Abstract

Background

In a review and meta‐analysis conducted in 1993, psychological preparation was found to be beneficial for a range of outcome variables including pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay and negative affect. Since this review, more detailed bibliographic searching has become possible, additional studies testing psychological preparation for surgery have been completed and hospital procedures have changed. The present review examines whether psychological preparation (procedural information, sensory information, cognitive intervention, relaxation, hypnosis and emotion‐focused intervention) has impact on the outcomes of postoperative pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay and negative affect.

Objectives

To review the effects of psychological preparation on postoperative outcomes in adults undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthetic.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2014, Issue 5), MEDLINE (OVID SP) (1950 to May 2014), EMBASE (OVID SP) (1982 to May 2014), PsycINFO (OVID SP) (1982 to May 2014), CINAHL (EBESCOhost) (1980 to May 2014), Dissertation Abstracts (to May 2014) and Web of Science (1946 to May 2014). We searched reference lists of relevant studies and contacted authors to identify unpublished studies. We reran the searches in July 2015 and placed the 38 studies of interest in the `awaiting classification' section of this review.

Selection criteria

We included randomized controlled trials of adult participants (aged 16 or older) undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthesia. We excluded studies focusing on patient groups with clinically diagnosed psychological morbidity. We did not limit the search by language or publication status. We included studies testing a preoperative psychological intervention that included at least one of these seven techniques: procedural information; sensory information; behavioural instruction; cognitive intervention; relaxation techniques; hypnosis; emotion‐focused intervention. We included studies that examined any one of our postoperative outcome measures (pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay, negative affect) within one month post‐surgery.

Data collection and analysis

One author checked titles and abstracts to exclude obviously irrelevant studies. We obtained full reports of apparently relevant studies; two authors fully screened these. Two authors independently extracted data and resolved discrepancies by discussion.

Where possible we used random‐effects meta‐analyses to combine the results from individual studies. For length of stay we pooled mean differences. For pain and negative affect we used a standardized effect size (the standardized mean difference (SMD), or Hedges' g) to combine data from different outcome measures. If data were not available in a form suitable for meta‐analysis we performed a narrative review.

Main results

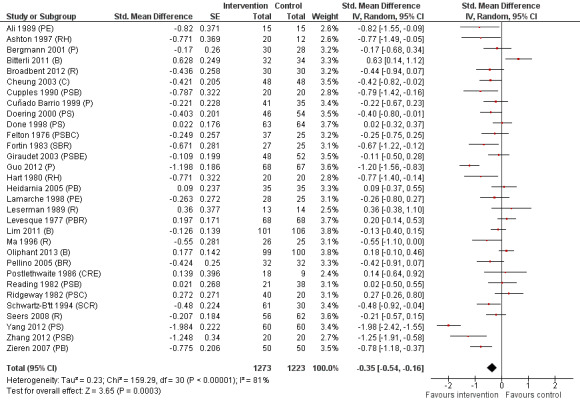

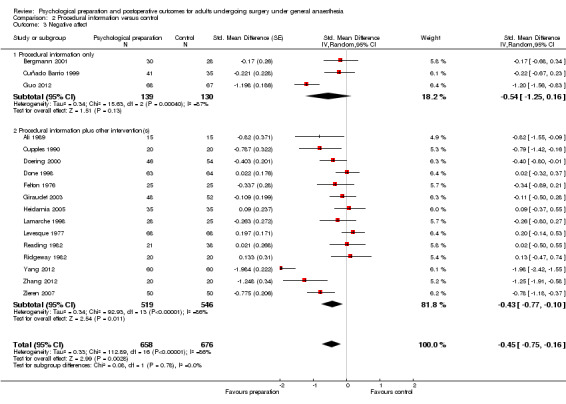

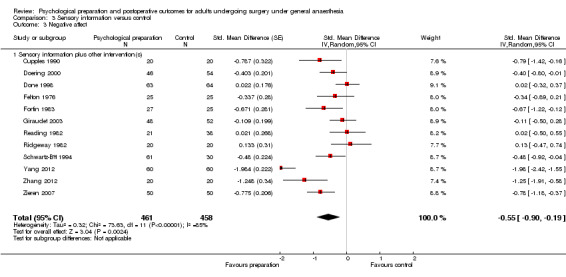

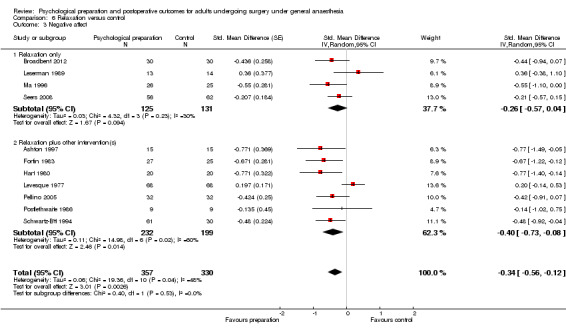

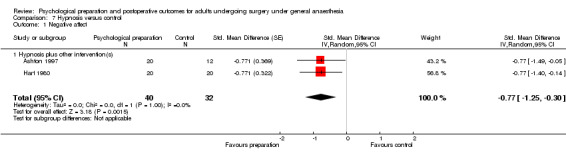

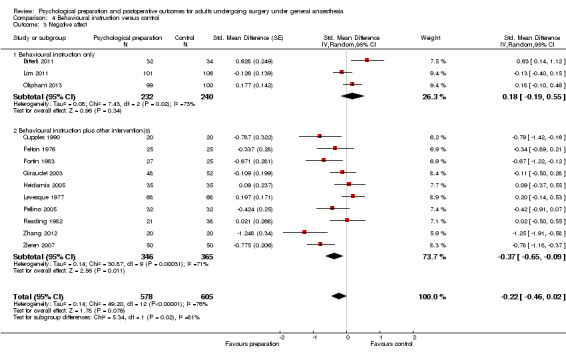

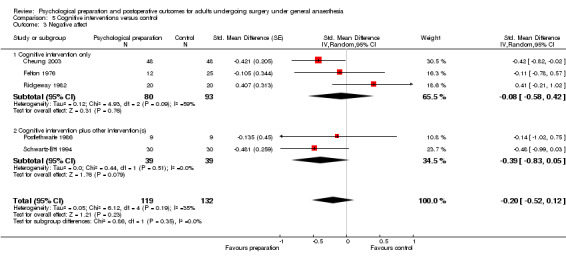

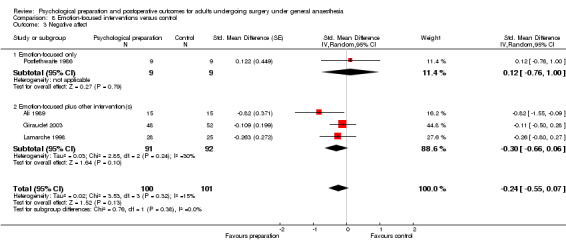

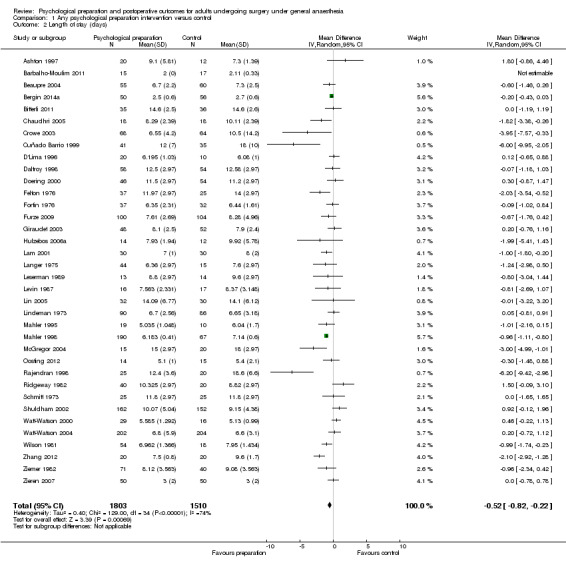

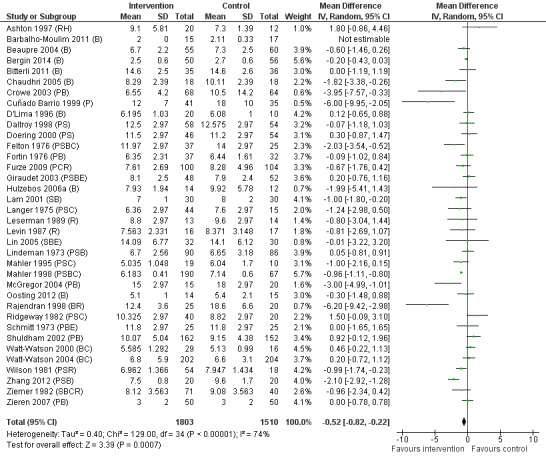

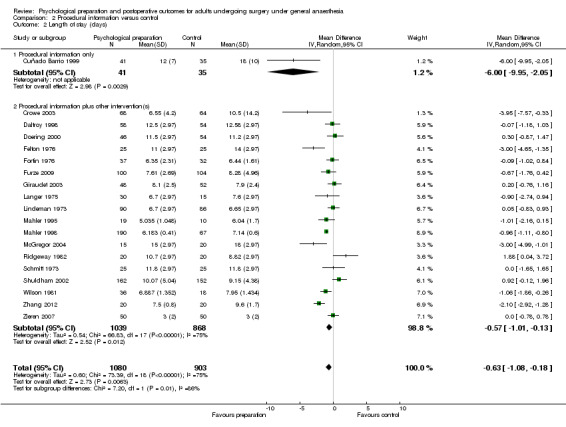

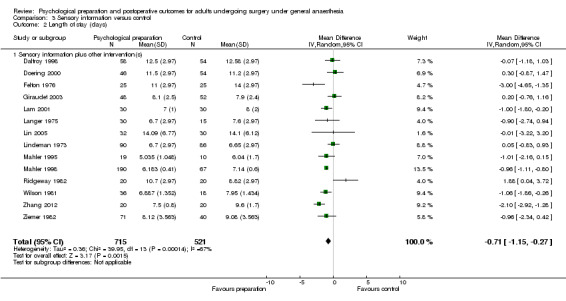

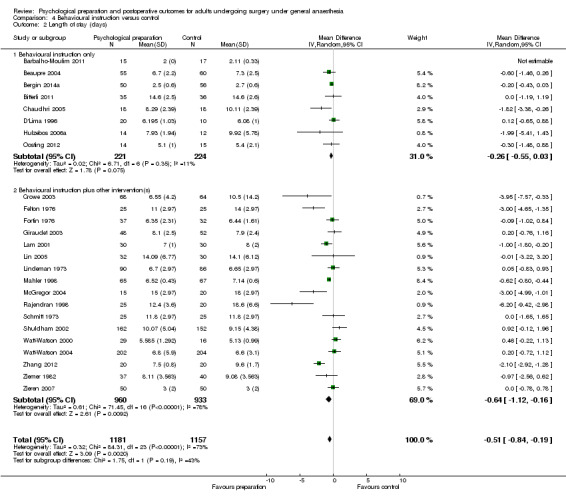

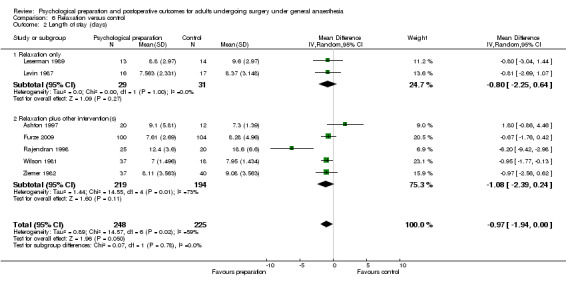

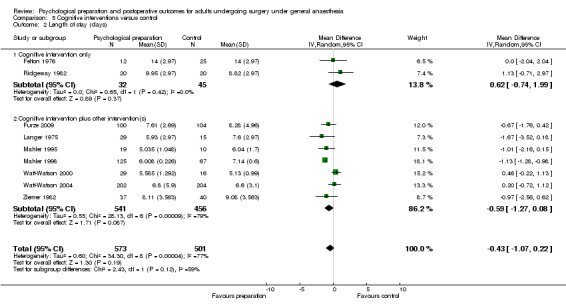

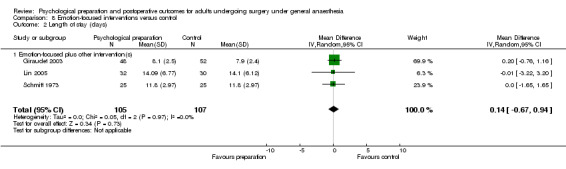

Searches identified 5116 unique papers; we retrieved 827 for full screening. In this review, we included 105 studies from 115 papers, in which 10,302 participants were randomized. Mainly as a result of updating the search in July 2015, 38 papers are awaiting classification. Sixty‐one of the 105 studies measured the outcome pain, 14 behavioural recovery, 58 length of stay and 49 negative affect. Participants underwent a wide range of surgical procedures, and a range of psychological components were used in interventions, frequently in combination. In the 105 studies, appropriate data were provided for the meta‐analysis of 38 studies measuring the outcome postoperative pain (2713 participants), 36 for length of stay (3313 participants) and 31 for negative affect (2496 participants). We narratively reviewed the remaining studies (including the 14 studies with 1441 participants addressing behavioural recovery). When pooling the results for all types of intervention there was low quality evidence that psychological preparation techniques were associated with lower postoperative pain (SMD ‐0.20, 95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.35 to ‐0.06), length of stay (mean difference ‐0.52 days, 95% CI ‐0.82 to ‐0.22) and negative affect (SMD ‐0.35, 95% CI ‐0.54 to ‐0.16) compared with controls. Results tended to be similar for all categories of intervention, although there was no evidence that behavioural instruction reduced the outcome pain. However, caution must be exercised when interpreting the results because of heterogeneity in the types of surgery, interventions and outcomes. Narratively reviewed evidence for the outcome behavioural recovery provided very low quality evidence that psychological preparation, in particular behavioural instruction, may have potential to improve behavioural recovery outcomes, but no clear conclusions could be reached.

Generally, the evidence suffered from poor reporting, meaning that few studies could be classified as having low risk of bias. Overall,we rated the quality of evidence for each outcome as ‘low’ because of the high level of heterogeneity in meta‐analysed studies and the unclear risk of bias. In addition, for the outcome behavioural recovery, too few studies used robust measures and reported suitable data for meta‐analysis, so we rated the quality of evidence as `very low'.

Authors' conclusions

The evidence suggested that psychological preparation may be beneficial for the outcomes postoperative pain, behavioural recovery, negative affect and length of stay, and is unlikely to be harmful. However, at present, the strength of evidence is insufficient to reach firm conclusions on the role of psychological preparation for surgery. Further analyses are needed to explore the heterogeneity in the data, to identify more specifically when intervention techniques are of benefit. As the current evidence quality is low or very low, there is a need for well‐conducted and clearly reported research.

Plain language summary

The effect of psychological preparation on pain, behavioural recovery, negative emotion and length of stay after surgery

Background

The way people think and feel before surgery can affect how they feel and what they do after surgery. For example, research shows that people who feel more anxious before their surgery experience more pain after it. A review conducted in 1993 looked at the impact of psychological preparation on outcomes after surgery. The term `psychological preparation' includes a range of techniques that aim to change what people think, how they feel or what they do. This 1993 review found that psychological preparation techniques reduced pain after surgery, improved behavioural recovery (how quickly people return to activities), decreased length of stay in hospital and reduced negative emotion (e.g. feelings of anxiety or depression). We aimed to carry out an up‐to‐date review using Cochrane methodology to learn whether there are helpful (or harmful) effects of psychological preparation for people undergoing surgery, and which outcomes (pain after surgery, behavioural recovery, negative emotion or length of stay) are improved.

Study characteristics

We included studies of adults who received planned surgery with general anaesthesia. We looked at seven psychological preparation techniques: procedural information (information about what, when and how processes will happen); sensory information (what the experience will feel like and what other sensations they may have, e.g. taste, smell); behavioural instruction (telling patients what they need to do); cognitive intervention (techniques that aim to change how people think); relaxation techniques; hypnosis; and emotion‐focused interventions (techniques that aim to help people to manage their feelings). The psychological preparation had to be delivered before surgery for the study to be included in the review. We included studies that looked at the effect of psychological preparation on pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay and negative emotion after surgery (within one month). Studies were included in the review up to the search date of 4 May 2014. We updated the search on 7 July 2015 and will incorporate the 38 studies found in this later search when the review is updated. We included 105 studies from 115 papers, with 10,302 participants taking part. Sixty‐one studies measured the outcome pain, 14 behavioural recovery, 58 length of stay and 49 negative emotion. In accordance with the review protocol, we did not record details about funding sources.

Key results

In this review we included 105 studies, which were reported in 115 papers. A total of 10,302 participants were randomized in these studies. For pain, length of stay and negative emotion we combined numerical findings from the studies. We found that psychological preparation before surgery seemed to reduce pain and negative emotion after the operation and may reduce the time spent in hospital by around half a day but the quality of the evidence was low. Also, the studies used many different psychological preparation techniques (often in different combinations) so it was not possible to discover which techniques were better. We could not statistically combine numerical findings for behavioural recovery because few studies provided sufficient details and studies used different ways of measuring how quickly people returned to usual activities. In reviewing the studies, we found that psychological preparation, in particular behavioural instruction, may have the potential to improve behavioural recovery. However, the quality of this evidence was very low. We looked at the effect of psychological preparation on pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay and negative emotion in this review and did not find evidence to suggest that psychological preparation might lead to harm in these outcomes. However, as we did not look at other outcomes it is possible that we did not identify potential harm.

Quality of the evidence

Many studies were poorly reported, so we could not be confident that findings were reliable. For this reason and because of the large variation in psychological techniques, types of surgery and measures used, we graded the quality of the evidence as `low' for the outcomes pain, negative emotion and length of stay; we cannot be confident that these techniques help patients to recover from surgery. For behavioural recovery, we further downgraded the quality of the evidence to `very low' because of problems with measurement and reporting of the outcome.

Summary of findings

Background

Many people experience anxiety and negative cognitions when approaching surgery (Mathews 1981). There is good evidence that how people think and feel before surgery affects their outcomes after surgery. Negative psychological factors such as anxiety, depression and catastrophizing have been found to predict postoperative pain (Arpino 2004; Bruce 2012; Granot 2005; Munafó 2001). Catastrophizing has been defined as "an exaggerated negative orientation toward noxious stimuli" (Sullivan 1995).

A range of mechanisms exist by which psychological variables could affect recovery after surgery. First, negative emotions can enhance pain sensations (Rainville 2005; van Middendorp 2010). Second, cognitions and emotions influence behaviour (for example doing physiotherapy exercises, taking analgesics) and are likely to influence pain and return to usual activities. Third, stress has been linked to the slower healing of wounds through psychoneuroimmunological mechanisms (mechanisms whereby psychology interacts with the nervous and immune systems) (Maple 2015; Marucha 1998; Walburn 2009). It is therefore likely that psychological interventions that reduce negative emotions such as anxiety, worry about surgery and perceptions of stress, or that change patients' recovery‐related behaviour, may lead to positive postoperative outcomes.

Psychological preparation for surgery has been demonstrated to improve outcomes. In a review and meta‐analysis (Johnston 1993), psychological preparation was found to be beneficial for a range of outcome variables that included negative affect, pain, pain medication, length of hospital stay, behavioural recovery, clinical recovery, physiological indices and satisfaction.

Since the 1993 review (Johnston 1993), this research field has continued to develop. Standards of conducting randomized controlled trials have improved, technology has advanced to permit more detailed bibliographic searching and new studies testing psychological preparation procedures have been published. The present review tested, using modern review techniques, analysis methods and a larger research base, a) whether there is evidence for beneficial (or harmful) effects of psychological preparation for surgery, and b) which outcomes of pain, behavioural recovery, length of stay and negative affect are improved (or worsened) following preparation.

Description of the condition

Surgery is carried out for a range of health conditions either as a diagnostic or treatment intervention. While surgery may lead to health improvements, it also negatively impacts on a range of health outcomes including pain, activity limitations and anxiety, at least in the short term (Johnston 1980).

Elective surgery differs from emergency surgery in that patients have time to prepare themselves and to be prepared for surgery. Preparation for emergency surgery is much more difficult to provide in a controlled manner and the effectiveness of such interventions is likely to differ because of that difference in context. Thus, emergency surgery should be considered separately and we only included participants undergoing elective surgery in this review.

Different psychological threats and coping mechanisms can be involved for the patient depending on whether procedures are undertaken using general anaesthetic or local anaesthetic. For example in some procedures that are performed under local anaesthetic the patients are required to be actively involved, and so effective preparation will have different components compared with preparation for a procedure where the patient is unconscious. Therefore, following Johnston 1993, we only included procedures involving general anaesthetic.

Description of the intervention

Psychological preparation incorporates a range of strategies designed to influence how a person feels, thinks or acts (emotions, cognitions or behaviours). Johnston 1993 found that the following types of intervention benefited patients, on at least one postoperative outcome: procedural information, sensory information, behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention, relaxation techniques, hypnosis and emotion‐focused interventions.

Procedural information

Procedural information describes the process the patient will undergo in terms of what will happen, when it will happen and how it will happen.

Sensory information

Sensory information describes the experiential aspects of the procedure, that is, what it will feel like and any other relevant sensations (for example taste, smell).

Behavioural instruction

Behavioural instruction consists of telling patients what they should do to facilitate either the procedure or their recovery from the procedure (Mathews 1984). For example a patient could be told how to use equipment, such as a patient‐controlled analgesia pump.

Cognitive interventions

Cognitive interventions aim to change how an individual thinks, especially about negative aspects of the procedure. Cognitive techniques include cognitive reframing and distraction. Cognitive reframing involves developing a different perspective that enables a positive or neutral rather than negative thought, for example focusing on the number of people who do well after a surgical procedure rather than the number who fare badly. Distraction leads to focusing thoughts on other things (and could include relaxation).

Relaxation techniques

These involve "systematic instruction in physical and cognitive strategies to reduce sympathetic arousal, and to increase muscle relaxation and a feeling of calm" (Michie 2008). Relaxation techniques can be used before surgery to reduce tension and anxiety and include progressive muscle relaxation (where each muscle group is tensed and then relaxed), simple relaxation (each muscle group is relaxed in turn), breathing techniques (for example the practice of diaphragmatic breathing) and guided imagery (for example imagining a pleasant, relaxing environment).

Hypnosis

A range of procedures are used for hypnotic induction, including suggestions to relax. During hypnosis "one person (the subject) is guided by another (the hypnotist) to respond to suggestions for changes in subjective experience, alterations in perception, sensation, emotion, thought or behavior" (APA 2005).

Emotion‐focused interventions

Emotion‐focused interventions aim to enable the person to regulate or manage their feelings or emotions. Emotion‐focused methods include: enabling the discussion, expression or acceptance of emotions; facilitating contextualization (putting emotions into context, e.g. of life, relationships, past experiences); and enabling the understanding of emotions (e.g. giving them meaning). In this review, if the focus of the intervention was to change how someone thinks, we coded it as a ‘cognitive intervention’.

How the intervention might work

Studies have shown that psychological preparation for surgery can have a beneficial effect upon a range of postoperative outcomes (Johnston 1993). Likely mechanisms for these processes vary depending upon the intervention used. Some intervention types focus on reducing negative emotions, such as anxiety, and negative thought processes. Providing procedural information is expected to reduce anxiety because it helps the patient to know what to expect when they undergo surgery. It reduces uncertainty, and ensures that concern is not caused by events that are part of normal hospital procedures (Ridgeway 1982). Similarly to providing procedural information, providing sensory information is expected to reduce anxiety by reducing the discrepancy between the sensation expected by the patient and the sensation actually experienced (Johnson 1973). For example, if a patient expects to experience discomfort after surgery in a particular bodily location, when this discomfort is experienced it is understood as being part of the normal surgical experience rather than an indication that something has gone wrong. Cognitive interventions aim to reduce negative emotions and thoughts related to the surgical process by either changing negative thoughts or refocusing attention elsewhere, and emotion‐focused interventions target an individual's emotions directly. Relaxation and hypnosis interventions aim to make an individual feel more relaxed, both psychologically and physiologically, and may effectively act as distraction techniques, so reducing both negative emotions and negative thoughts. As noted earlier, negative thoughts and emotions influence wound healing (Kiecolt‐Glaser 1998), perceptions of pain and also behaviour. Finally, behavioural instruction aims to directly influence behaviours that are important in enabling the surgical procedure to go well and to enhance recovery, for example teaching people how to manage their own analgesia, or instructing them as to when they should return to usual activities for optimal recovery.

Why it is important to do this review

Improving outcomes after surgery has a range of benefits both for the individual and for the healthcare service. Individuals will benefit from reduced postoperative pain and a quicker return to activity. Economic benefits include shorter stays in hospital, reduced use of pain medication and quicker return to work.

Objectives

To review the effects of psychological preparation on postoperative outcomes in adults undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthetic.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We included both published and unpublished randomized controlled trials (RCTs). We excluded quasi‐randomized trials. We included, and narratively described, cluster‐randomized controlled trials but did not include them in the meta‐analyses.

Types of participants

We included studies with adult participants (aged 16 years or older) undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthesia. If information about anaesthesia was not provided we contacted the study authors for confirmation. If no response was received, we took advice from a clinician (either a surgeon or anaesthesiologist) who assessed whether that type of surgery would usually be performed under general anaesthesia. We included or excluded studies on this basis. Some surgical procedures are carried out under either general or local anaesthesia (for example inguinal hernia repair surgery). We included studies containing a mixture of participants undergoing general and local anaesthesia but excluded studies where all participants underwent, or were expected to have undergone, local (or no) anaesthesia (with or without sedation).

We included studies of people who have received premedicative sedative prior to general anaesthesia. Different issues are encountered with children undergoing surgery (for example their developmental stage) and different psychological techniques are used (Johnston 1993). Studies tend to focus either on adults or children. We excluded participants aged less than 16 years from this current review.

We excluded studies focusing on patient groups with clinically diagnosed psychological morbidity. However, we did not exclude studies that included participants with mental disorders or subclinical symptoms co‐existing with the condition that led to the operation.

Types of interventions

Psychological preparation, including:

procedural information;

sensory information;

behavioural instruction;

cognitive interventions;

relaxation techniques;

hypnosis;

emotion‐focused interventions.

‘Psychological preparation’ was defined as interventions where the intervention was entirely provided before surgery (this preparation could include, for example, instructions for the participant for after surgery, but the implementation of the intervention had to be pre‐surgery). We were interested in the psychological content of the intervention in this review rather than how it is delivered. There are studies that compare different formats (e.g. leaflet versus video) or timings, but the actual content of the intervention is the same. We excluded these papers. Where the control group also received an element of preoperative preparation (for example, procedural information), the intervention group was required to receive that element beyond that received by the control group (for example, more detailed procedural information, or procedural information about additional aspects of surgery) to be considered as an `intervention'.

Types of outcome measures

We included studies that collected data on two primary and two secondary outcomes. We only included outcomes measured within 30 days/one month post‐surgery. We excluded studies that did not measure these outcomes for pragmatic reasons: because of the size of the review and available research team resources, including all studies measuring any outcome was not manageable (see Differences between protocol and review). Where repeated measurements of outcomes were taken postoperatively, we used the earliest measure for the main meta‐analysis. This is because, while the longest follow‐up is important for longer‐term recovery, it was likely that most studies would include short‐term outcome data but only a few would also include longer time frames.

Primary outcomes

1. Postoperative pain

1a. Postoperative pain intensity: there are a range of well‐used measures for pain and some studies report pain as an outcome using more than one measure. We extracted all reported postoperative pain outcomes from each study.

We used the following hierarchy when deciding which postoperative pain measure to use in the meta‐analysis:

the pre‐specified postoperative pain outcome (if given);

a visual analogue scale (VAS), for example from 0 to 100 (or 0 to 10);

McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ) (Melzack 1975) intensity rating, Present Pain Intensity;

other MPQ ratings: i) Pain Rating Index (weighted or unweighted), ii) Number of Words Counted;

Short Form‐36 (SF‐36) pain (Ware 2000);

Nottingham Health Profile pain (Hunt 1983);

other pain intensity scale.

We analysed pain at rest over pain at movement; moving in bed over pain when standing or walking; average pain over pain at rest or current pain; current pain over retrospective pain; worst pain over least pain or current pain. We prioritized sensory over affective measures, and self‐report over observer‐report pain measures.

1b. Proportion of participants in pain postoperatively as defined by the authors of included studies.

2. Behavioural recovery* (defined as: resumption of performance of tasks and activities).

Where multiple measures were used, we made the following decisions in prioritizing measures:

SF‐36 physical function (Ware 2000);

Nottingham Health Profile: Physical mobility (Hunt 1983);

Barthel Index (Mahoney 1965);

Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) functional status (Bellamy 1988).

Secondary outcomes

1 Negative affect*

Where multiple measures were used, we used the following hierarchy when deciding which measures to use in meta‐analysis:

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) state (Spielberger 1983);

STAI trait (Spielberger 1983);

Profile of Mood States (POMS) tension/anxiety (McNair 1971);

POMS global (McNair 1971);

Multiple Affect Adjective Check List (MAACL) Anxiety/fear (Zuckerman 1965);

MAACL total (Zuckerman 1965);

Mood Adjective Checklist (MACL) (Radloff 1968);

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety (Zigmond 1983);

HADS depression (Zigmond 1983);

General Health Questionnaire 28 (Goldberg 1978);

Perceived Stress Scale (Cohen 1983);

Hospital Anxiety Scale (Lucente 1972);

SF‐36 mental health (Ware 2000);

Nottingham Health Profile: Emotional Reaction (Hunt 1983);

Psychologic Global Well‐being Scale (Dupuy 1984);

BSKE (EWL) (Befindlichkeitsskalierung durch Kategorien und Eigenschaftswörter): Psychological Global Well‐being/mood (Janke 1994);

Structured interview: Modified Present State Examination schedule (Tait 1982) and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition (DSM‐III) (APA 1980).

2. Length of stay in hospital (days)

*For the outcomes of behavioural recovery and negative affect we included only studies that used measures with published psychometric properties, including reliability and validity. We recorded the timing of outcome assessment.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL 2014, Issue 5); MEDLINE (Ovid SP) (1950 to 4 May 2014); EMBASE (Ovid SP) (1982 to 4 May 2014); PsycINFO (Ovid SP) (1982 to 4 May 2014); CINAHL (EBSCOhost) (1980 to 4 May 2014); Dissertation Abstracts and ISI Web of Science (1946 to 4 May 2014). We reran the search on 7 July 2015; the additional studies identified (after screening titles and abstracts to exclude any obviously irrelevant studies) are listed under Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

We used the following subject search terms for searching the databases:

`psychological preparat*', education, information, instruction, cognitive interven*, `cognitive behavio?ral therapy', `cognitive therapy', `behavio*ral therapy', hypnosis, relaxation, guided imagery, surgery, operat*, surgical procedure, general an*esthetic, elective surgery, cholecystectomy, hysterectomy, hernia repair, herniorrhaphy, hernioplasty, joint replacement surgery, arthroplasty.

We combined our subject search terms with the Cochrane highly sensitive search strategy for identifying RCTs as suggested in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). The full search strategies are provided in the Appendices (Appendix 1 for CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library; Appendix 2 for MEDLINE (OvidSP); Appendix 3 for EMBASE (OvidSP); Appendix 4 for CINAHL (EBSCOhost); Appendix 5 for ISI Web of Science).

Searching other resources

We searched the reference lists of relevant papers for additional sources where references were provided in the English language. We contacted the authors of relevant studies to identify unpublished studies and dissertations.

We did not limit the search by language or publication status. Where papers were in a non‐English language, we asked a speaker of that language to screen the paper. A member of the review team went over the screening, checking each decision with the screener's description of what happened in the paper. Where the paper was deemed to fit the review criteria, if a member of the review team spoke the language, that individual extracted the data, with a second member of the review team (RP) then checking, by discussion with the first extractor, that decisions made and data extracted were correct. Where no member of the review team spoke the language of the paper, we gained English translations and extracted data in the same way as for English language papers.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

One review author (RP) checked titles and abstracts of retrieved studies to exclude obviously irrelevant reports. A small, random sample was double‐checked by a second researcher (research assistant Yvonne Cooper, or authors MU and JB). Where the title and abstract indicated that a paper had the potential to fit inclusion criteria, copies of the trial were independently assessed for inclusion by two researchers (RP and one other member of the team: research assistant Louise Pike or authors MU, AM, CV, JB, NS, MJ or LBD). We resolved any disagreements by discussion with a third researcher (a member of the authorship team who had not assessed the paper).

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (RP and either MU, AM, JB, CV, MJ, JB, NS or research assistant Louise Pike) independently carried out data extraction using a data extraction form (see Appendix 6). We resolved any disagreement by discussing the matter with a third author (an author who had not previously extracted data from that paper). We extracted the following data:

Study participants: age, gender, total number of participants, location, setting, surgery type.

Study methods: study design, study duration.

Interventions: theoretical nature of intervention, number of intervention groups, specific intervention, intervention details (including delivery method), integrity of intervention, timing of intervention, control groups, usual care description, adherence to intervention and control, attrition rate, loss to follow‐up rate.

Outcomes: outcomes and time points a) collected, and b) reported; outcome definition, author's definition of outcome; measurement tool details (including, for example, upper and lower limits, whether high or low score is good outcome).

Results: number of participants allocated to each intervention group, missing participants, means, standard deviations, proportions, estimate of effect with confidence interval, P value, subgroup analysis information when appropriate (e.g. monitors and blunters (information seekers or avoiders), see Miller 1983).

Study withdrawals or losses to follow‐up.

We described interventions according to whether they contained procedural information, sensory information, behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention, relaxation techniques, hypnosis or emotion‐focused interventions. We coded preparation received by control group participants in the same way.

We (RP) contacted study authors for additional data. We used a two‐stage approach. A first email asked for key information: whether (if not stated) general anaesthesia was used, whether they measured any outcomes not reported in the paper and whether they knew of other (e.g. unpublished) studies. We also asked the study authors if they would be happy for us to contact them with additional questions. If the study authors replied and were happy for us to ask them for further information, we sent them a more detailed email if further information was required.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (RP and either MU, AM, JB, CV, MJ, JB, NS or research assistant Louise Pike) independently assessed studies' risk of bias using the tool described in Chapter 8 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). This tool requires the review authors to assess risk of bias in the following domains: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias. In addition, the review authors noted whether the study used intention‐to‐treat analysis methods (Hollis 1999) (see Appendix 7 for table). We used a single criterion to classify studies as following the intention‐to‐treat principle: participants needed to be kept in the intervention groups to which they were randomized, regardless of the intervention they received (i.e. analysis was not according to per‐protocol or treatment‐received).

Studies with high or unclear risk of bias were to be given reduced weight in the meta‐analysis compared with studies at low risk of bias. We anticipated that meta‐analysis would be restricted to studies at low (or lower) risk of bias, as per Section 8.8.3.1 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). We planned to conduct sensitivity analyses to determine whether excluding studies at a high risk of bias affected the results but we did not do so because of the low number of studies deemed to be at `low risk' of bias (see Risk of bias in included studies). We did not expect blinding of participants or personnel administering the intervention because of the interactive nature of the interventions. We described any blinding that was carried out, and rated the risk of bias following the Cochrane guidelines, but high risk of bias for performance bias was not seen to diminish the quality of the paper. We recorded the adequacy of the blinding of outcome assessors (returning data by post was deemed acceptable).

Measures of treatment effect

We performed meta‐analyses according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). For dichotomous variables, we planned to calculate risk ratios (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). For continuous data where each study used the same units (i.e. for length of stay), we calculated mean differences for each study and their 95% CIs.

For the postoperative pain and negative affect outcomes a variety of scales were used so we calculated a standardized effect size ‐ the standardized mean difference (SMD), or Hedges' g. We used final scores as standard. However, some studies only reported mean (SD) change from baseline; for these studies we used the difference in mean change scores as the effect size. If no continuous postoperative pain data were available but dichotomous data were presented, we used the log odds ratio instead as the effect size. It was only necessary to do this for one study (Coslow 1998).

If necessary, we reversed the sign of the effect size so that values below zero always indicated that the intervention group was favoured.

Unit of analysis issues

We included only patient‐randomized studies in the meta‐analyses. We reported the results of cluster‐randomized studies as part of the narrative review.

Dealing with missing data

If any necessary data were missing, when we contacted authors about their studies we specifically asked them about the missing data (see Data extraction and management for procedure taken with contacting authors). Missing standard deviations (SD) was a common situation in this review. We were able to calculate (or estimate) standard deviations in a variety of ways. These included calculating the SD from the standard error of the mean (SEM), 95% confidence intervals or from t or F statistics. If the majority of studies in a meta‐analysis still had missing SDs we did not impute these. Otherwise, we used an unweighted average of SDs from other studies in the review. We used identical imputed values for both intervention and control groups.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We considered and tested heterogeneity between trials, where appropriate. To test for gross statistical heterogeneity between all trials, we used Chi2 tests for heterogeneity and quantified heterogeneity using the I2 statistic (Higgins 2011).

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not plan to assess reporting biases using, for example, funnel plots, because of the probable heterogenous nature of the studies and probable small number of studies appropriate for comparison. However, there proved sufficient studies to examine funnel plots for the overall, `omnibus' analyses.

Data synthesis

We entered quantitative data into Cochrane RevMan 5.3 software and, where appropriate, statistically aggregated the data. We pooled data for all outcomes using an inverse variance approach. We used random‐effects models for all analyses because of expected heterogeneity in interventions and outcomes.

Where it was not possible to pool data, or if summary measures were medians (with range or interquartile range (IQR)), we presented these details in table format and discussed the results.

For each outcome we performed an initial `omnibus' meta‐analysis. We use the term `omnibus' to describe an overall analysis, including all of the psychological preparation interventions (whatever the types of interventions used) and compared these (any psychological preparation intervention) versus controls.

Many studies in the review contained two or more randomized arms. We classified the interventions in each arm separately. To avoid double counting of control groups, for the omnibus analysis we pooled the data in all intervention arms using the standard pooling formula and classified the study as administering any of the interventions included in any of the pooled arms.

The only non‐standard design (i.e. non individually randomized controlled trial) that met the inclusion criteria was a clustered randomized controlled trial design. We narratively synthesized these studies ‐ they were not included in meta‐analysis.

`Summary of findings' table

We included each outcome (postoperative pain, behavioural recovery, negative affect and length of stay) in a `Summary of findings' table (Table 1). For each outcome, the table indicated the effect for the control group and corresponding effect for the intervention group as appropriate, with the number of studies and participants included in analyses. We assessed the quality of the body of evidence for each outcome (postoperative pain, behavioural recovery, negative affect, length of stay) using the GRADE approach, as described in Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2011). As we only included RCTs, our start point for grading the evidence was `high quality'. We downgraded by one level for serious factors, and two levels for very serious factors in: limitations in design or implementation of studies (risk of bias); indirectness of evidence; heterogeneity or inconsistency of results; imprecision of results; or high likelihood of publication bias.

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Any intervention compared to control for adults undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia.

| Any psychological preparation intervention compared to control for adults undergoing surgery under general anaesthesia | ||||||

|

Patient or population: adults undergoing elective surgery under general anaesthesia Setting: pre‐surgical contexts (typically hospitals/preoperative clinic settings); setting was not limited by country/language/type of hospital Intervention: psychological preparation interventions presented to participants preoperatively; interventions contained one or more of the following components: procedural information; sensory information; behavioural instruction; cognitive intervention; relaxation techniques; hypnosis; emotion‐focused intervention Comparison: control group (typically standard care and/or attention control) | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Any intervention | |||||

| Postoperative pain ‐ measured with a range of tools and placed on a standardized scale Higher scores = higher pain |

‐ | The mean pain in the intervention group was 0.2 (95% confidence interval 0.35 to 0.06) standard deviations lower | ‐ | 2713 (38 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW1 | ‐ |

| Behavioural recovery ‐ measured with a range of tools | Insufficient data were available to calculate standardized scores | Findings suggested that psychological preparation has potential to improve behavioural recovery outcomes, but no clear conclusions could be reached | ‐ | 1441 participants were randomized (14 RCTs) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ VERY LOW2 | Data from studies were not combined in meta‐analysis because of a low number of studies containing suitable data and a wide range of outcome measures |

| Length of stay in hospital (days) | The mean length of stay for the control groups ranged from 2.11 to 18.6 days | The mean length of stay (days) in the intervention group was 0.52 days fewer (95% confidence interval 0.82 to 0.22) | ‐ | 3313 (36 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW3 | ‐ |

| Negative affect ‐ measured with a range of tools and placed on a standardized scale Higher scores = higher negative affect (e.g. more anxiety) |

‐ | The mean negative affect in the intervention group was 0.35 (95% confidence interval 0.54 to 0.16) standard deviations lower | ‐ | 2496 (31 RCTs) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ LOW4 | ‐ |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RCT: randomized controlled trial | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1Many studies reported insufficient methodological details to ascertain risk of bias (rated `serious', see Figure 1), and heterogeneity was high (71%, also rated `serious'). We therefore downgraded the overall quality of evidence by two points.

2We downgraded the quality of evidence as `risk of bias' was rated as `very serious' ‐ there were a high proportion of `uncertain' ratings for risk of bias categories, and the number of studies with robust measures meeting our inclusion criteria and reporting suitable data for meta‐analysis was low. We made a further downgrade for high heterogeneity (treated as `serious'). We therefore downgraded the overall quality of evidence by three points.

3Many studies reported insufficient methodological details to ascertain risk of bias (rated `serious', see Figure 1), and heterogeneity was high (74%, also rated `serious'). We therefore downgraded the overall quality of evidence by two points.

4Many studies reported insufficient methodological details to ascertain risk bias (rated `serious', see Figure 1), and heterogeneity was high (81%, also rated `serious'). We therefore downgraded the overall quality of evidence by two points.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We planned to carry out subgroup analyses to compare trials of high methodological quality with trials of low methodological quality but did not do so because of the small number of studies judged to be at `low risk' of bias (see Risk of bias in included studies).

Following the omnibus analysis we carried out additional separate meta‐analyses corresponding to the seven intervention categories (procedural information, sensory information, behavioural instruction, cognitive interventions, relaxation techniques, hypnosis and emotion‐focused interventions). We divided studies into those with that intervention category only (referred to as `pure' studies, e.g. procedural information only) and those including that intervention category in combination with other intervention types (referred to as `mixed', e.g. procedural information + sensory information + behavioural instruction) and conducted subgroup analyses so that the effect of both all studies including procedural information and of `pure' procedural information studies could be evaluated. For multi‐arm studies, by including only data from relevant arms we were often able to include different data to those included in the omnibus analysis.

Sensitivity analysis

Jüni recommends consideration of the important quality components of a given meta‐analysis when conducting sensitivity analyses (Jüni 2001). We planned to perform sensitivity analyses to evaluate the effect on the overall result of removing trials with low methodological quality (as identified using the Cochrane tool) (Appendix 6), but did not do so because of the small number of studies judged to be at low risk of bias (see Risk of bias in included studies). Low methodological quality studies were those where: a) sequence generation or allocation concealment was judged as high risk or unclear, b) there was no or unclear blinding of outcome assessors, c) incomplete outcome data were not adequately addressed (assessed as high risk or unclear), d) the study appeared to be at risk of selective outcome reporting (high risk or unclear), d) the study did not appear to have been conducted according to intention‐to‐treat (i.e. it was not clear that participants were kept in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of the intervention they received) (high risk or unclear), d) the study appeared to be at risk of other sources of bias (high risk or unclear).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

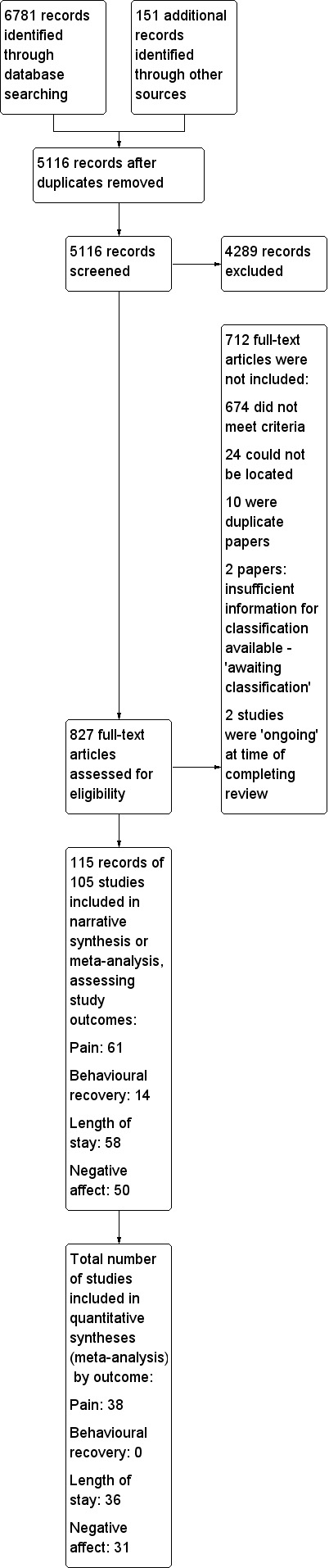

Electronic searches identified 6781 papers; we identified an additional 151 papers through contact with authors and screening reference lists. We removed 1816 duplicate papers, leaving 5116 whose titles and abstracts we screened for broad relevance. This led to us retrieving 827 papers for full screening. We were unable to locate 24 references (2.9% of papers to be retrieved for full screening). See Figure 2 for the flow chart of studies included and excluded from the review.

2.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

We included 105 studies (from 115 papers) in which 10,302 participants were randomized (see Characteristics of included studies). Sixty‐one papers measured the outcome postoperative pain, 58 length of stay, 50 negative affect and 14 behavioural recovery. We attempted to contact all authors, with the exception of five studies' authors where the study reports were retrieved late in the review process (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Done 1998; McGregor 2004; Rajendran 1998; Rosenfeldt 2011). The publication dates of the included studies ranged from 1970 to 2014 and studies were conducted in a wide range of countries (36 in the USA, 13 in the UK, nine in Canada, seven in China, six in Australia, five in the Netherlands, four in Germany, three in Sweden, and one or two studies in each of: Austria, Brazil, Denmark, Egypt, France, India, Iran, Ireland, Italy, New Zealand, Nigeria, Romania, Serbia, Singapore, Spain, Switzerland, Taiwan and Turkey).

The study participants underwent a wide range of surgical procedures. Twenty‐seven studies investigated participants undergoing cardiothoracic surgery (including 17 exclusively containing participants undergoing coronary artery bypass graft surgery). Hip or knee joint surgery was examined in 22 studies (four knee replacement only, 10 hip replacement only, eight both hip and knee replacement surgery). Seven studies considered cholecystectomy, seven hysterectomy and two breast surgery. The following procedures were considered in a single study each: urinary diversion surgery, colorectal resection, laparoscopic tubal ligation, minimally invasive radio‐guided parathyroidectomy, rectal cancer surgery, periodontal surgery, inguinal hernia and gastric bypass surgery. Thirty‐one studies addressed a mixture of procedures and one study did not state the surgical procedure(s).

The included studies used a range of intervention components, and intervention content was rarely `pure', consisting of a single intervention. Procedural information was reported in 59 interventions (`pure' procedural information content in eight), sensory information in 38 (`pure' sensory information in one), behavioural instruction in 71 (`pure' in 28), cognitive interventions in 27 (`pure' in eight), relaxation techniques in 35 (`pure' in 13), hypnosis in six (`pure' in one) and emotion‐focused interventions in 12 (`pure' in one). Studies generally contained fairly small sample sizes.

We found that control group content was generally poorly reported. Pure procedural information content was reported in 17 control groups, pure behavioural instruction in 11 and combinations of interventions in 23 studies. Fifty‐six studies provided insufficient information for us to categorize control content ‐ for example, authors frequently described the control group as consisting of `usual care' without describing what usual care was. It is highly likely that intervention content is missing from these descriptions because if participants were provided with absolutely no procedural information or behavioural instruction prior to their surgery they would not know when to arrive for their surgery or what to do (e.g. when to fast prior to their anaesthetic).

As per our protocol (Powell 2010), we did not extract funding sources from papers in this review.

Excluded studies

We excluded 674 papers on full screening of retrieved papers. Details of 27 key excluded papers are provided (Anderson 1987; Blay 2005; Boore 1978; Burton 1991; Burton 1994; Croog 1994; Domar 1987; Enqvist 1995; Eremin 2009; Huang 2012; Johnson 1978a; Lengacher 2008; Liu 2013; Manyande 1995; Manyande 1998; Mitchell 2000; Montgomery 2002; Montgomery 2007; Sheard 2006; Shelley 2009; Stergiopoulou 2006; Sugai 2013; Surman 1974; Timmons 1993; Voshall 1980; Wang 2002; Wells 1986). For further details of the excluded studies see the Characteristics of excluded studies.

Ongoing studies

We did not include two papers, Jong 2012 and Hansen 2013, as the research was complete but authors were reluctant to share study details with us prior to publication.

Studies awaiting classification

On full screening of retrieved papers in May 2014, two provided insufficient information to determine whether or not they met the review's inclusion criteria and our attempts to contact the authors for further information were not successful (Johansson 2007; Lookinland 1998).

We reran the searches in July 2015. These searches identified a further 753 papers. On removing duplicates across databases, 614 papers remained. We checked these references for overlap with searches previously conducted and identified a further 96 duplicates. These searches therefore identified 518 new papers. RP screened the titles and abstracts of these papers for relevance (with JB checking a randomly selected 5% of titles and abstracts); 482 papers were excluded. The remaining 36 papers appear to potentially have relevance and should be retrieved and screened in detail when this review is updated (Akinci 2015; Angioli 2014; Attias 2014; Bergin 2014b; Calsinski Assis 2014; Chevillon 2014; Chow 2014; Dathatri 2014; Eckhouse 2014; El Azem 2014; Ellett 2014; Foji 2015; Fraval 2015; Furuya 2015; Gade 2014; Gillis 2014; Gyulaházi 2015; Hansen 2015; Henney 2014; Heras 2014; Hoppe 2014; Huber 2015; Johansson 2007; Kol 2014; Lai Ngor 2014; Louw 2014; Mohammadi 2014; Novick 2014; Paul 2015; Rolving 2014; Saleh 2015; Shahmansouri 2014; Umpierres 2014; Van Acker 2014; West 2014; Würtzen 2015; Xin 2015). Details of these papers can be found in Characteristics of studies awaiting classification.

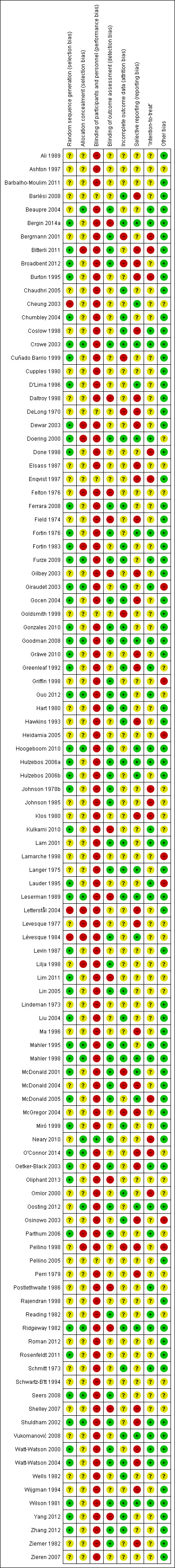

Risk of bias in included studies

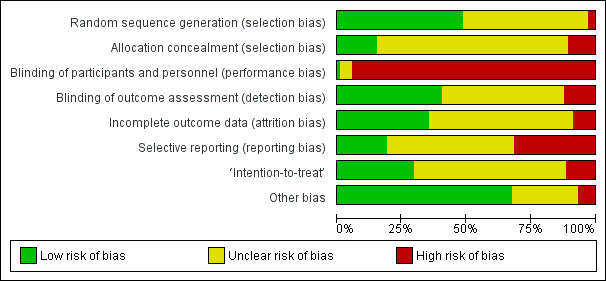

Details of `Risk of bias' assessments for each study are provided in Characteristics of included studies, with summaries across studies being presented in Figure 1 and Figure 3. We did not expect many studies in this review to be rated as `low risk' for performance bias. However, even ignoring this category, only three studies received `low risk' ratings on all other items (Crowe 2003; Goodman 2008; Mahler 1998). We therefore did not carry out the planned sensitivity analyses to compare meta‐analyses including only high quality, `low risk' studies with analyses including all available data, nor the planned subgroup analyses to compare findings of high quality, `low risk' studies with findings of low quality, `high risk' studies.

1.

`Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

3.

`Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

Allocation

As shown in Figure 1, we rated very few studies as ‘high risk’ for random sequence generation. This is because, following our protocol (Powell 2010), we only included RCTs ‐ where a non‐random approach was described (such as alternation), or where there was no mention of randomization in the study description, studies were excluded. This meant that studies that could be rated as `high risk' would usually be excluded from the review. Despite this inclusion criterion, the randomization procedure was sufficiently described to rate the study as ‘low risk of bias’ in only about half of studies (51 of 105, see Figure 3) – giving insufficient information to ascertain the procedure used for allocation was common.

Clear descriptions of allocation concealment were even more rare, with only 16 (of 105) studies being judged as `low risk of bias' (Beaupre 2004; Crowe 2003; Furze 2009; Giraudet 2003; Goodman 2008; Guo 2012; Hoogeboom 2010; Leserman 1989; Mahler 1995; Mahler 1998; Neary 2010; O'Connor 2014; Oosting 2012; Ridgeway 1982; Schwartz‐B'tt 1994; Shuldham 2002) – this was an aspect that was simply not mentioned in most studies. Awarding the designation of `low risk' tended to depend on information that we were able to gain directly from authors themselves.

Blinding

Studies' poorest risk of bias ratings were for performance bias: blinding of participants and personnel. We rated most studies in the review as being at ‘high risk of bias’ in this category. We anticipated this and did not expect to see blinding of participants or of the personnel administering the intervention because many psychological interventions are interactive in nature. It was therefore rare to find a study where the person administering the intervention could be blind to the participant’s group allocation and, if participants were fully informed about the nature of the study, they would also tend not to be blinded to treatment condition. One study did report blinding of both participants and personnel, using an intervention delivered via a website (Neary 2010). Studies rated as `unclear' for performance bias (n = 5: Barlési 2008; DeLong 1970; Enqvist 1997; Goldsmith 1999; Pellino 2005) used a limited range of intervention formats, administered on paper (Barlési 2008), by audiorecording (DeLong 1970; Enqvist 1997), information on paper and tape (Pellino 2005), or via a website (Goldsmith 1999).

Blinding of outcome assessment (to avoid detection bias) was feasible in the types of studies we assessed – by ensuring that the person administering postoperative measures was blind to allocation. However, this was frequently not reported, allowing us to rate 42 (of 105) studies as `low risk of bias' (Beaupre 2004; Bergmann 2001; Bitterli 2011; Broadbent 2012; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Ferrara 2008; Fortin 1976; Furze 2009; Gocen 2004; Gonzales 2010; Goodman 2008; Griffin 1998; Guo 2012; Hart 1980; Hoogeboom 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Johnson 1978b; Johnson 1985; Lam 2001; Langer 1975; Lévesque 1984; Lilja 1998; Lin 2005; Mahler 1995; Mahler 1998; McDonald 2001; McDonald 2004; McDonald 2005; Neary 2010; Oetker‐Black 2003; Oosting 2012; Parthum 2006; Reading 1982; Seers 2008; Shuldham 2002; Watt‐Watson 2000; Watt‐Watson 2004; Wilson 1981; Zhang 2012; Ziemer 1982).

Incomplete outcome data

Attrition was frequently poorly reported in the studies, leading to ratings of `unclear risk of bias'. Sufficient information was provided, demonstrating good practice, in 37 `low risk' studies (Barlési 2008; Bergin 2014a; Chaudhri 2005; Chumbley 2004; Coslow 1998; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Ferrara 2008; Fortin 1983; Furze 2009; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Gonzales 2010; Goodman 2008; Greenleaf 1992; Guo 2012; Hart 1980; Hawkins 1993; Hulzebos 2006a; Lam 2001; Langer 1975; Leserman 1989; Lin 2005; Liu 2004; Mahler 1995; Mahler 1998; Miró 1999; Omlor 2000; Osinowo 2003; Ridgeway 1982; Schmitt 1973; Vukomanović 2008; Watt‐Watson 2004; Wells 1982; Wilson 1981; Yang 2012; Zhang 2012).

Selective reporting

The proportion of studies rated as `low risk' for selective reporting was low (20 of 105) (Bergin 2014a; Cheung 2003; Crowe 2003; D'Lima 1996; Doering 2000; Fortin 1976; Goodman 2008; Hoogeboom 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Hulzebos 2006b; Langer 1975; Leserman 1989; Levesque 1977; Mahler 1998; McDonald 2001; McDonald 2005; Oosting 2012; Ridgeway 1982; Vukomanović 2008; Wilson 1981). Thirty‐three were designated `high risk'. This may reflect our strict application of the Cochrane guidelines (Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, Table 8.5.d.; Higgins 2011), which stated that for a judgement of `low risk' either "the study protocol is available and all of the study's pre‐specified (primary and secondary) outcomes that are of interest in the review have been reported in the pre‐specified way" or "the study protocol is not available but it is clear that the published reports included all expected outcomes, including those that were pre‐specified (convincing text of this nature may be uncommon)". It was extremely rare to find studies with reference to protocol documents, and only a very small number of trials had been registered. To provide a rating of `low risk' we tended to be dependent on authors responding to our queries as to whether any outcomes were measured but not reported.

Other potential sources of bias

We evaluated studies for analysis according to the principles of intention‐to‐treat (whether participants were analysed in the group to which they were allocated, regardless of the intervention they received). This was often not reported, leading to the evaluation of 31 studies as `low risk of bias' (Beaupre 2004; Bergin 2014a; Coslow 1998; Crowe 2003; Doering 2000; Fortin 1976; Furze 2009; Giraudet 2003; Goodman 2008; Greenleaf 1992; Guo 2012; Hoogeboom 2010; Hulzebos 2006a; Kulkarni 2010; Lam 2001; Lauder 1995; Leserman 1989; Mahler 1995; Mahler 1998; Oetker‐Black 2003; Oosting 2012; Parthum 2006; Postlethwaite 1986; Reading 1982; Ridgeway 1982; Schmitt 1973; Shuldham 2002; Vukomanović 2008; Watt‐Watson 2000; Watt‐Watson 2004; Wilson 1981), 12 as `high risk' and the remainder as `unclear'.

Most studies were not found to have additional sources of bias, with concerns being raised for seven studies rated as `high risk' and 27 as `unclear'.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

A summary of key findings, with quality gradings, is provided in Table 1.

Findings by outcome

Primary outcomes

1.Postoperative pain

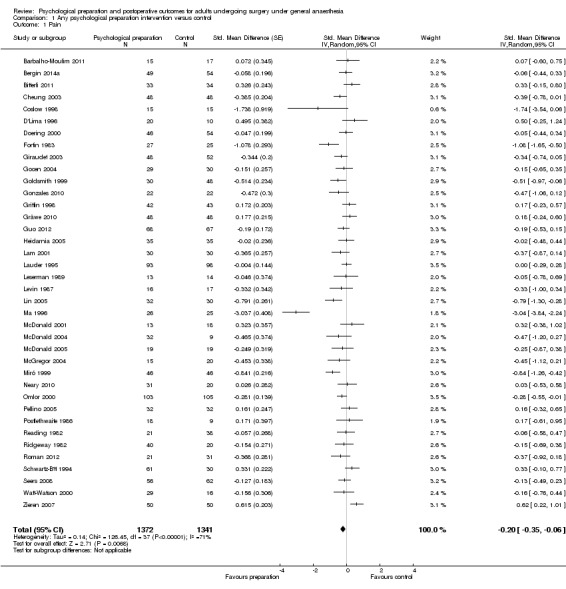

Studies included in meta‐analysis

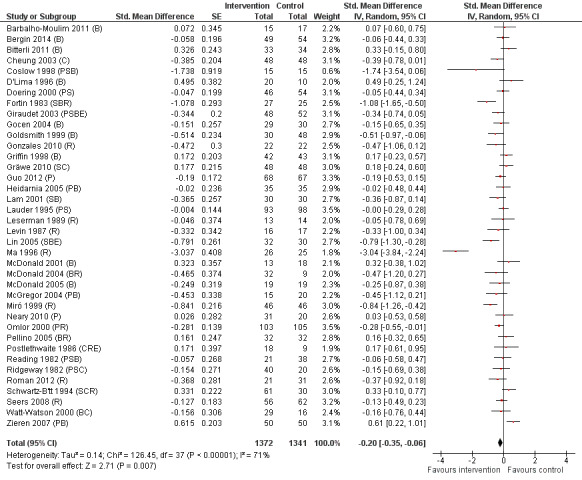

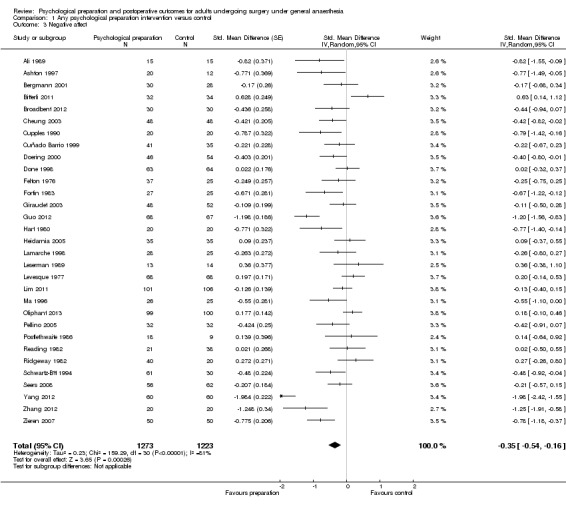

Sixty‐one studies assessed the outcome postoperative pain. It was possible to include data for 38 studies (36% of 105 studies) (Barbalho‐Moulim 2011; Bergin 2014a; Bitterli 2011; Cheung 2003; Coslow 1998; D'Lima 1996; Doering 2000; Fortin 1983; Giraudet 2003; Gocen 2004; Goldsmith 1999; Gonzales 2010; Gräwe 2010; Griffin 1998; Guo 2012; Heidarnia 2005; Lam 2001; Lauder 1995; Leserman 1989; Levin 1987; Lin 2005; Ma 1996; McDonald 2001; McDonald 2004; McDonald 2005; McGregor 2004; Miró 1999; Neary 2010; Omlor 2000; Pellino 2005; Postlethwaite 1986; Reading 1982; Ridgeway 1982; Roman 2012; Schwartz‐B'tt 1994; Seers 2008; Watt‐Watson 2000; Zieren 2007), with analysis of 2713 participants' data (26% of 10,302 participants randomized across all studies), in the omnibus meta‐analysis, which included studies comparing any intervention versus control (Analysis 1.1; Figure 4). As a variety of scales were used to measure postoperative pain, we used standardized scores to pool data using the SMD (Hedges' g). Higher scores indicate higher pain; effect scores below zero indicate that the intervention group had lower pain. Overall, the pooled effect size (SMD) was ‐0.20 (95% confidence interval (CI) ‐0.35 to ‐0.06), suggesting a statistically significant effect in favour of the intervention groups. There were, however, high levels of statistical heterogeneity between studies (I2 statistic = 71%).

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Any psychological preparation intervention versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

4.

Pain (any psychological preparation intervention versus control). B: behavioural instruction; C: cognitive interventions; E: emotion‐focused interventions; H: hypnosis; P: procedural information; R: relaxation; S: sensory information.

One study appeared to be an outlier (Ma 1996). We assumed statistics in the paper to represent mean and standard deviation as the notation "x bar +/‐ s" was used but this was not explicitly stated and it is possible that `s' represented standard error. Excluding this study did not affect the interpretation of the outcome, but reduced the observed statistical heterogeneity (I2 statistic = 53%). Excluding the single study where an effect size had been derived from categorical data, Coslow 1998, also had no effect on the results.

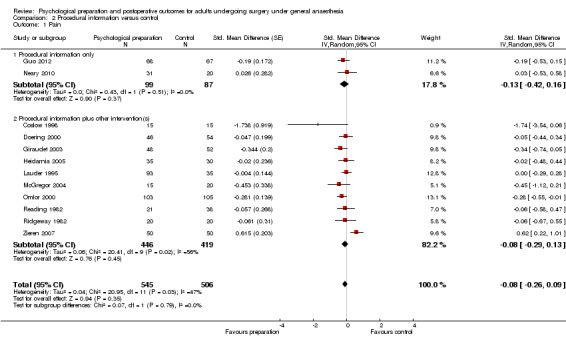

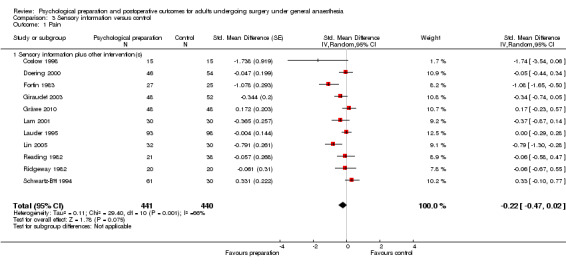

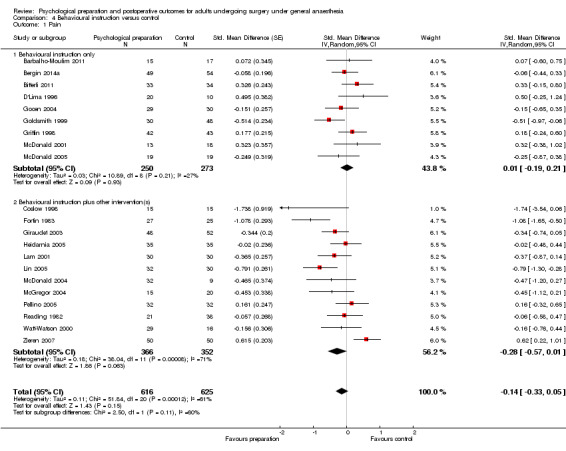

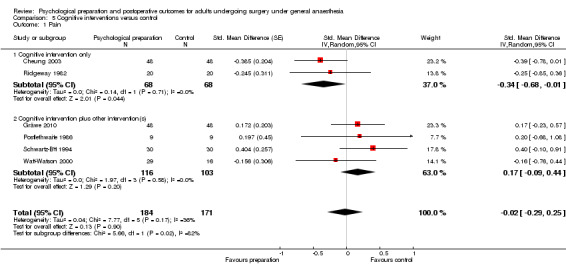

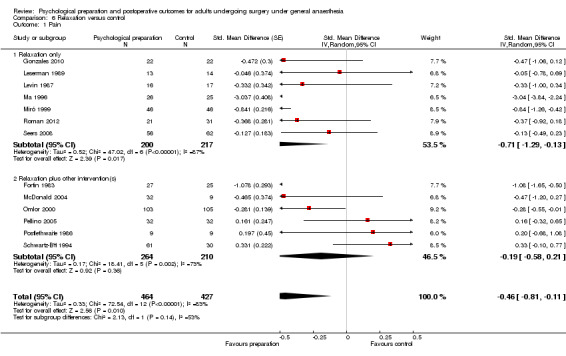

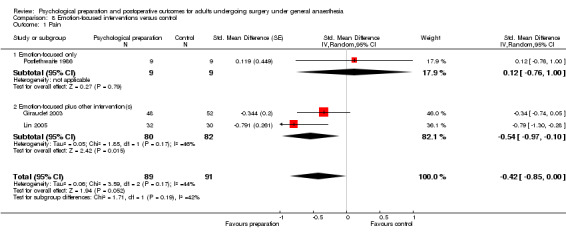

Subsequent forest plots show the results for the individual types of intervention (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 3.1; Analysis 4.1; Analysis 5.1; Analysis 6.1; Analysis 8.1; no studies used the intervention hypnosis). Most studies included more than one intervention type and, except for behavioural instruction and relaxation, there were no more than two `pure' studies that included just that particular intervention type. This makes it very difficult to separate the effect of a particular intervention category from other types of intervention also administered. For most intervention types the pattern of results was similar to the omnibus analysis and results for `pure' and `mixed' studies were also similar. The analyses for behavioural instruction showed a somewhat different pattern, however, with a relatively consistent effect size for the `pure' behavioural instruction studies suggesting no difference between intervention and control (SMD 0.01, 95% CI ‐0.19 to 0.21, I2 statistic = 27%). The meta‐analysis results for individual intervention types were statistically significant for the meta‐analysis of the two studies including cognitive intervention (Cheung 2003; Ridgeway 1982; SMD ‐0.34, 95% CI ‐0.68 to ‐0.01, I2 statistic = 0%; Analysis 5.1.1) and the meta‐analysis of seven `pure' relaxation studies (Gonzales 2010; Leserman 1989; Levin 1987; Ma 1996; Miró 1999; Roman 2012; Seers 2008; SMD ‐0.71, 95% CI ‐1.29 to ‐0.13, I2 statistic = 87%; Analysis 6.1.1). No data for studies investigating postoperative pain after hypnosis could be included in the meta‐analyses. The funnel plot showed no clear evidence of publication bias.

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Procedural information versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Sensory information versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Behavioural instruction versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Cognitive interventions versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

6.1. Analysis.

Comparison 6 Relaxation versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

8.1. Analysis.

Comparison 8 Emotion‐focused interventions versus control, Outcome 1 Pain.

Studies not included in meta‐analysis

Twenty‐three studies addressing the postoperative pain outcome did not contain data appropriate for meta‐analysis (Chumbley 2004; Daltroy 1998; Dewar 2003; Enqvist 1997; Ferrara 2008; Field 1974; Gilbey 2003; Hawkins 1993; Johnson 1978b; Johnson 1985; Kulkarni 2010; Lilja 1998; Liu 2004; Oetker‐Black 2003; Parthum 2006; Perri 1979; Shelley 2007; Shuldham 2002; Vukomanović 2008; Watt‐Watson 2004; Wells 1982; Wijgman 1994; Ziemer 1982) (Table 2). Three of these were not eligible for meta‐analysis as they reported cluster‐randomized trials (Chumbley 2004; Parthum 2006; Vukomanović 2008). Median scores were provided in two studies (Kulkarni 2010; Wijgman 1994); most studies in this group lacked sufficient detail to be entered into meta‐analysis.

1. Findings of studies that examined the outcome pain but could not be included in meta‐analyses.

| Author, year | Surgery type and sample size (randomized) | Intervention categories |

Pain measure(s) The first measure listed is that prioritized in this review |

Pain findings (as available) |

| Chumbley 2004 | Mixed: surgeries that would receive PCA routinely N = 246 |

Intervention 1: Behavioural instruction (delivered in leaflet) Intervention 2: Behavioural instruction (delivered in interview) |

1) Visual analogue scale (VAS) days 1 to 5 post‐surgery 2) Word rating on 5‐point scale; days 1 to 5 post‐surgery |

Cluster‐randomized VAS day 1 postoperatively mean (95% CI): Control: 3.7 (2.93 to 4.45); Intervention 1: 2.8 (2.04 to 3.56); Intervention 2: 3.2 (2.43 to 6.21). ANOVA, repeated measures: for VAS pain scores, between‐groups effect: F = 1.88, P value = 0.23 |

| Daltroy 1998 | Total hip or knee arthroplasty N = 12 |

Procedural and sensory information | Day 4 post‐surgery Measure not clearly described, assume same as preoperatively: mean of 3 x 5‐point scales assessing pain at night, resting and when active |

Intervention did not affect pain in general linear model (P value = 0.16) |

| Dewar 2003 | Mixed surgeries N = 254 |

Procedural information, behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention, relaxation | Evening after surgery (day 0) Brief Pain Inventory: numerical rating scale from 0 to 10 |

Control n = 118; intervention n = 104 No significant difference |

| Enqvist 1997 | Breast reduction N = 50 |

Relaxation, hypnosis | Days 1 to 5 post‐surgery, measured with `10‐degree VAS’. Not clear exactly what was asked, or if measured once in this period or daily | Control n = 25; intervention n = 23 No significant differences |

| Ferrara 2008 | Total hip replacement N = 23 |

Behavioural instruction | 15 days and 4 weeks post‐surgery: VAS Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) subscale |

Control n = 12; intervention n = 11 VAS pain scores: significantly lower in intervention group at 4 weeks (not at 15 days apparently) |

| Field 1974 | Mixed orthopaedic surgery N = 60 |

Procedural information, hypnosis | Between 2 and 7 days post‐surgery; no further information | Control n = 30; intervention n = 30 No significant difference |

| Gilbey 2003 | Total hip arthroplasty N = 76 |

Behavioural instruction | 3 weeks post‐surgery Pain domain of WOMAC |

Control n = 25; intervention n = 32 Significant difference (P value < 0.01) for total WOMAC (pain, physical function and stiffness) and physical function domain. Reports surgery had such beneficial effect on pain that impact of intervention only marginal. |

| Hawkins 1993 | Gynaecological surgery N = 60 |

Behavioural instruction | 48 hours post‐surgery: VAS of average pain; categorical scale (5 categories from no pain to unbearable pain); nurse ratings of pain (collected hourly pain reports when not sleeping for first 48 hours after surgery) |

Control n = 40 (standard care and attention control); intervention n = 20 No significant differences (VAS ANOVA F = 0.06, df = 2, P value = 0.93) |

| Johnson 1978b | Sample 1: cholecystectomy, N = 81 Sample 2: inguinal hernia repair, N = 68 |

Intervention 1: ‘Instruction’: Behavioural instruction (deep breathing, coughing, leg exercises) Intervention 2: ‘Procedure information’: focus procedural information, also some sensory information and behavioural instruction Intervention 3: `Sensation information’: focus: sensory information, also some procedural information and behavioural instruction 2 x 3 factorial design: no instruction/instruction (Intervention 1; no information/information (Interventions 2 and 3) |

Pain: days 1, 2 and 3 post‐surgery: intensity of sensations on 10‐point scale Scores totaled over the 3 days in analysis | Sample 1 No main effect of condition Sample 2 MANOVA with DVs pain and distress of pain sensation: for first postoperative day: significant main effects for information level (F(4, 104) = 2.55, P value < 0.05), trend for an effect for instruction (F(2, 52) = 3.07, P value = 0.055), but only a main effect for distress scores reported (no univariate findings reported for pain – so seems no significant effects) |

| Johnson 1985 | Abdominal hysterectomy N = 199 |

Intervention 1: Procedural and sensory information Intervention 2: ‘Cognitive‐coping technique’ – cognitive intervention Intervention 3: ‘Behavioural‐coping technique’ – behavioural instruction 2x3 factorial design: no information/information (Intervention 1); no coping technique/coping technique (Interventions 2 and 3) |

Day 3 post‐surgery Pain scale from 1 to 10 |

MANOVA, controlling for covariates, with various outcomes including pain: ‘significant’ at P value < 0.10: coping technique, F (16, 286) = 1.59, P value =0.07. However, pain does not appear to be one of the outcomes responsible for this. |

| Kulkarni 2010 | Major abdominal surgery N = 80 |

Intervention 1: Behavioural instruction (deep breathing training) Intervention 2: Behavioural instruction (incentive spirometry) Intervention 3: Behavioural instruction (specific inspiratory muscle training) |

Pain (no information of how measured/when) | Control n = 17; intervention 1 n = 17; intervention 2 n = 15; intervention 3 n = 17. Median pain score for all groups is 3 (no ranges/IQRs) |

| Lilja 1998 | Breast cancer (BC) surgery N = 46 Total hip replacement (THR) N = 55 |

Procedural information, behavioural instruction | First 3 days post‐surgery: VAS | Control: n = 22, mode = 1 (BC day 1); intervention n = 22 No significant differences groups for either BC or THR patients (analysed separately) |

| Liu 2004 | Mixed orthopaedic surgery N = 74 |

Cognitive intervention | Pain: 0 to 10 VAS; timing not stated | Control n = 35, mean (SD)= 2.5 (0.52); intervention n = 39, mean = 2.85 (0.33) Significant difference (t = 2.61, P value < 0.05). Discussion: authors state “patients from the experimental group…had…low scores on pain compared to the control group with statistical significance” (p5). This appears to be at odds with mean scores, suggesting error in paper. |

| Oetker‐Black 2003 | Total abdominal hysterectomy N = 108 |

Behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention, relaxation | Day 1 post‐surgery: VAS At discharge: bodily pain (Health Status Questionnaire) |

No significant differences (VAS: t(1,105) = ‐0.54, P value = 0.591) |

| Parthum 2006 | Cardiac surgery N = 93 |

Procedural information, sensory information, behavioural instruction | 1. Pain intensity: VAS as part of modified McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), day 1 postoperative and retrospective rating of pain while on ICU 2. Proportion of patients in pain postoperatively (cut off: VAS > 3 on above measures) |

Cluster‐randomized Control n = 36, median (VAS current, at rest) = 4.0. Intervention: n = 37, median = 3.0 No significant differences between groups |

| Perri 1979 | Vaginal hysterectomy N = 26 |

Relaxation | Self report. 1 and 3 days postoperation; ‘McGill‐Melzack Pain Questionnaire’ Observed. 1 and 3 days postoperation – observed pain behaviour – Chambers‐Price Rating Scale for Pain |

Control n = 13; intervention mean = 13. No significant differences between groups (P value < 0.05) |

| Shelley 2007 | Coronary artery bypass surgery N = 90 |

Cognitive intervention | At discharge (4 days post‐surgery): 10 cm VAS | Control n = 43; intervention n = 37 Significant interaction between group, self efficacy and external health locus of control (F(1,71) = 4.06, P value < 0.05). Post hoc analysis: trend‐level effects: smaller increase in pain for prepared patients than controls if high external health locus of control and low self efficacy. Matched control appraisal patients: increased pain in intervention group compared with controls (controlling for baseline pain). |

| Shuldham 2002 | Coronary artery bypass surgery N = 356 |

Procedural information, behavioural instruction | Questionnaires presented on day 3 post‐surgery (or 3rd day after transfer to ward if still in intensive care unit on day 3 post‐surgery) Composite measure (including VAS, body map and categorical rating scale), authors used VAS in analysis |

No significant differences (using Mann‐Whitney U): U = 10,197.5; Z = ‐0.72, P value = 0.47 |

| Vukomanović 2008 | Total hip arthroplasty N = 45 |

Procedural information, behavioural instruction | VAS at discharge: pain at rest and movement |

Cluster‐randomized Control n = 20, mean (SD) = 6.2 (14.95); Intervention n = 20, mean (SD) = 3.95 (13.08) No significant difference in pain |

| Watt‐Watson 2004 | Coronary artery bypass surgery N = 406 |

Behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention | Days 1 to 5 post‐surgery: McGill Short‐form. Scores: Present Pain Intensity: most severe pain in previous 24 hours Pain Rating Index (sensory, affective and total); Numerical Rating Scale (on moving and worst pain in previous 24 hours) |

No main effect of group |

| Wells 1982 | Cholecystectomy N = 12 |

No control group Intervention 1: ‘Control’: Sensory information; behavioural instruction Intervention 2: (do not appear to receive ‘control’ intervention) Relaxation |

Rated on 10 cm line on evening on day of surgery, and days 1 and 2 post‐surgery | Intervention 1: n = 6, mean (SD) eve of operation = 5.4 (3.39); intervention 2: n = 6, mean (SD) = 5.65 (1.6) No main effect for treatment (F(1,7) = 3.0, P value = 0.13), time (F(7,2) = 3.3, P value = 0.07) or interaction between treatment and time (F(2,4) = 1.0, P value = 0.4) |

| Wijgman 1994 | Total knee arthroplasty N = 64 |

No control group Intervention 1: Procedural information Intervention 2: Behavioural instruction |

2, 5, 7, 10, 14 days post‐surgery and at discharge. VAS where 100 = worst pain | Overall n at day 2 = 63. Medians (IQRs) presented in Figure 1, not clear. No significant differences between groups |

| Ziemer 1982 | Gynaecologic or gastrointestinal N = 111 |

Intervention 1: Sensory information Intervention 2: Sensory information, behavioural instruction, cognitive intervention, relaxation |

2 to 4 days post‐surgery: 5‐point pain intensity rating scale | Control n = 40; intervention 1 n = 34; intervention 2 n = 37 Focus: correlation of pain with coping scales |

ANOVA = analysis of variance

BC = breast cancer

F = F statistic (ANOVA)

ICU = intensive care unit

IQR = interquartile range

MANOVA = multivariate analysis of variance

MPQ = McGill Pain Questionnaire (Melzack 1975)

N = number of participants in sample

PCA = patient‐controlled analgesia

SD = standard deviation

THR = total hip replacement

VAS = visual analogue scale

Fourteen of these studies reported no statistically significant differences between intervention and control conditions (Chumbley 2004; Daltroy 1998; Dewar 2003; Enqvist 1997; Field 1974; Gilbey 2003; Hawkins 1993; Lilja 1998; Oetker‐Black 2003; Parthum 2006; Perri 1979; Shuldham 2002; Vukomanović 2008; Watt‐Watson 2004). A further two studies did not clearly report postoperative pain findings, but this appears to be because comparisons were not significant (Johnson 1978b; Johnson 1985). These studies used a range of intervention techniques: procedural and sensory information (one study), procedural information and behavioural instruction (three), procedural information, sensory information, behavioural instruction (two); behavioural instruction (three); procedural information, behavioural instruction, cognitive interventions, relaxation techniques (one), procedural information, hypnosis (one); procedural and sensory information/cognitive interventions/behavioural instruction (one); behavioural instruction, relaxation techniques, cognitive interventions (one); relaxation (one); behavioural instruction, cognitive interventions (one); relaxation techniques, hypnosis (one).

Less clear findings were reported in two studies. Ferrara 2008 reported that postoperative pain scores were significantly lower in the intervention group than the control group at four weeks after surgery, but a comparison at 15 days was not clearly reported – it is possible that authors were choosing to not report non‐significant findings. Shelley 2007 reported a significant interaction between intervention group, self‐efficacy and external health locus of control (EHLC), but post‐hoc analyses revealed only trend level effects, such that intervention participants had a smaller pain increase than controls if they had high EHLC and low self‐efficacy. Participants with high self‐efficacy and high EHLC, or low self‐efficacy and low EHLC, reported increased pain for intervention participants compared with controls.