Abstract

Introduction

Second primary tumors (SPTs) in head and neck cancer are thought to occur from premalignant lesions that are present at the time of the primary tumor diagnosis. The association of the modality used to treat the primary lesion with SPT occurrence is not clear.

Objective

The aim of the study was to assess the incidence of SPTs in patients with head and neck malignancies, according to treatment modality.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective cohort study. All patients who were treated at Soroka Medical Center between 2000 and 2013 for a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma were assessed. Data analysis included tumor site of the primary and second primary and treatment modality of the primary tumor. In addition, demographics as well as habits were recorded as well.

Results

Of the 184 patients included in the cohort, SPT developed in 31 patients (17%) with a median time to diagnosis of 4.3 years. Smoking was reported in 74% of those with SPT and 78% of those without. The most common site for SPT was the lungs, with 13 cases, 42% of the total SPTs. Among patients who developed an SPT, for 12 of those with an index tumor in the oral cavity or oro-hypopharynx, 8 (67%) developed an SPT in the same location; for 18 of those with an index tumor in the larynx, 11 (61%) developed a SPT in the lungs and bronchi (p = 0.001). On multivariate analysis, the treatment modality used was not found to be associated with the occurrence of SPTs and the radiotherapy showed no protective or harmful effect (HR 0.64 p = 0.24).

Conclusion

Treatment modality used for head and neck cancer does not seem to be associated with the occurrence of SPTs.

Keywords: Chemotherapy, Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, Radiation, Second primary tumor, Surgical oncology

Introduction

Head and neck cancer accounts for about 3% of all cancers in the USA [1]. To improve patient outcomes and minimize iatrogenic damage, various treatment protocols have been developed. These include better surgical techniques, improved radiotherapy protocols, and new chemotherapy and immunotherapy drugs. Improvements have been observed in the locoregional control of oral cavity and oropharyngeal tumors, yet only minimal advancement has been noted in the long-term survival of patients [2, 3]. The development of a second primary tumor (SPT) is a major contributor to mortality in this population [2, 3, 4, 5].

Rates of SPT in head and neck cancer have been reported as 10–35% [6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11]. The wide range may be due to differences in time of analysis, the sites investigated and population characteristics. Despite better understanding of the mechanisms by which SPTs develop, and the implementation of new imaging techniques during follow-up, SPTs are often diagnosed during the disease course [11]. Most SPTs are discovered at least 6 months after the index tumor and are thus termed metachronous tumors.

Only a few studies have examined the relationship between treatment modality and SPT incidence, and the results are equivocal. Some studies found that patients treated with irradiation experienced reduced incidence of SPTs [12, 13], while others suggested that the use of radiotherapy acts as a potential source of field cancerization [14]. The objective of this study was to examine an association of the occurrence of a metachronous SPT with the modality used to treat a primary head and neck cancer, and with smoking and alcohol, which are known risk factors for head and neck cancer.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of the Cohort

In this retrospective cohort study, medical records were used to identify all patients treated for a head or neck squamous cell carcinoma as index tumor at the Soroka University Medical Center, Beer-Sheva, Israel, between January 2000 and December 2013. Soroka University Medical Center is a 1,000 bed tertiary care hospital. We excluded from the analysis patients who were under age 18 years, without available data until death or to the end of the study period, treated for previous cancer, with metastases or synchronous SPT at the time of diagnosis, developed skin cancer as the SPT at a distant site from the primary tumor. To minimize the likelihoods that a distant metastasis will count as an SPT, we applied the following rule: solitary malignant pulmonary nodules confirmed to be malignant were considered an SPT and not a metastasis. Cases in which several additional pulmonary nodules appeared during the follow-up imaging were excluded due to the high likelihood that those are metastases. We also excluded any case in which the SPT did not undergo a biopsy and patients who died during the first 6 months after treatment. The electronic and manual medical records of the patients were assessed for background diseases, smoking, and alcohol use (past or current vs. never), diagnosis and treatment of index tumors, diagnosis and treatment of SPTs, and mortality.

Definitions

The primary outcome was defined as the development of an SPT, using Warren and Gates' criteria [15], according to which [1] both tumors are diagnosed histologically as malignant [2], either a normally appearing mucosa or a minimal time period of 5 years separates the tumors, and [3] the SPT is not a metastasis of the primary tumor.

Statistical Analysis

We compared characteristics of patients who did and did not have a SPT during the follow-up period. We also analyzed the data according to 3 categories of tumor location [1]: nasopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses [2], oral cavity and oro-hypopharynx, and [3] larynx. The results are presented as the mean ± SD for continuous variables, as total patients (or percentage of total patients) for categorical data, and median and interquartile range for variables with non-normal distribution. The t-test was used for comparison of continuous variables, and χ2 or Fisher's exact tests were used for categorical data. We utilized the Mann-Whitney test for the comparison of variables with non-normal distribution.

Traditional survival analysis methods rely on comparing time-to-event (development of SPT in our study), and patients who did not experience the event are censored at the end of the follow-up period. Death due to causes other than SPT in patients with an elevated risk of SPT might bias the estimated SPT development risk, that is, such cause acts as a competing risk. To adjust for this bias, we used Fine and Gray analysis [16], adjusting the survival model for the calculated risk of SPT development in patients who died before the end of the follow-up. The association between baseline characteristics and outcome was assessed by Cox proportional hazards regression analysis and described as hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. Variables found to be associated with the outcome in the univariate analysis, with a p value <0.1, and clinically significant factors were included in the models after verifying the proportionality of the hazards. A two-tailed p value of ≤0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analysis was done using SPSS version 21.

Results

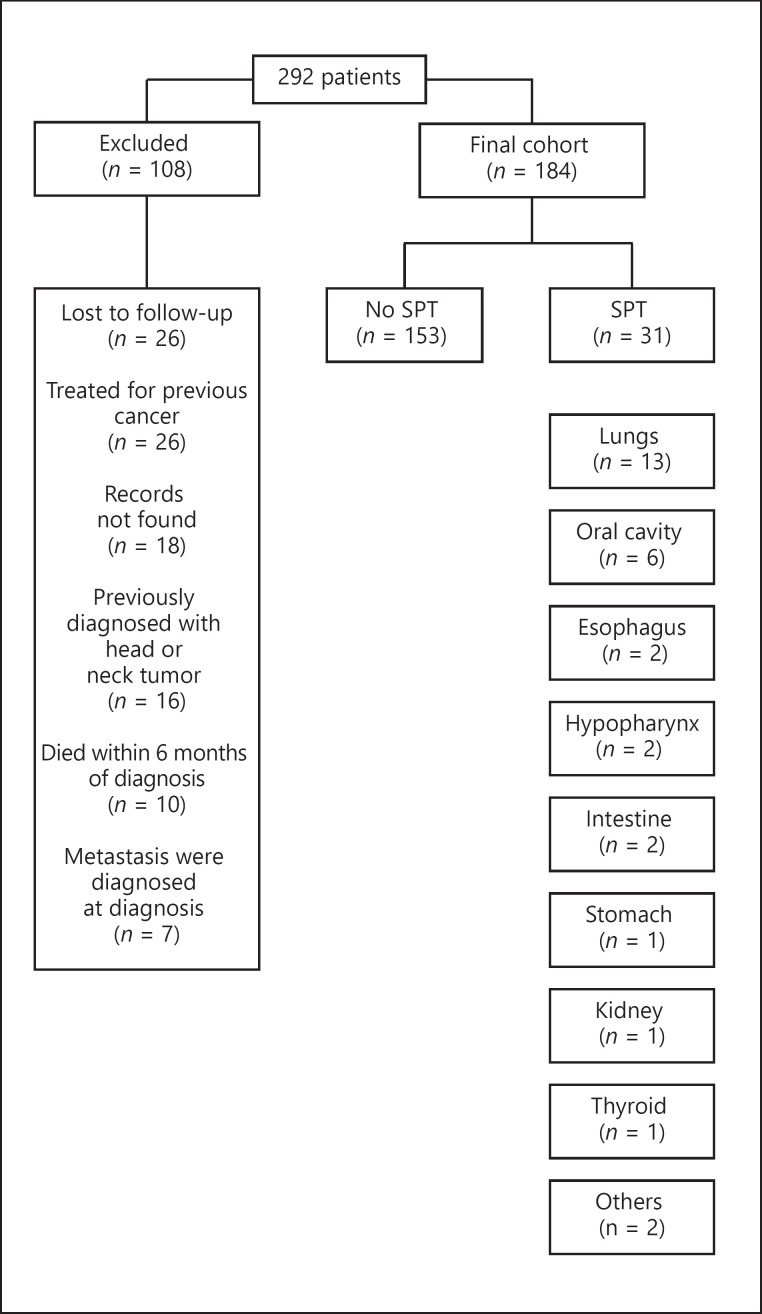

Of the 292 patients treated for head or neck squamous cell carcinoma at Soroka University Medical Center during the study period, 108 did not meet the study eligibility criteria and were excluded from the analysis (Fig. 1). Of the remaining 184 patients, SPT developed in 31 (17%) (Fig. 1) during a median follow-up period of 3.2 years (interquartile range 1.6–6.7); the mean time until diagnosis of a metachronous SPT was 4.3 ± 3 years; and median time 4.3 years (interquartile range 2–6). The most common site for SPT was the lungs, with 13 cases, 42% of the total SPTs.

Fig. 1.

Study cohort structure, including the various locations of SPTs. SPTs, second primary tumors.

Tables 1 and 2 present the baseline characteristics, tumor location, staging, and treatment modalities of the cohort, according to the detection of a SPT. No statistically significant differences were found between those who did and did not develop SPT, with respect to the mean age at diagnosis of the first primary tumor, gender or ethnicity distribution, and the past or current usage of alcohol and smoking. No association was found between the usage of alcohol and smoking (current or past vs. never) and the development of SPT. Yet, most of the patients in both groups smoked (74 and 78.5%).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population (n = 184)

| Variables | Second primary tumor (n = 31) | No second primary tumor (n = 153) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis of the first primary tumor, years (mean ± SD) | 63±12.5 | 61.5±11 | 0.5 |

| Gender, N (%) | |||

| Male | 22 (71.0) | 119 (77.8) | 0.4 |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | |||

| Jewish | 27 (87.1) | 136 (88.9) | 0.7 |

| Bedouin | 4 (12.9) | 17 (11.1) | |

| Alcohol usage (past + current), N (%) | 7 (22.6) | 36 (23.5) | 0.9 |

| Smoking (past + current), N (%) | 23 (74) | 120 (78.5) | 0.6 |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the study population (n = 184)

| Variables | Second primary tumor (n = 31) | No second primary tumor (n = 153) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index tumor locations | |||

| Nasopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses, N (%) | 1 (3.2) | 13 (8.5) | |

| Oral cavity, oro-hypopharynx, N (%) | 12 (38.7) | 47 (30.7) | 0.47 |

| Larynx, N (%) | 18 (58.1) | 93 (60.8) | |

| Treatment modality | |||

| Chemotherapy alone, N (%) | O (O) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Radiotherapy alone, N (%) | 4 (12.9) | 30 (19.6) | |

| Surgery alone, N (%) | 11 (35.5) | 32 (20.9) | |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy, N (%) | 8 (25.8) | 39 (25.5) | 0.59 |

| Radiotherapy + surgery, N (%) | 7 (22.6) | 35 (22.9) | |

| Chemotherapy + surgery, N (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy + surgery, N (%) | 1 (3.2) | 15 (9.8) | |

| Any radiotherapy, N (%) | 20 (64.5) | 119 (77.8) | 0.12 |

| Any chemotherapy, N (%) | 9 (29.0) | 56 (36.6) | 0.42 |

| Surgery alone, N (%) | 11 (35.5) | 32 (20.9) | 0.08 |

| Index tumor stage at diagnosis, comparing stage 1–3 versus stage 4, N (%) | |||

| 1–3 | 26 (83.9) | 99 (64.7) | 0.04 |

| 4 | 5 (16.1) | 54 (35.3) | |

| Index tumor T class at diagnosis, N (%) | |||

| T1 | 7 (22.6) | 49 (32.0) | |

| T2 | 15 (48.4) | 39 (25.5) | |

| T3 | 4 (12.9) | 30 (19.6) | 0.16 |

| T4 | 5 (16.1) | 34 (22.2) | |

| Tx | 0 (0) | 1 (0.7) | |

| Index tumor N class at diagnosis, N (%) | |||

| N0 | 23 (74.2) | 101 (66.0) | |

| N1 | 6 (19.4) | 17 (11.1) | |

| N2 | 0 (0) | 24 (15.7) | 0.19 |

| N3 | 1 (3.2) | 8 (5.2) | |

| Nx | 1 (3.2) | 2 (1.3) | |

| Follow-up time, years (until second primary/death/end FU) | |||

| (median, interquartile range) | 4.3, 1.9–5.9 | 3.2, 1.6–6.8 | 0.48 |

| Follow-up time, years (until death/end FU) | |||

| (median, interquartile range) | 4.6, 2.0–7.2 | 3.2, 1.6–6.8 | 0.09 |

The incidence of SPT differed with regard to the location of the primary tumors; the highest incidence of developing SPT was for primary tumors located in the oral cavity and oro-hypopharynx (20%) and the lowest incidence was for primaries in the nasopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses (7%). Primary laryngeal tumors had a 16% incidence of SPT development. The rate of SPTs was higher for T2 tumors than for tumors of other T staging (Table 2); however, this finding was not statistically significant (p = 0.15).

Among patients who developed a SPT: for 12 of those with an index tumor in the oral cavity or oro-hypopharynx, 8 (67%) developed an SPT in the same location; for 18 of those with an index tumor in the larynx, and 11 (61%) developed a SPT in the lungs and bronchi (p = 0.001) (Table 3). Parameters associated with SPTs, according to univariate analysis, are shown in Table 3. To avoid bias while using the regular time-to-event analyses, we used all-cause mortality as a competing risk event. A trend is demonstrated toward a reduced risk of developing SPT, when all treatment modalities are considered (HR 0.18, CI 0.02–1.46). A similar trend was demonstrated when radiotherapy was considered (either alone or combined with other modalities), HR of 0.54 (CI 0.26–1.11). On the other hand, a trend was demonstrated toward twice the risk of developing SPT when a patient was treated with surgery alone (p = 0.06). Moreover, the univariate analysis (Table 4) presented a reduced risk of developing a SPT in patients who were diagnosed with stage 4 disease compared to those who were diagnosed with stage 1–3 disease (HR 0.39, p = 0.05). Table 5 shows the results of the multivariate analysis for SPTs, with all-cause mortality as a competing risk event. When adjusted for primary tumor location and disease stage, the association between radiotherapy and survival was no longer statistically significant (p = 0.24).

Table 3.

Second primary tumor location according to the index tumor location (n = 31)

| Variables | Index tumor location |

p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rhinopharynx, nose and paranasal sinuses (n = 1) | oral cavity, oro-hypopharynx (n = 12) | Larynx (n = 18) | ||

| Second primary location, N (%) | ||||

| Oral cavity + oro-hypopharynx | 0 (0) | 8 (66.7) | 0 (0) | <0.001 |

| Lung + bronchi | 1 (100) | 1 (8.3) | 11 (61.1) | |

| Other | 0 (0) | 3 (25.0) | 7 (38.9) | |

Table 4.

Univariate analysis (Cox proportional hazard model) for characteristics associated with second primary tumors, with all-cause mortality as a competing risk event

| Variables | HR 1.02 | 95% CI 0.98–1.05 | p value 0.38 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| Gender (male as reference) | 1.53 | 0.71–3.28 | 0.28 |

| Ethnicity (Jewish as reference) | 1.17 | 0.39–3.49 | 0.77 |

| Smoking (past/current) | 0.90 | 0.41–1.95 | 0.79 |

| Alcohol (past/current) | 0.79 | 0.34–1.83 | 0.58 |

| Index tumor locations (with nasopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses, as reference group) Oral cavity, oro-hypopharynx | 3.24 | 0.43–24.14 | 0.25 |

| Larynx | 2.92 | 0.40–21.27 | 0.29 |

| Index tumor stage at diagnosis (stage 1–3 as reference) Stage 4 | 0.39 | 0.15–1.02 | 0.05 |

| Treatment modality (surgery alone as reference group) Radiotherapy alone | 0.47 | 0.15–1.51 | 0.21 |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy | 0.60 | 0.24–1.47 | 0.26 |

| Surgery + radiotherapy | 0.59 | 0.24–1.43 | 0.24 |

| Chemotherapy + radiotherapy + surgery | 0.18 | 0.02–1.46 | 0.11 |

| Any radiotherapy | 0.54 | 0.26–1.11 | 0.09 |

| Any chemotherapy | 0.65 | 0.30–1.42 | 0.28 |

| Surgery alone | 2.00 | 0.98–4.11 | 0.06 |

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis (Cox proportional hazard model) for second primary tumor, with all-cause mortality as a competing risk event

| Variables | HR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Index tumor locations (rhinopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses, as reference) | |||

| Oral cavity, oro-hypopharynx | 2.74 | 0.38–19.59 | 0.31 |

| Larynx | 2.57 | 0.38–17.56 | 0.33 |

| Any radiotherapy | 0.64 | 0.30–1.36 | 0.24 |

| Index tumor stage 4 (stage 1–3 as reference group) | 0.44 | 0.16–1.20 | 0.11 |

Discussion

The goal of this study was to assess the relationship between treatment modality for head and neck cancer and the occurrence of metachronous SPT. Previous studies demonstrated a protective effect of radiotherapy, with low SPT incidence [12, 13].

Two theories have been proposed to explain the development of SPT in head and neck cancer. The “Field Cancerization” theory, espoused by Slaughter et al. [17] in 1953, claims that the carcinogenic effects of tobacco and alcohol promote the development of several premalignant lesions, one of which develops to become the index tumor, and others later turn into SPTs. According to this paradigm, tumors, including head and neck squamous cell carcinomas, arise from premalignant cells in a successive process [18, 19]. As such, a patient diagnosed with head and neck carcinoma, unknowingly hosts premalignant cells in his/her aerodigestive mucosa. An alternative explanation for the presence of SPT is the “Second Field Tumor” theory, which claims that both index- and SP tumors arise from a common cell clone [20].

As with previous studies [12, 13], the univariate analysis of the current study demonstrated an association between radiotherapy and low SPT incidence, whereas chemotherapy was not associated with SPT development (Table 2). However, in a multivariate analysis, the relationship of SPT with radiotherapy was not statistically significant. Consistent with Gate's criteria, we defined SPT as being separated from the index tumor by healthy mucosa; the tumors were sometimes located in a completely different area. Consequently, the minimal boundaries maintained in radiotherapy for the primary tumor most probably have a minimal effect, if any, upon distant lesions.

Since we considered all-cause mortality as a competing risk event in our analysis, the lower rate of SPT in patients who had stage 4 tumors cannot be explained by early death. We speculate that stage 4 tumors may provoke such an intense immune response, which may cause suppression of other premalignant lesions (in the head and neck region). Further research, on a molecular level, is needed to examine such.

The cumulative incidence rate for SPT development was 16.8% for a period of 10 years, which is within the wide range mentioned in the literature, although on the lower side [3, 6, 7, 8, 9]. The application of competing risk analysis demonstrated lower results, but more accurate value estimation. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study that attempted to assess time to SPT according to treatment modality using this method.

The current study supports previous observations regarding an association between an index tumor and SPT locations [3, 6, 7]. Patients for whom the index tumor was located in the oral cavity or oro-hypopharynx tended to develop the SPT in the same region, whereas those who had the index tumor in the larynx tended to develop the SPT in the lungs and bronchi. These findings may be explained both by theories of field of cancerization and a mutagenic clone. However, the mutagenic clone theory seems more probable, since alcohol and tobacco are carcinogenic to both tracts and more cross carcinogenesis would thus be expected between the 2 tracts. However, the digestive tract and the airway are derived from different embryologic origin: the lower respiratory system begins its development during the fourth week, as an outgrowth of the ventral wall of the foregut (respiratory diverticulum). The endodermal lining of the respiratory diverticulum gives rise to the epithelial lining of the larynx, trachea, bronchi, and alveoli. In contrast, the oral cavity and oro-hypopharynx are derived from the pharyngeal gut, which extends from the buccopharyngeal (oropharyngeal) membrane to the respiratory (tracheobronchial) diverticulum [21]. These 2 pathways could explain the tendency of a second tumor to develop in a similar tract. Moreover, the majority of patients in our cohort were current or former smokers and are thus at high risk to develop lung malignancy. Since the lungs are part of the aerodigestive tract, they are subject to the same hazardous effects of tobacco. Thus, the field cancerization theory applies here, as to the rest of the tract.

Contrasting with a previous study [10], we did not find an association between the usage of alcohol or tobacco and the development of SPT [10]. Due to the relatively small sample size, we were not able to investigate the possibility that smokers and alcohol users may have died at a higher rate, and thus have less time to develop SPTs. In addition, since the study was intended to assess an association of treatment modalities with SPTs, we deliberately excluded synchronous tumors. We do not know if tobacco and alcohol users are at higher risk for synchronous SPTs.

Since our study design grouped together, all patients with head and neck tumors, we may have masked risk factors that are unique for each tumor and for each tumor location. Moreover, the classification we applied for different regions (nasopharynx, nose, and paranasal sinuses; oral cavity and oro-hypopharynx; and larynx) does not account for differences in the tumor behavior within these regions [17].

This study has several limitations: specific data regarding radiation treatment, such as margins of treatment, and total dose or fractions administered, were not collected. This limits the possibility of correlating the actual dose of radiation given with the occurrence of SPT. Another limitation relevant to ours and previous studies that investigated this subject is the relatively short follow-up periods. The hazardous effects of radiation, especially on DNA should be taken into account. There is no consensus as to whether radiotherapy itself can cause field cancerization rather than treating it. Nonetheless, even in studies that support a tumor promoting effect of radiotherapy, the latent period from radiotherapy until SPT development is around 10 years [14, 22]. The follow-up periods of the studies that report beneficial effects of radiation on SPT development are around 10 years, a time frame that is similar to the latent period. Further research, with a longer follow-up time, is thus needed to ensure that the addition of radiation to the treatment protocols does not promote tumor development in subsequent years. Our study, like most previous studies, did not characterize smoking habits and history. Smoking is inevitably a major risk factor for head and neck tumors. Nonetheless, the possibly long duration of this habit, with fluctuations over the years; the problem of accessing reliable information from individuals regarding their smoking habits; and the retrospective design of the study preclude achieving a precise understanding of the relationship between smoking and SPTs. Tobacco and alcohol could be strongly associated with SPT from a certain dose. Finally, this study pooled together different SPT sites. This may mask the potential carcinogenic or protective effect that primary radiotherapy may have locally; while it may cause local SPT, it seems highly unlikely that it will cause any change to distant sites (outside of the radiation field). Unfortunately, even in a time span of 13 years, the cohort that was established was not large enough to allow such subdivisions. Further research with a larger cohort (either due to longer time spans or a multicentric study) may allow such subdivision.

Not all patients treated at our institute were screened for HPV, as the lower incidences of SPT in patients with HPV malignancies were not recognized in the early 2000s [23, 24], the time frame of this study. To date, the use of Warren and Gates' criteria is the best way to differentiate SPT from a locoregional recurrence or a distant metastasis, without conducting DNA clonality tests. Due to the retrospective design of this study and the fact that DNA clonality tests are not routinely performed, we used Warren and Gates' criteria.

Conclusion

This study did not demonstrate an association between treatment modality and SPT occurrence. Further research is needed to elucidate factors that may contribute to the development of SPT and to decrease its occurrence.

Statement of Ethics

Ethics approval and consent to participate: the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Soroka University Medical Center (IRB number: 0170-12-SOR). The study did not require consent since it was retrospective without any intervention to the treatment.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors did not receive any funding.

Author Contributions

G.B.A. collected, analyzed, and was the main author of the study; T.S. analyzed and interpreted all patient data; O.B. and S.E.S. were major contributors in collection of data and writing the manuscript; B.Z.J. initiated and supervised the study and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Dr. Lital Keinan and Dr. Barbara Silverman from the Israeli National Cancer Registry for their collaboration, to Dr. Michael Nash for editing the manuscript, and to Professor Victor Novack for his insightful comments and assistance in finalizing the manuscript.

References

- 1.Head and Neck Cancer: Statistics. Cancer. Net. [cited 2017 Sep 14]. Available from: http://www.cancer.net/cancer-types/head-and-neck-cancer/statistics.

- 2.Hong WK, Lippman SM, Itri LM, Karp DD, Lee JS, Byers RM, et al. Prevention of second primary tumors with isotretinoin in squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N Engl J Med. 1990;323((12)):795–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009203231205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu PY, Chang SY, Huang JL, Tai SK. Different patterns of second primary malignancy in patients with squamous cell carcinoma of larynx and hypopharynx. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31((3)):168–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjoto.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marta S, Marina V. Prognostic impact of second primary tumors in head and neck cancer. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;273((7)):1871–7. doi: 10.1007/s00405-015-3699-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lippman SM, Hong WK. Second malignant tumors in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: the overshadowing threat for patients with early-stage disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1989;17((3)):691–4. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(89)90126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leon X, Quer M, Diez S, Orus C, Pousa AL, Burgues J. Second neoplasm in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck. 1999;21((3)):204–10. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0347(199905)21:3<204::aid-hed4>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gluckman JL, Crissman JD, Donegan JO. Multicentric squamous-cell carcinoma of the upper aerodigestive tract. Head Neck Surg. 1980;3((2)):90–6. doi: 10.1002/hed.2890030203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapshay SM, Hong WK, Fried MP, Sismanis A, Vaughan CW, Strong MS. Simultaneous carcinomas of the esophagus and upper aerodigestive tract. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88((4)):373–7. doi: 10.1177/019459988008800410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weaver A, Fleming SM, Knechtges TC, Smith D. Triple endoscopy: a neglected essential in head and neck cancer. Surgery. 1979;86((3)):493–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin K, Patel SG, Chu PY, Matsuo JM, Singh B, Wong RJ, et al. Second primary malignancy of the aerodigestive tract in patients treated for cancer of the oral cavity and larynx. Head Neck. 2005;27((12)):1042–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.20272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Di Martino E, Sellhaus B, Hausmann R, Minkenberg R, Lohmann M, Esthofen MW. Survival in second primary malignancies of patients with head and neck cancer. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116((10)):831–8. doi: 10.1258/00222150260293664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rusthoven K, Chen C, Raben D, Kavanagh B. Use of external beam radiotherapy is associated with reduced incidence of second primary head and neck cancer: a SEER database analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71((1)):192–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Erlend R, Ulf Z, Evensen J, Boysen M. Reduced risk of head and neck second primary tumors after radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol. 2009;93((3)):559–62. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashibe M, Ritz B, Le AD, Li G, Sankaranarayanan R, Zhang ZF. Radiotherapy for oral cancer as a risk factor for second primary cancers. Cancer Lett. 2005;220((2)):185–95. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Warren S, Gates O. Multiple primary malignant tumors, a survey of the literature and a statistical study. Am J Cancer. 1932;16:1358–414. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc. 1999;94((446)):496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Slaughter DP, Southwick HW, Smejkal W. Field cancerization in oral stratified squamous epithelium; clinical implications of multicentric origin. Cancer. 1953;6((5)):963–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(195309)6:5<963::aid-cncr2820060515>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hunter KD, Parkinson EK, Harrison PR. Profiling early head and neck cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5((2)):127–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mao L, Hong WK, Papadimitrakopoulou VA. Focus on head and neck cancer. Cancer Cell. 2004;5((4)):311–6. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braakhuis JM, Tabor MP, Leemans CR, Isaac vdW, Snow GB, Brakenhoff RH. Second primary tumors and field cancerization in oral and oropharyngeal cancer: molecular techniques provide new insights and definitions. Head Neck. 2002;24((2)):198–206. doi: 10.1002/hed.10042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Atlas of Human Embryology [cited 2017 Sep 14] Available from: http://www.chronolab.com/atlas/embryo/respiratory.htm.

- 22.Hall J, Angèle S. Radiation, DNA damage and cancer. Mol Med Today. 1999;5((4)):157–64. doi: 10.1016/s1357-4310(99)01435-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris LG, Sikora AG, Patel SG, Hayes RB, Ganly I. Second primary cancers after an index head and neck cancer: subsite-specific trends in the era of human papillomavirus-associated oropharyngeal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29((6)):739–46. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.8311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peck BW, Dahlstrom KR, Gan SJ, Caywood W, Li G, Wei Q, et al. Low risk of second primary malignancies among never smokers with human papillomavirus-associated index oropharyngeal cancers. Head Neck. 2013;35((6)):794–9. doi: 10.1002/hed.23033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]