Abstract

Importance: Children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) may experience sleep difficulties that worsen into adulthood and negatively influence both child and family, yet the experience is not well understood. Understanding the family’s experience can inform occupational therapy providers, future research, and practice guidelines.

Objective: To examine experiences surrounding sleep for families raising a young adult with ASD (YA-ASD).

Design: Qualitative study in the phenomenological tradition of Moustakas (1994). Experienced researchers analyzed transcripts from in-depth, in-person interviews to triangulate data, distill themes, and construct the essence of family experience. Trustworthiness was established through member checking, audit trails, and epoché diaries that were maintained throughout data analyses.

Setting: Community setting (large city in the northeastern United States).

Participants: People who self-identified as living in a family arrangement that included a YA-ASD age 15–21 yr, able to verbally participate in English. Families with children diagnosed with developmental disabilities other than ASD were excluded.

Results: Six eligible families identified through volunteer sampling participated. The participants’ sociodemographic diversity was limited across household income, education level, and ethnicity. All YA-ASD in this study were limited verbally and unable to contribute. Analyses of interview transcripts revealed five themes that form the essence of the families’ experience surrounding sleep.

Conclusions and Relevance: Sleep issues for YA-ASD continue into adulthood and affect the entire family because of continuous co-occupation; occupational therapy support is therefore important for families of YA-ASD. The lack of effective evidence-based interventions supporting the YA-ASD population also reveals an area for growth.

What This Article Adds: The results indicate the importance of addressing sleep for YA-ASD and their families in occupational therapy practice because of its considerable impact on family life.

Because sleep issues have a considerable impact on family life, occupational therapy support is important young adults with ASD and their families.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) significantly affects family life (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; Ludlow et al., 2012). Families’ occupational lives revolve around the needs of their children with ASD to ensure that those needs are met (DeGrace, 2004; Hoogsteen & Woodgate, 2013; Nicholas et al., 2016). Although the understanding of family occupation and ASD is evolving, sleep is arguably the most affected and least studied occupation (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; Kirkpatrick et al., 2019).

Sleep, a vital occupation across the life course (AOTA, 2020; Tester & Foss, 2018), contributes significantly to the daily function, health, and well-being of both individuals and families (Buxton et al., 2015; McCombie & Wolfe, 2017). Research indicates that up to 85% of children with ASD have difficulties with sleep compared with typically developing peers (Blackmer & Feinstein, 2016; Chen et al., 2021; Souders et al., 2017; van der Heijden et al., 2018). Although for typically developing children, sleep difficulties usually resolve with age, children with ASD often demonstrate unresolved or intensified sleep challenges into adolescence and young adulthood (Goldman et al., 2012; Hodge et al., 2014). Sleep disturbance should greatly concern occupational therapy practitioners because it is associated with poorer health-related quality of life (Deserno et al., 2019; Kuhlthau et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2020) and increased challenging behaviors among the population with ASD (Bangerter et al., 2020; Mazurek & Sohl, 2016). A call for funding by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences stressed the need for more research to support pediatric sleep concerns (Gruber et al., 2016).

Method

Design

In this phenomenological study, we investigated the experience of sleep for families of young adults with autism spectrum disorder (YA-ASD) through semistructured family interviews (Moustakas, 1994). Because sleep problems often persist from early childhood, we targeted families with YA-ASD to discuss and understand their experiences with sleep over time. This study received institutional review board approval.

Participants

Participants were recruited through social media postings, emails, and flyers distributed at local schools and therapy centers known to the first author (Nicole Halliwell). Interested families contacted the first author, who followed up by phone or email to discuss study-related information, determine eligibility, and obtain verbal consent. Families met inclusion criteria if they had a YA-ASD age 15 to 21 yr living at home and members of the family other than the YA-ASD were able to verbally participate in the interview process in English. The inclusion of 15- to 17-yr-olds as young adults reflects the expanding awareness of the need to begin focusing on the transition to adulthood for this population at a younger age. Families with children diagnosed with developmental disabilities other than ASD were excluded. Family composition was self-identified, and that composition was used for interviews to understand the experience of sleep as a co-constructed family occupation.

Six eligible families participated: 4 two-parent households and 2 single-parent households. Only 1 family included an adult sibling living in the home. All YA-ASD in this study were limited verbally and unable to contribute to the interview. Relevant demographic information is presented in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Demographic Information for Parents, Adults, and Children in the Household

| Family No. | Gender | Age, yr | Race | Employment Status | Marital Status | Education Level | Annual Household Income, $ |

| 1 a | Female | 40–49 | White | Full time | Separated | Graduate | >65,000 |

| 2 a | Male | 40–49 | White | Full time | Married | Bachelor’s | >65,000 |

| 2 a | Female | 40–49 | White | Part time | Married | Graduate | |

| 2 | Male | 20–29 | White | Student | Single | Some college | |

| 2 | Male | 19 | White | n/a | |||

| 2 | Male | 14 | White | n/a | |||

| 2 | Female | 14 | White | n/a | |||

| 2 | Male | 9 | White | n/a | |||

| 3 a | Female | 50–59 | Other | Part time | Divorced | <High school | <25,000 |

| 3 | Male | 20–29 | Other | Full time | Single | Bachelor’s | |

| 4 a | Female | 40–49 | Hispanic | Full time | Married | Some college | 25,000–44,999 |

| 4 a | Male | 40–49 | Hispanic | Full time | Married | High school | |

| 4 | Male | 20–29 | Hispanic | Full time | Married | Associate’s | |

| 5 a | Male | 50–59 | White | Full time | Married | Graduate | >65,000 |

| 5 a | Female | 50–59 | White | Full time | Married | Graduate | |

| 5 a | Male | 20–29 | White | Student | Single | Bachelor’s | |

| 6 a | Male | 60–69 | White | Full time | Married | Graduate | <65,000 |

| 6 a | Female | 50–49 | Hispanic | Full time | Married | Graduate |

Note. n/a = not applicable.

Family interview participant.

Table 2.

Demographic Information for Young Adults With Autism Spectrum Disorder in Household

| Family No. | Gender | Age, yr | Race | Communication Level | Comorbidities |

| 1 | Male | 18 | White | Partially verbal | Anxiety disorder |

| 1 | Female | 16 | White | Partially verbal | Anxiety disorder |

| 2 | Male | 17 | White | Partially verbal | Intellectual disability |

| 3 | Male | 19 | Other | Nonverbal | Attention deficit disorder, Epilepsy/seizure disorder, learning disability |

| 4 | Male | 16 | Hispanic | Nonverbal | None |

| 5 | Male | 16 | White | Partially verbal | Anxiety disorder, learning disability |

| 6 | Male | 21 | White | Nonverbal | Intellectual disability |

Procedure

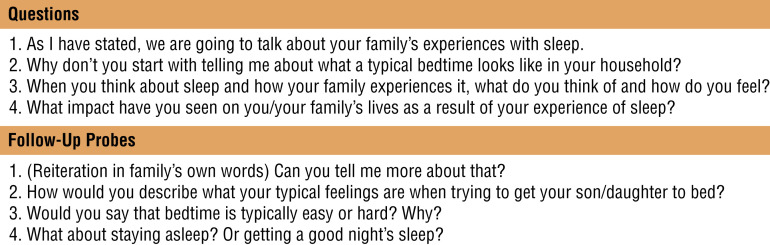

The first author conducted 60- to 90-min interviews of the families in their homes (Figure 1). The interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and deidentified before analysis. Interviews were conducted until saturation of the data, or hearing similar core experiences across families, was achieved (Moustakas, 1994). Interviewing 6 families is consistent with previous phenomenological studies that have used family interviews (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; DeGrace, 2004; Suarez et al., 2014).

Figure 1.

Semistructured interview questions.

Data Analysis

The research team consisted of the first author, an entry-level professional occupational therapy student (Katelyn Harris), and two occupational therapy faculty members (Julie D. Smith and Beth W. DeGrace), both with qualitative research experience focused on the ASD population. The first author was responsible for recruitment, data collection, and data management and led the data analysis process. Over 2 mo of weekly meetings, the team used four stages of data analysis: (1) epoché, (2) phenomenological reduction, (3) imaginative variation, and (4) synthesis (Moustakas, 1994).

All transcripts were reviewed and cross-checked with digital audio recordings. Each transcript was analyzed individually by at least three of the researchers, and coding results were compared across three or more researchers to triangulate. Families confirmed accuracy with verbal summaries of their responses. Audit trails and epoché diaries were maintained throughout data analyses and used as an additional source of data to achieve rigor.

Results

This study revealed five emotional themes: (1) endlessness, (2) attempts to manage, (3) difficulty, (4) persistence, and (5) the need to restructure.

Theme 1: Endlessness—“We’re Never Done”

Endlessness captures the relentless nature of ASD, which extends even into sleep. Each family reported making continuous efforts over time to facilitate sleep, leaving them taxed and overwhelmed because the “stress is 24 hours” (Family 1) and they “don’t have the luxury of saying . . . I can sleep a little longer” (Family 2). The lack of YA-ASD self-sufficiency generated feelings of hypervigilance, caused considerable stress, and denied parents rest or recuperation because they had to “[sleep] with one ear open” (Family 5).

The experience of sleep was complicated because life demands continue, regardless of inadequate sleep: “When he didn’t sleep at all . . . I still had to go to work. . . . I just had to keep going” (Family 1). This lack of physical and mental restoration made parental functions challenging or overwhelming, affecting the performance of other life occupations by both parents and the YA-ASD:

If either of us are not feeling like we got enough sleep, it really impacts the day. It makes taking care of the kids and being available to them mentally much more difficult . . . if they don’t sleep well, they’re not able to focus as well in school. (Family 2)

One family reported, “You never have your own time. It’s affecting our lives, because who [does] not want to have a life . . . [to] do something for you[rselves]?” (Family 4).

Theme 2: Attempts to Manage—“We Tried Everything”

This theme captures the experience of trying to mitigate unrelenting sleep challenges presented and faced by YA-ASD. Families tried many strategies, including calming teas, melatonin, sensory activities, diet changes, essential oils, pre-bedtime music interventions, and changes to the sleep environment (e.g., blackout curtains or sound machines). “We tried different things . . . like bath[s], relaxing things. And I think instead of work[ing], it got worse” (Family 4). Limited success and wasted resources caused frustration.

Theme 3: Difficulty—“It’s Difficult, So Difficult”

Families stressed the extreme difficulty they experienced, using terms like nightmare and absolute hell. Many YA-ASD engaged in highly disruptive nighttime activities, such as “walking around/pacing,” “clapping/making loud noises,” “watching videos,” “ransacking the kitchen,” seeking “midnight snacks,” “painting the walls,” and “kicking the door/wall.” These activities had a spillover effect on family members:

If everyone’s calm, everyone has a good night’s sleep, we kind of get a good day. If one of them had a bad sleep, then I had a bad sleep . . . that definitely has a negative impact on the next day. (Family 1)

Families expressed complex feelings of frustration, anger, and guilt from living with the sleep difficulties of their YA-ASD. Parents reported clumsiness; headaches; loss of patience; and strained marital relationships, including separation or divorce. The transcripts revealed how stressful the lack of sleep could be, with words such as trauma, wrecked, debilitating, hell, torture, and nightmare noted.

Theme 4: Persistence—“Because It’s Not Going to Change”

This theme represents the experience of hopelessness when sleep issues recurred or worsened with transitions or life changes: “Any time we have to do some change, like medication, it’s hard. We know that we have [it] again . . . the sleep problem” (Family 4). Realizing that the sleep difficulties of their YA-ASD would likely never fully resolve caused feelings of hopelessness. Families wanted improvement in sleep but also feared negative side effects from some efforts:

We never want to have the drugs change who he is. . . . We’ve always been very careful. . . . We didn’t want him to be a zombie . . . to lose his personality . . . and our choice has been to live through some of these issues. (Family 5)

Parents reported no expectation for restful sleep: “I feel like it’s a normal life for me. . . . But it’s hard to accept that I could be sleeping a full night.” (Family 3)

Theme 5: Need to Restructure—“So We Gotta Change Our Life for Him”

Families concluded that they needed to restructure and moved away from efforts to change the sleep habits of their YA-ASD, focusing instead on restructuring their lives to support it. This included sacrificing the ability to relax while using a family teamwork approach to try to balance and maintain individual health:

We had a good understanding when the other one needed a break . . . just trying to balance it out so that who’s in the worst shape needs to sleep . . . because if neither one of us were healthy, then we couldn’t deal. (Family 5)

Families described using highly structured routines, hypervigilance, and constructing their lives around the needs of the YA-ASD to preserve and maintain family life. Although restructuring caused some familial strain, families expressed feeling more positive and better overall:

If it’s raining, you’re going to complain about it raining? No. It’s not going to help, right? So you’re going to accept, “Oh, it’s raining. So what are you going to do? Get [an] umbrella.” . . . That’s life . . . we’re not sleeping, but we’re happy. So we are in the rain, we’re dancing in the rain now. (Family 4)

Restructuring family life seemed to contribute positively to the families’ experience, even though sleep remained difficult for all.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first phenomenological study to examine the sleep experiences of families raising a YA-ASD. The verbatim representations of the five themes, when combined, become a powerful summary of the essence of this experience: “We’re never done. We tried everything. It’s difficult, so difficult. Because it’s not going to change. So we gotta change our life for him.”

As families navigated the occupation of sleep, they felt that their responsibility toward their YA-ASD was never ending and, despite managing over time, the impact on the families continued to be extremely difficult. Although the families felt the sleep experience could be improved, they appeared to accept the fact that sleep challenges would never fully resolve. Therefore, they relinquished their sleep preferences and patterns to meet the needs of the YA-ASD. These findings are congruent with those of studies that have examined everyday life for families raising children with autism, which identified four broad themes: (1) pervasiveness of ASD; (2) feeling overwhelmed, stressed, frustrated, and anxious; (3) structuring life around ASD; and (4) feelings of judgment, exclusion, and isolation (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; DeGrace, 2004; Hoogsteen & Woodgate, 2013; Kirkpatrick et al., 2019; Ludlow et al., 2012; Nicholas et al., 2016; Swinth et al., 2015). The similarity of these themes supports the established research literature describing the pervasive effect of ASD on the family and shows that ASD affects the occupation of sleep.

Despite differences in family composition and socioeconomic level, the experiences of the families in this study surrounding sleep were similar. Every YA-ASD demonstrated difficulty with the occupation of sleeping, including falling asleep, staying asleep, and engaging in various disruptive nighttime activities. To improve sleep, each family spent time and energy exploring myriad tools and strategies, seeking professional help (including from occupational therapy practitioners), and continually working to accommodate the needs of the YA-ASD. This persistent family effort often led to substantial experiences of occupational imbalance, which raises concerns for family well-being. This persistence resonates with existing family research emphasizing the toll that seeking services has on families raising a child with ASD (Hodgetts et al., 2014).

During analyses, the experience of constantly being needed, or co-occupation for sleep, elicited discussions about the similarities between parenting a YA-ASD and parenting an infant. The sleep disruption for parents of typically developing infants, although it prompts an occupational imbalance, is temporary (Creti et al., 2017). As children develop, the need for caregiving and co-occupation decreases, but this is not the experience of families raising YA-ASD (Bessette Gorlin et al., 2016; DeGrace, 2004; Hoogsteen & Woodgate, 2013; Ludlow et al., 2012; Nicholas et al., 2016; Suarez et al., 2014; Swinth et al., 2015). In contrast, this study revealed that families continue to support the sleep patterns of a YA-ASD and thus are co-occupied, limiting occupational engagement and threatening the health and well-being of all family members.

The American Academy of Neurology recently published evidence-supported practice guidelines for the treatment of sleep disturbances in children and adolescents with ASD. They recommended four approaches: (1) addressing coexisting medical conditions, (2) implementing behavioral strategies, (3) using melatonin, and (4) exploring complementary alternative medicine (Buckley et al., 2020). The results of this study indicate that these strategies and other environmental modifications that are conventionally recommended to support sleep (e.g., good sleep hygiene, melatonin) may not adequately help YA-ASD and their families.

Limitations and Future Research

Future studies might benefit from a larger sample size of YA-ASD participants, families with greater socioeconomic or ethnic diversity, YA-ASD with increased communicative participation in the interview process, or the use of a mixed-methods design to incorporate an objective sleep measure. Of note, despite vast distribution of recruitment materials across multiple platforms, all families who elected to participate were known to the first author. We believe this phenomenon is a function of the inherent intimacy surrounding the topic of sleep to families raising YA-ASD and the trust required to openly share these experiences in an in-person interview. This research demonstrates the need for further studies designed to demonstrate the effectiveness of occupational therapy providers’ interventions and strategies to support sleep for families raising children with ASD.

Implications for Occupational Therapy Practice

Research using qualitative methodology both adds value to a body of literature and informs practice by focusing on the values and opinions of the participants, being client centered while “deepening practitioners’ understanding, and by enhancing capacity for empathy and therapeutic use of self” (Tomlin & Swinth, 2015, p. 2). The lack of evidence-based interventions supporting people with ASD also reveals a considerable area of growth for research and warrants further investigation to identify helpful strategies for improving sleep for this population and then to use those strategies in research to build the evidence in support of the effective implementation of sleep interventions across disciplines. The families in this study reported an overwhelming appreciation for the time we took to understand their sleep experiences, which reinforced the notion of sleep as an overwhelming experience that often is not given adequate attention by health professionals.

This study has implications for occupational therapy practice because it

reveals the profound importance of an overlooked occupation—sleep—and its influence on the health, participation, and occupational identity of the person with ASD and their family;

indicates the significant power of the trust built between occupational therapy providers and the families they serve as an asset to better understand the impact of sleep difficulties on family life and generate potential supportive interventions; and

highlights the opportunity for occupational therapy providers to address occupational performance of sleep, specifically for families with a YA-ASD.

Conclusion

This study provides insight into the ways family life is transformed by and revolves around the needs of the YA-ASD. Our investigation unveiled the fact that challenges persist even during sleep, further confirming the pervasive influence of ASD on family life. The results suggest that families have little opportunity for restoration or reprieve and, more important, reveal a notable disconnect between the standard recommendations from health professionals to support sleep for this population and their real-world efficacy.

Acknowledgments

We thank the participant families, without whom this study would not have been possible, for graciously opening their homes and openly sharing their experiences. Nicole Halliwell thanks the data analysis team, her thesis committee, and her close family and friends for their unwavering and continued support throughout the research and publication process. The contents of this article were supported by a Research and Creativity Grant awarded by the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Allied Health department and developed under a grant from the U.S. Department of Education (H325K120310); however, the contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the U.S. Department of Education, and readers should not assume endorsement by the U.S. government.

References

- American Occupational Therapy Association. (2020). Occupational therapy practice framework: Domain and process (4th ed.). American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 74(Suppl. 2), 7412410010. 10.5014/ajot.2020.74S2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangerter, A. , Chatterjee, M. , Manyakov, N. V. , Ness, S. , Lewin, D. , Skalkin, A. , . . . . Pandina, G. (2020). Relationship between sleep and behavior in autism spectrum disorder: Exploring the impact of sleep variability. Frontiers in Neuroscience , 14 , 211. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bessette Gorlin, J. , McAlpine, C. P. , Garwick, A. , & Wieling, E. (2016). Severe childhood autism: The family lived experience. Journal of Pediatric Nursing , 31 , 580–597. 10.1016/j.pedn.2016.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmer, A. B. , & Feinstein, J. A. (2016). Management of sleep disorders in children with neurodevelopmental disorders: A review. Pharmacotherapy , 36 , 84–98. 10.1002/phar.1686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley, A.W. , Hirtz, D. , Oskoui, M. , Armstrong, M. A. , Batra, A. , Bridgemohan, C. , . . . Ashwal, S. (2020). Practice guideline: Treatment for insomnia and disrupted sleep behavior in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology , 94 , 392–404. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000009033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buxton, O. M. , Chang, A. M. , Spilsbury, J. C. , Bos, T. , Emsellem, H. , & Knutson, K. L. (2015). Sleep in the modern family: Protective family routines for child and adolescent sleep. Sleep Health , 1 , 15–27. 10.1016/j.sleh.2014.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X. , Liu, H. , Wu, Y. , Xuan, K. , Zhao, T. , & Sun, Y. (2021).Characteristics of sleep architecture in autism spectrum disorders: A meta-analysis based on polysomnographic research. Psychiatry Research , 296 , 113677. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creti, L. , Libman, E. , Rizzo, D. , Fichten, C. S. , Bailes, S. , Tran, D.-L. , & Zelkowitz, P. (2017). Sleep in the postpartum: Characteristics of first-time, healthy mothers. Sleep Disorders , 2017 , 8520358. 10.1155/2017/8520358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGrace, B. W. (2004). The everyday occupation of families with children with autism. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 58 , 543–550. 10.5014/ajot.58.5.543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deserno, M. K. , Borsboom, D. , Begeer, S. , Agelink van Rentergem, J. A. , Mataw, K. , & Geurts, H. M. (2019). Sleep determines quality of life in autistic adults: A longitudinal study. Autism Research , 12 , 794–801. 10.1002/aur.2103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, S. E. , Richdale, A. L. , Clemons, T. , & Malow, B. A. (2012). Parental sleep concerns in autism spectrum disorders: Variations from childhood to adolescence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 42 , 531–538. 10.1007/s10803-011-1270-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber, R. , Anders, T. F. , Beebe, D. , Bruni, O. , Buckhalt, J. A. , Carskadon, M. A. , . . . Wise, M. S. (2016). A call for action regarding translational research in pediatric sleep. Sleep Health , 2 , 88–89. 10.1016/j.sleh.2016.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodge, D. , Carollo, T. M. , Lewin, M. , Hoffman, C. D. , & Sweeney, D. P. (2014). Sleep patterns in children with and without autism spectrum disorders: Developmental comparisons. Research in Developmental Disabilities , 35 , 1631–1638. 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.03.037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgetts, S. , McConnell, D. , Zwaigenbaum, L. , & Nicholas, D. (2014). The impact of autism services on mothers’ occupational balance and participation. OTJR: Occupation, Participation and Health , 34 , 81–92. 10.3928/15394492-20130109-01 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogsteen, L. , & Woodgate, R. L. (2013). Centering autism within the family: A qualitative approach to autism and the family. Journal of Pediatric Nursing , 28 , 135–140. 10.1016/j.pedn.2012.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, B. , Gilroy, S. P. , & Leader, G. (2019). Qualitative study on parents’ perspectives of the familial impact of living with a child with autism spectrum disorder who experiences insomnia. Sleep Medicine , 62 , 59–68. 10.1016/j.sleep.2019.01.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhlthau, K. A. , McDonnell, E. , Coury, D. L. , Payakachat, N. , & Macklin, E. (2018). Associations of quality of life with health-related characteristics among children with autism. Autism , 22 , 804–813. 10.1177/1362361317704420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, R. , Dong, H. , Wang, Y. , Lu, X. , Li, Y. , Xun, G. , . . . Zhao, J. (2020). Sleep problems of children with autism may independently affect parental quality of life. Child Psychiatry and Human Development , 52, 488–499. 10.1007/s10578-020-01035-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow, A. , Skelly, C. , & Rohleder, P. (2012). Challenges faced by parents of children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Health Psychology , 17 , 702–711. 10.1177/1359105311422955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazurek, M. O. , & Sohl, K. (2016). Sleep and behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders , 46 , 1906–1915. 10.1007/s10803-016-2723-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCombie, R. P. , & Wolfe, R. (2017). Sleep as an occupation: Perceptions and assessment behaviors of practicing occupational therapists. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 71(4, Suppl. 1), 7111510172. 10.5014/ajot.2017.71S1-PO1123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moustakas, C. E. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage. 10.4135/9781412995658 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholas, D. B. , Zwaigenbaum, L. , Ing, S. , MacCulloch, R. , Roberts, W. , McKeever, P. , & McMorris, C. A. (2016). “Live it to understand it”: The experiences of mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder. Qualitative Health Research , 26 , 921–934. 10.1177/1049732315616622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souders, M. C. , Zavodny, S. , Eriksen, W. , Sinko, R. , Connell, J. , Kerns, C. , . . . Pinto-Martin, J. (2017). Sleep in children with autism spectrum disorder. Current Psychiatry Reports , 19 , 34. 10.1007/s11920-017-0782-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suarez, M. A. , Atchison, B. J. , & Lagerwey, M. (2014). Phenomenological examination of the mealtime experience for mothers of children with autism and food selectivity. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 68 , 102–107. 10.5014/ajot.2014.008748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swinth, Y. , Tomlin, G. , & Luthman, M. (2015). Content analysis of qualitative research on children and youth with autism, 1993–2011: Considerations for occupational therapy services. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 69 , 6905185030. 10.5014/ajot.2015.017970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tester, N. J. , & Foss, J. J. (2018). Sleep as an occupational need. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 72 , 7201347010. 10.5014/ajot.2018.020651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlin, G. S. , & Swinth, Y. (2015). Contribution of qualitative research to evidence in practice for people with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal of Occupational Therapy , 69 , 6905360010. 10.5014/ajot.2015.017988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Heijden, K. B. , Stoffelsen, R. J. , Popma, A. , & Swaab, H. (2018). Sleep, chronotype, and sleep hygiene in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, autism spectrum disorder, and controls. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry , 27 , 99–111. 10.1007/s00787-017-1025-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]