Abstract

α-Amylase is an enzyme involved in the breaking down of large insoluble starch molecules into smaller soluble glucose molecules. Catunaregam spinosa (Thunb.) Tirveng. (syn. Randia dumetorum (Retz.) Lam., Family: Rubiaceace) has been used as traditional medicine for the treatment of gastrointestinal problems, skin diseases, and diabetes. In this context, we studied the in vitro α-amylase inhibiting properties of methanol extracts of leaves and bark of C. spinosa. The methanol extract of bark was further fractionated into hexane, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate, and water-soluble fractions, and their α-amylase inhibitory activity was evaluated. In silico molecular docking and ADMET analysis of several compounds previously reported from the bark of C. spinosa were also performed. The in vitro α-amylase inhibition activity assay of the dichloromethane fraction of extract of bark (IC50: 77.17 ± 1.75 μg/mL) was more potent as compared to hexane and ethyl acetate fractions. The in silico molecular docking study showed that previously reported compounds from the stem bark such as balanophonin, catunaregin, β-sitosterol, and medioresinol were bounded well with the active catalytic residue of porcine pancreatic α-amylase indicating better inhibition. The ADMET analysis showed the possible drug-likeness and structure-activity relationship of selected compounds. These compounds should be studied further for their potential α-amylase inhibition in animal models.

1. Introduction

The α-amylase is a prominent enzyme found in saliva and pancreatic juice which helps to break down large insoluble starch molecules into glucose that is absorbable by the digestive system [1]. The inhibitors of α-amylase help to delay the breakdown of starch into glucose molecules [2]. In patients with hyperglycemia, an effective treatment option could be the inhibition of pancreatic α-amylase that controls carbohydrate absorption [3]. The clinically available inhibitor, i.e., acarbose, has several side effects associated with gastrointestinal problems such as flatulence and diarrhea [4]. Various traditional medicines and herbs are well known for their role in the prevention and treatment of diabetes. Some plant-derived constituents with antidiabetic properties have been isolated and shown to have high potential and lower side effects than synthetic drugs [5].

Catunaregam spinosa (Thunb.) Tirveng. (Syn. Randia dumetorum (Retz.) Lam., Family: Rubiaceae) (Figure 1) occurs at around 1000-1500 m altitude from the sea level [6] and is distributed in the tropical and semitropical climatic zones [7]. This plant has been reported from various parts of China, Nepal, Bangladesh, and India [8]. Traditionally, it has been used to treat various symptoms such as skin diseases, tumors, wounds, ulcers, and diabetes [6, 9]. In India, the bark juice of this plant is used to treat several gastrointestinal problems such as diarrhea and dysentery [10]. In the traditional Ayurvedic system, this plant is used in the treatment procedure called “Vamana” to prevent forthcoming diseases such as hyperacidity, rhinitis, migraine, and anorexia [11]. The wide variety of bioactive compounds such as triterpene saponins [12–14], iridoid [15], flavonoids [16], and dihydroisocumarins [7] are reported which have shown potent an anti-inflammatory, antioxidant [17], antidiabetic, and antihyperlipidemic [18] activities. In this study, we evaluated the in vitro α-amylase inhibitory activity of the extracts of leaves and bark of C. spinosa and fractions of bark extract. To understand the mechanism, the in silico analysis of the previously reported compounds from the bark was performed via molecular docking studies and ADMET analysis. This study can be useful to justify the ethnomedicinal use of C. spinosa in diabetes-related problems. This can pave the way towards the discovery of a plant-based α-amylase inhibitor from C. spinosa.

Figure 1.

Photographs of Catunaregam spinosa (Thunb.) Tirveng.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemical Reagents

The substrate 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl-α-D-maltotrioside (CNPG3), enzyme porcine pancreatic α-amylase (PPA), and acarbose were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Germany. All other reagents were of analytical grade.

2.2. Plant Identification, Processing, and Extraction

The leaves and bark of C. spinosa were collected from the upper region of Sindhupalchok district, Nepal, and identified at the National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH) of the Department of Plant Resources, Ministry of Forest and Environment, Kathmandu, Nepal (Voucher code: DT 01). The collected materials were shade dried and grounded to get powder. The powdered leaves and bark (800 g each) were extracted in methanol separately by maceration for 72 hours. The extracts were then filtered and dried by using a rotary evaporator.

2.3. Fractionation

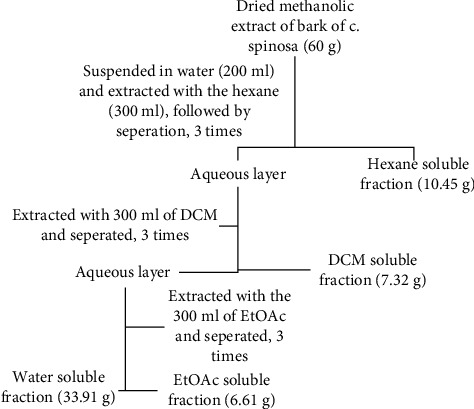

The more active extract, i.e., extract of the bark, was selected for fractionation using different solvents hexane, dichloromethane (DCM), and ethyl acetate (EtOAc) based on polarity. The methanolic extract was suspended in 200 mL of water and extracted with hexane. The aqueous layer was again extracted with dichloromethane followed by ethyl acetate. The process was repeated three times for each solvent as shown in Figure 2. The fractions were dried using a rotary evaporator [19, 20]. The methanol extracted crude extract, and solvent fractions were employed for the in vitro α-amylase inhibition experiment.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of fractionation of methanolic bark extract in different solvent.

2.4. Determination of α-Amylase Inhibition

The α-amylase activity measurements were performed at 37°C using 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl α-D-maltotroside (CNPG3) as a substrate [21]. The α-amylase hydrolyzes the CNPG3 substrate into 2-chloro-4-nitrophenyl α-D-maltotroside, 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol, maltrioside, and glucose. The substrate was prepared in 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.95, containing 6.7 mM NaCl) and diluted to maintain the 375 μM concentration. The α-amylase was prepared and diluted to 1.5 units/mL by dissolving in the same buffer. Plant extracts were dissolved in DMSO by using a vortex machine and prepared 5000-50 μg/mL by serial dilution. The positive control acarbose was also prepared in the same way.

The 80 μL of α-amylase solution (1 μg/mL in phosphate buffer at pH 6.9) was added to 20 μL of plant sample, positive control, and negative control, respectively, in triplicate. The reaction mixture was then incubated at 37°C for 15 min and the initial reading was taken by measuring absorbance at 405 nm. After 15 min, the 100 μL substrate was added to the reaction mixture of sample and α-amylase. The progress of reaction was monitored by measuring the release of 2-chloro-4-nitrophenol spectrophotometrically. The absorbance was measured at 405 nm in a 96-well plate (Synergy LX, BioTek, Instruments, Inc., USA) The inhibition of methanolic crude extract, hexane fraction, dichloromethane fraction, and ethyl acetate fraction from the bark was recorded. The enzyme inhibition was calculated by the formula:

| (1) |

The IC50 value was calculated by using software “GraphPad Prism.”

2.5. Molecular Docking Studies

2.5.1. Determination of Ligands and Receptors

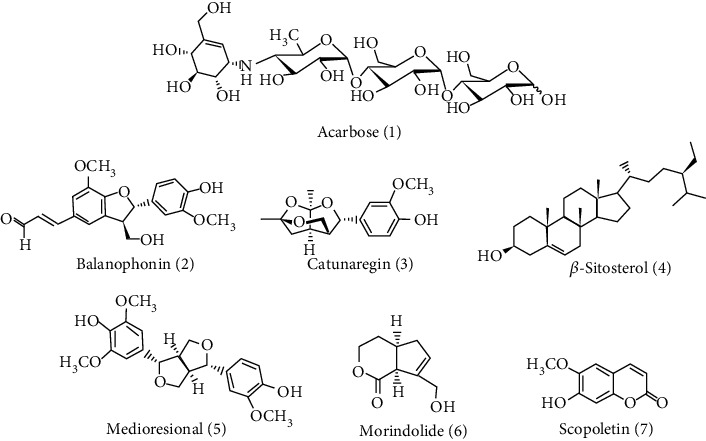

The library of more than 37 known isolated compounds from the stem bark of C. spinosa was prepared from the extensive literature survey. The bioactive compounds were of different classes such as lignans, coumarins, isocoumarins, and saponins. The compounds were selected based on their molecular weight (<500 g/mol) and previous in vitro and in silico studies [22]. These compounds were balanophonin (2) [7], catunaregin (3) [23, 24], β-sitosterol (4) [25], medioresinol (5), morindolide (6), and scopoletin (7) [7], which are listed with their physicochemical properties in Table 1, and their chemical structures are presented in Figure 3.

Table 1.

Physicochemical properties of selected compounds.

| S.N. | Compound | PubChem CID | Molecular weight (g/mol) | Molecular formula | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acarbose | 41774 | 645.6 | C25H43NO18 | [26] |

| 2. | Balanophonin | 23252258 | 356.4 | C20H20O6 | [7, 27] |

| 3. | Catunaregin | 45258336 | 292.33 | C16H20O5 | [23, 24] |

| 4. | β-Sitosterol | 222284 | 414.7 | C29H50O | [25] |

| 5. | Medioresinol | 181681 | 388.4 | C21H24O7 | [7, 27] |

| 6. | Morindolide | 10397184 | 168.19 | C9H12O3 | [7, 27] |

| 7. | Scopoletin | 5280460 | 192.17 | C10H8O4 | [7, 27] |

Figure 3.

Chemical structures of acarbose and selected compounds for molecular docking.

The structure of the selected compounds along with the standard acarbose was either drawn in the ChemDraw and was converted to 3D or downloaded from the PubChem database. Finally, the structures were transformed to a .pdb file format, which is readable by BIOVIA Discovery Studio.

Compared to other amylases, the homology modeling of porcine and human pancreatic α-amylase is very similar at about 87.1% [28, 29]. The porcine pancreatic α-amylase (PDB ID:1OSE) was chosen for the molecular docking analysis. The three-dimensional structure of the protein was obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) in the .pdb file format [22].

2.5.2. Ligand and Receptor Preparation

The protein complexed with acarbose was downloaded from the Protein Data Bank (http://www.rcsb.org/pdb) and prepared using BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer 2020 [22]. The water, ligands, and other heteroatoms were removed, and polar hydrogen was added after defining the binding site of the already bound ligand [30]. The attributes were noted before removing the already complex ligand.

The ligand was downloaded from the PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). They were optimized for docking by adjusting the torsion tree and were saved in the .pdbqt file format using the AutoDock tool [31].

2.5.3. Determination of Active Sites

The active site was determined by several bases such as the interacting site of already complexed (cocrystallized) ligands [32], the sites reported from similar previous studies as well as blind docking. The grid box was prepared by using the AutoDock tool, and the receptor grid center was placed in the receptors' active site residue. The amino acid determined in the active site was used to evaluate the result of our docking study. For the blind docking, the grid box was made maximum to cover the whole part of the receptor, allowing the ligand to be docked in all parts of the receptor [33].

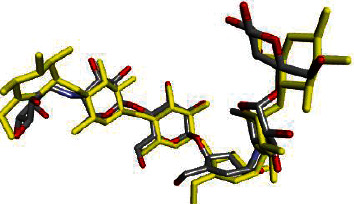

2.5.4. Molecular Docking

Molecular docking studies were performed by using AutoDock Vina [31]. The configuration file was generated defining the attributes such as evaluation of grid box coordinates and size. The obtained grid box was as follows: X = 35.661954, Y = 37.373877, and Z = −1.203215; and the size was X = 30, Y = 30, and Z = 30, energy range = 3, and exhaustiveness = 8. The output file in the .pdbqt format and the log file in the .txt format were written in the configuration file. The docking studies were validated by the superimposing of cocrystallized ligands (Figure 4) extracted from cocrystals and redocked with the same 1OSE receptor with its RMSD value < 2 Å [34].

Figure 4.

Superimposing of cocrystallized ligands extracted (yellow) and redocked ligand (grey-red) with RMSD value < 1 Å.

The studies were performed for the selected compounds along with the standard acarbose. After docking the best pose with the lowest B.E. (Kcal/mol) and the highest number of H-bonding, it was selected for further visualization. The binding interactions between ligands and receptors were visualized by the BIOVIA Discovery Studio Visualizer.

2.6. Pharmacokinetic and ADMET Profile

In the pharmaceutical industry, drug-likeness, ADMET, and target profiles of potential hit compounds are critical in reducing side effects [35]. In the current analysis, the pharmacokinetic properties were predicted by web-based application swissADME (https://www.swissadme.ch) [36]. The drug-likeness properties are determined by the rule of five, also called Lipinski's rule. When there are more than 5 H-bond donors and 10 H-bond acceptors, the molecular weight (MWT) is greater than 500, and the measured Log P (CLogP) is greater than 5 (or MlogP > 4.15); weak absorption or permeation is more possible [37, 38]. This idea is related to the SLIPPER-2001 program, which employs physicochemical descriptors and molecular similarities to forecast properties like lipophilicity, solubility, and fraction absorbed in humans [39]. The toxicity analysis was done by a similar web-based application ProTox-II [40]. Several parameters such as bioavailability, brain penetration, oral absorption, carcinogenicity, immunotoxicity, and human intestinal absorption properties were calculated for all active compounds. Toxicity is important to consider while developing drugs because it aids in assessing the toxic dosage in animal model experiments and reduces the number of animal model studies [41, 42].

3. Results

3.1. α-Amylase Inhibition

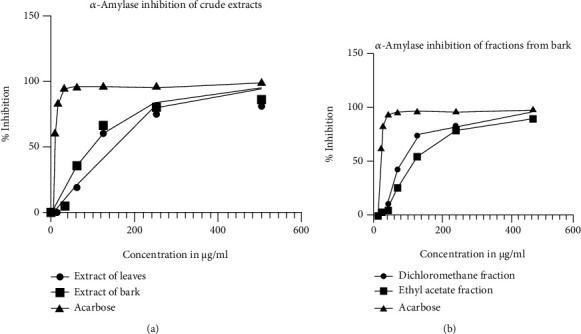

The extracts of leaves and bark of C. spinosa were both potent towards α-amylase inhibition activity. Among the fractions of bark extract, dichloromethane and ethyl acetate fractions showed good α-amylase inhibition activity in the screening result at 500 μg/mL and hexane fraction was less potent.

The graphical presentations (Figure 5) for inhibition and IC50 values of all extracts and fractions were compared to that of acarbose.

Figure 5.

A plot for α-amylase inhibition of (a) crude extracts and (b) acarbose and extracts from bark and acarbose.

The graphical trend of % inhibition against concentration was similar to that of standard acarbose indicating α-amylase inhibition activity of the giving extract. The IC50 values obtained for the extracts are tabulated in Table 2.

Table 2.

IC50 values of plant extracts, fractions, and standard acarbose.

| Plant extract | IC50 (μg/mL, mean ± SEM) |

|---|---|

| Extract of leaves | 119.70 ± 2.79 |

| Extract of bark | 94.66 ± 2.19 |

| Dichloromethane fraction of extract of bark | 77.17 ± 1.75 |

| Ethyl acetate fraction of extract of bark | 116.00 ± 1.60 |

| Acarbose | 6.34 ± 0.07 |

The crude methanolic extract of leaves had a higher IC50 value of 119.7 ± 2.79 μg/mL than that of crude bark extract, 94.66 ± 2.19 μg/mL showing lower potency. The hexane fraction showed very less inhibition even at the higher dose. The DCM fraction and ethyl acetate fraction had an IC50 value of 77.17 ± 1.75 and 116 ± 1.60 μg/mL, respectively, compared to the standard acarbose whose IC50 was 6.34 ± 0.07 μg/mL.

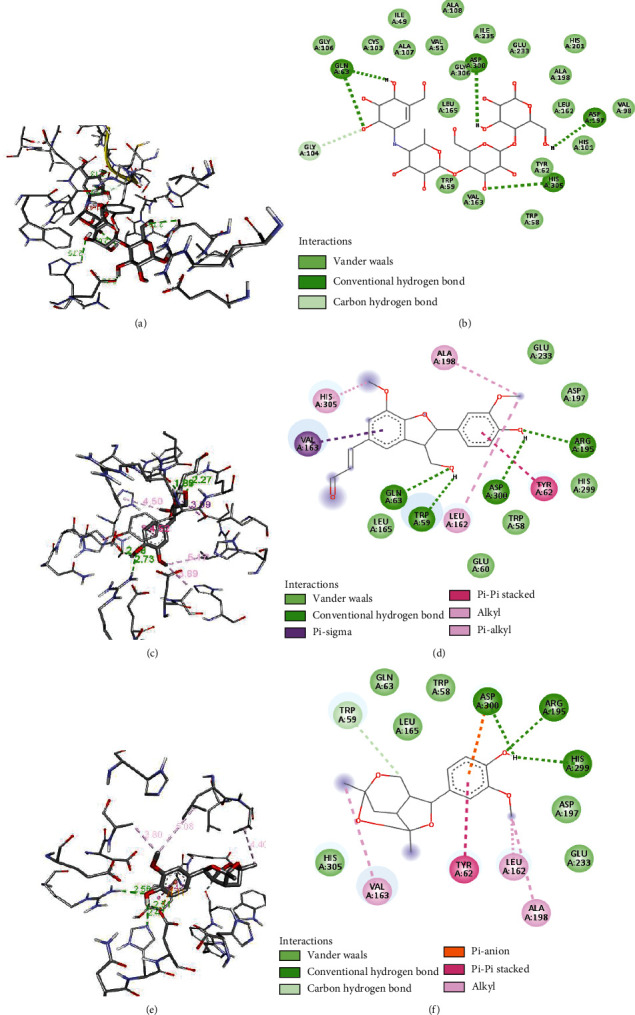

3.2. Molecular Docking Analysis

The careful investigation of cocrystallized ligand interaction BIOVIA Discovery Studio revealed that the catalytic residue contains H-bonding with ASP-300, GLU-233, GLY-306, HIS-299, HIS-305, ASP-197, HIS-101, TRP-59, GLN-63, VAL-163, GLY-164, SER-105, GLY-106, and LYS-200 which is similar to that of previously reported active residue interacting with the acarbose, a competitive inhibitor of α-amylase [43].

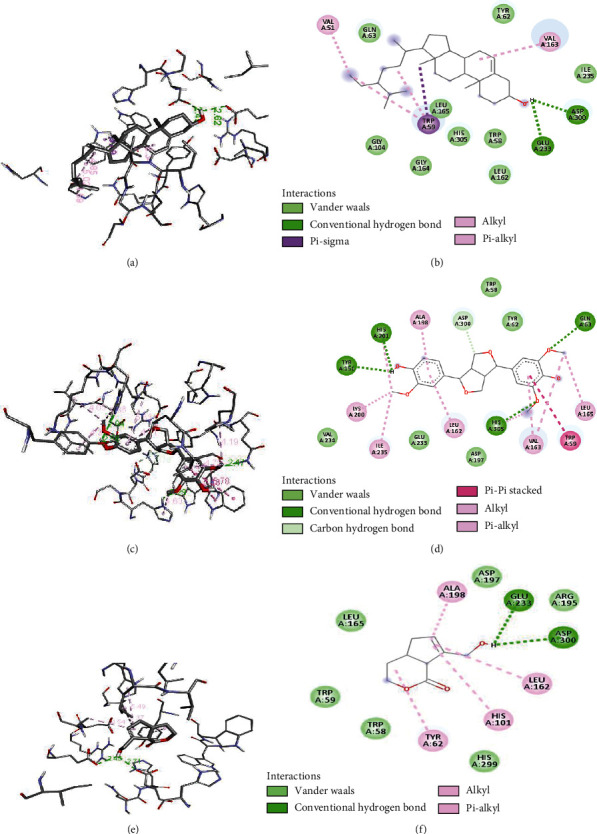

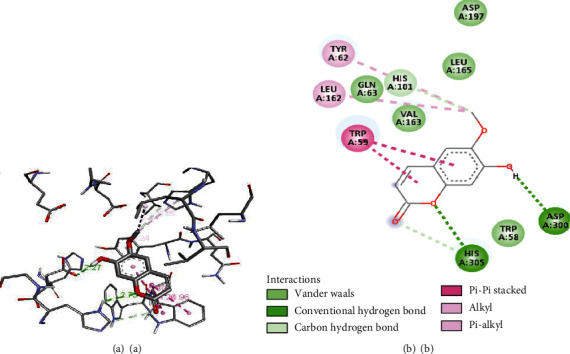

The results of docking score met well with the in vitro analysis. The binding affinity (docking score) and H-bonding catalytic residue for all selected compounds against porcine pancreatic α-amylase (PDB ID: 1OSE) are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Docking score results for porcine pancreatic amylase (PDB ID: 1OSE) receptor and selected ligands.

| S.N. | Ligand | Docking score (kcal/mol) | Binding features (H-bond length in Å) with active site residue |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acarbose | -8.0 | ASP-300 (2.40 Å), HIS-305 (2.73 Å), ASP-197 (2.70 Å), GLN-63 (2.07 Å) |

| 2. | Balanophonin | -8.3 | ARG-195 (2.73 Å), ASP-300 (2.48 Å), TRI-59 (2.27 Å), GLN-63 (2.27 Å) |

| 3. | Catunaregin | -8.1 | ASP-300 (2.51 Å, 4.11 Å), HIS-299 (2.47 Å), ARG-195 (2.56 Å) |

| 4. | β-Sitosterol | -8.9 | ASP-300 (2.45 Å), GLU-233 (2.62 Å) |

| 5. | Medioresinol | -8.5 | HIS-201 (2.94 Å), TYR-151 (2.88 Å), HIS-305 (2.29 Å), GLN-63 (2.47 Å) |

| 6. | Morindolide | -6.0 | GLU-233 (2.45 Å), ASP-300 (2.71 Å) |

| 7. | Scopoletin | -6.3 | ASP-300 (2.27 Å), HIS-305 (2.73 Å) |

Several other interactions such as pi-pi, van der Waals, and hydrophobic interactions occurred in between the ligands and receptors, whose detailed visualization is presented in Figures 6–8.

Figure 6.

3D (a, c, and e) and 2D (b, d, and f) interactions of protein and (a, b) acarbose, (c, d) balanophonin, and (e, f) catunaregin.

Figure 7.

3D (a, c, and e) and 2D (b, d, and f) interactions of protein and (a, b) β-sitosterol, (c, d) medioresinol, and (e, f) morindolide.

Figure 8.

3D (a) and 2D (b) interactions of protein and (a, b) scopoletin.

3.3. Pharmacokinetic and ADMET Properties

The pharmacokinetics and drug-likeness properties of the docked compounds are tabulated in Table 4. The polar surface area has been widely used as a descriptor of drug transport properties such as intestinal absorption and blood-brain barrier penetration. It is also the number of polar atoms like oxygen, nitrogen, and their attached hydrogens' contributions to the molecular (usually van der Waals) surface region [44]. The standard compound, acarbose (1) violates three rules out of five and rules out from being drug-likeness. Compound 5 violates one rule out of five while all rest compounds were found with no violations indicating better drug-like properties.

Table 4.

Pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties of selected ligands.

| S.N. | Name | No of rotatable bonds | TPSA1 | Consensus log P | LogS (ESOL2) | Drug-likeness (Lipinski's rule) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acarbose | 9 | 321.17 Å | -6.22 | 2.13 | No (3 violations) |

| 2. | Balanophonin | 6 | 85.22 Å | 2.34 | -3.28 | Yes (0 violations) |

| 3. | Catunaregin | 2 | 57.15 Å | 2.09 | -2.88 | Yes (0 violations) |

| 4. | β-Sitosterol | 6 | 20.23 Å | 7.19 | -7.90 | Yes; (1 violations) |

| 5. | Medioresinol | 5 | 86.61 Å | 2.33 | -3.65 | Yes (0 violations) |

| 6. | Morindolide | 1 | 46.53 Å | 0.86 | -0.82 | Yes (0 violations) |

| 7. | Scopoletin | 1 | 59.67 Å | 1.52 | -2.46 | Yes (0 violations) |

TPSA: topological polar surface area; ESOL: estimated aqueous solubility; data source: https://www.swissadme.ch.

The result of ADME analysis by swissADME and toxicity analysis by ProTox-II is tabulated in Table 5.

Table 5.

ADMET profiles of selected compounds.

| S.N. | Compounds | GI Abs. | P-gp substrate2 | BBB permeation | CYP3 inhibition | Hepatotoxicity | Cytotoxicity | Immune toxicity | Toxicity class | Predicted LD50 (mg/kg) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Acarbose | Low | Yes | No | No | — | No | Yes | 6 | 24000 |

| 2. | Balanophonin | High | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | 5 | 5000 |

| 3. | Catunaregin | High | Yes | Yes | Yes (CYP2D6) | No | No | Yes | 4 | 600 |

| 4. | β-Sitosterol | Low | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | 4 | 890 |

| 5. | Medioresinol | High | Yes | No | Yes (CYP2D6) | No | No | Yes | 4 | 1500 |

| 6. | Morindolide | High | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | 5 | 5000 |

| 7. | Scopoletin | High | No | Yes | Yes (CYP1A2) | — | No | — | 5 | 3800 |

4. Discussion

Catunaregam spinosa has been reported for its activity against diabetes in several ethnomedicinal studies; however, the detailed study on α-amylase inhibition has not been carried out to relate the antidiabetic properties. The extracts and compounds present in C. spinosa have not been studied in detail in vitro and in silico studies. The comparative α-amylase inhibiting properties of plant extracts and fractions revealed that the DCM fraction showed more potent behavior than the other fractions. The in vitro α-amylase inhibition analysis was reported for the first time from this plant. This can be related to the previously reported in vivo analysis of the antihyperglycemic activities of methanolic extract of C. spinosa fruit extract in the nicotinamide and streptozotocin-induced male Wistar diabetic rats of which C. spinosa fruit extract (400 mg/kg) decreased the blood sugar level from 106.16 ± 7.8 to 87.5 ± 5.00 mg/dL [18] and in stem bark extract (400 mg/kg) treated group to 94.00 ± 1.577 mg/dL as compared to the diabetic control group [9].

The evaluated docking score and visualization of interactions suggest that the binding affinity and number of H-bonding with the catalytic site of the receptor of selected compounds were comparable. Hydrogen bonding interactions with receptors are essential as they have the organization needed for distinct folding and selectivity which supports the molecular recognition at the ligand-protein interface [45]. Out of the six selected, four compounds 2, 3, 4, and 5 had strong interaction (ΔG ≤ −8.0 kcal/mol) with the receptor. The highest docking score was for compound 4 but with only two H-bonding with active site residue (ASP-300, GLU-233), while compounds 2 and 5 have four H-bonding with active site (ARG-195, ASP-300, TRI-59, and GLN-63) and (HIS-201, TYR-151, HIS-305, and GLN-63), respectively, similar to that of standard compound 1 with H-bonding (ASP-300, HIS-305, ASP-197, and GLN-63). The compounds 6 and 7 have lower binding affinity and a lower number of H-bonding indicating weak interactions. The tested compound 4 has already been studied for its in vivo antidiabetic properties in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats and was found to be effective by 78-100% to lower the blood glucose level [46]. The result showed that except for compounds 1 and 4, all other compounds absorb well in the intestine. Cytochrome CYP450 (1A2, 2C9, 2C19, 2D6, and 3A4), which is primarily responsible for the biotransformation of more than 90% of drugs in phase-1 metabolism, plays a significant role in drug metabolism [47]. Compounds 3 and 5 showed CYP2D6 inhibition, and compound 7 was found to inhibit CYP1A2. Compounds 3, 6, and 7 readily cross the BBB while the rest of the compound was not found to cross the BBB. The toxicity of docked compounds suggests that compounds 1-5 are immune toxic while 6 is not immune toxic. None of the compounds were shown to have hepatotoxicity and cytotoxicity. The toxicity class and predicted LD50 suggest that compound 1 was much safer to use; compounds 2, 6, and 7 were also found to be safer to use than the rest of the compounds.

5. Conclusion

Using in vitro analysis, we found that the dichloromethane fraction fractionated from the methanolic extract of bark of C. spinosa has a high potential of α-amylase inhibition. The fact was supported by a molecular docking study of porcine pancreatic α-amylase protein and various known compounds from the bark of C. spinosa. The interactions with the catalytic sites of the protein and the selected compounds were similar to the interaction of the standard α-amylase inhibitor, acarbose. We have also studied the drug-likeliness of selected compounds and ADMET analysis which shows that the selected compounds follow the drug properties. In the present study, compounds 2, 3, and 5 score high with the lowest binding affinity and a higher number of H-bonding towards the catalytic residue. Thus, the isolation of high-scoring compounds 2, 3, and 5 and their in vivo animal study for antihyperglycemic and antidiabetic properties could further confirm the potential of this compound acting as an antidiabetic drug. This study could be helpful to select the compounds for animal study and increase the efficiency of clinical wet-lab studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the University Grants Commission (UGC), Nepal, for providing a Master's Thesis Support Grant (Grant No. MRS-77/78-S&T-29) to Deepak Timalsina, Central Department of Chemistry, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal. We also acknowledge the National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH) of the Department of Plant Resources, Ministry of Forest and Environment, Kathmandu, Nepal, for the identification of plant.

Abbreviations

- μg/mL:

Micro grams per millilitre

- ADMET:

Absorption distribution, metabolism excretion toxicity

- BBB:

Blood-brain barrier

- CNPG3:

2-Chloro-4-nitrophenyl-α-D-maltotrioside

- DCM:

Dichloromethane

- DMSO:

Dimethyl sulphoxide

- IC50:

Inhibition concentration at 50%

- Kcal/mol:

Kilocalorie per mol

- LD50:

Lethal concentration at 50%

- mg/mL:

Milligram per millilitre

- nm:

Nanometer

- PDB:

Protein Data Bank

- PPA:

Porcine pancreatic α-amylase

- RMSD:

Root mean square deviation

- TPSA:

Topological polar surface area

- μL:

Microlitre.

Contributor Information

Deepak Timalsina, Email: geniusdipu5@gmail.com.

Khaga Raj Sharma, Email: khagaraj_sharma33@yahoo.com.

Data Availability

The data sets to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author and submitting author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest.

Authors' Contributions

D.T. performed the in vitro and in silico experiments and prepared the first draft of the manuscript. D.B. and K.P. supported the in vitro experiment. K.R.S supervised the project. H.P.D. added support in the preparation of the first draft and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

References

- 1.Afifi A. F., Kamel E. A., Khalil A. A., Fawzi M., Housery M. M. Purification and characterization of 0-amylase from. Glob. J. Biotechnol. Biochem. . 2008;3(1):14–21. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kwon Y.-I., Apostolidis E., Shetty K. Evaluation of pepper (capsicum Annuum) for management of diabetes and hypertension. Journal of Food Biochemistry . 2007;31(3):370–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2007.00120.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thilagam E., Parimaladevi B., Kumarappan C., Chandra Mandal S. α-Glucosidase and α-Amylase Inhibitory Activity of _Senna surattensis_. Journal of Acupuncture and Meridian Studies . 2013;6(1):24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jams.2012.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yu Z., Yin Y., Zhao W., et al. Novel peptides derived from egg white protein inhibiting alpha-glucosidase. Food Chemistry . 2011;129(4):1376–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elosta A., Ghous T., Ahmed N. Natural products as anti-glycation agents: possible therapeutic potential for diabetic complications. Current Diabetes Reviews . 2012;8(2):92–108. doi: 10.2174/157339912799424528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Patel Ritesh G., Pathak Nimish L., Rathod Jaimik D., Patel L. D., Bhatt Nayna M. Phytopharmacological properties of Randia dumetorum as a potential medicinal tree: an overview. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. . 2011;1(10):24–26. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gao G., Qi S., Zhang S., et al. Minor compounds from the stem bark of Chinese mangrove associate Catunaregam spinosa. Pharm. - Int. J. Pharm. Sci. . 2008;63(7):542–544. doi: 10.1691/ph.2008.8505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prakash T. D. Madanaphala (Randia dumetorum lam.): a phyto-pharmacological review. Int J Ayurvedic Med . 2015;6(2):74–82. doi: 10.47552/ijam.v6i2.582. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Basini J., Swetha D., Mallikarjuna G. Anti hyperglycaemic and antioxidant activity of Catunaregam spinosa (Thunb) against dexamethasone induced diabetes in rats. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci . 2019:56–61. doi: 10.22159/ijpps.2019v11i6.32563. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chopra R. N., Chopra I. C., Varma B. S. Glossary of Indian medicinal plants; [with] Supplement . New Delhi: Council of Scientific & Industrial Research; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Garg A. K., Singh A., Vishnoi H., Meena G. C., Singh C., Adlakha M. Swine flu- the changing scenario and preparedness with formulation of win flu air freshener gel. Int. J. Ayurveda Pharma Res. . 2017;5(11):14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sotheeswaran S., Bokel M., Kraus W. A hemolytic saponin, randianin, from Randia dumetorum. Phytochemistry . 1989;28(5) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dubois M.-A., Benze S., Wagner H. New biologically active triterpene-saponins from Randia dumetorum. Planta Medica . 1990;56(5):451–455. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-961009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murty Y. L. N., Jairaj M. A., Sree A. Triterpenoids from _Randia dumetorum_. Phytochemistry . 1989;28(1):276–277. doi: 10.1016/0031-9422(89)85058-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sati O. P., Chaukiyal D. C., Nishi M., Miyahara K., Kawasaki T. An iridoid from _randia dumetorum_. Phytochemistry . 1986;25(11):2658–2660. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9422(00)84532-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kandimalla R., Kalita S., Saikia B., et al. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective potentiality of Randia dumetorum Lam. leaf and bark via inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammatory cytokines. Frontiers in Pharmacology . 2016;7:p. 205. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patil M. J., Bafna A. R., Bodas K., Shafi S. In vitro antioxidant activity of fruits of Randia dumetorum Lamk. J. Glob. Trends Pharm. Sci. . 2014;4(5):2103–2107. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mishra P. R., Panda P. K., Chowdary K. A., Panigrahi S. Antidiabetic and antihypelipidaemic activity of Randia dumetorum. Int. J. Res. Pharm. Chem. . 2012;2(3) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Adhikari-Devkota A., Kurauchi Y., Yamada T., Katsuki H., Watanabe T., Devkota H. P. Anti-neuroinflammatory activities of extract and polymethoxyflavonoids from immature fruit peels of Citrus ‘Hebesu. Journal of Food Biochemistry . 2019;43(6, article e12813) doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Q.-W., Lin L.-G., Ye W.-C. Techniques for extraction and isolation of natural products: a comprehensive review. Chinese Medicine . 2018;13 doi: 10.1186/s13020-018-0177-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khadayat K., Marasini B. P., Gautam H., Ghaju S., Parajuli N. Evaluation of the alpha-amylase inhibitory activity of Nepalese medicinal plants used in the treatment of diabetes mellitus. Clin. Phytoscience . 2020;6(1):p. 34. doi: 10.1186/s40816-020-00179-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tallei T. E., Tumilaar S. G., Niode N. J., et al. Potential of plant bioactive compounds as SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) and spike (S) glycoprotein inhibitors: a molecular docking study. Scientifica . 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/6307457.e6307457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu J.-X., Luo M. Q., Xia M., et al. Marine compound catunaregin inhibits angiogenesis through the modulation of phosphorylation of Akt and eNOS in vivo and in vitro. Mar. Drugs . 2014;12(5):2790–2801. doi: 10.3390/md12052790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao G.-C., Luo X. M., Wei X. Y., et al. Catunaregin and epicatunaregin, two norneolignans possessing an unprecedented skeleton fromCatunaregam spinosa. Helvetica Chimica Acta . 2010;93(2):339–344. doi: 10.1002/hlca.200900193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jangwan J. S., Aquino R., Mencherini T., Singh R. Chemical investigation and in vitro cytotoxic activity of Randia dumetorum lamk. Bark. International Journal of Chemical Sciences . 2012;10:1374–1382. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anigboro A. A., Avwioroko O. J., Ohwokevwo O. A., Pessu B., Tonukari N. J. Phytochemical profile, antioxidant, α-amylase inhibition, binding interaction and docking studies of Justicia carnea bioactive compounds with α-amylase. Biophysical Chemistry . 2021;269, article 106529 doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2020.106529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Timalsina D., Devkota H. P., Bhusal D., Sharma K. R. Catunaregam spinosa (Thunb.) Tirveng: a review of traditional uses, phytochemistry, pharmacological activities, and toxicological aspects. Evidence-based Complementary and Alternative Medicine . 2021;2021 doi: 10.1155/2021/3257732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perera W. H., Shivanagoudra S. R., Pérez J. L., et al. Anti-inflammatory, antidiabetic properties and in silico modeling of cucurbitane-type triterpene glycosides from fruits of an Indian cultivar of Momordica charantia L. Molecules . 2021;26(4):p. 1038. doi: 10.3390/molecules26041038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian M., Spinelli S., Driguez H., Payan F. Structure of a pancreatic alpha-amylase bound to a substrate analogue at 2.03 A resolution. Protein Sci. Publ. Protein Soc. . 1997;6(11):2285–2296. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560061102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad S., Abbasi H. W., Shahid S., Gul S., Abbasi S. W. Molecular docking, simulation and MM-PBSA studies of nigella sativa compounds: a computational quest to identify potential natural antiviral for COVID-19 treatment. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2020;39(12):1–9. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1775129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Trott O., Olson A. J. AutoDock Vina: improving the speed and accuracy of docking with a new scoring function, efficient optimization and multithreading. Journal of Computational Chemistry . 2010;31(2):455–461. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swargiary A., Mahmud S., Saleh M. A. Screening of phytochemicals as potent inhibitor of 3-chymotrypsin and papain-like proteases of SARS-CoV2: an in silico approach to combat COVID-19. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2020;21:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1835729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adejoro I. A., Babatunde D. D., Tolufashe G. F. Molecular docking and dynamic simulations of some medicinal plants compounds against SARS-CoV-2: an in silico study. J. Taibah Univ. Sci. . 2020;14(1):1563–1570. doi: 10.1080/16583655.2020.1848049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nawaz M., Taha M., Qureshi F., et al. Structural elucidation, molecular docking, α-amylase and α-glucosidase inhibition studies of 5-amino-nicotinic acid derivatives. BMC Chem. . 2020;14(1):p. 43. doi: 10.1186/s13065-020-00695-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Istifli E. S., Netz P. A., Tepe A. S., Husunet M. T., Sarikurkcu C., Tepe B. In silico analysis of the interactions of certain flavonoids with the receptor-binding domain of 2019 novel coronavirus and cellular proteases and their pharmacokinetic properties. Journal of Biomolecular Structure & Dynamics . 2020;26:1–15. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1840444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Daina A., Michielin O., Zoete V. SwissADME: a free web tool to evaluate pharmacokinetics, drug-likeness and medicinal chemistry friendliness of small molecules. Scientific Reports . 2017;7(1) doi: 10.1038/srep42717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Benet L. Z., Hosey C. M., Ursu O., Oprea T. I. BDDCS, the rule of 5 and drugability. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews . 2016;101:89–98. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lipinski C. A., Lombardo F., Dominy B. W., Feeney P. J. Experimental and computational approaches to estimate solubility and permeability in drug discovery and development settings. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews . 2001;46(1–3):3–26. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00129-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.van de Waterbeemd H., Gifford E. ADMET _in silico_ modelling: towards prediction paradise? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. . 2003;2(3):192–204. doi: 10.1038/nrd1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Banerjee P., Eckert A. O., Schrey A. K., Preissner R. ProTox-II: a webserver for the prediction of toxicity of chemicals. Nucleic Acids Res . 2018;46(W1):W257–W263. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sripriya N., Ranjith Kumar M., Ashwin Karthick N., Bhuvaneswari S., Udaya Prakash N. K. In silico evaluation of multispecies toxicity of natural compounds. Drug and Chemical Toxicology . 2019;44:1–7. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2019.1614023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marahatha R., Basnet S., Bhattarai B. R., et al. Potential natural inhibitors of xanthine oxidase and HMG-CoA reductase in cholesterol regulation: in silico analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. . 2021;21(1) doi: 10.1186/s12906-020-03162-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lo Piparo E., Scheib H., Frei N., Williamson G., Grigorov M., Chou C. J. Flavonoids for controlling starch digestion: structural requirements for inhibiting human alpha-amylase. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry . 2008;51(12):3555–3561. doi: 10.1021/jm800115x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prasanna S., Doerksen R. J. Topological polar surface area: a useful descriptor in 2D-QSAR. Current Medicinal Chemistry . 2009;16(1):21–41. doi: 10.2174/092986709787002817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Baker E. N., Hubbard R. E. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology . 1984;44(2):97–179. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(84)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gupta R., Sharma A. K., Dobhal M. P., Sharma M. C., Gupta R. S. Antidiabetic and antioxidant potential of β-sitosterol in streptozotocin-induced experimental hyperglycemia. Journal of Diabetes . 2011;3(1):29–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-0407.2010.00107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Šrejber M., Navrátilová V., Paloncýová M., et al. Membrane-attached mammalian cytochromes P450: An overview of the membrane's effects on structure, drug binding, and interactions with redox partners. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry . 2018;183:117–136. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2018.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data sets to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author and submitting author upon request.