Abstract

Thrombopoietin (TPO) regulates growth and differentiation of megakaryocytes. We previously showed that extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) are required for TPO-mediated full megakaryocytic maturation in both normal progenitors and a megakaryoblastic cell line (UT7) expressing the TPO receptor (Mpl). In these cells, intensity and duration of TPO-induced ERK signal are controlled by several regions of the cytoplasmic domain of Mpl. In this study, we explored the signaling pathways involved in this control. We show that the small GTPases Ras and Rap1 contribute together to TPO-induced ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells and that they do so by activating different Raf kinases as downstream effectors: a Ras–Raf-1 pathway is required to initiate ERK activation while Rap1 sustains this signal through B-Raf. Indeed, (i) in cells expressing wild-type or mutant Mpl, TPO-induced Ras and Rap1 activation correlates with early and sustained phases of ERK signal, respectively; (ii) interfering mutants of Ras and Rap1 both inhibit ERK kinase activity and ERK-dependent Elk1 transcriptional activation in response to TPO; (iii) the kinetics of activation of Raf-1 and B-Raf by TPO follow those of Ras and Rap1, respectively; (iv) RasV12-mediated Elk1 activation was modulated by the wild type or interfering mutants of Raf-1 but not those of B-Raf; (v) Elk1 activation mediated by a constitutively active mutant of Rap1 (Rap1V12) is potentiated by B-Raf and inhibited by an interfering mutant of this kinase. UT7-Mpl cells represent the second cellular model in which Ras and Rap1 act in concert to modulate the duration of ERK signal in response to a growth factor and thereby the differentiation program. This is also, to our knowledge, the first evidence suggesting that Rap1 may play an active role in megakaryocytic maturation.

The classical mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), also known as extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1 and ERK2, respectively), are highly conserved in metazoans and represent one of the major mechanisms orchestrating the delivery of signal from receptors at the cell surface to the nucleus. Once activated, ERKs are translocated to the nucleus, where they regulate gene expression by phosphorylating transcription factors such as Elk1, leading to cell proliferation or differentiation (reviewed in references 54 and 60). Activation of ERK1 and ERK2 requires dual phosphorylation by the MAPK kinase (MAPKK) MEK, which is in turn activated upon phosphorylation by the MAPKK kinases of the Raf family. In a general scheme, this cascade of phosphorylation events is initiated by stimulation of the Ras proto-oncogene following activation of growth factor receptors. Upon association with the GTP-bound form of Ras, Raf kinases translocate from the cytosol to the membrane and are activated by a complex multistep process not yet completely elucidated (reviewed in references 19 and 54).

It has become increasingly apparent in the last few years that, although ERKs are commonly activated, the biological outcome of this signal in a given cell (i.e., proliferation or differentiation) is determined by qualitative differences in the amplitude and duration of ERK activation. Indeed, nerve growth factor (NGF)-induced sustained activation of ERKs has been shown to be a prerequisite for their nuclear translocation and thereby neurite formation in PC12 pheochromocytoma cells, while the transient ERK signal triggered by epidermal growth factor in the same cells leads to proliferation (31). This tight regulation may result from the considerable plasticity existing from one cell to another with respect to ERK activation pathways. A first level of diversity comes from the expression, and the use in a growth factor- and/or cell-type-specific manner, of one or several isoforms of each of the components of the MAPK pathway. In vertebrates, four Ras [H-Ras, N-Ras, K(A)-Ras, and K(B)-Ras], three Raf (A-Raf, B-Raf, and c-Raf/Raf-1), two MEK (MEK1 and MEK2), and two ERK (ERK1 and ERK2) proteins have been identified so far (reference 45 and references therein). The function of these various isoforms is not completely redundant, as demonstrated by the distinct phenotypes resulting from targeted disruption of H-Ras and K-Ras (50) or A-Raf, B-Raf, and Raf-1 (66). A second level of regulation can be achieved by the cooperation of several pathways downstream of Ras activation. In some instances, Ras provides only the initial activating signal and Raf kinases serve as a point of convergence of other receptor-triggered signaling pathways such as the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (Pi3K) pathway (58). Likewise, Raf-1 and the Rho family of small GTPases have been shown to cooperate to increase MEK kinase activity (17). Ras-independent routes to ERK have also been reported, for example, the direct activation of Raf by protein kinase C (8, 27). More recently, a novel pathway has been described involving the specific activation of B-Raf by the Ras family small GTPase Rap1. This pathway was found to drive Ras-independent activation of the ERK-MAPK pathway by cyclic AMP (cAMP) and to cooperate with Ras in inducing the long-lasting ERK activation in response to NGF in a clone of PC12 cells (63, 69).

Proliferation and maturation of megakaryocyte progenitors leading to platelet production are controlled in vivo and in vitro by the c-Mpl receptor and its cognate ligand thrombopoietin (TPO), also known as megakaryocyte growth and differentiation factor (MGDF) (reviewed in reference 25). We have previously shown that TPO promotes both proliferation and differentiation signals in the human megakaryoblastic cell line UT7 expressing Mpl (48). In these cells, TPO induces a sustained activation of ERK which is required for TPO-mediated cell cycle arrest and an increase in megakaryocyte-specific antigens CD41 and CD42b (53). The importance of the ERK pathway in megakaryocytic differentiation was corroborated in several erythroleukemia cell lines where an increase in CD41 could be induced or repressed upon introduction of constitutively activated or dominant negative mutants of MEK or Ras, respectively (34, 35, 65). Furthermore, in normal hematopoietic progenitors isolated from cord blood or bone marrow, the MEK inhibitor PD98059 was found to alter polyploidization (52) or to delay megakaryocytic maturation (14) induced by TPO. Finally, the megakaryocyte-specific enhancer of the α2 integrin gene is directly controlled by ERKs, supporting a direct involvement of this pathway in megakaryocytic maturation (71).

In the present study, we have investigated the mechanisms responsible for the long-lasting activation of ERKs in TPO-stimulated UT7-Mpl cells. Our previous studies had shown that different regions of the cytoplasmic domain of Mpl contribute to mediate full MAPK activation in UT7 cells (53). Indeed, an Mpl mutant displaying an internal deletion of amino acids 71 to 94 of the cytoplasmic domain (mutant MplΔ3) was able to transduce a weak ERK activation and was impaired in its capacity to sustain this signal throughout time. Thus, this region seems to control the duration and amplitude but not the initiation of the MAPK signal in response to TPO. The MplΔ3 mutant was found to transduce Shc phosphorylation normally (53), suggesting that the deleted region might not contribute to Ras activation. This prompted us to search for Mpl-induced Ras-independent routes to ERK. We focused our attention more particularly on the Rap1–B-Raf pathway for several reasons. In the platelet fragments released from the mature megakaryocytes, Rap1 is much more abundant than Ras (40) and is readily activated by platelet agonists such as thrombin (15, 16). An increase in Rap1 but not in Ras expression was reported for several erythroleukemia cell lines induced to differentiate in the presence of chemical agents (1). In preliminary experiments, we observed a similar differential modulation of Rap1 and Ras levels during megakaryocytic differentiation induced by TPO in UT7-Mpl cells, suggesting that Rap1 might play a role in megakaryocytes and their maturation. On the other hand, in a previous study we found that several isoforms of B-Raf are present in hematopoietic cells, including UT7 (13). We show here that TPO activates both Ras and Rap1. The two GTPases cooperate to mediate full ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells by using distinct Raf kinases as downstream effectors: a Ras–Raf-1 pathway is involved in the initiation of the signal, while TPO-induced Rap1 activation is required to sustain ERK signal through B-Raf. This is, to our knowledge, the first evidence that Rap1, by contributing to ERK activation, may play an active role in megakaryocytic maturation induced by TPO.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, cytokines, and antibodies.

Aprotinin, leupeptin, orthovanadate, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), β-glycerophosphate, bovine serum albumin, and myelin basic protein (MBP) were purchased from Sigma. Protein G-Sepharose and glutathione-Sepharose were from Amersham Pharmacia Biotech (Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). Purified inactive recombinant mouse MEK1 was obtained from Upstate Biotechnology Inc. Human recombinant erythropoietin (EPO) was from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany). Human recombinant granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor was obtained at the Central Pharmacy of Paris Hospitals. Two different sources of TPO were used: (i) human recombinant TPO was the pegylated human MGDF (Hu-PEG-MGDF) and was a generous gift from Kirin (Tokyo, Japan); (ii) a TPO mimetic peptide, GW395058 (11), was synthesized by Genosys Biotechnologies Ltd.

Polyclonal antibodies to ERK1, ERK2, Raf-1, and B-Raf were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, Calif.). Affinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibody specific for Rap1 was described previously (5). Anti-Ras mouse monoclonal antibodies were purchased from Transduction Laboratories (Lexington, Ky.). Antibodies specific for the activated forms of ERK1 and ERK2 were from Promega Corp. (Madison, Wis.). Mouse monoclonal antibody clone 12CA5 against influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) was from Boehringer Mannheim.

Plasmid constructs.

pGEX plasmids encoding the Raf-1 or RalGDS Ras-binding domains (RBD) fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) were described previously (20) and were kindly provided by J. Bos (Utrecht University) and J. Downward (Imperial Cancer Research Fund, London, United Kingdom). The expression plasmid for HA-tagged ERK1 (pcDNA3-HA-ERK1) was a gift of J. Pouyssegur's laboratory (UMR 134, Nice, France). The pcDNA3-derived constructs encoding HA-tagged wild-type B-Raf and Raf-1 were described previously (45). The dominant negative mutants of B-Raf (Nter-B-Raf) and Raf-1 (Nter-Raf-1), corresponding to the N-terminal regions of quail B-Raf (amino acids 1 to 443) and human Raf-1 (amino acids 1 to 257), respectively, were obtained by subcloning the EcoRI-SalI fragments of pGBT-9/N-B-Raf and pGBT-9/Raf-1 (44) into the EcoRI-XhoI sites of pcDNA3-HA. pcDNA3/HA-RasV12 and pcDNA3/HA-RasN17 were described previously (9, 44). Rap1N17 and HA-Rap1V12 and HA-Rap1E63 were obtained by PCR-directed mutagenesis of Rap1a (46) and subcloned in pcDNA and pcDNA3-HA vectors, respectively. pLXSN and pSRα vectors encoding the mouse Flag-tagged Rap1–GTPase-activating protein Spa1, kindly provided by N. Minato (Kyoto University), were described previously (61). The PathDetect in vivo trans-reporting system for Elk1, containing the pFA-Elk1 plasmid encoding the DNA-binding domain of yeast Gal4 fused to the activation domain of Elk1 and the pFR-luc plasmid in which expression of the luciferase is controlled by a promoter containing Gal4-binding sites, was purchased from Stratagene (La Jolla, Calif.).

Cell culture and specific cell treatments.

The growth factor-dependent human megakaryoblastic UT7 cell lines expressing either the full-length murine TPO receptor Mpl (UT7-Mpl) or a mutant of this receptor presenting an internal deletion of amino acids 71 to 94 in its intracellular region (UT7-MplΔ3) were engineered as previously described (48). Individual clones (48) and polyclonal cell lines (48, 53) were established in two independent transfection protocols, and both were found to respond similarly to TPO. Cells were cultured in α minimum essential medium (α-MEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and either 2.5 ng of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor per ml or 2 U of EPO per ml. Cells were split twice a week to maintain the cellular concentration up to 250,000 cells/ml. Before activation, cells were washed twice in serum-free medium and resuspended at a concentration of 300,000 cells/ml in α-MEM supplemented with 5% FCS. In some experiments, FCS was replaced by 1% bovine serum albumin to decrease background activation. Stimulations were performed for different times at 37°C by adding either 100 ng of recombinant Hu-PEG-MGDF per ml or 10 nM TPO mimetic peptide, a concentration previously determined to be equivalent to 100 ng of the recombinant cytokine per ml for both proliferation and differentiation of UT7-Mpl cells (I. Dusanter and F. Porteu, unpublished data) and of megakaryocyte progenitors derived from normal CD34+ human cells (S. Fichelson, unpublished data).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Cells (107) were collected by centrifugation, washed once in ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 μM pepstatin, 1 mM orthovanadate, and 5 mM β-glycerophosphate). After 30 min at 4°C, clear cell lysates were obtained by centrifugation at 17,000 × g for 15 min. Supernatants were incubated overnight at 4°C with the indicated antibody, and the resulting immune complexes were collected by incubation with protein G-Sepharose for 1 h at 4°C and washed at least three times in lysis buffer. The pellets were resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer and heated at 100°C for 5 min. Immunoprecipitates or total cell lysates (5 × 105 cells) were separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)–10 to 15% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Hybond-C-super; Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). The membranes were probed with the indicated appropriate primary antibodies followed by peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies. Detection was performed by using the enhanced chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Pull-down assays for the detection of activated Ras and Rap1.

UT7-Mpl cells (107), stimulated or not stimulated with TPO for various times, were washed twice with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline and lysed in buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 200 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% NP-40, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM PMSF, 10 μg of leupeptin per ml, 10 μg of aprotinin per ml, 1 μM pepstatin, 1 mM orthovanadate, and 5 mM β-glycerophosphate, and lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatants were incubated with 40 μg of GST fusion protein, precoupled to glutathione-Sepharose beads and washed twice in cell lysis buffer before used. GST-RalGDS RBD and GST–Raf-1 RBD fusion proteins were used to trap Rap1-GTP and Ras-GTP, respectively, and were produced and immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose as described previously (20). After incubation for 1 h at 4°C, beads were washed three times in lysis buffer and resuspended in Laemmli sample buffer. Samples were analyzed by electrophoresis on an SDS-polyacrylamide gel followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Affinity-purified activated Ras and Rap1 were detected by immunoblotting using specific antibodies, as described above.

Assays for endogenous ERK and Raf activation.

ERK activation was analyzed by immunoblotting of whole-cell extracts (from 5 × 105 cells) with an activation-specific antibody which recognizes the dual-phosphorylated forms of both p42 ERK2 and p44 ERK1. Total ERK levels were revealed by Western blotting with a polyclonal anti-ERK1 antibody (Santa Cruz) that recognizes both ERK1 and ERK2.

Raf-1 and B-Raf activation were detected by immune complex kinase assays as follows. Pellets from 107 cells, stimulated or not stimulated with TPO, were lysed in Triton X-100 lysis buffer, and clear cell lysates were subjected to immunoprecipitation with either anti-Raf-1 or anti-B-Raf antibodies, as described above. Immunoprecipitates were washed twice in lysis buffer, twice in lysis buffer supplemented with 0.5 M NaCl, and finally twice in kinase assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.1 mM EDTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM MnCl2, and 10 mM MgCl2. The kinase reaction was performed at 30°C for 10 min by incubating immunoprecipitates in a total volume of 50 μl of kinase buffer containing 5 μM ATP, 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, and 0.8 μg of inactive recombinant MEK1 as substrate. The reaction was stopped by boiling the samples in Laemmli sample buffer, and the products were resolved on 8% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Radioactive bands were visualized by autoradiography (Kodak MS films). The amounts of precipitated B-Raf or Raf-1 were detected by immunoblotting with specific antibodies.

Cell transfection and transfection-based assays.

Exponentially growing UT7-Mpl (5 × 106) cells were washed three times in serum-free medium and transfected with the indicated plasmids by electroporation at 960 μF and 250 V using a Gene Pulser (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.). Cells were resuspended in α-MEM supplemented with 10% FCS. After overnight cytokine starvation, cells were stimulated with TPO or left untreated for an additional 6 to 24 h before being subjected to luciferase or immunoprecipitation assays.

For the luciferase reporter assay, UT7-Mpl cells were transfected with 10 μg of pFR-luc and 5 μg of pFA-Elk1, together with 10 μg of one or a combination of plasmids encoding activated or dominant negative forms of Ras, Rap1, or Raf, as indicated in Results. The total amount of plasmid transfected was adjusted to be constant in each experiment by adding empty pcDNA3 vector. In order to normalize for transfection efficiency, 1 μg of pcDNA encoding β-galactosidase was cotransfected in all samples. Cell lysis and measurement of luciferase activity were performed by using the luciferase reporter assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. All luciferase assays were performed in duplicate and repeated at least four times with reproducible results. Luciferase activity was normalized to β-galactosidase activity.

To test the action of different Ras and Rap1 mutants directly on ERK activation, cells were cotransfected with 10 μg of pcDNA3-HA-ERK1 and 10 μg of the indicated plasmids. Since the efficiency of transfection in UT7 cells appears to be low, HA-ERK was immunoprecipitated from the cell lysates and ERK activity was measured by its ability to phosphorylate MBP in the presence of 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP, as described previously (53). Samples were resolved on SDS–12% polyacrylamide gels followed by transfer to nitrocellulose membranes. Visualization of phosphorylated MBP was performed by autoradiography and quantified by phosphorimaging (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Results are reported as fold activation above basal levels obtained with cells transfected with HA-ERK1 only. Immunoblotting of the membranes with an anti-HA antibody was used to control the expression of transfected HA-ERK1 in the samples.

RESULTS

TPO induces a transient activation of Ras that does not correlate with the sustained MAPK activation in UT7-Mpl cells.

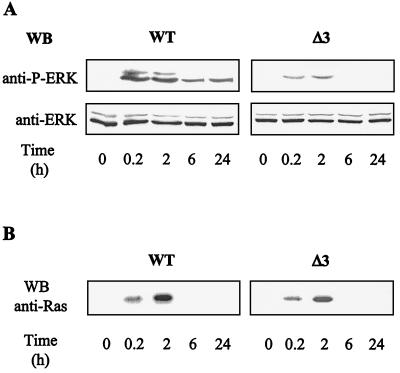

As described previously (53) and also shown in Fig. 1A, TPO induces a strong and sustained activation of ERK in UT7-Mpl cells. ERK activation, detected by an activation-specific anti-phospho-ERK antibody, started around 15 min, reached its maximum around 2 h of treatment, and was largely persistent in cells grown in TPO for up to 24 h (Fig. 1A). ERK activity could still be detected after up to 3 days of culture in the presence of TPO (53).

FIG. 1.

TPO-mediated Ras and ERK activation in UT7-MplWt and UT7-MplΔ3 cells. UT7 cells expressing MplWt (WT) or MplΔ3 (Δ3) receptors were stimulated for various times with 10 nM TPO mimetic peptide. At the indicated times, cells were pelleted and lysed either directly in Laemmli sample buffer for ERK activation (A) or in NP-40 lysis buffer for Ras activation (B). The activity of ERKs was assessed by detecting their phosphorylation upon Western blotting (WB) with a polyclonal anti-phospho-ERK antibody. Total ERK was determined by reprobing the membranes with an antibody recognizing ERK1 and ERK2 in both resting and activated forms. The GTP-bound form of Ras was trapped by pull-down assay using the Raf-1 RBD-GST fusion protein and detected by Western blotting with anti-Ras monoclonal antibody.

In a first attempt to explore the mechanisms responsible for such a sustained activation, we examined the capacity of TPO to activate Ras in UT7-Mpl cells. The RBD of Raf-1 immobilized on glutathione-Sepharose beads was used specifically to pull down the activated GTP-bound form of Ras (20). As shown in Fig. 1B, TPO stimulation resulted in a time-dependent increase in the amount of Ras-GTP precipitated. However, by contrast with ERK activation, Ras-GTP was detected only transiently and levels had completely returned to background by 6 h of stimulation, a time point when ERK activation is still very strong (Fig. 1A). This result suggested that Ras may not be responsible for the long-lasting ERK activation in response to TPO stimulation. To further support this possibility, we made use of a deletion mutant of the TPO receptor (MplΔ3) which we have previously shown to control the level and duration of ERK activation (48, 53). Indeed, in UT7 cells expressing this deletion mutant, TPO induced a faint activation of ERK which returned to basal level after several hours of treatment (Fig. 1A). However, the TPO-induced Ras activation in these cells was similar to that observed in cells expressing the full-length wild-type Mpl (MplWt) (Fig. 1B).

Thus, altogether these results suggest that, although Ras may be involved in the initial phase of ERK activation by TPO, other pathways are required to maintain ERK activation for prolonged periods.

TPO induces a late and persistent activation of Rap1 in UT7 cells expressing MplWt but not the Δ3 mutant.

The recently described requirement of the small GTPase Rap1 to sustain ERK activation in response to NGF in PC12 cells (69) prompted us to examine its role in TPO responses. Therefore, we first analyzed the capacity of TPO to activate Rap1 in UT7 cells expressing wild-type or mutant Mpl forms.

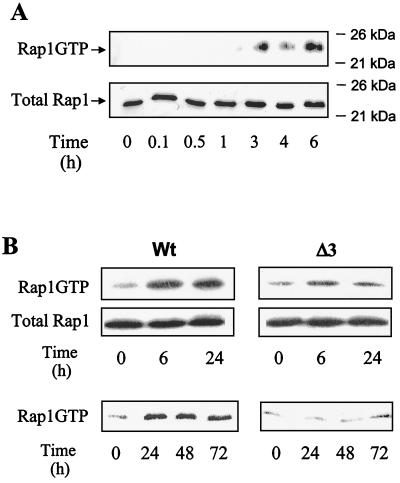

GTP-bound Rap1 was detected by its ability to bind to the GST-RalGDS RBD fusion protein bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads and identified by Western blotting with an affinity-purified polyclonal antibody specific for Rap1. Figure 2A (upper panel) shows that TPO was able to induce Rap1 activation in UT7-Mpl cells. The kinetics of formation of GTP-bound Rap1 is, however, very different from that observed above for Ras: Rap1 activation by TPO was very slow, being detected only after 3 h of treatment with TPO, and persisted until at least 3 days of culture. Western blotting of total lysates with anti-Rap1 (Fig. 2A, lower panel) shows that an increase in pulled-down Rap1-GTP occurred in the absence of an increase in Rap1 expression. Since the long-lived activation of Rap1 is reminiscent of the sustained MAPK signal in response to TPO, we examined whether TPO was able to trigger Rap1 activation in cells expressing the MplΔ3 mutant. As shown in Fig. 2B, a very faint increase in GTP-bound Rap1 above background levels could be detected in UT7-MplΔ3 cells, at all times of TPO treatment, even when the stimulation was prolonged for several days (Fig. 2B, lower panel). This defect could not be accounted for by lower Rap1 expression in these cells since, as shown in Fig. 2B (middle panel), total Rap1 levels in cells expressing wild-type and Δ3 forms of the Mpl receptor were similar. Thus, the late and persistent wave of activation of Rap1, which follows that of Ras, parallels the sustained ERK signal in response to TPO.

FIG. 2.

TPO activates Rap1 in UT7 cells expressing the wild type but not the Δ3 mutant of Mpl receptor. UT7-MplWt (A and B) or UT7-MplΔ3 (B) was treated with 10 nM TPO mimetic peptide for the indicated times, lysed, and subjected to pull-down experiments using the RalGDS RBD-GST fusion protein. Activated Rap1 was detected by Western blotting using a polyclonal antibody specific for Rap1. Total Rap1 levels were detected by directly blotting total-cell lysates with anti-Rap1 antibody.

Both Ras- and Rap1-dependent mechanisms are required for TPO-mediated ERK activation.

The above results suggest that both Ras and Rap1 may be involved in TPO-mediated ERK activation. However, since Rap1 activation does not predict its ability to activate ERK (9, 73), we investigated this hypothesis further by analyzing whether Ras and Rap1 could regulate ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells.

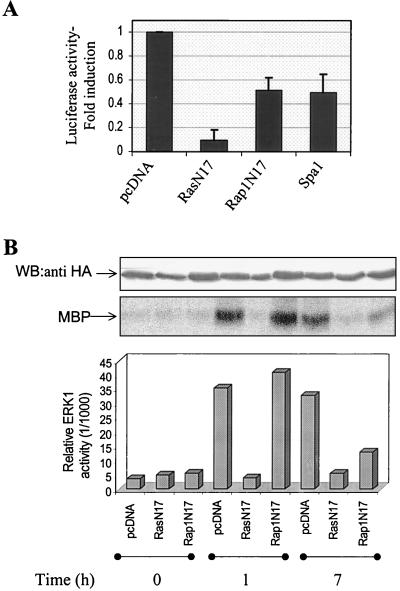

In a first set of experiments, ERK activation was monitored indirectly by measuring the rate of transcription induced by one of its downstream nuclear targets, Elk1. In preliminary experiments, we found that a 6-h treatment with TPO induced a three- to fourfold activation of Elk1-dependent transcription, and a 15- to 20-fold increase in luciferase activity was found after 24 h of stimulation with TPO. This activity was dependent on ERK activation, since it was completely blocked by the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (data not shown). Therefore, Elk1 activation was used as a specific measure of ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells.

We first evaluated whether TPO-induced ERK activation required one or two of the Ras and Rap1 GTPases by introducing dominant negative mutant forms of these proteins. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, expression of both RasN17 and Rap1N17 in UT7-Mpl decreased TPO-mediated Elk1-dependent transcription, while basal activation was only slightly affected (data not shown). In eight independent experiments, RasN17 and Rap1N17 inhibited by 87% ± 8% and 45% ± 12%, respectively, the luciferase activity triggered by 24 h of stimulation with TPO. Since the capacity of Rap1N17 to act as a dominant negative has been questioned (62), we also used the Rap1 GTPase-activating protein Spa1 (61) to block Rap1 activation. Figure 3A shows that Spa1 and Rap1N17 similarly decreased TPO-induced Elk1 activation. Thus, although to different extents, both Ras and Rap1 seem to contribute to TPO-induced ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells.

FIG. 3.

In UT7-Mpl cells, both Ras and Rap1 are required for TPO-induced Elk1 and ERK activation. (A) Inhibition of Elk1 transcriptional activity by expression of interfering Ras and Rap1 mutants. UT7-Mpl cells were transfected with 5 μg of pFA-Elk1 and 10 μg of pFR-luc plasmids of the PathDetect reporting system, along with 1 μg of pcDNA encoding β-galactosidase and 10 μg of either empty vectors or plasmids encoding RasN17, Rap1N17, or Spa1, as indicated. Cells were starved of cytokine overnight and treated for 24 h with TPO before being harvested. Luciferase activity was measured as described in Materials and Methods and normalized to β-galactosidase activity. Results are expressed as fold induction of luciferase activity over that induced in cells transfected with empty pcDNA alone. Average values from eight independent experiments are presented with SEs indicated by the error bars. (B) Rap1 is required for the sustained activation of ERK in response to TPO. UT7-Mpl cells were transiently transfected with plasmid encoding 10 μg of HA-tagged ERK1 along with 10 μg of empty pcDNA or pcDNA encoding RasN17 and Rap1N17, as indicated. After overnight starvation of cytokines, cells were left untreated or stimulated with 10 nM TPO for 1 or 7 h. Transfected ERK was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA monoclonal antibody and subjected to immune kinase assay using MBP as a substrate. Radioactivity was quantified by phosphorimaging and was plotted as relative ERK activity. The expression of equal levels of transfected HA-ERK1 was confirmed by Western blotting (WB) with anti-HA antibody.

Since Elk1 activity increased to its maximum after 12 to 24 h of stimulation with TPO, this assay did not allow us to distinguish the contribution of Ras and Rap1 in the early and late phases of the MAPK response. Thus, the effect of interfering mutants of Ras and Rap1 was examined directly on ERK kinase activity at times of TPO stimulation when either Ras or Rap1 was activated (Fig. 1 and 2). UT7-Mpl cells were cotransfected with the RasN17 or Rap1N17 constructs and with HA-tagged ERK1 and treated for different times with TPO. Because of the low efficiency of transfection of UT7 cells, we were not able to detect HA-ERK activity by Western blotting of total lysates. Therefore, transfected ERK was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies, and its activity was measured in the immunoprecipitates by phosphorylation of exogenously added MBP substrate or by Western blotting with anti-phospho-ERK antibodies. Figure 3B is representative of such an experiment. Western blotting with anti-HA shows that equal levels of HA-ERK1 were expressed in all the samples. Both dominant negative mutants were able to inhibit TPO-induced activation of the transfected HA-ERK1 but in different ways (Fig. 3B). Indeed, RasN17 almost totally blocked ERK activation at early or late time points while RapN17 affected only the ability of TPO to stimulate the sustained phase of ERK activation without inhibiting the initial phase. This result is in agreement with the ability of RasN17 to block almost totally Elk1 activation by TPO, while Rap1N17 decreased this response only partially, as shown above in Fig. 3A.

Altogether, these results show that TPO-induced ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells involves both Ras- and Rap1-dependent mechanisms. Although transient, Ras activation by TPO has a major contribution to this response in both initial and late phases, suggesting that this initial phase might be required for all subsequent activation to occur. The late activation of Rap1 by TPO, by allowing this signal to be sustained over time, is required for maximal ERK activation in response to TPO.

To further document the role of Ras and Rap in ERK activation in UT7 cells, we also examined the effect of constitutively activated forms of both Ras (RasV12) and Rap1 (Rap1V12 and Rap1E63) on Elk1-dependent luciferase activity. As shown in Fig. 4A, expression of RasV12 greatly increased Elk1-dependent luciferase activity in the absence of cytokine stimulation compared to that for cells transfected with empty vector alone. Although less striking, expression of two different forms of constitutively active Rap1 induced Elk1 activation in cytokine-starved UT7-Mpl (Fig. 4A). Both activated Ras and Rap1 mutants could also potentiate TPO-induced Elk1 activation (Fig. 4B). Figure 4C shows that similar amounts of activated Ras and Rap1 were expressed in the transient-transfection assays, as detected by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting of cell lysates with anti-HA antibodies. Both RasV12 and Rap1V12 could also induce activation of a cotransfected HA-ERK1 kinase in the absence of cytokine stimulation (Fig. 4E), confirming the effects observed in the Elk1 reporter assays. Thus, Ras and Rap1 are both able to affect the activation state of ERK in UT7-Mpl cells. The effects of Rap1V12 and RasV12 on both Elk1 and ERK1 activities were synergistic (Fig. 4D and E), suggesting that these two GTPases act on distinct convergent pathways.

FIG. 4.

Activation of Elk1 transcriptional activity in UT7-Mpl cells by constitutively active forms of Ras and Rap1. (A to D) UT7-Mpl cells were transfected with pFA-Elk1 and pFR-luc plasmids of the PathDetect reporting system as described in the legend to Fig. 3, along with empty pcDNA or pcDNA encoding HA-RasV12, HA-Rap1V12, HA-Rap1E63, or HA-RasV12 and HA-Rap1V12 together, as indicated. After overnight cytokine starvation, cells were left untreated (A and D) or treated with 10 nM TPO mimetic peptide (B) for 6 additional h and lysed. (A, B, and D) Luciferase activity was measured in part of the samples and expressed as fold induction over the values obtained in cells transfected with pcDNA alone. The results shown are means + SEs of values obtained in at least three separate assays. (C) Expression of transfected proteins was determined in the remaining lysates by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting with anti-HA antibodies. (E) Synergistic activation of ERK1 by activated Ras and Rap1. UT7-Mpl cells were transiently transfected with plasmid encoding 10 μg of HA-tagged ERK1 along with 10 μg of empty pcDNA or pcDNA encoding RasV12 and Rap1V12 or both, as indicated. Transfected ERK was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA monoclonal antibody, 30 h after transfection, in the absence of TPO. ERK activation was detected by Western blotting with anti-phospho-ERK antibody. The expression of equal levels of transfected HA-ERK1 was confirmed by Western blotting with anti-HA antibody. WB, Western blotting.

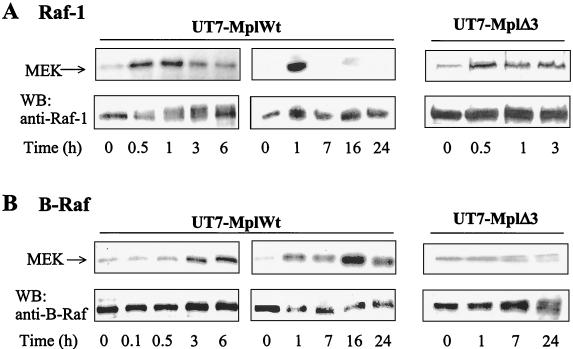

TPO activates both Raf-1 and B-Raf kinases in UT7-Mpl cells.

Downstream effectors of Ras and Rap1 proteins on the MAPK pathway include Raf-1 and B-Raf. Recent studies have suggested that the ability of Rap1 to activate the MAPK pathway in a tissue-specific manner depends on the expression of the high-molecular-weight isoform of B-Raf (63, 69). UT7 cells express both 72- and 95-kDa B-Raf isoforms (13), the latter being much more abundant in the culture conditions used. As an approach to determine whether Raf-1 and/or B-Raf was responsible for ERK activation in response to TPO, we measured Raf-1 and B-Raf kinase activities by immune complex kinase assays on MEK substrate, after short (Fig. 5, left panel) or long (Fig. 5, middle panel) periods of TPO treatment. TPO activated both Raf-1 and B-Raf but with different kinetics: an increase in Raf-1 activity was detected early after TPO stimulation, reached its maximum between 30 and 60 min, and returned to basal levels by 3 h (Fig. 5A). By contrast, B-Raf activation displayed slower kinetics, starting around 1 or 2 h and reaching its maximum only after several hours of stimulation (Fig. 5B). Longer kinetics showed that B-Raf activity was still detected after 24 h of stimulation. Identical results for both Raf-1 and B-Raf assays were obtained when MEK phosphorylation was detected by Western blotting with an activation-specific anti-phospho-MEK antibody recognizing MEK specifically phosphorylated by Raf on Ser217 and Ser221 (data not shown). This indicates that the radioactivity incorporated in the MEK substrate was due to phosphorylation by Raf kinases and not by kinases which might have contaminated the Raf immunoprecipitates. Thus, both Raf-1 and B-Raf may be involved in TPO-mediated activation of ERK, Raf-1 being responsible for ERK activation at early times of stimulation with TPO while B-Raf is involved in sustaining this signal. Supporting this possibility, no activation of B-Raf could be detected upon stimulation of UT7 cells expressing the MplΔ3 mutant in response to TPO (Fig. 5B, right panel), while Raf-1 activation was similar to that detected in UT7-MplWt cells (Fig. 5A, right panel).

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of activation of endogenous Raf-1 and B-Raf in UT7 cells expressing MplWt or MplΔ3. UT7-MplWt and UT7-MplΔ3 cells were stimulated for the various times indicated and lysed. Raf-1 (A) or B-Raf (B) was immunoprecipitated and subjected to in vitro kinase assay, using recombinant inactive MEK as a substrate. Radioactivity incorporated into MEK was revealed by autoradiography. Immunoprecipitated Raf-1 or B-Raf levels were verified by Western blotting (WB) using specific antisera, as indicated. Two sets of kinetics (short and long terms) are shown for UT7-MplWt cells.

Raf-1 and B-Raf are the downstream effectors of Ras and Rap1, respectively, for ERK activation in UT7-Mpl.

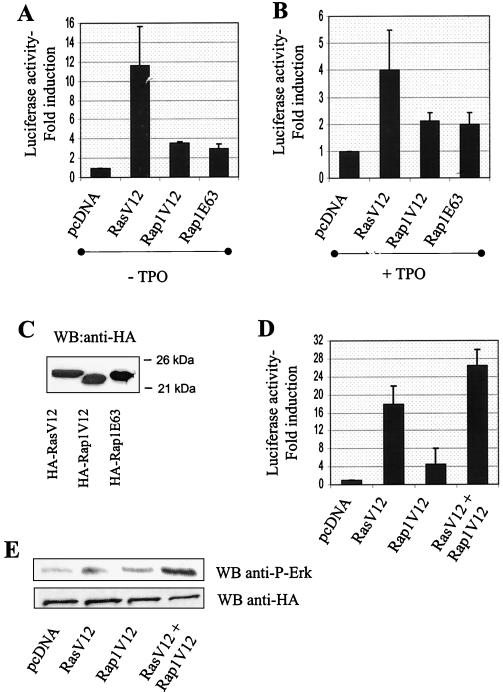

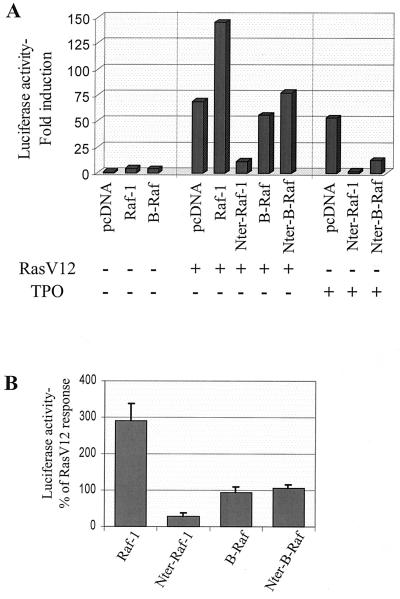

In many systems, Ras has been shown to activate Raf-1 and B-Raf equally (22, 29, 43). However, the striking correlation between the kinetics of activation of Ras and Raf-1, together with the late increase of B-Raf activity occurring when Ras activation has returned to basal levels observed here, strongly suggests that Raf-1 is the only effector downstream of Ras in UT7-Mpl cells stimulated with TPO.

To test this hypothesis, we examined the capacity of wild-type and dominant negative mutants of Raf-1 and B-Raf to modulate Elk1 activation induced by constitutively active RasV12, in UT7-Mpl cells. As shown in a representative experiment (Fig. 6A), exogenous expression of Raf-1 alone has only a small effect on Elk1 activation, but it potentiated Elk1 activation induced by RasV12. By contrast, RasV12-induced Elk1 activation could not be potentiated by cotransfection of wild-type B-Raf (Fig. 6A). In four independent experiments, the average increase of RasV12-mediated luciferase activity by Raf-1 reached about threefold while B-Raf had no effect (Fig. 6B). The capacity of B-Raf to increase Elk1 activation in response to TPO and Rap1V12 (see below and Fig. 7A) shows that B-Raf is functional in this system and that its inability to potentiate the RasV12-mediated effect was not due to a limited amount of a downstream factor. Thus, in UT7-Mpl cells, Ras seems able to activate a Raf-1 but not a B-Raf pathway to Elk1. This result was supported by experiments using the dominant negative mutants of these kinases (Nter-Raf-1 and Nter-B-Raf). Indeed, RasV12-mediated Elk1 transcriptional activity was blocked by cotransfection of Nter-Raf-1 while Nter-B-Raf had no effect (Fig. 6A and B). In the same experiments, Nter-Raf-1 and Nter-B-Raf inhibited TPO-induced Elk1 activation by 92% ± 3% and 65% ± 14% (means ± standard errors [SE], n = 4), respectively, showing that the two mutants are functional in UT7-Mpl cells (Fig. 6A).

FIG. 6.

In UT7-Mpl cells, Raf-1 but not B-Raf mediates the Ras-induced activation of Elk1. UT7-Mpl cells were transiently transfected with pFA-Elk1 and pFR-luc plasmids along with 10 μg of empty pcDNA or pcDNA-RasV12, alone or together with pcDNA encoding wild-type or dominant negative forms of Raf-1 or B-Raf, as indicated. Luciferase activity was measured 30 h after transfection in cells incubated in the absence of cytokine. In the same experiment, the functionality of dominant negative mutants of Raf-1 and B-Raf (Nter-Raf-1 and Nter-B-Raf, respectively) was tested by measuring luciferase activity in cells stimulated with TPO during the last 24 h of incubation. (A) Results from a representative experiment. Luciferase activity is expressed as fold induction over the values obtained in cells transfected with empty pcDNA alone, in the absence of TPO. (B) Effects of wild-type and dominant negative forms of Raf-1 and B-Raf on RasV12-induced Elk1 activation, summarized from four independent experiments. Luciferase activity is expressed as a percentage of the response induced upon expression of RasV12 alone and is presented as average values with error bars indicating SEs.

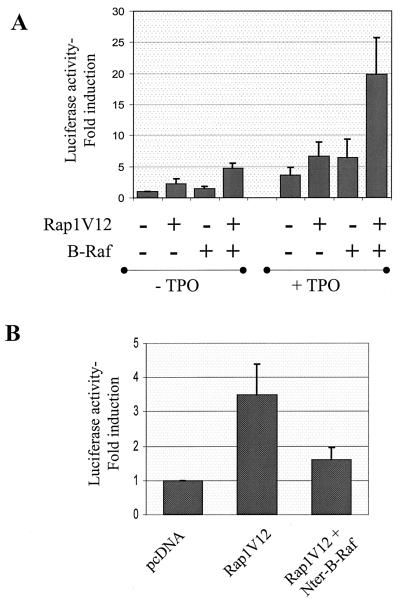

FIG. 7.

Rap1V12 is able to activate a B-Raf-to-Elk1 pathway in UT7-Mpl cells. (A) UT7-Mpl cells were transfected with pFA-Elk1 and pFR-luc plasmids of the PathDetect reporting system, along with 10 μg of empty pcDNA or pcDNA encoding Rap1V12, wild-type B-Raf, or both. After overnight starvation of cytokines, cells were incubated in the presence or the absence of TPO for 6 h and luciferase activity was measured. Data are expressed as fold induction of luciferase activity over that induced in cells transfected with empty pcDNA and not treated with TPO. Values presented are means + SEs from three independent experiments. (B) UT7-Mpl cells were transiently transfected as described above with plasmid encoding Rap1V12, in the presence or the absence of pcDNA encoding a dominant negative mutant of B-Raf (Nter-B-Raf) as indicated. Luciferase activity was assessed 30 h after transfection, in the absence of TPO, and expressed as described above. Results are means + SEs from five independent assays.

These results indicate that Ras signaling to ERK is transduced through Raf-1 and that Ras is unable to couple B-Raf to ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells. Thus, Rap1 is most likely the small GTPase responsible for the late activation of B-Raf induced by TPO in these cells. To determine whether Rap1 could indeed activate a B-Raf-to-ERK pathway in UT7-Mpl cells, we examined the capacity of B-Raf to modulate Elk1 activation induced by constitutively active Rap1V12. Figure 7A shows that, although exogenous expression of B-Raf had almost no effect on Elk1 activation in untreated cells, it could potentiate the activation induced by Rap1V12. In the presence of TPO, Elk1 activation was increased upon transfection of B-Raf or Rap1V12, and the expression of the two proteins together further augmented the level of activation (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, expression of the dominant negative mutant of B-Raf blocked Rap1V12-mediated Elk1 activation (Fig. 7B). Thus, in UT7-Mpl cells, Rap1, but not Ras, can couple B-Raf to ERK activation. B-Raf activation observed in UT7-MplWt cells after 1 h of TPO treatment (Fig. 5B) might therefore be due to small levels of Rap1GTP generated at that time but too low to be detected by pull-down assay.

Altogether, these results suggest that TPO-mediated ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells involves the cooperation of Ras–Raf-1 and Rap1–B-Raf pathways.

DISCUSSION

The small GTP-binding protein Rap1 is very closely related to Ras. Particularly, these proteins have almost identical effector domains, suggesting that they might share common downstream effectors. Indeed, Rap1 binds tightly to most Ras effectors, including the various Raf kinases (50, 72). However, whether this association is coupled to activation of the Raf-ERK pathway in vivo and whether Rap1 activation by growth factors qualitatively or quantitatively modulates Ras signaling to ERK are still under debate. Rap1 was described originally by its ability to antagonize Ras-induced transformation and ERK activation (10, 26) by sequestering and maintaining Raf-1 in an inactive complex (21, 63). It has also been reported that, in some instances, downregulation of Rap1 activity is a prerequisite to allow Ras signaling to ERK (7, 42). In the past few years, a Rap1–B-Raf pathway has been found to be responsible for the positive effect of cAMP on ERK activation in various cells (12, 55, 56, 63, 64). However, data showing the capacity of Rap1 to cooperate with Ras-dependent signaling to ERK in response to growth factors are scarce, and this role of Rap1 relies mainly so far on a study using a particular subclone of PC12 cells (PC12-GR5) stimulated with NGF (69). In addition, the recent development of a method detecting the GTP-bound form of endogenous Rap1 has enabled researchers to demonstrate that, in many cell types, including PC12 cells treated with NGF, Rap1 activation by growth factors or cAMP correlates with neither activation nor inhibition of ERK signal, and this suggests that Rap1 may activate its own specific pathways (9, 72, 73). This has led to the assumption that the modulating effects of Rap1 on Ras signaling to ERK not only depend on the cell type examined but also might also have been brought about by ectopic overexpression of Rap1. We show here, both by correlating endogenous activation of Rap1 and Ras with that of ERK and by using interfering mutants of these GTPases, that both Rap1 and Ras are required for maximal activation of ERK induced by TPO in the megakaryoblastic UT7 cell line. These results therefore support, in a second cellular model, the concept that Rap1 can contribute directly to ERK activation and positively cooperate with Ras to lead to maximal activation of this pathway in response to a growth factor.

By analogy with the activation of MAPK induced by NGF in PC12-GR5 cells (69), TPO-induced ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells seems to be initiated by Ras while Rap1 is required only in a second phase to sustain this signal throughout time. This was suggested first by comparing the capacity of TPO to induce Ras and Rap1 activation in UT7 cells expressing MplWt or a mutant form of this receptor able to transduce only a transient MAPK signal in response to TPO. Indeed, first, TPO induced a similar rapid and transient GTP loading of Ras in both types of cells, and second, in UT7 cells expressing the wild-type receptor, Rap1 activation started only after several hours of TPO treatment, at a time when Ras activation had returned to basal levels, and no increase in Rap1GTP could be detected in UT7 cells expressing the MplΔ3 mutant. The hypothesis that Rap1 contribution is limited to the late phase of ERK activation was also supported by experiments showing the capacity of a dominant negative mutant of Rap1 to inhibit ERK activation at late but not early time points of TPO stimulation. Very recently, an interfering mutant of Rap1 has also been shown to block only the late phase of activation of ERK downstream of integrins (4). Thus, it is tempting to speculate that the coupling of Rap1 to ERK activation might be a common mechanism used to prolong ERK activation after the downregulation of Ras.

In NGF-stimulated PC12-GR5 cells, the two waves of Ras and Rap1 signaling to ERK have been shown to be completely independent (69). By contrast, although the transient activation of Ras alone is not sufficient to explain the long-lasting ERK signal in UT7-Mpl cells, the ability of RasN17 to inhibit most of the TPO-induced Elk1 activation as well as ERK kinase activity at both early and late times of TPO treatment suggests that the Ras-dependent initial phase may be required for all subsequent ERK activation to occur. Supporting this possibility, ERK activation in early or late phases of TPO stimulation was completely abrogated in UT7 cells expressing Mpl receptor mutants deficient in their capacity to activate Ras (F. Porteu, unpublished data). Such a requirement of Ras for Rap1-mediated effect is reminiscent of data showing that Rap1 oncogenicity in Swiss 3T3 cells is revealed only in the presence of growth factors signaling through Ras (3).

The ability of Rap1 to activate or inhibit the MAPK pathway in a tissue-specific manner has been suggested to depend on the cell ratio of Raf-1 and B-Raf downstream effectors and more particularly on the expression of the high-molecular-weight isoform of B-Raf. Indeed, although Rap1 binds both Raf-1 and B-Raf, it triggers only B-Raf kinase activity (41, 43, 63). Thus, Rap1 would be a selective activator of B-Raf and by trapping Raf-1 in a nonfunctional complex would prevent its activation by Ras and the downstream MAPK signal (7, 21, 42, 63). B-Raf is then thought to act as a molecular switch to convert Rap1 from a negative to a positive regulator of ERK. UT7 cells express high levels of B-Raf, and the 95-kDa isoform is the major B-Raf species in these cells (13). Endogenous B-Raf is activated by TPO and would contribute to the late phase of TPO signaling to ERK. In transient-transfection experiments, Rap1V12 was found to couple B-Raf to Elk1 activation. That Rap1 acts as an upstream activator of B-Raf on the ERK pathway in response to TPO is strongly suggested by the striking resemblance of the kinetics of activation of B-Raf and Rap1 and by the inability of TPO to activate B-Raf as well as Rap1 in UT7 cells expressing the MplΔ3 mutant.

The presence of the 95-kDa isoform of B-Raf and its capacity to be activated by Rap1 might not be the sole regulation mechanism determining the final outcome of Rap1 activation on ERK signal. Indeed as discussed above, Rap1 activation does not always lead to ERK activation in B-Raf-expressing cells (9, 73). By using Ras-Rap1 chimeras, Matsubara and collaborators (33) have shown that, although both Ras and Rap1 bind to RalGDS, only Ras, because of its localization at the plasma membrane in the vicinity of Ral, activates the RalGDS-Ral pathway in vivo. As for RalGDS, the recruitment of Raf at the plasma membrane has been shown to be a key event in its activation (57). By contrast with other types of cells where Rap1 is localized mainly to late endosomes and mid-Golgi complex (5, 47), Rap1 is found both in α granules and at the plasma membrane of platelets (6, 38). Platelet activation with agonists can modulate the level of Rap1 present at the membrane by inducing translocation of α granules (38). A similar distribution has been observed in megakaryocytes (6). Although we were not able to detect endogenous Rap1 by fluorescence or Rap1–B-Raf interaction in UT7 cells, the presence of Rap1 at the plasma membrane or the possibility of bringing it there upon stimulation, in megakaryoblastic cells such as UT7, may account for the capacity of Rap1 to generate a functional B-Raf-to-ERK coupling.

By contrast with Rap1, Ras is well known to be able to activate equally Raf-1 and B-Raf in vitro and in vivo (22, 29, 41, 43). Surprisingly, however, the coordinated activation of Ras and Raf-1 by TPO, together with the defect in B-Raf activation in UT7-MplΔ3 cells in which Ras activation occurs normally, suggests that in UT7 cells B-Raf is not activated by Ras, Raf-1 being the only downstream target of Ras in the initial phase of ERK activation. In these cells, RasV12-induced Elk1 activity was also dependent exclusively on Raf-1. The use of only one Raf isoform by Ras in cells expressing both Raf-1 and B-Raf has already been observed in other systems upon stimulation with growth factors or cAMP (9, 23), but how this segregation occurs remains puzzling. Notable differences in the modes of regulation of B-Raf and Raf-1 (19, 45) and their activation by Ras have been reported (19, 29, 32). The activation of Raf kinases by Ras is complex and not yet completely elucidated. It is thought to depend on transient association of Raf with GTP-bound Ras allowing membrane recruitment of Raf, conformational changes, phosphorylation by tyrosine and/or serine kinases, and interactions with accessory proteins such as 14-3-3 proteins and Hsp90 (19, 23, 32, 44). Several hours of stimulation might be needed for TPO to induce one critical event required for B-Raf activation. However, the capacity of B-Raf to enhance Rap1V12-induced Elk1 activation indicates that B-Raf can be activated in UT7-Mpl cells in the absence of TPO. By contrast, RasV12 also seems unable to couple exogenously cotransfected wild-type B-Raf to Elk1 activation. An attractive possibility for explaining these results would be the induction of a specific inhibitor of B-Raf in UT7 cells whenever Ras is activated (constitutively or upon TPO stimulation). The Pi3K-Akt pathway which lies downstream of Ras (51) and is activated rapidly by TPO in UT7-Mpl cells (D. Bouscary et al., submitted for publication) might very well play this role. Indeed, a very recent study has shown that Akt can inhibit B-Raf kinase activity by phosphorylating the N-terminal domain of B-Raf at multiple sites (18). Since the Pi3K pathway has been found to have conflicting effects on Raf-1, either inhibiting its kinase activity through Akt (70) or activating its kinase activity through PAK (58), experiments are currently under way to determine whether the initial activation of Pi3K by TPO would inhibit B-Raf while allowing Raf-1 activation. Alternatively, as described above, differences between Ras and Rap1 in their localization and interaction with phospholipids may modulate their ability to activate downstream effectors (28, 33). Thus, a specific localization of the Raf kinases in the UT7 cell could specify the interaction of Raf-1 but not B-Raf with RasGTP. Differential subcellular localization of Raf kinases has been observed in neurons (36). Interestingly, in a very recent study, York and collaborators (68) have shown that B-Raf is localized to vesicles in neurons and PC12 cells and that endocytosis, probably because it brings B-Raf in contact with the GTPase, is required for its activation by Ras. It would be interesting to compare the subcellular distributions of Raf-1 and B-Raf in UT7 cells, as well as in other cell types where the exclusive use of one of these kinases by a small GTPase has been demonstrated (9, 23), to determine whether this is a key element governing the specificity of the activation.

Ras activation by tyrosine kinases or cytokine receptors usually occurs through coupling the Grb2-Sos preformed complex to tyrosine-phosphorylated residues of the receptors, either directly or indirectly. Similarly, the first specific Rap1 guanine nucleotide exchange factor identified, C3G, forms a complex with Cbl and Crk which can be recruited by activated receptors (7, 72). TPO-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of both Cbl and Crk-L and association of the Crk-L–C3G complex with Mpl have been described in various cell lines (37, 39), suggesting that C3G might be involved in Rap1 activation by TPO. However, although TPO-induced Crk-L phosphorylation was detected in UT7-Mpl cells, it is a rapid and transient event which occurs similarly in cells expressing MplWt and in cells expressing MplΔ3 and thus parallels the increase in RasGTP rather than Rap1GTP levels (data not shown). In addition, association of the Cbl-Crk-C3G complex with Mpl was not observed. A recent report has shown that Rap1N17 could not titrate away C3G in vivo (62). The ability of Rap1N17 to interfere with TPO-induced ERK activation would thus suggest that Rap1 GTP loading is unlikely to be dependent on C3G in UT7-Mpl cells. However, experiments with dominant negative forms of C3G would be required to formally rule out this possibility. Recently, Rap1 has been shown to be activated by different types of second messengers such as calcium, cAMP, or diacylglycerols (2, 15, 16, 72), and Rap1-specific guanine nucleotide exchange factors sensitive to these mediators have been identified (72). However, protein kinase A activation by TPO has not been described, and neither forskolin nor cAMP analogues were found to influence positively or negatively Rap1 or ERK activation in UT7-Mpl cells. Likewise, no activation of Rap1 was observed upon phorbol myristate acetate or calcium ionophore treatments (data not shown), suggesting that TPO-induced diacylglycerol or calcium pathways are unlikely to be involved in Rap1 activation. Finally, Rap1 has been shown to be activated by cell adhesion (49, 61), and in thrombin-stimulated platelets, activation of the αIIbβ3 integrin contributes to the sustained phase of Rap1 activation (16). TPO increases αIIbβ3 expression at the surface of UT7-Mpl cells, and this function is impaired in UT7 cells expressing the MplΔ3 mutant (48). Experiments are under way to determine whether TPO activates αIIbβ3 integrin and whether this activation occurs differentially in UT7 cells expressing MplWt or mutant, in response to TPO.

Several hours of stimulation with TPO are required for activation of Rap1. This late activation is intriguing, since Rap1 is a proximal signaling event following receptor-growth factor interaction in many systems (72, 73). Rap1 GTP loading induced by TPO was not affected by cycloheximide (data not shown), ruling out the requirement for new protein synthesis in Rap1 activation. Other mechanisms of regulation which have been shown to affect Rap1 activation posttransductionally and may be activated by TPO include phosphorylation (15, 38), translocation from an intracellular vesicular compartment to the plasma membrane or cytoskeleton (15, 16, 30, 38, 59), and release of Rap1 from a Rap GTPase-activating protein (24). The possibility that ERKs activated in the initial phase could provide an activating phosphorylation event on Rap1 was ruled out, since TPO-induced Rap1 activation was neither impaired nor delayed in the presence of the MEK inhibitor PD98059 (data not shown).

The requirement for Ras in TPO-induced differentiation has been described previously in an erythroleukemic cell line (34). However, even though Rap1 is very abundant in platelets, to our knowledge, the role of Rap1 in megakaryocytic differentiation has never been explored before. The cooperation between Ras and Rap1 to allow full activation of ERK in response to TPO, shown here, constitutes the first step in the demonstration of an active participation of both GTPases in megakaryocytic maturation. Besides the Raf-ERK pathway, Ras can activate other downstream effectors. Further studies will determine whether Rap1 can cooperate with Ras on these pathways as well. The capacity of TPO to activate Ral and ERK with very similar kinetics in UT7-Mpl cells (J. Garcia and F. Porteu, unpublished observations) and the observation that, in platelets, Ral activation correlates with Rap1 rather than with Ras activation (67) may support this possibility.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Kirin (Tokyo, Japan) for providing recombinant Hu-PEG-MGDF and N. Minato (Kyoto University) and J. Pouyssegur (UMR 134, Nice, France) for flag-Spa1 and HA-ERK1 expression vectors, respectively.

This work was supported by the Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale and by a grant from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer (associated laboratory). J.G. is the recipient of a fellowship from the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adachi M, Ryo R, Yoshida A, Sugano W, Yasunaga M, Saigo K, Yamaguchi N, Sato T, Sano K, Kaibuchi K, Takai Y. Induction of smg p21/rap1A p21/krev-1 p21 gene expression during phorbol ester-induced differentiation of a human megakaryocytic leukemia cell line. Oncogene. 1992;7:323–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altschuler D L, Peterson S N, Ostrowski M C, Lapetina E G. Cyclic AMP-dependent activation of Rap1b. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10373–10376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altschuler D L, Ribeiro-Neto F. Mitogenic and oncogenic properties of the small G protein Rap1b. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7475–7479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barberis L, Wary K K, Fiucci G, Liu F, Brancaccio M, Altruda F, Tarone G, Giancotti F G. Distinct roles of the adaptor protein Shc and focal adhesion kinase in integrin signaling to ERK. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:36532–36540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002487200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beranger F, Goud B, Tavitian A, de Gunzburg J. Association of the Ras-antagonistic Rap1/Krev-1 proteins with the Golgi complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:1606–1610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.5.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berger G, Quarck R, Tenza D, Levy-Toledano S, de Gunzburg J, Cramer E M. Ultrastructural localization of the small GTP-binding protein Rap1 in human platelets and megakaryocytes. Br J Haematol. 1994;88:372–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1994.tb05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boussiotis V A, Freeman G J, Berezovskaya A, Barber D L, Nadler L M. Maintenance of human T cell anergy: blocking of IL-2 gene transcription by activated Rap1. Science. 1997;278:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5335.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burgering B M, de Vries-Smits A M, Medema R H, van Weeren P C, Tertoolen L G, Bos J L. Epidermal growth factor induces phosphorylation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase 2 via multiple pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:7248–7256. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.12.7248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busca R, Abbe P, Mantoux F, Aberdam E, Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A, Ortonne J P, Ballotti R. Ras mediates the cAMP-dependent activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) in melanocytes. EMBO J. 2000;19:2900–2910. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.12.2900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cook S J, Rubinfeld B, Albert I, McCormick F. RapV12 antagonizes Ras-dependent activation of ERK1 and ERK2 by LPA and EGF in Rat-1 fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1993;12:3475–3485. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cwirla S E, Balasubramanian P, Duffin D J, Wagstrom C R, Gates C M, Singer S C, Davis A M, Tansik R L, Mattheakis L C, Boytos C M, Schatz P J, Baccanari D P, Wrighton N C, Barrett R W, Dower W J. Peptide agonist of the thrombopoietin receptor as potent as the natural cytokine. Science. 1997;276:1696–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5319.1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dugan L L, Kim J S, Zhang Y, Bart R D, Sun Y, Holtzman D M, Gutmann D H. Differential effects of cAMP in neurons and astrocytes. Role of B-raf. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25842–25848. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eychene A, Dusanter-Fourt I, Barnier J V, Papin C, Charon M, Gisselbrecht S, Calothy G. Expression and activation of B-Raf kinase isoforms in human and murine leukemia cell lines. Oncogene. 1995;10:1159–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fichelson S, Freyssinier J M, Picard F, Fontenay-Roupie M, Guesnu M, Cherai M, Gisselbrecht S, Porteu F. Megakaryocyte growth and development factor-induced proliferation and differentiation are regulated by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in primitive cord blood hematopoietic progenitors. Blood. 1999;94:1601–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franke B, Akkerman J W, Bos J L. Rapid Ca2+-mediated activation of Rap1 in human platelets. EMBO J. 1997;16:252–259. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.2.252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franke B, van Triest M, de Bruijn K M, van Willigen G, Nieuwenhuis H K, Negrier C, Akkerman J W, Bos J L. Sequential regulation of the small GTPase Rap1 in human platelets. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:779–785. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.3.779-785.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frost J A, Steen H, Shapiro P, Lewis T, Ahn N, Shaw P E, Cobb M H. Cross-cascade activation of ERKs and ternary complex factors by Rho family proteins. EMBO J. 1997;16:6426–6438. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guan K L, Figueroa C, Brtva T R, Zhu T, Taylor J, Barber T D, Vojtek A B. Negative regulation of the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf by Akt. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27354–27359. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004371200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hagemann C, Rapp U R. Isotype-specific functions of Raf kinases. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:34–46. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrmann C, Horn G, Spaargaren M, Wittinghofer A. Differential interaction of the ras family GTP-binding proteins H-Ras, Rap1A, and R-Ras with the putative effector molecules Raf kinase and Ral-guanine nucleotide exchange factor. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6794–6800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu C D, Kariya K, Kotani G, Shirouzu M, Yokoyama S, Kataoka T. Coassociation of Rap1A and Ha-Ras with Raf-1 N-terminal region interferes with ras-dependent activation of Raf-1. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11702–11705. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jaiswal R K, Moodie S A, Wolfman A, Landreth G E. The mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade is activated by B-Raf in response to nerve growth factor through interaction with p21ras. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:6944–6953. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.10.6944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaiswal R K, Weissinger E, Kolch W, Landreth G E. Nerve growth factor-mediated activation of the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase cascade involves a signaling complex containing B-Raf and HSP90. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23626–23629. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.39.23626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jordan J D, Carey K D, Stork P J, Iyengar R. Modulation of rap activity by direct interaction of Galpha(o) with Rap1 GTPase-activating protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21507–21510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin: the primary regulator of megakaryocyte and platelet production. Thromb Haemostasis. 1995;74:521–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kitayama H, Sugimoto Y, Matsuzaki T, Ikawa Y, Noda M. A ras-related gene with transformation suppressor activity. Cell. 1989;56:77–84. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90985-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kolch W, Heidecker G, Kochs G, Hummel R, Vahidi H, Mischak H, Finkenzeller G, Marme D, Rapp U R. Protein kinase C alpha activates RAF-1 by direct phosphorylation. Nature. 1993;364:249–252. doi: 10.1038/364249a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuroda S, Ohtsuka T, Yamamori B, Fukui K, Shimizu K, Takai Y. Different effects of various phospholipids on Ki-Ras-, Ha-Ras-, and Rap1B-induced B-Raf activation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:14680–14683. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.25.14680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marais R, Light Y, Paterson H F, Mason C S, Marshall C J. Differential regulation of Raf-1, A-Raf, and B-Raf by oncogenic ras and tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4378–4383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maridonneau-Parini I, de Gunzburg J. Association of rap1 and rap2 proteins with the specific granules of human neutrophils. Translocation to the plasma membrane during cell activation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:6396–6402. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marshall C J. Specificity of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling: transient versus sustained extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation. Cell. 1995;80:179–185. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mason C S, Springer C J, Cooper R G, Superti-Furga G, Marshall C J, Marais R. Serine and tyrosine phosphorylations cooperate in Raf-1, but not B-Raf activation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2137–2148. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Matsubara K, Kishida S, Matsuura Y, Kitayama H, Noda M, Kikuchi A. Plasma membrane recruitment of RalGDS is critical for Ras-dependent Ral activation. Oncogene. 1999;18:1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Matsumura I, Nakajima K, Wakao H, Hattori S, Hashimoto K, Sugahara H, Kato T, Miyazaki H, Hirano T, Kanakura Y. Involvement of prolonged ras activation in thrombopoietin-induced megakaryocytic differentiation of a human factor-dependent hematopoietic cell line. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:4282–4290. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.7.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Melemed A S, Ryder J W, Vik T A. Activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway is involved in and sufficient for megakaryocytic differentiation of CMK cells. Blood. 1997;90:3462–3470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morice C, Nothias F, Konig S, Vernier P, Baccarini M, Vincent J D, Barnier J V. Raf-1 and B-Raf proteins have similar regional distributions but differential subcellular localization in adult rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1995–2006. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morita H, Tahara T, Matsumoto A, Kato T, Miyazaki H, Ohashi H. Functional analysis of the cytoplasmic domain of the human Mpl receptor for tyrosine-phosphorylation of the signaling molecules, proliferation and differentiation. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:228–234. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagata K, Nozawa Y. A low M(r) GTP-binding protein, Rap1, in human platelets: localization, translocation and phosphorylation by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Br J Haematol. 1995;90:180–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1995.tb03398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oda A, Miyakawa Y, Druker B J, Ishida A, Ozaki K, Ohashi H, Wakui M, Handa M, Watanabe K, Okamoto S, Ikeda Y. Crkl is constitutively tyrosine phosphorylated in platelets from chronic myelogenous leukemia patients and inducibly phosphorylated in normal platelets stimulated by thrombopoietin. Blood. 1996;88:4304–4313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ohmori T, Kikuchi A, Yamamoto K, Kim S, Takai Y. Small molecular weight GTP-binding proteins in human platelet membranes. Purification and characterization of a novel GTP-binding protein with a molecular weight of 22,000. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:1877–1881. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtsuka T, Shimizu K, Yamamori B, Kuroda S, Takai Y. Activation of brain B-Raf protein kinase by Rap1B small GTP-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:1258–1261. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.3.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okada S, Matsuda M, Anafi M, Pawson T, Pessin J E. Insulin regulates the dynamic balance between Ras and Rap1 signaling by coordinating the assembly states of the Grb2-SOS and CrkII-C3G complexes. EMBO J. 1998;17:2554–2565. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.9.2554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okada T, Hu C D, Jin T G, Kariya K, Yamawaki-Kataoka Y, Kataoka T. The strength of interaction at the Raf cysteine-rich domain is a critical determinant of response of Raf to Ras family small GTPases. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6057–6064. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.9.6057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Papin C, Denouel A, Calothy G, Eychene A. Identification of signalling proteins interacting with B-Raf in the yeast two-hybrid system. Oncogene. 1996;12:2213–2221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Papin C, Denouel-Galy A, Laugier D, Calothy G, Eychene A. Modulation of kinase activity and oncogenic properties by alternative splicing reveals a novel regulatory mechanism for B-Raf. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24939–24947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pizon V, Chardin P, Lerosey I, Olofsson B, Tavitian A. Human cDNAs rap1 and rap2 homologous to the Drosophila gene Dras3 encode proteins closely related to ras in the ‘effector’ region. Oncogene. 1988;3:201–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pizon V, Desjardins M, Bucci C, Parton R G, Zerial M. Association of Rap1a and Rap1b proteins with late endocytic/phagocytic compartments and Rap2a with the Golgi complex. J Cell Sci. 1994;107:1661–1670. doi: 10.1242/jcs.107.6.1661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Porteu F, Rouyez M C, Cocault L, Benit L, Charon M, Picard F, Gisselbrecht S, Souyri M, Dusanter-Fourt I. Functional regions of the mouse thrombopoietin receptor cytoplasmic domain: evidence for a critical region which is involved in differentiation and can be complemented by erythropoietin. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2473–2482. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Posern G, Weber C K, Rapp U R, Feller S M. Activity of Rap1 is regulated by bombesin, cell adhesion, and cell density in NIH3T3 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:24297–24300. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.38.24297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reuther G W, Der C J. The Ras branch of small GTPases: Ras family members don't fall far from the tree. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2000;12:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rodriguez-Viciana P, Warne P H, Vanhaesebroeck B, Waterfield M D, Downward J. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase by interaction with Ras and by point mutation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2442–2451. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rojnuckarin P, Drachman J G, Kaushansky K. Thrombopoietin-induced activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in normal megakaryocytes: role in endomitosis. Blood. 1999;94:1273–1282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rouyez C M, Boucheron C, Gisselbrecht S, Dusanter-Fourt I, Porteu F. Control of thrombopoietin-induced megakaryocytic differentiation by the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4991–5000. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.9.4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schaeffer H J, Weber M J. Mitogen-activated protein kinases: specific messages from ubiquitous messengers. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:2435–2444. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmitt J M, Stork P J. Beta 2-adrenergic receptor activates extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs) via the small G protein rap1 and the serine/threonine kinase B-Raf. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25342–25350. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003213200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Seidel G M, Klinger M, Freissmuth M, Holler C. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase by the A(2A)-adenosine receptor via a rap1-dependent and via a p21(ras)-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:25833–25841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.36.25833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Stokoe D, Macdonald S G, Cadwallader K, Symons M, Hancock J F. Activation of Raf as a result of recruitment to the plasma membrane. Science. 1994;264:1463–1467. doi: 10.1126/science.7811320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun H, King A J, Diaz H B, Marshall M S. Regulation of the protein kinase Raf-1 by oncogenic Ras through phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, Cdc42/Rac and Pak. Curr Biol. 2000;10:281–284. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00359-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torti M, Ramaschi G, Sinigaglia F, Lapetina E G, Balduini C. Glycoprotein IIb-IIIa and the translocation of Rap2B to the platelet cytoskeleton. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4239–4243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Treisman R. Regulation of transcription by MAP kinase cascades. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:205–215. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80067-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tsukamoto N, Hattori M, Yang H, Bos J L, Minato N. Rap1 GTPase-activating protein SPA-1 negatively regulates cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18463–18469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van den Berghe N, Cool R H, Horn G, Wittinghofer A. Biochemical characterization of C3G: an exchange factor that discriminates between Rap1 and Rap2 and is not inhibited by Rap1A(S17N) Oncogene. 1997;15:845–850. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vossler R M, Yao H, York R D, Pan M G, Rim C S, Stork P J. cAMP activates MAP kinase and Elk-1 through a B-Raf- and Rap1-dependent pathway. Cell. 1997;89:73–82. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wan Y, Huang X Y. Analysis of the Gs/mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway in mutant S49 cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:14533–14537. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Whalen A M, Galasinski S C, Shapiro P S, Nahreini T S, Ahn N G. Megakaryocytic differentiation induced by constitutive activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1947–1958. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1947. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wojnowski L, Stancato L F, Larner A C, Rapp U R, Zimmer A. Overlapping and specific functions of Braf and Craf-1 proto-oncogenes during mouse embryogenesis. Mech Dev. 2000;91:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wolthuis R M, Franke B, van Triest M, Bauer B, Cool R H, Camonis J H, Akkerman J W, Bos J L. Activation of the small GTPase Ral in platelets. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2486–2491. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.York R D, Molliver D C, Grewal S S, Stenberg P E, McCleskey E W, Stork P J. Role of phosphoinositide 3-kinase and endocytosis in nerve growth factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase activation via Ras and Rap1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8069–8083. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.21.8069-8083.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.York R D, Yao H, Dillon T, Ellig C L, Eckert S P, McCleskey E W, Stork P J. Rap1 mediates sustained MAP kinase activation induced by nerve growth factor. Nature. 1998;392:622–626. doi: 10.1038/33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zimmermann S, Moelling K. Phosphorylation and regulation of Raf by Akt (protein kinase B) Science. 1999;286:1741–1744. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zutter M M, Painter A D, Yang X. The megakaryocyte/platelet-specific enhancer of the alpha2beta1 integrin gene: two tandem AP1 sites and the mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling cascade. Blood. 1999;93:1600–1611. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zwartkruis F J, Bos J L. Ras and Rap1: two highly related small GTPases with distinct function. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:157–165. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zwartkruis F J, Wolthuis R M, Nabben N M, Franke B, Bos J L. Extracellular signal-regulated activation of Rap1 fails to interfere in Ras effector signalling. EMBO J. 1998;17:5905–5912. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.20.5905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]