Abstract

Intravascular catheter break off is a rare complication during insertion or nursing care. We report the intravascular break off of a midline catheter after wound dressing change and its migration into the pulmonary artery. The broken piece of catheter was removed percutaneously using a snare kit.

Keywords: Midline catheter, ultrasound, embolism, interventional radiology, sepsis

Introduction

Midline catheters are unique vascular access devices often referred to as “middle ground” intravenous catheters. 1 Their popularity has been growing recently, especially as a longer-term alternative to “traditional” peripheral venous catheters, and in certain cases they offer a convenient alternative to peripherally inserted central venous catheters (PICCs). 2 They share similar complication risks to other types of intravenous catheters such as infiltration, thrombophlebitis, hematoma, air embolism, catheter-associated blood stream infection and nerve, tendon, or ligament injury.3,4 An uncommon but potentially even more serious complication of their use is intravascular damage of the catheter and upstream migration of a broken piece to the central circulation. 5

Case Description

A 75-year-old woman was indicated for long-term antibiotic treatment of infectious complications after right hip joint replacement. Due to unfavorable peripheral vascular access we decided to use “middle ground” intravenous catheter. Using ultrasound navigation, a midline catheter (Arrow®, 18G, single lumen) was inserted without complication, from a single puncture into the left brachial vein, fixed to the skin, and the insertion site was covered using Curapor® wound dressing.

Shortly afterward the infusion of antibiotics was started continued by crystalloid infusion. The patient received Low Molecular Weight Heparin (LMWH) as thromboembolism prophylaxis, and due to a moderate bleeding at the injection site frequent dressing changes were required. After 1 dressing change, on the first day of catheter use, the patient began to complain of fluid leaking around the catheter. After removal of the sterile dressing, damage to the catheter was detected, the catheter appeared to be completely severed and only plastic catheter wings remained fixed to the skin. The cause of the damage was the usage of a sharp object when removing the sterile dressing.

Typically, soiled dressings are easily removed when wet, however, in this case the dressing was tightly adhered to the catheter which lead to the nurse’s decision to use scissors to assist removal. In addition, the catheter’s position was visually occluded by significant bleeding around the puncture site.

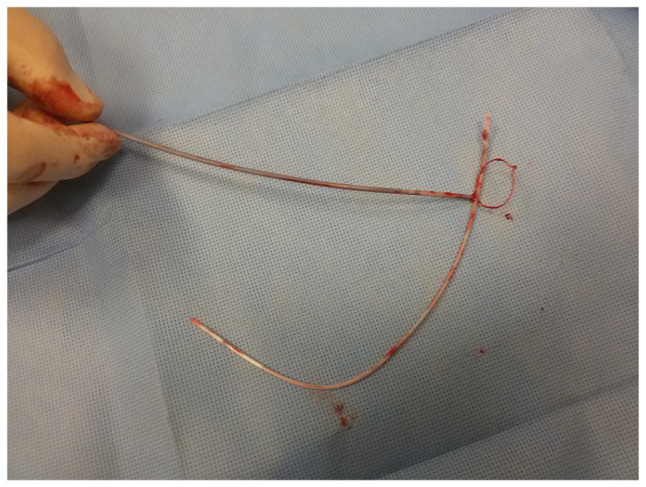

Radiograph of the left upper limb was performed (Figure 1), and subsequently an AP image of the chest (Figure 2). The contour of catheter was visible in the area of the pulmonary artery, kinked twice, and directed toward the right branch of the PA. We consulted an interventional radiologist and decided to attempt emergent percutaneous removal of the fragment. Using the right femoral venous approach, a 6F Snare kit with a 20 mm loop was successfully used to extract the catheter (Figure 3). We verified the integrity of the catheter’s fragment and ensured that nothing remain in the pulmonary circulation (Figure 4). Fortunately this rare complication had no significant sequelae and the patient was discharged from hospital in stable condition.

Figure 1.

Radiograph of the left upper limb.

Figure 2.

Chest radiograph with highlighted catheter fragment in the area of the pulmonary artery.

Figure 3.

Extracted embolized catheter’s fragment.

Figure 4.

Comparison of intact and damaged catheter.

Discussion

The prolonged use of indwelling intravenous catheters has become increasingly common as well as the incidence of associated complications, including the rarer ones such as catheter fragment embolization. Catheter embolization is the term generally applied to catheter fragments that embolize to various locations including the pulmonary arteries. 4 Literature review advocates immediate removal of catheter fragments due to high incidence of complications including transient arrhythmias, sepsis, thrombus formation on the catheter, pulmonary embolization, arrhythmias, myocardial inflammation, and eventually death.6,7 Although the available reviews recommend immediate removal of a foreign body from the venous system, some authors advocate a conservative approach with radiographic follow up with quantification of the potential complications based on the location of the embolus, especially in asymptomatic patients.8,9 Although a number of minimally invasive techniques for removing embolus fragments by the percutaneous route are known, 6 due to the risk of failure of these procedures the potential necessity of open surgery remains with all its potential consequences. This emphasizes the importance of prevention of such complications. Most of the recommendations focus on the correct technique of catheter insertion. Equally important, however, is the follow-up nursing care. The literature mentions possible damage to the catheter when flushing under high pressure and recommends avoiding the use of small-volume syringes, 10 but that was not the case. A less mentioned but even more dangerous risk factor for catheter damage is untrained nursing staff.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank to Martin Pochop M.D. for language correction.

Footnotes

Funding: The author(s) received financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The article was supported by Military University Hospital Grant MO 1012..

Declaration Of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent: The patient provided written informed consent for all information and images to be published.

ORCID iD: Michal Soták  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4107-8352

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4107-8352

References

- 1. Anderson NR. Midline catheters: the middle ground of intravenous therapy administration. J Infus Nurs. 2004;27:313-321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Adams DZ, Little A, Vinsant C, Khandelwal S. The midline catheter: a clinical review. J Emerg Med. 2016;51:252-258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Steele J. Practical IV Therapy. 2nd ed. Springhouse Corp; 1996:68-69-86-99. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Singh S, Prakash J, Shukla VK, Singh LK. Intravenous catheter associated complications. J Assoc Physicians India. 2010;58:194-196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Thanigaraj S, Panneerselvam A, Yanos J. Retrieval of an IV catheter fragment from the pulmonary artery 11 years after embolization. Chest. 2000;117:1209-1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fisher RG, Ferreyro R. Evaluation of current techniques for nonsurgical removal of intravascular iatrogenic foreign bodies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1978;130:541-548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bernhardt LC, Wegner GP, Mendenhall JT. Intravenous catheter embolization to the pulmonary artery. Chest. 1970;57:329-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Graham KJ, Barratt-Boyes BG, Cole DS. Catheter emboli to the heart and pulmonary artery. Br J Surg. 1970;57:184-186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Székely J, Rácz L, Karátson A. Broken piece in the lungs: a complication of haemodialysis via subclavian cannulation. Int Urol Nephrol. 1989;21:533-540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Chow LM, Friedman JN, Macarthur C, et al. Peripherally inserted central catheter (PICC) fracture and embolization in the pediatric population. J Pediatr. 2003;142:141-144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]