Abstract

The recent discovery that collision of ribosomes triggers quality control and stress responses in eukaryotes has shifted the perspective of the field. Collided eukaryotic ribosomes adopt a unique structure, acting as a ubiquitin signaling platform for various response factors. While several of the signals that determine which downstream pathways are activated have been uncovered, we are only beginning to learn how the specificity for the activation of each process is achieved during collisions. This review will summarize those findings and how ribosome-associated factors act as molecular sentinels, linking aberrations in translation to the overall cellular state. Insights into how cells respond to ribosome-collision events will provide greater understanding of the role of the ribosome in the maintenance of cellular homeostasis.

Keywords: ribosome, collisions, mRNA surveillance, quality control, integrated stress response, signaling

Ribosome collisions are inevitable

In all organisms, the expression and maintenance of the genetic information relies on molecular machines that traverse linear nucleic acid templates for long distances. Oftentimes, multiple machines share the same template and even move in opposing trajectories. To avoid conflicts, organisms have evolved a host of mechanisms to coordinate the activity of its various machines [1]. However, a key challenge for the organism is how to respond when machines become stuck and run into one another. Collisions must be promptly resolved to restore proper gene expression and return to homeostasis. This is evident during replication and transcription, during which collisions can occur between replisomes (see Glossary) and transcribing RNA polymerases [1]. Such events can be highly deleterious, resulting in genomic instability and even cell death [1]. However, organisms have also taken advantage of these events to monitor genomic integrity and maintain the fidelity of the genomic information. Indeed, signaling as a result of disruptions in the movement of DNA and RNA polymerases is utilized for various DNA repair pathways [1].

Translation of messenger RNA (mRNA) on the other hand, only involves ribosomes that move in the same direction – from the 5’ to the 3’ end of the mRNA. Even so, the stochastic nature of the translational process results in ribosomes sometimes slowing down and running into one another [2,3]. Slowed or stopped translation is also used as a regulatory mechanism for frameshifting and folding [4,5]. Indeed, modeling studies in bacteria found that protein output could not be explained without a collision-centric model [3,6]. Comprehensive looks at ribosome occupancy in yeast and human cells have also found collisions to be widespread [7,8]. These naturally occurring stalls and collisions are not the focus of this review. Instead, we focus on stalling and collisions arising from defects in the mRNA. These defects, whether due to misprocessing or chemical damage (Box 1), can cause the ribosome to arrest and lead to non-productive queues of stalled ribosomes [9]. It was known that, similar to how polymerases act as sensors of DNA damage, such events led to the activation of ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) and mRNA-surveillance pathways in eukaryotes [10–12].

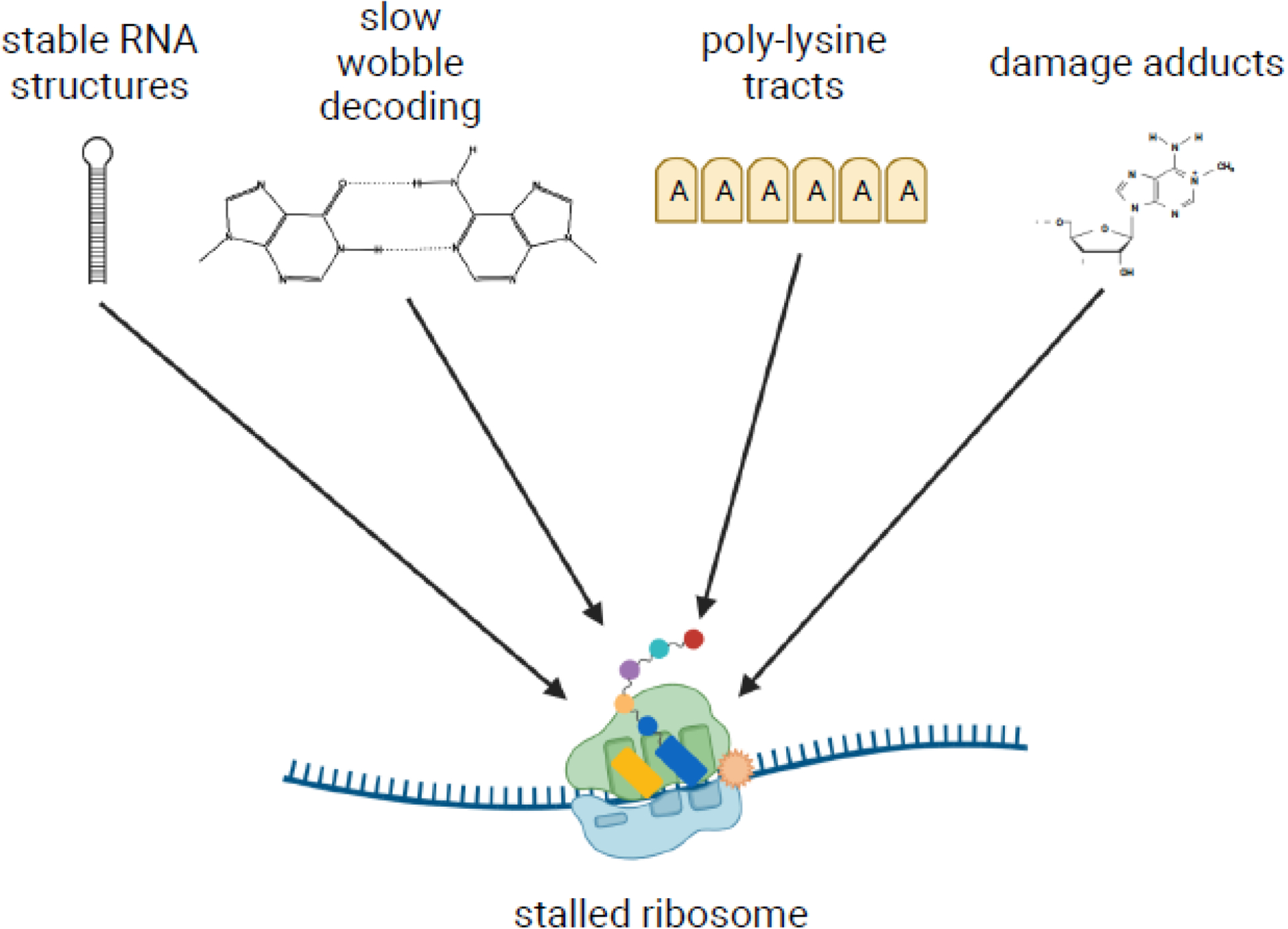

Box 1. Unusual mRNA features stall the ribosome.

The ribosome is a fast molecular machine, in eukaryotes moving at an average speed of approximately five codons per second on an mRNA [87]. However, several roadblocks can prevent the ribosome from moving along the mRNA template, causing it to stall. One such obstacle is stable secondary structures in the mRNA. In the work by Doma and Parker, the authors found that reporters containing stem loops stalled the ribosome and activated the No-Go Decay (NGD) pathway [12]. Likewise, inhibitory codon pairs also stall ribosomes in yeast. For example, in the case of CGA tandem repeats, stalling occurs due to slow decoding of the CGA codon by its cognate tRNAArg(ICG), which features an atypical inosine-adenosine wobble pairing [22]. The presence of multiple lysine AAA codons also leads to ribosome slippage and stalling, which is thought to occur due to interactions between the polyA sequence and the 18S rRNA, as well as interactions between the encoded poly-lysine residues and the exit tunnel of the large subunit [29,88,89]. Damage to the nucleotides that comprise the mRNA can also induce stalling. Alkylating and oxidizing agents modify the nucleobases of mRNAs, resulting in adducts such as 1-methyl-adenosine and 8-oxoguanosine, which inhibit tRNA selection by the ribosome and cause it to arrest [74,75,90].

However, it remained unclear how eukaryotic cells recognized stalled ribosomes to trigger destruction of the defective transcript and recover the valuable ribosomes. It was not until recently that we came to realize that additional ribosomes colliding into a stalled ribosome was the key event for initiating these pathways [13]. Subsequent structural studies have uncovered that collided eukaryotic ribosomes adopt a unique structure that can be readily distinguished from normal ribosomes [14,15]. The ubiquitin signaling that occurs on the collided ribosomes are the basis for various downstream quality-control processes. In this review, we will discuss the role of this ubiquitin signaling and its consequences for the ribosome. Downstream processes will be briefly discussed but are more extensively covered in several recent reviews (see [16–18]). Furthermore, signaling on collided ribosomes appears to have consequences beyond that of just ribosome rescue and mRNA quality control, including sensing environmental changes to trigger stress responses and cell-fate decisions [19,20]. We will delve into how cells might monitor the global collision frequency to activate the most appropriate response pathway.

Ribosome collision leads to ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins

Ribosomal stalling and collisions seem to be a feature of the eukaryotic transcriptome [7,8]. Naturally occurring stalls arising from certain transcript elements appear to be dealt with by the translation factor eIF5A [7] and typically result in resumption of translation. In contrast, upon detection of non-productive stalls which block continued translation, three critical steps must occur in order to prevent accumulation of toxic peptide products: ribosome dissociation and rescue, decay of the defective mRNA, and degradation of the incomplete peptide (for reviews, see [16–18]). The discovery in yeast that RQC and the mRNA surveillance pathway of No-Go Decay (NGD) were dependent on the presence of the E3 ligase Hel2 [13,21–26] suggested that the factor is the first to respond to ribosome stalling. The factor harbors a RING-finger ubiquitin-ligase domain and was initially characterized for its role in ubiquitination of excess histones [27]. Subsequent studies determined that Hel2 ubiquitinated ribosomal proteins uS3 and uS10 in response to collisions [13,15,24]. At the same time, several groups identified ZNF598 as the mammalian homologue of Hel2 and found it to play a similar role in resolving ribosome stalls [14,28–30].

In a yeast cell, the number of Hel2 molecules has been estimated to be ~2000 [31], about 1% of the number of ribosomes [32]. As a result, efficient ribosome rescue requires the factor to display high specificity for stalled ribosomes over elongating ones. Structural studies revealed that stalled ribosomes adopt distinct conformations relative to translating ones, which, in principle, can rationalize how the factor recognizes stalled ribosomes specifically [24]. A number of clues, however, argued for a different mode of recognition, including the observation that stalling is used as a regulatory mechanism for several processes such as protein targeting and programmed frameshifting [4,5]. Furthermore, stalled ribosomes adopt different conformations depending on the nature of the stall [16,33], making it difficult to reconcile how one factor can recognize all these conformations. So how does Hel2/ZNF598 bind ribosomes stalled on problematic mRNAs only? An important observation in uncovering the answer was the finding that robust NGD requires the stall to occur well downstream of the start codon and that cleavage of the aberrant mRNA can be mapped further upstream of the initial stalling site [13,34,35]. This suggested that the signal for triggering NGD was the collision and subsequent pileup of ribosomes (Figure 1A). This model was further bolstered by the observation that Hel2-mediated ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins was found to be activated in response to ribosome collisions [13,24]. For instance, even though addition of compounds such as cycloheximide and emetine to high concentrations does not result in activation of Hel2/ZNF598, their addition to intermediate concentrations – during which partial stalling occurs – is accompanied by ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins [13,14].

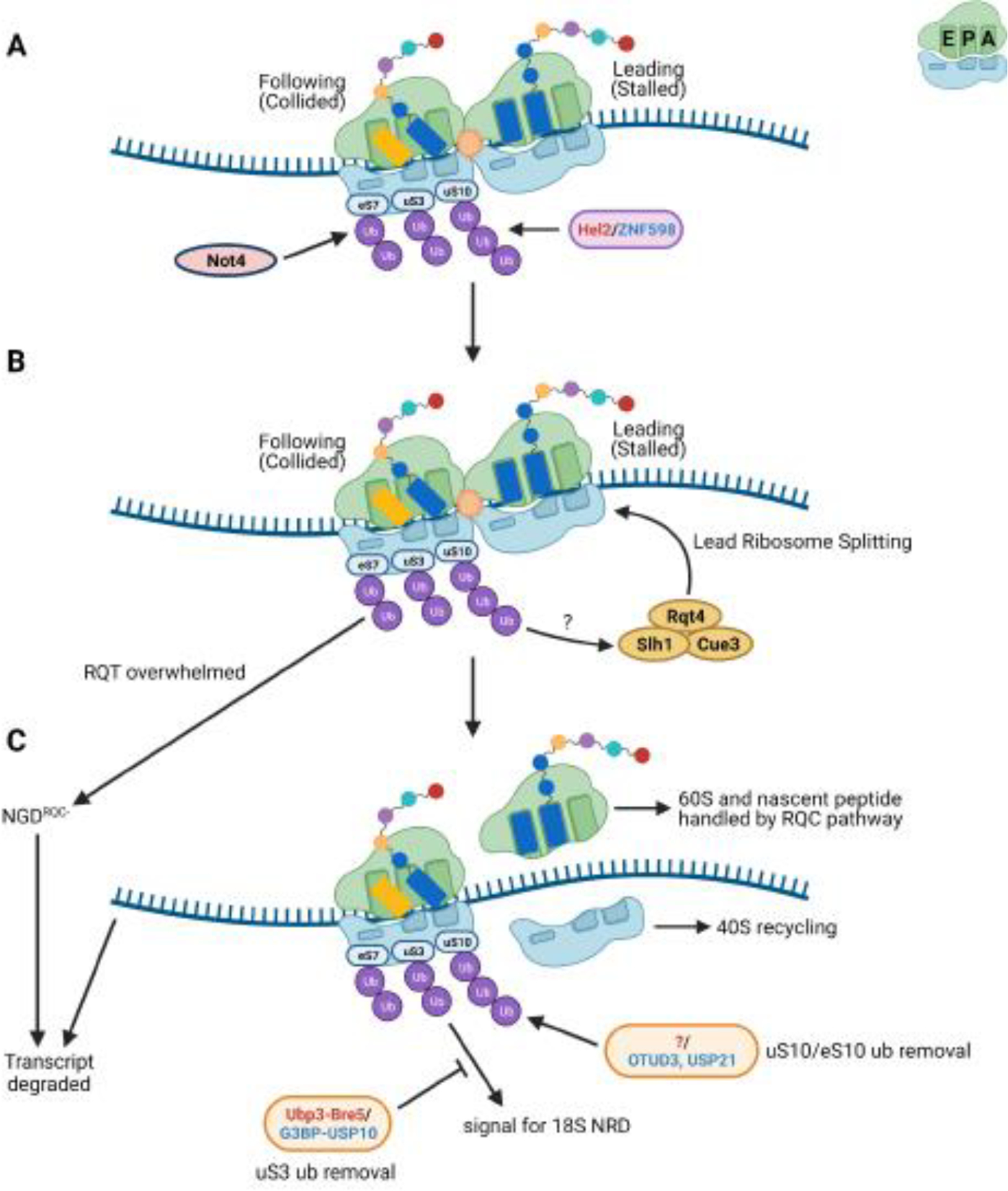

Figure 1. Signaling on collided ribosomes and its impact on ribosome fate.

Small cartoon depicting the A, P, and E sites is in the top right of the figure. (A) Ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins uS10 and uS3 by Hel2 in yeast, and eS10, uS10, and uS3 by ZNF598 in mammals, occurs on stable collided ribosome structures. In yeast, eS7 is ubiquitinated by Not4 via an unknown mechanism and polyubiquitinated by Hel2 during stalling. Which ribosomes within the collision units are ubiquitinated remains unclear. Given that Hel2/ZNF598 has been proposed to recognize the rotated state of collided ribosomes, one potential model is that only the collided ribosomes are ubiquitinated, enabling distinction of the stalled ribosome. However, uS3 and eS7 may show different signaling patterns. For simplicity, only the collided ribosome is depicted as ubiquitinated. (B) The stalled ribosome is split by the ribosome-quality control trigger (RQT) complex but the purpose of the ubiquitin marks in this process remains unknown. In the event the RQT complex is overwhelmed, polyubiquitinated eS7 acts as a signal for a secondary mRNA decay mechanism termed NGDRQC-. (C) Once split, the nascent peptide-bound 60S is handled by the RQC pathway and the 40S is presumably returned to the free 40S pool. The transcript is degraded by downstream mRNA decay pathways. eS10 and uS10 ubiquitin marks can be removed by the mammalian de-ubiquitinases OTUD3 and USP21. The homologous yeast deubiquitinase is yet to be identified (denoted by “?” in the figure). A yet undetermined uS3 ubiquitin signal triggers 18S NRD but can be opposed by the action of the de-ubiquitination complexes Ubp3-Bre5 in yeast or G3BP-USP10 in mammals. Names of the factors in red/blue denote the yeast and mammalian factor, respectively.

Although the idea of collided ribosomes acting as the master signal for downstream ribosome rescue pathways was an appealing one, the mechanics of how this might occur was not immediately obvious. In a series of structural studies, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) analysis of the minimal collision unit of two ribosomes, or disome, revealed that collided ribosomes adopt a unique structure [14,15]. In the disome structure, the lead ribosome is stabilized in a post-translocation state, with an empty A site but occupied P and E sites, while the collided ribosome adopts a rotated state with hybrid A/P and P/E-transfer RNAs (tRNAs; Figure 1A). The conformations of the two ribosomes result in various contacts being made between the ribosomal 40S subunits. The key interactions appear to be between RACK1 and uS3 of the stalled ribosome with RACK1 and uS10 of the collided ribosome in yeast, and between RACK1 of the stalled ribosome with eS10, uS10, and uS3 of the collided ribosome in mammals. It is thought that the interface between the collided 40S subunits is recognized by Hel2/ZNF598 [14,15]. However, a structure of the factor in complex with ribosomes is yet to be determined.

Biochemical reconstitution of Hel2/ZNF598-mediated ubiquitination provided further support for in vivo observations; disomes are sufficient for activity but higher-order structures of collided ribosomes – trisomes or longer polyribosome chains – appear to be more efficiently ubiquitinated [14,36]. A recent cryo-EM analysis of trisomes on the natural stalling sequence of the yeast SDD1 mRNA suggests that this may be due to the fact that the second and third ribosome form an interface similar to the one observed in disomes [36]. Since the second and third ribosome form the recognition interface in the trisome structure, subsequently collided ribosomes in longer polyribosome chains may also generate more of these interfaces [36]. If the 40S-40S interfaces are indeed recognized by Hel2/ZNF598, this would provide a structural basis for the observed increase in ubiquitination efficiency.

One important note is it remains unknown which ribosomes in a pileup are ubiquitinated. If Hel2/ZNF598 is indeed recognizing the rotated state or unique interfaces of collided ribosomes, it is possible that only the collided ribosomes are ubiquitinated, leaving the stalled ribosome unmarked. This would serve to distinguish the lead ribosome and could also further explain how trisomes show more efficient ubiquitination compared to disomes. However, other ubiquitin signals, discussed later in this review, may exhibit alternative patterns.

The role of ribosomal protein-ubiquitination in dissociation of the stalled ribosome

Upon ubiquitination, ribosomes undergo rescue and recycling of their subunits. For disassembly of the stalled ribosome, recent work suggests that after ubiquitination by Hel2/ZNF598, the lead ribosome of a pileup is disassembled by the Ribosome-Quality Control Trigger (RQT) complex (Figure 1B) [36,37]. The complex is composed of the helicase Slh1, Cue3/Rqt3, and Rqt4 in yeast, and its homologs ASCC3, ASCC2, and TRIP4, respectively, in mammals. The mammalian complex also contains the factor ASCC1 [37,38], whose yeast homolog is yet to be identified. Disassembly of the lead ribosome is dependent on the helicase action of Slh1/ASCC3 [36–38], after which the peptidyl-tRNA-bound 60S subunit is handled by the RQC pathway for destruction of the nascent peptide and recycling of the 60S [23,39]. The 40S subunit on the other hand, is presumably returned to the free 40S pool.

While it is now clear that ubiquitination is needed for rescue of stalled ribosomes, how the ribosome rescue machinery utilizes the ubiquitin marks to properly target the stalled ribosome remains undetermined. Cue3 of the RQT complex possesses a CUE domain [24] (ubiquitin-binding domain) which readily provides a molecular rationale for how the complex can associate with ubiquitinated ribosomes. However, deletion of Cue3 does not completely abolish RQC, suggesting that Slh1 can still correctly target the stalled ribosome, albeit at reduced efficiencies [24,26]. It also appears that ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins is not necessary for Slh1/ASCC3 association with disomes, even though ubiquitination of uS10/eS10 is required for their downstream function in ribosome disassembly [36–38]. Complicating the matter further is the unknown ubiquitination status of each ribosome in the pileup. If the lead ribosome is indeed unmarked, this would provide a mechanism for how the stalled ribosome is recognized, but not the mechanism by which Slh1/ASCC3 is targeted to said ribosome. In this model, it is feasible that Slh1/ASCC3 recognizes the stalled ribosome in a collided-ribosome context.

To complete the rescue process, ubiquitin marks must be removed such that previously-collided ribosomes can later be properly recognized in the event of another stall (Figure 1C). In humans, the de-ubiquitinating enzymes OTUD3 and USP21 can remove ubiquitin placed by ZNF598 [40]. However, significant de-ubiquitination after UV-induced ubiquitination of uS10/eS10 required several hours [40]. While it is possible that de-ubiquitination after UV damage does not reflect more basal conditions, as a large number of stalls might overwhelm the deubiquitinases, if de-ubiquitination is indeed a slow process, it is difficult to imagine that these enzymes can act to remove ubiquitin before a ribosome stalls again. Also, the model does not explain how these enzymes would be specifically targeted to collided ribosomes or at what stage in the rescue pathway they act. It is abundantly clear that more work is needed to understand how the addition and removal of ubiquitin during and after stalling are coordinated to maintain ribosome stasis.

eS7 ubiquitination as a pathway for alternative NGD and mRNA degradation

In yeast, the small ribosomal protein eS7 is ubiquitinated in addition to uS10 [15,41]. Unlike uS10, which is a target of Hel2, eS7 is initially monoubiquitinated by Not4 [42] (Figure 1A), a factor that has multiple functions (for review see [43]). How and when Not4 targets ribosomes for eS7 monoubiquitination is not clear, but the addition of K63-linked polyubiquitination on monoubiquitinated eS7 by Hel2 occurs during stalling [15] (Figure 1A). eS7 polyubiquitination seems to operate as a signal for a secondary mechanism for degrading the aberrant mRNA termed NGDRQC- (Figure 1C), in which decay is decoupled from RQC. This mechanism is characterized by an initial cleavage of the mRNA well upstream of the stall sequence, relative to cleavages observed during normal RQC-coupled NGD [15]. While NGDRQC- appears to be only a minor contributor to NGD under normal conditions, it becomes increasingly active when uS10 ubiquitination is inhibited or Slh1 is absent. Therefore, it has been proposed that under normal conditions, ubiquitination of uS10 is required for Slh1 activity in ribosome disassembly, which in turn is required for NGD. When Slh1 is overwhelmed, eS7 polyubiquitination serves as a secondary signal for mRNA degradation [15], possibly by the Ccr4-Not complex.

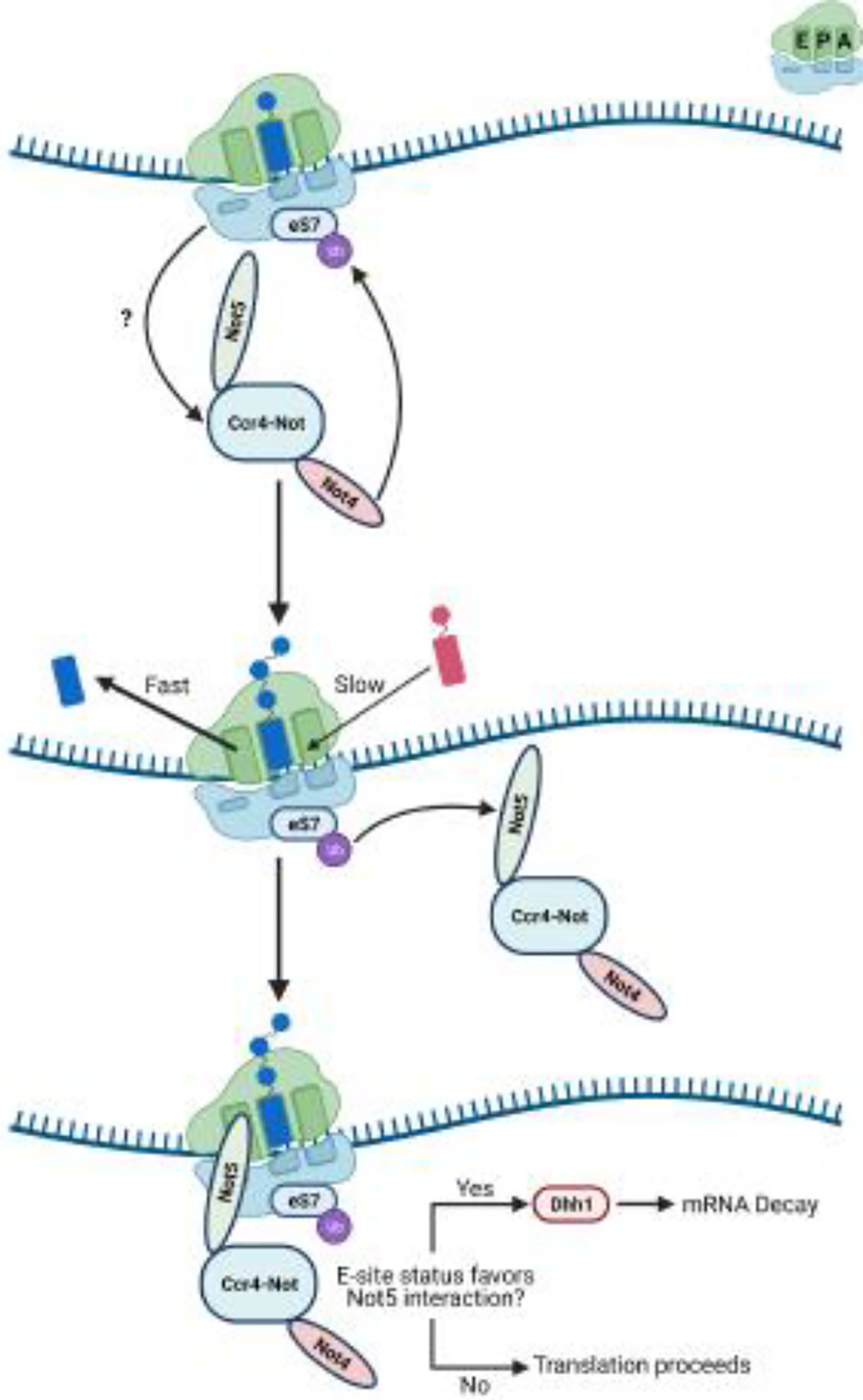

Interestingly, in addition to its role in quality control of aberrant mRNA, eS7 monoubiquitination appears to play an additional role in decay of normal mRNAs (Figure 2) [41]. Emerging evidence suggests that mRNA decay in eukaryotes is intimately coupled to ribosome speed, whereby slowed translation is a determinant for increased mRNA turnover [44]. In a recent study, Buschauer and Matsuo et al. found that eS7 ubiquitination is required to recruit the Ccr4-Not deadenylase complex to slowly translating ribosomes [41]. Not5 is a core subunit of Ccr4-Not that binds to the ribosome and inspects the occupancy of the E site as a proxy for ribosome speed; an empty E site indicates that A-site decoding is slow and in turn results in Not5-mediated recruitment of the DEAD-box helicase Dhh1 for decapping and decay (Figure 2) [41].

Figure 2. Model for Not5-mediated mRNA decay on the ribosome.

Small cartoon depicting the A, P, and E sites is in the top right of the figure. In yeast, Not5 is anchored to the ribosome via Not4-mediated eS7 ubiquitination. When and how Not4 targets ribosome for eS7 ubiquitination is not completely understood. Once on the ribosome, Not5 monitors E-site occupancy as a proxy for A-site decoding efficiency. When E-site occupancy is low, Not5 recruits the DEAD-box helicase Dhh1 to initiate mRNA decay.

How eS7 ubiquitination can be used for two seemingly distinct pathways of mRNA decay is not completely understood. It is possible, however, that the level of eS7 polyubiquitination is used as a measure of how much ribosome speed is reduced. The more linked-ubiquitin chains are added, the more likely the mRNA is defective. Alternatively, a Not5-dependent decay pathway for defective mRNAs would add redundancy and provide a means to initiate decay for stalls near the start codon, which do not robustly activate NGD. To add more complexity to the interplay between these processes, activation of the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) also leads to Not4-mediated ubiquitination of eS7 [45]. It is entirely possible that the signal here is not the same as observed in collision or slowed translation, as activation of UPR can also lead to ubiquitination of uS5 in mammals [46]. In addition, it is unknown how ribosomes are rescued in these pathways. More work is needed to determine how Not4 and Not5 are participating in the resolution of stalls, mRNA decay, and stress responses.

uS3 ubiquitination as a marker for ribosome competency

Thus far, we have only discussed stalling in the context of defective mRNAs, but in principle, defects in the ribosome would also lead to similar consequences. It is important for cells to correctly identify the source of the defect to degrade the appropriate molecule. In eukaryotes, defective ribosomes are degraded through a process termed non-functional ribosomal RNA (rRNA) decay (NRD) [47]. Briefly, the process by which aberrant ribosomes are recognized and targeted for degradation critically depends on the position of the defect within the rRNA species. 25S NRD is responsible for degrading defective large subunits while 18S NRD is responsible for degrading defective small subunits. Intriguingly, many of the factors involved during ribosome collisions are also involved in 18S NRD [48,49], suggesting interplay between the two processes. In contrast, 25S NRD shares few such factors [50].

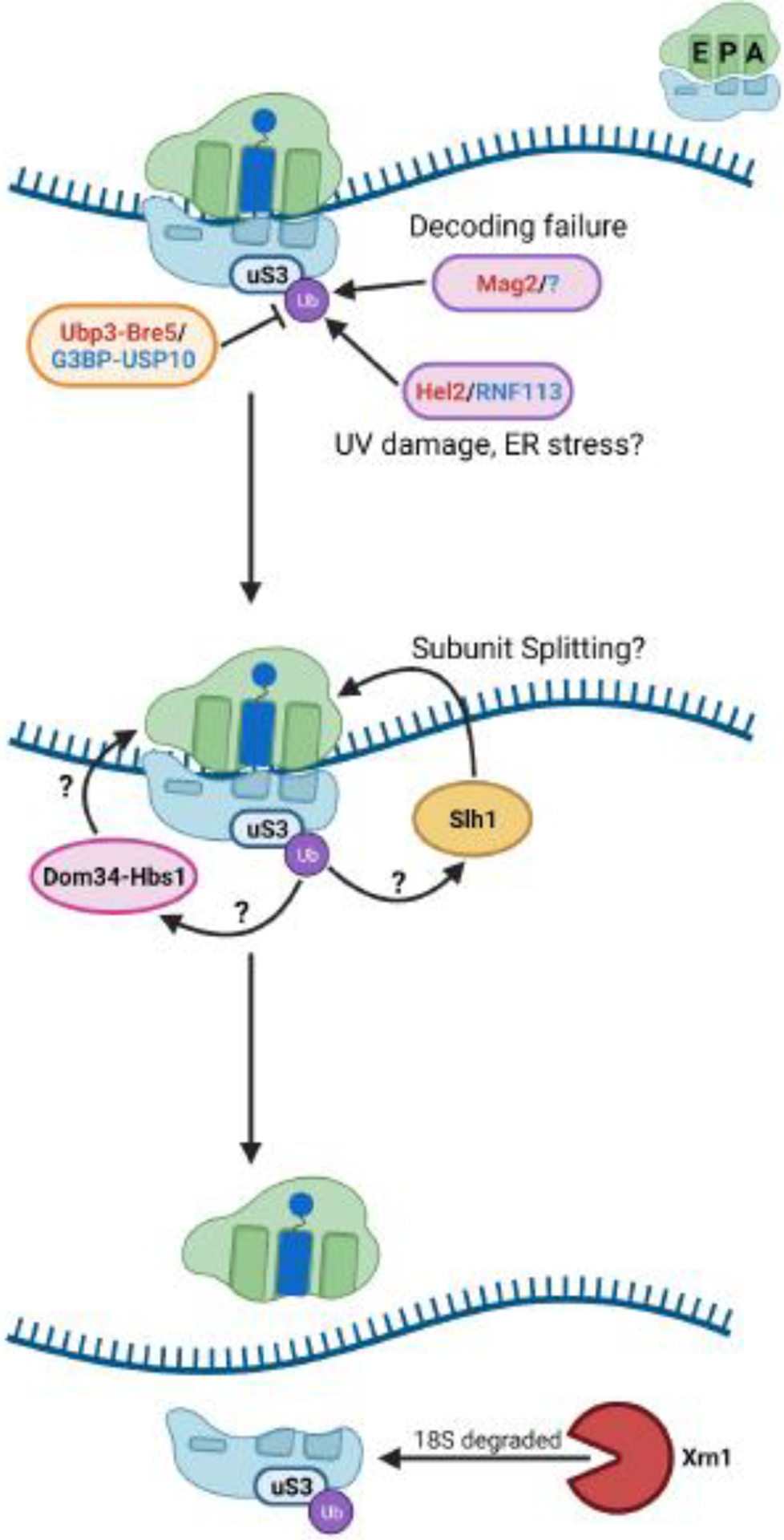

In yeast, 18S NRD is initiated by mono-ubiquitination of uS3 K212 by the E3 ligase Mag2, followed by K63-polyubiquitination by Hel2 or Rsp5 (Figure 3) [49]. After 80S splitting in an alternative ribosome rescue factor, Dom34, and Slh1-dependent manner, the 18S rRNA is degraded by a yet uncharacterized pathway that requires the major exonuclease Xrn1 [49]. Ubiquitination of uS3 does not appear to commit the 18S to destruction, however. In humans, the G3BP1-USP10 complex was found to remove ubiquitin from ribosomal proteins uS3, uS5, and eS10, which prevented lysosome degradation of the 18S rRNA [51] (Figure 1C). The homologous complex in yeast, Bre5-Ubp3p, de-ubiquitinates uS3 and eS7 [45,52]. These findings indicate that uS3 signaling is part of a complex system regulating ribosome stasis.

Figure 3. Nonfunctional ribosome decay (NRD) of 18S rRNA.

Small cartoon depicting the A, P, and E sites is in the top right of the figure. In yeast, uS3 ubiquitination by Mag2 in response to decoding failure by the small subunit leads to subunit splitting and degradation of the 18S rRNA. uS3 can be ubiquitinated in response to other stimuli, such as UV damage, and deubiquitinated by Ubp3-Bre5 (yeast) or G3BP-USP10 (human). How these signaling processes are coordinated remains unclear. The role of ribosome splitting factors Slh1 and Dom34-Hbs1, as well as their interplay, during 18S NRD in yeast also remain undetermined. Names of the factors in red/blue denote the yeast and mammalian factor, respectively.

It is unclear how activation of 18S NRD is coordinated with that of RQC, as uS3 ubiquitination is necessary for 18S NRD but is dispensable for RQC. The work on 18S NRD utilized a mutant 18S rRNA [49], but cycloheximide-induced collisions and UPR also lead to ubiquitination of uS3 [13,45,46]. In this case, the overall ubiquitin signaling or uS5 ubiquitination status might serve as unique signature to delineate when the 18S rRNA is targeted for recycling or for degradation. Ubiquitination also appears to be hierarchical, at least in human, where uS10 and eS10 ubiquitination events are needed for uS3 and uS5 ubiquitination, and uS3 is potentially ubiquitinated before uS5 [40]. Perhaps uS3 is initially ubiquitinated on collided ribosomes as a signal for quality-control pathways to further probe translational competency of ribosomes. Subsequent ubiquitination of other uS3 lysine residues, uS5, or other ribosomal proteins could then act as downstream checkpoints for 18S status.

Alternatively, since non-functional ribosomes are expected to lead in a ribosome pileup distinct from pileups that occur on aberrant mRNAs, it might be possible to differentiate between the two types of stalls. Specifically, mutations in the decoding center of the small subunit, which have been used to probe 18S NRD, inhibit tRNA selection altogether [53]. Therefore, ribosomes harboring these mutations are expected to stall on the start codon and cause collisions different than ones occurring further downstream. In this case, it is possible that a collision between the initiating small subunit and the defective ribosome is used to activate 18S NRD.

Preventing further translation on aberrant mRNAs

A pressing problem for the cell is preventing ribosomes from initiating on defective transcripts. Although the transcript can be degraded through mRNA-surveillance pathways after a collision is detected, additional ribosomes might continue to initiate on the transcript during the intervening period before decay. This would incur costs in the loss of competent ribosomes and the energy expended to rescue them from the transcript. It follows that cells would have evolved mechanisms to suppress further initiation on aberrant mRNAs. A recent study by Hickey and colleagues used a genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 screen to identify mammalian factors whose absence contributed to increased protein production on stalling reporters [54]. Interestingly, in addition to known RQC factors, the factors GIGYF2 and 4EHP (eIF4E2) were identified as some of the top hits in the screen [54]. These factors are part of an initiation-repressor complex that inhibits recognition of the mRNA cap structure by the translation initiation factor eIF4E, preventing translation initiation [55]. In agreement with a role for these factors in RQC, both were previously shown to interact with ZNF598 [55].

At first glance, this interaction could explain how they might be specifically recruited to stalled ribosomes. However, it turns out that neither ZNF598 nor ZNF598-mediated ubiquitination are required for GIGYF2/4EHP recruitment to aberrant mRNAs [20,56]. Instead, two independent studies identified the requirement for the transcriptional coactivator EDF1 in recruiting the repressor complex to ribosomes (Figure 4) [20,56]. In both studies, unbiased mass-spectrometry approaches showed that EDF1 bound collided ribosomes [20,56]. Notably, Mbf1, the yeast homologue of EDF1, was previously shown to prevent +1 frameshifting, resulting from ribosomal collisions, on stalling sequences [57,58]. Cryo-EM structures of Mbf1 and EDF1 in complex with collided ribosomes revealed that the factors display identical modes of binding; both bind along the entry tunnel of the mRNA of collided ribosomes that have adopted a rotated state [20]. Mbf1/EDF1 also makes extensive contacts with uS3, a factor known to be important for reading-frame maintenance by the ribosome [57,59]. While these structures provide important clues about how Mbf1/EDF1 may prevent frameshifting, they do not tell us about how they contribute to RQC.

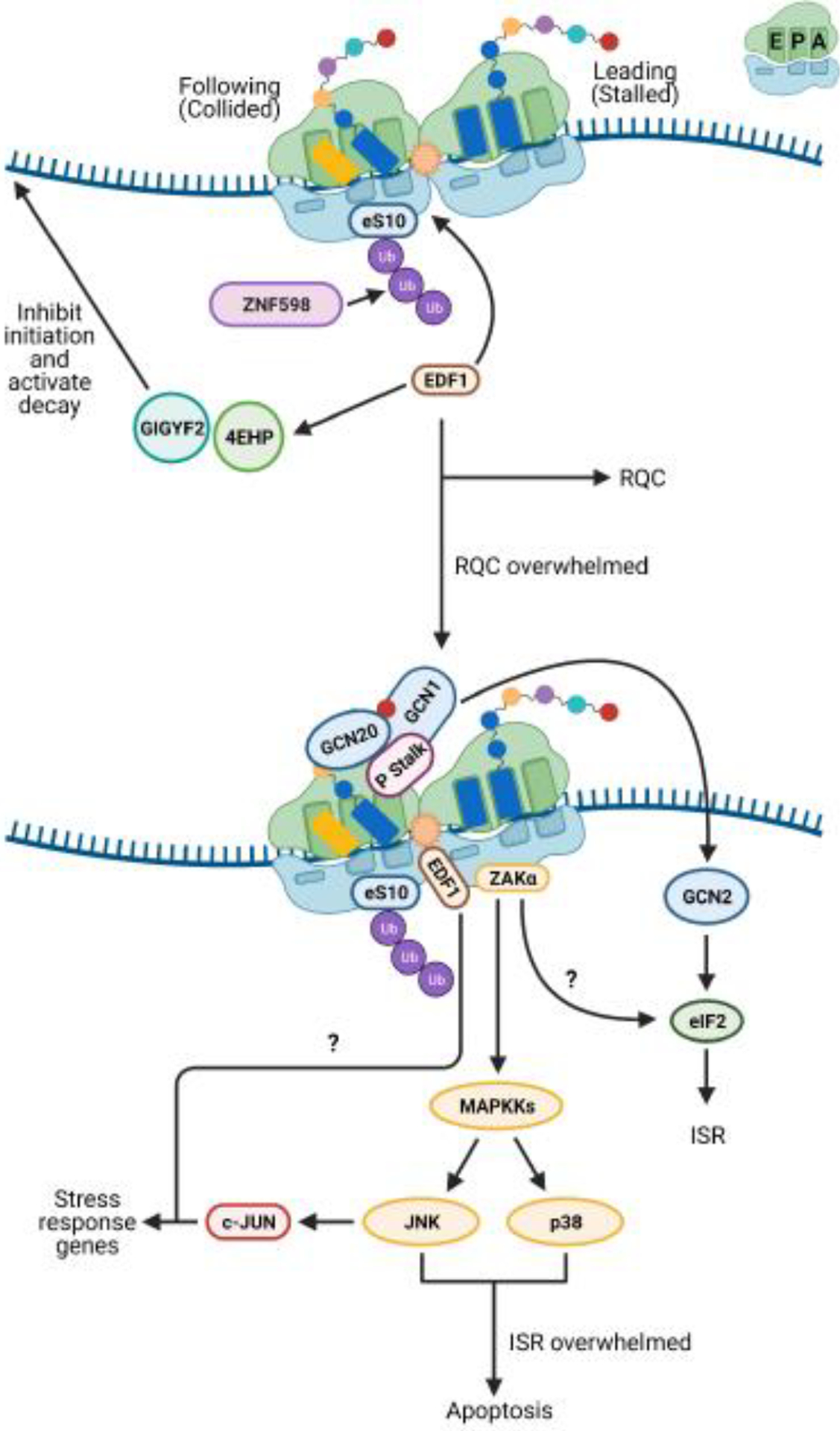

Figure 4. Collided ribosomes are a signaling hub for stress response factors.

Small cartoon depicting the A, P, and E sites is in the top right of the figure. In mammalian cells, when numbers of collided ribosomes remain low, the ribosome-associated quality control (RQC) pathway is able to deal with stalled ribosomes ubiquitinated by ZNF598. The factor EDF1 is recruited to the small subunit of the collided ribosome by a still-undetermined mechanism and potentially acts to prevent frameshifting during stall resolution. EDF1 also appears to play a role in the recruitment of the factors GIGYF2 and 4EHP to repress initiation on aberrant transcripts. When collision frequencies become elevated, such as during nutrient stress, the RQC machinery is overwhelmed, and alternative response pathways become activated. The P stalk of long-lived collided ribosome species may activate the integrated stress response (ISR) kinase GCN2. It is still unknown how GCN2’s cofactors GCN1 and GCN20 coordinate with the P stalk to activate GCN2. Long-lived collisions may also activate the mitogen activated kinase kinase kinase (MAPKKK) ZAKα. The mechanism by which ZAKα is activated has not been clearly determined. ZAKα signaling activates p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) and might play a role in ISR signaling. JNK signaling leads to upregulation of the stress response transcription factor c-Jun, which in turn upregulates stress response genes. In addition to its other activities, EDF1 appears to contribute to c-Jun transcriptional activity via an unknown mechanism. In the event the ISR fails to restore homeostasis, p38 and JNK signaling leads to apoptosis.

Activating stress responses when the quality control machinery is overwhelmed

It is unlikely that RQC is the primary system for dealing with ribosome collisions since Hel2/ZNF598 is substoichiometric to ribosomes [30,31]. One can easily see how the RQC machinery would be overwhelmed under stress conditions that lead to an elevated frequency of ribosome collisions. For instance, amino-acid deprivation, which leads to depletion of aminoacylated tRNAs, and alkylation and oxidation stresses, which globally damage RNA, have been documented to increase levels of ribosome collisions [60,61]. Under these conditions, cells instead appear to activate pro-survival pathways such as the integrated stress response (ISR), and if the stress is severe, programmed-cell death (apoptosis).

The ISR is a conserved eukaryotic stress response triggered by a diverse set of endogenous and exogenous signals (Box 2). In mammals, various stresses are monitored by distinct protein kinases that, upon activation, phosphorylate the α subunit of the translation initiation factor eIF2. Phosphorylation of eIF2α promotes the selective translation of a subset of mRNAs required for survival and recovery from stress (for reviews, see [62–64]). Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been used as a model for studying the ISR, owing to the conserved mechanism of its activation and the presence of only one known eIF2α kinase, Gcn2 [65]. Gcn2 is typically activated in response to amino-acid starvation and robust activation requires the presence of two coactivators, Gcn1 and Gcn20 [66–68]. In the classical model, it is thought that Gcn2 is activated by binding to deacylated tRNAs on the ribosome, with Gcn1 and Gcn20 aiding in the delivery of the deacylated tRNA to its tRNA-synthetase-like domain [66–68]. However, Gcn2 can also be robustly activated by conditions that would not be expected to increase levels of deacylated tRNAs [61,69,70], suggesting that the kinase can be activated via alternative mechanisms.

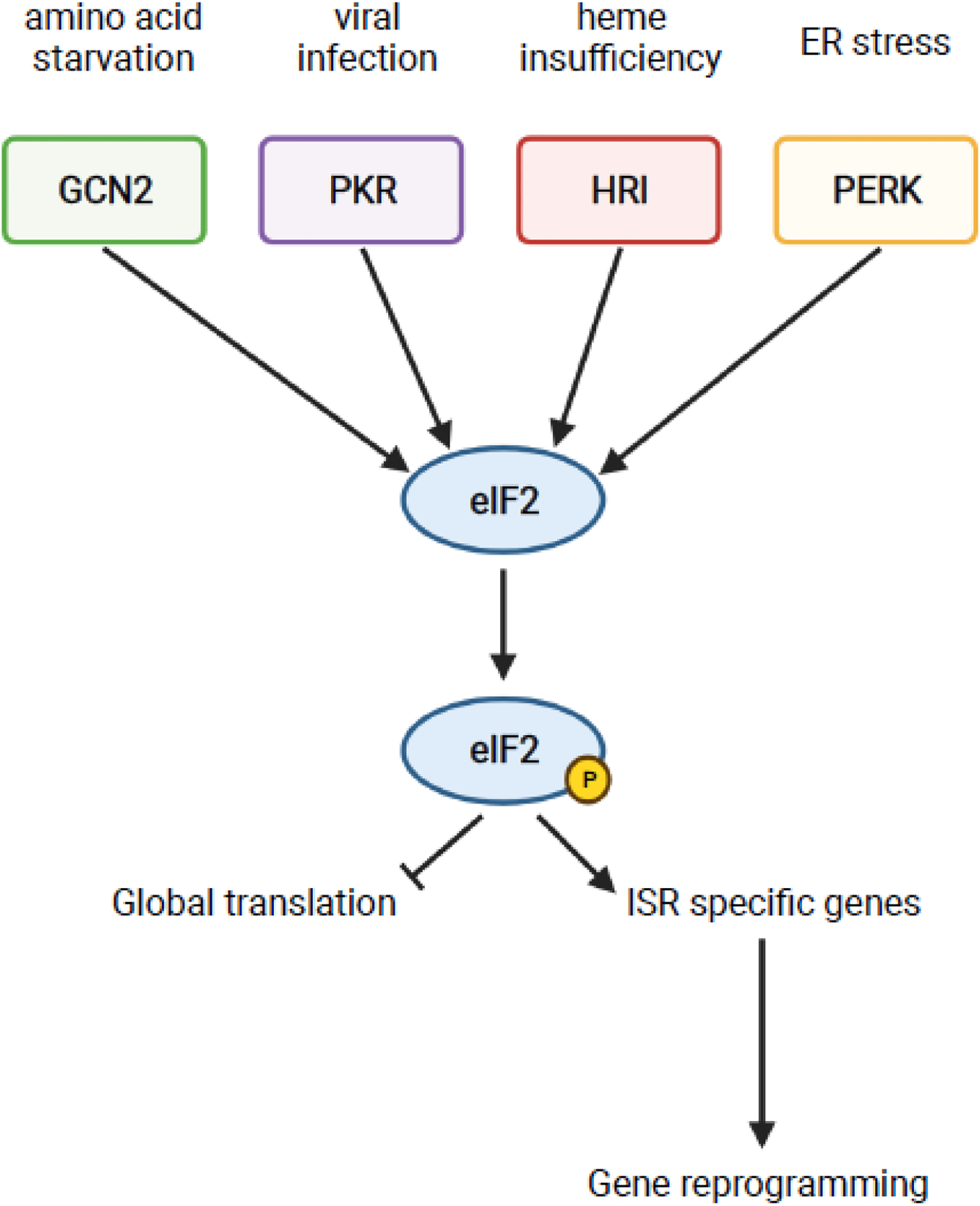

Box 2. Activation of the Integrated Stress Response.

The integrated stress response (ISR) is a conserved stress response in eukaryotes [63]. In mammals, the system is comprised of four kinases that monitor distinct stresses: GCN2 for amino-acid starvation, PKR for viral infection, HRI for heme insufficiency, and PERK for endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress [62–64]. Upon activation in response to their respective stress, the kinases dimerize and undergo autophosphorylation [91]. The kinases all signal through the common axis of phosphorylating the translation initiation factor eIF2, leading to rapid inhibition of global translation and translation of ISR-specific genes such as ATF4 (Gcn4 in yeast) [92,93]. Translation of ISR-specific genes mediates reprogramming of gene expression to recover from the stress and return to homeostasis [92,94].

Activation of GCN2 is extensively discussed in this review, thus we will discuss the activation mechanisms of the other kinases. The kinase PKR is found in mammals and is activated in response to double-stranded RNA, typical of viral infections [62–64]. However, other stresses such as oxidative stress, ER stress, growth factor deprivation, cytokine signaling, bacterial infection, ribotoxic stress, accumulation of stress granules, and heparin treatment have been found to activate PKR in a dsRNA-independent manner [62]. The kinase HRI monitors heme availability and is primarily expressed in erythroid cells [62–64]. HRI contains several heme binding domains; absence of heme binding in the kinase insertion domain, due to low levels of heme, enables dimerization and autophosphorylation [62,64]. Like how PKR can respond to alternative stresses, HRI can be activated via heme-independent mechanisms in response to arsenite-induced oxidative stress, heat shock, osmotic stress, 26S proteasome inhibition, and nitric oxide [62,64]. The kinase PERK is found in metazoans and is normally bound to the ER by GRP78 [62,64]. ER stress as a result of accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER, changes in cellular energy levels, disruptions in calcium homeostasis, or alterations in redox status leads to activation of PERK [62,64]. There are currently two models of PERK activation; the classical model proposes that ER stress leads to dissociation of GRP78 from PERK, enabling dimerization and autophosphorylation, while a more recent model suggests that direct binding of unfolded/misfolded protein to PERK can activate the kinase [62–64]. All the kinases share overlapping functions and can partially compensate for loss of others [62], highlighting the redundancy built into such an important system.

The clue for these alternative mechanisms came when Ishimura and Nagy et al. reported that ribosome stalling also activates GCN2 and subsequently the ISR in mammals [71]. Neurons from mice containing a loss-of-function mutation in the rescue factor GTPBP2 were found to activate GCN2 in the presence of reduced levels of tRNAArgUCU [71]. Importantly, elevated levels of ribosome stalling occurred on AGA codons without an accompanying increase in deacylated tRNAs levels [71]. These observations pointed to a ribosome-centric mode for ISR activation by GCN2. Soon afterwards, two groups provided further support for this model. Inglis and Mason et al. reconstituted GCN2-mediated phosphorylation of eIF2α in vitro and found that ribosomes activate the kinase much more robustly than deacylated tRNAs [72]. Further analysis using hydrogen-deuterium exchange mass spectrometry (HDX-MS) revealed that the P stalk of the ribosome interacts with GCN2 and that the P stalk in isolation is sufficient to stimulate kinase activity. Independently, using a CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis screen in Chinese hamster ovary cells, Harding and colleagues identified components of the P stalk to be important for GCN2 function [73]. In-vitro reconstitution experiments further supported these observations, whereby wild-type ribosomes stimulated GCN2 activity but not ribosomes isolated from P-stalk mutant cells [73].

A stalling-induced activation model was appealing since many stress conditions cause widespread stalling and activate the ISR [60,61,69,70,74,75]. However, at least three important questions remained unaddressed: what conformation of the ribosome activates the ISR, how conserved is the activation mechanism, and how is ISR activation coordinated with that of RQC? Two very recent studies partially addressed these questions [61,76]. In a study from our group, yeast Gcn2 was found to be activated by conditions that promote ribosome collisions [61]. Similar to what was observed for Hel2-mediated ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins, addition of antibiotics and stalling agents only at concentrations that promote collisions were found to promote eIF2α phosphorylation by Gcn2. These observations suggest that collided ribosomes activate Gcn2 and that stalling-induced activation of the ISR is a conserved mechanism across eukaryotes (Figure 4). Indeed, Gcn2’s coactivator, Gcn1, appears to preferentially bind to collided ribosomes in mammals and yeast [66,76,77]. A recent cryo-EM structure of yeast Gcn1 in complex with a collided disome provided an important molecular basis for this specificity [76]. Gcn1 was found to snake its way across the disome unit, making interactions with the stalled and collided ribosomes. Although the structure of the complex represents an inactivated state in which the repressors Rpg2/Gir2 are bound in the A site of the lead ribosome, presumably preventing Gcn2 from binding, it provided some important clues about how Gcn2 and its coactivators recognize stalled ribosomes. In the future, it will be interesting to identify how recognition of collided ribosomes is relayed by Gcn1 to activate the kinase domain of Gcn2.

The observation that RQC and the ISR are activated via the same ribosome stalling signal suggests that the two processes must coordinate the activation of their factors, especially given that they lead to distinct cellular responses. Transcriptomic profiling from the Guydosh group [8] and our group [61] revealed that RQC suppresses the premature activation of Gcn2 in the absence of stress conditions. Furthermore, our data showed that the presence of Hel2 attenuates the activation of Gcn2 in response to several stressors, suggesting that activation of RQC suppresses that of the ISR. By contrast, when the ISR is inhibited, RQC is overactivated – as judged by increased Hel2-mediated ubiquitination – suggesting that the two processes are in apparent competition. Interestingly, although Hel2 has no preference for the nature of the stalled ribosome, Gcn2 and/or its coactivators appear to prefer stalled ribosomes with an empty A site [61]. These observations indicate that although both pathways recognize collided ribosomes, they are not in direct competition with each other and instead bind to distinct regions on the ribosome. However, Hel2 appears to be more sensitive to changes to the translational machinery and responds more robustly to lower collision frequencies than does Gcn2, suggesting that RQC is activated more rapidly than ISR [61]. This presents a model in which low numbers of collided ribosomes, as a result of defects in a few mRNAs, are rescued through RQC before they can activate Gcn2. Under stress conditions in which collisions are more frequent and widespread, Hel2 is likely to get overwhelmed, enabling activation of Gcn2 and subsequent activation of the ISR.

Long-term signaling consequences via MAPKKKs

The observations that collided ribosomes are recognized by numerous factors involved in distinct downstream processes suggest that they are widely used to gauge cellular conditions. The appeal of such a mechanism stems from the observation that the translational machinery is exquisitely sensitive to cellular status, functioning as a sort of molecular sentinel to alert cells to environmental changes. Thus far, we have discussed how the frequency of ribosome collisions is potentially used to mount a quality-control process versus a stress-response pathway. But what if conditions are so severe that neither of these pathways can mitigate the impact on translation? Typically, these conditions prompt cells to arrest the cell cycle and/or activate programmed cell death [78]. Interestingly, we have known for a while that conditions that alter ribosome function in mammals robustly activate the stress-activated kinases (SAPKs), p38 and c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), in a process termed the ribotoxic stress response (RSR) [79,80]. Activation of SAPKs then lead to cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis [79–82]. Studies have implicated the Mitogen Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase (MAPKKK) ZAK as the upstream kinase of p38 and JNK [83,84].

Up until recently, an important question that remained unresolved was how ZAK was activated to trigger the RSR. Two studies suggested that the ribosome itself plays a direct role in ZAK activation, in which the long isoform of the protein, ZAKα, interacts with the ribosome to sense perturbance to its function [19,85]. However, the studies reached conflicting conclusions about how the perturbed ribosome is probed by ZAKα. Vind et al. argued that the factor associates with ribosomes and under ribotoxic stress, uses sensor domains to inspect alterations to functional sites on the ribosome, irrespective of collisions [85]. In contrast, Wu et al. argued that even though ZAKα. interacts with elongating ribosomes, it is auto-phosphorylated in response to ribosome collisions, and consequently activates RSR (Figure 4) [19]. In addition, the authors also suggested that robust activation of ISR by GCN2 requires the presence of ZAKα [19]. The distinct conclusions reached by the two groups on the conformation of the ribosome responsible for ZAKα activation cannot not be readily reconciled, especially since the studies also reached differing conclusions regarding the interplay between ZAKα and RQC. As noted in Wu et al., differences in experimental conditions may explain some of these discrepancies [19], but more studies are needed to hammer out the exact molecular mechanism by which RSR is activated during stalling.

Concluding remarks

It is becoming more and more evident that the ribosome plays a broader role in maintaining cellular homeostasis beyond ensuring proper production of protein from mRNA. Given that the translational machinery is intimately connected to environmental conditions, it comes as no surprise that cells appear to utilize ribosomes as sensors of the cellular state. Indeed, very recently ribosomal collisions have even been implicated in the co-activation of the innate immune response through cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) [86]. The fact that so many processes seem to monitor ribosomal collisions has given rise to the idea that global collision frequency is used as a rheostat by the cell, selecting the most appropriate pathway when problems during translation are detected. Under normal conditions or when stresses are manageable, cells use the RQC pathway to resolve infrequent pileups that result from aberrant mRNAs. If stresses become more severe, and subsequently the frequency of collisions increase, the same collision event is then employed to activate ISR. Finally, if homeostasis cannot be achieved and collision frequency remains high, signaling from ribosome collisions leads to apoptosis and cell death.

While the most recent batch of studies have gleaned important details on each of these various pathways, we have only begun to scratch the surface (see Outstanding questions). Many details of the complex regulatory ubiquitin-signaling network underlying RQC have yet to be determined. In addition, the mechanisms that coordinate RQC with ISR require further investigation. Ultimately, deeper understanding of how cells deal with collided ribosomes will open new frontiers in understanding how cells sense and respond to an ever-changing environment.

Outstanding Questions.

How are collided ribosomes recognized by Hel2/ZNF598?

How is the lead ribosome in a pileup differentiated from upstream ribosomes, and which ribosomes in a pileup are ubiquitinated?

What are the various signatures of ubiquitin signaling on ribosomal proteins and which signatures correspond to various ribosome fates?

How are stalled ribosomes recognized and disassembled by the RQT complex? How is disassembly coordinated with mRNA cleavage mechanisms?

How is the Not4/Not5 response coordinated with that of Hel2/ZNF598?

What are the mechanisms that underlie GCN2 activation on the ribosome and how are these activities coordinated with that of RQC?

Does Mbf1/EDF1 play additional roles during ribosomal collisions?

Highlights.

Collision of ribosomes is the key event for quality-control processes and other stress response pathways during translation

The collided di-ribosome adopts a unique structure that acts as a signaling platform for various factors

Differential ubiquitination of ribosomal proteins determines which pathways are activated and the fate of the ribosome

Ribosome-quality control and the Integrated Stress Response appear to antagonize one another’s activation

Ribosome collisions are utilized to trigger global reprogramming of gene expression in response to stress

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank members of Zaher lab for useful discussions. Research in the Zaher lab is supported by the National Institutes of Health (R01GM112641). Figures were created using BioRender.com. MarvinSketch was used to draw the inosine-adenosine base pair in Box 1, MarvinSketch 21.8.0, ChemAxon (https://www.chemaxon.com).

Glossary:

- Initiation-Repressor Complex

complexes which inhibit translation initiation by interfering with the ability of the translation initiation factors to recognize mRNAs and recruit the ribosome.

- Integrated Stress Response (ISR)

a stress response conserved across eukaryotes which can be activated by various endogenous and exogenous signals. Several protein kinases monitor distinct stresses and upon activation, phosphorylate the translation initiation factor eIF2. Phosphorylation of eIF2 results in repression of global translation but concomitant translation of pro-survival genes in an attempt to restore homeostasis.

- mRNA-Surveillance Pathways

various eukaryotic pathways that evolved to detect defects in mRNAs during translation and initiate accelerated decay of the aberrant transcript.

- Non-Functional rRNA Decay (NRD)

Pathways responsible for degradation of defective ribosomal RNAs.

- No-Go Decay (NGD)

an mRNA-surveillance pathway which degrades mRNAs containing sequences, nucleobase modifications, or RNA structures that cause non-productive stalling of translating ribosomes; typically coupled with the ribosome-associated quality control pathway.

- No-Go DecayRQC- (NGDRQC-)

an alternative pathway for the decay of mRNAs containing stalled ribosomes which occurs in the absence of RQC activity. It is hypothesized to be the pathway responsible for translation-linked decay when RQC is overwhelmed.

- Replisome

a conserved multi-protein complex responsible for the replication of genomic DNA. The core components of a replisome are a helicase, DNA polymerase(s), a primase, a single-stranded DNA binding protein, a sliding clamp, and a clamp loader protein.

- Ribosome-Associated Quality Control (RQC)

a conserved eukaryotic pathway responsible for the detection and proteasomal degradation of incomplete nascent polypeptide chains on ribosomes stalled on aberrant mRNAs.

- Ribosome-Quality Control Trigger (RQT) Complex

a multi-protein complex that is hypothesized to dissociate stalled ribosomes into their respective subunit components following the ubiquitination of the ribosomal proteins.

- Ribotoxic Stress Response (RSR)

a cellular response which results in the activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases when ribosome structure or function is altered.

- Unfolded Protein Response (UPR)

a conserved eukaryotic stress response that is activated in response to disruptions in cellular protein folding capacity in the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum. The pathway signals for inhibition of translation, degradation of the misfolded proteins, and upregulation of molecular chaperones. If these measures fail to restore proteostasis, the pathway signals for apoptosis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.García-Muse T and Aguilera A (2016) Transcription-replication conflicts: How they occur and how they are resolved. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 17, 553–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sørensen MA and Pedersen S (1991) Absolute in vivo translation rates of individual codons in Escherichia coli. The two glutamic acid codons GAA and GAG are translated with a threefold difference in rate. J. Mol. Biol 222, 265–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitarai N et al. (2008) Ribosome Collisions and Translation Efficiency: Optimization by Codon Usage and mRNA Destabilization. J. Mol. Biol 382, 236–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farabaugh PJ (1996) Programmed translational frameshifting. Annu. Rev. Genet 30, 507–528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richter JD and Coller J (2015) Pausing on Polyribosomes: Make Way for Elongation in Translational Control. Cell 163, 292–300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrin MA and Subramaniam AR (2017) Kinetic modeling predicts a stimulatory role for ribosome collisions at elongation stall sites in bacteria. Elife 6, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han P et al. (2020) Genome-wide Survey of Ribosome Collision. Cell Rep 31, 107610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Meydan S and Guydosh NR (2020) Disome and Trisome Profiling Reveal Genome-wide Targets of Ribosome Quality Control. Mol. Cell 79, 588–602.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan LL and Zaher HS (2019) How do cells cope with RNA damage and its consequences? J. Biol. Chem 294, 15158–15171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Simms CL et al. (2017) Ribosome-based quality control of mRNA and nascent peptides. WIREs RNA 8, e1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howard CJ and Frost A (2021) Ribosome-associated quality control and CAT tailing. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol DOI: 10.1080/10409238.2021.1938507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doma MK and Parker R (2006) Endonucleolytic cleavage of eukaryotic mRNAs with stalls in translation elongation. Nature 440, 561–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simms CL et al. (2017) Ribosome Collision Is Critical for Quality Control during No-Go Decay. Mol. Cell 68, 361–373.e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Juszkiewicz S et al. (2018) ZNF598 Is a Quality Control Sensor of Collided Ribosomes. Mol. Cell 72, 469–481.e7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeuchi K et al. (2019) Collided ribosomes form a unique structural interface to induce Hel2-driven quality control pathways. EMBO J 38, 1–21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D’Orazio KN and Green R (2021) Ribosome states signal RNA quality control. Mol. Cell 81, 1372–1383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yip MCJ and Shao S (2021) Detecting and Rescuing Stalled Ribosomes. Trends Biochem. Sci DOI: 10.1016/j.tibs.2021.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inada T (2017) The Ribosome as a Platform for mRNA and Nascent Polypeptide Quality Control. Trends Biochem. Sci 42, 5–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu CCC et al. (2020) Ribosome Collisions Trigger General Stress Responses to Regulate Cell Fate. Cell 182, 404–416.e14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinha NK et al. (2020) EDF1 coordinates cellular responses to ribosome collisions. Elife 9, 1–84 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saito K et al. (2015) Inhibiting K63 Polyubiquitination Abolishes No-Go Type Stalled Translation Surveillance in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS Genet 11, 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Letzring DP et al. (2013) Translation of CGA codon repeats in yeast involves quality control components and ribosomal protein L1. Rna 19, 1208–1217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brandman O et al. (2012) A Ribosome-Bound Quality Control Complex Triggers Degradation of Nascent Peptides and Signals Translation Stress. Cell 151, 1042–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Matsuo Y et al. (2017) Ubiquitination of stalled ribosome triggers ribosome-associated quality control. Nat. Commun 8, 1–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winz ML et al. (2019) Molecular interactions between Hel2 and RNA supporting ribosome-associated quality control. Nat. Commun 10, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sitron CSS et al. (2017) Asc1, Hel2, and Slh1 couple translation arrest to nascent chain degradation. Rna 23, 798–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Singh RK et al. (2012) Novel E3 ubiquitin ligases that regulate histone protein levels in the budding yeast saccharomyces cerevisiae. PLoS One 7, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Juszkiewicz S and Hegde RSS (2017) Initiation of Quality Control during Poly(A) Translation Requires Site-Specific Ribosome Ubiquitination. Mol. Cell 65, 743–750.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sundaramoorthy E et al. (2017) ZNF598 and RACK1 Regulate Mammalian Ribosome-Associated Quality Control Function by Mediating Regulatory 40S Ribosomal Ubiquitylation. Mol. Cell 65, 751–760.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garzia A et al. (2017) The E3 ubiquitin ligase and RNA-binding protein ZNF598 orchestrates ribosome quality control of premature polyadenylated mRNAs. Nat. Commun 8, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ho B et al. (2018) Unification of Protein Abundance Datasets Yields a Quantitative Saccharomyces cerevisiae Proteome. Cell Syst 6, 192–205.e3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Warner JR (1999) The economics of ribosome biosynthesis in yeast. Trends Biochem. Sci 24, 437–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson DN et al. (2016) Translation regulation via nascent polypeptide-mediated ribosome stalling. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol 37, 123–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tsuboi T et al. (2012) Dom34: Hbs1 Plays a General Role in Quality-Control Systems by Dissociation of a Stalled Ribosome at the 3’ End of Aberrant mRNA. Mol. Cell 46, 518–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen L et al. (2010) Structure of the Dom34-Hbs1 complex and implications for no-go decay. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 17, 1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuo Y et al. (2020) RQT complex dissociates ribosomes collided on endogenous RQC substrate SDD1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 27, 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Juszkiewicz S et al. (2020) The ASC-1 Complex Disassembles Collided Ribosomes. Mol. Cell 79, 603–614.e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hashimoto S et al. (2020) Identification of a novel trigger complex that facilitates ribosome-associated quality control in mammalian cells. Sci. Rep 10, 3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chu J et al. (2009) A mouse forward genetics screen identifies LISTERIN as an E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in neurodegeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 106, 2097–2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Garshott DM et al. (2020) Distinct regulatory ribosomal ubiquitylation events are reversible and hierarchically organized. Elife 9, 1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buschauer R et al. (2020) The Ccr4-Not complex monitors the translating ribosome for codon optimality. Science (80-.) 368, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Panasenko OO and Collart MA (2012) Presence of Not5 and ubiquitinated Rps7A in polysome fractions depends upon the Not4 E3 ligase. Mol. Microbiol 83, 640–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Collart MA (2013) The Not4 RING E3 Ligase: A Relevant Player in Cotranslational Quality Control. ISRN Mol. Biol 2013, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Presnyak V et al. (2015) Codon optimality is a major determinant of mRNA stability. Cell 160, 1111–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsuki Y et al. (2020) Ribosomal protein S7 ubiquitination during ER stress in yeast is associated with selective mRNA translation and stress outcome. Sci. Rep 10, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Higgins RR et al. (2015) The Unfolded Protein Response Triggers Site-Specific Regulatory Ubiquitylation of 40S Ribosomal Proteins. Mol. Cell 59, 35–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaRiviere FJ et al. (2006) A late-acting quality control process for mature eukaryotic rRNAs. Mol. Cell 24, 619–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Limoncelli KA et al. (2017) ASC1 and RPS3: New actors in 18S nonfunctional rRNA decay. Rna 23, 1946–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sugiyama T et al. (2019) Sequential Ubiquitination of Ribosomal Protein uS3 Triggers the Degradation of Non-functional 18S rRNA. Cell Rep 26, 3400–3415.e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fujii K et al. (2009) A role for ubiquitin in the clearance of nonfunctional rRNAs. Genes Dev 23, 963–974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer C et al. (2020) The G3BP1-Family-USP10 Deubiquitinase Complex Rescues Ubiquitinated 40S Subunits of Ribosomes Stalled in Translation from Lysosomal Degradation. Mol. Cell 77, 1193–1205.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jung Y et al. (2017) Modulating cellular balance of Rps3 mono-ubiquitination by both Hel2 E3 ligase and Ubp3 deubiquitinase regulates protein quality control. Exp. Mol. Med 49, e390–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yoshizawa S et al. (1999) Recognition of the codon-anticodon helix by ribosomal RNA. Science (80-.) 285, 1722–1725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hickey KL et al. (2020) GIGYF2 and 4EHP Inhibit Translation Initiation of Defective Messenger RNAs to Assist Ribosome-Associated Quality Control. Mol. Cell 79, 950–962.e6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morita M et al. (2012) A Novel 4EHP-GIGYF2 Translational Repressor Complex Is Essential for Mammalian Development. Mol. Cell. Biol 32, 3585–3593 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Juszkiewicz S et al. (2020) Ribosome collisions trigger cis-acting feedback inhibition of translation initiation. Elife 9, 1–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang J et al. (2018) Multi-protein bridging factor 1(Mbf1), Rps3 and Asc1 prevent stalled ribosomes from frameshifting. Elife 7, 1–26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Simms CL et al. (2019) Ribosome Collisions Result in +1 Frameshifting in the Absence of No-Go Decay. Cell Rep 28, 1679–1689.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simms CL et al. (2018) Interactions between the mRNA and Rps3/uS3 at the entry tunnel of the ribosomal small subunit are important for no-go decay. PLoS Genet 14, 1–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yan LL et al. (2019) Oxidation and alkylation stresses activate ribosome-quality control. Nat. Commun 10, 1–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan LL and Zaher HS (2021) Ribosome quality control antagonizes the activation of the integrated stress response on colliding ribosomes. Mol. Cell 81, 614–628.e4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pakos-Zebrucka K et al. (2016) The integrated stress response. EMBO Rep 17, 1374–1395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Costa-Mattioli M and Walter P (2020) The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 368, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Donnelly N et al. (2013) The eIF2α kinases: Their structures and functions. Cell. Mol. Life Sci 70, 3493–3511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hinnebusch AG (2005) Translational regulation of GCN4 and the general amino acid control of yeast. Annu. Rev. Microbiol 59, 407–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sattlegger E and Hinnebusch AG (2005) Polyribosome binding by GCN1 is required for full activation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2α kinase GCN2 during amino acid starvation. J. Biol. Chem 280, 16514–16521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Marton MJ et al. (1997) Evidence that GCN1 and GCN20, translational regulators of GCN4, function on elongating ribosomes in activation of eIF2alpha kinase GCN2. Mol. Cell. Biol 17, 4474–4489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Garcia-Barrio M (2000) Association of GCN1-GCN20 regulatory complex with the N-terminus of eIF2alpha kinase GCN2 is required for GCN2 activation. EMBO J 19, 1887–1899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Natarajan K et al. (2001) Transcriptional Profiling Shows that Gcn4p Is a Master Regulator of Gene Expression during Amino Acid Starvation in Yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol 21, 4347–4368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hughes TR et al. (2000) Functional Discovery via a Compendium of Expression Profiles. Cell 102, 109–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ishimura R et al. (2016) Activation of GCN2 kinase by ribosome stalling links translation elongation with translation initiation. Elife 5, 1–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inglis AJ et al. (2019) Activation of GCN2 by the ribosomal P-stalk. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 116, 4946–4954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harding HP et al. (2019) The ribosomal P-stalk couples amino acid starvation to GCN2 2 activation in mammalian cells. Elife 8, 1–19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Simms CL et al. (2014) An Active Role for the Ribosome in Determining the Fate of Oxidized mRNA. Cell Rep 9, 1256–1264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.You C et al. (2017) Position-dependent effects of regioisomeric methylated adenine and guanine ribonucleosides on translation. Nucleic Acids Res 45, 9059–9067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pochopien AA et al. (2021) Structure of Gcn1 bound to stalled and colliding 80S ribosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 118, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lee SJ et al. (2015) Gcn1 contacts the small ribosomal protein Rps10, which is required for full activation of the protein kinase Gcn2. Biochem. J 466, 547–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kurokawa M and Kornbluth S (2009) Caspases and Kinases in a Death Grip. Cell 138, 838–854 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Iordanov MS et al. (1997) Ribotoxic stress response: activation of the stress-activated protein kinase JNK1 by inhibitors of the peptidyl transferase reaction and by sequence-specific RNA damage to the alpha-sarcin/ricin loop in the 28S rRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol 17, 3373–3381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iordanov MS et al. (1998) Ultraviolet radiation triggers the ribotoxic stress response in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem 273, 15794–15803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Darling NJ and Cook SJ (2014) The role of MAPK signalling pathways in the response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta - Mol. Cell Res 1843, 2150–2163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Duch A et al. (2012) The p38 and Hog1 SAPKs control cell cycle progression in response to environmental stresses. FEBS Lett 586, 2925–2931 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang X et al. (2005) Complete inhibition of anisomycin and UV radiation but not cytokine induced JNK and p38 activation by an aryl-substituted dihydropyrrolopyrazole quinoline and mixed lineage kinase 7 small interfering RNA. J. Biol. Chem 280, 19298–19305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jandhyala DM et al. (2008) ZAK: A MAP3Kinase that transduces Shiga toxin- and ricin-induced proinflammatory cytokine expression. Cell. Microbiol 10, 1468–1477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vind AC et al. (2020) ZAKα Recognizes Stalled Ribosomes through Partially Redundant Sensor Domains. Mol. Cell 78, 700–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wan L et al. (2021) Translation stress and collided ribosomes are co-activators of cGAS. Mol. Cell 81, 2808–2822.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ingolia NT et al. (2011) Ribosome Profiling of Mouse Embryonic Stem Cells Reveals the Complexity and Dynamics of Mammalian Proteomes. Cell 147, 789–802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Arthur LL et al. (2015) Translational control by lysine-encoding A-rich sequences. Sci. Adv 1, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lu J and Deutsch C (2008) Electrostatics in the Ribosomal Tunnel Modulate Chain Elongation Rates. J. Mol. Biol 384, 73–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thomas EN et al. (2020) Alkylative damage of mRNA leads to ribosome stalling and rescue by trans translation in bacteria. Elife DOI: 10.7554/elife.61984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lavoie H et al. (2014) Dimerization-induced allostery in protein kinase regulation. Trends Biochem. Sci 39, 475–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Harding HP et al. (2003) An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell 11, 619–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dever TE et al. (1992) Phosphorylation of initiation factor 2α by protein kinase GCN2 mediates gene-specific translational control of GCN4 in yeast. Cell 68, 585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Harding HP et al. (2000) Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell 5, 897–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]