Summary

Aberrant protein citrullination is associated with many pathologies, however, the specific effects of this modification remain unknown. We have previously demonstrated that serine protease inhibitors (SERPINs) are highly citrullinated in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) patients. These citrullinated SERPINs include antithrombin, antiplasmin, and t-PAI, which regulate the coagulation and fibrinolysis cascades. Notably, citrullination eliminates their inhibitory activity. Herein, we demonstrate that citrullination of antithrombin and t-PAI impairs their binding to their cognate proteases. By contrast, citrullination converts antiplasmin into a substrate. We recapitulate the effects of SERPIN citrullination using in vitro plasma clotting and fibrinolysis assays. Moreover, we show that citrullinated antithrombin and antiplasmin are increased and decreased in a deep vein thrombosis (DVT) model, accounting for how SERPIN citrullination shifts the equilibrium towards thrombus formation. These data provide a direct link between increased citrullination and the risk of thrombosis in autoimmunity and indicate that aberrant SERPIN citrullination promotes pathological thrombus formation.

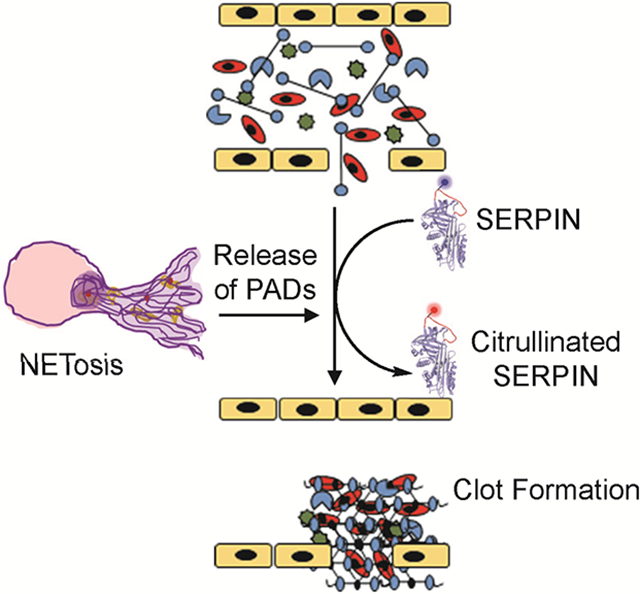

Graphical Abstract

eTOC blurb

Tilvawala et al. demonstrate that citrullination alters the activity of SERPINs involved in the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways and shifts the equilibrium towards thrombus formation. These data reconcile two observations; that both protein citrullination and thrombosis are elevated in autoimmunity and that aberrant SERPIN citrullination contributes to pathological thrombus formation.

Introduction

The Protein Arginine Deiminases (PADs) catalyze the post-translational modification (PTM) of an arginine residue to form a citrulline-containing protein (Fuhrmann et al., 2015; Tilvawala and Thompson, 2019). Increased citrullination is associated with multiple inflammatory diseases (Jones et al., 2009; Vossenaar et al., 2003). While the role of citrullination in these disease pathologies is mostly unknown, it is important to recognize that pan-PAD inhibitors, developed by our laboratory, show remarkable efficacy in animal models of Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) (Willis et al., 2011), lupus (Knight et al., 2015; Knight et al., 2013), multiple sclerosis (Moscarello et al., 2007), ulcerative colitis (Chumanevich et al., 2011), and cancer (Nemmara et al., 2018a; Nemmara and Thompson, 2018). Protein citrullination is mostly studied in context of RA, where more than 75% of patients produce anti-citrullinated protein antibodies (ACPA). These antibodies are generated in response to citrullinated epitopes present on various proteins including vimentin, enolase, fibrin and fillagrin (van Beers et al., 2010; Vossenaar et al., 2004a). Notably, ACPA are detectable 4–5 years before clinical onset and are key drivers of RA pathogenesis (van der Helm-van Mil et al., 2006; van Venrooij et al., 2006).

There are five human PAD isozymes, i.e. PADs 1–4 and PAD6 (Fuhrmann et al., 2015; Tilvawala and Thompson, 2019), however, only PADs 1–4 possess activity (Raijmakers et al., 2007). Enzyme activity requires calcium (Fujisaki and Sugawara, 1981) and these enzymes are activated during apoptosis and epidermal differentiation where cellular calcium concentrations are significantly higher (>100 μM) than normal physiological levels (Witalison et al., 2015). In addition to calcium, we recently showed that thioredoxin (hTRX), an oxidoreductase that maintains the cellular reducing environment, can regulate PAD activity (Nagar et al., 2019).

Citrullination regulates gene transcription via the citrullination of transcription factors (e.g., E2F and NFκB) (Chang et al., 2016; Ghari et al., 2016) as well as histones H1 (Christophorou et al., 2014), H2A (Hagiwara et al., 2005), H3 (Zhang et al., 2012), and H4 (Wang et al., 2004). Histone citrullination also contributes to a pro-inflammatory form of programmed cell death called Neutrophil Extracellular Trap (NET) formation or NETosis (Knight et al., 2015; Rohrbach et al., 2012). In this process, neutrophils, a key cellular component of the innate immune system, decondense their chromatin to form web-like structures that are extended from cells. PAD activity is key to this process and chromatin decondensation is associated with histone hypercitrullination (Knight et al., 2015; Li et al., 2010). Recent studies have shown that NET formation plays an important role in arterial and venous thrombus formation (Kambas et al., 2012; Martinod and Wagner, 2014). For example, NET-like structures are present in Lewis lung carcinoma (LLC) hemorrhagic tumors and NETosis contributes to a higher risk of cancer-associated thrombosis (Demers and Wagner, 2013; Martinod et al., 2013). Moreover, a recent study, involving a cohort of 23.7 million people, showed that RA patients have a 3.4-fold higher risk of developing a blood clot relative to healthy controls (Chung et al., 2014). In total, these studies suggest that NETosis and PAD-mediated citrullination plays a role in abnormal thrombotic events in autoimmunity and cancer.

Given the well-established links between increased protein citrullination and RA, we recently used a chemoproteomic approach to identify the citrullinated proteins associated with RA. Specifically, biotin-phenylglyoxal (biotin-PG), a citrulline-specific chemical probe, was used to identify the citrullinated proteins present in RA patient samples. Along with known PAD substrates, we identified more than 150 substrates. When we sub-divided these proteins based on protein functionality, both SERPINs (Serine Protease Inhibitors) and Serine Proteases were highly citrullinated in patient samples (Tilvawala et al., 2018). Notably, many of these proteins directly control blood flow by regulating blood coagulation (Sprengers and Kluft, 1987) and fibrinolysis (Carpenter and Mathew, 2008).

Coagulation and fibrinolysis, the biological processes that maintain proper blood flow, are the consequence of a complex cascade of enzymatic reactions. Blood coagulation is triggered by either the intrinsic or extrinsic pathways. Both the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways merge to a common pathway that activates Factor X which generates active thrombin (O’Donnell et al., 2019). The cleavage of fibrinogen by thrombin results in the formation of a stable multimeric, cross-linked complex. These cross-linked fibrillar aggregates together with platelets and red blood cells, provide structural integrity to the growing thrombus. Fragile clots are more susceptible to fibrinolysis and bleeding, whereas firm clots are more resistant, but may promote thrombosis (O’Donnell et al., 2019). Local thrombin concentration also impacts clot structure, as higher thrombin concentrations generate more stable clots. Thus, the concentrations of active thrombin are required to be tightly regulated. Thrombin is mainly regulated by proteolysis, which generates active proteases, and endogenous SERPINs, e.g. antithrombin, which inhibit thrombin (O’Donnell et al., 2019). Like coagulation, fibrinolysis is tightly controlled by cofactors, inhibitors, and receptors (Chapin and Hajjar, 2015). Plasmin, the primary protease regulating fibrinolysis, is activated by either tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or urokinase-type plasminogen activator (u-PA). The activity of circulating plasmin and plasminogen activators are neutralized by the SERPINs antiplasmin and tissue-type plasminogen activator inhibitor (t-PAI), respectively. Therefore, antithrombin, antiplasmin and t-PAI are key SERPINs that regulate the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathway and disrupting the delicate balance between coagulation and fibrinolysis pathway results in pathological conditions including, thrombosis or abnormal bleeding (Chapin and Hajjar, 2015).

Given the paramount importance of SERPINs in regulating hemostasis and fibrinolysis, we evaluated the effect of citrullination on SERPIN activity and showed that citrullination abolishes the ability of a SERPIN to inhibit its cognate protease (Figure 1A) (Tilvawala et al., 2018). Herein, we report the sites of citrullination in antithrombin, antiplasmin and t-PAI. Moreover, we demonstrate that citrullination prevents the interaction between antithrombin and t-PAI and their cognate proteases. By contrast, citrullination converts antiplasmin from an inhibitor into a substrate. We further evaluated the impact of SERPIN citrullination on blood clotting and fibrinolysis in vitro and in vivo and showed that citrullination promotes thrombus formation in a murine deep vein thrombosis (DVT) model.

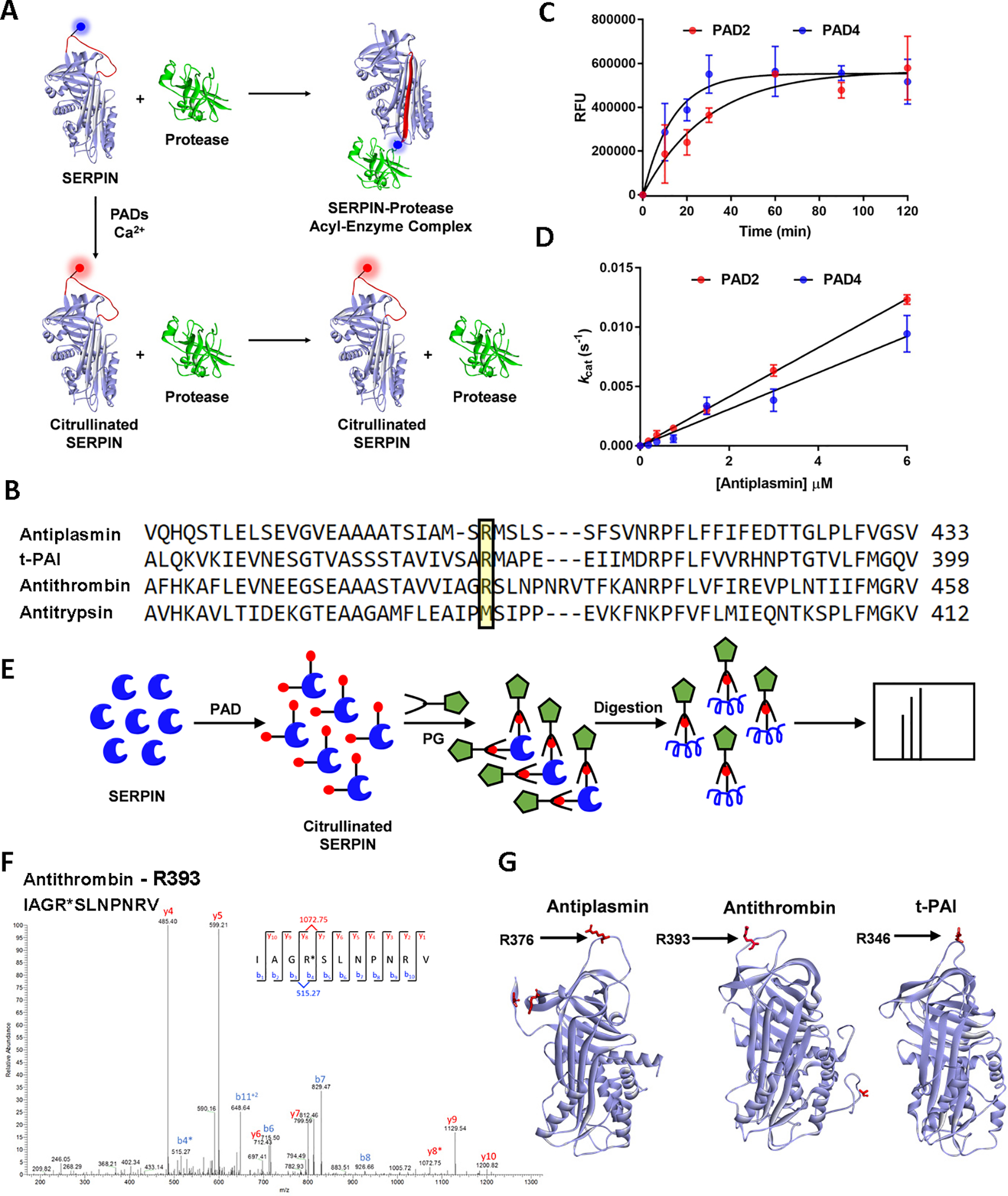

Figure 1. Citrullination inactivates SERPIN activity.

A. Schematic diagram showing the effect of citrullination on SERPIN activity. Citrullination of the P1-arginine in SERPINs abolishes their inhibitory activity against their cognate proteases. B. Sequence alignment of human antiplasmin, antithrombin, t-PAI and antitrypsin. C. Progress curves for the citrullination of antiplasmin by PAD2 and PAD4. D. Linear plot showing the activity of PAD2 and PAD4 against various antiplasmin concentrations. E. Identification of citrullination sites in SERPINs. Workflow showing the labeling of citrullinated SERPINs with phenylglyoxal and subsequent digestion with neutrophil elastase, trypsin, or GluC for the detection of citrullinated peptides by MS. F. Representative MS/MS spectrum that identified the phenylglyoxal labeled P1-arginine in antithrombin. G. Sites of citrullination represented on the structures of antiplasmin (PDB: 2R9Y), antithrombin (PDB: 1T1F), and t-PAI (PDB: 5BRR). See also Figure S1, Data S1, and Table S1.

Results

SERPIN Citrullination.

Mechanistically, SERPINs react with serine proteases through a reactive center loop (RCL). The RCL is an extended, exposed sequence above the body of the SERPIN scaffold. Upon cleavage of the peptide bond between the P1 and P1’ position, SERPINs undergo a dramatic conformational change that traps the protease in an inactive acyl-enzyme complex (Khan et al., 2011). In many SERPINs, the P1 residue is an arginine, which docks the RCL into the protease active site (Figure 1A). Our previous studies (Tilvawala et al., 2018) demonstrated that citrullination of antiplasmin, antithrombin and t-PAI by PAD1, PAD2, and PAD4 virtually abolished their ability to inhibit their cognate proteases plasmin, thrombin, and t-PA. Similar results were obtained for C1 inhibitor (Tilvawala et al., 2018). In general, PAD3-treated SERPINs demonstrated a smaller effect ((Tilvawala et al., 2018). Notably, antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI employ an arginine residue at the P1-position (Figure 1B). By contrast, antitrypsin lacks a P1-arginine and citrullination did not affect its ability to inhibit its cognate protease (Tilvawala et al., 2018). These data are consistent with the notion that SERPIN inactivation is due to the citrullination of the P1-arginine (Tilvawala et al., 2018).

To confirm this model, we first determined the steady-state kinetic parameters for the PAD-mediated citrullination of antithrombin and antiplasmin. We focused on PAD2 and PAD4 for these experiments because these isozymes are expressed in immune cells and have been detected in RA serum and synovial fluid (Damgaard et al., 2014; Vossenaar et al., 2004b). For these experiments, we generated progress curves of antiplasmin citrullination to identify the linear range of PAD activity (Figure 1C). The extent of citrullination was measured with Rhodamine-PG (Rh-PG), which chemoselectively labels citrullinated proteins. Next, we measured the initial rates of antiplasmin citrullination (Figure 1D). The fluorescence intensity of Rh-PG was converted to citrulline concentration using a standard curve of citrullinated histone H3. From these experiments, the kcat/Km values for antiplasmin citrullination were found to be 8500 and 6200 M−1s−1 for PAD2 and PAD4, respectively. Similar experiments were performed for antithrombin. The kcat/Km values for antithrombin were 5000 and 5200 M−1 s−1 for PAD2 and PAD4, respectively (Figure S1A, S1B). These values are comparable to other known physiological substrates, including histone H3 (kcat/Km = 4800 M−1 s−1) (Knuckley et al., 2010). These results indicate that antiplasmin and antithrombin are bona fide substrates of both PAD2 and PAD4.

Identification of citrullination sites in SERPINs.

Having established the kinetics of SERPIN citrullination, we next identified the sites of citrullination in antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI. For these experiments, we used an approach that was recently established by our laboratory (Nemmara et al., 2018b). Briefly, PAD-treated SERPINs were labeled with phenylglyoxal (PG) under acidic conditions (Figure 1E). PG selectively modifies citrullinated residues under acidic conditions, leading to a mass increase of 117 Da which can be unambiguously interpreted as a citrullination event. The PG-modified proteins were then digested with different proteases, including trypsin, Glu-C, and neutrophil elastase (NE) to maximize sequence coverage. The digests were then subjected to proteomic analysis. Figure 1F depicts a representative high-resolution MS/MS spectrum for the citrullination of the P1-arginine in antithrombin. Ordóñez et al also showed that PAD4 citrullinates the P1-arginine in antithrombin, along with other solvent-exposed arginines, in a time-dependent manner (Ordonez et al., 2009). Additional citrullination sites were found in all three SERPINs. These citrullination sites include the P1-arginines in antiplasmin and t-PAI, although we note that the spectra for t-PAI are not definitive. These data are summarized in Figure 1G and Table S1. Spectra for each peptide are provided in Data S1. The corresponding arginine residues in control samples did not show mass changes consistent with citrullination at these positions.

Mechanisms of SERPIN inactivation.

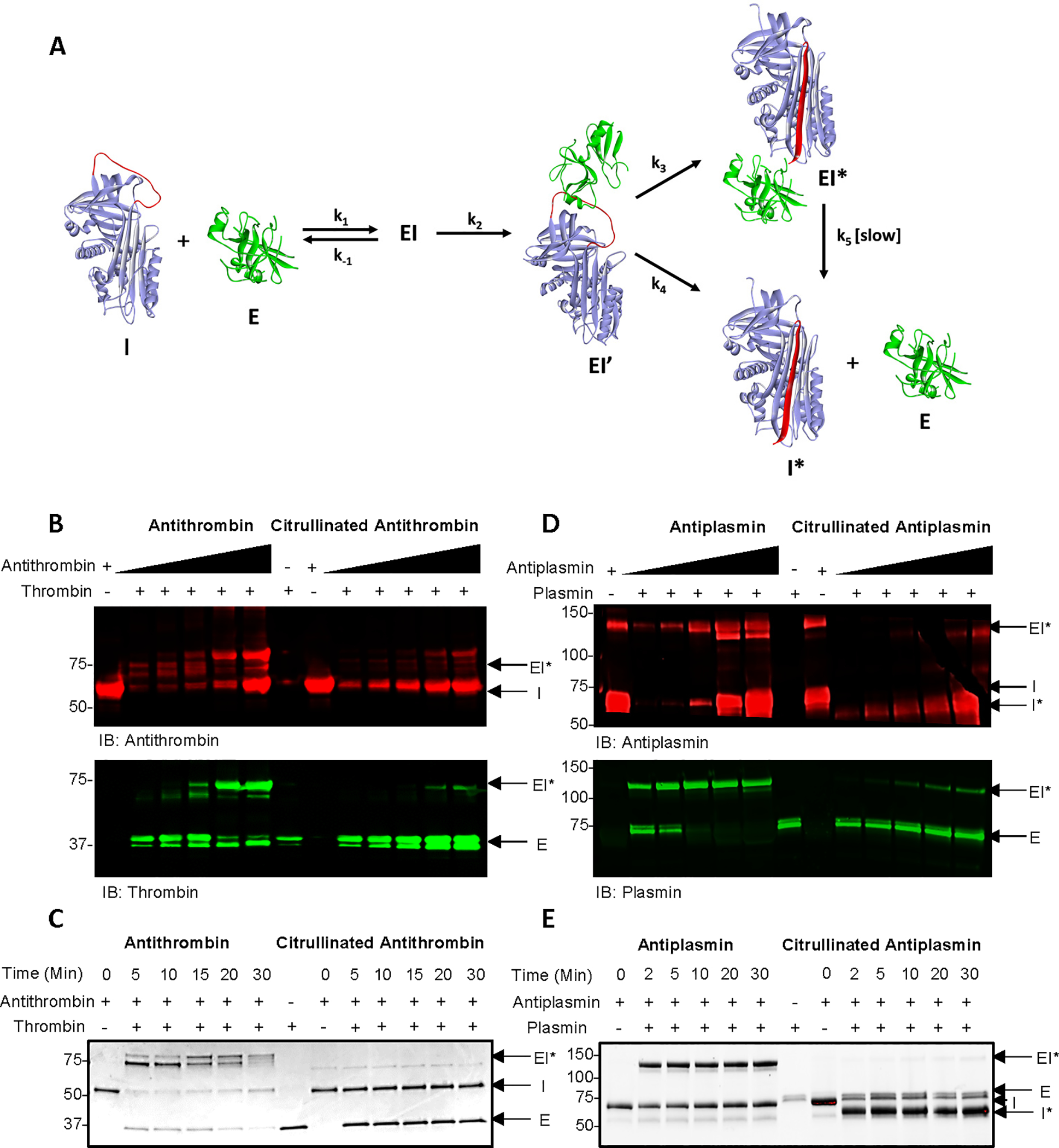

Structurally, SERPINs possess a common core domain consisting of three β-sheets, 8−9 α-helices, and a Reactive Center Loop (RCL) which is situated above the body of the SERPIN. Initially, a protease (E) binds the RCL in a SERPIN (I) to form a noncovalent Michaelis-like complex (EI) by interacting with residues flanking the scissile bond (P1-P1’). Subsequently, the active site serine acts as a nucleophile and attacks the SERPIN at the P1-P1’ position, leading to the loss of the C-terminal fragment and the formation of an acyl-enzyme intermediate (EI’) that consists of a covalent ester linkage between the nucleophilic serine of the protease and the backbone carbonyl of the P1 residue. This cleavage event is followed by the rapid insertion of the RCL into the body of the SERPIN to generate a thermodynamically stable β-sheet (Dementiev et al., 2006). In this conformation, the active site of the protease is distorted; thereby preventing the hydrolysis of the newly formed ester bond and thus trapping the protease in an irreversible acyl-enzyme complex (EI*) (Figure 2A). If the rate of RCL insertion is impaired, the acyl-enzyme intermediate (EI’) can hydrolyze, resulting in an inactive SERPIN (I*) and active protease (E) (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Mechanisms of SERPIN inactivation.

A. Schematic diagram showing the SERPIN-protease reaction (Adapted from (Ashton-Rickardt, 2013)). B. Detection of thrombin-antithrombin complexes in the presence of citrullinated and control antithrombin by western blot analysis. C. SDS-PAGE analysis of time-dependent antithrombin-thrombin complex formation in the presence of citrullinated and control antithrombin using stain-free gels. D. Detection of plasmin-antiplasmin complexes in the presence of citrullinated and control antiplasmin by western blot analysis. E. SDS-PAGE analysis of time-dependent antiplasmin-plasmin complex formation in the presence of citrullinated and control antithrombin. Cleaved antiplasmin is visible at ~55 kDa using stain-free gels. See also Figure S2.

Since antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI inactivate their cognate proteases by forming a covalent acyl-enzyme complex, protease inactivation can be visualized by a mass shift after SDS-PAGE. To evaluate the impact of citrullination on the SERPIN-protease interaction,SERPINs were first citrullinated in vitro and then incubated with their cognate proteases. Uncitrullinated samples were used as controls. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and subjected to western blotting. The results show that citrullinated antithrombin does not form a higher molecular weight complex with either thrombin or Factor Xa (FXa), a second protease inhibited by antithrombin (Figure 2B and S2A). By contrast, the control samples do form these complexes. Note that the observed doublet is thought to represent the acyl-enzyme intermediate in either the open (EI’) or closed (EI*) conformation (Zhou et al., 2001). Similar results were obtained with t-PAI and t-PA (Figure S2B). These data are consistent with the lack of inhibitory activity observed after citrullination and suggest that this effect is due to the loss of recognition of citrullinated antithrombin and t-PAI by their cognate proteases. Acyl-enzyme complex formation was also followed as a function of time with aliquots taken over 30 min. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE. Notably, citrullinated antithrombin does not form an acyl-enzyme complex with thrombin or FXa even after 30 min of incubation (Figure 2C and S2C). By contrast, complex formation was essentially complete within 2 min for the controls. Similar results were obtained with t-PAI and t-PA (Figure S2D). These results are consistent with our previous data and indicate that upon citrullination, antithrombin and t-PAI no longer react with thrombin and t-PA, respectively, as depicted in Figure S2E. Since complex formation requires hydrolysis of the peptide C-terminal to the P1 arginine, our data indicate that citrullination either prevents the initial formation of the Michaelis complex or subsequent catalytic steps leading to the formation of the initial tetrahedral intermediate. Future studies are required to differentiate between these possibilities.

When we performed similar experiments with antiplasmin, the results were quite intriguing. First, western blot analysis of plasmin treated with citrullinated antiplasmin showed the appearance of a smaller protein band with an apparent molecular weight of 55 kDa (I*) (Figure 2D). This 55 kDa band was also visible by SDS-PAGE analysis using stain-free gels (Figure S2F). Given that the sizes of intact antiplasmin and the RCL are ~65 kDa and ~10 kDa, respectively, we hypothesized that the ~55 kDa band corresponds to the cleaved form of antiplasmin. Indeed, a previous study showed that this form appears at ~55 kDa (Sazonova et al., 2007). These results suggest that citrullination converts antiplasmin from an inhibitor into a substrate. This conclusion was confirmed by incubating citrullinated antiplasmin with plasmin and evaluating cleavage as a function of time. Notably, plasmin completely cleaved citrullinated antiplasmin within 5 min (Figure 2E). These results are in stark contrast to that of citrullinated antithrombin and t-PAI, which showed no such effect. In summary, these data indicate that while citrullinated antithrombin and t-PAI are not recognized by their cognate proteases, citrullinated antiplasmin is not only recognized but also cleaved by plasmin as depicted in Figure S2G.

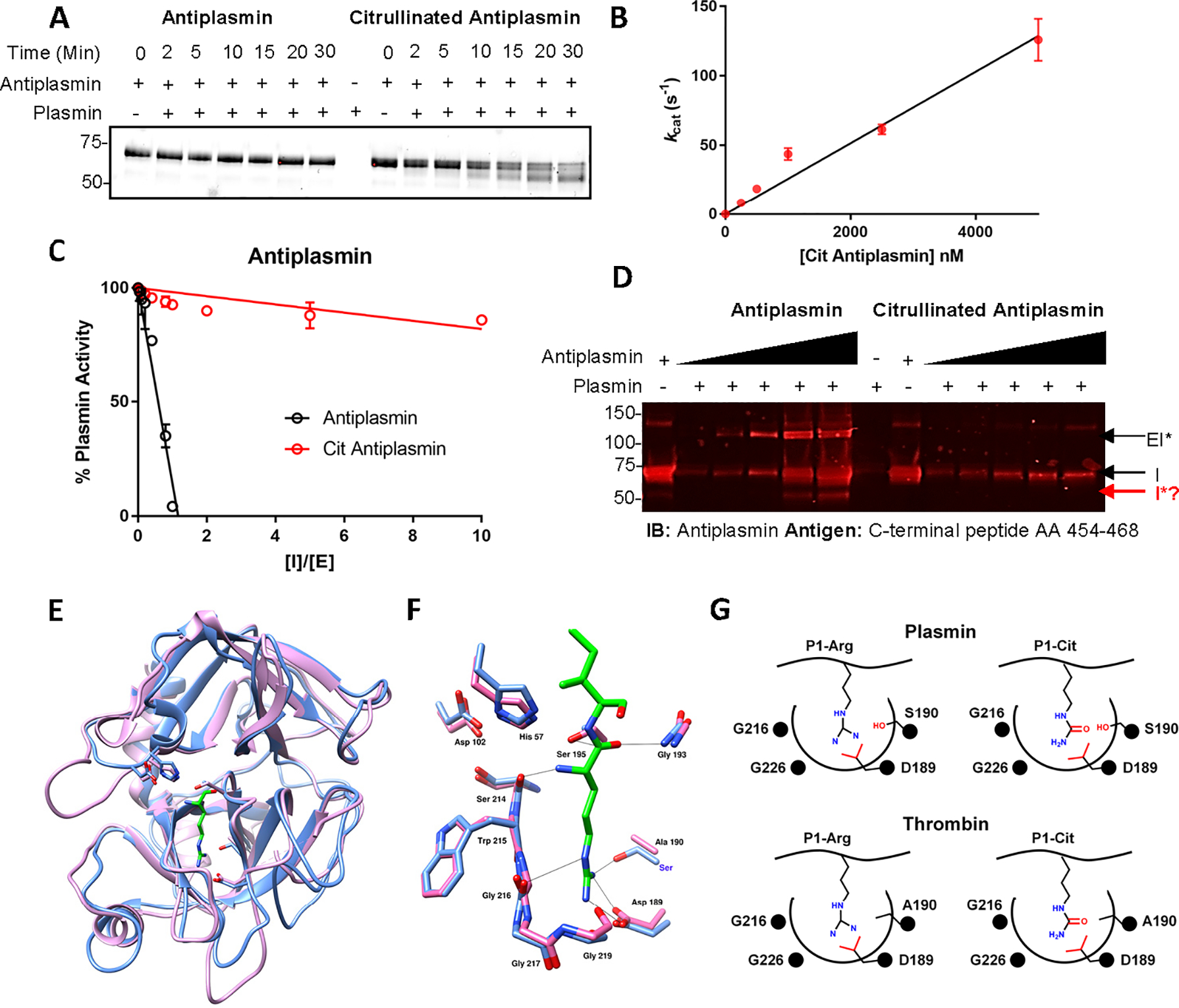

Citrullinated antiplasmin is a plasmin substrate.

Having demonstrated that citrullinated antiplasmin is a plasmin substrate, we next determined the steady-state kinetic parameters for this process. For these experiments, we first generated progress curves of citrullinated antiplasmin cleavage to identify the linear range of plasmin activity. Citrullinated and control antiplasmin were incubated with sub-nanomolar concentrations of plasmin over a 30 min period and aliquots taken at the indicated times. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE and the band intensity of cleaved antiplasmin was measured at ~55 kDa (Figure 3A). Note that the rate of antiplasmin cleavage is linear over 30 min (Figure S3A). Next, we measured the initial rates of citrullinated antiplasmin cleavage (Figure 3B). The measured band intensities at 55 kDa were converted to cleaved antiplasmin concentrations using a standard curve of cleaved antiplasmin. From these experiments, the kcat/Km for the cleavage of citrullinated antiplasmin was estimated to be 2.5 × 107 M−1 s−1. This level of activity is remarkable as it approaches the diffusion limit. By contrast, plasmin does not cleave control, uncitrullinated, antiplasmin over this time or concentration range (Figure 3A, S3A). In total, these experiments confirm that citrullination converts antiplasmin from an inhibitor to a plasmin substrate.

Figure 3. Antiplasmin Cleavage.

A. SDS-PAGE analysis of the time-dependent cleavage of citrullinated antiplasmin by plasmin. B. Linear plot showing the activity of plasmin against citrullinated antiplasmin. C. Partition ratio analysis of citrullinated and control antiplasmin. D. Detection of cleaved antiplasmin by western blot analysis. E. Structural superimposition of Pl-arginine in plasmin (PDB: 3UIR) and thrombin (PDB:14XF). Plasmin and thrombin are shown in blue and pink, respectively. The P1 arginine is shown in green. F. Structural superimposition of the hydrogen bonding network in the active site of plasmin (blue) and thrombin (pink) with P1- arginine (green). G. Schematic of S1 pockets in plasmin and thrombin and their interactions with P1-arginine or P1-citrulline. See also Figure S3.

To gain further insight into this process, we next determined whether plasmin can cleave peptide-based mimics of the RCL that contain either the native arginine or a citrulline at the P1-position (peptides 1 and 2 in Figure S3B). For these experiments, the peptides were incubated with plasmin for various lengths of time and formation of the C-terminal peptide (fragment B) was monitored using LC-MS. The initial rates were calculated from the area under the curve and fit to a pseudo-first order rate equation. Our results indicate that plasmin cleaves both peptide 1 and peptide 2 with rates that are on the order of (1.0 ± 0.3) *10−3 s−1 and (0.3 ± 0.01) *10−3 s−1, respectively (Figure S3C–E). We also evaluated two 7-amido 4-methylcoumarin (AMC) reporter peptides (Figure S3F) that contain an arginine (3) or citrulline (4) at the P1-position. For these experiments, the initial rates were determined at a fixed concentration of protease by monitoring the hydrolysis of the AMC reporter in real time. Consistent with the results described above, the citrulline-containing reporter (4) was preferentially cleaved by plasmin versus thrombin. When compared to the arginine containing peptide, kcat/KM is decreased by only 20-fold for plasmin but 200-fold for thrombin (Figure S3G and S3H). Note that it is not surprising that the kinetic values for these RCL mimetics are small because the extended structure of the RCL is critical for substrate recognition and plasmin shows only modest activity against peptide substrates (Hervio et al., 2000). Nevertheless, these data confirm that plasmin effectively recognizes and cleaves P1-citrulline containing substrates whereas thrombin is markedly less robust.

To gain further insights, we also measured the stoichiometry of inactivation, i.e., the molar ratio of antiplasmin required to completely inactivate plasmin (Tilvawala et al., 2015; Tilvawala and Pratt, 2013a). For these experiments, a fixed concentration of plasmin was incubated with different molar ratios of control antiplasmin followed by the rapid addition of plasmin substrate. Hydrolysis of the latter was monitored spectrophotometrically, and initial rates were fit to a linear equation (Figure 3C). The partition ratio was obtained from the intercept on x-axis and calculated to be close to 1. These data indicate that virtually every encounter leads to the formation of the plasmin-antiplasmin acyl-enzyme complex. By contrast, the partition ratio for citrullinated antiplasmin was ≥56, consistent with the notion that citrullination shifts antiplasmin from an inhibitor to a substrate confirming our gel-based findings.

Interestingly, several monoclonal antibodies can convert antiplasmin from an inhibitor to a substrate by inducing a conformational change (Sazonova et al., 2007). To understand whether citrullination induces a similar conformational change in antiplasmin, we used circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy. For these studies, we measured the far UV CD-spectra of citrullinated and control antiplasmin. The CD spectra of citrullinated and control antiplasmin did not show significant differences (Figure S3I), eliminating the possibility that the shift from inhibitor to substrate is associated with a gross conformational change in antiplasmin structure. Similar experiments were performed with antithrombin. In agreement with the antiplasmin data, citrullinated antithrombin does not show any large conformational changes (Figure S3J). These data are also consistent with our previous data showing that mutation of the P1-arginine to a lysine abolishes the effect of citrullination.

Based on our data, we hypothesized that plasmin cleaves citrullinated antiplasmin within the RCL, close to the C-terminus of the protein. To confirm that cleavage occurs at this site, we used an antibody that recognizes a peptide from the cleaved portion of the RCL (Figure S3K). Since cleaved antiplasmin (~55 kDa) lacks the RCL peptide that is recognized by this antibody, we hypothesized that it would not enable visualization of the ~55kDa fragment in western blots. Indeed, the cleaved antiplasmin band (~55 kDa) was not visible after treatment of citrullinated antiplasmin with plasmin (Figure 3D). By contrast, this fragment is readily detectable with the antibody targeting the N-terminus of antiplasmin (Figure 2D). Using the former antibody, we were able to detect the ~10 kDa peptide cleaved from RCL by antiplasmin (Figure S3L). In total, these data confirm that plasmin cleaves citrullinated antiplasmin after the P1-position in the RCL. Note that the ~15 kDa band is an impurity present in our antiplasmin preparation and that repeated attempts to unambiguously detect this cleavage site by mass spectrometry were unsuccessful.

Structural basis for differential reactivity.

Our studies confirm that citrullinated antithrombin is not recognized by thrombin and that the citrullinated antiplasmin is a plasmin substrate. The differential reactivity of plasmin and thrombin towards these citrullinated SERPINs can be explained based on their structures. Plasmin and thrombin are both trypsin-like serine proteases. Thus, these two enzymes have high sequence identity, and their tertiary structures are very similar (Figure 3E). In these proteases, the catalytic triad is formed by His57, Asp102, and Ser195 (plasmin numbering). Apart from the catalytic triad, the oxyanion hole stabilizes the tetrahedral intermediate and the S1 binding pocket plays a key role in defining the substrate specificity of all trypsin-like serine proteases. The S1 binding pocket is formed by residues 189–195, 214–220, and 225–228 (Figure 3E, 3F). In this pocket, a salt bridge is formed between Asp189 and the side chain of the P1-arginine. In general, a P1-citrulline is not well accommodated in the active site because the neutral side chain of citrulline cannot form this critical salt bridge. This observation explains why a P1-citrullinated antithrombin is not recognized by thrombin.

By contrast, recent studies with another trypsin-like protease, neutrophil serine protease 4 (NSP4), showed that in absence of Asp189, the side chain of a P1-arginine is accommodated in the S1 binding pocket via the formation of hydrogen bonds between the guanidinium moiety and the backbone carbonyl of Gly216 and side chain of Ser192 (Lin et al., 2014). Notably, NSP4 hydrolyzes substrates with either an arginine or a citrulline at the P1-position and the urea group is thought to form similar interactions with Gly216 and Ser192. Like NSP4, plasmin also contains a serine at the corresponding position (i.e., Ser192). Thus, plasmin likely accommodates citrullinated antiplasmin via interactions between backbone carbonyl of Gly216 and with the side chain of Ser192 in the S1 binding pocket (Figure 3F, 3G). By contrast in thrombin, the residue corresponding to Ser192 is an alanine, further explaining why thrombin poorly accommodates a P1-citrulline.

RCL cleavage and insertion into the body of the SERPIN is crucial for effective inhibition as the ensuing conformational changes distort the active site of the protease and thereby prevent the efficient hydrolysis of the acyl-enzyme intermediate. As such, the protease is normally trapped in an irreversible SERPIN-protease complex. By contrast, citrullinated antiplasmin binds plasmin via the alternative hydrogen bonding pattern described above and the lack of salt bridge between the P1-guanidinium group and Asp189 in the S1 binding pocket likely prevents the large conformational changes that distort the active site and lead to the insertion of RCL into the body of the SERPIN. Consequently, the transient acyl-enzyme intermediate is rapidly hydrolyzed to generate the observed 55 kDa fragment of antiplasmin and the regeneration of active plasmin as shown in Figure S2G.

Blood Clotting Assays.

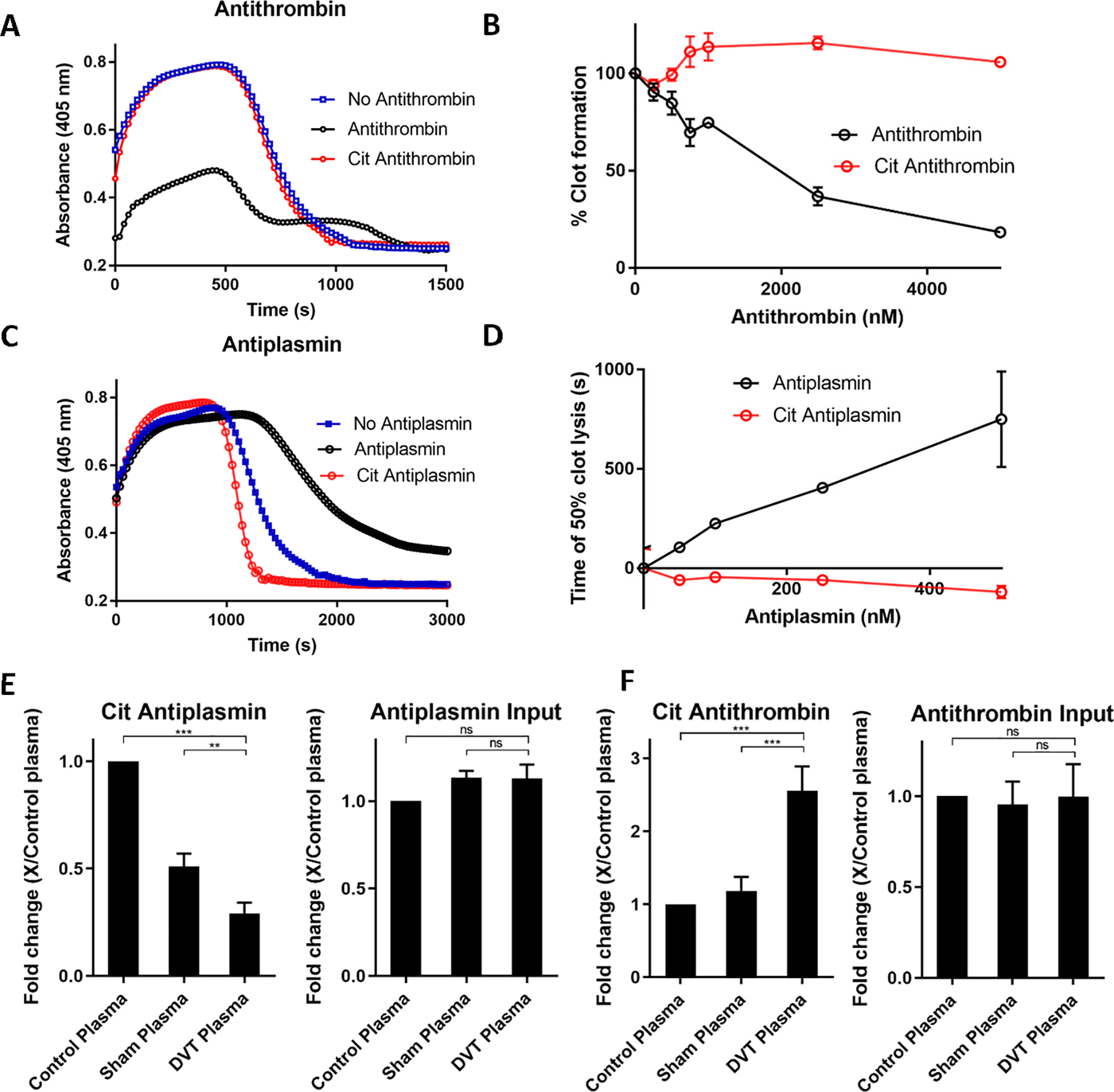

Antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI regulate hemostasis by controlling the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways. Antithrombin inhibits thrombin-assisted coagulation while antiplasmin and t-PAI inhibit plasmin and t-PA-assisted fibrinolysis (Figure S4A). Therefore, to understand the impact of citrullination on these pathways, we used combined clotting and fibrinolysis assays, focusing first on antithrombin. Initially, different concentrations of citrullinated and control antithrombin were incubated with a fixed concentration of thrombin before initiating the clotting assays. Reaction mixtures were then added to a 96-well plate containing human pooled plasma followed by rapid addition of buffer containing u-PA. Clot formation and lysis were measured spectrophotometrically at 405 nm. Thrombin promotes rapid clot formation, whereas u-PA converts plasminogen into plasmin which is responsible for fibrinolysis. We hypothesized that citrullinated antithrombin would not inhibit thrombin, leaving higher concentrations of active thrombin in the reaction mixture, resulting in an increase in clot formation. By contrast, control antithrombin will inhibit thrombin, resulting in lower clot formation. Our data revealed that citrullinated antithrombin does not inhibit thrombin-catalyzed clot formation, resulting in higher clot formation (Figure 4A). When we measured the effect over a range of concentrations, citrullinated antithrombin showed slightly more than 100% clot formation, by contrast, clot formation was decreased by up to 90% when samples were treated with control antithrombin (Figure 4B). The small increase in clot formation in the citrullinated antithrombin sample may reflect the citrullination of native antithrombin by residual PAD activity in the reaction mixture used to generate citrullinated antithrombin.

Figure 4. Ex vivo and in vivo blood clotting and fibrinolysis assays.

A. Plasma clotting assay in the presence of citrullinated and control antithrombin (5 μM). B. Concentration dependence of citrullinated antithrombin on blood clot formation. C. Effect of citrullinated and control antiplasmin (500 nM) on fibrinolysis. D. Concentration dependence of citrullinated antiplasmin on blood clot lysis. E. Quantification of citrullinated, input and cleaved antiplasmin from control, sham and DVT plasma. F. Quantification of citrullinated and cleaved antithrombin from control, sham, and DVT plasma. Experiments were carried out in triplicate and p-values calculated. See also Figure S4.

Next, we measured the effect of citrullinated antiplasmin and t-PAI on fibrinolysis. For these experiments, citrullinated and control SERPINs were directly added to human pooled plasma followed by the rapid addition of buffer containing u-PA. Here, we hypothesized that citrullinated antiplasmin would not inhibit plasmin, leaving higher concentrations of active plasmin in the reaction mixture, resulting in faster clot lysis. By contrast, control antiplasmin will inhibit plasmin, leaving lower concentrations of active plasmin in the reaction mixture, resulting in slower clot lysis. Our data show that the clot lysis time of citrullinated antiplasmin is reduced (Figure 4C). When we measured the effect over a range of concentrations, citrullinated antiplasmin decreased clot lysis time, whereas control, uncitrullinated, antiplasmin had the opposite effect and increased clot lysis time by ~12 min (Figure 4D). The slightly negative values observed for citrullinated antiplasmin reflect the fact that the data are normalized to the no antiplasmin control. The small decrease in time to 50% clot lysis likely reflects the citrullination of native antiplasmin by residual PAD activity present in the reaction mixture used to generated citrullinated antiplasmin.

We also hypothesized that citrullinated t-PAI would not inhibit t-PA and u-PA, leaving higher concentrations of active proteases in the reaction mixture, resulting in increased clot lysis. By contrast, control t-PAI will inhibit t-PA and u-PA by forming the acyl-enzyme complexes, leaving lower concentrations of active proteases in the reaction mixture, resulting in decreased clot lysis. Indeed, citrullinated t-PAI promotes 100% clot lysis (Figure S4B). When we measured the effect of citrullinated t-PAI over a range of concentrations, citrullinated t-PAI retained almost 100% clot lysis compared to control t-PAI, which showed 0% clot lysis (Figure S4C). In total, these data confirm that citrullination abolishes the inhibitory activity of SERPINs in vitro as well as ex vivo and further suggest that SERPIN citrullination is a physiologically relevant event.

Detection of Citrullinated SERPINs in DVT Plasma.

Given these findings, we next hypothesized that SERPIN citrullination would perturb natural hemostasis, leading to abnormal thrombotic events. Therefore, we used the murine deep vein thrombosis (DVT) model to understand the role of SERPIN citrullination in thrombotic events. Thrombi were generated in vivo by subjecting mice to inferior vena cava (IVC) stenosis by partial ligation of the IVC to ~10% of its original diameter. The spacer was then removed, and the mouse sutured and allowed to recover. For sham surgeries, the same procedure was performed, except that the IVC ligation was removed immediately after the temporary occlusion was caused and the mice were visually inspected to confirm that there was no thrombus formation. After 24 h, blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus and after appropriate treatment, the plasma was subjected to biotin-PG labeling to evaluate total levels of citrullinated proteins. Briefly, control, sham and thrombotic plasma were labeled with biotin-PG under acidic conditions. Proteins were then separated on SDS-PAGE and subjected to western blot analysis. The input levels of specific proteins were probed using an antibody against the protein of interest. In this analysis, the red band represents the input level of the specific protein of interest while the green band shows the level of citrullination of that same protein (Figure S4D). Based on this analysis, citrullinated antiplasmin levels are lower whereas the concentration of citrullinated antithrombin is increased in DVT plasma compared to control and sham plasma (Figure 4E, 4F), thereby providing optimal conditions to promote thrombus formation. We further quantified the input levels of antiplasmin and antithrombin. The input levels of antiplasmin and antithrombin are similar in control, sham and DVT plasma, confirming that the difference in citrullination of these proteins does not originate from unequal loading. Interestingly, the cleaved form of antiplasmin was also detected in DVT plasma samples (Figure 4E, S4E), indicating that thrombus formation in DVT plasma is associated with the loss of active antiplasmin due to citrullination. Unfortunately, we were unable to detect a significant level of cleaved citrullinated antiplasmin from DVT plasma. This may be due to its rapid degradation in vivo or because of the technical challenges in detecting a fluorescence signal from a lower concentration protein fragment (cleaved citrullinated antiplasmin) in the presence of a higher concentration protein band (i.e., uncleaved citrullinated antiplasmin). Overall, these experiments confirm that SERPIN citrullination contributes to thrombotic events.

Discussion

We previously defined the RA-associated citrullinome and identified more than 150 citrullinated proteins. Functional classification revealed that many of the proteins are SERPINs which regulate the blood clotting and fibrinolysis pathways. Moreover, we found that P1-arginine containing SERPINs such as antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI were citrullinated in our RA dataset and further demonstrated that citrullination of these SERPINs abolished their inhibitory activity against their cognate proteases (Tilvawala et al., 2018).

Herein, we confirmed that the P1-arginines of antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI are citrullinated. Using gel-based assays, we showed that citrullinated antithrombin and t-PAI fail to recognize their cognate proteases. By contrast, citrullination of antiplasmin converts it from an inhibitor into a plasmin substrate. We further demonstrated that plasmin cleaves antiplasmin after the P1-citrulline in the RCL. Interestingly, several monoclonal antibodies bind with antiplasmin and t-PAI and convert them from inhibitors to substrates of their cognate proteases by inducing a conformational change (Sazonova et al., 2007). Using CD spectroscopy, we found that citrullination does not induce a conformational change in antiplasmin and antithrombin, eliminating the possibility that this conversion from inhibitor to substrate is due to a gross conformational change. These data also show for the first time show that apart from antibodies, citrullination is another mechanism that inactivates P1-arginine containing SERPINs, thereby, regulating active protease concentration in the human body.

Using plasma clotting experiments, we confirmed that citrullinated antithrombin increases clot formation in plasma while citrullinated antiplasmin and t-PAI increases fibrinolysis. It is interesting to note that SERPIN citrullination would simulate the genetic deficiency of a SERPIN associated with abnormal coagulation or fibrinolysis. For example, antithrombin blocks abnormal blood clot formation by inhibiting active thrombin. Congenital antithrombin deficiency and reduced antithrombin activity causes abnormal blood clots (thrombi) that can block blood flow and damage organs. Antiplasmin or t-PAI deficiencies enhance active plasmin and t-PA concentrations, resulting in increased fibrinolysis leading to moderate to severe bleeding disorders (Carpenter and Mathew, 2008). In total, the effect of SERPIN citrullination on plasma clotting confirms that the citrullination of a SERPIN can alter hemostasis by impacting the coagulation and fibrinolysis pathways.

Finally, to understand the role of SERPIN citrullination in thrombosis, we used a DVT mouse model. NET formation was previously confirmed to occur in this model via the detection of large amounts of citrullinated histone H3 (Martinod et al., 2013). We recently demonstrated that citrullination inhibits the enzymatic activity of metalloprotease thrombospondin type-1 motif-13 (ADAMTS-13), promoting von Willebrand factor (VWF)-platelet string formation and accelerated thrombosis (Sorvillo et al., 2019). Interestingly, we show here that plasma from mice with DVT have lower levels of citrullinated antiplasmin and higher levels of citrullinated antithrombin, leading to lower active plasmin concentration and higher active thrombin concentrations, thereby, shifting the equilibrium towards clot formation versus clot lysis. Together, these data clearly propose a role for the PADs in pathological thrombosis. Future experiments are required to understand how antithrombin is preferentially citrullinated in this model.

DVT and venous thromboembolism are associated with high mortality and are responsible for ~300,000 deaths annually in United States (Raskob et al., 2010). Studies have previously shown that PAD4 mediated NETosis is prothrombotic and procoagulant and contributes to DVT clot formation (Martinod et al., 2013). NETosis is a multistep program in which neutrophils undergo cell death. During this process, which is generally associated with histone hypercitrullination, chromatin decondenses, the nuclear membrane disintegrates, and, finally, NETs are released into the extracellular environment. NET components include chromatin and neutrophil derived proteins, including myeloperoxidase and PAD4. In the vasculature, extracellular chromatin is quite deleterious, and promote thrombosis by providing a scaffold for the adhesion and aggregation of platelets and red blood cells. NETs have been observed in thrombi and plasma of baboons, humans, and mice subjected to DVT, confirming that NETs are a structural part of the thrombus (Brighton et al., 2013; Brill et al., 2012). The presence of NETs has also been observed in a human thrombus and the plasma of DVT patients. Many autoimmune diseases such as RA, lupus, and atherosclerosis show elevated levels of citrullinated proteins and increased risk of thrombosis (Chung et al., 2014; Zoller et al., 2012). Ordonez et al also detected elevated levels of citrullinated antithrombin in RA and adenocarcinoma (Ordonez et al., 2010). However, these authors did not observe a significant reduction in generalized anticoagulant activity in patients with the highest levels of citrullinated antithrombin and no correlation between citrullinated antithrombin and the thrombotic risk in patients with adenocarcinoma. Given that citrullinated SERPINs are detected in RA patient samples and RA patients have higher risk of thrombosis, our data are consistent with a model wherein NETosis and elevated citrullination of antithrombin in RA patients could lead to localized blood clot formation at sites of NETosis. These findings could be further extended to explain the role of citrullinated SERPINs in other autoimmune diseases which have an elevated risk of thrombosis.

In summary, we demonstrate that citrullination can inactivate various SERPINs by distinct mechanisms. Furthermore, we confirmed that SERPIN citrullination actively regulates homeostasis and aberrant citrullination of these proteins alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis. In total, these data provide a clear link between abnormal citrullination and the increased risk of thrombosis.

STAR METHODS

A detailed description of experimental procedures is available in the online version of this paper and includes the following.

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY.

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for reagents should be directed to the corresponding author Paul Thompson (paul.thompson@umassmed.edu

Materials availability

Reagents generated in this study are available upon request with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Post-publication availability of data and code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL DETAILS

DVT mice model

C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks old; both female and male mice were used) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME; Stock 000664). Daily animal care was provided by the animal facility of Boston Children’s Hospital. Animals weighed 25 ± 2 grams at the initiation of surgeries. Experimental procedures in this study were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston Children’s Hospital (protocol no. 20–01-4096R).

METHOD DETAILS

Protein Citrullination.

Protein citrullination was carried out as described previously (Lewallen et al., 2015). Briefly, antiplasmin, antithrombin, and t-PAI (10 μM) were incubated in buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM TCEP, 1 mM CaCl2) with or without a PAD (final concentration 0.2 μM) at 37 °C for 2 h. Proteins incubated under the same conditions in the absence of a PAD enzyme were used as controls. Antithrombin assays were performed in the presence of a saturating concentration of dalteparin sodium (1 mM, Sigma).

Time-dependence of SERPIN Citrullination.

The time-dependence of antiplasmin and antithrombin citrullination were evaluated analogously to previously described methods (Nemmara et al., 2018b). Briefly, SERPINs (10 μM) were incubated in buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM TCEP, 1 mM CaCl2) with or without a PAD (final concentration 0.7 μM) at 37 °C for various time intervals (0, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 90, 105, and 120 min) and flash frozen to stop the reaction. Antithrombin was citrullinated in the presence of dalteparin (1 mM). The samples were then incubated with 20% TCA (10 μL of 100% TCA) and 0.1 mM rhodamine-PG (1 μL of a 5 mM stock) for 30 min at 37 °C. After a 30 min incubation, the reaction was quenched with 10 μL of 0.5 M citrulline dissolved in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6. The solutions were placed on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation (13,500 rpm, 15 min) at 4 °C. The supernatants were discarded, and the protein pellets were washed twice with cold acetone and dried. To eliminate arginine labeling, the pellet was dissolved in 20 μL of buffer containing 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM arginine, 1% SDS, 7% β-mercaptoethanol, and 100 mM NaCl. The samples were further boiled with 6X SDS-PAGE loading dye and sonicated for 15 min and separated by SDS-PAGE (12.5% gel). Bands were visualized by scanning the gel in a Typhoon scanner (excitation/emission maxima ~546/579, respectively). The experiment was carried out in duplicate, the band intensities were quantified using ImageJ software and the data were fit to Equation 1,

| (Equation S1), |

Where F is the normalized fluorescence intensity and F0 is the normalized fluorescence intensity at time zero. k is the pseudo-first order rate constant of SERPIN citrullination by PADs and t is time.

Steady State Kinetics of SERPIN Citrullination.

For these experiments, a standard curve was generated with different concentrations of citrullinated histone H3. Briefly, histone H3 (100 μM) was treated with PAD4 (0.2 μM) in reaction buffer at 37 °C for 1 h. Samples were then treated with 20% TCA and 0.1 mM Rh-PG at 37 °C for 30 min. All samples were quenched with citrulline, cooled, centrifuged, washed, and dried, as described above. After resuspending in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6, samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and imaged on a Typhoon scanner (excitation/emission maxima ~546/579, respectively). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software and the band intensities fit to a linear fit using Equation S2,

| (Equation S2), |

where m is the slope of the line and c is the intercept.

For the kinetic assay, varying concentrations of a SERPIN (0, 0.3125, 0.625, 1.25, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM) were treated with PAD2 (0.3 μM) or PAD4 (0.2 μM) in reaction buffer at 37 °C for 20 min. This incubation time is within the linear range established by the time-dependence experiments described above. Antithrombin was citrullinated in the presence of dalteparin (1 mM). Reactions were then treated with 20% TCA and 0.1 mM Rh-PG at 37 °C for 30 min. All samples were quenched with citrulline, cooled, centrifuged, washed, and dried as described above. The pellets were then resuspended in 20 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 100 mM arginine, 1% SDS, 7% β-mercapto ethanol, and 100 mM NaCl. Next, the samples were separated by SDS-PAGE and imaged on a Typhoon scanner (excitation/emission maxima ~546/579, respectively). Images were analyzed with ImageJ and the initial rates fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation,

| (Equation S3), |

using the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software package. The experiment was carried out in duplicate.

Identification of the Sites of Citrullination.

SERPINs (100 μg) were citrullinated by incubation with PAD2 at 37 °C in 100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM TCEP, and 1 mM CaCl2 with PAD2 (10 μg) for 2 h. Citrullination of antithrombin was carried out in the presence of dalteparin (1 mM). As a control, SERPINs were incubated under the same conditions in the absence of PAD2. Citrullinated proteins were then incubated with 20% TCA (40 μL of 100% TCA) and phenylglyoxal (250 μM) for 3 h at 37 °C. Next, the labeling reaction was quenched with 25 μL of 0.5 M citrulline dissolved in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.6. The solutions were then placed on ice for 30 min followed by centrifugation (13 500 rpm, 15 min) at 4 °C. The supernatants were discarded, and the protein pellets were washed twice with cold acetone and dried. The protein pellets were then sonicated and resolubilized in 6 M urea (30 μL) and 100 mM ammonium bicarbonate (70 μL) solution. Once dissolved, the samples were incubated with 1 M DTT (1.5 μL) for 15 min at 65 °C followed by incubation with 500 mM iodoacetamide (2.5 μL) for 30 min at rt. After 30 min, the samples were diluted to 1 mL final volume with PBS to bring down the urea concentration to ~0.6 M. The samples were then treated with neutrophil elastase (1:20 dilution), Glu-C (1:30 dilution), or trypsin (1:40 dilution) overnight at 37 °C. Next, the samples were dried using a speedVac and resolubilized in Buffer A (5% ACN and 0.5% formic acid) and stored at −20 °C until MS analysis.

LC-MS/MS analysis was performed on an LTQ-Orbitrap Discovery mass spectrometer (ThermoFisher) coupled to an Agilent 1200 series HPLC. Samples were loaded via HPLC autosampler onto a hand-pulled 100 μm fused silica capillary column with a 5 μm tip packed with 10 cm Aqua C18 reverse phase resin (Phenomenex). Peptides were eluted using a gradient from 100% Buffer A (95% water, 5% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid) to 100% Buffer B (20% water, 80% acetonitrile, 0.1% formic acid). The flow rate was set to ~0.25 μL/min and the spray voltage was set to 2.75 kV. One full MS scan was followed by 8 data dependent scans of the 8 most abundant ions. For high resolution runs, a full scan was followed by 4 data dependent scans limited to an inclusion mass list containing the masses of previously identified modified peptides. The tandem MS data were searched using the SEQUEST algorithm using a concatenated target/decoy variant of the human UniProt database. To account for alkylation by iodoacetamide a static modification of +57.02146 on cysteine was specified while a differential modification of +117.0102 was specified on arginine to identify the phenylglyoxal-labeled citrullinated residue. SEQUEST output files were filtered using DTA-Select.

Western Blot Analysis of SERPIN-Protease Interactions.

Citrullination of antiplasmin, antithrombin and t-PAI was carried out as described above. Proteins incubated under the same conditions in the absence of PAD2 were used as controls. Briefly, different concentrations (0, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 μM) of citrullinated and control SERPINs were incubated with 2 μM of their cognate protease (total reaction volume 40 μL) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 30 min. The reactions were quenched with 6X SDS-PAGE loading dye without reducing agent and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. Proteins were then separated on two parallel SDS-PAGE (gradient 4–12%, Bio-Rad) and electro-transferred to PVDF (Bio-Rad). Two membranes were probed with anti-SERPIN and anti-protease antibodies separately. Briefly, the membranes were blocked with 1% BSA in PBST for 1 h at room temperature then incubated with the appropriate primary antibodies (rabbit polyclonal anti-α−2 antiplasmin Cat # 62770 (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-plasminogen Cat # ab154560 (1:1000), rabbit polyclonal anti-antithrombin III Cat # ab180614 (1:1000), mouse monoclonal anti-thrombin Cat # ab17199 (1:1000) and mouse polyclonal anti-tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor Cat # sc5297 (1:1000)) diluted in 5 % BSA in 1x PBS buffer at 4 °C overnight. Membranes were washed with PBST (3X) to remove unbound antibody and then further treated with a corresponding secondary antibody (either goat anti-rabbit Licor IRDye 800CW (1:10,000) or donkey anti-mouse Licor IRDye 800CW (1:10,000)) diluted in 1% BSA in PBST at room temperature for 1 h. The washing step was repeated with PBST and then the blot was imaged, and band intensities were quantified using the Licor Imager Software (700 nm and 800 nm).

Time-dependence of SERPIN-Protease Complex Formation.

Citrullinated and control SERPINs (2.5 μM) were incubated with their cognate proteases (1 μM, total reaction volume 20 μL) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for the indicated periods of time. The reactions were quenched with SDS-PAGE loading dye without reducing agent and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE (gradient 4–12%, Bio-Rad).

Kinetic Analysis of Citrullinated Antiplasmin as a Plasmin Substrate.

To determine the optimal time for cleavage of citrullinated antiplasmin by plasmin, antiplasmin (10 μM) was incubated with or without PAD2 (final concentration 0.2 μM) in buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM TCEP, 1 mM CaCl2) at 37 °C for 2 h. Citrullinated and control antiplasmin (2.5 μM) were then incubated with plasmin (25 nM, total reaction volume 20 μL) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for different periods of time (0, 2, 5, 10, 15, 20, and 30 min). The reactions were quenched with 6X SDS-PAGE loading dye without reducing agent and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE (gradient 4–12%, Bio-Rad). The band intensities were calculated using ImageJ software and plotted against time. The experiment was carried out in triplicate.

To determine the steady state kinetic parameters of citrullinated and control antiplasmin cleavage, different concentrations of citrullinated and control antiplasmin (0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5, and 5 μM) were incubated with plasmin (25 nM, total reaction volume 20 μL) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 5 min. The reactions were quenched with SDS-PAGE loading dye without reducing agent and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (gradient 4–12%, Bio-Rad). The band intensities of cleaved antiplasmin were calculated using a standard curve of cleaved antiplasmin (see below). Since the velocity did not reach saturation under the experimental conditions, the initial rates were fit to a linear fit using the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software package. The experiment was carried out in duplicate. To obtain a standard curve of cleaved antiplasmin, different concentrations of citrullinated antiplasmin (0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, 2.5 μM) were incubated with plasmin (2 μM) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 30 min. The reactions were quenched with SDS-PAGE loading dye without reducing agent and boiled at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE (gradient 4–12%, Bio-Rad). Images were analyzed using ImageJ software and the band intensities fit to a linear fit. The methodology used to determine the steady state kinetic parameters for the cleavage of citrulline-containing peptides is described in detail in the supporting information.

Cleavage of RCL peptides.

The P1 arginine (1) and P1-citrulline (2) containing RCL peptides were ordered from Genewiz. To measure peptide cleavage, different concentrations of 100 μM of peptide 1 and 2 were incubated with plasmin (5 μM) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at various time periods. At varying times, 40 μL of the reaction mixture was injected onto an LC-MS and formation of peptide fragment B (Figure S3B) was monitored. The area under the curve was converted into velocity and fit to a pseudo-first order equation. The experiment was performed in duplicate, and error was calculated from standard deviation.

Preparation of AMC peptide substrates.

Z-Phe-Cit-AMC (Z-FCitAMC). Z-Phe-Cit-AMC was prepared by citrullination of Z-FRAMC (Millipore-Sigma) by PAD1. Z-FRAMC (5 mM, 13 mg in 5 mL) was incubated in buffer (100 mM HEPES pH 7.6, 100 mM NaCl, 500 μM TCEP, 1 mM CaCl2) with 5–10 μM PAD1 at 37 °C for 18 h. Product formation was monitored by LC-MS analysis. The resulting reaction mixture was lyophilized overnight and was purified by HPLC (60% ACN in water). The product was obtained as a white solid (8.4 mg, 65%). [M+H]+ 613.7 (exp), 614.2 (obs).

Steady State Kinetics of Citrulline-containing Peptide Substrates.

Different concentrations of Z-FRAMC and Z-FCitAMC (0,10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 150 and 200 μM) were diluted in buffer (20 mM Tris HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween 20 and 0.1% BSA, total reaction volume 50 μL) into individual wells of a 96-well plate followed by rapid addition of plasmin or thrombin (final concentration 1 μM). Initial rates for substrate hydrolysis were monitored for 50 min using an EnVision fluorometer at excitation/emission maxima of 340/440 nm. The initial rates were fit to the Michaelis-Menten equation. The proteolytic activity was calculated using an AMC standard curve. The experiment was carried out in duplicate.

Plasmin-Antiplasmin Partition Ratio.

Partition ratios were calculated as described previously (Tilvawala et al., 2015; Tilvawala and Pratt, 2013a, b). Briefly, different concentrations of citrullinated and control antiplasmin (0, 0.01, 0.025, 0.05, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.0 μM) were incubated with plasmin (250 nM, total reaction volume 50 μL) in buffer containing 20 mM Tris pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl and 0.01% Tween 20 at room temperature for 30 min. After 30 min, 40 μL of the reaction mixture was placed into individual wells of a 96-well plate followed by rapid addition of the plasmin substrate D-Val-Leu-Lys-pNA (10 μL, final concentration 1.0 mM). Hydrolysis of the latter was monitored spectrophotometrically at 405 nm. The initial rates, proportional to the activity of uninhibited plasmin, were converted into residual plasmin activity and were plotted against [I]/[E]. All experiments were carried out at least in duplicate and error bars were calculated from the standard deviation. The partition ratio (r + 1) was then determined by fitting the data to a linear equation, using the GraphPad Prism 7.0 software package, where [I] is inhibitor concentration, [E] is enzyme concentrations and r is the partition ratio, turnover/kill (k4/k3).

CD Measurements.

CD measurements were carried out on a Jasco Model J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a thermoelectric temperature control system in a 1 cm cuvette (Hellma). Data were recorded every 1 nm from 215 to 265 nm, with an 8 s average time in wavelength scanning mode using a 1 cm path length and a 2.5 nm bandwidth. Citrullination of antiplasmin and antithrombin was carried out as described above. All samples were filtered through a 0.2 μM filter to remove any aggregates and the samples were diluted to 3 μM with final buffer concentrations of 30 mM HEPES, 45 mM NaCl and 0.1 mM CaCl2 for recording CD spectra. The Bradford assay was used to determine protein concentrations. Data obtained for PAD2 alone were subtracted from the PAD2 treated SERPIN samples. Final data was converted to molar ellipticity using Equation S4,

| (Equation S4), |

where MRW is the mean residue ellipticity, c is the concentration in grams per milliliter, and d is the path length in centimeters.

Plasma Clotting Experiments.

The effect of citrullinated antiplasmin, t-PAI, and antithrombin on plasma clotting was measured by the combined clotting and fibrinolysis assay as described previously (Smith et al., 2006). Briefly, clotting was assessed by monitoring turbidity changes. For antiplasmin and t-PAI, different concentrations of citrullinated and control SERPINs were added to an individual well of a 96-well plate containing 60 μL of human pooled normal plasma followed by the rapid addition of buffer containing 8 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.008% Tween 20, 10.6 mM CaCl2, 5 nM uPA, and 10 nM thrombin. The final reaction volume was 200 μL. The change in absorbance over time was monitored at 405 nm. The times required for 50% clot lysis were plotted against antiplasmin concentrations. For t-PAI, the absorbance at 405 nm, proportional to increased plasma clotting was converted to percentage clot lysis and plotted against t-PAI concentrations. The experiments were performed in duplicate and error bars were calculated from the standard deviation. Since heparin derivatives inhibit blood blot formation, antithrombin was citrullinated in the absence of dalteparin.

For antithrombin, different concentrations of citrullinated and control antithrombin (0, 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1.0, 2.5, and 5 μM) were incubated with thrombin (250 nM) for 30 min at room temperature. A portion (12 μL) of this reaction mixture was added to an individual well of a 96-well plate containing 60 μL of human pooled normal plasma followed by the rapid addition of buffer containing 8 mM Tris pH 7.4, 0.008% Tween 20, 10.6 mM CaCl2, and 5 nM uPA. The final reaction volume was 200 μL and the final thrombin concentration was 10 nM. The absorbance at 405 nm, proportional to decreased plasma clotting, was converted into percent clot formation and these data were plotted against antithrombin concentration. The experiments were performed in duplicate and error bars were calculated from the standard deviation.

IVC Ligation and analysis of mice plasma samples.

C57BL/6J mice (8–10 weeks old; both female and male mice were used) were subject to IVC stenosis by partial ligation of the inferior vena cava (IVC) to ~10% of its original diameter. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with 3.5% isoflurane and anesthesia maintained at 2% in 100% oxygen. A midline laparatomy was performed to expose the inferior vena cava that was ligated using 7/0 polypropylene suture. A 30-G spacer was placed parallel to the inferior vena cava to partially ligate the inferior vena cava (IVC) to ~10% of its original diameter. The spacer was then removed, and the mouse sutured and allowed to recover. Any side branches between the renal and iliac veins were also ligated with 7/0 polypropylene suture. After 24 h, blood was collected from the retro-orbital venous plexus into 3.2% sodium citrate. For sham surgeries, the same procedure as the DVT surgery was performed except that the IVC ligation was removed immediately after the temporary occlusion was caused. The blood was collected after 24 h in 3.2% sodium citrate. The mice operated via sham surgery were visually inspected to confirm there was no thrombus formation. The control plasma was collected from C57BL/6J male mice (BW: 27g) without any surgery. Plasma samples were obtained after centrifugation at 6000xg for 5 min followed by 5 min centrifugation at 16,000xg and stored at −80°C.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

The kinetic experiments in Figure 1C, 1D, S1A, S1B, 3B, 3C, S3A, S3C, S3D 4B, 4C and S4C were analyzed using the mean ± standard error. The biotin-PG labeled western blot experiments in Figure 4E and 4F were performed in triplicate and p-values were determined using Student’s t test. Statistical parameters and statistical significance are reported in the Figures and Figure Legends. Data is reported to be statistically significant when p < 0.05 by Student’s t test. ns = P>0.05, * = P≤0.05, ** =P≤0.01, *** = P≤0.001, **** P<0.0001.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-α-2 antiplasmin (to detect human antiplasmin) | Abcam | Cat # 62770 |

| Goat polyclonal anti-α-2 antiplasmin (to detect human cleaved antiplasmin) | Novus Biologicals | cat # NB100–96916 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-α-2 antiplasmin (to detect mouse antiplasmin) | Abcam | Cat # ab231226 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-plasminogen | Abcam | Cat # ab154560 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-antithrombin III | Abcam | Cat # ab180614 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-thrombin | Abcam | Cat # ab17199 |

| Mouse polyclonal anti-tissue plasminogen activator inhibitor | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat # sc5297 |

| Goat anti-rabbit IgG Licor IRDye®800CW | Licor | cat # P/N 925–32211 |

| Streptavidin Licor IRDye®680RD | Licor | cat # P/N 926–68079 |

| Donkey anti-mouse IgG Licor IRDye®800RD | Licor | cat # 926–32212 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human pooled plasma | Affinity Biologicals | Cat # FRNCP0125 |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Human plasmin | Athens Research & Technology, Inc. | Cat # 16–16-161213-L |

| Human α-2 antiplasmin | Athens Research & Technology, Inc. | Cat # 16–16-012901 |

| Human α-thrombin | Haematologic Technologies | Cat # HCT-0020 |

| Human antithrombin III/SERPIN C1 | Haematologic Technologies | Cat # HCA TIII-0120 |

| Human Factor Xa | Haematologic Technologies | Cat # HCXA-0060 |

| Human tissue plasminogen activator-1 (tPA) | Sigma | Cat # 612200-M |

| Recombinant human plasminogen activator inhibitor/SERPIN E1 | Sigma | Cat # A8111 |

| Human plasmin substrate D-Val-Leu-Lys-pNA | Sigma | Cat # V7127 |

| Human α-thrombin substrate tosyl-Gly-Pro-Ala-pNA | Sigma | Cat # 10206849001 |

| Human t-PA substrate methyl sulfonyl D-hexahydro-tyrosine-Gly-Arg-pNA | Sigma | Cat # 612200-M |

| Dalteparin sodium | Sigma | Cat # D0070000 |

| H-Arg-AMC•HCl | Bachem AG, Switzerland | 4002148.0250 |

| H-Cit-AMC•HBr | Biosynth | Cat #C-6200 |

| Z-Phe-Arg-AMC | Bachem | Cat # 4003379.0250 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C57BL/6J (8–10 weeks old; both female and male mice) Mouse Plasma (DVT, sham and control) | Provided by Prof. Denisa Wagner, Harvard Medical | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 7.0 | GraphPad software Inc | https://www.graphpad.com |

LIFE SCIENCE TABLE WITH EXAMPLES FOR AUTHOR REFERENCE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-Snail | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3879S; RRID: AB_2255011 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-Tubulin (clone DM1A) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T9026; RRID: AB_477593 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-BMAL1 | This paper | N/A |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| pAAV-hSyn-DIO-hM3D(Gq)-mCherry | Krashes et al., 2011 | Addgene AAV5; 44361-AAV5 |

| AAV5-EF1a-DIO-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP | Hope Center Viral Vectors Core | N/A |

| Cowpox virus Brighton Red | BEI Resources | NR-88 |

| Zika-SMGC-1, GENBANK: KX266255 | Isolated from patient (Wang et al., 2016) | N/A |

| Staphylococcus aureus | ATCC | ATCC 29213 |

| Streptococcus pyogenes: M1 serotype strain: strain SF370; M1 GAS | ATCC | ATCC 700294 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Healthy adult BA9 brain tissue | University of Maryland Brain & Tissue Bank; http://medschool.umaryland.edu/btbank/ | Cat#UMB1455 |

| Human hippocampal brain blocks | New York Brain Bank | http://nybb.hs.columbia.edu/ |

| Patient-derived xenografts (PDX) | Children's Oncology Group Cell Culture and Xenograft Repository | http://cogcell.org/ |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| MK-2206 AKT inhibitor | Selleck Chemicals | S1078; CAS: 1032350–13-2 |

| SB-505124 | Sigma-Aldrich | S4696; CAS: 694433–59-5 (free base) |

| Picrotoxin | Sigma-Aldrich | P1675; CAS: 124–87-8 |

| Human TGF-β | R&D | 240-B; GenPept: P01137 |

| Activated S6K1 | Millipore | Cat#14–486 |

| GST-BMAL1 | Novus | Cat#H00000406-P01 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| EasyTag EXPRESS 35S Protein Labeling Kit | PerkinElmer | NEG772014MC |

| CaspaseGlo 3/7 | Promega | G8090 |

| TruSeq ChIP Sample Prep Kit | Illumina | IP-202–1012 |

| Deposited data | ||

| Raw and analyzed data | This paper | GEO: GSE63473 |

| B-RAF RBD (apo) structure | This paper | PDB: 5J17 |

| Human reference genome NCBI build 37, GRCh37 | Genome Reference Consortium | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/genome/assembly/grc/human/ |

| Nanog STILT inference | This paper; Mendeley Data | http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/wx6s4mj7s8.2 |

| Affinity-based mass spectrometry performed with 57 genes | This paper; Mendeley Data | Table S8; http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/5hvpvspw82.1 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Hamster: CHO cells | ATCC | CRL-11268 |

| D. melanogaster: Cell line S2: S2-DRSC | Laboratory of Norbert Perrimon | FlyBase: FBtc0000181 |

| Human: Passage 40 H9 ES cells | MSKCC stem cell core facility | N/A |

| Human: HUES 8 hESC line (NIH approval number NIHhESC-09–0021) | HSCI iPS Core | hES Cell Line: HUES-8 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C. elegans: Strain BC4011: srl-1(s2500) II; dpy-18(e364) III; unc-46(e177)rol-3(s1040) V. | Caenorhabditis Genetics Center | WB Strain: BC4011; WormBase: WBVar00241916 |

| D. melanogaster: RNAi of Sxl: y[1] sc[*] v[1]; P{TRiP.HMS00609}attP2 | Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC:34393; FlyBase: FBtp0064874 |

| S. cerevisiae: Strain background: W303 | ATCC | ATTC: 208353 |

| Mouse: R6/2: B6CBA-Tg(HDexon1)62Gpb/3J | The Jackson Laboratory | JAX: 006494 |

| Mouse: OXTRfl/fl: B6.129(SJL)-Oxtrtm1.1Wsy/J | The Jackson Laboratory | RRID: IMSR_JAX:008471 |

| Zebrafish: Tg(Shha:GFP)t10: t10Tg | Neumann and Nuesslein-Volhard, 2000 | ZFIN: ZDB-GENO-060207–1 |

| Arabidopsis: 35S::PIF4-YFP, BZR1-CFP | Wang et al., 2012 | N/A |

| Arabidopsis: JYB1021.2: pS24(AT5G58010)::cS24:GFP(-G):NOS #1 | NASC | NASC ID: N70450 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| siRNA targeting sequence: PIP5K I alpha #1: ACACAGUACUCAGUUGAUA | This paper | N/A |

| Primers for XX, see Table SX | This paper | N/A |

| Primer: GFP/YFP/CFP Forward: GCACGACTTCTTCAAGTCCGCCATGCC | This paper | N/A |

| Morpholino: MO-pax2a GGTCTGCTTTGCAGTGAATATCCAT | Gene Tools | ZFIN: ZDB-MRPHLNO-061106–5 |

| ACTB (hs01060665_g1) | Life Technologies | Cat#4331182 |

| RNA sequence: hnRNPA1_ligand: UAGGGACUUAGGGUUCUCUCUAGGGACUUAGGGUUCUCUCUAGGGA | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pLVX-Tight-Puro (TetOn) | Clonetech | Cat#632162 |

| Plasmid: GFP-Nito | This paper | N/A |

| cDNA GH111110 | Drosophila Genomics Resource Center | DGRC:5666; FlyBase:FBcl0130415 |

| AAV2/1-hsyn-GCaMP6- WPRE | Chen et al., 2013 | N/A |

| Mouse raptor: pLKO mouse shRNA 1 raptor | Thoreen et al., 2009 | Addgene Plasmid #21339 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| ImageJ | Schneider et al., 2012 | https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ |

| Bowtie2 | Langmead and Salzberg, 2012 | http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2/index.shtml |

| Samtools | Li et al., 2009 | http://samtools.sourceforge.net/ |

| Weighted Maximal Information Component Analysis v0.9 | Rau et al., 2013 | https://github.com/ChristophRau/wMICA |

| ICS algorithm | This paper; Mendeley Data | http://dx.doi.org/10.17632/5hvpvspw82.1 |

| Other | ||

| Sequence data, analyses, and resources related to the ultra-deep sequencing of the AML31 tumor, relapse, and matched normal | This paper | http://aml31.genome.wustl.edu |

| Resource website for the AML31 publication | This paper | https://github.com/chrisamiller/aml31SuppSite |

PHYSICAL SCIENCE TABLE WITH EXAMPLES FOR AUTHOR REFERENCE.

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| QD605 streptavidin conjugated quantum dot | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#Q10101MP |

| Platinum black | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#205915 |

| Sodium formate BioUltra, ≥99.0% (NT) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#71359 |

| Chloramphenicol | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C0378 |

| Carbon dioxide (13C, 99%) (<2% 18O) | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories | CLM-185–5 |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) | Sigma-Aldrich | 427179 |

| PTFE Hydrophilic Membrane Filters, 0.22 μm, 90 mm | Scientificfilters.com/Tisch Scientific | SF13842 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Folic Acid (FA) ELISA kit | Alpha Diagnostic International | Cat# 0365–0B9 |

| TMT10plex Isobaric Label Reagent Set | Thermo Fisher | A37725 |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance CM5 kit | GE Healthcare | Cat#29104988 |

| NanoBRET Target Engagement K-5 kit | Promega | Cat#N2500 |

| Deposited data | ||

| B-RAF RBD (apo) structure | This paper | PDB: 5J17 |

| Structure of compound 5 | This paper; Cambridge Crystallographic Data Center | CCDC: 2016466 |

| Code for constraints-based modeling and analysis of autotrophic E. coli | This paper | https://gitlab.com/elad.noor/sloppy/tree/master/rubisco |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| Gaussian09 | Frish et al., 2013 | https://gaussian.com |

| Python version 2.7 | Python Software Foundation | https://www.python.org |

| ChemDraw Professional 18.0 | PerkinElmer | https://www.perkinelmer.com/category/chemdraw |

| Weighted Maximal Information Component Analysis v0.9 | Rau et al., 2013 | https://github.com/ChristophRau/wMICA |

| Other | ||

| DASGIP MX4/4 Gas Mixing Module for 4 Vessels with a Mass Flow Controller | Eppendorf | Cat#76DGMX44 |

| Agilent 1200 series HPLC | Agilent Technologies | https://www.agilent.com/en/products/liquid-chromatography |

| PHI Quantera II XPS | ULVAC-PHI, Inc. | https://www.ulvac-phi.com/en/products/xps/phi-quantera-ii/ |

Highlight.

Citrullinated SERPINs regulate the coagulation and fibrinolysis cascades

Citrullinated antithrombin and t-PAI lose their ability to bind cognate proteases.

Citrullinated antiplasmin is a plasmin substrate not an inhibitor.

SERPIN citrullination shifts the equilibrium towards thrombus formation in DVT.

Significance.

Increased protein citrullination is associated with numerous autoimmune diseases and cancer, however, the specific effects of this modification remain mostly unknown. We previously identified the RA-associated citrullinome and demonstrated that serine protease inhibitors (SERPINs) are highly citrullinated in RA patients. SERPINs regulate the coagulation and fibrinolysis cascades. In this study, we show that SERPIN citrullination can alter coagulation and fibrinolysis cascades. These data reconcile two long standing observations; that both protein citrullination and thrombosis are elevated in autoimmunity and suggest that aberrant SERPIN citrullination contributes to pathological thrombus formation.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grant R35GM118112 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences to P.R.T and grant R35 HL135765 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health to D.D.W.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

D.D.W. is on the Scientific Advisory Board of Neutrolis, a preclinical-stage biotech company focused on DNases.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Ashton-Rickardt PG (2013). An emerging role for Serine Protease Inhibitors in T lymphocyte immunity and beyond. Immunol Lett 152, 65–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brighton TA, Eikelboom JW, and Simes J (2013). Aspirin for preventing venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 368, 773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brill A, Fuchs TA, Savchenko AS, Thomas GM, Martinod K, De Meyer SF, Bhandari AA, and Wagner DD (2012). Neutrophil extracellular traps promote deep vein thrombosis in mice. J Thromb Haemost 10, 136–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carpenter SL, and Mathew P (2008). Alpha2-antiplasmin and its deficiency: fibrinolysis out of balance. Haemophilia 14, 1250–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HH, Liu GY, Dwivedi N, Sun B, Okamoto Y, Kinslow JD, Deane KD, Demoruelle MK, Norris JM, Thompson PR, et al. (2016). A molecular signature of preclinical rheumatoid arthritis triggered by dysregulated PTPN22. JCI Insight 1, e90045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapin JC, and Hajjar KA (2015). Fibrinolysis and the control of blood coagulation. Blood Rev 29, 17–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christophorou MA, Castelo-Branco G, Halley-Stott RP, Oliveira CS, Loos R, Radzisheuskaya A, Mowen KA, Bertone P, Silva JC, Zernicka-Goetz M, et al. (2014). Citrullination regulates pluripotency and histone H1 binding to chromatin. Nature 507, 104–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumanevich AA, Causey CP, Knuckley BA, Jones JE, Poudyal D, Chumanevich AP, Davis T, Matesic LE, Thompson PR, and Hofseth LJ (2011). Suppression of colitis in mice by Cl-amidine: a novel peptidylarginine deiminase inhibitor. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 300, G929–938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung WS, Peng CL, Lin CL, Chang YJ, Chen YF, Chiang JY, Sung FC, and Kao CH (2014). Rheumatoid arthritis increases the risk of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary thromboembolism: a nationwide cohort study. Ann Rheum Dis 73, 1774–1780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damgaard D, Senolt L, Nielsen MF, Pruijn GJ, and Nielsen CH (2014). Demonstration of extracellular peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) activity in synovial fluid of patients with rheumatoid arthritis using a novel assay for citrullination of fibrinogen. Arthritis Res Ther 16, 498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]