Abstract

Sexual precocity refers to the appearance of physical and hormonal signs of pubertal development at an earlier age. It may be considered as the expression of secondary sexual characteristics prior to the pubertal age in central precocious puberty (CPP), which is gonadotropin-dependent, early maturation of the entire hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal (HPG) axis occurs, with the full spectrum of physical and hormonal changes of puberty. True precocious puberty in girls must also be distinguished from premature thelarche (PT), usually with breast development before the age of 3 years, and premature pubarche (PA), with the isolated development of pubic hair. These conditions are not usually associated with accelerated growth rate or advancement in bone age. Clinical, laboratory and instrumental evaluations are necessary for the diagnosis. Pelvic ultrasound could serve as a complementary tool for the diagnosis, treatment and follow-up of CPP. The interpretation of clinical, laboratory and strumental data must be performed by an expert pediatric endocrinologist to maximize the diagnostic value in females with pubertal disorders. (www.actabiomedica.it)

Keywords: Pelvic ultrasound, precocious puberty, pubertal disorders, GnRH test, GnRH analogues, girls

Introduction

Female puberty is the physiological process by which a girl turns into a woman as a result of the progressive maturation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPG) axis. In western countries, females generally enter puberty between 9 and 13 years of age (1).

Precocious puberty (PP) in girls is traditionally defined as the appearance of secondary sexual characteristics before the age of 8 years (2).

In most cases, PP is gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) dependent secondary to idiopathic premature activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis, without any underlying anatomic factors, also known as central precocious puberty (CPP).

Occasionally, puberty can start early because of an abnormality in the master gland (pituitary) or the portion of the brain that controls the pituitary (hypothalamus) (3).

The frequency of CPP ranges between 1/5,000–1/10,000 (4). It is more common in girls compared to males, with a female/male ratio of 3/1 and 23/1 (4,5).

The GnRH-independent forms are secondary to adrenal, gonadal, ectopic excessive hormone production, or exogenous sex steroids intake (3).

These conditions may cause early epiphyseal maturation with compromised final height as well as psychological stress (2,6,7). Therefore, an early diagnosis and a proper management are essential (2,8).

In the diagnostic process of PP is important to differentiate this form by other conditions, such as: premature thelarche (PT) and premature adrenarche (PA) (9). However, these conditions do not accelerate bone maturation and do not require therapy with GnRH agonists (GnRHa) (3).

The clinical hallmark of PT is isolated breast development without other signs of puberty in the setting of normal growth and normal skeletal maturation (10). Classic clinical findings include breast Tanner stage 2-3 with immature nipples and unestrogenized vaginal mucosa (10). This condition is benign and usually requires only clinical observation (11). PA refers to isolated body hair (pubic and/or axillary) with or without mild acne and adult body odor. It is believed to arise from a normal maturational process within the zona reticularis of the adrenal glands resulting in the rise of adrenal androgen concentrations which are then converted to testosterone in the periphery (12).

The GnRH stimulation test is considered the gold standard to distinguish between the intermediate forms of precocious puberty that are not suitable for treatment with GnRHa, and CPP (1). Although the GnRH stimulation test exhibits high specificity, its sensitivity is relatively low (13% of cases of PT may progress to CPP in later times) and the diagnostic cut-off used for the diagnosis of CPP are non-consistent. In general a stimulated luteinizing hormone (LH) value ≥ 4–5 IU/L or an LH peak/ follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) peak ≥ 0.6, after GnRH test, using ultrasensitive automated chemiluminescence assays, is considered positive for an activation of HPG axis (13,14). When the cut-off value for the peak LH/FSH ratio was taken as > 0.24, the sensitivity was found to be 100% and specificity was found to be 84% (9). FSH estimation is in general not helpful causeof the considerable overlap of prepubertal values withpuberty (1,13,14). Therefore, when the results of the GnRH stimulation test are ambiguous, pelvic ultrasound (PU) can be used as an additional tool for the diagnosisof CPP.

PU has some well-known advantages, including being non invasive, inexpensive, readily available, radiation-free, and reproducible, and is a very useful diagnostic tool for evaluating the pediatric and adolescent female pelvis. It provides detailed information about the size of the uterus and ovaries, fundo-cervical ratio, endometrial thickness, and size and distribution of ovarian follicles (3).

Several investigators have documented increases in uterine and ovarian volume in childhood, with an increase in the number and size of the developing follicles during pubertal development (1, 15, 16). Therefore, various investigators have attempted to evaluate the role of PU in differentiating between girls with PT or PA and subjects with sexual precocity (9, 16,17).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of brain should be required, to investigate possible hypothalamic-pituitary lesions, particularly in presence of young age, rapid pubertal progression, and high estradiol concentrations.

The aim of the present review was to evaluate the role of PU in the differential diagnosis of pubertal precocities and in the management of CPP.

Pelvic ultrasound (PU) in pediatric age

PU is performed by the transabdominal approach using a conventional, full-bladder, 3.5-5 MHz convex transducer. The uterus and ovaries are visualized in both transverse and longitudinal sections. The most important parameters that must be assessed are:

- uterus: length, transverse diameter (width), endometrial thickness, fundal anteroposterior diameter, cervical anteroposterior diameter and volume. The ratio between the fundal and cervical diameters is calculated.

-ovaries: weight, width, length, number of follicles, maximal diameter of largest follicle and volume (18).

- theuterine and ovarian volume can be calculated by the formula for ellipsoid:volume = length x anteroposterior diameter x transversediameter x 0.5233.

The size and shape of the uterus and ovaries depend on age and hormonal stimulation.

Maternal and placental hormones determine relative enlargement of the uterus and ovaries in newborns. The neonatal uterus is prominent, usually showing a prevalence of the neck on the body, with well-visible endometrial rhyme and thickened myometrium; its size decreases after the first weeks/months of life (19).

An endometrial echo is found in 97% of infants aged less than 1 week, and in 50% of girls aged less than 6 months (20).

During childhood there are no changes in shape and size until the age of 7 years: the uterus is cylindrical, the size of the cervix is bigger than the body with a body/neck ratio = 1:2 (infantile uterus). It is not possible to see the endometrial rhyme(19).

From 7 years onwards, the uterine growth is slow and progressive and the body: neck ratio is 1:1 (transitional uterus); if viewable, the endometrial rhyme is thin (18,19).

At puberty, they undergo progressive increases in size which are clear correlated with the pubertal stages (2,21); the body grows more than the cervix causing the classic pear appearance with a body: neck ratio of 2:1 (post-pubertal uterus). Endometrial thickness greater than about 2 mm is visible (Figure 1).

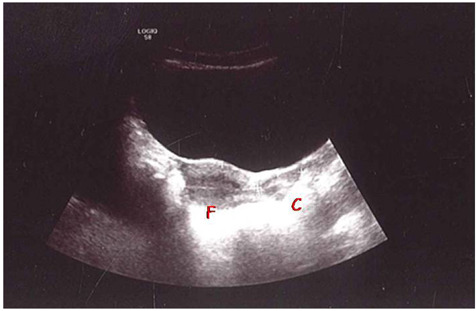

Figure 1.

PU in post-pubertal girl, 13 years old: body size of the uterus larger than the neck [4.6 cm vs 2.5 cm respectively, with a fundus (F)/cervix(C) ratio of 2:1], it is visible the endometrial thickness (Personal observation).

The presence of ovarian follicles (microcysts) at any age is physiologic, merely indicating an ovulation and FSH activation. The follicular diameter in prepubertal girls usually ranges from 2.0 to 9.0 mm. However, the occasional presence of large follicles (up to 12 mm) in this age group, owing to lower levels of gonadotropin secretion, limits the usefulness of follicular diameter measurement in the assessment of pubertal status (2,22).

Pelvic ultrasound (PU) in precocious puberty

PU is a diagnostic component for the evaluation for PP. The diagnosis of premature maturation of HPG axis is supported by ultrasound findings suggestive of mature ovarian and uterine structure. As would be expected, girls with CPP have larger uterine and ovarian volumes as compared to girls who are prepubertal and girls with PT (23).

Various study showed that findings such as increasing ovarian and uterine size, a thickened endometrial stripe, or presence of mature follicles within the ovaries reflect activation of the pubertal axis, supporting the diagnosis (24).

This is an important diagnostic data that supports the clinician in his decision to perform or not further laboratory (GnRH test) or diagnostic investigations.

However, diagnostic thresholds for uterine and ovarian volumes are variable and it is possible to have, in early stages of pubertal development, an overlap between patients with CPP and other benign variants (9,23,25,26).

In the CPP group, pelvic US measurements had a stronger positive correlation with bone age than with chronological age, indicating these parameters were affected directly by what triggers the early maturation of bone, e.g., early gonadotropin secretion (3).

Badouraki et al. (9) reported uterine length was the best parameter for distinguishing between CPP and PT cases, a cutoff of 3.19 cm and of 3.83 cm gave sensitivities of 85.7 and 82.4% and specificities of 91.7 and 90.9% for the 0 to 6 and >6 to 8 years age intervals, respectively.

Wen et al. (27) showed that uterine length is the third most efficient parameter for diagnosis for CPP for the >8 to 10 years age interval, a cutoff of 2.45 cm gave a sensitivity of 84.21 and specificity of 88 %.

The fundus/cervix ratio was reported as an important parameter of the pubertal uterus (28-30). In puberty, hormonal influences on the uterus made the fundus prominent with a fundus/cervix ratio greater than 1. Previous studies reported a bigger fundus/cervix ratio in the CPP group (9,28,31). (Figure 2).

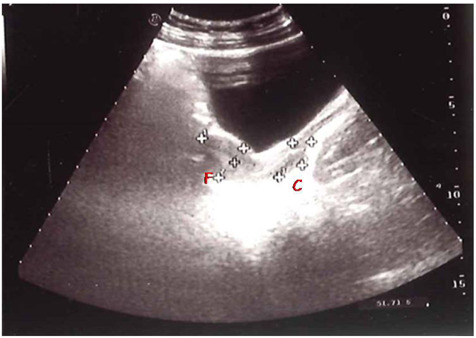

Figure 2.

Size of the uterus in children with CPP, 6,8 years old; uterine length about 5,9 cm, with fundus (F)/cervix (C) ratio greater than 1 (fundus 4,5 cm/cervix 1,4 cm). (personal observation)

However, in other reports there were no significant differences in the fundus/cervix ratio between the CPP and PT group (16,28). In the study of Yu et al. (28), the fundus/cervix ratio was 1.49±0.46 in the CPP group and 1.50±0.59 in the PT group, without significant differences.

The uterine endometrial echogenicity may be of help in the diagnosis of CPP, although it was highly specific, but less sensitive (2,31) (Figure 3).

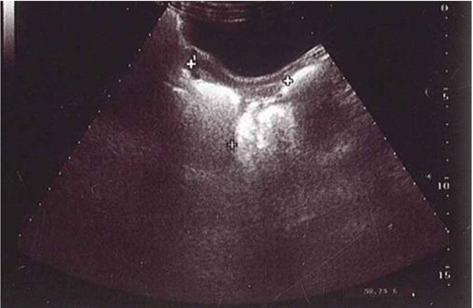

Figure 3.

Endometrial thickness of about 3 mm in a children with CPP, 6 years old (Personal observation).

Wen et al. (27) found that endometrial thickness is an important parameter to distinguish CPP from normal girls in the 8-10 year range. The cut-off of approximately 0.26 cm had a sensitivity of 76.92% and a specificity of 100%.

In Yu’s study (28), endometrial echogenicity was observed in only one case with advanced CPP, suggesting that the assessment of this parameter is less useful in the early stage of puberty. Therefore, it is necessary to combine multiple ultrasound parameters with clinical manifestations and sexual hormone levels for the diagnosis of CPP (32).

Various studies have shown that ovarian enlargement is an important test for the diagnosis of PP. Yu et al. (32) showed that ovarian volume was increased in CPP patients compared with the control group. Ovarian maturation has been promoted by increased FSH secretion, therefore bilateral ovarian volume increase is an important and early indicator of PO, and is very useful for its diagnosis. In previous studies, mean ovarian volume and ovarian area were greater in the CPP group (9, 24,31,33,34) (Figure 4).

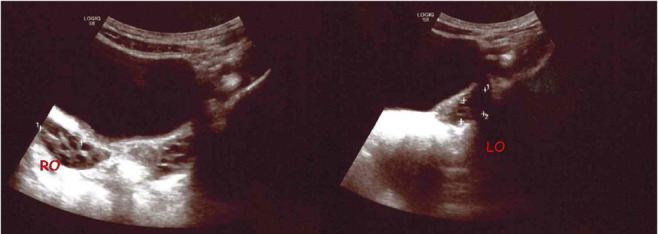

Figure 4.

Increased ovarian volume in a 6-year-old girl with CPP: right ovary (RO) 2,2 ml, left ovary (LO) 3,04 ml with multicystic aspect (Personal observation).

Regarding the cutoff value for the clinical application of PU, Haber et al. (29) suggested a cutoff value with high sensitivity and specificity, with a uterine volume cutoff value of 1.8 mL, ovarian volume of 1.2 mL, and uterine length of 3.6 cm2. De Vries et al. (31) suggested ovarian volume cutoff value of 2.0 mL, with 88.8% sensitivity and 89.4% specificity, and a uterine length cutoff value of 3.4 cm, with 80.2% sensitivity and 57.8% specificity. Binay et al. (35) suggested a uterine length cutoff value of 3.0 cm (93.1% sensitivity, 86.6% specificity) and an ovarian volume cutoff value of 1.3 mL (72.7% sensitivity, 90.0% specificity). Lee et al. (36) showed that uterine length showed 33.33% sensitivity and 79.79% specificity in the case of a cutoff value of 4.09 cm. Uterine volume showed 64.18% sensitivity and 71.79% specificity in the case of a 3.3-mL cutoff value, and ovarian volume showed 85.00% sensitivity and 26.09% specificity in the case of a 3.5-mL cutoff value.

Reasons for the differences of cutoff values may be ethnic differences, size differences, interpersonal variations of radiologists and performance differences among ultrasound graphic machines.

To overcome this variability, in some recent studies, some authors have proposed the study of the uterine artery via spectral Doppler US as a useful and objective method to identify the stages of organ development (37-39). The pulsatility index (PI), which is calculated as (systolic peak − diastolic peak) / time-average flow velocity, is an expression of vascular compliance in the uterine artery. This idea comes from the evidence of the important action of circulating estrogen in reducing vascular resistance and, consequently, the PI values. This mechanism, together with the indirect action of circulating LH, which stimulates the production of neoangiogenic growth factors, results in an overall increase in uterine blood flow that could be responsible for the increase in size of internal genitalia that is observed during puberty (37). However, larger and long-term studies are needed to evaluate the diagnostic efficacy of this new parameter.

In summary, the data of literature show that girls with PP demonstrate significantly higher ultrasonographic measurements of the uterus and ovaries compared to normal girls and to girls with PT and PA. PU could be a supplement of the GnRH stimulation test and more acceptable by PP girls and their parents, for its non-invasiveness and speed of execution. However, it would be of particular importance to evaluate precise cut-off values, as well as to investigate intra- and interobserver variability of ultrasound technique, and change in different populations.

PU compared with GnRH test

As already stated the GnRH stimulation test is regarded as the gold standard for a diagnosis of CPP.

In the last few decades many authors compared the PU findings of ovaries and uterus with GnRH stimulation tests in assessing the pubertal status of young girls who were evaluated for PP (1,15-17,31,39).

The data of literature showed that a normal endometrial echogenicity and normal uterine volume, reflecting an infantile morphology, were useful sonographic parameters to exclude the activation of the HPG axis.

Three studies compared the diagnostic values of ultrasound versus the GnRH test (1,17,31). Although the concordance between these two parameters was good, the PU parameters resulted more sensitive.

De Vries et al. (31) showed that an uterine transverse diameter greater than 1.5 cm and an uterine volume greater than 2.0 ml were better predictors of PP than the peak of LH after GnRH stimulation test.

Battaglia et al. (1) showed that sonography proved to be a test of high value in the diagnosis of female precocious puberty. Increased uterine volume (> 4 mL) and the presence of a midline endometrial echo demonstrated adequate specificity (87% and 86%, respectively), good sensitivity (87.5% for both parameters) and high concordance with the GnRH-stimulation test (93% and 91%, respectively). These data are in accordance with those of Haber et al. (17) and show that no significant overlap exists between true PP and other premature pubertal anomalies.

Nevertheless, an absolute comparison between GnRH test results and PU is difficult due to the different roles of these diagnostic tests.

Garibadi et al. (40) used the GnRHa stimulation test (20 µg/kg, Leuprolide acetate s.c., followed by 24-h serial sampling) to investigate the relationship between gonadotropin and estradiol (E2) secretion in the early phase of female CPP. Their data suggest that girls with CPP in the early phase of activation of the HPG axis are capable of clinically relevant E2 production, which may occur in the face of low LH secretion and low LH/FSH ratios and cannot be explained solely on the basis of increased FSH secretion.

In contrast, PU alone did not distinguish between prepubertal females and those in the early stages of puberty (24).

PU in the management of response to therapy

The objectives of CPP therapies are to inhibit premature sexual development, to improve impaired adult height due to the advance of bone age (BA), and to prevent psychosocial problems associated with prematurity and early menarche. GnRHa, which are a high-active derivatives of GnRH, have been used in the treatment of CPP for more than 20 years and are the mainstayin achieving all the treatment goalswhen used in the appropriate clinical setting. These drugs suppress gonadotropin secretion through a desensitization and down-regulation of GnRH receptors, leading to reduction of gonadal steroids to prepubertal levels. Good predictors ofheight outcomes, include younger chronological age (CA), younger BA, greater height standard deviation score for CA at initiation of therapy and a higher predicted adult height using Bayley–Pinneau tables (41). GnRHa should generally be continued till 11 years age, when pubertal progression is more likely to commensurate with peers (42).

At the present, monthly depot preparations are usually employed, at least in Europe. Quarterly and yearly depot formulations of GnRHa are now available, having potential advantages in improving compliance and the quality of life of children under treatment (43,44,45).

Monitoring during GnRHa treatment is important to prevent an inadequate outcome possibly resulting from various factors, including poor adherence or ineffective administration, but as yet although there are no definitive standard criteria for assessing the adequacy of the suppression obtained (40), a random LH level < 0.6 IU/L or a GnRHa-stimulated peak LH level < 4 IU/L, using modern ultrasensitive automated chemiluminescence assays as long as physical exam, growth rate, and rate of bone age progression, are consistent with suppression (46).

Various investigators suggested that the uterine and ovarian structural parameters decreased after GnRHa treatment (32, 47-52).

PU was systematically performed on 33 girls with idiopathic CPP to investigate the impact of treatment with GnRHa on female internal genitalia. All girls were treated with a long-acting GnRHa (Depot Triptorelin, 75 µg/kg every 4 weeks, IM preparation). Before, during, and after treatment, PU was performed and ovarian and uterine volumes were calculated. Within 3 months of treatment, both ovarian and uterine volumes decreased significantly (p: < 0.01) to normal values appropriate for age. Median ovarian volume, after 3 months of treatment, was 0.0 SD (range -2.4 to 1.5 SD); median uterine volume was 0.7 SD (range -0.6 to 4.1 SD). Ovarian and uterine volume remained within normal range (< 2 standard deviation scores) after discontinuation of treatment. Follicles and macrocysts regressed during treatment. None of the girls’ ovaries had a polycystic appearance during or after treatment with the gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue. These results confirmed PU as a reliable tool for investigation of internal genitalia in girls with PP and as a valid method for evaluation of the efficacy of treatment with GnRHa (53). Repeated investigations should be performed when evaluating treatment because during treatment with a GnRHa changes in uterine size are slow in spite of a satisfactory and rapid control of estrogen secretion (54).

Conclusion

PU examination can be used as an auxiliary means to distinguish normal girls from those with varying degrees of precocious puberty andmay serve as a useful preliminary step in selecting patients who require GnRH testing. Ovarian parameters are sensitive to hormonal stimulation and increase significantly at the early (isolated) stage, whereas cervical length, width, uterine length, endometrial thickness, and average maximum diameter of largest follicle do not increase significantly until at the CPP stage (27).

The combination of GnRH stimulation test and PU can improve the diagnostic accuracy of CPP and, consequently, the indications for an early and appropriate GnRHa treatment. The enlarged uterine length, increased ovarian volume with multiple small follicular cystsand advanced bone age usually represent the exposureto estrogenic effects due to activation of HPG axis.

There is no systematic strategy for monitoring whether adequate suppression of the HPG axis has been achieved in children being treated for CPP (55). Although there is unanimity regarding the value of auxologic indices such as growth velocity, Tanner staging, and skeletal maturation, no agreement exists on the need for biochemical measures of treatment efficacy (56). Although efforts aimed at determining the optimal strategy for monitoring treatment and time for discontinuation of GnRHa therapy are still needed, PU may provide an additional easy, convenient and objective modality for monitoring and assist in adjusting the treatment plan during the GnRHa treatment.

The interpretation of clinical, laboratory and strumental data, in a female with a pubertal disorder, must be performed by an expert pediatric endocrinologist to maximize their diagnostic and therapeutic values.

Conflicts of interest:

Each author declares that he or she has no commercial associations (e.g. consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangement etc.) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

References

- Battaglia C, Mancini F, Regnani G, Persico N, Iughetti L, De Aloysio D. Pelvic ultrasound and color Doppler findings in different isosexual precocities. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22:277–83. doi: 10.1002/uog.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Phillip M. Role of pelvic ultrasound in girls with precocious puberty. Horm Res Paediatr. 2011;75:148–52. doi: 10.1159/000323361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EksiogluAS, Yilmaz S, Cetinkaya S, Cinar G, Yildiz YT, Aycan Z. Value of pelvic sonography in the diagnosis of various forms of precocious puberty in girls. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41:84–93. doi: 10.1002/jcu.22004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcaterra V, Klersy C, Vinci F, et al. Rapid progressive central precocious puberty: diagnostic and predictive value of basal sex hormone levels and pelvic ultrasound. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;33:785–91. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2019-0577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chittwar S, Shivprakash, Ammini AC. Precocious puberty in girls. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2012;16:S188–91. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.104036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt AA, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Idiopathic precocious puberty in girls: long-term effects on adolescent behavior. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1986;279:247–53. doi: 10.1530/acta.0.112s247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner R, Adan L, Malandry A, Zantleifer D. Adult height in girls with idiopathic true precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:415–20. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.2.8045957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kletter GB, Klech RP. Clinical review 60: effects of gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue therapy on adult stature in precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1994;79:331–4. doi: 10.1210/jcem.79.2.8045943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badouraki M, Christoforidis A, Economou I, Dimitriadis AS, Katzos G. Evaluation of pelvic ultrasonography in the diagnosis and differentiation of various forms of sexual precocity in girls. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008;32:819–27. doi: 10.1002/uog.6148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eugster EA. Update on Precocious Puberty in Girls. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2019;32:455–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpag.2019.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khokhar A, Mojica A. Premature thelarche. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47:e12–5. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20171214-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novello L, Speiser PW. Premature adrenarche. Pediatr Ann. 2018;47:e7–11. doi: 10.3928/19382359-20171214-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuqua JS. Treatment and outcomes of precocious puberty: An update. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98:2198–207. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield RL, Cooke DW, Radovick S. Sperling MA. Pediatric Endocrinology. 4th ed. Vol. 15. Saunders Elsevier: 2014. Puberty and its Disorders in the Female; pp. 612–5. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin IJ, Duncan KA, Hollman AS, Donaldson MDC. Pelvic ultrasound findings in different forms of sexual precocity. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:544–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buzi F, Pilotta A, Dordoni D, Lombardi A, Zaglio S, Adlard P. Pelvic sonography in normal girls and in girls with pubertal precocity. Acta Pædiatr. 1998;87:1138–45. doi: 10.1080/080352598750031121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber HP, Wollman HA, Ranke MB. Pelvic sonography: early differentiation between isolated premature thelarche and central precocious puberty. Eur J Pediatr. 1995;154:182–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01954267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banker, Cohen HL, Sandhu PK. Sonography Pediatric Gynecology Assessment, Protocols, And Interpretation. In Stat Pearls Publishing. Treasure Island (FL): 2021. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprio MG, Di Serafino M, De Feo A, et al. Ultrasonographic and multimodal imaging of pediatric genital female diseases. J Ultrasound. 2019;22:273–89. doi: 10.1007/s40477-019-00358-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaum AR, Sanders RC, Jones MD. Neonatal uterine morphology as seen on realtime US. Radiology. 1986;160:641–3. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.3526401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holm K, Laursen EM, Brocks V, Muller J. Pubertal maturation of the internal genitalia: an ultrasound evaluation of 166 healthy girls. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:175–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.1995.06030175.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges NA, Cooke A, Healy MJR, Hindmarch PC, Brook CGD. Standards for ovar-ian volume in childhood and puberty. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:456–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantas-Orsdemir S, Eugster EA. Update on central precocious puberty: from etiologies to outcomes. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2019;14:123–30. doi: 10.1080/17446651.2019.1575726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sathasivam A, Rosenberg HK, Shapiro S, Wang H, Rapaport R. Pelvic ultrasonography in the evaluation of central precocious puberty: comparison with leuprolide stimulation test. J Pediatr. 2011;159:490–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienkowski C, Cartault A, Carfagna L, et al. Ovarian cysts in prepubertal girls. Endocr Dev. 2012;22:101–11. doi: 10.1159/000326627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sanctis V, Corrias A, Rizzo V, et al. Etiology of central precocious puberty in males: the results of the Italian Study Group for Physiopathology of Puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2000;13:687–93. doi: 10.1515/jpem.2000.13.s1.687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen X, Wen D, Zhang H, Zhang H, Yang Y. Observational study pelvic ultrasound a useful tool in the diagnosis and differentiation of precocious puberty in Chinese girls. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018;97:e0092. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Shin HY, Lee SH, Kim YS, Kim JH. Usefulness of pelvic ultrasonography for the diagnosis of central precocious puberty in girls. Korean J Pediatr. 2015;58:294–300. doi: 10.3345/kjp.2015.58.8.294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haber HP, Mayer EI. Ultrasound evaluation of uterine and ovarian size from birth to puberty. Pediatr Radiol. 1994;24:11–3. doi: 10.1007/BF02017650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin IJ, Cole TJ, Duncan KA, Hollman AS, Donaldson MD. Pelvic ultrasound measurements in normal girls. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:536–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13689.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Horev G, Schwartz M, Phillip M. Ultrasonographic and clinical parameters for early differentiation between precocious puberty and premature thelarche. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;154:891–8. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.02151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu HK, Liu X, Chen JK, Wang S, Quan XY. Pelvic Ultrasound in Diagnosing and Evaluating the Efficacy of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Therapy in Girls With Idiopathic Central Precocious Puberty. Front Pharmacol. 2019;10:104. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2019.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang HJ, Nam JS, Cho WK, Cho KS, Park SH, Jung MH, et al. Pelvic ultrasonography findings in girls with precocious puberty. J Korean Soc Pediatr Endocrinol. 2010;15:126–32. [Google Scholar]

- Herter LD, Golendziner E, Flores JA, et al. Ovarian and uterine findings in pelvic sonography: comparison between prepubertal girls, girls with isolated thelarche, and girls with central precocious puberty. J Ultrasound Med. 2002;21:1237–46. doi: 10.7863/jum.2002.21.11.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binay C, Simsek E, Bal C. The correlation between GnRH stimulation testing and obstetric ultrasonographic parameters in precocious puberty. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2014;27:1193–9. doi: 10.1515/jpem-2013-0363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SH, Joo EY, Lee JE, Jun YH, Kim MY. The Diagnostic Value of Pelvic Ultrasound in Girls with Central Precocious Puberty. Chonnam Med J. 2016;52:70–4. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2016.52.1.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paesano PL, Colantoni C, Mora S, et al. Validation of an Accurate and Noninvasive Tool to Exclude Female Precocious Puberty: Pelvic Ultrasound With Uterine Artery Pulsatility Index. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213:451–7. doi: 10.2214/AJR.18.19875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziereisen F, Heinrichs C, Dufour D, Saerens M, Avni EF. The role of Doppler evaluation of the uterine artery in girls around puberty. Pediatr Radiol. 2001;31:712–9. doi: 10.1007/s002470100463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battaglia C, Regnani G, Mancini F, Iughetti L, Venturoli S, Flamigni C. Pelvic sonography and uterine artery color Doppler analysis in the diagnosis of female precocious puberty. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002;19:386–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-0705.2002.00669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garibaldi LR, Aceto T, Jr, Weber C, Pang S. The relationship between luteinizing hormone and estradiol secretion in female precocious puberty: evaluation by sensitive gonadotropin assays and the leuprolide stimulation test. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1993;76:851–6. doi: 10.1210/jcem.76.4.8473395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N, Pinneau SR. Tables for predicting adult height from skeletal age: Revised for use with the Greulich-Pyle hand standards. J Pediatr. 1952;40:423–41. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(52)80205-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arrigo T, Cisternino M, Galluzzi F, et al. Analysis of the factors affecting auxological response to GnRH agonist treatment and final height outcome in girls with idiopathic central precocious puberty. Eur J Endocrinol. 1999;141:140–4. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1410140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaac H, Patel L, Meyer S, Hall CM, Cusick C, Price DA, Clayton PE. Efficacy of a monthly compared to 3-monthly depot GnRH analogue (goserelin) in the treatment of children with central precocious puberty. Horm Res. 2007;68:157–63. doi: 10.1159/000100579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KA, Eugster EA. Experience with the once-yearly histrelin (GnRHa) subcutaneous implant in the treatment of central precocious puberty. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2009;3:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahhal S, Clarke WL, Kletter GB, et al. Results of a second year of therapy with the 12-month histrelin implant for the treatment of central precocious puberty. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2009;2009:812517. doi: 10.1155/2009/812517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein KO, Lee PA. Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRHa) Therapy for Central Precocious Puberty (CPP): Review of Nuances in Assessment of Height, Hormonal Suppression, Psychosocial Issues, and Weight Gain, with Patient Examples. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev. 2018;15:298–312. doi: 10.17458/per.vol15.2018.kl.GnRHaforCPP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries L, Phillip M. Pelvic ultrasound examination in girls with precocious puberty is a useful adjunct in gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analogue therapy monitoring. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2011;75:372–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04086.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel JC, Lahlou N, Jaramillo O, et al. Treatment of central precocious puberty by subcutaneous injections of leuprorelin 3-month depot (11.25 mg) J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87:4111–6. doi: 10.1210/jc.2001-020243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weise M, Flor A, Barnes KM, et al. Determinants of growth during gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogue therapy for precocious puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89:103–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall DA, Crowley WF, Wierman ME, Simeone JF, McCarthy KA. Sonographic monitoring of LHRH analogue therapy in idiopathic precocious puberty in young girls. J Clin Ultrasound. 1986;14:331–8. doi: 10.1002/jcu.1870140503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manasco PK, Pescovitz OH, Hill SC, et al. Six-year results of luteinizing hormone releasing hormone (LHRH) agonist treatment in children with LHRH-dependent precocious puberty. J Pediatr. 1989;115:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(89)80341-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino MM, Hernanz-Schulman M, Genieser NB, Sklar CA, Fefferman NR, David R. Monitoring of girls undergoing medical therapy for isosexual precocious puberty. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13:501–8. doi: 10.7863/jum.1994.13.7.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AM, Brocks V, Holm K, Laursen EM, Müller J. Central precocious puberty in girls: internal genitalia before, during, and after treatment with long-acting gonadotropin-releasing hormone analogues. J Pediatr. 1998;132:105–8. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(98)70493-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner R, Hauschild MC, Pariente D, Thibaud E, Rappaport R. Role of pelvic ultrasonography in the diagnosis, therapeutic indications and surveillance of central precocious puberty. Arch Fr Pediatr. 1986;43:601–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely EK, Silverman LA, Geffner ME, Danoff TM, Gould E, Thornton PS. Random unstimulated pediatric luteinizing hormone levels are not reliable in the assessment of pubertal suppression during histrelin implant therapy. Int J Pediatr Endocrinol. 2013;2013:20. doi: 10.1186/1687-9856-2013-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carel JC, Roger M, Ispas S, et al. Final height after long-term treatment with triptorelin slow release for central precocious puberty: importance of statural growth after interruption of treatment. French study group of Decapeptyl in Precocious Puberty. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:1973–8. doi: 10.1210/jcem.84.6.5647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]