Abstract

Basing on alternative splicing events (ASEs) databases, the authors herein aim to explore potential prognostic biomarkers for cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CESC). mRNA expression profiles and relevant clinical data of 223 patients with CESC were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA). Correlated genes, ASEs and percent‐splice‐in (PSI) were downloaded from SpliceSeq, respectively. The PSI values of survival‐associated alternative splicing events (SASEs) were used to construct the basis of a prognostic index (PI). A protein–protein interaction (PPI) network of genes related to SASEs was generated by STRING and analysed with Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Consequently, 41,776 ASEs were discovered in 19,724 genes, 2596 of which linked with 3669 SASEs. The PPI network of SASEs related genes revealed that TP53 and UBA52 were core genes. The low‐risk group had a longer survival period than high‐risk counterparts, both groups being defined according to PI constructed upon the top 20 splicing events or PI on the overall splicing events. The AUC value of ROC reached up to 0.88, demonstrating the prognostic potential of PI in CESC. These findings suggested that ASEs involve in the pathogenesis of CESC and may serve as promising prognostic biomarkers for this female malignancy.

Inspec keywords: gynaecology, molecular biophysics, genomics, proteins, cellular biophysics, genetics, medical computing, cancer, ontologies (artificial intelligence), RNA

Other keywords: protein‐protein interaction network, CESC pathogenesis, gene ontology, Kyoto‐encyclopedia‐of‐genes‐and‐genomes, SASEs related genes, PPI network, survival‐associated alternative splicing events, PSI values, percent‐splice‐in, Cancer Genome Atlas, mRNA expression profiles, prognostic biomarkers, alternative splicing events databases, cervical squamous cell carcinoma, prognostic alternative splicing signature

1 Introduction

Cervical squamous cell carcinoma (CESC) is a common female cancer affected by multiple variables with slow progression. According to Global Cancer Statistics 2018, the morbidity and mortality rates of CESC were the second highest, remaining one of the major causes of death for women with cancers [1 ]. However, its detailed pathogenesis was not fully explained in existing studies, but it was widely accepted that cervical cancer was caused mainly by HPV infection and DNA methylation of affected genes [2 ]. In most countries, the common preventive practices for CESC include injection of HPV vaccine as well as cervical screening. Nevertheless, these protocols may reduce the morbidity rate, but have no therapeutic effects on CESC [3 ]. Currently, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) staging was still used in the diagnosis and treatment of cervical cancer, whose therapeutic effects may be influenced by the subjective judgment and personal experience of physicians [4 ]. Furthermore, most patients with cervical cancer have a high incidence of recurrence or metastasis after an operation, and the five‐year survival rate is as low as 10–20% [5 ]. In a word, there is no better cure for cervical cancer at present, the seeking for new prognostic indicators for this malignancy is thus necessary and urgent.

In eukaryotes, the pre‐RNA binds to diverse splicing sites, removing introns and connecting different exons, thereby generating various mRNA splice variants. This process is technically called alternative splicing [6 ]. Currently, seven splice variants have been defined – exon skipping (ES), mutually exclusive exons (ME), retained intron (RI), alternative promoter (AP), alternative terminator (AT), alternative donor site (AD) and alternative acceptor site (AA) [7 ].

A plethora of studies had revealed that more than 95% of genes of eukaryotes have alternative splicing events, suggesting that alternative splicing may extensively participate in biological processes like cell development, histodifferentiation, etc. [8 –10 ]. Therefore, abnormal variations of splicing may induce the development of multiple diseases, including cancer. Recently, Pan et al. and other groups revealed that the abnormal splicing of mRNA caused such diseases as inflammatory bowel disease, Alzheimer's disease, atherosclerosis disease [11 –15 ]. Data from Lawes et al. and other teams discovered that some tumours, e.g. colorectal cancer, ovarian cancer, may result from alterations in alternative splicing of affected genes, such as inactivity of splicing factors, mutations of regulatory elements or post‐transcriptional disruptions [16 –19 ]. Taken together, increasing evidence indicate that alternative splicing events have emerged as promising biological markers in the development, progression and prognosis of carcinomas, which may further provide new therapeutic targets for malignant disorders including cervical cancer [20 –23 ]. Herein, based on bioinformatic databases such as TCGA and SpliceSeq, we analyse cervical cancer associated with alternative splicing events, construct prognostic index (PI), receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and Kaplan–Meier (K‐M) curves, in an attempt to unravel potential prognostic biomarkers and to seek new therapeutic targets for this female malignancy.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Data processing

The clinical parameters and survival data of patients with cervical cancer were obtained from the TAGA database (https://gdc.cancer.gov/ ). A total of 223 cases of cervical cancer were included in the current study, with a minimum survival period of 90 days. Alternative splicing events were represented with percent‐splice‐in (PSI), which was calculated by the number of reads where splice in occurred divided by the number of reads where both splice in and splice out occurred. The PSI value varied between 0 and 1, representing the percentage of reads where certain exons existed. The PSI values of alternative splicing events concerning cervical cancer were downloaded from TCGA SpliceSeq. (http://bioinformatics.mdanderson.org/TCGASpliceSeq ), and the gene‐splicing would be quantified.

2.2 Display of alternative splicing events

As mentioned above, there are seven types of gene alternative splice variants – ES, AT, AP, AD, AA, RI and ME. Each gene could have one or more alternative splicing events. To demonstrate the overall genes splicing events more clearly, we plotted a visual graph of the splice events basing on these seven splice variants with the UpSet R package of the R software.

2.3 PI construction and assessment of survival prognosis

Cervical cancer‐associated alternative splice events were determined by univariate Cox regression analysis (p <0.05). The top 20 splicing events in each type were then selected for multivariate Cox regression analysis to exclude the influences of dependent factors (except survival time) on the prognosis of cervical cancer. We selected the top 20 most significant survival associated with splicing events for further analysis. The top 20 splicing events are the most representative molecular biomarkers and this threshold was widely used by previous studies [24, 25 ]. After this was done, prognostic risk value, i.e. PI was calculated for whose P‐ value is less than 0.05 in the multivariate Cox regression analysis with the formula below:

| (1) |

Finally, the included cases were classified into high risk and low‐risk groups based on the median value of PI. K‐M and ROC curves were used to evaluate the prognostic potential of PI in cervical cancer. Time‐dependent ROC curves were drawn with the ‘survival ROC’ package of the R software.

2.4 Construction of PPI network and functional enrichment analysis

Survival‐associated alternative splicing events (SASEs) and SASEs‐related genes with p <0.05 which are filtrated by univariate Cox regression were chosen for protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction and functional enrichment analysis with STRING (https://string‐db.org/ ). The core genes in the PPI network were defined for whose connect node ≥ 10, which appeared indispensable in the network. Genes related to alternative splicing events with prognostic potential were performed functional enrichment analyses with Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) on The Database for Annotation, Visualisation and Integrated Discovery (David, version 6.8) (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/summary.jsp ). The results of GO and KEGG analyses were illustrated with Package ggplot2 of R 4.3.2.

2.5 Construction of network between splicing events and splicing factors and correlation analysis

Generally, splicing events were regulated by multiple splicing factors. 64 splicing factors were obtained from SpliceAid2 (http://www.introni.it/splicing.html ), 15 of which were chosen for further analyses due to their differential expression between CESC and control tissues via GEPIA (http://gepia.cancer‐pku.cn ). All these factors might be linked with significant prognostic splicing events. The association between PSI with a significant prognostic value and mRNA expressions of splicing factors was evaluated by Pearson correlation analyses. To visually reflect the relationship between alternative splicing factors and splicing events, we drew a network diagram to illustrate the splicing factors that expressed differentially and their related prognostic splicing events with Reactome FI of Cytoscape 3.6.0.

3 Results

3.1 Overview of splicing events in cervical cancer

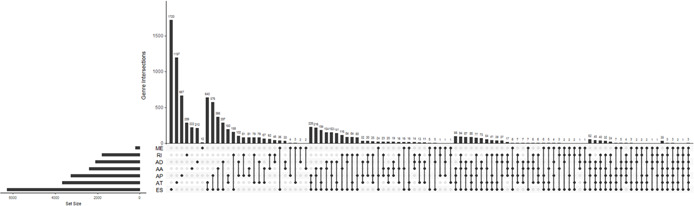

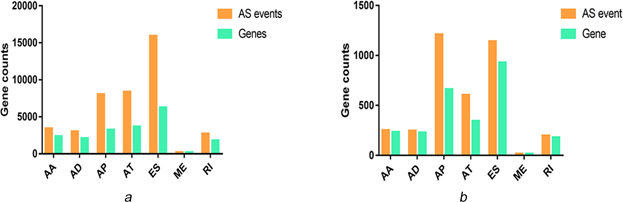

In this study, a total of 41,776 alternative splicing events encompassing 19,724 genes were detected in cervical cancer, including 15,942 ES, 8395 AT, 8066 AP, 3071 AD, 3424 AA, 2723 RI and 209 ME events in 6282, 3761, 3264, 2106, 2398, 1801 and 202 genes, respectively. These data demonstrate that alternative splicing events frequently occurred in cervical cancer, with one gene presenting multiple events. As shown in Fig. 1, which was depicted visually by UpSet, ES comprised the highest proportion among the seven types of splicing variants, in which 2596 genes related to survival time where 3669 splicing events took place (Fig. 2 ), clearly implicating that one gene exhibits several splicing events.

Fig 1.

UpSet plot of seven types of slicing events in cervical cancer. AA, alternate acceptor site, AD, alternate donor site, AP, alternate promoter, AT, alternate terminator, ES, exon skip, ME, mutually exclusive exons, RI, retained intron

Fig 2.

Alternative splicing events occurring in genes in cervical cancer

(a) Number of genes and related splicing events in cervical cancer, (b) Prognostic splicing events in cervical cancer and the number of genes. Orange bars, splicing events; green bars, genes

3.2 Correlation between cervical cancer splicing events and survival time

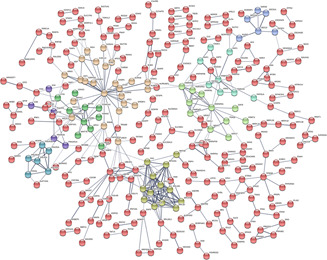

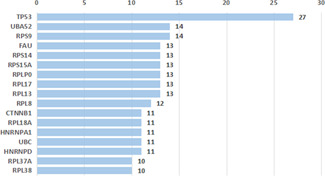

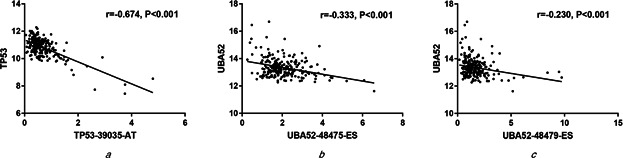

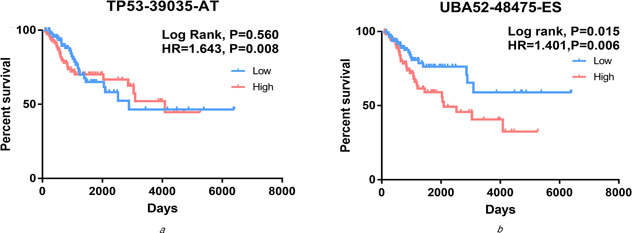

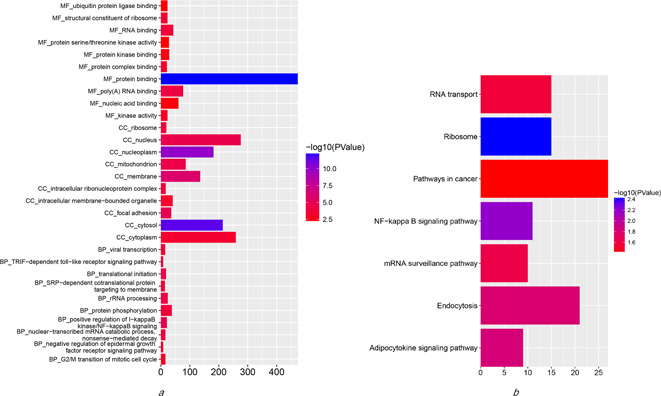

To evaluate the correlations between cervical cancer splicing events and survival time, we used the statistically significant genes (P <0.05) filtrated by univariate Cox regression analyses to draw a histogram and a PPI network via STRING website. As shown, 15 core gene was defined, i.e. TP53, UBA52, RPS9, FAU, RPS14, PRS15A, RPLP0, RPL17, RPL13, RPL18, CTNNB1, RBL18A, HNRNPA1, UBC and HNRNPD (connect node >10) (Figs. 3 and 4 ). The association between mRNA expression of these genes and corresponding splicing events were subsequently analysed and the mRNA expressions of TP53 and UBA52 were found to strongly correlate with the alternative splicing events (P <0.01) (Fig. 5 ). Further, K‐M curves analysis of TP53 and UBA52 suggested that these two genes had relationships with the survival time of patients with cervical cancer (Fig. 6 ). In the survival analysis, we explored the relationships between splicing events and the prognosis of CESC patients. However, the P ‐value of TP53‐39035‐AT in the Long rank test is bigger than 0.05, which was due to the different methods of testing. To interpret the roles of SASEs related genes, we carried out GO analysis on these genes, discovering that gene functions were mainly observed in such pathways as MF‐protein binding, cc‐cytosol, cc‐nucleoplasm, cc‐membrane, CC‐focal adhesion and so on. Further, KEGG functional enrichment analyses revealed that the major pathways fall in the ribosome, NF‐κB signalling pathway, endocytosis, adipocytokine signalling pathway, etc. (Fig. 7 ).

Fig 3.

Protein‐protein interaction (PPI) network for significant cervical cancer‐related genes determined by univariate Cox regression analyses. P <0.05. The network was drawn based on STRING website

Fig 4.

Connection of prognostic factors of cervical cancer in the PPI network. Core genes are whose connect node >10

Fig 5.

Correlations of mRNA expression of core genes TP53 and UBA52 with PSI of splicing events

(a) TP53 and splicing event TP53‐39035‐AT, (b) UBA52 and splicing event UBA52‐48475‐ES, (c) UBA52 and splicing event UBA52‐48479‐ES

Fig 6.

K‐M curves analyses of PI of splicing events of core genes TP53 and UBA52. Samples were divided into high risk (red) and low risk (blue) groups based on the median P‐value

(a) TP53‐39035‐AT, (b) UBA52‐48475‐ES

Fig 7.

GO analyses of SASE related genes that link to survival in cervical cancer and KEGG functional enrichment analyses

(a) GO analyses of SASE related genes that link to survival in cervical cancer, (b) KEGG functional enrichment analyses for survival‐related pathways in cervical cancer. GO, gene ontology; CC, cellular component; MF, molecular function; BP, biological process; KEGG, Kyoto encyclopaedia of genes and genomes

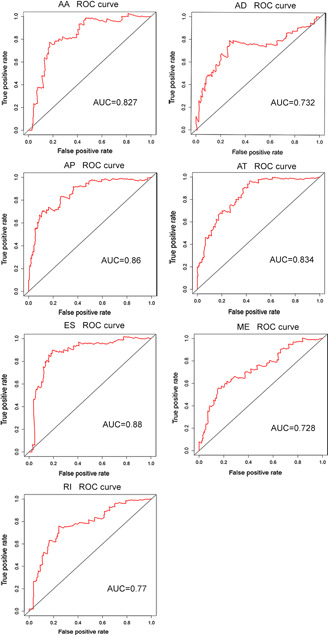

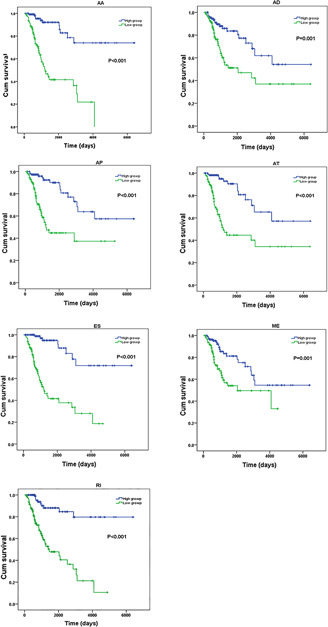

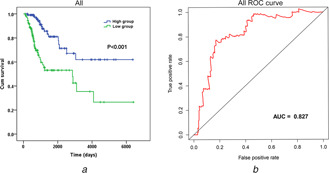

3.3 Prognostic splicing events for CESC

The top 20 splicing events in each type were chosen for multivariate Cox regression analysis (including clinical parameters such as age, stage, grade etc.). After ruling out the influences of dependent factors (except survival time) on the prognosis of cervical cancer, we included PI of splicing events and cancer status with P <0.01 (Table 1 ). High risk and low‐risk groups were then categorised according to the median value of PI. ROC curves showed that the AUC value of these seven events fluctuated between 0.728 and 0.880 (Fig. 8 ). By K‐M curves analyses, it was observed that low‐risk group had a remarkably longer survival period than did high‐risk group (P <0.05) in the seven types of splicing events in cervical cancer (Fig. 9 ). The comprehensive ROC and K‐M analyses of the top 20 events in each type also showed that the survival time was noticeably longer in a low‐risk group than in a high‐risk group, and the AUC value was 0.827, indicating that the prognostic model constructed by alternative splicing events in the current study is highly valuable in the diagnosis and prognosis of cervical cancer (Fig. 10 ).

Table 1.

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses of the top 20 splicing events in each slicing type

| Parameter | Univariate | Multivariate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | P | HR | P | |

| PI | 3.472 (1.958–6.157) | <0.001 | 4.429 (2.169–9.046) | <0.001 |

| age (<60 versus ≥60 years) | 1.292 (0.705–2.369) | 0.408 | 0.510 (0.234–1.111) | 0.090 |

| stage (I + II versus III + IV) | 1.808 (0.999–3.270) | 0.050 | 1.653 (0.769–3.551) | 0.198 |

| grade (1 + 2 versus 3 + 4) | 1.000 (0.558–1.791) | 1.000 | 0.749 (0.397–1.412) | 0.372 |

| cancer status (tumour free versus with tumour) | 26.476 (12.598–55.640) | <0.001 | 38.979 (15.769–96.349) | <0.001 |

(PI: prognostic index; HR: hazard ratio).

Fig 8.

ROC curves of the PI of the top 20 splicing events in seven types of splicing. AA, alternate acceptor site; AD, alternate donor site; AP, alternate promoter; AT, alternate terminator; ES, exon skip; ME, mutually exclusive exons; RI, retained intron. AUC, area under curve

Fig 9.

K‐M curves of the PI of the top 20 splicing events in seven types of splicing. AA, alternate acceptor site; AD, alternate donor site; AP, alternate promoter; AT, alternate terminator; ES, exon skip; ME, mutually exclusive exons; RI, retained intron. Blue curve, high‐risk group; green curve, low‐risk group

Fig 10.

K‐M and ROC analyses of the PI of the top 20 splicing events in seven types of splicing

(a) K‐M curves analysis, (b) ROC curves analysis. Blue curve, low‐risk group; green curve, high‐risk group. AUC, area under curve

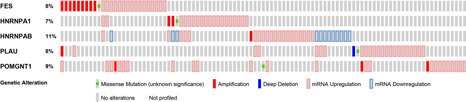

3.4 mRNA expression and mutant status of genes with alternative splicing events and prognostic potential in cervical cancer

Five genes, i.e. FES, HNRNAP1, HNRNPAB, PLAU and POMGNT1 were found to have prognostic potential upon multivariate Cox regression analyses for whom with most common (top 20) splicing events in each type, among which, HNRNPAB and PLAU upregulated, FES downregulated, while HNRNPA1 and POMGNT1 had no change in mRNA level in cervical cancers as compared with normal tissues, respectively (Fig. 11 ). With respect to mutation, HNRNPAB had the highest mutant frequency at 11%, followed by POMGNT1 (9%), FES and PLAU (both 8%), and HNRNPA1 (7%). The major outcome of these mutations is associated with an upregulation of mRNA (Fig. 12 ).

Fig 11.

Comparison of the mRNA level of five core genes related to the top 20 splicing events in each type between cervical cancer (red) and normal tissues (grey). The five genes are determined by multivariate Cox regression analysis. FES gene, HNRNAP1 gene, HNRNPAB gene, PLAU gene, POMGNT1 gene. *P<0.05

Fig 12.

Gene mutation status of the five splicing factors with prognostic significance filtrated by multivariate regression analyses. The mutation figures are obtained from cBioportal for cancer genomics dataset

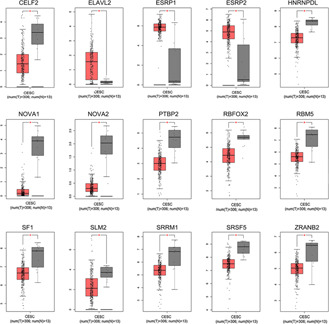

3.5 Correlation between splicing factors and splicing events in cervical cancer

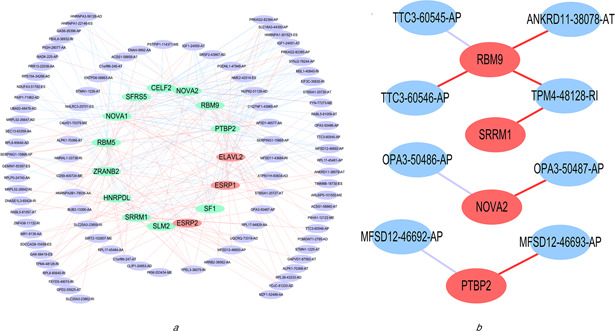

Upon analysing the mRNA expression of 64 splicing factors in cervical cancer versus normal tissues, the mRNA levels of 15 splicing factors, i.e. GELF2, ELAVL2, ESRP1, ESRP2, HNRNPDL, NOVA1, NOVA2, PTBP2, RBFOX2, RBM5, SF1, SLM2, SRRM1, SRSF5 and ZRANB25 were found to be expressed differentially in cervical cancers versus control tissues (P <0.05 for all) (Fig. 13 ). These 15 splicing factors were subsequently used to construct the association with SASEs identified by multivariate Cox regression analysis, unveiling that RBM9, SRRM1, NOVA2 and PTBP2 had a higher correlation coefficient absolute value (above 0.4). Of these, RBM9 was negatively related with splicing event TTC3‐60545‐AP, while positively correlated events ANKRD11‐38078‐AT, TTC3‐60546‐AP, and TPM4‐48128‐RI; SRRM1 was positively associated with event TPM4‐48128‐RI. NOVA2 had negative relationships with DPA3‐50486‐AP, but had positive associations with OPA3‐50487‐AP; PTBP2 was negatively with MFSD12‐46692‐AP, whereas positively linked MFSD12‐46693‐AP (Fig. 14 ). These data demonstrate that cervical cancer presents splicing factors that relate to survival time, which may emerge as promising prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for this female common pathology.

Fig 13.

Comparison of mRNA of 15 differentially expressed splicing factors in cervical cancer (red) versus normal tissues (grey) chosen by GEPIA. *P <0.05

Fig 14.

Correlation network among the 15 differentially expressed splicing factors and PSI of prognostic splicing events and the correlation network of splicing factors with r >0.4 and related splicing events

(a) Network is drawn with Cytoscape. Red dots, highly‐expressed factors in cervical cancer; green dots, lowly‐expressed factors in cervical cancer; purple dots: splicing events; red lines: positive relationships; blue lines: negative relationships, (b) Red dots, splicing factors with |r |>0.4 by Pearson correlation analysis; blue dots, splicing events; red lines: positive relationships; purple, negative relationship

4 Discussion

Globally, cervical cancer has emerged as a major cause for female death, being the second highest mortality rate for women [1 ]. Over the past decade, the morbidity rate of cervical cancer has been rising and the age of onset tends to be younger, with a worsen prognosis and a higher recurrence rate [26, 27 ]. To improve this situation, many efforts have been done, and alternative splicing events appear to be a valuable prognostic indicator. However, very few existing studies concentrated on the correlations between alternative splicing events and cervical cancer. In the advance of high‐throughput sequencing technology, more and more reliable molecular biomarkers were identified. Tumour cells always do all they can to build growth advantages, and the splicing process that has a strong functional impact to regulate the biological process. For example, in many types of cancer, exon 14 splicing alteration could result in activation of MET and identify patients who likely sensitivity to MET inhibitors [28, 29 ]. Liu et al. examined the alternative splicing events associated with the pathogenesis of cervical cancer, but they solely explored one event of splicing factor SRSF10 [30 ]. Herein, we calculated the PI concerning all the relevant alternative splicing events in cervical cancer, and comprehensively analysed the splicing factors and events that had prognostic value.

Over the past decade, TCGA dataset provides cancer researchers with abundant resources for the investigation of multi‐omics molecular data, including the genome splicing events. Here, we extended the methodology of SpliceSeq and calculated the prognostic value of each potential splicing event in CESC. The algorithm we utilised could facilitate the identification of the reliable and novel molecular events and provide novel insights into the role of splicing events in CESC. In alternative splicing events, splicing factor remained a key element, which recognises featured splicing site on mRNA, removes introns at the boundary between exons and introns, enabling the neighbouring introns to connect where the alternative splicing event took place [31 ]. Recently, several researches have elucidated the possible relationships of alternative splicing factors with cell migration, growth regulation, and apoptosis in cancers. In this study, the mRNA expression of certain splicing factors seemed to link prognostic splicing events, and particularly, RBM9, SRRM1, NOVA2 and PTBP2 showed close associations with SASEs (|r |>0.4) (Fig. 14 ). RBM19, also referred to as Rbfox2, belongs to Rbfox family, which is in close association with the cell cycle in retinoblastoma and is deemed as a specific splicing factor modulating the mesenchyme in normal and tumour tissues [32 –34 ]. SRRM1 encodes serine/arginine repetitive matrix protein in human, abnormal splicing of which has linked to the onset and therapeutic effect of certain cancers [35, 36 ]. NOVA2 is a splicing factor to regulate the polarity of endothelial cells and the maturity of vascular lumen [37 ], which might be upregulated in anoxia and induced colorectal cancer [38 ]. PTBP2 is an RNA polypyrimidine binding protein that plays critical role in the reproductive system; Ji et al. found that lncRNA MALAT1 could bind to SFPQ, releasing PTBP2, thus promoting the development and metastasis of colon cancer and rectal cancer [39 ]. Together RBM9, SRRM1, NOVA2 and BTBP2 had links with various cancers. Herein, we also revealed that alternative splicing events related to these genes had correlations with the survival time of patients with cervical cancer (Fig. 14 ).

After calculating the PI of all the relevant alternative splicing events in cervical cancer, and thoroughly analysed prognostically valuable splicing factors and events, we found that the AUC value of ROC curves was up to 0.88, indicating that this prognostic model works effectively in predicting the outcome of cervical cancer, helping in digging splicing genes related to cervical cancer and the relevant mechanism. After performing functional analyses for genes filtrated by univariate Cox regression tests via GO and KEGG, we found that the major pathways affecting the alternative splicing events included ribosome, NF‐κB signalling pathway, endocytosis, etc. Biosynthesis in ribosome is one of the most pleiotropic biological process, involving in the maturation and assembly of a plenty of factors which are associated with cell proliferation and cell cycle [40, 41 ]. As a tumour‐suppressing factor P53 plays a regulatory role in ribosome biogenesis and cell cycle, the upregulation of ribosome may lead to the downregulation of P53 expression and promote the malignant transformation [42 ]. NF‐κB signalling is also pleiotropic, participating in biological processes like cell proliferation, cell viability, innate immunity, inflammation, etc., and regulating the expression of hundreds of genes. It was verified that the misregulation of NF‐κB by mutation and epigenetic mechanism of multiple genes resulted in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic renal disease, gastric cancer, breast cancer, colorectal cancer, etc. [43 –50 ]. Endocytosis is an energy‐dependent active transport [51 ]. An increasing number of studies on the correlations between endocytosis and cancers suggested that endocytosis could not only mutually regulate cell signalling to control the derived signals on the surface of tumour cells, but also function independently in tumour cells to inhibit their infiltration [52, 53 ]. For example, the constant upregulation or acute activation of dynamin‐1 in cancer cells may activate adaptive clathrin CME program, altering the signal transduction to promote tumour cell survival, migration and proliferation.

Several existing researches had implicated that some traditional biological indicators like P16, CD34, COX‐2 correlated with the treatment and prognosis of cervical cancer [54 –56 ]. Moreover, certain mRNAs, such as miR‐21, miR‐200a, miR‐9 and so forth, also played an active role in the prognosis of this female disorder [57 ]. Despite these indicators identified, it remained a challenging task to apply them clinically due to their less precise sensitivity and a lack of insight into the mechanism. Basing on available literatures, we realise that the alteration of gene expression due to mutations or epigenetic factors is the key issue in the development of cervical cancer, although human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is commonly seen and is once thought to induce this malignancy [2 ]. For instance, abnormal DNA methylation and histone modification had been extensively investigated, indicating that epigenetic change influenced the coding sequence, mRNA expression, and translation efficiency of affected genes and accelerated cancer progression [58 ]. All the above‐mentioned processes could lead to alternative splicing events [59 –69 ]. The advancement of high‐throughput sequencing and TCGA have facilitated the availability of massive volumes of data, which could help confirm the correlations between alternative splicing events and various tumours. For example, Li et al. detected EGFR, CD44, AR in non‐small‐cell lung carcinoma; He et al. observed ESRP1, HNRNPA2B1, HNRNPL in transitional cell carcinoma of bladder; Lin et al. discovered POLR2L, ANAPC11, TCEBI in gastrointestinal cancer. In these studies, alternative splicing events of these genes were found closely associated with the treatment and prognosis, and these events could serve as biomarkers for prognosis [70 ]. We also observed the significance of TP53 and UBA52 in the gene network (Figs. 3 and 4 ), and the Pearson correlation analysis revealed the remarkable correlation between mRNA expression and splicing events with survival significance (Fig. 5 ). As known, TP53 in a crucial tumour‐inhibiting gene in eukaryotes, which also known as ‘the guardian of the genome’. Besides utilised in ultra‐early diagnosis of tumours, TP53 could be applied as prognostic indicator in monitoring cancer recurrence after operation [71 –73 ]. In 1978, Gilbert proposed that one gene could bind to different splicing sites and generate various mRNA; therefore, various proteins were produced, even one gene could produce proteins that functioned completely differently [74 ]. It was confirmed by other research that TP53 had contrary functions in alternative splicing – producing various TP53 subtypes that either inhibited or promoted tumour development and progression. Take breast cancer as an instance, the alternative variants at the C terminus of TP53 gene yielded an abnormal TP53 that speed up the tumour development and result in shorter survival period [75 ]. While under other circumstances, subtypes like P53α and P53γ retained tumour‐suppressing property, hence being able to accelerate the apoptosis and inhibit tumour development, exerting positive influences on the treatment and prognosis. With respect to UBA52, it remains an important factor in regulating the ubiquitination of ribosome and ribosomal proteins and in cell growth, alterations of which thus influence cell cycle [76, 77 ]. In our research, the alternative splicing events of TP53 and UBA52 were found to correlate with the survival time of patients with cervical cancer, indicating that they had the potential to act as biomarkers for prognosis of cervical cancer. In sum, it could be inferred that the splicing factors in cervical cancer could interfere in a variety of biological functions via major splicing events and affect the survivorship of the patients.

5 Conclusion

In the current investigation, a prognostic model for cervical cancer was constructed with PSI, PI, K‐M and ROC curves. As a result, multiple alternative splicing events have been implicated in the progression and several genes can serve as prognostic indicators for cervical cancer, making them appealing targets for treatment. However, further confirmation experiments are needed to clarify these finding because this study is only based on bioinformatics.

6 Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the National Cancer Institute for access to TCGA and TCGA SpliceSeq databases and their valuable data. Hua‐yu Wu and Qi‐qi Li contributed equally to this work and should be considered co‐first authors. This work was financially supported by the National Nature Science.

The study was supported by the Innovation Project of Guangxi Graduate Education (YCSW2019104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant nos. 81660241, 81360066, 31760319). The external funders had no role in the study design, data collection or analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

7 References

- 1. Bray F. Ferlay J. Soerjomataram I. et al.: ‘Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries ’, CA Cancer J. Clin., 2018, 68, (6 ), pp. 394 –424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fang J. Zhang H. Jin S.: ‘Epigenetics and cervical cancer: from pathogenesis to therapy ’, Tumour Biol.: J. Int. Soc. Oncodevelop. Biol. Med., 2014, 35, (6 ), pp. 5083 –5093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tsikouras P. Zervoudis S. Manav B. et al.: ‘Cervical cancer: screening, diagnosis and staging ’, J. BUON: Off. J. Balkan Union Oncol., 2016, 21, (2 ), pp. 320 –325 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Song X. Han Y. Shao Y. et al.: ‘Assessment of local treatment modalities for FIGO stage IB‐IIB cervical cancer: a propensity‐score matched analysis based on SEER database ’, Sci. Rep., 2017, 7, (1 ), p. 3175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hong J.‐H. Tsai C.‐S. Lai C.‐H. et al.: ‘Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of cervix after definitive radiotherapy ’, Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys., 2004, 60, (1 ), pp. 249 –257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bush S.J. Chen L. Tovar‐Corona J.M. et al.: ‘Alternative splicing and the evolution of phenotypic novelty ’, Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B, Biol. Sci., 2017, 372, (1713 ), p. 20150474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. He X. Yuan C. Yang J.: ‘Regulation and functional significance of CDC42 alternative splicing in ovarian cancer ’, Oncotarget, 2015, 6, (30 ), pp. 29651 –29663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Oltean S. Bates D.O.: ‘Hallmarks of alternative splicing in cancer ’, Oncogene, 2014, 33, (46 ), pp. 5311 –5318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wang E.T. Sandberg R. Luo S. et al.: ‘Alternative isoform regulation in human tissue transcriptomes ’, Nature, 2008, 456, (7221 ), pp. 470 –476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pan Q. Shai O. Lee L.J. et al.: ‘Deep surveying of alternative splicing complexity in the human transcriptome by high‐throughput sequencing ’, Nature Genet., 2008, 40, (12 ), pp. 1413 –1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Häsler R. Sheibani‐Tezerji R. Sinha A. et al.: ‘Uncoupling of mucosal gene regulation, mRNA splicing and adherent microbiota signatures in inflammatory bowel disease ’, Gut, 2017, 66, (12 ), pp. 2087 –2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Grond‐Ginsbach C. Chen B. Krawczak M. et al.: ‘Genetic imbalance in patients with cervical artery dissection ’, Curr. Genomics, 2017, 18, (2 ), pp. 206 –213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cooper D.N. Krawczak M. Polychronakos C. et al.: ‘Where genotype is not predictive of phenotype: towards an understanding of the molecular basis of reduced penetrance in human inherited disease ’, Hum. Genet., 2013, 132, (10 ), pp. 1077 –1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lagunes T. Herrera‐Rivero M. Hernández‐Aguilar M.E. et al.: ‘A beta(1–42) induces abnormal alternative splicing of tau exons 2/3 in NGF‐induced PC12 cells ’, An. Acad. Bras. Cienc., 2014, 86, (4 ), pp. 1927 –1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dlamini Z. Tshidino S.C. Hull R.: ‘Abnormalities in alternative splicing of apoptotic genes and cardiovascular diseases ’, Int. J. Mol. Sci., 2015, 16, (11 ), pp. 27171 –27190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lawes D.A. Pearson T. Sengupta S. et al.: ‘The role of MLH1, MSH2 and MSH6 in the development of multiple colorectal cancers ’, Br. J. Cancer, 2005, 93, (4 ), pp. 472 –477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zhu J. Chen Z. Yong L.: ‘Systematic profiling of alternative splicing signature reveals prognostic predictor for ovarian cancer ’, Gynecol. Oncol., 2018, 148, (2 ), pp. 368 –374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kornblihtt A.R.: ‘Epigenetics at the base of alternative splicing changes that promote colorectal cancer ’, J. Clin. Investig., 2017, 127, (9 ), pp. 3281 –3283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Casado F.L.: ‘The aryl hydrocarbon receptor relays metabolic signals to promote cellular regeneration ’, Stem Cells Int., 2016, 2016, p. 4389802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. He R.‐Q. Zhou X.‐G. Yi Q.‐Y. et al.: ‘Prognostic signature of alternative splicing events in bladder urothelial carcinoma based on spliceseq data from 317 cases ’, Cell. Physiol. Biochem.: Int. J. Exp. Cell. Physiol., Biochem. Pharmacol., 2018, 48, (3 ), pp. 1355 –1368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sveen A. Kilpinen S. Ruusulehto A. et al.: ‘Aberrant RNA splicing in cancer; expression changes and driver mutations of splicing factor genes ’, Oncogene, 2016, 35, (19 ), pp. 2413 –2427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Song X. Zeng Z. Wei H. et al.: ‘Alternative splicing in cancers: from aberrant regulation to new therapeutics ’, Seminars Cell Dev. Biol., 2018, 75, pp. 13 –22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Climente‐González H. Porta‐Pardo E. Godzik A. et al.: ‘The functional impact of alternative splicing in cancer ’, Cell. Rep., 2017, 20, (9 ), pp. 2215 –2226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zong Z. Li H. Yi C. et al.: ‘Genome‐wide profiling of prognostic alternative splicing signature in colorectal cancer ’, Front. Oncol., 2018, 8, p. 537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin P. He R.Q. Huang Z.G. et al.: ‘Role of global aberrant alternative splicing events in papillary thyroid cancer prognosis ’, Aging (Albany NY), 2019, 11, (7 ), pp. 2082 –2097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Bhat S. Kabekkodu S.P. Noronha A. et al.: ‘Biological implications and therapeutic significance of DNA methylation regulated genes in cervical cancer ’, Biochimie, 2016, 121, pp. 298 –311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kontostathi G. Zoidakis J. Anagnou N.P. et al.: ‘Proteomics approaches in cervical cancer: focus on the discovery of biomarkers for diagnosis and drug treatment monitoring ’, Expert Rev. Proteomics, 2016, 13, (8 ), pp. 731 –745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kahles A. Lehmann K.V. Toussaint N.C. et al.: ‘Comprehensive analysis of alternative splicing across tumors from 8,705 patients ’, Cancer Cell, 2018, 34, (2 ), pp. 211 –224 e216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Frampton G.M. Ali S.M. Rosenzweig M. et al.: ‘Activation of met via diverse exon 14 splicing alterations occurs in multiple tumor types and confers clinical sensitivity to met inhibitors ’, Cancer Discov., 2015, 5, (8 ), pp. 850 –859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Liu F. Dai M. Xu Q. et al.: ‘SRSF10‐mediated IL1RAP alternative splicing regulates cervical cancer oncogenesis via mIL1RAP‐NF‐κB‐CD47 axis ’, Oncogene, 2018, 37, (18 ), pp. 2394 –2409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shen S. Wang Y. Wang C. et al.: ‘SURVIV for survival analysis of mRNA isoform variation ’, Nat. Commun., 2016, 7, p. 11548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Park C. Choi S. Kim Y.‐E. et al.: ‘Stress granules contain Rbfox2 with cell cycle‐related mRNAs ’, Sci. Rep., 2017, 7, (1 ), p. 11211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Venables J.P. Brosseau J.‐P. Gadea G. et al.: ‘RBFOX2 is an important regulator of mesenchymal tissue‐specific splicing in both normal and cancer tissues ’, Mol. Cell. Biol., 2013, 33, (2 ), pp. 396 –405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Arya A.D. Wilson D.I. Baralle D. et al.: ‘RBFOX2 protein domains and cellular activities ’, Biochem. Soc. Trans., 2014, 42, (4 ), pp. 1180 –1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sun L. Hu J. Xiong W. et al.: ‘MicroRNA expression profiles of circulating microvesicles in hepatocellular carcinoma ’, Acta Gastroenterol. Belg., 2013, 76, (4 ), pp. 386 –392 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Thurman M. van Doorn J. Danzer B. et al.: ‘Changes in alternative splicing as pharmacodynamic markers for sudemycin D6 ’, Biomark. Insights, 2017, 12, p. 1177271917730557 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Giampietro C. Deflorian G. Gallo S. et al.: ‘The alternative splicing factor Nova2 regulates vascular development and lumen formation ’, Nat. Commun., 2015, 6, p. 8479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Gallo S. Arcidiacono M.V. Tisato V. et al.: ‘Upregulation of the alternative splicing factor NOVA2 in colorectal cancer vasculature ’, Onco. Targets Ther., 2018, 11, pp. 6049 –6056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ji Q. Zhang L. Liu X. et al.: ‘Long non‐coding RNA MALAT1 promotes tumour growth and metastasis in colorectal cancer through binding to SFPQ and releasing oncogene PTBP2 from SFPQ/PTBP2 complex ’, Br. J. Cancer, 2014, 111, (4 ), pp. 736 –748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pelletier J. Thomas G. Volarević S.: ‘Ribosome biogenesis in cancer: new players and therapeutic avenues ’, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2018, 18, (1 ), pp. 51 –63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Pelletier J. Thomas G. Volarević S.: ‘Corrigendum: ribosome biogenesis in cancer: new players and therapeutic avenues ’, Nat. Rev. Cancer, 2018, 18, (2 ), p. 134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Derenzini M. Montanaro L. Trerè D.: ‘Ribosome biogenesis and cancer ’, Acta Histochem., 2017, 119, (3 ), pp. 190 –197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Courtois G. Gilmore T.D.: ‘Mutations in the NF‐kappab signaling pathway: implications for human disease ’, Oncogene, 2006, 25, (51 ), pp. 6831 –6843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sokolova O. Sokolova O. Naumann M.: ‘NF‐κB signaling in gastric cancer ’, Toxins (Basel), 2017, 9, (4 ), p. E119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Capece D. Verzella D. Tessitore A. et al.: ‘Cancer secretome and inflammation: the bright and the dark sides of NF‐κB ’, Semin. Cell Dev. Biol., 2018, 78, pp. 51 –61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Gupta S. Bi R. Kim C. et al.: ‘Role of NF‐kappab signaling pathway in increased tumor necrosis factor‐alpha‐induced apoptosis of lymphocytes in aged humans ’, Cell Death Differ., 2005, 12, (2 ), pp. 177 –183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Jost P.J. Ruland J.: ‘Aberrant NF‐kappab signaling in lymphoma: mechanisms, consequences, and therapeutic implications ’, Blood, 2007, 109, (7 ), pp. 2700 –2707 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Patel M. Horgan P.G. McMillan D.C. et al.: ‘NF‐κB pathways in the development and progression of colorectal cancer ’, Transl. Res.: J. Lab. Clin. Med., 2018, 197, pp. 43 –56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schuliga M.: ‘NF‐kappaB signaling in chronic inflammatory airway disease ’, Biomolecules, 2015, 5, (3 ), pp. 1266 –1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Gunes G. Dogruer Unal N. Eskandari G. et al.: ‘Determination of NF‐kappab and RANKL levels in peripheral blood osteoclast precursor cells in chronic kidney disease patients ’, Int. Urol. Nephrol., 2018, 50, (6 ), pp. 1181 –1188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen K. Li X. Zhu H. et al.: ‘Endocytosis of nanoscale systems for cancer treatments ’, Curr. Med. Chem., 2018, 25, (25 ), pp. 3017 –3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Schmid S.L.: ‘Reciprocal regulation of signaling and endocytosis: implications for the evolving cancer cell ’, J. Cell Biol., 2017, 216, (9 ), pp. 2623 –2632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Holst M.R. Vidal‐Quadras M. Larsson E. et al.: ‘Clathrin‐independent endocytosis suppresses cancer cell blebbing and invasion ’, Cell. Rep., 2017, 20, (8 ), pp. 1893 –1905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Doll C.M. Winter K. Gaffney D.K. et al.: ‘COX‐2 expression and survival in patients with locally advanced cervical cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy and celecoxib: a quantitative immunohistochemical analysis of RTOG C0128 ’, Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer: Off. J. Int. Gynecol. Cancer Soc., 2013, 23, (1 ), pp. 176 –183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Vieira S.C. Silva B.B. Pinto G.A. et al.: ‘CD34 as a marker for evaluating angiogenesis in cervical cancer ’, Pathol. Res. Pract., 2005, 201, (4 ), pp. 313 –318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Ahmad A. Raish M. Shahid M. et al.: ‘The synergic effect of HPV infection and epigenetic anomaly of the p16 gene in the development of cervical cancer ’, Cancer Biomarkers: Section A Dis. Markers, 2017, 19, (4 ), pp. 375 –381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Gómez‐Gómez Y. Organista‐Nava J. Organista‐Nava J. et al.: ‘Deregulation of the miRNAs expression in cervical cancer: human papillomavirus implications ’, BioMed Res. Int., 2013, 2013, p. 407052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Salton M. Misteli T.: ‘Small molecule modulators of Pre‐mRNA splicing in cancer therapy ’, Trends Mol. Med., 2016, 22, (1 ), pp. 28 –37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Supek F. Miñana B. Valcárcel J. et al.: ‘Synonymous mutations frequently act as driver mutations in human cancers ’, Cell, 2014, 156, (6 ), pp. 1324 –1335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sterne‐Weiler T. Sanford J.R.: ‘Exon identity crisis: disease‐causing mutations that disrupt the splicing code ’, Genome Biol., 2014, 15, (1 ), p. 201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Diederichs S. Bartsch L. Berkmann J.C. et al.: ‘The dark matter of the cancer genome: aberrations in regulatory elements, untranslated regions, splice sites, non‐coding RNA and synonymous mutations ’, EMBO Mol. Med., 2016, 8, (5 ), pp. 442 –457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Jung H. Lee D. Lee J. et al.: ‘Intron retention is a widespread mechanism of tumor‐suppressor inactivation ’, Nat. Genet., 2015, 47, (11 ), pp. 1242 –1248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Singh S. Narayanan S.P. Biswas K. et al.: ‘Intragenic DNA methylation and BORIS‐mediated cancer‐specific splicing contribute to the Warburg effect ’, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2017, 114, (43 ), pp. 11440 –11445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gelfman S. Cohen N. Yearim A. et al.: ‘DNA‐methylation effect on cotranscriptional splicing is dependent on GC architecture of the exon‐intron structure ’, Genome Res., 2013, 23, (5 ), pp. 789 –799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Shukla S. Kavak E. Gregory M. et al.: ‘CTCF‐promoted RNA polymerase II pausing links DNA methylation to splicing ’, Nature, 2011, 479, (7371 ), pp. 74 –79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yuan H. Li N. Fu D. et al.: ‘Histone methyltransferase SETD2 modulates alternative splicing to inhibit intestinal tumorigenesis ’, J. Clin. Investig., 2017, 127, (9 ), pp. 3375 –3391 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Ding X. Liu S. Tian M. et al.: ‘Activity‐induced histone modifications govern neurexin‐1 mRNA splicing and memory preservation ’, Nat. Neurosci., 2017, 20, (5 ), pp. 690 –699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Sharma A. Nguyen H. Geng C. et al.: ‘Calcium‐mediated histone modifications regulate alternative splicing in cardiomyocytes ’, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2014, 111, (46 ), p. E4920‐8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kim S. Kim H. Fong N. et al.: ‘Pre‐mRNA splicing is a determinant of histone H3K36 methylation ’, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 2011, 108, (33 ), pp. 13564 –13569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Lin P. He R.‐Q. Ma F.‐C. et al.: ‘Systematic analysis of survival‐associated alternative splicing signatures in gastrointestinal pan‐adenocarcinomas ’, EBioMedicine, 2018, 34, pp. 46 –60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Leroy B. Anderson M. Soussi T.: ‘TP53 mutations in human cancer: database reassessment and prospects for the next decade ’, Hum. Mutat., 2014, 35, (6 ), pp. 672 –688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Terada K. Yamaguchi H. Ueki T. et al.: ‘Full‐length mutation search of the TP53 gene in acute myeloid leukemia has increased significance as a prognostic factor ’, Ann. Hematol., 2018, 97, (1 ), pp. 51 –61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Köbel M. Piskorz A.M. Lee S. et al.: ‘Optimized p53 immunohistochemistry is an accurate predictor of TP53 mutation in ovarian carcinoma ’, J. Pathol. Clin. Res., 2016, 2, (4 ), pp. 247 –258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Gilbert W.: ‘Why genes in pieces? ’, Nature, 1978, 271, (5645 ), p. 501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Sadighi S. Zokaasadi M. Kasaeian A. et al.: ‘The effect of immunohistochemically detected p53 accumulation in prognosis of breast cancer; a retrospective survey of outcome ’, PloS one, 2017, 12, (8), p. e0182444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Kobayashi M. Oshima S. Maeyashiki C. et al.: ‘The ubiquitin hybrid gene UBA52 regulates ubiquitination of ribosome and sustains embryonic development ’, Sci. Rep., 2016, 6, p. 36780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mao J. O'Gorman C. Sutovsky M. et al.: ‘Ubiquitin A‐52 residue ribosomal protein fusion product 1 (Uba52) is essential for preimplantation embryo development ’, Biol. Open, 2018, 7, (10 ), p. bio.035717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]