Abstract

Diseases bring about the need for interventions that pinpoint each specific aspect of the illness. Commonly, remission of a complex disease is accomplished by mixing treatments, medications, and therapeutics together in a fashion where they may negatively interact with each other or never arrive at the diseased site as a systemic heterogeneous mixture. Chronic wounds display intricacy as they are very localized and have their own environment where tissue deconstruction due to high levels of numerous proteases outweighs normal tissue reconstruction. This idea leads to the necessity of a protein that contains low diffusivity rates for localized treatment, strength against high concentrations of proteolytic species that lead to degradation of short chain peptides, while encompassing broad inhibitory effects against multiple proteases. Elastin-Like Peptides are an attractive, thermoresponsive, protein-based drug delivery partner as they contain low diffusivity and serve as a stable architecture for short chain peptide fusion. In this project, a novel elastin-like peptide-based protein has been created to target the inhibition of both human neutrophil elastase and matrix metalloprotease-2. As a biologic, this is unique as it is a protein with specific biological activities against multiple proteases, ultimately displaying the potential to mix and match differing biologically active peptides within one amino acid sequence.

Keywords: wound healing, multifunctional proteins, protease inhibitor, elastin-like peptide, combination therapy

INTRODUCTION

Diseases that are complex in cause often require drug combinations for treatment1. Drug combinations provide the term “broad spectrum treatment” in a conventional response to complex causes of disease. Combination therapies are considered a mixture of biologics, drugs, or both by combining them heterogeneously to broaden the therapeutic effect2. For example, a persistence in the body’s inability to replace damaged tissue in a timely manner result in chronic wounds. This may be caused by other underlying diseases such as autoimmune disorders, poor vascularization, or imbalances in metabolic processes as seen in diabetes3. All the latter may require systemically delivered medications to treat these underlying diseases, so it is advantageous to treat resulting chronic wounds with a point specific and broad spectrum therapeutic in order to decrease interactions between therapeutics in other areas of the body. Moreover, chronic wounds also present high activity of protein degrading enzymes known as proteases. Proteases are an important part of tissue remodeling and repair as they are responsible for breaking down the extracellular matrix (ECM) making it possible for tissue remodeling. Wound healing is an intricate set of processes with diverse amounts of proteases and protease inhibitors that are involved in proper wound healing processes such as the need for proteases to tear down old or damaged tissue4, but with limitation and means of inhibition5,6. Therefore, there exists a fine balance between proteases and protease inhibitors to accomplish the successful breaking down and remodeling of the ECM, making protease levels an important factor when evaluating the cause of chronicity of a wound7. Therefore, if the rate of ECM destruction is greater than the rate of remodeling, then a wound will not heal, which leads to chronicity8,9 and the absence of a well-developed ECM9. Several studies have shown a correlation between high levels of proteases and non-healing wounds6,8–12. High levels of neutrophil derived proteases, neutrophil elastase13, and matrix-metalloprotease (MMP)11 have been associated with increased probability of non-healing wounds14.

Therefore, an attractive approach for therapeutic development for chronic wounds is to focus on inhibition of these highly active proteases to restore balance between ECM remodeling and degradation6,11. Peptide based inhibitors of proteases are attractive as they are derived from naturally occurring amino acids. Also, specific peptides can offer inhibitory activity against specific proteases. However, there are downfalls when using peptides. Some of these shortcomings are their vulnerability to being destroyed quickly15 as well as their diffusional properties causing them to quickly leave the application site and spread into other tissues and areas of the body16. This leads to the need for a delivery method that provides diffusional control and protection against degradation.

Peptides have shown promise as drug delivery platforms due to being easily editable4 and some noted for repetitive subunits lending an inherent ability to self-assemble17. Elastin-like-Peptides (ELPs) offer an attractive drug delivery platform due to their unique phase transition property18. Since they are genetically encodable, fusion proteins containing the peptide to be delivered can be synthesized using standard cloning approaches19,20. Our lab and several others have shown that these fusion proteins retain the phase transition properties of ELP as well as the activity of the fused protein21,22. The phase transition properties of ELPs allow them to self-assemble and aggregate at body temperature, which may provide prolonged presence in the application site16 as well as the opportunity to create larger bioactive materials23. Thus, ELPs have proven to be useful in not only for protein purification but also as bioactive peptide delivery platforms16,17,24.

A peptide-based inhibitor was reported to impede the activity of two proteases that are highly active in chronic wounds namely neutrophil elastase (HNE)12,25 and Matrix metalloprotease-2 (MMP-2)5,10. Two peptides, PMPD212 and APP-IP26, block HNE and MMP-2 respectively and were fused to each end of an ELP. The objective is to create a single protein that can maintain phase transitioning properties of an ELP for the utility of sustained release, while exhibiting multifunctional bioactivity. Although it is shown here for protease inhibitors, this strategy can be broadened to incorporate two molecules targeting two different processes into a single molecule for targeted delivery of combination treatments.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1. Plasmid construction

The Elastin-like Peptide (ELP) used as a part of the fusion protein is L10FLAG, which is denoted by the sequence27 [(VPGVG)2(VPGLG)(VPGVG)2]10 DYKDDDDK. PMP-D2 is denoted by the amino acid sequence EEKCTPGQVKQQDCNTCTCTPTGVWGCTLMGCQPA. APP-IP is denoted by the amino sequence ISYGNDALMP. The nucleic acid sequences for the three amino acid sequences used to create PMP-D2٠L10FLAG٠APP-IP were obtained in plasmid form in pUC19 or pUC57 from GenScript®. The gene for PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP was constructed by cutting PMPD2 from a pUC57 plasmid using PflMI and BglI restriction enzymes19. L10FLAG pUC19 was linearized using PflMI restriction enzyme19. A ligation was performed between the PMP-D2 fragment and the linearized L10FLAG pUC19 to form PMPD2-L10FLAG pUC19 plasmid. Then PMPD2-L10FLAG was cut out of the pUC19 plasmid using PflMI and BglI restriction enzymes19, while APP-IP pUC57 plasmid was linearized using PflMI. A ligation was performed between the PMPD2L10FLAG fragment and the linearized APP-IP pUC57 to form PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP pUC57 plasmid. Using the same techniques PMPD2-L10FLAG and APP-IP-L10FLAG was created to use as comparable inhibitors of NE and MMP-2 respectively. Figure 1 displays the cloning scheme for the construction of the plasmid containing PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP.

Figure 1. Cloning scheme for expression plasmid construction for the hybrid dual protease inhibitor, PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP.

PMPD2 encoding region was excised from PUC57 plasmid and cloned into PUC19-L10-Flag (ELP) to yield a plasmid containing the PMPD2-ELP gene as described in materials and methods. The gene PMPD2-ELP was then excised and cloned in the pUC57 plasmid containing genetic information for the protease inhibitor, APP-IP. This yielded the plasmid, PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP. The new plasmid was verified using PCR and gel electrophoresis. Once verified PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP was cut out of the pUC57 plasmid and ligated in the expression plasmid pET-25b+. The new plasmid verified using sanger sequencing. After verification, the plasmid was transformed into E. coli BLR(DE3) for protein expression.

2. Protein expression and purification

The gene was cut out of the pUC57 plasmid using PflMI and BglI and each inserted into a pET25b plasmid. After confirmation of the correct genes using sanger sequencing, the plasmid was transformed into BLR(DE3) cells for expression of the protein19,20. After a transformation one colony of the new plasmid was used to inoculate 75 mL of Terrific Broth growth media. After an 18-hour incubation the 75 mL culture was each placed into a liter of Terrific Broth growth media19. After a 24-hour incubation the culture was pelleted and resuspended in 160 mL of 1XPBS. After resuspension, the sample was sonicated to lyse the cells and release the proteins into solution19. Inverse phase transitioning was utilized to purify the protein from the cell lysate. For PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP, its isoelectric point was utilized to purify the protein sample because of the fusion of charged regions on each side of the ELP. The cell lysate first underwent a centrifugation at 4°C to remove cellular debris. Then the supernatant containing the proteins was collected and heated19,20 to 42°C to transition the target protein, then centrifuged at the same temperature. After the hot spin cycle the pellet was resuspended in 100 mL of cold 1XPBS. Three more cold and hot spin cycles were performed19. The suspension of PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP underwent a pH adjustment to the protein’s isoelectric point before each hot spin cycle. After the cycles were complete each sample was resuspended in 4°C distilled water and dialyzed. After 24 hours of dialysis the samples were frozen and then lyophilized.

3. Protease inhibition assays

Enzo Life Science’s® colorimetric drug discovery kits and protocols were used for the evaluation of MMP-2 and NE inhibition for PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP. Various concentrations of protein were used evaluated to locate the 50% inhibitory concentrations. The experiments were carried out in triplicate. Levels of inhibition for various concentrations of PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP were compared to a control and the level of inhibition of experimental groups for both singular fusions, PMPD2-L10FLAG and APP-IP-L10FLAG to ensure dual fusion does not affect the inhibitory capabilities of the combinatory protein.

The NE inhibition assay was carried out by diluting the NE enzyme (2.0 mU/μl) 1/90 in NE assay buffer (100mM HEPES, pH 7.25, 500mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween-20) and 5 μl of the dilute NE was placed in each well of the 96-well plate for a final concentration of 0.22 mU per well (1 U= U=1.0 μmole of substrate per minute). The substrate (20 mM) was diluted 1/10 in assay buffer and 10 μl of the dilute substrate was placed in each well for a final concentration of 100 μM in each well. Appropriate amounts of assay buffer were placed in each well of the 96-well plate to bring the total volume up to 100 μl. Experimental groups were formed by using adding appropriated amounts of each inhibitor diluted in assay buffer to wells containing enzyme and substrate and the total volume was brought up to 100 μl for each well by adding assay buffer. For NE inhibition the various concentrations of protein inhibitors tested were 5×10−7, 5×10−6, 1×10−5, and 5×10−4 μg/μl. A control (NE enzyme and substrate, no inhibitor) was used in triplicate. In addition, an in triplicate blank consisting of 90 μl assay buffer and 10 μl of dilute substrate was per well was used to blank the control. Protein blanks were also used in triplicate to ensure that the various concentrations of protein do not affect the measurement of absorbance. The average of the blanks was subtracted from the average absorbance of the control and similarly average absorbance of the blanks for each protein concentration was subtracted from average absorbance of the correlating protein concentration of the experimental groups. Table 1 represents the components of the control, blanks, and experimental groups. Before the substrate was added, the plate was warmed to 37°C. Then absorbance at 412 nm was measured over a 15-minute period in 1-minute intervals.

Table 1.

Experimental Design for the Evaluation of NE Inhibition.

| Group | Contents |

|---|---|

| Blank | Assay Buffer |

| Control | Assay Buffer+NE+Substrate |

| PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP (Exp. Group) |

NE+Substrate+Protein at various concentrations |

| PMPD2-L10FLAG (Exp. Group) |

NE+Substrate+Protein in Assay buffer at various concentrations |

| APP-IP-L10FLAG (Exp. Group) |

NE+Substrate+Protein in Assay Buffer at various concentrations |

| Blanks for protein experimental groups | Protein in Assay Buffer at various concentrations |

Likewise, the MMP-2 inhibition assay was carried out similarly. MMP-2 enzyme was diluted 1/56 in MMP-2 assay buffer (50mM HEPES, 10mM CaCl2, 0.05% Brij-35, 1mM DTNB, pH7.5). Then 20 μl of the dilute enzyme was placed in each needed well of the 96-well plate for a final concentration of 1.6 U per well (1 U= 100 pmol of substrate per minute). The MMP-2 substrate (25 mM) was diluted 1/25 in MMP-2 assay buffer and 10 μl of diluted substrate was added to each needed well of a 96-well plate for a final concentration of 100 μM in each well. Appropriate amounts of assay buffer were placed in each well of the 96-well plate to bring the total volume up to 100 μl. Experimental groups were formed by adding appropriated amounts of each inhibitor diluted in assay buffer to wells containing enzyme and substrate and the total volume was brought up to 100 μl for each well by adding assay buffer. The various concentrations of each protein inhibitor tested for MMP-2 inhibition was 0.004, 0.008, 0.01, 0.05, 0.2, and 0.5 μg/μl. A control (MMP-2 enzyme and substrate, no inhibitor) was used in triplicate. In addition, an in-triplicate blank consisting of 90 μl of assay buffer per well and 10 μl of dilute substrate was used to blank the control. Protein blanks were also used in triplicate to ensure that the various concentrations of protein do not affect the measurement of absorbance. The average of the blanks was subtracted from the average absorbance of the control and similarly average absorbance of the blanks for each protein concentration was subtracted from average absorbance of the correlating protein concentration of the experimental groups. Table 2 represents the components of the control, blanks, and experimental groups. Before the substrate was added, the plate was warmed to 37°C. Then absorbance at 412 nm was measured over a 15-minute period in 1-minute intervals.

Table 2.

Experimental Design for the Evaluation of MMP-2 Inhibition.

| Group | Contents |

|---|---|

| Blank | Assay Buffer |

| Control | Assay Buffer+MMP-2+Substrate |

| PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP (Exp. Group) |

MMP-2+Substrate+Protein in Assay Buffer at various concentrations |

| APP-IP-L10FLAG (Exp. Group) |

MMP-2+Substrate+Protein in Assay Buffer at various concentrations |

| PMPD2-L10FLAG (Exp. Group) |

Assay Buffer+MMP-2+Substrate+Protein at various concentrations |

| Blanks for experimental groups | Protein in assay at various concentrations |

The average absorbance of each kinetic reading for the control and experimental groups were blanked. Data analysis was accomplished by normalizing the slopes of the blanked experimental groups at various concentrations and time points to the control to evaluate percent inhibition.

4. Cell toxicity experiment

A549 cells were plated in a 24-well plate at a density of 50,000 cells per well in DMEM 10%FBS 1% AA. After 24 hours the media was removed from the wells and replaced with serum free DMEM 1%AA with 3 different concentrations of protein and a control absent of protein in triplicate. After 24-hour incubation with the protein a Hoechst assay was performed by removing the media from each well on the 24 well plate. Then the cells were washed using 1XPBS. After being washed the 400 μl of distilled H2O was added to each well and a freeze thaw cycle was performed by placing the 24-well plate in −80°C for 10 minutes and then thawed in 37°C for 30 minutes. The freeze thaw cycle was performed 3 times to ensure the cells were lysed. Next 100 μl of Hoechst solution with 100 μl of each sample was added to a 96-well plate. The plate was shaken for 30 seconds and fluorescence was read in a plate reader at 360 nm excitation and 460 nm emission. A triplicate blank of consisting of Hoechst solution was subtracted from the control and the experimental groups.

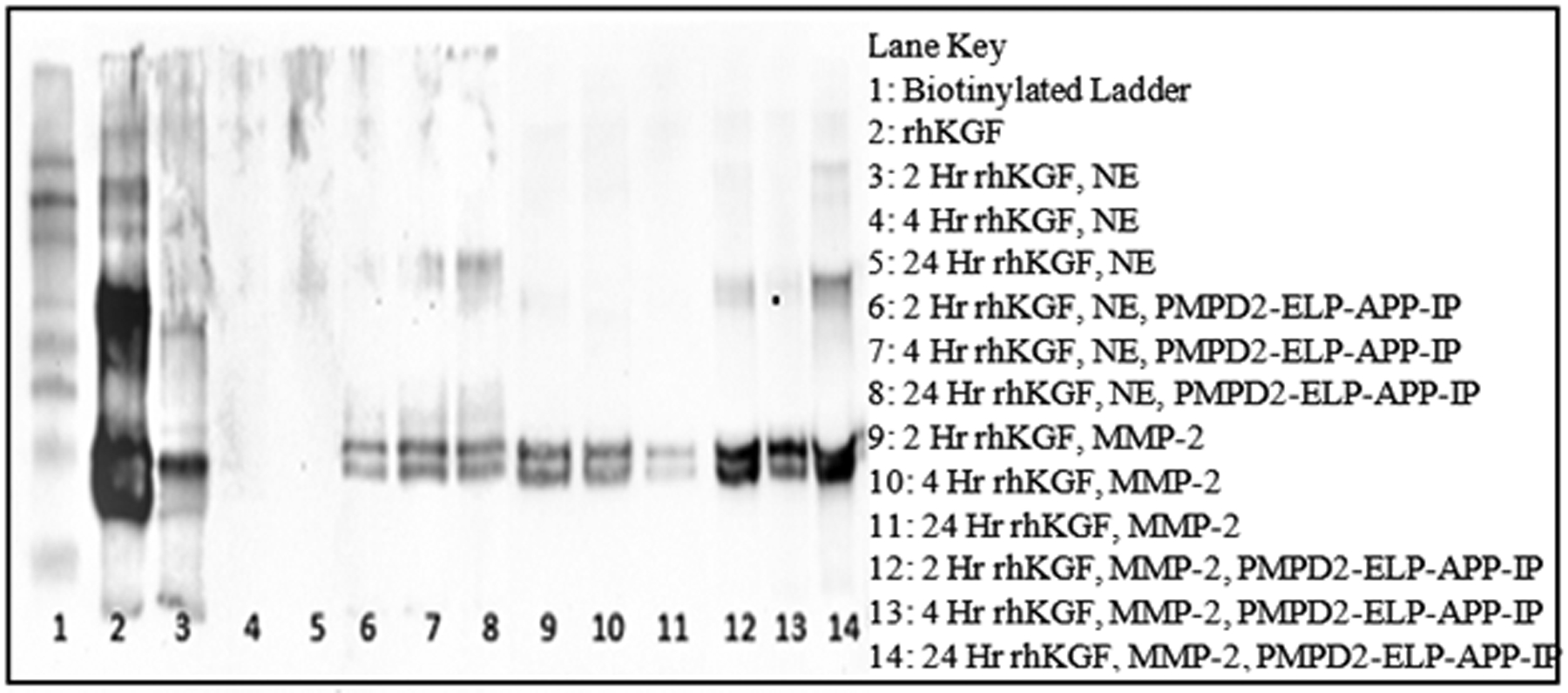

5. Protection from proteolytic degradation of Growth Factor, rhKGF

PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP was used to evaluate the protection of KGF from degradation due to NE and MMP-2. A recombinant KGF was used by creating a 10 μg/ml stock solution of rhKGF. From the stock solution 2.5 μl of 10 μg/mL rhKGF was mixed with 5 μl of a 10 mg/ml stock solution of PMP-D2L10FLAGAPP-IP in NE assay buffer. HNE (2.0 mU/μl) obtained from Enzo Life Sciences®. Then 1.56 μl of the dilute NE was added with 15.94 μl of NE assay buffer to bring the total volume up to 25 μl with a final HNE concentration of 250 μU/μl12. A positive control was made by mixing 2.5 μl of 10 μg/mL rhKGF with 1.56 μl of NE and 20.94 μl of NE assay buffer. An original sample was made by mixing 2.5 μl of 10 μg/mL rhKGF and 22.5 μl of NE assay buffer. The same was done for MMP-2. MMP-2 (150 U) from Enzo Life Sciences® was obtained and reconstituted. The final experiment concentration of MMP-2 was 11.6 mU/μl by mixing 3 μl of MMP-2 stock solution with 2.5 μl of rhKGF 10 μg/mL stock solution and 5 μl of 10 mg/mL PMP-D2-L10FLAG-APP-IP and then brought up to a 25 μl mixture by adding MMP-2 assay buffer. A positive control was also made by mixing 3 μl of MMP-2, 2.5 μl of 10 μg/mL rhKGF, and assay buffer to make a 25 μl mixture. The 5 microcentrifuge vials with the original sample, controls, and the experimental groups were placed in a 37°C hot bath and incubated for 24-hours. Throughout the incubation period 6 μl samples were taken from the positive controls and the experimental groups at 2, 4, and 24 hours12. After 24 hours a 6 μl sample was taken from the original sample to evaluate degradation in the positive control and the experimental group. The 6 μl samples were annealed at 96°C with 1XDDT/Red Loading Dye and then they were placed in a SDS-PAGE gel with a 8 μl of biotinylated ladder and ran for 1 hour at 150 V in 1XRunning Buffer. After running for 1 hour the samples were transferred to a membrane in 1XTransfer Buffer for 1 hour at 350 mA. A TBS/Tween (100 mL of 10XTBS + 900ml of diH2O + 500 μl of Tween) solution was made. After the 1 hour transferring procedure membrane blocking was done by making a 10 mL 5% milk/TBS/Tween solution and agitated with the membrane for 1 hour. After 1 hour the 5% Milk/TBS/Tween solution removed and replaced with a 5% Milk TBS/Tween solution with 14 μl of Rabbit Anti-Human KGF antibody and incubated over night while agitated at 4°C. After overnight incubation, the membrane was washed 3 times for 5-minute intervals in 10 mL of TBS/Tween. Then the membrane was agitated for 1 hour in 5 mL of 5% Milk TBS/TWEEN solution containing 2 μl of Anti-Rabbit antibody and 10 μl of Anti-biotin. After the 1-hour incubation the membrane was washed 3 times in TBS/Tween solution for 5-minute intervals. After 3 washes the membrane was placed in 10 μl of exposing solution (9 mL of diH2O + 500 μl of lumiglo + 500 μl of peroxide reagent) and agitated for 1 minute. The membrane was then exposed to chemiluminescence for 15 minutes and an image was taken.

6. Statistical analysis

For each kinetic inhibition experiment for both NE and MMP-2, each protein and protein concentration were tested in triplicate (N=3) and standard error of the mean absorbance for each data point was calculated. The slope of latter inhibition curves for each protein at each concentration was normalized to the control’s slope. From the latter, percent inhibition for each protein concentration was calculated.

Statistical analysis of the cytotoxicity experiment was performed by normalizing the average fluorescence of experimental groups to the average fluorescence of the control. Then standard deviation of the normalized data was calculated and applied to the graph displaying the results of the Hoechst assay.

RESULTS

1. Gene confirmation, expression, and protein purification

The gene encoding the fusion protein PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP was successfully cloned in the expression plasmid pET25b+ using recursive directional ligation as described previously19. The cloned gene sequence was verified by Sanger sequencing (Supplementary Figure 1A–B). The fusion protein was successfully expressed and purified using inverse temperature cycling. After three cycles, purified protein was obtained (Figure 2A). The predicted molecular weight of 26.8 kDa was in line with the observed molecular weight of the fusion protein in the gel. In addition, the protein was detected and confirmed (Figure 2B) utilizing a western blot specifically targeting the FLAG-tag region of the protein.

Figure 2. Inverse temperature cycling results in successful purification of the hybrid dual protease inhibitor.

After protein expression of PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP in BLR(DE3) cells, the cells were then lysed, and the protein was purified using inverse temperature cycling. A) A total protein stain was performed by running the samples down an SDS-PAGE gel then transferring the samples to a nylon membrane, which was then exposed to Coomassie Blue G250 reagent. The subsequent total protein stain displays in Lane 1 of the figure, a biotinylated ladder; lane 2, a sample of the lysate; and lane 3, a sample of the final purified protein. B) A western blot was then performed with specificity to PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP’s FLAG-tag region. Lane 1: biotinylated ladder and Lane 2: purified protein. The biotinylated ladder was detected using anti-biotin HRP-linked antibody, while the target protein was detected utilizing Anti-FLAG (Rabbit) primary antibody and anti-Rabbit IgG HRP-linked secondary antibody. The mass of the purified protein is 26.8 kDa, which the protein’s band aligns with the corresponding band of the biotinylated ladder in the corresponding image.

2. Neutrophil elastase (NE) inhibition

Next, the inhibition of the neutrophil elastase by the dual protease inhibitor was evaluated in order to display a maintinance of activity held by the PMPD2 domain of the protein. An enzyme-based substrate assay was used to test the inhibition of neutrophil elastase. Indeed the dual protease inhibitor completely inhibted NE at a concentration of 5×10−4 μg/μl (Figure 3A). The dual protease inhibitor inhibited NE just as effectively as the single protease inhibitor PMPD2-ELP (Figure 3B). However, as expected APP-IP-ELP did not inhibit NE inhibition at similar concentrations (Supplementary Figure 2). To quantitatively compare the inhibitory activity of the dual inhibitor with the single inhibitors the IC50 was evaluated for each inhibitor. The calculated IC50 for the dual protease inhibitor was 8.5×10−7 μg/μl, while of the single protease inhibitor PMPD2-ELP was 7.08×10−6 μg/μl. On the other hand, APP-IP-ELP did not similarly inhibit NE demonstrating that PMPD2 is responsible for majority of NE inhibition by the dual protease inhibitor. The comparisons can be visualized in the Lineweaver–Burk plot of 1/activity versus 1/[protein] (Figure 3C). In Figure 3C, it can be observed that both the dual protease inhibitor and PMPD2-ELP display an increase in inhibitory activity against NE as their concentrations are increased. While APP-IP-ELP contains a near zero slope over various protein concentrations indicating insufficient activity against NE (Figure 3C). APP-IP-ELP contained 8.4% inhibition of NE near the IC50 of the dual inhibitor leading us to hypothesize that APP-IP domain contains some activity against NE, ultimately leading to the difference in IC50 between the dual inhibitor and PMPD2-ELP.

Figure 3. The dual protease inhibitor inhibits Neutrophil Elastase (NE) like NE inhibitor, PMPD2-ELP.

A kinetic colorimetric NE inhibition assay was performed to evaluate various concentrations of A) PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP and B) PMPD2-L10-ELP. C) From the kinetic inhibition assays, slope (activity) was calculated for each protein concentration and 1/Activity versus 1/[protein concentration] was plotted.

3. Matrix metalloproteinase −2 (MMP-2) inhibition

Assays were performed to ascertain whether the dual protease inhibitor is capable to inhibit MMP-2 activity. To this end, an enzyme activity substrate assays with different concentrations of the dual protease inhibitor was employed. There was near complete inhibition of MMP-2 by the dual protease inhibitor at a concentration of 0.5 μg/μl (Figure 4A). The dual inhibtor inhibits MMP-2 activity similarly as the single MMP-2 inhibitor APP-IP-ELP across various concentrations (Figure 4B). As expected the single NE inhibitor PMPD2-ELP did not inhibit MMP-2 over various concnetrations (Supplementary Figure 3), indicating that PMPD2 portion in the dual protease inhibitor is not responsible for blocking the majority of the MMP-2 acitvity. In Figure 4C, a Lineweaver–Burk plot of 1/activity versus 1/[protein], it can be observed that both the dual protease inhibitor and APP-IP-ELP increase their inhibitory activity against MMP-2 as concentration is increased. While PMPD2-ELP contains a near zero slope over various protein concentrations indicating insufficient activity against MMP-2 (Figure 4C). To quantify the inhibition the IC50 of the dual inhibitor was calculated and compared with the single inhibitor. It was learned that the dual inhibitor had an IC50 of 0.04 μg/μl, while the single inhibitor APP-IP-ELP had an IC50 of 0.05 μg/μl. Moreover, the MMP-2 inhibitory activity PMPD2-ELP leveled off at 20% inhibition at the largest tested concentration indicating that it is a poor inhibitor of MMP-2 and is not the main contributor to the MMP-2 inhibition exhibited by the dual inhibitor.

Figure 4. The dual protease inhibitor inhibits Matrix-metalloproteinase-2 (MMP-2) like MMP2 inhibitor, APP-IP-ELP.

A kinetic colorimetric MMP-2 inhibition assay was performed to evaluate inhibitory activity of various concentrations of A) PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP, B) APP-IP-ELP. C) From the kinetic inhibition assays, slope (activity) was calculated for each protein concentration and 1/Activity versus 1/[protein concentration] was plotted.

4. Cell toxicity

The dual protease inhibitor was incubated with cells to evaluate its possible toxic effects. There was no apparent toxicity at a range of concentrations of the dual protease inhibitor (Figure 5). For concentrations as high as 0.5 mg/ml, no toxicity of the protease inhibitor was observed. This confirms that the inhibtor is nontoxic at its active concentrations.

Figure 5. The dual protease inhibitor is not toxic to cells at its active concentrations.

A549 cells were treated with 0.05, 0.2, and 0.5 μg PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP per μl of cell culture media and a control consisting of cells with no protein treatment. A cell viability Hoechst assay was performed and the OD values for each experimental group was normalized to the control to evaluate % viability.

5. Protection from proteolytic degradation of rhKGF

Recently, it has described that heterogeneous ELP based nanoparticles protect growth factors from degradation mediated by neutrophil elastase12. However, chronic wounds also have high MMP in addition to HNE. Thus, nanoparticles were assembled containing the growth factor (Keratinocyte Growth Factor, KGF) and the dual protease inhibitor. The NPs were incubated in both HNE and MMP-2 to evaluate protection of the growth factor in the NPs from degradation mediated by both proteases. It was observed that HNE degraded KGF completely in as soon as 4 hours (Figure 6, lanes 3–5). However, nanoparticles containing the dual protease inhibitor protected the KGF from degradation (Figure 6, lanes 6–8). Similarly, MMP2 degraded the growth factor by 24 hours (Figure 6, lanes 9–11) but the NPs protected the growth factor from degradation (Figure 6, lanes 12–14). The results confirm that the dual protease inhibitor protects the growth factor from both proteases thus eliminating the need of using two different protease inhibitors targeting each of the protease.

Figure 6. The dual protease inhibitor protects Keratinocyte Growth Factor (rhKGF) from both NE and MMP-2.

rhKGF was incubated with either purified HNE or MMP-2 for 2,4, or 24 hours. Proper experimental controls were established by incubating KGF with HNE or MMP-2 without the dual protease inhibitor, PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP, to display the degree of KGF degradation. At the indicated time points samples were taken and subjected to western blots using an antibody specific to human KGF to evaluate the effectiveness of the dual protease inhibitor in protecting KGF from proteolytic degradation.

DISCUSSION

The high protease environment in chronic wounds presents a significant challenge in the development of therapeutics for healing. The imbalance of proteases not only results in the disruption of balance between ECM degradation and remodeling8–11, but also in the loss of other beneficial proteins such as growth factors that initiate the healing process. This further confounds treatment approaches as growth factor supplementation is considered beneficial for chronic wound treatment is rendered ineffective because of the proteases. Hence, protease inhibitors play a crucial role for the development of a successful therapy for chronic wound healing. However, this strategy is challenging due to the presence of many unique proteases present in chronic wounds. Described here is the development of a dual protease inhibitor PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP, which consists of peptide inhibitor domains PMPD2 (HNE inhibitor) and APP-IP (MMP inhibitor). The hybrid peptide inhibitor successfully inhibited two commonly found proteases in chronic wounds namely HNE and MMP thereby eliminating the need of two individual inhibitors of the two proteases.

The IC-50 of the dual inhibitor was comparable with the IC50 of the individual inhibitors PMPD2-ELP (For HNE) and APP-IP-ELP (For MMP). This shows that the two peptide inhibitor domains do not interfere with each other’s activity. Furthermore, the specificity of the domains is maintained in the fusion as PMPD2 did not significantly inhibit MMP-2 and APP-IP did not significantly inhibit HNE. These data indicate that the hybrid fusion protein is useful as it inhibits two proteases. Therefore, PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP is a single protein designed to have broad spectrum effect, just as heterogeneously mixing the two single inhibitory peptides would accomplish the same goal. However, heterogeneously mixing the two peptides would classify the treatment as a drug combination to accomplish broad-spectrum activity. The hybrid protein, PMPD2-ELP-APP-IP, can be classified as a single treatment, but with two unique functions. Avoidance of heterogeneous mixing of ELP-fusion proteins eliminates questions of drug interactions and allows for predictability of phase transitioning properties and uniformity of self-assembly that governs sustained release. Though one may think the utilization of multiple inhibitors rather than one multi-functional inhibitor is more desirable when a 1:1 mixing ratio is not the case. But delivering a single molecule is more desirable compared to delivering two inhibitors as there could be issues related to hinderance from co-localization, concentration, and undesirable interactions with each other.

The dual protease inhibitor may be a candidate to disrupt the imbalance between ECM degradation and remodeling as its fusion with an ELP provides useful as a drug delivery platform for biologically active peptides. Proving this concept leads to the possible capability of creating additional proteins with more biologically active regions to target two or more proteases that are upregulated in chronic wounds by adding additional inhibitory peptides to the amino acid sequence. In contrast, a current treatment to inhibit proteases such as NE are oleic acid and albumin mixtures28. Oleic acid and albumin treatments consist of a heterogenous mixture of two components, where this mixture is non-specific. In contrast, PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP is a single molecule with the capabilities to inhibit specific proteases without the mixing of multiple components and provides the potential to add additional inhibitors with specificity to unique proteases leading to a therapy that can easily be tailored to a unique chronic wound environment.

MMP’s are key proteases in the destruction of ECM components10,11. However, MMP’s have been shown to destroy growth factors that contain the key role in restoring the cellular components of wounded tissue2. This study shows that PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP hybrid fusion protein effectively interrupts the process of keratinocyte growth factor degradation by both MMP-2 and HNE. The latter links this dual inhibitor to the potential application of using this broad-spectrum inhibitor as a growth factor protector in chronic wounds, which broadens its role as not only a control of ECM degradation but also a regulator of tissue reconstruction. Furthermore, chronic wounds display poor vasculature leading to an impaired immune response. MMP-2 is as large contributor to vasculature break down29. Using a self-assembling protein such as PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP as a thermoresponsive inhibitor of MMP-2 allows for point specific application establishing vasculature rich environment for wound closure. Ultimately, point specific therapies eliminates the need to for a systemic treatment such as an antibiotic, which could bring about undesirable affects in other areas of the body and contain delivery failure to the wound bed in the presence of poor vascularization. Following the rhetoric of poor vasculature, chronic wounds are susceptible to infections due to a lack in the ability of the tissue to undergo the chain of immune response that is proper for wound cleanout and closure, which will lead to further tissue destruction as the immune cells that are present overreact to clear the wound of infection30. To support the latter, it is understood that neutrophil elastase is secreted by neutrophils in the presents of bacterial infection due the antimicrobial properties of HNE31. However, due to neutrophil elastase’s ability to degrade ECM, its release during an infection will cause immense as the HNE is oversecreted and not properly cleared by the tissue. PMPD2-L10FLAG-APP-IP can both inhibit MMP-2 and HNE ultimately reestablishing an environment where growth factors can act to restore proper tissue construction and vascularization.

The fusion of both inhibitor domains to an ELP retained the biological activity of both domains as well as the phase transitioning properties of ELPs. This was not surprising as previous work from this lab and others have shown the development of several chimeric ELP fusion proteins that retain the biological activity of the fused domain as well as the physical phase transitioning property of ELPs16,24,27. However, this study is different from all previous studies involving chimeric ELP fusions since here there are two domains fused to create a single molecule with two roles. Not only was the dual fusion thermoresponsive like ELPs but also had inhibiting activities towards two different proteases. The recombinant nature of ELP sequences allows us to create these complex sequences seamlessly and the thermoresponsive properties of ELPs leads to rapid purification. It can be brought to question if an ELP is needed to create novel proteins that contain multiple domains for multiple therapeutic actions. However, the ELP may allow for domain separation, where without, it may be observed that domains with various structures and charges would interact in undesirable ways if not separated by an ELP. This sheds light on further studies that can be established to explore the ability to construct proteins with more than two biologically active domains on one or more ELP backbone. As seen in this study, with the dual fusion of PMPD2 and APPIP fused around a centered ELP, neither domain’s inhibitory activity was negatively affected by the other, while the ELP’s remain thermoresponsive after addition of a biologically active domains, making it a fusion partner that is desirable for simple purification and a drug delivery mechanism that self-assembles into stable nanoparticles and extend the life of small biologically active peptides that would otherwise be diffusively unstable32. As mentioned, in chronic wounds there exists a threat to proteolytic degradation of growth factors and the application of this study sheds light on the ability to deliver protease inhibitors and protect growth factors from degradation. Koria et al. has shown that a fusion protein, KGF-ELP, remains biologically active after ELP fusion24, which contributes to a proof of concept that similar multifunctional proteins could be constructed to contain a protease inhibitor and a growth factor, where the protease inhibitor may effectively protect the growth factor while existing on the same protein platform ultimately giving a single protein the power to act as a designer therapeutic for a formulated result. The opportunities are endless in the realm of wound healing and point specific treatments. It has also been shown that antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) contain synergy33 and some antimicrobial domains can cause disruption of bacterial biofilm production when used with a ELP based material coating34. This further supports the combining of biologically active domains around an ELP ultimately providing broad spectrum treatments and activity amplification by using a similar construction as described in this study to keep two peptides with synergy or differing activity local to one another to increase therapeutic power and coverage.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by NIH grant R21AR068013 (PK)

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Hasselt JGC, Iyengar R. Systems Pharmacology: Defining the Interactions of Drug Combinations. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2019;59:21–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultz GS, Wysocki A. Interactions between extracellular matrix and growth factors in wound healing. Wound Repair Regen. 2009;17(2):153–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Afonso AC, Oliveira D, Saavedra MJ, Borges A, Simões M. Biofilms in Diabetic Foot Ulcers: Impact, Risk Factors and Control Strategies. International journal of molecular sciences. 2021;22(15):8278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.González-Pérez F, Ibáñez-Fonseca A, Alonso M, Rodríguez-Cabello JC. Combining tunable proteolytic sequences and a VEGF-mimetic peptide for the spatiotemporal control of angiogenesis within Elastin-Like Recombinamer scaffolds. Acta Biomaterialia. 2021;130:149–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker EA, Leaper DJ. Proteinases, their inhibitors, and cytokine profiles in acute wound fluid. Wound Repair Regen. 2000;8(5):392–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarty SM, Percival SL. Proteases and Delayed Wound Healing. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2013;2(8):438–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okonkwo UA, DiPietro LA. Diabetes and Wound Angiogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han G, Ceilley R. Chronic Wound Healing: A Review of Current Management and Treatments. Adv Ther. 2017;34(3):599–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutcliffe JES, Thrasivoulou C, Serena TE, et al. Changes in the extracellular matrix surrounding human chronic wounds revealed by 2-photon imaging: second harmonic imaging of chronic wound extracellular matrix. International wound journal. 2017;14(6):1225–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Armstrong DG, Jude EB. The role of matrix metalloproteinases in wound healing. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2002;92(1):12–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bergant Suhodolčan A, Luzar B, Kecelj Leskovec N. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-1 and MMP-2, but not COX-2 serve as additional predictors for chronic venous ulcer healing. Wound repair and regeneration. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boeringer T, Gould LJ, Koria P. Protease-Resistant Growth Factor Formulations for the Healing of Chronic Wounds. Advances in Wound Care (2162–1918). 2020;9(11):612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferreira AV, Perelshtein I, Perkas N, Gedanken A, Cunha J, Cavaco-Paulo A. Detection of human neutrophil elastase (HNE) on wound dressings as marker of inflammation. Applied microbiology and biotechnology. 2017;101(4):1443–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Serena TE, Cullen BM, Bayliff SW, et al. Defining a new diagnostic assessment parameter for wound care: Elevated protease activity, an indicator of nonhealing, for targeted protease-modulating treatment. Wound Repair Regen. 2016;24(3):589–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heredero M, Garrigues S, Gandía M, Marcos JF, Manzanares P. Rational Design and Biotechnological Production of Novel AfpB-PAF26 Chimeric Antifungal Proteins. Microorganisms. 2018;6(4). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy B, Yuan Y, Koria P. Elastin-like-polypeptide based fusion proteins for osteogenic factor delivery in bone healing. Biotechnol Prog. 2016;32(4):1029–1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhorkar I, Dhoble AS. Advances in the synthesis and application of self-assembling biomaterials. Progress in Biophysics and Molecular Biology. 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Urry DW. Physical Chemistry of Biological Free Energy Transduction As Demonstrated by Elastic Protein-Based Polymers. The Journal of Physical Chemistry - Part B. 1997;101(51):11007–11028. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Genetically Encoded Synthesis of Protein-Based Polymers with Precisely Specified Molecular Weight and Sequence by Recursive Directional Ligation: Examples from the Elastin-like Polypeptide System. Biomacromolecules. 2002;3(2):357–367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Meyer DE, Chilkoti A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally responsive polypeptides. In. United States1999:1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnson T, Koria P. Expression and Purification of Neurotrophin-Elastin-Like Peptide Fusion Proteins for Neural Regeneration. BioDrugs : clinical immunotherapeutics, biopharmaceuticals and gene therapy. 2016;30(2):117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Leonard A, Koria P. Growth factor functionalized biomaterial for drug delivery and tissue regeneration. J Bioact Compat Polym. 2017;32(6):568–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qin J, Luo T, Kiick KL. Self-Assembly of Stable Nanoscale Platelets from Designed Elastin-like Peptide–Collagen-like Peptide Bioconjugates. Biomacromolecules. 2019;20(4):1514–1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koria P, Yagi H, Kitagawa Y, et al. Self-assembling elastin-like peptides growth factor chimeric nanoparticles for the treatment of chronic wounds. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(3):1034–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vasconcelos A, Azoia NG, Carvalho AC, Gomes AC, Güebitz G, Cavaco-Paulo A. Tailoring elastase inhibition with synthetic peptides. European Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;666(1):53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ndinguri MW, Bhowmick M, Tokmina-Roszyk D, Robichaud TK, Fields GB. Peptide-Based Selective Inhibitors of Matrix Metalloproteinase-Mediated Activities. Molecules. 2012;17(12):14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Monfort DA, Koria P. Recombinant elastin-based nanoparticles for targeted gene therapy. Gene Therapy. 2017;24(10):610–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smeets R, Ulrich D, Unglaub F, Wöltje M, Pallua N. Effect of oxidised regenerated cellulose/collagen matrix on proteases in wound exudate of patients with chronic venous ulceration. Int Wound J. 2008;5(2):195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.van Hinsbergh VW, Collen A, Koolwijk P. Role of fibrin matrix in angiogenesis. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;936:426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(7):885–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cole AM, Shi J, Ceccarelli A, Kim YH, Park A, Ganz T. Inhibition of neutrophil elastase prevents cathelicidin activation and impairs clearance of bacteria from wounds. Blood. 2001;97(1):297–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Khademhosseini A, Kobayashi H, Tabata Y. Enhanced angiogenesis through controlled release of basic fibroblast growth factor from peptide amphiphile for tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 2006;27(34):5836–5844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu G, Baeder DY, Regoes RR, Rolff J. Combination Effects of Antimicrobial Peptides. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60(3):1717–1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atefyekta S, Pihl M, Lindsay C, Heilshorn SC, Andersson M. Antibiofilm elastin-like polypeptide coatings: functionality, stability, and selectivity. Acta Biomater. 2019;83:245–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.