Abstract

This cohort study examines whether trends exist in the number of benzodiazepines and opioids prescribed to adolescents and young adults between 2008 and 2019.

Benzodiazepines are commonly prescribed to pediatric patients despite a narrow range of approved indications.1 Like opioids, benzodiazepines are subject to prescription drug misuse and have been associated with increased risk of opioid overdose and opioid-related mortality in adolescents and young adults.2,3,4 Because limited information is available on the use of benzodiazepines in these age groups, we examined trends in benzodiazepine prescriptions dispensed during a 12-year period, including potential treatment indications and concurrent use with opioids.

Methods

In this cohort study, we analyzed health care claims from a nationwide commercial health insurance plan covering 9 338 501 adolescents (aged 13-18 years) and young adults (aged 19-25 years) with both medical and prescription drug coverage between January 1, 2008, and December 31, 2019. Data on race and ethnicity were not collected as part of the database. Mean (SD) insurance enrollment length was 20.4 (21.6) months. Pharmacy claims were reviewed to identify patients who were dispensed benzodiazepines or opioids (eMethods in the Supplement). Diagnosis codes for all health care encounters during the 90 days before the benzodiazepine dispensing date were reviewed to identify US Food and Drug Administration–approved indications (eMethods in the Supplement). Concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid use was defined as a dispensing overlap of 1 or more days. Dispensing prevalence was defined as the number of adolescents and young adults per 1000 enrollees each month who were dispensed benzodiazepines. Monthly mean prevalence and 95% CI each year were used to assess dispensing trends. Concurrent use of benzodiazepine with an opioid was ascertained using monthly mean prevalence per 1000 enrollees who were dispensed benzodiazepines. The study was deemed exempt from human subjects review and informed consent was waived by the institutional review board at Boston Children’s Hospital because only deidentified data were used. The study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. Linear models were used to examine changes per year. R software, version 4.1.0 (R Foundation) was used to analyze the data. The threshold for statistical significance was P < .05.

Results

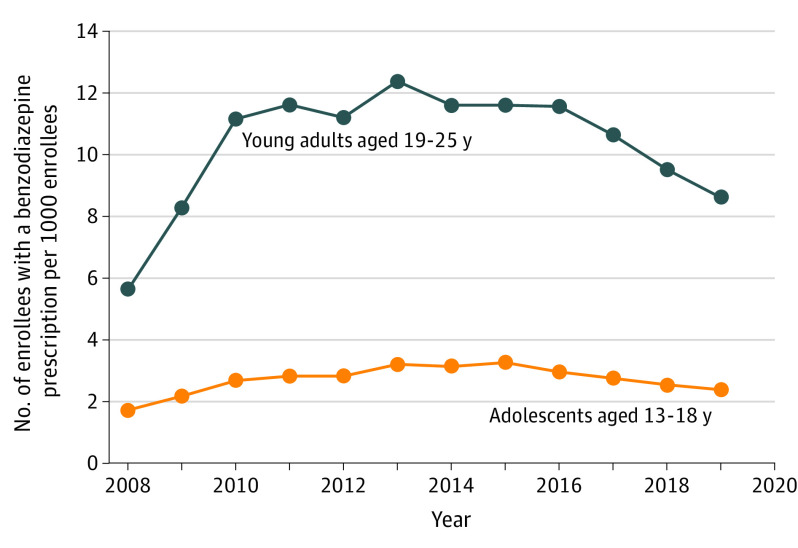

At least 1 benzodiazepine was dispensed to 74 539 of 4 195 455 adolescents (1.8%) and 246 760 of 6 146 070 young adults (4.0%). Diazepam (35.9%, n = 26 752) and alprazolam (39.6%, n = 97 654) were the most frequently dispensed benzodiazepines to adolescents and young adults, respectively. Dispensing prevalence per 1000 enrollees peaked in 2015 at 3.27 (95% CI, 3.05-3.49) benzodiazepine prescriptions for adolescents and in 2013 at 12.38 (95% CI, 12.03-12.72) prescriptions for young adults (Figure 1). Subsequently, prevalence decreased each year by 0.17 (95% CI, 0.10-0.24) and 0.62 (95% CI, 0.53-0.70) benzodiazepine prescriptions per 1000 enrollees among adolescents and young adults, respectively. Approved indications were identified for 18 291 adolescents (24.5%) and 83 071 young adults (33.7%).

Figure 1. Monthly Benzodiazepine Dispensing Prevalence Among Adolescents and Young Adults.

Data points represent mean monthly prevalence in a given year.

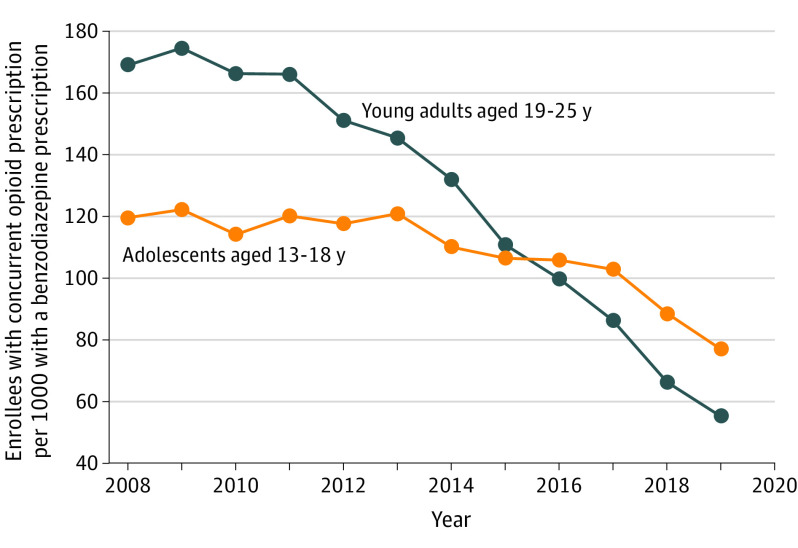

A concurrent opioid prescription was dispensed to 19 476 adolescents (26.1%) and 59 104 young adults (24.0%) with a benzodiazepine prescription. Concurrent dispensing prevalence peaked in 2009 at 122.03 (95% CI, 107.28-136.77) prescriptions per 1000 adolescents and 174.35 (95% CI, 171.31-177.39) prescriptions per 1000 young adults (Figure 2). The subsequent yearly decrease in concurrent dispensing prevalence was more than twice as large among young adults (12.83; 95% CI, 12.26-13.40 prescriptions per 1000 enrollees per year) compared with adolescents (5.57; 95% CI, 2.81-8.32 prescriptions per 1000 enrollees per year). For adolescents, prevalence of concomitant benzodiazepine and opioid prescribing was 77.48 (95% CI, 63.39-91.57) prescriptions per 1000 adolescents in 2019.

Figure 2. Monthly Dispensing of Concurrent Opioid Prescriptions Among Adolescents and Young Adults.

Data points represent mean monthly prevalence in a given year.

Discussion

The prevalence of dispensed benzodiazepines has been steadily decreasing for adolescents and young adults in a large commercially insured population since 2015 and 2013, respectively. Prevalence of concurrent benzodiazepine and opioid prescriptions has also decreased. These findings are consistent with reports showing declining use of benzodiazepines and opioids among adults.5,6 We analyzed data from a single insurance provider, which may limit the generalizability of our findings to other patient populations, such as those covered by government insurance plans.

Despite recent decreases in the prevalence of dispensed benzodiazepines, dispensing prevalence remained higher in 2019 than in 2008 in both age groups, and, in 2019, 8% of adolescents with a dispensed benzodiazepine prescription also filled an opioid prescription. Furthermore, among adolescents, only approximately one-quarter had a diagnosis corresponding with an approved indication, raising concern for frequent use of benzodiazepines for indications with limited clinical evidence of efficacy. Given the known risks associated with benzodiazepine use, additional efforts are needed to ensure judicious and evidence-based prescribing of benzodiazepines in adolescents and young adults.

eMethods.

References

- 1.Bushnell GA, Crystal S, Olfson M. Prescription benzodiazepine use in privately insured U.S. children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2019;57(6):775-785. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2019.07.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palamar JJ, Le A, Mateu-Gelabert P. Not just heroin: extensive polysubstance use among US high school seniors who currently use heroin. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018;188(April):377-384. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Conti RM, Bohnert A. Association of opioid prescribing patterns with prescription opioid overdose in adolescents and young adults. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(2):141-148. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.4878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim JK, Earlywine JJ, Bagley SM, Marshall BDL, Hadland SE. Polysubstance involvement in opioid overdose deaths in adolescents and young adults, 1999–2018. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(2):194-196. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bykov K, He M, Gagne JJ. Trends in utilization of prescribed controlled substances in US commercially insured adults, 2004–2019. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1006-1008. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Guy GP Jr, Zhang K, Bohm MK, et al. Vital signs: changes in opioid prescribing in the United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;66(26):697-704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6626a4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods.