Abstract

Objective

Obtaining electronic patient data, especially from electronic health record (EHR) systems, for clinical and translational research is difficult. Multiple research informatics systems exist but navigating the numerous applications can be challenging for scientists. This article describes Architecture for Research Computing in Health (ARCH), our institution’s approach for matching investigators with tools and services for obtaining electronic patient data.

Materials and Methods

Supporting the spectrum of studies from populations to individuals, ARCH delivers a breadth of scientific functions—including but not limited to cohort discovery, electronic data capture, and multi-institutional data sharing—that manifest in specific systems—such as i2b2, REDCap, and PCORnet. Through a consultative process, ARCH staff align investigators with tools with respect to study design, data sources, and cost. Although most ARCH services are available free of charge, advanced engagements require fee for service.

Results

Since 2016 at Weill Cornell Medicine, ARCH has supported over 1200 unique investigators through more than 4177 consultations. Notably, ARCH infrastructure enabled critical coronavirus disease 2019 response activities for research and patient care.

Discussion

ARCH has provided a technical, regulatory, financial, and educational framework to support the biomedical research enterprise with electronic patient data. Collaboration among informaticians, biostatisticians, and clinicians has been critical to rapid generation and analysis of EHR data.

Conclusion

A suite of tools and services, ARCH helps match investigators with informatics systems to reduce time to science. ARCH has facilitated research at Weill Cornell Medicine and may provide a model for informatics and research leaders to support scientists elsewhere.

Keywords: data warehouse, secondary use, EHR, CTSA, data collection

INTRODUCTION

Obtaining electronic patient data, especially from electronic health record (EHR) systems, for clinical and translational research is difficult.1,2 Challenges include repurposing transactional (eg, care, billing) data for analytical purposes, finding and using the right electronic tools, understanding strengths and limitations of underlying data, obtaining regulatory approval, and maintaining compliance.3,4 These multiple factors comprise a complex socio-technical problem, and optimal approaches are unknown.

At Weill Cornell Medicine (WCM), the Research Informatics division of the Information Technologies & Services Department has operational responsibility for supporting the research enterprise with electronic patient data and tests hypotheses about how to best deliver service. Specifically, Research Informatics helps investigators obtain EHR data, collect novel measures, and integrate data from multiple sources. Through our experience supporting scientific workflows (eg, cohort discovery) with specific informatics tools (eg, i2b2), we have observed that science occurs not within informatics systems but rather in statistical software packages (eg, SAS, Stata, R) . With the goal of delivering to investigators data sets that are immediately amenable to statistical analysis, Research Informatics has established Architecture for Research Computing in Health (ARCH), a suite of tools and services for obtaining electronic patient data. Navigating numerous informatics software systems commonly available in academic medical centers—i2b2, REDCap, EHR reporting, PCORnet, and OpenSpecimen among others—can be challenging for investigators, and ARCH staff align scientists with the right tools with respect to study design, source systems, and cost so that researchers can accelerate data collection and reduce time to science.

Although scholars have criticized academic medical centers as “all breakthrough and no follow-through” for failing to change patient care based on clinical and translational research findings,1 the EHR provides a platform for investigators to translate novel models from the laboratory into clinical care through interventions—such as alerts and order sets—and subsequently collect data from the EHR to measures effects. Biomedical informatics is a critical component of this virtuous data-driven feedback loop known as the learning health system,5 and our institution has successfully deployed ARCH in support. To the best of our knowledge, the literature does not describe a comprehensive suite of tools and services to support investigators with electronic patient data. In this article, we describe ARCH to inform efforts at other institutions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Setting

WCM is a multispecialty group practice based on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in New York City. Consisting of more than 1600 physicians across 50 practice locations throughout the metropolitan area, WCM sees 3 million annual patient visits. WCM physicians are faculty members of Weill Medical College of Cornell University and hold admitting privileges to NewYork-Presbyterian (NYP), a long-standing clinical affiliate. A quaternary care institution, NYP has multiple hospital campuses where WCM attending physicians admit patients and educate medical trainees.

Across outpatient, inpatient, and emergency settings, WCM and NYP personnel document care using the Epic EHR system. In addition to WCM, doctors from Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons have admitting privileges to other NYP facilities and share the same Epic EHR system across all of WCM and NYP. Of note, prior to 2020, NYP used the Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager EHR system in inpatient and emergency settings with multiple interfaces exchanging data with Epic, which WCM physicians have used in outpatient areas since 2000. Through the Tripartite Request Assessment Committee comprised of WCM, NYP, and Columbia representatives, investigators can obtain data from the shared Epic enterprise EHR, the legacy Allscripts system, and other clinical and billing systems across the 3 institutions.

In addition to patient care, WCM serves education and research missions. Multiple WCM core facilities, institutes, and support units enable all phases of biomedical research. A National Institutes of Health (NIH)-funded Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) hub, the WCM Clinical and Translational Science Center (CTSC) provides biomedical research and education infrastructure, including support for biostatistics and informatics among other activities. Additionally, the Joint Clinical Trials Office (JCTO) of WCM and NYP supports research conducted between the 2 partner institutions. Financial support for Research Informatics includes subsidy from the CTSC and JCTO along with grants (eg, PCORnet, All of Us Research Program). Except where noted, Research Informatics services are made available free of charge to WCM investigators.

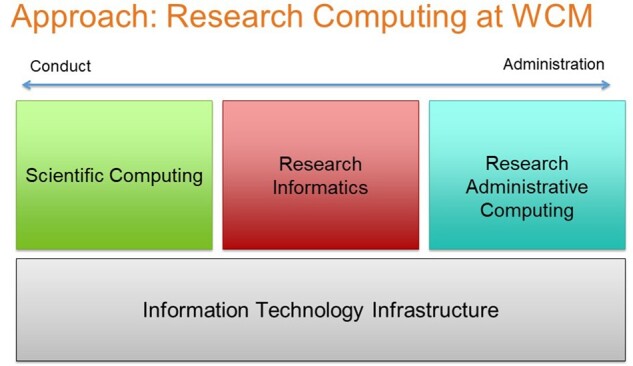

As detailed in Figure 1, the WCM Information Technologies and Services Department (ITS) provides foundational IT services (eg, infrastructure, project management) in support of the college’s tripartite mission along with 3 specialized divisions that provide services spanning the spectrum of research activities from conduct to administration. Notably, Scientific Computing provides high-performance computing for “omics” analyses and other “big data” challenges typically pursued by basic scientists and translational researchers, and Research Administrative Computing supports compliance and planning activities such as grants and contracts, Institutional Review Board, and clinical trials enrollment and compliance. Research Informatics brings together data and processes supported by these divisions as well as the patient care enterprise to enable the conduct of clinical and translational research.

Figure 1.

Weill Cornell Medicine Information Technologies and Services support for research computing.

Undergirding Research Informatics efforts to support investigators is an enterprise data warehouse for research called Secondary Use of Patients’ Electronic Records (SUPER).6 SUPER automates the acquisition and refresh of data from EHR systems maintained by clinical information technology groups including but not limited to Epic used across WCM, NYP, and Columbia; Allscripts previously used for NYP inpatient and emergency care overseen by WCM physicians; Athenahealth previously used at regional affiliate NYP/Queens; Standard Molecular genomic information system used for clinical genomic testing; and multiple specialty- and ancillary-focused systems for clinical and research purposes, including REDCap. After aggregating data from disparate sources, SUPER transforms data to multiple target data models, including common data models (CDMs) and custom research data marts, and executes a series of quality assurance scripts, including both locally developed testing queries and standardized data quality assessment tools.7 Prior to data transformation at the level of the EHR system, a customized terminology management interface6 ensures that incoming data are mapped to reference terminology. Along with unstructured data such as physician notes, structured data available in SUPER include but are not limited to diagnoses (ICD-9/10), procedures (CPT), laboratory results (LOINC), medications (RxNorm), and tumor registry codes (ICD-O-3) plus allergies, demographics, encounters, free-text notes, family history, social history, vital signs, and other domains. SUPER contains data for over 3 million patients who received care from WCM providers.

Research Informatics staff consists of data engineers and business analysts. Data engineers create and maintain ETL pipelines, write SQL code for custom EHR data extraction, and develop custom applications to support the research enterprise. Business analysts engage investigators to understand scientific objectives, collect requirements, match scientists with appropriate tools, ensure regulatory compliance, and document policies and procedures. Additionally, Research Informatics has service agreements with other ITS divisions—including but not limited to server infrastructure, information security, and project management—to obtain expertise and support from specialized personnel.

All WCM ITS staff, including the Research Informatics team, routinely use ServiceNow (Santa Clara, California), an information technology service management (ITSM) platform widely adopted within the field, to track customer engagement, provide service and support, and automate common IT workflows. Requesters seeking to use any tools or services from Research Informatics first begin by submitting a request in ServiceNow, allowing staff to document regulatory approval verification for specific research data requests but also gauge overall patterns in the utilization of services provided. Specifically, researchers submit what in the parlance of ITSM is termed a “request,” an instance of a form describing Institutional Review Board (IRB) protocol number, data of interest, sponsor, and other details. ARCH team members then review the request in ServiceNow and use existing system features, such as the option to leave “work notes,” to document the lifecycle of the request from intake to approval to execution.

System description

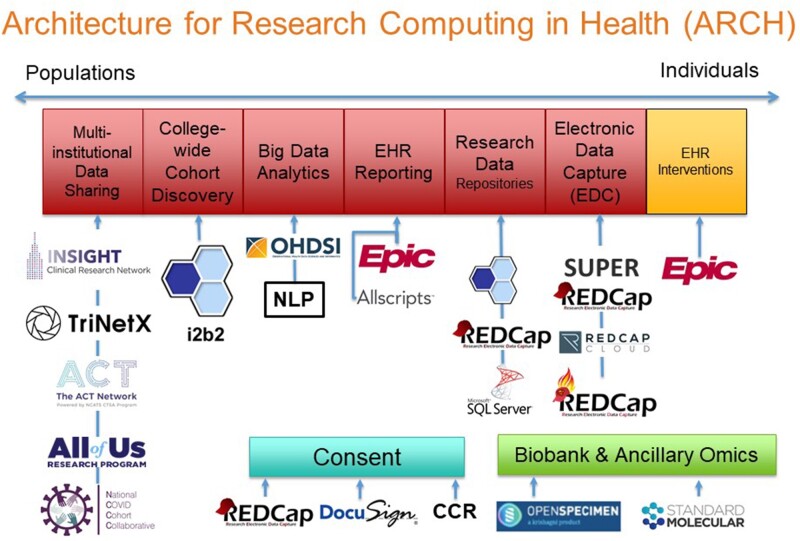

As illustrated in Figure 2, ARCH supports the spectrum of scientific activities from populations to individuals by enabling scientific workflows that manifest in specific systems. Drawing from the ARCH suite of tools and services, Research Informatics analysts work with investigators to understand how to support scientific projects with informatics tools with respect to study design, source systems, and cost.

Figure 2.

The Architecture for Research Computing in Health suite of tools and services supports multiple scientific workflows.

EHR reporting enables researchers to request customized, detailed reports of EHR data from outpatient, inpatient, and emergency settings through an iterative process with a database analyst. Data are available from Epic and the legacy Allscripts EHR system as well as other applications. Multiple clinical IT units from WCM and NYP provide EHR reporting services.

To facilitate patient cohort discovery preparatory to research, i2b28 provides investigators with a self-service tool to query EHR data for patients seen by WCM physicians. After determining a cohort of interest using i2b2 deidentified data, investigators with IRB approval can request identified medical record numbers. Notably, ARCH has demonstrated that investigators tend to use basic (eg, ICD-10 codes) rather than complex queries (eg, genomics), which suggests informatics teams may wish to focus on delivering basic rather than complex features in i2b2.9

To support big data analytics, the Observational Health Data Science and Informatics consortium’s Observational Medical Outcomes Partnership (OMOP) CDM10,11 enables access to almost all data from WCM and NYP EHR systems mapped to reference terminologies, such as ICD, CPT, LOINC, and RxNorm. OMOP enables data scientists to investigate local research questions and scale to multi-center studies. Additionally, OMOP provides standardized representations of patient data rather than proprietary vendor-defined representations. ARCH also enables natural language processing (NLP) using the UIMA-based Leo framework created by the Salt Lake City Veterans Administration12 as well as various Python packages.

In addition to supporting local studies, ARCH contributes EHR data to multi-institutional data sharing initiatives, including the NCATS Accrual to Clinical Trials (ACT) and National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C). Building on success with i2b2, ACT supports investigator-initiated clinical trials by helping scientists obtain patient counts preparatory to research from more than 45 CTSA hubs.13 To further pandemic response efforts, N3C aggregates EHR data to form a centralized national database in support of observational studies with extensive privacy and security controls,14 and ARCH contributes data on behalf of WCM. As the lead site of the INSIGHT Clinical Research Network, WCM aggregates EHR data for more than 8 million patients from all New York City academic medical centers, all of which are CTSA hubs, and enables participation in PCORnet, a network-of-networks for studies using EHR and other data sources.15 Together with Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Harlem Hospital Center, ARCH enables Weill Cornell participation in the NIH All of Us Research Program16 through novel informatics support for study coordinators17 that has also supported the PCORI-funded ADAPTABLE study.18 To support sponsor-initiated clinical trials, TriNetX enables biopharmaceutical sponsors to obtain deidentified counts of patients from CTSC EHR data and propose clinical trial opportunities.

Along with supporting research involving big data from the EHR, ARCH supports creation of small data sets using electronic data capture systems, especially REDCap.19 Building on the success of REDCap, ARCH has adopted the commercial REDCap Cloud to support studies requiring FDA oversight under 21 CFR Part 11. Additionally, to integrate clinical and research workflows, ARCH implemented SUPER REDCap, a generalizable middleware for connecting REDCap with an institution’s enterprise data warehouse using REDCap’s dynamic data pull feature.20 By prepopulating case report forms with data from the EHR, SUPER REDCap reduces data entry and saves time for research coordinators. ARCH also helped WCM become one of the first institutions globally to adopt SUPER REDCap on Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR), which makes REDCap accessible within the Epic EHR system.

To support specific information needs of different disease areas, ARCH provides custom research data repositories (RDRs). Containing identified data only for patients of interest to an investigator group,21 each RDR has 3 user interfaces to support scientific workflows—i2b2 for cohort discovery, SUPER REDCap for data collection, and Microsoft SQL Server Management Studio for data querying and analysis. RDRs contain rows-and-columns-level data sets customized to the needs of investigators and seek to support multiple studies. In contrast to the bulk of ARCH services that are available free of charge to investigators, RDRs require a $50 000 startup fee and $7500 annual fee. Although the charges do not fully recover costs, the fees ensure investigators “have skin in the game” and commit to partnering with Research Informatics for developing data marts.

To support electronic consent (eConsent) for research studies,22 ARCH successfully launched REDCap-based eConsent in multiple clinics.23 Additionally, for eConsent for studies requiring 21 CFR Part 11 compliance, ARCH has piloted DocuSign. More recently, ARCH has implemented a “consent to be contacted for research” within the Epic MyChart patient portal that allows patients to opt in to researchers other than their treating physicians to contact them about studies for which they may be eligible. To date, more than 100 000 patients have opted in since May 2019.

Additionally, ARCH launched biobank informatics at WCM with implementation of OpenSpecimen, which CTSA hubs and other academic medical centers use broadly.24 OpenSpecimen is integrated with the Epic EHR system and local data warehouse. ARCH also receives data from the Standard Molecular genomic information system—which contains variants of known and unknown significance performed as part of NYP/WCM clinical genomics testing—and makes data available through i2b2 and other tools.

In addition to supporting the acquisition of data, ARCH enables secure analysis via the Data Core.25 Consisting of a remote Windows desktop environment with productivity software (eg, Microsoft Office, Stata, R) and access restricted to specific study personnel, the Data Core allows investigators to analyze sensitive data—such as data from EHR systems, insurance payers, and other institutions—in accordance with IRB protocols, data use agreements, and other contracts. Notably, during the coronavirus disease 2019(COVID-19) pandemic stay-at-home orders, the Data Core enabled secure remote access to sensitive WCM COVID patient data for investigators at home without WCM-managed workstations.

Governance of ARCH consists of multiple mechanisms, including a steering committee comprised of senior WCM research and IT leaders who provide scientific and project prioritization guidance. On behalf of the WCM Privacy Office and WCM Institutional Review Board, ARCH serves as the honest broker of patient identity for research for the institution, with a particular focus on de-identification according to the HIPAA Safe Harbor method. For governance of clinical data for research originating from the EHR system shared across WCM, NYP, and Columbia, a data sharing agreement executed by the 3 institutions created the Alignment Committee on Oversight of Requests for Data (ACORD), which sets policies that the Tripartite Request Assessment Committee (TRAC) implements as processes for investigators to obtain data. ARCH functions as an agent of TRAC and ACORD for fulfilling data requests per institutional policy.

Evaluation

To assess and evaluate overall utilization of the ARCH suite of tools and services, we extracted data from ServiceNow and other institutional sources as necessary. First, we determined the yearly volume of total investigator consults and the total number of investigators supported through the ARCH suite of tools and services, identifying a consult as a single point of engagement (eg, an incident or request in ServiceNow) and utilizing built-in ServiceNow dashboard and reporting features to tabulate data. Then we evaluated the volume of support provided with respect to users, projects, and other associated metrics.

RESULTS

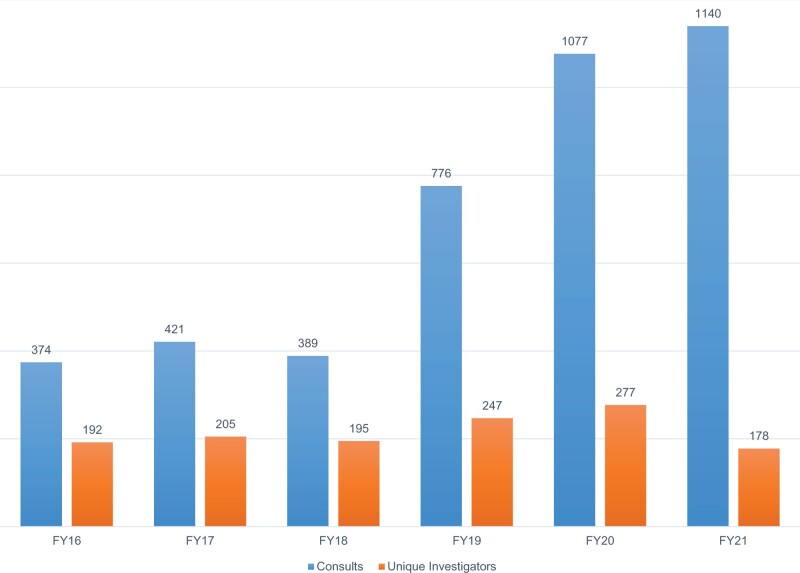

Since 2016, ARCH has supported 1294 unique investigators through 4177 consults. Year-to-year support of investigators has generally increased with major growth in custom RDRs occurring in 2019. A partial list of publications enabled by ARCH is available at https://its.weill.cornell.edu/guides/publications-using-arch-data.

As described in Table 1, investigators have used scientific functions enabled by ARCH tools to support numerous measures of research activity. Driven by clinical use cases, ARCH NLP efforts have supported acquisition of left ventricular ejection fraction,26 depression severity,27 suicidal ideation,28 and race and ethnicity29 among other elements from progress notes and pathology reports. ARCH infrastructure has also grown support of multi-institutional data sharing initiatives overtime to deliver regular data set updates (eg, quarterly, monthly, weekly) to PCORnet, ACT, N3C, All of Us Research Program, and TriNetX.

Table 1.

Volume of support provided through the Architecture for Research Computing in Health (ARCH) program

| ARCH function | Measure of support |

|---|---|

| EHR reporting |

|

| Cohort discovery: i2b2 |

|

| Big data analytics: natural language processing |

|

| Multi-institutional data sharing: TriNetX |

|

| Custom research data repositories |

|

| Electronic data capture: REDCap |

|

| Custom research data repositories |

|

| Biobank and ancillary omics: OpenSpecimen |

|

| Biobank and ancillary omics: Standard Molecular |

|

Of the 17 custom RDRs live as of July 2021, academic output includes but is not limited to that from Cardiac Imaging,30,31 Digestive Care,32 Mental Health,33,34 Myeloproliferative Neoplasms,35,36 Pulmonary and Critical Care,37,38 and Stroke.39 Largely driven by investigators with grant funding, RDR projects have generated data marts to address specific clinical research questions (eg, predictors of outcomes in hospitalized cirrhotic patients) while also yielding generalizable resources for the institution, such as an i2b2 eye exam ontology from Ophthalmology and surgical pathology report NLP from Urology. Notably, to support COVID-19 response efforts, ARCH provisioned the COVID Institutional Data Repository (IDR) using the RDR model to enable data-driven decision-making for not only research but also clinical care. To date, the COVID IDR has supported more than 13 publications.37,38,40–51 A data mart created as part of the Pulmonary and Critical Care RDR for sepsis research supported WCM action early in the COVID-19 pandemic.37

DISCUSSION

As sources of biomedical big data have proliferated, so too have informatics systems that support the spectrum of studies from populations to individuals, which we collectively refer to as ARCH. At our institution, the ARCH suite of tools and services has enabled investigators to navigate systems to obtain electronic patient data for research. By combining technical, regulatory, financial, and engagement activities, ARCH provides a framework that may inform efforts at other institutions to support scientists with electronic patient data.

The ARCH program initially took shape with a limited scope. Seeking to prioritize immediate investigator needs, we provisioned i2b2 to support cohort discovery, REDCap to support collection of research data, and EHR reporting, alongside custom RDRs, to support the analysis of rows-and-columns data sets. As the program evolved, we have expanded its offerings to include additional services, such as biospecimen informatics, big data analytics, and multi-institutional data sharing. Conceptualizing the structure of this portfolio as we have organized it here, in terms of specific tools designed to support specific scientific workflows, as well as the underlying infrastructure, has been helpful in framing ARCH’s role both with local investigators and with administrators seeking to allocate funding to support custom efforts. Other institutions may find the ARCH framework (Figure 3) useful for demonstrating to investigators the “alphabet soup” of tools and services available—and the benefit of consulting informatics staff for guidance—as well as site-specific substitutions of tools to support scientific workflows, such as Leaf52 instead of i2b2 for cohort discovery and OpenClinica53 instead of REDCap for data capture. Additionally, the modular ARCH framework can help institutions inform investigator communities of new product offerings, such as a novel multi-institutional data sharing consortium (eg, NIH postacute sequalae of COVID) and radiology or pathology image-specific services.

Figure 3.

Annual support of scientific activity through Architecture for Research Computing in Health. Consults are specific to each year, and a unique investigator may receive support in 1 or more years.

In expanding the ARCH program since its inception, we have learned multiple lessons both from internal operational analyses and from formal, structured evaluations of the use of ARCH tools and services. Some of these include the following:

Support for basic research workflows, such as cohort discovery and data collection, can often support the majority of investigator use cases. Tailoring efforts toward complex and theoretical use cases risks overprioritizing hypothetical and glamorous projects at the expense of the day-to-day work that constitutes the backbone of IT support for the research enterprise9 (eg, the provision of electronic case report forms, cohort discovery to facilitate manual chart review, and participation in multi-institutional consortia).

Custom-tailored data extraction trades specificity for scalability. Through developing customized RDRs that extract EHR data in an ad hoc fashion to support specific scientific use cases rather than a one-size-fits-all data warehouse, we have been able to address particular use cases and support studies that might not have otherwise been feasible. However, this approach requires individual engagement with stakeholders, and thus a linear scaling of staff is necessary to support an expanding portfolio of custom extraction efforts.

Standardized data models can support some but not all use cases. Reliance on tools such as the OMOP CDM affords flexibility and saves time—if an investigator seeks to extract a table with a row for each diagnosis a patient has been assigned, it is easier to pull this from an instance of OMOP’s CONDITION_OCCURRENCE table than from an EHR’s proprietary source data model, where diagnosis data may be stored in as many as 6 distinct tables. However, in many cases, specific studies require the extraction and analysis of data points that are not necessarily mappable to a standard data model, such as “I&O” flowsheets which document at the shift level patient fluid intake and excretion in intensive care units and cannot be easily modeled without exhaustive effort and a series of arbitrary data modeling decisions.

It takes a village of multiple specialists to quickly, accurately, and effectively extract and transform patient data for statistical analysis. Clinicians and trained informatics staff working together can easily generate large data sets, but early and frequent engagement with trained biostatisticians is also required to make sure that the data are appropriately structured and transformed to suit the analyses at hand.

Gaps in knowledge exist on both sides when clinicians and informaticians come together to extract patient data for research and must be accounted for. Informaticians may be ignorant of basic elements of clinical workflows, such as the fact that some departments may not order procedures in the EHR, but instead document them solely in free-text progress notes, leaving billers to review encounters and file charges after the fact. Conversely, clinicians may be unaware that some data elements that exist in the EHR are not structured and cannot be easily extracted or modeled, such as response/relapse/remission in cancer.

Generalized data quality assessment platforms cannot always accurately assess the fitness-for-purpose of an individual data set for an individual use case. Some data sets that pass a series of automated checks may be missing a critical element for a particular project. Conversely, other data sets that may trigger alerts from automated tools7 may be sufficient for some analytic use cases.

Investigator engagement and request triaging are critical elements of providing informatics support for the research enterprise. Especially at academic medical centers, a broad array of investigators with varying degrees of expertise and widely disparate areas of interest are constantly seeking to explore an ever-evolving array of hypotheses. Many of these investigators may reach out with a specific tool in mind, only to reveal upon examination that their use case necessitates a completely different approach (eg, REDCap instead of i2b2). Regardless of the outcome of an individual consult with a particular investigator, there is value in having a designated and centrally coordinated team responding to inquiries about the use of electronic patient data.

Grant funding for informatics infrastructure is useful but does not typically cover full costs. Although extramural awards provide a bolus of funds to start projects, support tapers over time, and institutional subsidy is critical for both launch and maintenance of operations. Agencies have an opportunity to better fund research informatics infrastructure at academic medical centers.

As the ARCH program has evolved, it has also encountered growing pains. In demonstrating the ability to deliver data that are of value to investigators, we have stimulated interest to the point that investigators now seek to obtain data on such a scale and with such frequency as to necessitate restructuring our underlying infrastructure, especially given existing funded commitments to regularly supply data to multi-institutional research networks, such as PCORnet and N3C. Future directions for expansion of the ARCH platform include migration to a cloud-based infrastructure, which will not obviate but may alleviate some of these issues. Additionally, providing support for direct EHR interventions through the FHIR framework54 may potentially allow ARCH to fully enable the virtuous cycle of the learning healthcare system.

The analysis presented in this article has limitations. Tracking publications ensuing from the use of ARCH tools and services remains a challenge. Although boilerplate text acknowledging federal support through the CTSA funding mechanism helps with prospective identification of new studies or papers using data gathered through ARCH, there is no guarantee that investigators will include this copy or that journals will have a place for it, rendering it difficult to accurately assess the full scope of work supported through this program. Additionally, some of the metrics we have chosen to represent utility and uptake of informatics tools at our institutions are imperfect at best. Query volume, in a tool like i2b2, may be less related to investigator interest in and engagement with the tool and more related to mechanistic difficulties in constructing a query that identifies the patient population of interest. We recognize that the approach outlined here may not be applicable to every institution, and that in some cases, exigencies of funding or organizational structure may necessitate the adoption of a different approach. Regardless, it is our hope that the lessons we have learned in developing and implementing this program may be of use to other institutions seeking to support the research enterprise with electronic patient data.

CONCLUSION

Supporting clinical and translational scientists with electronic patient data is challenging. Although multiple systems exist to enable data collection and analysis, navigating options can be difficult for faculty, staff, and students. A suite of tools and services, ARCH helps match investigators with informatics approaches with respect to study design, data sources, and cost. ARCH has successfully enabled research at Weill Cornell Medicine and may help informatics and research administrators support scientists elsewhere.

FUNDING

This study received support from the National Institutes of Health National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences through grant number UL1TR002384 (Weill Cornell) as well as support from the Joint Clinical Trials Office of Weill Cornell Medicine and NewYork-Presbyterian.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

TRC conceptualized ARCH and drafted the initial article. ETS contributed new content and major edits. SBJ, JP, JPL, and CLC participated in refining the ARCH concept and editing the article. CLC championed the ARCH effort.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Xiaobo Fuld, Prakash Adekkanattu, Marcos Davila, Ying Guo, Ferris Hussein, Joseph Kabariti, David Kraemer, Sasank Maganti, Ryan McGregor, Mohammad Taheri, Kenneth Zheng, Nivedita Chang, Sajjad Abedian, Catherine Ng, Stephanie Weiner, Alisha Gumber, Tiffany Ly, Cindy Chen, Julie Oetinger, Anthony DiFazio, Steven Flores, Jacob Weiser, Julian Schwartz, John Ruffing, Vinay Varughese, Mark Weiner, Scott Turner, Howard Sun, Adam Cheriff, Brett Fortune, Sameer Malhotra, J. Travis Gossey, Kimberly Baker, Olivier Elemento, Soumitra Sengupta, David Vawdrey, Maria Salpietro, Sean Pompea, Karthik Natarajan, Niloo Sobhani, Edward J. Schenck, Joseph Scandura, Manish Shah, Julianna Brouwer, Vanessa Blau, Zachary Grinspan, and Rainu Kaushal.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

T.R.C. is a guest associate editor of the JAMIA special issue on best practices for patient data repositories, and he recuses himself from consideration of this article for publication.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hersh WR, Cimino J, Payne PRO, et al. Recommendations for the use of operational electronic health record data in comparative effectiveness research. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2013. 8; 1 (1): 1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hersh WR, Weiner MG, Embi PJ, et al. Caveats for the use of operational electronic health record data in comparative effectiveness research. Med Care 2013; 51 (8 Suppl 3): S30–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Payne PRO, Johnson SB, Starren JB, Tilson HH, Dowdy D.. Breaking the translational barriers: the value of integrating biomedical informatics and translational research. J Investig Med 2005; 53 (4): 192–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hripcsak G, Bloomrosen M, FlatelyBrennan P, et al. Health data use, stewardship, and governance: ongoing gaps and challenges: a report from AMIA’s 2012 Health Policy Meeting. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014; 21 (2): 204–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Grumbach K, Lucey CR, Johnston SC.. Transforming from centers of learning to learning health systems: the challenge for academic health centers. JAMA 2014; 311 (11): 1109–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sholle ET, Kabariti J, Johnson SB, et al. Secondary use of patients’ electronic records (SUPER): an approach for meeting specific data needs of clinical and translational researchers. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2017; 2017: 1581–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huser V, DeFalco FJ, Schuemie M, et al. Multisite evaluation of a data quality tool for patient-level clinical data sets. EGEMS (Wash DC) 2016; 4 (1): 1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Murphy SN, Weber G, Mendis M, et al. Serving the enterprise and beyond with informatics for integrating biology and the bedside (i2b2). J Am Med Inform Assoc 2010; 17 (2): 124–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sholle ET, Cusick M, Davila MA, Kabariti J, Flores S, Campion TR.. Characterizing basic and complex usage of i2b2 at an Academic Medical Center. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2020; 2020: 589–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Overhage JM, Ryan PB, Reich CG, Hartzema AG, Stang PE.. Validation of a common data model for active safety surveillance research. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2012; 19 (1): 54–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hripcsak G, Duke JD, Shah NH, et al. Observational Health Data Sciences and Informatics (OHDSI): opportunities for observational researchers. Stud Health Technol Inform 2015; 216: 574–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Patterson OV, Freiberg MS, Skanderson M, J Fodeh S, Brandt CA, DuVall SL.. Unlocking echocardiogram measurements for heart disease research through natural language processing. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2017; 17 (1): 151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Visweswaran S, Becich MJ, D’Itri VS, et al. Accrual to clinical trials (ACT): a Clinical and Translational Science Award Consortium Network. JAMIA Open 2018; 1 (2): 147–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haendel MA, Chute CG, Bennett TD, et al. ; N3C Consortium. The National COVID Cohort Collaborative (N3C): rationale, design, infrastructure, and deployment. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021; 28 (3): 427–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kaushal R, Hripcsak G, Ascheim DD, et al. ; NYC-CDRN. Changing the research landscape: the New York City Clinical Data Research Network. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014; 21 (4): 587–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16., Denny JC, Rutter JL, Goldstein DB, Philippakis A, Smoller JW, et al. ; All of Us Research Program Investigators. The “All of Us” research program. N Engl J Med 2019. ; 381 (7): 668–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Turner SP, Pompea ST, Williams KL, et al. Implementation of informatics to support the NIH all of us research program in a healthcare provider organization. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2019; 2019: 602–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Campion TR, Pompea ST, Turner SP, Sholle ET, Cole CL, Kaushal R.. A method for integrating healthcare provider organization and research sponsor systems and workflows to support large-Scale Studies. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2019; 2019: 648–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG.. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)–a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42 (2): 377–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Campion TR, Sholle ET, Davila MA.. Generalizable middleware to support use of redcap dynamic data pull for integrating clinical and research data. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2017; 2017: 76–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sholle ET, Davila MA, Kabariti J, et al. A scalable method for supporting multiple patient cohort discovery projects using i2b2. J Biomed Inform 2018; 84: 179–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chen C, Lee P-I, Pain KJ, Delgado D, Cole CL, Campion TR.. Replacing paper informed consent with electronic informed consent for research in academic medical centers: a scoping review. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2020; 2020: 80–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chen C, Turner SP, Sholle ET, et al. Evaluation of a REDCap-based Workflow for Supporting Federal Guidance for Electronic Informed Consent. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2019; 2019: 163–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McIntosh LD, Sharma MK, Mulvihill D, et al. caTissue Suite to OpenSpecimen: developing an extensible, open source, web-based biobanking management system. J Biomed Inform 2015; 57: 456–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Oxley PR, Ruffing J, Campion TR, Wheeler TR, Cole CL.. Design and implementation of a secure computing environment for analysis of sensitive data at an academic medical center. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018; 2018: 857–66. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Johnson SB, Adekkanattu P, Campion TR, et al. From sour grapes to low-hanging fruit: a case study demonstrating a practical strategy for natural language processing portability. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2018; 2017: 104–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Adekkanattu P, Sholle ET, DeFerio J, Pathak J, Johnson SB, Campion TR.. Ascertaining depression severity by extracting Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) scores from clinical notes. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018; 2018: 147–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cusick M, Adekkanattu P, Campion TR, et al. Using weak supervision and deep learning to classify clinical notes for identification of current suicidal ideation. J Psychiatr Res 2021; 136: 95–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sholle ET, Pinheiro LC, Adekkanattu P, et al. Underserved populations with missing race ethnicity data differ significantly from those with structured race/ethnicity documentation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2019; 26 (8-9): 722–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Singh G, Hussain Y, Xu Z, et al. Comparing a novel machine learning method to the Friedewald formula and Martin-Hopkins equation for low-density lipoprotein estimation. PLoS One 2020; 15 (9): e0239934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pandey M, Xu Z, Sholle E, et al. Extraction of radiographic findings from unstructured thoracoabdominal computed tomography reports using convolutional neural network based natural language processing. PLoS One 2020; 15 (7): e0236827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Khan U, Ho K, Hwang EK, et al. Impact of use of antibiotics on response to immune checkpoint inhibitors and tumor microenvironment. Am J Clin Oncol 2021; 44: 247–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Deferio JJ, Levin TT, Cukor J, et al. Using electronic health records to characterize prescription patterns: focus on antidepressants in nonpsychiatric outpatient settings. JAMIA Open 2018; 1 (2): 233–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhang Y, Wang S, Hermann A, Joly R, Pathak J.. Development and validation of a machine learning algorithm for predicting the risk of postpartum depression among pregnant women. J Affect Disord 2021; 279: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sholle E, Krichevsky S, Scandura J, Sosner C, Campion TR.. Lessons learned in the development of a computable phenotype for response in myeloproliferative neoplasms. IEEE Int Conf Healthc Inform 2018; 2018: 328–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Fu JT, Sholle E, Krichevsky S, Scandura J, Campion TR.. Extracting and classifying diagnosis dates from clinical notes: a case study. J Biomed Inform 2020; 110: 103569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Schenck EJ, Hoffman KL, Cusick M, Kabariti J, Sholle ET, Campion TR.. Critical carE Database for Advanced Research (CEDAR): An Automated Method to Support Intensive Care Units with Electronic Health Record Data. J Biomed Inform 2021; 118: 103789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Schenck EJ, Hoffman K, Oromendia C, et al. A comparative analysis of the respiratory subscore of the sequential organ failure assessment scoring system. Annals Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18 (11): 1849–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kamel H, Okin PM, Merkler AE, et al. Relationship between left atrial volume and ischemic stroke subtype. Ann Clin Transl Neurol 2019; 6 (8): 1480–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Goyal P, Choi JJ, Pinheiro LC, et al. Clinical Characteristics of Covid-19 in New York City. N Engl J Med 2020; 382 (24): 2372–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Merkler AE, Parikh NS, Mir S, et al. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol 2020; 77 (11): 1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Schenck EJ, Hoffman K, Goyal P, et al. Respiratory mechanics and gas exchange in COVID-19-associated respiratory failure. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2020; 17 (9): 1158–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lin E, Lantos JE, Strauss SB, et al. Brain imaging of patients with COVID-19: findings at an academic institution during the height of the outbreak in New York City. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2020; 41 (11): 2001–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Goyal P, Ringel JB, Rajan M, et al. Obesity and COVID-19 in New York City: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173 (10): 855–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Akchurin O, Meza K, Biswas S, et al. COVID-19 in patients with CKD in New York City. Kidney360 2021; 2 (1): 63–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lee JR, Silberzweig J, Akchurin O, et al. Characteristics of acute kidney injury in hospitalized COVID-19 patients in an Urban Academic Medical Center. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 16 (2): 284–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Butler D, Mozsary C, Meydan C, et al. Shotgun transcriptome, spatial omics, and isothermal profiling of SARS-CoV-2 infection reveals unique host responses, viral diversification, and drug interactions. Nat Commun 2021; 12 (1): 1660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Witenko CJ, Littlefield AJ, Abedian S, An A, Barie PS, Berger K.. The safety of continuous infusion propofol in mechanically ventilated adults with coronavirus disease 2019 [published online ahead of print May 14, 2021]. Ann Pharmacother 2021; doi: 10.1177/10600280211017315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Shah MA, Mayer S, Emlen F, et al. Clinical screening for COVID-19 in asymptomatic patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open 2020; 3 (9): e2023121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hajifathalian K, Krisko T, Mehta A, et al. ; WCM-GI Research Group. Gastrointestinal and hepatic manifestations of 2019 novel coronavirus disease in a large cohort of infected patients from New York: clinical implications. Gastroenterology 2020; 159 (3): 1137–1140.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hajifathalian K, Sharaiha RZ, Kumar S, et al. Development and external validation of a prediction risk model for short-term mortality among hospitalized U.S. COVID-19 patients: a proposal for the COVID-AID risk tool. PLoS One 2020; 15 (9): e0239536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dobbins NJ, Spital CH, Black RA, et al. Leaf: an open-source, model-agnostic, data-driven web application for cohort discovery and translational biomedical research. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2020; 27: 109–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Löbe M, Meineke F, Winter A.. Scenarios for using openclinica in academic clinical trials. Stud Health Technol Inform 2019; 258: 211–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lenert LA, Ilatovskiy AV, Agnew J, et al. Automated Production of Research Data Marts from a Canonical Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resource (FHIR) Data Repository: applications to COVID-19 research. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2021; 28: 1605–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.