Abstract

Background:

Hospital-based acute care (emergency department [ED] visits and hospitalizations) that is preventable with high-quality outpatient care contributes to healthcare system waste and patient harm.

Objective:

To test the hypothesis that an ED-to-home transitional care intervention reduces hospital-based acute care in chronically ill, older ED visitors.

Research Design:

Convergent, parallel, mixed-methods design including a randomized controlled trial

Setting:

Two diverse Florida EDs.

Subjects:

Medicare fee for service beneficiaries with chronic illness presenting to the ED.

Intervention:

The Coleman Care Transition Intervention® adapted for ED visitors

Measures:

The main outcome was hospital-based acute care within 60 days of index ED visit. We also assessed office-based outpatient visits during the same period.

Results:

The Intervention did not significantly reduce return ED visits or hospitalizations or increase outpatient visits. In those with return ED visits, the Intervention Group was less likely to be hospitalized than the Usual Care Group. Interview themes describe a cycle of hospital-based acute care largely outside patients’ control that may be difficult to interrupt with a coaching intervention.

Conclusions and Relevance:

Structural features of the healthcare system, including lack of access to timely outpatient care, funnel patients into the ED and hospital admission. Reducing hospital-based acute care requires increased focus on the healthcare system rather than patients’ care-seeking decisions.

Trial Registration:

INTRODUCTION

Improving the care transitions that occur as patients move between healthcare settings and providers is a national priority, yet major evidence gaps exist on how to optimize these transitions for growing numbers of older Americans with chronic health conditions.1–3 One costly effect of this evidence gap is a high rate of hospital readmissions in Medicare beneficiaries.4 In 2012, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) implemented the Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program to curb these readmissions.5 In response to financial penalties for excessive readmission rates, additional CMS incentives to reduce unnecessary hospitalizations, and in an attempt to improve overall care transitions, interest grew in hospital-to-home transition interventions. At the time, few investigations focused on transitions into or out of the emergency department (ED).

Americans make 140+ million visits to hospital EDs each year.6 The ED is the safety net for vulnerable populations, including older adults with chronic illness. ED visits are often critical inflection points in a patient’s health trajectory with long-term consequences on survival and quality of life.1,7–13 More than 80 percent of unscheduled hospital admissions and 50 percent of readmissions originate in the ED.14 Often, ED admission decisions are based on emergency providers’ perceptions of patients’ social circumstances and access to timely outpatient care.15–17 Unfortunately, the rapid throughput that characterizes EDs leaves little time for providers to ensure patients have access to adequate support once they leave the ED. Despite their central role in the healthcare system and the patient’s health trajectory, little is known about how to improve the quality of ED transitions.1 We do know that poorly managed ED transitions can lead to additional and costly hospital-based acute care (ED return visits and hospitalizations) and patient harm.1,7–13 Older patients are at especially high risk of poor outcomes if they experience gaps in support when transitioning between ED and home.10,11

Few studies on ED-to-home transitions have been conducted, and the majority of published reports lack robust research designs.11,18 We sought to evaluate the impact of an ED-to-home transitional care coaching program on hospital-based acute care in older adults with chronic health conditions. We designed the project to address many of the concerns with existing hospital-to-home transition studies.19,20 Notably, our intervention included a rigorous, randomized, controlled trial (RCT) design and was based on the multifaceted and evidence-based Coleman Care Transitions Intervention®.21 We also based the trial on conceptual frameworks that provide an understanding of why individuals use hospital-based acute care for conditions that can be more effectively and efficiently managed in primary care settings.8,14–16,19,21–28 Patients may use hospital-based acute care due to their perceptions of symptom severity; anxiety about their condition; and advice of family, friends, or health professionals within the context of social and medical complexity and systemic barriers to primary care.8,22,23,28 Addressing these core factors, including helping individuals connect with outpatient care and support, and providing patients and families with tools to manage their health and symptoms, has the potential to reduce hospital-based acute care.21,29

Our study objective was to test the hypothesis that an ED-to-home transitional care intervention reduces hospital-based acute care in chronically ill, older ED visitors. Another objective was to examine these quantitative study outcomes in the context of qualitative patient and provider interviews.

METHODS

Study Design:

Investigators, five patient stakeholders, and Area Agency on Aging staff designed a convergent, parallel, mixed-methods study, including an RCT. We partnered with patient stakeholders (chronically ill older adults with frequent ED visits) and Area Agency on Aging staff to ensure the trial reflected patients’ input, wants, needs and preferences. Quantitative (health service outcomes) and qualitative (in-depth interviews) data collection occurred simultaneously. This mixed-methods design allows collection of comprehensive, rich data, and an interactive approach whereby quantitative results might influence further qualitative data collection.30 This research design ensures conclusions are grounded in patients’ experiences.30 Investigators and stakeholders analyzed data sets independently and used qualitative results to provide context for quantitative findings.30

Study Setting:

Two ED, tertiary referral centers in Florida. One ED (99,000 visits/year) serves a community of 250,000, a university, and 14 rural counties. The second (110,000 visits/year) ED serves a large urban community. The recruitment period was May 2014 through November 2015.

Participants:

The study population was comprised of chronically ill ED visitors scheduled for ED discharge, hospital observation status, or with frequent ED visits (≥ 3 visits/in prior year).8,22 Study eligibility required continuous Medicare Parts A and B coverage for 12 months before the index ED visit and a minimum of 30 days following the index visit. Analyses assessing utilization 60 days post-ED discharge required continuous coverage over 60 days. Study participants were required to reside within specific ZIP codes to enable home visits, have a working phone, ≥ 1 chronic medical condition reported in the electronic health record, and no critical or life-threatening conditions documented at ED triage. Patients with active psychosis, undergoing cancer treatment, with dementia but without a live-in caregiver, receiving hospice care, or living in a skilled nursing facility at ED presentation were excluded.

The biostatistician generated the randomization sequence before study initiation. Trained research associates (RAs) screened the ED electronic health record and obtained informed consent while the patient was in the ED. RAs and patients were blinded to study assignment until completion of a baseline survey.

We used purposeful sampling to recruit patient participants for in-depth interviews based on age, gender, site, race/ethnicity, study assignment, and comorbid illness consistent with the overall study population.22 Patient participants were remunerated $50.00 for a 90-minute, in-home interview. We also interviewed primary care and ED physicians and coaches from each site. All in-depth interviews were designed to capture factors that influenced patients’ acute healthcare-seeking decisions (Appendix 1). Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and uploaded into NVIVO v1131 for thematic analysis.32 We used dimensional and comparative analysis to identify codes, themes, and conclusions.33,34 Details of qualitative data and methods are described elsewhere.22

Data Sources:

A baseline survey captured patient sociodemographic factors. We captured health service use (ED visits, hospital admissions, office-based visits) through Medicare claims.8,22 Office-based outpatient visits included Medicare Part B claims with Evaluation and Management codes for new patient, office visits (CPT 99201–99205); established patient office visits (CPT 99211–99245); or consultations (office or outpatient, CPT 99241–99245). We excluded outpatient visits associated with ED or observation stays based on revenue center codes.35,36

Intervention and Usual Care Groups:

Intervention:

Coleman’s evidence-based Care Transitions Intervention® focuses on four ‘pillars’ associated with adverse patient outcomes including unplanned hospital readmission: (1) lack of timely follow-up doctor visits; (2) poor understanding of disease warning signs; (3) medication reconciliation issues; and (4) lack of a personal health record.21 The model addresses each pillar through a 30-day program utilizing coaches to conduct a hospital visit prior to discharge, a home visit, and three follow-up phone calls after hospital discharge.21 The coach helps patients develop disease self-management capabilities and communicate with providers.21,37,38 The program works with patients of all literacy levels through one-on-one review of each pillar during multiple sessions and assessment of patients’ understanding.21,37,38

Patient stakeholders indicated the Care Transition Intervention® could help patients like themselves recover from a health crisis associated with an ED visit and prevent future hospital-based acute care. Therefore, we adapted the Care Transition Intervention® for the ED-to-home Intervention. Patient stakeholders and community partners also indicated that home-delivered meals and transportation to a doctor’s office could assist an older patient avoid return ED visits.

If possible, trained Area Agency on Aging Coaches visited patient participants in the ED or called them within 24 hours of ED discharge to introduce themselves, answer program questions, and schedule a home visit. Coaches made at least three attempts to schedule the home visit.

One author (AGH) shadowed each project coach on select home visits to confirm intervention fidelity. AGH documented the following coaching components: (1) Follow-up doctor visits: Coaches emphasized the need for patients to make and attend follow-up appointments and formulate questions for their provider; (2) Knowledge of disease warning signs: Coaches ensured patients understood their health conditions and what to do if conditions worsened; (3) Medication reconciliation: Coaches encouraged patients to review all medications and demonstrate their use. Coaches helped patients complete a comprehensive medication review and ensured patients had a system for safely managing medications. Coaches helped patients reconcile medication discrepancies with their primary doctor or pharmacist; (4) Personal health record: Each patient and/or caregiver wrote in the personal health record to document the patient’s history, care plan, medications, questions for providers, and self-defined goals. Coaches helped patients use the personal health record to maintain vital information and communicate with providers.

During the home visit, coaches discussed additional services such as transportation to physician appointments, home-delivered meals, and small equipment for monitoring health (e.g., blood pressure monitors).

During the 30-day period following the home visit, coaches called patients during weeks 1, 2, and 4. During each contact (approximately 60 minutes), coaches reviewed the patient’s progress on each pillar and any active coaching concerns. Additional calls or visits were made based on patient progress.

Coach Background and Training:

Area Agency on Aging Coaches required a bachelor’s degree (B.A./B.S.) from a four-year college or university, successful completion of the Coleman Care Transition Intervention®, and Community Health Worker Certification. One study coach was a Licensed Practical Nurse and the second coach had a social work degree.

Usual, Post-ED Care:

ED discharge practice for managing older adults with chronic illness throughout the study period was to provide written and verbal discharge instructions, including advice to follow up with a personal doctor.39,40

Outcome Measures:

Patient-level analysis:

To capture the full impact of the 30-day intervention, the main outcome was hospital-based acute care (any return ED visit; any hospitalization) within 60 days of index ED visit. We assessed office-based outpatient visits within 30 and 60 days of index ED visit because early provider follow-up was a key component of the coaching intervention.

Visit-level analysis:

Unscheduled ED returns are often used as ED quality measures because they may indicate inadequate care at the index ED visit or inadequate access to post-discharge care.9 A secondary outcome was the Intervention’s impact on hospitalization in ED return visits within 60 days of the index visit. Discharge disposition was dichotomized (admission versus observation stay, home, or transfer) as previously reported.17,41

Sample Size and Power:

In this study, 300 participants in each group were needed to detect a 30 percent reduction in ED returns21 (80% power, α=0.05). We enrolled 1322 patients to account for potential loss to follow-up in a telephone survey component of this study that assessed Intervention effect on quality of life.8

Analytic Approach:

Quantitative:

At the patient level, we assessed baseline between-group differences in sociodemographic and health factors with t-tests for continuous and chi-square tests for categorical measures. We used logistic regression to assess the relationship between study assignment and dichotomous outcomes (any return ED visit, any hospitalization, outpatient visit). At the visit level, we assessed the relationship between study assignment and discharge disposition for ED return visits using logistic regression with clustered standard errors to account for patients with multiple ED visits.

Although an RCT trial design, we assessed differences in sociodemographic and health factors that may have arisen by chance. We initially estimated unadjusted models, then adjusted for site (to account for possible differences in implementation by site) and any factor that differed at the p < 0.2 level in the 12 months before enrollment to ensure robust findings.42

Analyses followed an intention-to-treat approach, and significance was set at p < 0.05. Quantitative analyses used SAS v9.443 and Stata v13 software.44

Qualitative:

A multidisciplinary team coded transcripts line-by-line using open, then focused coding22, using NVivo v11.0 for dimensional and comparative analysis.32–34 To explain and expand quantitative results, we examined interviewee perspectives on hospital-based acute care.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics:

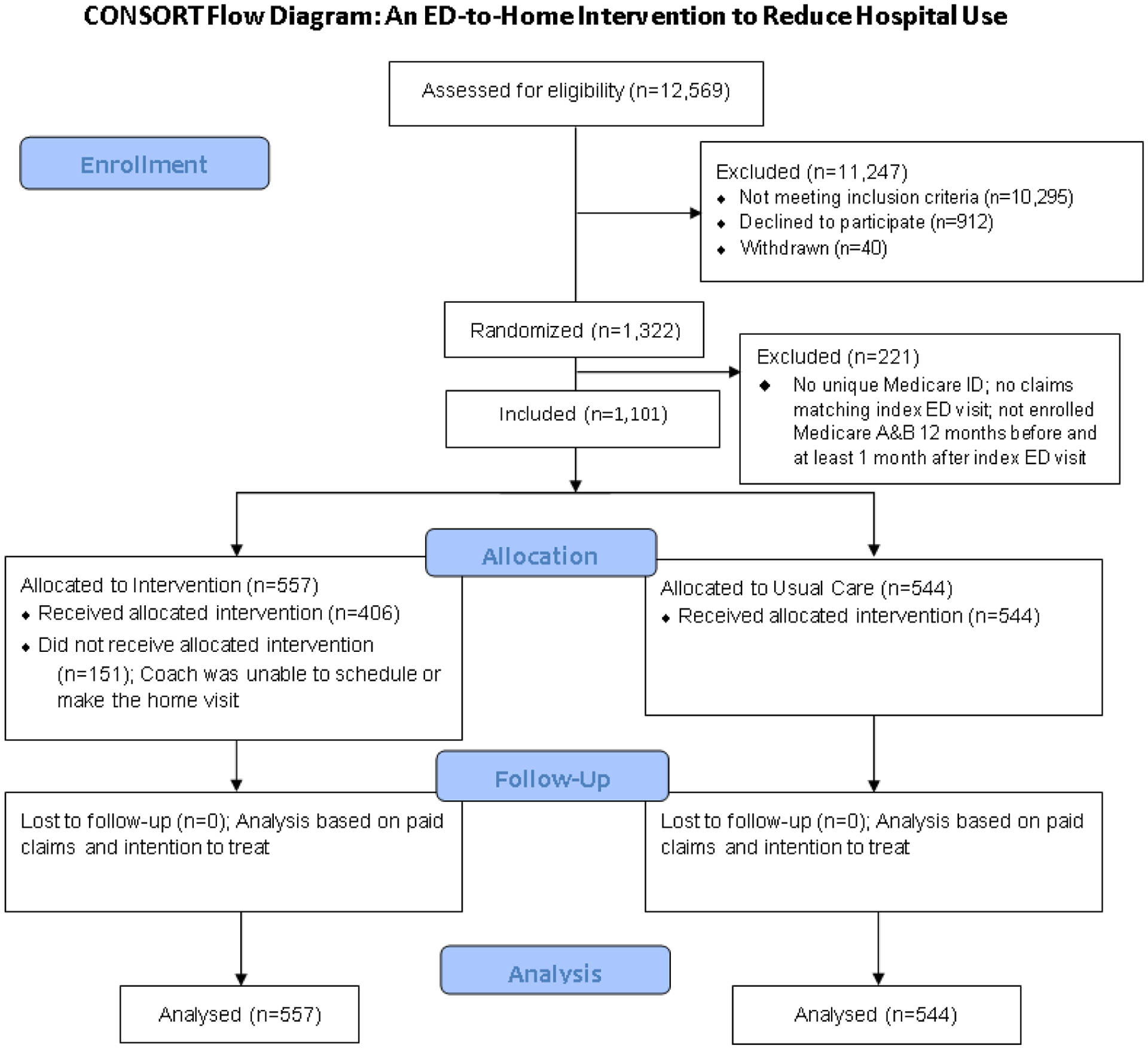

Of 1,322 randomized patients, 221 were excluded (Figure 1).8 Medicare claims were available for 87.7 percent of participants. Of 1,101 enrolled patients, we randomized 557 to Intervention and 544 to Usual Care. Coaches were unable to schedule or attend the post-ED home visit in 151 Intervention participants (Figure 1). The home visit usually took place within 24–72 hours of ED discharge, based on patient preference. Thirty-six Intervention participants received transportation assistance, and 108 received home-delivered meals. In all, 1101 participants had 30-day and 1004 participants had 60-day post index ED visit Medicare claims available for analysis.

Figure:

Patient flow and procedures assessing health service use

Forty patient participants (20 from each site: 27 Intervention, and 13 Usual Care) were interviewed,22 along with four ED physicians (two from each site), six primary care physicians (three from each site), and the two study coaches.

Table 1 outlines patient characteristics. The average participant age was 72.6 years; 50 percent were nonwhite; 24 percent were disabled; and 43 percent were eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid. There were no statistically significant between-group differences at p < .05. Between-group differences in health factors at the p < .2 level included hypertension, renal failure, and congestive heart failure (CHF) (Table 1).

Table 1:

Sociodemographic and Health Factors for patients in Intervention and Usual Care Group (n=1,101)

| Patient Factor | Overall | Usual Care | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | p-value | |

| Mean Age (SD) | 72.6 (8.5) | 72.8 (8.6) | 72.4 (8.4) | 0.47 |

| Female | 62 | 63 | 60 | 0.26 |

| Race | 0.69 | |||

| Nonwhite | 50 | 49 | 50 | |

| White | 50 | 51 | 50 | |

| Marital Status | 0.39 | |||

| Single/Never Married | 12 | 13 | 10 | |

| Separated Divorced | 26 | 26 | 26 | |

| Married | 32 | 32 | 33 | |

| Divorced | 30 | 29 | 31 | |

| Employment Status | 0.86 | |||

| Unemployed | 6 | 7 | 5 | |

| Employed | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Retired | 67 | 67 | 68 | |

| Disabled | 24 | 23 | 24 | |

| Medicaid | 43 | 42 | 44 | 0.53 |

| Chronic Conditions** | ||||

| CHF | 20 | 18 | 21 | 0.19 |

| Valvular Disease | 7 | 8 | 6 | 0.42 |

| Peripheral Vascular Disease | 12 | 12 | 12 | 0.97 |

| Other Neurological Disorders | 12 | 12 | 11 | 0.67 |

| COPD | 29 | 28 | 29 | 0.73 |

| Diabetes (w/o complications) | 33 | 32 | 34 | 0.54 |

| Diabetes (with complications) | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0.87 |

| Hypothyroidism | 17 | 17 | 18 | 0.77 |

| Renal Failure | 23 | 21 | 25 | 0.06 |

| Liver Disease | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0.85 |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 5 | 6 | 4 | 0.29 |

| Obesity | 17 | 16 | 18 | 0.59 |

| Weight Loss | 6 | 6 | 6 | 0.98 |

| Fluid & Electrolyte Disorders | 26 | 25 | 26 | 0.70 |

| Deficiency Anemias | 26 | 27 | 24 | 0.23 |

| Hypertension | 74 | 72 | 76 | 0.14 |

| Depression | 15 | 16 | 15 | 0.62 |

Conditions limited to those with prevalence minimum of 5% in overall sample

COPD indicates Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Quantitative Results:

In unadjusted analysis, there was no statistically significant association between study assignment and odds of hospital-based acute care (any return ED visit (OR = 1.08; 95% CI = 0.83–1.39); any hospital admission (OR = 1.03; 95% CI = 0.76–1.39), or outpatient visit (OR = 1.13; 95% CI = 0.77–1.67) within 60 days of index ED visit (Table 2). Findings were unchanged after adjustment. There were no between-group differences in outpatient visits based on when the visit took place or provider type (Appendix 2).

Table 2:

Health Service Use-Quantitative Outcomes*

| Health Service Use | N | Unadjusted Intervention Effect OR (95% CI) |

Adjusted Intervention Effect** OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Level Analysis | |||

| Return ED Visits | 1,004 patients | No Significant Association OR = 1.08 (0.83–1.39) |

No Significant Association OR = 1.03 (0.79–1.34) |

| Hospital Admissions | 1,004 patients | No Significant Association OR = 1.03 (0.76–1.39) |

No Significant Association OR = 0.96 (0.70–1.30) |

|

Outpatient Visits

30 Days 60 Days |

1,101 patients 1,004 patients |

No Significant Association OR = 1.29 (0.97–1.71) OR = 1.13 (0.77–1.67) |

No Significant Association OR = 1.27 (0.96–1.69) OR = 1.14 (0.77–1.69) |

| Visit Level Analysis | |||

| Hospital Admission Upon Return ED Visit | 627 return ED visits | Reduced admission upon ED return OR = 0.64 (0.45–0.91) | Reduced admission upon ED return OR = 0.61 (0.43–0.86) |

Return ED Visits and Hospital Admissions within 60 days; Outpatient visits within 30 and 60 days

Adjusted for site, hypertension, renal failure, and congestive heart failure

CI indicates confidence interval; ED indicates emergency department; OR indicates odds ratio

Six hundred twenty-seven return ED visits were made by 358 patients within 60 days of index ED visit. In unadjusted analysis, Intervention participants had 36 percent lower odds of hospitalization upon ED return (OR = 0.64; 95% CI = 0.45–0.91) compared with Usual Care participants (Table 2). This finding was unchanged after adjustment (39% lower odds; OR = 0.61; 95% CI = 0.43–0.86).

Qualitative Results:

Regardless of study assignment, similar themes emerged from patient, physician, and coach interviews across study sites (Tables 3, 4).

Table 3:

Health Service Use-Qualitative Outcomes: Interview Themes from the Patient’s Perspective

| Health Service Use | Interview Themes | Patient Perspective |

|---|---|---|

| Return ED Visits | Patients confident they will get needed care in the ED | When he went in through the back in the ambulance, they gave him quick service. They immediately got the doctor in there to get him a CT scan done. (2–172) I told that doctor [in the ED]. I said, “Something’s wrong, something’s happening.” He said, “Your blood pressure’s gotten too low. We’ll get it back up.” And I’m thinking, “Dadgum, what if that would’ve happened at home?” You know, the blood pressure drop like that… So that’s why I’d go to the hospital instead. I mean, but if I got a cold, like if this cold don’t get no better, I’ll probably go to [primary care doctor.] (2–50) They do a chest x-ray, take blood work. Then the doctor comes in. If they want an X-ray, they’ll take an x-ray. (1–053) |

| Provider recommends patient go to the ED | Actually I believe if I did get him [the primary care doctor] on the phone, they’re going to say, “Well, how bad is it?” I’m going to tell him. Give him a number, between zero and ten, how bad is it, and they’re eventually going to come up with, “Well, you need to go to emergency.” (1S-06) Actually, we went to him before we went to the emergency room. We saw him, and he said, “Go on to the emergency room.” (1S-086) |

|

| Outpatient Visits | Barriers to Outpatient Care Difficulty getting an outpatient appointment | Most of the time before if she [primary care provider] wasn’t available I’d see the other doctors there I like. Well, she said she didn’t want that. I am to call and tell them to check with her to overbook her so she can see me. Now, like this week she’s off. (1–321) It was at night, and then, plus, a primary care doctor, I’d have to make an appointment, and it take, like, two weeks. (1S-162) |

| Hospital Admission Upon ED Return Visit | Role of coach in supporting patient after ED discharge | I feel like it’s good to have somebody [e.g. a coach] some things that the doctor says, you don’t understand, because they talk in doctor terms. Sometimes, they write out a prescription, you don’t understand what the prescription is. (2S-13) The fact that someone cared enough to come follow-up after a few days, after the dust had settled to see how I felt, to see whether I’m having any further problems with it, and what more did we need to do. And that was the question from her, “What more do we need to do?” I found that gratifying and comforting, very comforting. (1–314) |

CT indicates computed tomography; ED indicates emergency department

Table 4:

Health Service Use-Qualitative Outcomes: Interview Themes from Physician’s and Coach’s Perspectives

| Health Service Use | Interview Themes | Physician Perspective | Coach Perspective |

|---|---|---|---|

| Return ED Visits | Patients confident they will get needed care in the ED | Well, in this community, I think they [the patients] see the ER, too, like a primary care office. So it’s hard to teach them that it’s not, but I’m [in a different location], so the ER is there… They’re just going to go ahead and go to the emergency room. (2–3PCP) | Coach speaking from patient’s perspective: First and foremost somebody’s going to pay attention to me right away, give me a diagnosis to what’s going on. I have staff around me. (1-C) |

| Provider recommends patient go to the ED | Many times their own doctor says go to the emergency department. If they are calling their doctor with chest pain, the reflexive answer has become go to the ER…less and less take care of emergent and acute conditions in their offices as opposed to maybe 10, 15, 25 years ago. (1–5ED) And so basically what I do is I look at the numbers and see what we can accommodate, and also depending on what the message is. If they’re having something that sounds unstable then they’re sent to the emergency room or advised to call 911. If it’s something that sounds like —we should take a look at it first, then we try to accommodate them. (2–2PCP) Do they need to come in right now? Or do they need to go to the emergency room? I would say it’s unusual that from when we (PCPs) get the message that we say go to the emergency room. But I will say that the call center is probably part of their protocol. I don’t know that it’s their protocol but I see the message frequently is the patient was advised if they feel it’s an emergency to go to the emergency room. (2–2PCP) |

If something comes up you’re going to call your doctor. A lot of times a doctor is called. There is a triage person there. The information is given to the physician and its’ go to the ER. (1-C) | |

| Hospital Admissions | ED physician decision to admit based on patient ability to get follow-up care | I would say 40 to 50 % fall into that vague area, where it’s a judgement call and you have to take into account that you have some patients could theoretically be discharged, but if I discharge them, what’s going to happen to them at home? Are they going to get the medicines?” (2–5ED) It could take four hours for our patients to get here because of the bus routes. So we actually had to admit some patients because they couldn’t come back for follow-up and take a four-hour bus trip each way. That just wasn’t going to work if they’re—sick. (2–4ED) |

|

| Outpatient Visits | Barriers to Care: Difficulty getting an outpatient appointment; inability to perform diagnostic testing | We can’t even do a chem stick in our office. We don’t do any point of care testing at this time. We don’t do EKGs, we don’t provide treatments at the clinic. So we are primarily a coordination of care clinic. (1–3PCP) So some of these patients, they’re trying to get into their PCP and they’re going in at 5:00 in the morning and they’re waiting in line, and they’re not getting seen till 5:00 in the afternoon…So for me personally, I wouldn’t have that patience. Why do that as opposed to go sit in the ED? So I think a lot of the patients actually have a delay in care, as far as primary care. (2–5ED) When they feel like they need to go to see you and you don’t have an opening, they just go to the ER instead of coming to the office. (2–3PCP) |

Or the big one is scheduling. They don’t have an opening at that time. So, if that’s the case then go to the emergency room. (1-C) I think a lot of it is there are too few doctors I think for the amount of people that need to see—that were on Medicare in [city]…They don’t want to take those kinds of patients. (2-C) |

| Hospital Admission Upon ED Return Visit | Role of coach in supporting patient after ED discharge | I think it would be a lot easier for me to discharge patients, and not be so concerned about their safety, knowing that there’s somebody else that was going to ensure that they are safe. (1–4ED] | I think yes, we need to know that you know how to take your medication because you’d be surprised {sometimes the patients] don’t have a clue. (2-C). |

ED indicates emergency department; PCP indicates primary care provider; C indicates coach

ED Return Visits:

Two themes helped explain why the Intervention did not affect ED return visits. First, patients were confident they would get needed care in the ED (Table 3), and second, primary providers often encouraged patients to seek emergency care (Table 4). Patients and coaches indicated patients visited the ED because they felt their health concerns were more thoroughly addressed in this setting (Tables 3, 4). Patients, physicians, and coaches indicated that primary care providers often encouraged patients to seek ED care for complex problems or symptoms (Tables 3, 4).

Hospital Admissions:

Physician interviews helped shed light on why there were no between-group differences in hospitalizations except in the subgroup of patients with return ED visits. ED physicians stated they often hospitalize patients if outpatient follow-up or social support are in question but also feel more comfortable discharging patients if a professional checks on the patient following ED discharge (Table 4).

Outpatient Visits:

Outpatient visits were similar in Intervention and Usual Care groups. Patients, physicians, and coaches described barriers to timely outpatient care that clarified this finding. Patients, physicians, and coaches reported that it was difficult to schedule outpatient visits in a timeframe patients felt visits were needed. Physicians and coaches reported that office-based outpatient visits were discouraged altogether if a patient’s complexity required diagnostic tests unavailable in ambulatory settings (Table 4).

Discussion

We conducted an adequately powered RCT to test the hypothesis that an ED-to-home intervention reduces hospital-based acute care in older adults presenting to the ED. The ED-to-home Intervention did not significantly affect hospital-based acute care compared with usual post-ED care. However, ED return visits made by coached patients were less likely to result in hospitalization compared with ED returns made by Usual Care participants. Consistent themes emerged from patient, physician, and coach interviews, regardless of study assignment or study site. The qualitative results support and provide details that expand quantitative findings. Our rigorous, mixed-methods trial design suggests the findings are not an artifact but rather reflect the reality older adults face managing chronic illness in the current healthcare environment.

Systematic reviews suggest that multifaceted programs and those that encourage patient empowerment are the most successful hospital-to-home interventions.19–21 Helping patients build self-management capabilities is a central feature of the Care Transition Intervention,®21,27,37,38 and direct observation of coaches in the current study confirmed that coaches helped patients take charge of their follow-up appointments, questions, medications, and healthcare goals. In a pilot study, we directly measured patient engagement using the Patient Activation Measure® with the ED-to-home Intervention and noted that our intervention positively affected patient engagement.29 Despite evidence that the ED-to-home Intervention affects patient empowerment, we detected no between-group differences in overall hospital-based acute care in the current trial.

Qualitative results help explain these findings. Patients described difficulty seeing their primary provider and care-seeking decisions that were often informed by providers’ advice.22 Primary care physicians indicated they have limited capacity to address acute complaints by complex patients in the office and often referred such patients to the ED. ED physicians suggested that in many cases, it is not safe to discharge chronically ill older adults to home, especially if timely outpatient follow-up and social support are in question. Taken together, interview themes describe structural features of the healthcare system that funnel patients into a repeated cycle of hospital-based acute care. Recent literature describes a similar cycle. Auerbach, et al., reported that ED decision-making contributes most to preventable hospital admissions15, and yet some of these admissions might be avoided if patients had access to ongoing care coordination and timely follow-up once they leave the ED.16

The potential protective effect of coaching on hospitalization upon ED return requires exploration. The Intervention may impact admissions for patients that return to the ED by affecting the severity of their health condition since the Intervention helps patients develop self-management skills.21 Alternatively, the Intervention may impact ED provider decision-making by influencing the physician’s perception of the patient’s capacity for self-care and care coordination. This is a plausible explanation given recent evidence from an observational study that suggests hospital admissions are reduced at ED visits in which older adults are assigned to a nursing transitional care intervention.25

Study Limitations:

We conducted the study with Medicare beneficiaries, and results may not apply to younger, less-ill individuals. Several important issues may have influenced the study limitation that Intervention uptake was not universal (Figure 1). First, initiation of the Intervention was often delayed until after ED discharge — a delay that may have impaired the trust and rapport needed for patients to feel comfortable allowing a coaching home visit.21,45 Second, the study population was vulnerable as defined by age, race, chronic illness, and proportion eligible for both Medicare and Medicaid (Table 1), factors that influence study engagement and retention, especially in older adults.45 Finally, access to community-based follow-up and support and therefore results, may be location-specific.24 This possibility is supported by evidence from an ED-based transitional care nursing intervention deployed in three hospitals in a large urban area that demonstrated reduced hospital-based acute care in some settings, but increased or no change in others.25,26 Evidence that well-defined Patient Centered Medical Homes may reduce ED use in older adults reinforces the concept that the local healthcare environment influences hospital-based acute care.24

Conclusion:

Reducing ED visits is difficult. Structural features of the healthcare system, including lack of access to timely outpatient care, funnel patients into the ED and hospital admissions. Reducing hospital-based acute care may require increased focus on the local healthcare system rather than patients’ care-seeking decisions. ED alternatives, including virtual primary care visits, community-based care for vulnerable patients, and deployment of trusted, community-based professionals (e.g., pre-hospital professionals, community healthcare workers, public health nurses)27,28 could potentially fill the current gaps in acute care of chronically ill older adults.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors thank the research partners representing the patient and caregiver perspective, Yvonne (Jazz) Davis, Dolly Horlacher, Ron Morris, Dawn Rosini, and Jan Rosini; staff at the local Area Agencies on Aging; and project staff who helped them envision and carry out this project. Their input and participation were invaluable. The authors would also like to thank the patient and physician study participants who openly shared their experiences and perspectives on care-seeking in the ED. This study would not have been possible without their participation. The opinions in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of PCORI, its Board of Governors or Methodology Committee, or the National Institutes of Health.

Funding:

This study was supported by a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute award (IHS-1306-01451). REDCap was supported by the University of Florida Clinical and Translational Science Institute, which is supported in part by the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001427).

Footnotes

No conflicts of interest reported for all authors

References

- 1.National Quality Forum. Emergency Department Transitions of Care: A Quality Measurement Framework. 2017; https://www.qualityforum.org/ProjectDescription.aspx?projectID=83442. Accessed August 15, 2020,.

- 2.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. National Care Transitions Awareness Day promotes safe, effective, person-centered care. 2019; https://www.cms.gov/blog/national-care-transitions-awareness-day-promotes-safe-effective-person-centered-care,. Accessed August 9, 2020.

- 3.Norris SL, High K, Gill TM, et al. Health care for older Americans with multiple chronic conditions: a research agenda. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(1):149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/Value-Based-Programs/HRRP/Hospital-Readmission-Reduction-Program.html. Accessed October 25, 2017.

- 6.American College of Emergency Physicians. The Latest Emergency Department Utilization Numbers Are In. 2019; https://www.acepnow.com/article/the-latest-emergency-department-utilization-numbers-are-in/#:~:text=10%20%E2%80%93%20October%202019-,The%20Numbers,visit%20estimate%20was%2090.3%20million).Accessed June 21, 2020

- 7.Nagurney JM, Fleischman W, Han L, Leo-Summers L, Allore HG, Gill TM. Emergency Department Visits Without Hospitalization Are Associated With Functional Decline in Older Persons. Ann Emerg Med. 2017;69(4):426–433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall AG, Schumacher JR, Brumback B, et al. Health-related quality of life among older patients following an emergency department visit and emergency department-to-home coaching intervention: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Care Coord. 2017;20(4):162–170. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abualenain J, Frohna WJ, Smith M, et al. The prevalence of quality issues and adverse outcomes among 72-hour return admissions in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2013;45(2):281–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hastings SN, Heflin MT. A systematic review of interventions to improve outcomes for elders discharged from the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(10):978–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lowthian JA, McGinnes RA, Brand CA, Barker AL, Cameron PA. Discharging older patients from the emergency department effectively: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2015;44(5):761–770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Caplan GA, Brown A, Croker WD, Doolan J. Risk of admission within 4 weeks of discharge of elderly patients from the emergency department--the DEED study. Discharge of elderly from emergency department. Age Ageing. 1998;27(6):697–702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carrier EYT, Holzwart RA,. Coordination between Emergency and Primary Care Physicians. Washington D.c.,: National Institute for Health Care Reform,;2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocher KE, Dimick JB, Nallamothu BK. Changes in the source of unscheduled hospitalizations in the United States. Med Care. 2013;51(8):689–698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Auerbach AD, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, et al. Preventability and Causes of Readmissions in a National Cohort of General Medicine Patients. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(4):484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Capan M, Pigeon J, Marco D, Powell J, Groner K. We all make choices: A decision analysis framework for disposition decision in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(3):450–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sabbatini AK, Nallamothu BK, Kocher KE. Reducing variation in hospital admissions from the emergency department for low-mortality conditions may produce savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(9):1655–1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Karam G, Radden Z, Berall LE, Cheng C, Gruneir A. Efficacy of emergency department-based interventions designed to reduce repeat visits and other adverse outcomes for older patients after discharge: A systematic review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2015;15(9):1107–1117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler M, et al. Preventing 30-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braet A, Weltens C, Sermeus W. Effectiveness of discharge interventions from hospital to home on hospital readmissions: a systematic review. JBI Database System Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14(2):106–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ. The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lutz BJ, Hall AG, Vanhille SB, et al. A Framework Illustrating Care-Seeking Among Older Adults in a Hospital Emergency Department. Gerontologist. 2018; 58 (5): 942–952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rising KL, Hudgins A, Reigle M, Hollander JE, Carr BG. “I’m Just a Patient”: Fear and Uncertainty as Drivers of Emergency Department Use in Patients With Chronic Disease. Ann Emerg Med. 2016;68(5):536–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, et al. The patient centered medical home. A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158(3):169–178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hwang U, Dresden SM, Rosenberg MS, et al. Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: Transitional Care Nurses and Hospital Use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(3):459–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dresden SM, Hwang U, Garrido MM, et al. Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations: The Impact of Transitional Care Nurses on 30-day Readmissions for Older Adults. Acad Emerg Med. 2020;27(1):43–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shah MN, Hollander MM, Jones CM, et al. Improving the ED-to-Home Transition: The Community Paramedic-Delivered Care Transitions Intervention-Preliminary Findings. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66(11):2213–2220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hudgins A, Rising KL. Fear, vulnerability and sacrifice: Drivers of emergency department use and implications for policy. Soc Sci Med. 2016;169:50–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schumacher JR, Lutz BJ, Hall AG, et al. Feasibility of an ED-to-Home Intervention to Engage Patients: A Mixed-Methods Investigation. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(4):743–751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fetters MD, Curry LA, Creswell JW. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs-principles and practices. Health Serv Res. 2013;48(6 Pt 2):2134–2156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.NVIVO Qualitative Analysis Software [computer program]. Version 11. Melbourne, Australia: QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bowers B Leonard Schatzman and Dimensional Analysis. . In: Morse JMSP, Corbin JM, . Charmaz KC, Bowers B, Clarke AE,, ed. Developing grounded theory: The second generation. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press, Inc. ; 2009:86–121. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strauss A Qualitatiave Analysis for Social Scientists. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schatzman L In: Maines D, ed. Social Organization and Social Process Essays in Honor of Anselm Strauss. Dimensional Analysis: Notes on an Alternative Approach to the Grounding of Theory in Qualitative Research. New York, NY: Aldine De Gruyter.; 1991:303–314. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). How to Identify Hospital Claims for Emergency Room Visits in the Medicare Claims Data. 2015; https://www.resdac.org/articles/how-identify-hospital-claims-emergency-room-visits-medicare-claims-data Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 36.Research Data Assistance Center (ResDAC). Identifying Observation Stays for Those Beneficiaries Admitted to the Hospital. 2015; https://www.resdac.org/articles/identifying-observation-stays-those-beneficiaries-admitted-hospital. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 37.Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Min SJ, Parry C, Kramer AM. Preparing patients and caregivers to participate in care delivered across settings: the Care Transitions Intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(11):1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coleman EA, Boult C, American Geriatrics Society Health Care Systems C. Improving the quality of transitional care for persons with complex care needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):556–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ginde AA, Talley BE, Trent SA, Raja AS, Sullivan AF, Camargo CA Jr. Referral of discharged emergency department patients to primary and specialty care follow-up. The Journal of emergency medicine. 2012;43(2):e151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, Pines JM. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Annals of emergency medicine. 2012;60(1):12–23 e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. HCUP methods series: observation status related to US hospital records. . In. Vol Report No. 2002–03. Rockville, MD2002. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maldonado G, Greenland S. Simulation study of confounder-selection strategies. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;138(11):923–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.SAS/STAT Statistical Software [computer program]. Version 9.4. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stata Statistical Software: Release 13 [computer program]. Version 13. College Station,TX: StataCorp LP; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mody L, Miller DK, McGloin JM, et al. Recruitment and retention of older adults in aging research. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(12):2340–2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.