Abstract

Background & Aims

Patient-derived tumor organoids recapitulate the characteristics of colorectal cancer (CRC) and provide an ideal platform for preclinical evaluation of personalized treatment options. We aimed to model the acquisition of chemotolerance during first-line combination chemotherapy in metastatic CRC organoids.

Methods

We performed next-generation sequencing to study the evolution of KRAS wild-type CRC organoids during adaptation to irinotecan-based chemotherapy combined with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition. Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated 9 protein (Cas9)-editing showed the specific effect of KRASG12D acquisition in drug-tolerant organoids. Compound treatment strategies involving Aurora kinase A (AURKA) inhibition were assessed for their capability to induce apoptosis in a drug-persister background. Immunohistochemical detection of AURKA was performed on a patient-matched cohort of primary tumors and derived liver metastases.

Results

Adaptation to combination chemotherapy was accompanied by transcriptomic rather than gene mutational alterations in CRC organoids. Drug-tolerant cells evaded apoptosis and up-regulated MYC (c-myelocytomatosis oncogene product)/E2F1 (E2 family transcription factor 1) and/or interferon-α–related gene expression. Introduction of KRASG12D further increased the resilience of drug-persister CRC organoids against combination therapy. AURKA inhibition restored an apoptotic response in drug-tolerant KRAS–wild-type organoids. In dual epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)– pathway blockade-primed CRC organoids expressing KRASG12D, AURKA inhibition augmented apoptosis in cases that had acquired increased c-MYC protein levels during chemotolerance development. In patient-matched CRC cohorts, AURKA expression was increased in primary tumors and derived liver metastases.

Conclusions

Our study emphasizes the potential of patient-derived CRC organoids in modeling chemotherapy tolerance ex vivo. The applied therapeutic strategy of dual EGFR pathway blockade in combination with AURKA inhibition may prove effective for second-line treatment of chemotolerant CRC liver metastases with acquired KRAS mutation and increased AURKA/c-MYC expression.

Keywords: Cetuximab, FOLFIRI, Chemoresistance, KRAS, CRC Organoid

Abbreviations used in this paper: 3D, 3-dimensional; 5’-FU, 5-fluorouracil; ADF, advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12; AfaSel, afatinib + selumetinib; ANOVA, analysis of variance; AURKA, Aurora kinase A; Cas9, CRISPR-associated 9 protein; cDNA, complementary DNA; Cmab, cetuximab; c-MYC, c-MYC oncogene; CRC, colorectal cancer; CRISPR, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats; CT-PDTO, chemotherapy-adapted patient-derived tumor organoid; DMSO, dimethyl sulfoxide; EdU, 5-ethynyl-2’-deoxyuridine; EGF, epidermal growth factor; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; eKRAS, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats/Cas9-generated KRASG12D; ERK, extracellular signal-regulated kinase; E2F, E2 transcription factor; FFPE, formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded; FOLFIRI, folinic acid; 5’-FU, irinotecan (or SN-38); GSEA, gene set enrichment analysis; HER, human epithelial growth factor receptor; IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; LMU, Ludwig-Maximilians-University; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; MEK, mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase; MSI, microsatellite instable; PARP, poly-adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; PDTO, patient-derived tumor organoid; RAS, rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog; RNP, ribonucleoprotein; SN-38, irinotecan active metabolite; TCGA, The Cancer Genome Atlas; TOC, tumor organoid culture; UMI, unique molecular identifier

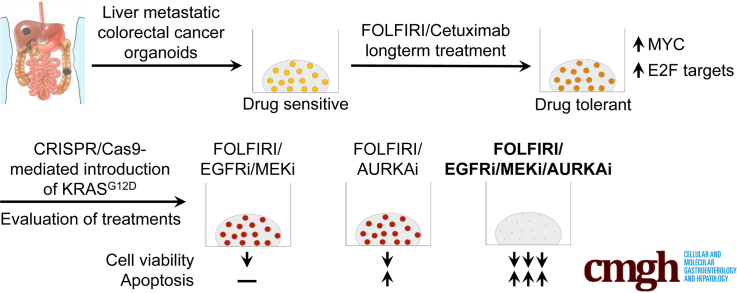

Graphical abstract

Summary.

We used organoids to decipher the evolution of colorectal cancer during chemotherapy. Genome editing-mediated KRAS (Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog) activation augmented chemotolerance in drug-adapted organoids. Aurora kinase A inhibition alone or in combination with dual epidermal growth factor receptor pathway inhibition induced apoptosis in KRAS–wild-type and KRAS-mutant organoids, respectively.

Metastatic spread and therapy resistance limit the success of today’s colorectal cancer (CRC) therapy, although multimodal treatment approaches have prolonged patient survival.1 Typical first-line combination treatments use cytostatic chemicals, such as FOLFIRI (folinic acid, 5’-fluoruracil, irinotecan). In the case of tumors with wild-type KRAS status, these cytostatic compounds can be combined with epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitory agents.2 However, oncogenic alterations in key mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling components, mostly mutations in KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF, render CRCs refractory to anti-EGFR–based therapy. Besides pre-existing genetic determinants of treatment outcome, chemotherapeutic pressure coincides with the emergence of so-called persister cells, a phenomenon frequently observed in the context of oncogene-targeting drugs.3 These subpopulations of drug-tolerant cancer cells often maintain residual disease after therapy-mediated eradication of the majority of the tumor mass and frequently possess altered epigenetic and transcriptional features rather than mutations in clinically relevant genes.4,5 Drug-persister cells form a long-lasting reservoir, which under continued therapeutic pressure eventually spawns tumor clones with newly acquired chemoresistance-conferring mutations. Modeling the oncogene activation-induced transition between drug-tolerant persister cells and their even more chemoresistant derivatives might provide new insight into CRC evolution during chemotherapy.

Recent years have witnessed the development of novel preclinical models that represent the genetic diversity and disease characteristics of CRC.6 The human organoid model, which allows the long-term culture of individual CRCs in a less labor- and resource-intensive way when compared with propagation of tumor cells in immune-deficient laboratory animals, has opened new avenues in personalized cancer medicine.7 Importantly, patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTOs) recapitulate the responsiveness toward different types of treatment in a variety of tumor entities. For CRC, Ooft et al8 showed that the effectiveness of 5’-fluoruracil (5’-FU) and irinotecan-based therapies correlate well with the ex vivo treatment sensitivity of matched PDTOs. Furthermore, clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9)-technology has been used to model isogenic pairs of rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (RAS)–wild-type and RAS-mutant PDTOs,9 which provides a powerful tool for developing therapeutic strategies against RAS-mutant tumors. For instance, studies on KRAS-mutant PDTO models showed that dual targeting of the EGFR–RAS–mitogen-activated protein/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK) axis is superior to monotherapeutic approaches.9 However, this approach by itself, similar to dual targeting of MEK and phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase (PI3K)- signaling, elicits a purely cytostatic rather than apoptotic response in PDTOs, thereby providing a mechanistic explanation for clinical failure.9, 10, 11, 12 Nevertheless, recent studies have recognized the potential of targeting compensatory signaling nodes orthogonal to MAPK signaling.9,13 The human tumor organoid model provides an ideal platform for the evaluation of novel combination treatment approaches and their associated predictive markers in a preclinical setting.

Here, we set out to model the evolution of liver metastatic CRC-PDTOs in the presence of a clinically relevant drug regimen ex vivo. Introduction of mutant KRAS in drug-tolerant persister PDTOs allowed us to study the specific effect of this oncogene in CRC organoids during prolonged exposure to targeted chemotherapy. Our study provides an important contribution to the integration of the PDTO model into preclinical oncology and highlights its potential for optimizing personalized cancer therapy.

Results

Ex Vivo Chemotolerance Modeling on KRAS Wild-Type CRC-PDTOs

We established a biobank of living PDTOs from primary and liver metastasized CRCs. PDTOs were embedded in a 3-dimensional (3D) matrix and maintained as previously described by Fujii et al.14 We selected 3 KRAS/NRAS and BRAF wild-type PDTO lines (PDTO1, 2, and 5) with similar characteristics: (1) tumor grade of 2 (moderately differentiated) according to a histology analysis (Figure 1A), (2) negative for microsatellite instability (MSI), and (3) a similar CRC key driver gene mutational pattern, including inactivating mutations in APC and TP53, based on next-generation panel sequencing (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1). These key features define the prototypic CRC entity with a high tendency for distant metastasis and susceptibility to anti-EGFR therapy.

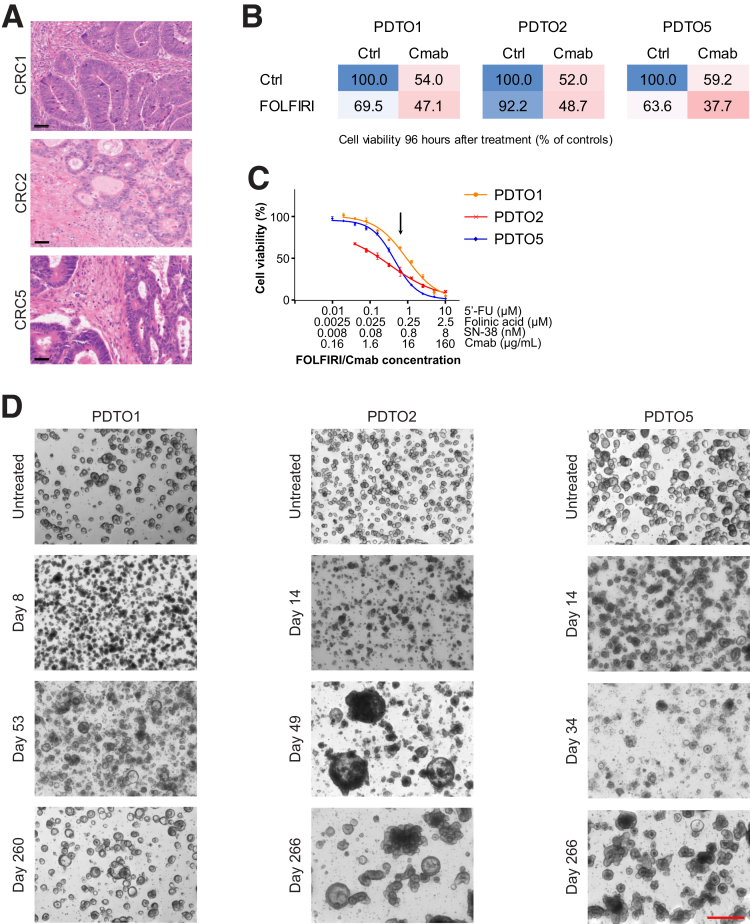

Figure 1.

Generation of first-line therapy–tolerant PDTO lines from liver metastatic CRC. (A) H&E staining of FFPE CRC tissue sections of patients 1, 2, and 5, from which the corresponding PDTO lines were established. CRC1, primary tumor of a liver metastatic CRC; CRC2 and CRC5, liver metastases of CRC. Scale bar: 50 μm. (B) Cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo 3D after 96 hours of drug treatment. Cells were either left untreated, treated with FOLFIRI or Cmab, or exposed to their combination (FOLFIRI/Cmab). Mean cell viability is given as a percentage of the untreated control, n = 3. (C) Dose-response curves showing the effect of a titrated FOLFIRI/Cmab combination drug regimen on PDTOs. Cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo 3D after 6 days of treatment and is shown as a percentage of the untreated control. Means ± SD, n = 3. A black arrow indicates the FOLFIRI/Cmab concentration chosen for long-term chemo-adaptation of PDTOs, thereby yielding CT–PDTOs. (D) Microscopic pictures of PDTOs during generation of FOLFIRI/Cmab tolerance after up to 9 months (days 260–266) of drug exposure. Images were taken on a Nikon AZ100 Zoom Microscope. Scale bar: 500 μm. Ctrl, control.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PDTOs Used for Chemotolerance Modeling in This Study

| PDTO line | Site of origin | KRAS/NRAS/ BRAF | PIK3CA | APC | TP53 | SMAD2/3/4 | MSI/MSS | Histology grade |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PDTO1 | Primary tumor (liver metastatic) | Wt | Wt | Mut | Mut | Wt | MSS | 2 |

| PDTO2 | Liver metastasis | Wt | Wt | Mut | Mut | Wt | MSS | 2 |

| PDTO5 | Liver metastasis | Wt | Wt | Mut | Mut | Wt | MSS | 2 |

Wt, wild-type; Mut, mutant; MSS, microsatellite stable.

We validated the sensitivity of KRAS wild-type PDTOs to FOLFIRI and the clinically approved anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab (Cmab), and determined the dose response of the FOLFIRI/Cmab combination treatment for each of the 3 PDTO lines (Figure 1B and C). For long-term chemotherapy exposure, we chose a uniform combination drug dose within the pseudolinear part of the dose-response curves to achieve a balance between PDTO elimination and survival of drug-persister cells (Figure 1C). Notably, the applied drug concentrations correspond to those reached in the plasma of CRC patients during chemotherapy,15, 16, 17 suggesting that our disease modeling approach approximated the selective pressure that CRC cells experience during this type of treatment in vivo.

After an initial phase of cell death and growth arrest, observed during the first 6–8 weeks of treatment, all 3 PDTO lines gradually evolved to recover better from sequential reseeding under chemotherapy (Figure 1D). However, acquisition of chemotolerance to a level that allowed us to expand PDTOs to quantities sufficient for further analyses only occurred after several months and with different kinetics for each PDTO line (PDTO1, 4 mo; PDTO2, 6 mo; and PDTO5, 5 mo).

CRC-PDTOs Can Acquire Drug Tolerance in the Absence of Hot Spot Mutations in KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA

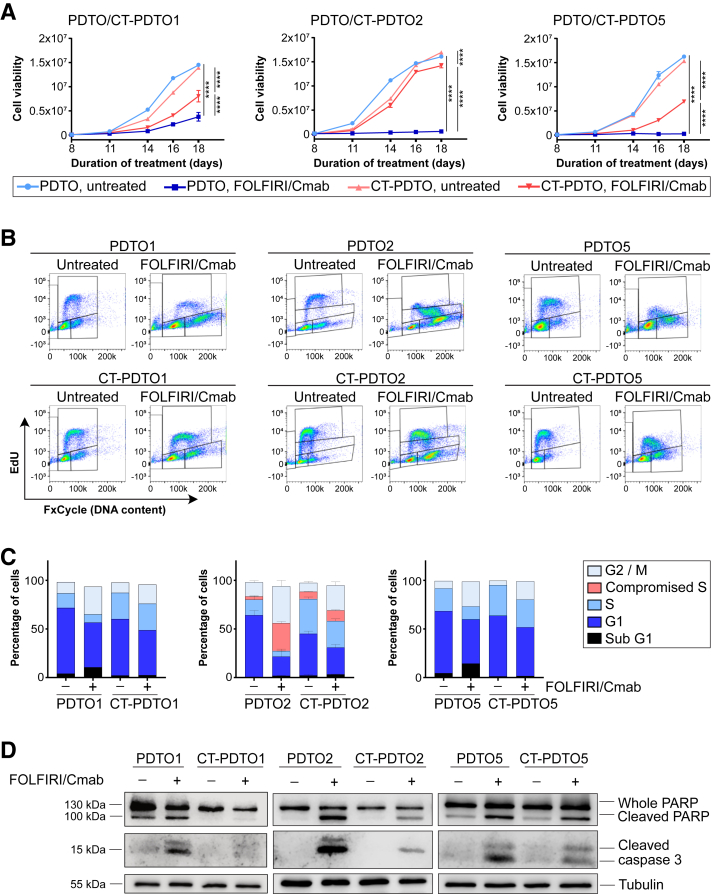

A 3D cell viability assay performed over a FOLFIRI/Cmab exposure period of 18 days confirmed the observed growth capacity gain in all 3 long-term, chemotherapy-adapted, PDTO lines (CT-PDTOs) when compared with their chemosensitive counterparts (Figure 2A). To determine the cell-cycle distribution of parental PDTOs vs their FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant derivatives, we labeled PDTOs and CT-PDTOs with the nucleoside analogue 5-ethynyl-2'-deoxyuridine (EdU) for subsequent flow cytometry analysis (Figure 2B). Combination drug treatment of PDTOs inhibited EdU incorporation, which led to a reduced fraction of cells residing in S-phase (PDTO1 and 5) or a compromised EdU incorporation of cells transiting S-phase (PDTO2) (Figure 2B and C). Indeed, these effects of FOLFIRI/Cmab on S-phase were not apparent or less pronounced in drug-adapted CT-PDTOs (Figure 2B and C). More importantly, analysis of poly-adenosine diphosphate ribose polymerase (PARP) and caspase 3 cleavage showed a reduced apoptotic response in all 3 FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant CRC organoid lines upon treatment (Figure 2D). Hence, evasion of apoptosis and restoration of DNA synthesis contributed to the augmented reseeding and growth capacity of CT-PDTOs. These results showed the successful generation of drug-tolerant derivatives of CRC organoids derived from 3 different individuals suffering from liver metastatic CRC.

Figure 2.

CT–PDTOs show reduced sensitivity toward FOLFIRI/Cmab. (A) Cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo 3D. Cells were either left untreated or treated for 18 days with FOLFIRI/Cmab. Statistical significance between all samples at each analyzed time point was assessed by 2-way ANOVA plus the Tukey multiple comparisons test and is for the latest time point indicated by asterisks (∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001). Means ± SD, n = 2 independent replicates for each of the 3 analyzed CT–PDTO/PDTO pairs. (B) EdU/FxCycle (DNA content)-based cell-cycle distribution. PDTO and CT–PDTO lines were treated with FOLFIRI/Cmab for 48 hours (PDTO/CT–PDTO2 and 5) or 72 hours (PDTO/CT–PDTO1) and subsequently pulsed with 10 μmol/L EdU for 2 hours. (C) Stacked bar chart showing the percentage of cell-cycle distribution as recorded in panel B. Note the discrimination between typical S-phase (light blue) and incomplete EdU incorporation in case of PDTO2/CT–PDTO2 organoids (red). Error bars in the middle panel represent SEM of n = 3 independent replicates. (D) For immunoblot analyses, established PDTOs were treated with FOLFIRI/Cmab for 48 hours. Induction of the pro-apoptotic markers cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 3 was analyzed as indicated, and detection of the housekeeper tubulin served as a loading control.

Next, we set out to assess the status of clinically relevant genes, such as KRAS, NRAS, BRAF, and PIK3CA, which are well known to confer resistance in their mutated form to the drug regimen applied here.18 To achieve this, we performed next-generation panel sequencing to examine the mutational status of more than 500 cancer-relevant genes. This approach identified de novo acquired point mutations in COL11A1 and DICER1 (CT-PDTO1 vs PDTO1) and a selection against PDTO subclones harboring mutations in TNFAIP3 (CT-PDTO2 vs PDTO2) and OR6F1 (CT-PDTO5 vs PDTO5) (Supplementary Table 1). Overall, we did not detect any point mutations that would explain the observed drug-tolerant phenotype in long-term, FOLFIRI/Cmab–exposed, CT-PDTO lines. Interestingly, a whole-exome sequencing-based comparison of CT-PDTOs with PDTOs showed differences in the abundance of several larger chromosomal segments (Table 2), although the pattern of alterations was heterogeneous between the 3 CT-PDTO/PDTO pairs. These data suggest that nonmutational events such as copy number alterations and nongenetic (ie, epigenetic) changes, which ultimately affect gene expression levels, may have contributed to the acquisition of chemotolerance in CRC organoids in this study.

Table 2.

Chromosomal Segment Copy Number Alterations Between Drug-Tolerant CT–PDTOs and Their Drug-Sensitive Parental PDTOs

| Position | NumExons | Size, bp | Amplification score |

|---|---|---|---|

| CT-PDTO1 vs PDTO1 | |||

| chr1:69085-12939931 | 1817 | 12,870,846 | 1.43a |

| chr3:361455-54922084 | 4830 | 54,560,629 | 0.68b |

| chr3:54925377-93754285 | 980 | 38,828,908 | 0.60b |

| chr11:193095-50004042 | 3797 | 49,805,878 | 1.55a |

| chr11:51411443-134257558 | 7159 | 82,846,115 | 0.70b |

| chrY:150850-5605988 | 134 | 5,408,963 | 2.28a |

| CT-PDTO2 vs PDTO2 | |||

| chr3:67048775-123689069 | 1880 | 56,640,294 | 0.68b |

| chr3:129291447-197896728 | 3682 | 68,605,281 | 0.71b |

| chr4:9828016-191013439 | 6594 | 181,185,423 | 0.68b |

| chr8:30854104-43048991 | 698 | 12,194,887 | 0.60b |

| chr8:43052086-75272550 | 1009 | 32,220,464 | 0.42b |

| chr8:75274114-116430685 | 1408 | 41,156,571 | 0.34b |

| chr8:116599223-146279548 | 1803 | 29,680,325 | 0.44b |

| chr18:158694-14764094 | 802 | 14,605,400 | 3.12a |

| chr18:14769337-25593878 | 463 | 10,824,541 | 2.54a |

| chr18:25727632-35145609 | 430 | 9,412,412 | 1.69a |

| chr18:39535252-78005236 | 1321 | 38,469,984 | 0.52b |

| chr20:36940271-62904958 | 2202 | 25,959,983 | 0.64b |

| CT-PDTO5 vs PDTO5 | |||

| chr1:69085-207318067 | 17,379 | 207,211,337 | 0.69b |

| chr1:207495106-236445088 | 1987 | 28,872,632 | 0.69b |

| chr1:236557740-249212567 | 685 | 12,654,827 | 0.69b |

| chr3:361455-127317320 | 7650 | 126,904,466 | 0.52b |

| chr3:127318156-197896728 | 3946 | 70,578,572 | 0.52b |

| chr13:28562595-53035114 | 1406 | 24,469,320 | 0.71b |

| chr22:24621509-45122519 | 2420 | 20,501,010 | 0.71b |

NOTE. Relative copy number alterations after FOLFIRI/Cmab adaptation were detected by whole-exome sequencing on genomic DNA derived from the indicated tumor organoid cultures. Chromosomal boundaries of altered segments are indicated (Position, reference genome hg19). The cut-off value for amplified and deleted regions is ± 1.4-fold, as shown in the Amplification Score column.

NumExons, total number of exons located on the chromosomal segment affected by relative copy number alteration; Size, number of nucleotides affected by the respective chromosomal segment alteration.

Amplified.

Deleted.

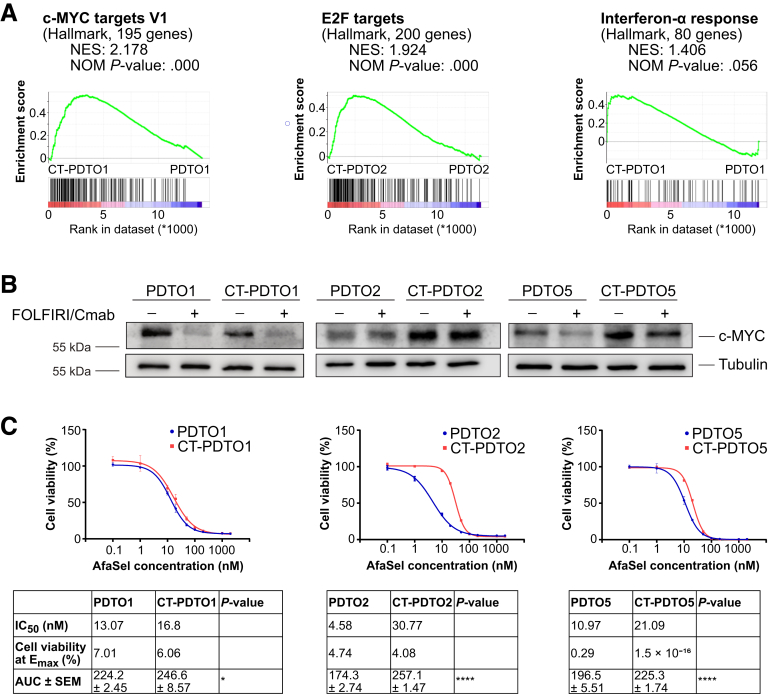

Adaptation of Global Gene Expression in Chemotolerant KRAS Wild-Type CRC PDTOs

Unbiased transcriptome analysis (RNA sequencing) on parental and CT-PDTOs was performed to uncover deregulated biological processes in drug-tolerant CRC cells. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the hallmark gene sets (MSigDB Collections; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA19,20) showed that 2 of 3 treatment-tolerant PDTO lines (CT-PDTO2 and CT-PDTO5) showed increased expression levels of E2 transcription factor 1 (E2F1) and c-myelocytomatosis oncogene product (c-MYC) target gene sets (Figure 3A, Table 3, and Supplementary Tables 2–5). Importantly, drug-exposed CT-PDTO2 and CT-PDTO5 also showed higher c-MYC protein levels, which were almost unaffected by FOLFIRI/Cmab treatment (Figure 3B). In contrast, the drug-tolerant derivative of PDTO1 showed enrichment of interferon-α signaling pathway–related genes (also seen in CT-PDTO2) (Figure 3A, Table 3, and Supplementary Tables 2–5). Notably, CT-PDTO1 lacked c-MYC gene set enrichment, expressed less c-MYC protein when compared with the parental PDTO1, and responded with a decrease of c-MYC levels upon FOLFIRI/Cmab exposure (Figure 3B), suggesting that it had evolved differently under therapeutic pressure when compared with the other studied PDTO lines.

Figure 3.

Enrichment of c-MYC protein and target gene set expression in CT–PDTOs coincides with decreased sensitivity to dual pan-HER and MEK inhibition. (A) GSEA of FOLFIRI/Cmab-treated CT–PDTOs vs untreated parental PDTOs using the Hallmark gene sets (MSigDB Collections; Broad Institute). (B) For immunoblot detection of c-MYC protein expression, PDTOs/CT–PDTOs were treated with FOLFIRI/Cmab for 48 hours or left untreated as indicated. Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) Cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo 3D. Cells were treated for 6 days with drug concentrations ranging from 0.1 to 2000 nmol/L for each of the EGFR/HER2 inhibitor afatinib and the MEK inhibitor selumetinib (AfaSel). Means ± SD, n = 3. IC50 values, cell viability at Emax (maximal effect, bottom plateau), and the area under the curve (AUC) are indicated in the tables below the graphs. Statistical significance between the area under the curves was assessed by an unpaired t test and is indicated by asterisks (∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001). NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM P value, nominal P value.

Table 3.

Results of Gene Set Enrichment Analysis on CT–PDTO Vs PDTO Gene Expression Signatures

| Tumor organoid line (chemotolerant vs ctrl) | Hallmark | NES | NOM P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDTO1 | HALLMARK_ANGIOGENESIS | 1.583 | .032 |

| HALLMARK_COAGULATION | 1.524 | .035 | |

| HALLMARK_COMPLEMENT | 1.357 | .055 | |

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 1.406 | .056 | |

| PDTO2 | HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 | 2.178 | .000 |

| HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS | 1.924 | .000 | |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V2 | 1.886 | .000 | |

| HALLMARK_INTERFERON_ALPHA_RESPONSE | 1.447 | .028 | |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | 1.238 | .059 | |

| PDTO5 | HALLMARK_E2F_TARGETS | 2.103 | .000 |

| HALLMARK_G2M_CHECKPOINT | 1.856 | .000 | |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V1 | 1.697 | .000 | |

| HALLMARK_MYC_TARGETS_V2 | 1.481 | .037 |

NOTE. The gene sets that are enriched after acquisition of chemotolerance are shown.

NES, normalized enrichment score; NOM P value, nominal P value.

Enrichment of c-MYC in CT-PDTOs Coincides With Reduced Sensitivity Toward Dual EGFR-Pathway Inhibition

A study by Misale et al21 showed that combined inhibition of MEK and EGFR/human epidermal growth factor receptor (HER) can partially circumvent anti-EGFR therapy resistance caused by acquisition of mutant KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF in CRC cell lines. To address the potential of dual vertical EGFR signaling blockade in our tumor organoid model of acquired FOLFIRI/Cmab tolerance, we treated CT-PDTOs with a combination of afatinib (pan-HER inhibitor) and selumetinib (MEK inhibitor) (from here on referred to as AfaSel). Indeed, this treatment substantially reduced cell viability in all 3 CT-PDTO lines (Figure 3C). However, we observed that CT-PDTO2 and CT-PDTO5, which had acquired increased expression of c-MYC protein and c-MYC–related target genes during long-term FOLFIRI/Cmab exposure, were less sensitive to AfaSel treatment when compared with their parental FOLFIRI/Cmab-sensitive lines (6- and 2-fold higher half-maximal inhibitory concentration [IC50] value, respectively) (Figure 3C). Notably, CT-PDTO1, which had taken a different route of transcriptional evolution characterized by increased interferon-α–related gene expression, showed an AfaSel sensitivity similar to the parental PDTO1 (Figure 3C). Our data suggest that long-term adaptation of CRC organoids to FOLFIRI/Cmab treatment can, as a potential side effect, also increase individual tumor cell resilience against alternative vertical EGFR pathway inhibition strategies. This association of secondary drug tolerance with augmented c-MYC levels and c-MYC gene set expression could prove useful for clinical decision making on second-line therapy options.

First-Line, Therapy-Tolerant, KRAS Wild-Type CRC-PDTOs Undergo Apoptosis Upon Aurora Kinase A Inhibition

Inhibition of signal transduction pathways that act orthogonally to EGFR signaling has been suggested to overcome chemoresistance in CRC,9 and major efforts in this direction are being made to indirectly engage undruggable targets, such as c-MYC22 or KRASG12D.23 Considering the enrichment of c-MYC protein and c-MYC target genes in CT-PDTO2 and CT-PDTO5, we asked whether inhibition of Aurora kinase A (AURKA), a G2/M checkpoint kinase also affecting c-MYC stability in hepatocellular carcinoma24 would overcome the acquired FOLFIRI/Cmab tolerance.

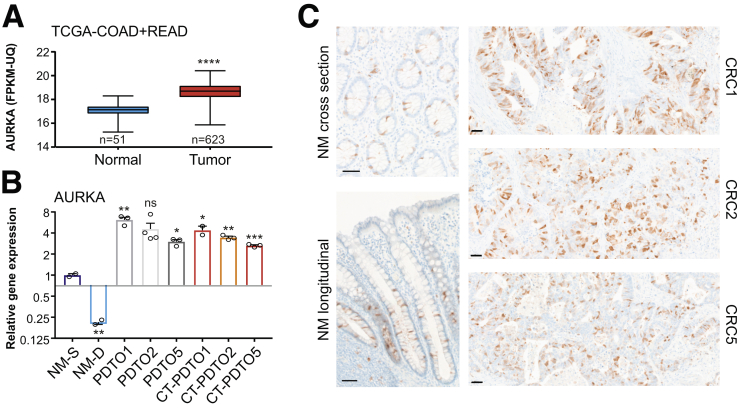

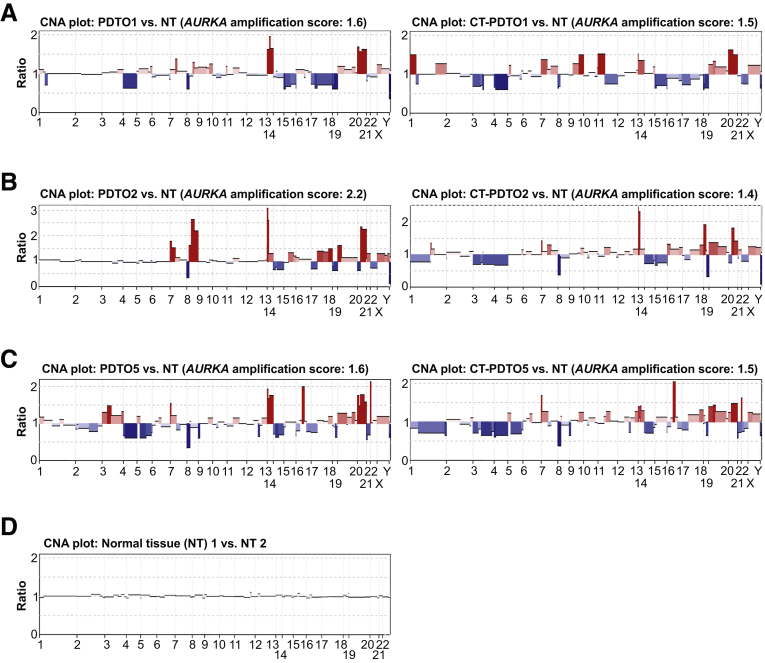

AURKA messenger RNA expression levels are increased in CRC according to RNA sequencing data obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (TCGA-CRC cohorts25) (Figure 4A) and amplification of the AURKA genomic locus represents a frequent feature of chromosomally instable CRC cells.26,27 In accordance with these data, the PDTO/CT-PDTO lines showed increased expression levels of AURKA when compared with normal mucosa-derived colonic organoids (patient-derived benign organoids) (Figure 4B). Immunohistochemical analysis on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue sections, prepared from the original CRC (CRC1, CRC2, and CRC5), confirmed increased expression of AURKA when compared with normal colonic mucosa (Figure 4C). In colonic crypts, AURKA expression was restricted to the transit-amplifying compartment (Figure 4C). Reduced AURKA expression levels were observed after ex vivo differentiation of patient-derived benign organoids (Figure 4B). CRC1 and CRC2 tissue sections showed a higher frequency of cells staining positive for AURKA (∼40%–50%) when compared with CRC5 (∼25%) (Figure 4C). In agreement, CT-PDTO5 showed 40% and 25% lower levels of AURKA when compared with CT-PDTO1 and CT-PDTO2 (Figure 4B). On the genomic level, the 3 chromosomally unstable PDTO lines and their FOLFIRI/Cmab-adapted CT-PDTO derivatives showed amplification of the AURKA encoding locus in the chromosomal region 20q13.2 (Figure 5).

Figure 4.

AURKA inhibition induces apoptosis in FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant PDTOs. (A) AURKA expression was analyzed on RNA sequencing data of the human TCGA–colorectal adenocarcinoma (COAD) plus TCGA–rectal adenocarcinoma (READ) cohort with a comparison of normal human mucosa (n = 51 cases) and tumor tissue (n = 623 cases). Box plots show the median and error bars indicate the minimal to maximal data spread. An unpaired, 2-tailed t test was performed to test for statistical significance, which is indicated by asterisks (∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001). (B) Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of AURKA expression in human organoids under stem cell (NM-S) or differentiation (NM-D) culture conditions (n = 2 independent replicates) in comparison with PDTO1, 2, and 5, and CT–PDTO1, 2 and 5 (n ≥ 2 independent replicates). Two-tailed t tests were performed to assess a significant difference of each sample to NM-S, which is indicated by asterisks (∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P ≤ .01, ∗∗∗P ≤ .001, ns, non-significant: P = .069. Error bars indicate SEM. (C) Immunohistochemistry staining for AURKA on normal human colonic mucosa and CRC tissues, from which PDTOs had been derived. Scale bars: 50 μm. FPKM-UQ, fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads-upper quartile normalized data.

Figure 5.

Copy number alterations (CNAs) of CT–PDTOs and PDTOs. The depicted CNA plots of PDTOs and CT–PDTOs in comparison with normal diploid tissue (NT) were derived from next-generation sequencing data (whole-exome sequencing). (A–C) PDTOs and CT–PDTOs were compared with diploid normal tissues. Note the pronounced genomic amplifications, indicated in red, of chromosome 20 regions containing the AURKA-encoding 20q13.2 locus. Amplification scores of the AURKA-encoding chromosomal region are indicated above the CNA plots. (D) Two NT samples showing no chromosomal alterations when compared with each other.

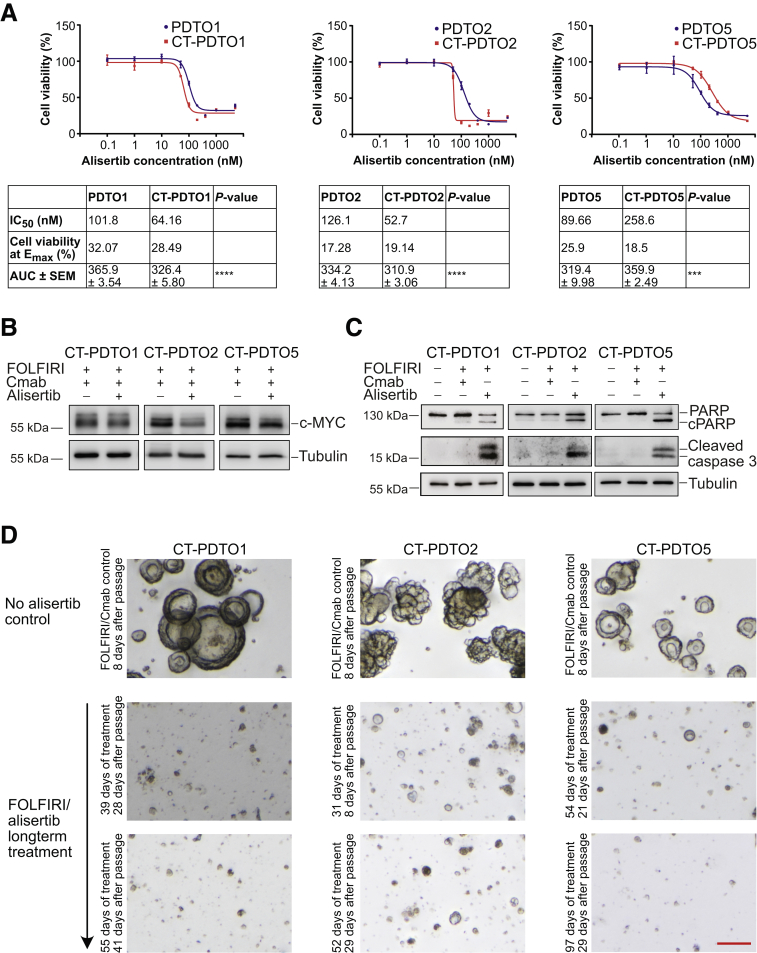

To therapeutically inhibit AURKA activity in CT-PDTOs, we made use of the clinically tested type II inhibitor alisertib (MLN8237).28,29 This class of AURKA inhibitors induces a conformational change in AURKA30,31 and thereby inhibits the interaction with MYC proteins, which results in subsequent MYC degradation.24

Although all 3 parental PDTO lines were similarly sensitive to AURKA inhibition (IC50 = approximately 90–120 nmol/L) (Figure 6A), the quantitative effect of alisertib on cell viability varied substantially between CT-PDTOs: CT-PDTO1 and CT-PDTO2 showed the highest (IC50 = 64.2 and 52.7 nmol/L, respectively) and CT-PDTO5 showed the lowest (IC50 = 258.6 nmol/L) sensitivity, therefore showing that FOLFIRI/Cmab long-term exposure ultimately increased alisertib sensitivity of PDTO1 and PDTO2, but decreased the responsiveness of PDTO5 to AURKA inhibition (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

AURKA inhibition reduces c-MYC levels and induces apoptosis in FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant PDTOs. (A) Cell viability was determined using CellTiter-Glo 3D. PDTOs and CT–PDTOs were either left untreated or treated for 6 days with 0.1–8000 nmol/L of the AURKA inhibitor alisertib. Means ± SD, n = 3. IC50 values, cell viability at Emax (maximal effect, bottom plateau), and the area under the curve (AUC) are indicated in the tables below the graphs. Statistical significance between the AUCs was assessed by an unpaired t test and is indicated by asterisks (∗∗∗P ≤ .001, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001). (B) Detection of c-MYC protein levels by immunoblot analysis in CT–PDTOs maintained in FOLFIRI/Cmab medium with and without addition of alisertib (400 nmol/L). Tubulin served as a loading control. (C) For immunoblot detection of pro-apoptotic markers cleaved PARP and caspase 3, established PDTOs were either left untreated, treated with FOLFIRI/Cmab, or FOLFIRI/alisertib for 48 hours. The alisertib concentration was 400 nmol/L. Tubulin served as a loading control. (D) CT–PDTO lines were maintained in culture medium containing FOLFIRI/alisertib (AURKA inhibitor, 400 nmol/L, middle rows and bottom rows) and serially passaged. The duration of treatment and the time since the last passage are indicated. As a comparison, FOLFIRI/Cmab-only treated CT–PDTOs at the same scale are shown in the first row. Note the different times since the last passage (8 days for controls, 29–41 days for the treated organoids at the end of the treatment period). Microscopic pictures were taken on a Nikon AZ100 Zoom Microscope. Scale bar: 100 μm.

In agreement with what was observed previously for hepatocellular carcinoma,24 the addition of alisertib led to a reduction of c-MYC protein levels in CT-PDTOs (Figure 6B). Notably, the effect of alisertib on c-MYC protein levels in CT-PDTO1, which had shown enrichment of interferon-α–related gene expression and a decrease of c-MYC after adaptation to FOLFIRI/Cmab (Figure 3A and B), was less pronounced when compared with the effects observed in c-MYC–enriched CT-PDTO2 and CT-PDTO5 (Figure 6B).

More importantly, treatment with FOLFIRI/alisertib restored or augmented an apoptotic response in all 3 CT-PDTO lines, as indicated by increased levels of cleaved caspase 3 and PARP (Figure 6C). Also, when maintaining CT-PDTOs in FOLFIRI/alisertib medium during serial passaging, we consistently failed to recover treatment-tolerant derivatives (Figure 6D), suggesting that in our in vitro organoid culture and combination treatment setting CRC cells were unable to adapt to inhibition of AURKA and ultimately underwent cell death. From these data, we conclude that inhibition of AURKA in metastatic CRC, especially in the context of 20q13.2 amplification associated with high AURKA levels, might have the potential to overcome a KRAS/NRAS/BRAF/PIK3CA mutation-independent, acquired tolerance to FOLFIRI/Cmab first-line therapy by restoration of a pro-apoptotic treatment effect.

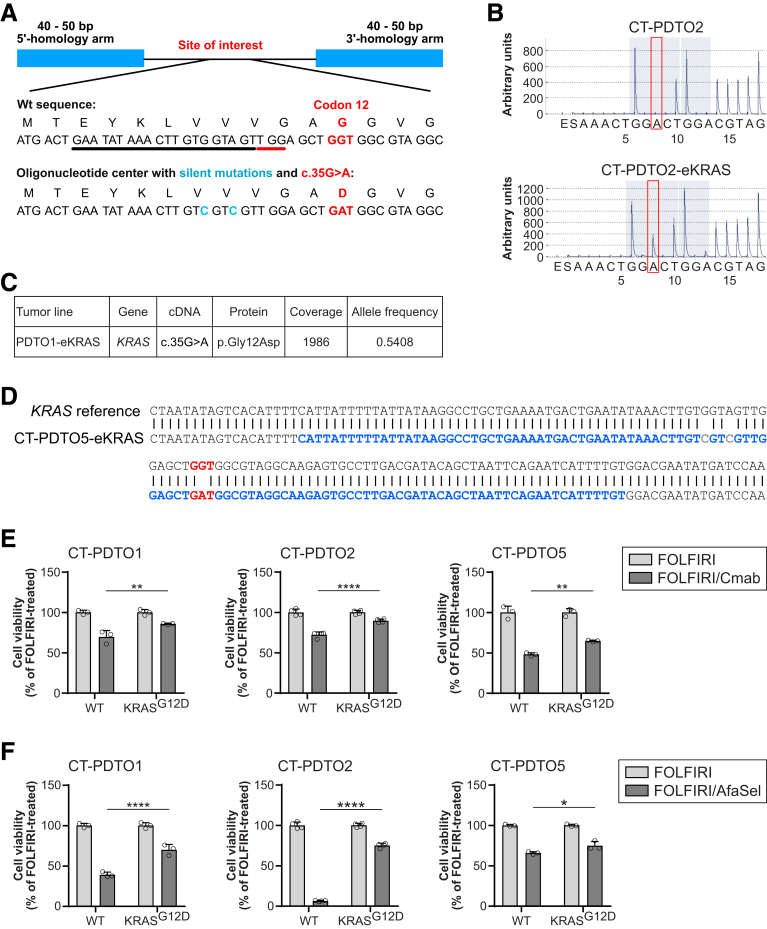

Modeling KRASG12D Acquisition in Drug-Tolerant PDTOs via CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genome Editing

Acquisition of oncogenic KRAS represents one of the main obstacles in CRC therapy,32 and KRAS-mutant CRC cells hardly respond to therapeutic strategies that engage the EGFR–RAS–extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) signaling axis.9 Because CT-PDTOs had not spontaneously developed alterations in KRAS during adaptation to FOLFIRI/Cmab treatment up to the time of analysis, we set out to genetically engineer the occurrence of endogenous KRASG12D in these long-term, drug-adapted CRC cells: KRASG12D mutant derivatives of CT-PDTOs (referred to here as CT–PDTO–CRISPR/Cas9-generated KRASG12D [eKRAS]) were generated by performing electroporation of tumor organoids with DNA-free Cas9-ribonucleoprotein (Cas9-RNP) complexes targeting KRAS in exon 2, plus a repair oligonucleotide harboring the G12D-encoding mutation (Figure 7A). In addition, the repair oligonucleotide contained 2 silent mutations to discriminate between spontaneously occurring vs genome editing–derived KRASG12D mutations. Three weeks after maintaining Cas9-RNP electroporated CT-PDTOs in FOLFIRI/Cmab-containing selection medium, the KRASG12D-encoding gene variant was confirmed by pyrosequencing (Figure 7B). Panel sequencing on CRISPR/Cas9-edited PDTOs with an approximately 2000-fold coverage showed an allele frequency of approximately 54% for the KRASG12D-encoding variant, which also showed the 2 silent mutations provided by the repair oligonucleotide (Figure 7C). To rule out collateral mutagenic alterations in the edited KRAS within or flanking the 5’- and 3’-homology arms of the repair oligonucleotide, we cloned 645 bp amplicons of KRAS exon 2 from CT–PDTO–eKRAS–derived genomic DNA and performed Sanger sequencing. This analysis confirmed the sequence integrity of the regions flanking the CRISPR/Cas9-edited locus in KRAS exon 2 (Figure 7D).

Figure 7.

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated engineering of KRASG12Din FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant CRC organoids. (A) Schematic representation of the repair oligonucleotide provided to PDTO cells together with CRISPR/Cas9-ribonucleoparticles targeting KRAS exon 2. Black underline indicates the 20-mer single guide RNA target sequence, the protospacer adjacent motif is shown with red underline. The oncogenic GGT>GAT (c.35G>A) mutation is shown in red. Silent mutations in the repair oligonucleotide are indicated in blue. (B) Analysis of mutations in the KRAS gene by using pyrosequencing technology. Red frames indicate the DNA nucleotide, which is mutated in oncogenic KRAS. Note the appearance of this A (GGT>GAT) only case of the CRISPR/Cas9-edited PDTO2 (PDTO2–eKRAS, lower panel). (C) Exemplary result of panel sequencing on PDTO1–eKRASG12D. The KRAS locus of interest was sequenced 1986 times (coverage), and 54.08% of sequences showed the G12D-encoding variant (allele frequency). (D) Sanger sequencing of the edited KRAS locus. Repair oligo sequence is indicated in blue. Oncogenic KRAS (GGT>GAT) mutation is highlighted in red, introduced silent mutations are indicated in grey. (E and F) Analysis of cell viability (CellTiter Glo 3D) on the indicated PDTO cultures treated with FOLFIRI alone or in combination with either (A) Cmab or (B) afatinib (dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor) plus selumetinib (MEK inhibitor) (AfaSel). Statistical significance of the differential treatment effects between PDTO lines harboring either wild-type or oncogenic KRAS was assessed by 2-way ANOVA plus the Sidak multiple comparisons test and is indicated by asterisks (∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P ≤ .01, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001). Means ± SD, n = 3. Wt, wild-type.

All 3 engineered CT–PDTO–eKRAS organoid lines showed increased resistance to Cmab treatment even when compared with their long-term FOLFIRI/Cmab-exposed, drug-tolerant CT-PDTO counterparts (Figure 7E). In accordance with Verissimo et al,9 KRASG12D acquisition also reduced the impact of vertical EGFR–MEK–ERK pathway targeting by pan-HER plus MEK inhibition (AfaSel) in all 3 CT–PDTO models (Figure 7F). These data show that acquisition of KRASG12D, even when occurring as a late mutational event in long-term reservoirs of drug-persister CRC-PDTOs, augments the resilience against different strategies of EGFR pathway inhibition.

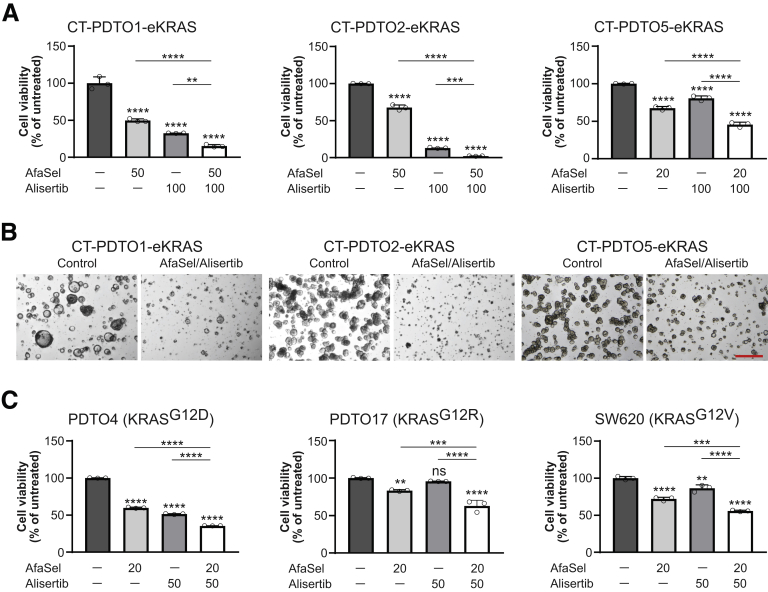

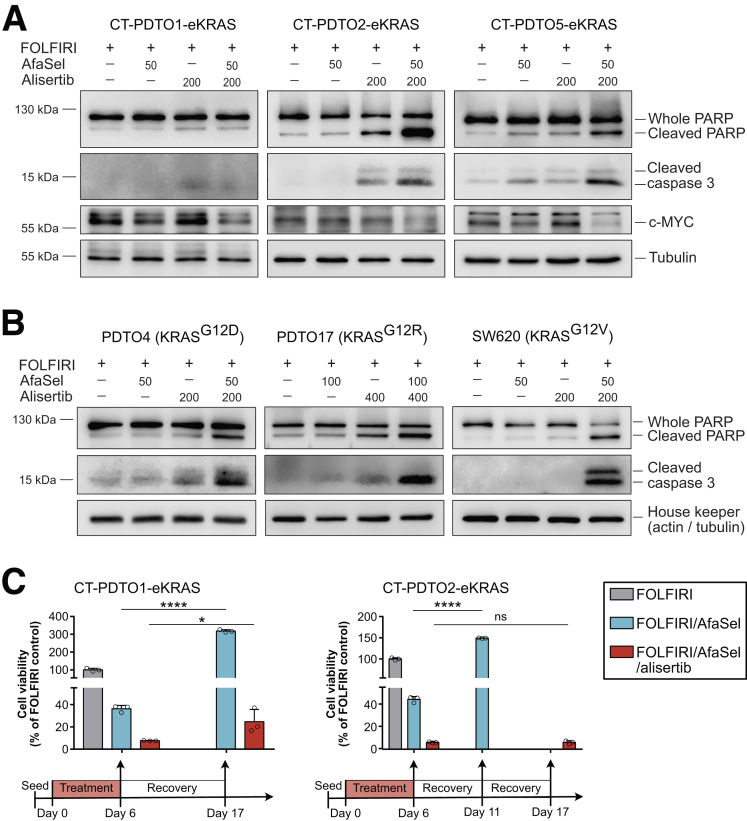

AURKA Inhibition Elicits Apoptosis in Dual EGFR–MEK Blockade-Primed, KRAS-Mutant CRC Organoids

Although dual inhibition of EGFR–MEK–ERK signaling by itself fails to elicit cell death in KRAS-mutant CRC organoids, it achieves an apoptotic priming, which can be exploited by combination treatment strategies.9 To address the potential of AURKA inhibition in this setting, we first treated 5 RAS-mutant PDTO models (3 CRISPR-engineered KRASG12D and 2 sporadic KRAS mutations) and 1 KRAS-mutant metastatic CRC cell line (SW620) with AfaSel or alisertib, or with a triple combination of these targeted drugs. Although both AfaSel and alisertib on their own reduced viability in KRAS-mutant PDTOs and SW620, a triple combination of these drugs was indeed more effective than each drug regimen alone (Figure 8). Importantly, FOLFIRI/AfaSel, in agreement with what was published previously,9 largely failed to induce more apoptosis in KRAS-mutant CRC cells than FOLFIRI alone, as indicated by low levels or a complete lack of PARP and caspase 3 cleavage (Figure 9A and B). Inhibition of AURKA alone (+FOLFIRI) showed a tumor organoid/CRC cell line-dependent effectiveness ranging from no detectable apoptosis (SW620) over a weak apoptotic response (CT–PDTO1–eKRAS, CT–PDTO5–eKRAS, PDTO17) to more substantial PARP and caspase 3 cleavage (CT–PDTO2–eKRAS, PDTO4) (Figure 9A and B). Strikingly, the triple combination AfaSel/alisertib (+FOLFIRI) was able to induce or augment an apoptotic response in all CRC–PDTO and cell-line models in which the treatment with AfaSel or alisertib (+FOLFIRI) had largely or completely failed, with the notable exception of KRAS-mutant CT–PDTO1 (Figure 9A and B). CT-PDTO1, in contrast to CT–PDTO2 and CT–PDTO5, had not acquired increased c-MYC protein levels and c-MYC gene set expression during adaptation to FOLFIRI–Cmab long-term exposure (Figure 3B and Table 3). Despite a relatively weak induction of apoptotic markers upon short-term (48 hours) treatment, CT–PDTO1–eKRAS, similar to CT–PDTO2/5–eKRAS, showed decreased c-MYC levels, especially upon triple combination treatment involving AURKA inhibition (Figure 9A). Next, we studied the longer-term benefit of triple combination therapy in comparison with a dual EGFR pathway blockade. To achieve this, complete drug removal after 6 days of treatment was performed as an example on CT-PDTO2-eKRAS and CT-PDTO1-eKRAS, which had shown an either strong or weak induction of apoptotic markers after AfaSel/alisertib (+FOLFIRI) short-term exposure (Figure 9A). As expected, AfaSel treatment (+FOLFIRI) in both cases failed to prevent a complete recovery and outgrowth of organoids during the recovery period (Figure 9C). More importantly, AfaSel/alisertib (+FOLFIRI) led to a persistent inhibitory effect on cell viability. In concordance with the extent of apoptotic marker induction (Figure 9C), CT–PDTO2–eKRAS was not able to re-establish organoid growth within 11 days after drug withdrawal, suggesting a very potent induction of cell death (Figure 9C, right panel), whereas CT–PDTO1–eKRAS cultures showed a partial recovery of organoid viability (Figure 9C, left panel). Taken together, these results suggest that therapeutic strategies against KRAS-mutant CRC based on dual pan-HER/MEK inhibition, which mainly primes these tumor cells for apoptosis, might benefit from concomitant inhibition of the G2/M checkpoint kinase AURKA. However, the treatment success of this strategy might be affected by the individual mechanism of CRC molecular adaptation to preceding therapies and the patient individual drug tolerability as a limiting factor for the applicable treatment intensity and duration.

Figure 8.

AURKA inhibition in RAS mutant PDTOs primed by dual EGFR–MEK–ERK pathway blockade reduces cell viability. (A) Cell viability analysis on CT–PDTOs carrying CRISPR/Cas9-engineered KRASG12D (eKRAS) after treatment for 6 days with the indicated drug regimen (AfaSel: afatinib [dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor] plus selumetinib [MEK inhibitor]; alisertib [AURKA inhibitor]). Drug doses are given in nanomolar concentrations. Statistical significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA plus the Tukey multiple comparisons test and is indicated by asterisks. Means ± SD, n = 3. (B) Extended focal imaging on embedded CT–PDTO–eKRAS lines that were either left untreated or treated with the combination of afatinib (dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor), selumetinib (MEK inhibitor), and alisertib (AURKA inhibitor) for 6 days. Images were taken on a Nikon AZ100 Zoom Microscope. Scale bar: 500 μm. (C) Cell viability analysis on SW620 and PDTO cells harboring the indicated oncogenic KRAS variants. SW620 and CRC organoids were treated for 3–7 days (SW620, 3 days; PDTO4, 5 days; and PDTO17, 7 days because their different growth speed and response to the targeted inhibitors) with the indicated drug regimen (AfaSel: afatinib [dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor] plus selumetinib [MEK inhibitor]; alisertib [AURKA inhibitor]). Drug doses are given in nanomolar concentrations. Statistical significance was assessed by 1-way ANOVA plus the Tukey multiple comparisons test and is indicated by asterisks. ∗∗P ≤ .01, ∗∗∗P ≤ .001, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001, ns, non-significant: P = .523. Means ± SD, n = 3.

Figure 9.

AURKA inhibition in RAS mutant PDTOs primed by dual EGFR–MEK–ERK pathway blockade elicits apoptosis. (A and B) Immunoblot analysis of the indicated apoptosis markers and c-MYC in (A) CT–PDTOs carrying CRISPR/Cas9-engineered KRASG12D (eKRAS) and in (B) PDTOs and SW620 cells harboring the indicated oncogenic KRAS variants 2 days after treatment with the indicated agents (FOLFIRI, afatinib [dual EGFR/HER2 inhibitor], selumetinib [MEK inhibitor], alisertib [AURKA inhibitor]). Applied drug doses are given in nanomolar concentrations. (C) Cell viability assessment of CT–PDTOs that have been recovered (drug withdrawal) for up to 11 days after treatment with either FOLFIRI/AfaSel (blue bars) or FOLFIRI/AfaSel/alisertib for 6 days (red bars). All values are normalized to the FOLFIRI-treated control group on day 6 when drug removal had been performed (grey bars). Note that in case of CT–PDTO2–eKRAS (right panel), FOLFIRI/AfaSel-treated PDTOs were completely regrown on day 11 and therefore this measurement was performed at an earlier time point compared with the FOLFIRI/AfaSel/alisertib-treated CT–PDTO2–eKRAS (day 17). Statistical significance was assessed by 2-way ANOVA plus the Sidak multiple comparisons test and is indicated by asterisks (∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001, ns, non-significant: P > .9999. Means ± SD, n = 3.

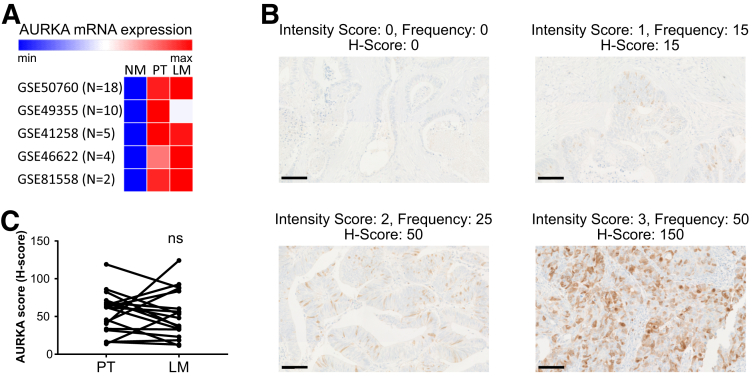

Increased Expression of AURKA in Primary Tumors Is Maintained in CRC Liver Metastases

Previous studies reported an association of increased AURKA levels with poor survival in CRC (TNM stages I–III) and in liver metastatic disease.33,34 To better address the abundance of the therapeutic target AURKA in CRC primary tumors and derived liver metastases, we first analyzed publicly available gene expression data from 5 CRC cohorts representing a total of 39 patient-matched triplets of normal tissue, primary tumor, and liver metastasis. Here, AURKA expression levels were increased similarly in cancerous tissue at the primary and liver metastatic side (Figure 10A). Next, we determined AURKA protein expression by immunohistochemical analysis of patient-matched primary CRC and liver metastases (n = 18). The staining pattern of AURKA in CRC cells was predominantly nuclear or nuclear-cytoplasmic and only a fraction of tumor cells showed AURKA expression in each tumor area (typically ranging from 5% to 40%) (Figure 10B). This is in accordance with what has been observed in previous studies.33,34 For that reason, we considered the H-score,35 which reflects both staining intensity and frequency, as a more robust measure for AURKA abundance than each of these staining parameters alone (Figure 10B). By using this approach, we could confirm that primary tumors and liver metastases of CRC patients show comparable AURKA messenger RNA and protein levels, although we observed a heterogeneity of AURKA levels between different individuals (Figure 10C). These data show that AURKA represents a highly abundant factor in CRC liver metastases, and it supports our hypothesis that targeting AURKA in combination therapy settings holds great promise for the treatment of affected patients.

Figure 10.

Expression of AURKA in patient-matched cases of primary tumors and their liver metastasized derivatives. (A) Heat map showing AURKA mRNA expression in 5 different CRC cohorts containing patient-matched tissue samples of normal mucosa (NM), primary tumor (PT), and liver metastasis (LM). Gene Expression Omnibus database accession numbers of the analyzed CRC cohorts are indicated. (B) Immunohistochemistry for detection of AURKA in FFPE CRC tissue sections. Staining within tumor areas was quantified with respect to intensity (0–3 grading scale: 0 = no staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, 3 = strong staining), and frequency (0%–100% of AURKA-positive cells in 5% increments). The H-score (possible range, 0–300) was obtained by multiplying staining intensity and the proportion of positive cells in a given area. Scale bars: 100 μm. (C) AURKA protein abundance (H-scores) as detected by immunohistologic staining on a CRC cohort (n = 18 pairs) of primary tumors and their patient-matched liver metastases. Statistical significance was assessed by a paired t test (ns, non-significant: P = .830). max, maximum; min, minimum.

Discussion

The tumor organoid model has been well accepted in recent years for ex vivo modeling of biological and clinical aspects of CRC.14,36 Applications using PDTOs involve biobanking, disease modeling via genome editing, and biomarker identification.36, 37, 38 A recent study by Ooft et al8 provided compelling evidence that CRC organoids derived from metastatic lesions can predict the responsiveness of CRC patients to 5’-FU plus irinotecan–based chemotherapy. In contrast, the PDTO model failed to recapitulate patient outcome to drug combinations involving oxaliplatin,8 suggesting that the particular ex vivo culture conditions of PDTOs limit the scope of their application to distinct types of chemotherapy. PDTOs were reported to acquire resistance to single chemotherapeutic compounds, such as 5’-FU and oxaliplatin.39 However, the ex vivo evolution of liver metastatic PDTOs in the presence of a complete clinically relevant drug regimen, which includes both cytotoxic and signaling pathways targeting molecules, needs further investigation. To achieve this, we studied disease progression of microsatellite-stable KRAS wild-type and liver metastatic PDTOs in the context of a combination chemotherapy (FOLFIRI/Cmab) commonly used in the clinic as first-line treatment of this CRC subtype.2 We show that acquired chemotolerance to FOLFIRI/Cmab, when accompanied by increased c-MYC protein levels and enrichment of c-MYC target gene expression, renders KRAS wild-type PDTOs also more resilient against a dual strategy of vertical EGFR pathway inhibition, which already has been moved into clinical trials.10 By following an orthogonal pathway targeting approach, we could further show that inhibition of the G2/M checkpoint protein AURKA reduced c-MYC protein levels and was able to overcome acquired treatment tolerance in CT–PDTOs by restoration of a pro-apoptotic treatment response. Future clinical studies should address whether FOLFIRI/Cmab treatment-tolerant metastatic CRC cases, which are wild-type for RAS/BRAF proteins and show AURKA amplification accompanied by increased AURKA/MYC expression, are especially dependent on AURKA functionality and therefore susceptible to AURKA targeting.

Moreover, we introduced the G12D-conferring genetic mutation into the endogenous KRAS locus via DNA-free CRISPR/Cas9-mediated genome editing of CT–PDTOs to selectively model a frequent and clinically challenging genetic event in CRC therapy.40 The engineered endogenous KRASG12D in FOLFIRI/Cmab-adapted CT–PDTOs further increased the resistance to single EGFR inhibition or dual EGFR–MEK blockade in all 3 analyzed CT–PDTO lines. Our results are in agreement with a previous study on classic CRC cell lines showing the de novo acquisition of oncogenic KRAS, NRAS, or BRAF in all cases at the stage of complete drug resistance to single-agent anti-EGFR treatment and after long-term drug exposure.21 However, although CRC cell lines used in the study by Misale et al 21 spontaneously acquired oncogenic alterations in KRAS upon longer-term treatment with Cmab alone, the PDTO models used here did not reach full Cmab resistance associated with genetic alteration in KRAS/BRAF/NRAS/PIK3CA genes after an approximately 10-month period of permanent FOLFIRI/Cmab exposure. We can only speculate that the clinically more relevant combination drug regimen used here eradicated CRC cells more effectively during the first months of treatment than Cmab exposure alone, and therefore strongly diminished the drug-persister cell pool susceptible for de novo genetic alterations in RAS or BRAF oncogenes. Nevertheless, our strategy to CRISPR/Cas9-engineer oncogenic KRASG12D in CT–PDTOs allowed us to selectively study the therapeutic phenotype of KRASG12D in first-line therapy-tolerant CRC cells. Our data show that even in a drug-persister CRC state, in which PDTOs have adapted to combination chemotherapy by largely evading apoptosis and by deregulation of cell growth–promoting transcriptional programs, the acquisition of KRASG12D still augments resilience against different therapeutic strategies that target the EGFR–RAS–ERK signaling pathway. This implies that the increase in c-MYC protein levels and c-MYC/E2F and/or interferon-α gene set expression observed here in CT–PDTOs only confer a partial drug tolerance to CRC cells and fail to fully substitute for oncogenic activation of KRAS in a scenario of therapeutic EGFR-pathway inhibition.

Targeting MAPK signaling in the context of oncogenic RAS variants has motivated decades of CRC research and the search for vulnerabilities of RAS mutant CRC represents an ongoing challenge. Inhibition of MEK signaling can sensitize RAS mutant CRC cells to EGFR/HER2 inhibition,41 and dual inhibition of PI3K/AKT and KRAS signaling showed promising results in vitro.42 However, moving these strategies into clinical trials yielded rather disappointing results, which was partially related to the toxicity of drug doses necessary for disease control.10,12 Another explanation for clinical failure of these approaches came from preclinical studies on patient-derived xenografts and organoids, which showed a purely cell cytostatic rather than pro-apoptotic effect in the majority of oncogenic RAS-harboring CRC models.9,11 Our drug recovery experiments performed on FOLFIRI/Cmab-tolerant organoids carrying mutant KRAS strongly support these findings by showing full growth recovery of CT–PDTOs–eKRAS lines after withdrawal of a combined FOLFIRI/AfaSel treatment. Intriguingly, it was shown that although dual inhibition of EGFR–MEK fails to elicit cell death in KRAS-mutant tumor organoids, it sensitizes cytostatic CRC cells for apoptosis induced by BCL2/BCLXL (B-cell lymphoma proteins 2 and XL) inhibition.9 Although this triple combinatorial approach suffered from drug toxicity, the study by Verissimo et al9 provides an important proof of concept that targeting EGFR–RAS–ERK signaling in combination with signaling nodes orthogonal to the MAPK pathway represents a promising strategy to tackle KRAS-mutant CRC. A rational for targeting signaling pathways orthogonal to EGFR signaling also was provided by Kapoor et al.13 In their study, deleting mutant KRAS in KRAS-driven pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma spawned escaper cells that mainly developed compensatory strategies independent of oncogenic KRAS signaling, such as activation of the Hippo pathway transcriptional complex YAP/TEAD2 (Yes-associated protein/TEA domain transcription factor 2).13 Interestingly, YAP/TEAD/E2F-driven bypass of mutant KRAS led to enhanced expression of the mitotic factors AURKA and AURKB.13 Whether inhibition of AURKA in this context eliminates KRAS-independent pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma escaper cells should be addressed further.

By following an orthogonal pathway targeting strategy, we showed that inhibition of the G2/M checkpoint kinase AURKA can reduce cell viability and elicit apoptosis in KRAS-mutant, FOLFIRI/Cmab-resistant CT–PDTOs when primed by a dual EGFR–MEK blockade. Interestingly, this triple combination was most effective in augmenting an apoptotic effect in those CT–PDTO lines, which had acquired increased c-MYC protein levels and c-MYC target gene set expression during adaptation to FOLFIRI/Cmab. Although the observed reduction of c-MYC protein in our experimental setting could be attributed to the destabilization of c-MYC protein upon allosteric AURKA inhibition, as described previously by Dauch et al24 in liver cancer, the exact mechanism of c-MYC down-modulation in the context of the multicomponent drug regimen applied here needs further investigation. Notably, the combination with alisertib allowed us to reduce apoptosis-inducing AfaSel doses by 10- to 20-fold when compared with the study by Verissimo et al,9 who reported toxicity of high-dose AfaSel in mice when applied in combination with the BCL-inhibitor navitoclax. Dual inhibition of EGFR–MEK by AfaSel treatment has been proven to be applicable in a phase I study on KRAS-mutant CRC, although drug doses had to be lowered when compared with the maximal single-agent dose to avoid drug toxicity.43 The AURKA inhibitor alisertib (+cytotoxic treatment) passed a phase I clinical trial without showing unexpected side effects, albeit at the lowest drug dose investigated.44 Our data suggest that relatively low doses of AfaSel and alisertib, when applied in a triple combination, can induce apoptosis in KRAS-mutant CRC–PDTOs. Nevertheless, in vivo studies on CRC mouse models and clinical studies are warranted to assess the tolerability and toxicity of the triple combination treatment presented here. A transfer to the clinic will be possible only if the desired pharmacodynamic effects of combined AfaSel/alisertib treatment can be achieved at tolerable drug doses and with clinically manageable side effects.

In agreement with our findings, experiments performed by Davis et al45 showed a benefit of combined inhibition of MEK and AURKA in 2-dimensionally cultured MSI CRC cell lines. We report a promising therapeutic effect of AURKA inhibition combined with dual blockade of EGFR signaling in first-line therapy–tolerant liver metastatic CRC organoids with oncogenic KRASG12D expression.

Genomic profiling of tumor glands and single-cell–derived organoid sequencing showed intratumoral heterogeneity in CRC and in PDTO models.46,47 According to the so-called Big Bang model of CRC, pre-existing rare tumor subpopulations, which possess genetic peculiarities that do not exist in the majority of the tumor mass, such as oncogenic KRAS, might evade diagnostic detection and ultimately become enriched under therapeutic pressure.47,48 The triple-combination blockade of EGFR–MEK and AURKA also might be effective against pre-existing sparse clones of KRAS-mutant cells in tumors of initially KRAS wild-type diagnosed CRC patients.

Chromosomal instability represents a critical genomic feature associated with the progression of CRC to distant metastatic disease (reviewed by Bach et al49). A progressive karyotype diversity has been suggested to confer tumor phenotype variability that is critical for metastasis formation.50 Mechanistically, chromosomal instability in CRC has been attributed to alterations in microtubule plus end attachments, which can be driven by oncogenic mutations in the tumor-suppressor gene APC or increased levels of AURKA.51,52 Indeed, AURKA has been shown previously to represent an independent indicator of chromosomal instability.53 By analyzing AURKA gene expression data from publicly available data sets and by performing immunohistochemical staining of AURKA in a patient-matched cohort of primary tumors and derived liver metastases, we could show that liver metastasized CRC cells overall maintain the increased expression levels of AURKA found in their primary tumors of origin. Taken together, our data on patient-derived tumor organoids and their drug-tolerant derivatives suggest AURKA as a promising therapeutical target in KRAS wild-type and KRAS-mutant CRC liver metastasis. Future studies should aim to address the potential of AURKA inhibition in reducing the liver metastatic burden of patients, who suffer from CRC characterized by AURKA amplification and increased c-MYC expression.

Materials and Methods

Patient-Derived Tissues for Organoid Cultivation and FFPE Tissues

Biological samples of fresh normal and cancerous tissue specimens were received from individuals undergoing curative colectomy or partial hepatectomy at the Hospital Großhadern, Ludwig-Maximilians-University (LMU) Munich. Samples were taken by a pathologist from residual resected tissue that was not needed for diagnostic purposes and irreversibly anonymized. This procedure has been classified as uncritical by the ethical committee of the LMU Munich and was specifically approved for our projects (projects 591-16-UE and 17-771-UE). Anonymized colorectal cancer specimens (FFPE tissues of the CRC cohort used for immunohistochemical staining of AURKA) from patients who underwent surgical resection at the University of Munich between 1994 and 2017 (LMU, Munich, Germany) were obtained from the archives of the Institute of Pathology. Follow-up data were recorded prospectively by the Munich Cancer Registry (data provided by J. Neumann, LMU, Munich, Germany). Specimens were anonymized, and the study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty of the LMU (approval number 18-105-UE).

Cell Line Culture

The cell line SW620 (ATCC, LGC Standards, Wesel, Germany) was maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (both Gibco, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Gibco). Cells regularly tested negative for mycoplasma contamination by using the LookOut Mycoplasma polymerase chain reaction (PCR) detection kit (Sigma/Merck).

Cytostatic Chemicals and Agents

Folinic acid (Chemical Abstracts Service (CAS) number 1492-18-8) was obtained from Merck, 5’-FU (CAS number 51-21-8) from Applichem (Darmstadt, Germany), irinotecan active metabolite (SN-38) (CAS number 86639-52-3) from TargetMol (Boston, MA), cetuximab (205923-56-4, Erbitux) from MerckSerono (Darmstadt, Germany), alisertib (MLN8237, CAS number 1028486-01-2) from Selleckchem (Houston, TX), and afatinib (BIBW2992, CAS number 439081-18-2) and selumetinib (AZD6244, CAS number 606143-52-6) from TargetMol. For the initial testing of the short-term response to chemotherapeutics (Figure 1B), the FOLFIRI concentration was 625 nmol/L folinic acid, 2.5 μmol/L 5’-FU, and 2 nmol/L SN-38. For generation of long-term chemotolerant PDTOs, cell viability assays, and immunoblot detections, drug concentrations were 156 nmol/L folinic acid, 625 nmol/L 5’-FU, 0.5 nmol/L SN-38, with the following exceptions: for cell-cycle analysis and immunoblot data showing comparisons between parental PDTOs and CT–PDTOs not involving AfaSel/alisertib (Figures 2B–D and 3B), the concentration was increased to 1250 nmol/L folinic acid, 5 μmol/L 5’-FU, and 4 nmol/L SN-38 (with the exception of PDTO2 in Figure 3B). The Cmab concentration was 10 μg/mL for all treatment experiments involving Cmab.

PDTO Culture

Isolation and propagation of primary human colonic epithelial and CRC cells from tissue specimens have been described previously.54 Matrigel (Corning Inc., Corning, NY)-embedded tumor cells were maintained in tumor organoid culture (TOC) medium (advanced Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium/F12 [ADF] supplemented with 10 mmol/L HEPES, Glutamax, 1 × B27; all Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1 mmol/L N-acetylcysteine (Sigma), 50 ng/mL recombinant human epidermal growth factor (EGF; PeproTech, Hamburg, Germany), 0.015 μmol/L prostaglandin E2 (Sigma), 25 ng/mL human noggin (PeproTech), 7.5 μmol/L p38 inhibitor (SB202190; Sigma), 0.5 μmol/L transforming growth factor β inhibitor (LY2157299; Selleckchem), and 50 μg/mL normocin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Besides this, 10 μmol/L Rho kinase inhibitor (Y27632; Selleckchem) was added to the medium for 48 hours after plating to avoid anoikis. Medium was replaced every 2–3 days. For serial passaging, embedded PDTOs were disaggregated using 0.025% Trypsin (Gibco, Thermo Fisher) for 10 minutes at 37°C, and subsequently passed through a 0.8-mm needle by a syringe. After washing with ADF medium, PDTO cells were counted and 5000–15,000 cells/50 μL Matrigel were reseeded in 3D, and overlaid with TOC medium.

CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Engineering of KRAS-Mutant CRC Organoid Lines

For CRISPR/Cas9-mediated engineering of KRASG12D, CT–PDTOs were electroporated with DNA-free ribonucleo-proteins (RNPs) consisting of the single guide RNA and the Cas9 enzyme. RNPs were assembled according to the manufacturer (IDT, Coralville, IA). CT–PDTOs were transfected by NEPA21-electroporation as described by the manufacturer. In brief, PDTOs were disaggregated using 0.025% Trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, ThermoFisher) for 7 minutes at 37°C and passed through a 0.8-mm needle by a syringe. PDTO cells (0.5–1∗105) were resuspended in 100 μL suspension of the RNP complex in OptiMEM (Gibco, ThermoFisher) supplemented with Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μmol/L). Final concentrations of the RNP complex components were as follows: 738 nmol/L CRISPR RNA (crRNA), 738 nmol/L trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), 369 nmol/L Alt-R™ Cas9 nuclease V3 (all IDT, Coralville, IA), 2.66 μmol/L electroporation enhancer (5’-TTAGCTCTGTTTACGTCCCAGCGGGCATGAGAGTAACAAGAGGGTGTGGTAATATTACGGTACCGAGCACTATCGATACAATATGTGTCATACGGACACG-3’), and 2.66 μmol/L of the KRASG12D homology directed repair (HDR) oligonucleotide (5’-CATTATTTTTATTATAAGGCCTGCTGAAAATGACTGAATATAAACTTGTCGTCGTTGGAGCTGATGGCGTAGGCAAGAGTGCCTTGACGATACAGCTAATTCAGAATCATTTTGT-3’). The suspension was transferred to a NEPA electroporation cuvette (EC-002S, 2-mm gap width) and electroporated using the NEPA21 electroporator (both Nepagene, Chiba, Japan) under the following conditions: 2 poring pulses of 150 V, 5 ms, with a pulse interval of 50 ms; followed by 5 transfer pulses of 20 V, for 50 ms, with an interval of 50 ms. After addition of 300 μL OptiMEM plus Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μmol/L) and incubation for 30 minutes at room temperature, the cells were embedded in Matrigel. Cells were cultured in TOC medium plus Rho kinase inhibitor Y-27632 (10 μmol/L) for 3 days before selection. Selection was performed by reducing the EGF concentration to 12.5 ng/mL and adding 10 μg/mL Cmab.

Generation of Chemotolerant PDTOs

Two days after seeding single cells, PDTO treatment with 156 nmol/L folinic acid, 625 nmol/L 5’-FU, 0.5 nmol/L SN-38, plus 10 μg/mL Cmab was started. The concentration of EGF was reduced to 12.5 ng/mL to augment Cmab effects. The TOC medium containing the chemotherapeutics was exchanged every 2–3 days. Serial passaging was performed as described earlier.

Complementary DNA Library Preparation, RNA Sequencing Analysis, and GSEA Analysis

Library preparation for bulk 3’-sequencing of poly(A)-RNA was performed as described previously.55 Briefly, barcoded complementary DNA (cDNA) of each sample was generated with a Maxima RT polymerase (Thermo Fisher) using oligo-dT primer containing barcodes, unique molecular identifiers (UMIs), and an adapter. The 5’ ends of the cDNAs were extended by a template switch oligo and after pooling of all samples full-length cDNA was amplified with primers binding to the template switch oligo site and the adapter. cDNA was tagmented with the Nextera XT kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA) and the 3’-end-fragments were finally amplified using primers with Illumina P5 and P7 overhangs. In comparison with Parekh et al,55 the P5 and P7 sites were exchanged to allow sequencing of the cDNA in read1 and barcodes and UMIs in read2 to achieve a better cluster recognition. The library was sequenced on a NextSeq 500 (Illumina) with 63 cycles for the cDNA in read1 and 16 cycles for the barcodes and UMIs in read2. Gencode gene annotations version 24 (version 28) and the human reference genome Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38 (GRCh38) were derived from the Gencode homepage (EMBL-EBI, Hinxton, Cambridgeshire, UK). Dropseq tools v1.1256 was used for mapping raw sequencing data to the reference genome. The resulting UMI filtered count matrix was imported into R programming language v3.4.4 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). To estimate the effect of treatment on parental and adapted tumors a dummy variable describing treatment and tumor type was used for downstream differential expression analysis with DESeq2 v1.18.1 (R package to analyse count data from high-throughput sequencing).57 Dispersion of the data was estimated with a parametric fit using the described dummy as parameter. The Wald test was used for determining differentially regulated genes between conditions. Shrunken log2 fold changes were calculated afterward. A gene was determined to be differentially regulated if the absolute approximate posterior estimation for general linear models (apeglm) shrunken log2 fold change was at least 1 and the adjusted P value was less than .01. Regularized logarithmic (Rlog) transformation of the data was performed for visualization and further downstream analysis. GSEA v4.0.3 was used to perform gene set enrichment analysis in the preranked mode using the apeglm shrunken log2 fold changes as ranking metric. A pathway was considered to be associated significantly with an experimental condition if the nominal P value was less than .05

Cell Viability Assessment

For PDTOs, 2500–4000 single cells were seeded in 20 μL Matrigel droplets in 48-well plates and overlaid with 500 μL TOC. Two to 3 days later, treatment was initiated by changing the TOC to drug-containing TOC. The TOC of untreated samples contained the concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) equivalent to the highest DMSO concentration of treated samples. The cells were treated for the indicated durations and medium was replaced every 2–4 days. For the growth curves of PDTOs and CT–PDTOs, the cells were treated for 8 days and then reseeded to prolong the treatment duration owing to the slow response kinetics of PDTOs toward the low, long-term FOLFIRI/Cmab dosage. The cell viability assay was performed with CellTiter-Glo 3D (Promega, Madison, WI). The TOC was removed and the Matrigel droplets were resuspended in 35 μL ADF plus 85 μL CellTiter-Glo 3D, incubated on a shaker for 5 minutes, then dissociated again with a pipette and incubated for another 20 minutes on a shaker. A total of 100 μL of the cell suspension was transferred to a white 96-well plate (Thermo Scientific) and luminescence was measured on a Berthold Orio II Microplate Luminometer (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). For SW620, 3000 cells were seeded in a flat-bottom 96-well plate in 80 μL culture medium. The next day, 20 μL of drug- or DMSO-containing medium was added and cells were cultured for 3 additional days. The cell viability was measured using CellTiter-Glo according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Luminescence was measured on a Berthold Orio II Microplate Luminometer. Cell viability was calculated as a percentage of DMSO-treated samples. Replicate numbers (n) are indicated in the figure legends. IC50 curves were generated with GraphPad Prism (v7.01) (Graph Pad Software, San Diego, CA) by using a 4-parametric logistic curve with a bottom constraint of greater than 0 to derive the IC50 values, bottom plateaus (maximal effect), and area under the curves. The area under the curve was calculated from the baseline Y = 0. The areas of 2 curves were compared using an unpaired 2-tailed t test.

Flow Cytometry–Assisted Cell-Cycle Analysis

Cell-cycle analysis was performed using the Click-iT EdU Alexa Fluor 488 Flow Cytometry Assay Kit in combination with the FxCycle Far Red Stain (both Invitrogen/ThermoFisher). After treating established PDTOs for 48 hours (PDTO2 and 5) or 72 hours (PDTO1, owing to slower response kinetics) with FOLFIRI/Cmab, EdU was added to the drug-containing TOC to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L for 2 hours. Embedded PDTOs were disaggregated using 0.025% Trypsin (Gibco, ThermoFisher) for 7 minutes at 37°C and subsequently passed through a 0.8-mm needle by a syringe. After washing with ADF medium, the cells were processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then resuspended in 400 μL 1× Click-iT saponin-based permeabilization and wash reagent. For DNA content staining, FxCycle Far Red Stain and RNase A were added to final concentrations of 200 nmol/L and 100 μg/mL, respectively. A total of 20,000 viable single cells were analyzed on a BD LRS Fortessa (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

RNA Isolation, cDNA Preparation, and Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Total RNA and cDNA was prepared using the High Pure RNA Isolation Kit (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA) according to the manufacturer’s protocols. Real-time PCR was performed using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) on a LightCycler480 (Roche). Relative expression values were normalized to PPIA and B2M expression and calculated using the ΔΔCt (delta delta Cycle threshold) method. Oligonucleotide pairs used for quantitative real-time PCR: PPIA (Peptidylprolyl Isomerase A) forward: 5’-AGCATGTGGTGTTTGGCAAA-3’, PPIA reverse: 5’- TCGAGTTGTCCACAGTCAGC-3’; B2M (Beta-2-Microglobulin) forward: 5’-TCCATCCGACATTGAAGTTG-3’, B2M reverse: 5’-ACACGGCAGGCATACTCAT-3’; AURKA forward: 5’-GTCTACCTAATTCTGGAATATGC-3’, AURKA reverse: 5’-AGTTCTCTGGCTTAATGTCT-3’. Melting curves were assessed in each experiment to confirm the generation of specific PCR products.

Panel-Guided Next-Generation Sequencing

Molecular analyses were performed at the Institute of Pathology of the LMU. DNA was extracted from organoids using the GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Merck). Targeted next-generation sequencing was performed with the Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus screening for genetic alterations in 500+ cancer-associated genes at the levels of DNA (single nucleotide variant, multiple nucleotide variant, indels, tumor mutation burden status, MSI status). Briefly, libraries were generated using the Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus and Ion AmpliSeq Library kit, IonXpress Barcode Adapter kit, and the Ion Library Equalizer kit, together with the Ion 550 Chip kits (all ThermoFisher), following each step of the respective user manuals. Libraries were sequenced on an Ion Torrent GeneStudio S5 Prime (ThermoFisher) next-generation sequencing machine. Analysis of the results was performed with the Ion Reporter System (v5.16; ThermoFisher), followed by further variant and quality interpretation with a homemade Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) tool and python-script (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, DE) filtering for clinically relevant mutations. Alterations were confirmed with the Integrated Genomics Viewer (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA). Mutations were judged as relevant on the basis of the interpretation criteria used in the public archive ClinVar (NCBI, Bethesda, MD).58 Only likely pathogenic and pathogenic mutations, as well as variants of unknown significance (or not evaluated in ClinVar with a prediction trend of being likely pathogenic) with allele frequencies of 3% or greater were reported.

Next-Generation Whole-Exome Sequencing

Genomic DNA from PDTOs was prepared using the GenElute Mammalian Genomic DNA Miniprep Kit (Merck). Whole-exome sequencing libraries were prepared using Agilent SureSelectXT Human All Exon V6 (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) and 200 ng of input DNA according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The final libraries were quality controlled by the Agilent 4200 TapeStation System (Agilent Technologies) and the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay kit (Life Technologies-Invitrogen). Based on Qubit quantification and sizing analysis, sequencing libraries were normalized, pooled, and clustered on the cBot (Illumina), with a final concentration of 250 pmol/L (spiked with 1% PhiX control v3). One hundred–bp paired-read sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 instrument using standard Illumina protocols at the Genomics and Proteomics Core Facility of the German Cancer Research Center (Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum, Heidelberg, Germany).

Raw sequence data were trimmed based on base-calling quality (minimum, 13) at both ends, while reads with lengths less than 50 nt after trimming were discarded, as well as reads containing N bases. Reads were mapped to the human reference genome 19 (hg19) using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA-aln) 0.7.10 with default parameters. Mapped reads were filtered based on mapping quality (minimum, 13), and reads not mapping to annotated protein coding regions were discarded. PCR duplicates were removed using samtools (licensed by MIT, Cambridge, MA) rmdup. Sequencing reads were realigned around insertions and deletions using GATK IndelRealigner (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA). Sequence variants were detected using samtools mpileup and VarScan 2.3.7 (Washington University, St.Louis, MO). Copy number alterations were detected as described previously,59 based on the optimalCaptureSegmentation R software package.60 The minimum size of copy number alterations was set to 5 Mb, with 2 exons minimum per segment, allowing up to 10 segments per chromosome.

Immunoblot Analysis and Antibodies

For PDTOs, the Matrigel was dissolved using Cell Recovery Solution (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) for 30 minutes on ice and washed twice in PBS. For SW620, lysates were prepared from subconfluent cultures by scraping in lysis buffer. Whole-protein cell lysates were prepared using RIPA buffer with protease inhibitor, NaVO3, and phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Dallas, TX), additionally supplemented phosphatase inhibitor cocktails 2 and 3 (Sigma). Lysates were incubated on ice for 30 minutes, then sonicated 3 times for 5 seconds with 75% amplitude (HTU Soni130; G. Heinemann, Schwäbisch Gmünd, Germany), spun 20 minutes at 12,000× g, and protein concentration was determined using the Micro BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Scientific). The lysates were separated on 10%–12% sodium dodecyl sulfate–acrylamide gels and proteins transferred to Immobilon polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Merck). The membranes were blocked with either 5% milk or bovine serum albumin in Tris-buffered saline, depending on the manufacturer’s instructions for the primary antibody. For immunodetection, membranes were incubated with the following antibodies: anti-actin (1:2000, A2066; Sigma/Merck), antitubulin (1:2000, T9026; Sigma/Merck), anti–c-MYC (1:1000, 10828-1-AP; Proteintech, Rosemont, IL), anti–cleaved caspase 3 (Asp175) (1:1000, 9661; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), and anti–cleaved PARP (Asp214) (1:1000, D64E10, 9542; Cell Signaling Technologies). Enhanced chemiluminescence signals from horseradish-peroxidase–coupled secondary antibodies (1:10,000; Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA) were generated using Immobilon Western horseradish-peroxidase substrate (Merck/Millipore) or SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (ThermoFisher), and detected using the LI-COR Odyssey Fc imaging system (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE).

Immunohistochemistry and Scoring of AURKA Staining

For immunohistochemistry, 2-μm whole-tissue sections of FFPE tumor samples were stained using a Ventana Benchmark (Ventana Medical Systems, Oro Valley, AZ) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell conditioning solution was used as a pretreatment and antibody binding was visualized using the Ventana UltraView DAB Immunohistochemistry Detection Kit (all Ventana Medical Systems). The antibody directed against AURKA (clone D3V7T; Cell Signaling Technology) was used at a dilution of 1:100. For quantification of AURKA expression, the previously published H-score was used.35 Each area of the section showing epithelial CRC tissue was assigned an intensity score from 0 to 3 (0 indicates no staining, 1 indicates a weak staining intensity, 2 indicates a moderate staining intensity, and 3 indicates a strong staining intensity), and the proportion of tumor cells staining for that intensity was evaluated in 5% increments (range, 0–100). The final H-score, ranging from 0 to 300, then was retrieved by adding the sum of scores obtained for each intensity and proportion of tumor areas stained. All FFPE samples were scored independently by 2 investigators (P.J. and S.L.B.). In case of discrepancy, samples were jointly re-analyzed to reach a consensus.

Statistical Analysis

GraphPad Prism software (v7.01) was used for statistical analyses. For calculation of significant differences between 2 groups of biological replicates, a Student t test (unpaired, 2-tailed, Holm–Sidak method, with an α level of .05) was applied. For comparison of 3 or more groups, a multiple comparison 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was applied. For unpaired data, 1-way ANOVA in combination with a Tukey multiple comparisons test was performed. For comparison of data with 2 different parameters, a 2-way ANOVA with either a Tukey (when all samples were compared with each other) or Sidak (when only certain treatments were compared with each other) multiple comparison test was performed. For calculation of correlation coefficients, Pearson correlation analysis was applied. Statistical significance is indicated by asterisks in the figures and further explained in the figure legends.

Imaging

Processed slides from immunohistochemical analysis were scanned using the quantitative slide scanner Vectra Polaris (Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Scanning was performed using the highest possible instrument setting (40-fold scan resolution). Snapshots of these scans were taken via Phenochart 1.0.8 software (Akoya Biosciences, Marlborough, MA). PDTO images were generated using an AZ100 multizoom microscope (Nikon, Minato City, Japan) and NIS Elements Imaging Software (version 5.00.00; Nikon).

Data Availability

Gene expression data of colorectal adenocarcinoma and rectal adenocarcinoma used for comparison of AURKA gene expression between cancerous and normal tissues were obtained from Genomic Data Commons (GDC)-TCGA data sets.61

Gene expression changes in CT–PDTOs compared with PDTOs are detailed in Supplementary Tables 2–4. Count-files and annotation of all technical and biological replicates are provided in Supplementary Table 5.

The next-generation sequencing raw data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (P.J.). These data are not publicly available because they contain information that could compromise research participant privacy or consent. Explicit consent to deposit raw sequencing data was not obtained from patients. Because all samples were irreversibly anonymized before the study start, the patients cannot be asked to provide their consent for deposit of their comprehensive genetic or transcriptomic data.