Abstract

Huntington’s disease (HD) is an autosomal fatal genetic disease in which degeneration of neuronal cells occurs in the central nervous system (CNS). Commonly used therapeutics are cludemonoamine depletors, antipsychotics, antidepressants, and tranquilizers. However, these drugs cannot prevent the psychotic, cognitive, and behavioral dysfunctions associated with HD. In addition to this, their chronic use is limited by their long-term side effects. Herbal drugs offer a plausible alternative to this and have shown substantial therapeutic effects against HD. Moreover, their safety profile is better in terms of side effects. However, due to limited drug solubility and permeability to reach the target site, herbal drugs have not been able to reach the stage of clinical exploration. In recent years, the paradigm of research has been shifted towards the development of herbal drugs based nanoformulations that can enhance their bioavailability and blood-brain barrier permeability. The present review covers the pathophysiology of HD, available biomarkers, phytomedicines explored against HD, ongoing clinical trials on herbal drugs exclusively for treating HD and their nanocarriers, along with their potential neuroprotective effects.

Keywords: Huntington's disorder, oxidative stress, herbal medicine, neuroprotective effects, blood-brain barrier, nanocarriers

1. INTRODUCTION

The term HD was coined by Ohio based physician George Huntington in 1872, who described this disease for the first time [1]. HD is an autosomal fatal genetic disorder which is a progressive, genetically programmed ND that leads to depletion of psychological, cognitive, and motor functions. As per Huntington’s disease Society of America (HDSA), HD patients show symptoms similar to those of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson’s disease (PD), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [2-7]. The symptoms associated with HD are “chorea” (abnormal autonomic movements), loss of rational abilities, and psychological disturbances. This abnormality occurs due to the mutation of the Huntingtin genes. Healthy neurons contain 6-35 repeats of units of cytosine-adenine-guanine (CAG) trinucleotide, while accumulation of mutant Huntingtin (mHTT) genes changes the translation process (more than 36 CAG repeats) [8, 9]. This process may lead to neuronal cell death andcause degeneration of neurotransmitters within the central nervous system (CNS) [10]. After the first appearance of symptoms in an affected person, death usually occurs within 15 to 20 years [11]. Various biochemical alterations such as downregulation of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and acetylcholine (ACh), along with a decrease in their production enzymes, glutamate decarboxylase (GAD) and choline-acetyl transferase (CAT), respectively are seen in patients with HD [11-13].

Globally, 5 to 8 people in a population of 0.1 million are diagnosed with HD [14, 15]. The disease is reported to be more prevalent in Europe as compared to that in the USA, China, and India. A number of patients diagnosed with HD are extrapolated to increase from 58,176 in 2019 to 60,743 in 2024 [14].

2. ETIOPATHOGENESIS

2.1. Neuropsychiatric Disturbance

There is a broad range of HD neuropsychiatric symptoms, involving irritation, obsessive- compulsive behavior, depression, psychosis, and apathy. Prior to the knowledge of HD, this disease was categorized under psychiatric disorder because its symptoms were similar to psychiatric diseases. Later on, based on mechanistic studies, it was understood that the pathology of HD is associated with neurodegeneration in the brain [16, 17]. Irritation, depression, and apathy are neuropsychiatric symptoms that continuously manifest and get advanced with the progress of the disease [18].

2.2. Neurodegeneration

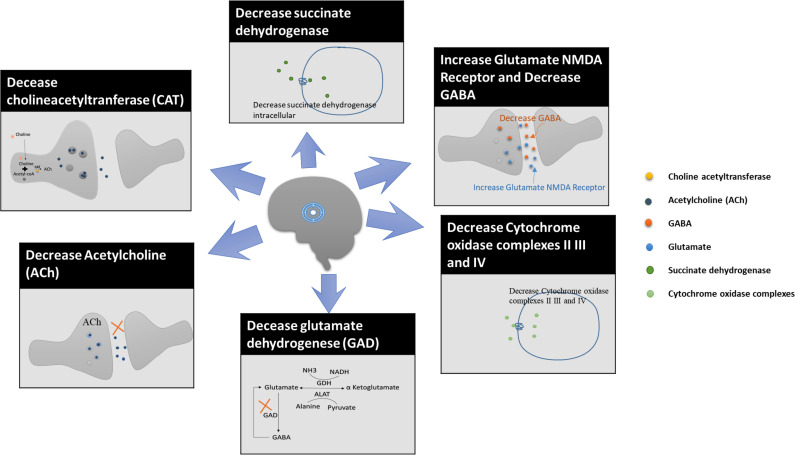

NDs can be classified by extrapyramidal and pyramidal motor disturbances that can lead to cognitive or behavioral changes in the body [19]. Neurodegeneration is a process that involves the degeneration of neurons due to aging of the brain or the influence of pathological factors that can damage the neurons. It has been seen that the loss of neurons in the brain is one of the significant health hazards. Cerebral malfunctioning occurs due to various NDs like AD, PD, HD, ALS, and multiple sclerosis [20-22]. Moreover, activation of excitatory neurotransmitters receptors such as N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid (AMPA) is also a leading cause of excitotoxicity and apoptosis of the neurons. These excitatory receptors can lead to excitotoxicity as observed in chronic NDs such as PD and HD. AMPA and NMDA receptors limit the neuronal entry of calcium ions by regulating calcium ions-permeability in the brain and CNS [23]. The factors that can cause degeneration of neurons are shown in Fig. (1).

Fig. (1).

Factors that cause degeneration of neurons in HD. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

2.3. Genetic Factors

mHTT genes work at the molecular level of cells. They are located in chromosome 4p16.3, 67 exons, and 3144 amino acids. Healthy human genes contain 5 to 35 CAG triplet genes in rRNA exons. mHTTs protein causes a genetic mutation in cells and changes the translation process. Hence, CAG repeat increases from 36 to 121. A number of repeats of CAG depend on the age of onset of the disease [24-26].

2.4. Mitochondrial Dysfunction

Mitochondria play a crucial role in storing maximal bioenergy, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) in the body (eukaryotic cells). They regulate intracellular calcium homeostasis, which can lead to diminishment in the production of free radicals in the endoplasmic reticulum and reduces the apoptosis process. Indeed, mitochondrial dysfunction has been affected by an earlier pathological manifestation of HD. In HD, an increase in the level of polyglutamate occurs in the striatum and cerebral cortex parts of the brain. The mHTT protein is known to cause mitochondrial dysfunction in Huntington’s patients. This mHTT protein binds with mitochondrial transporter II receptors and causes oxidative damage as well as mitochondrial dysfunction. The dysfunction of mitochondria results in lower intake of glucose metabolism and mitochondrial oxidation in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which has been clearly seen in post-mortem reports of brains of HD’s patients [27-30]. It also increases lactate levels in both the CSF and cerebral cortical tissue [31, 32]. Deregulation of mitochondrial function by 3-nitropropionic acid (3-NP) mitochondrial toxin has been observed in various studies in which metabolic impairment occurred due to deficiency of energy, excitotoxicity, and oxidative stress (OS) [33-36].

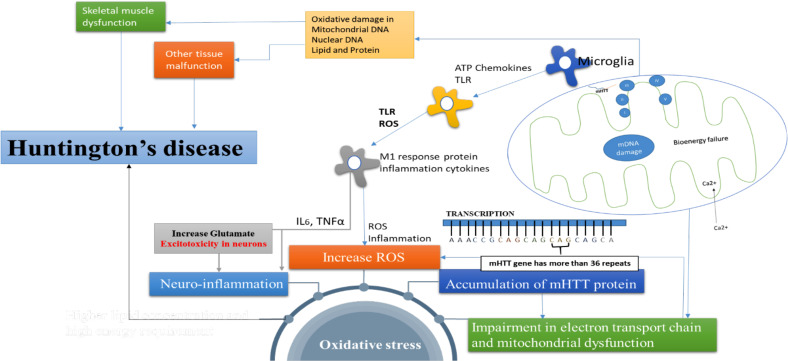

2.5. Oxidative Stress (OS)

The mechanism of OS in HD is still not clear. Some molecular hypotheses state that increase in the level of ROS, lipid peroxidation, and chromosomal mutation can be major factors for disease manifestation [37, 38]. Impairment in the electron transport chain, oxidative damage, and mitochondrial dysfunction can increase OS. 8-Hydroxy-2-deoxygonosine (OH8dG) is a biomarker of oxidative damage in DNA. As reported by Bogdanovet et al. (2001), the enhanced concentration of OH8dG may increase oxidative damage [39]. Accumulation of mHTT protein has been observed in HD’s patients; hence, it may be implicated in the increase of OS [40, 41]. Increased concentrations of free radicals can predispose to excitotoxicity that can cause impairment of the mitochondrial functions, energy production, and metabolic inhibition [42, 43]. These mechanisms of OS are presented in Fig. (2).

Fig. (2).

Pathophysiological mediators that are responsible for OS and HD. Mitochondrial dysfunction: Mitochondria are widely known as the powerhouse of cells as they generate energy in the form of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). mHTT genes bind with transporter II in mitochondria and cause mDNA damage and bioenergy failure. mHTT proteins increase the influx of Ca2+ in cytoplasm in mitochondria which leads to excitotoxicity and bioenergy failure, and ATP formation reduces. As a result of this, mitochondrial dysfunction and the generation of ROS take place. Neuro-inflammation: Microglia and astrocytes in the presence of ATP chemokines activate Toll-like receptor (TLR) and m1 receptor protein inflammation cytokines, which, in turn, increase the intracellular Ca2+ entry and ROS levels. M1 receptor protein inflammation cytokines also increase inflammatory mediators (IL6, TNFα) and OS, which give rise to neuroinflammation and degeneration of the neuronal cell. Accumulation of mHTT genes: The normal base DNA pair contains 5-35 repeated units of CAG chain in exon 1 cytoplasm. When alteration in base DNA pair occurs, mHTT genes bind with exon 1 and increase the CAG units from 36 to 121, which is responsible for OS. This leads to the misfolding of mHtt and the formation of their aggregates in neuronal nuclei and neuropils in the brains of HD patients. This misfolded mHtt exerts its neurotoxicity by disturbing a wide range of cellular functions due to its interaction with a variety of proteins, thus interrupting their function [44]. Increase ROS: Due to mHTT gene, the intracellular influx of Ca2+ increases. This process can enhance excitotoxicity and cause oxidative damage and OS. OS: The factors like accumulation of mHTT genes, neuroinflammation, high lipid concentration, and mitochondrial dysfunction can increase OS, and that is responsible for the progression of the disease. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

3. BIOMARKERS INVOLVED IN THE PATHO-GENESIS

Biomarkers play an important role in evaluating and measuring pathogenic as well as biological processes and pharmacological responses against HD. The ideal biomarker must be reliable, accurate, and specific. For understanding new clinical strategies, understanding the biomarkers of a disease is very important. In order to assess the treatment response and monitor the progression of the disease, the Unified Huntington's Disease Rating Scale is currently in use [11].

Based on the method of identification, biomarkers of HD are divided into three categories. These include clinical, bio-fluid, and imaging biomarkers. Clinical biomarkers are used to measure the motor, cognitive and psychotic abnormalities related to HD. Neurotransmitters, microglial toxins, and mHTT protein are listed under the category of bio-fluid biomarkers. Various techniques that are used to quantify their levels in blood and CSF include high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), mass spectrometry(MS), time-resolved fluorescence energy transfer (TR-FRET), homogeneous time-resolved fluorescence (HTRF), and enzyme-linked immune sorbent assay (ELISA) [45]. Imaging biomarkers are used for the detection of structural changes in brain with the help of imaging techniques such as MRI and [18F] MNI-659 PET [46, 47]. Various applications of these biomarkers are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biomarker of HD.

| S. No. | Biomarkers | Mediator | Molecule | Sample | Methods | Comments | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Clinical | Motor | -- | -- | Anti-saccade error rate | Understanding genetic and environmental factor for disease | [48] |

| - | - | -- | -- | Digitomotography | Assessment of quantitative motor by finger tapping. | [46, 49] | |

| Cognitive | - | - | SDMT | - | [46] | ||

| 2. | Bio-fluid | Immune system | IL-6,IL-8, IL-1β | CSF, Blood | MSD immunoassay, ELISA | Leukotriene inflammatory mediator activate NFκB and cause neuroinflammation | [50] |

| - | - | TNF-α | CSF | MSD antibody-based tetraplex array | Tumour necrosis factor α inflammatory mediator activate NFκB and cause neuroinflammation | [51] | |

| - | Genetic HTT mutation | HTT Protein | Blood | TR-FRET, HTRF, ELISA |

- | [45] | |

| - | - | mHTT protein | CSF, Blood | IP-FCM, ELISA, HTRF |

mHTT protein can increase OS. | [52] | |

| - | Microglial markers | YKL-40, MCP1, Chitotriosidase | CSF | ELISA | - | [53] | |

| - | Microglial toxins | 3-HK, QUIN, ROS | - | - | - | - | |

| - | Neurodegeneration | neurofilament light (NfL) | CSF, Blood | ELISA | Analyse premanifest and manifest Huntington's pateints | [54] | |

| - | - | GABA | CSF | Radioreceptor assay, Ion-exchange fluorometry |

Diminution of inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA | [55] | |

| - | - | - | Blood | Ion-exchange chromatography, High resolution proton NMR spectroscopy and HPLC |

- | ||

| - | - | Choline | CSF | Radiochemical micro-method | - | [56] | |

| - | - | Dopamine | CSF | - | - | - | |

| - | Transglutaminase | Nε-(γ-l-glutamyl)-l-lysine (GGEL) | CSF | MS | - | [57] | |

| - | - | γ-glutamylspermidine, γ-glutamylputrescine, bis-γ glutamylputrescine |

CSF | HPLC | - | [58] | |

| 3. | Imaging | Structural loss | -- | -- | MRI | Neurodegeneration seen in the brain | [46] |

| - | PDE10 uptake | -- | -- | [18F]MNI-659 PET | - | [47] |

4. TREATMENT STRATEGIES

Till now, none of the available drugs has been able to show complete relief in symptoms of the disease. Tetrabenazine, however, has been reported to show the most significant response in terms of reducing symptoms of motor abnormality (chorea) [59]. A combination of antipsychotic, anti-depressant, and anti-AD medicines is reported to reduce cognitive, psychotic, and motor abnormalities [60-62]. Tetrabenazine is a monoamine enzyme inhibitor that prevents the loss of adrenergic neurotransmitters in the synapse. It has been found to be useful in the treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorder. The major side effects of this drug are depression, exacerbation of depression, akathisia, restlessness, and psychotic problems [59]. Haloperidol is an antipsychotic drug that causes inhibition of dopamine in the limbic system of the brain and reduces psychotic symptoms of Huntington patients [63]. The side effects of this drug are suppression of movement, mood changes, breast enlargement, irregular menstrual periods, and loss of interest in sex. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) enzyme inhibitors such as rivastigmine and galantamine can enhance the ACh levels in the brain and improve cognitive function [62]. These drugs are reported to show side effects such as dizziness, drowsiness, loss of appetite, and weight loss. The drugs that have been explored to treat HD in animal studies are listed in Table 2. Apart from the pharmacological approach, some non-pharmacological approaches such as psychotherapy, speech therapy, physical therapy and occupational therapy have also shown beneficial effects for the treatment of the disease. A combination of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy has been reported to work in a better way as compared to the use of a single modality [64]. Some in vitro cell line studies showed that the use of stem cells is able to reduce the degeneration of neurons by reducing CAG sequencing in genetic bases. The list of such studies is given in Table 3. To date, a number of clinical and preclinical studies have been conducted on different drugs, but none of them has shown complete treatment of HD. Herbal drugs offer the third treatment strategy for HD. These have been reported to possess a better safety profile and are easily available as compared to synthetic drugs [65]. The use of herbal drugs in traditional medicines has shown neuroprotective effects in NDs [66]. Their antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptosis, and AChE enzyme inhibition have been reported to be responsible forthe treatment of cognitive, psychotic, and motor dysfunctions associated with HD [11].

Table 2.

Preclinical studies of synthetic drugs are reported for the treatment of HD.

| S. No. | Drugs | Animal | Dose (mg/kg) | Duration of Study | Side effect | Mechanism of Action | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Tetramethylpyrazine | Male Wistar rats | 40 and 80 | 21 days | - | Reduce 3-NP neurotoxin | Effective against 3-NP induce HD model | [67] |

| 2. | Rivastigmine | Male Wistar rats | 0.5, 1,2 | 15 days | Drowsiness, loss of appetite/weight loss, diarrhea, weakness, dizziness | AChE inhibitor | Improved cognitive function | [61] |

| 3. | Galantamine | Female Wistar rats | 3.75, 7.5 | 21 days | Drowsiness, dizziness, loss of appetite, and weight loss | AChE inhibitor | Reduction in oxidative stress, Neuroprotective effect against 3-NP induced neurotoxicity. |

[62] |

| 4. | Amantadine | Male Wistar rats | 10, 40 | -- | Blurred vision, nausea, and loss of appetite, dry mouth, constipation, or trouble sleeping, leg swelling and skin discoloration | NMDA glutamate antagonist | Amantadine binds with NMDA receptor and increases dopamine in postsynaptic receptors and helps to improve neurological and psychological conditions associated in NDs. | [68] |

| 5. | Haloperidol | Male Lister Hooded rats |

1.5 | 112 day | dry mouth, constipation, sedation, tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonism, depression, extrapyramidal symptoms, neuroleptic malignant syndrome | decrease dopamine | Used in the treatment of chronic neuroleptics and reduce locomotors activity in the brain | [63] |

| 6. | Leveteracetam | Human | 3,000 mg/day | -- | Infection, asthenia, neurosis, drowsiness, headache, nasopharyngitis, nervousness, abnormal behavior, agitation, anxiety, apathy. | Neuroprotective effect | Dose of 3,000 mg/day for 48 hour reduced the symptoms of chorea in HD | [69] |

| 7. | Terabenzine | Human | 50 mg/day | -- | Drowsiness, sedated state, muscle rigidity, depersonalization depression, exacerbation of depression, akathisia, and restlessness. | Inhibition of MAO enzyme | Dose of 50 mg/day useful in treatment of hyperkinetic movement disorder | [59] |

Table 3.

Cell line studies of HD.

| Disease | Cell line | Test | Results | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | LUMCi007-A, LUMCi007-B, LUMCi008-A, LUMCi008-B, LUMCi008C |

-- | Reducing CAG repeats | [70] |

| ICGi018-A (iHD38Q-3) | DNA fragment analysis of PCR-product |

In vitro cell line studies reduce CAG18 and 38 repeats by PBMCs and iPSC line |

[71] | |

| CSSi006-A (3681) | Sequencing | Reducing CAG repeats in fibroblasts (17 ± 2 and 46 ± 3 CAG repeats) | [72] | |

| CSSi004-A (2962) | Sequencing | Reducing CAG repeats in fibroblasts (17 ± 1 and 43 ± 2 CAG repeats) | [73] | |

| Genea090 human embryonic stem cell line | Sterility | The cell line is tested and found negative for Mycoplasma and any visible contamination | [74] | |

| Genea017 human embryonic stem cell line | Sterility | The cell line is tested and found negative for Mycoplasma and any visible contamination. Mycoplasma and any visible contamination | ||

| Herbal formula B401 | -- | Neuroprotective and angiogenesis effects in R6/2 mouse model of HD | [75] | |

| CurcuminSolid lipid nanoparticles (SLNs) (C-SLNs) | SDH Staining, Mitochondrial Oxidative Stress Parameters | Reduce ROS, mitochondrial dysfunction and lipid preroxidation. | [76] |

5. NEUROPROTECTIVE HERBS

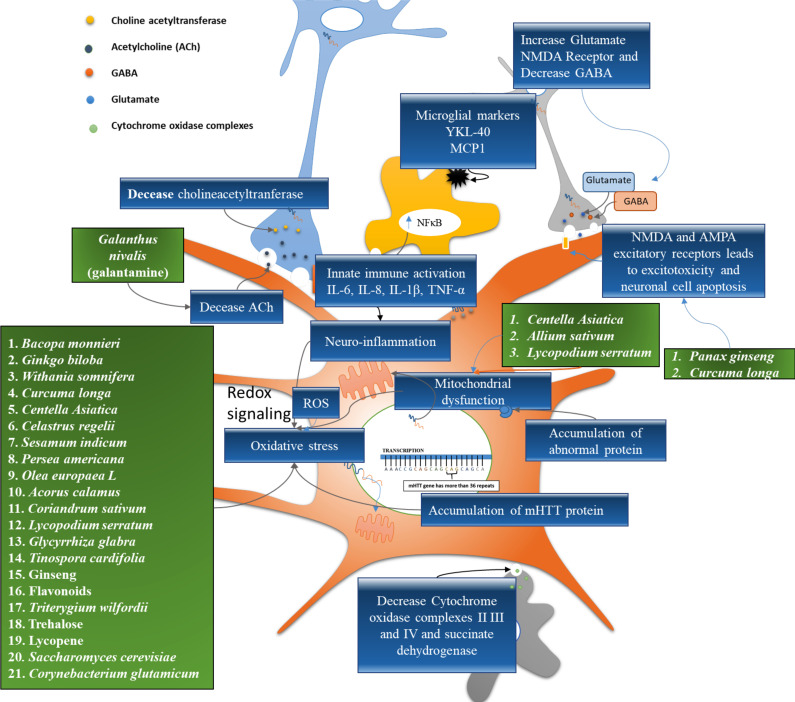

Herbal medicines contain complex mixtures of phytoconstituents and organic chemicals, including alkaloids, fatty acids, sterols, flavonoids, glycosides, saponins, terpenes, etc. Phytoconstituents present in some of the herbal drugs have shown pharmacological efficacy in reducing the symptoms of HD. In India, traditional herbal plants have been used for a number of diseases afflicting the nervous system. VataVyadh is a Sanskrit word that means disease related to the nervous system. Vata represents energy around the body, and disturbance of this process is called as VataVyadh. It ultimately leads to weakness, hypersensitivity, dementia, and chorea [77]. Certain herbal drugs possess phytoconstituents that enhance ACh levels in post synaptic neurons by inhibiting AChE in synapse and enhancing cognitive function [78, 79]. The in vivo studies have shown that certain herbal drugs and their phytochemicals exhibit a significant response against 3‐NP neurotoxin. Several other pathways are also crucial in HD. Based on the concept of multi targets, network pharmacology-based analysis is employed to find out related proteins in disease networks. The network targeting method aims to find out the related mechanism of efficacious substances in a rational design way. Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) prescriptions would be used for research and development against HD [80]. Virtual screening is performed to obtain drug molecules with high binding capacity from TCM. Mechanism of action and beneficial effects of herbal drugs are shown in Fig. (3).

Fig. (3).

Phytoconstituents and their target of HD. Note: Green boxes indicate the herbal drugs used to inhibit various molecular pathways and blue indicate the molecular targets (biomarkers). (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

5.1. Acorus Calamus (AC)

AC, also known as the Sweet flag, belongs to Araceae family. It acts as a brain and nervous system rejuvenator with beneficial memory-enhancing properties. It also improves learning efficiency, and reduces behavioral alteration. The major constituents of the plant are α-and β-asarone. β-Asarone has the ability to suppress beta-amyloid-induced neuronal apoptosis in the hippocampus through reversal down-regulation of Bcl-2, Bcl-w, caspase-3 activation, and phosphorylation of c-Jun terminal kinase (JNK) [81]. It has the potential to enhance dopaminergic nerve function. Therefore, it can play a key role in PD by increasing the amount of striatal extracellular dopamine and the expression of tyrosine hydroxylase in substantia nigra. It also improves the expression of DJ-1 genes in the striatum and thus acts as PD neuroprotective [82]. The treatment of PD using AC indicates its neuroprotective action; hence, it could be used for the treatment of HD.

5.2. Allium Sativum (AS)

AS is one of the most widely researched herbs found in the ancient medical literature [83, 84]. AS belongs to the family Amaryllidaceae. The main bioactive compounds of AS are allicin (allyl2-propene thiosulfinate or diallyl-thiosulfinate) and alliin. S-allyl cysteine (SAC) is the major component of the extensively studied aged garlic extract (AGE) [85, 86]. SAC exerts antioxidant activity, both directly and indirectly. It also decreases protein oxidation and nitration. In addition to this, it is reported to reduce lipid peroxidation and DNA fragmentation. Dopamine levels, oxidative damage, and lipid peroxidation in 1-methyl-4-phenyl pyridinium and 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) models of PD were found to be downregulated by SAC. It decreased lipid peroxidation and mitochondrial dysfunction in 3-nitro propionic acid and quinolinic acid animal models of HD. It also increased the dismutase activity of manganese and superoxide copper/zinc and prevented changes in behavior. AGE activates the expression of significant genes required for neuronal survival, both directly and indirectly [87, 88].

5.3. Bacopa Monnieri (BM)

BM or Herpestis monniera, commonly referred to as Brahmi, belongs to the family scrophulariaceae. It is found throughout the Indian subcontinent and is categorized in Ayurveda as Medhya Rasayana [89-92]. It is used to treat epilepsy, insomnia, anxiety and is a memory enhancer [93, 94]. The significant chemical components present in the plant are tri-terpenoid saponins like dammarane, bacosides A and B [90, 95]. In addition to these significant components, it also contains other saponins, including bacopa saponin A‐G [96-98], along with pseudo-jujubogenin, jujubogenin [99], bacopaside I‐V, X, and N1 and N2 [100-102]. Brahmine, herpestine, and monnierin are also present in the plant [103, 104]. The potential of this plant in improving memory has been well reported [94, 105-107]. Bacoside A has been shown to be the main constituent to enhance memory [90, 108]. In clinical trials, BM showed significant dose- dependent memory enhancement activity [109]. BM also acts as a metal ion chelator [110], scavenges free radicals, and shows the antioxidant property in the body [111, 112]. The neuroprotective and memory improving potential of BM’s extracts have also been reported. It exhibits antioxidant [112], anti-stress [113], antidepressant [114], anxiolytic [115], free radical scavenging [111], hepatoprotective [116] and antiulcerogenic activity [117]. 3‐NP inactivates the succinate dehydrogenase cell enzyme (SDH) and the electron transport chain complex II‐III [118, 119]. It also reduces ROS, malondialdehyde (MDA), and free fatty acid levels [120]. The oral intake of BM’s leaf powder is reported to reduce basal concentrations of several oxidative markers and improve thiol-related antioxidant molecules, and antioxidant enzyme activity suggesting its significant antioxidant potential. Dietary BM’s supplements were reported to lead to substantial protection against oxidative damage caused by neurotoxins in the brain [93]. BM has been found to be helpful in HD’s therapy owing to its protective impact against stress-mediated neuronal dysfunctions also [112].

5.4. Centella Asiatica (CA)

CA, also known as Hydrocotyle asiatica, Gotu kola, Indian Pennywort, and Jal brahmi belongs to the family Umbelliferae. CA has exhibited many neuropharmacological effects that include memory enhancement [121, 122], increased neurite elongation, and nerve regeneration acceleration [123]. It has also been reported for its anti-oxidant properties [124, 125]. Triterpenoid saponins, including asiaticoside, Asian acid, madecassoside, and madecassic acid, are the most significant chemical constituents of CA [126, 127]. Other minor saponins present in CA are brahmoside and brahminoside [126, 128]. Various acids that are present in the plant are triterpene acids, betullic acid, brahmic acid, and isobrahmic acid [126, 128]. The essential oils that are present in plant leaves include monoterpenes such as bornyl acetate, α-pinene, β-pinene, and π-pinene [129]. In addition to these constituents, CA is also reported to contain flavones, sterols, and lipids. Attenuation of 3-NP-induced depletion of GSH, total thiols, and endogenous antioxidants level by CA has been reported in the striatum and other brain regions [130]. It also displayed protection against 3-NP-induced mitochondrial dysfunctions, viz., reduced SDH activity, enzymes in the electron transport chain, and reduced mitochondrial viability [130].

5.5. Coriandrum Sativum (CS)

CS, commonly known as coriander, belongs to Apiaceae family. It contains a number of flavonoids. The major phytoconstituents include glucoronides such as quercetin and polyphenols such as caffeic acid, protocatechinic acid, and glycitin. The flavonoid content of the plants is reported to be equivalent to 12.6 quercetin equivalents per gram, while polyphenolic content is equivalent to 12.2 gallic acid equivalents per gram [131, 132]. A study showed that the CS’s extract enhanced concentrations of superoxide dismutase (SOD), glutathione, CAT, and total protein in the animal model. It also reduced the levels of cerebral infarction, lipid peroxidation (LPO), and calcium in the rats [133]. Scopolamine and diazepam-induced memory deficits were found to be reversed by leaf extracts of CS. It reduced reactive modifications in brain histology such as gliosis, lymphocytic infiltration, and cellular edema. It showed protective function in the states of cerebrovascular insufficiency. The leaves also demonstrated antioxidant properties in terms of free radical scavenging activity by 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl and lipoxygenase inhibition [134-136].

5.6. Curcuma Longa (CL)

The common name used for the CL is turmeric. It is a perennial herb and belongs to the family Zingiberaceae. It is used throughout the world, mainly in China, Japan, and India, as a pharmacotherapeutic [137]. It has a long history of use as a spice and household remedy to treat inflammation, skin diseases, wounds, as well as antibacterial and antiseptic agent [138]. CL contains different curcuminoids, sesquiterpenes, essential oil, and starch. Most of the curcuminoids are diarylheptanoid, curcumin being the most prevalent. Desmethoxycurcumin and bis-desmethoxycurcumin are the other two curcuminoids [138, 139]. CL shows a number of pharmacological actions such as antioxidant [140], anti-inflammatory [141], choleretic, hepatoprotective, analgesic, antifungal, free radical scavenging, antiparasitic, antiviral, antibacterial [138, 142], and anti-mutagenic [143]. The antioxidant properties of turmeric are attributed to its direct scavenging of superoxide radicals, chelating action [140, 144, 145], and by induction of antioxidant enzymes such as glutathione‐S‐transferase, glutathione peroxidase, catalase, superoxide dismutase, and hemeoxygenase [145]. It shows anti-inflammatory action by restricting cyclooxygenase-2 pathway (COX-2).In various neurological disorders, it is reported to show neuroprotective action [146]. Curcumin alone or along with manganese complex provides protective action against vascular dementia due to its antioxidant activity [147-149], and it is also helpful in treating aging and memory dysfunction [150]. In one of the studies, it has been reported that chronic administration of curcumin enhanced body weight continuously and increased SDH activity in rats treated with 3‐NP [150]. The reversed 3‐NP‐induced motor and cognitive impairment, along with a powerful antioxidant property, indicate that curcumin may be helpful in treating HD [150].

5.7. Galanthus Nivalis (GN)

GN, commonly known as snowdrop, belongs to the family Amaryllidacea. Galantamine, a tertiary isoquinoline alkaloid, is the main ingredient found in bulbs and flowers of GN. The neuroprotective activity of galantamine is due to this alkaloid. It is a reversible carbamates AChE inhibitor. Galantamine is an FDA approved drug that is used to treat AD. It can stimulate nicotinic receptors that further improve memory and cognition [151]. The drug allosterically modulates nicotinic receptors of ACh, particularly subtypes α7 and α3β4, to increase the release of ACh on cholinergic cells [152].

5.8. Ginkgo Biloba (GB)

GB is an ancient Chinese herbal plant having neuroprotective properties [153]. The active phytoconstituents are mainly obtained from the leaves and flowers of the plant. These include flavonoids (quercetin, isorhamnetins and kaempferol), bioflavonoids (bilobetin, sciadopitysin, 5-methoxybilobetol, isoginkgetin, ginkgetin and aimoflavone), proanthocyanidins, Trilactonic diterpenes (A-C ginkgolide and J-M ginkgolide), and sesquiterpenes (bilobalide) [154-156].

This plant’s leaf extract has been reported to be effective against dementia, cardiovascular diseases, stress, tumor and led to increased peripheral and central blood flow [157]. It also showed numerous pharmacotherapeutic activities due to its antioxidant effect [158], anti-platelet activating factor activity, and inhibition of amyloid-beta (Aβ) peptide aggregation [159, 160]. In one of the studies, the extract of GB (100 mg / kg, i.p. for 15 days) reversed neurobehavioral deficits induced by 3‐NP and also reduced striatal MDA [161]. The standardized extract of Ginkgo Biloba (EGb 761) also caused up and downregulation of the expression of Bcl-xl and striatal glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase concentrations, respectively. These biochemical findings suggested the neuroprotective function of EGb 761 in HD [161]. The extracts of GB have been reported to commonly induce biphasic dose responses in a range of cell types and endpoints (e.g., cochlea neural stem cells, cell viability, cell proliferation) [162]. The magnitude and width of the low dose stimulation of these biphasic dose responses are similar to those reported for hormetic dose responses. These hormetic dose responses occur within direct stimulatory responses as well as in preconditioning experimental protocols, displaying acquired resistance within an adaptive homeodynamic and temporal framework and repeated measurement protocols. The demonstrated GB’s dose responses further reflect the general occurrence of hormetic dose responses that consistently appear to be independent of the biological model, endpoint, inducing agent, and/or mechanism. These findings have important implications for consideration(s) of study designs involving dose selection, dose spacing, sample size, and statistical power [163].

5.9. Glycyrrhiza Glabra (G. glabra)

G. glabra, commonly referred to as Yashti-madhuh, belongs to the family Leguminosae. G. galabra contains an isoflavane glabridin. It has been reported to exert various pharmacological activities such as antiviral, anticancer, anti-ulcer, anti-diabetic, antioxidant, immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory, and anticonvulsant effects. Glabridin reduces the amount of MDA and glutathione, and increases the amount of SOD in the brain [164, 165]. G. glabra lowers the brain concentrations of neurotransmitters such as glutamate and dopamine and reduces the activity of AChE [166].

5.10. Lycopodium Serratum (LS)

LS belongs to the family lycopodiaceae. Alkaloid huperzine is obtained from LS extract [167]. As per the literature, this alkaloid shows AChE inhibition activity. Therefore, it increases the level of ACh in post synaptic receptors in the brain. LS elicits the same kind of effects as AChE inhibitor drugs [168]. The component huperzine is also used for the treatment of AD because it inhibits the ACh enzyme, acts as an antioxidant, and possesses anti-inflammatory properties [169]. Huperzine has been reported to have several neuroprotective effects such as apoptosis, the rectification of mitochondrial dysfunction, and anti-inflammatory effects [170].

5.11. Olea Europaea (OE)

It is commonly known as olive oil and belongs to the family Oleaceae [171]. Fruits’ oils contain many nutritious chemical constituents such as triacylglycerols, glycerol, free fatty acid, pigments, phosphatides, and flavor compounds [172]. Olive oil is very nutritious to the health and is also used as cooking oil. Some of the pharmacological studies have reported the potential effects of olive oil and extravagant olive oil against cardiovascular diseases [173], AD [174, 175], PD [176, 177], MS, and cancer [178, 179]. In studies conducted by Visioli et al. (1998) and Tasset et al. (2011), potential effects of extravagant olive oil have been reported against HD due to its antioxidant property [180] and neuroprotective effects [181]. In pharmaceutical formulations such as emulsions, olive oil acts as a solubilizer. In one of the studies, Guo el al., have used olive oil as a solubilizer for lycopene. The lycopene loaded microemulsions (LME) were prepared in which lycopene has been dissolved in olive oil. The potentials of microemulsion in improving bioavailability and brain-targeting efficiency following oral administration were investigated [182]. The pharmacokinetics and tissue distributions of optimized LME were evaluated in rats and mice, respectively. The pharmacokinetic study revealed a dramatic 2.10-folds enhancement of relative bioavailability with LME against the control lycopene dissolved in olive oil (LOO) dosage form in rats. Moreover, LME showed a preferential targeting distribution of lycopene toward the brain in mice, with the value of drug targeting index (DTI) up to 3.45 [182].

5.12. Plants Containing Trehalose

Trehalose was subsequently found in mosses, ferns, green algae, and liverworts [183]. It is found in many plants that grow in low and high altitudes, as well as in many organisms like bacteria, yeast, fungi, insects, invertebrates [184, 185]. It has been found in the literature that trehalose inhibits the formation of amyloid [186, 187]. Besides these, it also helps in inhibiting polyglutamine (polyQ) 3-mediated protein aggregation and reduced toxicity caused by Huntington's aggregates. Tanaka et al. (2004) and Sarkar et al. (2007) conducted a study on HD using HD R6/2 mouse model. It was found that trehalose helped in the inhibition of polyQ-induced pathology by stabilizing the partly unfolded mutant proteins [188, 189]. It has also been reported that, by offering neuroprotective activity against HD, trehalose increases autophagic activity against multiple aggregations of proteins such as mHTT [188].

5.13. Panax Ginseng (PG)

PG root is a well-known herb used in China, Japan, and Korea as a tonic to revitalize and restore adequate body metabolism for over more than 2,000 years [190]. The most prevalent species of PG are Asian ginseng and American ginseng (Panax1 quinquefolium L.) from the Araliaceae family. PG is a neuroprotective herb, and its neuroprotective potential can be used to prevent and treat neurodegenerative diseases such as AD, PD, HD, depression symptoms, and strokes [163, 191]. The major constituent that is responsible for the neuroprotective action of PG is ginsenoside. In recent years a number of studies have been reported on the role of ginsenosides in the prevention of NDs [192]. Moreover, the results of some of the clinical trials conducted on PG and its constituents, ginsenosides, and gintonin, revealed that they are safe [192]. PG contains tetracyclic dammarane, triterpenoids, saponin glycosides, and ginsenosides as their active constituents [193, 194]. Different studies (in vitro and in vivo) have shown positive results of ginseng in various pathological conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, CNS disorders, cancer, immune deficiency, and hepatotoxicity [194, 195]. It also has antioxidant [196], anti-apoptotic [196], anti-inflammatory [197], and immune-stimulating functions [195]. It helps in decreasing lipid peroxidation by inhibiting excitotoxicity and over-influx of Ca2+ into neurons. It retains concentrations of cellular ATP, preserves neuronal structural integrity, which helps in increasing cognitive performance [195]. Ginsenoside Rb1 and Rg3 are reported to exhibit protective effects by preventing Ca2 + influx through glutamate receptors on cortical neurons against glutamate-induced cell death [198]. Ginseng contains saponins that are NMDA glutamate antagonists. They reduce intracellular Ca2+ influx in the hippocampus; hence glutamate type NMDA receptors get inhibited, and this results in reduction of the symptoms of HD [199]. Ginsenosides Rb1, Rb3, and Rd showed a neuroprotective impact on striatal neuronal harm caused by 3‐NP [200-202].

5.14. Sesamum Indicum (SI)

Sesamol is obtained from the plant SI, frequently referred to as sesame, belonging to family Pedaliaceae. It is used in India and other East Asian nations as a healthy food [203]. The oil obtained from sesame is responsible for its pharmacological activities. Its active component, sesamol, is accountable for its antioxidant activity [204]. It helps in reducing hyperlipidemia, blood pressure, and lipid peroxidation by diminishing enzymatic and non-enzymatic oxidants stress. It also has tumour suppressant action [205]. Sesamol has been reported to have its protective effect against HD through suppression of the expression of nitric oxide (NOS) [206]. It is also reported to attenuate behavioral, biochemical, and cellular changes in 3‐NP‐induced animals [207]. It has been reported to protect the brain against memory impairment caused by 3‐NP, OS, neuroinflammation in the neurons of the hippocampus, and thus increases synaptic plasticity and neurotransmission [208].

5.15. Solanum Lycopersicum (SL)

SL is commonly referred to as tomato and belongs to the family Solanaceae. Lycopene is a well-known carotenoid found in tomatoes and tomato-based goods in considerable quantities [209]. It has been reported to possess powerful neuroprotective [210], antioxidant [211, 212], antiproliferative, anticancer [213], anti-inflammatory [214], memory enhancing [215], and hypocholesterolemic properties [216]. It is a stronger singlet oxygen carotenoid quencher for vitamin E and glutathione [216]. Treatment with lycopene considerably helps in the reduction of multiple behavioral and biochemical changes induced by 3‐NP, indicating its therapeutic potential against HD’s symptoms [217].

5.16. Tinospora Cordifolia (TC)

TC belongs to the family Menispermaceae and is frequently known as Giloy. Phytochemical constituents such as alkaloids, steroids, diterpenoid lactones, aliphatics, and glycosides are present in giloy extract [218]. TC has been reported for memory enhancing property, immunostimulation, and enhancement of ACh synthesis [219]. It has powerful free radical scavenging characteristics and also reduces ROS and reactive nitrogen species as studied by paramagnetic resonance electron spectroscopy [220]. It also reduces the level of glutathione, gamma-glutamyl-cysteine ligase expression, copper-zinc superoxide dismutase genes, owing to which it can be used for the treatment of hypoxia, ischemia, and neuronal injury [220]. Additionally, TC is helpful in enhancing dopamine levels in the brain and improving cognitive and psychotic function [219].

5.17. Tripterygium Wilfordii (TW)

The root extract of TW has been extensively used as traditional Chinese medicine for the treatment of inflammation and autoimmune diseases such as rheumatic arthritis [221]. TW’s root extract also showed neurotropic and neuroprotective effects [222]. Celastrol and Triptolide are the two major neuroprotective phytoconstituents that are isolated from the root extract of TW. It has many therapeutic potentials such as antioxidant [223], anti-inflammatory [221], anticancer [224], and insecticidal activity [225]. A pro-inflammatory study conducted on animals using 1‐methyl‐4‐phenyl‐1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine (MTPT) indicated that celastrol helped in improving the functions of dopaminergic cells, increasing the dopaminergic level [222]. By controlling the expression of the thermal shock protein gene in dopaminergic cells, it has also provided protection against 3-NP-induced striatal damage [222, 226].

5.18. Withania Somnifera (WS)

WS is also known by the common name Ashwagandha. It belongs to the family Solanaceae. For centuries, it has been used in Ayurvedic medicine [227]. Ashwagandha’s root extract has been reported to possess antioxidant [228, 229], memory enhancing [230], anti-inflammatory [231], immunomodulatory [232], anti-stress [233], and anti-convulsant characteristics [234]. As an antioxidant, WS and its active ingredients (sitoindosides VII‐X and withaferin A) increase catalase, ascorbic acid, endogenous superoxide dismutase, and reduce lipid peroxidation [235-237]. It functions as an anti-inflammatory agent through complement inhibition, the proliferation of lymphocytes, and delayed hypersensitivity. Different trials have shown that WS increases cortisol circulation, decreases tiredness, increases physical performance, and decreases refractory stress depression [238]. It also modulates different receptor systems for neurotransmitters in the CNS. Major active constituents of WS include steroidal lactones and alkaloids (collectively referred to as withanolides). Withaferin A, withanolide A, withanolide D‐P, withanone, sitoindoside VII‐X are the major isolated withanolides from WS. WS inhibits AChE and increases the level of ACh in the brain. The beneficial effects of herbal drugs against HD are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

Effect of herbal drugs and phytoconstituents.

| Name of Herbal Medicine | Synonyms | Source | Bioactive Component | Structure | Animal Models | Effects | Refs. | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AC | Sweet flag | α-and β-Asarone |

-- | Antioxidant, anti-inflammatory | [239] | ||||||||||||||||||

| AG | Ginseng | Whose root | Ginsenosides | -- | Antioxidant, anti-apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and immune-stimulating functions | [195-197] | |||||||||||||||||

| WS | Withania root, asgandh, winter cherry. | Dried Roots | Withaferin A | 3-nitropropionic acid model | Reduce oxidative/nitrosative stress, inhibits complex II of the mitochondrial electron transport chain |

[240] | |||||||||||||||||

| BM | Kapotvadka, somvalli and saraswati | Aerial parts | Bacoside A, | 3-nitropropionic acid induce model | Memory enhancer | [241] | |||||||||||||||||

| Bacoside B, | 3-nitropropionic acid induce model | Facilitates anterograde memory | |||||||||||||||||||||

| CR | Celastrol (tripterine) | -- | Celastrol | -- | Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, and inhibition of Pro-inflammatory cytokines. | [221] | |||||||||||||||||

| CL | Indian saffron, curcuma, Turmeric, Haldi | Fresh rhizomes | Curcumin | 3-nitropropionic acid-induced HD rat model and inhibitory response against AMPA receptor | Anti-oxidant, Anti-inflammatory and reduce excitotoxicity | [242] | |||||||||||||||||

| Name of Herbal Medicine | Synonyms | Source | Bioactive Component | Structure | Animal Models | Effects | Refs. | ||||||||||||||||

| Demethoxy curcumin | -- | Rotenone-induced PD in rats | Anti-oxidant and Anti-inflammatory | ||||||||||||||||||||

| CS | Coriander | Leaves |

Coriandrum sativum extract |

Ischemic reperfusion insult in brain | Neuroprotective effects | [133] | |||||||||||||||||

| GN | Snowdrop | Bulbs and flowers | Galantamine 0.1 mg/kg, s.c. |

Scopolamine-induced amnesia model in mice | Reduce AChE enzyme and increase ACh in postsynaptic receptor | [243] | |||||||||||||||||

| Ginkgo (GB) | Ginnan, maidenhair tree. | Leaf | Gingkolides A,B,C,J and M | -- | 3-nitropropionic acid model | Memory enhancer property and Anti-Platelet Activating Factor (Anti-PAF) | [161] | ||||||||||||||||

| GG | Yashti-madhuh or liquorice | Stems | Glabridin | -- | - | Antioxidant | [244] | ||||||||||||||||

| CA | Spade leaf, Indian Pennywort, Mandukaparni | Asiatic Acid | -- | Neuroprotective effect against harm caused by OS and Mitochondrial dysfunction | [245] | ||||||||||||||||||

| LS | Ground pines or creeping cedar, Qian Ceng Ta. | Leaves | Huperzine A | -- | Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory and reduce mitochondrial dysfunction | [170] | |||||||||||||||||

|

Persea

Americana |

Avocado | Peel, seed coat and seeds | Persea major methanolic extract (0.5 mg/ml) | -- | Cellular viability assay, Glutamate uptake assay | Antioxidant capacity, increased glutamate uptake | [246] | ||||||||||||||||

| OE | Olive-growing | Oil | Olive oil, Extravirgin olive oil (20 mg/kg ip) |

3-nitropropionic acid-induced HD-like rat model | Reduces oxidative damage | [181] | |||||||||||||||||

|

Sesamum

indicum |

Sesame, benne | Oil | Sesamol | -- | Neuroprotective effect | [247] | |||||||||||||||||

| TC | Giloe | Stem | Tinospora cordifolia-stem methanolic extract | -- | 6-hydroxy dopamine (6-OHDA) lesion rat model, Cadmium-induced OS in Wistar rats | Anti-OS, Memory enhance and Increase dopamine level in to brain. | [248] | ||||||||||||||||

| Name of Herbal Medicine | Synonyms | Source | Bioactive Component | Structure | Animal Models | Effects | Refs. | ||||||||||||||||

| TW | Thunder god vine | Root extracts | Celastrol, Triptolide | -- | Antioxidant effects | [249] | |||||||||||||||||

| Fruits, vegetables, tea, cocoa and wine |

-- | -- | Flavonoids | -- | Effects against OS and Inflammation | [250] | |||||||||||||||||

| Mosses ferns, green algae, and liverworts | -- | -- | Trehalose | induced damage in bovine spermatozoa | Antioxidant effects | [183, 251] | |||||||||||||||||

| SL | Tomato | Hole fruits | Lycopene | 3-nitropropionic acid-induced HD rat model | Inhibition of cognitive dysfunction and motor abnormality and antioxidant effects | [252, 253] | |||||||||||||||||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Corynebacterium glutamicum | Rasberry | Fruit | Salidroside | Inhibit the SOD1 and HTT genes and also show anti-inflammatory effects. | Reduce the symptoms of HD by acting oxidative stress and inflammation, and HTT genes. | [254] | |||||||||||||||||

6. CURRENT ONGOING CLINICAL TRIALS

A limited number of clinical trials have been reported for the treatment of HD. This could be attributed to a lack of complete understanding of the underlying mechanism of the disease as the drugs used so far have been unable to provide complete relief to patients. Some of the trials that have been completed or are ongoing, are listed in Table 5.

Table 5.

Ongoing clinical trial of HD.

| Disease | Drug | Sample Size | Purpose | Phase | Status | Design | Study State | Study end |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HD | THC, CBD | 21 | Treatment | Phase 2 | Completed | DB, R, CO | December 30, 2011 | February 1, 2013 |

| EGCG | 54 | Treatment | Phase 1 | Completed | R | May 23, 2011 | June 16, 2015 | |

| PBT2 | 109 | Treatment | Phase 2 | Completed | DB, R | May 3, 2012 | July 18, 2016 | |

| DM/Q | 22 | Treatment | Phase 3 | Recruiting | R | February 26, 2019 | April 19, 2019 | |

| Triheptanoin | 10 | Treatment | Phase 2 | Completed | June 20, 2013 | March 24, 2016 | ||

| SD-809 | 90 | Treatment | Phase 3 | Completed | R, DB | January 2, 2006 | September 20, 2017 | |

| Digoxin, Dimebon | 12 | Treatment | Phase 1 | Completed | R | January 29, 2009 | June 12, 2009 | |

| Chorea | SD-809 | 90 | Treatment | Phase 3 | Completed | R, DB | February 21, 2013 | August 11, 2017 |

| Amantadine sulphate | 30 | Treatment | Phase 4 | Completed | NR | July 31, 2009 | June 28, 2011 | |

| HMD | Tetrabenazine | -- | -- | -- | Available | -- | March 24, 2008 | February 26, 2020 |

Abbreviations: CO; Cross Over, CBC, Cannabidiol, DB; Double Blind, DM/Q; Dextromethorphan/quinidine, EGCG; (2)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate, NR, Non-Randomized, R; Randomized, THC; Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol, HMD; Hyperkinetic Movement Disorders Based on search of clinicaltrial.gov (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=huntington+disease&term=&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=) [255] [Accessed May 26, 2020].

7. HORMESIS AND REDOX ASPECTS OF HERBAL DRUGS AND THEIR POTENTIAL CHEMICAL CONSTITUENTS

Hormesis is a biological process that has found its application in drug development, drug designing, and toxicological studies. It helps to rationalize the dose-response relationships [80, 256]. Hormetins are the chemical inducers of hormesis and possess a range of therapeutic applications, including protection against stress, toxin, and aging-related diseases [257, 258]. They have a protective effect at a low level and show deleterious effects at higher levels due to the narrow therapeutic window [259, 260]. Hormesis describes the phenomenon of pharmacological conditioning of the heart and brain where a low dose of pharmacological agents

activate various downstream cascades that have cardio and neuroprotective potential, but at high doses, their protective effect gets attenuated [261-263]. The spectrum of hormetic results, such as increased development, reproduction, survival, and a decreased disease occurrence, indicates the presence of thousands of genes, thereby influencing basic biological processes through hormetic mechanisms. In one of the recently published studies, Moghaddam et al (2019) [264] mentioned hormesis effects of curcumin. It is one of the types of hormetic agents because, at a low dose, curcumin shows stimulatory effects, while at high doses, it shows inhibitory effects. For example, at a low dose, curcumin shows antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects but in high dose curcumin is reported to cause autophagy and apoptosis or cell death [264, 265]. In another study, it is reported that quercetin showed antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective effects at its low dose whereas, at higher doses, it caused toxicity into the body such as mitochondrial oxidative stress [261, 266]. Another herbal drug, celastrol that is extracted from TW, has proven its neuroprotective effects in preclinical studies. It is also called “Thunder of God Vine”. This phytomedicine decreases the striatal lesion volume, which is induced by 3-NP at its low dose. At low doses, it showed antioxidant effects and reduced neuroinflammation induced by NFκB and TNFα signaling pathways. But at a high dose, celastrol increased the blood pressure and caused hypertension [261]. BM’s extract has many potential effects against neuronal diseases such as anxiety, depression, and various NDs. Whereas, its overdose causes dry mouth, stomach cramps, fatigue and bowel movement, etc. [94, 267]. Hence, hormetic processes should be considered because plant derivatives at low dose may provide pro-oxidants that are able to upregulate the expression of enzymes of innate detox pathways or, alternatively regulate the expression of vitagenes [259]. Various drugs shown in Fig. (3) have neuroprotective effects however, they also show hormesis effects.

Products such as wine extract, green tea, grape seed, PA, CL, OE, and TC extracts are all known to contain a large variety of potent antioxidants in the form of polyphenols like phenolic acids, gallic acid, stilbenes, tannins, flavanols, resveratrol, and anthocyanins, etc. [179, 268] Polyphenolic compounds act as iron chelators, radical scavengers, and modulators of pro-survival genes. These polyphenols activate the endogenous enzymes like glutathione peroxidase, catalase, or superoxide dismutase that directly modulate the level of free radicals [269]. In NDs, neuronal stress response activates pro-survival pathways, which control the activation or modulation of protective genes called vitagenes. These vitagenes produce endogenous enzymes, heat shock proteins, heat shock protein 72 (Hsp72), heme oxygenase-1, sirtuins, and the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system [260]. All these have potent anti-oxidant and anti-apoptotic activities against NDs. Polyphenols activate the vitagene system by upregulating the levels of antioxidant enzymes and sirtuin system, along with activation of heat shock transcription factors and Kelch-like erythroid cell-derived proteins with CNC homology [ECH]-associated protein 1)/antioxidant response element Keap1/Nrf2/ARE pathway that results in counteraction of pro-oxidant conditions in neuronal tissue [259]. In neuronal cells, mitochondria are the principal source of energy for their survival. In stressful conditions, neuronal cells compensate the energy demands of cells by changing the rate of mitochondrial fission and fusion. This process leads to excessive production of superoxide anions at the inner mitochondrial membrane that promotes the production of physiological or endogenous ROS. These mitochondria-derived ROS are involved in the aging process. The ROS directly modulates signal transduction pathways that enhance cellular proliferation [270]. These changes in mitochondrial activity interrupt the functionality of the mitochondrial network and promote the molecular abnormalities influencing mitochondrial dynamics. Since mitochondria play a critical role in neuronal physiology, impaired mitochondrial dynamics promote the NDs such as PD [176], AD [271, 272], and HD. Polyphenols like flavanols are known to have brain-permeability potential that directly benefits neuronal health. Several studies show that polyphenols have a neuroprotective role in NDs, for example, epigallocatechin gallate has neuroprotective potential in amyloid-beta-mediated neurotoxicity. Resveratrol acts by decreasing nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) level and microglia-induced neuroinflammation, thereby it protects the brain from the deleterious effect of ischemic injury. Polyphenols directly or indirectly modulate the levels of pro-and anti-inflammatory microRNAs in NDs [273-275]. Polyphenols have shown the potential to activate the mitochondrial biogenesis, in aged mice. They attenuated the deleterious effect of oxidative stress mediated damage and increased the physical endurance that resulted in prolonged survival of the animals [257, 276, 277].

8. NEED FOR NOVEL DRUG DELIVERY SYSTEMS

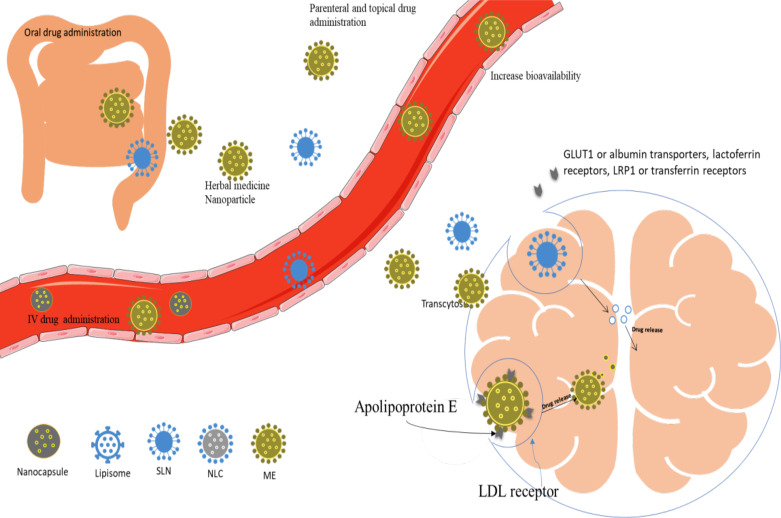

Herbal drugs have been reported to show very good neuroprotective effects; however, they have some limitations such as poor bioavailability, poor aqueous solubility, and lack of blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability. Novel drug delivery systems have been reported to enhance the bioavailability, therapeutic efficacy [278], stability, and brain permeability [279] of the herbal drugs and reduce their side effects, which, on the other hand, is hard to be achieved through conventional drug delivery systems [280-283]. Herbal drug-based nanoparticles are reported to reduce first pass metabolism and improve their bioavailability because their small particle size (less than 200 nm) enables them to cross endothelial cells of BBB by transcytosis [284]. Glucose transporter 1 (GLUT1) or albumin transporters, lactoferrin receptors, transferrin receptors ligands can enhance receptor-mediated transcytosis [285]. The mechanisms of targeting of BBB of drug-loaded nanoparticles are shown in Fig. (4). There are a number of studies in which the plant extracts or their active constituents have been reported to enhance the pharmacokinetic properties such as Cmax and AUC, thereby increasing their oral bioavailability. Hence, they have been able to treat various types of NDs such as PD, AD. Some of the studies entailing about enhancement of oral bioavailability are listed in Table 6. It is important to note that there is very limited information available regarding the formulation of nanoparticles to treat HD, and they are limited to pre-clinical studies. However, based on the success rate of NDDS in treating other neurodegenerative diseases apart

Fig. (4).

Mechanism of BBB permeability of the nanoparticles. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Table 6.

Pharmacokinetics parameters for the herbal drugs and their nanoparticles.

| S. No. | Plant Used | Phytoconstituent | NDDS | Outcomes | Refs. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 |

Malus

domestica, Allium cepa, etc |

Fisetin (FS) | Self-nanoemulsifying drug delivery system (SNEDDS) | • Cmax of FS SNEDDS increased by 3.7 folds as compared to naïve FS • AUC0-∞ of FS SNEDDS increased by 1.5 folds as compared to naïve FS • Increase in bioavailability (151.58%) |

[286] | |||

| 02 | Nigella sativa | Thymoquinone | SLNs | • Cmax of thymoquinone SLNs increased by 4.3 folds as compared to thymoquinone suspension • AUC0-∞ of thymoquinone SLNs increased by 6.19 folds as compared to thymoquinone suspension • Increase in bioavailability (619.3%) |

[287] | |||

| 03 | Nigella sativa | Thymoquinone | SLNs | • Cmax of thymoquinone SLNs increased by 4.8 folds as compared to thymoquinone • AUC0-∞ of thymoquinone SLNs increased by 5.53 folds as compared to thymoquinone • Increase in bioavailability (553%) |

[288] | |||

| 04 | CL | Curcumin | SNEDDS | • Cmax of curcumin SNEDDS increased by 9.1 folds compared with naïve curcumin • AUC0-∞ of curcumin SNEDDS increased by 7.5 folds as compared to naïve curcumin • Increase in bioavailability (754%) |

[289] | |||

| 05 | CL | Curcumin | Nanosuspensions | • Cmax of curcumin nanoparticles increased by 4.8 folds compared to naïve curcumin. • AUC0-∞ of Curcumin nanoparticles increased by 5.5 folds compared with naïve curcumin. • Increase in bioavailability (558%) |

[290] | |||

| 06 | CL | Curcumin | SLNs | • Cmax of curcumin nanoparticles increased by 49.27 folds compared to naïve curcumin. • AUC0-∞ of Curcumin SLNs increased by 39.06 folds as compared to naïve curcumin. • Increase in bioavailability (3906%) |

[291] | |||

| 07 | CL | Curcumin | Phospholipid complex | • Cmax of curcumin phospholipid complex increased by 2.4 folds as compared to naïve curcumin • AUC0-∞ of Curcumin phospholipid complex increased by 5.19 folds as compared to naïve curcumin • Increase in bioavailability (519%) |

[292] | |||

| 08 | GB, Allium cepa, Brassica oleracea var. italic etc | Quercetin | Zein nanoparticles | • Cmax of quercetin nanoparticles increased by 8.5 folds as compared to naïve quercetin • AUC0-120 of quercetin SLNs increased by 13.9 folds as compared to naïve quercetin • Increase in bioavailability (1396%) |

[293] | |||

| 09 | GB, Allium cepa, Brassica oleracea var. italic etc | Quercetin | SLNs | • Cmax of quercetin SLNs increased by 2.07 folds as compared to naïve curcumin • AUC0-48 of quercetin nanoparticles increased by 5.7 folds as compared with naïve curcumin • Increase in bioavailability (571.4%) |

[294] | |||

| 10 | Camellia sinensis | Epigallocatechin-3-Gallate (EGCG) | Nanolipidic particles | • Cmax of EGCG nanoparticles increased by 6.04 folds as compared to EGCG 10% ethanolic extract • AUC0-∞ of EGCG nanoparticles increased by 2.49 folds as compared to EGCG 10% ethanolic extract • Increase in bioavailability (249%) |

[295] | |||

| S. No. | Plant Used | Phytoconstituent | NDDS | Outcomes | Refs. | |||

| 11 | SL | Lycopene | Microemulsion | • Cmax of lycopene-loaded microemulsion increased by 1.8 folds as compared to lycopene devolved in olive oil • AUC0-∞ of lycopene-loaded microemulsion increased by 2.1 folds as compared to lycopene devolved in olive oil • Increase in bioavailability (210%) |

[182] | |||

| 12 | TW | Celastrol | Silk Fibroin Nanoparticles (SFNPs) | • Initial concentration of celastrol SFNPs increased by 4.36 folds as compared to celastrol in PEG 300 • AUC0-∞ of celastrol SFNPs increased by 2.61 folds as compared to celastrol in PEG 300 • Increase in bioavailability (261%) |

[296] | |||

| 13 | TW | Celastrol | Phytosomes | • Initial concentration of celastrol phytosomes increased by 5 folds as compared to celastrol • AUC0-∞ of celastrol phytosomes increased by 4.1 folds as compared to celastrol • Increase in bioavailability (410%) |

[297] | |||

| 14 |

Phaseolus vulgaris,

Glycine max, etc |

Genistein | Eudragit nanoparticles | • Cmax of genistein nanoparticles increased by 2.4 folds as compared to genistein suspension • AUC0-∞ of genistein nanoparticles increased by 2.4 folds compared to genistein suspension • Increase in bioavailability (241%) |

[298] | |||

| 15 | GN | Galantamine | SLNs | • Volume of distribution of galantamine SLNs increased by 1.15 folds as compared to galantamine • AUC0-∞ of galantamine SLNs increased by 2.14 folds as compared to galantamine • Increase in bioavailability (261%) |

[299] | |||

| 16 |

Silybum

marianum |

Silymarin | Nanostructured Lipid Carrier (NLCs) | • Cmax of silymarin NLCs increased by 3.4 folds as compared to silymarin pellets • AUC0-∞ of silymarin NLCs increased by 2.2 folds as compared to silymarin pellets • Increase in bioavailability (224%) |

[300] | |||

| 17 | Medagascar periwinkle | Vinpocetine | SLNs | • Cmax of vinpocetine SLNs increased by 3.2 folds as compared to vinpocetine • AUC0-∞ of vinpocetine SLNs increased by 4.16 folds as compared to vinpocetine • Increase in bioavailability (416%) |

[301] | |||

| 18 | Trifolium pratense | Biochanin A | NLCs | • Cmax of biochanin PEG-NLCs increased by 15.74 folds as compared to biochanin • AUC0-∞ of biochanin PEG-NLCs increased by 2.89 folds as compared to biochanin • Increase in bioavailability (289%) |

[302] | |||

| 19 | Glycine max | Genistein | Micellar emulsions (ME) | • AUC0-∞ of genistein MEs increased by 2.36 folds compared to genistein • Increase in bioavailability (236%) |

[303] | |||

from HD, it is anticipated that they may provide success in treating HD also. Hence, there is a dire need to explore those delivery systems loaded with aforementioned phytoconstituents/extracts to treat HD. Nevertheless, in this review some studies that have been reported to treat HD are discussed in the subsequent sections.

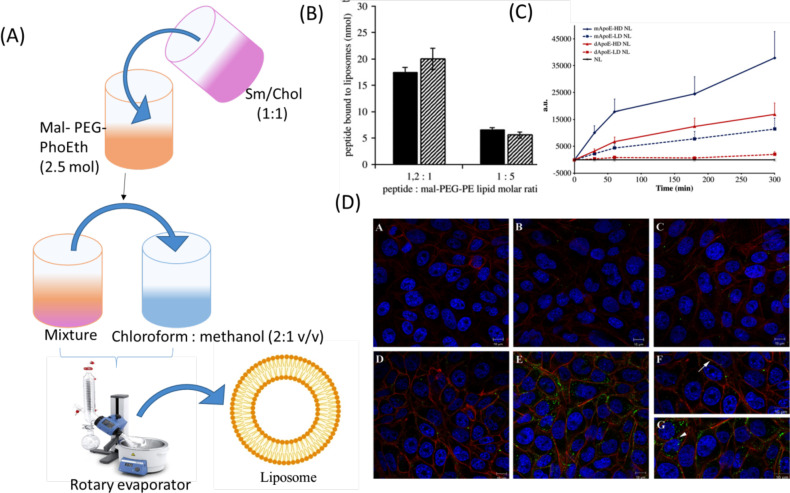

8.1. Nanoliposomes

The herbal drugs loaded in nanoliposomes have the potential to cross the physiological membrane barriers of the body owing to the submicron size of vesicles. The drugs loaded in the vesicles can bypass first pass metabolism and enhance oral bioavailability. Ligand (such as GLUT1, lactoferrin, transferrin) based nanoliposomes prepared through surface modification methods have been able to deliver several proteins, antibodies, and peptides [304]. Ligands help the liposomes to permeate BBB by transcytosis. Nanoliposomes can also enter the brain by passive diffusion, where they release entrapped drugs by energy dependent mechanism or passive efflux [304]. The limitation of liposomes is their short half-life, due to which the drug gets easily metabolized by hydrolysis and oxidation [305]. Francesca et al. studied the effect of curcumin-loaded apoprotein E (Apo-E) derived peptide nanoliposomes on HD. The liposomes were prepared by loading Apo-E in the dispersion of bovine brain sphingomyelin (Sm), cholesterol (Chol), and 1,2-stearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[maleimide(poly(ethylene glycol)-2000)] (mal-PEG-PhoEth) using thin film hydration method (Fig. 5A). The prepared liposomes showed particle size, PDI, and zeta potential of 132 ± 10 nm, 0.187, and −19.41 ± 0.09 mV, respectively. The ratio of Apo-E to Chol and Sm was kept constant. However, composition of Apo-E and mal-PEG-PhoEth were varied in the ratio of 1.2:1 and 1:5. During ApoE-liposome coupling, it was observed that when the ratio of peptide and mal-PEG-PhoEth was changed from 1:5 to 1.2:1, it resulted in increased density of ApoE on the surface of the liposome (Fig. 5B). It was observed that around 70,000 molecules of lipids were on the surface of the liposome, having a particle size of 140 nm and consisted of reactive mol-PEG-PhoEth (2.5 mol). Coupling efficiency was found to be 70%. The molar ratio of peptide and mol-PEG- PhoEth (1:5 to 1:2:1) after the incubation period showed a high density of 1200 and low density of 400 peptide molecules per single nanoliposomes particle (Fig. 5C). The in vitro cell line study was done on rat’s brain endothelial cells. The curcumin-nanoliposomes did not show any cytotoxicity as confirmed by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay. The liposomes were labeled by using a fluorescent dye and cellular uptake of the fluorescence labeled liposome was detected by using confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). It was found that liposomes in the absence of surface functionalization did not show any membrane accretion and cellular uptake of fluorescence. The Rat Brain Endothelial cells (RBE4) showed very less fluorescence at high and low density of peptides. It was observed that the green fluorescence of cells got increased with an increase in the high density of peptides. The green spots were near the nucleus below the plasma membrane. The liposomes coupled with peptide mApoE displayed effective uptake (Fig. 5D). The curcumin-nanoliposomes helped in treating HD by their interaction with low-density lipoprotein receptors via special Apo-E sequence amino acid and penetrated curcumin across the BBB through transcytosis without getting affected by lysosomal degradation. Hence, the obtained results revealed that ligand-based nanoliposomes successfully targeted BBB and protected the drug from degradation [306].

Fig. (5).

(A) The Curcumin liposomes were prepared by thin film hydration method. (B) Fluorescence estimation of the amount of mApoE (dark bars) and dApoE peptide coupled to liposomes at different peptide-to-lipid molar ratios. (C) Cell-associated fluorescence was evaluated using FACS analysis. (D) The localization and distribution of ApoE-NLs within RBE4 cells [306] Copyright © 2011 Elsevier. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

8.2. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLNs)

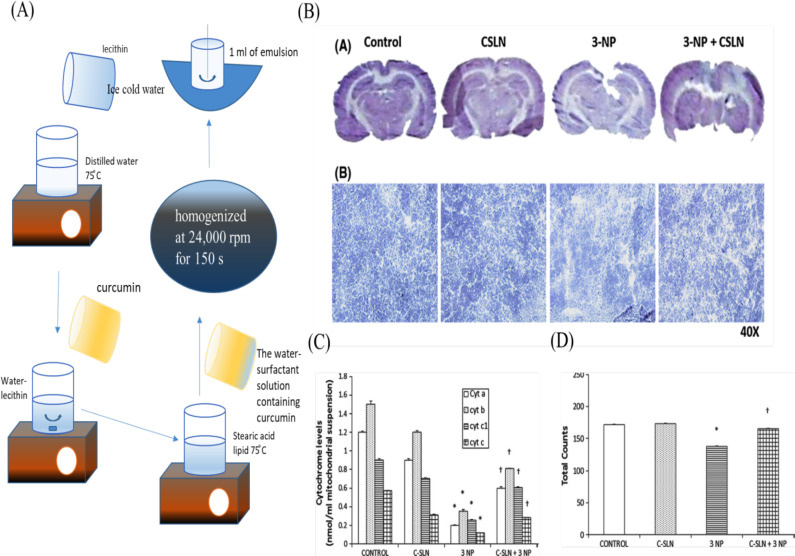

SLNs contain a solid lipid matrix stabilized by lipid molecules and physiological emulsifiers. Homogenization is used for the preparation of SLNs, where high temperature and high pressure provided by thermodynamic and mechanical stress causes size reduction of drug particles [307, 308]. SLNs are excellent nanocarriers to enhance the bioavailability of drugs and are highly biocompatible. SLNs of size ranging from 0 to 1000nm can be prepare during high pressure

homogenization. Those in size range of 120-200 nm can easily cross endothelial cells of BBB by endocytosis [309]. Brain permeability of SLNs can be enhanced by their attachment with ligand (e.g., apolipoprotein E) [310]. Limitations of SLNs are their low drug loading capacity and poor entrapment efficiency. In one of the studies carried by Sandhir et al. (2014), C-SLNs reported positive results against 3-NP induced HD rats. In this study, 20 mg/kg and 40 mg/kg drug was administered for 7days through oral route. C-SLNs were prepared by the homogenization method. In this formulation steric acid, lecithin taurocholate and curcumin were used. The formulation exhibited significantly dose dependent neuroprotective effects against neurotoxin (3-NP) (Fig. 6B). It also produced significant positive effect on mitochondrial cytochrome levels in striatum and spontaneous locomotor activity in total photobeam counts of 3-NP-induced HD rats [76] (Fig. 6C, D).

Fig. (6).

(A) C-SLNs prepared by halogenation method (B) Neuroprotective effects of C-SLNs reported against 3-NP in rat brain. (C) Effect of C-SLN on mitochondrial cytochrome levels in the striatum of 3-NP-induced HD rats. (D) Effect of C-SLN on spontaneous locomotor activity in terms of total photo beam counts of 3-NP-induced HD rats [76] Copyright © 2013, Springer Nature. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

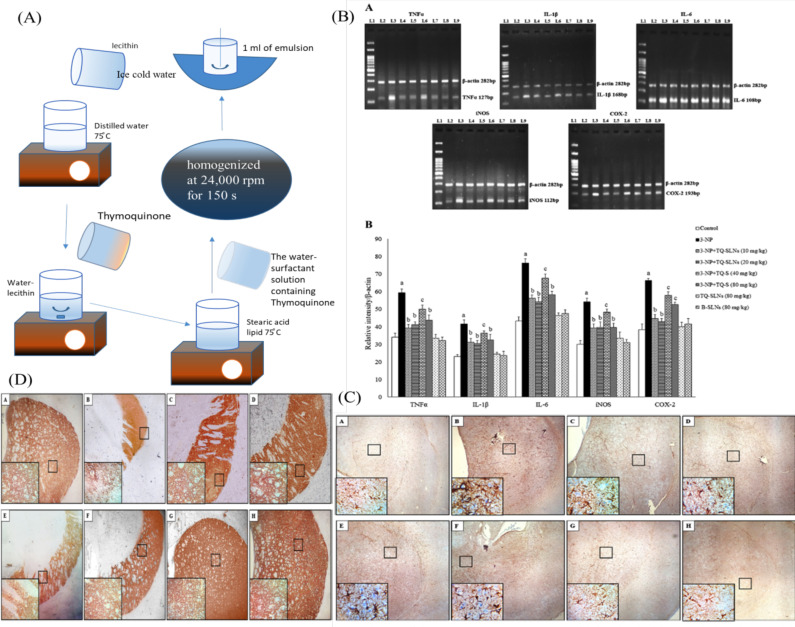

In another study, the authors have mentioned the pharmacological action of the thymoquinone (TQ). It is a strong antioxidant and also inhibits neuroinflammation. The drug still could not show the desired action in the in-vivo study [311] due to low solubility, leading to decrease drug absorption and bioavailability. Thereby, a drug cannot reach a desired concentration in the targeted side (the brain). Ramachandran et al. (2018) [312] prepared TQ-SLNs to enhance the bioavailability and brain permeability of the drug. TQ-SLNs were prepared by the homogenization method. (Fig. 7A) The inflammatory response was checked by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and TQ-SLNs showed anti-inflammatory effects. TQ-SLNs and Thymoquinone suspension (TQ-S) were found to inhibit inflammatory mediators including TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, and COX2 (Fig. 7B). The anti-inflammatory effects of TQ-SLNs and TQ-S reported in the glial fibrillary acid protein (GFAP)

Fig. (7).

(A) Formulation of TQ-SLN prepared by homosimeation method. (B) TQ-SLN has been showed dose dependent significant effects against the inflammatory mediator such as TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, iNOS, and COX2 (C) TQ-SLNs and TQ-S treatment attenuates the overexpression of GFAP in the striatal slices of 3-NP intoxicated animals. (D) TQ-SLNs and TQ-S treatment improve the expression of TH in the striatal slices upon 3-NP toxicity [312] Copyright © 2018, Springer Nature. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

and tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) against 3-NP induced animals model [312] are shown in Fig. 7C and D.

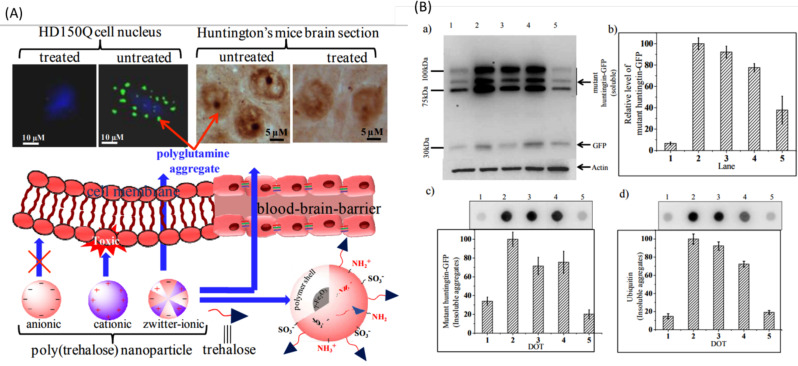

8.3. Polymeric Nanoparticles

The particle size of polymeric nanoparticles is approximately in the range of 10 nm to 1000 nm. These can be formulated in the form of nanospheres and nanocapsules. Nanospheres are made up of a matrix system. In nanocapsules, the drug is loaded into the cavity, which is made up of a polymeric membrane [313]. Debnath et al. (2017) reported the successful delivery of trehalose by enhancing its BBB permeability through poly(trehalose) nanoparticles. Poly(trehalose) nanoparticles were reported to be more potent as compared to trehalose molecules. They were found to inhibit polyglutamine aggregation in HD150Q cell in in vitro study. (Fig. 8A) Immunoblot analysis and Dot blot analysis of poly(trehalose) nanoparticles reduced polyglutamine levels and amyloid aggregation and also suppressed mHTT genes [314]. (Fig. 8B) Herbal drug nanoparticle formulation, animal models, and beneficial results are enlisted in Table 7.

Fig. (8).

(A) Zwitterionic poly(trehalose) can easily permeate BBB and inhibit polyglutamate aggregation in CNS. (B) a) Immunoblot analysis data of soluble huntingtin aggregates using (green fluorescent protein) GFP antibody. b) Quantification of band intensities of soluble huntingtin (tNhtt) shown in (a) using NIH image analysis software. Data are normalized against beta-actin. c) Dot blot analysis data of insoluble huntingtin aggregates using GFP antibody. d) Dot blot analysis using ubiquitin antibody [314] Copyright © 2017 American Chemical Society. (A higher resolution / colour version of this figure is available in the electronic copy of the article).

Table 7.

Herbal Nanoformulations reported for the treatment of HD in animal models.

| S. No. | Phytoconstituents | Formulation | Compassion | Animal Model | No. of Animal | Dose (mg/kg) | Duration of Study | Applications | Results | Biochemical Evaluation | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Curcumin | SLNs | Steric acid, lecithin taurocholate, Curcumin | Female wistar rats | 20 | 40mg/kg p.o. | 7 days | SLNs improved oral bioavailability of curcumin | Assessed its neuroprotective efficacy against 3-NP-induced HD |

Reduced GSH levels and SOD activity, reduction in mitochondrial swelling, lipid peroxidation, protein carbonyls and ROS |

[76] |

| 2 | poly(trehalose) | Polymeric nanoparticle | Sulfo-acrylate (to introduce SO3-), amino-acrylate (to introduce NH2), PEG-acrylate (to introduce PEG). |

The transgenic mice for HD [strain B6CBA-Tg (HDexon1) 62Gpb/3J] | -- | 0.4 mg/mL corresponding to 50 µM Trehalose, i.p. |

56 days and 84 days | Polymeric nanoparticles enhanced BBB permeability of the trehalose | Neuroprotective effects | Immuno- histochemical staining, |

[314] |

| 3. | Thymoquinone | SLNs | Steric acid, lecithin taurocholate, Thymoquinone |

Albino male rats | 48 | TQ-SLNs (10, 20mg/kg), TQ-SLNs (40,80mg/kg) p.o. |

14 days | SLNs increased the solubility, bioavailability and absorption of the thymoquinone. It also enhanced drug payload and sustained drug release ability | Due to this SLNs thymoquinone acts as halting 3- NP induced inflammation and degeneration. |

-- | [312] |

| S. No. | Phytoconstituents | Formulation | Compassion | Animal Model | No. of Animal | Dose (mg/kg) | Duration of Study | Applications | Results | Biochemical Evaluation | Refs. |

| 4. | Cholesterol | Nanaolipos omes | -- | Mice | 3 | Chol-D6-loaded liposomes (200 μg/mouse) | 2 days | Nanoliposomes enhanced brain delivery of cholesterol | Brain cholesterol (Chol) synthesis, which is essential for optimalsynaptic transmission | -- | [315] |

| 5. | Selenium | Nanoliposomes | -- | Worms | -- | -- | -- | Selenium Nanoparticles enhanced bioavailability and therapeutic efficacy with low toxicity | -- | 20μM, Nano-Se played a dosage-dependent protective effect on the viability after the exposure to both stress stimuli | [316] |

| 6. | Lithium | Microemulsion (NP03) | -- | YAC128 mouse | 20 μg Li/kg or 40 μg Li/kg body weigh i.e. 0.03 and 0.06 mEq/kg) |

2 months | Microemulsion of lithium (NP03) reduced the toxicity of lithium and increased the absorptions at targeted site | NP03 improves motor function and rescues striatal pathology and testicular atrophy in YAC128 mice. | -- | [317] | |

| 7. | Coenzyme Q10 (CoQ10) | Coenzyme Q10 | -- | R6/2 transgenic mouse | 110 | (CoQ10) 1000, 5000, 10000, or 20000 mg/kg/day and (HydroQ-sorb) 400, 1000, and 2000 mg/ kg/day |

150 days | -- | Showed neuroprotective effects | -- | [318] |

CONCLUSION

The prevention of NDs is essential for the aged population globally. Phytoconstituents serve as novel medicinal therapies in the present scenario. Herbal drugs are reported to have multiple actions such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-proliferative and anti-apoptotic. Many of them are also reported to reduce AChE levels in synapses. Hence, they could offer a pragmatic alternative to the current synthetic drugs that are being used to treat HD. Various preclinical and clinical studies have been highlighted in the manuscript indicating a significant positive response against symptoms of HD. Despite having such therapeutic potential, the efficacy of herbal drugs has not been widely explored due to their poor solubility and pharmacokinetic properties. Herbal drugs incorporated in various nanocarriers such as nanoliposomes, microemulsions, SLNs, and polymeric nanoparticles have shown very good efficacy to treat HD due to the enhancement in their bioavailability ordirect targeting to specific cells. This has further helped in the reduction of their dose as well as toxicity. The major challenges associated with the formulation of herbal drug-loaded nanoparticles include the poor loading of drugs in the formulation, low stability of herbal drugs during their processing, difficulty during scale-up of the process, and low stability of nanoformulations. Hence, it is important to look at these issues prior to the start of pre-clinical studies. Upon getting successful pre-clinical reports, a thorough clinical study is required for their positioning into the market.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declared none.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- 3-NP

Nitropropionic acid

- 6-OHDA

6-hydroxydopamine

- AC

Acorus calamus

- ACh

Acetylcholine

- AChE

Acetylcholinesterase

- AD

Alzheimer Disease

- ALS

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis

- Anti-PAF

Anti-Platelet Activating Factor

- AS

Allium sativum

- ATP

Adenosine Triphosphate

- Aβ

Amyloid beta

- BBB

Blood Brain Barrier

- BM

Bacopa monnieri

- CA

Centella Asiatica

- CAG

Cytisine-Adenine-Guanine

- CAT

Choline-Acetyl Transferase

- CL

Curcuma Longa

- CNS

Central Nerves System

- COX-2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- CS

Coriandrum sativum

- CSF

Cerebrospinal Fluid

- DTI

Drug Targeting Index

- EGCG

Epigallocatechin gallate

- ELISA

Enzyme-Linked Immune Sorbent Assay

- G. glabra

Glycyrrhiza glabra

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- GAD

Glutamate Decarboxylase

- GB

Ginkgo biloba

- GFAP

Glial Fibrillary Acid Protein

- GLUT1

Glucose Transporter1

- GN

Galanthus nivalis

- HD