Abstract

Spending time in nature is associated with numerous mental health benefits, including reduced depression and improved well-being. However, few studies examine the most effective ways to nudge people to spend more time outside. Furthermore, the impact of spending time in nature has not been previously studied as a postpartum depression (PPD) prevention strategy. To fill these gaps, we developed and pilot tested Nurtured in Nature, a 4-week intervention leveraging a behavioral economics framework, and included a Nature Coach, digital nudges, and personalized goal feedback. We conducted a randomized controlled trial among postpartum women (n = 36) in Philadelphia, PA between 9/9/2019 and 3/27/2020. Nature visit frequency and duration was determined using GPS data. PPD was measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). Participants were from low-income, majority Black neighborhoods. Compared to control, the intervention arm had a strong trend toward longer duration and higher frequency of nature visits (IRR 2.6, 95%CI 0.96–2.75, p = 0.059). When analyzing women who completed the intervention (13 of 17 subjects), the intervention was associated with three times higher nature visits compared to control (IRR 3.1, 95%CI 1.16–3.14, p = 0.025). No significant differences were found in the EPDS scores, although we may have been limited by the study’s sample size. Nurture in Nature increased the amount of time postpartum women spent in nature, and may be a useful population health tool to leverage the health benefits of nature in majority Black, low-resourced communities.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11524-021-00544-z.

Keywords: Maternal health, Greenspace/nature, Postpartum depression, Behavioral economics, Digital health, GPS, Community health worker, Intervention

Introduction

Spending time in nature is associated with numerous mental and physical health benefits, including reduced depression and improved well-being [1–4]. A large cross-sectional population study demonstrated that visits to greenspace of 30 min per week could reduce depression prevalence in the general population by 7% [5]. Similarly, in a randomized trial, vacant lot greening in low-resourced urban neighborhoods led to reduced feelings of depression for nearby residents [6].

The recent ParkRx movement involves physicians prescribing time outside to their patients to take advantage of the numerous health benefits associated with nature [7]. However, little is known about the most effective ways to nudge people outdoors to nature near their homes [8]. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of park visits, conducted by a pediatrician office, found that both an intervention involving text reminders and free transportation and control group families who reported spending more time outside also reported reduced stress [9, 10]. Another RCT of adults found that weekly group exercise sessions in parks lead to increased park use [11]. Additionally, the effort to connect patients to nature has primarily taken place within pediatrics, and horticulture therapy among adults has taken place primarily in supervised in-patient settings [12]. Efforts to connect adults in predominantly Black neighborhoods to nature in their communities or efforts within women’s health are lacking.

Given these gaps in the literature, we developed and pilot tested Nurtured in Nature, an intervention designed to increase the amount of time postpartum women from predominantly Black neighborhoods spend outside in nearby nature. The ultimate goal is to prevent a mental health complication of pregnancy—postpartum depression (PPD). Almost 5% and 13% of women experience a major or minor PPD episode respectively in the first 3 months following pregnancy, making PPD one of the most common complications of childbearing [13, 14].

Consequences of PPD include impaired functioning for the woman, hindered infant-parent bonding, harmful effects on the infant’s cognitive and social-emotional development, and relational discord [15]. While the largest risk factor for PPD is a prior history of depression, social risk factors including low socioeconomic status, stress during pregnancy, and low social support are also implicated [13, 16]. As a result, interventions that buffer against these social risk factors, such as spending time in nature, are important in the prevention of PPD. [17] In fact, two mechanisms linking nature and health are reduced stress and increased social connectedness, both of which are demonstrated to mitigate PPD. [1]

Nurtured in Nature was designed with a behavioral economics framework, leveraging both a community health worker (Nature Coach) and Global Positioning System (GPS)–enabled smartphone technology to influence behavior. Behavioral economics uses predictable patterns in human decision-making to overcome barriers to healthy behavior change. Both behavioral economics concepts and community health workers have been used successfully in promoting positive health behaviors such as physical activity, healthy eating, and reduced smoking, but have not been previously studied as a way to influence how much time people spend in nature [18, 19]. In this pilot trial, our primary outcome was time spent in greenspace, and secondary outcome was postpartum depression. We also analyzed field notes from the Nature Coach to provide context to successes and challenges in deploying the intervention.

Methods

Study Design

Nurtured in Nature was a pilot randomized controlled trial conducted among postpartum women in Philadelphia, PA. The study was conducted between September 9, 2019, and March 27, 2020, and consisted of enrollment within 48 h of birthing, a 4-week intervention period taking place approximately 2–6 weeks postpartum, and a 12-week follow-up period. The University of Pennsylvania institutional review board approved this trial, which was registered on clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04146025). Free and informed consent were obtained from all participants and there was no racial bias in the selection of participants. The study was conducted using Way to Health (W2H), a web-based research platform at the University of Pennsylvania previously used for behavioral intervention trials [20–22]. W2H was used to randomize participants, conduct surveys, and communicate with participants via two-way text messaging.

Participant Enrollment and Randomization

Study enrollment occurred on the postpartum unit of a large, tertiary hospital. Women were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age, birthed a live term infant (37 weeks gestational age or greater), owned a smartphone, and were English proficient. Additionally, because we were interested in enrolling participants from lower-resourced, minority neighborhoods, we restricted enrollment to women living in the 7 zip codes surrounding the hospital, which are 89.9% Black with a median household income of $17,427 [23]. Exclusion criteria included an intensive care unit (ICU) stay for either woman or child and an open case with the Department of Human Services (DHS). Additionally, women had to be willing to spend time in nature during the first 6 postpartum weeks.

Eligible and interested participants provided written informed consent and answered basic demographic questions. The research coordinator delivered a 10-min educational session about the health benefits of nature (see below). Participants were then randomly assigned to either the control group (education only) or the intervention group (education + Nurtured in Nature) through W2H. If the participant was randomized to the intervention group, a home visit was scheduled for approximately 2 weeks postpartum. All participants had a global positioning system (GPS) app, AWARE, installed on their smartphone [24].

Educational Session

The brief educational session was designed to teach participants about the evidenced-based health benefits of nature, including decreased stress, improved mood, and strengthened relationships [25–27]. Participants were encouraged to spend time outside during daylight hours and choosing a location they felt safe. The coordinator discussed activities that could be done while in nature, including reading, walking, listening to music, relaxing, and gardening. All participants received a flyer summarizing the content of the educational session (see Supplement Figure 1).

Intervention: Nurtured in Nature

Nurtured in Nature, guided by insights from behavioral economics, included an initial in-person component (Nature Coach), followed by reinforcement with a personalized digital component [22]. The Nature Coach was a Black woman from the same community as many of the participants, and had experience as a community health advocate. The Nature Coach was trained by the study PI (ES) on how to handle special events (e.g., suicidal ideation/intention, child abuse, or neglect). The Nature Coach did not provide any medical advice to the participants.

The Nature Coach had 3 touchpoints with each participant: a home visit (intervention day 1), a park visit (~ intervention day 8), and a phone call check-in (~ intervention day 15). Prior to the home visit, the Nature Coach used a map, online resources, and personal knowledge to identify 4–5 nature locations within a 10-min walk of each participant’s home. Nature locations were primarily parks, but also included greened vacant lots and greened school yards.

During the 1-h home visit, the Nature Coach (a) reviewed the health benefits of nature, (b) used a personalized map to show the participant potential nature locations in relationship to their home, (c) reviewed weekly nature goals (one visit for weeks 1 and 2, and two visits for weeks 3 and 4), (d) helped participant brainstorm and write down potential barriers and solutions to reaching those goals, and (e) completed a pre-commitment contract based on individualized nature targets and weekly goals. The Nature Coach encouraged participants to come up with barriers and solutions, but was also prepared with a predetermined list to review as needed. This list included potential barriers associated with having a newborn (e.g., would the child go on the nature visit and if so, what baby supplies would need to be packed; if the child was to stay home, who would watch the child). The Nature Coach also shared a resource list about where to seek emotional support at the University of Pennsylvania.

A week later, the Nature Coach met the participant at a park of her choice, with the goal of modeling the desired behavior of spending time outside in nearby nature. The park visit served as a check-in regarding spending time outside and the Nature Coach reviewed what barriers had come up and helped the participant brainstorm solutions. Finally, the Nature Coach called the participant at the mid-way point of the intervention to check in on progress, review barriers that had come up, and help brainstorm solutions. After each visit with participants, the Nature Coach recorded field notes describing the encounter and her perception of the participant’s level of engagement.

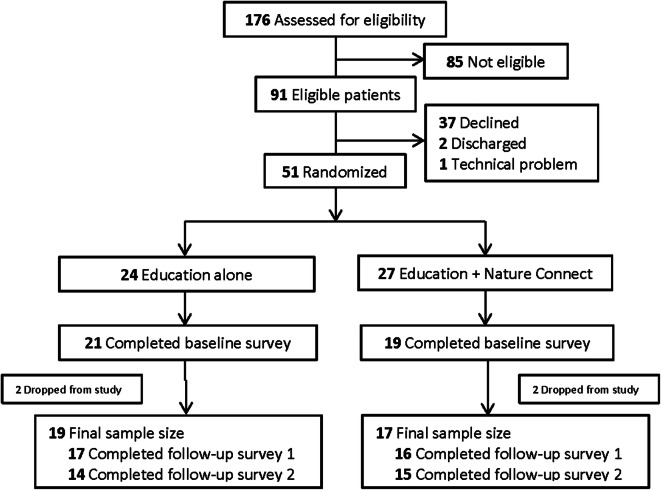

The digital component of Nurtured in Nature included personalized nudges and goal feedback, both delivered weekly via text message through the W2H platform, for 4 weeks. Nudge texts served as reminders of goals set with the Nature Coach, as well as encouragement to meet those goals. The context of text messages changed slightly each week and was individualized based on the parks selected by the participant. A sample text was “Good morning Sharrie. We hope you had a great visit with your Nature Coach. You set a goal to spend time outside at least once this week. Today would be a great day to visit Stony Park, Brook Park, and Pickwick Park. Listen to music or just sit and enjoy nature. Spending time outside is great for your health!” (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sample text messages sent to participants. The top message shows a typical weekly nudge, while the bottom message shows a typical progression badge. The progression badge was a visual representation of how much time the participant spent in greenspace that week compared to the weekly goal. Greenspace visits were counted using GPS data from participants’ phone. Study: Nurtured in Nature, Philadelphia, PA, 9/2019-3/2020

Goal feedback texts were sent in the form of a progression badge at the end of each intervention week and included a visual representation of the number of actual visits the participant made to greenspace compared to the weekly goal. Greenspace visits were measured using AWARE, a GPS platform installed on each participant’s phone (see below). One of three feedback messages were sent along with the progression badge: “Try again next week” if they did not meet their goal; “You did it!” if they met their goal; and “Wow, great job!” if they exceeded their goal (see Fig. 1).

All participants were sent surveys via text messages at 3 time points after enrollment—10 days (baseline), 6 weeks (follow-up 1), and 3 months (follow-up 2). Participants were compensated a total of $50 for their participation in the form of a Greenphire Clincard debit card [28]. Participants received $5 after enrollment, $10 after completion of the baseline survey, and $15 and $20 after completion of the 2 follow-up surveys, respectively.

Study Outcomes

Our primary outcome was time in greenspace—total minutes and number of visits—measured using smartphone GPS data. A data collection app from the AWARE Framework system was installed on each participant’s mobile phone, with her permission. In the background, the app collected and stored the geographic location of the participant’s phone every 3 min. This data was synchronized with our AWARE Framework web server, hosted on Amazon Web Services (AWS) each day. Participants were identified using a unique AWARE ID. No PHI or health-related information was stored on AWS. Inside the institutional firewall, we created an automated system to transfer and analyze the GPS data for our primary outcome of interest (see Technical Appendix A1 for further detail).

Subject GPS data was combined with a Philadelphia city-wide greenspace Geographic Information System (GIS) layer we created using ArcGIS Pro 2.5 and ArcMap 10.6.1, utilizing publicly available spatial data. On the merged greenspace polygon layer, a 90-foot buffer was created around each greenspace to account for potential minor inaccuracy of GPS data. All subject GPS data points located within the greenspace layer and buffer were examined for accuracy and speed to exclude car travel and unreliable readings. Remaining points with 2 or more consecutive readings in the same greenspace were counted as greenspace exposures. All exposures that remained were manually checked against Google Street View and aerial imagery to ensure they truly represented greenspace usage (see Technical Appendix A2 for more detail).

Our secondary outcome, PPD, was measured using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), a 10-item depression screening questionnaire [29]. Using a 4-point scale (0–3), participants were asked to rate how often they felt specific depression symptoms in the previous 7 days. A score of 10 or greater suggests potential PPD and indicates that further screening is warranted. If participants answered “Yes” to the statement: “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me,” the principal investigator was alerted and the participant was contacted and referred to their doctor. This occurred one time during the course of the study.

Finally, given that this was a pilot study, we were interested in understanding the barriers and facilitators for implementing the intervention and for participants to engage with the intervention and spend time in nature. The Nature Coach spent the most time in neighborhoods and had the most direct contact with participants. As such, we aimed to capture the Nature Coach’s experience through free text notes and reflections after each attempted and completed home visit. The Nature Coach was instructed to describe a range of aspects of each attempted visit including participants’ motivating factors for engaging with greenspaces, personal hurdles and prior knowledge, and barriers to completion of the home visit.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the primary and secondary outcomes was conducted on the subset of consented participants who completed the baseline survey. Cohort summary statistics were calculated to describe the participants and assess randomization. Continuous variables were compared using either Student’s or the Welsh two-sample t-test. Categorical variables were compared using a chi-squared analysis, except when cell counts were very small, and then Fisher’s exact test was performed. Data management and analysis was conducted in R version 4.0.2 (R Core Team, Vienna Austria).

Analysis of the primary outcomes—total minutes in and total visits to greenspaces—was conducted using a negative binomial regression for count data. Analysis was conducted using an intention-to-treat (ITT) methodology, as well as an as-treated (AT) analysis comparing those who actually received the intervention to the control arm. Total greenspace visit times and unique visits to greenspace were aggregated across the 4-week intervention period.

For the secondary outcome, EPDS scores were compared between study arms utilizing the Mann-Whitney U test. Additionally, change in scores between baseline and final follow-up were calculated for each participant and then analyzed in the same fashion. One author (MJ) analyzed the Nature Coach’s daily field notes in the chronological order in which they were collected. Key rudimentary codes were created to identify salient themes around barriers and facilitators to successful Nature Coach-participant interaction, as well as Nature Coach perception of participant barriers and facilitators to completing park visits. Codes and themes were reviewed with the PI (ES) to create final themes presented in the paper.

Results

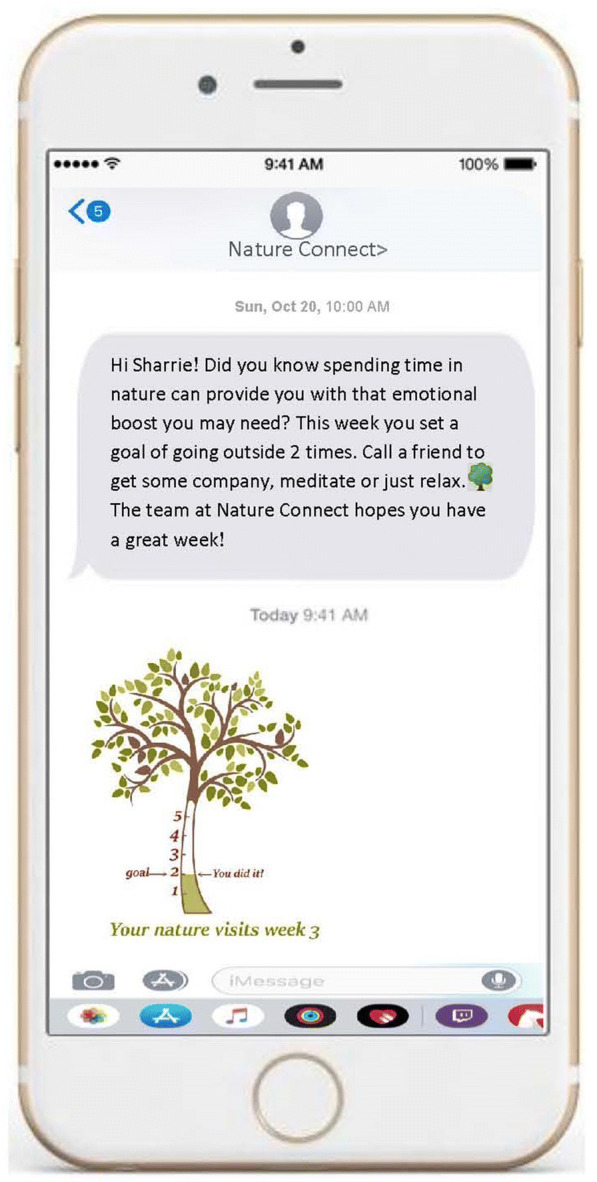

Of the 176 patients screened, 85 were ineligible (Fig. 2). Of the 91 remaining, 51 (56%) provided written informed consent, were randomized, and received the educational program. Fifteen were lost to follow-up (11 did not complete the initial baseline survey, 2 were no longer interested in the study, and 2 had technical problems with the AWARE app), and thus excluded from the analysis following randomization. Our final analysis cohort included 17 women in the intervention arm and 19 in the control arm. Randomization was effective with no significant differences in demographic variables, with the exception of self-reported income (Table 1). In the final cohort, the mean age was 28 ± 6 years, the majority (69%) were Black, and 5.6% were Hispanic/Latinx. Women in the study reported living in their current ZIP code for a median of 2 [IQR 1, 14.5] and 3 [IQR 1, 8] years in the control and intervention groups, respectively. Age, race, income, and education were not significantly different between those who completed the intervention and those who were assigned to the intervention group but did not complete the intervention. Some participants in both arms had limited (defined as missing 15 days or more) GPS data recorded, but this difference was not statistically significant between the arms (6 control vs 3 intervention, p = 0.28).

Fig. 2.

Consort chart showing flow of participants through the study. Study: Nurtured in Nature, Philadelphia, PA, 9/2019-3/2020

Table 1.

Baseline demographic characteristics for participants by arm and by intervention complete or not complete

| Characteristic | No. (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 19) | Intervention (n = 17) | p value | Intervention complete (n = 13) | Intervention not complete (n = 4) | p value | |

| Age, mean (SD), y | 28.63 (5.79) | 27.94 (5.89) | 0.725 | 27.85 (5.76) | 28.25 (7.23) | 0.909 |

| Sex (female) | 19 (100.0) | 17 (100.0) | N/A | 13 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | N/A |

| Race/ethnicity * | ||||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 3 (15.8) | 2 (11.8) | 1 | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 13 (68.4) | 10 (58.8) | 0.73 | 7 (53.8) | 3 (75.0) | 0.603 |

| Asian, non-Hispanic | 1 (5.3) | 2 (11.8) | 0.92 | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Hispanic, Black | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.9) | 1 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (25.0) | 0.52 |

| Other | 2 (10.5) | 2 (11.8) | 1 | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 5 (26.3) | 9 (52.9) | 0.171 | 9 (69.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.029 |

| Single (never married) | 14 (73.7) | 8 (47.1) | 4 (30.8) | 4 (100.0) | ||

| Education | ||||||

| Less than high school diploma | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0.887 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 |

| High school degree or GED equivalent | 11 (57.9) | 8 (47.1) | 6 (46.2) | 2 (50.0) | ||

| Some college | 3 (15.8) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 2 (10.5) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Master’s degree | 1 (5.3) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Doctorate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Full time (40+ hours) | 9 (47.4) | 10 (58.8) | 0.069 | 7 (53.8) | 3 (75.0) | 0.622 |

| Part time (up to 39 hours) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (17.6) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Unemployed | 8 (42.1) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| On disability/unable to work | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Other | 1 (5.3) | 2 (11.8) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Income | ||||||

| Less than $15,000 | 7 (36.8) | 1 (5.9) | 0.007 | 1 (7.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.894 |

| $15,000 to $24,999 | 3 (15.8) | 3 (17.6) | 2 (15.4) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| $25,000 to $34,999 | 4 (21.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| $35,000 to $44,999 | 0 (0.0) | 2 (11.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| $45,000 or greater | 5 (26.3) | 7 (41.2) | 6 (46.2) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Don’t know | 0 (0.0) | 4 (23.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) | ||

| Household size, median [IQR] | 4 [3, 4.5] | 4 [3, 5] | 0.423 | - | - | - |

| Years in home, median [IQR] | 1 [0, 2] | 1 [1, 5] | 0.913 | - | - | - |

| Years in zip code, median [IQR] | 2 [1, 14.5] | 3 [1, 8] | 0.666 | - | - | - |

Study: Nurtured in Nature, Philadelphia, PA, 9/2019–3/2020

SD standard deviation, IQR interquartile range

*Participants could identify as more than one race

In the primary ITT analysis, the intervention arm was associated with higher rates of both total visits and minutes spent in greenspace; however, neither reached statistical significance (see Table 2). Thirteen of 17 subjects assigned to the intervention arm completed the home visit with the Nature Coach, while 4 women did not. All of these women were initially interested and scheduled a home visit, but some cited issues of fatigue and an irregular schedule with the baby as challenges to participation. When restricted to the 13 women who received the intervention (as treated), the intervention was associated with a three times higher rate of visits to nature compared to the control group (IRR 3.1, 95%CI 1.16–3.14, p = 0.025). Furthermore, those who completed the intervention spent over four times as long in nature compared to the controls (IRR 4.5, 95%CI 0.74–30.5, p = 0.092). No significant differences were found in EPDS scores (Supplemental Table 1).

Table 2.

Number of visits and total minutes in greenspace during the 4-week intervention period

| Outcome measures (median [IQR]) | Intention-to-treat | As treated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 16)a | Intervention (n = 17) | Incidence rate ratio (IRR [95%CI]) | p value | Received interventionb (n = 13) | Incidence rate ratio (IRR [95%CI]) | p value | |

| Number of visits in greenspace | 0 [0, 1.25] | 3 [0, 4] | 2.6 [0.96–2.75] | 0.059 | 3 [1, 5] | 3.1 [1.16–3.14] | 0.025 |

| Number of minutes in greenspace | 0 [0, 20] | 66 [0, 206] | 3.6 [0.61–21.1] | 0.132 | 102 [27, 238] | 4.5 [0.74–30.5] | 0.092 |

Boldface indicates statistical significance

a3 women not included in this analysis who were missing GPS data

bWomen who received the intervention (13/17 in intervention group) completed a home visit with the Nature Coach and received personalized nudges and goal feedback

Study: Nurtured in Nature, Philadelphia, PA, 9/2019–3/2020

Several themes emerged from the Nature Coach field notes analysis regarding factors that promoted or inhibited participant involvement in the intervention and with park visits: communication barriers, level of participant interest in engaging with nature, postpartum physical and mental health symptoms, level of social support to complete nature visits, and neighborhood conditions and safety (Supplement Table 2). Communication barriers were a salient aspect of the ability of the Nature Coach to schedule and complete the home visit, including difficulty reaching women by phone. Interest in spending time outside ranged from excitement to ambivalence. The Nature Coach reported that women who expressed ambivalence about spending time in nature during the home visit were still willing to try as an opportunity to relax. The Nature Coach reported that some participants noted physical symptoms related to the birthing process as barriers to spending time outdoors, while those who reported mental health symptoms seem to perceive spending time in nature as a buffer against their symptoms. The Nature Coach noted that participants’ perceived level of social support was a principal barrier or facilitator to spending time out of the home. Finally, perceptions of neighborhood safety were concerns for some participants. Some noted either a paucity of greenspaces, or reported being previously unaware of nearby greenspaces introduced by the Nature Coach.

Discussion

In a sample of predominantly Black postpartum women living in low-resourced neighborhoods, the Nurtured in Nature intervention led to a significant increase in the number of nature visits and a strong trend toward more total minutes spent in greenspace for those randomized to the 4-week intervention period. Our results were the strongest for women who completed the intervention. We did not find a relationship between the intervention and changes in EPDS score, although we may have been limited by the study’s sample size.

To our knowledge, this is the first trial of an intervention designed to increase time in nature for postpartum women, adding needed experimental evidence to the growing movement within healthcare to connect people with nature to improve health outcomes [30]. A recent review demonstrated just a handful of existing studies of park prescription programs, most taking place among children, and few rigorous RCT designed studies [8]. Only two studies have demonstrated a change in nature contact, both limited by reliance of self-report [11, 31].

There are several unique strengths to the study. First, we use an objective measure of greenspace use—GPS—rather than relying on subjective recall. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first nature contact study to use GPS data. Second, we were also able to use this data in real time to offer feedback to participants as part of one of the behavioral economics strategies of the intervention.

Third, our intervention integrated insights from both the impact that community health workers have had on improving the health of minority and low-income populations, as well as the science of behavioral economics. Our Nature Coach shared life experiences with many of the women in our study, and was able to build rapport quickly in laying the foundation for the intervention. Incorporating community perspective in designing and implementing effective interventions to motivate time in nature is critical [32].

We then applied behavior economics concepts, including a pre-commitment contract, personalized nudges, and goal feedback, that have been previously shown to increase other health promotion practices such as physical activity [18]. At its core, increasing the amount of time people spend outside is a behavior change, and future interventions should consider building in evidenced-based behavioral nudges to assist people in achieving the desired outcome. Physicians telling patients to spend time outside, or even giving a prescription to do so, is unlikely to change behavior if it is not paired with other supports which influence patient ability, desire, and motivation to follow through. For example, recent evidence suggests that knowledge of park locations, perceived access to parks, and having time to go to parks are associated with increased park use among low-income families [33].

Finally, the barriers to spending time in nature identified through analysis of the Nature Coach field notes are similar to those in a previous prospective study of postpartum women on physical activity [34]. It is notable that for some participants, spending time in nature with a family member was a facilitating factor. This suggests that this type of intervention has potential positive spillover effects onto non-participants in raising awareness of the health benefits importance of nature through social networks [35].

There were several limitations to this study. First, we measured greenspace usage in Philadelphia, but not outside of city boundaries, due to the data layers available. We may, therefore, have undercounted nature visits. Second, the average daily high temperatures ranged from 69 °F at the start of the intervention period to 45 °F at the end of the intervention period. Differential weather may have influenced behavior. Third, the study had a small number of participants and was underpowered to detect an effect of the intervention on PPD; larger studies should be conducted that are powered to show differences in the desired health outcomes. In addition, our mean EPDS scores were relatively low at the start of the study, thus making it harder to detect improvements. A future study design could limit participants to those at the highest risk, for example, with a preexisting diagnosis of depression or a higher score on EPDS prior to discharge post-delivery. Fourth, there was a significant difference in participant income between the intervention and control group, with the control group reporting less income. This could have contributed to differential outcomes. Further studies with a larger sample size that can be properly balanced with randomization are needed. Finally, technical limitations of the AWARE app meant that if the app was inadvertently closed by a participant, we were unable to collect location data.

Conclusions

We successfully designed and implemented an intervention that increased the amount of time postpartum women spent in nature. Nature contact is an attractive potential PPD prevention intervention because of the negligible financial cost, the preference that many women have for non-drug treatment of PPD, and the positive impact nature may have on the woman, baby, and whole family. Further study is warranted to test the effect of the intervention in preventing or mitigating PPD in an at-risk population. Additionally, the Nurtured in Nature intervention may also benefit other populations—such as those at risk for or diagnosed with hypertension or diabetes, and people exposed to trauma that may be at risk for depression or post-traumatic stress disorder, and should be adapted to and tested in these groups.

Supplementary Information

Supplemental Figure 1. Sample educational material provided to participants (JPG 1767 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our Nature Coach, Lee Scottlorde, for her dedication to this project. This work was supported by Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Harold Amos Medical Faculty Development Program (grant number 76233, PI South). This work was supported by a pilot grant from the Penn ALACRITY Center (P50 MH113840; MPIs Beidas, Mandell, Buttenheim).

Footnotes

The original version of this article was revised: The word “Pregnant” in the article title has been corrected to read “Postpartum”.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

7/19/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s11524-021-00568-5

References

- 1.Hartig R, Mitchell R, de Vries S, Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annu Rev Public Health. 2014;35:207–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beyer K, Kaltenbach A, Szabo A, Bogar S, Nieto F, Malecki K. Exposure to neighborhood green space and mental gealth: evidence from the survey of the health of Wisconsin. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(3):3453–3472. doi: 10.3390/ijerph110303453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.James P, Banay RF, Hart JE, Laden F. A review of the health benefits of greenness. Curr Epidemiol Reports. 2015;2(2):131–142. doi: 10.1007/s40471-015-0043-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seymour V. The human–nature relationship and its impact on health: a critical review. Front Public Health. 2016;4 10.3389/fpubh.2016.00260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Shanahan DF, Bush R, Gaston KJ, Lin BB, Dean J, Barber E, Fuller RA. Health benefits from nature experiences depend on dose. Sci Rep. 2016;6(February):28551. doi: 10.1038/srep28551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, MacDonlad JM, Branas CC. Effect of greening vacant land on mental health: a citywide randomized controlled trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3) 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.ParkRx http://www.parkrx.org/. Accessed 6 Oct 2016

- 8.Kondo MC, Oyekanmi KO, Gibson A, South EC, Bocarro J, Hipp JA. Nature prescriptions for health: a review of evidence and research opportunities. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17 10.3390/ijerph17124213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Razani N, Morshed S, Kohn MA, Wells NM, Thompson D, Alqassari M, Agodi A, Rutherford GW. Effect of park prescriptions with and without group visits to parks on stress reduction in low-income parents: SHINE randomized trial. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0192921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Razani N, Niknam K, Wells NM, Thompson D, Hills NK, Kennedy G, Gilgoff R, Rutherford GW. Clinic and park partnerships for childhood resilience: a prospective study of park prescriptions. Health Place. 2019;57:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Müller-Riemenschneider F, Petrunoff N, Sia A, Ramiah A, Ng A, Han J, et al. Prescribing physical activity in parks to improve health and wellbeing: protocol of the park prescription randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15 10.3390/ijerph15061154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Annerstedt M, Währborg P. Nature-assisted therapy: systematic review of controlled and observational studies. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:371–388. doi: 10.1177/1403494810396400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384:1775–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stewart DE, Vigod S. Postpartum depression. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2177–2186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1607649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rafferty J, Mattson G, Earls MF, Yogman MW. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2019;143:e20183260. doi: 10.1542/peds.2018-3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression: an update. Nurs Res. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dennis CL, Dowswell T. Psychosocial and psychological interventions for preventing postpartum depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2:CD001134. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001134.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patel MS, Benjamin EJ, Volpp KG, Fox CS, Small DS, Massaro JM, Lee JJ, Hilbert V, Valentino M, Taylor DH, Manders ES, Mutalik K, Zhu J, Wang W, Murabito JM. Effect of a game-based intervention designed to enhance social incentives to increase physical activity among families. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1586–1593. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kangovi S, Mitra N, Grande D, Huo H, Smith RA, Long JA. Community health worker support for disadvantaged patients with multiple chronic diseases: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(10):1660–1667. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel MS, Small DS, Harrison JD, Fortunato MP, Oon AL, Rareshide CAL, Reh G, Szwartz G, Guszcza J, Steier D, Kalra P, Hilbert V. Effectiveness of behaviorally designed gamification interventions with social incentives for increasing physical activity among overweight and obese adults across the United States: the STEP UP Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.3505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison JD, Jones JM, Small DS, Rareshide CAL, Szwartz G, Steier D, Guszcza J, Kalra P, Torio B, Reh G, Hilbert V, Patel MS. Social incentives to encourage physical activity and understand predictors (STEP UP): design and rationale of a randomized trial among overweight and obese adults across the United States. Contemp Clin Trials. 2019;80:55–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2019.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Way To Health. https://www.waytohealth.org/. Accessed 29 May 2019

- 23.American Community Survey. 2014. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/. Accessed 1 Sept 2020

- 24.AWARE: Open-source Context Instrumentation Framework for Everyone. https://awareframework.com/. Accessed 29 May 2019

- 25.Kondo MC, Jacoby SF, South EC. Does spending time outdoors reduce stress? A review of real-time stress response to outdoor environments. Health Place. 2018;51:136–150. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2018.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.South EC, Kondo MC, Cheney R. a., Branas CC. Neighborhood blight, stress, and health: a walking trial of urban greening and ambulatory heart rate. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(5):909–913. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.South EC, Hohl BC, Kondo MC, MacDonald JM, Branas CC. Effect of greening vacant land on mental health of community-dwelling adults: a cluster randomized trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(3):e180298. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.ClinCard - Industry Leading Participant Payment Automation - Greenphire

- 29.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression: development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150:782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.South EC, Kondo MC, Razani N. Nature as a community health tool: the case for healthcare providers and systems. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:606–610. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zarr R, Cottrell L, Merrill C. Park prescription (DC Park Rx): a new strategy to combat chronic disease in children. J Phys Act Health. 2017;14:1–2. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2017-0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson E, Samayoa C, Mendez R, Wong M, Velazquez E, Márquez-Magaña L. Insider community-engaged research for Latinx healing in nature: reflections on and extensions from Phase 1 of the Promoting Activity and Stress Reduction in the Outdoors (PASITO) project. Park Steward Forum. 2021;37 10.5070/p537151709.

- 33.Razani N, Hills NK, Thompson D, Rutherford GW. The association of knowledge, attitudes and access with park use before and after a park-prescription intervention for low-income families in the U.S. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(3) 10.3390/ijerph17030701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Cramp AG, Bray SR. Understanding exercise self-efficacy and barriers to leisure-time physical activity among postnatal women. Matern Child Health J. 2011;15(5):642–651. doi: 10.1007/s10995-010-0617-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fadlon I, Nielsen TH. Family health behaviors. Am Econ Rev. 2019;109(9):3162–3191. doi: 10.1257/aer.20171993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Sample educational material provided to participants (JPG 1767 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 17 kb)

(DOCX 14 kb)