirkpatrick 2014 [300] | Newspaper, community bulletin board, online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, Caucasian | 65 | 25 female, 40 male | 23.8 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions, 5/+ days apart | 25 mins. | Mood states, social and emotional processing | Increased “friendly” (dose-dependently) and “lonely”. 1.5 mg/kg: reduced accuracy in identifying angry and fearful faces. Increased likelihood rating socialising as more desirable | Prosocial effects (‘Confident,' ‘Friendly,' ‘Insightful,' ‘Loving', ‘Lonely,' ‘Playful,' ‘Sociable'). Accuracy of identifying facial expressions of anger, fear, happiness, sadness. Perceived degrees of attractiveness, friendliness, and trustworthiness of facial pictures. Desire to engage in chatting with another, solving word probems or sitting quietly alone | ||||||||

| Kolbrich 2008 [301] | TV, radio, newspaper adverts, flyers, word of mouth | MDMA-experienced, mostly African-Americans | 8 | 2 females, 6 males | 21.1 | 1, 1.6 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 7 days between sessions | 0 | Mood states | Insignificantly increased feelings of closeness to others | Degrees of feelings of closeness to others | ||||||||

| Kuypers 2018 [153] | University and website adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, MDMA-experienced polydrug users | 20 | 8 female, 12 male | 21.2 | 75 mg (~1.1 mg/kg) | 7-day washouts | 90 mins. | Mood states; processing of affective sounds (recorded from strangers); approach-avoidance behaviour to social, threat and trust stimuli | Equally aroused by positive and negative sounds (controls: negative sounds produced more arousal), insignificant avoidance bias to threat faces, insignificant approach bias to trust faces; increased friendliness | Friendliness scale; sounds of happy, sad, fear, disgust, anger; joystick manipulation to indicate approach/avoidance | ||||||||

| Kuypers 2014 [154] | University and website adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, MDMA-experienced polydrug users | 20 | NA | 18-26 | 75 mg (~1.1 mg/kg) | 4 sessions, 7-day washouts | 1 hour, 25 mins. | Empathy: reading emotions from eye region, cognitive and emotional empathy, interpersonal reactivity. Social interaction: trust, social ball-tossing. Mood states | More concerned and more aroused by the emotional content of the pictures | Empathy: identifying emotions as “negative”, “positive”, “neutral”; identifying emotion, rating how concerned (explicit emotional empathy) and aroused (implicit emotional empathy) for the person; tendency to imaginatively transpose oneself into fictional social situations, tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological viewpoint of others, feelings of warmth, compassion and concern for others, self-oriented feelings of anxiety and discomfort resulting from tense interpersonal settings. Social interaction: inferring mental state and choosing to cooperate, social reciprocation. Mood state: friendliness scale |

||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| Kuypers 2017 [155] | NA | Healthy | 118 | 55 female, 63 male | 21.2-25.75 | 75, 125 mg (~ 1.1, 1.9 mg/kg) | 7/+-day washouts | 120 mins. | Cognitive, implict and explicit emotional empathy; interpersonal reactivity | More concern (especially for positive stimuli) and arousal (for both positive and negative (as opposed to just positive, as in controls) stimuli) for people depicting emotions | Inferring emotional state, rating how aroused/concerned they felt for the other person; tendency to imaginatively transpose oneself into fictional social situations, tendency to spontaneously adopt the psychological viewpoint of others, feelings of warmth, compassion and concern for others, self-oriented feelings of anxiety and discomfort resulting from tense interpersonal settings. | ||||||||

| Kuypers 2008 [302] | Newspaper adverts, snowballing | Polydrug users, MDMA-experienced, healthy | 14 | 7 female, 7 male | 22.93 | 50, 75 mg (~ 0.75, 1.1 mg/kg) | 7/+-day washouts | 30 mins. | Mood states | Increased friendliness | Friendliness scale | ||||||||

| Liechti 2000 [303] | University hospital, medical school | Healthy, mostly unversity students and physicians | 16 | 4 female, 12 male | 27.4 | 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions, 14/+-day intervals | 120 mins. | Mood states | Increased “self-confidence”, “extroversion”, “introversion” | Scales of “extroversion”, “introversion”, “aggression-anger”, “self-confidence” | ||||||||

| Liechti 2001 [115] | University hospital staff, medical school | Healthy, mostly unversity students and physicians, mostly MDMA-naive | 74 | 20 female, 54 male | 27 | 10, 50 mg (~0.2, 0.75 mg/kg) | 2 sessions, 2/+-week interval | 30 mins. | Mood and consciousness states | Increased “comprehensive love”, self-confidence, extroversion, openness, sociability, talkativeness. Increased thoughtfulness and sensitivity in women | Self-confidence, extroversion, introversion, aggression-anger, thoughtfulness, sensitivity. Changes in mood, perception, experience of the self and of the environment | ||||||||

| Liechti 2000 [149] | University hospital, medical school | Healthy, mostly MDMA-naïve | 14 | 1 female, 13 male | 26 | 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions, 10/+-day intervals | 75 mins. | Mood states | Decreased vigilance; increased self-confidence, sensitivity and extroversion | Self-confidence, extroversion, introversion, aggression-anger, vigilance | ||||||||

| Liechti 2000 [304] | University hospital, medical school | Healthy, mostly unversity students and physicians, mostly MDMA-naïve, mostly non-smokers | 14 | 5 female, 9 male | 26 | 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions, 10/+-day intervals | 75 mins. | Mood states | Increased extroversion and sociability | Introversion, extroversion, sociability | ||||||||

| Liechti 2001 [55] | University hospital, medical school | Mostly university students or physicians, healthy, mostly MDMA-naïve | 44 | 10 female, 34 male | 26, 27 | 1.5 mg/kg | 4 sessions | 120 mins. | Mood states | Increased self-confidence, extraversion | Self-confidence, extroversion, introversion, sensitivity, aggression/anger | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| Schmid 2014 [150] | University | Mostly MDMA-naïve, healthy | 30 | 15 female, 15 male | 24 | 75 mg (~ 1.1 mg/kg) | 7/+-day intervals | Emotion recognition: 75 mins.; mood: 90 mins.; moral judgement: 2 hours; cognitive and emotional empathy: 3 hours; prosociality: 4 hours; mood: 0, 1.25, 5 hours | Facial emotion recognition; cognitive (also in social scenarios) and emotional empathy; prosociality; social decision-making (moral judgement); mood states | Impaired identification of sad, angry and fearful faces; increased misclassification of emotions as neutral; increased both explicit and implicit emotional empathy scores for positive emotional stimuli; increased openness, trust and closeness |

Identifying and misclassifying happiness, sadness, anger and fear; inferring mental state of another, how concerned (explicit emotional empathy) they were for them, how aroused (implicit emotional empathy) they were by the scene; identifying false belief, persuasion, faux pas, metaphor and sarcasm in social contexts; maximising resources for self and others, minimising difference between the two; judging between utilitarian outcomes involving aversive effects to others | ||||||||

| Schmid 2018 [305] | Adverts, word of mouth | Healthy | 24 | 12 female, 12 male | 22.6 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) | 4 sessions, 7/+-day intervals | Mood: 75 mins.; emotion recognition: 150 mins. | Negative emotional states, facial emotion recognition, fearful-face processing | Trend for impaired facial emotion recognition | Emotion recognition: happiness, sadness, anger, fear | ||||||||

| Tancer 2007 [306] | NA | MDMA-experienced, healthy, Caucasian, polydrug users | 8 | 2 female, 6 male | 23.9 | 1.5 mg/kg | 6 sessions, 2/+-day intervals | 60 mins. | Mood states | Increased friendly, talkative scores | Friendliness scale; friendly, self-conscious, social, talkative scales | ||||||||

| Tancer 2003 [113] | NA | MDMA-experienced, mostly smokers, mostly marijuana users | 12 | 6 female, 6 male | 22.3 | 1, 2 mg/kg | 7/+-day intervals | 60 mins. | Mood states | 2 mg/kg: increased friendly, social, talkative scores | Friendliness scale; friendly, self-conscious, social, talkative scales | ||||||||

| Tancer 2001 [307] | NA | MDMA-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 22 | 14 female, 8 male | 23.6 | 1.1-2.1 mg/kg | 2 sessions, 7/+ days apart | 60 mins. | Mood states | Increased friendly score | Friendly scale | ||||||||

| van Wel 2012 [127] | Newpaper adverts, word of mouth | Healthy, MDMA-experienced | 17 | 8 female, 9 male | 22.76 | 75 mg (~ 1.1 mg/kg) | 7/+ days apart | 1.5 hours | Mood states | Increased friendliness | Friendliness score | ||||||||

| Vizeli 2018 [156] | University campus | Healthy, Caucasian, mostly non-drug users | 124 | 64 female, 60 male | 24.8 | 125 mg (~ 1.9 mg/kg) | 7/+ days apart | Mood: 0; emotion recognition, empathy: 90 mins. | Mood states, facial emotion recognition, cognitive and emotional empathy | Increased closeness to others, talkativeness, trust, wanting to be hugged and to hug; impaired recognition of fearful, sad, angry faces; decreased cognitive empathy for all emotions, increased explicit emotional empathy for positive emotions | Mood scales: “closeness to others,” trust,” “want to be hugged,” “want to hug,”“want to be alone,” “want to be with others”, “talkative”. Facial expressions: happiness, sadness, anger, and fear. Empathy: cognitive (inferring mental state of another), implicit emotional (arousal by another's emotional state), explicit emotional (concern for another) | ||||||||

| Study | Recruitment | Population Sampled | No. Participants | Sexes | Mean Ages (years) | Oral MDMA Dose | Dosage Timing | Time till First Test (after baseline) | Relevant Tests | Relevant Results | Relevant Parameters Tested | ||||||||

| Vollenweider 2005 [123] | University hospital staff, medical school | Healthy, mostly MDMA-naïve | 42 | 10 female, 32 male | 25.4-27 | 1.5 mg/kg | NA | 45 mins. | Mood states | Increased self-confidence and extroversion | Self-confidence, extroversion, introversion | ||||||||

| Wardle 2014 [116] | Flyers, online adverts | Healthy, MDMA-experienced, mostly Caucasian | 36 | 18 female, 18 male | 24.6 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 sessions, 7/+ days apart | Mood: 30 mins. Emotion recognition: 70 mins. Conversation: 2 hrs., 20 mins. | Mood states, facial emotion recognition; interpersonal perception | Mood: increased loving, insignificantly increased playful. Emotion recognition: 1.5 mg/kg: impaired recognition of angry expression; decreased frown response to happy expressions, only in females; increased smile response to happy expressions. Increased positive emotion words (both doses). 1.5 mg/kg: insignificantly increased perceived regard, increased empathy, insignificantly increased percepton of empathy from others | Mood: playful, loving, lonely. Emotion recognition: angry, fearful, sad, happy faces. Interpersonal perception: picked 3 personally important people; percentage of positive and negative emotion words to describe each person; participant's perceptions of investigator and scales of regard (“S/he was truly interested in me”), empathy (e.g., “S/he understood me”), and congruence (“I felt that s/he was real and genuine with me”) | ||||||||

| Wardle 2014 [308] | Flyers, online adverts | MDMA-experienced, healthy, mostly Caucasian | 101 | 43 female, 58 male | 24.1 | 0.75, 1.5 mg/kg | 3 or 4, separated by 5/+ days | Mood: 30 mins. Picture ratings: 1 hr., 10 mins. | Mood states, responses to emotional pictures, identifying emotional facial expressions | Dose-dependently increased playfulness, lovingness. 1.5 mg/kg: increased positivity of positive social pictures; 0.75 mg/kg: decreased the positivity of positive non-social pictures (1.5 mg/kg insignificantly had this effect) | Mood: playful’ and ‘loving’. Pictures: social vs. non-social, yielding participant-rated scores on scales of positive/negative and arousal | ||||||||

Between 0.2 and 0.75 mg/kg, recognition of emotions from others’ facial expressions is unaffected. A dose of 1.5 mg/kg and above shows impaired recognition of negative emotions and a tendency to misclassify emotional expressions as neutral or happy (although the studies using 2 and 2.1 mg/kg did not test for facial emotion recognition). 1.9 mg/kg shows increased accuracy in identifying positive emotions (chronic or singular dosing). Likewise, relevant tests show social anxiety increased at 0.5-1 mg/kg, but decreased at 1.1-1.9 mg/kg (including higher self-confidence) (chronic or singular dosing). At a chronic 2 mg/kg, however, one study showed self-consciousness not being affected [113], but this was a self-rating component as part of a wider questionnaire as opposed to a behavioural activity testing for social anxiety. This suggests that perhaps 0.75-1.5 mg/kg MDMA taken orally and chronically may be best to alleviate social impairments in humans, without impairing emotion recognition in others.

There was insufficient variation in age between the studies, to assess age effects. All studies tested young adults in their 20s-30s, with the exception of Corey et al. (2016) whose mean participant age was 40.5 years old. Here, they also chronically used the unusual dose of 62.5 mg/kg [114]. Therefore, the effects of MDMA found in these participants are difficult to attribute a certain cause to, although the common theme of increased empathic utterances continues at this dose.