Abstract

Objective:

The objective of the study is to determine the oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices among the health-care workers (HCWs).

Materials and Methods:

The present questionnaire-based survey among 473 HCW comprising of doctors, nurses, pharmacists, technicians, and interns was carried out to know the oral health knowledge, attitude, and practices among different HCW. Responses were recorded and data were assessed through descriptive statistics and by applying analysis of variance, Chi-square, and z-tests.

Results:

Maximum of doctors (98.7%), nurses (80.4%), interns (73.3%), pharmacists (70.8%), and technicians (67.1%) responded correctly that oral health is related to systemic health followed by treating a decayed tooth is equally important as treating other body ailments. Doctors revealed higher mean knowledge scores in comparison with other HCW. A significant difference is noted with regard to frequency of dental visit (P = 0.000), reason behind dental visit (P = 0.001), and barrier for not visiting the dentist (P = 0.013) among males and females. Similarly, a significant difference is noted with regard to frequency of dental visit (P = 0.001), dentist familiarizing about the treatment (P = 0.001), and his concern about the patients (P = 0.001) among between different HCW.

Conclusion:

From the results of the present study, a variation in oral health knowledge was observed among different HCW. All the participants showed a positive attitude toward professional dental care.

KEYWORDS: Attitude, health-care workers, knowledge, oral health, practices

INTRODUCTION

The term oral health not only means a healthy dentition but it also signifies a healthy oral cavity.[1] Various orofacial disorders are known to have significant influence over systemic health of an individual, conversely, numerous systemic diseases are known to manifest in the oral cavity.[2] Hence, the importance of maintaining the optimal oral health care is to be understood by the entire health-care workers (HCW), as it needs a multidisciplinary approach.

In the previous two decades, dental caries and periodontal diseases which share a common risk factors with other chronic disorders pose a major health burden among the population of most of the developing nations.[3] Involvement and integration of HCW other than dental practitioners in promoting oral health are necessary for developing comprehensive health promotion and practices.[4]

Various HCWs such as general physicians, surgeons, and nurses are exposed to a wide range of population at various geographical locations, including poor, vulnerable, underprivileged, and uneducated and people belonging to various ethnic and cultural backgrounds. It is important to train the HCW about the significance of maintaining oral health which in turn helps them to recognize if there is any need regarding providing of health-care services and to develop preventive strategies among any particular population groups.[5]

In the various developing nations like India, an increased prevalence of numerous diseases affecting the oral cavity has been reported. This could be due to unawareness, negligence, limited resources, uneducated population, poverty, etc. The populations at large in developing countries do not prioritize maintaining the oral health as compared to systemic health. HCW belonging to different specialties deals with numerous patients every day, than that of dental practitioners.[6] With this background, we carried out the present study to evaluate the oral health-related knowledge, attitude, and practices among HCW.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study was carried out after obtaining clearance from institutional ethical committee. A convenience sampling technique was used to evaluate the knowledge regarding oral health, attitude, and practices of HCW. Doctors who were qualified medicine graduates and postgraduates and other allied subjects such as homeopathy and Ayurveda and interns, nurses, pharmacists, and technicians participated in this study. A pretested and structured questionnaire was and distributed among 490 HCW of which, responses were received from 473 individuals.

The questionnaire comprised of four components. The first component was related to information related to demographics such as age, sex, educational status, and profession. The second comprised of questions regarding knowledge of dental and periodontal health and related factors. The third component comprised of questions pertaining to the attitude of the dental professionals such as frequency, need, reason, and barriers for visiting the dentist. The questions of last component were related to oral hygiene practices.

The questionnaire was prepared in English for ensuring comprehension by all HCWs and pretested in a pilot study conducted in 20 HCW, and modifications were made accordingly. The validation was carried out in a panel expert and among 10 experts in the participants. Test-retest analysis showed a good reliability, Cronbach's alpha (α =0.83), of the questionnaire.

Analysis of the data was done using IBM SPSS Statistics 21. Data were assessed through descriptive statistics and by applying analysis of variance, Chi-square, and z-tests. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

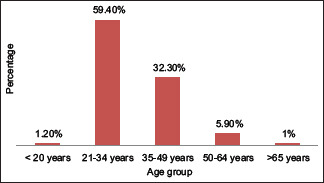

Table 1 shows the distribution of participants according to gender; maximum number (63.8%) of participants were males as compared with females (36.2%). Most of the participants (59.4%) were belonging to the age group of 21–34 years, followed by those in the age group of 35–49 years (32.3%) [Graph 1].

Table 1.

Gender-wise distribution of the participants

| Gender | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Male | 302 (63.8) |

| Female | 171 (36.2) |

| Total | 473 (100) |

Graph 1.

Distribution of the participants according to age group

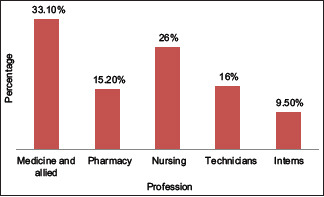

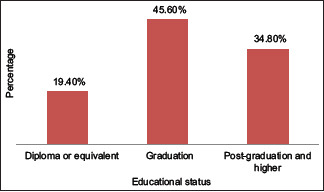

Distribution of the participants according to the profession is shown in Graph 2. Majority of the participants who responded were belonging to medicine and allied profession (33.1%), followed by nursing (26%). Most of the respondents studied till graduation (45.6%), 34.8% studied postgraduation and higher courses and 19.4% studied diploma or equivalent level [Graph 3].

Graph 2.

Distribution of the participants according to the profession

Graph 3.

Distribution of the participants according to education

Maximum of doctors (98.7%), nurses (80.4%), interns (73.3%), pharmacists (70.8%), and technicians (67.1%) responded correctly that oral health is related to systemic health followed by treating a decayed tooth is equally important as treating other body ailments [Table 2]. Doctors revealed higher mean knowledge scores when compared with other HCW. A statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) was observed when oral health knowledge scores were compared between different HCW [Table 3].

Table 2.

Knowledge level of various study participants

| Knowledge | Profession | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Medicine and allied doctors, n (%) | Pharmacy, n (%) | Nursing, n (%) | Technicians, n (%) | Interns, n (%) | |

| Bleeding gums represents gingivitis | 130 (82.8) | 41 (56.9) | 81 (65.8) | 36 (47.3) | 29 (64.4) |

| Regular brushing and flossing prevents gingivitis | 122 (77.7) | 28 (38.8) | 84 (68.2) | 25 (32.8) | 28 (62.2) |

| Dental plaque is a film deposited on teeth surface | 106 (67.5) | 21 (29.1) | 73 (59.3) | 17 (22.3) | 25 (55.5) |

| Plaque accumulation leads to gingivitis | 99 (63.0) | 19 (26.3) | 66 (53.6) | 15 (19.7) | 22 (48.8) |

| Sweets cause caries | 157 (100) | 72 (100) | 123 (100) | 76 (100) | 45 (100) |

| Plaque accumulation leads to caries | 94 (59.8) | 22 (30.5) | 61 (49.5) | 20 (26.3) | 21 (46.6) |

| Oral health is related to systemic health | 155 (98.7) | 55 (70.8) | 99 (80.4) | 51 (67.1) | 33 (73.3) |

| Treating a decayed teeth is equally important as other body ailments | 152 (96.8) | 47 (65.2) | 108 (87.8) | 42 (55.2) | 37 (82.2) |

| Caries influences the look of a person | 138 (87.8) | 49 (68.0) | 91 (73.9) | 44 (57.8) | 32 (71.1) |

| Carbonated beverages have ill effects dental health | 148 (94.2) | 51 (70.0) | 110 (89.4) | 46 (60.5) | 38 (84.4) |

Table 3.

Comparison of oral health knowledge in the different study groups

| Knowledge score | Characteristic | Mean±SD | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 6.143±1.134 | 2.961 | 0.086 (nonsignificant) |

| Female | 6.864±1.294 | |||

| Total | 6.452±1.266 | |||

| Profession | Medicine and allied | 6.865±1.451 | 4.187 | 0.021 (significant) |

| Pharmacy | 5.976±1.226 | |||

| Nursing | 6.126±1.276 | |||

| Technicians | 5.877±1.385 | |||

| Interns | 5.989±1.245 | |||

| Total | 6.351±1.268 | |||

| Educational status | Diploma or equivalent | 6.285±1.397 | 0.039 | 0.754 (nonsignificant) |

| Graduation | 6.354±1.239 | |||

| Postgraduation and higher | 6.782±1.378 | |||

| Total | 6.413±1.276 |

SD: Standard deviation

A significant difference was noted with regard to frequency of dental visit (P = 0.000), reason behind dental visit (P = 0.001), and barrier for not visiting the dentist (P = 0.013) among males and females. Similarly, a significant difference was noted with regard to frequency of dental visit (P = 0.001), dentist familiarizing about the treatment (P = 0.001), and his concern about the patients (P = 0.001) among between different HCW [Table 4].

Table 4.

Pearson Chi-square tests for attitude toward professional dental care

| Gender | Educational status | Profession | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency of visit to dentist | |||

| χ2 | 26.18 | 0.396 | 31.18 |

| df | 3 | 2 | 6 |

| P | 0.001* | 0.675 | 0.001* |

| Importance of regular visit to dentist | |||

| χ2 | 0.81 | 0.816 | 5.92 |

| df | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| P | 0.41 | 0.297 | 0.25 |

| Treatment procured during last visit to dentist | |||

| χ2 | 21.617 | 3.128 | 42.12 |

| df | 5 | 8 | 19 |

| Significance | 0.011* | 0.741 | 0.09 |

| Driving factor for last visit | |||

| χ2 | 9.168 | 6.912 | 7.12 |

| df | 4 | 3 | 14 |

| P | 0.027* | 0.19 | 0.61 |

| Barriers for avoiding to visit dentist | |||

| χ2 | 12.89 | 14.22 | 28.32 |

| df | 6 | 9 | 29 |

| P | 0.021* | 0.26 | 0.28 |

| Dentist make familiar about the treatment protocol | |||

| χ2 | 4.56 | 3.97 | 17.82 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| P | 0.35 | 0.629 | 0.001* |

| Dentist concerned about patient | |||

| χ2 | 11.89 | 3.947 | 31.35 |

| df | 3 | 2 | 7 |

| P | 0.39 | 0.481 | 0.001* |

| Dentist focus on treating but not preventive issue | |||

| χ2 | 0.48 | 1.99 | 7.45 |

| df | 2 | 2 | 6 |

| P | 0.71 | 0.36 | 0.23 |

*Significant. df: Degrees of freedom

Majority of HCW replied that they used toothbrush and toothpaste for cleaning their teeth. Nearly half of the HCW were using mouth wash and dental floss. Females and those with higher qualification showed an increased tendency for using the dental floss and mouth wash (P < 0.05). Almost all of the HCW brushed their teeth once for more than 2 min once in the morning hours. The difference between the frequency and duration of brushing among gender, educational status, and profession was statistically nonsignificant (P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

Diseases of the oral cavity are an essential health issue of the most of the population since it not just influence the systemic health of an individual but also affects the quality of the life negatively.[7] For the prevention of various oral diseases, routine oral hygiene practices are crucial for maintaining the mouth healthy. Even though the prevalence of oral diseases is an issue of concern throughout the world, most of the oral diseases can be prevented or treatable. Hence, the perception of the awareness, knowledge, attitude, and practices with regard to maintaining the oral health is imperative.[3]

HCW, such as general physicians, surgeons, nurses, frequently deals with a large people of the society. They are responsible for closely monitoring the various health issues and disease pattern among the population. HCW plays a significant role in the optimal functioning and stabilizing the health-care system in various parts of the country. They are also responsible for assisting and providing the possible health provisions to the people belonging to various sectors.[8]

In this study, a variation with regard to knowledge level among different HCW was observed, with lesser number of the participants possessing correct knowledge of plaque, and plaque can cause gingival and periodontal diseases. About 50%–70% of HCW had exact knowledge that gingival bleeding indicates gingivitis, and effect of caries on look of an individual and plaque can cause decaying of teeth. Oral health knowledge was found to be higher among HCW in certain domains, with more than 80% of them having correct knowledge of effect of consumption of sweets on teeth, carbonated beverages on dental health, also the significance of treating a carious tooth.

The knowledge that gingivitis is represented by bleeding gums was known to more female members than men, in contrast to this, the knowledge of preventing of gingivitis by regular brushing of teeth and use of floss was known to more male participants than females. The knowledge of plaque in causing decay of tooth than gingival diseases was more among females. Overall female respondent's revealed an increased oral health knowledge in comparison to their male counterparts, but this difference was statistically nonsignificant. This observation was in accordance with the findings of Baseer et al.[9] and Khami et al.,[10] who did not observe gender differences with regard to knowledge in studies carried out in Saudi Arabia and Iran, respectively. In contrast to this, some studies in the literature noted that females having a significantly higher knowledge about oral health in comparison with men and this difference was statistically significant.[11,12,13,14]

Among the all HCW, doctors responded maximum number of questions precisely, followed by nurses, interns, pharmacists, and technicians. The more likely explanation for this difference could be difference in the study curriculum and the fact that examination of mouth is a routine protocol for doctors and nurses, postings in the dental departments and the information obtained through continuing education programs.

Responses regarding the necessity of regular dental visit in our study were similar to that of, Baseer et al.,[9] Timmerman et al.,[15] and Sharda and Shetty.[16] In this study, tooth pain was the chief driving factor for visiting the dentist and this finding was similar to the observations of Baseer et al.,[9] Al-Omari and Hamasha,[13] Sharda and Shetty,[16] and Doshi et al.[17] Oral hygiene practices among the participants of the present study were similar to that of Baseer et al.[18]

It is necessary for this HCW to possess a thorough understanding about the significance of maintaining the oral health, so that they can guide and motivate the individuals in carrying out optimal oral health practices, thereby preventing various diseases affecting the oral cavity. There is a need for enhancing the knowledge of HCW so that it can have a positive impact on oral health attitude and practices. It is recommended to carry out various awareness activities like continuing medical/dental education programs among this HCW.

The limitations of this study are its cross-sectional design and the limited sample size. The data of the current study completely rely on self-reported data; the results may be biased because of over and under-reporting.

CONCLUSION

From the observations of this study, variations in oral health knowledge were observed among different HCW. All the participants revealed a positive attitude toward professional dental care. Adequate knowledge regarding the oral health should be provided to all the HCWs so as to enhance their awareness, knowledge, and practices. Significance of the oral health should be incorporated in the course curriculum of the HCW.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baiju RM, Peter E, Varghese NO, Sivaram R. Oral health and quality of life: Current concepts. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:E21–6. doi: 10.7860/JCDR/2017/25866.10110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babu NC, Gomes AJ. Systemic manifestations of oral diseases. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2011;15:144–7. doi: 10.4103/0973-029X.84477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griffin SO, Jones JA, Brunson D, Griffin PM, Bailey WD. Burden of oral disease among older adults and implications for public health priorities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102:411–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fotedar S, Fotedar V, Bhardwaj V, Thakur AS, Vashisth S, Thakur P. Oral health knowledge and practices among primary healthcare workers in Shimla District, Himachal Pradesh, India. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:858–61. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_276_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaur S, Kaur B, Ahluwalia SS. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices amongst health professionals in Ludhiana, India. Dentistry. 2015;7:315. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aggnur M, Garg S, Veeresha K, Gambhir R. Oral health status, treatment needs and knowledge, attitude and practice of health care workers of Ambala, India - A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2014;4:676–81. doi: 10.4103/2141-9248.141496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Palma PV, Caetano PL, Leite IC. Impact of periodontal diseases on health-related quality of life of users of the brazilian unified health system. Int J Dent. 2013;2013:150357. doi: 10.1155/2013/150357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Babiker A, El Husseini M, Al Nemri A, Al Frayh A, Al Juryyan N, Faki MO, et al. Health care professional development: Working as a team to improve patient care. Sudan J Paediatr. 2014;14:9–16. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baseer MA, Alenazy MS, Alasqah M, Algabbani M, Mehkari A. Oral health knowledge, attitude and practices among health professionals in King Fahad Medical City, Riyadh. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2012;9:386–92. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khami MR, Virtanen JI, Jafarian M, Murtomaa H. Prevention-oriented practice of Iranian senior dental students. Eur J Dent Educ. 2007;11:48–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0579.2007.00436.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pellizer C, Pejda S, Spalj S, Plancak D. Unrealistic optimism and demographic influence on oral health-related behavior and perception in adolescents in Croatia. Acta Stomatol Croat. 2007;41:205–15. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostberg AL, Halling A, Lindblad U. Gender differences in knowledge, attitude, behavior and perceived oral health among adolescents. Acta Odontol Scand. 1999;57:231–6. doi: 10.1080/000163599428832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Al-Omari QD, Hamasha AA. Gender-specific oral health attitudes and behavior among dental students in Jordan. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2005;6:107–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukai K, Takaesu Y, Maki Y. Gender differences in oral health behavior and general health habits in an adult population. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 1999;40:187–93. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.40.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Timmerman EM, Hoogstraten J, Meijer K, Nauta M, Eijkman MA. On the assessment of dental health care attitudes in 1986 and 1995, using the dental attitude questionnaire. Community Dent Health. 1997;14:161–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sharda AJ, Shetty S. A comparative study of oral health knowledge, attitude and behaviour of non-medical, para-medical and medical students in Udaipur city, Rajasthan, India. Int J Dent Hyg. 2010;8:101–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2009.00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doshi D, Baldava P, Anup N, Sequeira PS. A comparative evaluation of self-reported oral hygiene practices among medical and engineering university students with access to health-promotive dental care. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2007;8:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baseer MA, Mehkari MA, Al-Marek FA, Bajahzar OA. Oral health knowledge, attitude, and self-care practices among pharmacists in Riyadh, Riyadh Province, Saudi Arabia. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6:134–41. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.178739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]