Abstract

Introduction:

The drug pharmacovigilance system in Japan is similar to those in the European Union (EU) and the United States. As a unique Japanese pharmacovigilance program, postmarketing all-case surveillance (PMACS) is required. PMACS plays a key role for postmarketing activities, but there are challenges that place much burden on PMACS conduct. This study investigates the impact of PMACS on postmarketing activities in Japan and proposes its potential improvement. This study also seeks the possibility to expand PMACS beyond Japan.

Materials and Methods:

Reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019 were identified in September 2020 by searching ‘reexamination report’ and ‘201701’ to ‘201912’ on the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency website. The corresponding Package Insert (PI) change orders and premarketing review reports were also identified. Reviewing these regulatory documents allowed for investigation of the PMACS impact on postmarketing activities.

Results:

More than half (57%) of the drugs with PMACS had ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ as a reason for the PMACS requirement. As a safety measure, no PI change orders were imposed on 33% and 28% of drugs with and without PMACS, respectively. The means of the number of PI change orders were 2.23 and 2.14 for drugs with and without PMACS, respectively. There were no reexamination reports mentioning any concerns related to efficacy.

Discussion and Conclusion:

PMACS should not be imposed only because of limited dosing experience in Japan at the premarketing stage. Rather, PMACS should focus on (1) collection of safety data (not efficacy), (2) necessity of distribution control, and/or (3) collection of case details for drugs with a limited treated population. PMACS also has the potential to be utilized in the EU and the United States, as their regulatory frameworks are acceptable for PMACS. Naglazyme (galsulfase) is a case where the PMACS-like studies have been required in each region.

Plain Language Summary

Effectiveness of data collection for all patients who receive a new drug as a safety measure in Japan

Introduction:

In Japan, a drug company is obligated to conduct data collection after a new drug launch as an approval condition. The obligation is a unique Japanese requirement where a company must collect data from all patients receiving the drug in Japan in cooperation with hospitals. This is expected to contribute to intensive data collection and better drug distribution control and could potentially be useful in countries beyond Japan. However, no clear criteria have been established for decision making, despite the significant burden for companies and hospitals. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the impact of the obligation on safety measures and efficacy data collection and propose a potentially improved drug scope to impose the obligation.

Materials and Methods:

Reexamination of reports issued by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency between 2017–2019.

Results:

More than half (57%) of the included drugs had ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ as a reason for the obligation being required. However, regulatory order to change drug label, an action based on safety signal identification, was imposed on 33% and 28% of drugs with and without the obligation, respectively. The means of the number of the label change orders were 2.23 and 2.14 for drugs with and without obligation, respectively. Meanwhile, some drugs were highlighted as potential factors for better application of the obligation.

Conclusion:

According to these results, the obligation should be imposed on a limited number of drugs by focusing not on dosing experience in Japan but on safety (not efficacy) data collection, necessity of distribution control, and/or collection of case details for drugs with a limited treated population. The obligation also has the potential to be utilized in the EU and the United States, as their regulatory frameworks are acceptable for the obligation.

Keywords: Japan, MHLW, package insert, PMDA, postmarketing all-case surveillance, reexamination

Introduction

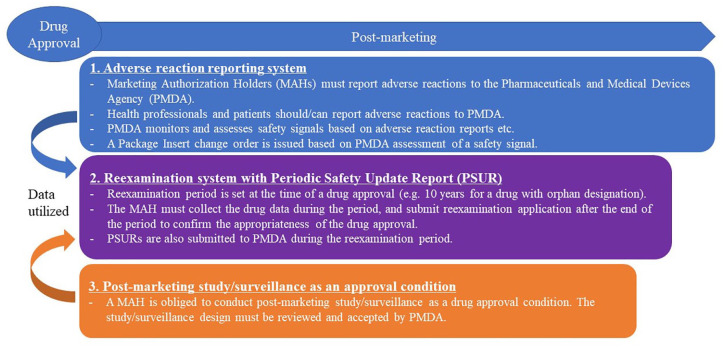

The drug pharmacovigilance system in Japan has three key components: (A) adverse reaction reporting system, (B) reexamination system with a Periodic Safety Update Report (PSUR), and (C) postmarketing study/surveillance. 1 Figure 1 shows an overview of the pharmacovigilance system in Japan.

Figure 1.

Pharmacovigilance system for Drugs in Japan. Adverse reaction reporting system, reexamination system and postmarketing study/surveillance are a key driver for drug pharmacovigilance system in Japan.

The pharmacovigilance system in Japan is similar to those in the European Union (EU) and the United States:

A. Adverse reaction reporting system: The Japanese regulators, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) and the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA), monitor and assess safety signals, and take regulatory measures as needed. Similar systems for adverse reaction reporting have been implemented in the EU (pharmacovigilance system) 2 and the United States (FDA adverse event reporting system). 3

B. Reexamination system with PSUR: The reexamination system in Japan requires a Marketing Authorization Holder (MAH) to collect data for drugs and prepare PSURs for a certain period in their postmarketing stage. At the end of the reexamination period, the Japanese regulators assess the benefit/risk balance of these drugs. Systems to collect postmarketing data, prepare PSURs and assess the benefit/risk balance of an approved drug have been implemented in the EU (PSURs) 4 and the United States (Periodic adverse drug experience reports) 5 as well.

C. Postmarketing study/surveillance: A postmarketing study/surveillance requirement/commitment is imposed on an MAH upon drug approval in Japan. The EU and the United States have similar regulatory systems, Post-Authorisation Safety Studies (PASS) 6 and Postmarketing Requirements and Commitments, 7 respectively.

However, as a unique Japanese pharmacovigilance requirement, the MHLW is authorized to compel an MAH to conduct a postmarketing all-case surveillance (PMACS) as a drug approval condition. PMACS is a type of postmarketing study/surveillance requirement/commitment mentioned above. PMACS is an observational single-arm postmarketing study where an MAH must work with medical institutes to collect data from all the patients received its drug in Japan. PMACS has been implemented for more than 20 years in Japan, 8 and the number of approved drugs with PMACS as an approval condition have increased since 2003. 9

The MHLW explains in the PMACS notification that PMACS is obligatory in the cases where the number of subjects in Japan is low or none in clinical studies for a drug at the premarketing phase or where the drug is likely to cause serious adverse effects. 10 The MHLW expects that PMACS contributes to collecting demographic information on patients in Japan and information on safety and efficacy quickly and without any biases.

MAHs with PMACS experience indicated that PMACS had been useful mainly because (a) case details had been collected even in a limited population, (b) information on off-label use had been obtained, and (c) eligibility of medical institutes, physicians, and patients had been confirmed. 11 Meanwhile, it has been reported that the resource burden for MAH to conduct PMACS was more than 1.5 times (more than 5.0 times in some surveillances) compared with general postmarketing activities, including postmarketing studies. 11 Moreover, PMACS was burdensome for medical institutes due to excessive data collection and entity in a specified form, complicated survey form use, cumbersome contract procedures, and long-term patient follow-up.

Therefore, whether to impose PMACS or not as an approval condition should be carefully decided, taken into account the balance between expected achievement and necessary burden. However, there exist no specific criteria for the decision. Approximately 90% of drugs with PMACS have the reason for its obligation that the number of Japanese patients in the premarketing phase was too small. 11

In summary, PMACS has played a key role in the pharmacovigilance system for drugs in Japan, while the decision whether PMACS is required or not was mainly made by limited dosing experience in Japan, in spite of the high burden of its conduct on MAH and medical institute. This study aimed to investigate the impact of PMACS on safety measures and efficacy data collection in Japan. According to the investigation, we propose a possible improvement of the product scope to impose PMACS as a drug approval condition. The proposal contributes to better pharmacovigilance activities in Japan. This study also considers the potential to introduce PMACS beyond Japan based on the pharmacovigilance systems in Japan, the EU, and the United States.

Materials and methods

Data material sources

There are three types of Japanese regulatory documents used in this study; (A) drug reexamination reports, (B) drug premarketing review reports, and (C) Package Insert (PI) change orders.

A. Drug reexamination report: It is prepared and published by the PMDA once the reexamination period has ended. The report summarizes the information related to safety and efficacy data collected during the specified reexamination period. This includes PMACS data, if applicable.

B. Drug premarketing review report: It is prepared and published by the PMDA once the drug is approved. The report includes information on the approval conditions, including PMACS requirements.

C. PI change order: It is a regulatory notification issued by the MHLW as a safety measure at the postmarketing stage of a drug. PI is equivalent to Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC) in EU and drug label in the United States. The MHLW issues the order if the PMDA identifies a safety signal for the drug and completes the assessment based on accumulated safety data via the adverse reaction reporting system, the PSUR, and postmarketing study/surveillance, including PMACS. An MAH must change the drug PI, according to the notification.

These documents can be found in the PMDA website to search for information on each drug in Japan. 12 In this study, the reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019 were identified in September 2020 by searching for ‘reexamination report’ and ‘201701’ to ‘201912’ on the PMDA website. The corresponding PI change orders and premarketing review reports were also identified on the same website.

The 3-year period is expected to present the trend of deciding whether to impose PMACS after the PMDA started conducting drug premarket reviews. The PMDA was established in April 2004, 13 and the standard duration of the premarketing priority review by the PMDA has been set at 9.0 months. 14 Therefore, new drugs reviewed by the PMDA were launched from 2005. The reexamination period of a drug is up to 10 years. 15 The median assessment duration for reexamination by the PMDA was 15.0 months in Fiscal Year 2018. 14 Hence, the reexamination reports from 2017 are expected to cover the majority of drugs reviewed by the PMDA.

Method to investigate the impact of PMACS

Listing and categorization of reexamination report

Reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019 were listed with issue date, nonproprietary name and brand name. Each report was flagged with the items below by checking premarketing review reports of these drugs:

A. Approval type: Identify whether the approval is for a new drug or label expansion (e.g. new indication).

B. PMACS: Identify whether PMACS was conducted.

C. Reason for PMACS: Categorized the reasons for PMACS with ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’, ‘Further data collection’, ‘Specific safety concern(s)’, or ‘Other’.

Then, the items below were added to the list by investigating PI change orders of each drug:

D. PI change order: Identify whether the MHLW issued order(s) for PI change during the reexamination period.

E. Number of PI change orders: Enter the number of PI change orders for each drug during the reexamination period.

Based on the list with these items above, the reexamination reports were categorized by (A) Approval type, (B) PMACS, and (D) PI change order. In addition, the number of reexamination reports were compared by (C) Reason for PMACS.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug safety measures

The number of PI change orders for each drug were checked. The number is considered a quantitative index for safety measures taken during their reexamination period, based on the description of PI change order in Part C of the section ‘Data material sources’.

Then, drugs with five or more PI change orders issued during their reexamination periods were categorized by therapeutic area of the World Health Organization Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical and Defined Daily Dose (WHO ATC/DDD) index. Five or more PI change orders means that safety measures were taken every 2 years or more frequently on average during reexamination period.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection

The efficacy information in each reexamination report was examined to identify any specific findings related to efficacy.

Identification of distinctive cases in term of PMACS impact

Each reexamination report was reviewed to identify any distinctive drugs/indications where decision with PMACS/no PMACS affected their postmarketing activities.

Results of investigation for the impact of PMACS

Listing and categorization of reexamination report

According to the search using the conditions outlined in the section ‘Data material sources’, 221 reexamination reports were identified in 2017–2019. Two reports for the egg-derived influenza A (H5 N1) vaccine were excluded from this study, because these vaccines had not been marketed during the reexamination period. In addition, a report on sitagliptin was excluded as two similar reports with two different brand names were published due to concurrent selling by two MAHs in Japan. Therefore, 218 reports were included in this study in total. The list of these reports is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019.

| Issue date | Nonproprietary name | Brand name | Approval type New product? |

PMACS? | Reason for PMACS a | PI change order? | Number of PI change orders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 29 March 2018 | Adapalene | Differin Gel | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 2 | 21 December 2017 | Agalsidase Alfa (Genetical Recombination) | REPLAGAL | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 3 | 29 March 2018 | Alendronate Sodium Hydrate | Bonalon Bag for I.V. Infusion | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 4 | 29 March 2018 | Alglucosidase Alfa (Genetical Recombination) | MYOZYME | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 5 | 11 September 2019 | Aliskiren Fumarate | Rasilez Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 6 | 11 September 2019 | Alogliptin Benzoate | NESINA Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 7 | 19 September 2019 | Alogliptin Benzoate Pioglitazone Hydrochloride |

LIOVEL Combination Tablets HD | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 8 | 29 March 2018 | Amiodarone Hydrochloride | Ancaron | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 3 |

| 9 | 29 March 2018 | Ampicillin Sodium, Sulbactam Sodium | UNASYN-S for Intravenous Use | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 10 | 11 September 2019 | Amrubicin Hydrochloride | Calsed for Inj. | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 11 | 20 December 2018 | Aprepitant | EMEND Capsules | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 12 | 29 March 2018 | Aripiprazole | ABILIFY oral solution | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 13 | 27 September 2018 | Aripiprazole | ABILIFY oral solution | No | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 14 | 29 June 2017 | Aspirin, Lansoprazole | TAKELDA Combination Tablets | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 15 | 29 March 2018 | Atazanavir Sulfate | REYATAZ CAPSULES | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 5 |

| 16 | 5 September 2018 | Atomoxetine Hydrochloride | Strattera Capsules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 17 | 5 September 2018 | Azithromycin Hydrate | ZITHROMAC Intravenous use | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 18 | 5 September 2018 | Azithromycin Hydrate | ZITHROMAC Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 19 | 29 March 2018 | Baclofen | GABALON INTRATHECAL INJECTION | Yes | Yes | 3 | No | 0 |

| 20 | 11 September 2019 | Bazedoxifene Acetate | Viviant Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 21 | 27 September 2018 | Bevacizumab (Genetical Recombination) | AVASTIN for Intravenous Infusion | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 3 |

| 22 | 5 December 2018 | Bimatoprost | LUMIGAN OPHTHALMIC SOLUTION | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 23 | 5 June 2019 | Blonanserin | LONASEN Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 24 | 29 March 2018 | Bortezomib | VELCADE Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 3 |

| 25 | 19 December 2019 | Bortezomib | VELCADE Injection | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 26 | 28 September 2017 | Bosentan Hydrate | Tracleer | Yes | Yes | 4 | Yes | 3 |

| 27 | 28 September 2017 | Budesonide | Pulmicort | No | No | NA | Yes | 0 |

| 28 | 29 March 2018 | Budesonide Formoterol Fumarate Hydrate |

Symbicort Turbuhaler | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 29 | 20 December 2018 | Busulfan | Busulfex injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 30 | 29 March 2018 | Calcium Folinate | LEUCOVORIN INJECTION | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 31 | 30 March 2017 | Candesartan Cilexetil Hydrochlorothiazide |

ECARD Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 32 | 20 June 2019 | Capecitabine | XELODA Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 33 | 29 March 2018 | Cetuximab (genetical recombination) | ERBITUX Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 34 | 27 September 2018 | Ciclesonide | Alvesco | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 35 | 28 September 2017 | Ciclosporin | Neoral | No | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 36 | 29 June 2017 | Ciclosporin | PAPILOCK Mini ophthalmic solution | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 37 | 29 March 2018 | Cinacalcet Hydrochloride | REGPARA TABLETS | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 38 | 20 June 2019 | Cladribine | LEUSTATIN Injection | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 39 | 5 December 2018 | Clopidogrel Sulfate | Plavix Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 7 |

| 40 | 19 December 2019 | Clozapine | CLOZARIL Tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 5 |

| 41 | 21 December 2017 | Darbepoetin Alfa (Genetical Recombination) | NESP INJECTION PLASTIC SYRINGE | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 42 | 7 March 2019 | Darbepoetin Alfa (Genetical Recombination) | NESP INJECTION PLASTIC SYRINGE | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 43 | 11 December 2019 | Darunavir Ethanolate | PREZISTANAIVE Tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 6 |

| 44 | 5 June 2019 | Deferasirox | Exjade | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 45 | 20 December 2018 | Dexamethasone cipecilate | Erizas Capsule for Nasal spray | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 46 | 28 June 2018 | Dexmedetomidine Hydrochloride | Precedex Injections | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 47 | 5 June 2019 | Diarsenic trioxide | Trisenox Injection | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 48 | 29 March 2018 | Diazoxide | DIAZOXIDE Capsules | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 49 | 29 March 2018 | Dienogest | DINAGEST Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 50 | 11 September 2019 | Diquafosol Sodium | DIQUAS ophthalmic solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 51 | 21 December 2017 | Doripenem Hydrate | FINIBAX | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 52 | 21 December 2017 | Doripenem Hydrate | FINIBAX | No | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 53 | 21 December 2017 | Dorzolamide Hydrochloride, Timolol Maleate | COSOPT ophthalmic solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 54 | 27 September 2018 | Doxorubicin Hydrochloride, Doxorubicin | DOXIL Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 55 | 20 December 2018 | Dutasteride | Avolve Capsules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 56 | 29 March 2018 | Enoxaparin Sodium | Clexane S.C. Injection | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 57 | 5 December 2018 | Entacapone | Comtan Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 58 | 29 March 2018 | Entecavir Hydrate | Baraclude Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 59 | 21 December 2017 | Eplerenone | Selara Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 60 | 14 March 2019 | Erlotinib Hydrochloride | TARCEVA Tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 61 | 29 March 2018 | Estradiol | Julina tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 62 | 29 March 2018 | Estradiol Levonorgestrel |

Wellnara combination tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 63 | 30 March 2017 | Etanercept (genetical recombination) | ENBREL 10 mg for S.C. Injection | No | Yes | 3 | Yes | 5 |

| 64 | 28 September 2017 | Etanercept (genetical recombination) | ENBREL 10 mg for S.C. Injection | Yes | Yes | 3 | Yes | 5 |

| 65 | 14 March 2019 | Everolimus | AFINITOR tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 2 |

| 66 | 28 September 2017 | Ezetimibe | Zetia | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 67 | 21 December 2017 | Famciclovir | Famvir Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 68 | 29 March 2018 | Famciclovir | Famvir Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 69 | 29 June 2017 | Fentanyl | OneDuro Patch | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 70 | 14 March 2019 | Fentanyl | OneDuro Patch | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 71 | 20 December 2018 | Fentanyl Citrate | Abstral Sublingual Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 72 | 5 December 2018 | Fentanyl Citrate | E-fen buccal tablet | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 73 | 6 June 2018 | Fentanyl Citrate | FENTOS Tapes | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 74 | 11 September 2019 | Fentanyl Citrate | FENTOS Tapes | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 75 | 11 September 2019 | Fexofenadine Hydrochloride | Allegra Dry Syrup | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 76 | 7 March 2019 | fibrinogen combined drug | TachoSil Tissue Sealing sheet | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 77 | 7 March 2019 | Fludarabine Phosphate | Fludara | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 78 | 5 December 2018 | Fluticasone Furoate | Allermist 27.5 μg metered Nasal Spray | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 79 | 11 September 2019 | Fluticasone Furoate | Allermist 27.5 μg metered Nasal Spray | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 80 | 30 March 2017 | Follitropin alfa (genetical recombination) | Gonalef | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 81 | 29 March 2018 | Follitropin alfa (genetical recombination) | Gonalef | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 3 |

| 82 | 21 December 2017 | Formoterol Fumarate Hydrate | Oxis | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 0 |

| 83 | 30 March 2017 | Gabapentin | GABAPEN Syrup | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 84 | 30 March 2017 | Gadoxetate Sodium | EOB・Primovist Inj. Syringe | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 85 | 19 September 2019 | Galsulfase (Genetical Recombination) | Naglazyme | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 86 | 21 December 2017 | Ganirelix Acetate | GANIREST Subcutaneous | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 87 | 30 March 2017 | Garenoxacin Mesilate Hydrate | Geninax Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 9 |

| 88 | 29 March 2018 | Gemcitabine Hydrochloride | Gemzar Injection | No | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 89 | 6 June 2018 | Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin (Genetical Recombination) | MYLOTARG Injection | No | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 90 | 29 March 2018 | Human activated protein C, freeze-dried concentrated | Anact C | No | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 91 | 21 December 2017 | Human Chorionic Gonadotrophin | GONATROPIN FOR INJECTION | No | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 92 | 20 June 2019 | Ibritumomab Tiuxetan (genetical recombination) | ZEVALIN yttrium injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 93 | 14 March 2019 | Idursulfase (Genetical Recombination) | ELAPRASE | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 94 | 11 December 2019 | Imatinib Mesilate | Glivec Tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 7 |

| 95 | 19 December 2019 | Imatinib Mesilate | Glivec Tablets | No | Yes | 2 | Yes | 7 |

| 96 | 30 March 2017 | Imiquimod | BESELNA CREAM | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 97 | 29 June 2017 | Imiquimod | BESELNA CREAM | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 98 | 21 December 2017 | Infliximab (genetical recombination) | REMICADE for I.V. Infusion | No | No | NA | Yes | 9 |

| 99 | 27 September 2018 | Infliximab (genetical recombination) | REMICADE for I.V. Infusion | No | Yes | 1 | Yes | 9 |

| 100 | 30 March 2017 | Influenza HA vaccine | INFLUENZA HA VACCINE "BIKEN" | No | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 101 | 30 March 2017 | Influenza HA vaccine | INFLUENZA HA VACCINE "SEIKEN" | No | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 102 | 30 March 2017 | Influenza HA vaccine | INFLUENZA HA VACCINE "DAIICHI SANKYO" | No | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 103 | 29 June 2017 | Influenza HA vaccine | INFLUENZA HA VACCINE "KMB" | No | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 104 | 21 December 2017 | Insulin Detemir (Genetical Recombination) | Levemir InnoLet | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 105 | 28 June 2018 | Insulin Glulisine (Genetical Recombination) | Apidra Cart S.C. Injection | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 106 | 29 March 2018 | Interferon Beta | FERON | No | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 107 | 29 March 2018 | Interferon Beta-1a (Genetical Recombination) | AVONEX IM Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 108 | 29 March 2018 | Irbesartan | AVAPRO Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 109 | 29 March 2018 | Irbesartan, Amlodipine Besilate | AIMIX | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 110 | 29 June 2017 | Itraconazole | ITRIZOLE Oral Solution | No | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 111 | 27 September 2018 | Japanese encephalitis vaccine | JEBIK V | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 112 | 28 June 2018 | Lamotrigine | Lamictal Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 113 | 21 December 2017 | Lanthanum Carbonate Hydrate | Fosrenol Chewable Tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 114 | 19 December 2019 | Lapatinib Tosilate Hydrate | Tykerb Tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 115 | 21 December 2017 | Laronidase (Genetical Recombination) | ALDURAZYME | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 116 | 21 December 2017 | Latanoprost Timolol Maleate |

Xalacom Combination Eye Drops | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 117 | 29 March 2018 | Levobupivacaine Hydrochloride, levobupivacaine | POPSCAINE 0.25% inj. | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 118 | 29 March 2018 | Levobupivacaine Hydrochloride, levobupivacaine | POPSCAINE 0.25% inj. | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 119 | 21 December 2017 | Levofloxacin Hydrate | CRAVIT FINE GRANULES | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 120 | 29 March 2018 | Levofloxacin Hydrate | CRAVIT INTRAVENOUS DRIP INFUSION | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 121 | 5 September 2018 | Lidocaine | Penles Tape | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 122 | 20 June 2019 | Liraglutide (Genetical Recombination) | Victoza Subcutaneous Injection | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 123 | 7 March 2019 | Meropenem Hydrate | Meropen | No | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 124 | 11 December 2019 | Methylphenidate Hydrochloride | Concerta Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 125 | 29 March 2018 | Miglitol | SEIBULE | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 126 | 7 March 2019 | Miriplatin Hydrate | MIRIPLA | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 127 | 5 December 2018 | Mirtazapine | REFLEX TABLETS | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 128 | 6 June 2018 | Modafinil | MODIODAL Tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 129 | 11 September 2019 | Modafinil | MODIODAL Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 130 | 6 June 2018 | Mometasone Furoate | ASMANEX Twisthaler | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 131 | 29 March 2018 | Mometasone Furoate Hydrate | NASONEX Nasal 50 μg 112sprays | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 132 | 29 March 2018 | Monteplase (genetical recombination) | Cleactor | No | Yes | 2 | Yes | 1 |

| 133 | 21 December 2017 | Moxifloxacin Hydrochloride | VEGAMOX Ophthalmic Solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 134 | 29 March 2018 | Moxifloxacin Hydrochloride | Avelox | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 135 | 29 March 2018 | Mozavaptan Hydrochloride | Physuline tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 136 | 5 December 2018 | Nalfurafine Hydrochloride | REMITCH CAPSULES | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 137 | 29 June 2017 | Naratriptan Hydrochloride | Amerge Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 138 | 20 June 2019 | Nelarabine | ARRANON G Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 139 | 7 March 2019 | Norethisterone Ethinylestradiol |

LUNABELL tablets ULD | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 140 | 11 December 2019 | Olanzapine | Zyprexa tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 141 | 5 December 2018 | Olanzapine | Zyprexa Zydis tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 7 |

| 142 | 30 March 2017 | Olopatadine Hydrochloride | ALLELOCK Granules | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 143 | 6 June 2018 | Oseltamivir Phosphate | TAMIFLU Capsules | No | No | NA | Yes | 6 |

| 144 | 29 March 2018 | Oxaliplatin | ELPLAT I.V. INFUSION SOLUTION | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 4 |

| 145 | 20 December 2018 | Oxycodone Hydrochloride Hydrate | OXIFAST | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 146 | 5 December 2018 | Paclitaxel | Abraxane I.V. Infusion | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 147 | 19 December 2019 | Paliperidone | Invega Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 148 | 11 December 2019 | Palivizumab (Genetical Recombination) | Synagis Solution for intramuscular Administration | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 149 | 30 March 2017 | Pamidronate Disodium Hydrate | Aredia for I.V. infusion | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 150 | 20 June 2019 | Panitumumab (Genetical Recombination) | Vectibix | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 4 |

| 151 | 29 March 2018 | Peginterferon Alfa-2a (Genetical Recombination) | PEGASYS for Subcutaneous Injection | No | No | NA | Yes | 8 |

| 152 | 29 March 2018 | Peginterferon Alfa-2a (Genetical Recombination) | PEGASYS for Subcutaneous Injection | No | No | NA | Yes | 8 |

| 153 | 29 March 2018 | Peginterferon Alfa-2b (Genetical Recombination) | PEGINTRON Powder for Injection | No | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 154 | 21 December 2017 | Pegvisomant (Genetical Recombination) | SOMAVERT for s.c. Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 155 | 29 March 2018 | Pemetrexed Sodium Hydrate | Alimta Injection | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 2 |

| 156 | 11 September 2019 | Peramivir Hydrate | RAPIACTA for Intravenous Drip Infusion | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 157 | 28 September 2017 | Perflubutane | SONAZOID FOR INJECTION | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 158 | 21 December 2017 | Phenobarbital Sodium | NOBELBAR 250mg for Injection | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 159 | 20 June 2019 | Phenothrin | SUMITHRIN Lotion | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 160 | 30 March 2017 | Pioglitazone Hydrochloride Glimepiride |

SONIAS Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 161 | 30 March 2017 | Pioglitazone Hydrochloride Metformin Hydrochloride |

METACT Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 162 | 19 December 2019 | Pirfenidone | Pirespa | Yes | Yes | 4 | Yes | 1 |

| 163 | 29 March 2018 | Polaprezinc | Promac granules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 164 | 29 June 2017 | Pranlukast Hydrate | ONON drysyrup | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 165 | 20 June 2019 | Pregabalin | LYRICA Capsules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 166 | 19 December 2019 | Raltegravir potassium | ISENTRESS Tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 3 |

| 167 | 20 June 2019 | Ramelteon | Rozerem Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 168 | 7 March 2019 | Rasburicase (Genetical Recombination) | RASURITEK | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 169 | 7 March 2019 | Rebamipide | Mucosta tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 170 | 29 March 2018 | Rifabutin | MYCOBUTIN Capsules | No | Yes | 2 | No | 0 |

| 171 | 29 March 2018 | Risperidone | RISPERDAL Consta Intramuscular Injection | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 172 | 29 March 2018 | Rocuronium Bromide | ESLAX Intravenous | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 173 | 21 December 2017 | Ropinirole Hydrochloride | ReQuip CR Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 174 | 29 June 2017 | Rosuvastatin Calcium | CRESTOR Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 175 | 19 December 2019 | Sapropterin Hydrochloride | BIOPTEN GRANULES | No | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 176 | 11 September 2019 | Sildenafil Citrate | Revatio Tablets | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 177 | 28 September 2017 | Sitafloxacin Hydrate | GRACEVIT TABLETS | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 178 | 14 March 2019 | Sitagliptin Phosphate Hydrate | GLACTIV Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 8 |

| 179 | 19 December 2019 | Sodium Hyaluronate Crosslinked Polymer, Sodium Hyaluronate Crosslinked Polymer Crosslinked with vinylsulfone | SYNVISC | Yes | No | NA | No | 1 |

| 180 | 28 June 2018 | Sodium Risedronate Hydrate | Actonel Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 181 | 14 March 2019 | Sorafenib Tosilate | Nexavar tablets | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 8 |

| 182 | 27 September 2018 | Strontium(89Sr)chloride | METASTRON | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 183 | 7 March 2019 | Sugammadex Sodium | BRIDION Intravenous | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 184 | 21 December 2017 | Sunitinib Malate | SUTENT Capsule | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 5 |

| 185 | 30 March 2017 | Tacrolimus Hydrate | Prograf Capsules | No | No | NA | Yes | 8 |

| 186 | 11 September 2019 | Tacrolimus Hydrate | TALYMUS OPHTHALMIC SUSPENSION | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 1 |

| 187 | 19 December 2019 | Tacrolimus Hydrate | Prograf Capsules | No | Yes | 4 | Yes | 8 |

| 188 | 30 March 2017 | Tadalafil | Cialis Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 189 | 11 September 2019 | Tadalafil | Zalutia Tablets | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 190 | 29 March 2018 | Tafluprost | TAPROS ophthalmic solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 191 | 14 March 2019 | Talaporfin Sodium | LASERPHYRIN 100 mg FOR INJECTION | Yes | Yes | 2 | No | 0 |

| 192 | 21 December 2017 | Tazobactam, Piperacillin Hydrate | ZOSYN | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 193 | 5 September 2018 | Tazobactam, Piperacillin Hydrate | ZOSYN | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 194 | 5 December 2018 | Tebipenem Pivoxil | ORAPENEM FINE GRANULES | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 195 | 29 March 2018 | Temozolomide | TEMODAL Capsules | Yes | Yes | 1 | Yes | 4 |

| 196 | 19 September 2019 | Temsirolimus | TORISEL Injection | Yes | Yes | 2 | Yes | 1 |

| 197 | 20 December 2018 | Teriparatide Acetate | Teribone Injection | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 198 | 11 December 2019 | Teriparatide (Genetical Recombination) | Forteo Subcutaneous injection kits | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 199 | 21 December 2017 | Thrombomodulin alfa (genetical recombination) | Recomodulin lnj. | Yes | Yes | 4 | No | 0 |

| 200 | 21 December 2017 | Tiotropium Bromide Hydrate, Tiotropium Bromide | Spiriva Inhalation Capsules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 201 | 19 September 2019 | Tobramycin | TOBI Inhalation solution | Yes | Yes | 1 | No | 0 |

| 202 | 21 December 2017 | Topiramate | Topina Fine Granules | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 203 | 14 March 2019 | Topiramate | Topina Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 204 | 30 March 2017 | Tosufloxacin Tosilate Hydrate | OZEX | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 205 | 29 March 2018 | Tramadol Hydrochloride | Tramal OD Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 206 | 5 September 2018 | Tramadol Hydrochloride | Tramal OD Tablets | No | No | NA | Yes | 3 |

| 207 | 27 September 2018 | Tramadol Hydrochloride Acetaminophen |

TRAMCET Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 208 | 6 June 2018 | Trastuzumab (Genetical Recombination) | HERCEPTIN for Intravenous Infusion | Yes | Yes | 4 | No | 0 |

| 209 | 21 December 2017 | Travoprost | TRAVATANZ Ophthalmic Solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 210 | 21 December 2017 | Travoprost, Timolol Maleate | DUOTRAV Combination Ophthalmic Solution | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 211 | 14 March 2019 | Triamcinolone Acetonide | MaQaid OPHTHALMIC INJECTION | No | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 212 | 14 March 2019 | Triamcinolone Acetonide | MaQaid OPHTHALMIC INJECTION | Yes | No | NA | No | 0 |

| 213 | 20 December 2018 | Valsartan Amlodipine Besilate |

EXFORGE Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 4 |

| 214 | 30 March 2017 | Valsartan Hydrochlorothiazide |

Co-DIO Combination Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 215 | 11 September 2019 | Valsartan, Cilnidipine | ATEDIO Combination Tab | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 1 |

| 216 | 5 September 2018 | Varenicline Tartrate | CHAMPIX Tablets | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 5 |

| 217 | 30 March 2017 | Voglibose | BASEN | Yes | No | NA | Yes | 2 |

| 218 | 11 September 2019 | Zoledronic Acid Hydrate | ZOMETA for I.V. infusion | Yes | Yes | 3 | Yes | 8 |

NA, not applicable; PI, package insert; PMACS, postmarketing all-case surveillance.

The numbers in this column mean 1: Limited dosing experience in Japan; 2: Further data collection; 3: Specific safety concerns; 4: Other.

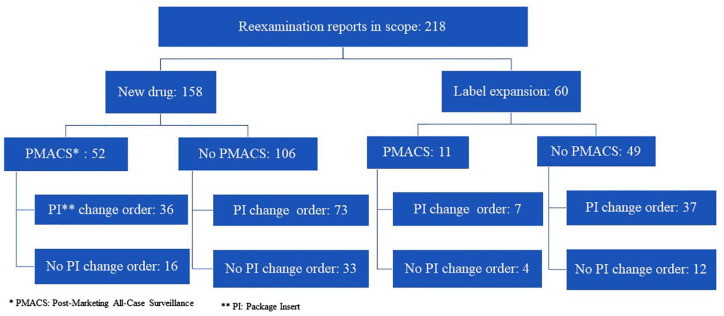

Figure 2 shows the categorization of the 218 reexamination reports. Among them, 158 and 60 cases were for new drug and label expansion, respectively. PMACS was obligatory in 52 of the 158 cases with new drug approval. Among the 52 cases, one or more PI change orders were issued in 36 cases (69%) during the reexamination period. Meanwhile, there were 106 cases with new drug approvals where PMACS was not obligatory. Among the 106 cases, one or more PI change orders were issued in 73 cases (69%) during their reexamination periods.

Figure 2.

Reexamination report categorization. The identified 218 reexamination reports in 2017–2019 were categorized by PMACS requirement and PI change order, and the breakdown number of reexamination reports in each category is shown.

PMACS was obligatory in 11 of the 60 cases with label expansion. One or more PI change orders were issued in 7 (64%) of the 11 cases during their reexamination periods. Meanwhile, there were 49 cases with label expansion where PMACS was not obligatory. Among the 49 cases, one or more PI change orders were issued in 37 cases (76%) during the reexamination period.

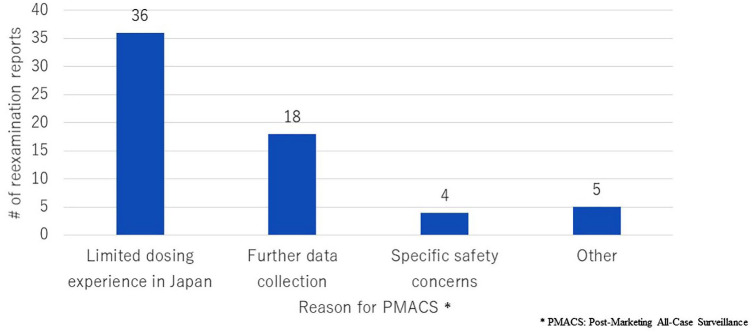

Figure 3 compares the number of reexamination reports by reason for PMACS. More than half (57%) of the cases with PMACS had ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ as a reason for PMACS obligation. PMACS was conducted voluntarily in four out of five cases with the reason ‘Other’. The fifth case was Tracleer (bosentan hydrate) (Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Japan), for which PMACS was required because the indications approved were wider than those targeted in premarketing clinical studies.

Figure 3.

Number of reexamination reports by reason for PMACS. The number of reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019 was compared by reason for PMACS.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug safety measures

The number of PI change orders was identified for 198 drugs, as two reexamination reports were issued for 20 drugs, since these reports targeted different indications. As a PI change order is issued for the relevant drug, not for each indication, these 20 reports were excluded from the calculated number to avoid duplicate counting. Table 2 summarizes these results. No PI change orders were issued for 33% and 29% of drugs with and without PMACS, respectively, during their reexamination periods. The means of the number of PI change orders were 2.23 and 2.15 for drugs with PMACS and without PMACS, respectively.

Table 2.

Number of PI change orders.

| PMACS | No PMACS | |

|---|---|---|

| Total number of drugs reported | 61 | 137 |

| Number of drugs with no PI change order | 20 (33%) |

40 (29%) |

| Mean of PI change orders | 2.23 | 2.15 |

| Maximum number of PI change orders | 9 | 9 |

The number of PI change orders for drugs with reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019 was compared based on mandatory status of PMACS.

PI, package insert; PMACS, postmarketing all-case surveillance.

Table 3 shows the number of drugs with five or more PI change orders issued during their reexamination periods by WHO ATC/DDD index. Totally, five or more PI change orders were issued in 10 out of 61 (16%) drugs with PMACS and 20 out of 137 (15%) drugs without PMACS. The highest number of the drugs fell into ‘anti-infectives for systemic use’ (11 drugs). However, the number was obtained due to the PI change order, not for a specific product, but for all the influenza related products in Japan with four influenza vaccines and Tamiflu (oseltamivir phosphate) (Chugai Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Japan). Once the order is excluded, ‘anti-neoplastic and immunomodulating agents’ have the highest number (eight drugs).

Table 3.

Number of drugs with five or more PI change orders by WHO ATC/DDD index.

| WHO ATC/DDD index | Number of drugs | |

|---|---|---|

| PMACS | No PMACS | |

| Antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents | 6 | 2 |

| Anti-infectives for systemic use | 2 | 9 |

| Nervous system | 1 | 5 |

| Musculo-skeletal system | 1 | 1 |

| Alimentary tract metabolism | 0 | 1 |

| Blood and blood forming organs | 0 | 1 |

| Cardiovascular system | 0 | 1 |

Among drugs with reexamination reports issued from 2017 to 2019, those with five or more PI change orders during their reexamination period were accumulated, categorized by WHO ATC/DDD index and compared based on mandatory status of PMAC.

PMACS, postmarketing all-case surveillance; WHO ATC/DDD, World Health Organization anatomical therapeutic chemical and defined daily dose.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection

There were no reexamination reports mentioning any outstanding findings related to drug efficacy.

Identification of distinctive cases in term of PMACS impact

Four drugs were identified by review of each reexamination report in terms of decision with and without PMACS which affected postmarketing activities; Nexavar (sorafenib tosilate) (Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Japan), Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan), Lamictal (lamotrigine) (GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Japan) and Concerta (methylphenidate hydrochloride) (Janssen Pharmaceutical K. K., Japan).

Discussion

Listing and categorization of reexamination report

As Figure 3 shows that PMACS was obligatory in more than half (57%) of the cases due to ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’, the MHLW has made a decision of PMACS/no PMACS, taking much into account dosing experience in Japan. However, ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ is not a suitable decision criterion, as no difference of safety measures or efficacy data collection was observed between the cases with PMACS and no PMACS in this study.

Another finding is that dosing experience with different indications in Japan is considered when deciding on the PMACS obligation. PMACS was obligatory for 52/158 cases in new drugs versus 11/60 cases in label expansions.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug safety measures

As shown in Table 2, similar percentages of drugs with no PI change were observed (33% and 29% of drugs with and without PMACS, respectively). In addition, the mean number of PI change orders was similar between drugs with PMACS and no PMACS. These results indicate that postmarketing activities achieved safety measures to a similar degree between with and without PMACS. Therefore, the decision of PMACS/no PMACS based on mainly ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ contributed little to safety measures while the PMACS burden occurred.

Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection

As mentioned in the section ‘Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection’, no outstanding efficacy findings were observed in reexamination process, regardless of with and without PMACS. This means that decision of PMACS/no PMACS have little impact on efficacy data collection, even though the PMACS was required mainly for the puropse of ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ or ‘Further data collection’. This point is also supported, considering that, as mentioned in the section ‘Introduction’, PMACS is usually a single-arm observational study where findings for efficacy are likely limited. In fact, postauthorization efficacy studies are separated from PASSs and clearly imposed, if needed, in the EU. 16

Identification of distinctive cases in term of PMACS impact

No distinctive cases were identified from the viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection, as there were no findings in any reexamination reports as mentioned in the section ‘Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection’. The four drugs shown in the section ‘Identification of distinctive cases in term of PMACS impact’ were categorized as follows in terms of PMACS decision and safety measures taken:

A. Drug with PMACS, resulting in outstanding safety measures: Nexavar (sorafenib tosilate) (Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Japan) and Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan)

B. Drug without PMACS, resulting in outstanding safety measures: Lamictal (lamotrigine) (GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Japan)

C. Drug with PMACS, resulting in failed safety measures: None

D. Drug without PMACS, resulting in failed safety measures: Concerta (methylphenidate hydrochloride) (Janssen Pharmaceutical K. K., Japan)

Details of each case are explained below:

A. Nexavar (sorafenib tosilate) (Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Japan), an anticancer drug, could be considered one of the best examples where PMACS worked well. When it was approved, data from 171 Japanese patients had been accumulated in premarketing clinical studies. 15 The number of Japanese patients treated at premarketing stage was higher than the number of Japanese patients influencing the obligatory decision with PMACS (100 patients). 9 That is, the MAH would not have been obligated to conduct PMACS in term of limited dosing experience in Japan. However, PMACS was obligatory. This was because the drug was the first molecular-targeted drug in the field of urological malignancies in Japan and because a variety of adverse drug reactions were observed during premarketing clinical studies. 15 As a result, eight PI change orders were issued during the reexamination period, including two urgent safety information letters. 17 One of the letters was related to interstitial pneumonia, an unexpected adverse drug reaction that had not been observed in the premarketing phase. The other was related to liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy. Liver failure was one of the safety notes highlighted by PMACS, according to data from premarketing clinical studies. PMACS contributed to the detection of both known and unknown safety concerns for this drug, regardless of dosing experience in Japanese patients.

Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan) is also considered appropriate to apply PMACS. Only seven patients were treated with this drug for more than a 10-year PMACS period. 18 No new important safety concerns were observed, and efficacy information was limited because of the low number of patients. However, data from all patients were intensively collected for a long period under PMACS. The data of each case could help the understanding of its use.

B. Lamictal (lamotrigine) (GlaxoSmithKline K.K., Japan) supports the idea that postmarketing activities without PMACS are effective. For this drug, the urgent safety signal regarding serious skin disorders and the underlying cause were identified without PMACS. Accordingly, some safety actions, including issuing an urgent safety information letter, 17 were taken to ensure dose compliance at the escalation phase and quick discontinuation of drug dosing if a skin disorder was observed. As a result, the number of cases of inappropriate use decreased.

C. There was no case identified in this category. In general, PMACS is a good tool to collect safety data comprehensively, as all patients treated with the targeted drug are captured.

D. Concerta (methylphenidate hydrochloride) (Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Japan) is considered a case where PMACS should have been required since its launch. The drug was not required to conduct PMACS as an approval condition, while supply restrictions, including prescribing physician registration, needed to be introduced. As a result, more than 500 prescriptions were issued by ineligible physicians during its reexamination period; the drug was dispensed based on 75 inappropriate prescriptions; and no serious adverse drug reactions due to the inappropriate prescriptions were observed. 19 Then, according to the reexamination assessment by the PMDA, further measures were required for its appropriate use, including the introduction of a system to register all patients to be prescribed.

Proposal on PMACS application

As discussed in sections ‘Listing and categorization of reexamination report,’ ‘Assessment from viewpoint of drug safety measures’, and ‘Assessment from viewpoint of drug efficacy data collection’, the decision of PMACS/no PMACS based on mainly ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’ contributed little to safety measures or efficacy data collection, in spite of high PMACS burden. Meanwhile, the four distinctive cases are identified in terms of PMACS decision and safety measures taken. Based on these points, the proposed product scope to impose PMACS is as follows:

A. Drugs related to Designated Diseases in Article 67 of the Act on Securing Quality, Efficacy and Safety of Products Including Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices (PMDA Act) 20 : currently, cancer, sarcoma, and leukemia are specified as a designated disease according to the article referring to drugs ‘for which use not under the guidance of physicians or dentists is highly likely to cause hazards.’

Nexavar (sorafenib tosilate) (Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Japan) supports this proposal. This case represents a successful application of mandatory PMACS, even though dosing experience in Japanese patients at the premarketing stage was available to some extent. In addition, as highlighted in Table 3, ‘antineoplastic and immunomodulating agents’ had the highest number (eight) of drugs with five or more PI change orders issued during their reexamination periods. This indicates that intensive safety information collection under PMACS contributed to advancing the appropriate use of drugs in the therapeutic area.

B. Drugs with special distribution restrictions: Concerta (methylphenidate hydrochloride) (Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., Japan) supports this proposal. For example, the distribution of narcotics must be strictly managed in Japan to avoid drug abuse or dependence. For such a drug, PMACS would allow tracking appropriate drug use and collecting safety and efficacy data efficiently, because distribution restriction and data collection could be pursued simultaneously.

C. ‘Ultra-orphan’ drugs: There is no legal definition of ‘Ultra-orphan’ drugs in Japan and other countries/regions such as in the EU and the United States, but the Scottish Medicine Consortium has set a definition that considers the prevalence (1 in 50,000 or less) and conditions, including chronicity, severe disablement, and necessitating highly specialized management. 21 Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan) supports this proposal. For such a drug, PMACS could contribute to closely monitoring every patient and quickly collecting and sharing detailed information on each dosing experience for appropriate drug. Furthermore, the burden for MAHs and medical institutes to conduct PMACS could be reasonable because of the low number of patients to be followed up.

Finally, PMACS could be utilized not only in Japan but also in other regions/countries such as the EU and the United States. As described in the section ‘Introduction’, both regulators have a similar pharmacovigilance system similar to that in Japan with the authority to impose MAHs to conduct a postmarketing study. Thus, these systems already have the regulatory framework to introduce PMACS, enabling proposition by regulators and MAHs alike, if preferable.

For example, Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan) has been approved not only in Japan but also in the EU and the United States, and clinical surveillance programs have been conducted as a condition of its authorization/approval in the EU and the United States.22,23 One of the objectives of the programs was to collect clinical data from as many treated patients as possible. In this case, the programs could be appropriately conducted as PMACS, similar to that in Japan.

In addition, Nexavar (sorafenib tosilate) (Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd, Japan), which had PMACS obligation and resulted in outstanding safety measures, indicated that PMACS can be effective not only in Japan but also other countries. The reasons to decide PMACS obligation were not Japan-specific ones (e.g. ‘Limited dosing experience in Japan’).

Conclusion

This study revealed that the appropriate safety action (issuing PI change order) was taken, regardless of the mandatory status of PMACS and the degree of dosing experience in Japanese patients at the premarketing stage. Meanwhile, it also identified some drugs where PMACS worked well or could be effective. Considering the significant burden PMACS exerts on MAHs and medical institutes, in addition to these study findings, the product scope to impose PMACS should be improved. Particularly, PMACS should not be imposed only because of limited dosing experience in Japan at the premarketing stage. Rather, PMACS requirement should focus on (1) collection of safety data (not efficacy), (2) necessity of distribution control, and/or (3) collection of case details for drugs with a limited treated population. Finally, PMACS has the potential to be utilized not only in Japan but also in other countries/regions, such as the EU and the United States. Both regulators have similar pharmacovigilance systems to Japan, which means that they already have the regulatory framework to introduce PMACS. Both these regulators and MAHs could propose PMACS, if preferable. This study demonstrated Naglazyme (galsulfase) (BioMarin Pharmaceutical Japan K.K., Japan) as a case where PMACS or clinical surveillance programs like PMACS have been required in each region/country.

Limitations

This study targeted the reexamination reports issued in 2017–2019 to determine the implementation of PMACS after the PMDA was established, as mentioned in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section. The concept of safety measures has advanced in Japan since the establishment of the PMDA, including the introduction of the Risk Management Plan in 2013. 24 Therefore, the latest trends in the implementation of PMACS could be observed once further investigation is conducted after the relevant reexamination reports are published.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Both the authors made substantial contributions to designing the study, collecting data, examining the relevant information, and drafting and reviewing this paper. Dr Masamune has taken the final responsibility to submit this paper in this journal.

Conflict of interest statement: Hideyuki Kondo is a employee of Novartis Pharma K.K.

Ethical approval/patient consent: Not applicable, as this study did not recruit any patients or provide intervention to them. The study was conducted based on public data.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Hideyuki Kondo  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8763-4262

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8763-4262

Contributor Information

Hideyuki Kondo, Cooperative Major in Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Joint Graduate School of Tokyo Women’s Medical University and Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan.

Ken Masamune, Cooperative Major in Advanced Biomedical Sciences, Joint Graduate School of Tokyo Women’s Medical University and Waseda University, Tokyo, Japan.

References

- 1.. Drug safety measures presented by MHLW (in Japanese), https://www.mhlw.go.jp/shingi/2009/08/dl/s0821-4d.pdf (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 2.. Pharmacovigilance: overview, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/overview/pharmacovigilance-overview (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 3.. Postmarketing surveillance programs, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/surveillance/postmarketing-surveillance-programs (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 4.. Periodic safety update reports (PSURs), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance/periodic-safety-update-reports-psurs (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 5.. 21 CFR 314.80(c)(2), CFR – Code of Federal Regulations Title 21, https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfcfr/cfrsearch.cfm?fr=314.80 (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 6.. Post-authorisation safety studies (PASS), https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/pharmacovigilance/post-authorisation-safety-studies-pass-0 (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 7.. Postmarketing requirements and commitments: introduction, https://www.fda.gov/drugs/guidance-compliance-regulatory-information/postmarket-requirements-and-commitments (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 8.. Post-marketing surveillance and safety management. Chapter 4, regulatory affairs in Japan (in Japanese), http://www.jpma.or.jp/about/issue/gratis/pdf/17yakuji_ch04.pdf (accessed 13 September 2020).

- 9.. Mori E, Kaneko M, Narukawa M. The current status of all-case surveillance study in Japan and factors influencing the judgement of its necessity. Jpn J Clin Pharmacol Ther 2015; 46(4): 185–189 (in Japanese), https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jscpt/46/4/46_185/_pdf/ (accessed 1 September 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.. QAs related to post-marketing all-case surveillance for drugs (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000231052.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 11.. Research on the situation and implications of the post-marketing all-case surveillance study in Japan (in Japanese),https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/rsmp/4/3/4_199/_pdf/-char/ja (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 12.. PMDA website for search of drugs (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuSearch/ (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 13.. History, https://www.pmda.go.jp/english/about-pmda/outline/0002.html (accessed 13 September 2020).

- 14.. PMDA performance report in Fiscal Year 2018 (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000233399.pdf (accessed 13 September 2020).

- 15.. Post-marketing all-case surveillance – current status and future in Japan. PMDA presentation material in Anti-Tumor Drug Development Forum in June 2012 (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000164164.pdf (accessed 13 September 2020).

- 16.. Post-authorisation efficacy studies: questions and answers, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/post-authorisation/post-authorisation-efficacy-studies-questions-answers (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 17.. Urgent safety information (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/safety/info-services/drugs/calling-attention/esc-rsc/0001.html (accessed 13 September 2020).

- 18.. Re-examination report for Naglazyme issued on August 2, 2019 (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs_reexam/2019/P20191001003/641173000_22000AMX01523_A100_1.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 19.. Reexamination report for Concerta issued on October 7, 2019 (in Japanese), https://www.pmda.go.jp/drugs_reexam/2019/P20191114002/800155000_21900AMX01770_A100_1.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 20.. Act on securing quality, efficacy and safety of products including pharmaceuticals and medical devices, http://www.japaneselawtranslation.go.jp/law/detail/?id=3213&vm=04&re=01 (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 21.. Ultra-orphan medicines for extremely rare conditions. Scottish Medicines Consortium, https://www.scottishmedicines.org.uk/how-we-decide/ultra-orphan-medicines-for-extremely-rare-conditions/ (accessed 1 September 2020).

- 22.. Naglazyme: EPAR – risk-management-plan summary, https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/rmp-summary/naglazyme-epar-risk-management-plan-summary_en.pdf (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 23.. Postmarket requirements and commitments (searching with Naglazyme), https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/pmc/index.cfm (accessed 15 June 2021).

- 24.. Pharmaceuticals and medical devices safety information no. 334, June 2016, https://www.pmda.go.jp/files/000212847.pdf (accessed 19 March 2021).