Abstract

Introduction:

Objective: To assess the antioxidant property of 10% amla extract in reversing the compromised bond strength and to assess the antioxidant property of 10% amla extract and Elsenz on the color stability of power bleached teeth.

Materials and Methods:

Ninty extracted single-rooted maxillary anterior were collected and divided as follows: The labial surfaces of 30 samples were subjected to power bleaching after which the samples were divided into three groups– Group I (control), Group II (antioxidant amla), and Group III (Elsenz) with n = 10 in each which were then stained with a coffee solution for 10 mins. The color difference was recorded with a colorimeter at baseline, after bleaching, after 7, and after 15 days of staining. sixty specimens were randomly divided into six groups (n = 10) as following: Group I (immediate bonding); Group II (bleaching + immediate bonding); Group III (bleaching + antioxidant and immediate bonding); Group IV (bleaching + 1 week storage + antioxidant + bonding); Group V (bleaching + 2 week storage + antioxidant + bonding); Group VI (bleaching + 2 week storage + bonding). All the specimens were tested for shear bond strength in universal testing machine. Statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA and Scheffe's post hoc test.

Results:

Significantly higher staining was observed in Group II (amla) and least with Elsenz paste

The highest mean shear bond strength was found in Group I followed by Group V.

Conclusion:

Elsenz showed the least staining followed by artificial saliva. 10% Amla extract neither was effective in preventing staining of power bleached enamel nor in restoring the poor bond strength of power bleached enamel.

KEYWORDS: Amla, antioxidant, color stability, Elsenz, remineralization, shear bond strength

INTRODUCTION

Tooth bleaching an approach to tooth discoloration has become one of the most commonly practiced esthetic dental treatments, which is rather conservative and cost-effective for improving a person's smile.[1] Hydrogen peroxide (HP) and carbamide peroxide have been used successfully to attain lighter and more desirable tooth colors.[2]

Impediments of bleaching may range from postoperative sensitivity, pulpal irritation to declined or reduced bond strength of composite resin to enamel.[3] Various researches have concluded that the shear bond strength of tooth-colored resin-based materials to the tooth has found to be drastically decreased owing to the presence of residual oxygen layer. Increased chances of staining of the tooth during or just after the bleaching is reported if pigments of food and beverages are consumed during that period due to increased surface roughness.[4,5,6] Hence, the two major concerns that are considered in this study are the compromised bond strength and re-staining of bleached teeth.

Many remineralizing agents have been studied for color stability of bleached enamel in vitro and in vivo. Recently a fluoride-containing bioactive glass (ELSENZ) was introduced which releases Ca2+, PO43− and F-ions to construct fluorapatite minerals to revamp, strengthen, and shield tooth structure and has been reported as a potent remineralizing agent for enamel.[5,7,8] Its effect on the color stability of bleached enamel is not evaluated yet.

Discussing the declined bond strength, oxygen ions are formed as an end product of the bleaching reaction which could be a possible reason for interfering with the resin polymerization.

Previously conducted a significant amount of studies have shown that herbal antioxidants have shown good results in reversal of bonding to bleached enamel. Nutraceutical agents such as pine bark extract, GSE–grape seed extract, lemon peel, cranberry, lycopene, green tea, white tea as well as the leaves of the hazel tree, and many more have proven to show potent antioxidant activity.[9]

Recently Emblica Officinalis/Indian gooseberry (amla from Sanskrit-Amalika) has been introduced in dentistry. It is already known for its therapeutic effect which possesses hepatoprotective and antioxidant properties for systemic uses. Efficacy of antioxidant proeperty of amla on bleached enamel is still unreported appropriately in the litertature.[10,11] Hence the aim of this research was to evaluate the effect of antioxidant property of amla on the compromised bond strength and efficacy of ELSENZ and amla on re-staining of power bleached teeth.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation of extract

50 gms of Amla powder was accurately weighed in a weighing balance machine (Uni Bloc, Shimadzu) and transferred to a conical flask containing 450 ml distilled water. Then 50 ml of ethanol was added to the above solution to prevent any microbial growth. This solution was then subjected for an extraction procedure known as maceration for 3 days with occasional shaking using orbital shaker. After 3 days 10% concentration of the extract was obtained by filtering under vacuum using Whitman filter paper.

Sample preparation

90 permanent single-rooted maxillary anterior teeth of approximately the same size which were extracted for periodontal and orthodontic rationale were collected for this study. The study protocol was approved by the institutional ethical committee.

Inclusion criteria

Caries free teeth

Non fractured or crack free teeth.

Exclusion criteria

Hypoplastic teeth

Fractured, cracked, or dried teeth

Teeth with developmental defects

Teeth with restoration.

All the teeth were cleansed of debris and soft tissue with a hand scaler followed by rubber cup and pumice slurry with a micro-motor handpiece under slow speed (NSK Nakanishi Inc, Tochigi, Japan). Then, they were kept in a solution of distilled water and 0.1% thymol (antiseptic solution) (NICE Chemical Laboratory Supplies Limited, India) until further use.

Procedure and grouping

As the study includes measurement of two parameters the samples were divided as follows:

For assessment of color stability

Specimen preparation

30 teeth were decoronated 2 mm below the cementoenamel junction (CEJ) using a double-sided diamond disc (NTI® Diamond Discs, Axis-sybronendo. Kerr corporation CA. USA) and a slow speed straight handpiece (NSK Nakanishi Inc, Tochigi, Japan). Each specimen with the labial surface exposed was immersed separately in rectangular molds made by using cold cure acrylic resin

-

These specimens were examined by the colorimeter (Konica Minolta) at the following stages:

Before bleaching

After 1st bleaching session

After 7 days of staining

After 15 days of staining.

Colour evaluation

-

The color evaluation was done by the L*a*b* color scale

ΔE >3.7-easily visible difference

ΔE between 3.7 and 1 acceptable difference

ΔE <1-difference clinically not visible.

The hunter L*a*b* color space (also referred to as CIELAB), one of the most popular color spaces for measuring object color was used using a spectrophotometer (CM 3500D, MINOLTA Co Ltd, JAPAN.)

The complete change in color (dE*) was determined using the following formula: “ΔE * = [(ΔL*) 2 (Δa*) 2 (Δb*) 2 ]1/2”.

where dL*, da*, and db * shows the variation in L*, a*, and b * values, respectively.[4]

ΔL7S = L2-L1 Δa7S = a2-a1 Δb7S = b2-b1 (ΔE7S)

ΔL15S = L3-L1 Δa15S = a3-a1 Δb15S = b3-b1 (ΔE15S)

L * 1, a * 1, b * 1 = Coordinates of the specimens after HP bleaching

L * 2, a * 2, b * 2 = Coordinates of the specimens after 7 days of coffee staining

L * 3, a * 3, b * 3 = Coordinates of the specimens after 15 days of coffee staining.

Bleaching procedure

The labial surfaces of all the samples were subjected to 30% HP bleaching solution (NICE Chemical Laboratory Supplies Limited, India) and activated with LED module (bluedent 12bl bleaching system, 430–490 nm) placed perpendicular to the labial surface for 3 min. Three repeated application of this cycle of bleaching and light activation with a resting time of 10 min was done on the same day followed by washing with distilled water

After bleaching the samples were divided into three groups– Group I (subjected to artificial saliva/control), Group II (subjected to antioxidant amla) and Group III (subjected to remineralizing agent Elsenz) with n = 10 in each.

Surface treatments

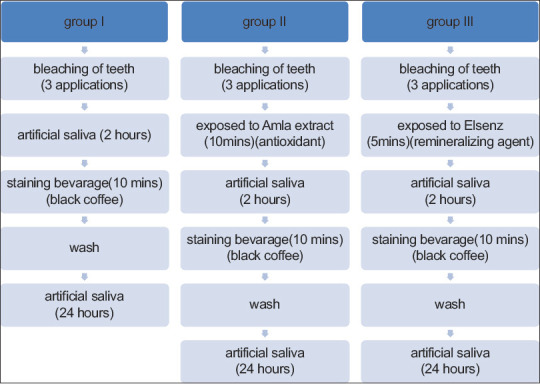

Subsequent to bleaching the samples were immersed in the following manner as shown in Figure 1

This procedure was done every day for 2 weeks. During the entire experimental period, the artificial saliva was prepared and changed every day

The staining solution was prepared by mixing 200 ml of boiling water in 5 g of instant coffee (Nescafe Sunrise). Specimens were stained by immersion into the fresh coffee solution prepared every time. Specimens were immersed in small containers having 30 ml of freshly prepared coffee solution for immersion period (10 min/day), for 15 successive days. The specimens were cleaned with distilled water and stored in artificial saliva for the rest of the day[12]

Randomly selected one representative specimen from each group along with one baseline (no treatment) and one only bleached specimen were examined under the scanning electron microscope (SEM), to assess morphological changes at baseline, after bleaching process, and after surface treatments at magnification ×2000.[13]

Figure 1.

Procedure of surface treatment and staining

For assessment of bond strength: 60 specimens were taken for which the roots were immersed in cold-cure acrylic resin block till CEJ so that only the coronal portion was exposed. Then the Labial surfaces were flattened with 600-grit silicon carbide paper.

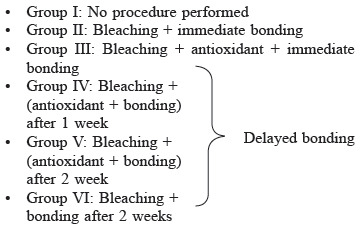

• The prepared samples were divided into six groups with n = 10 each

• Except Group I the labial surfaces of all the prepared samples were bleached as mentioned above. After bleaching Group II was subjected to bonding immediately. Group III samples were subjected to application of 10% amla extract for 10 min, and then washed with distilled water followed by immediate bonding

• After bleaching Group IV specimens were stored in artificial saliva at 37°C for 1 week and Group V and Group VI for 2 weeks. The artificial saliva was prepared fresh and replaced daily.[14]

• After 1 week Group IV and after 2 weeks Group V were treated like Group III. After 2 weeks Group VI was subjected to bonding

• For all the above groups, the following bonding protocol was done

• First, the samples were etched with 37% phosphoric acid (Anabond Eazetch Etchant Gel) for 15 s, washed for 20 s with distilled water followed by air drying gently for 5 s. Then the bonding agent (Ivoclar Tetric-N-Bond) was applied gently using an applicator tip and light-cured for 15 s. For standardization of area silicon putty mold of dimension 4 mm width, 5 mm length, and 3 mm height was firmly attached over the bonded enamel surface. The A3 shade flowable composite resin (Ivoclar Vivadent tetric-n-flow) was then placed inside the prepared mold and cured for 40 s with LED module (bluedent 12bl bleaching system, 430-490 nm) at zero distance. All the specimens were stored in distilled water at 37°C for 48 h before testing for shear bond strength.

Bond strength assessment

Each specimen was then loaded in the lower jig of the universal testing machine (Model No. UT-04-0050 BISS Ltd, Bangalore, India) for bond strength testing. A knife-edge shearing chisel was placed in the upper jig of the UTM machine with the cutting edge positioned on the composite resin-tooth interface. The long axis of the specimen was kept perpendicular to the applied forces. This setup was then subjected to a static loading at crosshead speed of 0.5 mm/min until fracture occurred and the data were recorded using computer software (Monotonic V5 static testing software). The values were obtained in kilo-Newtons which after calculation of shear bond strength were converted into megapascals (Mpa).

The shear bond strength was calculated by the formula

The ratio of Peak load at failure (kgf) to the cross-sectional area of the bonded surface area (mm2).

RESULTS

Evaluation and comparison of color stability (ΔE values) of power bleached enamel between control and experimental groups

One-way ANOVA revealed a nonsignificant mean difference between groups 1, 2, and 3 at baseline as well as after bleaching in their mean scores, indicating a similarity in the mean scores of groups 1, 2, and 3 both at baseline and after bleaching. Repeated measure ANOVA revealed a significant decrease (F = 1526.813; P = .001) in mean scores from baseline to bleaching with a decrease of 25.33 scores (30.04–4.71) irrespective of the groups. However, when the group-wise reduction was analyzed a nonsignificant F value was observed, indicating similarity in the decrease of mean scores from baseline to bleaching of all the three groups [Tables 2 and 3].

Table 2.

“Comparison of∆E values between bleaching and experimental groups”

| Sessions | Group | Mean±SD | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delt_E_bleaching | Group 1 | 4.37±2.47 | 0.802 | 0.459 |

| Group 2 | 4.28±2.06 | |||

| Group 3 | 5.49±2.58 | |||

| Total | 4.71±2.36 | |||

| Delt_E_day 7 | Group 1 | 7.73a±3.79 | 6.342 | 0.006 |

| Group 2 | 12.29b±1.55 | |||

| Group 3 | 7.54a±4.18 | |||

| Total | 9.19±3.95 | |||

| Delt_E_day 15 | Group 1 | 7.75a±4.74 | 16.859 | 0.000 |

| Group 2 | 15.84b±3.13 | |||

| Group 3 | 6.29a±3.85 | |||

| Total | 9.96±5.73 | |||

| Test statistics | F (overall) | 31.557 | 0.001 | |

| F (between group) | 10.380 | 0.001 | ||

SD: Standard deviation

Table 3.

“Master table showing mean and standard deviation between all the groups with superscripts”

| Groups | n | Mean (Mpa)±SD | F | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | 10 | 16.30c±1.61 | 45.282 | 0.001 |

| G2 | 10 | 8.41a±1.34 | ||

| G3 | 10 | 7.94a±1.63 | ||

| G4 | 10 | 7.76a±0.95 | ||

| G5 | 10 | 10.93b±2.40 | ||

| G6 | 10 | 8.78a,b±0.77 | ||

| Total | 60 | 10.02±3.36 |

Mean values with different superscripts are significantly different from each other as revealed by Scheffe’s post hoc test (alpha=0.05). SD: Standard deviation

Table 1.

“Comparison of∆E values between baseline and bleaching group”

| Sessions | Group | Mean±SD | Results of one-way ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| F | P | |||

| Delt_E_baseline | Group 1 | 30.43±2.89 | 0.123 | 0.885 |

| Group 2 | 29.60±3.92 | |||

| Group 3 | 30.10±4.34 | |||

| Total | 30.04±3.65 | |||

| Delt_E_bleaching | Group 1 | 4.37±2.47 | 0.802 | 0.459 |

| Group 2 | 4.28±2.06 | |||

| Group 3 | 5.49±2.58 | |||

| Total | 4.71±2.36 | |||

| Results of repeated measure ANOVA | F (overall) | 1526.813 | 0.001 | |

| F (between group) | 0.416 | 0.664 | ||

SD: Standard deviation

Evaluation and comparison of shear bond strength values between control and experimental groups

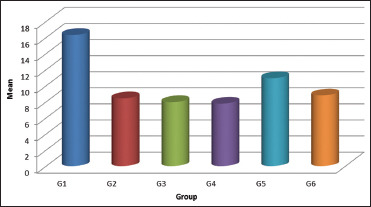

The mean Mpa values for groups G1, G2, G3, G4, G5, and G6 were 16.31, 8.41, 7.94, 7.75, 10.94, and 8.78, respectively. One-way ANOVA revealed a significant mean difference between mean Mpa values of six groups (F = 45.282; P = 0.001). Further Scheffe's post hoc test revealed that mean Mpa values of Group 2, 3, 4 were the least, and mean values of Group 1 were the highest and mean values of Group 5 and 6 in between. There is no significant mean difference between 2, 3, 4, and 6 as well as between Group 5 and 6 (alpha = 0.05) [Graph 1].

Graph 1.

Bar graph representing mean shear bond strength for all the groups

DISCUSSION

Aesthetics is an important dimension in dental practice aiming at patient satisfaction in terms of high self-esteem through the creation of a perfect appearance of one's smile. Bleaching is one such conservative approach to help achieve aesthetics by removal of discoloration (intrinsic or extrinsic stains) on the tooth surface.[15,16,17] Whitening or bleaching is often desired nowadays when teeth become yellowish over time for varied reasons.[18] In-office or power bleaching utilizes a range of higher concentrations of HP (15%–38%) applied directly on the tooth surface.[19] The mechanism involves an oxidizing process where organic chromogens responsible for discoloration are dissolved by breaking the strong double bond due to the reaction with free oxygen radicles released by HP.[20] Nascent oxygen enters the organic enamel-dentin matrix and reacts with the organic molecules thus dissociating the pigments by modifying and splitting the molecular chains converting them into smaller and light-colored molecules.[21]

The spectrophotometer is the highest reliable standard for color matching.[22,23,24] Spectrophotometer according to CIELAB system denotes color change which is popular and widely used and was introduced for determination of colors for clinical evaluation.[25] The color difference can be distinguished by the general population when value ΔE >3.7 and is contemplated to be clinically acceptable and perceivable, and hence it is applied in most of the color-related studies in dentistry.[26] In this study, all the specimens showed ΔEb values (color difference between baseline and bleached specimens) above 26.0. This indicates that 30% HP bleaching agent with light activation was successful.

In the present study, on evaluation of color stability, the results showed re-staining values was maximum with respect to Group 2 where the surface treatment was done by 10% amla for 10 min and least values were showed by Group 1 (elsenz) and 3 (artificial saliva). Though statistically no significant difference was seen between Group 1 and Group 3 (P > 0.05). The possible explanation for this could be the time duration taken in this study, i.e., 2 weeks. The results showed the difference from bleaching (ΔEb) day to after 15 days of staining, i.e., ΔE15S = 3.4 for group 1 and 0.8 for group 3. This indicates a clinically perceivable color difference in group 1 (ΔE between 1 and 3.7) as compared to group 3 where ΔE <1 i.e., clinically not acceptable or perceivable whereas there is no such difference between the groups after 7 days of staining. In similar studies, the difference between artificial saliva and a remineralizing agent on color stability could be noted at longer duration that is around 4 weeks.[27,28,29]

Elsenz is a known bioactive glass containing remineralizing agent. In an aqueous environment, bioactive glass begins surface reaction immediately in the following three phases: Leaching and exchange of cations, network dissolution of Silicon dioxide, and precipitation of Ca2+ and PO4 to form an apatite layer as quoted by many previously done studies.[30] This is supported by the above SEM findings where cluster-like deposition can be seen in abundance within a period of 15 days.

Artificial saliva mimics natural saliva for in vitro conditions and has abundance of Ca2+ and PO4 ions. This provides the optimal conditions for remineralization.[31,32] Amaechi et al. studied the effects of saliva and a remineralizing agent on eroded enamel micro-hardness and stated that natural saliva has the potential to remineralize enamel just like the remineralizing agents with fluoride.[33] In the present research, the most substantial color change was reported in the amla group. From the above SEM findings, it could be noted that there is the alteration of surface topography of enamel but comparatively lesser than that seen in group 3. This could be one of the possible explanations of more uptake of stain due to lesser remineralization. Furthermore, the acidic pH of 10% amla (3.38) found in this study could be a reason to create an environment less susceptible to remineralization resulting in more uptake of stain by the bleached enamel surface.[34]

Discussing the antioxidant property of amla in bond reversal, the present study results concluded 10% amla for 10 min is not sufficient to improve the shear bond strength of bleached enamel with composite resin when done immediately or even after a week. Shivani keni et al. used Indian gooseberry or amla as an antioxidant and reported an appreciable increase in bond strength as compared to the group that did not receive any antioxidant treatment preceding immediate bonding.[35]

The outcomes in this study are not consistent with this study. This difference might be explained by the differences in the procedure, such as concentration (bleaching agent used as well as the amla extract), duration of application which are known to affect bond formation results in antioxidant procedures.

In the present study, the results showed that group 1 (control, no bleaching) showed the highest mean bond strength (16.31 ± 1.61) when equated to the rest of the groups. Bond strength was seen to be least for groups 2 (8.4092 ± 1.33610), 3 (7.9434 ± 1.62608), 4 (7.7571 ± 0.94707), and 6 with no significant difference amongst the groups. This could be accredited to the presence of residual oxygen free radicals on the enamel surface. As per previously provided literature, this liberated oxygen interferes with the resin infiltration and results in polymerization inhibition of the resin cured via free radical mechanism.[36] A similar outcome supporting this data has been seen in this project.

It has been reported in previous studies that during treatment with HP, OH-ions in the apatite lattice are exchanged by peroxide ions (O22−), resulting in the formation of peroxide apatite. In 2 weeks repository period, the O22− ions start deteriorating and the OH-ions re-enter the apatite lattice, resulting in the eradication of the structural changes caused by the incorporation of the O22− ions.[16,37,38] Hence, delay in bonding by a period of 1–3 weeks following the bleaching procedure was recommended.[39] Hence, the present study included evaluation of samples after 1 week and 2 weeks also. In the present study, there was no reversal of bond seen after 1 week supporting the above theory and attributing to the failure of 10% amla as an antioxidant. However, there was a noteworthy difference between the shear bond strength seen after two weeks after the application of 10% amla antioxidant (group 5) (10.9344 ± 2.40013) in comparison to its counter group (group 6) (8.7819 ± 0.76747) and all the other experimental groups. This states that 10% amla applied for 10 min has the antioxidant property to improve the compromised bond strength but not potent enough to completely reverse the undesirable effects on bond strength seen immediately or after 1 week of application of 30% HP bleaching agent.

Further studies should be conducted evaluating higher concentrations of amla or with increased application time to evaluate its antioxidant property on bleached enamel. Furthermore, further studies are required to evaluate the type of extract most effective in leaching out the required components responsible for the desired property.

CONCLUSION

Under the limitations or constraints of this in vitro study, the following opinions were drawn through the obtained data:

Remineralizing agents have a significant effect on decreasing stain adsorption of freshly bleached enamel

Elsenz, a fluoride-containing bioactive glass-based remineralizing agent was found to have the greatest effect followed by artificial saliva on decreasing stain absorption with not much significant difference between them

10% Amla aqueous extract could not prevent coffee staining of power bleached enamel

Application of remineralizing agent after bleaching has high benefits

In vitro use of 30% HP in in-office power bleaching results in compromised bond strength

10% Amla aqueous extract as an antioxidant when applied for 10 min immediately after power bleaching could not reinstate the affected bond strength of composite resin.

Thus, from the present in vitro study, it can be concluded that 10% Amla (Emblica Officinalis) or Indian gooseberry extract solution was not effective in preventing the stain adsorption of coffee on power bleached enamel nor was it effective in restoring the poor bond strength of power bleached enamel.

Clinical relevance

Treatment with remineralizing agents after bleaching can be useful in clinical practice as they tend to reduce stain adsorption and restore the lost mineral content.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. Tooth Whitening/Bleaching: Treatment Considerations for dentists and Their Patients. American Dental Association; 2010. pp. 1–12. Retrieved from http://www.bamatis.com/docs/HOD_whitening_rpt.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Arumugam MT, Nesamani R, Kittappa K, Sanjeev K, Sekar M. Effect of various antioxidants on the shear bond strength of composite resin to bleached enamel: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17:22–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.124113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gökçe B, Cömlekoğlu ME, Ozpinar B, Türkün M, Kaya AD. Effect of antioxidant treatment on bond strength of a luting resin to bleached enamel. J Dent. 2008;36:780–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taneja S, Kumar M, Agarwal PM, Bhalla AS. Effect of potential remineralizing agent and antioxidants on color stability of bleached tooth exposed to different staining solutions. J Conserv Dent. 2018;21:378–82. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_354_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karadas M, Tahan E, Demirbuga S, Seven N. Influence of tea and cola on tooth color after two in-office bleaching applications. J Restor Dent. 2014;2:83–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun L, Liang S, Sa Y, Wang Z, Ma X, Jiang T, et al. Surface alteration of human tooth enamel subjected to acidic and neutral 30% hydrogen peroxide. J Dent. 2011;39:686–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkahtani R, Stone S, German M, Waterhouse P. A review on dental whitening. J Dent. 2020;100:103423. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sivaranjani S, Ahamed S, Bhavani, Rajaraman Comparative evaluation of remineralisation potential of three different dentifrices in artificially induced carious lesions: An in vitro study. Int J Curr Res. 2018;10:72306–11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferraz LN, Oliveira AL, Grigoletto M, Botta AC. Methods for reversing the bond strength to bleached enamel: A literature review. JSM Dent. 2018;6:1105. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhargava KY, Aggarwal S, Kumar T, Bhargava S. Comparative evaluation of the efficacy of 3 antioxidants vs NaOCl and EDTA; use for root canal irrigation in smear layer removal – SEM study. Int J Pharm Pharma Sci. 2015;7:366–71. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Khopde SM, Priyadarsini K Indira, Mohan H, Gawandi VB, Satav JG, Yakhmi JV, Banavaliker MM, Biyani MK, Mittal JP. Characterizing the antioxidant activity of amla extract. Journal of Current Science. 2001;81(2):185–190. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Celik C, Yuzugllu B, Erkut S, Yazici AR. Effect of bleaching on staining ability of resin composite restorative materials. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2009;21:407–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1708-8240.2009.00299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nagi SM, Hassan SN, Abd El-Alim SH, Elmissiry MM. Remineralization potential of grape seed extract hydrogels on bleached enamel compared to fluoride gel: An in vitro study. J Clin Exp Dent. 2019;11:e401–7. doi: 10.4317/jced.55556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prasada KL, Penta PK, Ramya KM. Spectrophotometric evaluation of white spot lesion treatment using novel resin infiltration material (ICON®) J Conserv Dent. 2018;21:531–5. doi: 10.4103/JCD.JCD_52_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai SC, Mak YF, Cheung GS, Osorio R, Toledano M, Carvalho RM, et al. Reversal of compromised bonding to oxidized etched dentin. J Dent Res. 2001;80:1919–24. doi: 10.1177/00220345010800101101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lai SC, Tay FR, Cheung GS, Mak YF, Carvalho RM, Wei SH, et al. Reversal of compromised bonding in bleached enamel. J Dent Res. 2002;81:477–81. doi: 10.1177/154405910208100709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Türkmen C, Güleryüz N, Atalı PY. Effect of sodium ascorbate and delayed treatment on the shear bond strength of composite resin to enamel following bleaching. Niger J Clin Pract. 2016;19:91–8. doi: 10.4103/1119-3077.164328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Joiner A, Luo W. Tooth colour and whiteness: A review. J Dent. 2017;67S:S3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He LB, Shao MY, Tan K, Xu X, Li JY. The effects of light on bleaching and tooth sensitivity during in-office vital bleaching: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dent. 2012;40:644–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carey CM. Tooth whitening: What we now know. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2014;14(Suppl):70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jebdp.2014.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Albers H. Lightening natural teeth. ADEPT Rep. 1991;2:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moghadam FV, Majidinia S, Chasteen J, Ghavamnasiri M. The degree of color change, rebound effect and sensitivity of bleached teeth associated with at-home and power bleaching techniques: A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Dent. 2013;7:405–11. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.120655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun A, Jepsen S, Krause F. Spectrophotometric and visual evaluation of vital tooth bleaching employing different carbamide peroxide concentrations. Dent Mater. 2007;23:165–9. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chu SJ, Trushkowsky RD, Paravina RD. Dental color matching instruments and systems. Review of clinical and research aspects. J Dent. 2010;38(Suppl 2):e2–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ruthunas V, Vaidotas Sabaliauskas V, Mizutani H. Effect of different food colors and polishing technique on color stability of provisional prosthetic material. J Dent Mater. 2010;29:167–76. doi: 10.4012/dmj.2009-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Reijden WA, Buijs MJ, Damen JJ, Veerman EC, ten Cate JM, Nieuw Amerongen AV. Influence of polymers for use in saliva substitutes on de- and remineralization of enamel in vitro. Caries Res. 1997;31(3):216–23. doi: 10.1159/000262403. doi: 10.1159/000262403. PMID: 9165194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen YH, Yang S, Hong DW, Attin T, Yu H. Short-term effects of stain-causing beverages on tooth bleaching: A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Dent. 2020;95:103318. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2020.103318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watts A, Addy M. Tooth discoloration and staining: A review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2001;190:309–16. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Côrtes G, Pini NP, Lima DA, Liporoni PC, Munin E, Ambrosano GM, et al. Influence of coffee and red wine on tooth color during and after bleaching. Acta Odontol Scand. 2013;71:1475–80. doi: 10.3109/00016357.2013.771404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lynch RJ, Mony U, ten Cate JM. Effect of lesion characteristics and mineralizing solution type on enamel remineralization in vitro. Caries Res. 2007;41:257–62. doi: 10.1159/000101914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shadman N, Ebrahimi SF, Shoul MA, Sattari H. In vitro evaluation of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate effect on the shear bond strength of dental adhesives to enamel. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2015;12:167–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heymann HO, Swift E, Jr, Ritter AV. 6th ed. Canada: Elsevier; 2012. Sturdevant's Art and Science of Operative Dentistry; pp. 51–4. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Amaechi BT, Higham SM. In vitro remineralisation of eroded enamel lesions by saliva. J Dent. 2001;29:371–6. doi: 10.1016/s0300-5712(01)00026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azer SS, Hague AL, Johnston WM. Effect of pH on tooth discoloration from food colorant in vitro. J Dent. 2010;38(Suppl 2):e106–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keni S, Nambiar S, Philip P, Shetty S. A comparison of the effect of application of sodium ascorbate and amla (Indian gooseberry) extract on the bond strength of brackets bonded to bleached human enamel: An In vitro study. Indian J Dent Res. 2018;29:663–6. doi: 10.4103/ijdr.IJDR_720_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kaya AD, Türkün M. Reversal of dentin bonding to bleached teeth. Oper Dent. 2003;28:825–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vidhya S, Srinivasulu S, Sujatha M, Mahalaxmi S. Effect of grape seed extract on the bond strength of bleached enamel. Oper Dent. 2011;36:433–8. doi: 10.2341/10-228-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bittencourt ME, Trentin MS, Linden MS, de Oliveira Lima Arsati YB, França FM, Flório FM, et al. Influence of in situ post bleaching times on shear bond strength of resin based composite restoration. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;41:300–6. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thapa A, Vivekananda PA, Thomas MS. Evaluation and comparison of bond strength to 10% carbamide peroxide bleached enamel following the application of 10% and 25% sodium ascorbate and alfa tocopherol solution: An in vitro study. J Conserv Dent. 2013;16:111–5. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.108184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]