Abstract

Background

The systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), a novel and cost-effective serum biomarker, is associated with prognosis in patients with cancer. However, the prognostic value of the SIRI in cancer remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the potential role of the SIRI as a prognostic indicator in cancer.

Methods

Reports in which the prognostic value of the SIRI in cancer was evaluated were retrieved from electronic databases. The pooled hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated to evaluate the prognostic significance of the SIRI. The odds ratio (OR) was also calculated to explore the association between the SIRI and clinicopathological features.

Results

This study included 30 retrospective studies with 38 cohorts and 10 754 cases. The meta-analysis indicated that a high SIRI was associated with short overall survival (OS) (HR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.82–2.29, P < .001) and disease-free survival (DFS)/recurrence-free survival (RFS)/progression-free survival (PFS) (HR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.84–2.34, P < .001). Subgroup analysis showed that the prognostic value of the SIRI was significant in all kinds of cancer included. Moreover, the SIRI was significantly correlated with sex, tumor size, T stage, N stage, TNM stage, and lymphovascular invasion.

Conclusion

The pretreatment SIRI could be a promising universal prognostic indicator in cancer.

Keywords: systemic inflammation response index, biomarker, cancer, prognosis, meta-analysis

Introduction

There is increasing evidence that inflammation, as a recognized hallmark feature of cancer, is a key prognostic factor for disease progression and survival in most malignant tumors. 1 Inflammatory cells are generic constitutions of tumors and they play conflicting roles. Tumor-promoting inflammatory cells include macrophage subtypes, mast cells, and neutrophils, as well as some subclasses of T and B lymphocytes.1-3 And these inflammatory cells can release signaling molecules as effectors to promote tumor angiogenesis, to stimulate tumor cell proliferation, and to facilitate tissue invasion and metastatic dissemination.4,5 On the other hand, innate immune cell types and other subclasses of B and T lymphocytes can produce tumor-killing responses. Tumors can induce inflammatory response through a variety of mechanisms, including releasing chemotactic factors to recruit macrophages, releasing damage-associated molecular patterns to activate granulocytes and neutrophils, and acidification of the tumor microenvironment to develop cancer-induced inflammatory response. 6 What’s more, inflammatory response begins at the earliest stages of tumor progression to foster the progression of immaturity tumors into full-fledged cancers.4,7 Therefore, inflammatory cells and inflammatory factors play an important role in tumorigenesis and tumor progression. The cancer-induced inflammatory response leads to changes in neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets in the peripheral blood, which can be used to predict the survival of patients with cancer. 8 Although the interaction between inflammatory responses and tumor hosts is complex, and the key process of this response is far from fully understood. Systemic inflammatory responses such as the platelet/lymphocyte ratio (PLR), neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio (NLR), and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio (MLR) have been reported to be independent prognostic markers in many kinds of cancer.9-12 In addition, an innovative inflammation-related biomarker named the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI), which was developed in 2016 and is calculated as neutrophils × monocytes/lymphocytes in pretreated peripheral blood samples, may well reflect the cancer-related inflammatory response. 13

The SIRI was first developed to predict the survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy and was shown to be useful to reflect the status of systemic inflammation. 13 Because it is noninvasive, cost-effective, and easily accessible, the universality of its prognostic value in many kinds of cancer, including pancreatic cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, gastric cancer, esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, clear cell renal cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction, non-small cell lung cancer, and upper tract urothelial carcinoma, taken together or categorized as urinary system, respiratory system, digestive system, and head and neck cancers, was tested in subsequent years.13-21 By 2019, eleven studies and a systematic review of these articles showed that the pretreatment SIRI was a useful predictive marker of an adverse prognosis. 22

Furthermore, the SIRI, as a prognostic indicator of cancer, received much attention in 2020. It was tested in more types of cancer, such as oral squamous cell carcinoma, 23 gallbladder cancer, 24 breast cancer, 25 and cervical cancer, 26 and such studies have facilitated the exploration of a more precise classification and the prognostic value of the SIRI in different cancers. In addition, though many studies affirmed the value of the SIRI in prognosis, several studies reached the opposite conclusion or did not include the SIRI in the multivariate analysis.25,27 Therefore, to achieve a more comprehensive assessment of the prognostic value of the SIRI, we performed a new meta-analysis in patients with cancer by pooling data from all available publications. We also explored the relationships between the SIRI and clinicopathological parameters, which were not illuminated in the previous systematic review, to help us understand the potential mechanisms of the SIRI in cancer.

Methods

This meta-analysis was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 28 Two authors (SS and WY) retrieved and screened the reports independently, and a consensus was reached through discussion. If the authors could not reach a consensus, a third researcher made the final decision. This study was not registered.

Literature Search Strategy

We performed a comprehensive literature search in the PubMed, Embase, and Web of Science databases using the following keywords to identify all relevant studies on the prognostic value of the SIRI in patients with all kinds of cancer published up to December 31, 2020: (“systemic inflammation response index” OR SIRI) AND (cancer OR neoplasm OR malignancy OR carcinoma OR tumor). The references and citations of the retrieved publications were also examined to identify other relevant studies.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The inclusion criteria used in the meta-analysis were as follows: (1) patients confirmed to have cancer by a pathology assessment; (2) studies that investigated the association of the SIRI with overall survival (OS), disease-free survival (DFS), recurrence-free survival (RFS), progression-free survival (PFS), or clinicopathological features; (3) studies in which patients were divided into two groups according to the SIRI, and the cutoff value of the SIRI was reported; and (4) studies that supplied sufficient information for direct extraction or indirect estimation of hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) reviews, case reports, or conference abstracts; and (2) studies with insufficient data to calculate the HR and 95% CI. In addition, when multiple studies were based on identical datasets, only the most informative study was included to avoid duplication.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two authors independently extracted the data from all included studies. The following information was recorded: the first author’s name, publication year, country, number of patients, trial design, therapy, cancer type, cutoff value of the SIRI and the selection method, median follow-up time and range, use of a multivariate or univariate model, HR and 95% CI for OS and DFS/RFS/PFS, and clinicopathological parameters. If both univariate and multivariate HRs with 95% CIs were available in the same study, we chose the multivariate data to avoid confusion. If any of the above data were not reported directly, items were recorded as “not reported” (NR).

Additionally, the quality of each included study was evaluated independently by two authors according to the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which included an assessment of selection, comparability of groups, and exposure. 29 The final score ranged from 0 to 9, and any study that scored ≥7 was considered high quality.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using Stata 12.0 statistical software. OS and DFS/RFS/PFS were analyzed to evaluate the prognostic effect of the SIRI in cancer, reported as HRs with 95% CIs. A single united parameter was used for DFS, RFS, and PFS because of their similar meaning. The correlations between the SIRI and clinicopathological characteristics were evaluated through odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Heterogeneity was statistically examined by the χ 2 -based Q statistic and inconsistency index (I 2 ). If the χ 2 P value was <.1 or the I 2 value was >50%, it was defined as statistically significant heterogeneity, and the random-effects model was applied for the subsequent analysis; otherwise, the fixed-effects model was used. A cumulative meta-analysis by publication year was performed to investigate the trends of the results over time. Result stability was evaluated by sensitivity analyses, in which each study was excluded to test its impact on the results. Funnel plots were generated, and Begg’s test and Egger’s tests were performed to assess potential publication bias. For all these analyses, a two-sided P value <.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Selection

A total of 935 studies were initially identified by the systematic literature search, and 792 remained after the removal of duplicates. A total of 755 articles were excluded after reviewing the title and abstract because they were irrelevant to the topic. From the 37 remaining studies, 30 were included after reading the full texts.13-15,17-21,23-27,30-46 The reasons for exclusion were as follows: one did not report information on OS/DFS/RFS/PFS or clinicopathological data; one was a duplicate report; and five had insufficient data for a quantitative analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The flow chart of this meta-analysis.

Characteristics of the Included Studies

From the 30 retrospective studies published between 2016 and 2020, 38 cohorts and 10754 cases were included in our analysis (Table 1). Among these cohorts, 32 reported OS and 11 reported DFS/RFS/PFS. In addition, 20 studies indicated a relationship between the SIRI and clinicopathologic features. Most studies were carried out in China, and only eight were carried out in other countries, including six in Turkey, one in Japan, and one in Spain/Canada. Many cancer types were included in these studies, such as pancreatic cancer (seven cohorts), head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (seven cohorts), hepatobiliary cancer (three cohorts), esophageal cancer (three cohorts), lung cancer (five cohorts), urologic neoplasms (three cohorts), breast cancer (three cohorts), cervical cancer (two cohorts), gastric cancer (three cohorts), glioblastoma multiforme (one cohort), and soft tissue sarcoma (one cohort). Surgical excision was used in some studies, while other therapies, such as chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy, were used in others. The sample sizes ranged from 33 to 949, and the range of cutoff values for the SIRI was .54–3.26. The SIRI was incorporated into a multivariate analysis in most studies; however, only two studies did not incorporate it into the multivariate analysis, and the univariate analysis results were used. According to the NOS, the scores of all 24 studies were 7 or 8, indicating that all studies were of high quality (Table 2).

Table 1.

Main Characteristics of the Eligible Studies.

| Author | Year | Country | No. of Patients | Trial design | Therapy | Cancer Type | Cutoff Value of SIRI (×109) | Follow-Up (months) Medium (Range) | Outcomes | Model | NOS Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qi-training cohort | 2016 | China | 177 | RC | Chemotherapy | PC | ≥1.8 | NR | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Qi-validation cohort 1 | 2016 | China | 321 | RC | Chemotherapy | PC | ≥1.8 | NR | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Qi-validation cohort 2 | 2016 | China | 76 | RC | Chemotherapy | PC | ≥1.8 | NR | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Li- primary cohort | 2017 | China | 455 | RC | Resection | GC | ≥.82 | 77.53 (3.03–111.73) | DFS | Multi | 8 |

| Li-validation cohort | 2017 | China | 327 | RC | Resection | GC | ≥.82 | 56.33 (4.9–76.3) | DFS | Multi | 8 |

| Xu | 2017 | China | 183 | RC | Local therapy | HCC | ≥1.05 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Geng-primary cohort | 2018 | China | 542 | RC | Resection | ESCC | ≥1.2 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Geng-validation cohort | 2018 | China | 374 | RC | Resection | ESCC | ≥1.2 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Chen- primary cohort | 2018 | China | 285 | RC | NR | NPC | ≥.84 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Chen-validation cohort | 2018 | China | 213 | RC | NR | NPC | ≥.84 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Chen Y | 2019 | China | 302 | RC | Resection | AEG | ≥.68 | 55 (4-98) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Chen Z | 2019 | China | 414 | RC | Resection | CCRCC | ≥1.35 | 69.2 (1-151) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Li S- primary cohort | 2019 | China | 371 | RC | Resection | PDAC | ≥.69 | NR | OS、RFS | Multi | 8 |

| Li S- validation cohort | 2019 | China | 310 | RC | Resection | PDAC | ≥.69 | NR | OS、RFS | Multi | 8 |

| Li SJ | 2019 | China | 390 | RC | Resection | LC | ≥.99 | 50.0 (12–66) | OS、DFS | Multi | 8 |

| Zheng-- primary cohort | 2019 | China | 259 | RC | Resection | UTUC | ≥1.36 | 33.3 | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Zheng-validation cohort | 2019 | China | 274 | RC | Resection | UTUC | ≥1.36 | 33.3 | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Zeng | 2020 | China | 255 | RC | NR | NPC | ≥1.529 | 33.5 (2.1–151.2) | OS、DFS | Multi | 7 |

| Cinkir-1 | 2020 | Turkey | 133 | RC | Chemotherapy | LC | ≥2 | 10.46 (.7–99.5) | OS | Uni | 8 |

| Çınkır-2 | 2020 | Turkey | 80 | RC | Sorafenib | HCC | ≥2.2 | 7.35 (1.7–31.2) | OS、DFS | Uni | 6 |

| Çınkır-3 | 2020 | Turkey | 94 | RC | NR | LC | ≥2.81 | NR | OS | Multi | 6 |

| Pacheco-Barcia | 2020 | Spain/Canada | 164 | RC | NR | PC | ≥2.3 | NR | OS、PFS | Multi | 7 |

| Lin | 2020 | China | 535 | RC | Resection | OSCC | ≥1.14 | NR | OS | Multi | 7 |

| Wang | 2020 | China | 949 | RC | NR | BC | ≥.65 | 102 | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Sun | 2020 | China | 124 | RC | Resection | GBC | ≥.89 | 20 (.5–153) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Hua | 2020 | China | 390 | RC | Resection | BC | ≥.54 | 65.5 (.9–95.9) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Chen | 2020 | China | 262 | RC | Chemotherapy | BC | ≥.85 | NR | OS、DFS | Multi | 7 |

| Chao- primary cohort | 2020 | China | 441 | RC | Resection | CC | ≥1.25 | 67 (6–129) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Chao-validation cohort | 2020 | China | 164 | RC | Resection | CC | ≥1.25 | 67 (6–129) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Zhou | 2020 | China | 367 | RC | Resection | HNSCC | ≥1.34 | 27.2 (2–48) | OS、DFS | Multi | 7 |

| Topkan-1 | 2020 | Turkey | 154 | RC | Chemoradiotherapy | PC | ≥1.6 | 14.3 (2.9–74.6) | OS、DFS | Multi | 8 |

| Topkan-2 | 2020 | Turkey | 181 | RC | Resection | GBM | 1.78 | 15.9 (1.0–108.7) | - | Multi | 8 |

| Gao | 2020 | China | 240 | RC | Resection | GC | ≥1.2 | NR | OS、DFS | Multi | 8 |

| Hu | 2020 | China | 176 | RC | Chemoradiotherapy | LC | ≥2 | 21.7 (3.1–121) | OS | Multi | 8 |

| Feng | 2020 | China | 417 | RC | Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy | NPC | ≥.86 | NR | OS、PFS | Multi | 8 |

| Chuang | 2020 | China | 141 | RC | Radiotherapy or chemoradiotherapy | LHPC | 3.26 | 45.8 (3–91) | OS、PFS | Multi | 8 |

| Kucuk | 2020 | Turkey | 181 | RC | Chemoradiotherapy | LC | 1.93 | 17.9 | - | Multi | 8 |

| Kobayashi | 2020 | Japan | 33 | RC | Chemoradiotherapy | STS | 1.5 | NR | - | Multi | 7 |

Abbreviations: RC, Retrospective cohort study; PC, Pancreatic Cancer; GC, Gastric Cancer; HCC, Hepatocellular Carcinoma; ESCC, Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma; NPC, Nasopharyngeal Carcinoma; AEG, Adenocarcinoma of the Esophagogastric Junction; CCRCC, Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma; PDAC, Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma; LC: Lung Cancer; UTUC, Upper Tract Urothelial Carcinoma; OSCC, Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma; BC, Breast Cancer; GBC, Gallbladder Cancer; CC, Cervical Cancer; HNSCC, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma; GBM, Glioblastoma Multiforme; LHPC, Laryngeal/Hypopharyngeal Cancer; STS, Soft Tissue Sarcoma; NR, Not reported; OS, overall survival; DFS, disease-free survival; RFS, recurrence-free survival; MFS, metastatic-free survival.

Table 2.

The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) Quality Assessment of the Included Studies.

| Study ID | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Representativeness of the Exposed Cohort | Selection of the Non-exposed Cohort | Ascertainment of Exposure | Demonstration that Outcome of Interest was Not Present at Start of Study | Comparability of Cohorts on the Basis of the Design or Analysis (Study Adjusts for Age and Sexa) | Assessment of Outcome | Was Follow-Up Long Enough for Outcomes to Occur | Adequacy of Follow-up of Cohorts | ||

| Qi et al, 2016 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Li et al, 2017 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Xu et al, 2017 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Geng et al, 2018 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Chen et al, 2018 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Chen Y et al, 2019 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Chen Z et al, 2019 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Li S et al, 2019 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Li SJ et al, 2019 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Zheng et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Zeng et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Cinkir-1 et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Çınkır-2 et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | -- | a | a | a | 6 |

| Çınkır-3 et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | - | - | 6 |

| Pacheco-Barcia et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Lin et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Wang et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Sun et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Hua et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Chen et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

| Chao et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Zhou et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | - | a | 7 |

| Topkan-1 et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Turkey-2 et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Gao et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Hu et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Feng et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Chuang et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Kucuk et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | a | 8 |

| Kobayashi et al, 2020 | - | a | a | a | b | a | a | - | 7 |

aMeans 1 score

bMeans 2 scores.

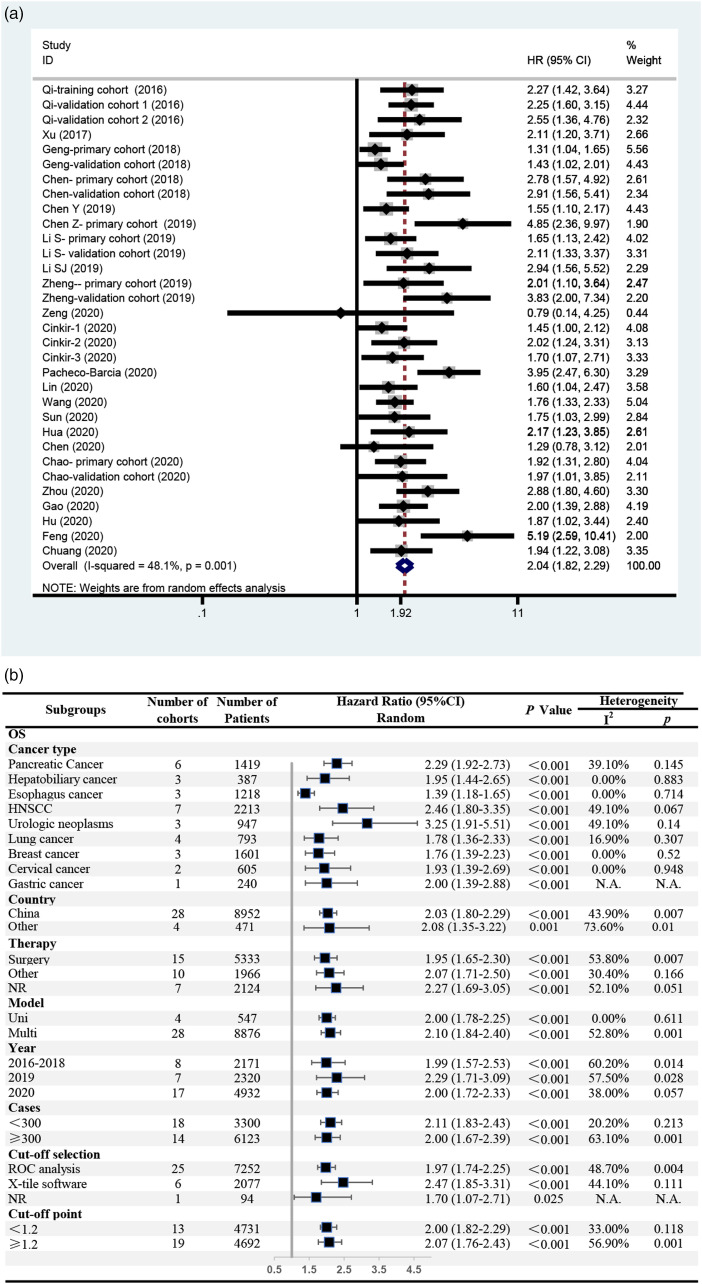

Correlation Between the SIRI and OS

Twenty-five studies reported OS, with a total of 32 independent cohorts and 9423 patients. The meta-analysis confirmed that a high SIRI was associated with short OS among patients with cancer (HR = 2.04, 95% CI = 1.82–2.29, P < .001) (Figure 2(A)). Significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 48.1%, P = .001), and a random-effects model was used. Subgroup analyses were conducted to further evaluate the potential sources of heterogeneity, including cancer type, country, therapy, analysis model, publication year, number of cases, method of cutoff selection, and cutoff point for the SIRI (Figure 2(B)). First, the effect of cancer type was examined. The results showed that a high SIRI was associated with short OS in patients with all these kinds of cancer, most with no heterogeneity (I2 < 50%, P > .10). Urologic neoplasms yielded the highest HR (HR = 3.25, 95% CI = 1.91–5.51, P < .001), and esophageal cancer yielded the lowest HR (HR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.18–1.65, P < .001). Furthermore, in the other subgroups, significant heterogeneity (I2 > 50% or P < .10) could be found in at least one group. However, all the subgroup analyses showed a significant association between the SIRI and OS (HR = 1.70–2.47, P < .05).

Figure 2.

The association between SIRI and OS among patients with cancer. (A) Meta-analysis; (B) subgroup analyses.

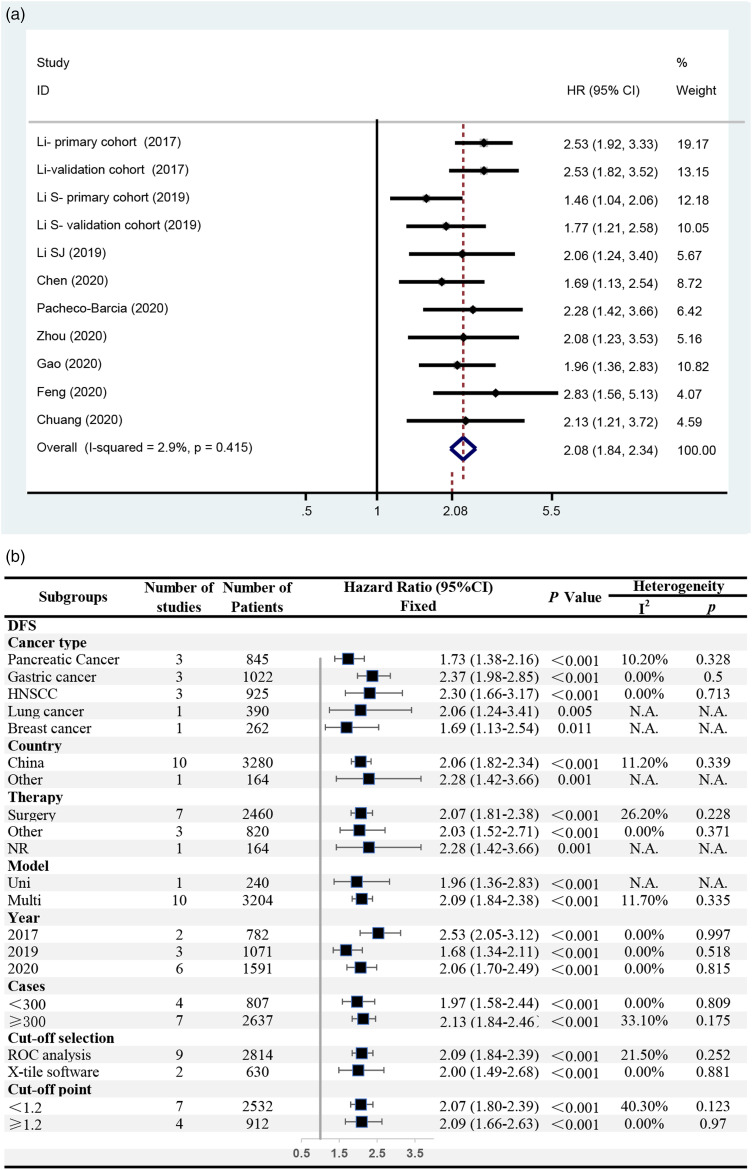

Correlation Between the SIRI and DFS

A total of 9 studies reported DFS/RFS/PFS, including 11 independent cohorts and 3444 cases. The meta-analysis confirmed that a high SIRI was associated with short DFS/RFS/PFS among patients with cancer (HR = 2.08, 95% CI = 1.84–2.34, P < .001). No significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 2.9%, P = .415), and a fixed-effects model was used (Figure 3(A)). The subgroup analysis showed that a high SIRI was significantly associated with short DFS/RFS/PFS in all the subgroups that could proceed with a pooled analysis (HR = 1.68–2.53, P < .05), with no significant heterogeneity (I2 < 50%, P > .10) (Figure 3(B)).

Figure 3.

The association between SIRI and DFS/RFS/PFS among patients with cancer. (A) Meta-analysis; (B) subgroup analyses.

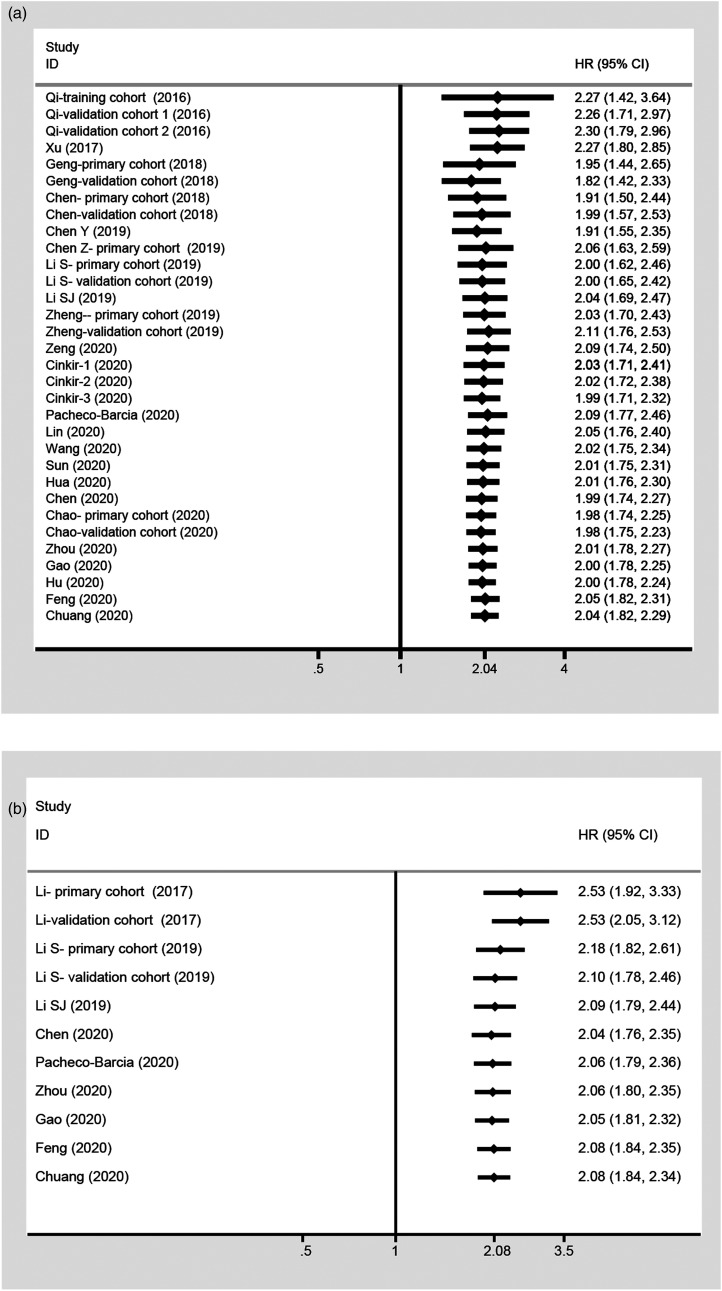

Implications of the Cumulative Meta-Analysis

A cumulative meta-analysis was performed by publication year to investigate the temporal trends. The analyses of OS and DFS/RFS/PFS indicated that the association between the SIRI and prognosis was statistically significant and became increasingly stable with an increasingly narrow CI (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Cumulative meta-analysis of the association between SIRI and prognosis. (A) OS; (B) DFS/RFS/PFS.

Relationships Between the SIRI and Clinicopathological Characteristics

The associations between the SIRI and clinicopathological features of cancer patients were evaluated to comprehensively understand the role of the SIRI as a biomarker in the prognosis of cancer. Twenty studies were included, from which nine features were extracted for our analyses. The results indicated that the SIRI was significantly associated with sex (male vs female, OR = .58, 95% CI = .46–.74, P < .001), tumor size (<5 vs>5, OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.33–2.03, P < .001), T stage (T1/T2 vs T3/T4, OR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.48–2.46, P < .001), N stage (N0 vs N1/N2/N3, OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.18–1.69, P < .001), TNM stage (TNM1 vs TNM2/TNM3, OR = 1.72, 95% CI = 1.36–2.18, P < .001), and lymphovascular invasion (absence vs presence, OR = 2.02, 95% CI = 1.26–3.24, P = .004) but not age, perineural invasion, or tumor differentiation degree (Table 3).

Table 3.

Meta-Analysis of the Reported Clinicopathologic Characteristics in the Enrolled Studies.

| Parameters | Number of Studies | Number of Patients | Test for Association | Test for Heterogeneity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | I2 | P | Model | |||

| Gender (male vs female) | 17 | 6835 | .58 | (.46–.74) | <.001* | 74.20 | < .001 | Random |

| Age (≤60 vs > 60) | 5 | 2389 | 1.15 | (.82–1.60) | .416 | 72.10 | < .001 | Random |

| Age (≤65 vs > 65) | 5 | 1496 | 1.22 | (.76–1.95) | .403 | 62.60 | .030 | Random |

| Age (< 50 vs≥50) | 3 | 1628 | .97 | (.79–1.19) | .778 | .00 | 1.000 | Fixed |

| Size (< 5 vs > 5) | 4 | 1928 | 1.64 | (1.33–2.03) | < .001* | .00 | .552 | Fixed |

| T Stage (T1 + T2 vs T3 + T4) | 11 | 5357 | 1.91 | (1.48–2.46) | < .001* | 65.20 | .001 | Random |

| N stage (N0 vs N1 + N2 + N3) | 13 | 6441 | 1.41 | (1.18–1.69) | < .001 | 47.30 | .030 | Random |

| TNM stage (I vs II–III) | 9 | 4322 | 1.72 | (1.36–2.18) | < .001 | 53.80 | .027 | Random |

| Lymphovascular invasion (absence vs presence) | 5 | 2880 | 2.02 | (1.26–3.24) | .004 | 75.70 | .002 | Random |

| Perineural invasion (absence vs presence) | 2 | 1463 | 2.31 | (.75–7.06) | .143 | 94.60 | < .001 | Random |

| Differentiation degree (low vs moderate/high) | 5 | 3238 | .82 | (.52–1.30) | .397 | 86.60 | < .001 | Random |

*Means P < .05.

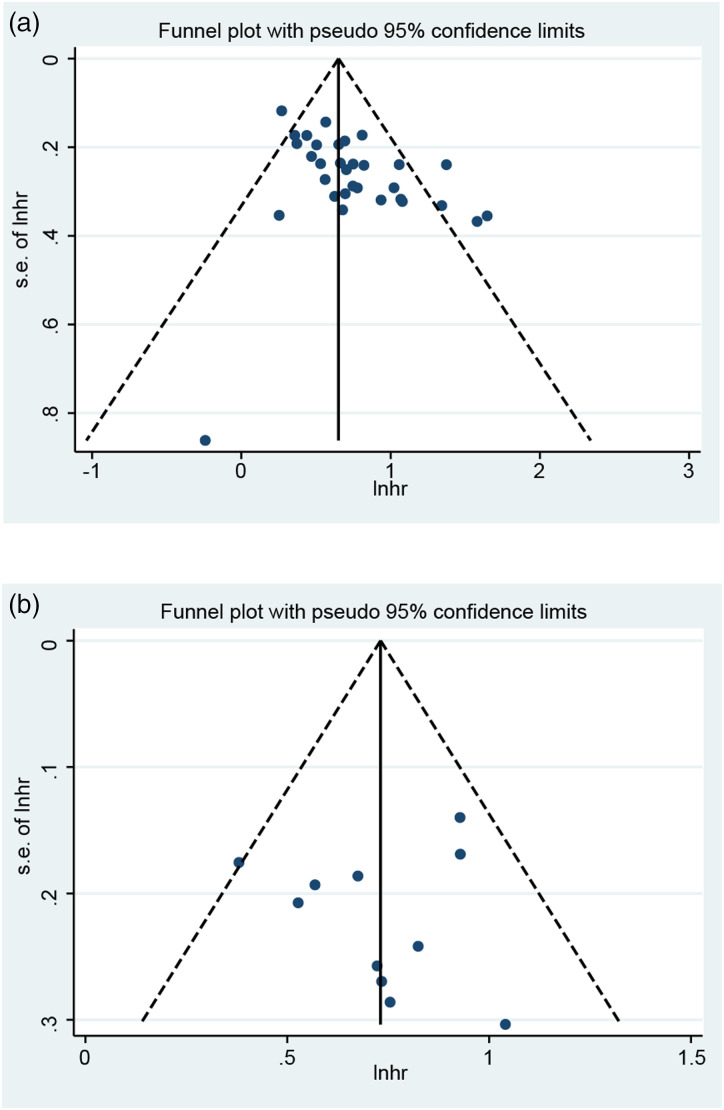

Publication Bias

A funnel plot was generated, and Egger’s test and Begg’s test were performed to assess publication bias. As shown in Figure 5(A), the distribution of the OS funnel plot was asymmetric, which indicated publication bias. Egger’s test (P < .001) and Begg’s test (P = .019) further indicated a risk of publication bias for OS. For DFS/RFS/PFS, visual estimation of the funnel plot was also asymmetric (Figure 5(B)). In addition, Egger’s test (P = .004) and Begg’s test (P = .029) further showed the existence of publication bias.

Figure 5.

Funnel plots of the association between SIRI and prognosis. (A) OS; (B) DFS/RFS/PFS.

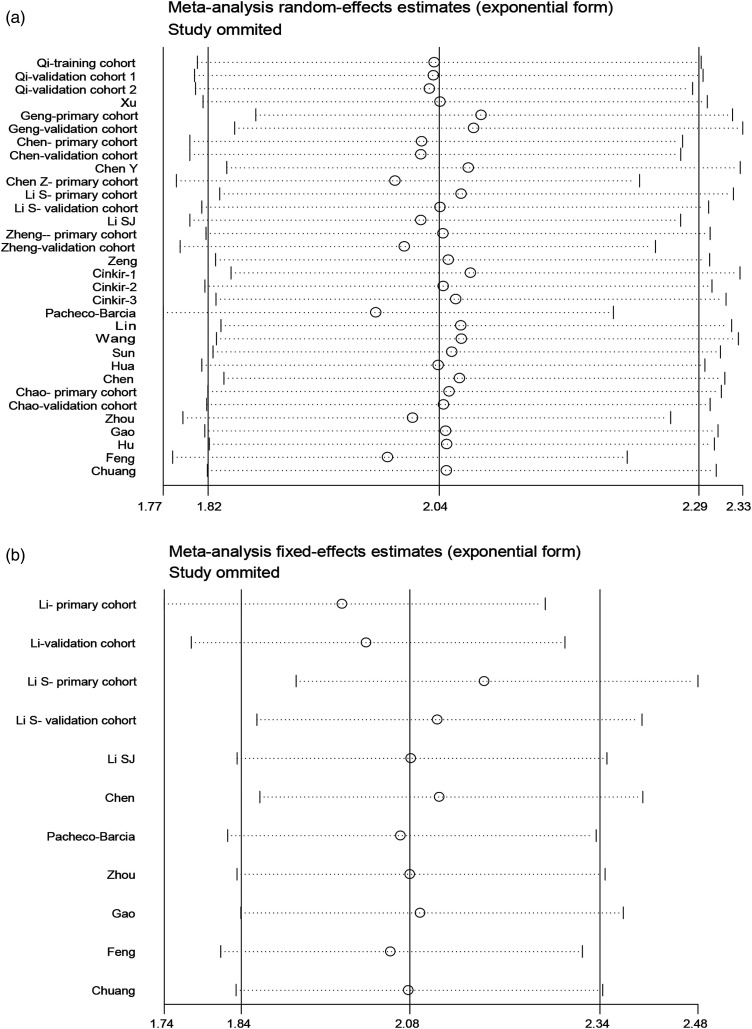

Sensitivity Analysis

To determine the impact of individual studies on the aggregate results, we removed all studies in turn. The meta-analysis of the correlation between the SIRI and OS did not change significantly after the removal of each study, and the same was true for DFS/RFS/PFS, showing that the association between the SIRI and prognosis was robust (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Sensitivity analysis between SIRI and prognosis. (A) OS; (B) DFS/RFS/PFS.

Discussion

The SIRI, as a noninvasive, easily accessible, cost-effective, and feasible index, is a promising indicator that can be used to reflect local and systemic inflammatory responses, and its prognostic value has been identified by an increasing number of studies in different kinds of cancer. 13 However, the prognostic value of the SIRI in cancer is still not explicit. In the two meta-analyses that have been published so far, limited studies were included (11 studies and 14 studies), and the relationships between the SIRI and clinicopathological parameters were not examined.22,47 Thus, we performed this meta-analysis using all available literatures to assess the prognostic influence of the SIRI and to explore the possible mechanism of its effect on cancer. We found that a high SIRI before treatment was associated with a poor prognosis in cancer patients.

Based on the current study, which included 10 754 cases, we found that the SIRI was a significantly poor prognostic factor, with different risk indexes, in all the cancer types studies. The risk of death in patients with urologic cancer was increased by more than 200% in the high SIRI group compared with the low SIRI group, and the risk of death in patients with most other cancers, such as pancreatic cancer and hepatobiliary cancer, was increased by approximately 100%. In addition, the prognostic value of the SIRI was reliable. It was unaffected by country, therapy, study period and method, and the cutoff value for the SIRI. For DFS/RFS/PFS, a high SIRI showed a risk index similar to that of OS. The results of DFS/RFS/PFS, which have been analyzed in only 5 kinds of cancer, also revealed significant association with SIRI in all subgroup analyses. In addition, the cumulative meta-analysis showed that the prognostic influence of the SIRI was significant and became increasingly stable with time. Together with the results of the sensitivity analysis, we also found that the prognostic value of the SIRI was reliable.

Furthermore, the SIRI was found to be significantly associated with sex, tumor size, lymphovascular invasion, and cancer stage, including T stage, N stage, and TNM stage. These findings may indicate the role of the SIRI in cancer prognosis. It is now generally accepted that cancer-related inflammation is an important feature of cancer.8,48 The cancer-induced inflammatory response is caused by inflammatory cells and mediators and leads to changes in neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and platelets in the peripheral blood. 8 These inflammatory reactions, as an anti-damage response to endogenous or exogenous damage, play a vital role in the development of tumors. Many studies have shown the potential mechanisms involved. Neutrophils have been found to promote the formation of an inflammatory microenvironment, thereby promoting tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis. 49 Neutrophils can release angiogenic factors, such as angiopoietin-1, vascular endothelial growth factor, and fibroblast growth factor-2, which play an important role in tumor-related angiogenesis. 50 Lymphocytes are protective prognostic factors for cancer patients. A decline of lymphocytes can cause immune disorders and cytokines secreted by circulating lymphocytes, which inhibit tumor cell proliferation and metastasis. 51 For monocytes, it has been shown that tumor-activated macrophages are differentiated from circulating monocytes, and these macrophages may affect tumor angiogenesis and promote tumor growth, invasion, and migration.52,53 Therefore, it is not difficult to understand why the SIRI, which combines the numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, and monocytes, reflects tumor-induced inflammation and serves as a marker for tumor prognosis.

A variety of inflammation-related markers based on routine blood examinations have already been reported in tumor prognosis studies. The SIRI was found to exhibit superior prognostic value compared to other inflammatory indexes. Wang et al found that the SIRI was better in predicting OS in operable breast cancer patients than the NLR, PLR, and MLR through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. 33 In addition, only the SIRI but not the NLR, PLR, or MLR was found to be an independent prognostic factor for patients with operable cervical cancer. 26 In summary, the SIRI is a promising index that can be used to predict the prognosis of cancer patients because of its convenience, availability, and universality. It can also be used to assess the individual benefits of surgery, chemotherapy, or other treatments in cancer patients. Moreover, inflammatory conditions are important for many kinds of diseases. The SIRI, as a reliable indicator that can reflect systemic inflammation, has more potential value to be explored.

Some limitations to our meta-analysis must be acknowledged. First, publication bias was found in the analysis of OS and DFS/RFS/PFS. However, the sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled result for OS was robust and reliable. Because it is difficult to publish negative results and data cannot be extracted from articles with negative results, we should take an objective view of the results of this meta-analysis. Second, we did not evaluate other prognostic indexes, such as cancer-specific survival (CSS), disease-specific survival (DSS), and metastasis-free survival (MFS), because articles including these indexes are limited. Third, the studies included were mainly from China, and studies with high quality from more regions are required in the future.

Conclusions

The pretreatment SIRI is associated with poor OS and DFS/RFS/PFS in human cancer, and its prognostic influence is universal in different kinds of cancer, which indicates that the SIRI is a promising prognostic marker for cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the American Journal Experts for helping us edit grammar, phrasing, and punctuation and improve the flow and readability of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: (I) Conception and design: Tao Wang; (II) Administrative support: Tao Wang; (III) Provision of study materials or patients: Tao Wang; (IV) Collection and assembly of data: Qian Zhou, Si Su and Wen You; (V) Data analysis and interpretation: Qian Zhou, Si Su and Wen You; (VI) Manuscript writing: All authors; (VII) Final approval of manuscript: All authors.

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: The next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646-674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeNardo DG, Andreu P, Coussens LM. Interactions between lymphocytes and myeloid cells regulate pro- versus anti-tumor immunity. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:309-316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, Werb Z. Tumors as organs: Complex tissues that interface with the entire organism. Develop Cell. 2010;18:884-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian B-Z, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141:39-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murdoch C, Muthana M, Coffelt SB, Lewis CE. The role of myeloid cells in the promotion of tumour angiogenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:618-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galdiero MR Marone GandMantovani A. Cancer inflammation and cytokines. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect Biol 2018;10(8), a028662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.deVisser KE, Eichten A, Coussens LM. Paradoxical roles of the immune system during cancer development. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:24-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493-e503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolan RD, Laird BJA, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response in randomised clinical trials in cancer: A systematic review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2018;132:130-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Templeton AJ, Ace O, McNamara MG, et al. Prognostic role of platelet to lymphocyte ratio in solid tumors: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2014;23:1204-1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Guthrie GJK, Charles KA, Roxburgh CSD, Horgan PG, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. The systemic inflammation-based neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio: Experience in patients with cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013;88:218-230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Basile D, Garattini SK, Corvaja C, et al. The MIMIC Study: Prognostic role and cutoff definition of monocyte‐to‐lymphocyte ratio and lactate dehydrogenase levels in metastatic colorectal cancer. Oncologist. 2020;25:661-668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qi Q, Zhuang L, Shen Y, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting the survival of patients with pancreatic cancer after chemotherapy. Cancer. 2016;122:2158-2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu L, Yu S, Zhuang L, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) predicts prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:34954-34960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li S, Lan X, Gao H, et al. Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI), cancer stem cells and survival of localised gastric adenocarcinoma after curative resection. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2017;143:2455-2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu L, Ma X, Wang L, et al. Prognostic value of a systemic inflammatory response index in metastatic renal cell carcinoma and construction of a predictive model. Oncotarget. 2017;8:52094-52103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng Y, Zhu D, Wu C, et al. A novel systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) for predicting postoperative survival of patients with esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int Immunopharm. 2018;65:503-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y, Jiang W, Xi D, et al. Development and validation of nomogram based on SIRI for predicting the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinomas. J Invest Med. 2019;67:691-698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Jin M, Shao Y, Xu G. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in patients with adenocarcinoma of the oesophagogastric junction: A propensity score-matched analysis. Dis Markers. 2019;2019:4659048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li S, Yang Z, Du H, et al. Novel systemic inflammation response index to predict prognosis after thoracoscopic lung cancer surgery: a propensity score-matching study. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89:E507-E513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zheng Y, Chen Y, Chen J, et al. Combination of systemic inflammation response index and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio as a novel prognostic marker of upper tract urothelial Carcinoma after radical Nephroureterectomy. Front Oncol. 2019;9:914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Y, Liu F, Wang Y. Evidence of the prognostic value of pretreatment systemic inflammation response index in cancer patients: A pooled analysis of 19 cohort studies. Dis Markers. 2020;2020:8854267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin J, Chen L, Chen Q, et al. Prognostic value of preoperative systemic inflammation response index in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma: Propensity score-based analysis. Head Neck; 2020;42(11):3263-3274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun L, Hu W, Liu M, et al. High Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) indicates poor outcome in gallbladder cancer patients with surgical resection: A Single institution experience in China. Cancer Res Treat; 2020;52(4):1199-1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen L, Kong X, Wang Z, Wang X, Fang Y, Wang J. Pretreatment systemic inflammation response index in patients with breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy as a useful prognostic indicator. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:1543-1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chao B, Ju X, Zhang L, Xu X, Zhao Y. A novel prognostic marker Systemic Inflammation Response Index (SIRI) for operable cervical cancer patients. Front Oncol. 2020;10:766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeng X, Liu G, Pan Y, Li Y. Development and validation of immune inflammation-based index for predicting the clinical outcome in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma. J Cell Mol Med. 2020;24:8326-8349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. , The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhou S, Yuan H, Wang J, et al. Prognostic value of systemic inflammatory marker in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma undergoing surgical resection. Future Oncol. 2020;16:559-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.YesilCinkir H, Elboga U. The effect of systemic inflammation indexes and 18FDG PET metabolic parameters on survival in advanced lung adenocarcinoma. Tumori J. 2020;106:312-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.YeşilÇinkir H, ÇolakoğluEr H. The prognostic effects of temporal muscle thickness and inflammatory-nutritional parameters on survival in lung cancer patients with brain metastasis. Turk Onkoloji Dergisi. 2020;35:119-126. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang L, Zhou Y, Xia S, et al. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) before and after surgery in operable breast cancer patients. Cancer Biomarkers. 2020;28:537-547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Topkan E, Mertsoylu H, Kucuk A, et al. Low systemic inflammation response index predicts good prognosis in locally advanced pancreatic carcinoma patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2020;2020:5701949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacheco-Barcia V, MondéjarSolís R, France T, et al. A systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) correlates with survival and predicts oncological outcome for mFOLFIRINOX therapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology. 2020;20:254-264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li S, Xu H, Wang W, et al. The systemic inflammation response index predicts survival and recurrence in patients with resectable pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:3327-3337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hua X, Long Z-Q, Huang X, et al. The preoperative systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) independently predicts survival in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Curr Probl Cancer. 2020;44:100560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu M, Xu Q, Yang S, et al. Pretreatment systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) is an independent predictor of survival in unresectable stage III non-small cell lung cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy: A two-center retrospective study. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gao W, Zhang F, Ma T, Hao J. High preoperative fibrinogen and systemic inflammation response index (F-SIRI) predict unfavorable survival of resectable gastric cancer patients. J Gastr Cancer. 2020;20:202-211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feng Y, Zhang N, Wang S, et al. Systemic inflammation response index is a predictor of poor survival in locally advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma: A propensity score matching study. Front Oncol. 2020;10:575417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Çınkır HY, Doğan İ. Comparison of inflammatory indexes in patients treated with sorafenib in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: A single-center observational study. Erciyes Med J. 2020;42:201-206. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chuang H-C, Tsai M-H, Lin Y-T, et al. The clinical impacts of pretreatment peripheral blood ratio on lymphocytes, monocytes, and neutrophils among patients with laryngeal/hypopharyngeal cancer treated by chemoradiation/radiation. Cancer Manag Res. 2020;12:9013-9021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Z, Wang K, Lu H, et al. Systemic inflammation response index predicts prognosis in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma: A propensity score-matched analysis. Cancer Manag Res. 2019;11:909-919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Topkan E, Kucuk A, Ozdemir Y, et al. Systemic inflammation response index predicts survival outcomes in glioblastoma multiforme patients treated with standard stupp protocol. J Immunol Res. 2020;2020:8628540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kucuk A, Ozkan EE, EskiciOztep S, et al. The influence of systemic inflammation response index on survival outcomes of limited-stage small-cell lung cancer patients treated with concurrent chemoradiotherapy. J Oncol. 2020;2020:8832145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kobayashi H, Okuma T, Okajima K, et al. Systemic inflammation response index (SIRI) as a predictive factor for overall survival in advanced soft tissue sarcoma treated with eribulin. J Orthop Sci. 2020;2658(20):30346-30348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wei L, Xie H, Yan P. Prognostic value of the systemic inflammation response index in human malignancy. Medicine. 2020;99:e23486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Qu X, Tang Y, Hua S. Immunological approaches towards cancer and inflammation: A cross talk. Front Immunol. 2018;9:563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Granot Z, Jablonska J. Distinct functions of neutrophil in cancer and its regulation. Mediat Inflamm. 2015;2015:701067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jablonska E, Puzewska W, Grabowska Z, Jablonski J, Talarek L. VEGF, IL-18 and NO production by neutrophils and their serum levels in patients with oral cavity cancer. Cytokine. 2005;30:93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ding P-R, An X, Zhang R-X, et al. Elevated preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio predicts risk of recurrence following curative resection for stage IIA colon cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2010;25:1427-1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liao R, Jiang N, Tang Z-W, et al. Systemic and intratumoral balances between monocytes/macrophages and lymphocytes predict prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients after surgery. Oncotarget. 2016;7:30951-30961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mantovani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, Allavena P, Sica A. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2006;25:315-322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]