Significance

Why are so many postwar experiments in international governance now being challenged? We consider how polarization of political parties and stakeholders on the issues addressed by international environment agreements affects commitment to those agreements. We also consider how changes in national obligations under agreements affect polarization. We show that while there is good cause to think that party polarization is associated with reduced support for international agreements, stakeholder engagement that penalizes parties adopting positions too distant from their own has an important moderating affect. An understanding of the way that the political environment conditions national commitment to international agreements may, in turn, help in understanding the way in which national decisions ramify through the international treaty system.

Keywords: polarization, international environmental agreements, spatial competition

Abstract

The network of international environmental agreements (IEAs) has been characterized as a complex adaptive system (CAS) in which the uncoordinated responses of nation states to changes in the conditions addressed by particular agreements may generate seemingly coordinated patterns of behavior at the level of the system. Unfortunately, since the rules governing national responses are ill understood, it is not currently possible to implement a CAS approach. Polarization of both political parties and the electorate has been implicated in a secular decline in national commitment to some IEAs, but the causal mechanisms are not clear. In this paper, we explore the impact of polarization on the rules underpinning national responses. We identify the degree to which responsibility for national decisions is shared across political parties and calculate the electoral cost of party positions as national obligations under an agreement change. We find that polarization typically affects the degree but not the direction of national responses. Whether national commitment to IEAs strengthens or weakens as national obligations increase depends more on the change in national obligations than on polarization per se. Where the rules governing national responses are conditioned by the current political environment, so are the dynamic consequences both for the agreement itself and for the network to which it belongs. Any CAS analysis requires an understanding of such conditioning effects on the rules governing national responses.

International environmental law is supported by a network of treaties—bilateral and multilateral agreements between sovereign nation states addressing one or more environmental issues of common interest. The International Environmental Agreements (IEA) Database currently lists 3,600 IEAs, 80% being bilateral, 10% involving 10 or fewer signatories, and less than 1% involving 100 or more signatories (1). The network of IEAs has been characterized as a complex adaptive system (CAS) in which, in the absence of international controls, simple behavioral rules at the national level give rise to complex international adaptive dynamics (2). An analysis of the structure revealed by cross-references between the 20% of treaties that involve more than two signatories found that the network had evolved from a single node (treaty) in 1857 to 747 nodes (treaties) with 1,001 directed links by 2012—with waves of activity following the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (the Stockholm Conference) and the 1992 Earth Summit (the Rio Conference) (3).

A CAS approach offers a different perspective on the dynamics of the network of IEAs to the dominant fragmentation approach (4). Fragmentation supposes a process in which issue-specific IEAs, negotiated by any number of nation states, differentially limit the behavior of local, national, or regional parties in ways that often conflict with both their interests and obligations on other issues. Fragmentation is argued to privilege national interest on single issues, compromising both coordination and cooperation on a range of interconnected environmental problems (5). The CAS approach, by contrast, sees decentralized interactions between nation states pursuing their own agendas on particular issues as a potential source of seemingly coordinated adaptive behaviors across the network (6). As in polycentric approaches, where heterogeneity is argued to lead (through innovation and experimentation) to alignment with collective goals (7), a CAS approach to IEAs anticipates the emergence of herd-like adaptations to changes in environmental conditions as a function of the topology of the system. Whereas fragmentation implies a flat nonhierarchical structure, complexity is argued to imply a modular hierarchical structure. The dynamics of the system then depend on both the dynamics of the network itself and the dynamics of the institutions at the nodes of the network—individual treaties or clusters of tightly linked treaties (6).

At the core of the CAS approach are the simple rules that, when applied by agents in an uncoordinated way, may give rise to seemingly coordinated collective behaviors. As a first approximation, the terms of IEAs might be thought to provide those simple rules. Unfortunately, there is no obvious way to derive common rules from the stated goals of IEAs. Moreover, while cross-references in the texts of distinct multilateral agreements suggest the existence of a network based on substantive links, the structure of those substantive links is as yet ill defined. The reality identified in the fragmentation literature is that the softness of the law embodied in most international agreements—the lack of enforcement or penalties—makes compliance largely optional (5). Whether compliance relates to the standing rules embodied in treaties or to the decisions of arbiters such as the International Court of Justice, it depends on national perceptions of the net benefits of a system of rule-based behavior (8). It has long been recognized that nation states do not want enforcement of agreements if they might themselves be noncompliant (9).

In practice, the rules informing IEA signatories’ reactions to changing environmental conditions involve a complicated national calculus of costs and benefits to multiple constituencies. In some cases, this generates a common response. In others, it does not. For example, changes in the conditions confronted by member states of the European Union (EU) over the last two decades have strained willingness to comply with EU agreements. Nevertheless, only the United Kingdom has opted to withdraw from the Union (10, 11). By contrast, while the COVID-19 pandemic might have been expected to generate a coordinated international disease control effort under the World Health Organization, the immediacy of the threat to national populations led to an almost wholly decentralized response to the pandemic (12).

In this paper, we explore the rules that govern the responses of IEA signatories to changes in environmental conditions. We are not concerned with the effect of the topology of the network on dynamics given a set of rules, but with the nature of the rules themselves and the way they affect the dynamics of individual nodes. More particularly, we wish to understand how polarization at the national level affects the response a nation state makes to changes in the conditions affecting IEAs. The context to our study is arguments that polarization of opinion on the benefits of international cooperation has reduced the willingness of political parties in individual nations both to contribute to public goods or common causes that span groups (13) and to cooperate at supranational levels (14). This may well reflect changes in geopolitical, economic, and demographic conditions. The end of the Cold War, for example, altered perceptions about the benefits of closer international cooperation with allies (15). More generally, polarization on the issues addressed by international agreements is argued to have weakened national commitment to those agreements (16, 17). Understanding the rules governing national adaptation to changes in the conditions addressed by individual IEAs is a precondition for developing a CAS approach to the IEA network itself.

We accordingly abstract from the dynamic properties of the network to consider how polarization at the national level affects the willingness of political parties to commit to particular treaties. Specifically, we consider how polarization of stakeholders (consisting of both the electorate and special interest groups) and political parties affects a nation's willingness either to enter into IEAs or to comply with agreements as they evolve. We argue that the position taken by political parties on IEAs depends on perceptions of the benefits and costs involved, where the currency of costs and benefits is electoral support of parties—including the resources offered to political parties that can leverage electoral support.

Political parties are assumed to engage in decisions affecting the evolution of individual IEAs in ways described below. However, while our analysis is grounded in the canonical electoral model due to Downs (18), and while we assume that political parties take account of the electoral consequences of the position they take on those IEAs, we are not concerned with the electoral process itself. If national responses to changes in the conditions addressed by international treaties depend on the engagement of political parties, as they do in many democracies, then the calculus of costs and benefits will include (but are not limited to) any future electoral consequences.

The decision a nation state makes to sign or ratify new agreements, or to renew, extend, or curtail existing agreements, reflects both the rules laid down in the agreement itself and the procedures applied to the management of international treaties in that state. For example, states differ in the degree to which responsibility for the ratification or amendment of treaties is shared between political parties. If decisions rest solely with the party currently in power, the decisions taken by both parties would be expected to differ from those taken if decisions require consensus or at least a degree of interparty collaboration. The two-thirds supermajority required for Senate ratification of international agreements entered into by the United States, for example, gives the opposition a significant role in the decision process on full US treaties. By contrast, executive treaties that require no congressional action may take little account of the views of opposition parties (19). In other countries, coalition governments have frequently resulted in power sharing on foreign policy issues (20). In the first decade of this century, for example, coalition cabinets determined foreign policy in 32 countries in Europe, 7 countries in Asia and the South Pacific, and 5 countries in the Middle East and Africa (21).

The electoral cost of the decisions taken by political parties on a particular treaty depends on the distance between the position of the party and the position of stakeholders, the distance between party positions, and compliance/noncompliance with the terms of the agreement. We expect the cost to be sensitive to polarization of the electorate and special interest groups, which we take to be reflected in the modality of distribution of opinion on the issue. The Downs model of voting that drew on Hotelling’s 1929 study of stability in competition (22) assumed that party platforms would be tailored to attract the greatest number of voters (18) and hence would reflect the distribution of voters’ opinions on that issue (23). As long as the distribution of voters’ opinions was single peaked, Downs concluded that political parties’ platforms cluster around the mode. For a bimodal distribution of voters, however, he expected that political parties would converge on each of the two modes (24).

In the United States, for example, while the distribution of opinion on many issues may have been unimodal in the 1960s, it has subsequently become increasingly bimodal as noninstrumental social preferences have become ever more politically salient. New federal legislation on matters that had previously been in the purview of the states aimed to end racial segregation, whereas new laws permitting abortion, pornography, divorce, and same-sex marriage, while restricting prayer in schools, threatened the social status of many in the South and in rural regions of the country and offended many Catholics and evangelicals (25). Although polarization of the electorate extends to some issues addressed by IEAs, such as climate, many environmental issues are of more concern to special interest groups—corporate interests seeking advantage for their particular industry and firm, labor unions seeking enhanced wages and working conditions, along with environmental issue-focused nongovernmental organizations and consumer groups. Corporate interests have strengthened relative to labor unions due, in part, to the decline in the manufacturing sector, access to state-provided welfare benefits that once were only available to union members, right-to-work laws, and greater corporate campaign contributions following the Citizens United decision. The net effect has been an increase in the resources committed to issues of special interest to corporations and a decrease in the resources committed to issues of interest to labor unions, seemingly reducing polarization among donors (a trend that explains why the last two Democratic administrations adopted many Republican-friendly policies) (26).

To capture the relation between polarization and the positions taken by political parties on international agreements, we consider a stylized two-party system. Each party is assumed to choose both a position on and the level of commitment it is willing to make to agreements—given the positions of the other party and of stakeholders. Party positions are assumed to be a function of the net electoral benefits of participation and reflect power-sharing arrangements as well as the positions taken by stakeholders. The level of commitment parties are willing to make may be thought of as the political capital they are prepared to invest in securing their position on the agreement. In the United States, the many agreements that have languished for years in the Senate without being ratified reflect the fact that neither party is willing to make a sufficient commitment in terms of either legislative time or political capital. The political opportunity cost of ratification is too high (27).

Our model architecture has its roots in Hotelling’s treatment of competition in duopoly (22) and the canonical voter model developed by Downs (24) on the basis of the Hotelling model. The Downs model has been extended in different ways to address the problem of polarization in the electoral process. Examples include the polarization effects of income inequality (28), extremism among entering candidates (29, 30), the lagged consequences of the margin of victory (31), and the relation between platforms and valence (32). In this paper, we are not concerned with the electoral process itself but with the electoral costs of decisions taken outside that process. Our model draws most directly on the models of spatial Cournot competition (33, 34) that underpin subsequent analysis of location choice in the economics literature. Since we focus on the costs of a decision on a single issue, the long-standing objection to the unidimensionality of the Downs model (23) does not apply.

The space occupied by political parties and the stakeholders whose views they represent is the opinion they take on the issue addressed by particular IEAs. Stakeholders are distributed in opinion space, and political parties choose where to locate in that space. Our measures of polarization respect the two characteristics most frequently encountered in attempts to quantify the phenomenon: a reduction in within-group dispersion and an increase in across-group distances (35). Polarization among stakeholders is indicated by the bimodality of their distribution in opinion space. Polarization of parties is indicated by the distance between their locations in the same space.

We assume that opinion space on international agreements is [0,1], with zero indicating no support for the agreement and 1 indicating full support, and that the location of parties in that space, , is such that . That is, party 1 is never more supportive of the agreement than party 2. Parties are assumed to maximize a net benefit function in which the currency is the electoral support secured directly or indirectly from stakeholders by choosing a position in opinion space and the commitment they are willing to make to secure that position, . The benefits of party 1’s commitment to the agreement depend on the contributions by both parties and takes the form in which denotes the maximum support stakeholders are willing to offer in exchange for commitment to an agreement, and the relative value of reflects power-sharing arrangements. if power is shared evenly between parties 1 and 2, and if power is shared asymmetrically. In what follows, we assume that party 1 is in power, implying that .

We extend the spatial model to capture both the effect of background polarization (polarization on issues other than those addressed by agreements) and the valence issues surrounding national compliance with international agreements. We suppose that the electoral costs of commitment are increasing in three additive measures. The first is a measure of the distance between a party’s location in opinion space and the location of stakeholders in that space, , in which is the electoral cost of the distance between the position taken by the party and the positions taken by the electorate, is the absolute value of the distance between opinions, and , the probability density function of the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, weights each position by the share of the electorate holding that position. The second is a measure of the closeness of the parties’ own locations in opinion space, , in which is the proximity of the positions taken by the two parties, and is the electoral cost of proximity. The third is a measure of noncompliance with national obligations under the agreement, , in which is the commitment required to meet the national obligation in renewal period r, is the gap between national obligation and national commitment, and is the electoral cost of noncompliance. The net electoral benefits of the decisions made by the party on an international agreement accordingly take the following form:

The last two measures extend the spatial model in important ways. reflects an electoral cost imposed on parties that fail to differentiate their position on an issue from that or other parties. One reason for this is spatial contagion: parties adopting proximate positions on an issue can lose if those positions are seen to fail whether or not they are in office (36). reflects an electoral penalty for failing to comply with commitments made under international agreements. Unlike the first two measures, noncompliance is a valence or reputational issue (23) that has been shown, empirically, to influence both parties and the electorate (37). Note that if the electoral costs of party similarity and noncompliance are zero, we are left with a core spatial model.

We take two cases of stakeholder polarization. In the first, individuals are assumed to have no basis on which to form opinions—as might be true of a new agreement on an unfamiliar issue. In this case, we assume the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space to be uniform, the density function on being . In the second, we suppose that stakeholders are bimodally distributed in opinion space, the density function on being .

We model the strategies pursued by political parties as a two-stage game. Each party first chooses its location in opinion space, and then selects the commitment it is willing to make to the agreement given 1) the terms of the agreement, 2) the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, 3) the position taken by the other party, and 4) power-sharing arrangements.

The key features of international agreements reflected in the model are that they are generally unenforceable and that they evolve over time. The first feature implies that contractual obligations of member states have the status of soft law and are implemented via strategic interactions between signatories rather than by appeal to some higher authority. The second feature implies that the terms of agreements, and the obligations a country has under those agreements, are subject to change as an emergent property of the network of treaties. Change may follow regular review (as occurred with General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade), the negotiation of additional protocols (as occurred with the Convention on Climate Change), or the renegotiation of the original terms of agreement (as occurred with the North American Free Trade Agreement). But it may also be an emergent property of rule ambiguity that allows countries to select their preferred interpretation, and to determine which agreements lose or gain salience (38).

The significance of these features of international agreements is, first, that national obligations under particular agreements may be expected to change and, second, that individual countries face a political choice to comply with the terms of agreements or not, depending on current perceptions of the advantages they offer and the other factors affecting party decisions. By modeling the strategic behavior of parties, and by testing their response to variation in the electoral costs of behavior in a series of numerical experiments, we are able to show how polarization affects both the position that parties take and their willingness to commit to agreements. We then discuss how our results aid understanding of the empirical evidence for the weakening of various instruments of postwar international governance.

Results

We report results relating both to the position taken by political parties on the issues addressed by international agreements and to the commitment they are willing to make to those agreements. Commitment by each party at the Nash equilibrium is given by:

It follows immediately that commitment by the party is decreasing in the distance between the position it takes and the positions taken by the electorate, , and is increasing in the distance between the position taken by the other party and the positions taken by the electorate, . That is, . Commitment by the party is also decreasing in the electoral cost of stakeholder distance, , and party similarity, : . The impact of a change in the electoral cost of noncompliance on commitment is, however, less obvious. Since

the direction and magnitude of the impact is sensitive both to the probability density function of the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, the positions taken by political parties, and the set of parameter values.

Since we do not have closed form solutions for the location of parties in opinion space, we use a numerical approach to explore the sensitivity of location choice (and hence party commitment) to variation in parameter values. As a baseline, we take the case where neither stakeholders nor parties are polarized. Specifically, we assume that 1) stakeholders are distributed uniformly in their opinions about the issue addressed by an international agreement; 2) stakeholders do not penalize parties for adopting positions different from their own; 3) parties do not gain support by differentiating themselves from each other; and 4) there is a degree of power sharing—both parties contribute to the realization of an agreement. For a standard uniform distribution of stakeholders, we found that both parties adopt the same position, equidistant from the extremes [0] and [1] in opinion space. We also found that once the choice has been made neither party has an incentive to change its position. Formally, the shared position of the parties in opinion space is a subgame perfect equilibrium of the two-stage Cournot competition between the parties: the parties’ chosen position is a Nash equilibrium of the second stage of the game (the subgame in which parties determine the level of commitment they are willing to make). In these circumstances, parties hold their position whether or not stakeholders reduce support if the positions adopted by the parties differ from their own opinions.

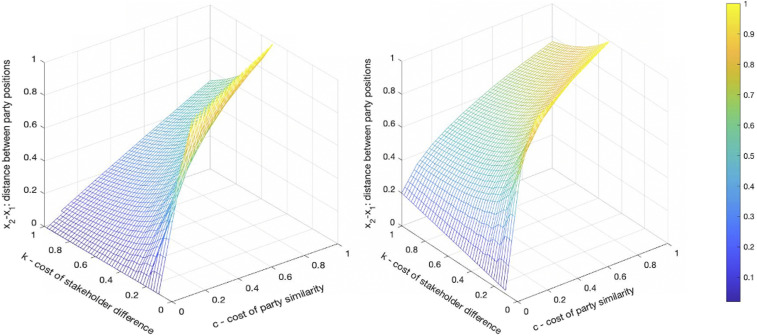

Against this baseline, we consider the implications of relaxing assumptions 1 to 3—allowing a nonuniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space and changes in the electoral costs of differences between the positions of parties and stakeholders the similarity between party positions. We later consider the implications of exogenously driven changes in the commitment required to meet the terms of an agreement and the electoral cost of failing to comply with national obligations under an agreement. As a first step, however, we relax the assumption that there is no cost either to differences between the positions taken by parties and stakeholders or to the similarity between party positions. That is, we suppose that each party may face an electoral cost if it adopts a position too far from stakeholders and too close to that of the other party. We wish to understand how the existence of electoral costs affects the positions taken by parties on the issues addressed by international agreements. Fig. 1 reports differences between party locations in opinion space, , against the electoral cost of the distance between the position taken by political parties and the positions taken by stakeholders, , and the electoral cost of the similarity between the positions taken by both parties, . The left-hand panel assumes that stakeholders are distributed uniformly in opinion space. The right-hand panel assumes that they are distributed bimodally.

Fig. 1.

The distance between positions taken by parties on an agreement at the Nash equilibrium as a function of the electoral costs of both the distance between party and stakeholder positions and the similarity between party positions. The Left panel reports results for a uniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space. The Right panel reports results for a bimodal distribution.

For a standard uniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, and if there is no cost of party similarity, both parties converge on a location midway between the extremes. Increasing the cost of party similarity has the expected effect of widening the gap between the parties, but increasing the cost of distance from stakeholders has the opposite effect. For a bimodal distribution of stakeholders, and if there is no cost to party similarity, parties locate away from the midpoint. Increasing the cost of party similarity again widens the gap between parties (although the effect is less pronounced than it is under a uniform distribution), and increasing the cost of distance from stakeholders again has the opposite effect. The greater the electoral cost of distance from stakeholders, the less the distance between party positions at the Nash equilibrium—even if stakeholders are themselves polarized on the issue. That is, party polarization on the issue falls as the cost of differences in the positions taken by the parties and the electorate rises. The reduction is strongest where stakeholders are distributed uniformly and weakest where stakeholders are distributed bimodally. If stakeholders are themselves polarized on the issue addressed by the agreement, there is less pressure on parties to narrow the gap between them.

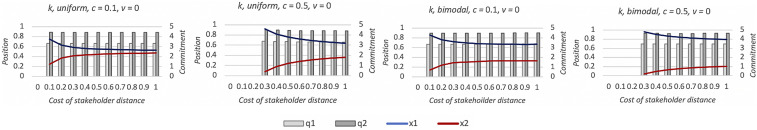

As expected from the general form of the commitment equations at the Nash equilibrium above, we found that an increase in the electoral cost of stakeholder difference is associated with a reduction in the commitment parties are willing to make. However, since an increase in the electoral cost of stakeholder difference also induces a reduction in distance between party positions, the net effect on commitment is small. This is illustrated in Fig. 2, which reports the impact of a variation in the cost of distance from stakeholders on both party positions and commitment for low () and medium () costs to party similarity. As in Fig. 1, it shows the tendency for an increasing cost of distance from stakeholders to drive parties to adopt positions closer to the median voter. But it also shows the limited impact of the cost of distance to stakeholders on party commitment when there are no electoral costs to noncompliance with the terms of the agreement.

Fig. 2.

Party polarization and willingness to commit to international agreements at the Nash equilibrium as a function of the electoral cost of distance from stakeholders. The Left two panels report results for a uniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space and for two levels of the electoral cost of party similarity, . The Right two panels report results for a bimodal distribution and for the same levels of . In all cases, .

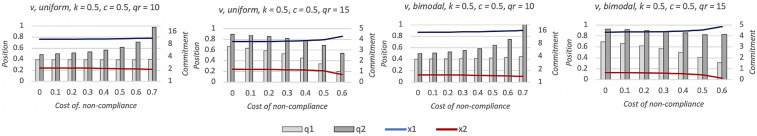

We then relaxed the assumptions that costs of noncompliance, , are zero and that the obligations a country has under an agreement, , are constant over successive renewal periods. implies that parties pay a penalty, in terms of stakeholder support, if they fail to meet their commitments under an agreement in a given renewal period. implies that the national obligations under an agreement change between renewal periods. Fig. 3 reports the effects of variation in on the individual positions and commitment levels taken by parties (assuming medium costs of stakeholder difference and costs of party similarity), while Fig. 4 reports the effects of variation in and on aggregate national commitment, .

Fig. 3.

Party polarization and willingness to commit to an international agreement at the Nash equilibrium as a function of the electoral cost of noncompliance. The Left two panels report results for a uniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space and for two levels of national obligation, . The Right two panels report results for a bimodal distribution and for the same levels of . In all cases, .

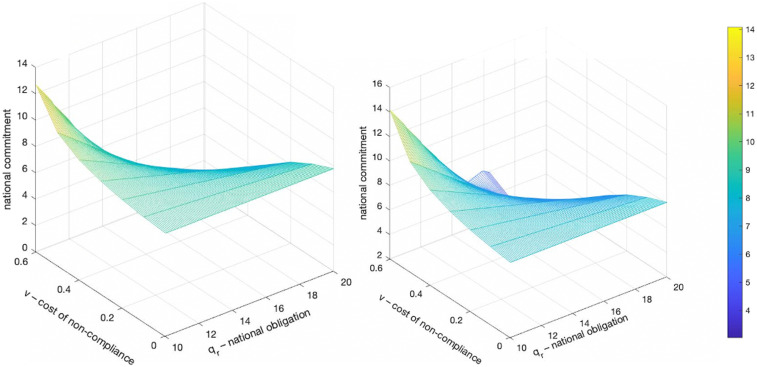

Fig. 4.

National commitment, national obligation, and the electoral cost of noncompliance at the Nash equilibrium. The Left reports results for a uniform distribution of stakeholders in opinion space. The Right reports results for a bimodal distribution. National commitment is measured by .

We found little qualitative difference in party behavior when stakeholders are distributed uniformly as against bimodally in opinion space. With positive costs of party similarity, parties distance themselves from one another for all values of . The effect is larger under a bimodal distribution than under a uniform distribution, but it exists in both cases. We did, however, find that a substantial effect associated with the level of national obligations. Fig. 3, which reports effects of variation in for two levels of , shows that increasing costs of noncompliance induce increasing effort whether stakeholders are uniformly or bimodally distributed in opinion space when national obligations are low but lead to decreasing effort when national obligations are high. At the same time, the gap between the commitment each party is willing to make to an agreement also increases.

To show the net impact of changes in national obligations, Fig. 4 reports the effect of variation in and on aggregate national commitment. Variation in reflects the tendency for obligations under international agreements to change over time. There are many reasons for this. In addition to changes in the environmental conditions addressed by the agreements, or changes in scientific understanding of the implications of those conditions, initial obligations in new agreements are frequently set low to induce countries to sign and then ratify those agreements (39). Fig. 4 reports the effect of progressive increases in national obligations. It shows that while increasing costs of noncompliance result in increasing national commitment, rising obligations have the opposite effect. Moreover, that effect eventually dominates. Moderate increases in national obligations combined with positive costs of noncompliance can induce an increase in national commitment, and the effect is more persistent when stakeholders are uniformly distributed in opinion space than when they are bimodally distributed. But if national obligations continue to increase, the effect will ultimately be to reduce national commitment by both parties.

Discussion

There is evidence that the network of IEAs has at least some of the characteristics of a CAS and that emergent properties may reflect both the topological structure of the system and the dynamics of the institutions at network nodes (2). The last two decades have seen both the unraveling of particular multilateral agreements and the proliferation of bilateral agreements that are (formally) unconnected with other IEAs. At the same time, strongly connected clusters of agreements have emerged to address interdependent issues. One example is the Synergy, an integrated cluster comprising the Stockholm, Rotterdam, and Basel Conventions on hazardous chemicals (5). To understand the dynamics of the network, however, we need first to understand the national responses to changes in the conditions addressed by the treaties at the network nodes. Changes in the treaty system have changed both the benefits delivered by individual treaties and the obligations on signatories to those treaties. An obvious empirical example is the European Union, the costs and benefits of membership to different states having changed dramatically since the Treaty of Rome was signed in 1957. However, the obligations incurred by the signatories to all international agreements turn out to be interdependent and to evolve over time. IEAs are no different. The obligations of one country depend on the obligations of other countries. While initial commitments to many IEAs are frequently close to the noncooperative Nash equilibrium (40), they frequently change thereafter. Even though the progression of obligations may be inherent in the initial terms of the agreement, mission creep can later trigger noncompliance, renegotiation, or withdrawal.

To get at the problem, we focus on national reactions to changes in the terms of agreements. We do this by identifying the Nash equilibrium associated with the conditions obtaining in a given renewal period but then allow those conditions to change. The context in which we study national reactions to changes in the terms of agreements is a growing affective and ideological polarization on many of the issues addressed by IEAs and broader agreements that include an environmental component. Stakeholders and political parties are deeply polarized on some issues but agnostic on others. Reflexive partisanship or identity politics can dictate polarization of party positions on those issues, even if stakeholders have no well-formed views on those issues (41). On familiar issues such as trade policy, stakeholders frequently have well-defined interests and opinions that are well represented by parties (42). On issues where stakeholders are less well informed, however, this can lead parties to take positions that may be inconsistent with the interests of their stakeholders, as in the position taken by parties in Turkey on EU membership (43).

Analysis of party positions on foreign policy issues has generally found less polarization than on domestic issues (44). There is nevertheless evidence for a broad left–right split on foreign policy issues. Parties on the left are more willing to commit to international law, international institutions, and foreign aid, and less willing to intervene militarily, and less committed to free trade (45). In the United States, the distance between parties on foreign policy issues has been shown to depend on domestic politics (46) and is currently increasing (47). Consistent with the argument that polarization of stakeholders (the masses) follows party polarization (the elite) (48–50), a recent Pew Research report on partisan priorities for US foreign policy showed that the positions taken by Democratic and Republican voters on many long-standing foreign policy issues are increasingly polarized, with more than 30-point differences in the priority accorded issues such as climate change, immigration, or the relationship with US allies (51). To capture this trend, we allow parties to face an electoral cost if their positions on particular agreements are too closely aligned, whether or not stakeholders themselves take a position on those agreements.

Our findings imply two propositions about the relation between polarization at the national level and commitment to evolving international agreements, each of which yields testable hypotheses about the simple rules followed by the signatories to IEAs.

Whether or not stakeholders are polarized on the issue addressed by an agreement, when political parties face an electoral cost if they distance themselves from the positions taken by the electorate, the parties will adopt less-polarized positions on the issue than they would if there is no electoral cost but will also be willing to commit less to the agreement.

If national commitment to particular agreements is insufficient to meet national obligations, and if there is an electoral cost to noncompliance, political parties may be willing to commit more to the agreement for a small increase in national obligations but will be willing to commit less to the agreement for a large increase in national obligations. The effect on commitment will be more pronounced, the more polarized stakeholders are on the issue.

The first proposition is not entirely intuitive. It implies that stakeholder engagement may be expected to have a moderating effect on party polarization on specific issues. Our results indicate that, other things being equal, the higher the cost of differences between party and stakeholder, the smaller is the distance between parties and the lower is their commitment at the Nash equilibrium. The impact on commitment is, however, moderated by the impact on polarization. The result holds whether or not the electorate is distributed bimodally in opinion space. While a bimodal distribution of the electorate results in greater party polarization than a uniform distribution, increasing the cost of differences between party and stakeholder reduces that polarization. Interestingly, if stakeholders are themselves polarized on an issue, the evidence is that they are more likely to engage with political parties and the political process on that issue (52). If so, our result indicates that the effect may be to restrict party polarization more than if stakeholders are indifferent. This is consistent with empirical evidence for the convergence of party positions over time (53).

Since our model abstracts from stakeholder heterogeneity beyond their distribution in opinion space, the cost of distance from the electorate is taken to be shared by all stakeholders. In reality, special interest groups are likely to insist on accountability more than general voters, but the implication of the finding is that any increase in the average cost of distance from the electorate will at least contain and may reduce party polarization. On issues where at least some stakeholders care, parties are likely to be less polarized than when none care. This follows from the fact that the cost of differences between party and stakeholder are minimized when parties align with the median voter in each voting bloc. If voters are indifferent, parties may adopt more extreme positions.

A good example is preferential trade agreements that secure market access for exporting and import-dependent firms (54). Over the last two decades, the foreign policy issues attracting most bipartisan support from stakeholders have been the promotion of US economic and business interests abroad (slightly more favored by Republicans) and the protection of the jobs of American workers (slightly more favored by Democrats) (51). US interests in Europe on these questions are served by a wide range of overlapping and interlocking agreements. In the highly polarized US environment that followed the 2016 election, when doubt was cast about the benefits of any relation with Europe, this might have been expected to lead to highly divergent party positions on the issues involved. In practice, however, there was sufficient concern among special interest groups to ensure that party positions were much less polarized and that United States–EU dialogues continued at multiple levels (55).

The second proposition implies that if political parties face electoral costs for failing to comply with the terms of an agreement, a valence issue, their response will depend on the degree to which their stakeholders are polarized on that issue. If stakeholders are highly polarized on the issue, political parties will both take a more polarized position and will adjust their commitment more sharply as costs of noncompliance increase.

Note that noncompliance includes both violation of substantive rules and rejection of the decisions of dispute resolution bodies established by agreements (8). In practice, signatories to IEAs have a wide range of options open to them to limit compliance including nonratification, flexibility mechanisms such as exit clauses, safeguard clauses, and reservations, understandings, and declarations, and exclusion from domestic law. The United States, for example, distinguishes between self-executing treaties that are effective in US law and non–self-executing treaties that require congressional action. Since most agreements entered into are non–self-executing, they are nonenforceable in US law (56). If congressional action is required, however, agreements become politically negotiated and thus are sensitive to stakeholder engagement. In addition, the complexity of the treaty network reduces clarity by introducing overlapping sets of rules and jurisdictions on individual issues (38).

In the European Union, increasing party polarization in member states on the issue of closer integration has resulted in decreasing voter support for EU institutions (57) and a partial reversal of the integration process itself (58). Empirical studies using a measure of party polarization similar to that applied in this paper (the distance between party positions) have found that membership of the European Union has been associated with a nonmonotonic evolution of party polarization—initially decreasing and then increasing. Initial entry for a number of member states was associated with a decline in party polarization, but this was later followed by a rise in party polarization in the United Kingdom, Greece, Poland, Austria, Spain, and Portugal as the net benefits of membership declined (11). The explanation for this lies in the increased costs/decreased net benefits of membership. As the sovereignty costs of membership have increased, so has polarization within member states—in the form of resurgent nationalism, nativist populism, and ideological extremism.

Supranational cooperation between member states in Europe is strongly associated with regional cooperation between governance units within member states (14). That is, low levels of polarization domestically may be associated with willingness to cooperate supranationally. But the example of the American confederation (discussed below) suggests that transborder agreements (the formation of the US federal government) can even occur in the face of high polarization. It is likely that polarization of subgroups limits the extensiveness of such transborder agreements, however.

The process has been characterized as one of “crystallization”—a process whereby high-level order comes about through the cooperation of small solidary groups nested within larger ones (14). The process starts by the formation of cooperation within small groups. Individuals become and remain part of voluntary groups (as distinguished from obligatory ones like the state) only because they derive net benefits from membership. The principal motive for joining such groups is to attain benefits that they are unable to provide for themselves.

Even if these localized groups are quite different from one another, they can cooperate so long as they all seek the same common benefit (such as national security). In large groups made up of smaller ones, the costs of attaining compliance at the highest level are lower than in equal-sized groups only composed of individuals. Crystallization is a bottom-up process whose efficacy derives from its ability to deliver benefits to its members, to provide a framework for cooperative behavior, and to minimize compliance costs at higher levels of organization. High-level order thus rests on the extent of the internally cooperative nature of its constituent group members. Collective solidarity and, over time, shared identities incentivize individuals and groups at all levels to engage in cooperative behavior and familiarize them with the requisite norms, terms, and rules to that end.

In the United States, to take a historical example, the original 13 colonies had very different positions on religion, slavery, and international trade, among many other things. Despite those differences, they shared a common interest in independence from Great Britain. They only came together to ratify the Articles of Confederation by recognizing the independence and sovereignty of the states—that is, by enacting indirect rule (59). Indirect rule permitted the establishment of high-level order in the face of the fissiparous forces that later resulted in the Civil War. Likewise, the increase in direct rule at the expense of states’ rights from the 1960s provided a key structural basis for the currently high level of American political polarization. Our findings on the relation between polarization and levels of commitment to international agreements offer some support for this argument.

Widespread erosion of trust in international governance mechanisms, and the unraveling of many international agreements, may indeed reflect the polarization of political parties at the national level. National polarization may have a negative impact on both the position that parties take on IEAs and their willingness to commit to those agreements. Our findings suggest a motivation for two widely observed trends: the convergence of party positions on particular issues in response to stakeholder engagement with those issues (36, 53), and the effect of compliance gaps on the polarization of parties and their willingness to commit to IEAs (57, 58).

We conclude by drawing attention to the most obvious implications of our two main findings. First, the simple rules governing national responses to changes in the conditions addressed by IEAs are not so simple after all. They are conditioned by the current political environment, and they are sensitive to perceptions of the electoral costs of particular positions. We find that increases in national obligations under IEAs can have negative consequences for national commitment and that those consequences are likely to be most severe in highly polarized environments. One implication of this is that the historic practice of negotiating initial obligations close to the noncooperative Nash equilibrium may be counterproductive, especially in polarized environments. If agreements are to deliver the public good under changing environmental conditions, they should specify the conditions under which obligations may vary, along with a set of mechanisms (acceptable to signatories) for making those adjustments.

Second, we find that stakeholder engagement has the capacity to moderate party polarization on the issues addressed by agreements, even where stakeholders are themselves polarized on those issues. An immediate implication of this is that if the electorate is to moderate party positions on agreements, they need a route to engage on those agreements. In the United States, the most direct route is via congressional elections, but that route is only available if the agreements themselves involve congressional action. Where the terms of international agreements are incorporated in domestic legislation, stakeholders have the capacity to engage in the process.

If the rules governing national responses to changes in the conditions addressed by IEAs are conditioned by the current political environment in member states so are the dynamic consequences both for the agreement itself and for the network to which it belongs. A CAS analysis of IEA network dynamics accordingly needs to factor in the feedbacks that potentially drive the system in one direction or another. Since polarization on the issues addressed by IEAs may be both cause and effect of national responses, the outcome at the level of the system may be either stabilizing or destabilizing—making it all the more important to understand the decision process at the national level.

Methods

The main elements of the extended spatial model, introduced earlier, comprise the electoral costs and benefits of party decisions to support or oppose international agreements, the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, and the strategic options open to each party. Although the context to the study is a secular decline in national support for many instruments of international governance, including many international agreements, we focus on strategic behavior by political parties in one country in one renewal period.

The party net electoral benefit functions associated with a particular agreement are as follows:

in which the parameters have already been described, and are the party’s position on and level of commitment to the agreement. We proceed by backward induction to find the Nash (subgame perfect) equilibrium, considering both uniform and bimodal distributions of voters in opinion space, . Parties first choose their position on the agreement and then choose the level of commitment they are willing to make. To find the optimal position of parties, we find the following derivatives:

and determine the associated reaction functions:

and the Nash equilibrium values:

From these, we obtain total net benefit functions over opinion space, and , and find the first-order necessary conditions with respect to party locations in that space:

The full first-order necessary conditions for are reported in SI Appendix. The intersection of and then yield optimum locations in opinion space, .

Numerical experiments explore the impact of variation in the distribution of stakeholders in opinion space, the distance between political parties, the electoral costs of distance between parties and voters, the similarity of parties, and noncompliance with assessed obligations. By varying the conditional commitment associated with the agreement, , we then consider the effect of the changes in assessed obligations. Details can be found in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

C.P. acknowledges NSF Grant 1414374 as part of the joint National Science Foundation-National Institutes of Health-US Department of Agriculture Ecology and Evolution of Infectious Diseases program.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at https://www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.2102145118/-/DCSupplemental.

Data Availability

All data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.

References

- 1.Mitchell R. B., et al., What we know (and could know) about international environmental agreements. Glob. Environ. Polit. 20, 103–121 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim R. E., Mackey B., International environmental law as a complex adaptive system. Int. Environ. Agreement Polit. Law Econ. 14, 5–24 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim R. E., The emergent network structure of the multilateral environmental agreement system. Glob. Environ. Change 23, 980–991 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biermann F., Pattberg P., Van Asselt H., Zelli F., The fragmentation of global governance architectures: A framework for analysis. Glob. Environ. Polit. 9, 14–40 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan J. C., Fragmentation of international environmental law and the synergy, Vermont. J. Environ. Law 18, 134–172 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim R. E., Is global governance fragmented, polycentric, or complex? The state of the art of the network approach. Int. Stud. Rev. 22, 903–931 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan A., Huitema D., Van Asselt H., Forster J., Governing Climate Change: Polycentricity in Action? (Cambridge University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simmons B. A., Compliance with international agreements. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 1, 75–93 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Downs G., Rocke D. M., Optimal Imperfection? (Princeton University Press, 1995), pp. 27–55. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schimmelfennig F., Leuffen D., Rittberger B., The European Union as a system of differentiated integration: Interdependence, politicization and differentiation. J. Eur. Public Policy 22, 764–782 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konstantinidis N., Matakos K., Mutlu-Eren H., “Take back control”? The effects of supranational integration on party-system polarization. Rev. Int. Organ. 14, 297–333 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sridhar D., King L., US decision to pull out of World Health Organization. BMJ 370, m2943 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Esteban J., Schneider G., Polarization and conflict: Theoretical and empirical issues. J. Peace Res. 45, 131–141 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mueller S., Hechter M., Centralization through decentralization? The crystallization of social order in the European Union. Territ. Politic. Gov. 9, 133–152 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maoz Z., Network polarization, network interdependence, and international conflict, 1816–2002. J. Peace Res. 43, 391–411 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schultz K. A., Perils of polarization for US foreign policy. Wash. Q. 40, 7–28 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bang G., Signed but not ratified: Limits to US participation in international environmental agreements. Rev. Policy Res. 28, 65–81 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Downs A., An Economic Theory of Democracy (Harper, New York, 1957). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peake J. S., The decline of treaties? Obama, Trump, and the Politics of International Agreements. SSRN [Preprint] (2018). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3153840 (Accessed 13 September 2021).

- 20.Kaarbo J., Power and influence in foreign policy decision making: The role of junior coalition partners in German and Israeli foreign policy. Int. Stud. Q. 40, 501–530 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaarbo J., Coalition Politics and Cabinet Decision Making: A Comparative Analysis of Foreign Policy Choices (University of Michigan Press, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hotelling H., Stability in competition. Econ. J. (Lond.) 39, 41–57 (1929). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stokes D. E., Spatial models of party competition. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 57, 368–377 (1963). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Downs A., An economic theory of political action in a democracy. J. Polit. Econ. 65, 135–150 (1957). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hechter M., From class to culture. Am. J. Sociol. 110, 400–445 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Page B. I., Gilens M., Democracy in America?: What Has Gone Wrong and What We Can Do About It (University of Chicago Press, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kelley J. G., Pevehouse J. C., An opportunity cost theory of US treaty behavior. Int. Stud. Q. 59, 531–543 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vlaicu R., Inequality, participation, and polarization. Soc. Choice Welfare 50, 597–624 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grosser J., Palfrey T. R., Candidate entry and political polarization: An antimedian voter theorem. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 58, 127–143 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Faulí-Oller R., Ok E. A., Ortuño-Ortín I., Delegation and polarization of platforms in political competition. Econ. Theory 22, 289–309 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smirnov O., Fowler J. H., Policy-motivated parties in dynamic political competition. J. Theor. Polit. 19, 9–31 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Serra G., Polarization of what? A model of elections with endogenous valence. J. Polit. 72, 426–437 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Anderson S. P., Neven D. J., Cournot competition yields spatial agglomeration. Int. Econ. Rev. 32, 793–808 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hamilton J. H., Thisse J.-F., Weskamp A., Spatial discrimination: Bertrand vs. Cournot in a model of location choice. Reg. Sci. Urban Econ. 19, 87–102 (1989). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Esteban J., Ray D., “Comparing polarization measures” in Oxford Handbook of Economics of Peace and Conflict, M. Garfinkel, S. Skaperdas, Eds. (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2012), pp. 127–151. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams L. K., Whitten G. D., Don’t stand so close to me: Spatial contagion effects and party competition. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 59, 309–325 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Groseclose T., A model of candidate location when one candidate has a valence advantage. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 45, 862–886 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Alter K. J., Meunier S., The politics of international regime complexity. Perspect. Polit. 7, 13–24 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sandler T., Treaties: Strategic considerations. Univ. Ill. Law Rev. 1, 155–180 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murdoch J. C., Sandler T., Sargent K., A tale of two collectives: Sulphur versus nitrogen oxide emission reduction in Europe. Economica 64, 281–301 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leonard N. E., Lipsitz K., Bizyaeva A., Franci A., Lelkes Y., The nonlinear feedback dynamics of asymmetric political polarization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2102149118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Grossman G. M., Helpman E., Identity politics and trade policy. Rev. Econ. Stud. 88, 1101–1126 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hintz L., Identity Politics Inside Out: National Identity Contestation and Foreign Policy in Turkey (Oxford University Press, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hurst S., Wroe A., Partisan polarization and US foreign policy: Is the centre dead or holding? Int. Polit. 53, 666–682 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Raunio T., Wagner W., The party politics of foreign and security policy. Foreign Policy Anal. 16, 515–531 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trubowitz P., Mellow N., Foreign policy, bipartisanship and the paradox of post-September 11 America. Int. Polit. 48, 164–187 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Jeong G.-H., Quirk P. J., Division at the water’s edge: The polarization of foreign policy. Am. Polit. Res. 47, 58–87 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hetherington M. J., Resurgent mass partisanship: The role of elite polarization. Am. Polit. Sci. Rev. 95, 619–631 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lupu N., Party polarization and mass partisanship: A comparative perspective. Polit. Behav. 37, 331–356 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silva B. C., Populist radical right parties and mass polarization in the Netherlands. Eur. Polit. Sci. Rev. 10, 219–244 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pew Research Center , Conflicting Partisan Priorities for U.S. Foreign Policy (Pew Research Center, Washington, DC, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abramowitz A. I., Saunders K. L., Is polarization a myth? J. Polit. 70, 542–555 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Adams J., Somer-Topcu Z., Policy adjustment by parties in response to rival parties’ policy shifts: Spatial theory and the dynamics of party competition in twenty-five post-war democracies. Br. J. Polit. Sci. 39, 825–846 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 54.Eckhardt J., Elsig M., Support for international trade law: The US and the EU compared. Int. J. Const. Law 13, 966–986 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Blanc E., ‘We need to talk’: Trump’s electoral rhetoric and the role of transatlantic dialogues. Politics 41, 0263395720936040 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pollack M. A., Who supports international law, and why?: The United States, the European Union, and the international legal order. Int. J. Const. Law 13, 873–900 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bearce D. H., Scott B. J. J., Popular non-support for international organizations: How extensive and what does this represent? Rev. Int. Organ. 14, 187–216 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hobolt S. B., De Vries C. E., Public support for European integration. Annu. Rev. Polit. Sci. 19, 413–432 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hechter M., Containing Nationalism (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2000). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and/or SI Appendix.