Abstract

Research has consistently linked symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) with relationship distress in combat veterans and their partners. Studies of specific clusters of PTSD symptoms indicate that symptoms of emotional numbing/withdrawal (now referred to as negative alterations in cognition and mood) are more strongly linked with relationship distress than other symptom clusters. These findings, however, are based predominantly on samples of male veterans. Given the increasing numbers of female veterans, research on potential gender differences in these associations is needed. The present study examined gender differences in the multivariate associations of PTSD symptom clusters with relationship distress in 465 opposite-sex couples (375 with male veterans and 90 with female veterans) from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. Comparisons of nested path models revealed that emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms were associated with relationship distress in both types of couples. The strength of this association, however, was stronger for female veterans (b = .46) and female partners (b = .28), compared to male veterans (b = .38) and male partners (b = .26). Results suggest that couples-based interventions (e.g., psychoeducation regarding emotional numbing symptoms as part of PTSD) are particularly important for both female partners of male veterans and female veterans themselves.

Combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a prevalent condition in veterans of the recent conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan (e.g., Tanielian & Jaycox, 2008), as well as past conflicts like the Vietnam war (e.g., Kulka et al., 1990). Indeed, despite the time that has passed since the Vietnam era, Vietnam veterans account for more than 50% of those seeking treatment for PTSD in the Veterans Affairs (VA) system, with numbers increasing 7.4% per year between 1997 and 2010 (Hermes, Rosenheck, Desai, & Fontana, 2012). In recent years, researchers have examined many problems associated with combat-related PTSD, including interpersonal difficulties. Two recent meta-analyses have shown significant associations of PTSD diagnosis/symptom severity with marital/relationship distress in veterans and other trauma survivors (Taft, Watkins, Stafford, Street, & Monson, 2011), as well as their romantic partners (Lambert, Engh, Hasbun, & Holzer, 2012). Moreover, longitudinal research has shown bidirectional associations between PTSD symptoms and relationship distress (e.g., Campbell & Renshaw, 2013; Erbes, Meis, Polusny, & Compton, 2011; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; King, Taft, King, Hammond, & Stone, 2006). These bidirectional patterns suggest that couples can fall into a negative cycle of distress, in which PTSD symptoms worsen relationship quality, and vice versa. Thus, further research into the associations of PTSD symptoms and relationship processes is needed.

Some researchers have attempted to further our understanding of these associations by exploring how individual symptom clusters of PTSD relate to relationship functioning. Most prior studies of this nature have examined a 4-cluster model of PTSD, with symptoms broken into reexperiencing, situational avoidance, emotional numbing and withdrawal, and hyperarousal clusters (e.g., Cook, Riggs, Thompson, Coyne, & Sheikh, 2004). Of note, these clusters closely mirror the new criteria in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (5th ed.; DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association [APA], 2013), with the DSM-5 category of negative alterations in cognition and mood subsuming emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms. Several studies in this area have suggested that the withdrawal/numbing symptom cluster is the key cluster accounting for most of the association between PTSD symptoms and relationship distress (see review by Monson, Taft, & Fredman, 2009).

The association of emotional numbing/withdrawal with relationship distress makes sense in light of the essential role of emotional expression in the development and maintenance of intimate relationships (e.g., Gottman & Levenson, 1986; Reis & Shaver, 1988). In this vein, service members who have blunted emotional experience and expression are likely to experience difficulties in their romantic relationships (e.g., Reddy, Meis, Erbes, Polusny, & Compton, 2011). So far, however, research on the interpersonal effects of PTSD-related emotional numbing in military couples has focused almost exclusively on male veterans and female partners. As of 2011, women made up 14.5% of all active duty service members (N = 204,714; U.S. Department of Defense, 2012). The prevalence of military sexual trauma suggests that female service members are fairly likely to experience potentially traumatic events in the context of their service (Street, Vogt, & Dutra, 2009), and this likelihood is increased by the recent approval for women to serve in direct combat roles while deployed (e.g., LeardMann et al., 2013). Thus, there is a strong need to extend our understanding of the interpersonal effects of PTSD to female veterans and their partners.

Given that women are typically more emotionally expressive than men in romantic relationships (e.g., Alexander & Wood, 2000; Timmers, Fisher, & Manstead, 1998), emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms might be differentially associated with relationship distress across genders. Women’s capacity to emotionally express themselves may play a more central role in the successful functioning of a heterosexual relationship. Thus, absence or declines in a woman’s emotion expression skills may have more powerful effects on the perceived quality of the romantic relationship, leading to an even stronger association of emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms and relationship dysfunction when women, rather than men, have PTSD. Research that examines gender differences in the associations of symptom clusters with relationship distress in both veterans and partners is thus needed to address these issues.

We identified only two published studies that have attempted to examine these questions. Taft, Schumm, Panuzio, and Proctor (2008) analyzed associations among combat exposure, PTSD symptoms, and family adjustment in 1,407 male and 105 female veterans of Operation Desert Storm. Although they did not examine the unique association of each symptom cluster with family adjustment problems, they did find gender differences in the strength of the loadings of both emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms and hyperarousal symptoms on an overarching latent variable of PTSD symptoms. Specifically, emotional numbing/withdrawal had a stronger loading for men, whereas hyperarousal had a stronger loading for women. Given that the PTSD latent variable predicted significant variance in family adjustment, the differential loadings meant that the emotional numbing/withdrawal cluster had a larger indirect effect on family adjustment for men than women, whereas hyperarousal had a larger indirect effect for women than men. This difference, however, was a result of gender differences in the structure of PTSD, rather than a direct comparison of how numbing and withdrawal symptoms might have differentially impacted interpersonal functioning. These findings may therefore solely reflect that PTSD symptoms are organized differently for men versus women, rather than that certain symptom clusters actually have a stronger or weaker link to relationship adjustment itself. Additionally, the outcomes were participants’ perceived flexibility and closeness of their family, rather than marital problems specifically.

In a recent study that more directly examined associations of PTSD symptom clusters with marital functioning, Erbes et al. (2011) examined gender differences in the bivariate correlations of reexperiencing, situational avoidance, dysphoria, and hyper-vigilance with relationship distress, using a sample of National Guard service members who deployed to Iraq during 2006. Although the small number of female (n = 33) versus male (n = 279) service members precluded more rigorous analysis of gender differences, the bivariate correlations revealed generally stronger correlations for women (r = −.61 vs. r = −.33), with a marginally nonsignificant difference for situational avoidance (z = 1.90, p = .06). Given the size of the sample of female veterans, however, these results are highly preliminary. Data that include a larger sample of female veterans with both veteran and partner reports of relationship distress are sorely needed to gain a fuller understanding of potential gender differences in associations of combat-related PTSD with intimate relationship functioning.

To address this need, we examined gender differences in the multivariate associations of combat-related PTSD with relationship distress in both combat veterans and their partners, using data from the National Vietnam Veterans’ Readjustment Study (NVVRS). Although previous research has explored the bivariate association of overall PTSD with relationship functioning in the female veteran subsample of the NVVRS (Gold et al., 2007), no previous work has explored gender differences in associations of symptom clusters with relationship distress in this sample.

Method

Participants

Participants were 465 U.S. Vietnam veterans (375 male; 90 female) and their opposite-sex romantic partners. The racial/ethnic breakdown for veterans was 60.1% White, 18.8% African American, 18.5% Hispanic, and 2.6% other, whereas 62.0% of partners were White, 18.9% African American, 18.5% Hispanic, and 0.6% other. At the time of data collection, veterans’ mean age was 41.66 years (SD = 5.17), and partners’ mean age was 40.00 years (SD = 7.44). Most couples were married (94%), with a mean marriage length of 14.44 years (SD = 7.18).

Procedure

As described in detail by Kulka and colleagues (1990), the NVVRS was a Congressionally mandated study conducted in the mid- to late 1980s to establish PTSD prevalence and document postdeployment adjustment difficulties among veterans in a nationally representative sample. Veteran participants were selected from all Vietnam-era veterans who served between August 5, 1964 and May 7, 1975. Veterans who agreed to participate in the main component, termed the National Survey of the Vietnam Generation (N = 3,016), were interviewed for 3–5 hours in their homes about topics including psychological health, combat and postwar experiences, and family adjustment. Analyses showed no significant differences between those who agreed to participate and nonparticipant veterans (Kulka et al., 1990). From the larger veteran sample, 466 veterans were invited to participate in the Family Interview component of the NVVRS with their spouses or romantic partners (defined as “a person with whom the veteran was living as though married”; Jordan et al., 1992, p. 917). Participants were specifically selected to provide a range of functioning in veterans, with 31% of the veterans having a high probability of PTSD, 21% having high levels of combat exposure but subthreshold PTSD (Weiss et al., 1992), 16% having nonspecific distress, and 32% classified as low risk. Romantic partners were interviewed separately from their veteran partner for approximately 1 hour. Topics in the romantic partner interview component primarily included partners’ perceptions of veterans’ adjustment, their own adjustment, and their own experiences with the veteran. Data on primary measures of interest from one partner were missing, leaving 465 veterans and partners in the sample.

Measures

The Mississippi Scale for Combat-Related PTSD (M-PTSD; Keane, Caddell, & Taylor, 1988) is a 35-item self-report scale used to measure symptoms of PTSD related to military activity. The scale consists of four clusters of symptoms: reexperiencing and situational avoidance (11 items), withdrawal and emotional numbing (11 items), arousal and lack of control (8 items), and self-persecution (5 items). The present study focused on the first three clusters, which represent the four symptom clusters that define PTSD in the DSM-5 (APA, 2013). The first cluster combines reexperiencing and situational avoidance, but only one of the 11 items explicitly addressed situational avoidance. Thus, we retained this unitary variable that combined symptoms from these two clusters, rather than modeling a separate, 1-item representation of situational avoidance. For all items in the M-PTSD, respondents rated the frequency with which they have experienced each symptom “since the event” on a 5-point Likert scale. The M-PTSD has excellent internal consistency, test-retest reliability, convergent, and discriminant validity (Keane et al., 1988; Pratt, Brief, & Keane, 2006). For this study, because the clusters have different numbers of items, we calculated scores as item averages, to allow for easier comparison. In this sample, internal consistency of the total M-PTSD score was high for both male (α = .95) and female (α = .91) veterans. Internal consistencies of the clusters were also strong for male veterans (all αs > .80). For the female veterans, the reexperiencing/avoidance and withdrawal/numbing clusters also had strong internal consistency (αs > .80); however, the internal consistency of the arousal and lack of control cluster was low (α = .65).

Jordan et al. (1992) created the Marital Problems Index (MPI) from 16 Likert-type items (coded 0–5) that were included in the NVVRS Family Interview Component. These items were derived from existing measures of marital/relationship distress including the Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview Marital Dissatisfaction Scale (Dohrenwend, 1982), studies of American life (e.g., Campbell, Converse, & Rodgers, 1976; Veroff, Douvan, & Kulka, 1981), and the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). Sample items included, “In general, how often do you think that things between you and your partner are going well?”, “During the past year, how often have you felt uncomfortable with your husband/wife/partner?”, and “How often do you and your partner quarrel?” Items were answered on a scale from 0 = Never to 5 = All the time, with reverse scoring on some items. Jordan et al. found that veterans with PTSD and their partners had higher scores on the MPI than veterans without PTSD and their partners, thereby supporting convergent validity. Also, the items load onto a single factor and demonstrated high internal consistency for both veterans (Cronbach’s α = .92) and spouses (Cronbach’s α = .94) in the original study (Jordan et al., 1992). As our dataset did not have original items for this scale specified, we were unable to assess internal consistency for female and male veterans separately. MPI scores represent the average response to each item, with higher scores indicating greater marital distress.

Data Analysis

Initially, to describe our sample, we examined means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of variables of interest, using a one-way multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to test for overall differences in men’s and women’s reports on these variables. To test our primary question regarding gender differences in associations of PTSD symptom clusters with relationship distress, we utilized path analysis. We chose path analysis with observed cluster scores, rather than estimating latent variables for each cluster from individual items because this measurement model would have consisted of 57 parameters (30 variances for observed items, and 27 measurement paths from latent variables to individual items). With only 90 female veteran/male partner couples (less than two cases per parameter), parameters from this measurement model would likely have been unstable (well below the recommended minimum of five cases per parameter; e.g., Bentler & Chou, 1987). Path analysis allowed us to account for the dyadic nature of our data by modeling veteran and partner relationship distress simultaneously as covarying endogenous (outcome) variables. The three primary PTSD symptom clusters were modeled as covarying exogenous (predictor) variables, with all structural paths specified. Participants were grouped according to veterans’ gender. The extent of missing data was quite low (less than 1% on all variables of interest). Missing data were accounted for using full information maximum likelihood in all path analyses.

In an initial model, all parameters (means/intercepts, variances, covariances, and structural paths) were allowed to vary across male veteran couples and female veteran couples. This initial model was saturated, producing no fit indices. We subsequently analyzed nested models in which variances for each variable were constrained to be equal across gender, then means/intercepts, and finally covariances. We evaluated chi-square differences for each of these nested models to determine whether constraining any of these parameters to be equal across genders produced a significant decrement in fit. Nonsignificant chi-square difference scores indicated that two nested models did not differ significantly in their fit to the data. The most parsimonious model was, therefore, the one in which the largest number of variances, means/intercepts, and covariances were equal across genders, without a significant decrease in fit.

After identifying the most parsimonious model with regard to variances, means/intercepts, and covariances, we proceeded to evaluating the primary research question: whether there were significant gender differences in the associations of symptom clusters with relationship distress. To answer this question, we compared the identified model to nested models in which structural paths from each cluster to both partners’ relationship distress were constrained to be equal across genders, again using chi-square difference scores to evaluate whether there were significant decrements in fit. There were three total nested models, one for each cluster. For example, in the first nested model, the path from reexperiencing and situational avoidance symptoms to veterans’ distress was constrained to be equal across gender, and the path from reexperiencing and situational avoidance symptoms to partners’ distress was constrained to be equal across gender. All other structural paths remained free to vary across gender. Thus, each nested model differed from the comparison model by 2 degrees of freedom (1 per path constrained). After arriving at the best-fitting, most parsimonious model, we evaluated the overall fit according to the range of cutoff values that have been recommended for root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA; .10, .08, and .05), comparative fit index (CFI; .90 and .95), and normed fit index (NFI; 90 or .95; e.g., Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004). All analyses were conducted using Amos 18.0 (Arbuckle, 2007).

Finally, we evaluated whether including several other variables (length of marriage, spouses’ perceived health, service members’ perceived health, number of children, and occupational status) in the model altered results from any of these analyses. Patterns of significance were unchanged in all instances (results available from first author upon request); thus, results are reported without covariates.

Results

Means and standard deviations of all measures are found in Table 1. The MANOVA comparing means of these variables across genders was significant, F(5, 453) = 10.54, p < .001; Pillai’s trace = .10; η2 = .10. Follow-up one-way ANOVAs (see Table 1) indicated that male veterans reported higher levels of all symptom clusters compared to female veterans, and female partners reported greater relationship distress than male partners. Female and male veterans, however, did not differ in their self-report of relationship distress.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Differences of Veterans’ PTSD Symptom Clusters and Veteran’s and Partners’ Marital Distress by Gender

| Male veterans/female partners (n = 375) | Female veterans/male partners (n = 90) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | η2 |

| RSA | 2.26 | 0.76 | 1.77 | 0.57 | .07*** |

| ENW | 2.44 | 0.80 | 1.88 | 0.58 | .08*** |

| ALC | 2.14 | 0.74 | 1.71 | 0.45 | .06*** |

| Veterans’ MPI | 1.97 | 0.74 | 1.87 | 0.66 | .00 |

| Partners’ MPI | 2.05 | 0.90 | 1.71 | 0.68 | .02** |

Note. PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RSA = reexperiencing and situational avoidance; ENW = emotional numbing and withdrawal; ALC = arousal and lack of control; MPI = marital problems index.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Intercorrelations of all measures for male veteran couples and female veteran couples are shown in Table 2. All symptom clusters were strongly intercorrelated for both male and female veterans. For male veterans, all clusters were significantly correlated with self-reported relationship distress, with medium to large effect sizes. For female veterans, all clusters were also significantly associated with self-reported relationship distress, but the effect for emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms was notably larger than that of the other two clusters. Correlations between veteran symptom clusters and partner relationship distress were fairly similar for male and female partners, with slightly larger effects for female partners.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations of Veterans’ PTSD Symptom Clusters, and Veterans’ and Partner’s Marital Distress by Gender

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.RSA | – | .62*** | .53*** | .23* | .15 |

| 2. ENW | .76*** | – | .69*** | .52*** | .24* |

| 3. ALC | .76*** | .76*** | – | .36** | .25* |

| 4. Veterans’ MPI | .39*** | .47*** | .44*** | – | .56*** |

| 5. Partners’ MPI | .23** | .33*** | .27*** | .49*** | – |

Note. Values below diagonal represent correlations for male veteran/female partner dyads (n = 375); values above the diagonal represent correlations for female veteran/male partner dyads (n = 90). PTSD = posttraumatic stress disorder; RSA = reexperiencing and situational avoidance; ENW = emotional numbing and withdrawal; ALC = arousal and lack of control; MPI = marital problems index.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

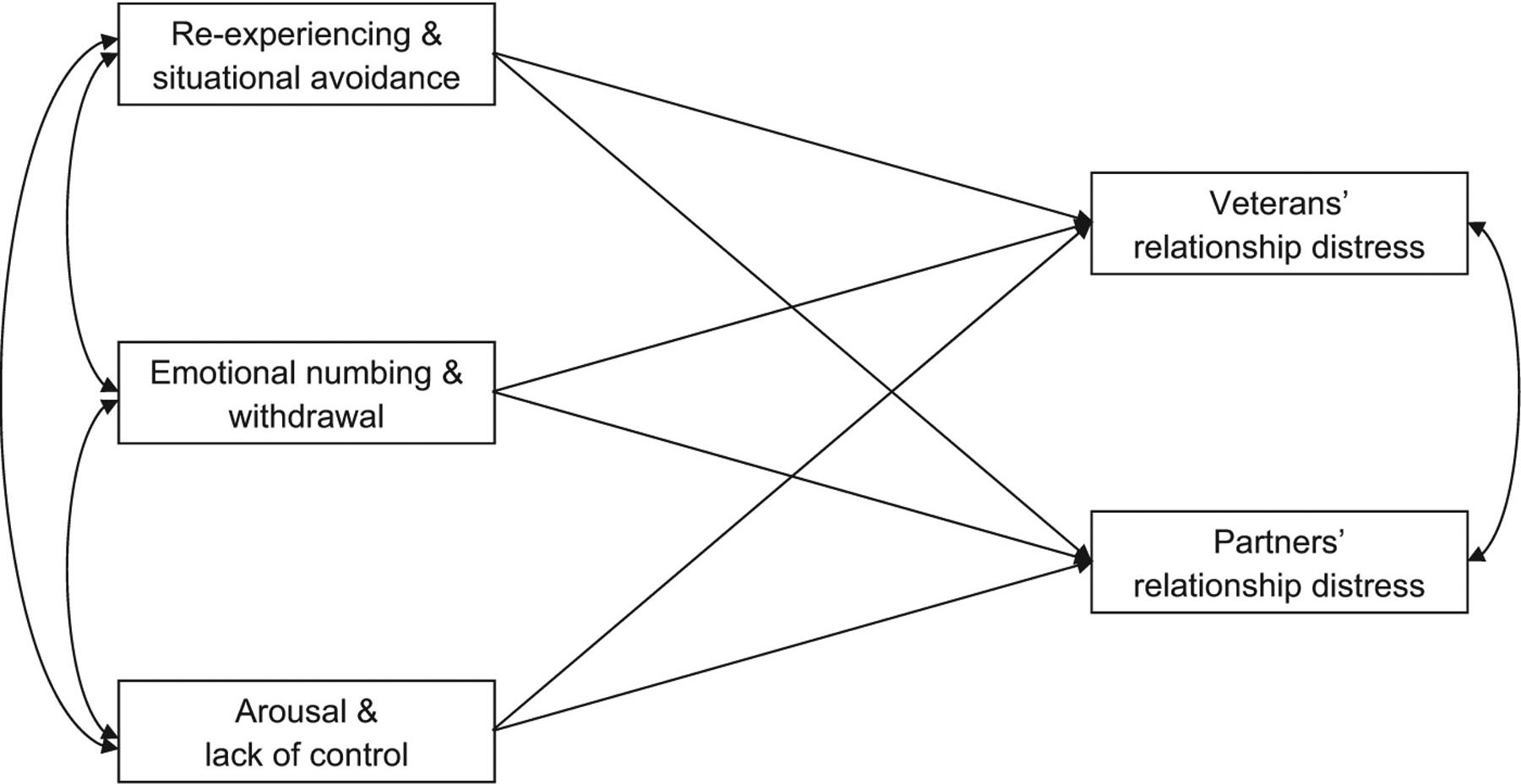

The overall model of interest is shown in Figure 1. The initial model with all parameters free to vary across gender was fully saturated. Exploration of nested models in which variances, means/intercepts, and covariances were held equal across gender yielded only three parameters with significant differences across gender: the variance of arousal and lack of control (male veterans had greater variance than female veterans), the variance of partners’ relationship distress (female partners had greater variance than male partners), and the covariance of reexperiencing symptoms and arousal and lack of control symptoms (male veterans had greater covariance than female veterans). Full results of these models are available from the first author upon request. Based on these results, a model with these three parameters freed across gender and all other means/intercepts, variances, and covariances held equal across gender represented the optimal fit for the data with regard to the nonstructural paths. With all structural paths freed to vary across gender, this model produced acceptable fit for the data, χ2(11) = 66.88, p < .001; CFI = .95; NFI = .94; RMSEA = .10.

Figure 1.

Overall path model of associations of veterans’ symptoms of PTSD with veterans’ and partners’ relationship distress.

We then evaluated nested models in which structural paths were constrained to be equal across gender. The results for each of the three nested models are shown in Table 3, with comparisons to the model identified above. Only the model in which paths from emotional numbing/withdrawal were constrained across gender resulted in a significant decrement in fit. Thus, we evaluated the fit of a model in which the parameters for these two paths were the only structural parameters allowed to vary across gender (the other four structural paths were constrained to be equal across gender). This model provided an adequate fit for the data: χ2(15) = 71.89, p < .001; CFI = .95; NFI = .93; RMSEA = .09. The estimates for the paths are shown in Table 4. Overall, greater levels of emotional numbing and withdrawal in veterans were associated with more relationship distress for both veterans and partners. The associations, however, were stronger for female veterans than for male veterans (pairwise parameter comparison z = 3.04, p = .002), and for female partners than for male partners (pairwise parameter comparison z = 2.39, p = .017). In addition, for both genders, greater arousal and lack of control in veterans was associated with greater relationship distress in veterans but not partners.

Table 3.

Fit Indices for Models with Structural Paths Constrained Across Gender

| Pathsa | CFI | NFI | RMSEA | χ2(13) | χ2difference(2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSA | .95 | .94 | .10 | 68.17 | 1.29 |

| ENW | .94 | .93 | .10 | 76.16 | 9.28* |

| ALC | .95 | .94 | .10 | 68.80 | 1.92 |

Note. n = 465. The χ2difference values are based on comparison of the model described with the model that allowed all structural paths to vary across gender. CFI = comparative fit index; NFI = normed fit index; RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation; RSA = reexperiencing and situational avoidance; ENW = emotional numbing and withdrawal; ALC = arousal and lack of control.

Paths to each partner’s distress constrained to be equal across gender.

p < .05.

Table 4.

Structural Path Estimates from the Final Model

| Male veterans/Female partners (n = 375) | Female veterans/Male partners (n = 90) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Unstandardized estimate | SE | Unstandardized estimate | SE |

| RSA → Veteran MPI | − .05 | .07 | − .05 | .07 |

| RSA → Partner MPI | − .06 | .08 | − .06 | .08 |

| ENW → Veteran MPI | .35*** | .06 | .44*** | .07 |

| ENW → Partner MPI | .32*** | .08 | .24** | .08 |

| ALC → Veteran MPI | .20** | .07 | .20** | .07 |

| ALC → Partner MPI | .13 | .09 | .13 | .09 |

Note. RSA = reexperiencing and situational avoidance; ENW = emotional numbing and withdrawal; ALC = arousal and lack of control; MPI = marital problems index.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Discussion

Women represent a growing proportion of the military, and the recent official approval of female service members to serve in combat highlights the need for greater research on this population. Extensive research demonstrates that PTSD is associated with greater relationship distress (Lambert et al., 2012; Taft et al., 2011), and emotional numbing/withdrawal seems to account for the bulk of the variance in relationship distress (Monson et al., 2009). To date, however, research on military veterans has focused almost exclusively on male veterans and female partners. The purpose of the present study was to analyze whether these patterns held across genders in a sample of heterosexual couples drawn from the NVVRS.

Our results demonstrate that although emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms were most strongly associated with relationship distress in veterans and partners of both genders, the strength of this association was stronger in female veterans and partners, relative to male veterans and partners. Given that all variables were scored as item averages, and all items used 5-point scales, one can use the unstandardized estimates to understand these effects. Specifically, in veterans, the increase in relationship distress that was tied to emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms was 25% greater for female veterans (estimate of .44) than for male veterans (estimate of .35). In partners, the increase in relationship distress that was tied to emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms was approximately 33% greater for female partners (estimate of .32) than for male partners (estimate of .24).

This pattern suggests that when emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms are present, they are associated with greater relationship distress in women, regardless of which member of the couple is the veteran. This pattern contradicts the findings from Taft et al. (2008). The difference may be due to methodological differences, in that Taft et al.’s findings were a result of gender differences in the measurement model of PTSD, and their outcome variable was overall family functioning, not intimate relationship functioning. Furthermore, Taft et al. controlled for combat exposure in their analyses, which may also have altered the results. Further research evaluating these issues is needed to address the possible differences.

The pattern of our results is consistent with the notion that women are more in tune with the emotional health of relationships. Thus, women are less happy in their relationships than men when either they or their partner have difficulty feeling or expressing emotions. Of note, however, actor and partner effects of emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms were significant for all individuals, regardless of gender. Thus, our findings reinforce the importance of attending to PTSD-related emotional numbing symptoms in the context of combat veterans’ marriages or romantic relationships. Such efforts could include psychoeducation for partners of combat veterans to increase their understanding of the nature of these symptoms, as well as couple-based work to address these symptoms and their effect on the relationship (e.g., Renshaw, Allen, Carter, Markman, & Stanley, 2014). Moreover, our findings suggest that such efforts may be particularly relevant for female veterans and for female partners of male veterans. Thus, clinicians working with trauma-exposed couples may need to explore whether women are perceiving emotional numbing symptoms as more problematic than men. If so, it may be necessary to explicitly address how these symptoms affect the relationship to help build men’s motivation to address these symptoms.

It is important to note that these results come from a sample of Vietnam veterans, assessed 10–20 years after the Vietnam war had ended. Additionally, the sample was intentionally selected to vary in the severity of the veterans’ distress, so our results are relevant to veterans with varying levels of symptoms of PTSD, rather than exclusively to samples of patients who meet full criteria for PTSD. The comparability of this sample to the more recent cohort of veterans from the conflicts in Iraq and Afghanistan, as well as veterans of conflicts between the 1970s and 2001, is unknown. Moreover, the comparability of this sample to Vietnam veteran couples today (more than 30 years after these data were collected) is also unknown. To our knowledge, however, these findings are the first to examine gender differences in the associations of specific PTSD symptoms with relationship distress in both veterans and their partners. They provide preliminary support for the notion that there may be gender differences in the interpersonal correlates of PTSD and highlight the need for future research that attends to such differences.

There are additional limitations to this study, as well. Data were cross-sectional, prohibiting any analysis of directionality of effects. Several studies demonstrate bidirectional associations between PTSD symptoms and relationship processes (Campbell & Renshaw, 2013; Erbes et al., 2011; Kaniasty & Norris, 2008; King et al., 2006). Thus, future research that examines gender differences over time is needed. Also, the NVVRS sample consisted of couples who had remained married. We do not know whether the same pattern or results would be found when considering divorced couples nor can we know whether symptoms have differential associations with the likelihood of ending one’s relationship. In addition, the subsample of female veteran/male partner couples was much smaller than that of male veteran/female partner couples. Furthermore, female veterans of the Vietnam war likely had very different deployment experiences than female veterans of more recent conflicts. Indeed, female veterans in this sample did not have responses recorded for combat exposure items; however, most female veterans were nurses who typically were exposed to Criterion A events (e.g., severe wounds, suffering, death). Future research should attend to levels of combat, as well as other types of potentially traumatic events experienced by both male and female veterans, to account for potential gender differences in types of events experienced. Another methodological concern was that the internal consistency of the arousal and lack of control subscale for female veterans was low. It is plausible that this lack of reliability reduced the strength of associations of this variable with relationship satisfaction in female veterans and male partners, which may have obscured potential gender differences for this cluster. Additionally, we did not use stratified survey software, meaning that these findings are not nationally representative. Finally, only heterosexual couples were included in this sample. Future research that begins to explore PTSD in the context of gay/lesbian relationships is also needed.

These limitations notwithstanding, the present results highlight both the importance of emotional numbing/withdrawal symptoms of PTSD with regard to interpersonal relationships and the potential gender differences in the interpersonal context of PTSD. Future research that builds on these findings can help better inform our efforts to alleviate suffering in and strengthen the relationships of combat veterans and their families.

References

- Alexander MG, & Wood W (2000). Women, men, and positive emotions: A social role interpretation. In Fischer AH (Ed.), Gender and emotion: Social psychological perspectives (pp.189–210). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL (2007). Amos (Version 18.0) [Computer Program]. Chicago, IL: SPSS. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, & Chou C-P (1987). Practical issues in structural equation modeling. Sociological Methods & Research, 16, 78–117. doi: 10.1177/0049124187016001004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, & Renshaw KD (2013). Disclosure as a mediator of associations between PTSD symptoms and relationship distress. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27, 494–502. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.06.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell A, Converse PE, & Rodgers WL (1976). The quality of American life: Perceptions, evaluations, and satisfactions. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Cook JM, Riggs DS, Thompson R, Coyne JC, & Sheikh JI (2004). Posttraumatic stress disorder and current relationship functioning among World War II ex-prisoners of war. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 36–45. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BP (1982). Psychiatric Epidemiology Research Interview (PERI). New York, NY: Columbia University, Social Psychiatry Research Unit. [Google Scholar]

- Erbes CR, Meis LA, Polusny MA, & Compton JS (2011). Couple adjustment and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in National Guard veterans of the Iraq war. Journal of Family Psychology, 25, 479–487. doi: 10.1037/a0024007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold JI, Taft CT, Keehn MG, King DW, King LA, & Samper RE (2007). PTSD symptom severity and family adjustment among female Vietnam veterans. Military Psychology, 19, 71–81. doi: 10.1080/08995600701323368 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gottman JM, & Levenson RW (1986). Assessing the role of emotion in marriage. Behavioral Assessment, 8, 31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Hermes EDA, Rosenheck RA, Desai R, & Fontana AF (2012). Recent trends in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders in the VHA. Psychiatric Services, 63, 471–476. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201100432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan BK, Marmar CR, Fairbank JA, Schlenger WE, Kulka RA, Hough RL, & Weiss DS (1992). Problems in families of male Vietnam veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 916–926. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.6.916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaniasty K, & Norris FH (2008). Longitudinal linkages between perceived social support and posttraumatic stress symptoms: Sequential roles of social causation and social selection. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 21, 274–281. doi: 10.1002/jts.20334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keane TM, Caddell JM, & Taylor KL (1988). Mississippi scale for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder: Three studies in reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 85–90. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.56.1.85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King DW, Taft C, King LA, Hammond C, & Stone ER (2006). Directionality of the association between social support and posttraumatic stress disorder: A longitudinal investigation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 36, 2980–2992. doi: 10.1111/j.0021-9029.2006.00138.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulka RA, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Hough RL, Jordan BK, Marmar CR, & Weiss DS (1990). Trauma and the Vietnam war generation: Report of the findings from the National Vietnam Veterans Readjustment Study. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel. [Google Scholar]

- Lambert JE, Engh R, Hasbun A, & Holzer J (2012). Impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on the relationship quality and psychological distress of intimate partners: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 729–737. doi: 10.1037/a0029341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeardMann CA, Pietrucha A, Magruder KM, Smith B, Murdoch M, Jacobson IG, … Smith TC (2013). Combat deployment is associated with sexual harassment or sexual assault in a large, female military cohort. Women’s Health Issues, 23, e215–e223. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau K-T, & Wen Z (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indices and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11, 320–341. doi: 10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Monson CM, Taft CT, & Fredman SJ (2009). Military-related PTSD and intimate relationships: From description to theory-driven research and intervention development. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt EM, Brief DJ, & Keane TM (2006). Recent advances in psychological assessment of adults with posttraumatic stress disorder. In Follette VM & Ruzek JI (Eds.), Cognitive-behavioral therapies for trauma (2nd ed., pp. 34–61). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Reddy MK, Meis LA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, & Compton JS (2011). Associations among experiential avoidance, couple adjustment, and interpersonal aggression in returning Iraqi war veterans and their partners. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 515–520. doi: 10.1037/a0023929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis HT, & Shaver P (1988). Intimacy as an interpersonal process. In Duck S, Hay DF, Hobfoll SE, Ickes W, & Montgomery BM (Eds.), Handbook of personal relationships: Theory, research, and interventions (pp. 367–389). Oxford, England: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Renshaw KD, Allen ES, Carter S, Markman HJ, & Stanley SM (2014). Partners’ attributions for service members’ symptoms of combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavior Therapy, 45, 187–198. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB (1976). Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 38, 15–28. doi: 10.2307/350547 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Street AE, Vogt D, & Dutra L (2009). A new generation of women veterans: Stressors faced by women deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. Clinical Psychology Review, 29, 685–694. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Schumm JA, Panuzio J, & Proctor SP (2008). An examination of family adjustment among Operation Desert Storm veterans. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 648–656. doi: 10.1037/a0012576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taft CT, Watkins LE, Stafford J, Street AE, & Monson CM (2011). Posttraumatic stress disorder and intimate relationship problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79, 22–33. doi: 10.1037/a0022196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanielian T, & Jaycox LH (2008). Invisible wounds of war: Psychological and cognitive injuries, their consequences, and services to assist recovery. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Timmers M, Fischer AH, & Manstead ASR (1998). Gender differences in motives for regulating emotions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24, 974–985. doi: 10.1177/0146167298249005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Defense. (2012). 2011 demographics profile of the military community (updated November 2012). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Veroff J, Douvan E, & Kulka RA (1981). The inner American: A self-portrait from 1957 to 1976. New York, NY: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss DS, Marmar CR, Schlenger WE, Fairbank JA, Jordan BK, Hough RL, & Kulka RA 1992. The prevalence of lifetime and partial post-traumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5, 365–376. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490050304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]