Abstract

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers and an important cause of cancer-related mortality. Recent advances in targeted therapy and immunotherapy have improved outcomes, but these have limited penetration in resource-constrained situations. We report the real-world experience in treating patients with lung cancer in India. A retrospective analysis of baseline characters, treatment and outcomes of patients with lung cancer seen between January 2015 to December 2018 ( n = 302) at our center was carried out. Survival data were censored on July 31, 2019. A total of 302 patients (median age: 57 years [range, 23–84 years]; males [ n = 203; 67.2%]) were registered. Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology ( n = 225, 75%). The testing rate of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) mutation analysis in stage IV adenocarcinoma ( n = 191) was 67% and 63%, respectively. Systemic therapy (chemotherapy/gefitinib) was started after a median of 62 days (range, 1–748) from presentation and 38 days (range, 1–219 days) from diagnosis. The median progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were 4.3 months (95% CI, 3.2–5.4) and 9.0 months (95% CI, 7.6–10.5), respectively in the 141 patient without targetable mutations who started palliative chemotherapy. Of the 58 patients who tested positive for EGFR mutation, 41 (71%) started an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI), and the median PFS and OS in these patients were 8.5 months (95% CI, 5.6–11.4) and 18.4 months (95% CI, 12.2–24.6), respectively. Only 1 out of 10 patients with stage IV ALK -positive adenocarcinoma was started on ALK inhibitor. On multivariate analysis of OS for patients who started on palliative chemotherapy, response to first-line treatment, long distance from the center, use of second line therapy, and a delay of > 40 days from diagnosis to treatment predicted improved survival. Despite providing free diagnostic and treatment services, there was considerable delay in therapy initiation, and a significant proportion of treatment noninitiation and abandonment. Measures should be taken to understand and address the causes of these issues to realize the benefits of newer therapies The apparent paradox of improved survival in those with long delay in initiation of treatment could be explained based on a less aggressive disease biology.

Keywords: Lung cancer, Chemotherapy, targeted therapy, outcomes, delay in treatment

Prasanth Ganesan

Introduction

Lung cancer is one of the most common cancers and causes of cancer-related mortality. 1 In India, lung cancer accounts for 7% of new cancer cases and 9% of cancer-related mortality. 2 Most patients have advanced and incurable disease at diagnosis, leading to high mortality. Two significant advances in therapy of lung cancer have been the advent of targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Targeted therapy against the mutated epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and the mutated anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK) protein has been associated with improvements in survival from about a year (with only chemotherapy) to 2 to 3 years. Immunotherapy is a more recent addition, which can be applied to the nonmutated cancers and results in improving the survival of patients. 3 Although the outcomes across the world have seemingly improved with these innovations, limitations of cost, testing facility, and availability of medications mean that these have limited penetration in India. There are other challenges which are unique to the Indian context such as high population density, illiteracy, delayed presentation, lack of resources for molecular testing, and nonavailability of standard therapy. 4 5

At our governmental center, although many medicines are available free of cost to the patients, significant challenges exist. Testing for mutations is limited and newer tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) and immunotherapy medications are not available. To understand these challenges better, we undertook an audit of lung cancer outcomes from our center. We wanted to understand the presentation of patients, delays involved in diagnosis and treatment, patterns of care, and outcomes. An understanding of these issues will allow designing interventions to improve outcomes. This will also serve as a baseline database to compare future therapies as and when they are available and implemented.

Methods

Diagnosis and Staging

After obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics committee, we retrospectively analyzed the records of 302 patients with lung cancer registered in our department from January 2015 to December 2018 (4 years). The demographic profile, presenting features, treatment details, and survival outcomes were entered in a predesigned proforma. The diagnosis of lung cancer was established by biopsy or fine-needle aspiration/fluid cytology (+/− cell blocks/immunohistochemistry [IHC]). Most patients were staged with contrast enhanced computerized tomography (CECT) of thorax and abdomen and bone scan. Few patients underwent positron emission tomography (PET) CT scans in this period. For this analysis, we went through the radiology reports and restaged the patients based on the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) 8th edition.

Molecular analysis of EGFR and ALK mutations was done whenever feasible. Since it was not available within our institution, it was outsourced to a certified laboratory. As funding support for the test could not be arranged at all times, and some patients could not afford to pay for the test, this data was missing in many patients.

Treatment Protocols and Subsequent Follow-Up

Chemotherapy for advanced disease : During 2014–15, metastatic adenocarcinoma lung was treated with gemcitabine/carboplatin because of an ongoing project. From May 2016, most patients with adenocarcinoma were treated with pemetrexed/carboplatin (4-6 cycles) and paclitaxel/carboplatin doublet was used in stage IV squamous cell carcinoma. Extensive stage small cell lung carcinoma was treated with six cycles of carboplatin/etoposide. Attempts were made to use pemetrexed maintenance in those with partial response (PR) and stable disease (SD) after pemetrexed/carboplatin doublet in stage IV adenocarcinoma.

Patients with known EGFR mutations were treated with gefitinib. Similarly, the small number of patients tested positive for ALK mutations were treated with ALK inhibitors whenever the drug could be arranged.

Reassessment was usually done at the end of 3-4 cycles with imaging studies as appropriate (CECT scan). After completion of treatment, patients were followed up every 3 months with a chest X-ray and CECT thorax/abdomen every 6 months unless they had clinical progression.

Localized disease treated with curative intent : Those with stage I and II disease with no contraindications for surgery underwent upfront surgery, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy as indicated. Others were treated with a combination of chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and surgery was done in resectable patients with no medical contraindications.

Data Analysis

Since we were concerned regarding the delays before the start of treatment in our center, we looked into the possible areas causing the delay. Similarly, to understand the impact of long travel on delay and compliance with treatment, we used the pin code of the patient to calculate the distance from our center. Survival outcomes were calculated for those patients who had received at least one cycle of chemotherapy. Telephone calls were made to update the survival data of patients who were lost to follow-up. Patients who were alive and lost to follow-up were censored, based on the dates when they were last known to be alive.

Progression-free survival (PFS) was calculated from the date of initiation of treatment until documented radiological or clinical progression. Overall survival (OS) was calculated from the date of the start of treatment till the date of last follow-up or death. Data was censored on the date of the last follow up or on July 31, 2019, whichever was earlier. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to analyze PFS and OS, and the risk factors were compared using the log-rank test for univariate analysis and a Cox proportional hazards model for multivariate analysis. SPSS 16.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline Features

A total of 302 patients (median age: 57 years [range, 23–84 years]; males [ n = 203; 67.2%]) were registered in our department during the study period ( Table 1 ). Most of them had a performance status of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 1 or 2 ( n = 226, 75%). The median duration of symptoms before presentation was 3 months (range, 1–24 months). More than half of the patients were smokers ( n = 152, 53%). It took a median of 62 days (range, 1–748) and 38 days (range, 1–219 days) to start treatment from the time of presentation and from the time of diagnosis, respectively. Histopathological diagnosis was available in 75% ( n = 225) of the patients, and the rest were diagnosed by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or fluid cytology. Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology ( n = 225, 75%), followed by squamous cell carcinoma ( n = 41, 14%). Stage IV disease was seen in 81% ( n = 244) patients. Only 8 (2.6%) patients had stage I or stage II disease. The testing rate of EGFR and ALK mutation analysis in stage IV adenocarcinoma ( n = 191) was 67% and 63%, respectively. EGFR and ALK mutation results were available in 128 and 123 patients, respectively, of which 58 (45.3%) patients tested positive for EGFR mutation and 13 (10.5%) patients tested positive for ALK mutation. The most common EGFR mutation was exon19 deletion ( n = 37, 64%), followed by exon21 L858R mutation ( n = 14, 24%).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics (n = 302).

| Parameter | n (%) | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: ALK, anaplastic lymphoma kinase; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncological Group; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor. a Classification was based on biopsy and histopathology in 226 (75%) and based on fluid cytology or fine-needle cytology in 76 (25%). b Nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC) not otherwise specified (NOS) ( n = 11), undifferentiated ( n = 6). | ||

| Age, median | 57 (23–84 years) | |

| Sex, male | 203 (67%) | |

| Symptom duration | 3 months (1–24) | |

| Time factor | ||

| Time from presentation to start of treatment | 62 days (1–748) | |

| Time from diagnosis to start of treatment | 38 days (1–219) | |

| From onset of symptoms to presentation | 120 (15–748) | |

| Performance status | ||

| ECOG 1 | 128 (42) | |

| ECOG 2 | 98 (33) | |

| ECOG 3 | 72 (24) | |

| ECOG 4 | 4 (1) | |

| Distance from the centre (kms) | ||

| < 100 | 53 (18) | |

| 100–400 | 107 (35) | |

| 400–1000 | 116 (38) | |

| > 1000 | 26 (9) | |

| Stage | ||

| I, II | 8 (3) | |

| III | 50 (17) | |

| IV | 244 (81) | |

| Histology a | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 225 (75%) | |

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 41 (14%) | |

| Small cell carcinoma | 19 (6%) | |

| Others b | 17 (5%) | |

| EGFR mutation present (tested = 128) | 58 (45%) | |

| ALK translocation present (tested = 123) | 12 (10%) | |

Treatment and Responses

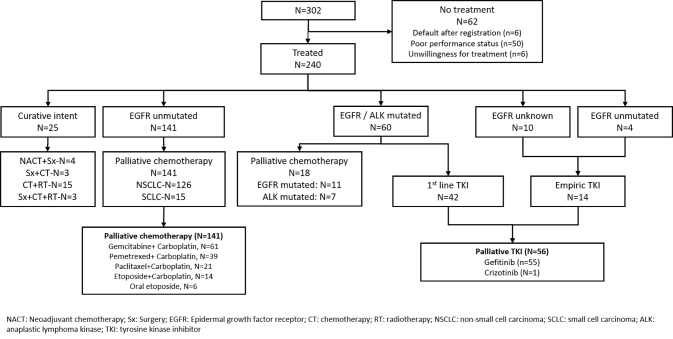

Of the 302 patients registered, only 240 received therapy, of which 25 received curative-intent treatment ( Fig. 1 ). Of the remaining 215 patients who were eligible for palliative intent systemic therapy, 141 had no identified targetable mutation (not tested/tested negative) and received chemotherapy as first-line treatment. Among the other 74, 41 patients with known EGFR mutations received gefitinib and 1 patient with an ALK mutation received crizotinib. Eighteen patients, despite having targetable mutations, received only chemotherapy (either due to inability to afford the cost of treatment or because the results of the mutation were available only at a later date). An additional 14 patients, who were either EGFR unmutated or status unknown, received gefitinib by physician choice, as they were considered unfit to receive chemotherapy.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart depicting the disposition of patients.

Palliative Intent Therapy—In patients without known mutations

The details of chemotherapy regimens are given in Fig. 1 . The median number of chemotherapy cycles administered was 4 (range, 1–23). Eighty-six (61%) patients received four or more cycles of chemotherapy, including 12 patients who received maintenance pemetrexed.

Among the 141 patients (without known mutations) who started chemotherapy, 24 defaulted or stopped due to poor tolerance after one cycle and response evaluation was not possible. Another nine patients received two cycles and defaulted before response assessment. Of the 108 patients who could be evaluated, response was partial (PR) in 46 (42.5%), stable (SD) in 16 (15%), and progressive (PD) in 46 (42.5%). Response rates were similar across the different regimens. Of the 96 patients with nonsmall cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), the clinical benefit rates (PR+SD) were 50%, 37%, and 53% for pemetrexed/platinum, paclitaxel/platinum and gemcitabine/platinum. The clinical benefit rates with chemotherapy for small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC, N=12) with etoposide/platinum was 69% Twelve out of 39 patients (31%) who were treated with pemetrexed-platinum doublet started pemetrexed maintenance after SD/PR. Considering all patients who started chemotherapy ( n = 141) in an “intention-to-treat” manner, the overall response rate was 46/141 (32%).

Survival analysis was done for all the 141 patients who started on chemotherapy. After a median follow-up of 7.1 months (0.07–18.3), 130 patients progressed and 104 died. The median PFS was 4.3 months (95% CI, 3.2–5.4) and OS was 9.0 months (95% CI, 7.6–10.4). The median PFS in patients who received at least two cycles of chemotherapy was 5.8 months (95% CI, 4.8–6.8). The median OS in NSCLC and SCLC was 8.7 months (95% CI, 7.1–10.2) and 9.03 months (95% CI, 6.7–12.5), respectively.

Among those who progressed ( n = 130), only 34 received second-line therapy in the form of docetaxel ( n = 22), gemcitabine/carboplatin ( n = 2), vinorelbine ( n = 1), oral etoposide ( n = 1), nivolumab ( n = 2), gefitinib ( n = 4) and irinotecan in SCLC ( n = 2).

Palliative Intent Therapy—Patients with Targetable Mutations

EGFR mutated patients: Of the 58 patients who tested positive for EGFR mutation, 41 (71%) started on EGFR TKI (38 gefitinib, 2 erlotinib, and one osimertinib) and 11 patients (19%) received first-line chemotherapy (8 of them received EGFR TKI as maintenance or as second-line treatment) and 6 patients (10%) received no treatment. Among those treated with first-line EGFR TKIs, the median PFS was 8.5 months (95% CI, 5.6–11.4) and the median OS was 18.4 months (95% CI, 12.2–24.6).

Apart from these, 14 patients started on first-line empiric gefitinib because of poor performance status. Among these 14 patients, four subjects did not have any EGFR mutation and the mutational status was unknown in the rest of them. The OS in this group of patients was 7.7 months (95% CI, 2.6–12.8)

ALK-positive patients: 12 patients were identified to be ALK mutation-positive. Of these, 2 had received no treatment, 2 were treated with radical intent therapy, and 7 received first-line chemotherapy. Only 1 patient received an ALK inhibitor as first-line therapy. One patient received ALK inhibitor as second-line therapy after progressing on chemotherapy.

Factors Affecting Outcomes

Presence of comorbidities, response to therapy, longer distance from our center, use of second-line, and use of maintenance therapy predicted better survival on univariate analysis ( Table 2 ). On multivariate analysis, response to first-line treatment, long distance from the center, use of second-line therapy, and a delay of > 40 days from diagnosis to treatment predicted improved survival ( Table 3 ).

Table 3. Multivariate analysis of OS for patients who received palliative chemotherapy (n = 141).

| Variable | Hazard ratio (OS) |

95% CI | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncological Group; NA, not available; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease. | |||

| ECOG | |||

| 1 | 1.00 | 0.44 | |

| 2 | 1.17 | 0.78–1.75 | |

| No of extrathoracic metastases | |||

| 0.1 | 1.00 | 0.19 | |

| > 1 | 1.19 | 0.91–1.56 | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| No | 1.00 | 0.08 | |

| Yes | 1.45 | 0.96–2.21 | |

| Distance from center | |||

| > 400 km | 1.00 | 0.01 | |

| < 400 km | 3.73 | 1.34–10.41 | |

| Delay from diagnosis to treatment | |||

| > 40 days | 1.00 | 0.04 | |

| ≤ 40 days | 1.51 | 1.10–2.31 | |

| Response to chemotherapy | |||

| SD/PR | 1.00 | < 0.01 | |

| PD/NA | 4.56 | 2.82–7.37 | |

| Maintenance received | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | 0.56 | |

| No | 1.18 | 0.67–2.08 | |

| Received second-line treatment | |||

| Yes | 1.00 | < 0.01 | |

| No | 3.28 | 1.95–5.53 | |

Table 2. Univariate analysis of OS for patients who received palliative chemotherapy (n = 141).

| Variable | n (%) | Median OS in months (95% CI) | p -value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbreviations: NA, not available; NSCLC, nonsmall cell lung carcinoma; OS, overall survival; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SCLC, small cell lung carcinoma; SD, stable disease. a Extrathoracic metastatic sites. b Among those patients without known mutations treated with chemotherapy ( N =141). | |||

| Age | |||

| > 60 years | 47 (33) | 8.3 (6.3–10.3) | 0.91 |

| < 60 years | 94 (67) | 9.8 (7.3–12.2) | |

| Smoking | |||

| Yes | 87 (62) | 8.3 (6.4–10.2) | 0.76 |

| No | 54 (38) | 10.1 (7.9–12.3) | |

| Comorbidities | |||

| Yes | 51 (36) | 6.9 (4.2–9.6) | 0.03 |

| No | 90 (64) | 10.1 (8.1–12.1) | |

| Histology | |||

| NSCLC | 126 (89) | 8.7 (7.1–10.2) | 0.96 |

| SCLC | 15 (11) | 9.03 (6.7–12.7) | |

| Number of metastases a | |||

| > 2 | 17 (12) | 7.9 (6–10) | 0.03 |

| 1 | 58 (41) | 7 (4.3–9.8) | |

| 0 | 66 (47) | 12.1 (8.3–16) | |

| ECOG | |||

| 2 | 72 (51) | 8.3 (5.8–10.8) | 0.08 |

| 1 | 69 (49) | 9.2 (5.4–12.9) | |

| Distance from centre | |||

| < 400 km | 127 (90) | 8.3 (6.7–9.9) | 0.01 |

| > 400 km | 14 (10) | 26.7 (NA) | |

| Delay from diagnosis to treatment | |||

| ≤ 40 days | 78 (55) | 7.3 (5.0–9.6) | 0.14 |

| > 40days | 63 (45) | 9.7 (7.8–11.7) | |

| Stage | |||

| III | 20 (14) | 5.3 (4.6–6.1) | 0.42 |

| IV | 121 (86) | 9.2 (7.7–10.6) | |

| Regimen b | |||

| Others | 20 (12) | 8.3 (6.3–10.5) | 0.48 |

| Pemetrexed+Carboplatin | 39 (29) | 9.1 (4.6–13.5) | |

| Paclitaxel+Carboplatin | 21 (14) | 9.8 (3.5–16) | |

| Gemcitabine+Carboplatin | 61 (45) | 9.6 (7.8–11.4) | |

| Response to chemotherapy | |||

| PD/NA | 80 (57) | 5.2 (4–6.5) | <0.001 |

| PR + SD | 61 (43) | 14.2 (12.2–16.2) | |

| Maintenance received | |||

| No | 117 (83) | 7.2 (5.4–9) | 0.02 |

| Yes (pemetrexed) | 12 (8.5) | 18.2 (10.5–25.8) | |

| Yes (gefitinib) | 12 (8.5) | 10.8 (4.5–17) | |

| Received second-line treatment | |||

| No | 107 (76) | 7.2 (5.2–9.1) | 0.001 |

| Yes | 34 (24) | 13.4 (10.4–16.5) | |

Curative Intent Therapy

Of these 25 patients, the radical treatment was surgery in 7 patients, concurrent chemoradiotherapy (CCRT) in 15 patients, and a combination of surgery and radiotherapy in 3 patients. Among these 25 patients, 3 patients received adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery and all others received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. After a median follow-up of 17 months in this group, 11 patients progressed, and 6 patients died. The median PFS and OS among those treated with radical intent have not been reached at the time of analysis.

Discussion

Our patients with lung cancer are unique in two aspects—most of them came from very poor socioeconomic backgrounds, and the treatment, for the most part, was provided free of cost. We found significant delays in presentation and start of therapy in these patients. Many of the patients could not get molecular testing done, due to the nonavailability of the same in our center. Around 20% of the registered patients did not receive any form of treatment, mainly due to poor performance status and a few defaulted after registration. There were two unexpected findings in our analysis. One, patients coming from distances of > 400 kilometers had improved survival in the palliative chemotherapy cohort. The second was the finding of no impact of delays in the start of treatment on outcomes.

The baseline data from our center is similar to other reports from India. The median age of 57 years was comparable to other Indian studies 3 4 but a decade younger compared to Western studies. 8 9 Adenocarcinoma was the most common histology, constituting 75% and was slightly higher compared to previous Indian studies. 10 11 This could probably be attributed to the increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma 12 and increased confirmation of histology with IHC. The proportion of “unknown histology” was only 6% in our study as compared to 20 to 25% in previous studies. 6 7 The number of females (33%) and nonsmokers were relatively higher in our study compared to other studies, 6 7 11 which are again associated with adenocarcinoma lung. 13 14 Since this is a retrospective audit of patients who were referred for therapy to our center, it is possibly enriched for females and nonsmokers, which could also explain the higher proportion of adenocarcinomas.

Majority of the patients (81%) presented with the metastatic disease, which is one of the highest proportions of stage IV cancers reported. 6 11 15 Other Indian studies from Chennai (Cancer Institute, Stage IV—66%), Delhi (AIIMS, Stage IV—57%), and Chandigarh (PGIMER, stage IV—53%) reported lower proportions of stage IV lung cancers. 6 7 16 As detailed above, we noted a significant delay in presentation, diagnostics, and the start of therapy—all these could have contributed to the upstaging of these patients. The median duration from presentation to start of treatment was around 3 months when we excluded patients who were referred from outside after complete workup. Similar issues were noted in a previous Indian study, 17 which suggested the initiation of empirical antitubercular therapy as a common cause of significant delay in our setting. Surprisingly, a Turkish study 18 has shown that patients presenting with shorter symptoms to treatment duration had a worse prognosis. Similarly, in our study, the survival of patients receiving palliative chemotherapy was higher in patients started on chemotherapy after a delay of > 40 days from diagnosis. This could reflect the biology of the disease and the fact that sick patients with advanced disease could have been fast-tracked for diagnosis or treatment. At the same time, many of the more aggressive cancers could have resulted in poor performance status and could have never been referred to our department. Similar findings have been reported from studies in diffuse large B-cell lymphomas. 19

We found no association between delay in start of therapy and other baseline characters like performance status, age, or presence of comorbid conditions. Other studies have indicated that distance from the center may lead to delay in diagnosis but we did find that. 20 There may be complex social, economic, and psychological factors underpinning this issues of delay, which can be answered only by a focused prospective study. Almost one-third of patients seek alternative medicines, and there are issues like dissatisfaction or disbelief in the medical system, coupled with a poor understanding of the disease and its outcomes which may also lead to treatment delays. 21 22

In patients treated with palliative chemotherapy, the median PFS of 5.8 months was similar to other studies from South India. 6 15 However, the OS of 9 months in this particular subgroup of stage IV disease was marginally higher compared to 6.5 months reported by Murali et al and 7 months reported by Rajappa et al. 6 15 One of the factors could be the increased use of maintenance therapy in the present cohort, compared to no use of maintenance chemotherapy in the study by Rajappa et al. Also, majority (96%) of patients in this cohort received intravenous (IV) chemotherapy while Murali et al included all patients with stage IV and only 41% among them received IV chemotherapy. This might be the reason for the better OS in our cohort. Cross-center comparison of survival data has to be done cautiously because of the variations in patient presentation, treatment selection, use of various protocols, and methods of assessment of outcomes.

The EGFR positivity rate of 45% was comparable with the other study from south India, and the most common mutations detected were exon19 deletion, followed by exon21 mutation, which was similar to the proportion reported by Noronha et al. 6 23 The PFS and OS of 41 patients started on EGFR TKIs were 8.5 months and 18.4 months, respectively, which is similar to published literature from India. 24 Higher rates of ALK mutations have been noted in certain previous Indian studies (10% compared to about 5% in Western literature) and were noted in our study also. 25

Despite the drawbacks of a retrospective analysis, our study reflects the challenges faced when treating patients with lung cancer in resource-constrained settings. The advent of targeted therapy and immunotherapy has produced massive gains in survival. However, as shown by our analysis, the penetration of these advances are limited. Despite chemotherapy and gefitinib being made available free-of-cost, there was a high proportion of treatment abandonment. The reasons for these need to be sought in prospective studies. Appropriate measures must be taken to ensure proper delivery and adherence to available therapies. Only then will the impact of newer treatments (as and when they become available) will be realized.

Funding Statement

Funding The study was supported by Jawaharlal Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education & Research (JIPMER). No grant number is applicable. There were no external sources of funding for this project.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest None of the authors have any relevant conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval This study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee (approval number: 2019/508, dated December 18, 2019).

References

- 1.Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel R L, Torre L A, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68(06):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malik P S, Raina V. Lung cancer: prevalent trends & emerging concepts. Indian J Med Res. 2015;141(01):5–7. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.154479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yuan M, Huang L-L, Chen J-H, Wu J, Xu Q. The emerging treatment landscape of targeted therapy in non-small-cell lung cancer. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2019;4(01):61. doi: 10.1038/s41392-019-0099-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behera D. SC17.03 Lung cancer in India: challenges and perspectives. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12(01):S114–S115. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parikh P M, Ranade A A, Govind B. Lung cancer in India: current status and promising strategies. South Asian J Cancer. 2016;5(03):93–95. doi: 10.4103/2278-330X.187563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murali A N, Radhakrishnan V, Ganesan T S. Outcomes in lung cancer: 9-year experience from a tertiary cancer center in India. J Glob Oncol. 2017;3(05):459–468. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.006676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Malik P S, Sharma M C, Mohanti B K. Clinico-pathological profile of lung cancer at AIIMS: a changing paradigm in India. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(01):489–494. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.1.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blanchon F, Grivaux M, Asselain B. 4-year mortality in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer: development and validation of a prognostic index. Lancet Oncol. 2006;7(10):829–836. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70868-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cetin K, Ettinger D S, Hei Y-J, O’Malley C D. Survival by histologic subtype in stage IV nonsmall cell lung cancer based on data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results Program. Clin Epidemiol. 2011;3:139–148. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S17191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Khan N A, Afroz F, Lone M M, Teli M A, Muzaffar M, Jan N. Profile of lung cancer in Kashmir, India: a five-year study. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci. 2006;48(03):187–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doval D C, Sinha R, Batra U, Choudhury K D, Azam S, Mehta A. Clinical profile of nonsmall cell lung carcinoma patients treated in a single unit at a tertiary cancer care center. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(01):193–196. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.219591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohan A, Latifi A N, Guleria R. Increasing incidence of adenocarcinoma lung in India: Following the global trend? Indian J Cancer. 2016;53(01):92–95. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.180819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thun M J, Henley S J, Burns D, Jemal A, Shanks T G, Calle E E. Lung cancer death rates in lifelong nonsmokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(10):691–699. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wakelee H A, Chang E T, Gomez S L. Lung cancer incidence in never smokers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(05):472–478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajappa S, Gundeti S, Talluri M R, Digumarti R. Chemotherapy for advanced lung cancer: a 5-year experience. Indian J Cancer. 2008;45(01):20–26. doi: 10.4103/0019-509x.40642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaur H, Sehgal I S, Bal A. Evolving epidemiology of lung cancer in India: Reducing non-small cell lung cancer-not otherwise specified and quantifying tobacco smoke exposure are the key. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(01):285–290. doi: 10.4103/ijc.IJC_597_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chandra S, Mohan A, Guleria R, Singh V, Yadav P. Delays during the diagnostic evaluation and treatment of lung cancer. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(03):453–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Annakkaya A N, Arbak P, Balbay O, Bilgin C, Erbas M, Bulut I. Effect of symptom-to-treatment interval on prognosis in lung cancer. Tumori. 2007;93(01):61–67. doi: 10.1177/030089160709300111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maurer M J, Ghesquières H, Link B K. Diagnosis-to-treatment interval is an important clinical factor in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and has implication for bias in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36(16):1603–1610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ambroggi M, Biasini C, Del G iovane, C, Fornari F, Cavanna L. Distance as a barrier to cancer diagnosis and treatment: review of the literature. Oncologist. 2015;20(12):1378–1385. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broom A, Nayar K, Tovey P. Indian cancer patients’ use of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicine (TCAM) and delays in presentation to hospital. Oman Med J. 2009;24(02):99–102. doi: 10.5001/omj.2009.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elangovan V, Rajaraman S, Basumalik B, Pandian D. Awareness and perception about cancer among the public in Chennai, India. J Glob Oncol. 2016;3(05):469–479. doi: 10.1200/JGO.2016.006502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Noronha V, Patil V M, Joshi A. Epidermal growth factor receptor positive lung cancer: The nontrial scenario. Indian J Cancer. 2017;54(01):132–135. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.219583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Noronha V, Prabhash K, Thavamani A. EGFR mutations in Indian lung cancer patients: clinical correlation and outcome to EGFR targeted therapy. PLoS One. 2013;8(04):e61561–e61561. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Murthy S, Rajappa S, Gundimeda S, Mallavarapu K, Ayyagari S, Yalavarthi P. Anaplastic lymphoma kinase status in lung cancers: an immunohistochemistry and fluorescence in situ hybridization study from a tertiary cancer center in India. Indian Journal of Cancer. 2017;54(01):231–235. doi: 10.4103/0019-509X.219533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]