Summary

Fructose consumption is linked to the rising incidence of obesity and cancer, two of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally1,2. Dietary fructose metabolism begins at the small intestine epithelium, where it is transported by GLUT5 and phosphorylated by ketohexokinase to form fructose 1-phosphate, which accumulates to high levels in the cell3,4. While this pathway is implicated in obesity and tumor promotion, the exact mechanism driving these pathologies in the intestine remains unclear. Here, we show that dietary fructose promotes intestinal cell survival and increases intestinal villus length across multiple murine models. Increased villus length expands gut surface area and increases nutrient absorption and adiposity in mice fed a high-fat diet. In hypoxic intestinal cells, fructose 1-phosphate inhibits the M2 isoform of pyruvate kinase to promote cell survival5–7. Genetic ablation of ketohexokinase or stimulation of pyruvate kinase prevents villus elongation and abolishes HFCS-promoted nutrient absorption and tumor growth. The ability of fructose to promote cell survival via an allosteric metabolite thus provides additional insight into Western-diet associated adiposity and a compelling explanation for HFCS-promoted tumor growth.

Humans in the western world consume more fructose now than ever before in recorded history. Agricultural and industrial advances have improved the access to sweeteners like sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS), which have tripled total fructose consumption and contributed to a burgeoning epidemic of obesity and related diseases8,9. The global rise in obesity is directly linked to an increase in obesity-related cancers like colorectal cancer (CRC), whose incidence and mortality is rising among young adults10,11. Several observations suggest a causal relationship between fructose consumption and CRC. For example, fructose consumption is associated with gastrointestinal cancer incidence and progression12–15, and drives tumor growth and metastasis in CRC animal models16,17.

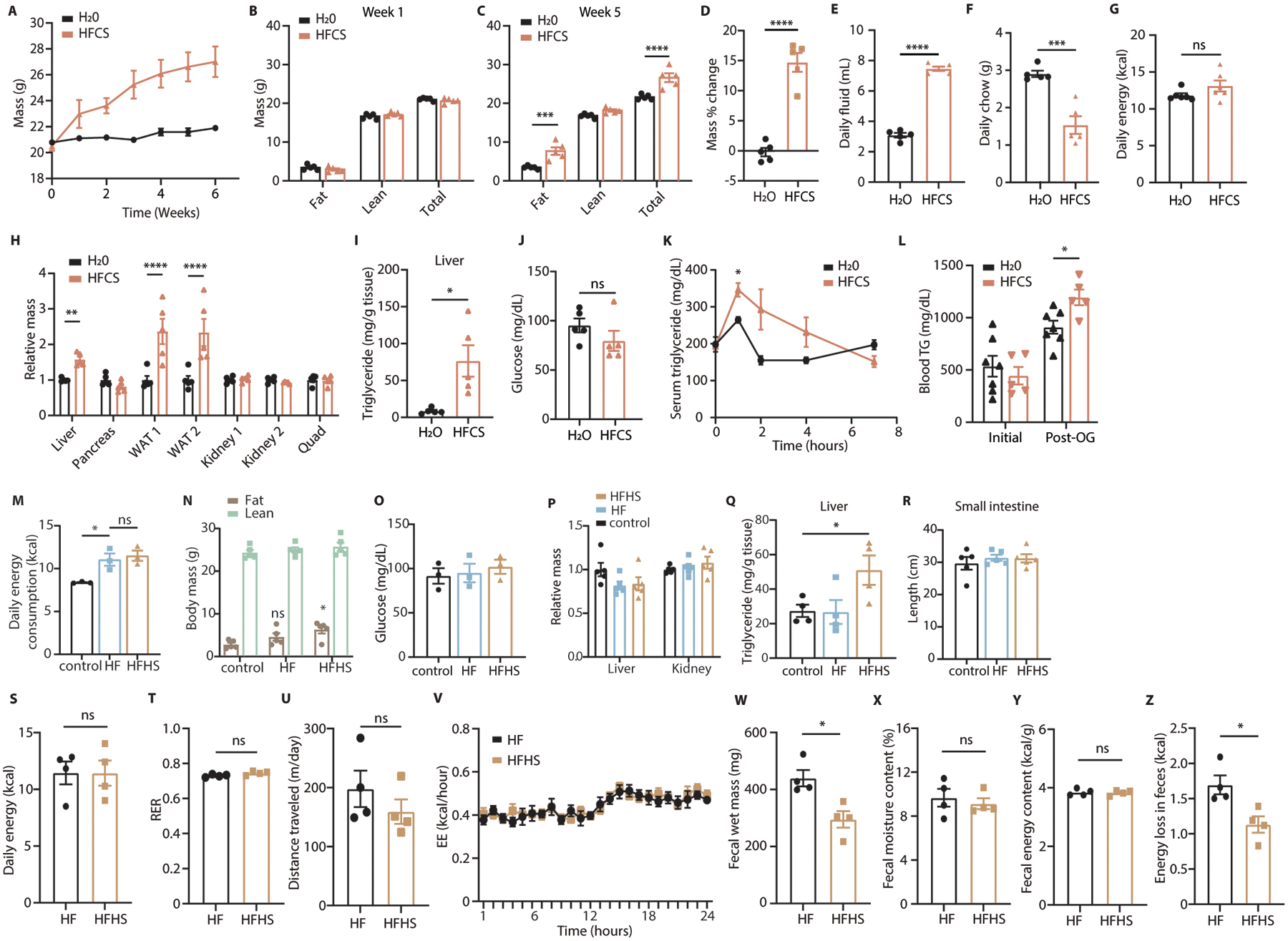

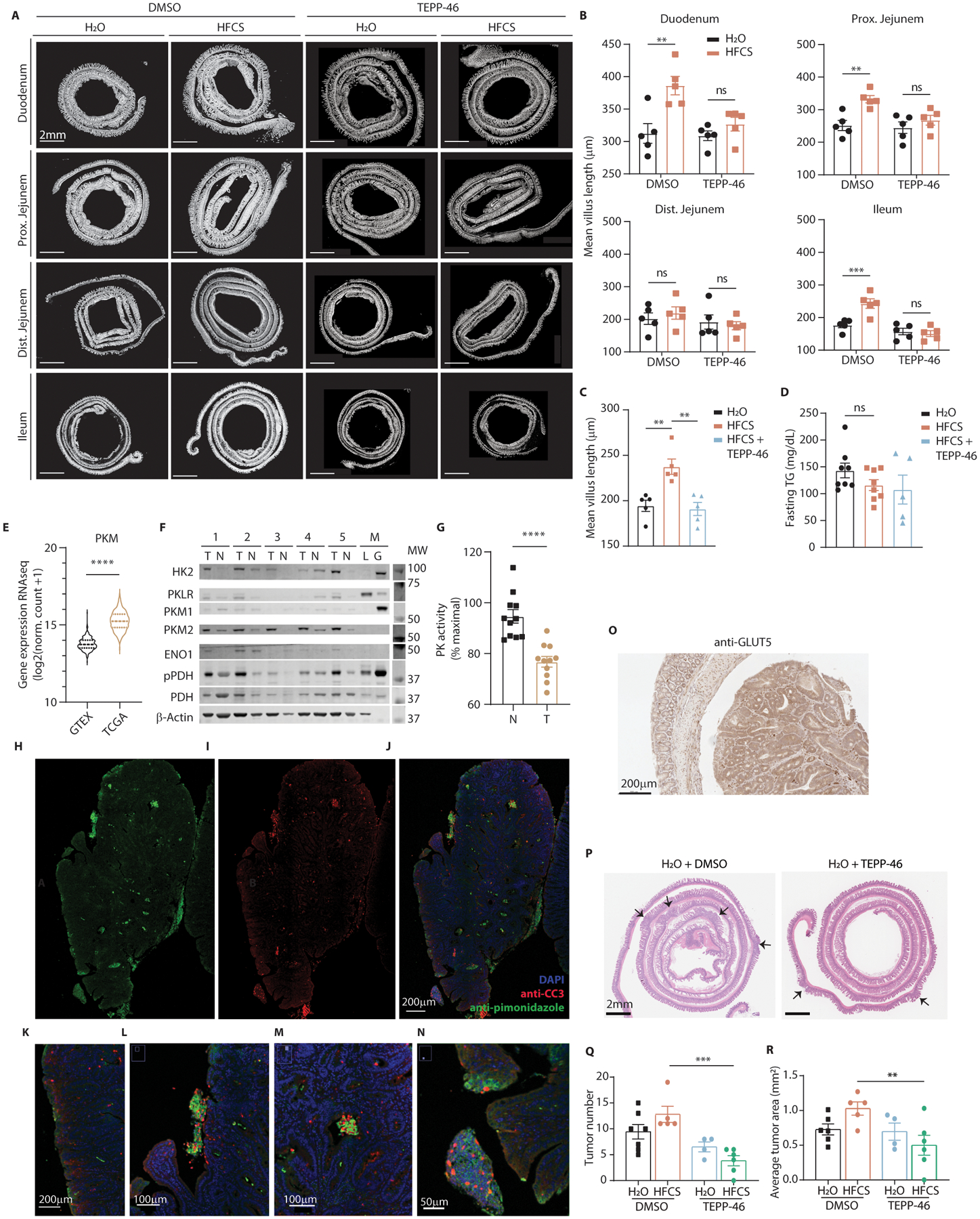

Since tumor growth is driven by hyperplasia and tumor cells frequently retain metabolic pathways from their tissue of origin, we hypothesized that fructose would promote hyperplasia of the normal intestinal epithelium just as it promotes growth in intestinal tumors. To assess this, we fed mice HFCS for 4 weeks and quantified mean intestinal villus length using a high-throughput, unbiased image segmentation-based approach (E.D. 1A–F). Mice of both sexes and a variety of ages and genetic backgrounds treated with HFCS showed a 25–40% increase in intestinal villus length in the duodenum and proximal jejunum (Fig. 1A, E.D. 1H). The increase in villus length correlated with increased weight gain and fat accumulation as well as lipid absorption (E.D. 2A–L).

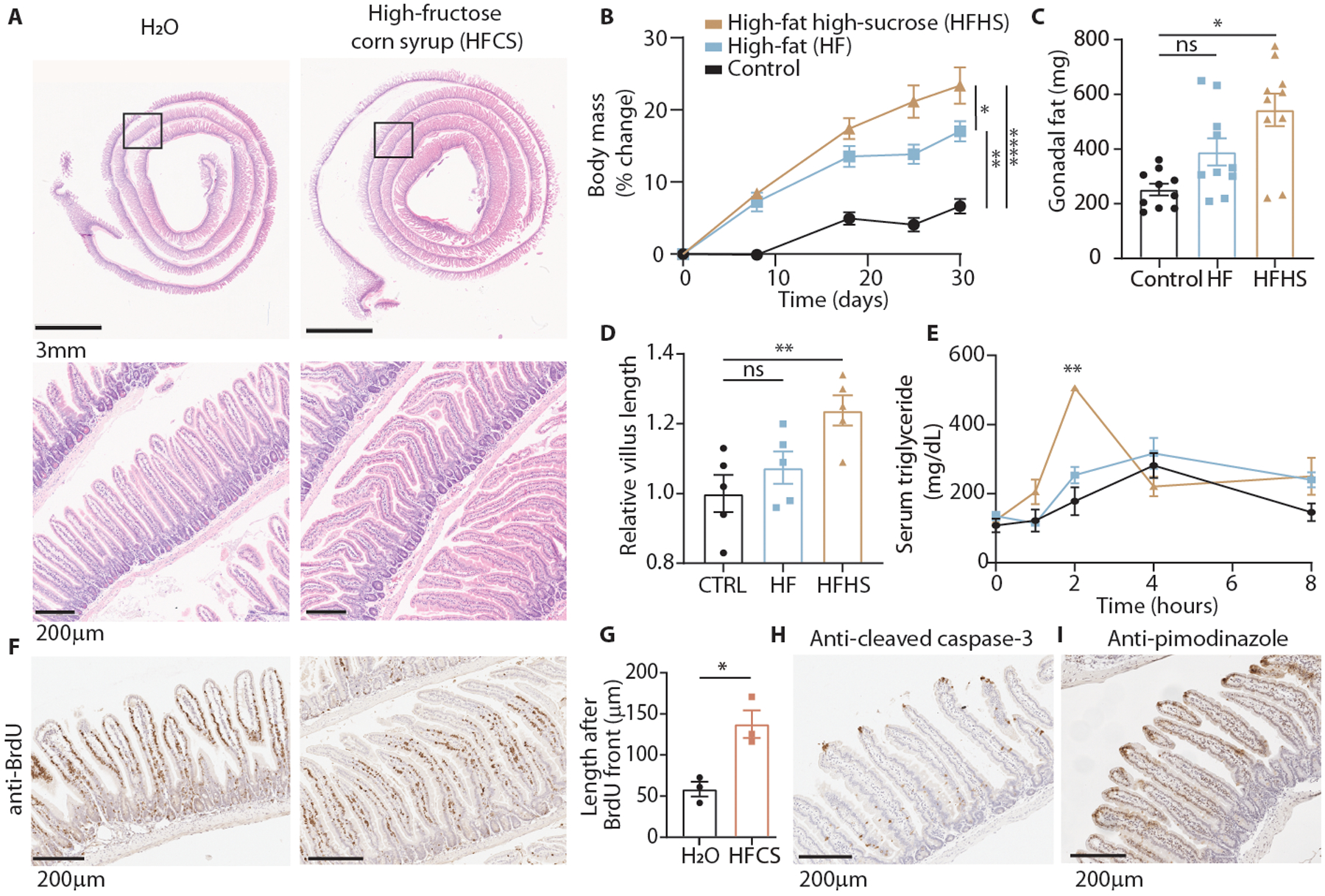

Fig. 1. Dietary fructose increases intestinal villus length and lipid absorption.

(A) H&E-stained duodenum from animals fed normal chow with ad libitum water or 25% high-fructose corn syrup for 4 weeks. (B) Relative change in body mass of mice fed control, high-fat (45% kcal fat), or high-fat high-sucrose chow (control, HF: n = 5 mice, HFHS: n = 4 mice). (C) Mass of white adipose tissue from the gonadal depot after 5 weeks on each diet (n = 5 mice per group, 2 depots per mouse). (D) Relative duodenal villus length after 5 weeks on each diet (n = 5 mice per group). (E) Serum triglyceride levels in fasted mice following an oral olive oil gavage (n = 3 animals per group). (F) BrdU immunohistochemistry (IHC) of duodenal sections from H2O or HFCS-treated mice 72 hours after intraperitoneal BrdU injection. (G) Duodenal villus length distal to the BrdU front (n = 3 mice per group, 40 villi per mouse). (H, I) IHC for the indicated targets in duodenal sections from H2O-treated mice. B-E: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; G: two-sided student’s t-test. ns: not significant; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001; exact P-values are provided in source data for all figures; all data represent means ± S.E.M.

We hypothesized that this increase in absorption would exacerbate weight gain in animals placed on a high-fat diet (HFD) that contained fructose. Over 4 weeks, mice were treated with a control diet that contained no fructose, a standard HFD (45% kcal fat) that contained dextrose but no fructose, or an isocaloric HFD where sucrose (30% kcal sugar) was added instead of dextrose (Table S1). Mice consuming the sucrose-fortified HFD gained significantly more weight and fat mass than those on the standard HFD, despite consuming and expending the same amount of energy (Fig. 1B, C, E.D. 2M–V). In agreement with the data from mice consuming a normal chow (low fat) diet, mice fed fructose in the form of sucrose had similar small intestinal length but longer villi (Fig. 1D, E.D. 2R), exhibited increased serum triglycerides following an oral lipid bolus (Fig. 1E), and lost less energy in feces compared to isocaloric, sucrose-free controls (E.D. 2W–Z). These data suggest that dietary fructose increases intestinal villus length and nutrient absorption.

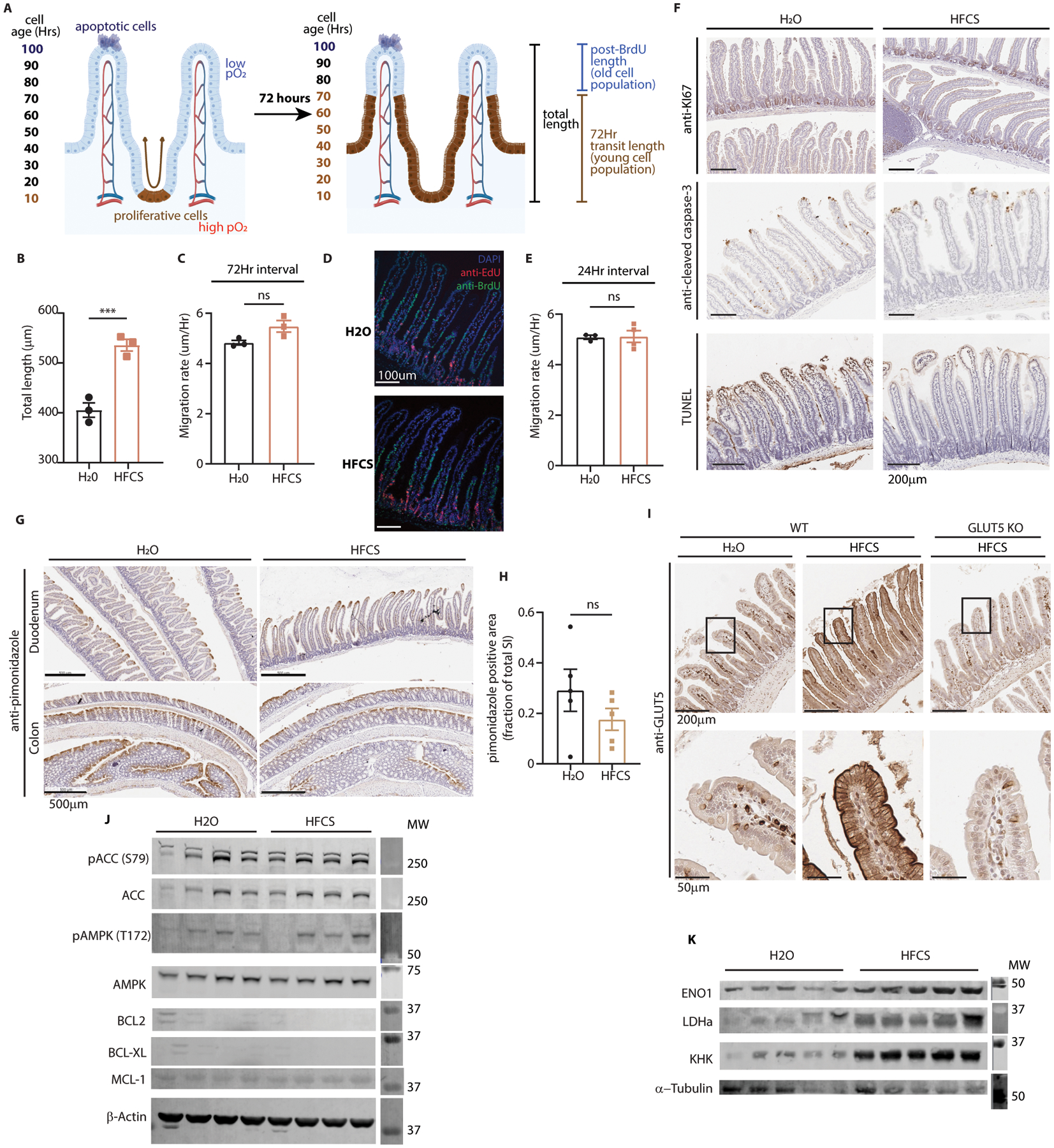

Intestinal villus length is determined by a balance between the rates of epithelial cell proliferation and death. Thus, the villus is constantly in a state of self-renewal as stem cells in the crypt divide to yield new epithelial cells (IECs), which then transit outward until they reach the villus apex and are extruded into the intestinal lumen18. To determine whether the longer villi resulted from increased migration rate (i.e. proliferation) or increased cell survival, we conducted single and dual-label tracing experiments using bromo-deoxyuridine (BrdU) and ethynyl-deoxyuridine (EdU) injections at multiple different timepoints. These assays showed that HFCS-treated duodenal villi had similar migration rates as H2O controls (E.D. 3A–E), but had more than twice the population of IECs surviving longer than 72 hours (Fig. 1F, G). There was also no change in cell proliferation as assessed by histologic Ki67 staining (E.D. 3F). These data indicate that cell survival is a major determinant of villous hypertrophy in the presence of fructose.

Cell transit up the intestinal villus terminates with cell death and extrusion into the intestinal lumen18. Indeed, in all cases where extruding cells were captured in histological sections, staining for the apoptosis marker cleaved caspase-3 (CC3) or terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) was positive, regardless of diet (Fig. 1H, E.D. 3F). Since IECs migrate away from their blood supply during their transit along the villus, this cell death is likely influenced by tissue hypoxia. Consistent with this theory, pimonidazole staining, used to indicate tissues where oxygen is below 10 mmHg, correlated with distance from the muscularis layer in small and large intestine in both H2O and HFCS-treated animals (Fig. 1I, E.D. 3G, H). Despite this apparent similarity in hypoxia patterns in H2O and HFCS-treated animals, we observed an increase in HIF-1α target proteins ENO1 and LDHA in HFCS-treated intestinal epithelium and a strong upregulation of fructolytic proteins including GLUT5 and ketohexokinase (KHK) (E.D. 3I–K).

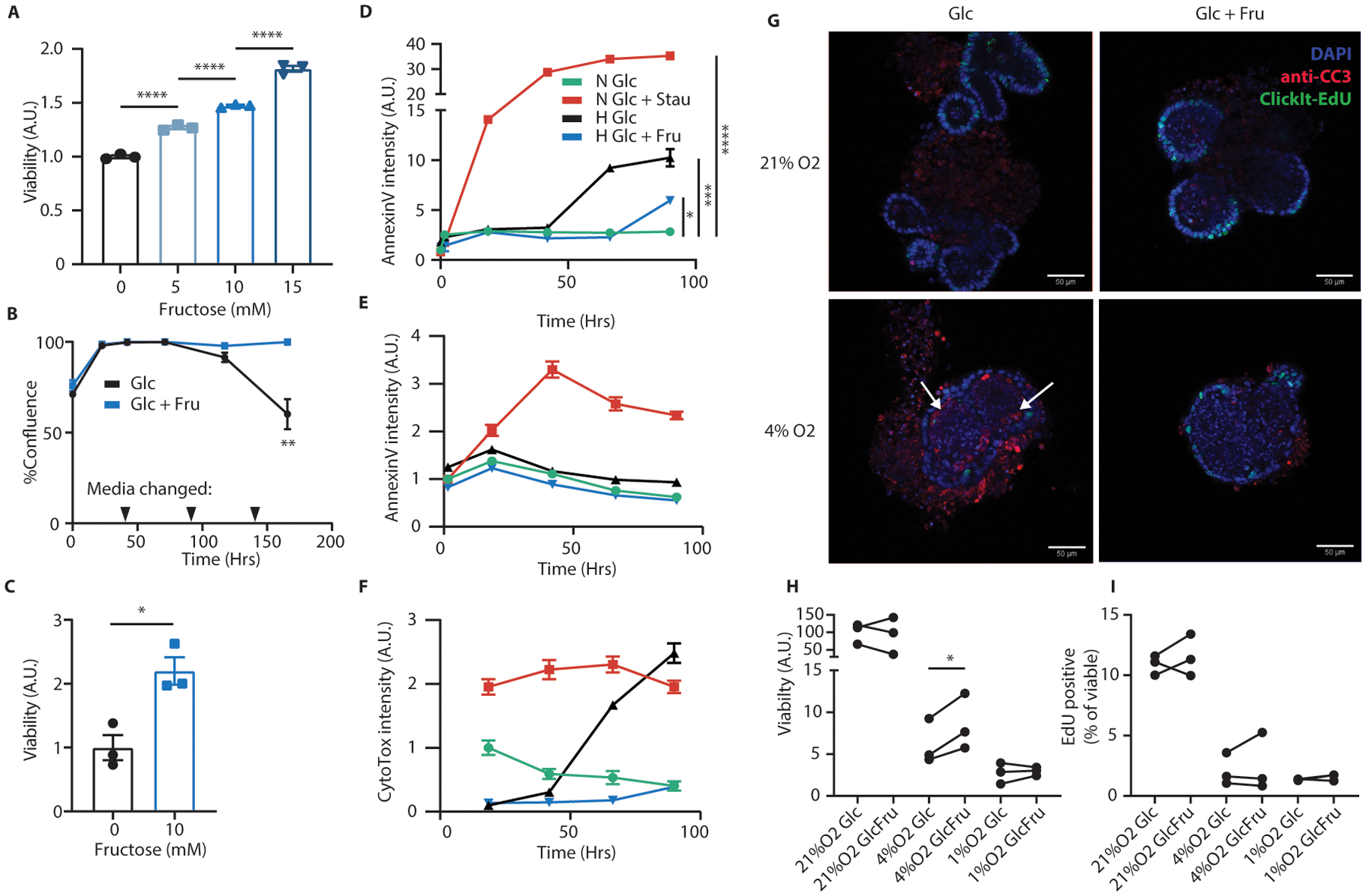

Since hypoxia is a driver of cell death in a wide variety of tissues and contexts, we next examined whether fructose could also mitigate cell death in human CRC cell lines cultured in hypoxia. The addition of fructose did not affect the cell growth rate but did improve the survival of hypoxic HCT116 and DLD1 cells (Fig. 2A, B, E.D. 4A–F). Fructose also improved the survival of hypoxic mouse intestinal organoids. Hypoxia induced intense apoptosis in the organoid cores (the morphological correspondent to the villus), which was reflected both by increased CC3 intensity and decreased viable cell population, and these changes were abrogated with fructose treatment (E.D. 4G, H). We observed no increase in organoid proliferation with fructose treatment (E.D. 4I), indicating primarily a survival benefit in this context as well.

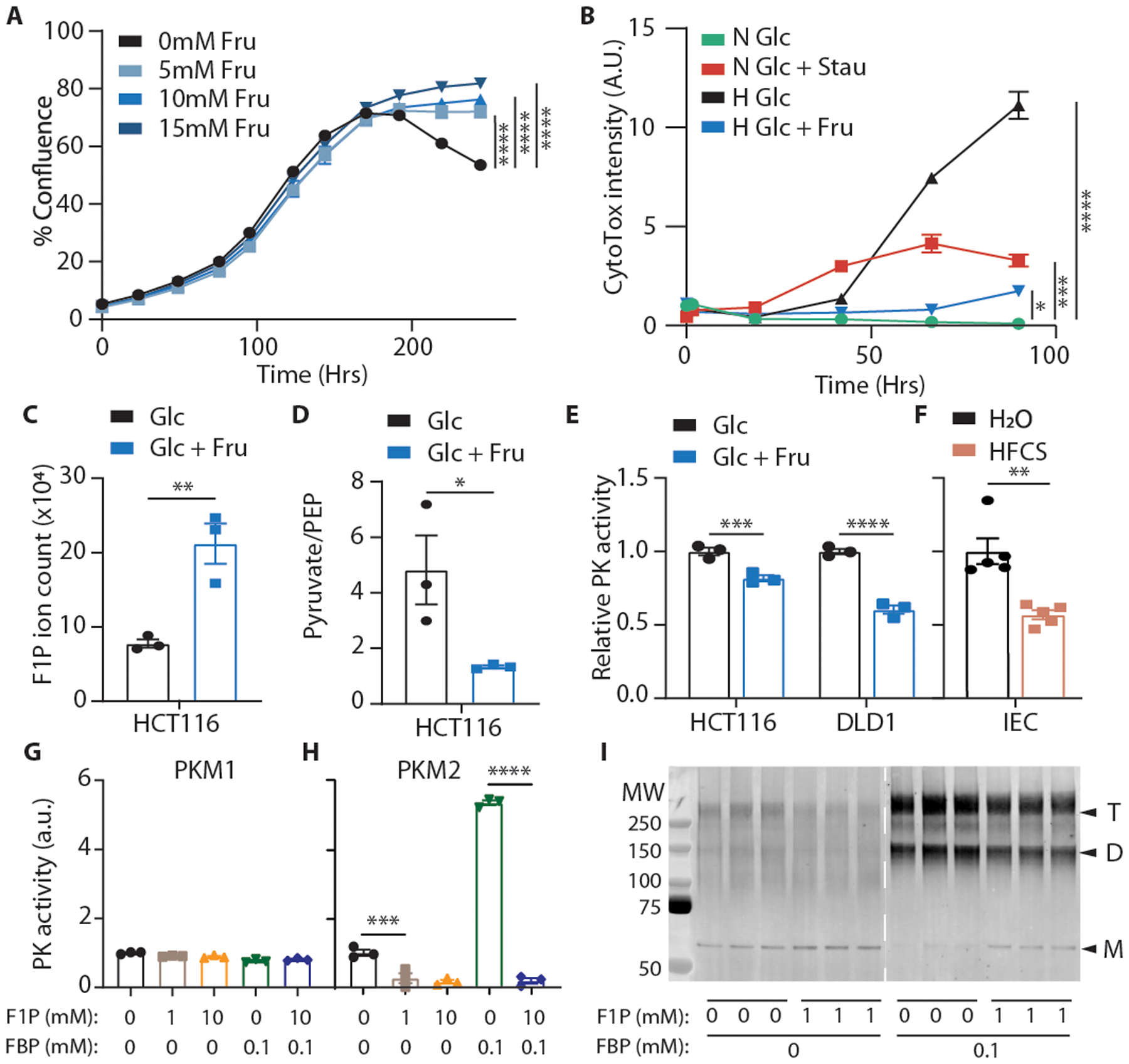

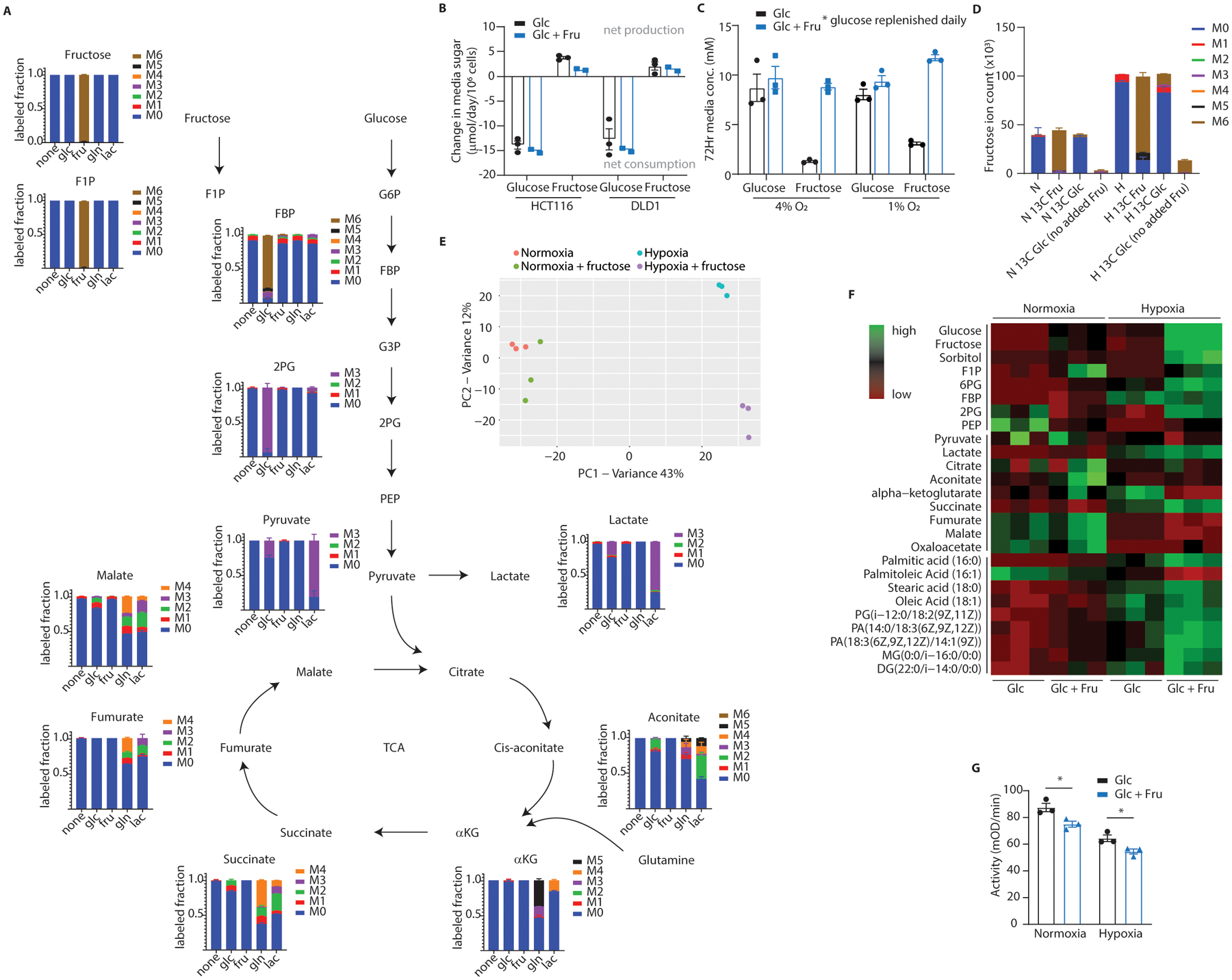

Fig. 2. Fructose metabolism enhances hypoxic cell survival and decreases pyruvate kinase activity.

(A) Confluence of HCT116 cells grown in hypoxia with varying concentrations of fructose (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (B) CytoTox viabilty dye intensity in HCT116 cells cultured in glucose media with and without fructose. Stain intensity is reported as positive area per well normalized to the initial normoxic glucose control (n = 3 biological replicates per group; “Stau”: stausporin control, “N”: normoxia, “H”: hypoxia). In these and future cell viability assays, unless otherwise noted, glucose was replenished daily (see methods). (C, D) Metabolites from hypoxic HCT116 cells quantified via LC-MS (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (E, F) Pyruvate kinase activity in hypoxic cell lysates and in intestinal epithelial lysates from mice fed the indicated diets for 4 weeks (n = 3 independent reaction wells per group; same final protein concentration in each well). (G, H) PK activity of recombinant PK isozymes pre-incubated with the indicated metabolites (n = 3 wells per group). (I) Western blot against PKM2 using recombinant PKM2 samples crosslinked with disuccinimidyl glutarate (n = 3 independent reaction wells per group; “T, D, M” indicate putative sizes of tetrameric, dimeric, and monomeric PKM2). A, B, G, H: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; C, D, F: two-sided student’s T-test; E: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; all data represent means ± S.E.M. For gel source data, see Fig. S1 in the supplement.

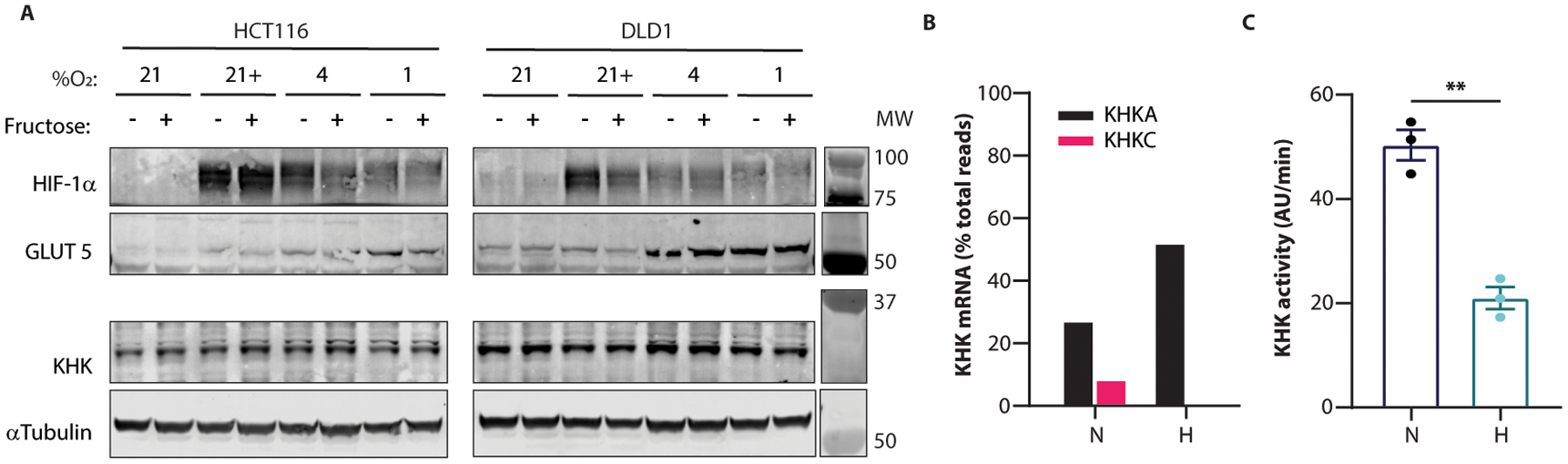

Fructose is transported into intestinal cells mainly via the sugar transporter, GLUT5, before it is phosphorylated by KHK to form fructose 1-phosphate (F1P). In human CRC cells, total KHK was consistently expressed regardless of fructose or hypoxia exposure, while the abundace of GLUT5 was induced by hypoxia (E.D. 5A). Interestingly, cobalt chloride achieved robust HIF-1α stabilization, but did not upregulate GLUT5, suggesting HIF-1α-independent expression. We also noted strong expression of KHK-A in hypoxia in human CRC cells (E.D. 5B, C) and confirmed that exogenous fructose was converted to F1P, but fructose carbons were not incorporated into downstream glycolytic intermediates (Fig. 2C, E.D. 6A), consistent with previous studies in mouse intestinal tumors16. This agreed with our findings that fructose was not depleted from the media of either human CRC cells or intestinal organoids cultured in hypoxia (E.D. 6B–D). In fact, direct fructose metabolites explained only a small portion of the distinct metabolic signature associated with fructose exposure in hypoxia (E.D. 6E, Fig. S3). Upper glycolytic intermediates, however, were elevated in hypoxic HCT116 cells and the pyruvate/PEP ratio was significantly lower, consistent with pyruvate kinase (PK) inhibition (E.D. 6F, Fig. 2D). PK is the final rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis which converts pyruvate to PEP, and the activity of the M2 isoform (PKM2) is highly sensitive to changes in the intracellular metabolome19. Moreover, PKM2 expression is high in tissues subject to hypoxia such as tumors and intestinal villi16,20. Using enzymatic assays, we confirmed PK inhibition in CRC cell lysates exposed to fructose and in intestinal epithelial cell lysates from animals fed HFCS (Fig. 2E, F, E.D. 6G).

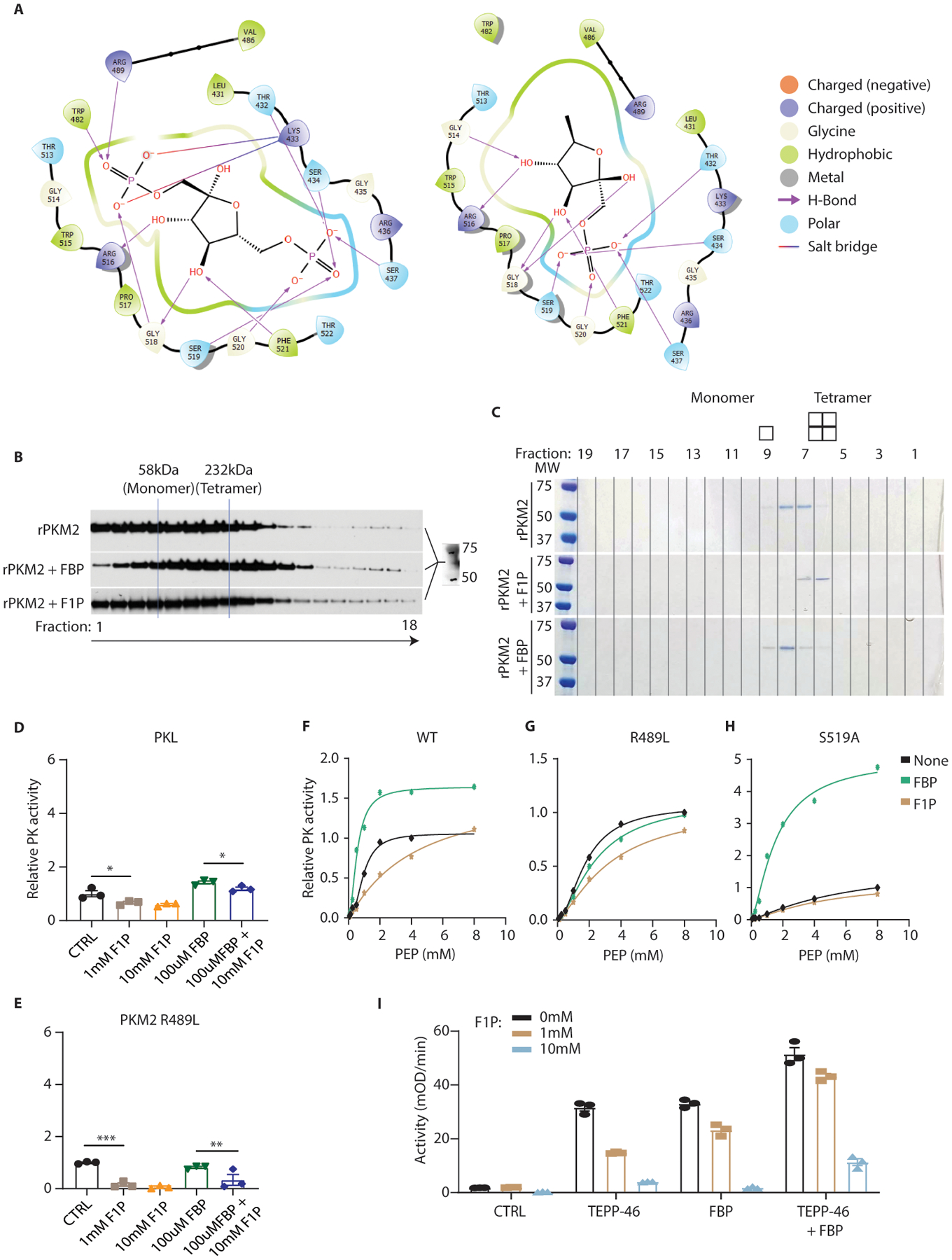

Because F1P is structurally similar to PKM2’s endogenous regulator, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate (FBP), we hypothesized that F1P might directly inhibit PKM2 activity. FBP binds tightly in a regulatory pocket critical for stabilizing PKM2 in a highly active tetramer. Docking simulations demonstrated that F1P can occupy the same pocket but lacks the outward-facing phosphate necessary to interact with an adjacent peptide loop that is critical for tetramer formation (E.D. 7A)21. Consistent with this mechanism, we found that F1P robustly inhibited PKM2 but did not inhibit PKM1, which lacks the FBP binding pocket (Fig. 2G, H)19, and this inhibition was accompanied by a decrease in the proportion of tetrameric to monomeric enzyme (Fig. 2I, E.D. 7B, C). Meanwhile PKL, an isozyme with a modified type of FBP binding pocket, was only partially inhibited by F1P (E.D. 7D). In an FBP-unresponsive mutant (PKM2 R489L)21, we still noted strong inhibition, suggesting that F1P not only competes with FBP for binding but also directly inhibits PKM2 once bound (E.D. 7E). Indeed, we found that the interaction between F1P and S519, a residue deep in the binding pocket, is critical for inhibition since mutation of this residue to alanine ablated F1P inhibition while preserving FBP activation (E.D. 7F-H). The inhibitory effects of F1P could be also be overcome by activating PKM2 at a site remote from the FBP pocket using the small molecule TEPP-46 (Fig. 3A, E.D. 7I)7.

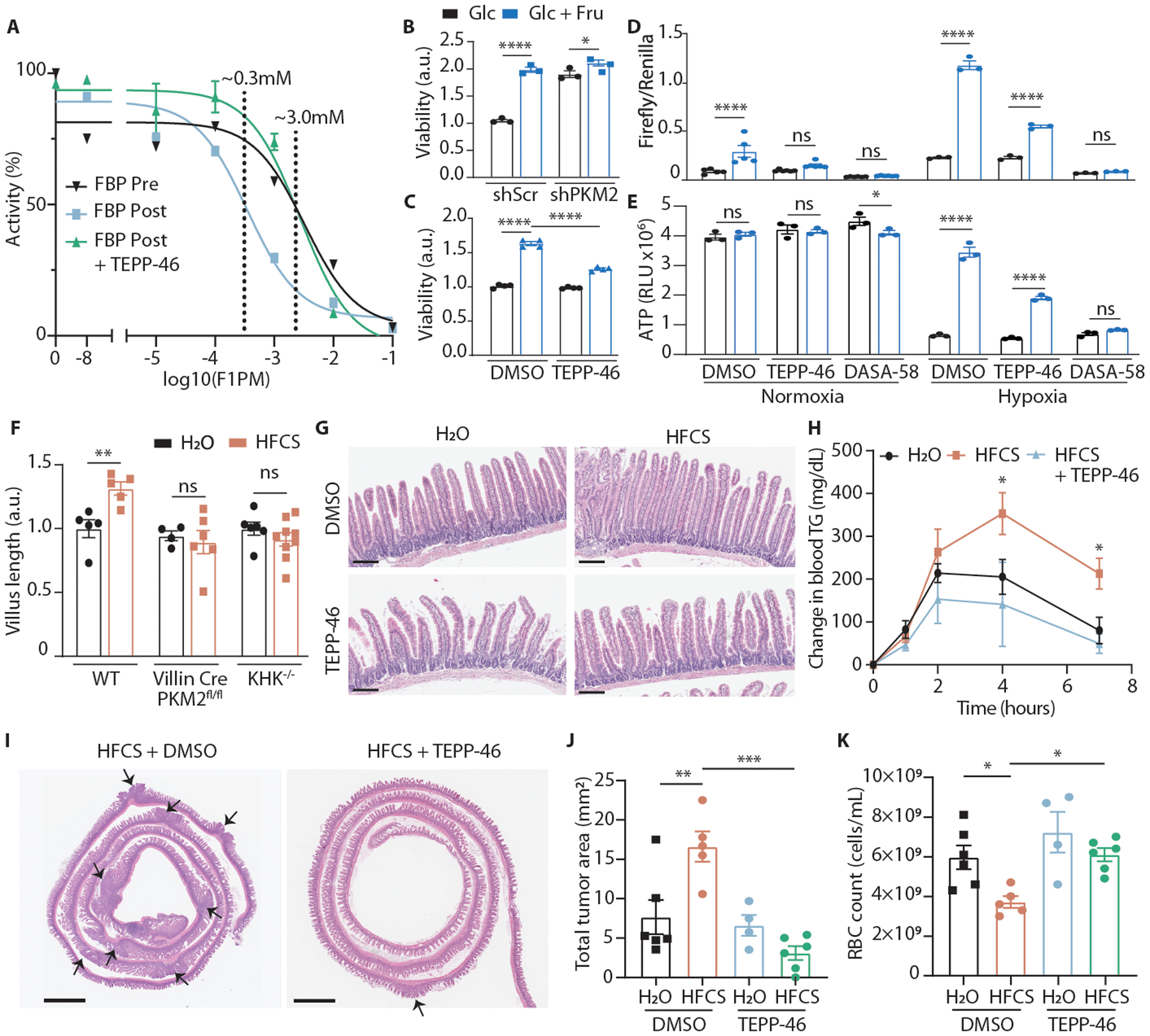

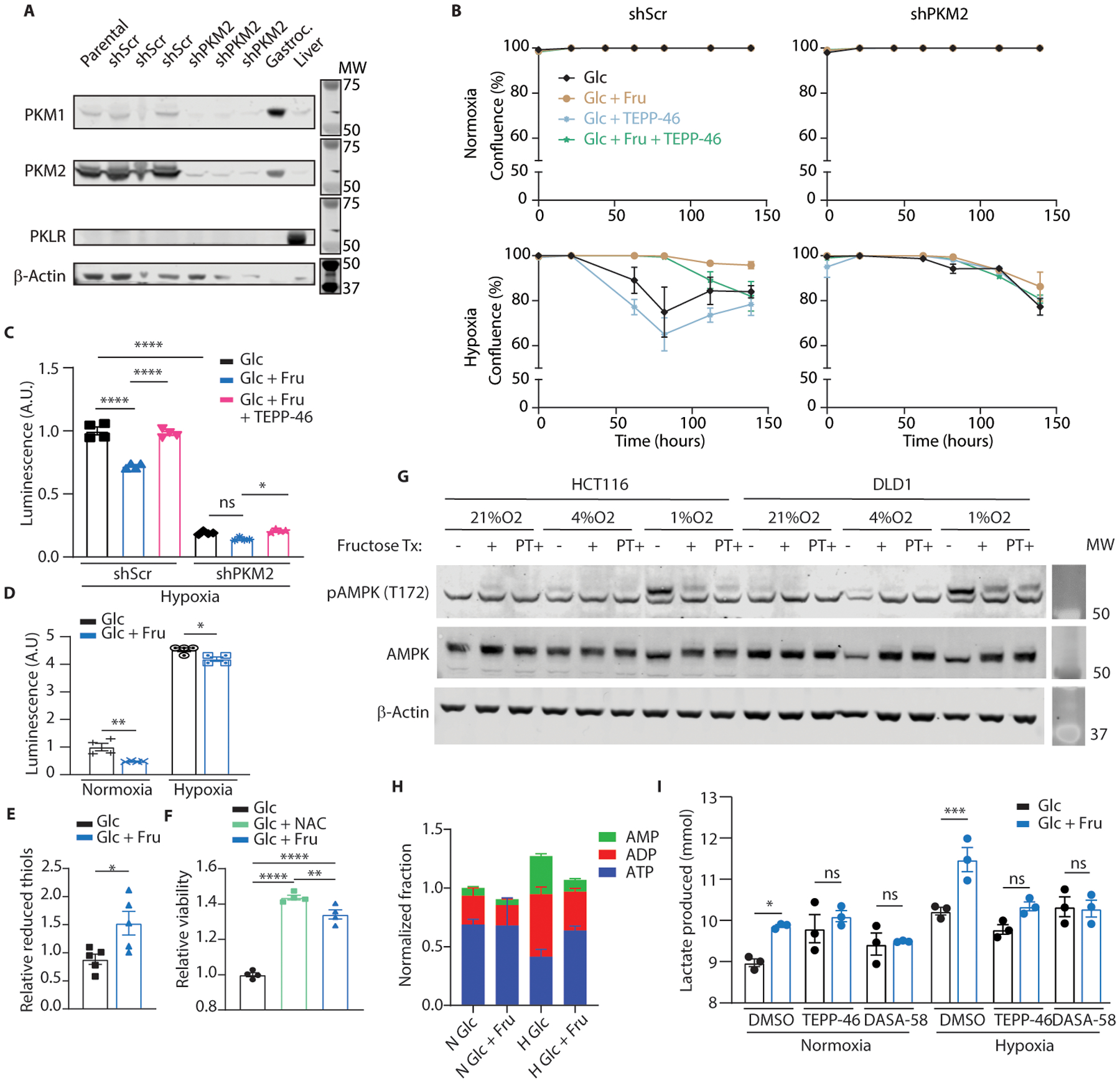

Fig. 3. PK activation diminishes fructose’s effect on hypoxia survival.

(A) PK activity of recombinant PKM2 incubated with varying concentrations of F1P. FBP with or without TEPP-46 was added either before or after F1P. IC50 with FBP pre-F1P-incubation = 3.3mM (95% CI: 1.1–9.6mM); IC50 with FBP post-F1P-incubation = 0.35mM (95% CI: 0.15–0.80mM); IC50 with FBP and TEPP-46 post-F1P-incubation = 2.7mM (95% CI: 1.7–4.4mM). (n = 2 wells per data point for FBP Pre, 4 for FBP Post, 3 for FBP Post + TEPP-46). (B) Viability of HCT116 cells virally transduced with the indicated shRNAs and cultured in hypoxia with or without fructose (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (C) Viability of HCT116 cells cultured in hypoxia with or without fructose and TEPP-46 (n = 4 biological replicates per group). (D) Relative luminesence of HCT116 cells transfected with firefly luciferase HIF-1α reporter (p2.1) and renilla luciferase constitutive reporter (pRL). Luminesence was measured after 24 hours culture in the indicated conditions (n = 6 biological replicates per group for normoxia, 3 for hypoxia). (E) ATP levels in HCT116 cells after culture as above (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (F) Relative duodenal villus length in mice after 4 weeks ad-lib H2O or HFCS. Mean villus length is reported relative to water-treated controls in each genotype (mice per group, left to right: 5|5 5|8 6|9). (G) Duodenal villi of WT mice treated for 4 weeks with the indicated diets (scale bar = 200μm). (H) Serum triglyceride (T.G.) following an oral lipid bolus in mice treated via daily oral gavage for 2 weeks (n = 8 (H2O, HFCS) and 5 (HFCS + TEPP-46) mice per group). (I) Representative intestines from APCQ1405X/+ mice treated with the indicated regimens and euthanized at 15 weeks of age. Arrows indicate tumors; scale bar = 2mm. (J) Total tumor area per histological section of mouse large and small intestine and (K) red blood cell (RBC) count at 15 weeks (mice per group, left to right: 6|5 4|6). B-F, J, K: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; H: two-sided student’s T-test at the 4 and 7Hr timepoints; ns: not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, ****p<0.0001; all data represent means ± S.E.M.

To test whether PKM2 activity could impact fructose’s effects in cells and tissues, we first generated PKM2 knock-down cells and exposed them to hypoxia in the presence or absence of fructose. In the setting of PKM2 depletion, fructose no longer improved hypoxic cell survival (Fig. 3B, E.D. 8A). Likewise, when we used TEPP-46 to activate PKM2 in cells, fructose’s effects were greatly diminished (Fig. 3C, E.D. 8B). These data suggest that PKM2 is a key mediator of fructose-induced cell survival.

The ability to change activity and conformation in response to stimuli likely explains the high expression of PKM2 in rapidly dividing tissues, which must contend with nutrient and oxygen constraints to continue their growth. In low oxygen states, the inhibition of PKM2 mitigates reactive oxygen species (ROS) to improve cell survival5. Consistent with this role, we observed that fructose reduced total H2O2 in hypoxic cells, an effect that was abrogated by PK activation and was not observed in PKM2 knock-down cells (E.D. 8C–E). The PKM2 monomer and dimer are also known to bind and transactivate HIF-1α, a key transcription factor for hypoxic adaptation22. Because F1P triggers the formation of these lower-order PKM2 units, we hypothesized that fructose would increase HIF-1α transactivation. Indeed, hypoxic and normoxic HCT116 cells exposed to fructose had increased HIF-1α transcriptional activity, a result which was abrogated by two structurally distinct PK activators22 (Fig. 3D). Moreover, HIF-1α activity correlated with intracellular ATP levels, AMPK signaling, as well as lactate production in hypoxia (Fig. 3E, E.D. 8G–I), consistent with HIF-1α’s role in rewiring cellular metabolism. In aggregate, our data identifies F1P as an inhibitor of PKM2, which then amplifies HIF-1α activity to promote hypoxic cell survival.

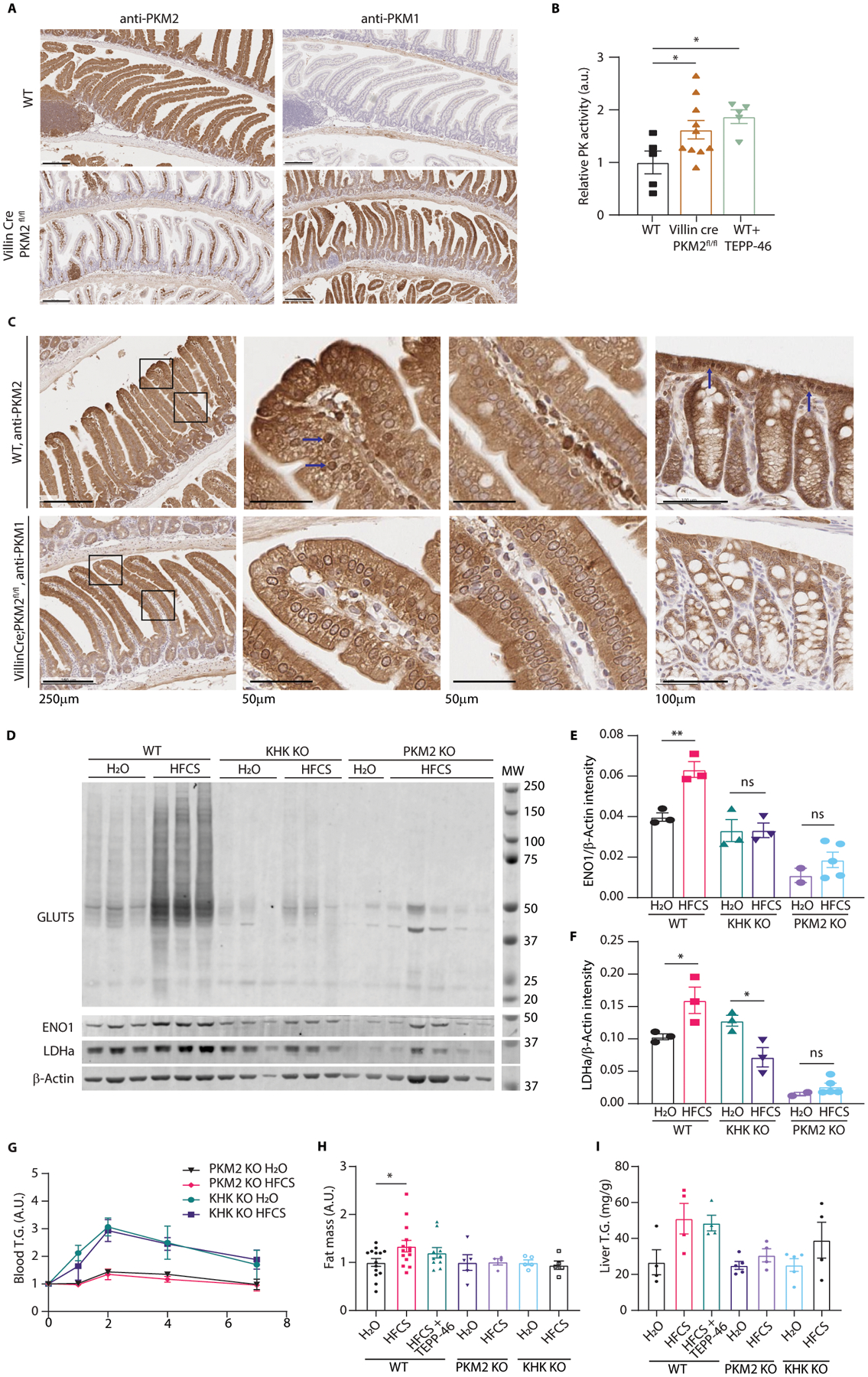

The importance of PKM2 in the physiologic response to fructose was confirmed using genetic mouse models. Selective deletion of PKM2 in IECs (Vil1Cre/+;PKM2fl/fl) strongly upregulated PKM1 and increased pyruvate kinase activity in the epithelium (E.D. 9A, B), and also altered the nuclear localization of pyruvate kinase (E.D. 9C). The villi of these mice, as well as mice lacking KHK, were short and unable to elongate in the presence of HFCS (Fig. 3F), indicating that F1P and PKM2 are both required. Furthermore, the mice deficient in PKM2 or KHK did not upregulate GLUT5 or HIF-1α target proteins (E.D. 9D–F) and were also protected from increased lipid uptake and fat accumulation following HFCS-feeding (E.D. 9G–I).

Pharmacological activation of PKM2 also greatly modified fructose’s effects in the intestine. Even with doses far below those required to maintain effective serum levels of drug (2 as oppsed to 100 mg/kg/day)7, TEPP-46-treated mice had higher intestinal PK activity (E.D. 9B) and were protected from villous elongation due to HFCS (Fig. 3G). We repeated this experiment using mice administered a once daily oral gavage of HFCS to more closely approximate typical human consumption16. In this model, HFCS-fed mice developed villous elongation extending to the ileum after only 10 days, and this could be prevented and reversed with concurrent TEPP-46 administration (E.D. 10A–C). As in the genetically altered mice, TEPP-46 protected against HFCS-induced increases in lipid absorption and fat accumulation (Fig. 3H, E.D. 9H, 10D).

Given the effects of PK activation on normal epithelial tissue, we hypothesized that this approach might also inhibit the growth of intestinal tumors. Intestinal tumors originate from IECs both in the crypt and the villus, so hypoxic stress may be a limiting factor in their development and progression23. Consistent with this theory, we observed high expression of PKM2 and other HIF-1α targets in primary human CRC tumors compared to normal adjacent epithelium (E.D. 10E, F). Additionally, the PK activity in these tumors was inhibited relative to adjacent tissue (E.D. 10G), potentially providing a hypoxia survival advantage. In mouse intestinal tumors, we found regions of hypoxia in the core and along the periphery of the tumor with many apoptotic cells, as well as upregulation of GLUT5 (E.D. 10H–O). To test if PK activation inhibits tumor growth, we fed HFCS with or without TEPP-46 to mice with a clinically-relevant, tumor-predisposing mutation in one allele of the Apc gene (APCQ1405X/+)24. In agreement with our previous findings16, HFCS led to more severe tumor burden and more profound anemia, a complication associated with more severe disease and worse survival in this model and in humans. These changes were both prevented with low-dose TEPP-46 (Fig. 3I–K, E.D. 10P–R).

Together, these findings indicate that fructose promotes hypoxic cell survival. Indeed, multiple groups spanning different fields have identified fructose metabolism as an important component of cellular oxygen sensing25,26. For example, endogenously produced fructose is critical to the survival of the naked mole-rat in hypoxic burrows and in mouse cardiomyocytes following ischemia, yet the mechanisms behind these interactions are poorly understood27,28. The finding that fructose-derived F1P inhibits PKM2, an enzyme critical in hypoxia adaptation5,6, offers additional insight into these observations. Given its relative scarcity in systemic circulation, endogenously-produced fructose could serve as a highly specific signal for reprogramming cellular metabolism in response to hypoxia—a mechanism we propose is leveraged (and targetable) when tissues such as intestinal villi and tumors are exposed to exogenous fructose. Additionally, we find that the consequence of intestinal cell survival is an expansion of the intestinal surface area, which improves nutrient absorption. This finding may help to explain the growth-promoting effects of fructose in breast-fed infants, the increase in adiposity that occurs in fruit-foraging hibernating animals, and the obesogenic properties of a Western-style diet29,30.

Methods

Animals and Diets

6–8 week old male and female C57B6/J, C57B6/NJ, FVB, and BALBC mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory. Mixed-background male and female “G5H” mice were kindly shared by Andrew Dannenberg. Vil1Cre/+; Pkm2fl/fl mice were generated from crossing B6.Cg-Tg(Vil1Cre/+)997Gum/J (stock # 004586) and B6;129S-Pkmtm1.1Mgvh/J (stock # 024048) mice purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. KHK−/− mice lacking both KHK-A and KHK-C on the C57BL/6 background were kindly shared by Dr. Bonthron at University of Leeds at UK and Drs. Lanaspa and Johnson at University of Colorado31. APCQ1405X/+ (“APC1405”) mice on the C57BL/6N background were kindly shared by Dr. Lukas Dow at Weill Cornell Medical College24.

Unless otherwise indicated, all wild-type experiments use male C57BL/6J mice between the ages of 8 and 16 weeks. All genetically-modified models (Vil1Cre/+; Pkm2fl/fl , KHK−/−, APCQ1405X) were equally weighted mixes of males and females between 10 and 20 weeks of age at sacrifice.

Mice were maintained in temperature- and humidity-controlled specific pathogen-free conditions on a 12-hour light/dark cycle and received rodent chow (PicoLab Rodent 20 5053 LabDiet, St. Louis, MO) and free access to drinking water. High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) was prepared by combining D-(+)-Glucose (Millipore Sigma, Cat. #G8270) and D-(−)-Fructose (Millipore Sigma, Cat. #F0127) in a 45:55 ratio using tap water. Match Purina 5053 fructose-free control (Cat. D17011901), High-Fat (Cat. D19090601), and High-Fat/Sucrose (Cat. D19090602) diets were purchased from Research Diets (New Brunswick, NJ). Age-matched cohorts were treated with HFCS either by ad libitum delivery in the drinking water (25% HFCS in tap water) or by once-daily oral gavage (45 mg glucose + 55 mg fructose, total 400 μl in tap water). Control mice were treated with tap water in the water bottle or 400 μl of tap water via daily oral gavage.

For drug trials, TEPP-46 (Millipore Sigma, Cat. #505487) dissolved in DMSO was added to the drinking water to a final concentration of 7.5μg/mL such that the total daily dose for a 30g mouse consuming 8mL of water daily was 2mg/kg. Fluid consumption was monitored weekly to confirm that similar amounts of drug were consumed in each cage. Control animals received equal volumes of DMSO in the drinking water. For oral gavage, TEPP-46 was administered at 2mg/kg in HFCS or water. Controls received an equal volume of DMSO dissolved in HFCS or water.

Male and female APC1405 animals in a 1:1 ratio were initiated on their respective diets/treatments at 6 weeks and euthanized at 15 weeks of age. Other animals receiving treatment via the water bottle or diet were initiated on treatment between 6–15 weeks of age and were sacrificed after 4–6 weeks of intervention. Animals receiving oral gavage treatment were sacrificed after 10–14 days of once-daily gavage. After sacrifice, tissues and intestines were harvested, split into 5 sections (4 of equal size for small intestine and 1 for the colon), swiss-rolled, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Cat. SC-281692, Dallas, Tx) over night at 4 degrees Celsius. Tissues were then transferred to 70% ethanol and shipped to Histowiz (Brooklyn, NY) for paraffin embedding, mounting, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E staining, and slide scanning at 40X magnification.

All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Weill Cornell Medical College and maintained as approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Weill Cornell Medicine (NY) under protocol number 2012-0074. Animals were regularly monitered for lethargy, gross weight loss, palor, and rectal prolapse. Animals that exhibited greater than 20% weight loss from peak weight, had RBC counts below 1E9/mL as determined from tail vein sampling, or had rectal prolapse were sacrificed. These limits were never reached in our experiments.

Histological analysis

Scanned H&E images of small intestine from each trial were downloaded from Histowiz (Brooklyn, NY) as ScanScope Virtual Slide (SVS) files and divided into separate files for duodenum, proximal jejunum, distal jejunum, and ileum.

For manual villi analysis, each intestinal segment was further divided into 4 quadrants and 10 intact villi were measured from the distal edge of the crypt to the villi apex in each quadrant. A mean villus length was then calculated for the entire bowel segment.

For semi-automated analysis, SVS files were opened in ImageJ (Bethesda, MD) and the length of the intestinal section was measured using the freehand measurement tool (Fig. S1A). Images were then stain-normalized to a standard H&E image using a custom MATLAB (release 2019b, Natick, MA) script employing the method described in Macenko et al.32. A random image from the set was then loaded into the MATLAB Color Thresholder33 and values were manually selected within the hue-saturation-value (HSV) color space such that the intestinal villi, but not other tissues such as lymph nodes or pancreas, were selected (Fig. S1B). These values were entered into a batch processing script which performed this villi segmentation on every image in the set. This resulted in binary images of pixels identified as villi and pixels identified as non-villi. The pixels occupied by villi were converted to area in μm2 using the embedded scale from the original SVS file. The villi area was divided by the bowel segment length to yield the average thickness of the intestinal villi layer. This measurement correlated well with manual measurements of villi length and provided improved intra-operator or inter-operator variation (Fig. S1C–G).

Polyp number and area were determined from SVS files analyzed using ImageJ software in a blinded manner.

Body composition, glucose tolerance, lipid tolerance

Body Mass, Fat mass (FM) and fat-free mass (FFM) were measured and calculated using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) using an EchoMRI Body Composition Analyzer (Houston, TX) as previously described34. Visceral fat/white adipose tissue was assessed by measuring the weight of the gonadal white adipose depot.

To assess lipid tolerance, mice were fasted for 8 hours then administered 400 μL olive oil via oral gavage (Whole Foods, Extra Vigrin – Cold Processed). Tail blood serum was collected over time and measured via enzymatic assay (see below). Mice resumed their diets after completion of the above testing and recovered for at least 48 hours prior to sacrifice. To assess lipid absorption after blocking endogenous lipases, mice were treated with poloxamer 407 as previously described35. Briefly, mice were fasted and then given an I.P. injection of poloxamer 407. 1 hour later TG was measured from serum and the mice were given a 400 μL oral olive oil bolus. 2 hours later, serum triglyceride levels were measured again.

Comprehensive metabolic monitoring

Metabolic monitoring was conducted using a Promethion Metabolic Screening System (Promethion High-Definition Multiplexed Respirometry System for Mice; Sable Systems International, Las Vegas, NV, USA) as previously described36. Briefly, rates of oxygen consumption (VO2) and carbon dioxide production (VCO2) were acquired by indirect calorimetry with a sampling frequency of 1s. Respirometry values were determined every 5 min; the dwell time for each cage was 30s, with baseline cage sampling frequency of 30s occurring every four cages. Values of respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were calculated as ratios of VCO2 to VO2. Food intake and body mass were recorded continuously by gravimetric measurements within the cages. Physical activity was determined according to beam breaks within a grid of infrared sensors built into each cage. Energy expenditure was calculated using the Weir equation (Energy expenditure = 3.941 kcal/L × VO2 + 1.106 kcal/L × VCO2)37. Energy expenditure is displayed as the total kcal per specified periods of time, with values adjusted by ANCOVA for body mass or corrected body mass using VassarStats.

Fecal bomb calorimetry

Nutrient absorption was quantified as described38. Fecal pellets were collected from cage bottoms over 24 h during which mice were single caged and housed at 22°C. Fecal pellets were dehydrated for 48 h and then subjected to bomb calorimetry using a Parr 6725 Semimicro Calorimeter.

Immunohistochemistry, Immunofluorescence

For BrdU tracing experiments, 100uL of BrdU (100 mg/kg, Millipore Sigma, Cat. #B5002) dissolved in sterile PBS (Corning, Cat. #21-040-CV) was injected intraperitoneally 72 hours prior to animal sacrifice as previously described39. For BrdU-EdU dual-labeling experiments, BrdU was injected 48 hours prior and EdU (10 mg/kg, Millpore Sigma, Cat. #900584) was injected 24 hours prior to animal sacrifice. Pimonidazole, a 2-nitroimidazole that is reduced in hypoxic environments and then binds to thiol-containing proteins, was injected intraperitoneally 90 minutes prior to sacrifice as per manufacturer instructions40 (Hypoxyprobe, Cat. #HP1–100Kit, Burlington, MA).

Immunohistochemistry was performed upon formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues. Slides were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated in a graded ethanol series and water. Antigen retrieval was performed with 0.01 M citrate, pH 6.0 buffer by heating the samples in a pressure cooker for 10 minutes. Sections were blocked with avidin/biotin blocking for 30 minutes. Sections were incubated with primary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight at 4C, followed by 60 minutes incubation with biotinylated anti-rabbit IgG (goat, Vector Laboratories, Cat. # PK6101, Burlingame, CA, dilution 1:500) at room temperature for rabbit primaries. Mouse primaries on mouse tissues were assayed using a Mouse on Mouse Basic kit (Vector laboratories, Cat. # BMK-2202) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Detection was performed with the DAB detection kit (Vector Laboratories, Cat. #SK-4100) according to manufacturer’s instructions, followed by counterstaining with hematoxylin and cover slipping with Permount (Fisher Scientific, Cat. # SP15-500).

Immunofluorescence was performed upon formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues using the same method as above up to the application of the primary antibodies, which were incubated together. Slides were then washed in PBS and incubated with alexa-fluor 488 and alexa-fluor 568 conjugated secondary antibodies (ThermoFisher, A21202 and A10042), per the manufacturer’s instructions. Slides were then washed and mounted with the TrueVIEW autofluorescence quenching kit with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, SP-8400-15) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Organoids were stained as described previously41.

Antibodies used for immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence included Ki-67 (rabbit, Abcam Cat #ab15580, dilution 1:500), cleaved caspase-3 (rabbit, Cell Signaling Technologies (CST) Cat. # 9661, dilution 1:200), PKM1 (rabbit, CST Cat. # 7067, dilution 1:600), PKM2 (rabbit, CST Cat. # 4053, dilution 1:800), BrdU (mouse, Santa Cruz Biotechnology (SC) Cat. # sc-32323, dilution 1:250), and Pimonidazole-adducts (mouse, Hypoxyprobe Inc. Cat # Mouse-Mab, dilution 1:50). SLC2A5 EdU was visualized using ClickiT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Imaging Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, # C10340) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For BrdU tracing analysis, the total villi length and the length from crypt to the BrdU-labeled cells furthest from the crypt were measured from 40–50 villi in the duodenums of each mouse using ImageScope software (Leica Biosystems, Buffalo Grove, IL). For BrdU-EdU dual-labeled tracing, the differences between the lengths of BrdU and EdU-stained areas was divided by the time between these two injections.

TUNEL staining was performed on formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by Histowiz (Brooklyn, NY).

Imaging

Images of fluorescent-stained sections were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 880 Laser Scanning Confocal Microscope. Raw .tif files were processed using FIJI (Image J) and/or Photoshop CS (Adobe Systems Inc.) to create stacks, adjust levels, and/or apply false coloring.

Biochemical analysis

For measurement of hepatic triglyceride, frozen liver was weighed and digested in 6 volumes of alcoholic KOH (2:1 EtOH to 30% KOH) at 60°C until the tissue was completely dissolved. 500μL of digest was added to 540μL of 1M MgCl2 and mixed well. After a 10-minute incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged for 30 minutes at maximum speed. The supernatant was aspirated into a new tube and glycerol content was measured using calorimetric assay (Stanbio, Boerne, TX). This assay kit was also used to measure serum triglyceride.

Glucose and fructose concentration in cell culture media were measured with the EnzyChrom glucose assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Cat. #EBGL-100, Hayward, CA) and EnzyChrom fructose assay kit (BioAssay Systems, Cat. #EFRU-100). For lactate determination, a previously described spectrophotometric enzymatic assay was adapted for 96-well plates42.

Pyruvate kinase (PK) activity was measured in recombinant protein and cell/tissue lysates in the presence of the indicated allosteric activators or small molecules by a previously described, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)-coupled reaction where phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) is converted by PK to pyruvate, which is then rapidly converted to lactate by LDH43. LDH consumes NADH and this rate of change was measured using a microplate spectrophotometer (BMG Labtech). Each allosteric regulator was tested in varying concentrations of PEP and the resulting graph of reaction rate vs. [PEP] was fitted to a substrate velocity curve to derive kinetic parameters under each condition. Substrate–velocity curves were plotted using Prism software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). To calculate % maximal PK activity, activity was measured in tissue lysates before and after incubation for 1 hour at 37C with 1mM FBP (>100X AC50) and the ratio of initial vs activated activity was calculated. Unless otherwise mentioned, PEP concentration in the final reaction was 0.5mM.

Ketohexokinase (KHK) activity was measured using a PK and LDH-coupled reaction as previously described44, with volumes adjusted for the 96-well plate format. Pyruvate and ADP were used as positive technical controls. Fructose concentration was 10mM in each reaction.

Cell lines, cell culture, virus preparations, transfections, culture additives

HCT116 and DLD1 cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured in DMEM (Corning, Cat. #10-013-CV) supplemented with 10% dialyzed fetal bovine serum (dFBS) and 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37C/5% CO2 unless otherwise stated. For assays not starting at confluence, the initial concentration of glucose was 25mM. Cells were tested every 2 months for mycoplasma contamination. Hypoxia treatments were performed using a Forma Series 3 Water Jacketed CO2 Incubator (ThermoFisher, Waltham, MA). O2 was set to 2–4% depending on the media meniscus height using previously described calculations45 to ensure consistent cellular oxygen deficit. Any manipulations to cells requiring more than 5 minutes exposure to ambient O2 were performed in a InvivO2 400 hypoxia workstation set to the appropriate oxygen level (The Baker Company, Sanford, ME).

For all hypoxia treatments the media were supplemented to 10 mM with HEPES buffer (Corning, Cat. #25060CI). High cell density was defined as a seeding density of 1,000 cells per mm2. Experiments were performed in 6-well, 12-well, or 48-well plates using 3 ml, 2 ml, and 400uL of media, respectively. 96 well plates were avoided due to large meniscus effects on the media height in this small well format.

Glucose consumption rates in hypoxia for HCT116 and DLD1 cells were derived using media samples from two different timepoints from confluent cells cultured in hypoxia. A known number of cells were plated the night before the experiment in 12-well plates, and confluence was confirmed the next day. At the start of the experiment the growth media was aspirated, and the cells were gently washed with warm PBS. Then, fresh DMEM with or without 10mM fructose was added to the culture dishes. Samples from the initial media were then frozen at −20C. 48 hours later, media was collected from each well and frozen at −20C. Media samples were subsequently tested for sugar content via enzymatic assay, and the difference in sugar concentration between the final and initial timepoints was calculated and divided by the time between timepoints to establish a rate of decrease. This was then divided by the number of cells plated to calculate consumption per 106 cells. Lactate production was calculated similarily using initial and final media samples.

For experiments plated at confluence lasting longer than 24 hours, cells were plated in 10mM glucose and glucose was replenished at a rate of 15μmol/day/106 initial cells unless otherwise noted. Cells used for metabolite labeling were plated at confluence in media with 10mM glucose +- 10mM fructose. After 24 hours, the cells were gently washed with warm PBS and given reduced-nutrient DMEM (Corning, Cat. # 17-207-CV) supplemented with 5mM glucose, 0.5mM sodium pyruvate, 10mM lactate, 1mM glutamine, and 10% dFBS to better simulate the tumor microenvironment during the final 8 hour labeling period46.

pLKO-shPKM2 was a gift from Dimitrios Anastasiou (Addgene, plasmid #42516) and Scramble shRNA was a gift from David Sabatini (Addgene, plasmid #1864). Lentiviruses were produced in 293T cells by co-transfection of plasmids expressing gag/pol, rev and vsvg with the respective pLKO. Selection was achieved with puromycin for at least 4 days. p2.1 and pRL-SV40 were procured from Addgene (Addgene, plasmids #27563 and #27163) and used as previously described22. Luciferase and renilla activity were detected using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Cat. #E1910) per the manufacturer’s instructions. TEPP-46 (Millipore Sigma, Cat. #505487) was used at 1 μM and 50μM in recombinant and cell-culture experiments respectively, unless otherwise stated. DASA-58 (MedChemExpress, Cat. # HY-19330), was used at 50μM. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC, Millipore Sigma, Cat. #A9165) was diluted in media, pH balanced to 7.4, and used at 2.5mM.

Cell confluence, viability assays, thioltracker, ROS

Cell confluence, Annexin V Green (Essen BioScience, Cat. # 4642, Ann Arbor MI), and Cytotox Red (Essen BioScience, Cat. # 4632, Ann Arbor MI) measurements were conducted using an IncuCyte ZOOM Live Cell Analysis System (Essen BioScience, Ann Arbor MI) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For trypan blue measurements, cells were trypsinized for 3 minutes at 37C and neutralized in complete media. Resuspended cells were mixed 1:1 with Trypan Blue Solution (Millipore Sigma, Cat. #T8154) and analyzed on a Cellometer Auto T4 bright field cell counter (Nexcelom Bioscience, Lawrence, MA). For measurements of viability in adherent cells, the Cell Counting Kit-8 (Dojindo Molecular Technologies, Cat. #CK04-05, Washington D.C.) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

For measurement of reduced thiols, confluent cell culture plates were incubated in hypoxia in reduced-nutrient DMEM (Corning, Cat. # 17-207-CV) supplemented with 10% dFBS and 10mM of glucose or 5mM of glucose and 5mM of fructose. After 24 hours, ThiolTracker Violet (Life Technologies, Cat. #T10095, Carlsbad, CA) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions at 10μM and plates were analyzed on a Synergy Neo 2 plate reader (BioTek Instruments, Winooski, VT).

Total cell ROS measurements were performed using the ROS-Glo H2O2 assay (Promega, Cat. #G8820) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Values from normoxic and hypoxic plates were compared after correcting for cell-independent changes in ROS-Glo measurements using wells containing only culture media.

ATP measurements were acquired using CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Viability Assay (Promega, Cat. #G7570) per the manufacturer’s instructions.

Isolation and Culture of Intestinal Organoids

Isolation, maintenance, and staining of mouse intestinal organoids was performed as described previously47. For isolation, 15 cm of the proximal small intestine was removed and flushed with cold PBS. The intestine was then cut into 5-mm pieces, vigorously resuspended in 5 mmol/L EDTA-PBS using a 10-mL pipette, and placed at 4°C on a benchtop roller for 10 minutes. This was then repeated for a second time for 30 minutes. After repeated mechanical disruption by pipette, released crypts were mixed with 10 mL DMEM Basal Media [Advanced DMEM/F12 containing penicillin/streptomycin, glutamine, 1 mmol/L N-acetylcysteine containing 10 U/mL DNAse I (Roche, 04716728001), and filtered sequentially through 100- μm and 70-μm filters. FBS (1 mL; final 5%) was added to the filtrate and spun at 1,200 rpm for 4 minutes. The purified crypts were resuspended in basal media and mixed 1:10 with Growth Factor Reduced (GFR) Matrigel (BD Biosciences, 354230). Forty microliters of the resuspension was plated per well in a 48-well plate and placed in a 37°C incubator to polymerize for 10 minutes. Small intestinal organoid growth media (250 μL basal media containing 50 ng/mL EGF (Invitrogen, PMG8043), 50nM LDN-193189 (Selleck Chemicals, S2618), and 500 ng/mL R-spondin (R&D Systems, 3474-RS-050)) was then laid on top of the Matrigel. For subculture and maintenance, media were changed on organoids every two days and they were passaged 1:4 every 5 to 7 days. To passage, the growth media was removed and the Matrigel was resuspended in cold PBS and transferred to a 15-mL Falcon tube. The organoids were mechanically disassociated using a P1000 or a P200 pipette and pipetting 50 to 100 times. Seven milliliters of cold PBS was added to the tube and pipetted 20 times to fully wash the cells. The cells were then centrifuged at 1,000 rpm for 5 minutes and the supernatant was aspirated. The cells were then resuspended in GFR Matrigel and replated as above. For freezing, after spinning the cells were resuspended in basal media containing 10% FBS and 10% DMSO and stored in liquid nitrogen indefinitely.

For hypoxic organoid experiments, organoids from each independent line were dissociated and plated at a uniform density. After 2 days, the growth media was changed to glucose-free basal media supplemented with 10mM glucose and 10mM fructose, where indicated, and organoids were placed in normoxia, 4%O2, or 1%O2 conditions for 60 hours at 37C. Every 24 hours the concentration of glucose in the growth medium of each organoid well (3mL total media volume) was increased by 5mM using sterile 1M glucose solution in a sealed hypoxia workstation. At the end of the hypoxic culture period, the media was innoculated with EdU at 10 μmol/L and organoids were returned to hypoxia to incubate for another 6 hours. Then, media samples were taken and frozen for later analysis of glucose and fructose depletion via enzymatic assay. Finally, the organoids were either dissociated and analyzed via flow cytometry or fixed in-situ and analyzed via confocal microscopy.

Flow Cytometry

Organoid EdU flow cytometry was performed using the ClickiT Plus EdU Alexa Fluor 647 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, # C10634). Each well of a 6-well plate was broken up by pipetting vigorously 50 times in 1 mL PBS, then diluted in 5 mL of PBS. Cells were pelleted at 1,100 rpm × 4 minutes at 4°C, then resuspended in 50 μL TrypLE and incubated at 37°C for 5 minutes. Five milliliters of PBS was then added to inactivate the TrypLE, and cells were pelleted. Cells were resuspended in 250 μL of 1% BSA in PBS, transferred to a 1.7-mL tube, and then pelleted at 3,000 rpm × 4 minutes. Cells were then stained with Live/dead fixable green viability dye (ThermoFisher, L34969) per the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells were then resuspended in 100 μL Click-iT fixative, and processed as instructed in the Click-iT Plus EdU protocol (starting with Step 4.3). Wash and reaction volumes were 250 μL. Upon completion of staining, all cells from each well were resuspended in 250 μL 1% BSA in PBS and 200 μL of this suspension was analyzed using an Attune NxT flow cytometer (ThermoFisher). Viable and proliferating cells were identified by the gating strategy depicted in Fig. S4.

Primary Human Tumor Samples

Frozen primary human colon tumor and matched normal epithelium were obtained after informed consent from the WCMC Digestive Disease Registry, a protocol approved by the Weill Cornell IRB. No protected health information was provided to the research team. Following resection, tissue samples were immediately embedded in optimal cutting temperature compound and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tumor areas were identified by a board certified pathologist and six 2mm cores were obtained from the frozen block. Protein was extracted from the cores as described below.

Cell lysis, immunoblotting

Tissues or pelleted cells were snap-frozen in a liquid nitrogen bath and stored at −80C until further processing. Lysis was performed in PK lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 1% Igepal-630) supplemented freshly prior to usage with protease inhibitors [10 μg/ml phenymethylsulfonyl fluoride, 4 μg/ml aprotinin, 4 μg/ml leupeptin, and 4 μg/ml pepstatin (pH 7.4)].

For immunoblotting, lysates were mixed with SDS-PAGE loading buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 1% w/v SDS, 2.5% glycerol, 0.001% w/v bromophenol blue and 143 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and heated to 70C for 10 minutes. Samples were separated by electrophoresis on 4–12% NuPAGE Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and transferred to 0.45μm PVDF membranes with wet transfer cells (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). After 1 h of blocking with Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 (TBST) containing 5% (w/v) BSA, membranes were incubated overnight at 4° C with primary antibody in 5% BSA followed by a TBST wash and the appropriate secondary antibody (1:6000) for 1h at room temperature. Signal was detected using an Odyssey CLx imaging system (LI-COR).

Antibodies

In alphabetical order [target (species, manufacturer, catalog number, western blot dilution, IHC dilution (if applicable))]: ACC (Rb, CST, 3676, 1:1000), pACC(s79) (Rb, CST, 3661, 1:1000), Aldolase A (Rb, CST, 8060, 1:1000), Aldolase B (Rb, Abcam, 153828, 1:1000, 1:1000), AMPKa (Rb, CST, 2532, 1:1000), pAMPK (t172) (Rb, CST, 2535, 1:1000), α-tubulin (Ms, CST, 3873, 1:1000), β-Actin (Ms, Abcam, 6276, 1:1000), BCL-2 (Rb, CST, 2876, 1:1000), BCL-XL (RB, CST, 2764, 1:1000), BrdU (IIB5) (Ms, SC, sc-32323, 1:1000, 1:250), Cleaved caspase-3 (Rb, CST, 9661, 1:1000, 1:200), Enolase 1 (Rb, CST, 3810, 1:1000), GLUT5 (Ms, Invitrogen, MA1-036, 1:1000), GLUT5 (Ms, SC, 271055, 1:1000), Hif1a (Rb, CST, 36169, 1:1000), HK1 (Rb, CST, 2024, 1:1000), HK2 (Rb, CST, 2867, 1:1000), Hypoxyprobe (Ms, HP, Mouse-Mab, 1:1000, 1:50), KHK (Rb, Abcam, 154405, 1:1000, 1:500), KHK A (Rb, SAB, 21708, 1:1000, 1:500), KHK C (Rb, SAB, 21709, 1:1000, 1:500), LDHA (Rb, CST, 2012, 1:1000), MCL-1 (Rb, CST, 5453, 1:1000), pBad (S136) (Rb, CST, 4366, 1:1000), PDH (Rb, CST, 3205, 1:1000), pPDH (s293) (Rb, CST, 31866, 1:1000), PKLR (Rb, Abcam, 171744, 1:1000), PKM1 (Rb, CST, 7067, 1:1000, 1:600), PKM2 (Rb, CST , 4053, 1:1000, 1:800). CST: Cell Signaling Technologies; SC: Santa Cruz Biotechnology; HP: Hypoxyprobe; SAB: Signalway Antibody.

Metabolomics analysis

Polar metabolites were extracted from cell pellets using a 40:40:20 mixture of ice-cold acetonitrile:methanol:water with 0.1M formic acid. Samples were then centrifuged at 4 °C for 15 minutes at 14,000 rpm. Supernatants were then evaporated and used for LC/MS.

Quantitative metabolome analysis was performed as described previously16. Briefly, aqueous tissue extracts were separated via liquid chromatography on an Agilent 1290 Infinity LC system by injection of 10 μL of filtered extract through an Agilent ZORBAX Extend C18, 2.1 × 150 mm, 1.8 μm (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) downstream of an Agilent ZORBAX SB-C8, 2.1 mm × 30 mm, 3.5 μm (Agilent Technologies) guard column heated to 40°C. Solvent A (97% water/ 3% methanol containing 5 mM tetrabutylammonium hydroxide (TBA) and 5.5 mM acetic acid) and Solvent B (methanol containing 5 mM TBA and 5.5 mM acetic acid) were infused at a flow rate of 0.250 mL/min. The 24-minute reverse phase gradient was as follows: 0–3.5 min, 0% B; 4–7.5 min, 30% B; 8–15 min, 35% B; 20–24 min, 99% B; followed by a 7-minute post-run at 0% B. Acquisition was performed on an Agilent 6230 TOF mass spectrometer (Agilent Technologies) employing an Agilent Jet Stream electrospray ionization source (Agilent Technologies) operated at 4000 V Cap and 2000 V nozzle voltage in high resolution, negative mode. The following settings were used for acquisition: The sample nebulizer set to 45 psig with sheath gas flow of 12 L/min at 400°C. Drying gas was kept at 325°C at 8 L/min. Fragmentor was set to 125 V, with the skimmer set to 50 V and Octopole Vpp at 400 V. Samples were acquired in centroid mode for 1.5 spectra/s for m/z’s from 50–1500.

Collected data from the above methods was analyzed by XCMS and X13CMS48,49. Metabolites were identified from (m/z, rt) pairs by both retention time comparison with authentic standards and expected isotopomer distributions. When indicated, cells were treated with D-[U-13C6]-Glucose, D-[U-13C6]-Fructose, L-[U-13C5]-Glutamine, or L-[U-13C3]-Lactate in place of the unlabeled nutrient (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Tewksbury, MA). Labeling proceeded for 8 hours.

The various fatty acids are represented by “Cx:y” where x denotes the number of carbons and y the number of double bonds. For example, the symbol for palmitic acid is C16:0 and palmitoleic acid is C16:1.

RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from frozen cell pellets using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, cells were lysed using Buffer RLT supplemented with 1% (v/v) beta-mercaptoethanol and QIAshredder columns (Qiagen) were subsequently used to homogenize the cell lysates. To remove contaminating genomic DNA, on-column digestion with DNase I was performed using the RNase-free DNase Set (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s instructions.

KHK amplicon generation

Targeted isoform sequencing is a highly specific, amplification-based method used to characterize the diversity of expressed isoforms at a particular gene locus. Long-read sequencing of full-length KHK isoforms was performed on RNA extracted from 6 cell lines. Briefly, 100 ng of high-quality, DNase-treated total RNA was primed with an oligodT primer and reverse-transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using the SuperScript IV First-Strand Synthesis System (ThermoFisher Scientific). The RT reaction was treated with Ribonuclease H (RNaseH) to remove any remaining RNA templates. The single-stranded cDNA was then supplied at 5% of the total PCR reaction volume of targeted amplification using KHK-specific primers and TaKaRa LA Taq Polymerase with GC Buffer I (Clontech). Three separate PCR reactions were performed per sample using three unique reverse primers designed at alternate 3’ exons based on NCBI reference annotations of KHK. The resulting full-length cDNA amplicons were then purified of excess nucleotides, adapter dimers and buffers using 1X AMPure PB beads (Pacific Biosciences).

KHK primer sequences [primer name (primer sequence 5’ --> 3’)]: hKHK_F_cds (ATGGAAGAGAAGCAGATCCTGTG), hKHK_R_cds (TCACACGATGCCATCAAAG), hKHK_R_altCDS (TCACCCTAGCAGCCCCC), hKHK_R_altCDS_ex5 (CCTCATTCTGCAGAGGAAAA)

PacBio library preparation and sequencing

The purified, full-length cDNA amplicons were then prepped for PacBio single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing using the Express Template Preparation Kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences) and following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 100 ng of cDNA from each sample was treated with a DNA Damage Repair enzyme mix to repair nicked DNA, followed by an End Repair and A-tailing reaction to repair blunt ends and polyadenylate each template. Next, barcoded overhang SMRTbell adapters were ligated onto each template and purified using 1X AMPure PB beads to remove small fragments and excess reagents (Pacific Biosciences). The completed SMRTbell libraries were further treated with the SMRTbell Enzyme Clean Up Kit to remove unligated templates and then were equimolar pooled. The final pooled library was then annealed to sequencing primer v4 and bound to sequencing polymerase 3.0 before being sequenced on one SMRTcell 1M on the Sequel I system with a 20-hour movie.

Targeted IsoSeq analysis

After data collection, the raw sequencing subreads were imported into the SMRTLink 9.0 bioinformatics tool suite (Pacific Biosciences) for processing. Intramolecular error correcting was performed using the circular consensus sequencing (CCS) algorithm to produce highly accurate (>Q20) CCS reads, each requiring a minimum of 3 polymerase passes. The CCS reads were then passed to the lima tool to remove barcode sequences and orient the isoforms into the correct sense or antisense direction. The refine tool was then used to remove concatemers from the full-length reads, resulting in final consensus isoforms ready for downstream analysis. The full-length, non-chimeric (FLNC) reads were subsequently aligned to the GRCh38 reference genome using GMAP (version 2020-09-12), a splice-aware aligner specifically designed to handle long-read cDNA sequences. Redundant transcripts were then collapsed down to representative isoforms by passing the uniquely mapped isoforms through the TAMA Collapse algorithm with default parameters. The representative isoforms were further processed using the SQANTI3 (version 1.6) tool suite, which identifies and removes RT-switching and intra-priming artifacts. The filtered isoforms were then annotated using SQANTI3 by comparing each isoform to the NCBI RefSeq gene annotation database and categorized as either a known or novel transcript of KHK. Novel isoforms were defined as having at least one novel splice junction not previously annotated by NCBI. Isoforms with more than one FLNC supporting read from each sample were then merged together using the TAMA Merge algorithm to form one final isoform set representing all isoforms expressed across all samples.

Recombinant pyruvate kinase production

Human PKM1, PKM2 and its mutants were cloned into a pET28a vector (Novagen, Darmstadt, Germany) at NdeI and BamHI sites and expressed as an N-terminal His6 tag fusion protein. The protein was expressed and purified by standard protocol. Briefly, pET28a-PKM2 was transformed into BL21(DE3)pLysS cells and grown to an absorbance of 0.8 at 600 nm, then induced with 0.5 mM IPTG for 7 h at room temperature. Cells were lysed by lysozyme in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM NaCl, 100 mM KCl, 20% glycerol, 10 mM imidazole, 1 mM PMSF) and cell lysate was cleared by centrifugation. Enzyme was purified by batch binding to Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The resin was then washed with lysis buffer containing 30 mM imidazole for 200 column volumes, and His6-tag-PKM2 was eluted with 250 mM imidazole. The protein was dialyzed overnight at 4 °C to remove the imidazole. Human PKL was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, Cat. #8569-PK).

Density gradient ultracentrifugation, cross linking, size-exclusion

Sucrose gradients were formed and analyzed as described in detail elsewhere50. Briefly, 10mL 10–40% sucrose gradients were created using a Gradient Master (BioComp Instruments, Fredericton, NB) with the indicated metabolites evenly distributed throughout the gradient at a concentration of 1mM. Subsequently, 400ug of recombinant protein was incubated with the indicated metabolites at 1mM for 30 mins at 25C, then gently layered atop the gradients. The gradients were then centrifuged for 16 hours at 4C and 237,000g in an SW 55 Ti rotor and Beckman L-80 ultracentrifuge (Brea, CA). A piston gradient fractionator (BioComp instruments) was then used to fractionate the separated protein complexes which were then analyzed by western blot.

For cross linking, purified recombinant enzyme at a concentration of 10ug/mL in 1x pyruvate kinase dilution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2) was incubated with the indicated metabolites for 30 minutes at 37C. Then, Di(N-succinimidyl) glutarate (Millipore Sigma) was added to a final concentration of 1mM and incubated for 10 minutes at 25C. The reaction was quenched with 1M Tris-HCl to a final concentration of 50mM and samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting as previously described.

For size exclusion chromatography, recombinant PKM2 was incubated alone or with FBP (100 μM) or F1P (500 μ M) for one hour in PK dilution buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM KCl, and 5 mM MgCl2) on ice. Protein was then run on a Superdex 200 Increase 10/300 column (GE Life Sciences) equilibrated with the same buffer and metabolite. 0.5 mL fractions were collected and subjected to SDS Page and Coomassie blue staining.

Pyruvate kinase docking simulations

The crystal structure of PKM2 from Christofk et al. 200821 was used to perform docking simulations for F1P using the Maestro software package (Release 2019-2, Schrödinger, LLC).

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical analyses were conducted using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad, v9.1). Data represent mean ± S.E.M. unless stated otherwise. Exact P-values are provided with source data. Experiments were repeated independently, with similar results obtained. Animal cohort sizes for TEPP-46 and GEMM villus studies were informed by a priori power calculations using the variation from initial villus investigations with the aid of G*Power software (G*Power, v3.1). Investigators were blinded during image analysis of villus length and tumor burden. Investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments.

Extended Data

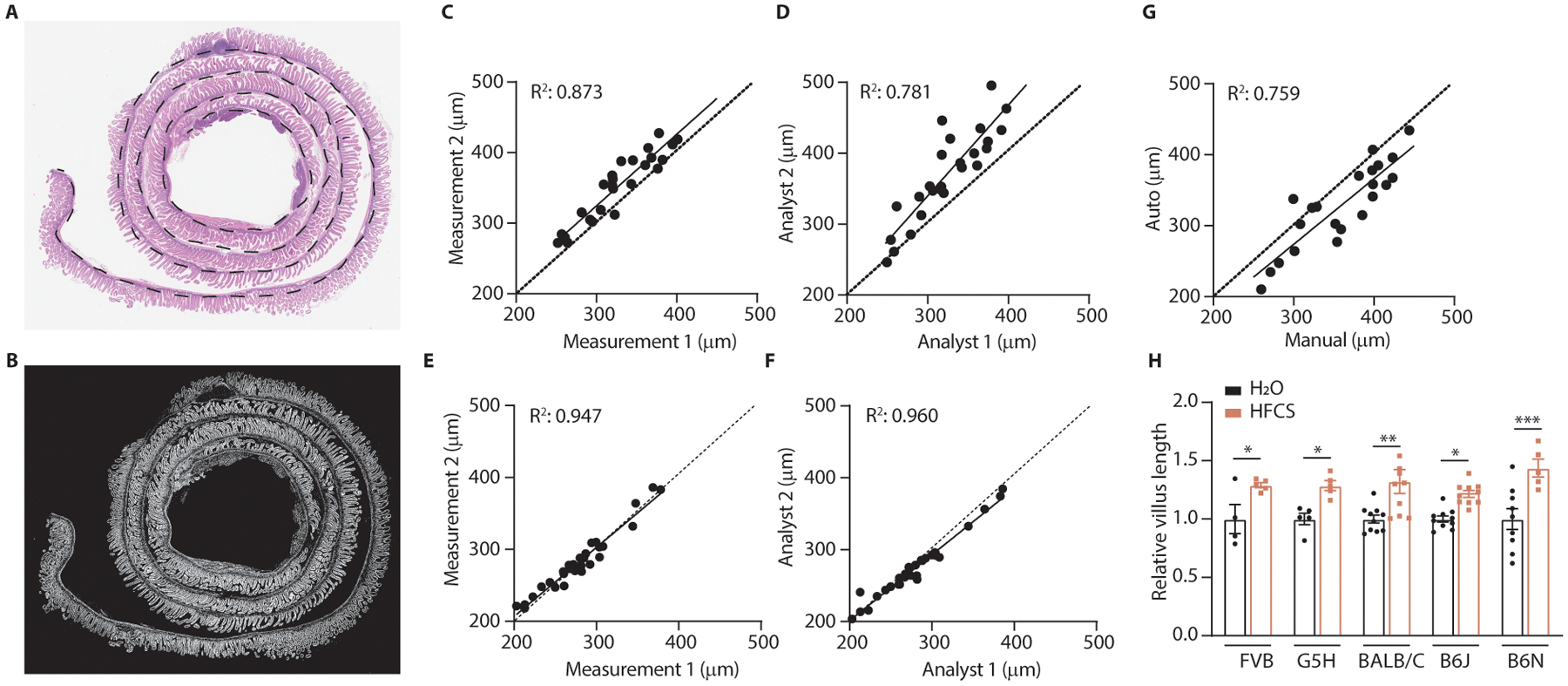

Extended Data Fig. 1. Image segmentation avoids pitfalls of manual villi measurement.

(A) Stain-normalized H&E images of swiss-rolled intestines were loaded into image-analysis software, which was used to manually measure the length of the gut section (dotted black line). (B) Image-segmentation isolates villi (white) while excluding other tissues such as lymph nodes, pancreas, and intestinal crypts. (C) Intraoperator variation is a source of measurement error in manual villi measurements. X and Y axes represent measurements taken by the same analyst at different times. (D) Interoperator variation is another source of measurement error in manual villi measurements. X and Y axes represent measurements taken by different analysts. (E, F) Intraoperator and interoperator variation are minimized when using the semi-automated protocol. (E, F) are the same comparisons as (C, D), however the only manual measurement in the semi-automated method is the measurement of the whole gut section length. (G) Automated and manual measurements correlate. X and Y axes represent measurements obtained from the manual and semi-automated protocols respectively. (H) Mice from various genetic backgrounds were fed HFCS and the mean villus length in the duodenal intestinal epithelium was measured using a custom analysis algorithm (mice per group, left to right (H2O|HFCS): 4|5 5|5 10|10 10|10 9|5). C-G: Each point represents a distinct image; dotted line: unity; R2 is displayed for the linear regression fit of the data. H: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, error bars represent ± S.E.M. See source data for exact p-values for all figures.

Extended Data Fig. 2. Dietary fructose promotes weight gain and adiposity independent from caloric intake.

(A) Mice fed normal chow with or without 25% HFCS ad libitum were weighed weekly for 6 weeks. (B-D) Total body lean and fat mass was measured before and 5 weeks after mice were placed on diets. (E-G) Total consumption of chow and fluid was measured weekly to calculate caloric consumption (n = 5 serial measurements per group). (H, I) Tissues from mice on the indicated diets were harvested and weighed and the liver was assayed for triglyceride content. WAT = white adipose tissue from the left or right gonadal fat depot. (J) After 5 weeks, mice were fasted and blood glucose was measured by glucometer (A-J: 5 mice per group). (K) A lipid tolerance test was performed on wild-type (WT) female mice fed HFCS (n = 3 mice per group). (L) Mice treated with water or HFCS were fasted and then given an I.P. injection of poloxamer 407. 1 hour later TG was measured from serum and the mice were given an oral olive oil bolus. 2 hours later, serum triglyceride levels were measured again (n = 7 (H2O) and 5 (HFCS) mice per group). (M) Mice fed fructose-free control diets (control) high-fat diets consisting of 45% kcal from fat (HF) and high fat diets with sucrose in place of glucose as the main sugar (HFHS) were monitored weekly for chow consumption by cage (n = 3 repeated measurements per group). (N) Total fat and lean body mass were measured after 5 weeks on diet. Statistical comparisons are made against control fat mass (n = 5 mice per group). (O) After 4 weeks on diet, mice were fasted and blood glucose was measured via glucometer (n = 3 mice per group). (P-R) Upon sacrifice, tissues were harvested and weighed, liver tissue was homogenized and assayed for triglyceride content, and mouse intestines were excised en bloc and intestinal length was measured using ImageJ software (n = 5 (P, R) and 4 (Q) mice per group). (S) Mice treated with high-fat or high-fat high-sucrose diets for 2 weeks were housed in metabolic cages and food intake over 24 hours was measured. O2 consumption and CO2 production were measured to calculate the respiratory exchange ratio (T). Total distance traveled was also measured (U), as was hourly energy expenditure (V), which was calculated using the Weir equation8. (W-Z) Mice were individually housed and fecal matter was collected over a 24 hour period (W), dried (X), then analyzed via bomb calorimetry to measure energy content and energy loss over the collection period (Y, Z) (S-Z: 4 mice per group). B, C, H, N: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; D-G, I, J, L, S-U, W-Z: Student’s two-sided t-test; K, M, O, Q: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; ns: not significant; *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001; all data represent means ± S.E.M.

Extended Data Fig. 3. HFCS increases villus survival, GLUT5, and HIF target protein expression.

(A) A model depicting the strategy of the bromo-deoxyuridine (BrdU) tracing experiment. BrdU labels cells synthesizing DNA (brown). These cells transit up the length of the villus and away from richly oxygenated blood in 3–4 days. Unlabeled cells beyond the BrdU front at the time of animal sacrifice were thus generated prior to BrdU injection. (B) Duodenal villus length was measured from H&E images from H2O and HFCS-treated mouse intestine (n = 3 mice per group, 40 villi per mouse). (C) Mice were administered BrdU 72Hrs prior to sacrifice, then intestines were examined by IHC. The length of BrdU-labeled regions of the villus were measured in both treatment groups and this length was divided by the interval between injection and sacrifice to yield migration rate (n = 3 mice per group, 15–20 duodenal villi per mouse). (D-E) In a separate experiment, mice were treated with H2O or HFCS and given BrdU (green) 48 hours prior and EdU (red) 24 hours prior to sacrifice. Duodenal villi were then stained and imaged via IF and analyzed as in (C). The difference between the BrdU and EdU lengths was divided by the interval between injections to yield the migration rate (n = 3 (H2O) and 4 (HFCS) mice per group, 15–20 duodenal villi per mouse, scale bar: 100μm). (F) Mice treated with H2O or 25% HFCS were euthanized and the intestines were examined by IHC against ki67, cleaved-caspase 3, and Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL); scale bar: 200μm. (G) Prior to sacrifice, mice treated as in (F) were injected with pimonidazole to label tissue hypoxia. Intestines were then fixed and examined for pimonidazole intensity by IHC. Representative images shown; scale bar: 500μm. (H) Pimonidazole positive area was quantified and normalized to total small intestine (SI) area (n = 5 mice per group). (I) WT mice treated with H2O or HFCS and total-body, constitutive GLUT5 KO mice treated with HFCS were sacrificed and intestines were fixed and examined by IHC. Representative images shown; upper scale bar: 200μm, lower scale bar: 50μm. (J) WT mice treated with H2O or 25% HFCS ad libitum for 4 weeks were sacrificed and intestinal epithelium was harvested for western blot for indicators of cell health including markers of energy homeostasis (pACC, pAMPK) and anti-apoptotic proteins (BCL2, BCL-XL, MCL-1). (K) Animals treated as in (J) were also sacrificed and the intestinal epithelium was examined by western blot for hypoxia response proteins (ENO1, LDHa) and KHK. B, C, E, H: two-sided student’s T-test; ns: not significant; ***P<0.001; all data represent means ± S.E.M. For gel source data, see Fig. S1 in the supplement.

Extended Data Fig. 4. Fructose enhances hypoxic cell survival.

(A) At the conclusion of the experiment depicted in Fig. 2A, HCT116 cells were harvested and analyzed by trypan blue exclusion assay. Total live cells per group were counted and normalized to the fructose-free group. (n = 3 biological replicates per group) (B, C) HCT116 cells were plated near confluence and cultured in hypoxia with or without 10mM fructose in the media. Every 48 hours, as indicated, the media was exchanged with fresh oxygen-equilibrated media. Confluence was monitored and at the conclusion of the experiment cells were analyzed by trypan blue exclusion assay as in (A) (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (D) HCT116 or (E, F) DLD1 cells were cultured with glucose and either stausporin (“Stau”, 100nM, apoptotic control) or fructose, in media which also contained an AnnexinV dye (D, E) and a nucleic acid binding cell death dye (F, “CytoTox”). Cells were incubated in normoxia (“N”) or hypoxia (“H”) and imaged daily via live cell imaging. Stain intensity is reported as positive cell area per well normalized to the initial normoxic glucose control (n = 3 biological replicates per data point). (G) Intestinal organoids were generated from adult B6J mice and cultured in hypoxia with or without fructose for 72 hours. At experiment termination, organoids were pulsed with EdU, fixed in situ, stained for the indicated targets, and examined via confocal microscopy. Representative images are shown. Scale bar: 50μm; white arrows indicate regions with intra-organoid CC3 puncti. (H, I) organoids treated as in (G) were rapidly dissociated and stained for viability (via a membrane impermeable dye) and EdU. The resulting cell suspensions were analyzed by flow cytometry. Viability is expressed as viable cells recovered per culture well, normalized to the average of the normoxic glucose controls (n = 3 progenitor mice; each pair of points represents a different mouse progenitor). In these and future in-vitro assays, unless otherwise noted, glucose was replenished daily as described in methods. A, D, H: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; B, C: two-sided student’s T-test; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ****p<0.0001; all data represent means ± S.E.M.

Extended Data Fig. 5. Hypoxia increases GLUT5 expression, KHKA transcription.

(A) HCT116 and DLD1 cells cultured at the indicated O2 concentrations with or without 10mM fructose were lysed at 36 hours and western blotted for the indicated targets. “+” in the “%O2” row indicates that 100μM cobalt chloride was added to the media at time 0. (B) RNA was extracted from HCT116 cells treated in normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours and analyzed by IsoSeq. The relative proportion of the A and C isoforms of KHK are shown (n = 1 biological replicate per O2 condition). (C) HCT116 cells cultured in normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours were lysed and tested for KHK activity via enzymatic assay (n = 3 biological replicates). C: two-sided student’s T-test; ** p<0.01; all data except B represent means ± S.E.M. For gel source data, see Fig. S1 in the supplement.

Extended Data Fig. 6. F1P accumulates in cells and correlates with marked metabolic changes in hypoxia.

(A) HCT116 cells cultured in hypoxia with fructose were labeled with various U-13C metabolites and intracellular metabolites were detected via LC-MS. The Y-axis reflects the fraction of the detected metabolite labeled with 13C on the number of carbons denoted by the colors to the right of each graph. The X-axis denotes the labeled feed-metabolite for that particular group. The graph for fructose, for example, indicates that all detected fructose ions were labeled at all 6 carbons with 13C when U-13C6 fructose was provided in the media (n = 3 biological replicates per unique label). (B) HCT116 and DLD1 cells were cultured in hypoxia with 25mM glucose with or without 10mM fructose. At 48 hours the growth media was assayed for glucose and fructose content. Colors indicate the initial media formulation for each group. The X-axis denotes which sugar is being measured (n = 3 (Glc) and 2 (Glc + Fru) biological replicates per group). (C) Mouse intestinal organoids were cultured in hypoxia with 10mM glucose with or without 10mM fructose for 72 hours. Glucose in the 3mL culture volume was increased by 5mM daily to account for glucose depletion. After 72 hours the growth media was assayed for sugar content (n = 3 biological replicates per group, 1 from each progenitor mouse). (D) HCT116 cells were treated with uniformly labeled 13C fructose or glucose and isotopologues for intracellular fructose were generated. Unless otherwise noted, each column represents an experimental group which received some form of glucose and fructose (n = 3 biological replicates per x-axis label; N: normoxia, H: hypoxia). (E) Principal component analysis and (F) targeted heatmap of metabolomics data from HCT116 cells cultured at confluence in hypoxia for 36 hours then harvested for LC-MS. PCA data are centered and unit-variance scaled, heatmap data are row-normalized ion abundances (n = 3 biological replicates per group, loading plots available in supplement). (G) PK activity was measured via enzymatic assay in lysates from HCT116 cells cultured in normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours with or without fructose. Assay wells were loaded with equal amounts of total protein for each group (n = 3 biological replicates per group). F1P: fructose 1-phosphate; FBP: fructose 1, 6-bisphosphate; G6P: glucose 6-phosphate; G3P: glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 2PG: 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; TCA: tri-carboxylic acid cycle; aKG: alpha-ketoglutarate; PA: phosphatidic acid; MG: monoacylglycerol; DG: diacylglycerol; G: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; *P<0.05; all error bars represent means ± S.E.M.

Extended Data Fig. 7. The FBP-binding pocket of PKM2 is important for F1P inhibition.

(A) Simulated binding positions and residue interactions for FBP (left) and F1P (right) in the allosteric binding pocket of PKM2. Residues 482 and 489 are components of the FBP-activation loop which are predicted to interact with FBP but not F1P 25. (B) Purified recombinant PKM2 (rPKM2) was incubated with the indicated metabolites and separated through a sucrose gradient (also containing the indicated metabolites). Fractions were removed from the gradients and analyzed via SDS-PAGE and western blot for PKM2. FBP concentration was 100uM; F1P concentration was 500uM. (C) Recombinant PKM2 incubated with the indicated metabolites was run on a gel filtration column and subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie blue staining. FBP concentration during incubation and in the column was 100uM; F1P concentration was 500uM. (D, E) The activity of recombinant PKL and the PKM2 R489L mutant pre-incubated with the indicated metabolites was measured via enzymatic assay (n = 3 independent reaction wells per group). The residues responsible for PKM2 binding FBP are altered in these isoforms. (F-H) Recombinant PKM2 mutants with alterations to the FBP-binding pocket were generated and assayed for PK activity with the indicated metabolites added at the incubation step. FBP was used at 100μM and F1P was used at 1mM (n = 2 wells per data point). (I) The activity of recombinant PK pre-incubated concurrently with the indicated metabolites or compounds was measured via enzymatic assay (n = 3 wells per group). D, E: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons. *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001; error bars represent means ± S.E.M. For gel source data, see Fig. S1 in the supplement.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Fructose and PK activation modulate cell survival in hypoxia.

(A) HCT116 cells were transduced with short-hairpin RNA targeting a scrambled sequence (shScr) or PKM2 (shPKM2). 2 weeks after transduction, parental cells as well as these modified lines were western blotted for the protein targets indicated on the left. 3 separate shScr and shPKM2 subclones were analyzed. Mouse gastrocnemius (Gastroc.) muscle and liver tissue were used as PKM1 and PKLR controls respectively. B-actin was used as a loading control. (B) HCT116 cells expressing the indicated hairpins were cultured in normoxia or hypoxia with or without fructose and TEPP-46 (50μM) in the media. Glucose was replenished daily, and confluence was monitored by live cell imaging (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (C) shScr or shPKM2-transduced HCT116 cells were cultured in hypoxia for 24 hours with or without fructose or fructose and TEPP-46 (50μM). Total cell H2O2 was then measured using a luciferase-based assay (n = 4 biological replicates per group). (D) Parental HCT116 cells were subjected to the same treatment as in (C) but were cultured for 72 hours in normoxia or hypoxia with daily glucose replenishmen (n = 4 biological replicates per group). (E) HCT116 cells cultured in hypoxia for 24 hours were assayed for reduced thiols (n = 5 biological replicates per group). (F) HCT116 cells cultured in hypoxia were provided with 10mM glucose, 10mM glucose with N-acetylcysteine (NAC) or 5mM glucose and 5mM fructose in media. After 144 hours the viability of the adherent cells was measured (n = 4 biological replicates per group). (G) HCT116 and DLD1 cells were subjected to varying levels of hypoxia for 24 hours with fructose introduced in the media either at the time the cells were placed in hypoxia (“+”) or as pre-treatment (“PT+”), starting in the previous cell passage prior to plating the experiment and continuing through the hypoxic period (4 days total fructose exposure with the final 24 hours in hypoxia). Cells were rapidly lysed at the conclusion of the experiment and analyzed by western blot. (H) HCT116 cells were exposed to hypoxia with or without fructose in the media and LC-MS analysis was performed on the resulting polar extracts (n = 3 biological replicates per group). (I) HCT116 cells were cultured in normoxia or hypoxia for 24 hours with or without fructose. At the end of the experiment, media samples were taken from each well and analyzed via enzymatic assay for lactate content (n = 3 biological replicates per group). C, D, I: Two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; E: Student’s two-sided t-test; F: One-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; ns: not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001; all data represent means ± S.E.M where possible. For gel source data, see Fig. S2 in the supplement.

Extended Data Fig. 9. PKM2 ablation in villi results in PKM1 upregulation.

(A) Representative intestines from 12-week-old mice examined by IHC for the indicated targets (scale bar = 200μm). (B) Mouse intestinal epithelial cell lysates from wild-type mice (WT), VillinCre;PKM2fl/fl mice, and WT mice treated with TEPP-46 were analyzed via enzymatic assay for pyruvate kinase activity (mice per group, left to right: 5|10|5; same final protein concentration in each reaction well). (C) WT and VillinCre;PKM2fl/fl mice were sacrificed and intestines were fixed and examined by IHC against PKM2 or PKM1, respectively. The left column shows proximal jejunum villi in each animal while the next two columns are high magnification of the distal and proximal villus in each animal. The last column is colon epithelium. Blue arrows indicate nuclei with intense staining. Scales for each row are as indicated. (D) WT, KHK KO, and intestinal PKM2 KO mice were treated with H2O or HFCS and the intestinal epithelium was examined by western blot. (E, F) LDHa and ENO1 intensity were quantified relative to the b-Actin loading control (mice per group, left to right: 3|3|3|3|2|5). (G) Serum triglyceride (T.G.) following a lipid challenge was measured in mice fed water (H2O) or 25% HFCS via daily oral gavage for 2 weeks. Units are normalized to the initial timepoint to highlight changes in blood T.G. after the bolus (mice per group, top to bottom: 7|6|5|5). (H) After 2 weeks on diet mice were euthanized, and the gonadal fat deposits were weighed. Units represent total gonadal depot fat mass as a percentage of total body mass, normalized to H2O animals (mice per group, left to right: 14|14|10|5|4|5|5). (I) Liver was also harvested and analyzed for T.G. content per gram tissue (mice per group, left to right: 4|4|4|5|4|5|4). B, H: one-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; E, F: two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak post-test for multiple comparisons; ns: not significant, *P<0.05, **P<0.01; all data represent means ± S.E.M. For gel source data, see Fig. S2 in the supplement.

Extended Data Fig. 10. TEPP-46 ablates HFCS-induced villus elongation, tumor growth.