Abstract

Negatively charged dextran sulfate (DS)-chitosan nanoparticles (DSCS NPs) contain a DS outer shell with binding properties similar to those of heparin and are useful for the incorporation and delivery of therapeutic heparin-binding proteins. These particles, however, are unstable in physiological salt solutions due to their formation through electrostatic interactions. In the present study, a method was developed to covalently crosslink chitosan in the core of the DSCS NP with a short chain dicarboxylic acid (succinate), while leaving the outer shell of the particle untouched. The crosslinked particles, XDSCS NPs, are stable in NaCl solutions up to 3 M. XDSCS NPs were able to incorporate heparin-binding proteins (VEGF and SDF-1α) rapidly and efficiently, and maintain the full biological activity of the proteins. The incorporated proteins were not released from the particles after a 14-day incubation period at 37°C in PBS, but retained the same activity as those stored at 4°C. When aerosolized for delivery to the lungs of rats, XDSCS NP-incorporated SDF-1α showed a ~17-fold greater retention time compared to that of free protein. These properties suggest that XDSCS NPs could be beneficial for the delivery of therapeutic heparin-binding proteins to achieve sustained in vivo effects.

Keywords: Polysaccharide nanoparticles, drug delivery, heparin-binding proteins

1. Introduction

Therapeutic proteins often exert a highly specific, yet complex set of functions. Their effectiveness and potency in disease treatment have become increasingly recognized in clinical settings. (Dimitrov, 2012; Leader et al., 2008) These proteins, however, are also limited in supply and high in cost. Improving their in vivo stability and lifetime would sustain the therapeutic effects of these valuable proteins. (Moncalvo et al., 2020)

Many therapeutic proteins are heparin-binding proteins, including growth factors, morphogens, and chemokines that are involved in immune regulation, tissue/organ development, repair, and regeneration. These proteins contain a heparin-binding site(s) or domain(s) in their structures, and can bind to heparin or heparan sulfate present at the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix. Binding to heparan sulfate serves as a “docking” mechanism, which stabilizes the soluble proteins and facilitates their interactions with receptors on the cell membrane.(Gallagher, 2015; Xu and Esko, 2014)

Dextran sulfate (DS) chitosan (CS) nanoparticles (DSCS NPs) are prepared by the interaction of the oppositely charged polysaccharides. Under certain conditions,(Schatz et al., 2004) such as stirring a mixture of high-molecular-weight DS and low-molecular-weight CS with excess amounts of DS to CS, the formed particles contain a negatively charged outer shell comprising un-neutralized DS segments (Figure 1). Since DS is an analog of heparin, (Ricketts, 1952) heparin-binding proteins can bind to the outer shell of DSCS NPs with high affinity. Prior studies have shown that the DSCS NPs are able to incorporate therapeutic heparin-binding proteins, maintain their biological activity, and enhance their thermostability.(Zaman et al., 2016) Thus, anionic DSCS NP could be a useful nanocarrier for therapeutic heparin-binding protein delivery.

Figure 1. Diagram of nanoparticle (NP) preparation.

Complexing dextran sulfate (DS) and chitosan (CS) in the presence of ZnSO4 led to the formation of DSCS NP, which contains an inner core consisting of neutralized DS and CS segments and Zn2+ and an outer shell comprising of un-neutralized DS segments. The chitosan in the core of DSCS NP was covalently crosslinked with succinate, resulting in XDSCS NP. Heparin-binding proteins were incorporated in the outer shell of XDSCS NP, forming protein-NP.

DSCS NPs are, however, unstable in salt solutions. A previous study has shown that the critical coagulation concentration of anionic DSCS NPs in NaCl is 0.09 M (Schatz et al., 2004), a concentration lower than that of physiological saline (0.15 M). In DSCS NPs, the charge-neutralized segments of DS and CS are secluded in the core of the particle (Figure 1). Competition from the salt ions would dismantle the conformation of the core, leading to the collapse of the particle. Reinforcing the core structure of the particle by introducing covalent bonding could solve the problem of salt-instability. The present study developed a method to crosslink chitosan in the core of DSCS NP with a short chain dicarboxylic acid, succinate. The crosslinked NPs, XDSCS NPs, were then tested for their salt resistance as well as the efficiencies of incorporation, retention, and in vivo delivery of heparin-binding proteins. Of the proteins tested, VEGF and SDF-1α, have functions in angiogenesis and endothelium repair (Krilleke et al., 2009), and stem cell homing (Ghadge et al., 2011), respectively, which have therapeutic implications in tissue damage-related diseases.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Dextran sulfate sodium salt, weight-average molecular weight (MW) 500 kDa (#BP1585–100), 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (EDC, #22981), Gibco™ HEPES 1M (pH 7.2–7.5, #15630–080), and Invitrogen™ UltraPure™ DNase/RNase-Free Distilled water were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Chitosan (MW range 50–190 kDa, 75%–85% deacetylated) (#448869), zinc sulfate (#204986), mannitol (#M9546), succinic acid (#S3674), N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS, #130672), Dulbecco’s phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and 10x DPBS (# D8537 and #59331C), and lysozyme from chicken egg white (#L2879) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Recombinant human stromal cell-derived factor-1α, SDF-1α (SDF), and human vascular endothelial growth factor165, VEGF165 (VEGF), were prepared in the authors’ laboratory as previously described.(Lauten et al., 2010; Yin et al., 2013) Human CXCL12/SDF-1 DuoSet ELISA kit (#DY350) was purchased from R&D Systems.

2.2. Preparation of XDSCS NP

Particle preparation was carried out under sterile conditions; reagents were sterile filtered, endotoxin level was less than 0.06 EU/mg, and UltraPure water was used. Prior to XDSCS NP preparation, DSCS NP was produced according to a previously described procedure.(Zaman et al., 2016) Lyophilized DSCS NP was suspended in water and HEPES buffer was added to the suspension to a final concentration of 100 mM. Succinate (pH 5.2) was added to the buffered DSCS NP to a final concentration of 25 mM and mixed with the particles for 1 h at room temperature. The mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant completely removed. The particle pellet was resuspended in water to which 100 mM HEPES buffer was added. EDC (45 mM) and NHS (45 mM) were added and mixed with the particles for 20 h. The particles in the reaction mixture were precipitated by centrifugation and washed with PBS. The particles were then mixed with 3x PBS for 2–3 h and centrifuged at 200 × g for 15 min. Particles in the centrifugation supernatant, XDSCS NPs, were separated from the aggregated particles (in the pellet) and washed with PBS. The XDSCS NPs were further selected and sterilized by filtration through 0.45 μm and 0.22 μm pore size PVDF membranes consecutively. The final XDSCS NPs were concentrated by centrifugation and suspended in 5% mannitol for frozen storage. The particle diameter, polydispersity index, and zeta potential were measured by dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer instrument (Malvern Instruments) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.3. Azure A assay

The amount of un-neutralized DS in XDSCS NP was measured with an Azure A assay as described previously.(Zaman et al., 2016) Briefly, DS standards (0, 0.4, 0.8, 0.12, 0.16, and 0.2 mg/mL) and XDSCS NP samples were diluted in water and added to wells in a 96-well plate (10 μL/well). Azure A working solution (0.02 mg/mL in water) was added to each well (200 μL/well). After brief mixing, the plate was read at 620 nm and absorbance recorded. Samples were run in triplicate, and empty wells were used as the instrument blank.

2.4. Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy analysis

FTIR measurements were performed using a Vertex 70 spectrometer (Bruker) with an attenuated total reflectance (ATR) accessory. Dry powder forms of DS, CS, DSCS NP, or XDSCS NP were transferred onto the surface of a Ge ATR crystal and IR spectra measured in three technical replicates. Spectra were recorded in the region between 4000 and 600 cm−1 with a spectral resolution of 4 cm−1. Each spectrum was recorded as the ratio of the sample spectrum to the background spectrum of the clean ATR plate.

2.5. Salt stability test

DSCS NPs and XDSCS NPs were precipitated by centrifugation and resuspended in water or PBS, respectively. The suspension (20 μL) was mixed with 300 μL NaCl solution at concentrations of 0 to 5 M and rotated for 20 h at room temperature. Water (1.5 mL) was added to each tube, and particles were rotated for 30 min before being precipitated by centrifugation. The pellets were resuspended in 100 μL water or PBS for DSCS NPs or XDSCS NPs, respectively, for particle size measurement.

2.6. Protein incorporation into XDSCS NP

Specific amounts of protein and XDSCS NPs were each diluted in PBS. Protein solutions were added to the particles slowly (~100 μL/min) while stirring at 800 rpm. After 20 min or at a pre-specified time, the mixture was centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min. The un-incorporated protein (in the supernatant) was separated from the particles (in the pellet), and the latter was resuspended in PBS to the original volume. The protein content in the centrifuged fractions were analyzed on a 4–20% SDS gel (BioRad), which were electrophoresed at 200 V for ~20 min, followed by Coomassie blue staining with the GelCode Blue staining reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and densitometry analysis with a ChemiDoc imaging system (BioRad).

2.7. Cell migration assay

The chemoattractant activity of SDF was measured by a cell migration assay using Jurkat cells, an immortalized T cell line. SDF or SDFNP were diluted in 0.6 mL migration medium (RPMI-1640 medium containing 0.5% BSA) and added to wells in a 24-well plate (bottom wells). After 30 min incubation at 37°C, transwell inserts (polycarbonate, pore size 5 μm, diameter 6.5 mm, Corning) were placed into the wells and loaded with 5×105 Jurkat cells in 100 μL migration medium. The plate was incubated at 37°C for 2 h followed by removal of the transwells. Migrated cells in the bottom wells were mixed with fluorescent counting beads (50 μl/well, Invitrogen™ 123count eBeads) and counted by flow cytometry (DXP11, BD Biosciences) at high speed for 60 sec. For negative controls, the cells were added to the transwells with migration medium in the bottom wells. For the input cell number, cells were added directly to the bottom well and counted. The ratio of the cell-to-bead number was used for calculation, and migrated cells were presented as the percentage of the input after subtraction of that in negative controls.

2.8. Endothelial cell proliferation assay

The activity of VEGF was measured by an endothelial cell proliferation assay using human pulmonary artery endothelial cells (Lonza). Cells were seeded on a 96-well plate at 5000/well in 0.1 mL complete medium (EGM-2 MV, Lonza) and subsequently starved for 24h in minimum medium (EBM-2 plus 0.4% FBS). Cell medium was replaced with minimum medium containing various concentrations of VEGF, and incubated with the cells for 3 days. An MTS solution from the One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega G3580) was added to the cells (20 μL/well) and incubated for 2–4h. The developed color was read at 490 nm. VEGF activity was presented as the difference in 490 nm absorption between the cells cultured in VEGF and those cultured in minimum medium.

2.9. In vivo retention time analysis

Animal studies were carried out in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and all procedures were approved by the Brigham and Women’s Hospital IACUC. Male nude rats were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. SDF or SDFNP (containing 12 μg SDF) was diluted in 0.25 mL PBS and aerosolized to the lungs of rats with a MicroSprayer Aerosolizer from Penn-Century. At various timepoints after aerosolization, rat lungs were harvested after perfusion with PBS and frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen. Cryo powder of the lung tissues was generated with a Spex 1600 miniG homogenizer by grounding the tissue in a 15 mL polycarbonate jar with 3 metal beads for 2 min at 1500 rpm. Aliquots of the cryo tissue powder (~ 100 mg) were sonicated (24 sec) in 0.6 mL PBS containing 1 mM EDTA and 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail Set III (Calbiochem). The sonication homogenate was added to 0.1 mL 0.5 M Na3PO4 (final pH 12), incubated for 10 min, and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The centrifugation supernatant was collected (0.5 mL), added to 0.1 mL 0.5 M NaH2PO4 (final pH 7.5), and centrifuged again at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected, and protein concentration determined by the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay. SDF concentration in the tissue homogenate supernatant was measured with a Human CXCL12/SDF-1 DuoSet ELISA kit following the manufacturer’s instructions.

3. Results

3.1. Preparation of XDSCS NPs

The detailed procedure for the preparation of crosslinked DSCS NPs (XDSCS NPs) is described under Materials and Methods. The reaction scheme is shown in Figure 2. Traditionally, the crosslinking reaction is carried out by mixing the reactants (DSCS NP and succinate) and catalysts (EDC and NHS) together and allowing the reaction to proceed for a certain time period. This approach, however, continuously failed for the DSCS NP crosslinking despite various changes to the reaction conditions such as the concentrations and ratios of input reagents, reaction time, and temperature. The resulting particles inevitably aggregated after incubation in high-salt solutions during the selection step. In this reaction, chitosan was only partially dissociated from DS in the reaction buffer (at pH > pKa of chitosan amines); thus, the reactive amine groups in chitosan were unquantifiable in the particle format. An excess amount of succinate would favor the incomplete reaction product, while an insufficient amount cannot yield adequate crosslinking. To solve this dilemma, the crosslinking reaction was divided into two steps. Firstly, a saturated concentration of succinate was mixed with DSCS NP for 1 h, and unbound succinate was completely removed from the reaction mixture by centrifugation. Secondly, EDC/NHS were added to the particle suspension to catalyze amide bond formation between succinate carboxyl and chitosan amine groups. Approximately 80% of DSCS NPs in the reaction were crosslinked, which were selected by incubation in 3x PBS (0.45 M salt concentration). The salt-resistant XDSCS NPs were further selected and sterilized by filtration through a 0.22 μm pore size PVDF membrane. Other short chain dicarboxylic acids, such as malate, tartrate, and glutamate, worked equally well following the same procedure (data not shown).

Figure 2. Crosslinking chitosan in DSCS NP.

Dissociated chitosan segments in the core of DSCS NP react with succinic acid (SA) under EDC and NHS catalysis. Two products could be formed: SA-crosslinked chitosan in which both carboxyl groups in SA form amide bonds with chitosan amines; and SA-bound chitosan in which only one carboxyl group in SA is reacted and chitosan not crosslinked.

3.2. Chemical and physical properties of XDSCS NPs

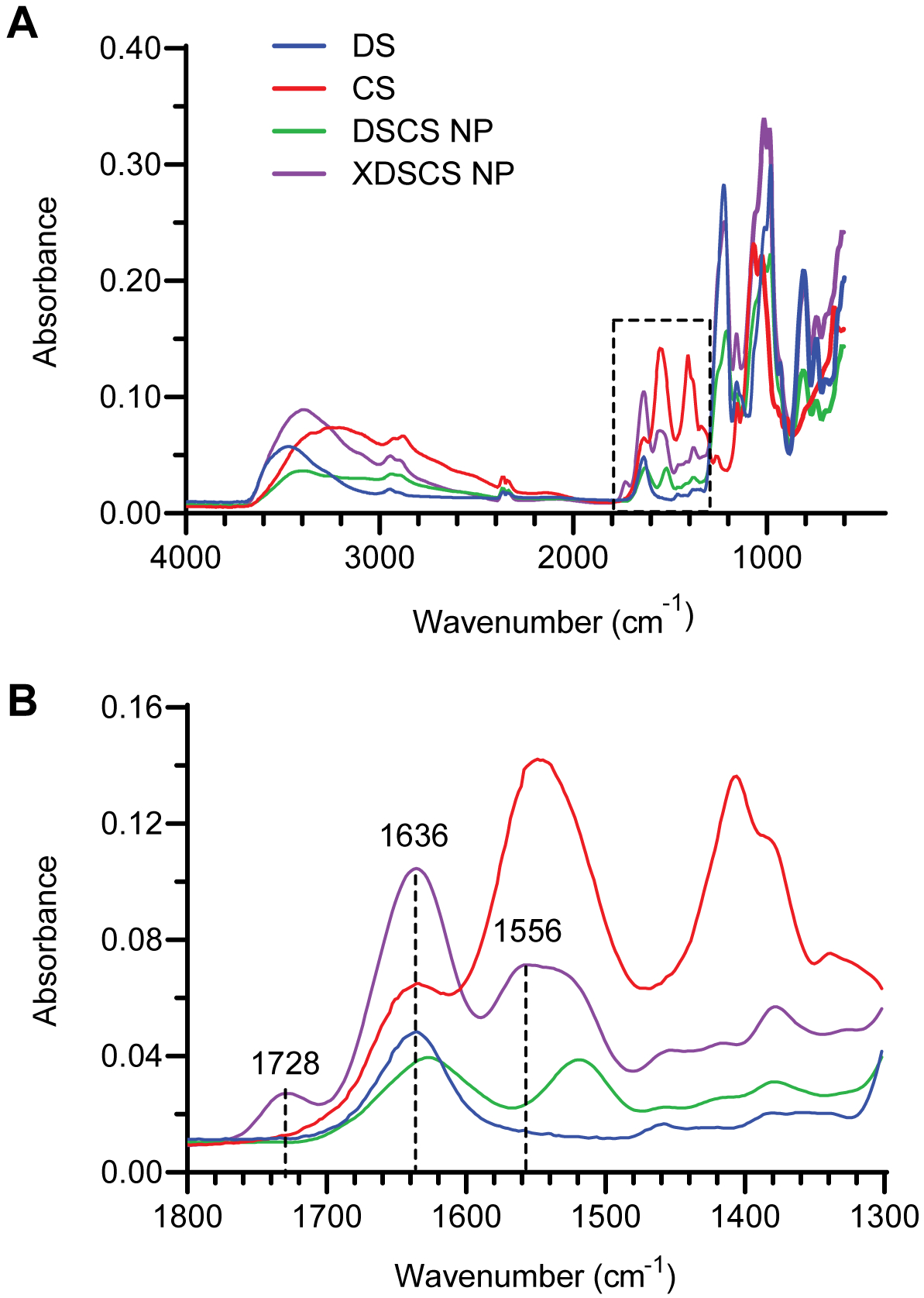

Figure 3 shows the Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra of DS, CS, DSCS NP, and XDSCS NP. Compared to DSCS NP, distinct amide I (1636 cm−1) and amide II (1556 cm−1) bands were found in XDSCS NP, indicating the amide bond formation between succinate carboxyl and chitosan amines. A small band at 1728 cm−1, the region of carboxyl C=O stretching vibration, was also present in the XDSCS NP sample, indicating that a small fraction of succinate in the particle was incompletely reacted.

Figure 3. FTIR spectra.

Dextran sulfate (DS), chitosan (CS), DSCS NPs, and XDSCS NPs were analyzed using a Bruker Vertex 70 spectrometer with an ATR accessory. (A) Spectra recorded in the region of 4000–600 cm−1; and (B) Expanded view in the region of 1800 −1300 cm-1. Absorption bands in the 1728, 1636, and 1556 cm−1 ranges are assigned to carboxyl C=O stretching, amide C=O stretching (amide I), and amide C-N and N-H bending (amide II) vibration, respectively.

The salt stability of XDSCS NPs was compared with that of DSCS NPs by incubation of the particles in 0 to 5 M NaCl solutions for 20 h at room temperature. As shown in Figure 4, without crosslinking, DSCS NPs aggregated heavily in 0.15 M NaCl solutions, with dramatic increase in particle size and polydispersity index. XDSCS NPs, by contrast, did not show significant change in particle size or polydispersity index when incubated in NaCl solutions up to 3M in concentration, indicating a remarkable stability of the particle in salt solution.

Figure 4. Stability of XDSCS NPs in NaCl solutions.

DSCS NPs or XDSCS NPs were suspended in NaCl solutions at the indicated concentrations and incubated at room temperature for 20 h. The particles were then precipitated by centrifugation followed by resuspension in water or PBS, respectively, for size measurements. Data are mean ± SD from three separate experiments, *p<0.05 compared to the corresponding NPs incubated in 0 M NaCl.

Measured by dynamic light scattering, XDSCS NP had a diameter of 349 ± 5 nm and zeta potential −48 ± 2 mV (Table 1). These parameters were comparable to those of DSCS NP, suggesting that the DS outer shell of the particle was not affected by the crosslinking reaction. XDSCS NPs had been filtered through a 220 nm pore size PVDF membrane. The hydrodynamic size of the particle may reflect the flexibility of the DS outer shell of the particle, which was packed tightly to the core when passing through the small pores of the membrane.

Table 1.

Size and charge properties of prepared particles

| Nanoparticle | Diameter (nm) | Polydispersity Index | Zeta Potential (-mv) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DSCS NP | 370 ± 5 | 0.105 ± 0.011 | −46.0 ± 8.6 |

| XDSCS NP | 349 ± 5 | 0.051 ± 0.008 | −47.9 ± 2.4 |

| Lysozyme NP | 345 ± 17 | 0.111 ± 0.018 | −42.9 ± 4.1 |

| SDF NP | 315 ± 6 | 0.059 ± 0.016 | −43.4 ± 2 .5 |

| VEGF NP | 307 ± 3 | 0.042 ± 0.024 | −42.7 ± 1.3 |

3.3. Incorporation of heparin-binding proteins into XDSCS NPs

The incorporation of heparin-binding proteins was performed by adding the protein slowly (over 1 min) to the particles suspended in PBS, while stirring at a high speed to facilitate homogeneous distribution of the protein among the particles. To determine the rate of the incorporation, a time course study was carried out with three different heparin-binding proteins, lysozyme,(Guyot et al., 2016; Wang and Kloer, 1984; Zou et al., 1992) SDF,(Amara et al., 1999) and VEGF.(Krilleke et al., 2009) As shown in Figure 5, > 92% of total protein incorporation was achieved after 1 min (the time for protein addition to the particles); the maximum incorporation was reached after 10–20 min. The incorporation efficiencies of the three proteins varied between 92–97%, likely related to the endogenous structural properties of the proteins.

Figure 5. Time course of protein incorporation into XDSCS NPs.

Lysozyme (A), SDF (B), and VEGF (C) were mixed with XDSCS NPs in PBS for 1, 5, 10, or 20 min, followed by centrifugation. The resulting supernatants (S) and pellet suspensions (P) were examined by SDS gel electrophoresis (gel images shown on left) and densitometry quantification of the protein bands (shown on right). Data are mean ± SD from three separate experiments.

The incorporation capacity of XDSCS NPs was examined by an incorporation dose-response study (Figure 6). Increasing amounts of lysozyme were mixed with a fixed amount of XDSCS NPs that was quantified by an Azure A assay, measuring un-neutralized DS in the outer shell of the particle. The loading ratio of lysozyme to DS was examined at 0.4, 0.8, 1.1, 1.5, 1.9, and 2.3 mg/mg (lysozyme:DS), which corresponded to 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 nmol lysozyme per 100 nmol of repeating glucose sulfate units in DS (for calculation of the unit conversion, see ref.(Zaman et al., 2016)). As shown in Figure 6A, 88–97% of input lysozyme was incorporated into the particles at all the ratios tested; however, at a ratio of 1.9 mg/mg, the particle size of XDSCS NPs was markedly increased, indicating significant aggregation (Figure 6B). At a ratio of 1.1 mg/mg, the particle size was unchanged, and the polydispersity index was increased but less than 0.1, suggesting this is the maximum ratio that can be used for lysozyme incorporation (Figure 6C). For different heparin-binding proteins, this ratio would differ owing to different molecular weights, different structural features, and different binding mechanisms of the proteins, which need to be empirically assessed.

Figure 6. Dose-response of lysozyme incorporation.

Increasing amounts of lysozyme were mixed with XDSCS NP containing a fixed amount of un-neutralized DS. After 20 min, the mixtures were centrifuged, and the resulting supernatants (S) and pellet suspensions (P) were examined by SDS gel electrophoresis (Panel A). The particles in the pellet suspension were also subjected to size analysis (Panels B and C). Data are mean ± SD from three separate experiments, *p<0.05 compared to XDSCS NP with no lysozyme.

3.4. Activity and stability of XDSCS NP-incorporated protein

SDF-incorporated XDSCS NP (SDF-NP) and VEGF-incorporated XDSCS NP (VEGF-NP) were used for the activity and stability studies. SDF is a chemokine whose chemoattractant activity is measured in a cell migration assay. VEGF is a growth factor whose growth activity is measured by an endothelial cell proliferation colorimetric assay. As shown in Figure 7, when compared at multiple doses of the proteins, there were no significant differences in the activities between free and NP-incorporated SDF (Figure 7A) or VEGF (Figure 7B).

Figure 7. Activities of SDF and VEGF before and after incorporation into XDSCS NPs.

(A) Comparison of cell migration activities of SDF in free (SDF) and NP-incorporated (SDF-NP) forms at three SDF doses. (B) Comparison of activities of VEGF in free (VEGF) and NP-incorporated (VEGF-NP) forms at five different doses, measured by a pulmonary artery endothelial cell proliferation colorimetric assay. Data are mean ± SD from three experiments. No statistical difference was found between all pairs tested.

The stabilities of SDF-NP and VEGF-NP were studied by incubating the particles in PBS at 37°C for 14 days. The release of the proteins from the particles was examined by SDS gel electrophoretic analyses, and the activities of the SDF-NP and VEGF-NP were measured at the end of the 14-day incubation. As shown in Figure 8A and 8B, there was no significant release of the proteins from either SDF-NP or VEGF-NP after 0, 3, 7, 10, or 14 days of incubation. The activities of incorporated SDF and VEGF after the 14-day incubation at 37°C were comparable to those in the aliquots stored at 4°C during that time (Figures 8C and 8D), indicating a remarkable thermostability of the NP-incorporated proteins.

Figure 8. Stability of SDF-NP and VEGF-NP after a 14-day incubation at 37°C.

SDF-NP (A) and VEGF-NP (B) were suspended in PBS, divided into aliquots, and incubated at 37°C. After 0, 3, 7, 10, or 14 days, aliquots were removed from the incubation and released proteins were separated from the particles by centrifugation. The centrifuged supernatants (S) and pellet suspensions (P) were analyzed by SDS gels electrophoresis followed by densitometry analysis. The activity of SDF-NPs (C) or VEGF-NPs (D) at the end of the 14-day 37°C incubation was compared with that of aliquots stored at 4°C over the same time period. Data are mean ± SD from three experiments. No statistical difference in protein release or activities was found.

3.5. Release XDSCS NP-bound proteins by alkaline pH

For research purposes, it is sometimes necessary to release the incorporated proteins from XDSCS NP in their native form. The released proteins could be used for ELISA quantification or re-purification of the protein. Methods involving extended sonication and/or detergent treatments of the particles were tested but had no effect on protein release (data not shown). Since heparin binding is mediated by charge interactions involving basic residues (arginine, lysine, and histidine) in the protein, an alkaline pH release method was tested. Lysozyme-NP, SDF-NP, and VEGF-NP were suspended in phosphate- or Tris-buffered saline at pH of 8, 9, 10, 11, or 12 for 10 min, the released proteins were separated from the particles by centrifugation and analyzed on SDS gels. As shown in Figure 9, small amounts of proteins were released from the particles at pH 8, 9, or 10. Substantial release of lysozyme, SDF, and VEGF from the particles occurred at pH 11, which was ~ 61%, 75%, and 36% of the total incorporated protein, respectively. At pH 12, ~ 88%, 91%, and 86% of lysozyme, SDF, and VEGF were released, respectively. The pKa of the side chain guanidino and amino group in arginine and lysine is 12.5 and 10.5, respectively, in their free amino acid forms. The release of the proteins from XDSCS NP, therefore, was likely caused by the deprotonation of the side chain amines, which should be reversed once the solution pH is adjusted to neutral. High salt concentration could also release the protein; however, > 1 M NaCl was required and was impractical for the subsequent analysis, e.g., ELISA quantification of the release proteins.

Figure 9. Protein release from XDSCS NPs by alkaline pH.

Lysozyme NP (A), SDF-NP (B), or VEGF-NP (C) were mixed with Tris- (pH 8 and 9) or phosphate- (pH 10, 11, and 12) buffered saline for 10 min. The mixtures were centrifuged and resulting supernatants (S) and pellet suspensions (P) were analyzed by SDS gel electrophoresis. Representative gel images are shown on the left of the panels, and densitometry analyses of the protein bands are shown on the right. Data are mean ± SD from three experiments.

3.6. Retention time of SDF-NP in rat lungs

To examine the in vivo retention time, 12 μg SDF in free or NP form (SDF-NP) were aerosolized into the lungs of rats. Lung tissues were harvested at different timepoints, and SDF content in tissue homogenate supernatants was measured by ELISA. As shown in Figure 10, the concentration of SDF or SDF-NP in the lung over time exhibited an exponential decay pattern. The decay constant k was 0.3849 and 0.0220 for SDF and SDF-NP, respectively. Using the exponential decay equation, ln{[SDF]t/[SDF]0} = −kt, the time (t) was calculated. The retention times for free SDF were 2, 6, and 12 h for 50%, 10%, and 1% retention in the lung, respectively; and those for SDF-NP were 32, 102, and 209 h (or 1.3, 4.4, and 8.7 days) for 50%, 10%, and 1% retention, respectively. Thus, delivery of SDF in the NP-bound form extended the retention time of the protein in the lung by ~17-fold.

Figure 10. Retention time in the lung of SDF and SDF-NP after aerosol delivery.

Twelve μg of SDF in free (SDF) and NP form (SDF-NP) were aerosolized into the lungs of rats. At the indicated timepoints, lung tissues were harvested and tissue homogenate supernatants subsequently prepared. SDF concentrations in the lung were measured by ELISA. Data are mean ± SEM from the right and left lungs of three rats in each group and fit with exponential decay equations as indicated.

4. Discussion

This study demonstrates a method for converting a salt-susceptible DSCS NP to a salt-stable NP, which facilitates the in vivo application of the particle. DS and CS are polyanionic and polycationic molecules, respectively; multiple charge interactions between the polysaccharides led to the formation of DSCS NPs. Salt ions can compete with the electrostatic bonding between DS and CS, therefore causing the destabilization of the particle. To strengthen the particle in a salt environment, the current study introduced covalent bonding in DSCS NP by a crosslinking reaction. CS was chosen for the crosslinking, as the DS segments in the outer shell of the particle need to be preserved for protein incorporation. Additionally, CS was secluded in the core of in the particle as it was completely neutralized by DS (weight ratio of DS:CS = 4:1). By crosslinking the chitosan segments, the core of the particle was reinforced, and the particle became resistant to salt-induced collapse.

The incorporation of proteins into XDSCS NP is based on a heparin-binding principle. Proteins with a heparin-binding site(s) bind to the DS (a heparin analog, see below) on the surface of XDSCS NP. The main interaction between the protein and heparin is electrostatic, mediated by ion pairing between positively charged lysine, arginine, and occasionally histidine residues exposed on the surface of proteins and negatively charged sulfonic and carboxyl groups in the sulfated domain of heparin/heparan sulfate.(Gallagher, 2015) The heparin-binding site contains a cluster of basic residues, which can be present in the primary structure of protein, such as XBBXBX and XBBBXXBBX (B stands for basic residues), (Cardin and Weintraub, 1989) or formed after protein folding or dimerization appearing in the secondary, tertiary, or quaternary structure of proteins.(Gallagher, 2015) Published compilations of heparin-binding proteins (Ori et al., 2011; Vallet et al., 2021) continue to be updated. For the purposes of XDSCS NP incorporation, perhaps the easiest way to determine the binding is to mix the protein with the particles in PBS and examine the incorporated protein on an SDS gel. Proteins that do not bind to the particles are likely lacking the heparin-binding site, which, when necessary, could be added with a heparin binding tag during recombinant protein production.

DS is an analog of heparin and heparan sulfate. The common structural feature among these molecules is the sulfation of the polysaccharides: DS comprises sulfated repeating glucose units, while heparin and heparan sulfate contain sulfated repeating disaccharide units consisting of glucosamine and uronic acid.(Shriver et al., 2012; Turnbull et al., 2001) The degree of the sulfation in these molecules, however, is different. DS is homogeneously sulfated and contains 2.1–3.1 sulphonic groups per each glucose unit (sulfur content 17–20%). Heparin and heparan sulfate are heterogeneously sulfated in certain regions/domains of the molecules,(Shriver et al., 2012; Turnbull et al., 2001) with an average sulphonic group content in heparin of 1.1 per monosaccharide (sulfur content 11.3–12.4%) (Aviezer et al., 1994; Ziegler and Seelig, 2008), and in heparan sulfate of 0.39 per monosaccharide (sulfur content 5.51%). (Kuwabara et al., 2015) Thus, the overall sulfation density in these molecules is in the order of DS > heparin > heparan sulfate. The majority of heparin binding proteins bind to heparin tighter than heparan sulfate, (Peysselon and Ricard-Blum, 2014) likely due to the higher degree of sulfation in heparin. With the structural similarity of DS to heparin/heparan sulfate, it is assumed that heparin-binding proteins would bind to DS readily in the XDSCS NP and with a higher affinity than that to heparan sulfate. The data from this study are consistent with these assumptions, as the heparin-binding proteins, lysozyme, SDF, and VEGF, are incorporated into XDSCS NPs effectively instantaneously (Figure 5) and stably associate with the particles (Figure 8). The NP-incorporated SDF had a greater retention time in the lung than that of free SDF (Figure 10).

Heparan sulfate is ubiquitously present at the cell surface and in the extracellular matrix in virtually all multicellular eukaryotes. (Turnbull et al., 2001) A vast number of proteins are involved in the cell-cell communication in multicellular organisms; many of them are heparin binding proteins. (Ori et al., 2011) These proteins bind to heparan sulfate to facilitate their docking on the cell surface and to interact with receptors to trigger downstream signaling. The cell-cell communication plays critical roles in various aspects of mammalian biology, including embryonic development, morphogenesis, tissue injury repair, and immune defense. Heparin-binding proteins that orchestrate these functions include stem cell homing factors, morphogens, angiogenesis factors, growth/trophic factors, coagulation factors, cytokines, chemokines, and immune proteins. XDSCS NP was made for the delivery of these types of proteins. The incorporation of these proteins into the particles follows a natural process, which made the incorporation most efficient (Figure 5) and the activities of the proteins fully protected (Figures 7 and 8). Compared to protein production with gene overexpression systems (DNA/virus vectors), the XDSCS NP delivery may be preferred for its quantitative nature. Many of the cell-cell communication proteins are multifunctional, and their physiological activities depend on the quantity, time, and location of their expression. Uncontrolled overexpression of these proteins could even be detrimental under certain conditions. SDF, for example, could recruit progenitor cells for tissue regeneration or attract various types of leukocytes for inflammatory processes.(Karin, 2010; Mendez-Ferrer et al., 2008; Penn, 2010)

In the present study, lysozyme was used for routine quality checking of XDSCS NP preparation, as shown in Figure 6. Lysozyme is a heparin-binding protein found in egg white and also in human milk and exocrine pancreatic secretions,(Guyot et al., 2016; Wang and Kloer, 1984; Zou et al., 1992). The incorporation of lysozyme into XDSCS NP is comparable to that of SDF and VEGF (Figures 5 and 9); however, the cost of lysozyme is markedly less than the latter if purchased from commercial sources. It is, therefore, practical to use lysozyme to confirm the quality of the prepared XDSCS NP before the latter is used for the final incorporation of therapeutic proteins.

5. Conclusion

A chemical reaction method was developed in this study to covalently crosslink the core of DSCS NP with succinate, which markedly enhanced the salt tolerance of the particles from 0.09 M to 3 M. XDSCS NPs can rapidly and efficiently incorporate therapeutic heparin-binding proteins, VEGF and SDF, by simple mixing. The incorporated proteins were fully active and not released from the particles after a 14-day incubation at 37°C in PBS. When aerosolized into rat lungs, the particle-incorporated SDF showed a ~17-fold greater retention time than that of free SDF. These data suggest that XDSCS NPs could serve as useful nanocarriers for in vivo delivery of heparin-binding proteins to achieve sustained therapeutic effects.

Highlights.

Dextran sulfate-chitosan nanoparticles were covalently crosslinked

The salt stability of the particles was increased from 0.09 M to 3M

Heparin-binding proteins incorporated into the particles rapidly and efficiently

The incorporated proteins were fully active and stable at 37°C

Incorporated SDF-1α had a 17-fold longer retention in vivo than in its free form

Acknowledgements

Grants: (NIH) U54 HL119445, UO1 HG007690, RO1 HL155107, and RO1 HL155096 to JL; (AHA) AHA2017D007382, and AHA2020CV-19 to JL; and grants from NanoNeuron Therapeutics, Inc., and Astellas Institute of Regenerative Medicine to YYZ and JL.

Declaration of interests

Joseph Loscalzo reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Joseph Loscalzo reports financial support was provided by American Heart Association. Joseph Loscalzo reports financial support was provided by NanoNeuron Therapeutics, Inc. Joseph Loscalzo reports financial support was provided by Astellas Institute of Regenerative Medicine. Ying-Yi Zhang reports financial support was provided by NanoNeuron Therapeutics, Inc. Ying-Yi Zhang reports financial support was provided by Astellas Institute of Regenerative Medicine. Joseph Loscalzo has patent Particles for delivery of proteins and peptides licensed to NanoNeuron Therapeutics, Inc. Ying-Yi Zhang has patent Particles for delivery of proteins and peptides licensed to NanoNeuron Therapeutics, Inc.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Victoria A. Guarino: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing. Adam Blau: Investigation. Jack Alvarenga: Investigation. Joseph Loscalzo: Writing - Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. Ying-Yi Zhang: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Funding acquisition. All authors gave final approval of the version to be published; and agreed to take responsibility and be accountable for the contents of the article.

Competing interests

There are no relevant competing interests to report.

References

- Amara A, Lorthioir O, Valenzuela A, Magerus A, Thelen M, Montes M, Virelizier JL, Delepierre M, Baleux F, Lortat-Jacob H, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, 1999. Stromal cell-derived factor-1alpha associates with heparan sulfates through the first beta-strand of the chemokine. The Journal of biological chemistry 274, 23916–23925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviezer D, Levy E, Safran M, Svahn C, Buddecke E, Schmidt A, David G, Vlodavsky I, Yayon A, 1994. Differential structural requirements of heparin and heparan sulfate proteoglycans that promote binding of basic fibroblast growth factor to its receptor. The Journal of biological chemistry 269, 114–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardin AD, Weintraub HJ, 1989. Molecular modeling of protein-glycosaminoglycan interactions. Arteriosclerosis 9, 21–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimitrov DS, 2012. Therapeutic proteins. Methods in molecular biology 899, 1–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J, 2015. Fell-Muir Lecture: Heparan sulphate and the art of cell regulation: a polymer chain conducts the protein orchestra. International journal of experimental pathology 96, 203–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghadge SK, Muhlstedt S, Ozcelik C, Bader M, 2011. SDF-1alpha as a therapeutic stem cell homing factor in myocardial infarction. Pharmacology & therapeutics 129, 97–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyot N, Labas V, Harichaux G, Chesse M, Poirier JC, Nys Y, Rehault-Godbert S, 2016. Proteomic analysis of egg white heparin-binding proteins: towards the identification of natural antibacterial molecules. Scientific reports 6, 27974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karin N, 2010. The multiple faces of CXCL12 (SDF-1alpha) in the regulation of immunity during health and disease. Journal of leukocyte biology 88, 463–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krilleke D, Ng YS, Shima DT, 2009. The heparin-binding domain confers diverse functions of VEGF-A in development and disease: a structure-function study. Biochemical Society transactions 37, 1201–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuwabara K, Nishitsuji K, Uchimura K, Hung SC, Mizuguchi M, Nakajima H, Mikawa S, Kobayashi N, Saito H, Sakashita N, 2015. Cellular interaction and cytotoxicity of the iowa mutation of apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-IIowa) amyloid mediated by sulfate moieties of heparan sulfate. The Journal of biological chemistry 290, 24210–24221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauten EH, VerBerkmoes J, Choi J, Jin R, Edwards DA, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY, 2010. Nanoglycan complex formulation extends VEGF retention time in the lung. Biomacromolecules 11, 1863–1872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leader B, Baca QJ, Golan DE, 2008. Protein therapeutics: a summary and pharmacological classification. Nature reviews. Drug discovery 7, 21–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez-Ferrer S, Lucas D, Battista M, Frenette PS, 2008. Haematopoietic stem cell release is regulated by circadian oscillations. Nature 452, 442–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncalvo F, Martinez Espinoza MI, Cellesi F, 2020. Nanosized Delivery Systems for Therapeutic Proteins: Clinically Validated Technologies and Advanced Development Strategies. Frontiers in bioengineering and biotechnology 8, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ori A, Wilkinson MC, Fernig DG, 2011. A systems biology approach for the investigation of the heparin/heparan sulfate interactome. The Journal of biological chemistry 286, 19892–19904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penn MS, 2010. SDF-1:CXCR4 axis is fundamental for tissue preservation and repair. The American journal of pathology 177, 2166–2168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peysselon F, Ricard-Blum S, 2014. Heparin-protein interactions: from affinity and kinetics to biological roles. Application to an interaction network regulating angiogenesis. Matrix biology : journal of the International Society for Matrix Biology 35, 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricketts CR, 1952. Dextran sulphate--a synthetic analogue of heparin. The Biochemical journal 51, 129–133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz C, Domard A, Viton C, Pichot C, Delair T, 2004. Versatile and efficient formation of colloids of biopolymer-based polyelectrolyte complexes. Biomacromolecules 5, 1882–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriver Z, Capila I, Venkataraman G, Sasisekharan R, 2012. Heparin and heparan sulfate: analyzing structure and microheterogeneity. Handbook of experimental pharmacology, 159–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull J, Powell A, Guimond S, 2001. Heparan sulfate: decoding a dynamic multifunctional cell regulator. Trends in cell biology 11, 75–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallet SD, Clerc O, Ricard-Blum S, 2021. Glycosaminoglycan-Protein Interactions: The First Draft of the Glycosaminoglycan Interactome. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society 69, 93–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang CS, Kloer HU, 1984. Purification of human lysozyme from milk and pancreatic juice. Analytical biochemistry 139, 224–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu D, Esko JD, 2014. Demystifying heparan sulfate-protein interactions. Annual review of biochemistry 83, 129–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin T, Bader AR, Hou TK, Maron BA, Kao DD, Qian R, Kohane DS, Handy DE, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY, 2013. SDF-1alpha in glycan nanoparticles exhibits full activity and reduces pulmonary hypertension in rats. Biomacromolecules 14, 4009–4020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman P, Wang J, Blau A, Wang W, Li T, Kohane DS, Loscalzo J, Zhang YY, 2016. Incorporation of heparin-binding proteins into preformed dextran sulfate-chitosan nanoparticles. International journal of nanomedicine 11, 6149–6159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziegler A, Seelig J, 2008. Binding and clustering of glycosaminoglycans: a common property of mono- and multivalent cell-penetrating compounds. Biophysical journal 94, 2142–2149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zou S, Magura CE, Hurley WL, 1992. Heparin-binding properties of lactoferrin and lysozyme. Comparative biochemistry and physiology. B, Comparative biochemistry 103, 889–895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]