Abstract

Background:

Despite the central role of primary care in improving health system performance, there are little recent data on how primary care and specialist use has evolved over time and its implications for the range of care coordination needed in primary care.

Objective:

To describe trends in outpatient care delivery and their implications for PCP care coordination.

Design:

Descriptive repeated cross-section study using Medicare claims from 2000–2019, using direct standardization to control for changes in beneficiary characteristics over time.

Setting/Patients:

20% sample of beneficiaries in traditional fee-for-service Medicare.

Measurements:

Annual counts of outpatient visits and procedures, numbers of distinct physicians seen, and the number of other physicians seen by a PCP’s assigned Medicare patients.

Results:

The proportion of Medicare beneficiaries with any PCP visit annually only increased slightly from 61.2% to 65.7% from 2000–2019. The mean annual primary care office visits per beneficiary also changed little from 2009–2019 (2.99 to 3.00) though the mean number of PCPs seen increased from 0.89 to 1.21 (36.0% increase). In contrast, mean annual visits to specialists increased 20% from 4.05 to 4.87 while the mean number of unique specialists seen increased 34.2% from 1.63 to 2.18. The proportion of beneficiaries seeing ≥5 physicians annually increased from 17.5% to 30.1%. In 2000, a PCP’s Medicare patient panel saw a median of 52 other physicians (IQR 23–87), growing to 95 (IQR 40–164) in 2019.

Conclusions:

Outpatient care for Medicare beneficiaries has shifted towards more specialist care received from more physicians without increased primary care contact. This represents a substantial expansion of the coordination burden faced by PCPs.

Limitations:

Data were limited to Medicare beneficiaries and due to the use of a 20% sample, may underestimate the number of other physicians seen across a PCP’s entire panel.

INTRODUCTION

In contrast to many other developed health systems, the US health care system emphasizes use of advanced diagnostic approaches and treatments often delivered by specialists, frequently leading to care that is fragmented and costly.(1–4) The movement towards increasing use of specialty care has accelerated in the past two decades. From 1999–2009, the rate of referrals to other physicians after an office visit nearly doubled, at least in part due to the expanding number of subspecialties that has emerged within the physician workforce, but also due to the emergence of new technologies and treatment approaches that have fueled the development of these new subspecialties.(5),(6,7) In 1980, 62% of office visits by adults ≥65 years of age were with primary care physicians and 38% were with specialists.(8) By 2013, this ratio had flipped with a majority of outpatient visits occurring with specialists.(9)

The specialty care orientation of the US health care system raises concerns given the large body of research that suggests that health systems built upon a robust base of primary care are able to achieve superior outcomes at lower cost.(10–13) These primary care-oriented systems achieved better performance by centering a patient’s care around a trusted primary care provider (PCP) who provides care for the majority of patient conditions and who coordinates care over time.(11)

More specialist use also can have an important impact on the complexity and cognitive burden of managing a primary care panel, potentially undermining attempts to improve coordination and care continuity. Among Medicare beneficiaries in 2005, it was estimated that the median PCP’s patients received care from dozens of other physicians in a year.(14) With rising specialist use, the typical PCP needs to integrate information from an increasingly larger pool of specialists, but the extent to which the coordination burden of primary care has changed over time is unknown.(14,15) There are little recent national data on the extent of increasing specialist use and its implications for PCPs’ burden of care coordination.(16)

To counteract the U.S. health care system’s shift toward specialist-centered care, policymakers and other payers are increasingly making investments designed to reinvigorate primary care, ranging from implementing new billing codes designed for performing non-office based care coordination (17) to payment reforms such as Medicare’s Comprehensive Primary Care Plus program.(18) The larger goal of these initiatives is to realign payment incentives and increase investment in primary care to counterbalance fragmentation and overutilization that might result from an increasingly specialist-dominated health system. It is unclear how primary and specialty care delivery for Medicare beneficiaries has changed in the past 2 decades in the setting of these broad policy changes. We examined trends in outpatient care use among Medicare beneficiaries and quantified how the care received by a typical PCP’s panel has changed over the two-decade period from 2000–2019.

METHODS

Study Sample and Data Sources

We analyzed claims data from 2000–2019 for a 20% national sample of beneficiaries in traditional Medicare. We included all beneficiaries who were alive and had continuous enrollment in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B for a minimum of one calendar year. We examined claims for these beneficiaries from all office-based physicians, excluding specialties that typically do not provide office-based care for a patient panel, such as pathology, radiology and emergency medicine. PCPs were defined as physicians with a specialty of general internal medicine, family medicine, general practice, or geriatrics; all other office-based physicians were considered specialists. We also included nurse practitioners as PCPs in our sample because 82% practice primary care or geriatrics.(19) We excluded physician assistants, only 26% of whom practice primary care.(20)

Patient Assignment to PCPs

To attribute patients to PCPs, we assigned beneficiaries to the primary care clinician who delivered the plurality of office visits to a beneficiary based on care delivered within that calendar year.(21,22) We identified visits to primary care based on claims with outpatient evaluation and management Current Procedural Terminology codes 99201–99215, 99211–99215, and 99241–99245 (pre-2010)(23) or preventive care codes 99381–99387, 99391–99397, and G0438-G0439 (post-2011)(24) to physicians with a PCP specialty. If there were no primary care visits, we assigned enrollees to the office-based specialist with the plurality of visits. Any ties between physicians were broken randomly.

Outcome Measures

Outpatient Care Delivery

For outpatient visit use, we identified all evaluation and management services as well as visits to specialists for procedures with a relative value unit value of at least 2.0 in order to capture surgical procedures that often are reimbursed via bundled fees that include pre- and post-procedure assessments. We excluded claims for laboratory and other services not requiring a physician visit. We separated outpatient visits and procedures into mutually exclusive groups of visits with PCPs or specialists and measured the number of distinct PCPs and specialists seen as well as the number of distinct practices visited for PCP and specialist services (classified by unique tax identifier numbers), defined based on the specialty of the physician providing the service. We calculated the percentage of beneficiaries with any visit to a PCP or specialist, and among those with any visit, the number of visits to PCPs or specialists.

PCP Coordination Burden

We captured the number of other physicians seen by a PCP’s assigned Medicare patients, which serves as an indicator for the burden of care coordination necessary for a PCP to manage their panel’s care.(25–27) Because our study population is limited to a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries, our measure of degree may underestimate the absolute value of degree that would be calculated using data on 100% of a physician’s panel. However, prior research has found that 20% samples can identify degree in claims data with reasonable accuracy.(28) More importantly, our major focus is on change in this measure over time, and any under-ascertainment would therefore be consistent over time.

Covariates

From Medicare enrollment files, we gathered information on patients’ age, sex, race, rural vs. non-rural categorization of their ZIP code of residence, and original reason for Medicare enrollment (i.e., disability vs. age). Data on race came from an imputed variable created by the Research Triangle Institute for Medicare.(29) This variable is used for federal reporting on racial disparities and is considered accurate for identifying Black populations, with a sensitivity and specificity of 96.7% and 99.4%.(29) We excluded 0.7% of beneficiaries from 2000–2019 who had missing race data. We defined “rural” as any Rural Area Commuting Area(30) that was smaller than metropolitan or micropolitan, both of which were classified as “non-rural.” We did not measure comorbidities because of broad changes in the intensity and variation of diagnostic coding intensity that occurred over the course of this 20-year time period that were heavily influenced by differences in regional practices, reimbursement policy, and racial bias.(31–34) Though measures of comorbidity in claims data increased from 2000–2019,(35) other markers of health status for 65+ year-old adults independent from the health care system, such as life expectancy at 65 years and self-reported health, improved over this period. (36)

Statistical Analysis

We examined the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries meeting our inclusion criteria and tested for changes over time using bivariate or chi-squared tests as appropriate. We plotted unadjusted trends in the mean and 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentile at the individual physician level for outcomes as appropriate.

To account for changes in the composition of the study population over time when estimating trends, we used direct standardization with PROC STDRATE in SAS (v 9.2) to weight beneficiaries in every year in 96 bins of age in 5-year increments, sex, race/ethnicity, and eligibility category for Medicare to match the distribution of Medicare beneficiaries in 2019, the final year of our data. (details and code in Appendix Methods).

We also examined trends for the office visit outcomes across two specific, traditionally disadvantaged subgroups, beneficiaries of Black race (compared to White beneficiaries) and those living in rural areas (compared to non-rural areas). We compared the rates of change from 2000–2019 between White and Black or rural and non-rural beneficiaries to understand whether gaps that existed at the start of the study period grew, shrunk or stayed stable over time. For the comparison of rates by race, we performed a sensitivity analysis using linear regression adjusting for the same variables used for direct standardization, with and without geographic fixed effects for hospital referral regions,(37) to examine whether differences in outcomes between White and Black beneficiaries were driven by within- vs. across-area differences. If controlling for geographic fixed effects substantially affects our trend estimates, that implies that racial disparities are explained by variation in the measured outcomes across hospital referral regions. If fixed effects change our estimates minimally, that implies that disparities generally are attributable to differences in care received between white and Black beneficiaries within the same hospital referral regions.

Analyses were performed in SAS (v. 9.2). For most of the descriptive results, 95% confidence intervals are not presented because standard errors on our estimates were typically <0.5% of the point estimate due to the very large sample sizes. This study was approved by the institutional review board at Harvard Medical School. Informed consent was waived because the data were de- identified.

Role of the Funding Source

The study was supported by the National Institute on Aging (K23 AG058806 and P01 AG032952). The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, or reporting of the study. Dr. Barnett had full access to all study data and takes responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the analysis.

RESULTS

Our study sample increased from 6,140,952 beneficiaries in 2000 to 7,165,513 in 2019. The study sample received care from 112,252 and 244,355 PCPs and 161,956 and 276,955 specialists in 2000 and 2019, respectively. The beneficiary’s average age decreased slightly from 72.1 (SD 12.4) in 2000 to 71.6 (SD 11.5) in 2019 (Table 1). The percentage of White beneficiaries fell from 85.4% to 77.5%.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics of Medicare Enrollees, 2000–2019

| 2000 | 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Beneficiaries | 6,140,952 | 7,165,513 |

| Median Age (IQR) | 73 (68–80) | 72 (67–78) |

| Age Categories | ||

| Under 65 | 14.5% | 14.0% |

| 65 to 69 | 19.4% | 25.4% |

| 70 to 74 | 22.0% | 23.8% |

| 75 to 79 | 19.0% | 15.6% |

| 80 to 84 | 13.0% | 10.2% |

| 85 to 89 | 7.5% | 6.4% |

| 90 + | 4.5% | 4.7% |

| Female | 56.9% | 53.1% |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||

| White | 85.4% | 77.5% |

| Black | 9.4% | 9.0% |

| Asian | 1.3% | 3.2% |

| Other Race | 1.7% | 3.5% |

| Hispanic | 2.3% | 6.8% |

| Reason for Medicare Entitlement | ||

| Age >65 | 79.1% | 77.7% |

| Disability | 20.3% | 21.6% |

| ESRD | 0.3% | 0.4% |

| ESRD and Disability | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Non-Rural (Metro) Residence | 69.9% | 72.3% |

Abbreviations: end-stage renal disease (ESRD), interquartile range (IQR),

This Table shows the characteristics of Medicare beneficiaries included in our study sample in 2000 and 2019. We included all beneficiaries who were alive and had continuous enrollment in fee-for-service Medicare Parts A and B for a minimum of one year. All differences between the 2000 and 2019 beneficiary characteristics were statistically significant p<0.001.

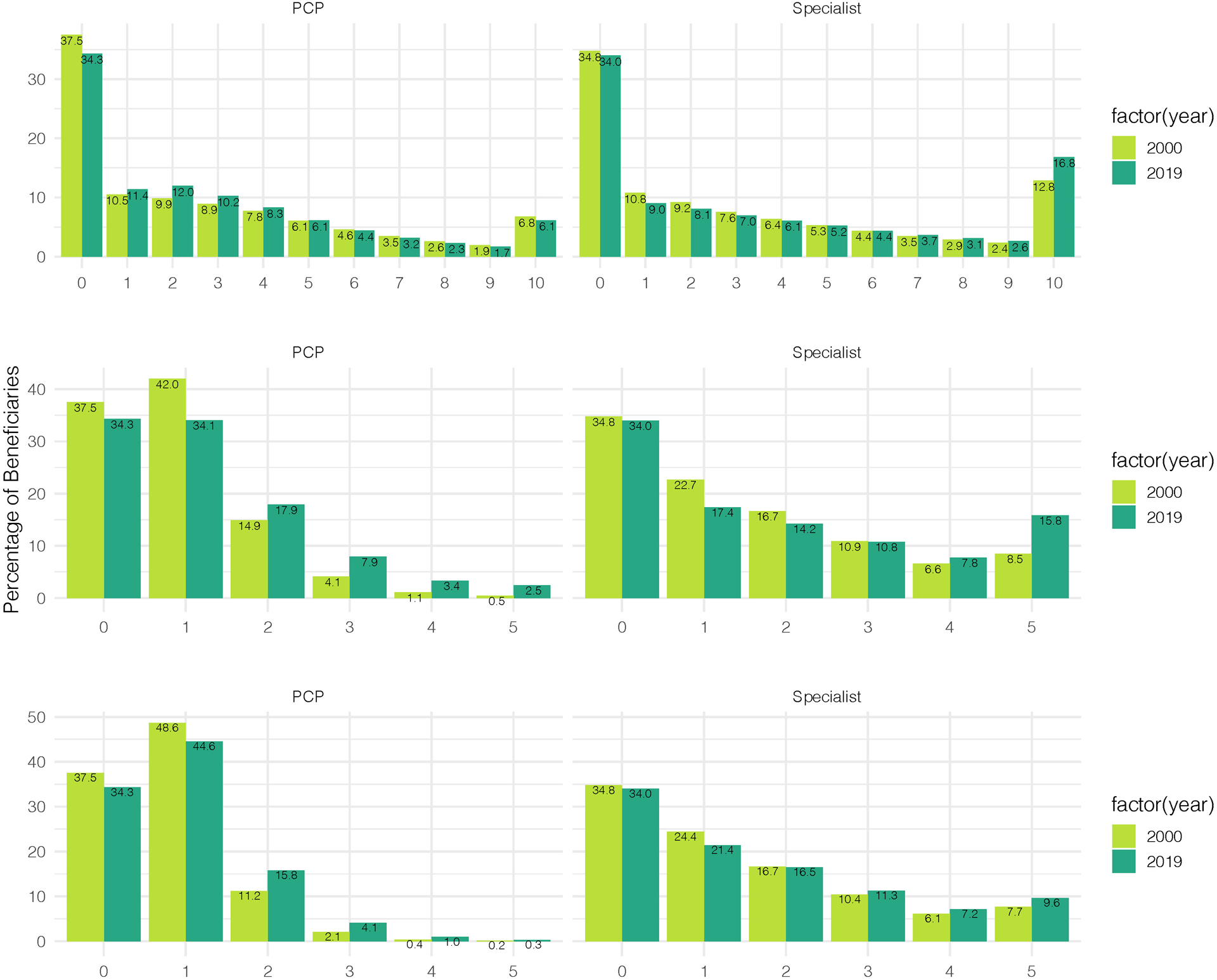

Office Visits with Primary Care and Specialist Physicians

Over the 20-year study period, the mean annual number of primary care office visits per Medicare beneficiary changed little from 2.99 in 2000 to 3.00, while the mean number of PCPs seen annually increased from 0.89 PCPs in 2000 to 1.21 PCPs in 2019 (36.0% increase) (Figure 1). The mean number of PCP practices seen (including those with zero practices) increased from 0.79 to 0.94 (19.2% increase) from 2000–2019. During the same period, visits to specialist physicians increased from 4.05 to 4.87 annually, a 20.3% increase, while the mean number of unique specialists seen increased 34.2% from 1.63 specialists in 2000 to 2.18 specialists in 2019. The mean number of specialist practices per beneficiary annually increased from 1.56 to 1.77 (13.3% increase) from 2000–2019.

Figure 1: Patterns of Primary and Specialty Outpatient Care Use by Medicare Beneficiaries in 2000 and 2019.

Panel A shows the annual mean number of office visits with either PCPs or specialist physicians per Medicare beneficiary in 2000–2019. Panel B shows the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries with any physician visit in 2000–2019. Panel C shows the annual mean number of distinct PCPs or specialists seen per Medicare beneficiary over the same period. Panel D shows the annual mean number of office visits with PCPs or specialists per Medicare beneficiary with any PCP or specialist visit, respectively, over the same period

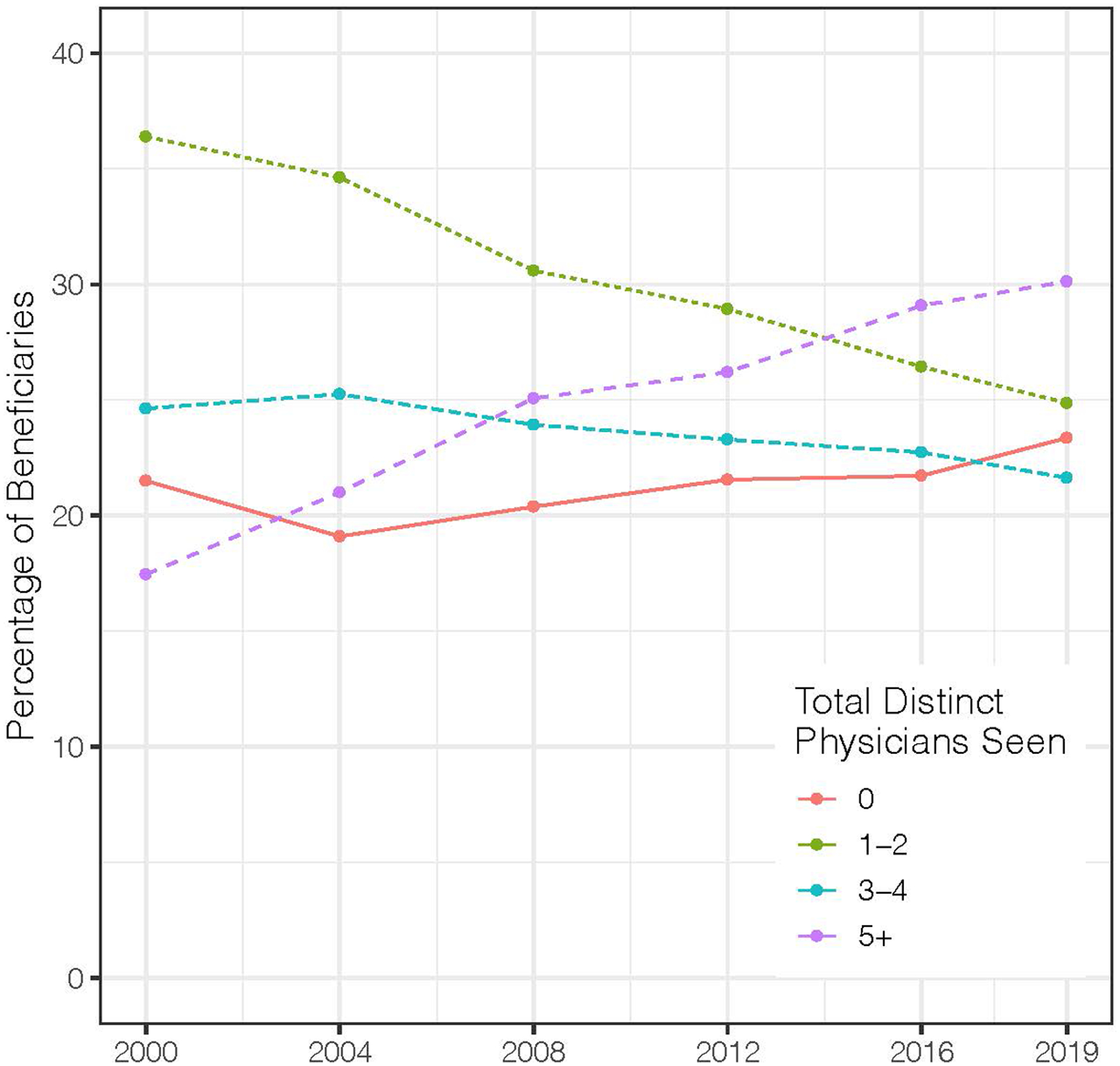

Integrating both PCP and specialist trends, we examined changes in the distribution of the total number of distinct physicians seen by beneficiaries annually (Figure 2). There was a small increase in the proportion of beneficiaries who had visits with no physician (20.1% in 2000 to 23.4% in 2019) while the proportion seeing 1–2 physicians (36.4% to 24.9%), or 3–4 physicians (24.6% to 21.6%) decreased. In contrast, there was a large increase in the proportion seeing 5 or more physicians annually (17.5% to 30.1%).

Figure 2: Number of Distinct Physicians Seen Annually by Medicare Enrollees, 2000–2019.

Figure shows the percentage of Medicare beneficiaries who saw 0, 1–2, 3–4 or 5+ distinct physicians (both PCPs and specialists) in 2000–2019.

The population averages in Figure 1 reflect a mixture of beneficiaries with no visits to physicians and those with one or more visits. During the study period there was only a modest increase in both the proportion of beneficiaries with any visit to a PCP (61.2% in 2000 to 65.7% in 2019). The proportion with any visit to a specialist increased from 63.7% in 2000 to 66.0% in 2019. These trends can be consistent with an increase in the proportion of beneficiaries with no physician visits annually, as seen in Figure 2, if by 2019, a higher proportion of those seeing any physician see both a PCP and a specialist each year over this period.

Among beneficiaries with any primary care office visit in a year, there was a small decrease in the number of primary care visits annually (4.90 in 2000 to 4.56 in 2019, −6.9% change), while the number of specialist visits among those with one or more specialty visits annually grew from 6.37 in 2000 to 7.38 in 2019, a 15.9% increase.

Office Visits Trends in Selected Beneficiary Subgroups

Black patients had fewer visits than White patients every year from 2000 (6.43 for Black vs. 7.25 for White patients) to 2019 (7.24 vs. 8.23), with a modest decrease in the disparity from 17.0% fewer total visits for Black vs. White patients in 2000 to 13.5% fewer in 2019 (Appendix Tables 1–2). The racial difference in annual visits was driven predominantly by a lower proportion of Black beneficiaries accessing any PCP or specialist care. For example, in 2019, 69.2% of White patients vs. 58.3% of Black patients saw any specialist (a relative disparity of 15.8% compared to 19.8% in 2000), however among those with at least one specialist visit, rates of specialist visits were higher among Black beneficiaries (7.60) than White beneficiaries (7.39). However, Black beneficiaries still had a 42.5% increase in the total number of distinct physicians seen annually from 2000 (2.08 physicians) to 2019 (2.96), larger than the 35.6% increase among White beneficiaries (2.65 to 3.60). The adjusted difference in outcomes between White and Black beneficiaries were either similar or larger in magnitude in models that controlled for regional fixed effects vs. models that did not (Appendix Results, Appendix Table 3). For example, the adjusted difference between White and Black beneficiary annual specialty care visits from 2000–2015 was −0.64 adjusting for age, race, sex, and disability, and −1.00 additionally adjusting for hospital referral region fixed effects.

Trends also differed between rural and non-rural beneficiaries. Rural beneficiaries had fewer primary care visits annually from 2000–2019 (3.00 to 2.72, −9.3% change), while the same rate grew slightly for non-rural beneficiaries (2.99 to 3.11, 3.8% change, Appendix Tables 4–5).

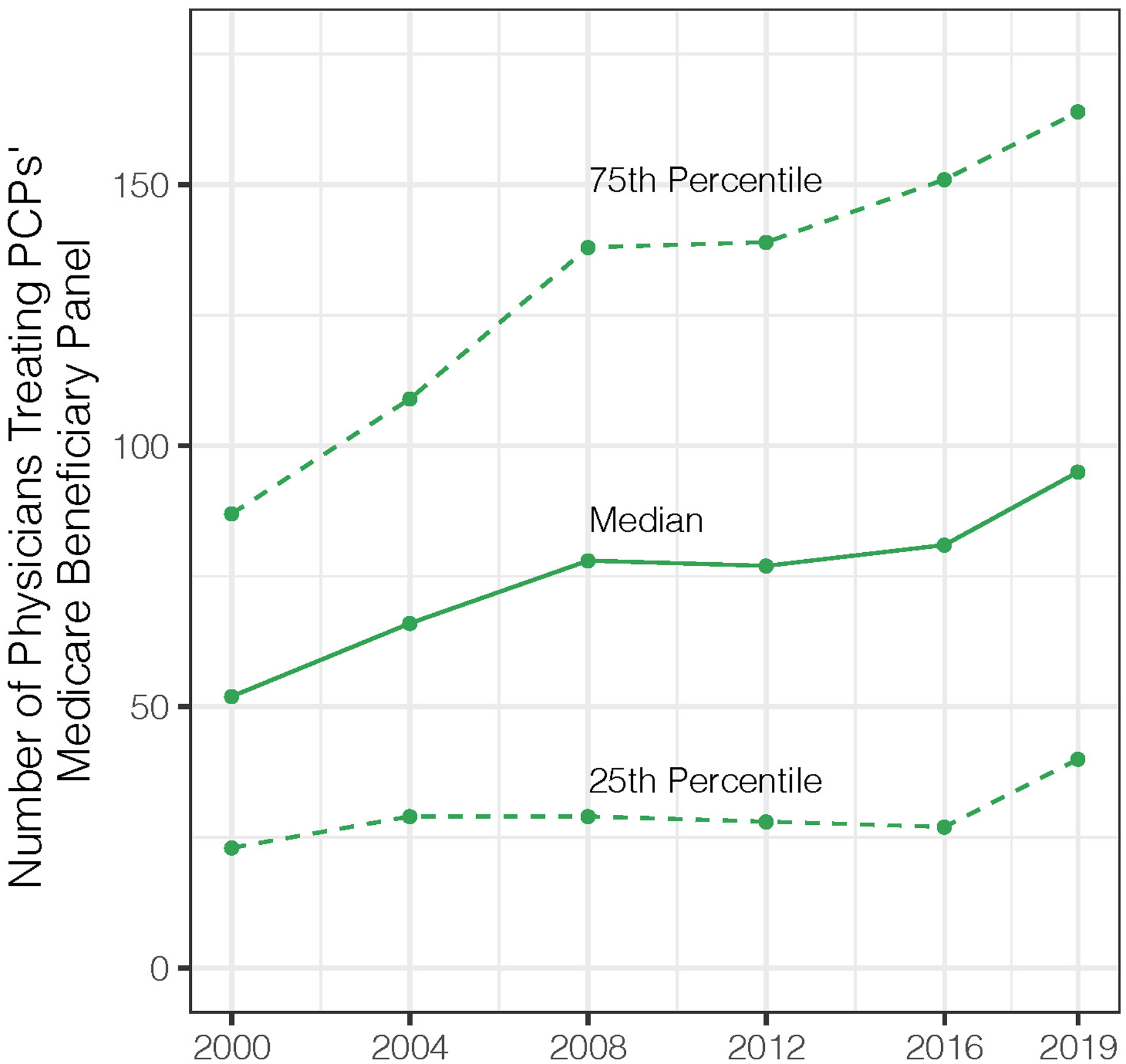

Trends in PCP Connections to Other Physicians

Tracking the number of other physicians seen annually by a PCP’s patients is one way to illustrate changes in the coordination burden for PCPs from outpatient care delivered to a PCP’s panel. In 2000, the median PCP’s Medicare beneficiary panel (among a 20% sample of patients) saw 52 other physicians (IQR 23–87, Figure 3). By 2019, this had grown to 95 (IQR 40–164), an increase of 83%, which was similar for physicians at the low and higher ends of this distribution.

Figure 3: Trends in Number of Physicians Treating a PCP’s Panel of Medicare Beneficiaries, 2000–2019.

Panels A (line graph) and B (bar chart) show trends in the number of physicians treating a PCPs’ Medicare panel from 2000–2019, the median and inter-quartile range (25th and 75th percentile). The bar chart is shown to illustrate the final difference over the 20-year period. The number of other physicians seen by a PCP’s assigned Medicare patients is calculated by taking the number of other physicians seen annually (i.e. billing an evaluation and management visit or procedure) by all beneficiaries assigned to each PCP. Because our study population is limited to a 20% sample of Medicare beneficiaries, our measure may underestimate the absolute number of other physicians that would be calculated using data on 100% of a physician’s panel. However, analysis of network sampling for physician patient-sharing networks has found that 20% samples can reliably identify this value in claims data.(28)

DISCUSSION

In this analysis of twenty years of data from Medicare, we observe substantial changes in patterns of care delivery for the average beneficiary. Medicare beneficiaries are receiving more specialist care from greater numbers of physicians with little change in contact with primary care. By 2019, beneficiaries had 20% more visits with 34% more specialists, while nearly one in three beneficiaries saw 5 or more physicians annually. In contrast, only 66% of Medicare beneficiaries had a visit with a PCP in 2019, the mean number of primary care visits per beneficiary was unchanged between 2000 and 2019, and even went down for those with at least one office visit. Collectively, these changes translated over the 20-year period into a substantial 83% increase in the total number of other physicians with whom PCPs must theoretically coordinate care for their Medicare panel, with 1/3 of Medicare beneficiaries not accessing a PCP to coordinate that care. This growth represents a shift toward a more specialty-oriented health care system, and a substantial expansion of the quantity and diversity of clinical care that PCPs (if they are available) must follow to understand their panel’s care.

These results also suggest that the work necessary to follow, understand, and coordinate the health care of a patient panel was a more complex and time-consuming task in 2019 than in 2000. The average PCP in 2019 must hypothetically interact with close to double the total number of specialists compared to two decades ago to understand the care received by their patients without any substantive change in the number of primary care encounters. While this analysis cannot answer whether the additional visits and physicians represent a net benefit to the overall health of older adults, it does shed light on the changing nature of primary care and the work required to manage patients’ scope of care longitudinally. PCPs likely have weaker and more distant relationships with a growing spread of specialist colleagues in the setting of increased time pressures that reduce face-to-face interactions(38) and substantial time spent on asynchronous contact through the electronic health record.(39)

There are several potential contributors to the trends we observe. First, as medical technology has advanced, so has the number of distinct medical subspecialties. In 1991, the American Board of Medical Specialties had 24 member specialty boards, with an additional 26 certified subspecialties.(40) By 2019, these same 24 specialty boards encompassed more than 150 separate subspecialties, not counting scores of other informal subspecialties.(40) Greater specialization reflects the growth of clinical knowledge and increasing complexity of clinical care over the past decades. For example, in the early 1990’s, only 14% of adults 65 and older took 5 or more drugs; by 2014, that had risen to 42%.(36) While greater subspecialization and seeing more specialists may provide health benefits, it necessarily contributes to care fragmentation without substantial investment in care coordination effort.

Second, the nature of shared responsibility in medical practice is changing over time. Medicine has become more commonly a “team” sport. For instance, it is increasingly common for primary care physicians to work in teams as a part of a medical home whereby clinicians provide care for each other’s patients.(41,42) Medical practices are also become larger over time as solo and small practices become less common.(43) Therefore, some of the additional physicians that beneficiaries see may be to other colleagues in the same clinic, or clinicians “cross covering” for their colleagues for urgent issues or during vacations. Such arrangements likely explain, for instance, why the number of distinct PCPs increased slightly despite fewer total visits to PCPs, and why the number of distinct PCPs and specialists seen grew faster than the number of distinct practices seen. As medical practices grow and physicians potentially work more proscribed hours (with some opting for part-time practice),(44) the likelihood that a patient will see more than one PCP in their practice increases over time. The rising workforce of nurse practitioners, who often share patients with a PCP,(45,46) also may contribute to an increase in the number of clinicians seen annually. Finally, a related issue is the relative decline in the availability and use of primary care across the United States, especially in rural areas. Between 2005 and 2015, the mean density of primary care physicians declined 46.6 to 41.4 per 100, 000 population, with greater declines in rural areas.(13) The fact that up to a third of Medicare beneficiaries do not see a PCP yearly in the most recent data suggests a significant lack of access to, or use of, primary care.

Our results also show that significant disparities in the use of physician services by the underserved populations we examined have changed little over two decades. In the case of Black patients, the major source of disparities in physician visits comes from a larger population with no office visits in a year, given that those who access any health care have similar or greater utilization compared to White patients. While on average, contact with physicians has increased for Black patients, the capacity of these underserved populations to access care more equitably has improved only modestly relatively to White beneficiaries over a twenty year period, yet these groups have still seen their care spread across more physicians.

Policies to bolster primary care, many of which have focused on risk-based payment models and medical home transformation, may be overlooking the challenge of sheer informational complexity across PCP’s panels, or for the specialists involved in these patients’ care, some of whom also must coordinate care across multiple providers. More physicians per patient implies that the time and resources necessary outside of office visits to coordinate care and integrate information from diagnostic and other testing are an ever-growing uncompensated obligation for primary care or the select few specialists who serve as PCPs for their patients.(47) This could weaken the ability of PCPs to provide proactive, coordinated, and comprehensive care for their panel of patients. One challenge is that, until very recently,(48) fee-for-service has remained the dominant payment model for outpatient care for the past 20 years, despite this increasing coordination complexity.(49) The fee-for-service payment system largely rewards physicians for providing care in the context of an office visit. Therefore, this system is a disincentive for PCPs to invest the time needed to coordinate care that has become increasingly complex as time invested in such activities detracts from time for revenue-generating office visits. One strategy that Medicare has adopted has been to add specific billing codes (e.g., chronic care management codes) to compensate physicians for this work, but uptake of these codes has been limited.(50,51) Modeling evidence suggests that instead these challenges may be best addressed by moving the majority of payment to more comprehensive, risk-adjusted, proactive population-based capitated payment models that do not disincentivize dedicating more time per patient outside of office visits.(52)

This study is subject to several limitations. First, our study sample is limited to patients with fee-for-service Medicare coverage. Therefore, these findings may not generalize to other populations. Second, our analysis is based on a 20% sample of Medicare patients. This means that our findings related to PCP degree are likely biased downward from the true number of other physicians seen by a PCPs panel. However, modeling studies suggest that this bias is relatively modest and, more importantly, it is consistent over time.(28) Therefore trends in this measure, rather than the absolute value, should not be biased. Third, our analysis is unable rule out the possibility that observed racial disparities within hospital referral region might reflect differences in the distribution of beneficiaries across smaller area geographic areas within the HRR, rather than a within-HRR effect.

In conclusion, we find that over the past 20 years, health care for Medicare beneficiaries is increasingly fragmented across multiple physicians, mostly specialists, with little change in annual engagement with primary care. These changes have resulted in a substantial expansion of the number of physicians providing care to a PCP’s panel of Medicare beneficiaries with no commensurate increase in PCP contact. The PCP task of care coordination and integrating information about the care received by the PCP’s patient panel has become substantially more complex in 2019 than in 2000 and may continue to do so. To improve system performance and respond to expanding care fragmentation, future policy reforms to primary care payment and delivery should account for evolving needs in the time and resources required to appropriately manage the ever-increasing complexity of medical care.

Supplementary Material

Primary Funding Source:

National Institute on Aging

Supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health (K23 AG058806-01 and P01 AG032952, BEL).

Footnotes

Reproducible Research Statement:

Statistical code: Available from Dr. Barnett (mbarnett@hsph.harvard.edu)

Data set: Available from the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services to qualified researchers.

REFERENCES

- 1.American College of Physicians. The impending collapse of primary care medicine and its implications for the state of the nation’s health care: a public policy report of the American College of Physicians [Internet]. 2006. [cited 2019 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.acponline.org/acp_policy/policies/impending_collapse_of_primary_care_medicine_and_its_implications_for_the_state_of_the_nation%E2%80%99s_health_care_2006.pdf

- 2.Sandy LG, Bodenheimer T, Pawlson LG, Starfield B. The Political Economy Of U.S. Primary Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2009. July 1;28(4):1136–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodenheimer T, Grumbach K, Berenson RA. A Lifeline for Primary Care. N Engl J Med. 2009. June 25;360(26):2693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodenheimer T Coordinating care--a perilous journey through the health care system. N Engl J Med. 2008. March 6;358(10):1064–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnett ML, Song Z, Landon BE. Trends in physician referrals in the United States, 1999–2009. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(2):163–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Detsky AS, Gauthier SR, Fuchs VR. Specialization in Medicine: How Much Is Appropriate? JAMA. 2012. February 1;307(5):463–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cassel CK, Reuben DB. Specialization, Subspecialization, and Subsubspecialization in Internal Medicine. N Engl J Med. 2011. March 24;364(12):1169–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2017: Table 77. Visits to primary care generalist and specialty care physicians, by selected characteristics and type of physician: United States, selected years 1980–2013 [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 20]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hus/2016/077.pdf

- 9.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health Care Spending in the United States and Other High-Income Countries. JAMA. 2018. March 13;319(10):1024–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Starfield B Is primary care essential? The Lancet. 1994. October 22;344(8930):1129–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitton A, Ratcliffe HL, Veillard JH, Kress DH, Barkley S, Kimball M, et al. Primary Health Care as a Foundation for Strengthening Health Systems in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. J Gen Intern Med. 2017. May 1;32(5):566–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of Primary Care Physician Supply With Population Mortality in the United States, 2005–2015. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2019. February 18 [cited 2019 Feb 18]; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2724393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Pham H, O’Malley A, Bach P, Saiontz-Martinez C, Schrag D. Primary care physicians’ links to other physicians through Medicare patients: the scope of care coordination. Ann Intern Med. 2009. February 17;150(4):236–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agha L, Ericson KM, Geissler KH, Rebitzer JB. Team Formation and Performance: Evidence from Healthcare Referral Networks [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2018. February [cited 2018 Jul 16]. Report No.: 24338. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w24338 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pham H, Schrag D, O’Malley A, Wu B, Bach P. Care patterns in Medicare and their implications for pay for performance. N Engl J Med. 2007. March 15;356(11):1130–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Proposed Policy, Payment, and Quality Provisions Changes to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for Calendar Year 2020 | CMS [Internet]. [cited 2019 Aug 6]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/proposed-policy-payment-and-quality-provisions-changes-medicare-physician-fee-schedule-calendar-year-2

- 18.CMS. Comprehensive Primary Care Plus | CMS Innovation Center [Internet]. 2021. [cited 2021 Mar 22]. Available from: https://innovation.cms.gov/innovation-models/comprehensive-primary-care-plus

- 19.NP Fact Sheet [Internet]. American Association of Nurse Practitioners. [cited 2019 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants, Inc. 2018 Statistical Profile of Certified Physician Assistants: An Annual Report of the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants [Internet]. 2019. [cited 2019 Jun 13]. Available from: http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPhysiciaAssistants.pdf

- 21.DuGoff EH, Walden E, Ronk K, Palta M, Smith M. Can Claims Data Algorithms Identify the Physician of Record? Med Care. 2017. March 17; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shah BR, Hux JE, Laupacis A, Zinman B, Cauch-Dudek K, Booth GL. Administrative data algorithms can describe ambulatory physician utilization. Health Serv Res. 2007. August;42(4):1783–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Revisions to Consultation Services Payment Policy – JA6740 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Contracting/ContractorLearningResources/Downloads/JA6740.pdf

- 24.MLN Matters: Annual Wellness Visit (AWV), Including Personalized Prevention Plan Services (PPPS) [Internet]. [cited 2020 Dec 3]. Available from: https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNMattersArticles/downloads/MM7079.pdf

- 25.Barnett ML, Christakis NA, O’Malley J, Onnela J-P, Keating NL, Landon BE. Physician Patient-sharing Networks and the Cost and Intensity of Care in US Hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50(2):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Landon B, Keating N, Barnett M, Onnela J, Paul S, O’Malley A, et al. Variation in patient-sharing networks of physicians across the United States. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2012;308(3):265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Landon BE, Keating NL, Onnela J-P, Zaslavsky AM, Christakis NA, O’Malley AJ. Patient-Sharing Networks of Physicians and Health Care Utilization and Spending Among Medicare Beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2018. 01;178(1):66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O’Malley AJ, Onnela J, Keating NL, Landon BE. The impact of sampling patients on measuring physician patient‐sharing networks using Medicare data. Health Serv Res [Internet]. 2020. October 14 [cited 2020 Dec 7]; Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/1475-6773.13568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Jarrín OF, Nyandege AN, Grafova IB, Dong X, Lin H. Validity of Race and Ethnicity Codes in Medicare Administrative Data Compared With Gold-standard Self-reported Race Collected During Routine Home Health Care Visits. Med Care. 2020. January;58(1):e1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UW RHRC Rural Urban Commuting Area Codes - RUCA [Internet]. [cited 2021 Jun 14]. Available from: http://depts.washington.edu/uwruca/index.php

- 31.Geruso M, Layton T. Upcoding: Evidence from Medicare on Squishy Risk Adjustment [Internet]. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2015. May [cited 2019 Sep 1]. Report No.: 21222. Available from: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21222 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Song Y, Skinner J, Bynum J, Sutherland J, Wennberg JE, Fisher ES. Regional Variations in Diagnostic Practices. N Engl J Med. 2010. July 1;363(1):45–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Finkelstein A, Gentzkow M, Williams H. Sources of Geographic Variation in Health Care: Evidence From Patient Migration. Q J Econ. 2016. November 1;131(4):1681–726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019. October 25;366(6464):447–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim AM, Dimick JB, Sinha SS, Hollingsworth JM, Nuliyalu U, Ryan AM. Association of Coded Severity With Readmission Reduction After the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. JAMA Intern Med [Internet]. 2017. November 13 [cited 2017 Nov 27]; Available from: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2663252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 36.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2016: With Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health. Hyattsville (MD); 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Atlases & Reports - Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care [Internet]. [cited 2018 Mar 17]. Available from: http://www.dartmouthatlas.org/publications/reports.aspx

- 38.Prasad K, Poplau S, Brown R, Yale S, Grossman E, Varkey AB, et al. Time Pressure During Primary Care Office Visits: a Prospective Evaluation of Data from the Healthy Work Place Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2020. February 1;35(2):465–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Overhage JM, McCallie D. Physician Time Spent Using the Electronic Health Record During Outpatient Encounters. Ann Intern Med. 2020. January 14;172(3):169–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dalen JE, Ryan KJ, Alpert JS. More Sub-Subs Are Coming! Am J Med. 2019. February 1;132(2):132–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hing E, Kurtzman E, Lau DT, Taplin C, Bindman AB. Characteristics of Primary Care Physicians in Patient-centered Medical Home Practices: United States, 2013. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2017. February;(101):1–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bitton A, Martin C, Landon B. A nationwide survey of patient centered medical home demonstration projects. J Gen Intern Med. 2010. June 1;25(6):584–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neprash HT, McWilliams JM, Chernew ME. Physician Organization and the Role of Workforce Turnover. Ann Intern Med. 2020. April 21;172(8):568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Staiger DO. Trends in the Work Hours of Physicians in the United States. JAMA. 2010. February 24;303(8):747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Auerbach DI, Buerhaus PI, Staiger DO. Implications Of The Rapid Growth Of The Nurse Practitioner Workforce In The US. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020. February 1;39(2):273–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barnes H, Richards MR, McHugh MD, Martsolf G. Rural And Nonrural Primary Care Physician Practices Increasingly Rely On Nurse Practitioners. Health Aff (Millwood). 2018. June 1;37(6):908–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards ST, Mafi JN, Landon BE. Trends and quality of care in outpatient visits to generalist and specialist physicians delivering primary care in the United States, 1997–2010. J Gen Intern Med. 2014. June;29(6):947–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.CPT® Evaluation and Management [Internet]. American Medical Association. [cited 2021 Feb 24]. Available from: https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/cpt/cpt-evaluation-and-management [Google Scholar]

- 49.Landon BE. A Step toward Protecting Payments for Primary Care. N Engl J Med. 2019. February 7;380(6):507–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, Landon BE. Adoption of Medicare’s Transitional Care Management and Chronic Care Management Codes in Primary Care. JAMA. 2018. December 25;320(24):2596–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Agarwal SD, Barnett ML, Souza J, Landon BE. Medicare’s Care Management Codes Might Not Support Primary Care As Expected. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020. May 1;39(5):828–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Basu S, Phillips RS, Song Z, Bitton A, Landon BE. High Levels Of Capitation Payments Needed To Shift Primary Care Toward Proactive Team And Nonvisit Care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017. September 1;36(9):1599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.