Abstract

In order to effectively evaluate complex interventions, there have been calls for the further integration of qualitative methods. Qualitative process studies of brief alcohol interventions and medicines reviews are notably lacking. This article provides a grounded example through the presentation of findings from an embedded qualitative process evaluation of a multi-site, pilot cluster RCT of a new intervention: the Medicines and Alcohol Consultation (MAC). MAC is designed to increase the capacity of community pharmacists (CPs) to conduct person-centred medicines reviews in which the subject of alcohol consumption is raised in connection with medications and associated health conditions. Participant-focused qualitative studies (interviews, observations, recorded consultations) sought to understand how CPs engaged with and implemented MAC in context. This article documents effects of the intervention on developing person-centred consultation practice and highlights how qualitative process studies can be used formatively to develop middle range programme theory and to optimise intervention design for testing in a definitive RCT.

Keywords: Qualitative process evaluation, Complex intervention, Person-centred, Alcohol, Pharmacy

Highlights

-

•

Reconciling context with content is important when developing complex interventions.

-

•

Process evaluations of brief alcohol interventions are notably lacking.

-

•

These can be used formatively to develop intervention theory and optimise design.

-

•

Several participant-focused qualitative data sources can be usefully integrated.

-

•

Pharmacists found person-centred consultation practice development challenging.

1. Introduction

High quality process evaluations are used to inform the interpretation of the outcomes of randomised controlled trial (RCTs) of complex interventions where there is often a long causal chain (Ling, 2012; Moore et al., 2014, 2015; Oakley et al., 2006). This includes attempts to change health professional behaviours in various settings (Grant, Treweek, Dreischulte, Foy, & Guthrie, 2013; Grimshaw et al., 2007; Hulscher, Laurant, & Grol, 2003). For example, process studies have examined how health professionals tailor complex interventions to their practice needs (Jansen et al., 2007; May et al., 2007). There have been calls for the further integration of qualitative methods in order to evaluate such interventions more effectively (Cheng & Metcalfe, 2018; Lewin, et al., 2009; Mannell & Davis, 2019; Rapport et al., 2013), and for the use of more innovative qualitative methods (Davis et al., 2019). In the alcohol research field, there is a gap in knowledge about how brief interventions are actually delivered in routine practice and how this connects to the effects seen in randomized trials (McCambridge, 2021). These aspects, the ‘mechanisms of action’, have not been investigated in process studies (Gaume, et al., 2014).

The first phase of the five-year research programme ‘Community pharmacy: Highlighting Alcohol use in Medication Appointments’ (CHAMP-1) used qualitative participatory methods to gather patient and pharmacist perspectives on acceptability and suitability of the proposed Medicines and Alcohol Consultation (MAC) intervention for use within routine practice in established pharmaceutical services (Madden, et al., 2020; Morris, et al., 2019; Madden, Morris et al., 2020; Madden et al., 2021). This formed part of a 15 month intervention development process to prepare the intervention for study in a RCT. The MAC aims to increase the capacity of community pharmacists (CPs) to conduct person-centred medicines reviews, in which the subject of alcohol consumption is raised with drinkers in connection with their medications and the conditions for which these are being taken. Interventions are often discussed in terms of discrete components or actions. This intervention is conceptualised not as a set of discrete actions but as an active process of skills development that aims to enhance person-centred medicines review practice and permit an open discussion of the sensitive topic of alcohol use. How the process of enhancing person-centredness comes together during an intervention is what makes this complex to study. The process has to be flexible enough to adapt to the complexities of the systems in which it will be introduced (Hawe et al. 2004). Earlier qualitative studies in the programme identified a gap between everyday practice in community pharmacy and continuing professional training provision, which although promoting concepts of patient-centred practice was limited with regards to supporting actual skill acquisition (McCambridge et al., 2021). There was, therefore, more to do than originally anticipated when designing the intervention. A previously unplanned process evaluation was therefore conducted during the pilot trial in order to finalise the intervention and its underpinning theory.

This article reports on this embedded qualitative process evaluation of a multi-site, pilot cluster RCT of the first full iteration of the MAC in routine community pharmacy medicines review practice in England (Stewart et al., 2020). Participant-focused qualitative studies sought to understand how CPs engaged with and implemented the MAC in order to develop middle range programme theory (Kislov et al., 2019) and optimise intervention design for testing in a definitive RCT. The pilot process evaluation was formative, i.e., it was used in the building stage of the intervention rather than for the more usual post-hoc understanding of RCT outcomes. The experience of using process study methods in the pilot will also inform the study design of the full RCT process evaluation. The focus of reporting here is on understanding the effects and limitations of the intervention in respect of CP practice and the use of findings to refine thinking about the causal assumptions underpinning the intervention. The article provides an empirically grounded example of the use of qualitative methods in a pilot RCT to further develop the design and model the logic of a complex intervention which adapts to context (Mills et al., 2019). In so doing, it provides a clear description of the pilot intervention in light of criticism of brief alcohol interventions in general that intervention content is underreported and under-theorised (McCambridge, 2013; Candy et al., 2018).

1.1. Community pharmacy medicines review context

Reviews conducted in NHS Community Pharmacies at the time of the pilot trial (April to October 2019) included the Medicines Use Review (MUR) and the New Medicines Service (NMS). A ‘healthy-living advice’ component was added to each in 2012 and 2013 respectively. This means pharmacists are expected to advise on alcohol, smoking, physical activity, nutrition, weight management and/or sexual health (Pharmaceutical Services Negotiating Committee (PSNC) and NHS Employers, 2012). Guidance for CPs uses the term ‘patient-centred’, as does the wider literature on interventions to promote enhanced consultation skills in health care practice (Balint, 1957; Dwamena et al., 2012). General Pharmaceutical Council Standards for Pharmacy Professionals (2017) uses the term ‘person-centred’ care. All stress placing the interests and perspectives of the patient at the heart of patient consultations designed to promote shared decision making and informed choice (NICE guideline 5, 2015).

CPs delivering MUR and NMS are required to be accredited in patient-centred consultation skills (Jee et al., 2016). Distance learning has been available via the Centre for Pharmacy Postgraduate Education (CPPE) since 2014 (CPPE, 2014). CPPE training materials describe a model of ‘patient-generated problem solving’, with the aim of encouraging patients to “tell their story” rather than answering a list of questions (CPPE, 2012). Before undertaking medicines reviews independently, CPs must complete a competency self-assessment based on the Medication Related Consultation Framework (MRCF) (Abdel-Tawab et al., 2011).

A scoping review of the MUR and NMS literatures found that few studies evaluated outcomes of MURs or the NMS (Stewart, et al., 2019). To date only one RCT (of NMS) has been conducted (Elliott et al., 2016), in addition to a few qualitative observational studies (Atkin et al., 2021; Morris et al., 2019). Most research is retrospective and based on recall of what happens in consultations. Beyond the MUR and NMS, there is limited evidence of the effectiveness of any intervention to enhance medication adherence, hence the need for improved design of interventions and measures to detect improvements in patient-important clinical outcomes (Nieuwlaat et al., 2014).

Alcohol poses a range of potential risks for people taking medications; directly via its impact on health and well-being and indirectly by potentially reducing adherence to, or the safety and effectiveness of, pharmaceutical treatments (Madden et al., 2019; Stewart & McCambridge, 2019). CPs and other health professionals report a lack of confidence in how to approach the subject of alcohol and their role in doing so (Morris et al., 2019; Moriarty et al., 2011; Rapley et al., 2006). The only guidance currently available to CPs is on alcohol screening and brief intervention, which has been found to offer no benefit to patients in community pharmacies (Dhital et al., 2015). Development of the MAC has been informed by the null findings of that RCT and wider calls to rethink brief interventions for alcohol by locating conversations about drinking within the actual settings and services accessed by patients (rather than as standalone decontextualized interventions); and addressing issues that matter to patients (McCambridge, 2021;McCambridge & Rollnick, 2014; McCambridge & Saitz, 2017; Glass et al., 2017). The piloted version of MAC frames alcohol as a drug consumed alongside other drugs and therefore within the CP's sphere of expertise. This moves way from the more familiar framing of alcohol as a ‘lifestyle’ issue to one directly linked to medicines use, safety and effectiveness - and the conditions for which medications are prescribed (Madden et al., 2021).

2. Methods

Before describing the methods for the embedded participant-centred process studies, we briefly describe the intervention studied and the pilot RCT design.

2.1. Intervention delivery

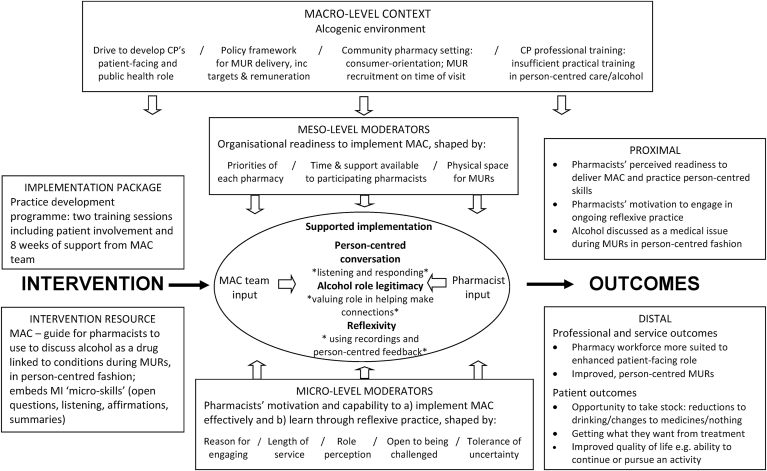

The MAC programme comprised eight weeks of practice development support and is summarised in Fig. 1. The hypothesised ‘active ingredients’ are those elements used by each CP to achieve greater skill in person-centred consultations which include attention to alcohol, and their application within individual medicine reviews. These elements are expected to vary for each individual practitioner and patient. Complexity arises from the difficulty to be precise about what these ‘active’ ingredients are and how they affect outcomes for patients following an interaction between a community pharmacist and a person in a medicines review (Campbell et al., 2000).

Fig. 1.

CHAMP-1 intervention model.

The first training day used interactive sessions with patients (recruited from the CHAMP-1 patient and public involvement group). It focused on core person-centred consultation skills, particularly open questions, using the MAC in consultations and preparation of a Practice Development Plan (PDP). A four-page paper-based MAC guide summarising the structure of the MAC approach and core content within consultations was provided, together with an A4 booklet of learning support and supplementary materials, the MAC resource. The MAC guide provided a simple ‘steps’ structure (six steps) within which the CP could flexibly organise the consultation to be responsive to patient agendas and explore possible connections between alcohol consumption, medicine use and health (conditions and adherence) (MACA). Use of the MAC guide was underpinned by the particular basic counselling microskills that are emphasized in Motivational Interviewing (MI): open-ended questions, reflective listening statements, summaries, and affirmations communicating a strengths-based view of the patient (Miller & Rollnick, 2012). These are offered here as basic communication tools to facilitate more person-centred consultations; these elements are not at all unique to MI, and the advanced features which are specific to the MI approach are not included within the MAC. At the end of the first training day, CPs were encouraged to initiate peer support through buddying and the use of a WhatsApp group. Individually tailored practice development support visits and telephone calls were provided by the MAC support team after the training day. These followed a protocol designed to facilitate a practitioner-centred approach to practice development, aiming to mirror the person-centred approach, and model the core consultation microskills presented in the MAC programme.

A second training day, four weeks later, focused on the key issues identified in early use of the MAC in practice and more advanced person-centred skills, such as reflective listening and case studies of challenging issues. This was followed by more on-site and remote support, including feedback on audio-recorded MAC consultations (with patient consent); and discussions of evolving practice development issues within particular contexts. Key to the support process was playback of selected sections of recorded consultations, particularly including their use of the core microskills to facilitate a patient-led agenda and progression through the MAC steps. There was no formalised evaluation of individual practitioner's skills. Instead, there was an open discussion about readiness of practice for the RCT in light of the outcomes detailed in Box 1. The programme was not focused on the attainment of particular skill-based criteria, but on developing skillfulness as far as was feasible within the given context.

Box 1. MAC programme practice development outcomes.

At the conclusion of the practice development programme, we are aiming for practitioners to:

-

1.

Have developed deeper person-centred consultation skills including through proficient use of counselling microskills and engagement with the MAC steps

-

2.

Be able to use person-centred consultation skills in routine practice to support patients in making use of services provided to benefit their health

-

3.

Be able to integrate an appropriate degree of attention to alcohol within consultations

-

4.

Regard it as good pharmacy consultation practice to explore medicine use, conditions and alcohol in a person-centred way

-

5.

Value medication services as providing important opportunities to help patients manage their chronic conditions, and derive the optimal benefits from medications prescribed

-

6.

Have changed consultation practice away from being a quick check of narrowly focused medication-related issues so that it is not an information-dominated process

-

7.

Manage consultations efficiently and flexibly using the structure provided by the MAC steps

-

8.

Be able to recognise challenging issues in practice, identifying needs for skills development, and formulate plans to address them in the context of continuing professional development (CPD)

-

9.

Be confident that they are developing patient-centred consultation skills and that further close attention to practice, with support, will develop them further

-

10.

Be committed to further developing patient-centred consultation skills, including using CPD opportunities

Alt-text: Box 1

2.2. Pilot RCT design

The pilot RCT trial was conducted in 10 community pharmacies within Yorkshire, UK. The multi-stage recruitment process aimed to assess the motivation, commitment and capacity to participate of one CP from each participating pharmacy. A payment was made to each participating site. Five CPs from pharmacies randomised to the intervention arm participated in the practice development programme and delivered the MAC intervention in MUR and NMS consultations. Five CPs randomised to the control condition continued to provide the MUR and NMS as usual, and to recruit participants to the pilot RCT in the same manner as the intervention arm. Full details of trial design, outcomes and CP engagement with recruitment processes are reported elsewhere (Stewart et al., 2020; Stewart et al., 2021). The trial was registered with the ISRCTN registry (ISRCTN57447996). The trial and embedded process studies received NHS research ethics approval (REC reference19/SW/0082). All participants provided written consent before each study.

2.3. Embedded participant-centred process studies

Embedded studies sought to explain variation in the ways CPs engaged with and implemented MAC in practice from their points of view. Fieldwork was conducted by qualitative researchers (a sociologist and an anthropologist) working within a multidisciplinary team. After the first training session, two out of five CPs were purposively sampled (based on receptivity to the programme, accessibility and baseline skills) to take part in a series of semi-structured 30–60 min face-to-face interviews over three time points as they progressed through phase one and phase two of the MAC skills development process. Only one of five CPs agreed to take part (all five were eventually approached). Those who refused gave the additional time commitment as a reason. Interviews with the one participating CP provided insight into an individual pharmacist's engagement with the MAC practice development process and how the elements of the intervention combined in their experience over time. Contemporaneous notes of observation of CP engagement and discussion at the two MAC training days were used to develop topic guides for these interviews and for a semi-structured, audio-recorded 45–60 min face-to-face exit interview with each CP at the end of the study period. These interviews explored CP understanding of the purpose of the MAC; engagement with the skills development programme; experience of delivering MAC in routine medicines review practice; views on the outcomes of the development programme for their own practice; and the potential for MAC to improve outcomes for patients.

All five CPs were given audio-recording equipment and asked, with patient permission, to record samples of consultation practice during the training period. Three CPs made recordings. This permitted in-depth attention to what CPs and patients actually did during consultations. In addition, during the pilot RCT period, CPs were asked to provide one audio recording of a MAC consultation at each intervention site (after they had time to develop their practice), where the patient agreed to take part in a follow up audio-recorded semi-structured telephone interview within a week of their consultation. Patients in the recorded consultations were interviewed and asked about their interaction and the acceptability of MAC service delivery. Patients received a £10 shopping voucher for participating in the interview.

Where possible, practitioners' reports of practice development were triangulated with material from interviews with patients and with audio-recordings of consultation practice. The patient interviews provided a commentary on their interaction with pharmacists, including the extent it could be regarded a patient-centred, while the audio recordings enabled the research team to explore how pharmacists used their ‘new’ learned skills when communicating with patients. There were fewer process study recordings of consultation practice than planned, although two rich case studies were achieved. This enabled comparisons of MAC conduct with post-hoc reflections (reported separately). The dataset also included fieldnotes from direct observation of five medicine reviews conducted by one CP in the intervention arm during early recruitment and support visits. These observations were guided by a checklist (see appendix).

Interview transcripts and observation data were organised using a modified framework method (Gale et al., 2013) and analysed using constructionist thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Consultation audio-recordings were explored using a form of adapted conversation analysis (CA), which balanced CA specific approaches with those derived from wider discourse analytic approaches (Quirk et al., 2013). Finally, data from these studies were also contextualised by material collected by pilot trial research support staff. This further enriched understanding of CP engagement with intervention processes and pharmacy context. The analysis presented here focuses on CP perspectives of their own person-centred consultation practice development from the interviews with some contextualisation from the wider dataset available. Findings from the different datasets (exit and longitudinal interviews with pharmacists and patients; observation; audio-recording; material collected by pilot trial research support staff) were used to create a preliminary logic model dynamic enough to capture and express the intervention's functioning in its delivery settings (Mills et al., 2019).

Five CPs, three women and two men aged between 25 and 63 years (mean 41), with a range of experience and roles participated in the intervention arm at five sites, which included pharmacy independents and multiples. All worked full time as CPs and had been qualified for between two and 40 years (mean 17) (see Table 1). Four of the five CPs said they drank alcohol, with frequency ranging from once a week to once or twice a month. All five CPs participated in exit interviews and one CP was interviewed three further times, shortly after each training day. Four of the five CPs had varying degrees of managerial responsibility, and there were variations in the workplace support offered to facilitate engagement in the RCT.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the interview sample.

| CP | Sex | Age | Ethnicity (self-described) | Time qualified (years) | IMDb | IMD decile | Rural/Urban | Role | RCT MAC (n) | Data seta |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | M | 48 | White British | 25 | 15,877 | 5 | Urban | Pharmacy proprietor | 4 | INT OBS |

| 11 | M | 63 | White British | 40 | 28,902 | 9 | Rural | Superintendent Pharmacist | 4 | INT AUD PP |

| 12 | F | 25 | British Pakistani | 2 | 27,456 | 9 | Rural | Pharmacist manager | 2 | INT |

| 13 | F | 42 | White Polish | 13 | 22,544 | 7 | Urban | Pharmacist | 8 | INTx4 AUD PP |

| 14 | F | 27 | White British | 4 | 29,760 | 10 | Urban | Superintendent Pharmacist | 6 | INT AUD |

INT = interview; OBS = observation; AUD = Audio-recording; PP = patient perspective.

English indices of multiple deprivation.

A CP without managerial responsibility (INV13) and a proprietor of a small chain (INV10), were resourced to have another CP on duty so they could conduct medicines reviews throughout the RCT. Another CP (INV14) had cover for only part of the time. She conducted reviews across two pharmacies. The pressure of her managerial tasks meant she had less time for reviews towards the end of the RCT. A CP (INV12) in a quiet pharmacy with little footfall and a consultation room undergoing refurbishment conducted few consultations. The other CP without cover (INV11) reported concerns from colleagues about spending additional amounts of time in the consultation room when needed in the dispensary.

Examples of recorded or observed consultation practice were obtained for four of the five CPs. MAC consultations were predominantly conducted in MUR rather than NMS reviews. NMS played a less significant part of practices’ business model, so were conducted less frequently and routinely comprised brief telephone calls or chats at the pharmacy counter.

3. Results

At their exit interviews all CPs reported developing deeper person-centred consultation skills and using these in their practice, in particular asking open questions and listening to patients. They said they were more confident to raise alcohol within medicines reviews and had received no negative feedback from patients when doing so.

As expected, our material highlighted variability in how practitioners engaged with the MAC programme and delivered it in practice, together with the demands of the research. There were varying degrees of: ability or willingness to pay close attention to developing one's own practice; proficiency in using counselling microskills; the ability to structure a consultation using the MAC steps; attention given to alcohol and ability to help people connect alcohol to their medications and conditions. In their interviews, there were differences in CPs' expressed motivations to change their practice and on sustaining changes to practice after the RCT. Two of the five CPs who showed most ability or willingness to engage in detailed reflection on their own practice were most able to demonstrate a developing proficiency in microskills and discussing alcohol (INV13 and INV14). Our findings are presented to describe the micro and meso level contextual factors that pharmacists identified as shaping their motivation and capability to implement person-centred conversations about alcohol, and how they learned through reflexive practice.

3.1. Motivations for taking part

When asked what motivated them to take part, the most recently qualified CP (INV12) said she saw this as a training opportunity to complement other ongoing skills training and a chance to develop her experience. The longest serving CP framed his motivation in terms of improving MURs generally:

A lot of the time [the MUR] was just a ‘how are you getting on with this … is … everything okay’, and it just sort of meandered along … the questions about lifestyle and things were the ones that tended to get pushed to the end of the ‘normal’ MURs and sometimes forgotten completely. Especially, the focus on the alcohol situation … So, that's the main reason … the general improvement of MURs … better for me, better for the patient (INV 11).

For another CP it was a matter of a general interest in taking part in research and a timely opportunity to “participate in something new” (INV 13). The other two CPs described a combination of motivations to develop their own skills and their businesses. One of these CP also said she had a personal interest in research. Her pharmacy group were always looking for opportunities to become involved in projects and given the financial climate for ‘independents’, the facilitation fee was also attractive. A CP who was the proprietor of a small chain (INV10) said he wanted to develop his consultation skills and the alcohol element might be useful for a recently commissioned pharmacy service to an alcohol rehabilitation unit. He said he decided to participate himself rather than delegating to those who routinely did MURs to avoid placing additional pressure on them.

3.2. Engaging with training and identifying issues in own practice

All CPs said they found the process of actively identifying issues in their individual practice, in order to develop their skills, challenging. Some enjoyed this challenge more than others. The most enthusiastic CP said:

… It was a challenge … and that's what I thought was so good about it … I remember thinking, oh, this is going to be quite an easy day today, you know, out of the office … I can just sit and listen for a little bit and then try and apply what was learnt … [it was] so much more difficult than I thought … It was nerve-racking to do but it was really good … I always thought I was quite good at consultations … my favourite part of being a pharmacist is talking to patients … and I've had good feedback about it before so I thought … I bet I'll be okay but … there were so many things that we were told that we could be doing differently I thought, well, actually this is really, really valuable … if I had the opportunity to pay for those kind of two training days … I would … and recommend other people did … I genuinely have changed my practice and my consultation skills as a result of it (INV 14).

She said she felt the training had, “pushed [me] hard … out of my comfort zone”. She and the other CP who was most engaged with the programme described how this training differed from previous consultation skills training, especially in working with real patients, working in front of peers and receiving detailed feedback. Previous training:

… was just basically watching videos, and seeing … what the good practice is … so … I was familiar with the topic … But it's a different thing, just watching videos, and different practising yourself … [online] gives you an idea what the consultation … should look like … that's just the theory, you just read about it, you don't practice it, so it's completely different (INV 13-1).

These CPs said they valued direct feedback from facilitators and from patients:

It was great to get their [patient] feedback about what they liked … that made me feel really motivated because … that makes me think it will be good in real life. It's not just what the facilitator wanted me to say … [I]n undergraduate study … I did a lot of these actor based consultations so you kind of know what they've been told to say and then you can prepare accordingly. Whereas with a patient obviously they can go off and say whatever they like … so it was much more true to life (INV 14).

All CPs found the focus on improving consultation practice by trying things out with patients and peers and receiving detailed feedback challenging. At times they spoke as if this was a wholly new skill-set rather than an extension of existing skills. One CP described the training days throwing everything “in the air” and then being “let loose” in practice:

I found it completely refreshing around challenging the way that we communicate with patients. I very much drove the agenda in people's consultations on what I wanted to get out of it. What I think the MAC gave me was the confidence to have [a] slightly uncomfortable time … Open questions, awkward silences, those things were just a revolution to me … I feel I'm a better clinician for that (INV 10).

Although a challenge for all of the CPs, the most newly qualified and longest serving CPs expressed most discomfort with the “scrutiny” and being “thrown in at the deep end” in practising consultations in front of their peers:

Initially they were scary … real patients … came in, and we had to actually consult with them in groups, especially doing it in front of other people, I wasn't used to that … it was a bit much … But, looking back, I'm glad … it really helped. Especially with my confidence … I think they threw us in at the deep end, but it was good … you're being put on the spot … Nerve-racking … (INV 12).

The longest serving CP said he found it interesting to see how responses in consultations could differ by, “changing the way that things were approached” (INV 11). He usually approached consultations with a “set plan” and he found the group consultation exercises where CPs had to pick up the thread from each other particularly stressful:

It was a foreign institution to us … I appreciate … the only way you're ever going to improve is to actually practice them … it's just you feel a bit under scrutiny … with people watching you from all sides. I felt a bit under pressure … (INV 11).

As well as discomfort at being ‘put on the spot’, CPs were not used to handing over some control of the consultation and listening to patients in the ways encouraged. After the second training day this CP felt she had made progress and then reflected back on how the two days had fitted together:

I felt really good after it [second day]. We were equipped with some tools how to manage the conversation … I knew that I definitely need to think how to explore things … but these exercises definitely helped … after the second training day I had the impression that we all have to stop ourselves from talking. I even have a feeling that I shouldn't really give any advice unless they ask … It's uncomfortable. Because you want to say what they're doing wrong … But, I understand why. I understand the shared agenda (INV 13-2).

The CPs identified the key messages from the training days as the need to develop microskills to change their practice for patient benefit and cede more control of the agenda to patients:

… make the patient the centre of the consultation … to not go through a checklist when you're actually doing the consultations and let them take the lead … I don't think my consultations were terrible before … but what they got out of it was what I wanted them to get out of it, as opposed to what they would want to get out of it, and I think that's the main difference (INV 14).

The two CPs who engaged most with MAC support (INV13 and INV14) said they were letting go of the idea that it was the CP's responsibility to change patients' behaviours by telling people what they should be doing. This was helping to make them feel more relaxed with people in consultations: “I feel more relaxed now, that I don't have to change the behaviour” (INV 13-4). This sense of duty to act on rather than with the patient is reinforced in the MUR worksheet, which includes boxes for pharmacists to tick on a range of medicines related information and behaviours: “the pharmacist believes there will be an improvement in the patient's adherence as a result of better understanding/reinforcement” (PSNC, 2020).

3.3. Engagement with MAC support and practice recording

CPs said they did not directly refer back to their written personal development plans. They saw these as less helpful than talking about their practice with MAC training and support staff:

I can't say that I've necessarily revisited it … I'm notoriously bad at doing those plans … I've never referred back to that written development plan (INV 14).

CPs said they appreciated the support and encouragement from the MAC support staff. They were uncomfortable with the idea of recording consultations initially. Two of the five (INV 10 and INV 12) did not provide any recordings. One of these conducted few MURs due to consultation room refurbishment and said she had missed out on this opportunity to develop her practice (INV 12). The other CP described himself as a bit “technophobic”. He said he feared the recorder would change the dynamics in his consultations (though he did agree to have his early consultations observed) and his concerns were confirmed when the two or three patients he asked about recording said ‘no’:

I had to remember these were my patients, these were my customers, and I didn't want to do anything that was going to upset them (INV 10).

Other CPs who asked patients did not report encountering this difficulty. Two of the three CPs who provided recordings of consultations said they found the discussions they generated with MAC support staff particularly useful (INV13, INV 14). The other CP who provided recordings said he had not listened back to any of them, “so, I have no idea whether they were good, bad or indifferent” (INV 11). He said he liked the general “buoying up” from MAC support staff, who gave useful suggestions and disconfirmed his initial fear that they would “pick apart” his consultations. He was unable to recall any specific examples that had been discussed.

For those who engaged with this part of the process, the initial anxiety about recording consultations lessened over time:

The recording was very stressful … It felt like you had third person on the consultation, so I didn't like that … and I couldn't listen to that recording … we [MAC support] then had a really long chat … At that point I thought it was actually good that people listened to this recording, although it wasn't my best MUR, but he's given me a lot of feedback. He just confirmed what I thought about this conversation … I went into advice without actually … It wasn't consensual … I just sort of did that MUR on autopilot … I was stressed … I wasn't really listening … the second time it wasn't that dramatic … I actually listened to [that] before I sent it off … I'm happy that I [did] those recordings. I don't know if I will become friends with the recorder, but … I don't feel as anxious about recording anymore (INV 13 -3).

The two CPs who made recordings and listened back to them said that the support discussions of their practice were more focused and productive than earlier discussions based on their recalled reports:

… because obviously previously [MAC support] had to get the details of the conversations from me and it was very general, because you don't remember every single detail of the conversation you had with the patient so you can only really speak generally about it (INV 13-4).

The attention to practice afforded by recording was said to be particularly useful for gauging progress and identifying what they were doing well and where they were reverting to previous patterns:

… obviously as time goes by, you forget things and so [MAC support] was kindly reminding me about the whole principle … at first he was telling me to be more brave, pointing out … where I could do it better … Just trying your best … every time he listened to my recordings, it did help because I could reflect on what he was telling me and I could rethink on how I could do it better and then I could practise it on another patient so that was really, really beneficial … It was invaluable … It's when you're practising it in real life, that's when you learn, but then somebody has to assess it for you, if you're meant to progress … it was great, that somebody was listening to our practice … (INV13-4).

Through discussing their recordings, these two CPs (INV 13 and 14) said they realised they were not as proficient in using microskills in practice as they initially thought. They were motivated to do things differently.

3.4. Engagement with peer support and using written resources

The MAC guide was the most used written resource. This was annotated by some CPs and kept in consultation rooms. CPs reported actively consulting the MAC resource pack for information on alcohol and medicines interactions but none had spent much time engaging with the case studies. Others said they found the cases discussed in the training sessions useful but finding the time to read and reflect on them outside of that was challenging. A buddy system and a WhatsApp group were set up to offer peer support but were not used. Reasons included: they were all too busy; they had plenty of support from the research team; they had tried but had received nothing back; and potential discomfort at disclosing struggles with consultations or study recruitment:

Too personal perhaps sometimes, you know, if they feel that everybody else is getting on fine with it and I don't wish to appear that I'm making a right pig's ear of it (INV11).

3.5. Using counselling microskills and the MAC steps

Recordings and observations during the training period show CPs beginning to use open questions to get patients talking and some use of reflections or summaries to prompt people. CPs, however, continued to talk more than patients and listened for opportunities to give information rather than being comfortable taking time to explore patient concerns, which may require longer term practice development. At their exit interviews the CPs said they were now asking open questions and listening more to what patients said. Most offered general statements about listening, not specifically linked to their use of reflection and summary microskills. All agreed that using the microskills and the MAC ‘steps’ structure meant changing their routine approach to MURs. This was not always easy. CPs were also aware that many of the ideas were already identified as good medicines review practice:

It did take a while to get used to using the open questions, like reflecting, summarising, and open question summarising, [which] we were supposed to be doing anyway (INV 12).

The most experienced CP talked about the effort required to move beyond familiarity with the idea and actually acquire the skills:

I think it took me quite a while just to apply them. It wouldn't be common sense just to apply them. It took me quite a few tries … (INV 11).

This CP said he continued to struggle with asking open questions and preferred to stick with some of his previous practice, which worked well for him:

We were encouraged to do the open questions and things like that, which I still struggle with sometimes. I find it's quite difficult to phrase a question in a way to elicit a response, and … sometimes you get a better response from a closed question than you do from an open question. You don't always get a one-word answer (INV 11).

Another CP who did not provide recordings said that his usual practice had involved “half-listening” whilst writing down the key points. He was now trying his best to do reflective listening, maintaining eye contact and summarising, by moving away from checklist driven closed questions. He said he was also holding back on giving information and allowed gaps for the patient to talk:

I used to literally have a pen and paper and would just literally write and half-listen. I don't have any pen and paper [now]. I sit and I listen and I just make sure as soon as that patient's gone, I write it all up then. So I'm trying to do active listening, reflecting, open questions, and just trying to have the eye contact … I realised I wasn't having any eye contact with patients before ‘cause I was concentrating on writing … all I was doing was, this is what I need to get out of the consultation, so I was just ticking as going along and the patient was just a secondary part to that (INV 10).

The two CPs (INV13 and INV 14) who actively engaged with support staff to reflect on excerpts from practice recordings gave examples of how the process helped them to gradually build on listening and summarising skills:

… after having listened to some recordings I just tried to be a bit more adventurous … so [the patient] they'd say something and I'd try and get to the root of what they were saying and then reflect back with that … confirming that I'd actually understood the message behind what they were saying … I didn't really summarise at all previously … to be able to do that … helps me reflect back on the consultation, it helps the patient reflect back … it helps us both … see what we got out of the consultation (INV 14).

The other CP who actively used recordings said that actually listening to patients required greater concentration, so she found herself reverting back to habitual practice unless she made a point of avoiding this, which took effort:

Obviously it requires more focus and concentration from us because you actually have to listen to the patient … if you just ask closed questions they'll just say no [there are no issues/problems]. There's nothing really difficult about that … after the first training day I was trying to listen but I was also processing what I'm going to say next. So I can say that I wasn't really listening. But now I'm just trying to picture what they say, and it comes more natural. It is still not easy … Try to feel the patient more and … picture what they're saying, and that helps you to pick up on these little clues or basically understand them more (INV 13-4).

The youngest CP, with the least experience of doing MURs and the MAC, correctly identified discrepancies with the MUR procedural aspects and expressed doubts about how the MAC steps fitted with the goals of MURs. She was also unpersuaded that this different approach would address reluctance in patients:

… the MAC guide it's good, but … not saying it's not realistic, but with patients' MURs, you don't always get the information you want, or you can't really direct it … It's hard to explain. So, you know you have these like set, open, focus, explore, offer … it just doesn't really flow like that. ‘Cause patients either don't give you enough information, or they don't really want to make a change, and you have to kind of persuade them. But, if they're not really willing to make that change, you can't really explore further, if that makes sense? (INV 12).

This CP described her role still in terms of gathering and issuing information and persuading reluctant patients to change. At other points in the interview, she spoke in person-centred terms about changing her practice to let patients direct the conversation:

But now, I don't concentrate on the questions too much, I let them do more of the talking, and pick up on whatever they say and just direct the conversation … let them direct it, really (INV 12).

The reported extent of progress for all five practitioners, their struggle to develop microskills, and listening in particular, and how this impaired their ability to navigate through the recommended structure is mirrored in data collected by pilot trial research support staff. From a training perspective the difficulties CPs encountered were identified by support staff as reflective of the ambition involved in profoundly revising the communication goals of medicine reviews, ironically to better correspond to the patient-centred ideas espoused in the policy recommendations about how such reviews might be conducted in practice.

3.6. Introducing alcohol into medicines reviews and linking it to medicines and conditions

CPs reported more ability to raise the topic of alcohol but expressed different levels of confidence in how to deal with it discursively. Some continued to focus more on alcohol advice (what they should say) rather than the communicative aspects of the interaction (listening for and exploring patient concerns). While some CPs began to help people make links between alcohol, medications and their conditions, others continued to politely normalise and legitimise drinking, question patients on their knowledge of medicines and alcohol interactions or give information which had not been requested.

3.7. Achieving person-centred practice in a changing role

At their exit interviews, although acknowledging the increasing importance of patient-centred care, CPs identified the key role of the pharmacist as dispensing and conveying information about medicines. The most experienced CP said dispensing was the most important and time-consuming feature of what he did and a more patient facing role would require this key aspect of CP work being covered by someone else:

The government want to put more emphasis on involvement with patients and consultations and things like that. They've actually said they want pharmacists to spend less time dispensing and to be more concentrated on this … patient-facing role, which is fair enough. But obviously, after, there'd be the training of the technicians and the dispensers to … fill … the role that we're vacating (INV 11).

Reflecting on their MAC experience, he and another long serving CP recognised gaps in their communication skills training and experience, which may make it difficult to fulfil a more patient-facing role:

Pharmacists were always hidden around a corner or hidden above and were never meant to be seen … I don't think pharmacists are that good at being good communicators … I certainly didn't at university, have huge amounts of communication consultation skills (INV 10).

At their exit interviews, all CPs said they had more confidence and enthusiasm for talking to patients in a more open way, notwithstanding the wider demands of the role, e.g., the CP above said:

I'm going into the consultation with an open mind and a blank piece of paper, whereas before it was, oh [no] somebody wants to speak to me … So I've taken off the kind of heavy shoulders and I'm going into that to listen … (INV 10).

One CP said she was continuing with the MAC approach because she was enjoying her consultations more and she thought patients were getting more out of them. Another said:

I think [person-centred practice] it's one of those phrases that you certainly hear an awful lot but … [not the] meaning behind it. If you'd asked me before the training, do you give patient-centred care, I'd have said, well, yes, of course I do, but having had the training … I'm doing it an awful lot better now (INV 14).

4. Discussion

The MAC practice development process paid detailed attention to actual practice. This was not what the CPs were used to in training and therefore, was not expected by them. The MAC person-centred approach is consistent with the recommendations in current online CPPE training materials, in presenting a model of ‘patient-generated problem solving’ for medicines reviews (CPPE, 2012). This focus is rooted in research showing that medicines adherence is affected by individual concerns about side effects, dependency, or being unclear about the benefits of prescribed medicines (Britten, 2008; Horne et al., 2013; Pound et al., 2005). NMS was developed as an intervention with a particular theoretical basis in the self-regulatory model of illness. This posits that peoples' illness behaviour is determined by their illness representations formulated from personal experience (physical symptoms and emotions), social and cultural influences, and/or interaction with healthcare providers (Cameron & Leventhal, 2003). Nevertheless, in keeping with our earlier observations, the usual medicines review practice of CPs in this RCT, who had undergone core CPPE training, focused on giving generalised medicines safety information without developing an understanding of the context in which this was received, i.e., how particular patients understood and used their medicines in relation to their concerns, conditions and everyday life. This ensured the focus remained on providing standard information on the safe use of the medicines, completing paperwork and managing time. As in earlier studies of pharmacist-patient communication, while all CPs were skilled in hospitable aspects of ‘social conversation’, listening effectively and eliciting the patient's perspective was limited (Greenhill et al., 2011).

Despite initial discomfort at the attention to detail, those CPs who engaged most actively with MAC in the RCT identified three areas as having the most impact on their consultation practice: feedback from facilitators; feedback from patients in the training session; recording, reflecting on and discussing their practice with MAC support staff. They realised that their snapshot reports of recalled consultations were easily idealised and did not capture what happened in ordinary day-to-day interaction geared towards developing skills in practice. The various skills required to navigate consultations became less elusive, when located in recordings of their practice which exposed the dynamics of interactions. MAC support helped those CPs who engaged with it to identify and gauge differences in their practice over time. This, accompanied by a sense that these CPs were making a difference to patients and enjoying their consultations more, went some way to interrupting the causal mechanisms sustaining the ‘problems’ of usual practice. Other CPs identified preferences for using MAC components, such as asking open questions, and saw some differences with patients, but engaged less with the elements of the MAC process that helped focus on how these actually worked in interaction to make a difference to practice development.

This part of the process evaluation contributed to the intervention development process by providing data on how the intervention was implemented in practice from the perspective of participants. The full dataset is being used to refine the MAC and clarify the causal assumptions and mechanisms through which it is anticipated to produce change in the community pharmacy context. Without qualitative engagement that moves beyond description, or other kinds of process study, RCTs are limited in their explanatory power of whether and how interventions work in complex social systems (Moore et al., 2015, 2018). The intervention once developed is often taken-for-granted, offering a fixed reference point, which is then unquestioned. Here qualitative process studies nested within a RCT-focussed programme were used to demonstrate how the draft intervention actually played out in practice, thus identifying candidates for further developmental work. Findings are being used to refine the MAC components and develop a next stage logic model to capture and articulate thinking about how the MAC can work in context. The latest iteration of the developing dynamic logic model focuses on the CP experience of MAC (Fig. 2). There is further work to be done to model anticipated impact and outcomes from the point of view of the patients in the consultation.

Fig. 2.

Logic model for MAC development programme for community pharmacists (CPs).

5. Conclusion

Although familiar with the concept of person-centred practice, CPs were not expecting, and found challenging, a focus on applying this in detail to their own interactions, including ceding more of the agenda to patients. Consultation skills were developed over time via active learning, including invited examination of, and reflection on, practice following encouragement to embrace a deeper person-centred style within which to identify opportunities to raise alcohol. CPs were more able to use certain person-centred consultation skills in routine practice to varying degrees. However, long standing professional habits and the busy, dispensing-focused, practice context incentivised reverting to more transactional and less person-centred practice (see (Atkin et al., 2021)). Scrutiny of, and feedback on, actual practice with patients have been identified as being likely key mechanisms for further empirical study in the RCT. Taking a more explicitly person-centred approach to the practice support process itself may help to model the approach and mitigate the discomfort some CPs felt at having their practice ‘scrutinised’.

Embedded qualitative process studies were used to refine developing theory of how MAC is anticipated to work within the complex social system of community pharmacy (McCambridge et al., 2021). This will be developed further and tested in a definitive RCT. At this point, it is anticipated that the intervention will work best with CPs who particularly value consultation skills practice development, welcome challenges, are open to this form of support, and are willing and able to move beyond existing understandings of person-centred care and the legitimacy of discussing alcohol, as well as more broadly to experiment with doing things differently.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to the community pharmacists who took part and to the programme patient and pharmacist advisors.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmqr.2021.100012.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Institute for Health Research [NIHR] PGfAR [RP-PG-0216-20002]. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. The Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethical statement

Using qualitative process evaluation in the development of a complex intervention to advance person-centred practice by pharmacists: The Medicines and Alcohol Consultation (MAC).

The RCT and embedded process studies received NHS research ethics approval (REC reference 19/SW/0082). All participants provided written consent before each study.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Abdel-Tawab R., James D.H., Fichtinger A., Clatworthy J., Horne R., Davies G. Development and validation of the medication-related consultation framework (MRCF) Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;83(3):451–457. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkin K., Madden M., Morris S., Gough B., McCambridge J. Community pharmacy and public health: preserving professionalism by extending the pharmacy gaze? Sociology of Health & Illness. 2021;43:336–352. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.13221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balint M. Pitman; London: 1957. The Doctor, his Patient and the Illness. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Britten N. Palgrave Macmillan; Basingstoke: 2008. Medicines and Society: Patients, Professionals and the Dominance of Pharmaceuticals. [Google Scholar]

- Cameron L., Leventhal H., editors. The self-regulation of health and illness behaviour. Routledge; London: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M., Fitzpatrick R., Haines A., Kinmonth A.L., Sandercock P., Spiegelhalter D., et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321(7262):694–696. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7262.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candy B., Vickerstaff V., Jones L., King M. Description of complex interventions: Analysis of changes in reporting in randomised trials since 2002. Trials [Electronic Resource] 2018;19(1):110. doi: 10.1186/s13063-018-2503-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng K.K.F., Metcalfe A. Qualitative methods and process evaluation in clinical trials context: Where to head to? International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2018;17(1) doi: 10.1177/1609406918774212. 1609406918774212. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CPPE . 2nd ed. 2012. New medicine service: Delivering quality and making a difference. An open learning programme for pharmacists and pharmacy technicians.https://www.cppe.ac.uk/learningdocuments/pdfs/newmedicineservice_ol%202012.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- CPPE . 2014. Consultation skills for pharmacy practice: Taking a patient-centred approach.https://www.cppe.ac.uk/programmes/l/consult-p-02 Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Davis K., Minckas N., Bond V., Clark C.J., Colbourn T., Drabble S.J.…Mannell J. Beyond interviews and focus groups: A framework for integrating innovative qualitative methods into randomised controlled trials of complex public health interventions. Trials [Electronic Resource] 2019;20(1):329. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3439-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhital R., Norman I., Whittlesea C., Murrells T., McCambridge J. The effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions delivered by community pharmacists: randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2015;110(10):1586–1594. doi: 10.1111/add.12994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwamena F., Holmes-Rovner M., Gaulden C.M., Jorgenson S., Sadigh G., Sikorskii A.…Olomu A. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;12:CD003267. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R.A., Boyd M.J., Salema N.E., Davies J., Barber N., Mehta R.L.…Craig C. Supporting adherence for people starting a new medication for a long-term condition through community pharmacies: A pragmatic randomised controlled trial of the new medicine service. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2016;25(10):747–758. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gale N.K., Heath G., Cameron E., Rashid S., Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2013;13 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. doi:Artn 11710.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaume J., McCambridge J., Bertholet N., Daeppen J.B. Mechanisms of action of brief alcohol interventions remain largely unknown - a narrative review. Frontiers in Psychiatry. 2014;5:108. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Pharmaceutical Council . General Pharmaceutical Council; London: 2017. Standards for pharmacy professionals.https://www.pharmacyregulation.org/sites/default/files/standards_for_pharmacy_professionals_may_2017.pdf Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- Glass J.E., Andreasson S., Bradley K.A., Finn S.W., Williams E.C., Bakshi A.S.…Saitz R. Rethinking alcohol interventions in health care: A thematic meeting of the international network on brief interventions for alcohol & other drugs (INEBRIA) Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2017;12(1):14. doi: 10.1186/s13722-017-0079-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill N., Anderson C., Avery A., Pilnick A. Analysis of pharmacist-patient communication using the Calgary-Cambridge guide. Patient Education and Counseling. 2011;83(3):423–431. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.04.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawe P., Shiell A., Riley T. Complex interventions: How “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? BMJ. 2004;328:1561. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7455.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne R., Chapman S.C., Parham R., Freemantle N., Forbes A., Cooper V. Understanding patients' adherence-related beliefs about medicines prescribed for long-term conditions: A meta-analytic review of the necessity-concerns framework. PloS One. 2013;8(12) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansen Y.J.F.M., de Bont A., et al. Tailoring intervention procedures to routine primary care practice; an ethnographic process evaluation. BMC Health Services Research. 2007;(7):125. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jee S., Grimes L., Desborough J., Cutts C. The national consultation skills for pharmacy practice program in England. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning. 2016;8(3):442–446. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2016.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kislov R., Pope C., Martin G.P., et al. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implementation Science. 2019;14:103. doi: 10.1186/s13012-019-0957-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin S., Glenton C., Oxman A.D. Use of qualitative methods alongside randomised controlled trials of complex healthcare interventions: Methodological study. BMJ. 2009;339:b3496. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M., Morris S., Atkin K., Gough B., McCambridge J. Patient perspectives on discussing alcohol as part of medicines review in community pharmacies. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2020;16(1) doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.03.145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M., Morris S., Ogden M., Lewis D., Stewart D., McCambridge J. Producing co-production: Reflections on the development of a complex intervention. Health Expectations. 2020 doi: 10.1111/hex.13046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M., Morris M., Ogden M., Lewis D., Stewart D., O'Carroll R.E., McCambridge J. Introducing alcohol as a drug in medicine reviews with pharmacists: Findings from a co-design workshop with patients. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2021 doi: 10.1111/dar.13255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden M., Morris S., Stewart D., Atkin K., Gough B., McCambridge J. Conceptualising alcohol consumption in relation to long-term health conditions: Exploring risk in interviewee accounts of drinking and taking medications. Plos One. 2019;14(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannell J., Davis K. Evaluating complex health interventions with randomized controlled trials: How do we improve the use of qualitative methods? Qualitative Health Research. 2019;29(5):623–631. doi: 10.1177/1049732319831032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May C.R., Mair F.S., Dowrick C.F., et al. Process evaluation for complex interventions in primary care: Understanding trials using the normalization process model. BMC Family Practice. 2007;8:42. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-8-42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J. Brief intervention content matters. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2013;32(4) doi: 10.1111/dar.12044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J. Reimagining brief interventions for alcohol: towards a paradigm fit for the twenty first century? Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00250-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., Atkin K., Dhital R., Foster B., Gough B., Madden M., Morris S., O'Carroll R.E., Ogden M., van Dongen A., White S., Whittlesea C., Stewart D. A programme of complex intervention developmental studies for pharmacists conducting person-centred medicine reviews which address alcohol. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice. 2021 doi: 10.1186/s13722-021-00271-5. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., Rollnick S. Should brief interventions in primary care address alcohol problems more strongly? Addiction. 2014;109(7) doi: 10.1111/add.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J., Saitz R. Rethinking brief interventions for alcohol in general practice. BMJ. 2017 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller W., Rollnick S. 3rd ed. Guilford Press; New York: 2012. Motivational Interviewing: Helping People Change. [Google Scholar]

- Mills T., Lawton R., Sheard L. Advancing complexity science in healthcare research: the logic of logic models. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2019 doi: 10.1186/s12874-019-0701-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G., Audrey S., Barker M., Bonell C., Hardeman W., Moore L.…Baird J. 2014. Process evaluation of complex interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance.https://mrc.ukri.org/documents/pdf/mrc-phsrn-process-evaluation-guidance-final/ Retrieved from London. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G.F., Audrey S., Barker M., Bond L., Bonell C., Hardeman W.…Baird J. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2015;350:h1258. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h1258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore G.F., Evans R., Hawkins J., Littlecott H., Melendez-Torres G.J., Bonell C., et al. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: Future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation. 2018;25(1):23–45. doi: 10.1177/1356389018803219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty H.J., Stubbe M.H., Chen L., Tester R.M., Macdonald L.M., Dowell A.C., et al. Challenges to alcohol and other drug discussions in the general practice consultation. Family Practice. 2011;29(2):213–222. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmr082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris S., Madden M., Gough B., et al. Missing in action: insights from an exploratory ethnographic observation study of alcohol in everyday UK community pharmacy pratice. Drug and Alcohol Review. 2019 doi: 10.1111/dar.12960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NICE guideline 5 . 2015. Medicines optimisation: The safe and effective use of medicines to enable the best possible outcomes.https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng5 Retrieved from. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuwlaat R., Wilczynski N., Navarro T., Hobson N., Jeffery R., Keepanasseril A.…Haynes R.B. Interventions for enhancing medication adherence. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014;11 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000011.pub4. (Review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pound P., Britten N., Morgan M., Yardley L., Pope C., Daker-White G., et al. Resisting medicines: A synthesis of qualitative studies of medicine taking. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;61(1):133–155. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.11.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PSNC . 2020. MUR record keeping and data requirements.https://psnc.org.uk/mur-record-keeping-and-data-requirements/ Retrieved from. [Google Scholar]

- PSNC and NHS Employers . Retrieved from; London: 2012. Guidance on the medicine use review service. [Google Scholar]

- Quirk A., Chaplin R., Hamilton S., Lelliott P., Seale C. Communication about adherence to long-term antipsychotic prescribing: An observational study of psychiatric practice. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48(4):639–647. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0581-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley T., May C., Kaner E. Still a difficult business? Negotiating alcohol-related problems in general practice consultations. Social Science & Medicine. 2006;63(9):2418–2428. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapport F., Storey M., Porter A., Snooks H., Jones K., Peconi J.…Russell I. Qualitative research within trials: Developing a standard operating procedure for a clinical trials unit. Trials [Electronic Resource] 2013;14(1):54. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., McCambridge J. Alcohol complicates multimorbidity in older adults. BMJ. 2019;365 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l4304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., Whittlesea C., Dhital R., Newbould L., McCambridge J. Community pharmacist led medication reviews in the UK: A scoping review of the medicines use review and the new medicine service literatures. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2019.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., van Dongen A., Watson M., Mandefield L., Atkin K., Watson M., Dhital R., Foster B., Gough B., Hewitt C., Madden M., Morris S., O'Carroll R.E., Ogden M., Madden M., Parrott S., Watson J., White S., Whittlesea C., McCambridge J. A pilot cluster randomised trial of the medicines and alcohol consultation (MAC): an intervention to discuss alcohol use in community pharmacy medicine review services. BMC Health Services Research. 2020 doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05797-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart D., Madden M., van Dongen A., Madden M., Whittlesea C., Whittlesea C. Process study within a pilot cluster randomised trial in community pharmacy: An exploration of pharmacist readiness for research. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2021.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.