Abstract

Backgrounds

Between 2009 and 2018, the number of opioid-related deaths (ORDs) in Scotland showed a dramatic increase, whereas in England and Wales, a much lower increase in ORD was seen. This regional difference is remarkable, and the situation in Scotland is worrisome. Therefore, it is important to identify the drivers of ORD in Scotland.

Methods

A systematic literature review according to PRISMA guidelines was conducted to identify peer-reviewed studies about key drivers for the observed differences in ORDs between Scotland and England/Wales. In addition, non-peer-reviewed reports on nationwide statistical data were retrieved via Google and Google Scholar and analysed to quantify differences in ORD drivers between Scotland and England/Wales.

Results

The systematic review identified some important drivers of ORD, but none of these studies provided direct or indirect comparisons of ORD drivers in Scotland and England/Wales. However, the reports with nationwide statistical data showed important differences in ORD drivers between Scotland and England/Wales, including a higher prevalence of people using opioids in a problematic way (PUOP), more polydrug use in people using drugs in a problematic way (PUDP), a higher age of PUDP, and lower treatment coverage and efficacy of PUDP in Scotland compared to England/Wales, but no regional differences in injecting drug use, incarceration/prison release without treatment, and social deprivation in PUDP.

Conclusion

It is concluded that the opioid crisis in Scotland is best explained by a combination of drivers, consisting of a higher population involvement in (problematic) opioid use (notably methadone), relatively more polydrug use (notably benzodiazepines and gabapentinoids), a steeper ageing of the PUOP population in the past 2 decades, and lower treatment coverage and efficacy in Scotland compared to England/Wales. The findings have important consequences for strategies to handle the opioid crisis in Scotland.

Keywords: Opioids, Drug dependence, Problem drug use, Drug-related death, Polydrug use, Injecting drug use, Incarceration

Introduction

In a recent review, trends in opioid prescription rates, prevalence rates of non-fatal and fatal opioid-related incidents, and opioid use disorder treatment in Germany, France, the UK, the Netherlands, and the USA were reported [1]. It was concluded that there is no threat of an opioid crisis in Europe similar in nature and/or magnitude to the current opioid crisis in the USA where high numbers of opioid-related deaths (ORDs) and increasing numbers of treatment-seeking opioid use disorder patients are observed [1]. In this review [1], we also noted, however, that Scotland is an exception with an ORD rate even higher than that in the USA. Furthermore, it became apparent that in Scotland, between 2009 and 2018, the number of drug-related deaths (DRDs), including ORDs, more than doubled resulting in the largest number ever recorded, whereas in England and Wales, a much smaller increase in DRDs were seen. A number of people and several agencies from the UK have urged their government to declare a public health crisis in response to the record number of drug-related poisonings in Scotland [2, 3, 4, 5, 6].

In a recent inquiry, the Scottish Affairs Committee, appointed by the House of Commons in Scotland, identified several key drivers of DRDs in Scotland, including polydrug use in people using drugs in a problematic way (PUDP; previously described as “problem drug users” or PDU), ageing of PUDP, low addiction treatment coverage and efficacy, high levels of injecting drug use, infrequent treatment during incarceration, and social deprivation [7]. However, no quantification of the differences in DRD/ORD drivers between Scotland and England/Wales was provided. In this study, we aimed to compare the prevalence of these drivers in Scotland and England/Wales to explain the observed ORD differences between these British regions.

Methods

Systematic Review Peer-Reviewed Studies

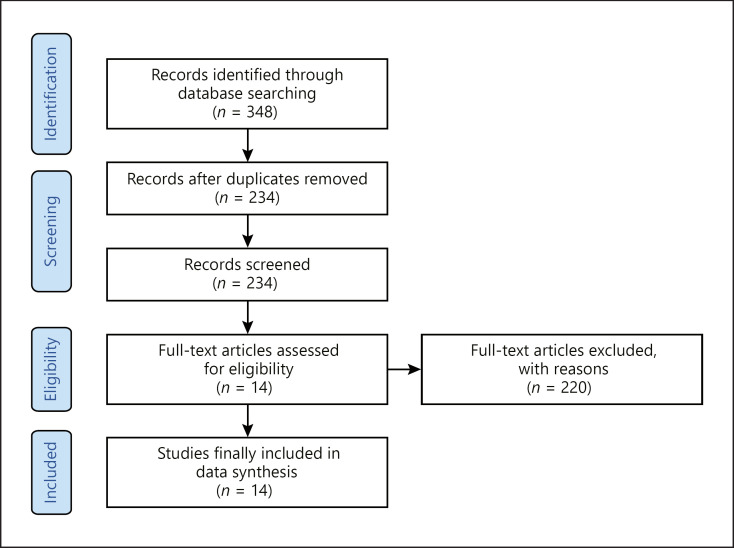

A systematic literature review was performed on 16 October 2020 using the PRISMA protocol to retrieve studies from Medline (PubMed) and PsycINFO (articles published or ahead of print from September 2010 to October 2020) on the following topics of interest: potential drivers of DRDs, ORDs, PUDP, people using opioids in a problematic way (PUOP), polydrug use in PUDP and PUOP, ageing of PUDP/PUOP, treatment coverage and treatment efficacy for patients with problematic opioid use, injecting drug use, treatment during incarceration, and social deprivation. Studies describing quantitative data about the topics of interest observed in Scotland and/or England/Wales were considered for inclusion if they were reported full text in Dutch, English, German, or French. The exclusion criteria were reviews, commentaries, and − as we aimed to collect population-based data − reports with a small sample size (<100 subjects). Two researchers (J.v.A. and M.P.) were involved in the selection of appropriate studies, which was executed in 2 rounds. Initially, 348 studies were retrieved of which 234 unique studies remained after removal of duplicates. These 234 studies were further processed, that is, the title and abstract were screened to determine eligibility applying the inclusion and exclusion criteria mentioned above. In a second round, the reference list of the selected 14 studies was checked for eligible studies. In total, 14 papers were finally included. Figure 1 shows the PRISMA diagram of the identification, screening, and inclusion of the reports. (See Figure 1 for flow diagram of the systematic search and “see online suppl. material; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000516165; for the PRISMA checklist.)

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram. Retrieval of eligible reports via the checking of reference list of the selected 14 studies was unsuccessful.

Review Non-Peer-Reviewed Studies

In addition, information from non-peer-reviewed sources (grey literature) reported in the last 10 years was retrieved via searches in Google and Google Scholar (J.v.A. and M.P.) using appropriate combinations of key words and Boolean operators, including “file:pdf.”Examples of key words that were used are Scotland, England, DRD, mortality, “drug mortality,” “opioid-related overdos*,” opioid, heroin, methadone, incarceration, persons who inject drugs (PWID), PDU, Opioid Substitution Treatment (OST), National Drug-Related Deaths Database (NDRDD), English' National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS), Scottish Drugs Misuse Database (SDMD), National Health Service (NHS), England/Wales' Office for National Statistics (ONS), Public Health England (PHE), Scottish' Information Services Division (ISD), Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (NESI), National Records of Scotland (NRS) and the Scottish Prison Service (SPS). This search resulted in several hundreds of potential useful hits/reports, the abstracts were screened, and reports were included if eligible. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were the same as described above for peer-reviewed studies. Note that the direct comparisons made in this review and their interpretations should be interpreted with caution due to small differences in definitions of DRD/ORD that were used in these reports. As such searches are not fully reproducible, the eligible non-peer-reviewed reports are not specified in Figure 1.

Via Google and Google Scholar, forty non-peer-reviewed reports from the SDMD, NRS, NDTMS, ISD, PHE, NESI, SPS, and ONS were retrieved (cf. reference list). These reports were crucial sources of national statistical data which allowed quantitative comparisons between Scotland and England/Wales regarding ORD and its presumed key drivers. Data from N-Ireland were not included because of the low availability of the relevant data.

Results

Below, we first describe the findings from the peer-reviewed studies, and then, we separately describe the findings from the non-peer-reviewed studies (grey literature).

Peer-Reviewed Studies

Table 1 summarizes the findings of the eligible peer-reviewed studies. These findings confirmed and underlined that at a population level the ageing of PUDP, injecting drug use, treatment during incarceration, and social deprivation were important risk factors of ORD. For instance, it was shown that in England, opioid users' excess mortality persisted into old age [8] and in patients receiving only psychological support for opioid dependence [9], whereas in Scotland, excess mortality was shown in HCV-diagnosed drug users [10]. Age-standardized rates for DRDs among young adults rose during the 1990s in Scotland, especially for males living in the most deprived areas [11], and a sharp age-related increase in the risk of methadone-specific death in the UK was noted between 2005 and 2009 [12]. Furthermore, in Scotland, older patients showed higher methadone-specific DRD rates [13], which was partly explained by the higher comorbidity of cardiovascular disease [14]. In England/Wales, drug injectors were at increased risk of DRD, considering that 15% of drug injectors reported overdosing during the preceding year [15]. In Scotland, patients discharged from inpatient drug dependence treatment [16], especially drug injectors [17], were at increased risk of DRD. On the other hand, both Scotland's National Naloxone Programme [18] and the introduction of OST in Scottish prisons [19] have reduced the number of DRDs by 35–40%. In England/Wales, buprenorphine as OST appeared to be 6 times safer than methadone with regard to overdose risk [20]. Finally, the English public treatment system for opioid use disorder annually prevented 880 ORDs [21]. It should be noted, however, that in none of these studies, a direct or indirect (quantitative) comparison was made between Scotland and England/Wales on the role of the different ORD drivers.

Table 1.

Description of included studies on DRD, PUDP, PUDP, polydrug use, age of PUDP, and treatment coverage and efficacy, injecting drug use, treatment during incarceration, and social deprivation

| No. | Sample | Time frame | Data source | Main results | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 150,517 | 1996–2007 | All people released from all Scottish prisons | Opioid substitution therapy in Scottish prisons decreased the rate of DRD by 40% | [19] |

|

| |||||

| 2 | 3,182 | 2006–2013 | NRS | Scotland's National Naloxone Programme was associated with a 36% reduction in the proportion of ORDs | [18] |

|

| |||||

| 3 | 33,128 | 2009–2013 | Scotland's Prescribing Information System and NRS | Higher methadone-specific DRD rates in older clients | [13] |

|

| |||||

| 4 | 3,262 | 2009–2015 | NRS | Circulatory disease as comorbidity most likely implicated in the 4-fold increase of methadone-specific DRD risk at 45+ yrs | [14] |

|

| |||||

| 5 | 2,418 | 2007–2012 | National databases for England and Wales | Buprenorphine is 6 times safer than methadone with regard to overdose risk | [20] |

|

| |||||

| 6 | 69,456 | 1996–2006 | SDMD | Drug users, especially those HCV-diagnosed showed an increased mortality risk | [10] |

|

| |||||

| 7 | 69,457 | 1996–2006 | Registration of drug treatment in Scotland | Discharge of people in treatment for drug dependence from hospitalization were at increased risk of DRD | [16] |

|

| |||||

| 8 | 3,850 | 2013–2014 | PWID survey | 15% of drug injectors reported overdosing during the preceding year | [15] |

|

| |||||

| 9 | Not specified | 1979–2013 | NRS | Age-standardized rates for DRDs among young adults rose during the 1990s in Scotland, especially for males living in the most deprived areas | [11] |

|

| |||||

| 10 | 198,247 | 2005–2009 | Drug treatment and criminal justice sources in England | Opioid users' excess mortality persists into old age | [8] |

|

| |||||

| 11 | 151,983 | 2005–2009 | NDTMS and ONS | Patients receiving only psychological support for opioid dependence in England were at greater risk of DRD | [9] |

|

| |||||

| 12 | 1,266 DRDs | 2005–2009 | NDTMS | Sharp age-related increase in the risk of methadone-specific death in the UK | [12] |

|

| |||||

| 13 | >98,000 | 1996–2010 | SDMD | Hospital-discharge gives increased DRD vulnerability, especially for drug injectors | [17] |

|

| |||||

| 14 | 3,731 | 2008–2011 | NDTMS and ONS | The English public treatment system for opioid use disorder prevented 880 deaths yearly from opioid-related poisoning | [21] |

NRS, National Records of Scotland; SDMD, Scottish Drug Misuse Database; NDTMS, National Drug Treatment Monitoring System in England; ONS, Office for National Statistics in England; ORD, opioid-related death; PUDP, people using drugs in a problematic way; PWID, persons who inject drugs.

PUDP and DRD/ORD in Scotland and England/Wales

To illustrate the unique position of Scotland and England/Wales within Europe and to provide a comparison with the situation in the USA, Table 2 shows DRD/ORD rates in the USA, Europe as a whole, and separate estimates for Scotland and England/Wales using numbers per 100,000 population to allow cross-country comparisons. DRDs are predominantly the consequence of risky drug consumption by people who use drugs in a problematic way (PUDP) and, therefore, the differences in the prevalence of PUDP should be considered when comparing DRD/ORD between certain countries or regions.

Table 2.

Scotland

The prevalence of PUDP in Scotland in 2015/2016 was 1,620 per 100,000 population [25] (see Table 3). In 2018, 1,187 DRDs were registered in Scotland (DRD = 33.6 per 100,000 population), and in 86%, one or more opioids, including heroin, morphine, and/or methadone, were implicated in or seen as potentially contributing to the death (ORD = 28.9 per 100,000) [26]. Methadone was implicated in about 47% of all DRDs (15.9 per 100,000) and heroin/morphine in 45% of all DRDs (15.2 per 100,000) (with some overlap) [26].

Table 3.

Comparison of the involvement of drugs in DRD in England/Wales versus Scotland in 2018

| England/Wales |

Scotland |

Ratio1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | rate | N | % | rate | ||

| Total DRD2 | 4,359 | 100 | 11.2 | 1,187 | 100 | 33.6 | 3.0 |

| Any opioid | 2,208 | 50.7 | 5.7 | 1,021 | 86.0 | 28.9 | 5.1 |

| Heroin/morphine | 1,336 | 30.6 | 3.4 | 537 | 45.2 | 15.2 | 4.4 |

| Methadone | 419 | 9.6 | 1.1 | 560 | 47.2 | 15.9 | 14.7 |

| Cocaine | 637 | 14.6 | 1.6 | 273 | 23.0 | 7.7 | 4.7 |

| Any benzodiazepine | 420 | 9.6 | 1.1 | 792 | 66.7 | 22.4 | 20.8 |

| Z-drugs | 143 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 24 | 2.0 | 0.7 | 1.8 |

| Gabapentinoids | 280 | 6.4 | 0.7 | 367 | 30.9 | 10.4 | 14.4 |

Rates are given per 100,000 adults aged 18 years and older. DRD, drug-related death.

Scotland versus England/Wales, as calculated by the authors.

4,359 DRDs in England/Wales and 1,187 DRDs in Scotland equals 7.4 and 21.8 DRDs per 100,000 population, respectively.

England/Wales

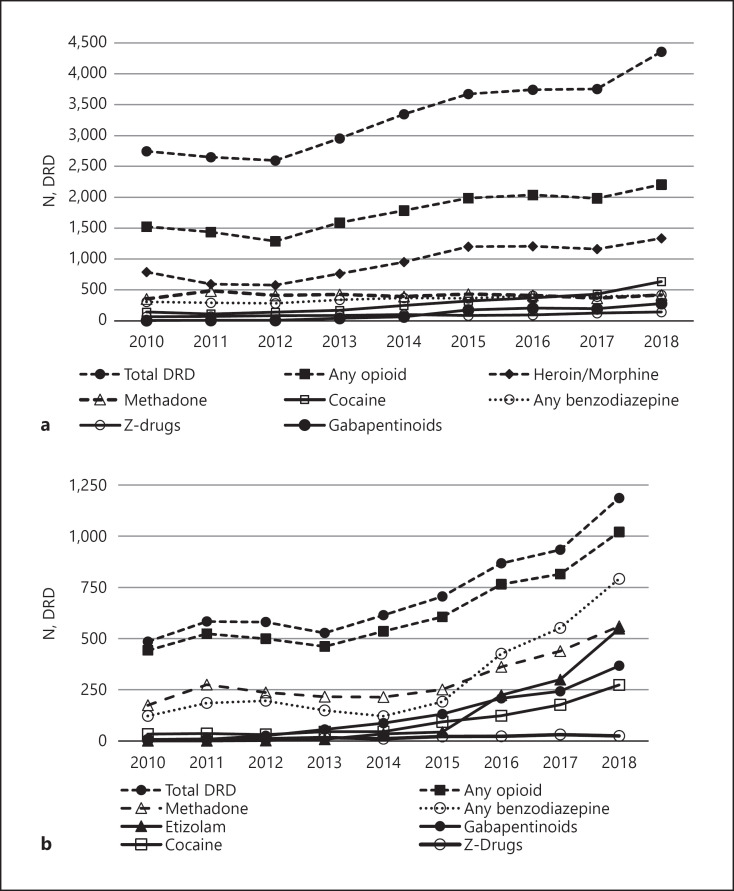

The prevalence of PUDP in England in 2018/2019 was 890 per 100,000 population [27]. In England/Wales, in 2018, the total number of DRD was 4,359 (11.2 per 100,000 population) with one or more opioids involved in 51% of all ORD (ORD = 5.7 per 100,000) [28]. Methadone was implicated in about 10% of all DRDs (1.1 per 100,000) and heroin/morphine in 31% of all DRDs (3.4 per 100,000) (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

a Number of DRD in England/Wales between 2010 and 2018 involving total DRD, opioids, any benzodiazepine, Z-drugs, cocaine, and gabapentinoids, like gabapentin and pregabalin [29]. Substances were implicated in or potentially contributed to DRD. b DRD in Scotland 2000–2018 involving total DRD, opioids, any benzodiazepine, like diazepam, etizolam, diclazepam, and gabapentinoids (gabapentin and pregabalin) [26, 30]. DRD, drug-related death.

Summary

The rate of PUDP in Scotland is almost 2 times that in England. From Table 2, it can be concluded that DRD/ORD rates in England/Wales are at the high end of the European range and those DRD and ORD rates in Scotland are similar to those in the USA. Importantly, the Scottish rates are much higher than those in England/Wales, notably for the total ORDs (rate ratio 5.1) and methadone-related ORD (rate ratio 14.7) (cf. Table 4). Even if one takes into account the higher rate of PUDP in Scotland than England (rate ratio = 1,620/890 = 1.82), there is still a much higher rate of ORD in Scotland than England/Wales (rate ratio = 28.9/5.7 = 5.07), despite important similarities of these regions in culture, language, and healthcare system (NHS).

Table 4.

Opioid-related data, including rates of PWID, across PUDP, aged 15–64 years in treatment in England 2018/2019 [27] and Scotland 2015/2016 [25, 31, 32]

| PUDP1 | England (N/rate) | Scotland (N/rate) | Rate ratio2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PUDP total number1 | 313,971 | 57,300 | − |

| PUDP rate per 100,000 adult population1 | 890 | 1,620 | 1.8 |

| Opioid-related PUDP (mainly heroin)1 | 261,294 | 57,300 | − |

| Opioid-related PUDP rate per 100,000 population1 | 720 | 1,620 | 2.3 |

| Mean age in 2018, yrs | 42.9 | 44.9 | |

| PWID, % of PUDP England 2011; Scotland 2006 | 43 | 43 | 1.0 |

| PWID (rate per 100,000 population) England 2011 Scotland 2006 | 375 | 680 | 1.8 |

| PWID, % of PUDP England 2015; Scotland 2009 | 40 | 27 | 0.7 |

| PWID (rate per 100,000 population) England 2015; Scotland 2009 | 340 | 450 | 1.3 |

| Mean age PUDP (2009–2018), yrs | 37.5–42.9 | 36.6–44.9 | |

| Increase in mean age of PUDP (2009 vs.2018), yrs | 5.4 | 8.3 | 1.5 |

| Mean age PUDP-entrants (2009–2018), yrs | 33.0–31.6 | 29.7–35.7 | |

| Mean age PUDP-entrants in 2018, yrs | 11.3 | 9.2 | 0.8 |

| PUDP in treatment: total number | 192,696 | 30,046 | |

| PUDP in treatment: mean age in 2018, yrs | 40.0 | 35.6 | 0.9 |

| PUDP in treatment: age 35–64 years, % | 68 | 64 | 0.9 |

| PUDP in treatment: males, % | 73 | 71 | 1.0 |

| Opioid-related PUDP in treatment: total number3 | 139,845 | 25,569 | |

| Opioid PUDP in treatment: % of total opioid PDU | 544 | 45 | 0.8 |

| Opioid PUDP in treatment: rate per 100,000 adult population | 385 | 724 | 1.9 |

PWID, persons who inject drugs; PDU, problem drug users; OST, opioid substitution treatment.

PUDP: people using drugs in a problematic way, previously described as PDU. Users of opiates (heroin, methadone, and other opiate drugs), crack cocaine, or both; does not include the use of powder cocaine. However, Scotland and England adopted different definitions for PDU [32] with PDU defined in Scotland as regular use of illegal opioids, benzodiazepines, or prescribed OST drugs. These data refer to 2016/2017 (England).

Ratio Scotland versus England.

Mentioned as main problematic drug, but more than one drug could be mentioned as primary problematic substance.

52% based on 136,701 opioid users receiving in 2016 OST out of 261,294 problem opioid users [33].

Comparison of Risk Factors between Scotland and England/Wales

Here, we present data on some of the known risk factors for ORD separately for Scotland and England/Wales in an attempt to identify potential drivers of the significantly higher ORD rate in Scotland than England/Wales, including potential differences in (a) polydrug use, (b) injecting drug use, (c) addiction treatment, (d) ageing, (e) incarceration, and (f) social deprivation.

Polysubstance Use and ORD

Central nervous system (CNS) depressants (benzodiazepines, Z-drugs, gabapentinoids, and alcohol) boost the effect of opioids [34] so that a lower opioid dose is required for the intended effect. With regard to benzodiazepines, it is important to note that in the UK, etizolam, which is ten times more potent than diazepam (Valium®), is often sold as “street Valium.” Z-drugs (e.g., zolpidem and zopiclone) are non-benzodiazepines that are used to treat anxiety and insomnia. Although depressants are usually not lethal by themselves, they pose a significant additional risk for ORDs when co-ingested with opioids [35].

Scotland

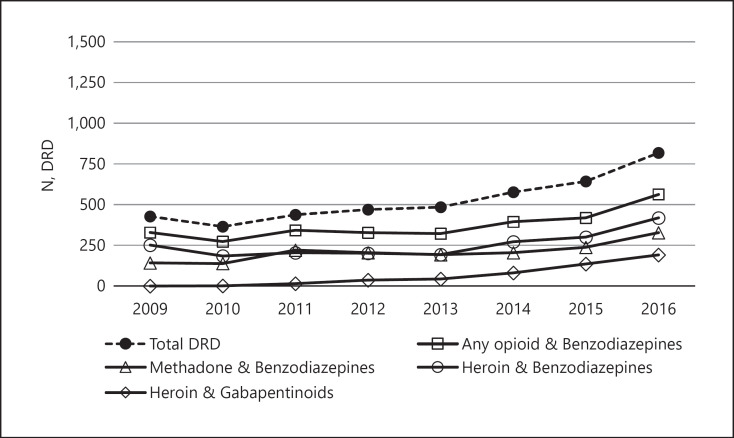

As in the rest of the UK, Scottish PUDP mainly purchase their benzodiazepines (“street benzos”), benzodiazepine derivatives (notably etizolam), and gabapentinoids on the black market [35]. Since 2013, co-use of CNS depressants has strongly contributed to DRDs in Scotland (Fig. 2b). In 2018, benzodiazepines and etizolam were implicated in 67% of all DRDs and in 78% of all ORDs, and gabapentinoids in 31% of all DRDs and in 36% in all ORDs (Table 4), while alcohol was − according to the available data − implicated in only 13% of all DRDs [26]. In 2018, only one drug (and sometimes also alcohol) was found in post-mortem toxicology in 6% of all DRDs and was believed to be implicated in or potentially contributed to the cause of death in 15% of all DRDs [26]. The most common combination (69%) of drugs found during post-mortem toxicology in all DRDs in 2016 consisted of an opioid (heroin, morphine, methadone, or buprenorphine) and a benzodiazepine, with heroin combined with benzodiazepines being most prevalent (51%). It is unclear whether the drugs were used in combination simultaneously or taken at different times. The combination of heroin and gabapentinoids has also become increasingly popular (23% in 2016) [36]. Between 2010 and 2018, the number of DRDs involving any opioid correlated positively with that involving benzodiazepines (r2 = 0.83), etizolam (r2 = 0.87), and gabapentinoids (r2 = 0.89), indicating frequent co-ingestion of antidepressants and opioids. Finally, whereas diazepam was present in 70% of Scotland's DRDs in 2013 or 2014, it was prescribed in the past 30 days in only 15% of DRD victims [37], indicating that the drug was predominately illicitly acquired.

England/Wales

The proportion of deaths involving only heroin/morphine (with or without alcohol) remained relatively stable between 1993 and 2000 (median 75%) but declined to 49% in 2016 [38], indicating an increase in DRDs involving combinations of multiple drugs in England/Wales. Between 2010 and 2018, the involvement of benzodiazepines in DRDs in England/Wales was stable at around 11% of all DRDs (9.6% in 2018), while that of Z-drugs and gabapentinoids increased to 3.3 and 6.4%, respectively, in 2018 [29, 34, 38] (Table 4). In 2012/2013, 96% of benzodiazepine deaths involved another substance, mainly opiates (87%) [39]. Furthermore, among heroin deaths, there is a clear trend towards increased co-ingestion of other substances, including alcohol, benzodiazepines, and methadone [39].

Summary

In summary, benzodiazepines, benzodiazepine derivatives (notably etizolam), Z-drugs, and gabapentinoids were much more frequently present in DRDs and ORDs in Scotland than in England/Wales, with rate ratios of 20.8, 1.8, and 14.4, respectively (Table 4).

Injecting Drug Use

Injecting drug use (and the related risk of blood-borne infections) is a known risk factor in DRDs and ORDs [40].

Scotland

In 2006, injecting drug use was highly prevalent among Scottish PUDP, where 43% of all PUDP (23,933 out of 55,100; 680 per 100,000 population) injected opioids and/or benzodiazepines [41] (Table 3). In 2016, 56% of all DRDs were PWID [42]. At the time of death, female ORDs were consistently more likely to be PWID than male ORDs, and thus, female users were at a higher risk than male users to die from drug overdose [42]. Interestingly, PWID was much more common in PUDP treatment entrants ≥35 years (55%) than in those <25 years (19%) (ISD, 2020a), which implies a higher risk in the older age group for blood-borne infections and related mortality. Fortunately, the proportion of current PWID among PUDP entrants in Scotland has declined 2-fold since 2006/2007 to 13% in 2018/2019 [43]. On the other hand, the average age of PWID has gradually increased since 2008/2009 with almost three-quarters of PWID aged 35 years or older in 2017/2018, suggesting an ageing cohort of people who inject drugs in Scotland [44].

England/Wales

In 2011 in England, 43% of the 315,000 PUDP (n = 135,000: 375 per 100,000 population) were PWID [27, 45] (Table 3). The most commonly injected drugs were heroin (91%) and crack (45%) [15]. Among relatively young drug users injecting drugs became less popular between 2007 and 2017, so the percentage of PWID younger than 25 years decreased from 15% of total PWID in 2007 to 3% in 2017 [46].

Summary

The percentage of PWID in PUDP was similar in Scotland and England/Wales, and fortunately, the percentage of PWID has recently decreased in both constituencies.

Addiction Treatment

There is ample evidence that (stable) OST reduces the risk of ORD, but methadone induction and OST discontinuation may (temporarily) increase the risk of ORD (e.g., [31, 47]).

Scotland

In Scotland, 25,569 of all 57,300 PWOP (45%; 724 per 100,000 population) were in addiction treatment in 2016 (Table 3). In Scotland, methadone is (still) the most (91%) prescribed opioid substitute in OST [48]. In 2018, methadone was involved in 47% of all DRDs in Scotland [49] (Fig. 2b; Table 4). In 2016 in 78% of methadone-related DRDs, the victim was in OST with supervised methadone prescribing for one year or more, and in at least 67%, the prescribed dose was adequate [42]. It should be noted, however, that another illicit drug (notably, heroin/morphine, etizolam, and/or gabapentin) was detected at post-mortem toxicology in all, but 2, of these methadone-related DRDs [42].

In Scotland, about 95% of PUDP entrants were admitted for treatment within 3 weeks or less [50], although in 2019, a quarter of Scottish applicants still had to wait for up to 18 weeks or more before initiating treatment [50]. Additional problems in addiction care were the high rate of people who “did not attend,” the poor compliance among those engaged with OST, the high rate of “cycle in and out,” and the high number of “unplanned discharges” [5, 51]. This is worrisome, since instable OST with repeated methadone initiations and frequent opioid substitution discontinuations are a specific risk for ORDs (e.g., [47]). The supply rate of take-home naloxone (THN kits) in Scotland and England was comparable with 120–137 kits per 1,000 PUDP in 2017/2018 [33, 52, 53].

England/Wales

In England/Wales, 139,845 of all 261,294 PWOP (54%; 385 per 1,000,000 population) were in treatment in 2016 [27] (Table 2) and 52% (136,701 patients) were receiving OST [53]. According to figures of PHE, the proportion of opiate users in treatment in England is 60%, and 98% of opioid treatment entrants in England had to wait in 2017–2018 three weeks for the first and the subsequent interventions; 94% of opioid only dependent patients in treatment were prescribed OST, typically methadone or buprenorphine [27].

Summary

OST coverage appears rather similar in Scotland (45%) and England/Wales (54%), but caution is needed since there may be methodological differences in the estimation of the denominator, that is, the number of PWOP. The same is true for the similarity in the supply of THN kits.

Ageing

Age is an important risk factor for DRDs and ORDs since the increasing mean age in the 2 groups is associated with a higher rate of PWID [43, 44] and more chronic illnesses [10, 14, 36, 43, 44].

Scotland

Using all available data and after we performed some extrapolations, the mean age(s) of PUDP and their ranges between 2009 and 2018 were determined. Median age of PUDP and PUDP entrants, that is, those entering treatment, increased between 2009 and 2018 from 36.6 to 44.9 years and from 29.7 to 35.7 years, respectively [43]. As such, the Scottish cohort of PUDP is ageing, and the duration of PUDP is getting longer, that is, three-quarters of all DRDs had used drugs for at least 10 years with over half of them for 20 years or more [54]. The median age of all DRDs in Scotland increased between 2009 and 2018 from 37.0 to 42.5 years [26], with the highest mortality rates in the higher age groups (Fig. 3). In 2018, three-quarters of all DRDs were aged 35 or older, whereas in the early 2000s, their proportion was still approximately 35% [26].

Fig. 3.

DRD in Scotland involving combination of drugs (2010–2016) [26, 42]. Benzodiazepines, like diazepam, etizolam, and diclazepam. No data available for 2017–2019. DRD, drug-related death.

Of particular interest is that ORD rates involving methadone increased with age [12, 13], suggesting that older users are more susceptible to methadone overdosing. It is also of interest that methadone and gabapentinoids were less involved in younger (<35 years) (33 vs. 22%, respectively) than in older DRD victims (≥35 years) (52 and 34%, respectively) [26, 30], whereas the rates were independent of age for other opioids and benzodiazepines, except that opioids were less often involved in those aged younger than 25 years. Finally, the percentage THN recipients aged 45 years or older doubled from 9% in 2015/2016 to 19% in 2017/2018, providing another indication of ageing of the opioid-related PUDP population in Scotland [33].

England/Wales

In England between 2009 and 2018, the median age of PUDP increased from 37.5 to 42.9 years and the median age of PUDP in treatment increased from 37.5 to 40.0 years. Interestingly, 78% of PUDP in treatment for opiates was aged 35 years or older. Together, these data suggest that the group of PUDP in England/Wales is ageing. Indeed, in 2017/2018, 69% of people in treatment for opiates had already used heroin for almost 20 years [27]. In England/Wales, the median age of DRDs increased between 2009 and 2018 from 42.6 to 45.2 years [29]. In 2018, the DRD rate per 100,000 population was highest in the age groups of 30–39 years (9.9) and 40–49 years (12.6), whereas the rate for those younger than 20 years and the group of 20–29 years was 0.4 and 5.0, respectively.

Summary

Both in Scotland and in England/Wales, the median age of PUDP and PWOP, and DRDs is increasing in the last decade; however, a slightly higher speed of change and current median ages are observed in Scotland.

Incarceration

Recent prison release, particularly within the first 4 weeks after release, when individuals are commonly on parole, is another frequently reported risk factors for ORDs [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61]. Ex-prisoners are in danger, especially on the first day of their release when they want to “celebrate” their regained freedom. Incarcerated people with past opioid use and pre-sentence daily opioid use showed an increased ORD risk (RR = 3.5) upon release from prison [60], and from all deaths after prison release, almost 20% were drug-related [62], suggesting immediate provision of OST or NTH kits could have a substantial effect on reducing ORDs.

Scotland

In 2017/2018, Great Britain had the highest incarceration rate in western Europe with 174 and 166 prisoners per 100,000 population in England/Wales and Scotland, respectively (HoCL, 2019). The prevalence of opioid use in Scottish prisoners is very high with 28% of the prisoners testing positive for illicit opioids on reception [63, 64] and about half with a history of drug dependence [65]. Of all prisoners, 20 and 28% had been prescribed methadone or offered drug treatment, respectively [65], implicating that virtually all opioid-dependent prisoners were in treatment for their addiction. Following the introduction of a prison-based OST policy in Scotland, DRDs in the 12 weeks following release were reduced by 49% [19].

England

The most recent available report on drug use in English/Welsh prisons covers the year 1998 [66, 67]. It showed that 31–43% of male and 39–66% of female (remand and sentenced) prisoners had used opioids in the 12 months before imprisonment and that around half of them was drug-dependent with high rates of ever injecting drugs (23–40%). A more recent study confirmed the high rate of drug dependence (57%) among prisoners in London [65, 68]. In the Surveying Prisoner Crime Reduction study performed in 2005/2006 in England/Wales, 40% of the imprisoned responders reported to have ever used heroin [69]. Of around 89,000 people in secure settings in 2016/2017, 59,258 adults (63% of total) were in contact with drug and alcohol treatment services, with half of them (29,626; 33% of total) for problem opioid use, of whom 79% received OST. Only 16% of opioid users leaving prison were discharged as having completed treatment, and 65% of discharged opioid users were referred to treatment services in the community on release (PHE, 2018).

Summary

England/Wales and Scotland have similar (high) rates of imprisonment (about 170 per 100,000 population), and in both prison populations, drug dependence is frequent (about 50%) with similar rates in both countries. There were also similar OST treatment rates in opioid-dependent prisoners (around 80%) in Scotland and England/Wales.

Deprivation

Poverty and PUDP operate synergistically and are − at the extreme end − reinforced by psychiatric disorders and unstable housing or homelessness. There are clear differences in DRD rates by deprivation, with higher rates for those living in more deprived areas [37], and therefore, it seems that deprivation is an important indirect driver of DRDs. DRD mainly occurs in PUDP who live in socio-economically deprived areas characterized by long-term poverty, social isolation, broken families, depression, marginalization, unemployment, and homelessness [6, 7, 70]. However, the question is whether PUDP in Scotland are more socially deprived than those in England/Wales and whether regional differences in social deprivation is a driver of the higher rate of ORDs in Scotland than England//Wales.

Scotland

In general, Scotland belongs to the poorest areas in the UK [71] and has poorer health outcomes than other areas in Britain [72]. For instance, Glasgow in particularly fares significantly worse when compared to English cities of similar social and economic history (Manchester and Liverpool). Half of people died from DRDs lived in the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods in Scotland [36]. The large impact of deprivation on DRD is well illustrated by the observation that 53% of 195 homeless deaths in 2018 were drug-related [73]. Furthermore, the Scottish Burden of Disease Study found that the overall burden of drug use disorders is 17 times higher in Scotland's most deprived than its least deprived areas [74].

England/Wales

Over the last decade, the rate of drug misuse has more than doubled in the north east, one of the most deprived areas of England [28]: DRDs increased from 46.3 per million in 2008 to 96.3 per million population in 2018), a higher rate than that in any other English region or Wales [29].

Summary

Problem drug use and DRD/ORD are more prevalent in socio-economically deprived areas both in Scotland and England/Wales, but no valid data are available to assess the role of social deprivation as a possible driver of the Scottish opioid crisis.

Summary and Conclusion

The explanation for the dramatic 5-fold higher ORD rate in Scotland versus England/Wales appears to be multifactorial. The results of the peer-reviewed studies showed (again) that ageing of PUDP/PUOP, injecting drug use, lack of treatment during incarceration, and social deprivation were important risk factors of DRDs/ORDs. However, in none of these studies, a direct and quantified comparison was made of the key drivers of ORD between Scotland and England/Wales, and therefore, these studies were not able to contribute to a better understanding of the regional differences in ORDs. However, analysis of existing non-peer-reviewed reports showed that the ORD rate in Scotland was indeed much higher than that in England/Wales (RR = 5.1), especially for heroin/morphine-related (RR = 4.4.) and methadone-related (RR = 14.7) deaths, and that this regional difference would remain after controlling for the higher rate of PUOP in Scotland than England/Wales (RR = 2.3), indicating that people in Scotland have a higher risk to become a PUOP, and once PUOP, they have a higher risk to die from an opioid overdose. Possible drivers for this latter risk included (1) higher rates of co-use of other CNS depressants in Scotland (benzodiazepines RR = 20.8, gabapentinoids RR = 14.4, and Z-drugs RR = 1.8); (2) a more limited access to opioid dependence treatment (45 vs. 54%) and a lower efficacy of these treatments in Scotland; and (3) a steeper ageing and a mean higher age of PUOP in Scotland than England/Wales (45 vs. 43 years). There were no clear regional differences in injecting drug use or incarceration and prison OST between Scotland and England/Wales, and therefore, their role as drivers of the Scottish opioid crisis is probably limited. PUDP and DRD/ORD are more prevalent in socio-economically deprived areas both in Scotland and England/Wales, but no valid data were available to assess the role of social deprivation as a possible driver of the Scottish opioid crisis.

Another point of concern is the high and increasing use of benzodiazepines, gabapentinoids, and especially the benzodiazepine derivative etizolam in opioid users in Scotland compared to England and Wales. There is no explanation for this difference in the literature, and therefore, we advocate to further investigate the possible reasons of this difference and its implication for the prevention of DRD.

To halt the relentless increase in drug deaths in Scotland, it is advocated to develop and apply an evidence-based drugs policy, based on an efficient addiction treatment system that is also able to capture and treat PUDP living in the most deprived areas. To be successful, this treatment should combine OST and psychosocial care, including housing and day activities/work, safe consumption facilities, availability of THN kits, and the introduction of heroin-assisted treatment for therapy-resistant OST patients (e.g., [3, 75, 76]), in addition, awareness-building about the dangers of injection drug use and the combined use of opioids with other depressants (alcohol, benzodiazepines, etizolam, and gabapentinoids). Etizolam is often manufactured domestically, but benzodiazepines and gabapentinoids are often prescribed together with opioids, and vice versa, and partly diverted to the black market. Restricted prescribing of opioids and other depressants (without depriving those in need from their medication) is another important step in the battle against opioid overdose deaths in Scotland. In summary, we need general societal measures to reduce social inequality, poverty and deprivation, awareness programs about the risks of injecting and polydrug use, and an extension and improvement of the addiction treatment services. Only such a concerted action can be successful in solving the opioid crisis in Scotland. The Scottish opioid crisis and the recommendations to escape from it also show us the way to prevent the development of similar situation in other European countries: take (better) care of the most deprived part of your population, take (better) care of rational medicine prescription programs, and take (better) care of existing addiction treatment services (even in times of economic scarcity).

Statement of Ethics

An ethics statement was not required for this study type, and no human or animal subjects were used.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Prof. Wim van den Brink is the editor-in-chief of EAR and reports personal fees from Lundbeck, Novartis, D&A Pharma, Takeda, Mundipharma, Angelini, Opiant, and Idivior for services outside the submitted work. Dr. Jan van Amsterdam and Dr. Mimi Pierce report no conflict of interest.

Funding Sources

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions

Dr. Jan van Amsterdam and Dr. Mimi Pierce performed the systematic search and drafted the paper. Prof. Wim van den Brink critically corrected and completed the final version.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary data

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to our Scottish colleagues Lee Barnsdale, Lesley Graham, Elaine Parry, and Linsey Galbraith who were so kind to take ample time to answer our detailed questions about their reports.

References

- 1.van Amsterdam J, Pierce M, van den Brink W. Is Europe facing an emerging opioid crisis comparable to the US? Ther Drug Monit. 2021;43((1)):42–51. doi: 10.1097/FTD.0000000000000789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kimber J, Hickman M, Strang J, Thomas K, Hutchinson S. Rising opioid-related deaths in England and Scotland must be recognised as a public health crisis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6((8)):639–40. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30209-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nicholls J, Cramer S, Ryder S, Gold D, Priyadarshi S, Millar S, et al. The UK government must help end Scotland's drug-related death crisis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6((10)):804. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30301-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.SDF. The shame of a national scandal. Lack of access to treatment and prescribing practice contribute to drug death figures. 2019. Available from: https://drns.ac.uk/files/2019/07/Drug-related-deaths-in-Scotland-2018-SDF-Press-Release.pdf.

- 5.McAuley A. Scotland's overdose crisis. A public health emergency. Presentation at the Annual meeting of the EMCDDA expert network on drug-related deaths; 2019. Available from: https://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/attachments/12054/1.1.%20Andrew%20McAuley_Update%20on%20the%20general%20overdose%20crisis%20in%20Scotland.pptx.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.ACMD. Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) Reducing opioid-related deaths in the UK. 2016. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/576560/ACMD-Drug-Related-Deaths-Report-161212.pdf.

- 7.House of Commons. Scottish Affairs Committee of the House of Commons Problem drug use in Scotland. First report of session 2019. 2019. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201919/cmselect/cmscotaf/44/44.pdf.

- 8.Pierce M, Bird SM, Hickman M, Millar T. National record linkage study of mortality for a large cohort of opioid users ascertained by drug treatment or criminal justice sources in England, 2005–2009. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;146:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.09.782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pierce M, Bird SM, Hickman M, Marsden J, Dunn G, Jones A, et al. Impact of treatment for opioid dependence on fatal drug-related poisoning: a national cohort study in England. Addiction. 2016;111((2)):298–308. doi: 10.1111/add.13193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merrall EL, Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Mortality of those who attended drug services in Scotland 1996–2006: record-linkage study. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23((1)):24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parkinson J, Minton J, Lewsey J, Bouttell J, McCartney G. Drug-related deaths in Scotland 1979–2013: evidence of a vulnerable cohort of young men living in deprived areas. BMC Public Health. 2018;18((1)):357. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pierce M, Millar T, Robertson JR, Bird SM. Ageing opioid users' increased risk of methadone-specific death in the UK. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;55:121–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L, Dimitropoulou P, Robertson JR, McTaggart S, Bennie M, Bird SM. Risk-factors for methadone-specific deaths in Scotland's methadone-prescription clients between 2009 and 2013. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;167:214–23. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.08.627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gao L, Robertson JR, Bird SM. Non drug-related and opioid-specific causes of 3,262 deaths in Scotland's methadone-prescription clients, 2009–2015. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;197:262–70. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O'Halloran C, Cullen K, Njoroge J, Jessop L, Smith J, Hope V, et al. The extent of and factors associated with self-reported overdose and self-reported receipt of naloxone among people who inject drugs (PWID) in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;46:34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Merrall EL, Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. A record-linkage study of drug-related death and suicide after hospital discharge among drug-treatment clients in Scotland, 1996–2006. Addiction. 2013;108((2)):377–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.White SR, Bird SM, Merrall EL, Hutchinson SJ. Drugs-related death soon after hospital-discharge among drug treatment clients in Scotland: record linkage, validation, and investigation of risk-factors. PLoS One. 2015;10((11)):e0141073. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bird SM, McAuley A, Perry S, Hunter C. Effectiveness of Scotland's National Naloxone Programme for reducing opioid-related deaths: a before (2006–10) versus after (2011–13) comparison. Addiction. 2016;111((5)):883–91. doi: 10.1111/add.13265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bird SM, Fischbacher CM, Graham L, Fraser A. Impact of opioid substitution therapy for Scotland's prisoners on drug-related deaths soon after prisoner release. Addiction. 2015;110((10)):1617–24. doi: 10.1111/add.12969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marteau D, McDonald R, Patel K. The relative risk of fatal poisoning by methadone or buprenorphine within the wider population of England and Wales. BMJ Open. 2015;5((5)):e007629. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.White M, Burton R, Darke S, Eastwood B, Knight J, Millar T, et al. Fatal opioid poisoning: a counterfactual model to estimate the preventive effect of treatment for opioid use disorder in England. Addiction. 2015;110((8)):1321–9. doi: 10.1111/add.12971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van Amsterdam JGC, Pierce M, van den Brink W. Is Western Europe facing an emerging opioid crisis comparable to that in the US? Submitted. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Hedegaard H, Minino AM, Warner M. Drug Overdose Deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief No. 2020;356 Retrieved from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db356-h.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.EMCDDA. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) European Drug Report 2019. Trends and Developments. Lisbon: EMCDDA; 2019. Jun, Retrieved from: http://www.emcdda.europa.eu/system/files/publications/11364/20191724_TDAT19001ENN_PDF.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 25.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland Prevalence of problem drug use in Scotland 2015/16 estimates. 2019. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2019-03-05/2019-03-05-Drug-Prevalence-2015-16-Report.pdf https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2019-03-05/2019-03-05-Drug-Prevalence-2015-16-Tables.xlsx.

- 26.NRS. National Records of Scotland (NRS) Drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2018. 2019. Available from: www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/deaths/drug-related-deaths-in-scotland.

- 27.PHE. Public Health England (PHE) National Statistics. Substance misuse treatment for adults: statistics 2018 to 2019. Statistics on alcohol and drug misuse treatment for adults from PHE's National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) 2019. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/substance-misuse-treatment-for-adults-statistics-2018-to-2019/adult-substance-misuse-treatment-statistics-2018-to-2019-report https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/787918/OpiateCrackUsePrevalenceEstimates2016to2017.XLSX https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/845969/NDTMS_adult_report_supporting_tables_2018-19.ods.

- 28.ONS. Office National Statistics (ONS) English indices of deprivation 2019. 2019. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/835115/IoD2019_Statistical_Release.pdf.

- 29.ONS. Office for National Statistics (ONS) Deaths related to drug poisoning in England and Wales: 2018 registrations. 2019. Available from: www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/bulletins/deathsrelatedtodrugpoisoninginenglandandwales/2018registrations https://www.ons.gov.uk/visualisations/dvc666/smallmultiplelines/project/datadownload.xlsx; https://www.ons.gov.uk/file?uri=%2fpeoplepopulationandcommunity%2fbirthsdeathsandmarriages%2fdeaths%2fdatasets%2fdeathsrelatedtodrugpoisoningenglandandwalesreferencetable%2fcurrent/2018drugpoisonings.xlsx.

- 30.NRS. National Records of Scotland (NRS) Drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2018. 2019. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/drug-related-deaths/2018/drug-related-deaths-18-pub.pdf.

- 31.Sordo L, Barrio G, Bravo MJ, Indave BI, Degenhardt L, Wiessing L, et al. Mortality risk during and after opioid substitution treatment: systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. BMJ. 2017;357:j1550. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bird SM, King R. Multiple systems estimation (or capture-recapture estimation) to inform public policy. Annu Rev Stat Appl. 2018;5:95–118. doi: 10.1146/annurev-statistics-031017-100641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland National naloxone programme Scotland. 2018. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2018-11-27/2018-11-27-Naloxone-Report.pdf.

- 34.Lyndon A, Audrey S, Wells C, Burnell ES, Ingle S, Hill R, et al. Risk to heroin users of polydrug use of pregabalin or gabapentin. Addiction. 2017;112((9)):1580–9. doi: 10.1111/add.13843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson CF, Barnsdale LR, McAuley A. Investigating the role of benzodiazepines in drug-related mortality. A systematic review undertaken on behalf of the Scottish national forum on drug-related deaths. Scotland: NHS Health Scotland; 2016. Available from: https://www.scotpho.org.uk/media/1159/scotpho160209-investigating-the-role-of-benzodiazepines-in-drug-related-mortality.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 36.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland National drug-related deaths database (Scotland) report 2015, 2016. 2018. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2018-06-12/2018-06-12-NDRDD-Tables.xlsx https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2018-06-12/2018-06-12-NDRDD-Report.pdf.

- 37.Barnsdale L, Gordon R, Graham L, Elliott V, Graham B. The national drug-related deaths database (Scotland) report: analysis of deaths occurring in 2014. Information services division Scotland. 2016. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2016-03-22/2016-03-22-NDRDD-Report.pdf.

- 38.Handley S, Ramsey J, Flanagan R. Substance misuse-related poisoning deaths, England and Wales, 1993–2016. Drug Sci Policy Law. 2018;4:2050324518767445. [Google Scholar]

- 39.PHE. Public Health England (PHE) Trends in drug misuse deaths in England, 1999 to 2014. 2016. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/669620/Trends_in_drug_misuse_deaths_in_England_from_1999_to_2014.pdf.

- 40.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Bucello C, Lemon J, Wiessing L, Hickman M. Mortality among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91((2)):102–23. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.108282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hay G, Gannon M, Casey J, McKeganey N. Estimating the national and local prevalence of problem drug misuse in Scotland. Information services division, NHS Scotland. Executive report. 2009. Available from: http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/45433/3/45433.pdf.

- 42.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland National drug-related deaths database (Scotland). Report analysis of deaths occurring in 2015 and 2016. 2018. Available from: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2018-06-12/2018-06-12-NDRDD-Report.pdf https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Drugs-and-Alcohol-Misuse/Publications/2018-06-12/2018-06-12-NDRDD-Tables.xlsx.

- 43.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland Scottish drug misuse database (SDMD) overview of initial assessments for specialist drug treatment 2018/19. 2020. Available from: https://beta.isdscotland.org/media/3878/2020-03-03-sdmd-report.pdf https://beta.isdscotland.org/media/3879/2020-03-03-sdmd-tables.xlsx.

- 44.NESI. Needle Exchange Surveillance Initiative (NESI) Health protection Scotland, Glasgow Caledonian University and the West of Scotland specialist virology centre. The needle exchange surveillance initiative (NESI): Prevalence of blood-borne viruses and injecting risk behaviours among people who inject drugs (PWID) attending injecting equipment provision (IEP) services in Scotland, 2008–09 to 2017–18. Glasgow: Health Protection Scotland; 2019. Available from: https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2721/documents/1_NESI%202018.pdf https://hpspubsrepo.blob.core.windows.net/hps-website/nss/2721/documents/4_NESI%20Report%20Tables%202018.xlsx. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris RJ, Harris HE, Mandal S, Ramsay M, Vickerman P, Hickman M, et al. Monitoring the hepatitis C epidemic in England and evaluating intervention scale-up using routinely collected data. J Viral Hepat. 2019;26((5)):541–51. doi: 10.1111/jvh.13063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.PHE. Public Health England (PHE) People who inject drugs: HIV and viral hepatitis unlinked anonymous monitoring survey tables (psychoactive) 2018. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/729816/UAM_Survey_of_PWID_data_tables_2018.pdf.

- 47.Buster MC, van Brussel GH, van den Brink W. An increase in overdose mortality during the first 2 weeks after entering or re-entering methadone treatment in Amsterdam. Addiction. 2002;97((8)):993–1001. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2002.00179.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.NHS Scotland. National Health Services (NHS) Scotland Information services division. Methadone patient analysis for 2011/12 to 2018/19. Prescribing information system, ISD Scotland. 2019. Available from: https://www.scotpho.org.uk/media/1874/201819-methadone-patient-estimates.xlsx.

- 49.NRS. National Record of Scotland (NRS) Drug-related deaths in Scotland in 2018. Drug-related deaths by selected drugs reported Scotland, 1996–2018 (table 3) 2019. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//statistics/drug-related-deaths/2018/drug-related-deaths-18-pub.pdf https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files//statistics/drug-related-deaths/2018/drug-related-deaths-sub1-18.xlsx.

- 50.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD) National drug and alcohol treatment waiting times 1 October–31 December 2019. 2020. Available from: https://beta.isdscotland.org/media/4144/2020-03-31-dawt-report.pdf.

- 51.SG. Scottish Government (SG) A wait off our shoulders: a guide to improving access to recovery-focused drug and alcohol treatment services in Scotland. 2010. Available from: http://www.dldocs.stir.ac.uk/documents/0099592.pdf.

- 52.Anonymous. Anonymous's blog Take-home naloxone in England. 2017. Available from: https://www.release.org.uk/naloxone.

- 53.NFP. National Focal Point (NFP) United Kingdom drug situation 2017. 2017. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/713101/Focal_Point_Annual_Report.pdf https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/713104/UK-drug-situation-2017-data-tables.xlsx.

- 54.ISD. Information Services Division (ISD), NHS National Services Scotland . The national drug-related deaths database (Scotland) report. Analysis of deaths occurring in 2015 and 2016. Edinburgh: National Services Scotland; 2018. Available from: https://beta.isdscotland.org/media/1500/2018-06-12-ndrdd-report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, Glanz J, Long J, Booth RE, et al. Return to drug use and overdose after release from prison: a qualitative study of risk and protective factors. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7((1)):3. doi: 10.1186/1940-0640-7-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison: a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356((2)):157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Brady JE, Giglio R, Keyes KM, DiMaggio C, Li G. Risk markers for fatal and non-fatal prescription drug overdose: a meta-analysis. Inj Epidemiol. 2017;4((1)):24. doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0118-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105((9)):1545–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Borschmann R, Tibble H, Spittal MJ, Preen D, Pirkis J, Larney S, et al. The mortality after release from incarceration consortium (MARIC): protocol for a multi-national, individual participant data meta-analysis. Int J Popul Data Sci. 2020;5((1)):1145–54. doi: 10.23889/ijpds.v5i1.1145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Binswanger IA, Nguyen AP, Morenoff JD, Xu S, Harding DJ. The association of criminal justice supervision setting with overdose mortality: a longitudinal cohort study. Addiction. 2020;115((12)):2329–38. doi: 10.1111/add.15077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Farrell M, Marsden J. Acute risk of drug-related death among newly released prisoners in England and Wales. Addiction. 2008;103((2)):251–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zlodre J, Fazel S. All-cause and external mortality in released prisoners: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2012;102((12)):e67–75. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.SPS. Scottish Prison Service (SPS) Scottish prison service addiction prevalence testing statistics (2016/17). Criminal justice social work statistics. Tables for drug treatment and testing orders orders by local authority areas, 2004–05 to 2018–19. 2018. Available from: https://www.scotpho.org.uk/behaviour/drugs/data/socialharm/ https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2020/02/criminal-justice-social-work-statistics-scotland-2018-19/documents/cjsw-la-file-drug-treatment-testing-orders-tables/cjsw-la-file-drug-treatment-testing-orders-tables/govscot%3Adocument/cjsw-la-file-drug-treatment-testing-orders-tables.xlsx.

- 64.PHE. Public Health England (PHE) An evidence review of the outcomes that can be expected of drug misuse treatment in England. 2017. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/586111/PHE_Evidence_review_of_drug_treatment_outcomes.pdf.

- 65.SPS. Scottish Prison Service (SPS) Prisoner survey 2017. 2018. Available from: http://www.sps.gov.uk/Corporate/Publications/Publication-6101.aspx.

- 66.Singleton N, Meltzer H, Gatward R, Coid J, Deasyl D. ONS Survey of the psychiatric morbidity of prisoners. 1998. Available from: http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsStatistics/DH_4007132.

- 67.Sparrow N. Health care in secure environments. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56((530)):724–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bebbington P, Jakobowitz S, McKenzie N, Killaspy H, Iveson R, Duffield G, et al. Assessing needs for psychiatric treatment in prisoners: 1. Prevalence of disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2017;52((2)):221–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-016-1311-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Light M, Grant E, Hopkins K. Ministry of justice analytical services. Gender differences in substance misuse and mental health amongst prisoners. Results from the surveying prisoner crime reduction (SPCR) longitudinal cohort study of prisoners. 2013. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/220060/gender-substance-misuse-mental-health-prisoners.pdf.

- 70.Tayside. Tayside Drug Death Review Group Drug deaths in Tayside, Scotland 2018 annual report. 2019. Available from: https://www.nhstaysidecdn.scot.nhs.uk/NHSTaysideWeb/idcplg?IdcService=GET_SECURE_FILE&Rendition=web&RevisionSelectionMethod=LatestReleased&noSaveAs=1&dDocName=prod_322007.

- 71.Lloyd C, Catney G, Williamson P, Bearman N, Norman P. Deprivation change in Britain (PopChange briefing 2) Centre for Spatial Demographics Research, University of Liverpool; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 72.CGCPH. Glasgow Centre for Population Health (GCPH) Accounting for Scotland's excess mortality: towards a synthesis. 2011. Available from: https://www.gcph.co.uk/assets/0000/1080/GLA147851_Hypothesis_Report__2_.pdf.

- 73.NRS. National Records of Scotland (NRS) Homeless deaths 2017 and 2018. 2020. Available from: https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/files/statistics/homeless-deaths/17-18/homeless-deaths-17-and-18-publication.pdf.

- 74.Scotland NH. The Scottish Burden of Disease Study, 2016. Deprivation report. 2016. Available from: https://www.scotpho.org.uk/media/1656/sbod2016-deprivation-report-aug18.pdf.

- 75.Farrell M, Hall W. Heroin-assisted treatment: has a controversial treatment come of age? Br J Psychiat. 2015;207((1)):3–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.114.160986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tweed EJ, Rodgers M, Priyadarshi S, Crighton E. Taking away the chaos: a health needs assessment for people who inject drugs in public places in Glasgow, Scotland. BMC Public Health. 2018;18((1)):829. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5718-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data