Abstract

The Raf-1 serine/threonine protein kinase requires phosphorylation of the serine at position 338 (S338) for activation. Ras is required to recruit Raf-1 to the plasma membrane, which is where S338 phosphorylation occurs. The recent suggestion that Pak3 could stimulate Raf-1 activity by directly phosphorylating S338 through a Ras/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Pl3-K)/-Cdc42-dependent pathway has attracted much attention. Using a phospho-specific antibody to S338, we have reexamined this model. Using LY294002 and wortmannin, inhibitors of Pl3-K, we find that growth factor-mediated S338 phosphorylation still occurs, even when Pl3-K activity is completely blocked. Although high concentrations of LY294002 and wortmannin did suppress S338 phosphorylation, they also suppressed Ras activation. Additionally, we show that Pak3 is not activated under conditions where S338 is phosphorylated, but when Pak3 is strongly activated, by coexpression with V12Cdc42 or by mutations that make it independent of Cdc42, it did stimulate S338 phosphorylation. However, this occurred in the cytosol and did not stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity. The inability of Pak3 to activate Raf-1 was not due to an inability to stimulate phosphorylation of the tyrosine at position 341 but may be due to its inability to recruit Raf-1 to the plasma membrane. Taken together, our data show that growth factor-stimulated Raf-1 activity is independent of Pl3-K activity and argue against Pak3 being a physiological mediator of S338 phosphorylation in growth factor-stimulated cells.

The Raf-1 serine/threonine-specific protein kinase is the first component of a three-tiered protein kinase cascade that regulates many biological events such as cell growth, differentiation, and apoptosis (for reviews, see references 12, 39, and 44). Raf-1 phosphorylates and activates the dual-specificity mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinases MEK1 and MEK2, which in turn activate the MAPKs ERK1 and ERK2. The ERKs phosphorylate and regulate the activity of transcription factors, cytoskeletal proteins, metabolic enzymes, and other protein kinases to modulate cellular responses to extracellular signals. Raf-1 regulation is highly complex. It is cytosolic in unstimulated cells, but following activation of the small G-protein Ras, it translocates to the plasma membrane, where activation takes place (for reviews, see references 23, 38, and 41). Interaction with Ras alone is not sufficient to activate Raf-1 and other membrane-localized events such as oligomerization, interaction with other proteins, and interactions with lipids all appear to play a role.

Phosphorylation also plays a key role in Raf-1 activation, and both positive and negative regulatory sites have been mapped (23, 38, 41). Two sites whose phosphorylation has been shown to be necessary for activation are the serine located at position 338 (S338) and the tyrosine located at position 341 (Y341) (3, 15, 18, 36, 40, 42). These amino acids are located 10 to 15 amino acids N terminal to the glycine-rich loop of the ATP-binding domain, a region that we call the negative charge regulatory region (40). S338 phosphorylation is stimulated under conditions that lead to Raf-1 activation, and when this amino acid is substituted for alanine, Raf-1 cannot be activated (3, 15, 40). The kinase that phosphorylates S338 resides at the plasma membrane, and its activity appears to be stimulated, at least under some conditions (40). However, using oncogenic Ras and activated Src to stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity, we have shown that whereas oncogenic Ras induced stronger S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1, activated Src stimulated more kinase activity (40). Thus, although S338 phosphorylation is required for Raf-1 activation, the levels of phosphorylation do not correlate with kinase activity, and so S338 phosphorylation cannot be used as a surrogate marker of Raf-1 activation.

Originally, Ras was thought to form part of a linear signaling cascade, linking receptor tyrosine kinase activation to the activation of the ERKs. However, it is now clear that Ras also regulates the activity of a number of other signaling pathways through activation of proteins such as phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Pl3-K) and RalGDS (4, 55). There is much interest in the cross talk that exists between these different, parallel Ras pathways, and in some but not all cell types, inhibition of Pl3-K that leads to suppression of ERK has been shown (8, 16, 24, 56). In different studies, Pl3-K has been shown to regulate ERK activation at the level of Ras or at the level of Raf-1 (7, 8, 27, 56). More recently, it was suggested that Pl3-K regulates Raf-1 by activating protein kinases that can phosphorylate Raf-1 directly. For example, when the protein kinase Akt (also called protein kinase B) is activated by Pl3-K, it can phosphorylate Raf-1 on serine 259 and thus suppress its activity (46, 58); a similar mechanism may regulate B-Raf (22).

Recently, it was also proposed that Pl3-K-dependent activation of Raf-1 occurs through the activation of Pak3 and subsequent phosphorylation of Raf-1 on S338 (26, 49). Pak1, -2, and -3 are cytosolic serine/threonine-specific protein kinases that are activated by direct binding to the small G proteins Cdc42 and Rac (for reviews, see references 2, 9, and 28). Like Raf-1 activation, Pak activation is highly complex and may involve membrane recruitment, phosphorylation, dimerization, and interaction with lipids and other proteins (2, 6, 9, 28, 31, 34). Paks are implicated in a number of biological processes, such as cytoskeletal reorganization, cell cycle progression, and apoptosis (2, 9).

Increasing evidence suggests that the Paks can also regulate the ERKs. Membrane-targeted Pak or overexpressed wild-type Pak induces ERK activation in 293T cells (32), and T-cell receptor-mediated ERK activation may be Pak dependent (57). Activated Cdc42, Rac, and Pak synergize with Raf-1 to stimulate MEK1 and ERK (21), and kinase-inactive Pak mutants inhibit Ras-induced transformation of Rat-1 fibroblasts and Schwann cells but not NIH 3T3 cells (50, 51). The mechanism by which Paks regulate ERK activity is not known but in some cells may involve direct phosphorylation of MEKs by Pak1 (21). Thus, the suggestion that Pak3 could directly activate Raf-1 by S338 phosphorylation has generated much interest. In those studies, it was shown that activated Pak3 could stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity in vivo and that kinase-defective Pak3 could suppress Raf-1 activation (25). Pl3-K inhibitors were shown to block growth factor-stimulated S338 phosphorylation and suppress Raf-1 activation (49). Based on these studies, a model was proposed in which Ras recruits Raf-1 to the plasma membrane and also activates Pl3-K. Pl3-K then activates Cdc42 and Rac, which activate Pak3, leading to Raf-1 activation through S338 phosphoryaltion (49).

However, our preliminary data did not agree with this model, and so we have reexamined the data in detail. We show that the Pl3-K inhibitors LY294002 and wortmannin do not suppress S338 phosphorylation at concentrations that block Pl3-K activity. At higher concentrations, S338 phosphorylation was suppressed, but so was Ras activation. We also show that Pak3 activation does not correlate with S338 phosphorylation, that activated mutants of Pak3 could induce S338 phosphorylation but not Raf-1 activity, and that phosphorylation occurred in the cytosol and not at the plasma membrane. Taken together, our data argue against a physiological role for Pl3-K and Pak3 in mediating S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Expression vectors.

All cloning steps were performed by standard techniques (47). Vector sequences were verified by automated dideoxy sequencing procedures. The cDNAs to create pEFmRaf-1, pEFm89LRaf-1, pEFm340DRaf-1, pEFm341DRaf-1, and pEFm340/341DRaf-1 were cloned into the expression vector pEFm/Plink.6 (R. Marais, unpublished data), a derivative of pEFPlink.2 (36) which uses the elongation factor 1α promoter for high levels of protein expression. This vector fuses a Myc epitope (EQKLISEEDL) that is recognized by monoclonal antibody 9E10 (17) onto the N terminus of the protein of interest. The expression constructs pEFV12Ras, pEFN17Ras, and pEFF527Src have been described elsewhere (36). The cDNAs for the activated versions of Cdc42 (V12Cdc42) and Rac (V12Rac) and the dominant negative versions of Cdc42 (N17Cdc42) and Rac (N17Rac) were cloned into the expression vector pEXV incorporating an N-terminal Myc epitope tag. The constructs for the hemagglutinin epitope (HA)-tagged pJ3H-HAPak3 (HA-Pak3), pJ3H-HAPak3 kinase defective (HA-Pak3kd), and pJ3H-HAPak3 constitutively active (HA-Pak3ca) were previously described (25, 49) and were kindly provided by R. Cerione.

Cell culture and biochemical techniques.

COS cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum. Transfection studies were performed using LipofectAMINE (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies), and cell extracts were prepared as previously described (36, 37). Raf-1 kinase assays were performed as previously described (35, 36, 40), using antibody 9E10 for transiently expressed mRaf-1 or a Raf-1 monoclonal antibody (R19120; Transduction Laboratories) for the endogenous protein. Immunoblotting procedures for Myc-tagged Raf-1, endogenous Raf-1, and Raf-1 phosphorylated on S338 were as described elsewhere (35, 36, 40). For immunoblotting of phospho-S473 of Akt (9271S; New England Biolabs), total Akt (9916; New England Biolabs), phospho-ERK (M8159; Sigma), and total ERK2 (polyclonal antiserum 122 [30]), equal amounts of extracts were analyzed by standard techniques, using the indicated antibodies. Ras activation assays were performed essentially according to the method of de Rooij and Bos (14) and are described elsewhere (35). Analyses of complexes between transiently expressed V12Ras and mRaf-1 were performed essentially as described elsewhere (35) except that immunoprecipitations were performed on 0.5 mg of cellular protein.

Pak3 kinase assay.

Cells extracts were prepared as for the Raf-1 kinase assays (see above). The relative concentrations of the HA-Pak3 proteins were determined by quantitative immunoblotting using anti-HA monoclonal antibody 12CA5 and developed with 125I-labeled protein A in conjunction with a Phosphorlmager. Equal amounts of HA-Pak3 protein were immunoprecipitated for 2 h at 4°C with ∼5 μg of mouse antibody 12CA5 immobilized on protein G-Sepharose. Immunoprecipitates were washed in 500 μl of kinase buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.2 mM EDTA, 0.3% [vol/vol] 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.1% [vol/vol] Triton X-100, 5 mM NaF, 0.2 mM Na3VO4 [pH 7.5], 1 μM microcystin LR, 0.2 mg/ml of bovine serum albumin, 100 μM ATP, 50 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP [5,000 Ci/mmol], with 0.5 mg of myelin basic protein (MBP)/ml as substrate), but without ATP or MBP and containing sequentially 1 M KCl, 0.1 M KCl, or no salt. Kinase reactions were performed by resuspending the beads in 30 μl of kinase buffer for 10 min at 30°C and terminated by addition of 20 μl of 2× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) sample buffer (29) followed by boiling the samples for 5 min. Proteins were separated on SDS–12% gels, and the results were visualized by autoradiography. The presence of HA-Pak3 in the immunoprecipitations was confirmed by immunoblotting the top of the gels with antibody 12CA5.

Membrane and cytosol fractionation techniques.

Membrane and cytosolic fractionation studies were performed essentially as described by Traverse et al. (53). Briefly (all procedures were performed at 4°C), cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, harvested in 500 μl of fractionation buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.2], 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.3 M sucrose, 5 μg of leupeptin/ml, 0.1 M benzamidine, 5 μg of pepstatin/ml 1 μM microcystin LR, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride), and homogenized in a Wheaton-Dounce handheld homogenizer. Nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation for 10 min at 3,000 × g, and the supernatant was harvested. The nuclei were resuspended in the same buffer and recentrifuged at 3,000 × g for 10 min. The two supernatants were combined, and the mitochondria removed by centrifugation at 5,000 × g for 15 min. The postmitochondrial supernatants were further centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 60 min, and the S100 supernatant (cytosol) was removed and stored at −20°C. The plasma P100 membrane-enriched pellet was washed twice in homogenization buffer containing 0.5 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 1 mM dithiothreitol, and pellets were dissolved in 100 μl of MD buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.9], 0.5% [vol/vol] NP-40, 0.1% [wt/vol] sodium deoxycholate, 0.05% [wt/vol] SDS, 20 mM N-octylglucopyranoside, 0.5 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 25 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate, 10% (vol/vol) glycerol, 0.1% [vol/vol] β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride 1 mM benzamidine, 5 μg of pepstatin/ml, 5 μg/of leupeptin/ml, 1 μM microcystin LR) and stored at −20°C. The protein concentrations of both fractions were determined by the Bradford assay (5).

RESULTS

Pl3-kinase is not required for phosphorylation of Raf-1 on S338.

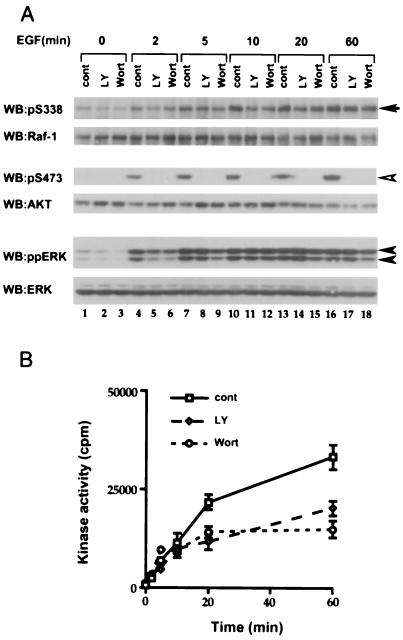

Since recent studies suggesting that Pl3-K regulates S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 were performed in epidermal growth factor (EGF)-stimulated COS cells (49), we chose these cells as a model system for our initial studies. First, we examined phosphorylation of endogenous Raf-1 protein, using a phospho-specific antibody that we recently described (40). Low levels of basal S338 phosphorylation were observed in resting cells, but within 2 min of EGF treatment, phosphorylation was elevated and continued to rise over a 60-min period (Fig. 1A, upper rows, lanes 1, 4, 7, 10, 13, and 16). To determine whether EGF also activated Pl3-K under these conditions, we used the phosphorylation of the protein kinase Akt as a rapid and convenient surrogate assay (56). Akt was not phosphorylated in resting cells, but its phosphorylation was rapidly stimulated by EGF, being detectable within 2 min and remaining elevated for up to 60 min (Fig. 1A, middle rows).

FIG. 1.

PI3-kinase inhibitors do not block S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 in COS cells. (A) Effects of PI3-kinase inhibitors on the phosphorylation of S338 on Raf-1 and of S473 on Akt and double phosphorylation of ERK1 and ERK2. COS cells were pretreated with dimethyl sulfoxide (cont), 20 μM LY294002 (LY), or 100 nM wortmannin (Wort) for 20 min and then stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. For S338 phosphorylation (upper rows, arrow), endogenous Raf-1 was immunoprecipitated with a Raf-1 monoclonal antibody and S338 phosphorylation (pS338) was detected by Western blotting (WB) using our specific antibody as described in Materials and Methods. Phosphorylations of S473 on Akt (middle rows, open arrowhead) and ERK (lower rows, closed arrowheads) were detected in the same extracts, using appropriate phospho-specific antibodies. For each pair of rows, an image of the phospho-specific blot is shown with its appropriate reprobed image with antibodies against Raf-1, Akt, and ERK. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. (B) Effects of PI3-kinase inhibitors on Raf-1 kinase activity. COS cells were treated as described above. The activity of endogenous Raf-1 was measured as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented are for one experiment assayed in triplicate, with error bars to represent standard deviations from the mean. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

We next examined whether inhibition of Pl3-K blocked S338 phosphorylation. For these studies, COS cells were pretreated with the either 20 μM LY294002 or 100 nM wortmannin (1, 54) for 20 min prior to EGF treatment. Under these conditions, S473 phosphorylation on Akt was completely blocked (Fig. 1A, middle rows). However, these inhibitors did not block EGF-stimulated S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1, although some suppression was seen (Fig. 1A, upper rows). Similar results were obtained in NIH 3T3 cells. Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) treatment of these cells induced rapid and sustained S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 and S473 phosphorylation on Akt (Fig. 2A, upper and middle rows). Pretreatment with LY294002 or wortmannin blocked S473 phosphorylation but only weakly suppressed S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 2A, upper and middle rows).

FIG. 2.

PI3-kinase inhibitors do not block S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 in NIH 3T3 cells. (A) Effects of PI3-kinase inhibitors on Raf-1, Akt, and ERK phosphorylation in NIH 3T3 cells. NIH 3T3 cells were treated as described for Fig. 1A except that they were stimulated with PDGF (50 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Phosphorylation of Raf-1 on S338 (upper row, arrow), Akt on S473 (middle row, open arrowhead), and doubly phosphorylated ERK (lower row, closed arrowheads) was tested as described for Fig. 1. To ensure equivalent protein loading, the blots were reprobed for Raf-1, Akt, and ERK after the membranes had been stripped (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. (B) Effects of PI3-kinase inhibitors on Raf-1 kinase activity. NIH 3T3 cells were treated as described above, and Raf-1 kinase activity was determined as for Fig. 1. The results presented are for one experiment assayed in triplicate, with error bars to represent standard deviations from the mean. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

We next examined Raf-1 kinase activity using an immunoprecipitation-kinase cascade assay with glutathione S-transferase (GST)–MEK, GST-ERK, and MBP as sequential substrates (35). Endogenous Raf-1 from COS cells had low activity in unstimulated cells but was rapidly activated by EGF, with weak increases being observed within 2 min and activity continuing to increase over the next 60 min (Fig. 1B). LY294002 or wortmannin pretreatment did not affect Raf-1 kinase activity for the first 10 min following treatment with EGF; thereafter kinase activity was suppressed, and at 60 min, 40 to 50% suppression was observed (Fig. 1B). In NIH-3T3 cells, PDGF stimulated two phases of Raf-1 kinase activity. A transient phase that peaked at 10 min was followed by a sustained plateau from 20 to 60 min (Fig. 2B), and pretreatment with LY294002 or wortmannin caused strong suppression of both phases of Raf-1 activity (Fig. 2B).

Intriguingly, the suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity did not translate to a comparable suppression in ERK dual phosphorylation, commonly used as a surrogate marker for ERK activation. In COS cells treated with EGF or NIH 3T3 cells treated with PDGF, ERK phosphorylation was stimulated rapidly and sustained for up to 60 min (Fig. 1A and 2A, lower rows). In COS cells, wortmannin suppressed ERK phosphorylation at 2 and 5 min, but normal phosphorylation was seen by 10 min; LY294002 suppressed ERK phosphorylation at 2 min but not at later times (Fig. 1A, lower rows). In NIH 3T3 cells, ERK phosphorylation was suppressed at 2 min by both inhibitors but was normal within 5 min (Fig. 2A, lower row).

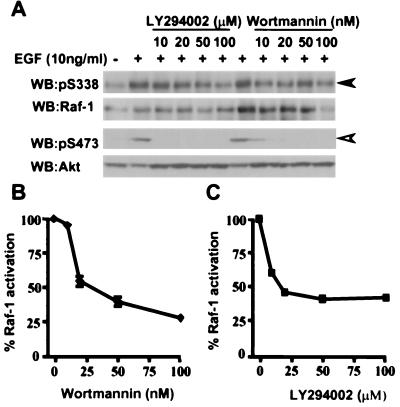

We next performed a dose-response study with wortmannin and LY294002 to compare the inhibition of PI3-K activity to the suppression of S338 phosphorylation. COS cells were pretreated with increasing concentrations of wortmannin or LY294002 and then treated with EGF for 20 min. Wortmannin exhibits greater efficacy than LY294002 in its ability to suppress Pl3-K activity. S473 phosphorylation on Akt was partially blocked by 10 nM wortmannin, and full inhibition was seen at 20 to 50 nM (Fig. 3A, lower rows), in agreement with the known sensitivity of Pl3-K to this compound (50% inhibitory concentration, ∼5 nM [1]). Intriguingly, wortmannin did suppress S338 phosphorylation but not in a dose-dependent manner, as similar levels of phosphorylation were observed at 10 and 100 nM (Fig. 3A, upper rows). The suppression of S473 phosphorylation by LY294002 was also consistent with the sensitivity of Pl3-K activity to this compound (50% inhibitory concentration, ∼1.4 μM [54]). At 10 μM LY294002, S473 phosphorylation was completely blocked (Fig. 3A, lower rows). However, S338 phosphorylation was not affected by 10 μM LY294002, and even at 100 μM, residual S338 phosphorylation was seen (Fig. 3A, upper rows).

FIG. 3.

LY294002 and wortmannin suppress S338 phosphorylation at high concentrations. (A) Effect of the concentration of PI3-K inhibitors on the phosphorylation of Raf-1 on S338 and AKT on S473. COS cells were pretreated for 20 min with dimethyl sulfoxide DMSO as vehicle control or increasing concentration of LY294002 or wortmannin for 20 min. Then cells were left untreated (−) or stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml; +) for 20 min, and S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 (upper rows, closed arrowhead) and S473 on Akt (lower rows open arrowhead) were detected as for Fig 1. For each pair of rows, the phospho-specific blot is shown with its appropriate reprobed image with antibodies against Raf-1 and Akt, respectively. (B and C) Effects of increasing concentrations of LY294002 or wortmannin on Raf-1 kinase activity. Raf-1 kinase activity was measured as described for Fig 1, using the same extracts as used for panel A. The results presented are for one experiment assayed in triplicate, with error bars to represent standard deviations from the mean.

Both compounds suppressed Raf-1 kinase activity in a dose-dependent manner, but we found only ∼70% suppression of Raf-1 kinase activity even at 100 nM wortmannin and only ∼55% suppression at 100 μM LY294002 (Fig. 3B and C). Furthermore, the levels of suppression of kinase activity did not correlate with suppression of S338 phosphorylation. Thus, whereas S338 phosphorylation was suppressed by similar amounts at 10 and 100 nM wortmannin (Fig. 3A, upper rows), kinase activity was suppressed only ∼5% at 10 nM wortmannin and ∼70% at 100 nM (Fig. 3B). Similarly, 10 μM LY294002 did not suppress S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 3A, upper rows) but suppressed Raf-1 kinase activity by ∼40% (Fig. 3C).

Pl3-kinase inhibitors suppress Ras activation.

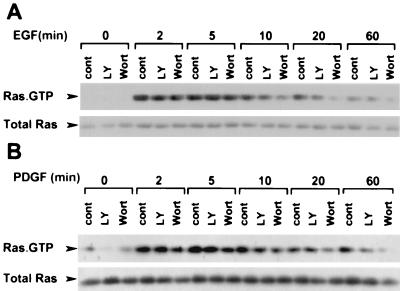

We next examined the effects of the Pl3-K inhibitors on Ras activation. For these studies, we used a nonradioactive Ras pull-down assay in which activated, endogenous Ras was isolated from cell extracts using the Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 fused to GST, followed by protein immunoblotting (14, 52). Ras was inactive in unstimulated COS cells and was rapidly activated following EGF treatment; increases were observed within 2 min, peaked between 2 and 5 min, were decreasing within 10 min, and continued to decrease out to 60 min (Fig. 4A). Pretreatment with 20 μM LY294002 or 100 nM wortmannin had no effect on Ras activation for the first 5 min following EGF treatment, but clear suppression occurred at 10, 20, and 60 min (Fig. 4A); 100 nM wortmannin suppressed Ras more effectively than did 20 μM LY294002. Similar results were obtained in NIH 3T3 cells. Ras was activated within 2 min of PDGF treatment, was maximal at 5 min, and then decreased (Fig. 4B). Wortmannin at 100 nM suppressed Ras activity at all times, whereas 20 μM LY294002 did not suppress Ras activity at 2 min but did suppress activation at later times (Fig. 4B).

FIG. 4.

Effect of PI3-kinase on Ras activity. COS (A) or NIH 3T3 (B) cells were serum starved and either preincubated with dimethyl sulfoxide (cont), 20 μM LY294002 (LY), or 100 nM wortmannin (Wort) for 20 min and then stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) (COS cells) or PDGF (50 ng/ml) (NIH 3T3 cells) for the indicated times. Active GTP-bound Ras (upper rows) was extracted from the lysates and detected as described in Materials and Methods. An immunoblot of 5% total Ras in the extracts is shown as a loading control (lower rows). Blots are for one representative experiment performed three times with similar results.

Pak3 is not activated by agents that stimulate S338 phosphorylation.

We next examined the role of Pak3 in mediating S338 phosphorylation. First, we examined whether Pak3 was active under conditions when S338 was phosphorylated. The activity of wild-type HA-Pak3 was measured in an immunoprecipitation kinase assay, using [γ-32P] ATP and MBP as substrates. In resting COS cells, wild-type HA-Pak3 had very low levels of kinase activity, whereas HA-Pak3ca was found to be highly active (Fig. 5A). However, EGF did not stimulate HA-Pak3 activity in these cells (Fig. 5A, lanes 2 to 7). In our previous studies, we demonstrated that oncogenic Ras (V12Ras) and activated Src (F527Src) stimulate strong S338 phosphorylation on Myc epitope-tagged Raf-1 (mRaf-1) in COS cells (40). We also demonstrated that V12Ras and F527Src synergized to give strong S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 (40), and similar experiments are presented here for reference (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 to 5). We tested whether V12Ras and F527Src could activate HA-Pak3 and found that coexpression of HA-Pak3 with either V12Ras or F527Src did not activate HA-Pak3 above basal levels, even when coexpressed (Fig. 5B), conditions that lead to strong S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 5.

Pak3 is not activated by EGF, V12Ras, or F527Src in COS cells. COS cells were transfected with wild-type HA-Pak3 (Pak3) and then treated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times. Equivalent amounts of HA-Pak3 were immunoprecipitated with antibody 12CA5, and kinase activity was determined in the immunoprecipitate using MBP as substrate. For each assay, the tops of the gels were transferred and blotted with antibody 12CA5 as a control of the immunoprecipitation (data not shown). As a positive control, COS cells transfected with HA-Pak3ca (Pak3ca) were included in the assays (lane 8). Gels presented are for one representative experiment of three performed with identical results. (A) EGF stimulation of HA-Pak3. Following transfection, cells were stimulated with EGF (10 ng/ml) for the indicated times, and the activity of HA-Pak3 was determined. (B) Activation of HA-Pak3 by small G proteins and F527Src. HA-Pak3 (Pak3) was coexpressed with V12Cdc42 (V12Cdc42), V12Rac (V12Rac), V12Ras (Ras), or F527Src (Src) as indicated, and the activity of HA-Pak3 was determined.

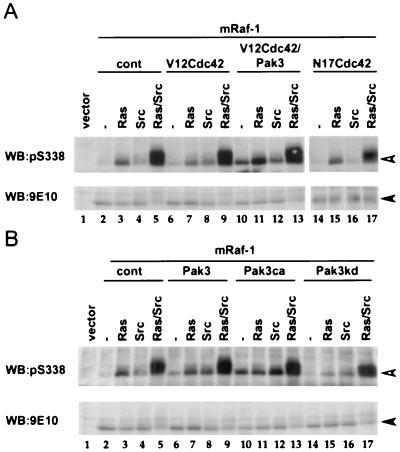

FIG. 6.

Activated Pak3 stimulates S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1. COS cells were transfected with mRaf-1 alone (−) or with V12Ras (Ras) or F527Src (Src) in the absence or presence of V12Cdc42 (V12Cdc42), HA-Pak3 (Pak3), or N17Cdc42 (N17Cdc42) (A) or with HA-Pak3ca (Pak3ca) or HA-Pak3kd (Pak3kd) (B) as indicated. Equivalent amounts of mRaf-1 were immunoprecipitated with antibody 9E10 for Western blot (WB) analysis, using the pS338 phospho-specific antibody (open arrowhead) or for mRaf-1 using antibody 9E10 (closed arrowhead). Data shown are from one representative experiment performed three times with similar results.

Activated Pak3 stimulates S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1.

Since we did not observe activation of Pak3 under any conditions that lead to S338 phosphorylation, we next tested whether conditions that stimulated strong activation of Pak3 could lead to S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1. Under our assay conditions, HA-Pak3 was strongly activated by V12Cdc42 and weakly activated by V12Rac (Fig. 5B). When adjustments were made to allow for levels of protein expression (note that protein levels were adjusted in Fig. 5 to obtain activity within the linear range of the assay [data not shown]), we estimate that HA-Pak3ca was ∼5 to 10-fold more active than HA-Pak3 activated by V12Cdc42. Thus, V12Cdc42 could stimulate HA-Pak3 activity in COS cells, but when expressed alone, V12Cdc42 did not stimulate S338 phosphorylation on mRaf-1 (Fig. 6A, lanes 2 and 6). V12Cdc42 also failed to cooperate with either V12Ras or F527Src to further stimulate the phosphorylation of S338 (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 3 to 5 and 7 to 9). Similarly, by itself, HA-Pak3 failed to stimulate S338 phosphorylation of Raf-1 and also failed to enhance V12Ras or F527Src-mediated S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 2 to 5 and 6 to 9). Finally, a dominant negative version of Cdc42 (N17Cdc42) did not suppress V12Ras- or F527Src-mediated S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6A, compare lanes 3 to 5 and 15 to 17).

Taken together, the above data suggest that neither Pak3 nor Cdc42 is limiting for Ras- and Src-mediated S338 phosphorylation of Raf-1 in COS cells. However, when V12Cdc42 was coexpressed with HA-Pak3, S338 phosphorylation on mRaf-1 was stimulated to levels similar to those obtained by coexpression of mRaf-1 with V12Ras (Fig. 6A, lanes 2, 3, and 10). Furthermore, HA-Pak3ca was also able to stimulate levels of S338 phosphorylation similar to those stimulated by V12Ras in these cells (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 and 10). V12Cdc42 plus HA-Pak3 did not synergize with either V12Ras or F527Src to stimulate S338 phosphorylation, although some additive increases in phosphorylation were seen (Fig. 6A, lanes 3 to 5 and 11 to 13). HA-Pak3ca also did not synergize with either V12Ras or F527Src to enhance S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1, but additive increases were seen with F527Src (Fig. 6B, lanes 3 to 5 and 10 to 13). Finally, HA-Pak3kd suppressed V12Ras-stimulated S338 phosphorylation, although some residual S338 phosphorylation occurred (Fig. 6B, lanes 3, 15). However, HA-Pak3kd did not suppress F527Src-stimulated S338 phosphorylation and did not affect S338 phosphorylation in the presence of V12Ras plus F527Src (Fig. 6B, compare lanes 4 and 5, and lanes 16 and 17).

Activated Pak3 does not stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity.

Since Pak3 could stimulate S338 phosphorylation under some conditions, we tested whether it was able to activate Raf-1. In our previous studies, we demonstrated that V12Ras or F527Src alone weakly activated Raf-1 in COS cells, but when coexpressed, they synergized to strongly activate Raf-1 (36, 40); these data are reproduced here for reference (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 to 5). As expected from their inability to stimulate S338 phosphorylation, V12Cdc42 alone or HA-Pak3 alone did not stimulate Raf-1 activity and did not cooperate with V12Ras, F527Src, or both activators together to enhance Raf-1 kinase activity (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 2 to 9). However, despite being able to stimulate levels of S338 phosphorylation similar to those stimulated by V12Ras (Fig. 6), HA-Pak3ca alone or HA-Pak3 plus V12Cdc42 did not stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity (Fig. 7A and B, lanes 1 and 10). Furthermore, although HA-Pak3 plus V12Cdc42 induced small additive increases in S338 phosphorylation in the presence of V12Ras or F527Src (Fig. 6A), they did not enhance mRaf-1 kinase activity (Fig. 7A). Similarly, although HA-Pak3ca enhanced 527FSrc-induced S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6B, lanes 4 and 12), it did not increase mRaf-1 kinase activity (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 12). In addition, although HA-Pak3kd strongly suppressed V12Ras-induced S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6B), it suppressed V12Ras-stimulated mRaf-1 kinase activity by only ∼50% (Fig. 7B, lanes 3 and 15); HA-Pak3kd did not suppress Raf-1 activity in the presence of F527Src (Fig. 7B, lanes 4 and 16). Finally, N17Cdc42 did not affect Raf-1 activity stimulated by V12Ras or F527Src, individually or together (data not shown). From these results, we conclude that Pak3-mediated S338 phosphorylation is insufficient to stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity; thus, we next examined why Pak3 was unable to activate Raf-1.

FIG. 7.

Effects of Cdc42 and Pak3 on Raf-1 kinase activity. COS cells were transfected with the indicated vectors as described for Fig 6. Equivalent amounts of mRaf-1 were immunoprecipitated with antibody 9E10 for kinase assays as described in Materials and Methods. The results presented are from one experiment assayed in triplicate, with error bars to represent the standard deviation from the mean. Similar result were obtained in three independent experiments.

We previously demonstrated that a version of mRaf-1 in which the Arg at position 89 was replaced with Leu (m89LRaf-1) did not become phosphorylated on S338 in the presence of V12Ras and F527Src (40), data which are reproduced here for reference (Fig. 8A, compare lanes 3 to 5 and 11 to 13). We now show that EGF-stimulated S338 phosphorylation of m89LRaf-1 was also suppressed and that dominant negative Ras (N17Ras) suppressed EGF-stimulated S338 phosphorylation on wild-type mRaf-1 (Fig. 8B). It has been shown that m89LRaf-1 does not bind to Ras-GTP (19) and so is not recruited to the plasma membrane by V12Ras (36). Thus, these data shown that S338 phosphorylation, stimulated by V12Ras, F527Src, and now by growth factors occurs at the plasma membrane. Intriguingly, however, V12Cdc42 plus HA-Pak3 and HA-Pak3ca stimulated levels of S338 phosphorylation on m89LRaf-1 similar to those that they stimulated on wild-type mRaf-1 (Fig. 8A, lanes 8, 9, 16, and 17). These data suggest either that Pak3-mediated S338 phosphorylation occurs in the cytosol or that these activated versions of Pak3 recruit Raf-1 to the plasma membrane in a Ras-independent manner. To distinguish these possibilities, detergent-free cell extracts were prepared and separated into membrane and cytosol fractions. As a control, these fractions were probed for Akt, which was present in all of the cytosolic samples but absent from the membrane fractions (Fig. 8C), demonstrating that membrane preparations were not contamination with cytosol. As expected, mRaf-1 and m89LRaf-1 were cytosolic in unstimulated cells, and V12Ras recruited wild-type mRaf-1 but not m89LRaf-1 to the membrane fraction (Fig. 8D, lanes 2, 3, 5, and 6). HA-Pak3ca did not recruit either mRaf-1 or m89LRaf-1 to the membrane fraction (Fig. 8D, lanes 4 and 7), and the kinase activity of m89LRaf-1 was not stimulated either by HA-Pak3ca or by V12Cdc42 plus HA-Pak3 (Fig. 8E). Thus, Pak3-mediated S338 phosphorylation occurs in the cytosol and not at the plasma membrane.

FIG. 8.

Pak3 phosphorylates S338 of Raf-1 in the cytosol and does not translocate Raf-1 to the plasma membrane. mRaf-1 or m89LRaf was transiently expressed in COS cells alone (−) or with V12Ras (Ras), N17Ras (N17Ras), F527Src (Src), V12Cdc42 (V12Cdc42), HA-Pak3 (Pak3), or HA-Pak3ca (Pak3ca) as indicated. (A) Phospho-S338 blot. The samples were processed as for Fig. 6. The phospho-specific Western blot (WB) image (upper row, open arrowhead) is shown together with its appropriate 9E10 expression blot (lower row, closed arrowhead). (B) EGF-stimulated S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1. The transfected cells were unstimulated (−) or stimulated with EGF for 20 min (+) as indicated. The samples were processed as in Fig. 6, and the phospho-specific image (upper row, open arrowhead) is shown together with the appropriate 9E10 expression blot (lower row, closed arrowhead). (C) Akt partitions into the cytosolic fraction. COS cells were fractionated into cytosol (upper row) and membranes (lower row) preparations. The samples were probed for endogenous Akt, the position of migration of which is shown by the arrows. (D) Pak3ca does not recruit Raf-1 to the membrane. COS cells extracts (upper row), as separated in panel C, were probed for Raf-1 in the cytosol (middle row) and in the membrane (lower row) by blotting with antibody 9E10. Raf-1 is indicated by the arrowheads. (E) Raf-1 kinase assay, performed as for Fig. 7. Results are the means ± standard errors for one representative experiment performed in triplicate. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

The inability of Pak3 to recruit Raf-1 to the plasma membrane may explain why it is unable to activate Raf-1, because Y341 phosphorylation, also necessary for activation, also occurs at the plasma membrane (40). Although we were unable to detect Y341 phosphorylation on Raf-1 in the presence of activated HA-Pak3 (data not shown), the phospho-specific antibody used for this experiment is low affinity and so may not detect low levels of Y341 phosphorylation (40). We therefore used an alternative approach to examine whether Pak3 was unable to activate mRaf-1 because it did not stimulate Y341 phosphorylation.

Raf-1 can be activated in a Src-independent manner if the tyrosines at positions 340 and 341 (Y340 and Y341, respectively) are replaced by aspartic acids (creating RafDD) (15, 18, 36, 48). RafDD has elevated basal kinase activity and can be strongly activated by V12Ras alone because, it is thought, the aspartic acid substitutions mimic tyrosine phosphorylation (15, 36, 48). However, we have recently found that in COS cells, although mRafDD is recruited to the plasma membrane in the presence of V12Ras, in the absence of V12Ras it is entirely localized to the nucleus (Y. Light and R. Marais, unpublished data). When mRafDD was coexpressed with HA-Pak3ca in COS cells, there was no effect on either S338 phosphorylation or mRafDD kinase activity (data not shown), most likely because HA-Pak3ca is cytosolic. We therefore wished to test other Src-independent mRaf-1 mutants and so generated single Asp substitutions at either Y340 or Y341 (m340DRaf-1 or m341DRaf-1, respectively). Intriguingly, the substitution at the Y340 position was a better mimic of tyrosine phosphorylation than the substitution at position Y341. Whereas m340DRaf was strongly activated by V12Ras alone (Fig. 9A), m341DRaf-1 was not (data not shown), indicating that m340DRaf-1 was independent of activated Src. However, HA-Pak3ca activated m340DRaf-1 weakly (Fig. 9A), despite stimulating levels of S338 phosphorylation similar to those seen with V12Ras (Fig. 9B).

FIG. 9.

Pak3ca does not activate m340DRaf-1. COS cells were transfected with m340DRaf-1 alone (−), with V12Ras (Ras), or with HA-Pak3ca (Pak3ca). (A) m340DRaf-1 kinase activity was determined as for Fig. 7. Data presented are the means ± standard errors for one representative experiment performed in triplicate. Similar results were observed in three independent experiments. (B) Phosphorylation of S338 of m340DRaf-1 was determined as for Fig. 6. The Western blot (WB) shown is from one representative experiment. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments.

Pak3kd does not suppress activation of m340DRaf-1.

Finally, we further explored the observation that HA-Pak3kd suppressed V12Ras-stimulated S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 6). We first considered the possibility that HA-Pak3kd interfered with Raf-1 binding of V12Ras, which we tested in two ways. First, we examined direct binding of Raf-1 to immunoprecipitated V12Ras, using monoclonal antibody Y13-238 (35). HA-Pak3kd did not affect the amount of mRaf-1 coimmunoprecipitating with V12Ras in this assay (Fig. 10A, lanes 8 and 10). Second, we examined the recruitment of mRaf-1 to the membrane fraction of the cells and found that V12Ras stimulated similar levels of mRaf-1 membrane recruitment in the absence or presence of HA-Pak3kd (Fig. 10B). Thus, Pak3kd does not interfere with the binding of mRaf-1 to V12Ras and or its recruitment to the plasma membrane. We also found that HA-Pak3kd did not suppress V12Ras-induced S338 phosphorylation of m340DRaf-1 (Fig. 10C) and that HA-Pak3kd did not suppress V12Ras-stimulated m340DRaf-1 kinase activity (Fig. 10D). Thus, unlike wild-type mRaf-1 (Fig. 6B and 7B), m340DRaf-1 was insensitive to the suppressive effects of HA-Pak3kd.

FIG. 10.

Pak3kd does not affect association with Ras or membrane translocation of mRaf-1 and does not suppress activation of m340DRaf-1. (A) Association of mRaf with V12Ras. COS cells were transfected with mRaf-1 alone (−) or with V12Ras (Ras) or with HA-Pak3kd (Pak3kd). The levels of mRaf-1 in the 5% of the total cell extracts (lanes 1 to 5) and the levels that coimmunoprecipitated (IP) with V12 Ras (lanes 6 to 10) were determined. Data shown are from one experiment; similar results were obtained in two independent experiments. WB, Western blot. (B) Pak3kd does not affect Ras-stimulated membrane recruitment of mRaf-1. COS cell were transfected with mRaf-1 alone (−) or with V12Ras (Ras) in the absence or presence of HA-Pak3kd (Pak3kd). Membrane or cytosol fractions were prepared, and the levels of mRaf-1 in the different fractions were detected by immunoblotting. Data shown are from one representative experiment of two performed with similar results. (C) Pak3kd does not suppress S338 phosphorylation on m340DRaf-1. COS cells were transfected with m340DRaf-1 in the absence or presence of V12Ras (Ras) with or without HA-Pak3kd (Pak3kd). S338 phosphorylation of m340DRaf-1 was determined as in Fig. 6. (D) Pak3kd does not suppress m340DRaf-1 kinase activity. Using the same cell extracts as for panel C, m340DRaf-1 kinase activity was determined as described for Fig. 7. Presented data are for one experiment assayed in triplicate, with error bars to represent standard deviations from the mean. Similar results were observed in three experiments.

DISCUSSION

The recent suggestion that P13-K and Pak3 regulate Raf-1 activity through S338 phosphorylation (7, 25, 49) has attracted a good deal of attention. We have tested this model using a monoclonal antibody that is highly specific for S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 (40) and found, in contradiction to the conclusions of Sun et al. (49), that S338 phosphorylation could still be observed when P13-K activity was inhibited. These different conclusions can be explained because we determined the concentrations of wortmannin or LY294002 required to inhibit P13-K activation in vivo, whereas Sun et al. based their conclusion on the observation that “both wortmannin and LY294002 inhibited EGF-induced Ser338 phosphorylation in a dose-dependent manner …” (49). Indeed, the data on S338 phosphorylation from the two studies were quite comparable; in both, some suppression in S338 phosphorylation was observed at high concentrations of these inhibitors. However, as we have shown, these concentrations are far greater than required to inhibit P13-K activity, and at lower concentrations, it was possible to observe inhibition of P13-K without inhibiting S338 phosphorylation. As recently discussed, it is almost impossible to prove a positive role in a particular biological process for a particular target of small molecule inhibitor (11). Many inhibitors have multiple targets, and both wortmannin and LY294002 have been shown to inhibit protein kinases as well as P13-K (11). We therefore conclude that P13-K is not required for growth factor-stimulated S338 phosphorylation of Raf-1.

We have also shown that some suppression of Ras activation occurred at concentrations of wortmannin and LY294002 that suppressed S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 (Fig. 4). The relationship between Ras and P13-K is complex, because P13-K has been shown to be a direct target of Ras, but on the other hand, inhibitors of P13-K can suppress Ras activation (24, 56). These differences may reflect signal strength. When low concentrations of growth factors are used, or low-density receptors are stimulated, P13-K appears to play a permissive role in Ras/ERK signaling (16, 56). By contrast, at higher growth factor concentrations or when higher-density receptors are activated, P13-K function appears not to be required (16, 56). We now show that even at high growth factor concentrations in COS cells, the P13-K inhibitors suppressed Ras activation, but only at later times (Fig. 4); in NIH 3T3 cells, PDGF-induced Ras activity was suppressed at all times. Thus, the suppression of S338 phosphorylation seen at high inhibitor concentrations may be indirect and due to suppression of Raf-1 plasma membrane recruitment, rather than direct inhibition of the S338 kinase. We have found that V12Ras-stimulated S338 phosphorylation was not blocked by overnight treatment of cells with LY294002 (A. Chiloeches and R. Marais, unpublished data). These data suggest that P13-K is not located downstream of V12Ras. They also show that when Raf-1 is localized at the plasma membrane by V12Ras, inhibition of P13-K does not suppress S338 phosphorylation, suggesting that P13-K does not directly regulate the S338 kinase. Another possibility is that S338 is phosphorylated through an autophosphorylation reaction that is stimulated when Raf-1 is recruited to the plasma membrane. However, we have found that a kinase-inactive version of Raf-1 is still phosphorylated on S338 in the presence of V12Ras (Chiloeches and Marais, unpublished), arguing against S338 being an autophosphorylation event.

Although our data show that P13-K inhibitors do not prevent S338 phosphorylation, the results could be misleading, and under some circumstances, P13-K could play a role in mediating S338 phosphorylation. First, it is possible that P13-K isoforms that are insensitive to wortmannin or LY294002 mediate this phosphorylation. However, as we show, growth factor-stimulated S473 phosphorylation on Akt is completely blocked by wortmannin or LY294002 (Fig. 1 to 3). This argues that phosphoinositide metabolism has been completely blocked and that either there are no wortmannin- or LY294002-insensitive P13-K isoforms in COS and NIH 3T3 cells or they are not activated by the growth factors used in this study. A second possibility is that there are a number of redundant pathways that mediate S338 phosphorylation, and therefore suppression of one may not be sufficient to block S338 phosphorylation. This redundancy may become apparent only under specific conditions such as the activation of Raf-1 by integrins (7). However, we have specifically addressed the proposed role of P13-K in mediating growth factor-stimulated S338 phosphorylation (49), and the role of P13-K in other circumstances will require further studies.

We have also examined whether Pak3 mediates S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1. We found that when Pak3 was activated by V12Cdc42 or by mutations that gave Cdc42 independent activity, it did stimulate S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 in COS cells. However, we provide several lines of evidence to suggest that Pak3 is not a physiological mediator of this event. First, HA-Pak3 was not activated under conditions that stimulated S338 phosphorylation (Fig. 5), and we did not detect activation of the endogenous Paks in these cells either (data not shown). Second, V12Cdc42 did not stimulate S338 phosphorylation unless HA-Pak3 was also overexpressed, and yet overexpression of HA-Pak3 did not enhance V12Ras or F527Src-mediated S338 phosphorylation. Thus, a contradiction exists; Pak3 appeared to be limiting for V12Cdc42-mediated S338 phosphorylation but not for V12Ras or F527Src-mediate phosphorylation. Third, we show that Pak3-mediated S338 phosphorylation occurred in the cytosol, whereas in all other situations, S338 phosphorylation occurs at the plasma membrane (40). Thus, another contradiction exists. In the proposed model, Pak3 is the kinase that mediates Ras-stimulated S338 phosphorylation through P13-K and Cdc42/Rac (49). It is therefore difficult to explain why Pak3, which is directly activated by V12Cdc42, phosphorylates Raf-1 in the cytosol, whereas when Ras activates Pak3 indirectly in a P13K/Cdc42-dependent manner, it is able to phosphorylate only membrane-bound Raf-1. Fourth, unlike V12Ras, activated Pak3 did not synergize with F527Src to stimulate S338 phosphorylation. Thus, a third contradiction is that if Pak3 is the kinase that mediates V12Ras-stimulated S338 phosphorylation (49), why is it unable to substitute for V12Ras and synergize with F527Src? Fifth, we show that Pak3-mediated S338 phosphorylation did not stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity.

The inability of Pak3 to stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity in our hands is clearly different from the previously published reports (25, 49), and it is difficult to explain this difference. It should be noted, however, that the previously described activation was rather weak. Pak3-stimulated Raf-1 activation was not directly compared to other activators but was said to be ∼30% of the levels stimulated by V12Ras (25). We used V12Ras and F527Src as positive controls in our studies, but even when we increased the sensitivity of our assays to permit the detection of very low levels of Raf-1 kinase activity, we did not observe Pak3-stimulated Raf-1 activity (Fig. 8 and data not shown). The inability of Pak3 to activate Raf-1 does not appear to be due to a failure to stimulate Y341 phosphorylation, because Pak3 was able to stimulate S338 phosphorylation of m340DRaf-1 but was unable to activate m340DRaf-1 (Fig. 9). However, the inability of Pak3 to stimulate Raf-1 kinase activity may be due to its inability to recruit Raf-1 to the plasma membrane (Fig. 8). Membrane recruitment may be necessary to allow interaction with many kinases that phosphorylate Raf-1, to allow interaction with lipids, or may be necessary for Raf-1 oligomerization (20, 33, 43).

Although our data argue that Pak3 does not mediate S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1, HA-Pak3kd was able to suppress V12Ras-mediated S338 phosphorylation and Raf-1 kinase activity, in agreement with the previous study (25). The suppression does not appear to occur because HA-Pak3kd blocks the interaction between Raf-1 and Ras-GTP (Fig. 10). Intriguingly, HA-Pak3kd did not suppress V12Ras-mediated S338 phosphorylation or kinase activity of m340DRaf-1 (Fig. 10) and did not suppress S338 phosphorylation or kinase activity in the presence of F527Src (Fig. 6B). Since V12Ras stimulates more S338 phosphorylation on Raf-1 than F527Src, but F527Src stimulates more Y341 phosphorylation than V12Ras (40), it is likely that in the presence of F527Src, the majority of S338 phosphorylated mRaf-1 is also phosphorylated on Y341. In the presence of V12Ras by contrast, only a small proportion of mRaf-1 will be Y341 phosphorylated. One interpretation of this data is that when Raf-1 is phosphorylated on Y341 (or if Y341 phosphorylation is mimicked as in the case of m340DRaf-1), it becomes insensitive to the suppression of S338 phosphorylation that is mediated by HA-Pak3kd. It should be remembered that Paks regulate many cellular processes, such as vesicle trafficking and cytoskeletal reorganization (2, 9, 28), and since any or all of these processes could be affected by HA-Pak3kd, the suppression of S338 phosphorylation could be indirect.

How do we interpret these data with respect to Raf-1 activation? It is known that S338 and Y341 phosphorylations are both required for Raf-1 activation stimulated by growth factors, V12Ras, and F527Src (3, 15, 40). However, we still do not know how these phosphorylations lead to Raf-1 activation, other than to state that it appears that negative charges within this region are required. Our observation that m340DRaf-1 mimicked Y341 phosphorylation better than m341DRaf-1 is in agreement with previous studies demonstrating that 340DRaf-1 was a better transforming agent than 341DRaf-1 (18) and demonstrates that not only the presence but also the position of these charges is important for Raf-1 activation. What is clear from this study is that S338 phosphorylation by itself is not sufficient to stimulate Raf-1 activity. Indeed, even when the requirement for Y341 phosphorylation was overcome by the Y340D substitution, S338 phosphorylation was not sufficient for Raf-1 activation. Also, as previously shown, the levels of S338 phosphorylation in the presence of V12Ras or F527Src do not correlate with the levels of activity stimulated by these activators (40). This reinforces the view that S338 phosphorylation cannot be used as a surrogate marker for Raf-1 activation.

How then is Raf-1 activated? It has previously been argued that the interaction with Ras-GTP, in addition to recruiting Raf-1 to the plasma membrane, also induces a conformational change in Raf-1 that is necessary for activation (13, 48; see also references 10 and 41). Using immunoprecipitation assays, we have not been able to show any interaction between Raf-1 and HA-Pak3 (data not shown). This suggests that Pak3 does not bind to the Ras-binding domain of Raf-1 and so would be unable to stimulate this conformational change. Thus, our data support a model, previously proposed (10, 41), in which Raf-1 activation is mediated by an interaction with Ras-GTP, which both recruits Raf-1 to the plasma membrane and induces a conformation change that relieves an inhibition imposed by the N terminus on the catalytic domain. This is, however, insufficient to activate Raf-1 (53), and phosphorylation events, including phosphorylation of both S338 and Y341, are required for activation. In addition, interaction with other proteins, lipids, and dimerization are all likely to play a role. The data presented here suggest that P13-K and Pak3 are not physiological mediators of S338 phosphorylation in high-level growth factor signaling, although they may play a role in other situations. Further work is therefore required to unequivocally identity of the kinases that phosphorylate Raf-1 on S338.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Richard Cerione and Shubha Bagrodia (Cornell University) for providing the Pak3 expression constructs. We also thank Christopher J. Marshall and Michael F. Olson for critical reading of the manuscript and other lab members for useful discussions.

This work is funded by the Institute of Cancer Research and the Cancer Research Campaign, United Kingdom.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arcaro A, Wymann M P. Wortmannin is a potent phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase inhibitor: the role of phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate in neutrophil responses. Biochem J. 1993;296:297–301. doi: 10.1042/bj2960297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bagrodia S, Cerione R A. PAK to the future. Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:350–355. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01618-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnard D, Diaz B, Clawson D, Marshall M. Oncogenes, growth factors and phorbol esters regulate Raf-1 through common mechanisms. Oncogene. 1998;17:1539–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bos J. All in the family? New insights and questions regarding interconnectivity of Ras, Rap1 and Ral. EMBO J. 1998;17:6776–6782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bradford M M. A rapid and sensitive method for quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burbelo P D, Drechsel D, Hall A. A conserved binding motif defines numerous candidate target proteins for both Cdc42 and Rac GTPases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:29071–29074. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chaudhary A, King W G, Mattaliano J A, Frost J A, Diaz B, Morrison D K, Cobb M H, Marshall M S, Brugge J S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase regulates Raf-1 through Pak phosphorylation of serine 338. Curr Biol. 2000;10:551–554. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cross D A, Alessi D R, Vandenheede J R, McDowell H E, Hundal H S, Cohen P. The inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin or insulin-like growth factor 1 in the rat skeletal muscle cell line L6 is blocked by wortmannin, but not by rapamycin: evidence that wortmannin blocks activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in L6 cells between Ras and Raf. Biochem J. 1994;303:21–26. doi: 10.1042/bj3030021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Daniels R H, Bokoch G M. p21-Activated protein kinase: a crucial component of morphological signaling? Trends Biochem Sci. 1999;24:350–354. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(99)01442-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daum G, Eisenmann T I, Fries H W, Troppmair J, Rapp U R. The ins and outs of Raf kinases. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:474–480. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90133-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies S P, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J. 2000;351:95–105. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3510095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis R J. MAPKs: new JNK expands the group. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:470–473. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dent P, Reardon D B, Morrison D K, Sturgill T W. Regulation of Raf-1 and Raf-1 mutants by Ras-dependent and Ras-independent mechanisms in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:4125–4135. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.8.4125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Rooij J, Bos J. Minimal Ras-binding domain of Raf1 can be used as an activation-specific probe for Ras. Oncogene. 1997;14:623–625. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz B, Barnard D, Filson A, MacDonald S, King A, Marshall M. Phosphorylation of Raf-1 serine 338-serine 339 is an essential regulatory event for Ras-dependent activation and biological signalling. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4509–4516. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duckworth B C, Cantley L C. Conditional inhibition of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade by wortmannin. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27665–27670. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Evan G I, Lewis G K, Ramsay G, Bishop J M. Isolation of monoclonal antibodies specific for human c-myc proto-oncogene product. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:3610–3616. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.12.3610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fabian J R, Daar I O, Morrison D K. Critical tyrosine residues regulate the enzymatic and biological activity of Raf-1 kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7170–7179. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.11.7170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fabian J R, Vojtek A B, Cooper J A, Morrison D K. A single amino acid change in Raf-1 inhibits Ras binding and alters Raf-1 function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5982–5986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Farrar M A, Alberol-lla J, Perlmutter R M. Activation of the Raf-1 kinase cascade by coumermycin-induced dimerization. Nature. 1996;383:178–181. doi: 10.1038/383178a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frost J A, Steen H, Shapiro P, Lewis T, Ahn N, Shaw P E, Cobb M H. Cross-cascade activation of Erks and ternary complex factors by Rho family proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:6426–6438. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guan K-L, Figueroa C, Brtva T R, Zhu T, Taylor J, Barber T D, Vojtek A B. Negative regulation of the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf by Akt. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27354–27359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hagemann C, Rapp U R. Isotype-specific functions of Raf kinases. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:34–46. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawes B E, Luttrell L M, van Biesen T, Lefkowitz R J. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase in an early intermediate in the Gβγ-mediated mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:12133–12136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.21.12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.King A J, Sun H, Diaz B, Barnard D, Miao W, Bagrodia S, Marshall M S. The protein kinase Pak3 positively regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine-338. Nature. 1998;396:180–184. doi: 10.1038/24184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.King A J, Sun H, Diaz B, Barnard D, Miao W, Bagrodia S, Marshall M S. The protein kinase Pak3 positively regulates Raf-1 activity through phosphorylation of serine-338. Nature. 2000;406:439. doi: 10.1038/24184. . (Correction.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King W G, Mattaliano M D, Chan T O, Tsichlis P N, Brugge J S. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase is required for integrin-stimulated Akt and Raf-1/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway activation. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4406–4418. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knaus U G, Bokoch G M. The p21Rac/Cdc42-activated kinases (Paks) Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 1998;30:857–862. doi: 10.1016/s1357-2725(98)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leevers S J, Marshall C J. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, ERK2, by p21ras oncoprotein. EMBO J. 1992;11:569–574. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lei M, Lu W, Meng W, Parrini M C, Eck M J, Mayer B J, Harrison S C. Structure of PAK1 in an autoinhibited conformation reveals a multistage activation switch. Cell. 2000;102:387–397. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00043-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lu W, Katz S, Gupta R, Mayer B J. Activation of Pak by membrane localization mediated by an SH3 domain from the adaptor protein Nck. Curr Biol. 1997;7:85–94. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo Z, Tzivion G, Belshaw P J, Vavvas D, Marshall M, Avruch J. Oligomerization activates c-Raf-1 through a Ras-dependent mechanism. Nature. 1996;383:181–185. doi: 10.1038/383181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manser E, Leung T, Salihuddin H, Zhaos Z S, Lim L. A brain serine/threonine protein kinase activated by Cdc42 and Rac1. Nature. 1994;367:40–46. doi: 10.1038/367040a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marais R, Light Y, Mason C, Paterson H, Olson M, Marshall C J. Requirement of Ras-GTP-Raf complexes for activation of Raf-1 by protein kinase C. Science. 1998;280:109–112. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5360.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marais R, Light Y, Paterson H F, Marshall C J. Ras recruits Raf-1 to the plasma membrane for activation by tyrosine phosphorylation. EMBO J. 1995;14:3136–3145. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb07316.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Marais R, Light Y, Paterson H F, Mason C S, Marshall C J. Differential regulation of Raf-1, A-Raf and B-Raf by oncogenic Ras and tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4378–4383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marais R, Marshall C J. Control of the ERK MAP kinase cascade by Ras and Raf. In: Parker P J, Pawson T, editors. Cell signalling. Vol. 27. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 101–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall C J. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signalling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mason C S, Springer C, Cooper R G, Superti-Furga G, Marshall C J, Marais R. Serine and tyrosine phosphorylations cooperate in Raf-1, but not B-Raf activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2137–2148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Morrison D K, Cutler R E J. The complexity of Raf-1 regulation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:174–179. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Morrison D K, Heidecker G, Rapp U R, Copeland T D. Identification of the major phosphorylation sites of the Raf-1 kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:17309–17316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mott H R, Carpenter J W, Zhong S, Ghosh S, Bell R M, Campbell S L. The solution structure of the Raf-1 cysteine-rich comain: a novel Ras and phospholipid binding site. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:8312–8317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Robinson M J, Cobb M H. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne P H, Dhand R, Vanhaesebroeck B, Gout I, Fry M, Waterfield M D, Downward J. Phosphatidylinositol-3-OH kinase as a direct target of Ras. Nature. 1994;370:527–532. doi: 10.1038/370527a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rommel C, Clarke B A, Zimmermann S, Nunez L, Rossman R, Reid K, Moelling K, Yancopoulos G D, Glass D J. Differentiation stage-specific inhibiton of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway by Akt. Science. 1999;286:1738–1741. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stokoe D, McCormick F. Activation of c-Raf-1 by Ras and Src through different mechanisms: activation in vivo and in vitro. EMBO J. 1997;16:2384–2396. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun H, King A J, Diaz B, Marshall M S. Regulation of the protein kinase Raf-1 by oncogenic Ras through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, cdc42/Rac and Pak. Curr Biol. 2000;10:281–284. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang Y, Chen Z, Ambrose D, Liu J, Gibbs J B, Chernoff J, Field J. Kinase-deficient Pak1 mutants inhibit Ras transformation of Rat-1 fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4454–4464. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tang Y, Marwaha S, Rutkowski J L, Tennekoon G I, Phillips P C, Field J. A role for Pak protein kinases in Schwann cell transformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:5139–5144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.9.5139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor S J, Shalloway D. Cell cycle-dependent activation of Ras. Curr Biol. 1996;6:1621–1627. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)70785-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Traverse S, Cohen P, Paterson H, Marshall C J, Rapp U, Grand R J A. Specific association of activated MAP kinase kinase kinase (Raf) with the plasma membranes of ras-transformed retinal cells. Oncogene. 1993;8:3175–3181. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vlahos C J, Matter W F, Hui K Y, Brown R F. A specific inhibitor of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, 2-(4-morpholinyl)-8-phenyl-4H-1-benzopyran-4-one (LY294002) J Biol Chem. 1994;269:5241–5248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vojtek A B, Der C. Increasing complexity of the Ras signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:19925–19928. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.19925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wennestrom S, Downward J. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase in activation of Ras and mitogen-activated protein kinase by epidermal growth factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:4279–4288. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yablonski D, Kane L P, Qian D, Weiss A. A Nck-Pak1 signaling module is required for T-cell receptor-mediated activation of NFAT, but not of JNK. EMBO J. 1998;17:5647–5657. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zimmermann S, Moelling K. Phosphorylation and regulation of Raf by Akt (protein kinase B) Science. 1999;286:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]