Abstract

Background:

Cannabis use among pregnant and lactating people is increasing, despite clinical evidence showing that cannabis use may be associated with low birth weight and childhood developmental deficits. Our objective was to understand why pregnant and lactating people use cannabis and how these motivations change across perinatal stages.

Methods:

Using qualitative, constructivist grounded theory methodology, we conducted telephone and virtual interviews with 52 individuals from across Canada. We selected participants using maximum variation and theoretical sampling. They were eligible if they had been pregnant or lactating within the past year and had decided to continue, cease or decrease their cannabis use during the perinatal period.

Results:

We identified 3 categories of reasons that people use cannabis during pregnancy and lactation: sensation-seeking for fun and enjoyment; symptom management of chronic conditions and conditions related to pregnancy; and coping with the unpleasant, but nonpathologized, experiences of life. Before pregnancy, participants endorsed reasons for using cannabis in these 3 categories in similar proportions, with many offering multiple reasons for use. During pregnancy, reasons for use shifted primarily to symptom management. During lactation, reasons returned to resemble those expressed before pregnancy.

Interpretation:

In this study, we showed that pregnant and lactating people use cannabis for many reasons, particularly for symptom management. Reasons for cannabis use changed across reproductive stages. The dynamic nature of the reasons for use across stages speaks to participant perception of benefits and risks, and perhaps a desire to cast cannabis use during pregnancy as therapeutic because of perceived stigma.

Cannabis use by pregnant and lactating people is increasing, though it is difficult to establish the prevalence of cannabis use in pregnancy. Reported prevalence varies from 2% to 36%, depending on the methodology used to detect use, the population studied and the definition of use.1–12 Pregnant people have reported using cannabis to manage pregnancy-related conditions (e.g., nausea, weight gain, sleep difficulty)13–19 and pre-existing conditions (e.g., mental health, insomnia, chronic pain),13,14,18 as well as to improve mood, mental, physical and spiritual well-being,16,18 provide pleasure and manage stress.13–16 Recent systematic reviews have not found empirical data on reasons for cannabis use during lactation.20,21

Evidence is still emerging about clinical outcomes related to cannabis use during pregnancy and lactation, and well-controlled studies are lacking.22–24 The available evidence is limited by reliance on self-reported data about dose, composition and timing of exposure, the changing nature of tetrahydrocannabinol levels in cannabis over time, and a lack of studies that control for known confounders such as polysubstance and tobacco use.25–31 The available evidence does suggest that cannabis use during pregnancy may be associated with complications such as low birth weight, childhood neurodevelopmental outcomes and preterm birth.22–24,32,33 Very few studies have analyzed the outcomes associated with cannabis exposure through breastmilk, with 1 study suggesting decreased infant motor development and another showing no effects on developmental outcomes.34–36 Given the potential harms identified, and in the absence of high-quality evidence available to guide practice, most clinical guidelines recommend abstinence from cannabis during pregnancy and lactation.37–39

People who perceive benefits from cannabis may wish to or may be motivated to continue using it through pregnancy and lactation, however. Counselling that explores the reasons patients are considering cannabis use and suggests related alternatives or harm reduction strategies has been identified as a helpful strategy to minimize potential harm.13,40,41,42 Such an approach requires that clinicians understand the motivations to use cannabis before pregnancy, during pregnancy and during lactation. We sought to explore why people use cannabis during pregnancy and lactation.

Methods

Study design

Given the socially constructed nature of concepts such as risk, safety and health, which are key to the phenomenon under study, we conducted a qualitative study using constructivist grounded theory.43

Participants

Eligible participants were English-speaking Canadian residents who were at least 19 years old, had been pregnant or lactating in the past year, and had used cannabis during this time or in the 3 months before pregnancy.

Sampling and recruitment

We recruited participants through study advertisements posted in prenatal clinics, on Facebook and on other social media forums relevant to parenting and pregnancy (e.g., Babycentre, The Bump). Some existing participants circulated study invitations to others. Advertisements directed potential participants to an online screening and consent form, which allowed us to select participants for diverse demographic and experiential features (i.e., maximum variation sampling) and then for features identified as theoretically relevant during initial phases of analysis (i.e., theoretical sampling).43,44

Data collection

We collected data via semi-structured interviews by phone or videoconference from November 2020 to March 2021. Four authors (A.P., J.P., S.T., M.V.) who were trained in qualitative interviewing and were unknown to participants conducted the interviews. Three interviewers were research assistants (A.P., J.P., S.T.) and 1 was the faculty member leading the study (M.V.). Interviewers wrote memos throughout the project that detailed emerging insights and documented ideas for interview guide refinement and preliminary analysis. These memos contributed to reflexive conversations and the formation of an audit trail. Interviews were transcribed verbatim and deidentified.

We developed the interview guide (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.211236/tab-related-content) based on 2 recent systematic reviews.21,42 We piloted and refined the guide within the research team, composed of people with clinical, maternal and cannabis expertise. Interviewers asked participants to discuss their cannabis use in the 3 months before their most recent pregnancy, during pregnancy and lactation. We revised the interview guide as the study progressed to pursue areas identified as theoretically relevant.

Data collection proceeded past the point of theoretical saturation (i.e., when existing theoretical categories can account for new data43,45) to collect additional interviews from people with characteristics deemed theoretically relevant to confirm saturation.

Data analysis

We conducted data analysis concurrently with data collection, and followed a staged process from initial open coding to focused coding.43 Four authors (A.P., J.P., S.T., M.V.) completed initial coding independently. They compared their insights and devised a focused coding framework. Focused coding occurred in multiple stages. First, we sought to describe and categorize reasons for use, and then we organized those reasons by individual trajectories through the use of a matrix analysis to code per participant.46 The lead author (M.V.) led coding, and 4 authors (M.V., A.P., J.P., S.T.) operationalized the framework with regular input from the rest of the team (D.G., R.L., S.M.) We achieved triangulation across analysts and participants.

We used QSR NVivo to manage the data. We used a modified member-checking approach by sharing findings from initial stages of analysis with participants, asking them to reflect on whether our interpretation resonated with their experiences. We did not return transcripts or findings from the final analysis to participants.

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (#10976). All participants provided informed consent.

Results

Fifty-two people participated in this study, including 51 women and 1 nonbinary individual. Demographic information is available in Table 1. Interviews lasted about 30 (range 12.5–67) minutes. At the time of the interview, 30 participants were pregnant and 22 were lactating. Thirty-one had other children, and we encouraged these participants to discuss their cannabis decision-making as it related to previous pregnancies. All 52 participants used cannabis before pregnancy and 30 continued to use cannabis during their current or most recent pregnancy. Thirty-three participants discussed lactation, either with their current or a previous child. Of these, 28 used cannabis during lactation.

Table 1:

Participant demographics

| Variable | No. of participants n = 52 |

|---|---|

| Pregnant | 30 |

| Lactating | 22 |

| Discussed stage in interview, regarding current or previous child | |

| Prepregnancy | 52 |

| Pregnancy | 52 |

| Lactation | 33 |

| Gender | |

| Female | 51 |

| Nonbinary | 1 |

| Self-identified race* | |

| Black | 3 |

| Hispanic | 1 |

| Indian and Guyanese | 1 |

| Indigenous | 7 |

| Jewish | 1 |

| Multiracial | 3 |

| White | 36 |

| Raising child with partner | |

| Yes | 49 |

| Chose not to answer | 2 |

| No | 1 |

| Other children (beyond current pregnancy or breastfed infant) | |

| Yes | 31 |

| No | 21 |

| Place of residence | |

| Rural | 14 |

| Suburban | 17 |

| Urban | 21 |

| Province or territory | |

| British Columbia | 17 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 |

| Alberta | 3 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 |

| Manitoba | 1 |

| Ontario | 21 |

| Quebec | 2 |

| New Brunswick | 1 |

| Nova Scotia | 2 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 2 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 |

| Level of education | |

| Some high school | 2 |

| Completed high school | 5 |

| Some college | 5 |

| Completed college | 17 |

| Some university | 3 |

| Completed university | 12 |

| Postgraduate or professional degree | 8 |

| Employment | |

| Employed full time (includes those currently on leave) | 36 |

| Employed part time | 5 |

| Not employed outside home, by choice | 4 |

| Not employed outside home, not by choice | 7 |

| Age, yr | |

| 19–24 | 2 |

| 25–29 | 12 |

| 30–34 | 25 |

| 35–39 | 11 |

| ≥ 40 | 2 |

Participants were asked to self-identify their race or ethnicity. No categories were imposed on this self-identification.

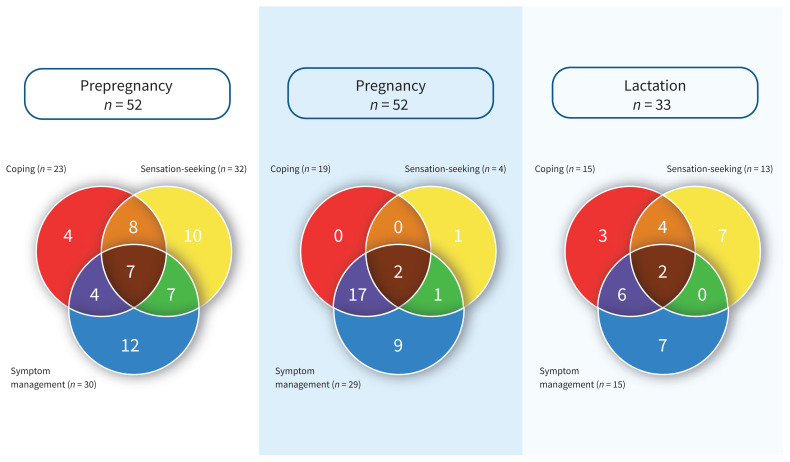

Participants described 3 categories of reasons for using cannabis (Table 2). Categories included sensation-seeking (i.e., recreational, to create an altered state or mood), symptom management (i.e., to alleviate a medical condition) and coping (i.e., to alleviate unpleasant aspects of life). Participants often offered multiple reasons for use that spanned more than 1 category. Patterns of use varied according to reproductive stage (Figure 1). Many participants described reasons for use before pregnancy in each of the 3 categories, which shifted in pregnancy, when all but 1 participant reported that they used cannabis for symptom management. Reasons given for use during lactation, however, resembled the prepregnancy distribution. Table 3 provides illustrative quotes for the findings.

Table 2:

Categories of pregnant and lactating people’s reasons for using cannabis

| Category | Definition | Indications | Representative quote |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensation-seeking | Sometimes known as “recreational” use, whereby participants are using cannabis with a desire to get high or to create an altered state. | Fun, relaxation, to get high, liking the way it feels | “If I know my evening’s going to be relaxed and I have nothing important going on anytime soon, I might have that [cannabis] just to relax and watch funny stuff or you know just to chill in the evenings” (Participant 49). |

| Symptom management | Sometimes known as “therapeutic” use, this is the use of cannabis to treat symptoms that have become problematic or an impediment to daily functioning, either at the advice or under the guidance of a health professional (medically directed symptom management) or on their own (self-directed symptom management). | Depression and anxiety, chronic pain, multiple sclerosis, posttraumatic stress disorder, menstrual cramps, fibromyalgia, eczema, migraines, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, chronic pain for conditions such as Ehlers–Danlos syndrome and hypermobility. | “Cannabis was just kind of always something that I used to sort of just help with the symptoms of anxiety and depression” (Participant 21). |

| Coping | Refers to reasons for use that improve the user’s quality of life, help them cope with what they are facing, or ease difficult or unpleasant conditions. We categorized use as being for coping when the participant’s target of improvement was not a medicalized symptom that impaired functioning, but rather a typical, nonpathologized part of life. | Sleep, stress relief, calm, focus on mundane tasks | “I just had trouble sleeping so when I had a couple puffs before bed, it would help me go to sleep quicker and stay asleep longer, which is beneficial for me the next day because I can function better” (Participant 48). |

Figure 1:

Reasons for using cannabis in each stage of reproduction, and overlap in reasons for use. Each Venn diagram depicts the number of participants who described their use as pertaining to a specific category at the described stage of reproduction. Each of the 3 categories is represented by a primary-coloured circle. The overlapping areas represent the number of participants who described their use as pertaining to multiple categories.

Table 3:

Illustrative qualitative data to support description of cannabis use at each stage of reproduction

| Stage of reproduction | Finding | Illustrative quote |

|---|---|---|

| Prepregnancy | All participants used cannabis before pregnancy for many reasons, typically beginning with recreational use. | “Long before I had [multiple sclerosis], I’ve always used recreationally” (Participant 18). |

| Many participants used cannabis to cope with the unpleasant or difficult aspects of life (e.g., to improve sleep quality, to relax, to alleviate mild anxiety). | “It was something that I found would just help me be calmer. A little more patient and just kind of like relax and let the day go kind of thing” (Participant 49). “It was a nice way to fall asleep” (Participant 10). |

|

| More than half of participants described their prepregnancy cannabis use as motivated by reasons that spanned multiple categories. | “It really helps with a myriad of problems. Like it will help with my sleep, with my headaches—I get chronic migraines — but I mean I also enjoy it [laughter]” (Participant 22). | |

| Pregnancy | Motivations for cannabis use changed during pregnancy. Many participants chose to abstain for fear of harming their developing fetus. | “I wasn’t sure of the side effects and I would hate for something to happen and it was pretty much my fault. I decided it’s only 40 weeks, I can handle 40 weeks and then afterwards I can readjust and decide through breastfeeding” (Participant 35). |

| Other reasons for ceasing included stigma, guilt, affordability, desire to remain alert and sober, and potential interference with other medications. | “I had a fear of my physician judging me” (Participant 14). “I was being put on antidepressants so I just didn’t smoke because I didn’t want to mess them up” (Participant 15). |

|

| Of those who continued to use cannabis during pregnancy, nearly all participants explained their motivation as related to symptom management for conditions that pre-existed pregnancy or were related to pregnancy (most commonly nausea and vomiting). | “I couldn’t keep anything down, including water and my own saliva, so I started using cannabis. It essentially kept me alive for half my pregnancy, if not more” (Participant 1). “During pregnancy, like once the weight hits, I get pain in my sciatica nerve” (Participant 41). |

|

| Some participants tried other medical alternatives for symptom management and found them ineffective. | “I find that the Diclectin or whatever the hell the pills they gave me for nausea, it doesn’t help as well as the cannabis does so I just kind of threw the pills away and kept smoking” (Participant 40). | |

| Many participants used cannabis for coping alongside their symptom management use. Reasons for coping were very similar to those provided prepregnancy. | “It was kind of hard to manage my anxiety and stress and taking care of a little baby, like a little child, while being pregnant, so I continued to smoke and use the edibles at that time. I found that it helped with the nausea and a lot of times it helped keep me calm and I was able to focus more” (Participant 34). | |

| Few participants described using cannabis for sensation-seeking reasons during pregnancy. | “I’m doing it for a little break and I think a doctor can’t give me any suggestions besides maybe like ‘go for a run’ or something” (Participant 44). | |

| Lactation | Participants using for sensation-seeking reasons compared cannabis and alcohol use. They found cannabis useful to relax and unwind. | “It was something I did — like it was almost like alcohol — it’s the end of the day, the kids go to bed, you have a glass of wine, well I would go smoke a bowl” (Participant 33). |

| Reasons related to symptom management during lactation resembled those described before pregnancy, as symptoms related to pregnancy (e.g., nausea) had subsided. | “I don’t have that same kind of intense emotional turmoil I had throughout my pregnancy … and the nausea is gone” (Participant 16). “Currently I use it for very bad cramps. … when I have my period” (Participant 9) |

|

| Cannabis was described by some participants as more helpful than pharmaceutical medication. | “I’ve gone from 15 pills a day and no cannabis to three pills a day and cannabis and I’m able to focus and be there for my kids and be attentive and help them cope with their own emotions because I’m not numb” (Participant 38). | |

| Coping reasons during lactation also closely resembled those provided before pregnancy, with the addition of coping with the stress and monotony of caring for a newborn. | “With all the stress of having a baby and housework and keeping up with everything I did kind of — I’m not going to lie — I did depend on it a little more” (Participant 34). “I am feeling more calm [after using cannabis] and that gives me the confidence to wean off my [antidepressant] pills” (Participant 9). |

|

| A small number of participants described their desire to use cannabis as influencing their choice to cease or not to initiate lactation. | “The milk was starting to go and the pumping was also a bit of a pain … so because of that and because of the fact that it was the thing keeping me from being able to use the marijuana — I had some episodes of anxiety where it would have been useful — I decided to stop [breastfeeding]” Participant 2). |

Prepregnancy

All 52 participants described using cannabis before pregnancy, for a variety of reasons. Sensation-seeking was the most common reason for use before pregnancy (Figure 1). A similar proportion of participants also reported using cannabis for some type of symptom management before pregnancy. Most frequently, this was self-directed, although 11 participants reported discussing their use of cannabis for symptom management with a health care provider. Many of these participants had a current or former medical authorization, although most preferred to procure cannabis independent of the medical authorization process. Another large group of participants used cannabis before pregnancy for coping with the unpleasant or difficult aspects of life, typically to improve sleep quality, to relax or to alleviate mild anxiety. More than half of participants offered multiple reasons for cannabis use that spanned all categories.

Pregnancy

During pregnancy, motivations for cannabis use changed. Twenty-two participants stopped using cannabis upon learning they were pregnant. Most of these participants abstained because of the potential for harm to the developing fetus. Others ceased because of stigma, guilt, affordability, desire to remain alert and sober, and potential interference with other medications.

The 30 participants who continued to use cannabis during pregnancy offered different reasons for use during pregnancy than before pregnancy (Figure 1). Twenty-nine participants described using cannabis for symptom management. Most commonly, this was self-directed use to manage pregnancy-related nausea and vomiting. Many participants found cannabis to be more effective than pharmaceutical remedies, and variously supplemented and substituted it for prescribed medication.

Participants frequently described using cannabis for coping purposes, alongside symptom management. Sensation-seeking was described by only 4 participants, 3 of whom also explained they were using cannabis for symptom management as well as for coping. The only participant to offer sensation-seeking as her sole reason for use during pregnancy explained that she used cannabis only twice while pregnant.

Lactation

During lactation, cannabis use patterns reverted to resemble those described before pregnancy. Of the 33 participants who discussed lactation (i.e., breastfeeding, chestfeeding or pumping), 28 chose to use cannabis during this time. Sensation-seeking, symptom management and coping reasons were described in proportions that were similar to prepregnancy use (Figure 1). Four participants described their desire to use cannabis as influencing their decision to cease or to not initiate lactation.

For most participants, lactation represented a return to prepregnancy reasons for cannabis use. Descriptions of use for symptom management and coping reasons very closely resembled those given for using cannabis before pregnancy, with the addition of coping with the physicality, stress and monotony of parenting a newborn. Some participants commented that cannabis was more effective than pharmaceutical medication for managing symptoms. When describing cannabis use for sensation-seeking purposes, many participants compared it to use of alcohol, as a way to relax and unwind at the end of the day.

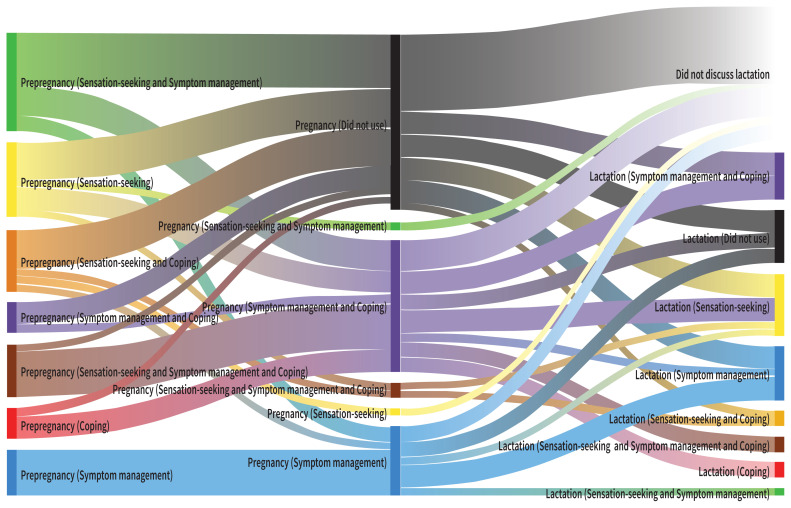

Individual trajectories

We noted little concordance between the reasons for use articulated in separate stages by individual participants (Figure 2); however, we identified 2 consistent profiles of use transitions. The first profile described sensation-seeking users who abstained during pregnancy. The second profile described participants who used cannabis for symptom management across all 3 stages for persistent conditions not related to pregnancy (e.g., depression, chronic pain). However, the most consistent pattern we identified was changing reasons for use across the 3 stages. For example, some participants who described their use as purely sensation-seeking before pregnancy described it as related to symptom management during pregnancy. Others who used it for symptom management before pregnancy stopped using altogether during pregnancy, sometimes resuming during lactation.

Figure 2:

Illustration of variation in individual reasons for use across reproductive stages. This Sankey diagram shows the change in individual reasons for cannabis use between the stages of prepregnancy, pregnancy and lactation. Sensation-seeking is represented in yellow, symptom management is in blue, and coping is in red. The secondary colours indicate participants who described overlapping reasons for use. For example, the orange line represents people who described sensation-seeking (yellow) and coping (red) reasons for use; purple represents those who described both symptom management (blue) and coping (red) reasons for use. Participants who offered all 3 reasons for use (sensation-seeking, symptom management and coping) are represented in brown. Black indicates a participant did not use cannabis in that stage. In the lactation column, white indicates that a participant did not discuss lactation, either because they chose not to breastfeed or chestfeed, or because they had not yet given birth.

Interpretation

Individual reasons for using cannabis were dynamic between reproductive stages, even among participants using cannabis to manage symptoms of chronic conditions. The changing nature of the way participants described their reasons for using cannabis during pregnancy and lactation speaks to their perception of benefits and risks, and may reflect a desire to lessen stigma by casting use during pregnancy as therapeutic.13

Our findings have very little resonance with evidence on motivations for cannabis use identified in nonpregnant populations, suggesting that motivations for use during pregnancy and lactation are unique. Of the reasons for cannabis use during pregnancy and lactation described by our participants, only 3 reasons (i.e., enjoyment, coping, sleep) correspond to domains of the Comprehensive Marijuana Motives Questionnaire.47 The reasons for use provided by our participants more closely match those identified in studies of medical cannabis use, such as for controlling pain, anxiety, depression, muscle spasms, nausea or appetite, and for sleep, with many using cannabis to manage multiple symptoms.48–50

Some of our findings are consistent with surveys of pregnant people. Surveys of people in the United States who used cannabis during pregnancy indicate they do so to relieve stress, anxiety, chronic pain, nausea and vomiting.51,52 However, our participants differed from those in previous survey studies because nearly half of the survey participants disclosed recreational cannabis use during pregnancy, which may reflect a difference in populations, greater social desirability bias in qualitative interviews or both.

Participant-reported benefits, particularly in relation to treating severe nausea symptoms, suggest the value of future research investigating the efficacy of cannabis in relieving symptoms that are not responsive to currently available medical therapy. This is an important gap in the literature about this understudied population.

Few studies have explored reasons for use during lactation, although some have noted that many people are likely to resume their prepregnancy use after giving birth.53,54 Our findings provide empirical support for this observation, with many participants who used cannabis ceasing use during pregnancy and resuming in lactation. Another small group of participants chose to cease or forego lactation to resume cannabis use. This is worrying, given that the benefits of lactation are well established.55–57

We suggest that our findings have 3 implications for practice. First, for some people, cannabis is perceived as helpful for symptom relief and coping during pregnancy. Recognizing the perceived benefits of cannabis use may assist clinicians in finding opportunities to offer alternatives or substitutes.42 These conversations may present an opportunity to weigh the perceived benefits of cannabis use, the emerging data about the potential for harm, and the safety and efficacy of other alternatives.22–24 In some cases, the pregnant or lactating person may decide that continued cannabis use has self-perceived benefits for their health and the health of the pregnancy that outweigh the risk of potential harm to the fetus or infant. Second, postpartum people will often wish to resume cannabis for similar reasons to their prepregnancy use. Counselling about the risks and benefits of cannabis use during lactation may help to reduce harm. Exploring reasons for cannabis use during lactation and offering alternatives may benefit those who would otherwise choose to avoid or abbreviate lactation in order to resume cannabis use. Third, the way people explain their cannabis use during pregnancy and lactation is dynamic. This could be an artifact of social desirability bias, or it may reflect the changing nature of symptoms across pregnancy and lactation. Counselling approaches that specifically address patients’ motivations for use, focusing on symptom management and harm reduction, may be most likely to be successful.

Limitations

We conducted this study in Canada, where recreational and medical cannabis is legal and readily available. Qualitative researchers do not strive for representative samples, but rather for samples of participants likely to yield rich experiential data. Our sample was diverse in age, geography, education and occupation, but, similar to other studies of medical cannabis, participants were more likely to be white or Indigenous than the general population.48,50 Findings may have limited transferability to pregnant and lactating people with other racial identities.

Conclusion

Of the 52 pregnant and lactating people interviewed in this qualitative study, those who chose to use cannabis during pregnancy did so mainly to manage symptoms of pregnancy and pre-existing conditions. During lactation, participants used cannabis for reasons that resembled their prepregnancy use, including for enjoyment and relaxation. A small number of participants ceased lactation to resume cannabis use. Most participants who ceased using cannabis during pregnancy or lactation did so because they were worried about the risk of harm to their fetus or infant. Recognizing that many pregnant and lactating people endorse cannabis for symptom management may provide opportunities for clinicians to discuss alternatives that have been proven safe for this population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Competing interests: From April to December 2019, Janelle Panday was employed as a research analyst at PureSinse Inc. (a licensed cannabis producer), outside the submitted work. She does not hold any remaining financial or personal connection to PureSinse, which is no longer in operation.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Meredith Vanstone, Devon Greyson, Robin Lennox and Sarah McDonald designed the study. Meredith Vanstone, Shipra Taneja, Anuoluwa Popoola and Janelle Panday collected data. All authors contributed to data analysis. Meredith Vanstone drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised it, gave approval of the final version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: This research was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FRN 167972). Sarah McDonald is supported by a Tier II Canada Research Chair.

Data sharing: This data set is not available for sharing. When participants consented to participating in the study, they did not consent to access to transcripts or data beyond the research team. Some complete qualitative transcripts may be identifiable. Readers are welcome to contact the corresponding author for further clarification.

References

- 1.Brown QL, Sarvet AL, Shmulewitz D, et al. Trends in marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant reproductive-aged women, 2002–2014. JAMA 2017;317:207–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Corsi DJ, Hsu H, Weiss D, et al. Trends and correlates of cannabis use in pregnancy: a population-based study in Ontario, Canada from 2012 to 2017. Can J Public Health 2019;110:76–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McLaughlin J, Castrodale L, editors. Marijuana use among women delivering live births in Alaska, 2002–2011. Anchorage: Department of Health and Social Services; [Bulletin no 5]; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beatty JR, Svikis DS, Ondersma SJ. Prevalence and perceived financial costs of marijuana versus tobacco use among urban low-income pregnant women. J Addict Res Ther 2012;3:1000135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ko JY, Farr SL, Tong VT, et al. Prevalence and patterns of marijuana use among pregnant and nonpregnant women of reproductive age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:201.e1–201.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Petrangelo A, Czuzoj-Shulman N, Balayla J, et al. Cannabis abuse or dependence during pregnancy: a population-based cohort study on 12 million births. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2019;41:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muckle G, Laflamme D, Gagnon J, et al. Alcohol, smoking, and drug use among Inuit women of childbearing age during pregnancy and the risk to children. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2011;35:1081–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young-Wolff KC, Tucker L-Y, Alexeeff S, et al. Trends in self-reported and biochemically tested marijuana use among pregnant females in California from 2009–2016. JAMA 2017;318:2490–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cerdá M, Wall M, Keyes KM, et al. Medical marijuana laws in 50 states: investigating the relationship between state legalization of medical marijuana and marijuana use, abuse and dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend 2012;120:22–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cannabis Survey. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey: summary of results for 2017. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bayrampour H, Asim A. Cannabis use during the pre-conception period and pregnancy after legalization. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2021;43:740–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbosa-Leiker C, Burduli E, Smith CL, et al. Daily cannabis use during pregnancy and postpartum in a state with legalized recreational cannabis. J Addict Med 2020; 14:467–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang JC, Tarr JA, Holland CL, et al. Beliefs and attitudes regarding prenatal marijuana use: perspectives of pregnant women who report use. Drug Alcohol Depend 2019;196:14–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curry WL. Hyperemesis gravidarum and clinical cannabis: to eat or not to eat? J Cannabis Ther 2002;2:63–83. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dreher MC. Poor and pregnant: perinatal ganja use in rural Jamaica. Adv Alcohol Subst Abuse 1989;8:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mark K, Gryczynski J, Axenfeld E, et al. Pregnant women’s current and intended cannabis use in relation to their views toward legalization and knowledge of potential harm. J Addict Med 2017;11:211–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Young-Wolff KC, Gali K, Sarovar V, et al. Women’s questions about perinatal cannabis use and health care providers’ responses. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2020;29:919–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Postonogova T, Xu C, Moore A. Marijuana during labour: a survey of maternal opinions. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020;42:774–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bayrampour H, Zahradnik M, Lisonkova S, et al. Women’s perspectives about cannabis use during pregnancy and the postpartum period: an integrative review. Prev Med 2019;119:17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vanstone M, Panday J, Popoola A, et al. Pregnant people’s perspectives on cannabis use in pregnancy: a systematic review and integrative mixed-methods research synthesis. Authorea PrePrints 2021. Mar. 17. doi: 10.22541/au.161598597.73269137/v1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gunn JK, Rosales CB, Center K, et al. Prenatal exposure to cannabis and maternal and child health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson R, DeJong K, Lo J. Marijuana use in pregnancy: a review. Obstet Gynecol Surv 2019;74:415–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stickrath E. Marijuana use in pregnancy: an updated look at marijuana use and its impact on pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2019;62:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Metz TD, Stickrath EH. Marijuana use in pregnancy and lactation: a review of the evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;213:761–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fried PA, Watkinson B, Willan A. Marijuana use during pregnancy and decreased length of gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984;150:23–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hayatbakhsh MR, Flenady VJ, Gibbons KS, et al. Birth outcomes associated with cannabis use before and during pregnancy. Pediatr Res 2012;71:215–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Day N, Cornelius M, Goldschmidt L, et al. The effects of prenatal tobacco and marijuana use on offspring growth from birth through 3 years of age. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1992;14:407–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huizink AC, Mulder EJH. Maternal smoking, drinking or cannabis use during pregnancy and neurobehavioral and cognitive functioning in human offspring. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2006;30:24–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Passey ME, Sanson-Fisher RW, D’Este CA, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and cannabis use during pregnancy: clustering of risks. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014;134:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Prunet C, Blondel B. Cannabis use during pregnancy in France in 2010. BJOG 2014;121:971–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roncero C, Valriberas-Herrero I, Mezzatesta-Gava M, et al. Cannabis use during pregnancy and its relationship with fetal developmental outcomes and psychiatric disorders. A systematic review. Reprod Health 2020;17:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Corsi DJ, Walsh L, Weiss D, et al. Association between self-reported prenatal cannabis use and maternal, perinatal, and neonatal outcomes. JAMA 2019;322:145–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ordean A, Kim G. Cannabis use during lactation: literature review and clinical recommendations. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2020;42:1248–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Badowski S, Smith G. Cannabis use during pregnancy and postpartum. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:98–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tennes K, Avitable N, Blackard C, et al. Marijuana: prenatal and postnatal exposure in the human. NIDA Res Monogr 1985;59:48–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Badowski S, Smith G. Cannabis use during pregnancy and post-partum. Can Fam Physician 2020;66:98–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ordean A, Wong S, Graves L. No. 349-substance use in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol 2017;39:922–37.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Committee opinion no. 722: marijuana use during pregnancy and lactation. Obstet Gynecol 2017;130:e205–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dennis C-L, Vigod S. Cannabis use in pregnancy: a harm reduction approach is needed with a focus on prevention and positive intervention. Evid Based Nurs 2021;24:58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jaques SC, Kingsbury A, Henshcke P, et al. Cannabis, the pregnant woman and her child: weeding out the myths. J Perinatol 2014;34:417–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panday J, Taneja S, Popoola A, et al. Clinician responses to cannabis use during pregnancy and lactation: a systematic review and integrative mixed-methods research synthesis. 2021. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Charmaz K. Constructing grounded theory. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coyne IT. Sampling in qualitative research. Purposeful and theoretical sampling; merging or clear boundaries? J Adv Nurs 1997;26:623–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T, et al. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant 2018;52: 1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lee CM, Neighbors C, Hendershot CS, et al. Development and preliminary validation of a comprehensive marijuana motives questionnaire. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2009;70:279–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Walsh Z, Callaway R, Belle-Isle L, et al. Cannabis for therapeutic purposes: patient characteristics, access, and reasons for use. Int J Drug Policy 2013;24: 511–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ware MA, Adams H, Guy G. The medicinal use of cannabis in the UK: results of a nationwide survey. Int J Clin Pract 2005;59:291–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reinarman C, Nunberg H, Lanthier F, et al. Who are medical marijuana patients? Population characteristics from nine California assessment clinics. J Psychoactive Drugs 2011;43:128–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ko JY, Coy KC, Haight SC, et al. Characteristics of marijuana use during pregnancy—eight states, pregnancy risk assessment monitoring system, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1058–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Skelton KR, Hecht AA, Benjamin-Neelon SE. Women’s cannabis use before, during, and after pregnancy in New Hampshire. Prev Med Rep 2020;20:101262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Astley SJ, Little RE. Maternal marijuana use during lactation and infant development at one year. Neurotoxicol Teratol 1990;12:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Crume TL, Juhl AL, Brooks-Russell A, et al. Cannabis use during the perinatal period in a state with legalized recreational and medical marijuana: The association between maternal characteristics, breastfeeding patterns, and neonatal outcomes. J Pediatr 2018;197:90–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bernardo H, Cesar V. Long-term effects of breastfeeding: a systematic review. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chowdhury R, Sinha B, Sankar MJ, et al. Breastfeeding and maternal health outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104: 96–113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sankar MJ, Sinha B, Chowdhury R, et al. Optimal breastfeeding practices and infant and child mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr 2015;104:3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.