Abstract

Objective:

Early experiences of having received maternal warmth predict responses to opportunities to connect with others later in life. However, understanding of neurochemical mechanisms by which such relationships emerge remain incomplete. Endogenous opioids, involved in social connection in both animals and humans, may contribute to this link. Therefore, the current study examined (1) relationships between early maternal warmth and brain and self-report responses to novel social targets (i.e., outcomes that may promote social connection) and (2) the effect of the opioid antagonist, naltrexone, on such relationships.

Methods:

Eighty-two adult participants completed a retrospective report of early maternal warmth. On a second visit, participants were randomized to 50mg of oral naltrexone (n=42) or placebo (n=40) followed by an MRI scan where functional brain activity in response to images of novel social targets (strangers) was assessed. Approximately 24 hours later, participants reported on their feelings of social connection since leaving the scanner.

Results:

In the placebo condition, greater early maternal warmth was associated with less dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, anterior insula, ventral striatum, and amygdala activity in response to images of novel social targets (r’s−.360, p’s.031), and greater feelings of social connection (r=.524, p<.001) outside of the lab. The same relationships, however, were not present in the naltrexone condition.

Conclusions:

Results highlight relationships between early maternal warmth and responses to the social world at large and suggest that opioids might contribute to social connection by supporting the buffering effects of warm early life experiences on social connection later in life.

Trial Registration:

Clinical Trials NCT02818036

Keywords: maternal care, social exploration, social approach, naltrexone, brain opioid theory of social attachment

Feeling socially connected to others has significant health implications. A lack of social connection predicts and exacerbates disease such as cardiovascular disease and some cancers, and is its own clinical endpoint (1,2). Early social experiences may influence social connection later in life such that nurturing, warm experiences predict greater feelings of social connection (3,4). As early social relationships may provide a foundation to connect with others in adulthood, understanding neurochemical mechanisms supporting such experiences remain topics of considerable scientific interest. Endogenous opioids have been theorized to support the initiation and maintenance of social connection in humans and social approach behavior in animals (5). Further, individual differences in attachment style, which stem from early experiences with the caregiver, modulate sensitivity of the endogenous opioid system (6,7). Therefore, opioids may contribute to the link between early warmth (defined as nurturing, affectionate care that is responsive to one’s needs) and later social connection. The current study examined the role of opioids in linking retrospective reports of having received maternal warmth early in life with neural responses to social targets and feelings of social connection.

Early warmth and social connection

Correlational evidence suggests early maternal warmth affects later social connection, potentially by reducing barriers to approaching opportunities for connection. For instance, retrospective reports of early maternal warmth have been associated with less feelings of loneliness (8) and lower sensitivity to social rejection (negative social expectations including fear that interactions will result in rejection, 9). Early maternal warmth has also been related to clinical disorders characterized by social disconnection and withdrawal from novel social situations such that a lack of warmth predicts social phobia, social anxiety, and depression (10–13). Similarly, prospective evidence shows that maternal warmth increases coping behavior during childhood (14) and reduces risk of clinical disorders in adulthood among children high in anxiety and withdrawal (e.g., fearfulness, shyness in novel social contexts; 15). Thus, early maternal warmth is associated with greater approach toward opportunities for social connection in adulthood, suggesting early warmth may leave its mark on social connection later in life.

Opioids and social connection

The endogenous opioid system has long been theorized to contribute to social connection (5). Specifically, endogenous opioids may be released from the central nervous system (brain) during social interaction to facilitate social connection (e.g., 16). Blocking the central action of opioids pharmacologically prevents binding to opioid receptors, particularly mu-receptors, and may disrupt social connection and related behavior (for review see 17). Relevant to the current hypotheses, opioid antagonism (vs. placebo or control) decreased bonding behavior in animals (18–20) and increased barriers to social connection (distress vocalizations during social interaction, 21). Similar effects have emerged in humans. Naltrexone (vs. placebo), decreased interest for attractive strangers (22), feelings of social connection toward strangers in laboratory settings (23–25), and daily feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory (26), suggesting opioids support social connection toward a range of possible opportunities to connect. Whether opioids support positive associations between early warmth and later opportunities for social connection have not been examined.

The current study hypothesizes that early maternal warmth will relate to processes that support social connection later in life. Of particular interest are neural regions that encode socio-emotional information that may be a barrier to social connection, including the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (DACC), anterior insula (AI), ventral striatum (VS), and amygdala. All four regions have been identified as key hubs of the brain’s response to emotional content, regardless of valence, in meta-analyses (27–30) and consistently activate to personally relevant social information (31,32). The DACC and AI also integrate stimuli from the environment to help an organism decide how to act next, such as when approaching new social targets (33). Most relevant to the current study goals, the ACC, AI, VS, and amygdala are densely concentrated with μ-opioid receptors (34) and have been shown to reduce μ-receptor availability (indicating a release of endogenous opioids relative to baseline) to novel social targets in PET imaging (35). Therefore, DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to novel social targets may be (a) related to social connection and (b) supported by endogenous opioids.

Consistent with this notion, results from patient samples with symptoms characterized by social disconnection and withdrawal show increased activity in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala to novel social targets relative to non-patient controls (36–38). For example, anxiety-prone individuals, relative to non-anxious controls, show increased AI and amygdala activity in response to viewing emotional faces, including angry, fearful, and happy expressions (37). Similarly, increased activity to social stimuli in these regions is associated with greater social anxiety symptoms (39,40). Thus, heightened activity may indicate less social approach. In turn, dampening activity in these regions in response to new opportunities for connection may facilitate exploration of the social world more broadly. To the extent that early maternal warmth promotes approach toward social connection later in life, higher levels of maternal warmth may be associated with less activity in these regions in response to novel social targets.

The current study examined relationships between retrospective reports of early warmth, brain activity in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala to novel social targets (i.e., strangers) and feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory. In addition, the causal influence of opioids, previously implicated in social connection in animals and humans, on links between early warmth and social connection were evaluated with a pharmacological manipulation. Three hypotheses were tested. First, greater perceptions of early warmth were hypothesized to be associated with reduced brain activity to strangers. Second, following previous correlational findings between maternal warmth and social connection (8) greater perceptions of early warmth were hypothesized to relate to greater feelings of social connection. Finally, should endogenous opioids support long-term buffering effects of warm early life experiences on social connection later in life, the same relationships were not expected in the naltrexone condition.

Method

Participants and Screening

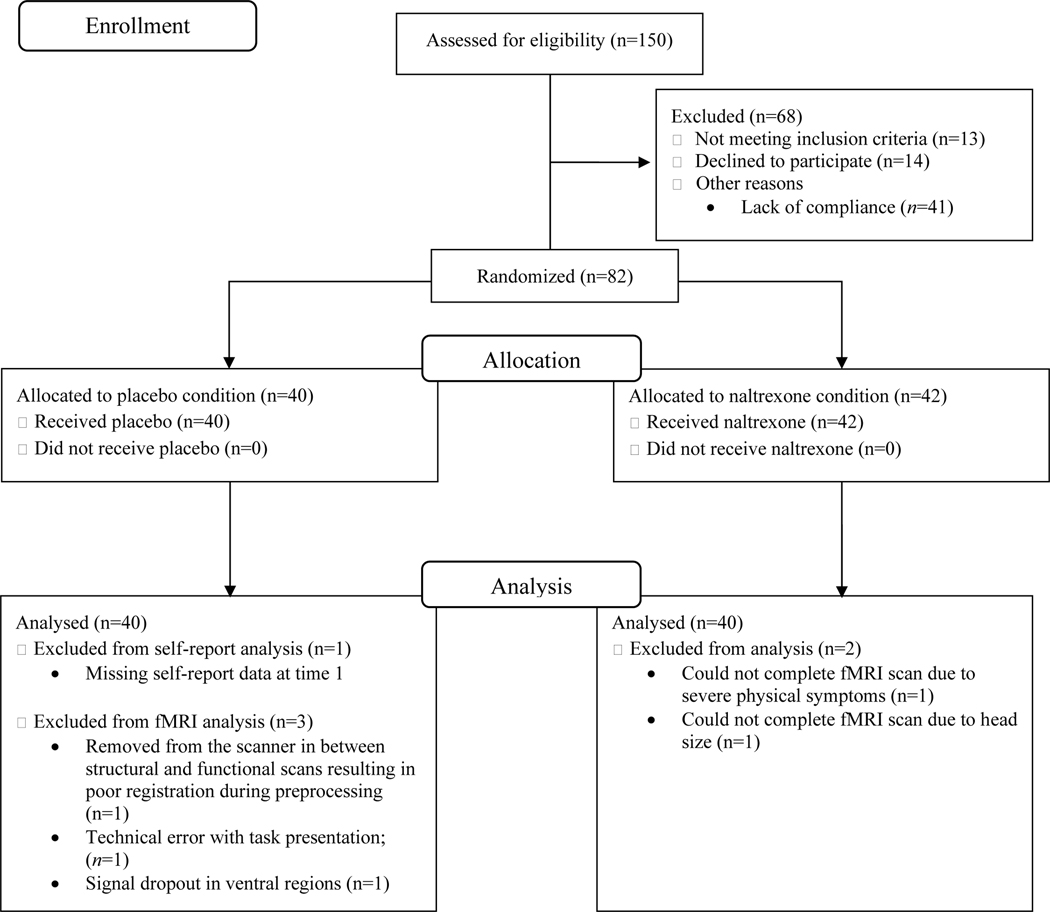

In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial, eighty-two participants were administered 50mg of oral naltrexone or placebo. A target sample size of 80 participants was determined following a power analysis (β=.80, α=.05) using effect sizes from prior research on the effect of pharmacological challenges on feelings of social connection (26,41). Two participants from the naltrexone condition did not complete the fMRI scan leaving a final sample of 80 participants (see Table 1 for demographics and Fig. 1 for CONSORT flow diagram).

Table 1.

Sample Demographics

| Placebo (n=40) | Naltrexone (n=40) | |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age (SD) | 22.88 (3.20) | 21.90 (3.49) |

| Range | 18–31 | 18–31 |

| Sex (%) | ||

| Female | 52.5 | 67.5 |

| Male | 47.5 | 32.5 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||

| Asian | 30 | 25 |

| Black | 5 | 2.5 |

| White | 57.5 | 67.5 |

| Other | 5 | 5 |

| Missing | 2.5 | 0 |

Figure 1.

CONSORT Flow Diagram depicting participant recruitment through data analysis.

Recruitment took place via flyers and posting to Pitt + Me, a voluntary research registry. Interested individuals underwent a two-stage screening process beginning with a telephone interview followed by an in-person visit with the study physician (CA). Inclusion criteria were good self-reported health, fluency in English, and age between 18–35. Participants were excluded for contraindications for naltrexone or MRI, and general health: positive urine pregnancy or drug test (Opiates, Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), Cocaine, Amphetamines (AMP), Methamphetamines (mAMP)), medication use other than birth control, depressive symptoms above a 9 on the PHQ-9 (Patient Health Questionnaire, 42), alcohol use above 14 drinks/week or 4 drinks/occasion for men and 3 drinks/occasion for women (following current CDC guidelines), self-reported mental or physical illness, including hepatic illness, body mass index greater than 35, non-removable MR-incompatible metal in the body, or claustrophobia.

The study was run between September 2016 and June 2018 following approval from the University of Pittsburgh’s Human Research Protection Office and registration as a clinical trial on the U.S. National Institutes of Health Clinical Trials registry (NCT02818036: An fMRI study of opioid-related changes in neural activity). Participants provided written consent prior to commencing procedures and received $90 in exchange for completing the study.

Hypothesis generation occurred prior to secondary data analyses on an existing dataset, but after the publication of results from the primary aims (43,44). Detailed descriptions of the experimental visit (Time 2) have been reported in prior publications, but are summarized here. The current data has not been reported previously. However, other results from the current study have been reported including physical symptoms in response to the drug manipulation at Time 2 (43,44). Results are separated because each paper tests separate theoretical questions.

Time 1: Maternal warmth

To assess perceptions of early maternal warmth, participants completed the care subscale of the Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; 13), a widely-used measure to assess early warmth. Previous findings suggest that perceptions of mothers, more than fathers, are associated with social connection (12), therefore, participants were asked about perceptions of their mothers only. Ratings of the mother during childhood up until age 16 were made on a 0–3 scale anchored by “very unlikely” and “very like.” Sample items include “spoke to me in a warm and friendly voice”, “could make me feel better when I was upset.” The PBI was missing from one participant in the placebo condition. There were no differences in perceptions of maternal warmth between drug condition (t(77)=.736, p=.46). Scores on the PBI were high such that the average score in the current sample was above the cutoff for high warmth as outlined in Parker et al., 1979 (M=29.899, SD =6.113, α =.921).

Time 2: Drug administration and brain activity to novel social targets

Upon arrival to the experimental session, participants were administered either placebo or naltrexone in a parallel design using block randomization (blocks of four) by an individual unassociated with the study. To maintain the study’s double-blind, study drugs were packaged in identical, indistinguishable capsules. Naltrexone is an FDA approved drug used in maintenance treatment for addiction, but is also used off-label for research purposes and is ideal for testing the current hypotheses because it is a full opioid antagonist that crosses the blood brain barrier to causally change opioid receptor binding in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala (45). When combined with neuroimaging methods, effects of naltrexone can be isolated to central (brain) effects and, when combined with a placebo condition, allows causal inference. Further, naltrexone is safe and well tolerated.

Sixty minutes after drug administration, when naltrexone shows peak effects (46), participants completed an MRI scan. Brain activity associated with processing social targets was evaluated with a task commonly used to assess neural correlates of viewing novel and familiar social targets (41,47–49). In a block design, participants viewed images of smiling strangers and in separate blocks, gender, race, and age-matched familiar people. The additional standard control condition for this task is mental serial subtraction (e.g., count back by 7’s from 1753). The inclusion of serial subtraction is meant to ‘erase’ any carryover feelings from viewing the social targets and is commonly used as a comparison condition (41,48,49). Eight 16-s blocks (four stranger, four familiar social targets) separated by a 1-s fixation crosshair, interleaved with 12-s blocks of serial subtraction were presented via E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA).

The primary goal of the current analyses was to examine associations between early maternal warmth and brain activity to novel social targets as a correlate of approach toward new opportunities for social connection. Therefore, we examined DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity in response to images of strangers (compared to baseline and compared to the serial subtraction condition). For associations between maternal warmth and brain activity to familiar social targets, see Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content 1. Three participants from the placebo condition were excluded from imaging analyses (Fig. 1).

Time 3: Feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory

Although the half-life of naltrexone is ~4 hours, the drug does not fully metabolize until ~48 hours after ingestion and remains in the plasma at measurable concentrations through 12 hours post-administration (46). Therefore, the day after the MRI session, participants reported on how they felt over the past 24 hours since leaving the scanner. Feelings of social connection were measured via responses to the following two items on a 1 (not at all) – 7 (very) scale: I felt accepted by others and connected to them; I felt out of touch and disconnected from others (reverse-coded). The items were taken from previous studies examining feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory setting (49,50). Responses were averaged.

fMRI Data Acquisition

Scanning took place on a Siemens 3T MAGNETOM Prisma MRI Scanner housed at the University of Pittsburgh’s MR Research Center. Scans began with a Magnetization Prepared Rapid Gradient Echo scan (MPRAGE; TR/TE=5000/2.97ms, flip angle=4°, 256×256 matrix, 177 sagittal slices, FOV=258; 1mm thick) followed by functional scans. Participants completed one run of the task (4mins, 23secs, T2* weighted gradient-echo covering 60 axial slices, TR/TE=1000/28 ms; flip angle=55˚; 112 × 112 matrix; FOV=220mm; 2mm thick). In addition, participants completed a messages task and a temperature task. Results from both tasks are reported separately (43,44).

Data Analyses

Neuroimaging Data

Preprocessing for imaging data occurred via Diffeomorphic Anatomical Registration through Exponentiated Lie Algebra (DARTEL) procedure in SPM8 (Wellcome Department of Imaging Neuroscience, London). Images were motion corrected, realigned, normalized to the MPRAGE, warped into Montreal Neurologic Institute (MNI) space, and smoothed with an 5mm Gaussian kernel, full width at half maximum (FWHM). For the current aims, the focus was on linear contrasts for the comparison of strangers vs. baseline and strangers vs. serial subtraction. Contrasts were computed at the single-subject level, then brought to the group-level for analyses. Although serial subtraction and implicit baseline (i.e., fixation crosshair) are imperfect comparisons for assessing activity over and above viewing faces or social stimuli, the current aims are focused on differences between drug condition and on associations between early maternal warmth and social connection-related outcomes. Both contrasts were examined and are included in all reporting as evidence of the consistency of associations.

Region-of-Interest (ROI) Analyses

Given the a-priori hypotheses regarding brain activity to novel social targets, we examined activity in the DACC, and bilateral AI, VS, and amygdala, regions that have previously been shown to activate to socio-emotional information (27–32,36,51), and that are densely concentrated in mu-opioid receptors (34,45,52). ROIs were structurally defined using the Automated Anatomical Labeling (AAL) atlas (53). The DACC was further constrained at 32<y<0 on the basis of a previous review of the cingulate cortex (54). We divided the insula at y=8, the approximate boundary between the dysgranular and granular sectors to constrain analyses to the anterior portion. Finally, the VS was further constrained at −10<x <10, 4<y<18, −12<z<0 following previous use of this ROI to the same scanner task (41,48).

Relationships between maternal warmth and social connection

The current hypotheses are that early maternal warmth will be related to reduced DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to novel social targets and greater feelings of social connection. To test hypotheses, we ran separate Pearson correlations between scores on the care-subscale of the PBI and DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to images of strangers (vs. baseline and vs. serial subtraction) and then feelings of social connection outside of the lab in the placebo group. 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated using the bias corrected and accelerated percentile bootstrap method (BCa) with 1000 random samples with replacement. Significance was determined at an α of .05, two tailed, and/or a BCa 95% CI excluding 0.

Effect of naltrexone on brain activity and feelings outside of lab

To assess the effect of naltrexone (vs. placebo) on DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to strangers and feelings of social connection outside of the lab, parameter estimates from each ROI for the stranger blocks (vs. baseline and vs. serial subtraction) and feelings of social connection collected 24 hours after drug administration were evaluated with independent samples t-tests.

Relationships between maternal warmth and social connection in naltrexone condition

We also hypothesized that relationships between early maternal warmth and social connection in the placebo condition would not be present in the naltrexone condition. Pearson correlations between scores on the care-subscale of the PBI and DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity in response to images of strangers (vs. baseline and vs. serial subtraction) and feelings of social connection outside of the lab were therefore run again in the naltrexone group. To assess the strength of any drug effect, the significance of the difference between correlations in each drug condition were assessed by Fisher r-to-z transformations of the correlation coefficients.

Raw data and syntax can be found on the Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/x8sqe/.

Results

Relationship between maternal warmth and brain activity to novel social targets

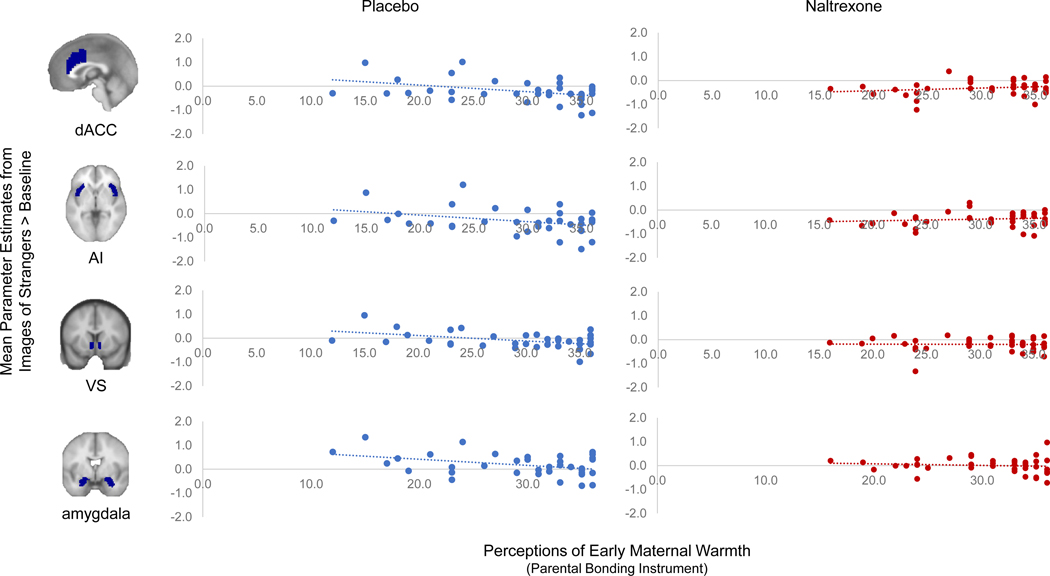

The current theoretical perspective suggests early warmth may predict greater social connection later in life. Therefore, we examined the relationship between early maternal warmth and brain activity to novel social targets as a correlational test of this notion. As hypothesized, in the placebo group, there was a negative correlation between perceptions of maternal warmth and DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to strangers (vs. baseline and vs. serial subtraction) such that greater retrospective reports of maternal warmth at Time 1 were associated with less brain activity to images of strangers at Time 2 (Fig. 2, Table 2).

Figure 2.

Relationships between maternal warmth and brain activity to strangers in each drug condition separately. Greater perceptions of early maternal warmth were associated with less dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (DACC), anterior insula (AI), ventral striatum (VS), and amygdala activity to strangers (vs. baseline – pictured above, and vs. serial subtraction) in the placebo group. The same relationships between maternal warmth and brain activity were absent in those who took naltrexone.

Table 2.

Associations between retrospective perceptions of early maternal warmth as assessed by the PBI and brain activity to novel social targets (i.e., images of strangers).

| r | p | BCa 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo | |||

| Strangers > baseline | |||

| DACC | -.403 | .015* | [−.646, −.123] |

| AI | -.360 | .031* | [−.583, −.112] |

| VS | -.449 | .006* | [−.701, −.116] |

| amygdala | -.383 | .021* | [−.641, −.041] |

| Strangers > serial subtraction | |||

| DACC | -.394 | .017* | [−.637, −.118] |

| AI | -.375 | .024* | [−.620, −.101] |

| VS | -.369 | .027* | [−.678, −.011] |

| amygdala | -.304 | .071* | [−.564, −.001] |

| Naltrexone | |||

| Strangers > baseline | |||

| DACC | .199 | .21 | [−.118, .476] |

| AI | .133 | .41 | [−.125, .397] |

| VS | -.018 | .91 | [−.356, .276] |

| amygdala | -.127 | .43 | [−.420, .139] |

| Strangers > serial subtraction | |||

| DACC | -.049 | .76 | [−.337, .235] |

| AI | .108 | .50 | [−.174, .362] |

| VS | -.236 | .14 | [−.545, .067] |

| amygdala | -.226 | .16 | [−.527, .134] |

Note:

p<.05, two tailed, and/or BCa CI excluding 0. PBI=Parental Bonding Instrument (13), DACC=dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, AI=anterior insula, VS=ventral striatum, BCa=bias corrected and accelerated percentile bootstrap method, CI=confidence interval

In a pattern consistent with the suggestion that the brain activity evaluated for the current study is a barrier to social connection, DACC and AI activity in response to images of strangers (vs. baseline) and feelings of social connection outside of the lab were negatively correlated in the placebo group (Table 3). VS and amygdala activity were also negatively correlated with feelings of social connection at a statistically marginal level. That is, greater DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to strangers were associated with lower feelings of social connection.

Table 3.

Associations between brain activity in response to images of strangers and feelings collected outside of the lab in those administered placebo.

| r | p | BCa 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Feelings of Social Connection | |||

| Strangers > baseline | |||

| DACC | -.348 | .035* | -.531, −.104 |

| AI | -.321 | .052* | -.527, −.062 |

| VS | -.297 | .074 | -.566, .034 |

| amygdala | -.296 | .076 | -.528, .004 |

| Strangers > serial subtraction | |||

| DACC | -.383 | .019* | -.599, −.114 |

| AI | -.362 | .028* | -.593, −.072 |

| VS | -.231 | .16 | -.546, .152 |

| amygdala | -.229 | .17 | -.546, .119 |

Note:

p<.05, two tailed, and/or BCa CI excluding 0. DACC=dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, AI=anterior insula, VS=ventral striatum, BCa=bias corrected and accelerated percentile bootstrap method, CI=confidence interval

Relationship between maternal warmth and feelings of social connection outside of the lab

Again consistent with hypotheses, maternal warmth (Time 1) was positively correlated with feelings of social connection (Time 3). Those who perceived greater maternal warmth early in life also reported greater feelings of social connection outside of the lab setting (r =.524, p< .001, BCa 95% CI=[.135, .796]).

Effect of naltrexone on social connection

Naltrexone (vs. placebo) reduced amygdala activity to strangers (vs. baseline only, M placebo=.184, SD=.460, M naltrexone=.002, SD=.315, t(75)=2.036, p=.045, BCa 95% CI = [.004, .360]). Unexpectedly, there was no effect of naltrexone on DACC, AI, or VS activity (p’s>.16). However, in replication of previous findings (26), naltrexone (vs. placebo) decreased feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory setting (M placebo=5.888, SD placebo=.937; M naltrexone=5.450, SD naltrexone =1.197; t(78)=1.820, p=.073, BCa 95% CI [.007, .888]).

Maternal warmth and brain activity to novel social targets in naltrexone condition

Due to their theorized involvement in social connection in humans and animals, opioids may support associations between early maternal warmth and later social connection. Indeed, reports of early maternal warmth collected at Time 1 were not related to DACC, AI, VS, or amygdala activity to strangers in those who had taken naltrexone at Time 2 (Fig. 2, Table 2). The correlation in the placebo group was different from that in the naltrexone group for the DACC (vs. baseline: z=2.360, p=.009; vs. serial subtraction: z=1.530, p=.12), AI (vs. baseline: z = 2.130, p=.033; vs. serial subtraction: z = 2.100, p=.036), and VS (vs. baseline: z=1.940, p=.052; vs. serial subtraction: z=.610, p=.54), suggesting naltrexone moderated the early warmth-brain relationship for these regions. Correlations with amygdala were not different between drug condition (vs. baseline: z=1.190, p =.23; vs. serial subtraction: z=.350, p=.72).

Maternal warmth and feelings of social connection outside of the lab in naltrexone condition

Maternal warmth and feelings of social connection were not related in those who took naltrexone (r=.114, p=.48, BCa 95% CI=[−.171, .400]). The correlation present in the placebo group was significantly different from the correlation in the naltrexone group suggesting a comparatively strong drug effect (z=2.000, p=.046).

Discussion

Prior work suggests early maternal warmth may have lasting effects on social connection later in life such that a warm, nurturing mother facilitates greater social connection and a lack of warmth produces the opposite effects (3,4,55). In support of the current hypotheses, greater perceptions of early maternal warmth were associated with less activity in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala to novel social targets and greater feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory. The same relationships, however, were not present in those administered the opioid antagonist, naltrexone. Results highlight the endogenous opioid system as a potential contributor to positive effects of an early warm relationship on later social connection.

Early warmth and social connection

Outside of the well-known links between early warmth and stress-related outcomes in vulnerable populations less is known about how and whether early warmth relates to social connection absent a stressful context (e.g., 56–59). The current results broaden understanding for links between early warmth and later social connection by demonstrating that, in the placebo group, perceptions of early maternal warmth are associated with less DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala to novel social targets and greater feelings of social connection outside of the lab. Patterns support perspectives that early warmth molds an individual for later socializing, but extend these perspectives to show that the imprint left by early warmth also relates to social connection beyond the more well-known contexts of stress and threat, and further still beyond adult romantic relationships (55,60,61). Indeed, the current results suggest warmth is so critical early in life that it may lay the foundation for later behavior toward new opportunities for social connection.

The correlational patterns in the current study highlight a potential path by which early warmth and social connection are related. Specifically, DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity in response to novel opportunities to socialize, such as with a stranger, may be a barrier to social approach behavior (36–40). In the current study, feelings of connection were related to less activity in the same regions, principally the DACC and AI. Perceptions of early warmth were similarly related to less activity in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala in response to novel social targets. To the extent that early maternal warmth assists one in approaching opportunities for social connection later in life, the correlational patterns suggest: decreasing activity in the DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala to novel opportunities to socialize, in and of itself, may also increase social connection, and/or that early warmth may set or contribute to the threshold at which one approaches strangers. Lack of warmth may lead to a lower threshold to approach whereas high warmth may lead to a higher threshold.

However, the current results are correlational and therefore we can only conjecture based on previous theoretical models as to the causal direction of early warmth on brain activity to strangers and new experiences of social connection (57,60). Future longitudinal studies could incorporate measures of social connection toward a broader range of social targets or could compare those who perceive high vs. low warmth to better understand whether caregiver warmth, as measured early in life, relates to social connection, as measured later in life.

Opioid contribution to early warmth and social connection

Endogenous opioids support the initiation and maintenance of social connection in humans (6,23) and, as an extension of this theory, may maintain the positive relationships between early social experiences and later social connection. In replication of previous findings, naltrexone (vs. placebo) decreased feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory (26). Further, both the early warmth-brain and early warmth-affective experience relationships in the placebo group were not present in those who had been administered naltrexone. To our knowledge, these are the first results to suggest that naltrexone can alter social connection, potentially by disrupting the foundation from which individuals who grew up in warm, caring environments approach the social world.

Although naltrexone decreased feelings of social connection outside of the lab, no differences between drug condition were found for DACC, AI, or VS activity to strangers. Unexpectedly, naltrexone decreased, rather than increased, amygdala activity to viewing images of strangers – though only to the comparison of strangers vs. implicit baseline. Additional research is needed to replicate this effect before firm conclusions can be made about the effect of naltrexone on brain activity to new opportunities for social connection. Previous research outside the brain suggests that the effect of naltrexone on social responding can depend on state-level factors like the salience of the targets (17) and desire to interact with someone new, as well as trait level personality factors (23). Such moderators will be important to explore in future research. In addition, future research that adjusts for general or trait levels of social connection are needed when replicating naltrexone’s effect on state-level feelings of social connection.

Limitations are noted. Causal inference of maternal warmth on later social connection is not possible given the correlational nature of the findings and the use of retrospective reports of warmth may suffer from recall bias (62–64). Although there was no difference between drug condition in perceptions of early warmth at Time 1, future research would benefit from tighter control over individual differences by using a crossover, rather than between-subjects, drug manipulation. Viewing static images of strangers only approximates real-world social interaction. Future work would benefit from enhanced instructions (“imagine meeting this person”) or the use of video stimuli to better mirror the intended social experience. Finally, the focus of the current study was on the mother, but other individuals can be equally influential and integral to a child’s upbringing and may similarly influence later social connection. Caregivers identified as primary early relationships should be measured in future studies assessing effects of early social experience on social connection later in life.

Conclusion

The current study revealed relationships between perceptions of early maternal warmth and social connection later in life. Greater maternal warmth was related to less DACC, AI, VS, and amygdala activity to strangers and greater feelings of social connection outside of the laboratory; relationships that were not present in those administered naltrexone. Results have implications for connection with new opportunities for social interaction and suggest that opioids contribute to the broader experience of social connection by supporting the positive effects of early life experience on social connection later in life.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Digital Content 1. Table S1, associations between early maternal warmth and brain activity in response to familiar others in placebo and naltrexone conditions; Word document.

Acknowledgements

We thank the University of Pittsburgh Investigational Drug Service, members of the Social-Health and Affective Neuroscience (SHAN) Lab for their assistance running the study, and Edward Orehek for assistance with drug randomization and the study blind.

Source of Funding: The study was supported by a NARSAD Young Investigator Grant from the Brain & Behavior Foundation (TKI), NIMH grants R01MH108509 and R01MH076079 (CA), and NIH grant UL1TR001857.

Glossary

- AI

anterior insula

- BCa

bias corrected and accelerated percentile bootstrap method

- CI

confidence interval

- DACC

dorsal anterior cingulate cortex

- fMRI

functional magnetic resonance imaging

- PBI

Parental Bonding Instrument

- PET

positron emission tomography

- ROI

region of interest

- VS

ventral striatum

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: No conflicts of interest are declared for the authors.

References

- 1.Cacioppo JT, Cacioppo S, Capitanio JP, Cole SW. The Neuroendocrinology of Social Isolation. Annu Rev Psychol 2015;66:733–767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eisenberger NI, Moieni M, Inagaki TK, Muscatell KA, Irwin MR. In Sickness and in Health: The Co-Regulation of Inflammation and Social Behavior. Neuropsychopharmacol 2017;42:242–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowlby J. A secure base: Parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gadsden VL, Ford M, Breiner H. (Eds.). Parenting matters: Supporting parents of children ages 0–8. Washington DC: National Academies Press, 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Panksepp J, Herman BH, Vilberg T, Bishop P, DeEskinazi FG. Endogenous opioids and social behavior. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 1980;4:473–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nummenmaa L, Manninen S, Tuominen L, Hirvonen J, Kalliokoski KK, Nuutila P, Jääskeläinen IP, Hari R, Dunbar RI, Sams M. Adult attachment style is associated with cerebral μ-opioid receptor availability in humans. Hum Brain Mapp 2015, 36: 3621–3628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Troisi A, Frazzetto G, Carola V, et al. Variation in the μ-opioid receptor gene (OPRM1) moderates the influence of early maternal care on fearful attachment. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2012;7:542–547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wiseman H, Mayseless O, Sharabany R. Why are they lonely? Perceived quality of early relationships with parents, attachment, personality predispositions and loneliness in first-year university students. Pers Individ Dif 2006;40:237–248. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feldman S, Downey G. Rejection sensitivity as a mediator of the impact of childhood exposure to family violence on adult attachment behavior. Dev Psychopathol 1994;6:231–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Molle R, Portella AK, Goldani MZ, Kapczinski FP, Leistner-Segala S, Salum GA, Manfro GG, Silveira PP. Associations between parenting behavior and anxiety in a rodent model and a clinical sample: relationship to peripheral BDNF levels. Transl Psychiatry 2012;2:e195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enns MW, Cox BJ, Clara I. Parental bonding and adult psychopathology: results from the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med 2002;32:997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parker G, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Greenwald S, Weissman M. Low parental care as a risk factor to lifetime depression in a community sample. J Affect Disord 1995;33:173–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parker G, Tupling H, Brown LB. A Parental Bonding Instrument. Br J Med Psychol 1979;52:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Watson KH, Dunbar JP, Thigpen J, Reising MM, Hudson K, McKee L, Forehand R, Compas BE. Observed parental responsiveness/warmth and children’s coping: cross-sectional and prospective relations in a family depression preventive intervention. J Fam Psychol 2014; 28:278–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jakobsen IS, Horwood LJ, Fergusson DM. Childhood anxiety/withdrawal, adolescent parent–child attachment and later risk of depression and anxiety disorder. J Child Fam Stud 2012; 21:303–310. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keverne EB, Martensz ND, Tuite B. Beta-endorphin concentrations in cerebrospinal fluid of monkeys are influenced by grooming relationships. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1989;14:155–161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Loseth GE, Ellingsen D, Leknes S. State-dependent mu-opioid modulation of social motivation. Front Behav Neurosci 2014;8:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jalowiec JE, Calcagnetti DJ, Fanselow MS. Suppression of juvenile social behavior requires antagonism of central opioid systems. Pharmacol Biochem and Behav 1989;33:697–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moles A, Kieffer BL, D’Amato FR. Deficit in Attachment Behavior in Mice Lacking the μ-Opioid Receptor Gene. Science 2004;304:1983–1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shayit M, Nowak R, Keller M, Weller A. Establishment of a preference by the newborn lamb for its mother: The role of opioids. Behav Neurosci 2003;117:446–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Panksepp J, Bean NJ, Bishop P, Vilberg T, Sahley TL. Opioid blockade and social comfort in chicks. PharmacoL Biochem Behav 1980;13:673–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chelnokova O, Laeng B, Eikemo M, Riegels J, Løseth G, Maurud H, Willoch F, Leknes S. Rewards of beauty: the opioid system mediates social motivation in humans. Mol Psychiatry 2014;19:746–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Depue RA, Morrone-Strupinsky JV. A neurobehavioral model of affiliative bonding: implications for conceptualizing a human trait of affiliation. J Behav Brain Sci 2005;28:313–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schweiger D, Stemmler G, Burgdorf C, Wacker J. Opioid receptor blockade and warmth-liking: effects on interpersonal trust and frontal asymmetry. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2014;9:1608–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarr B, Launay J, Benson C, Dunbar RIM. Naltrexone Blocks Endorphins Released when Dancing in Synchrony. Adapt Human Behav Physiol 2017;3:241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inagaki TK, Ray LA, Irwin MR, Way BM, Eisenberger NI. Opioids and social bonding: naltrexone reduces feelings of social connection. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2016;11:728–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cameron OG. Visceral brain-body information transfer. Neuroimage 2009;47:787–794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kraynak TE, Marsland AL, Wager TD, Gianaros PJ. Functional neuroanatomy of peripheral inflammatory physiology: a meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2018;94:76–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lindquist KA, Wager TD, Kober H, Bliss-Moreau E, Barrett LF. The brain basis of emotion: a meta-analytic review. Behav Brain Sci 2012;35:121–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Seeley WW. The Salience Network: A neural system for perceiving and responding to homeostatic demands. J Neurosci. 2019;11;39:9878–9882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bickart KC, Dickerson BC, & Barrett LF The amygdala as a hub in brain networks that support social life. Neuropsychologia 2014;63:235–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.(Bud) Craig AD. How do you feel — now? The anterior insula and human awareness. Nat Rev Neurosci 2009;10:59–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, Reiss AL, Greicius MD. Dissociable Intrinsic Connectivity Networks for Salience Processing and Executive Control. J Neurosci 2007;27:2349–2356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cross AJ, Hille C, Slater P. Subtraction autoradiography of opiate receptor subtypes in human brain. Brain Res 1987;418:343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hsu DT, Sanford BJ, Meyers KK, Love TM, Hazlett KE, Wang H, Lisong N, Walker SJ, Mickey BJ, Korycinski ST, Koeppe RA, Crocker JK, Langenecker SA, Zubieta JK. Response of the μ-opioid system to social rejection and acceptance. Mol Psychiatry 2013;18:1211–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amir N, Klumpp H, Elias J, Bedwell JS, Yanasak N, Miller LS. Increased activation of the anterior cingulate cortex during processing of disgust faces in individuals with social phobia. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57:975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stein MB, Simmons AN, Feinstein JS, Paulus MP. Increased amygdala and insula activation during emotion processing in anxiety-prone subjects. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164:318–327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hadland KA, Rushworth MFS, Gaffan D, Passingham RE. The effect of cingulate lesions on social behaviour and emotion. Neuropsychologia 2003;41:919–931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Phan KL, Fitzgerald DA, Nathan PJ, Tancer ME. Association between amygdala hyperactivity to harsh faces and severity of social anxiety in generalized social phobia. Biol Psychiatry 2006;1;59(5):424–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1476–1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inagaki TK, Muscatell KA, Irwin MR, Moieni M, Dutcher JM, Jevtic I, Breen EC, Eisenberger NI. The role of the ventral striatum in inflammatory-induced approach toward support figures. Brain Behav Immun 2015;44:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Patient Health Questionnaire Primary Care Study Group. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: the PHQ primary care study. JAMA 1999;282:1737–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Inagaki TK, Hazlett LI, Andreescu C. Naltrexone alters responses to social and physical warmth: implications for social bonding. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2019;14:471–479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inagaki TK, Hazlett LI, Andreescu C. Opioids and social bonding: Effect of naltrexone on feelings of social connection and ventral striatum activity to close others. J Exp Psychol Gen 2019;149:742–745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weerts EM, Kim YK, Wand GS, Dannals RF, Lee JS, Frost JJ, McCaul ME Differences in delta- and mu-opioid receptor blockade measured by positron emission tomography in naltrexone-treated recently abstinent alcohol-dependent subjects. Neuropsychopharmacology 2008;33:653–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wall ME, Brine DR, Perez-Reyes M. Metabolism and disposition of naltrexone in man after oral and intravenous administration. Drug Metab Dispos 1981;9:369–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Acevedo BP, Aron A, Fisher HE, Brown LL. Neural correlates of long-term intense romantic love. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2012;7:145–159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Inagaki TK, Muscatell KA, Moieni M, Dutcher JM, Jevtic I, Irwin MR, Eisenberger NI. Yearning for connection? Loneliness is associated with increased ventral striatum activity to close others. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2016;11:1096–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aron A, Fisher H, Mashek DJ, Strong G, Li H, Brown LL. Reward, motivation and emotion systems associated with early-stage intense romantic love. J Neurophysiol 2005;93:327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Inagaki TK, Human LJ. Physical and social warmth: Warmer daily body temperature is associated with greater feelings of social connection. Emotion 2019;20:1093–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muscatell KA, Eisenberger NI. A social neuroscience perspective on stress and health. Soc Personal Psychol Compass 2012;6:890–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jones AK, Kitchen ND, Watabe H, Cunningham VJ, Jones T, Luthra SK, Thomas DG. Measurement of changes in opioid receptor binding in vivo during trigeminal neuralgic pain using [11C] diprenorphine and positron emission tomography. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 1999;19:803–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tzourio-Mazoyer N, Landeau B, Papathanassiou D, Crivello F, Etard O, Delcroix N., … Joliot M. Automated anatomical labeling of activations in SPM using a macroscopic anatomical parcellation of the MNI MRI single-subject brain. NeuroImage 2002;15:273–289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vogt BA, Berger GR, Derbyshire SWG. Structural and Functional Dichotomy of Human Midcingulate Cortex. 2003. Eur J Neurosci;18:3134–3144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hazan C, Shaver P. Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. J Pers Soc Psychol 1987;52:511–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen E, Miller GE, Kobor MS, Cole SW. Maternal warmth buffers the effects of low early-life socioeconomic status on pro-inflammatory signaling in adulthood. Mol Psychiatry 2011;16:729–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miller GE, Chen E, Parker KJ. Psychological Stress in Childhood and Susceptibility to the Chronic Diseases of Aging: Moving Towards a Model of Behavioral and Biological Mechanisms. Psychol Bull 2011;137:959–997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull 2002;128:330–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Millner A, Gilhooly T, Zevin JD, Casey BJ. Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation: Neurodevelopment and adversity. Dev Sci 2011;14:190–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hertzman C. The Biological Embedding of Early Experience and Its Effects on Health in Adulthood. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1999;896:85–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hostinar CE, Sullivan RM, Gunnar MR. Psychobiological mechanisms underlying the social buffering of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical axis: a review of animal models and human studies across development. Psychol Bull. 2014;140:256–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hardt J, Vellaisamy P, Schoon I. Sequelae of prospective versus retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences. Psychol Rep 2010;107:425–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Reuben A, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Belsky DW, Harrington H, Schroeder F, Hogan S, Ramrakha S, Poulton R, Danese A. Lest we forget: comparing retrospective and prospective assessments of adverse childhood experiences in the prediction of adult health. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2016;57:1103–1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yancura LA, Aldwin CM. Stability and change in retrospective reports of childhood experiences over a 5-year period: findings from the Davis longitudinal study. Psychol Aging 2009;24:715–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Digital Content 1. Table S1, associations between early maternal warmth and brain activity in response to familiar others in placebo and naltrexone conditions; Word document.