KEY POINTS

In Canada, reported cases of gonorrhea have more than doubled in recent years; the rate of disseminated gonococcal infection has dramatically increased in Manitoba.

Disseminated gonococcal infection classically presents with polyarthralgia, tenosynovitis and rash, and may occur in the absence of genitourinary, rectal or pharyngeal symptoms.

Untreated gonorrhea can cause potentially fatal conditions, such as infective endocarditis associated with valvular destruction, cardiac fistulae and abscesses.

A sexual history and gonorrhea nucleic acid amplification testing at the anatomic site of sexual activity should be included in the routine evaluation of patients with acute arthritis or arthralgia.

A 54-year-old man was sent to the emergency department by his family doctor for evaluation of a new cardiac murmur. His medical history included gastroesophageal reflux disease and degenerative disc disease. He lived in a home with his wife, rarely consumed alcohol and denied smoking or using other substances.

Two weeks prior, the patient had a subacute onset of subjective fevers and chills, and arthritis of his right knee and left wrist, with associated erythema, pain and swelling. He visited a walk-in clinic, where he was prescribed naproxen.

On presentation to the emergency department, the patient’s temperature was 37.1°C, his pulse was 80 beats per minute, his blood pressure was 109/62 mm Hg, his respiratory rate was 24 breaths per minute and his oxygen saturation was 97% on room air. On auscultation, the patient had a grade III to VI early diastolic murmur, as well as faint crackles to the lung bases. Examination of his abdomen was unremarkable and he did not have a rash on his skin or mucosal surfaces. He had mild swelling and pain to his right knee and left wrist, but no erythema. Point-of-care ultrasonography of the lungs and heart showed diffuse bilateral B-lines, consistent with pulmonary edema, and aortic regurgitation.

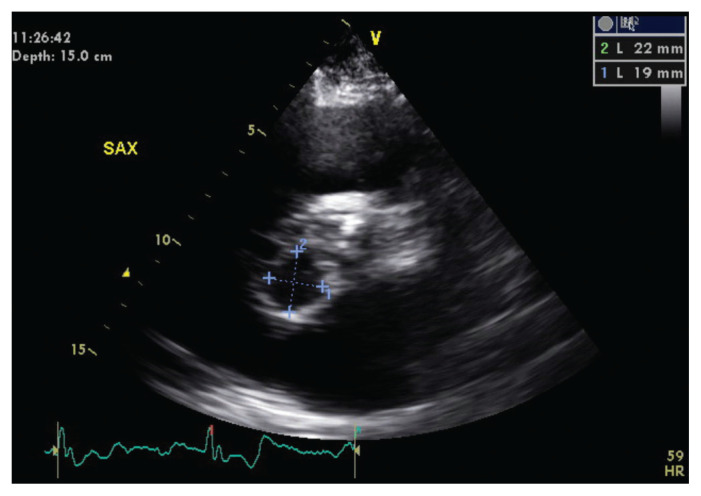

Initial laboratory investigations showed a neutrophil-dominant leukocytosis of 22 (normal 4.5–11.0) cells × 109/L, a hemoglobin of 126 (normal 125–170) g/L, platelets of 164 (normal 130–380) × 109/L and a creatinine of 137 μmol/L, increased from a baseline of 90 μmol/L. The patient’s C-reactive protein was 209 mg/L (normal ≤ 10 mg/L). Liver enzymes were within normal limits. Chest radiography showed pulmonary edema, and electrocardiography showed a complete heart block with a ventricular escape rate. Transthoracic echocardiography showed a bicuspid aortic valve and severe aortic insufficiency, as well as a 22 × 19 mm aortic root abscess and moderate mitral insufficiency (Figure 1). The aortic root abscess was later confirmed with transesophageal echocardiography, which also showed a fistula from the right ventricle to the aortic root (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.211038/tab-related-content). Two sets of blood cultures, drawn before empiric administration of intravenous ceftriaxone (2 g daily) and vancomycin, grew Neisseria gonorrhoeae, identified to the species level using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry. We diagnosed gonococcal endocarditis.

Figure 1:

Transthoracic echocardiogram from a 54-year-old man with gonococcal endocarditis showing a 22 × 19 mm aortic root abscess (blue dotted lines).

Testing subsequently showed the strain’s susceptibility to azithromycin and ceftriaxone (Appendix 3, Table 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.211038/tab-related-content). We stopped vancomycin and prescribed oral azithromycin (1 g, once only) and continued ceftriaxone. We did not obtain oral, genital or rectal samples for gonococcal testing. Subsequent results from HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B and hepatitis C tests were negative.

We admitted the patient to the cardiac intensive care unit, where his care was led by intensivists, with guidance from the infectious disease, nephrology and cardiovascular surgery services. The patient underwent a modified Bentall procedure, a surgical aortic valve replacement with insertion of a bioprosthetic valve and concomitant aortic root repair. Intraoperative findings showed a fistula between the aortic root and the right ventricle, as well as extensive destruction of the left ventricular outflow tract. He required venous–arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation and inotropic support for 2 days after surgery. He remained in complete heart block requiring temporary transvenous pacing.

Aortic valve tissue gram stain and culture were negative for bacteria, but 16S rRNA gene sequencing of aortic valve tissue confirmed the presence of N. gonorrhoeae. The 16S rRNA result was confirmed at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory, where N. gonorrhoeae multiantigen sequence typing (NG-MAST) of the porA and tbpB genes was performed (Appendix 3, Table 2). Valvular pathology showed an active purulent process with neutrophilic infiltration. When asked about sexual partners, the patient reported contact only with his wife; he did not recall any genitourinary, pharyngeal or rectal symptoms before presentation. We informed local public health services of this case to facilitate contact notification, testing and treatment.

The patient’s postoperative course was complicated by acute tubular necrosis requiring continuous renal replacement therapy. Two weeks after surgery, he underwent implantation of a dual-chamber permanent pacemaker. We continued administration of ceftriaxone for 28 days after the valve replacement. The patient transitioned from continuous renal replacement therapy to intermediate hemodialysis, and was discharged home. Two months after cardiovascular surgery, his kidney function improved and he stopped hemodialysis. He remained well at nephrology follow-up 11 months after initial presentation.

Discussion

Epidemiology

National rates of disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) are not available, but data from the Public Health Agency of Canada show a concerning increase in reported cases of gonorrhea.1 From 2013 to 2017, case counts more than doubled and the national incidence of gonorrhoea increased by 96% (from 40.6 to 79.5 cases per 100 000 population).1

Manitoba is experiencing a precipitous increase in cases of gonorrhea and DGI. Reported cases of gonorrhea have tripled in recent years, from an annual average of 1165 (range 1055 to 1349 per year) from 2011 to 2015 to an average of 3526 (range 3363 to 3741 per year) from 2017 to 2020 (unpublished data). Only 5 culture-positive cases of DGI were recorded from 2013 to 2015, whereas 95 culture-positive isolates were recovered from 2017 to 2020 (unpublished data). In 2020 alone, Manitoba’s Cadham Provincial Laboratory recorded 39 cases of DGI, including 18 cases associated with bacteremia (unpublished data). These numbers are likely underestimates of the true incidence of DGI, as they exclusively reflect the cases confirmed by isolation of N. gonorrhoeae on culture. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the incidence of DGI in Manitoba has not yet been determined. Other jurisdictions have documented a reduction in the availability of sexual health services.2

In Manitoba, NG-MAST is routinely performed on DGI isolates. Sequence typing shows that the increase in gonococcal disease is not caused by a single virulent clone. The sequence profile of this patient’s isolate has been observed with other cases of DGI, but was not found in 3 other recent cases of gonococcal endocarditis managed by our team. Further studies are necessary to elucidate whether changes in pathogen strains, or other behavioural factors, are contributing to the recent increase in DGI in Manitoba.

Clinical manifestation

Disseminated gonococcal infection is classically associated with the triad of polyarthralgia, tenosynovitis and rash, and remains one of the most common causes of septic arthritis.3–5 Gonorrhea testing should be considered for patients who are sexually active presenting with acute nontraumatic arthritis. In the preantibiotic era, N. gonorrhoeae was one of the leading causes of infective endocarditis, but endocarditis has since become extremely rare.6,7 Gonococcal endocarditis may occur in the absence of classic symptoms of DGI or, in one-third of patients, after these symptoms resolve.6,7 Small case series have shown that gonococcal endocarditis has a tendency to involve the aortic valve, often with abscess formation or large vegetations.7 Gonococcal endocarditis is associated with high mortality, likely because of a tendency to cause destructive valvular disease and hemodynamic instability, despite appropriate antibiotic therapy.7

Diagnosis

Despite the capacity of N. gonorrhoeae to cause rapid tissue destruction, culture of the organism is challenging because of its stringent growth requirements. Blood and other fluid or tissue cultures may be falsely negative, especially if the sample was drawn after initiation of antimicrobial therapy.8 Although nucleic acid amplification testing (NAAT) remains the diagnostic method of choice for urogenital specimens, commercial assays have not been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration or Health Canada for blood or synovial fluid.5,8 In suspected cases, sexual history should guide the anatomic site of sample collection for NAAT.5 For example, a patient who exclusively engages in receptive anal sex may have a negative urethral, urine, cervical or vaginal NAAT, despite having active rectal gonorrhea. As described here, molecular testing or targeted gene sequencing of affected tissue or sterile fluid may also be used to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment

Given the tendency of N. gonorrhoeae to cause severe valvular destruction, leading to subsequent heart failure, valvular replacement surgery is often required, in addition to antimicrobial therapy, in the management of gonococcal endocarditis.7 Although robust data are limited, antimicrobial treatment of gonococcal endocarditis typically includes 4 weeks of intravenous ceftriaxone, with an initial short course of azithromycin or doxycycline for possible chlamydia coinfection and to mitigate emerging gonorrheal resistance.5 For uncomplicated urogenital, anorectal and pharyngeal gonorrhea, the Public Health Agency of Canada recommends treatment with ceftriaxone (250 mg intramuscularly in a single dose) and azithromycin (1 g orally in a single dose).5 The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently changed their treatment guidelines for uncomplicated gonorrhea to a higher dose of ceftriaxone (500 mg, intramuscularly) with doxycycline (100 mg orally, twice a day for 7 d) to reflect considerations of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics, and emerging macrolide resistance.9

Conclusion

Although uncommon, gonococcal endocarditis often causes extensive cardiac destruction and may be fatal without prompt antimicrobial therapy and cardiovascular surgery. Cases of gonococcal endocarditis highlight an abrupt re-emergence of widespread gonococcal disease. As N. gonorrhoeae remains one of the most common causes of arthritis and arthralgia, a sexual history and gonococcal testing at the anatomic site of sexual activity should be included in the evaluation of patients presenting with new-onset arthritis or arthralgia. Notification, testing and treatment of sexual contacts of positive cases is essential to curb the current increase in the frequency of gonococcal infection.

Please see the accompanying videos of the transesophageal echocardiography, available at https://www.cmaj.ca/lookup/doi/10.1503/cmaj.211038/tab-related-content.

The section Cases presents brief case reports that convey clear, practical lessons. Preference is given to common presentations of important rare conditions, and important unusual presentations of common problems. Articles start with a case presentation (500 words maximum), and a discussion of the underlying condition follows (1000 words maximum). Visual elements (e.g., tables of the differential diagnosis, clinical features or diagnostic approach) are encouraged. Consent from patients for publication of their story is a necessity. See information for authors at www.cmaj.ca.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patient for his positive outlook and his willingness to participate in this project, despite the sensitive nature of this diagnosis. They thank Dr. Robin Ducas for generously providing the pictures and videos from the echocardiography, as well as Irene Martin and the Streptococcus & STI Unit of the National Microbiology Laboratory for NG-MAST analysis. They would also like to acknowledge the ongoing contributions of their hospital and laboratory colleagues affiliated with Shared Health and Cadham Provincial Laboratory.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

The authors have obtained patient consent.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the conception of the work. Carl Boodman contributed to designing the work, acquiring the data and drafting the manuscript. All of the authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content, gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1.Report on sexually transmitted infections in Canada, 2017. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2019, modified 2020 Jan. 27. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/report-sexually-transmitted-infections-canada-2017.html#a5 (accessed 2021 May 11). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nagendra G, Carnevale C, Neu N, et al. The potential impact and availability of sexual health services during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Transm Dis 2020; 47:434–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2003;17:201–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang DA, Tambyah PA. Septic arthritis in immunocompetent and immunosuppressed hosts. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2015;29:275–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Canadian guidelines on sexually transmitted infections: summary of recommendations for Chlamydia trachomatis (CT), Neisseria gonorrhoeae (NG) and syphilis. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2019, modified 2019 May 7. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/services/health/publications/diseases-conditions/guidelines-sti-recommendations-chlamydia-trachomatis-neisseria-gonorrhoeae-syphilis-2019.html (accessed 2021 Mar. 1). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shetty A, Ribeiro D, Evans A, et al. Gonococcal endocarditis: a rare complication of a common disease. J Clin Pathol 2004;57:780–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jackman JD, Jr, Glamann DB. Gonococcal endocarditis: twenty-five year experience. Am J Med Sci 1991;301:221–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations for the laboratory-based detection of Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: 2014. MMWR Recomm Rep 2014;63:1–19. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.St Cyr S, Barbee L, Workowski K, et al. Update to CDC’s treatment guidelines for gonococcal infection, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1911–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.