Abstract

Objective

Research is lacking regarding the experiences of patients after colostomy, which is needed so as to take necessary specific actions. In this study, we aimed to describe the trajectory of symptom clusters experienced by patients after colostomy over time.

Methods

This was a longitudinal observational study using data from 149 patients with colorectal cancer after colostomy. We investigated symptoms and symptom clusters at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, and 1 year after colostomy.

Results

Four main symptom clusters were identified, including a psychological symptom cluster, digestive and urinary symptom cluster, lack of energy symptom cluster, and pain symptom cluster in patients after colostomy in the first year after surgery. We further explored the symptom trajectory.

Conclusions

We explored symptom clusters and the trajectory of symptom resolution in patients after colostomy during the first year after surgery. Four stages were proposed to describe the different statuses of symptom clusters experienced by patients. Our findings may provide insight into how to improve symptom management and postoperative quality of life for patients after colostomy.

Keywords: Colorectal cancer, colostomy, Colostomy Patient Symptom Assessment Scale, symptom cluster, patient management, quality of life

Introduction

Colorectal cancer has undergone a dramatic increase in terms of incidence and prevalence in Chin, with the fourth and fifth highest incidence and mortality rates, respectively, among all malignancies in 2018.1,2 Colorectal cancer is the second most common cause of cancer death in the United States. 3 Although colostomy can improve the survival rate of some patients, the procedure generates severe physical and psychological symptoms and can adversely affect patients’ quality of life. After colostomy, patients often have stoma-related symptoms like gastrointestinal disorders and pain or may experience discomfort owing to strong odors. Moreover, emotional and social functions may be impaired owing to a lack of confidence and change in body image. 4 Over time, the patterns and resolution of symptoms in patients after colostomy could be multiple and complex. Symptom management in these patients has become a primary clinical concern.

Identifying symptom clusters, defined as “a stable group of two or more concurrent symptoms that are related to one another and independent of other symptom clusters” is considered a fundamental approach in symptom management.5,6 Practical investigation of symptom clusters depends on an understanding of the trajectory of patients' symptoms. To our knowledge, several studies have reported changes in the quality of life among patients with a stoma over time.7–9 However, longitudinal studies of symptom clusters among patients with colorectal cancer after colostomy have rarely been reported. Previous studies on the symptoms of patients after colostomy have involved a cross-sectional design 10 and have measured the symptom prevalence at a single time point. 11 In this longitudinal study, we used the Chinese Version of the Colostomy Patient Symptom Assessment Scale (CPSAS)12,13 to explore the resolution of symptom clusters in patients who underwent colostomy, assessed at 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months and 1 year after surgery.

Methods

Participants

The reporting of this study conforms to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement. 14 The Ethics Committee of Changhai Hospital approved our research, and all participants signed an informed consent form. From January 2015 to December 2019, patients were recruited within 2 weeks following colostomy from the Stoma Clinic of Changhai Hospital. Inclusion criteria for cases were 1) pathology-confirmed colorectal neoplasm; 2) age over 18 years; and 3) ability to understand and complete the questionnaire independently. Exclusion criteria were 1) tumor recurrence or metastasis; 2) cognitive disorders; and 3) severe infection or other severe concurrent diseases.

Data collection

The CPSAS was used to assess patients’ symptoms at 2 weeks (T1), 1 month (T2), 3 months (T3), 6 months (T4), and 1 year (T5) after surgery. The Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale (MSAS) has been widely used as a self-report questionnaire to measure the multidimensional experience of symptoms.15,16 Our research team referred to the MSAS scale and other symptom assessment and quality of life scales, on the basis of which the CPSAS was established. 12 As reported in previous articles, the CPSAS has been verified to have good reliability and validity. 13 The scale contains items addressing 54 physical and psychological symptoms (8 items for digestive symptoms, three items of urinary symptoms, 14 items regarding side effects associated with chemoradiotherapy, 14 items of stoma-related symptoms, three items addressing the patient’s sex life, and 12 items regarding psychological symptoms). A four-point scale is used to measure the severity of each symptom. A trained researcher explained each item on the scale to patients at enrollment. Patients returned the completed questionnaire to the researchers using a self-addressed, prepaid envelope. Baseline and other clinical information, including pathological diagnosis, clinical stage, site and type of stoma, and concurrent chronic diseases, were recorded at enrollment.

Statistical analysis

We carried out data analysis using SPSS version 16 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Uncommon symptoms (occurrence rate <20%) were excluded from the analysis because these do not reflect the key symptoms in a cluster and might interfere with the analysis process and interpretation of results.17–19 At each time point, principle component analysis (PCA) with varimax rotation was performed to determine the number of symptom clusters based on symptom severity ratings. Severity scores were calculated as the mean rating of the items within each symptom cluster. Moreover, we used the t-test to detect differences in each symptom cluster among distinct patient groups.

Results

Participant characteristics

A total of 200 patients were recruited at the beginning of our study. Among them, questionnaires for 51 patients were unable to be evaluated owing to missing items. Therefore, our statistical analysis included 149 patients, with a response rate of 74.5%. Details of the baseline and clinical characteristics of patients are summarized in Table 1. The sex ratio was 1.92:1, and the mean patient age was 59.7 years (range 20 to 84 years); the distribution of patient characteristics was consistent with previous reports of colorectal cancer. 3 Most patients were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma (92.62%) and 71.14% belonged to type B in Dukes Stage. Fewer than half of patients (44.30%) had a temporary stoma, and 55.70% had a permanent stoma. Most patients (83.22%) had no other chronic diseases.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| Variables, N = 149 | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic characteristics | ||

| Sex | ||

| Male | 98 | 65.77% |

| Female | 51 | 34.23% |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 141 | 94.63% |

| Single | 1 | 0.67% |

| Divorced/widowed | 7 | 4.70% |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 59.70 ± 13.39 | |

| Educational level | ||

| Elementary or below | 57 | 38.26% |

| Junior high | 23 | 15.44% |

| Senior high | 35 | 23.49% |

| College or above | 34 | 22.82% |

| Income per month (RMB/USD)* | ||

| Less than 1000/146.4 | 31 | 20.81% |

| 1000/146.4–3000/439.2 | 85 | 57.05% |

| 3000/439.2–5000/732.1 | 24 | 16.11% |

| Over 5000/732.1 | 9 | 6.04% |

| Payment | ||

| Self-payed | 49 | 32.89% |

| Medical insurance | 96 | 64.43% |

| Free | 4 | 2.68% |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Pathological type | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 138 | 92.62% |

| Mucinous carcinoma | 9 | 6.04% |

| Adenoma | 1 | 0.67% |

| Carcinoid | 1 | 0.67% |

| Stage of disease† | ||

| A | 0 | 0 |

| B | 106 | 71.14% |

| C | 38 | 25.50% |

| D | 5 | 3.35% |

| Type of stoma | ||

| Temporary stoma | 66 | 44.30% |

| Permanent stoma | 83 | 55.70% |

| Site of stoma | ||

| Ileum | 62 | 41.61% |

| Transverse colon | 4 | 2.68% |

| Sigmoid colon | 83 | 55.70% |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Yes | 25 | 16.78% |

| No | 124 | 83.22% |

†Dukes Stage.

SD, standard deviation.

Symptoms at five time points

Twenty-five symptoms had over 20% prevalence during the first year after colostomy at five time points. Their occurrence rates, mean severity scores, and mean (standard deviation) at each time point are provided in Table 2. The recorded symptoms at five points gradually decreased from 24 to 22, 18, 15, and finally to 14 symptoms.

Table 2.

Prevalence and severity of each symptom across time.

| Symptoms | T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T5 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | X ± SD | % | X ± SD | % | X ± SD | % | X ± SD | % | X ± SD | |

| Moodiness | 87.92% | 2.28 ± 0.83 | 89.04% | 2.12 ± 0.66 | 62.14% | 1.69 ± 0.61 | 88.18% | 2 ± 0.49 | 72.62% | 1.76 ± 0.49 |

| Depression | 85.91% | 2.23 ± 0.79 | 87.67% | 2.16 ± 0.74 | 62.14% | 1.69 ± 0.61 | 90.91% | 1.98 ± 0.41 | 76.19% | 1.79 ± 0.49 |

| Social disorders | 79.87% | 2.13 ± 0.87 | 83.56% | 2.13 ± 0.83 | 80.71% | 2.00 ± 0.70 | 82.73% | 2 ± 0.59 | 86.90% | 1.93 ± 0.43 |

| Excessive concern about stoma | 74.50% | 2.01 ± 0.83 | 76.03% | 1.91 ± 0.68 | 75.71% | 1.83 ± 0.56 | 77.28% | 1.79 ± 0.45 | 67.86% | 1.68 ± 0.47 |

| Sadness | 71.14% | 2.01 ± 0.87 | 71.92% | 1.91 ± 0.74 | 72.86% | 1.82 ± 0.60 | 77.28% | 1.81 ± 0.48 | 70.24% | 1.70 ± 0.46 |

| Difficulty sleeping | 68.46% | 1.85 ± 0.77 | 51.16% | 1.67 ± 0.70 | 52.14% | 1.59 ± 0.62 | 52.73% | 1.57 ± 0.58 | 46.43% | 1.46 ± 0.50 |

| Disagreeableness | 68.46% | 2.02 ± 0.95 | 69.18% | 1.85 ± 0.74 | 68.57% | 1.79 ± 0.66 | 70.91% | 1.76 ± 0.54 | 63.10% | 1.63 ± 0.49 |

| Nervousness | 64.43% | 1.87 ± 0.83 | 65.07% | 1.80 ± 0.72 | 52.14% | 1.59 ± 0.62 | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Self-abuse | 64.43% | 1.84 ± 0.84 | 63.70% | 1.75 ± 0.71 | 64.29% | 1.69 ± 0.59 | 65.46% | 1.68 ± 0.52 | 72.62% | 1.76 ± 0.51 |

| Worry | 63.09% | 1.94 ± 0.89 | 52.05% | 1.68 ± 0.76 | 52.86% | 1.59 ± 0.62 | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Weight loss | 64.43% | 1.81 ± 0.71 | 61.64% | 1.66 ± 0.56 | 50.00% | 1.53 ± 0.56 | 51.82% | 1.53 ± 0.52 | 51.19% | 1.51 ± 0.50 |

| Fatigue | 61.07% | 1.74 ± 0.67 | 45.21% | 1.48 ± 0.55 | 40.00% | 1.44 ± 0.57 | 41.82% | 1.45 ± 0.55 | 42.86% | 1.43 ± 0.50 |

| Loneliness | 46.98% | 1.68 ± 0.87 | 53.42% | 1.65 ± 0.71 | 53.57% | 1.57 ± 0.58 | 56.36% | 1.60 ± 0.56 | 72.62% | 1.73 ± 0.45 |

| Loss of appetite | 39.60% | 1.49 ± 0.67 | 39.04% | 1.44 ± 0.60 | 35.71% | 1.39 ± 0.54 | 32.73% | 1.33 ± 0.47 | 28.57% | 1.29 ± 0.45 |

| Dysuria | 38.93% | 1.46 ± 0.65 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Dry mouth | 36.91% | 1.42 ± 0.58 | 37.67% | 1.40 ± 0.55 | 38.57% | 1.39 ± 0.50 | 36.36% | 1.37 ± 0.50 | —— | —— |

| Irritability | 36.24% | 1.58 ± 0.90 | 32.19% | 1.42 ± 0.70 | 52.86% | 1.59 ± 0.62 | 23.64% | 1.25 ± 0.45 | 20.24% | 1.20 ± 0.40 |

| Stool with mucus in the stoma bag | 36.24% | 1.38 ± 0.53 | 31.51% | 1.34 ± 0.52 | 32.86% | 1.35 ± 0.52 | 31.82% | 1.32 ± 0.47 | 25% | 1.25 ± 0.44 |

| Sweats | 31.54% | 1.36 ± 0.57 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Mucus discharge from the anus | 31.54% | 1.34 ± 0.51 | 28.77% | 1.31 ± 0.51 | 28.57% | 1.29 ± 0.45 | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Pain in buttocks, anus, or rectum | 31.54% | 1.33 ± 0.50 | 26.71% | 1.27 ± 0.44 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Bellyache | 26.85% | 1.32 ± 0.57 | 28.77% | 1.29 ± 0.45 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Fever | 26.85% | 1.30 ± 0.54 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Sense of dropping in anus or rectum | 24.83% | 1.27 ± 0.49 | 28.08% | 1.28 ± 0.45 | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— | —— |

| Pain on skin around the stoma | 13.59% | 1.17 ± 0.45 | 21.36% | 1.30 ± 0.54 | 17.48% | 1.20 ± 0.49 | ||||

T1: 2 weeks after colostomy, T2: 1 month after colostomy, T3: 3 months after colostomy, T4: 6 months after colostomy, T5: 1 year after colostomy.

Trajectory of symptom clusters

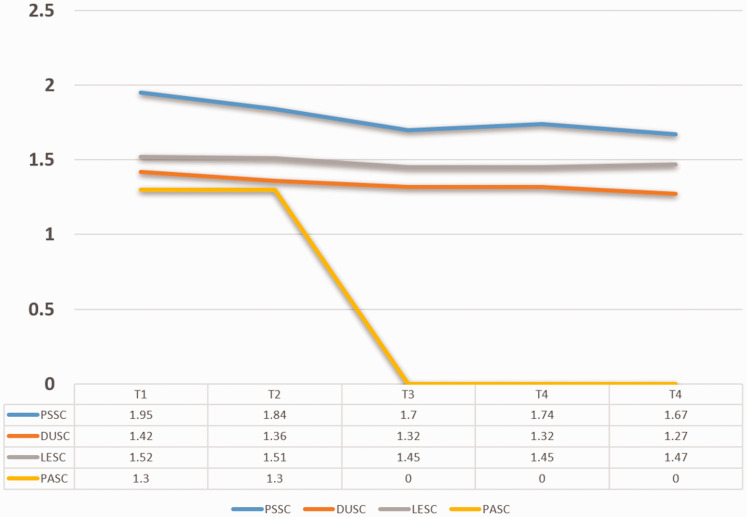

During the 1-year follow-up, four symptom clusters were identified using PCA; these were denoted a psychological symptom cluster (PSSC), digestive and urinary symptom cluster (DUSC), lack of energy symptom cluster (LESC), and pain symptom cluster (PASC). The PSSC was divided into two sub-clusters at T3, psychological symptom cluster I (PSSC I) and psychological symptom cluster (PSSC II). The DUSC and LESC were identified as two stable clusters across the 1-year trajectory. Interestingly, the PASC was not detected as a symptom cluster at T3 in our study because the prevalence of PASC-related symptoms, such as pain in the buttocks, anus, or rectum, were lower than 20% and were excluded during analysis. The rank according to severity of the four clusters was consistent (PSSC > LESC > DUSC > PASC) across the first year after surgery. The included symptoms and their loads in each cluster varied over time, as seen in Table 3. Details of each cluster and symptom at different points are shown in Table 4 and Figure 1. The number of symptom clusters at each time point are given in Table 5.

Table 3.

Symptom loads over time.

| T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSSC (12 items)† | |||||

| Nervousness* | 0.867 | 0.823 | 0.942* | – | |

| Depression* | 0.888 | 0.693 | 0.796 | 0.696 | 0.889 |

| Difficulty sleeping* | 0.826 | 0.825 | 0.749 | 0.720 | 0.653 |

| Excessive concern about stoma | 0.859 | 0.722 | 0.678 | 0.769 | 0.767 |

| Moodiness* | 0.845 | 0.808 | 0.958* | 0.770 | 0.861 |

| Worry* | 0.752 | 0.806 | 0.725 | – | – |

| Sadness | 0.841 | 0.835 | 0.684 | 0.715 | 0.662 |

| Social disorders | 0.846 | 0.696 | 0.958* | 0.677 | 0.425 |

| Irritability* | 0.805 | 0.854 | 0.891* | 0.608 | 0.480 |

| Loneliness | 0.678 | 0.880 | 0.803 | 0.645 | 0.875 |

| Disagreeableness | 0.776 | 0.808 | 0.934* | 0.681 | 0.694 |

| Self-abuse | 0.637 | 0.810 | 0.891* | 0.659 | 0.887 |

| DUSC (4 items) | |||||

| Stool with mucus in stoma bag | 0.804 | 0.837 | 0.512 | 0.746 | 0.791 |

| Loss of appetite | 0.812 | 0.752 | 0.819 | 0.843 | 0.746 |

| Mucus discharge from the anus | 0.843 | 0.666 | 0.788 | – | – |

| Dysuria | 0.644 | – | – | – | |

| LESC (5 items) | |||||

| Sweats | 0.670 | – | – | – | – |

| Dry mouth | 0.658 | 0.759 | 0.726 | 0.760 | – |

| Fatigue | 0.689 | 0.759 | 0.608 | 0.654 | 0.844 |

| Weight loss | 0.677 | 0.727 | 0.770 | 0.730 | 0.818 |

| Fever | 0.797 | – | – | – | – |

| PASC (4 items) | |||||

| Pain in buttocks, anus, or rectum | 0.856 | 0.927 | – | – | – |

| Sense of dropping in anus or rectum | 0.796 | 0.855 | – | – | – |

| Bellyache | 0.727 | 0.854 | – | – | – |

| Pain on skin around the stoma | – | 0.503 | – | – | – |

T1: 2 weeks after colostomy, T2: 1 month after colostomy, T3: 3 months after colostomy, T4: 6 months after colostomy, T5: 1 year after colostomy.

†PSSC divided into PSSC I and PSSC II at T3 and symptoms, with *belonging to PSSC II.

Table 4.

Severity of each symptom cluster across time.

| Symptom cluster | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological symptom cluster | 1.95 ± 0.69 | 1.84 ± 0.58 | 1.70 ± 0.47 | 1.74 ± 0.36 | 1.67 ± 0.35 |

| Digestive and urinary symptom cluster | 1.42 ± 0.48 | 1.36 ± 0.42 | 1.32 ± 0.35 | 1.32 ± 0.39 | 1.27 ± 0.37 |

| Lack of energy symptom cluster | 1.52 ± 0.44 | 1.51 ± 0.43 | 1.45 ± 0.39 | 1.45 ± 0.39 | 1.47 ± 0.43 |

| Pain symptom cluster | 1.30 ± 0.42 | 1.30 ± 0.37 | – | – | – |

T1: 2 weeks after colostomy, T2: 1 month after colostomy, T3: 3 months after colostomy, T4: 6 months after colostomy, T5: 1 year after colostomy.

Figure 1.

Severity of each symptom cluster across time. T1: 2 weeks after colostomy, T2: 1 month after colostomy, T3: 3 months after colostomy, T4: 6 months after colostomy, T5: 1 year after colostomy.

PSSC, psychological symptom cluster; DUSC, digestive and urinary symptom cluster; LESC, lack of energy symptom cluster; PASC, pain symptom cluster.

Table 5.

Number of symptom clusters among patients at each time point.

| Number of symptom clusters | T1 |

T2 |

T3 |

T4 |

T5 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 0 | 82 | 55.03 | 75 | 50.34 | 51 | 34.23 | 104 | 69.80 | 109 | 73.15 |

| 1 | 54 | 36.24 | 54 | 36.24 | 58 | 38.93 | 33 | 22.15 | 30 | 20.13 |

| 2 | 10 | 6.71 | 16 | 10.74 | 25 | 16.78 | 10 | 6.71 | 7 | 4.70 |

| 3 | 3 | 2.02 | 4 | 2.68 | 13 | 8.73 | 2 | 1.34 | 3 | 2.02 |

| 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

T1: 2 weeks after colostomy, T2: 1 month after colostomy, T3: 3 months after colostomy, T4: 6 months after colostomy, T5: 1 year after colostomy.

Discussion

In this study, we described and quantified symptom clusters and the trajectory of symptom cluster resolution experienced by patients after colostomy over the first year after surgery. Four major symptom clusters were identified in the early post-colostomy stage: those involving psychological symptoms, digestive and urinary symptoms, a lack of energy, and pain. Although the number and specific symptoms within each cluster were not identical, we found similarities over time.

Undergoing colostomy is a stressful event with an intensive physico–psychosocial impact on patients within the first 3 months after surgery.8,10 Additionally, most patients with a temporary stoma undergo colostomy reversal within 3 to 6 months after colostomy.20–22 Therefore, follow-up was extended to the first year after surgery to obtain more in-depth results.

Of note, considerable symptom prevalence and severity of the psychological cluster was present after surgery. Moreover, the top three most prevalent and severe symptoms—moodiness, depression, and social disorders—belonged to the PSSC. This finding is consistent with those of previous studies in which patients with stoma had worse social and psychological well-being. 10 Cultural differences might account for this finding. Additionally, the average severity score of symptoms in the PSSC decreased over time, which suggests that patients might experience some psychological support and care from wound therapists. Another interesting finding is that at T3, symptoms of moodiness, depression, nervousness, worry, difficulty sleeping, and irritability were distinguished and formed the PSSC II. A possible interpretation is that these acute psychological symptoms, like nervousness, worry, and difficulty sleeping, decreased over time, forming a new cluster related to patients' adjustment. However, the prevalence and severity of depression and moodiness were lowest at T3 but then started to increase at T4 and T5. Our explanation is that most patients with a temporary stoma undergo colostomy reversal within 3 to 6 months after colostomy. After reversal, this proportion of patients might make efforts to readjust to a normal life; in this way, their negative emotions could appear. Therefore, patients beyond 6 months require more continuous support and extended care.

Across the trajectory, the LESC remained relatively stable during the first year after colostomy, similar to the “sickness symptom cluster” in another study. 23 Symptoms included dry mouth, weight loss, fatigue, fever, and sweats at T1. In contrast, two symptoms—fever and sweats—disappeared from the cluster because of their low incidence at T2, T3, T4, and T5.

The DUSC comprised four symptoms (loss of appetite, stool with mucus in the stoma bag, mucus discharge from the anus, and dysuria) at T1. Dysuria declined such that it had no load on the cluster at T2, T3, T4, and T5. This suggests that medical staff should pay greater attention to patients' nutritional status and help them to develop regular dietary habits.

Another interesting finding of this study was the decrease in the PASC over time, consistent with Sun's study in patients undergoing chemotherapy. 24 In our study, the PASC comprised symptoms of pain in the buttocks, anus or rectum; bellyache, and a sense of dropping in the anus or rectum within 2 weeks after surgery. At T2, the symptom of pain on the skin around the stoma was newly loaded on the cluster. However, at T3, T4, and T5, the prevalence of these symptoms declined and no longer formed a cluster. This might be caused by the acquisition of self-care techniques for the stoma. Moreover, peristomal dermatitis caused by allergy may be relieved over time.

According to our results, symptom clusters had different characteristics at each assessment point. Therefore, the following recommendations might be practical for the clinical management of symptoms in patients after colostomy. First, our investigation showed that the prevalence and severity of four symptom clusters could decrease over time. Therefore, we proposed four stages in patients after colostomy. a) Treatment period (within two 2 after surgery). Medical and nursing staff should strengthen health education for patients and their families at this stage to help them understand stoma correctly, adapt to the stoma, and gain correct knowledge of stoma care so that patients' confidence in stoma management will gradually increase. At the same time, by strengthening patients' abilities of self-care, the incidence of stoma complications after patient discharge from the hospital can be reduced. b) Engagement period (2 weeks to 1 month after surgery). At this stage, patients and family members should have specific abilities with respect to self-care and home care. Medical staff should encourage patients to actively participate in stoma support groups to strengthen mutual communication among patients with stoma and improve their level of social adaptation, stimulate their desire to return to society, and rebuild their confidence in social participation. c) Adaptation period (1 month to 6 months after surgery). In this period, most patients and their families have mastered the knowledge of rehabilitation care. The incidence of various symptoms is relatively low. However, medical staff should not ignore the psychological care of patients and should encourage families and society to provide support to further promote patients’ physiological and psychological rehabilitation and social adaptability, as well as quality of life. d) Reintegration period (6 months to 1 year after surgery). The incidence of various symptoms is relatively low, and quality of life is relatively high for most patients at this stage. Patients should be encouraged to increase their work and social participation and gradually return to society.

By distinguishing stages among patients after surgery, postoperative quality of life can be enhanced via specific, targeted health education. Helping patients improve their understanding of the possible trajectory of symptoms may help them adapt to the stoma during the early stage after colostomy. Additionally, physicians and nurses should pay greater attention to patients’ psychological symptoms in addition to obvious symptoms like dysuria, loss of appetite, and pain.

This study has several limitations, including a relatively small sample size and limited subgroup analysis for patients with colorectal cancer in different clinical stages. Additionally, our study was focused on the first year after colostomy, which might be insufficient to evaluate long-term resolution of symptom clusters. A larger multicenter study with an extended follow-up period is warranted.

Conclusions

In this study, we identified the trajectory of symptom clusters among patients after colostomy, including clusters of psychological, digestive and urinary, low energy, and pain symptoms. Nursing staff should pay greater attention to symptom assessment and provide personalized intervention. Four stages were proposed to describe different conditions of symptom clusters experienced by this patient group. Moreover, the PSSC was verified to have higher prevalence and severity over time. Our results may provide insight to improve symptom management and the postoperative quality of life for patients after colostomy.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and staff who participated in this research.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interest: The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article: This study was sponsored by grants from the General Program of Shanghai Municipal Commission of Health and Family Planning (201440361) and the National Clinical Key Specialty Construction Project of PLA: the Clinical Nursing Specialty.

ORCID iD: Liyan Gu https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9955-3937

References

- 1.Yin J, Bai Z, Zhang J, et al. Burden of colorectal cancer in China, 1990-2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Chin J Cancer Res 2019; 31: 489–498. DOI: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2019.03.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang Y, Hang Z, Li X, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of colorectal cancer in China. Chin J Cancer Res 2020; 32: 729–741. DOI: 10.21147/j.issn.1000-9604.2020.06.06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Sauer AG, et al. Colorectal cancer statistics, 2020. Ca Cancer J Clin 2020; 70: 145–164. DOI: 10.3322/caac.21601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schiergens TS, Hoffmann V, Schobel TN, et al. Long-term Quality of Life of Patients With Permanent End Ileostomy: Results of a Nationwide Cross-Sectional Survey. Dis Colon Rectum 2017; 60: 51–60. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H, McGuire DB, Tulman L, et al. Symptom clusters: concept analysis and clinical implications for cancer nursing. Cancer Nurs 2005; 28: 270–282, 283–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charalambous A, Berger AM, Matthews E, et al. Cancer-related fatigue and sleep deficiency in cancer care continuum: concepts, assessment, clusters, and management. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27: 2747–2753. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-019-04746-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrle F, Sandra-Petrescu F, Weiss C, et al. Quality of Life and Timing of Stoma Closure in Patients With Rectal Cancer Undergoing Low Anterior Resection With Diverting Stoma: A Multicenter Longitudinal Observational Study. Dis Colon Rectum 2016; 59: 281–290. DOI: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan M, Lv L, Zheng M, et al. Quality of Life and Its Influencing Factors Among Chinese Patients With Permanent Colostomy in the Early Postoperative Stage: A Longitudinal Study. Cancer Nurs 2020. DOI: 10.1097/NCC.0000000000000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito N, Ishiguro M, Uno M, et al. Prospective Longitudinal Evaluation of Quality of Life in Patients With Permanent Colostomy After Curative Resection for Rectal Cancer A Preliminary Study. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs 2012; 39: 172–177. DOI: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182456177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song L, Han X, Zhang J, et al. Body image mediates the effect of stoma status on psychological distress and quality of life in patients with colorectal cancer. Psycho-Oncology 2020; 29: 796–802. DOI: 10.1002/pon.5352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marinez AC, Gonzalez E, Holm K, et al. Stoma-related symptoms in patients operated for rectal cancer with abdominoperineal excision. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31: 635–641. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-015-2491-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hao J, Xu H, Qiu Q, et al. Development and preliminary screening of items pool of symptom assessment scale for stoma patients with colorectal cancer. Nurs J Chin PLA 2012; 9: 12–14. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hao J Zhang L andFeng P.. Validation of Chinese Version of Colostomy Patients Symptom Assessment Scale. Chin J Prac Nurs 2012; 33: 48–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Ann Intern Med 2007; 147: 573–577. DOI: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-8-200710160-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fu L, Hu Y, Lu Z, et al. Validation of the Simplified Chinese Version of the Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale-Short Form Among Cancer Patients. J Pain Symptom Manag 2018; 56: 113–121. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Menezes JRD, Luvisaro BMO, Rodrigues CF, et al. Test-retest reliability of Brazilian version of Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale for assessing symptoms in cancer patients. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 2017; 15: 148–154. DOI: 10.1590/S1679-45082017AO3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim M, Kim K, Lim C, et al. Symptom Clusters and Quality of Life According to the Survivorship Stage in Ovarian Cancer Survivors. West J Nurs Res 2018; 40: 1278–1300. DOI: 10.1177/0193945917701688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nho J Kim SR andNam J.. Symptom clustering and quality of life in patients with ovarian cancer undergoing chemotherapy. Eur J Oncol Nurs 2017; 30: 8–14. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejon.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H Abraham I andMalone PS.. Analytical methods and issues for symptom cluster research in oncology. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care 2013; 7: 45–53. DOI: 10.1097/SPC.0b013e32835bf28b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Resio BJ, Jean R, Chiu AS, et al. Association of Timing of Colostomy Reversal With Outcomes Following Hartmann Procedure for Diverticulitis. JAMA Surg 2019; 154: 218–224. DOI: 10.1001/jamasurg.2018.4359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holmgren K, Hultberg DK, Haapamaki MM, et al. High stoma prevalence and stoma reversal complications following anterior resection for rectal cancer: a population-based multicentre study. Colorectal Dis 2017; 19: 1067–1075. DOI: 10.1111/codi.13771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sherman KL andWexner SD.. Considerations in Stoma Reversal. Clin Colon Rectal Surg 2017; 30: 172–177. DOI: 10.1055/s-0037-1598157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salyer J Flattery M andLyon DE.. Heart failure symptom clusters and quality of life. Heart Lung 2019; 48: 366–372. DOI: 10.1016/j.hrtlng.2019.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rha SY Park M andLee J.. Stability of symptom clusters and sentinel symptoms during the first two cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 2019; 27: 1687–1695. DOI: 10.1007/s00520-018-4413-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]