Abstract

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

As the number of coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) cases increased in the United States, multiple health organizations, including the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, endorsed cancellation of nonemergent surgeries to conserve health care resources and minimize exposure to COVID-19.1 To better understand the impact of COVID-19 on plastic and reconstructive surgery, we evaluated the trends of surgical cases at our institution before the pandemic, at the peak, when the majority of surgeries were on hold, and during the recovery phase, which involved resumption of surgical cases.

California enacted a statewide shelter-in-place mandate in mid-March of 2020, and Stanford Health Care began holding all elective surgeries during this time. By the end of April of 2020, Stanford Health Care consistently had fewer than 20 hospitalized COVID-19–positive patients and fewer than 10 patients requiring intensive care unit care, with a total positive COVID-19 test result rate of 1.7 percent. Given the institution’s stability of inpatient COVID-19 patients, phased scheduling of surgeries occurred over a 2-week period, with all surgeries allowed by May 4, 2020.

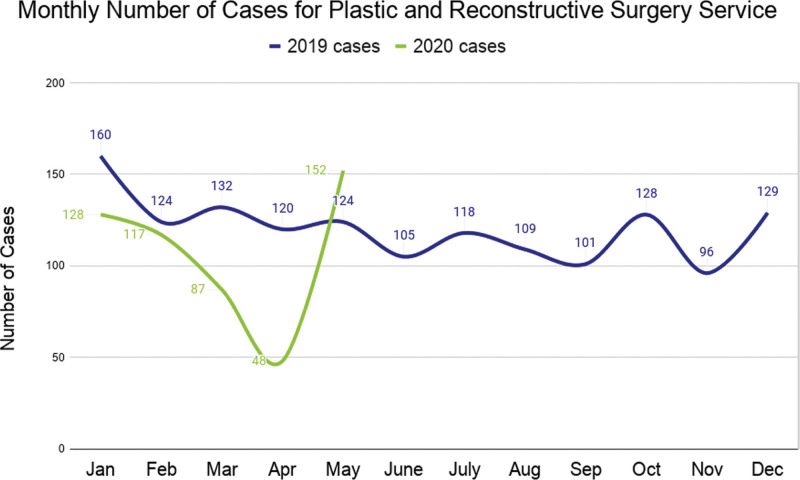

Plastic and reconstructive surgery case volume as a whole and by specialization was compared between 2019 and 2020 for adult patients at Stanford Health Care. While the number of emergent/urgent plastic and reconstructive surgery cases remained relatively stable, the number of elective cases declined sharply, especially in April of 2020, when there were 60 percent fewer cases than in 2019 involving all plastic and reconstructive surgery specialty categories (Fig. 1). The most notable changes occurred in cosmetic surgery and general plastics, at −100.0 percent and −88.2 percent, respectively (Table 1). The largest change in case numbers for May of 2020 during the recovery phase relative to May of 2019 was observed in cosmetic (+125.00 percent), hand (+93.3 percent), and craniofacial surgery (+39.1 percent). From the historical comparison of our patients in 2020 and 2019, the largest groups of patients who still need surgery are breast patients. The significant increase in volume of aesthetic patients in May of 2020 compared to 2019 indicates that this patient group is seeking surgical care. This insight into surgical trends for different patient groups can help prioritize and identify patients for treatment. (See Figure, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows case volume trends in six specialty categories within plastic and reconstructive surgery from January of 2019 through May of 2020. All categories exhibited the most significant decrease in case volumes during April of 2020 compared to April of 2019, http://links.lww.com/PRS/E805.)

Fig. 1.

Trends in Stanford Health Care’s plastic and reconstructive surgery case volume. The total number of cases from January of 2019 to December of 2019 was compared to those from January of 2020 to May of 2020. A substantial decrease in the number of cases during the COVID-19 pandemic is shown.

Table 1.

Percentage Change between 2019 and 2020 for March,* April, and May† for the Stanford Health Care Plastic Surgery Service and Subspecialty Categories

| Percentage Change for March | Percentage Change for April | Percentage Change for May | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plastic surgery | −34.1% | −60.0% | +22.6% |

| Hand | 0% | −52.9% | +93.3% |

| Cosmetic | −40% | −100% | +125% |

| Breast | −28.2% | −68.4% | 0% |

| General plastics | −73.7% | −88.2% | −7.14% |

| Craniofacial | +15.7% | −25.9% | +39.1% |

When elective cases were placed on hold.

When all surgical cases were allowed.

As hospitals reintroduce surgeries, the greatest challenge is safety. Guidance can be provided by the “medically necessary, time-sensitive” procedure system developed in the setting of COVID-19.2 At Stanford Health Care, preoperative testing is performed on the majority of surgical patients 72 hours or more before surgery, with patients self-quarantining after testing until surgery. Other measures include understanding what resources are readily available from a supply chain standpoint, environmental control, daily symptom self-assessments, staff protection, and incorporation of medical practices to decrease exposure. (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows hospital-wide considerations for safely resuming surgical care, including prefacility precautions, available COVID-19 testing inventory, resource requirement, location of cases, environmental control, staff protection, and anesthesia considerations, http://links.lww.com/PRS/E806.4,5) In addition, systems for contact tracing for anyone with COVID-19 are necessary.

Maintaining a state of recovery will require optimization of health care practices, as well as the ability to respond to a constantly changing COVID-19 climate with concerns for resurgences into 2025.3 The ideal situation for a return to normalcy involves ample, efficient, and accurate testing along with scientifically proven treatment or vaccine availability. We hope that our COVID-19 experience provides a framework of considerations for resuming activities in an academic plastic surgery practice during these unprecedented times.

DISCLOSURE

The authors have no financial disclosures or conflicts of interest to declare. No funding was received for this article.

Supplementary Material

GUIDELINES

Viewpoints, pertaining to issues of general interest, are welcome, even if they are not related to items previously published. Viewpoints may present unique techniques, brief technology updates, technical notes, and so on. Viewpoints will be published on a space-available basis because they are typically less timesensitive than Letters and other types of articles. Please note the following criteria:

Text—maximum of 500 words (not including references)

References—maximum of five

Authors—no more than five

Figures/Tables—no more than two figures and/or one table

Authors will be listed in the order in which they appear in the submission. Viewpoints should be submitted electronically via PRS’ enkwell, at www.editorialmanager.com/prs/. We strongly encourage authors to submit figures in color.

We reserve the right to edit Viewpoints to meet requirements of space and format. Any financial interests relevant to the content must be disclosed. Submission of a Viewpoint constitutes permission for the American Society of Plastic Surgeons and its licensees and assignees to publish it in the Journal and in any other form or medium.

The views, opinions, and conclusions expressed in the Viewpoints represent the personal opinions of the individual writers and not those of the publisher, the Editorial Board, or the sponsors of the Journal. Any stated views, opinions, and conclusions do not reflect the policy of any of the sponsoring organizations or of the institutions with which the writer is affiliated, and the publisher, the Editorial Board, and the sponsoring organizations assume no responsibility for the content of such correspondence.

Footnotes

Related digital media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSJournal.com.

The first two authors contributed equally to this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.American Society of Plastic Surgeons, The Plastic Surgery Foundation. ASPS statement on breast reconstruction in the face of COVID-19 pandemic. March 24, 2020. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/medical-professionals/COVID19-Breast-Reconstruction-Statement.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2020.

- 2.Prachand VN, Milner R, Angelos P, et al. Medically necessary, time-sensitive procedures: Scoring system to ethically and efficiently manage resource scarcity and provider risk during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;231:281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kissler SM, Tedijanto C, Goldstein E, Grad YH, Lipsitch M. Projecting the transmission dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 through the postpandemic period. Science. 2020;368:860–868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo M, Cao S, Wei L, et al. Precautions for intubating patients with COVID-19. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1616–1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kangas-Dick AW, Swearingen B, Wan E, Chawla K, Wiesel O. Safe extubation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Respir Med. 2020;170:106038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.