Abstract

Objective:

To examine the association between headache and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of American youth.

Study Design:

We used the National Comorbidity Survey – Adolescent Supplement to assess sex specific prevalence of lifetime migraine and non-migraine headache using modified International Headache Society criteria and examine associations between headache subtypes and DSM-IV mental disorders. Adolescent report (n=10,123) was used to identify headache subtypes and anxiety, mood, eating, and substance use disorders. ADHD and behavior disorder were based on parent report (n=6,483). Multivariate logistic regression analyses controlling for key demographic characteristics were used to examine associations between headache and mental disorders.

Results:

Headache was endorsed by 26.9% (SE=0.7) of the total sample and was more prevalent among females. Youth with headache were more than twice as likely (OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.94 −3.83) to meet criteria for a DSM-IV disorder. Migraine, particularly with aura, was associated with depression and anxiety (adjusted OR 1.90–2.90) and with multiple classes of disorders.

Conclusions:

Adolescent headache, particularly migraine is associated with anxiety, mood, and behavior disorders in a nationally representative sample of US youth. Headache is highly prevalent among youth with mental disorders, and youth with headache should be assessed for comorbid depression and anxiety that may influence treatment, severity and course of both headache and mental disorders.

INTRODUCTION

Headache is a common physical complaint among children and adolescents. Primary headache subtypes include migraine (with and without aura), tension-type, and cluster headache. Tension-type headaches are the most common headache subtype among youth, with a prevalence rate 2–3 times that of migraine [1, 2]. The prevalence of headache, regardless of subtype, is roughly equal among males and females prior to the age of 12 years [3]. Rates increase, and gender differences emerge by early adolescence with higher rates of headache reported by females during adolescence and adulthood [2, 3]. Recurrent headache is associated with functional impairment and decreased quality of life [4, 5]. Similar patterns hold true for mental disorders. As rates of depression and anxiety increase during adolescence, gender differences emerge, and affected youth show impairments in social, familial, and academic domains [6, 7].

Headache, especially migraine, is associated with depression and anxiety in adults [8], but there are limited data from community samples of youth. Two recent population-based studies suggest that the association between headache and mood and anxiety disorders may be present by adolescence. Recurrent headache was associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety in the Young-Hunt study, a cross-sectional population-based sample of 4872 youth ages 12–17 years in Norway [9]. Among older youth (ages 15–17 years), recurrent headache was also associated with attention difficulties [9]. Likewise, migraine was significantly associated with both mood (aOR 3.06–4.59) and anxiety disorders (aOR 1.87–4.21) in six cycles of the Canadian Community Health Survey, a cross-sectional population-based study of 61,375 Canadian youth ages 12–19 years [10].

While these recent studies suggest that associations between mood and anxiety disorders and headache are present in adolescents as well as adults, no prior community studies have included a comprehensive assessment of both mental disorders and headache subtypes in adolescents. The association between mental health disorders in adolescents and migraine with aura, which has been linked to more severe psychopathology in a small number of studies, remains largely unexplored [11–13]. Moreover, although puberty is a time in which sex differences in the rates of both mood disorders and headache emerge, previous large-scale studies have not examined sex-differences in the associations between headache and mental disorders.

In the current study, we examine the association between headache subtypes and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of American youth. We determine the sex specific prevalence of lifetime migraine and non-migraine headache and examine sex-specific associations between headache subtypes and a broad spectrum of mental disorders.

METHODS

Sample

The National Comorbidity Survey – Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A) was a nationally representative population-based survey of adolescents in the continental United States (US). In-person interviews were conducted by trained lay interviewers from the Survey Research Center at the University of Michigan with youth ages 13–18 years between February 2001 and January 2004. The interview was a version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WHO-CIDI), which assesses psychiatric diagnoses as well as chronic medical conditions and was modified for use with adolescents [14, 15]. Parent report on medical and mental health history collected via self-administered questionnaire (PSAQ) was available for a subset of the sample (n=6483) [15]. A dual sampling frame was used, including 904 adolescent residents of households participating in the National Comorbidity Replication survey and 9,244 adolescents who attended school in the same counties, with an overall response rate of 75.6% of adolescents and 63% of parents [16]. Non-student respondents were excluded, leaving a total sample of 10,123 for analyses. Separate weighting schema were used to ensure that the household and school samples accurately reflected the US population with regards to sociodemographic and geographic variables [17]. Recruitment, consent, and field procedures were approved by the Human Subjects Committees at Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan.

Definition of Migraine and Non-migraine Headaches

As noted above, the WHO-CIDI based NCS-A adolescent interview included a section regarding chronic physical conditions. To assess headache, participants were initially asked if they had ever in their life experienced “frequent or very bad headaches.” Participants who endorsed a lifetime headache history were then asked a series of questions designed to elicit information about headache subtype. The International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-III) was used to define headache subtype and modified ICHD-III criteria were used to classify headaches as migraine with aura, migraine without aura, and non-migraine headache [18]. Slight modifications were needed because the interview included queries regarding all migraine criteria except for number of attacks and relation of headache to physical activity [19]. Migraine with aura was defined by endorsement of either partial loss of vision, or seeing spots, lights, or heat waves prior to headache onset. Visual symptoms are present in an estimated 98–99% of migraine with aura cases and 93% of pediatric cases [20, 21]; thus other aura symptoms were not queried. Non-migraine headache included tension-type headache as well as unclassifiable headache and other headache subtypes. The WHO-CIDI headache questions used in the NCS-A study did not query “pressing or tightening” non-pulsatile pain, so to avoid the misclassification of tension-type headache, non-migraine headache subtypes were not differentiated in this manuscript.

Assessment of Psychiatric Disorders

Trained lay interviewers administered a modified version of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) to adolescents while their parents completed a complementary version by self-administered questionnaire [15, 17]. The WHO-CIDI is a structured interview that includes assessment of mood (major depressive disorder, mania), anxiety (social phobia, specific phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder), attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, disruptive behavior disorders (conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder), eating disorders (anorexia, bulimia, binge eating), and substance use disorders (alcohol and drug abuse/dependence, nicotine dependence). Information regarding symptoms of mental health disorders, their duration, and associated distress and impairment was collected from both adolescents and parents. Adolescent report alone was used to assess diagnostic criteria for mood, anxiety, eating, and substance use disorders. For conduct disorder (CD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), diagnostic data from both the parent and adolescent were combined and classified as positive if either informant endorsed sufficient symptoms for the diagnosis to be made. Only parent report was used for the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Decisions regarding the use of parent and adolescent report for case definition were based on information gained in the NCS-A Clinical Reappraisal Study which was used to establish the concordance between the NCS-A/WHO-CIDI diagnoses and blinded clinical diagnoses [22, 23] Definitions of all psychiatric disorders adhered to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria [15, 24].

Data Analysis

Cross-tabulations were used to calculate estimates of lifetime prevalence for the entire sample and by demographic characteristics. Prevalence of 16 specific DSM-IV disorders in 6 overarching classes of disorders (mood, anxiety, substance use, eating, ADHD, and disruptive behavior) were estimated by headache status. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were used to evaluate the associations between headache and lifetime DSM-IV mental disorders. Ad hoc subgroup comparisons were performed including migraine with aura versus migraine without aura, migraine (with or without aura) versus non-migraine headache, and headache (all types) versus no headache. Associations between both individual DSM-IV disorders and classes of disorders were examined, and analyses were conducted controlling for demographic characteristics that were associated with headache in the univariate analyses (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, parental education); models also progressively adjusted for both demographic variables and the presence of other lifetime DSM-IV disorders. Adjusted odds ratios (aORs) are the exponentiated values of multivariate logistic regression coefficients. Confidence intervals (95% CI) of the aORs were calculated based on design-adjusted variances. The design-adjusted Wald chi-square test was used to examine the statistical significance based on two-sided tests evaluated at the 0.05 level of significance. Given the considerable association between mood and anxiety disorders in the sample, we also examined associations between headache subtypes and a cross-classification of anxiety and depression. Sex-stratified analyses are presented in the supplemental material. Statistical analyses were completed in the SUDAAN software (version 11) using the Taylor series linearization method to account for the complex survey design.

RESULTS

More than a quarter (26.9% (SE=0.7)) of adolescents reported a lifetime history of headache. Migraine with aura was endorsed by 1.6%, migraine without aura by 11.0%, and non-migraine headache by 14.3%. All types of headache were more prevalent among females than males and sex differences were evident even among the youngest portion of the sample (youth ages 13–14 years). Rates of headache differed across racial/ethnic groups and by parental education, but not by age or family income (Table 1).

Table 1.

Lifetime prevalence of headache by sample characteristics, NCS-A (N=10,123)

| N | MA | MO | NMH | No HA | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=171 | n=1074 | n=1466 | n=7412 | ||||

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | ||||

| Total | 10,123 | 1.6 (0.2) | 11.0 (0.5) | 14.3 (0.7) | 73.2 (0.7) | - | |

| Age group | 13–14 years | 3,870 | 1.4 (0.3) | 9.8 (0.6) | 15.9 (1.0) | 72.8 (1.0) | 0.07 |

| 15–16 years | 3,897 | 1.8 (0.4) | 12.0 (0.9) | 14.1 (0.8) | 72.1 (1.3) | ||

| 17–18 years | 2,356 | 1.5 (0.3) | 10.9 (1.1) | 11.9 (1.3) | 75.7 (1.7) | ||

| Sex | Female | 5,170 | 2.1 (0.3) | 13.7 (0.8) | 16.5 (0.8) | 67.8 (1.0) | <.001 |

| Male | 4,953 | 1.2 (0.2) | 8.4 (0.5) | 12.2 (1.0) | 78.2 (1.0) | ||

| Race/Ethnicity | Hispanic | 1,914 | 1.8 (0.5) | 8.9 (0.7) | 15.9 (1.9) | 73.4 (2.2) | <.001 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1,953 | 0.7 (0.2) | 10.9 (1.3) | 20.9 (1.1) | 67.5 (1.6) | ||

| Other | 622 | 1.7 (0.7) | 9.1 (2.5) | 16.8 (2.7) | 72.5 (3.7) | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 5,634 | 1.8 (0.3) | 11.6 (0.9) | 12.2 (0.8) | 74.4 (0.8) | ||

| Family Income | PIR <= 1.5 | 1,717 | 1.0 (0.3) | 9.9 (1.2) | 19.0 (1.9) | 70.0 (2.1) | 0.08 |

| PIR <= 3.0 | 2,023 | 1.4 (0.3) | 12.0 (1.0) | 14.9 (1.3) | 71.7 (1.4) | ||

| PIR <= 6.0 | 3,101 | 1.8 (0.3) | 11.6 (1.0) | 12.6 (1.2) | 74.1 (1.1) | ||

| PIR > 6.0 | 3,282 | 1.8 (0.4) | 10.3 (0.7) | 13.4 (0.9) | 74.4 (1.1) | ||

| Parental education | Less than high school | 1,684 | 0.9 (0.2) | 8.5 (1.1) | 18.8 (1.6) | 71.8 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| High school grad | 3,081 | 1.5 (0.3) | 9.6 (0.7) | 17.9 (1.6) | 70.9 (1.6) | ||

| Some college | 1,998 | 2.2 (0.6) | 14.1 (1.1) | 12.3 (1.0) | 71.4 (1.3) | ||

| College grad+ | 3,360 | 1.7 (0.3) | 11.4 (0.9) | 10.3 (0.6) | 76.6 (1.2) |

NOTE: % (SE) = weighted prevalence and standard errors; p-value based on Wald χ2 test; MA = migraine with aura; MO = migraine without aura; NMH = non-migraine headache; No HA = no headache

Prevalence of lifetime mental disorders by headache subtype status are described in Table 2. The magnitude of associations is shown in Table 3. After adjusting for demographic characteristics, adolescents with headache were 2.74 (95% CI 1.94 −3.86) times more likely to meet full criteria for any mental disorder than those without headache. The associations remained significant in headache subtype group comparisons (migraine with aura vs. migraine without aura (OR 2.10, 95% CI 1.04 – 4.25); migraine headache with/without aura vs. non-migraine headache (OR 2.24, 95% CI 1.35 – 3.73). The odds of meeting criteria for mood and anxiety disorders were greater among youth with migraine headache with aura (MA) than those with migraine without aura (MO) (mood disorders, OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.38–3.10; anxiety disorders, OR 2.19, 95% CI 1.29–3.70). These disorders were also more pronounced among those with migraine (MH) than those with non-migraine headache (NMH) (mood disorders, OR 1.98, 95% CI 1.40–2.81; anxiety disorders, OR 1.90, 95% CI 1.30–2.76), and more prevalent among those with any type of headache (HA) than those without a headache history (mood disorders, OR 2.90, 95% CI 2.20–3.82; anxiety disorders, OR 2.41, 95% CI 1.95–2.98). Substance use disorders were more common among youth with migraine (MH) than those with non-migraine headache (NMH) (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1.38–3.40) and more common among those with headache than those without (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.61–2.79). Eating disorders (OR 2.06, 95% CI 1.48–2.88), and disruptive behavior disorders (OR 2.22, 95% CI 1.69–2.91) were also more likely in adolescents with headache. There was no association between headache subtypes and ADHD. When additionally controlling for other mental disorders, significant associations remained between headache and mood (OR 2.31, 95% CI 1.67 – 3.20), anxiety (OR 1.84, 95% CI 1.36 – 2.49), and behavior disorders (OR 1.52, 95% CI 1.17 – 1.98); compared to youth with non-migraine headache, youth with migraine were more likely to meet criteria for an anxiety disorder (OR 1.71, 95% CI 1.11–2.65), and less likely to meet criteria for an eating disorder (OR 0.57, 95% CI 0.35 – 0.95). In addition, the odds of co-occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders were significantly higher in migraine with aura, migraine headache, and any headache than those in their corresponding counterpart subgroups (Anxiety + Mood Disorder: MA vs MO, OR 3.69, 95% CI 2.13–6.41; MH vs NMH, OR 5.91, 95% CI 3.76–9.28; HA vs No HA, OR 4.22, 95% CI 2.92–6.09). When examining each of these three ad-hoc subtype comparisons, the magnitude of associations was greater when considering co-occurring anxiety and mood disorders than either anxiety or mood disorder alone. Associations between co-occurring anxiety and mood disorders and headache subtypes remained significant when controlling for other mental disorders (Table 3).

Table 2.

Prevalence of lifetime DSM-IV disorders by headache status, NCS-A (N=10,123)

| Lifetime DSM-IV disorder | Prevalence, % (SE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA | MO | NMH | No HA | |

| (N=10,123) | n=171 | n=1074 | n=1466 | n=7412 |

| Major depressive disorder | 27.0 (4.9) | 17.2 (1.4) | 15.6 (1.7) | 8.8 (0.6) |

| Mania | 7.2 (3.3) | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.3 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.1) |

| Hypomania | 9.0 (3.5) | 7.9 (1.2) | 3.2 (0.7) | 2.5 (0.3) |

| Mood (MDD/Mania/Hypomania) | 43.2 (5.8) | 27.0 (2.0) | 20.1 (1.9) | 12.0 (0.6) |

| Social Phobia | 18.9 (4.8) | 8.4 (1.1) | 8.2 (1.4) | 4.3 (0.4) |

| Specific Phobia | 25.0 (4.1) | 23.4 (1.5) | 19.4 (1.7) | 12.8 (0.6) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 6.7 (3.0) | 1.9 (0.5) | 0.5 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.1) |

| Panic Disorder | 15.4 (5.8) | 3.3 (0.7) | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.2) |

| Anxiety (SO/SP/GAD/PD) | 47.6 (6.1) | 29.9 (1.5) | 25.5 (2.2) | 17.0 (0.6) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 7.0 (1.9) | 12.2 (1.7) | 5.6 (1.0) | 5.8 (0.4) |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 16.5 (4.6) | 13.3 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.2) | 8.2 (0.8) |

| Nicotine Dependence | 19.8 (5.8) | 12.5 (1.7) | 7.5 (1.4) | 5.9 (0.5) |

| Substance Use (Alcohol/Drug/Nicotine) | 29.7 (6.5) | 22.2 (2.3) | 13.4 (1.5) | 12.5 (0.9) |

| Anorexia | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.2 (0.1) | 0.4 (0.2) | 0.3 (0.1) |

| Bulimia | 3.1 (1.6) | 2.3 (0.9) | 1.2 (0.3) | 0.6 (0.1) |

| Binge Eating | 10.8 (3.1) | 6.6 (1.3) | 8.3 (1.1) | 3.9 (0.4) |

| Eating (Anorexia/Bulimia/Binge) | 10.8 (3.1) | 6.8 (1.3) | 8.5 (1.2) | 4.1 (0.4) |

| (n=6,483) | n=108 | n=713 | n=890 | n=4772 |

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder a | 10.9 (5.1) | 8.3 (1.2) | 9.8 (1.5) | 9.6 (0.8) |

| Conduct Disorder a | 16.8 (4.4) | 16.9 (2.5) | 15.5 (3.7) | 9.4 (0.9) |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder a | 12.9 (5.0) | 13.5 (2.1) | 12.7 (3.8) | 5.8 (0.6) |

| Behavior (CD/ODD) a | 25.3 (5.3) | 23.4 (2.3) | 21.8 (3.6) | 12.9 (1.1) |

| Any Disorder a | 76.9 (7.1) | 62.9 (3.0) | 52.5 (2.9) | 41.2 (1.4) |

| Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorder | ||||

| (N=10,123) | n=171 | n=1074 | n=1466 | n=7412 |

| Anxiety + Mood Disorders | 26.1 (5.4) | 11.4 (1.2) | 9.2 (1.4) | 4.8 (0.3) |

| Mood disorder without anxiety | 17.2 (3.7) | 15.6 (1.8) | 11.0 (1.3) | 7.2 (0.4) |

| Anxiety disorder without mood | 21.5 (5.6) | 18.5 (1.3) | 16.4 (1.3) | 12.2 (0.6) |

| Neither anxiety nor mood disorder | 35.3 (5.2) | 54.5 (1.9) | 63.5 (2.3) | 75.8 (0.8) |

NOTE: SE=standard error; MA = migraine with aura; MO = migraine without aura; NMH = non-migraine headache; No HA=No headache;

based on parent-child paired sample n=6,483

Table 3.

Lifetime DSM-IV disorders associated with headache status, NCS-A (N=10,123)

| OUTCOME: Lifetime DSM-IV disorder | Odds Ratios, aOR (95% CI) 1 | Odds Ratios, aOR (95% CI) 2, a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MA vs MO | MH vs NMH | All HAs vs. No HA | MA vs MO | MH vs NMH | All HAs vs. No HA | |

| Major depressive disorder | 1.79 (1.14 – 2.81) | 1.37 (0.90 – 2.10) | 2.33 (1.75 – 3.11) | 1.88 (0.88 – 4.02) | 1.25 (0.71 – 2.19) | 1.99 (1.42 – 2.78) |

| Mania | 3.94 (1.34 – 11.58) | 3.03 (1.28 – 7.16) | 4.11 (2.28 – 7.42) | 2.16 (0.68 – 6.89) | 2.07 (0.49 – 8.77) | 1.98 (0.86 – 4.55) |

| Hypomania | 1.13 (0.41 – 3.11) | 2.63 (1.50 – 4.60) | 2.49 (1.66 – 3.75) | 0.72 (0.19 – 2.75) | 1.94 (0.78 – 4.82) | 1.87 (1.16 – 3.01) |

| Mood (MDD/Mania/Hypomania) | 2.06 (1.38 – 3.10) | 1.98 (1.40 – 2.81) | 2.90 (2.20 – 3.82) | 1.83 (0.96 – 3.49) | 1.66 (0.99 – 2.78) | 2.31 (1.67 – 3.20) |

| Social Phobia | 2.54 (1.37 – 4.73) | 1.67 (0.96 – 2.92) | 2.70 (2.05 – 3.55) | 1.80 (0.76 – 4.27) | 1.22 (0.60 – 2.52) | 1.84 (1.21 – 2.79) |

| Specific Phobia | 1.13 (0.72 – 1.77) | 1.40 (0.96 – 2.06) | 1.93 (1.64 – 2.27) | 0.77 (0.40 – 1.48) | 1.35 (0.85 – 2.15) | 1.40 (1.05 – 1.85) |

| Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 4.30 (1.32 – 13.96) | 7.18 (2.82 – 18.29) | 2.30 (1.51 – 3.49) | 9.62 (2.10 – 44.11) | 15.59 (4.19 – 58.07) | 1.05 (0.42 – 2.64) |

| Panic Disorder | 5.62 (1.97 – 16.07) | 3.36 (1.68 – 6.73) | 2.63 (1.74 – 3.98) | 7.35 (1.49 – 36.27) | 2.29 (0.80 – 6.59) | 1.77 (0.87 – 3.59) |

| Anxiety (SO/SP/GAD/PD) | 2.19 (1.29 – 3.70) | 1.90 (1.30 – 2.76) | 2.41 (1.95 – 2.98) | 1.91 (0.81 – 4.47) | 1.71 (1.11 – 2.65) | 1.84 (1.36 – 2.49) |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 0.55 (0.30 – 1.03) | 1.52 (0.85 – 2.72) | 1.55 (1.15 – 2.08) | 0.45 (0.16 – 1.27) | 0.85 (0.39 – 1.86) | 1.10 (0.70 – 1.72) |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 1.31 (0.66 – 2.60) | 1.69 (1.00 – 2.85) | 1.75 (1.26 – 2.43) | 1.03 (0.37 – 2.89) | 1.54 (0.88 – 2.71) | 1.23 (0.82 – 1.85) |

| Nicotine Dependence | 1.91 (0.96 – 3.83) | 2.21 (1.30 – 3.74) | 2.45 (1.72 – 3.48) | 1.27 (0.45 – 3.56) | 1.26 (0.61 – 2.60) | 1.70 (1.07 – 2.68) |

| Substance Use (Alcohol/Drug/Nicotine) | 1.58 (0.84 – 2.97) | 2.17 (1.38 – 3.40) | 2.12 (1.61 – 2.79) | 1.17 (0.41 – 3.34) | 1.46 (0.85 – 2.53) | 1.47 (0.99 – 2.19) |

| Eating (Anorexia/Bulimia/Binge) | 1.64 (0.76 – 3.58) | 1.02 (0.63 – 1.66) | 2.06 (1.48 – 2.88) | 0.88 (0.20 – 3.86) | 0.57 (0.35 – 0.95) | 1.54 (0.96 – 2.48) |

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder a | 1.24 (0.39 – 4.00) | 0.97 (0.47 – 1.97) | 1.15 (0.76 – 1.76) | 1.10 (0.39 – 3.14) | 0.88 (0.41 – 1.89) | 0.73 (0.49 – 1.07) |

| Conduct Disorder a | 1.01 (0.55 – 1.86) | 1.21 (0.62 – 2.35) | 2.03 (1.44 – 2.86) | 0.71 (0.27 – 1.84) | 0.89 (0.45 – 1.74) | 1.26 (0.85 – 1.87) |

| Oppositional Defiant Disorder a | 0.90 (0.29 – 2.79) | 1.13 (0.52 – 2.44) | 2.47 (1.62 – 3.79) | 0.60 (0.14 – 2.56) | 0.90 (0.42 – 1.94) | 1.59 (1.03 – 2.48) |

| Behavior (CD/ODD) a | 1.11 (0.58 – 2.13) | 1.28 (0.78 – 2.08) | 2.22 (1.69 – 2.91) | 0.85 (0.40 – 1.81) | 1.03 (0.68 – 1.56) | 1.52 (1.17 – 1.98) |

| Any Disorder a | 2.10 (1.04 – 4.25) | 2.24 (1.35 – 3.73) | 2.74 (1.94 – 3.86) | 2.10 (1.04 – 4.25) | 2.24 (1.35 – 3.73) | 2.74 (1.94 – 3.86) |

| Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders | ||||||

| Anxiety + Mood Disorders | 3.69 (2.13 – 6.41) | 5.91 (3.76 – 9.28) | 4.22 (2.92 – 6.09) | 4.11 (1.49 – 11.31) | 4.68 (2.47 – 8.88) | 3.46 (2.20 – 5.43) |

| Mood disorder without anxiety | 1.69 (1.01 – 2.81) | 3.64 (2.47 – 5.38) | 2.91 (2.12 – 3.97) | 1.79 (0.96 – 3.35) | 3.60 (2.29 – 5.67) | 2.83 (1.96 – 4.08) |

| Anxiety disorder without mood | 1.85 (0.90 – 3.81) | 2.82 (1.87 – 4.24) | 2.29 (1.70 – 3.10) | 1.90 (0.69 – 5.22) | 2.86 (1.73 – 4.73) | 2.21 (1.54 – 3.18) |

| Neither anxiety nor mood disorder | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference | Reference |

NOTE: Logistic regression models using Exposure= Lifetime headache status, Outcome= Lifetime DSM-IV disorder (one at a time); aOR(95% CI)

= adjusted odd ratios and 95% confidence interval, controlling for demographic characteristics (age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, parental education); aOR(95% CI)

= additionally adjusted for other lifetime DSM-IV disorders, no additional adjustment for ‘Any Disorder’; MA = migraine with aura; MO = migraine without aura; MH = migraine with/without aura; NMH = non-migraine HA; HA = headache;

based on parent-child paired sample n=6,483

Patterns of association were similar for males and females based on demographic adjusted models. However, some notable distinctions were observed in the fully adjusted models that controlled for demographic characteristics and other psychiatric disorders (Supplemental tables 1,2). Although headache was associated with mood disorder for both males (OR 1.87, 95% CI 1.06 – 3.30) and females (OR 2.68, 95% CI 1.84 −3.89), males with MA were more likely to have major depressive disorder (OR 4.64, 95% CI 1.50 – 14.35) and females with MA were more likely to report mania (OR 9.21, 95% CI 3.25 – 26.11), when compared to their MO counterparts. Headache was associated with increased odds of anxiety disorders among male (HA vs No HA: OR 2.74, 95% CI 1.74–4.32; MH vs NMH: OR 3.17, 95% CI 1.83–5.50), but not female youth. Significant associations between headache and substance use were observed only among males (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.01–2.64). Among females, significant associations between headache and eating (OR 2.04, 95% CI 1.14 – 3.64) and behavior disorders (OR 1.62, 95% CI 1.13–2.32) were observed.

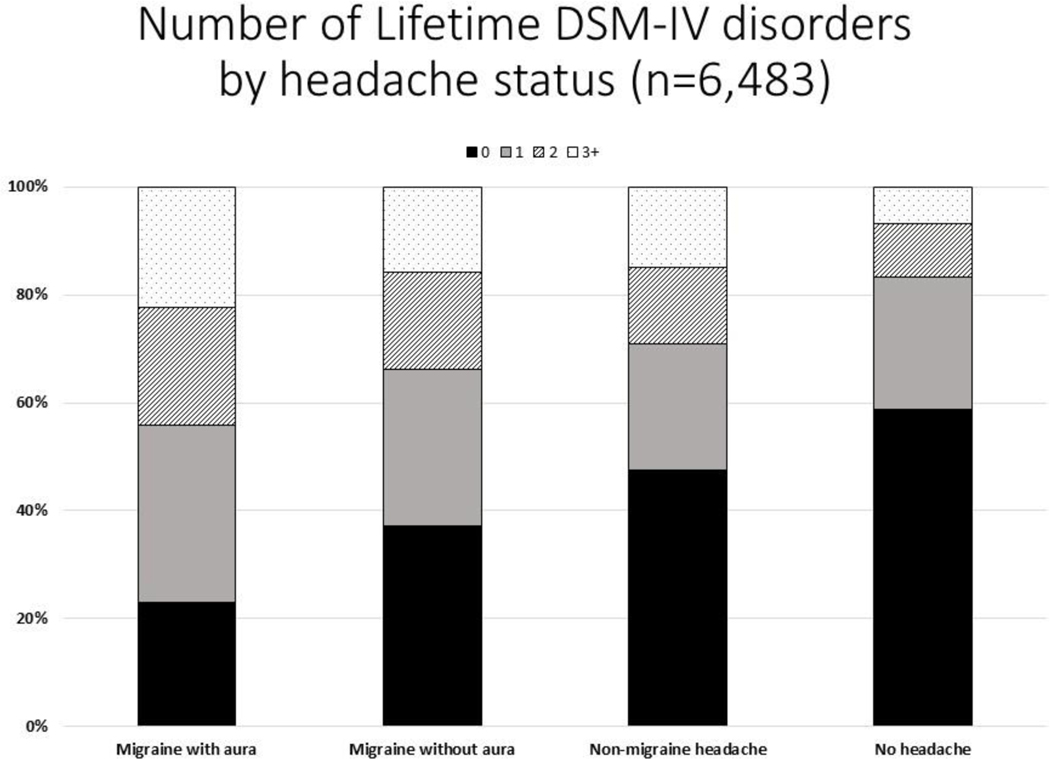

Youth with headache were also more likely to have multiple mental disorders. After adjusting for demographic variables, the number of classes of mental disorders was significantly higher among adolescents with migraine with aura than among those with migraine without aura (p=0.022), among adolescents with migraine than among those with non-migraine headache (p=0.017), and among youth with any type of headache than among youth without headache (p<0.001). (Figure 1).

Figure.

After adjusting for demographic characteristics (sex, age, race, income, parental education), the number of classes of DSM-IV disorders was significantly higher in adolescents who had migraine with aura than those who had migraine without aura (p=.1022), in adolescents who had migraine with/without aura than those with non-migraine headache (p=.017), and in adolescents reporting any headache subtype as compared to those who had no headache history (p<.001).

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the association between headache and mental disorders in a nationally representative sample of American adolescents. It represents the largest community-based study of the comorbidity of migraine specific subtypes and multiple classes of mental disorders using interview-based diagnoses and including analysis of sex-specific associations. Our results largely support previous research, including contemporaneous population-based studies, that document an association between headache, especially migraine, and mental disorders in adolescents. Associations were strongest between migraine and mood and anxiety disorders but were also found for behavior and substance use disorders and headache more generally. Patterns of association were similar among males and females, and youth with headache, particularly migraine, were more likely to suffer from multiple mental disorders.

Associations between migraine headache and mood and anxiety disorders have been observed in a multitude of studies, including clinical and community samples of adults and youth. In the current study, mood and anxiety disorders were most prevalent among youth with migraine with aura, specifically, and were more prevalent among migraine and headache sufferers than among adolescents reporting no headache history. Differences were present categorically, and at the level of individual disorders including major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, and panic disorder, as well as manic and hypomanic episodes.

Of note, our results suggest that there may be some specificity for the association between headache subtype and the combination of mood and anxiety disorders. When controlling for other mental disorders, youth with migraine faced a greater increased risk for comorbid mood and anxiety disorders than for either anxiety or mood disorder alone. Depression and anxiety are highly comorbid, and population-based studies of adults in Europe [25] and the United States [26] suggest there may be a synergistic relationship between co-occurring anxiety and depressive symptoms and migraine headache. Our results extend this finding to youth and suggest that further exploration to consider the factors underlying this association is warranted. This cross-sectional study cannot address whether shared genetic, biological, or environmental factors contribute to the development of migraine and anxiety and mood disorders, but all may play a role. Indeed, evidence suggests that serotonergic neurotransmission, long believed to be a factor in anxiety and depression, is also involved in the pathophysiology of migraine. Chronically low levels of serotonin are thought to influence activation of the trigeminovascular nocioceptive pathway implicated in migraine pain, and many abortive medications used in the treatment of migraine, such as triptans, are serotonin agonists [27, 28]. Low serotonin states are characteristic of depression, anxiety, and other mental health disorders, and medications with increase the availability on synaptic serotonin are the mainstays of pharmacotherapy.[29] Dysregulation of excitatory and inhibitory (glutaminergic & gabaergic) pathways have also been implicated in the pathophysiology of migraine and mental health disorders [30, 31].

In a previous analysis of NCS-A data, Lateef, et al, found an association between migraine and inflammatory conditions such as asthma, allergies and hay fever [19]. The link between asthma, atopy, anxiety and depression is well established and believed to be mediated by common inflammatory pathways; such pathways may contribute to the development of migraine and underlie all three broad classes of disorders [32–35]. It is also possible that migraine increases susceptibility to anxiety and depression, or vice versa. Studies to date have indeed suggested a bi-directional relationship with evidence to suggest that a history of childhood anxiety disorders are associated with migraine in young adults [36] and that depression is associated with the transition from episodic to chronic migraine [37]. Longitudinal studies designed to follow large numbers of youth over time and track the new onset of headache and mental health conditions would help to elucidate these relationships.

In addition to anxiety and mood disorders, we observed associations between migraine and substance use disorders and between headache and substance, eating, and disruptive behavior disorders. Although the evidence is mixed, associations between migraine, non-migraine headache and symptoms of externalizing disorders have been found in other studies of youth and are supported by a recent meta-analysis [9, 38]. The majority of eating disorder cases in our sample were individuals who endorsed symptoms consistent with binge eating disorder, whereas few met criteria for anorexia or bulimia. Obesity has been found to be associated with both migraine and non-migraine headache, and the current findings may reflect this association [39, 40]. The relationship between substance use and migraine is not well documented, with research suggesting that their association may be primarily attributable to a mutual overlap with mood and anxiety disorders [41]. This is likely the case in the current sample as well, as the associations between migraine and nicotine and illicit drug use no longer remained significant when controlling for other DSM-IV disorders.

Indeed, youth with headache, especially migraine, were more likely to suffer from multiple classes of mental health disorders. Similar findings have been reported in population-based studies of adults, such as the NHANES study, in which individuals with severe headache or migraine had six-fold odds of having two or more mental disorders [42]. In the current sample, youth with migraine were more likely to have multiple mental disorders than youth with non-migraine headache, and the highest rates of multiple mental disorders were reported by youth experiencing migraine with aura. The presence of multiple classes of mental disorders is generally associated with greater functional impairment and may be considered a proxy for disease severity. Indeed, the use of psychotropic medications and mental health services are higher among youth with multiple mental disorders [43, 44]. Migraine with aura is thought to be a more severe manifestation of migraine pathology. Our results, which showed that individuals with migraine with aura were more likely than those with migraine without aura to suffer from comorbid mood and anxiety disorders as well as three or more classes of psychiatric disorders, support the assertion that migraine with aura may reflect and be associated with more severe pathology. Although not well studied in youth, similar findings have previously been reported in adults, including population-based studies in Detroit and Norway which observed higher rates of depression, bipolar disorder, and co-morbid depression and anxiety among individuals with migraine with aura [11, 45].

After investigating the association between mental health disorders and headache subtypes, we also examined whether the pattern of these relationships differed between males and females. Sex differences in the prevalence rates of both mood disorders and migraine headache emerge during adolescence, and it has been postulated that hormonal effects associated with puberty may be, at least in part, associated with the rise in rates of migraine and depression among females [46, 47]. In particular, there is evidence to suggest that migraine with and without aura may be influenced by high levels or estrogen and estrogen withdrawal respectively and account for the marked increase in migraine prevalence among females observed between the ages of 10–14 years [48, 49]. We hypothesized that a shared hormonal etiology might be reflected by a stronger relationship between migraine headache and mood disorders among females than among males; however, this was not reflected by the data.

While patterns of association were largely similar, some sex differences were observed. Notably, eleven percent of females with a history of migraine with aura also reported a history of mania; rates of mania ranged from 0.6–3.4% in other subsets of the sample, reflecting population norms, and the association between MA and mania was inestimable due to its infrequent occurrence in our male sample. Previous studies have shown that migraine disproportionately affects individuals with bipolar disorder, and there is some evidence to suggest that this relationship may be particularly strong in women, although the mechanisms underlying this relationship are unknown [50]. In contrast, the association between the various headache subtypes and anxiety disorders appears to be somewhat stronger in male youth than among females. This is particularly true for migraine with aura, and while the number of males with MA in the sample is small (n=59), it may reflect the more severe nature of the aura phenotype. Although findings have been mixed in clinical samples, several population-based studies including two large scale studies examining past-week and past-month anxiety and depression symptoms in adults suggest that the association between migraine and anxiety is stronger in males than in females [25, 26].

In summary, we found an association between headache, especially migraine, and mental disorders in a population-based sample of American youth. Results were largely in keeping with the published literature, suggesting that associations are strongest between migraine and mood and anxiety disorders. Youth with migraine headache, particularly migraine with aura, are more likely to suffer from co-morbid mood and anxiety disorders, and multiple classes of psychiatric disorders, lending credence to the notion that migraine with aura may be a more severe manifestation of headache pathology and that migraine headache and mental health disorders may harbor some shared etiologic risk. Although the strength of this conclusion is limited by the cross-sectional nature of the data and the relatively small number of youth with migraine with aura, our sample is the one of the only population-based studies of youth to attempt to differentiate migraine with and without aura. The lifetime prevalence of headache in the sample was lower than rates observed in several other epidemiologic studies [51, 52], likely reflecting the fact that the WHO-CIDI interview used is intended to allow for the characterization of chronic medical conditions and captures only those youth who endorse a history of frequent or severe headaches, missing those whose headaches are both rare and mild and unlikely to be of clinical significance.

The use of WHO-CIDI interview questions, which do not directly mirror the diagnostic criteria delineated in the ICHD-III and thus do not allow for the full characterization of all headache subtypes, is a study limitation. However, the lifetime prevalence of migraine was similar to rates observed in previous studies [51, 52], suggesting that the use of modified ICHD-3 criteria, albeit a limitation, did not significantly undermine the characterization of migraine in the current sample. The classification of migraine with aura was based on reports of headache-associated visual disturbance, which is estimated to capture more than 90% of pediatric auras, but may miss some cases [21]. While the rates of migraine with aura are proportionally lower than those observed in clinical samples [53], likely reflecting a clinical referral bias, our sample captures more youth with migraine, including migraine with aura, than most clinical samples. Additional strengths of this study include the use of clinical interview to inform both headache and most mental disorders and the nationally representative, diverse sample of youth.

Future studies that prospectively track both the onset of headache and the onset of mental health disorders using ICHD-III and DSM-5 criteria would help to further elucidate the nature of the relationship between these disorders and the ways in which risk for headache and risk for mental disorders may differ between male and female adolescents. Examination of the ways in which the treatment of headache and mental health disorders may intersect and impact comorbidity is also important. Lifestyle modification, including improved sleep hygiene, maintenance of adequate fluid and food intake, regular exercise, and minimizing or managing daily life stress are first line interventions in the prevention of both migraine and tension type headache, and may impact mood and anxiety disorders in youth as well [54, 55]. Cognitive behavioral therapy, a mainstay of treatment for pediatric mood and anxiety disorders, has also shown promise in reducing headache days and disability in youth with chronic migraine [56]. Tricyclic antidepressants are often prescribed to prevent migraine in adults, but a recent placebo-controlled trial in youth found no benefit of amitriptyline over placebo with regards to reductions in migraine frequency or disability [57]. Headache is a common side effect of SSRI’s, the medication class most commonly used to treat depression and anxiety in children and adolescents, although high rates of headache among youth with depression at baseline and while treated with placebo have also been described [58]. Clinical trials of lifestyle modification, CBT, and medication therapy in youth with comorbid headaches and depression or anxiety are needed. In the meantime, pediatricians, neurologists, and other adolescent care providers should be vigilant and assess for psychiatric comorbidity when caring for youth with headache. Child psychiatrists and other mental health clinicians should be aware that headache is highly prevalent among youth with mental disorders and assess for recurrent headache symptoms which may impact mood and behavior and be associated with functional impairment.

Supplementary Material

Table s1 depicts the association between lifetime mental disorders and headache subtypes in adolescent males, adjusted for demographic characteristics (left) and demographics and other mental disorders (right). Patterns of association were similar between males and females, with unique associations between migraine headache with aura and depression and headache and anxiety and substance use disorders noted in male youth.

Table s2 depicts the association between lifetime mental disorders and headache subtypes in adolescent females, adjusted for demographic characteristics (left) and demographics and other mental disorders (right). Patterns of association were similar between males and females, with unique associations between migraine headache with aura and mania and headache and eating and behavior disorders noted in female youth.

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH, ZIAMH002808).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors report no real or potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stovner L, et al. , The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia, 2007. 27(3): p. 193–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zwart JA, et al. , The prevalence of migraine and tension-type headaches among adolescents in Norway. The Nord-Trondelag Health Study (Head-HUNT-Youth), a large population-based epidemiological study. Cephalalgia, 2004. 24(5): p. 373–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lateef TM, et al. , Headache in a national sample of American children: prevalence and comorbidity. J Child Neurol, 2009. 24(5): p. 536–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huguet A, et al. , Systematic Review of Childhood and Adolescent Risk and Prognostic Factors for Recurrent Headaches. J Pain, 2016. 17(8): p. 855–873.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powers SW, et al. , Quality of life in childhood migraines: clinical impact and comparison to other chronic illnesses. Pediatrics, 2003. 112(1 Pt 1): p. e1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merikangas KR, et al. , Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2010. 49(10): p. 980–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaycox LH, et al. , Impact of teen depression on academic, social, and physical functioning. Pediatrics, 2009. 124(4): p. e596–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merikangas KR, Contributions of epidemiology to our understanding of migraine. Headache, 2013. 53(2): p. 230–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaauw BA, et al. , Anxiety, depression and behavioral problems among adolescents with recurrent headache: the Young-HUNT study. J Headache Pain, 2014. 15: p. 38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Orr SL, et al. , Migraine and Mental Health in a Population-Based Sample of Adolescents. Can J Neurol Sci, 2017. 44(1): p. 44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Breslau N, Davis GC, and Andreski P, Migraine, psychiatric disorders, and suicide attempts: an epidemiologic study of young adults. Psychiatry Res, 1991. 37(1): p. 11–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang SJ, et al. , Migraine and suicidal ideation in adolescents aged 13 to 15 years. Neurology, 2009. 72(13): p. 1146–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang SJ, et al. , Psychiatric comorbidity and suicide risk in adolescents with chronic daily headache. Neurology, 2007. 68(18): p. 1468–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kessler RC and Ustün TB, The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 2004. 13(2): p. 93–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Merikangas K, et al. , National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): I. Background and measures. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2009. 48(4): p. 367–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, et al. , National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): II. Overview and design. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2009. 48(4): p. 380–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kessler RC, et al. , Design and field procedures in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 2009. 18(2): p. 69–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia, 2018. 38(1): p. 1–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lateef TM, et al. , Physical comorbidity of migraine and other headaches in US adolescents. J Pediatr, 2012. 161(2): p. 308–13.e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Viana M, et al. , Clinical features of visual migraine aura: a systematic review. The Journal of Headache and Pain, 2019. 20(1): p. 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balestri M, et al. , Features of aura in paediatric migraine diagnosed using the ICHD 3 beta criteria. Cephalalgia, 2018. 38(11): p. 1742–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kessler RC, et al. , National comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement (NCS-A): III. Concordance of DSM-IV/CIDI diagnoses with clinical reassessments. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2009. 48(4): p. 386–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Green JG, et al. , Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: concordance of the adolescent version of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI) with the K-SADS in the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent (NCS-A) supplement. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res, 2010. 19(1): p. 34–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-IV. 1994, American Psychiatric Association: Washington, DC: :. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lampl C, et al. , Headache, depression and anxiety: associations in the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain, 2016. 17: p. 59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Victor TW, et al. , Association between migraine, anxiety and depression. Cephalalgia, 2010. 30(5): p. 567–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hamel E, Serotonin and migraine: biology and clinical implications. Cephalalgia, 2007. 27(11): p. 1293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smitherman TA, Kolivas ED, and Bailey JR, Panic disorder and migraine: comorbidity, mechanisms, and clinical implications. Headache, 2013. 53(1): p. 23–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ressler KJ and Nemeroff CB, Role of serotonergic and noradrenergic systems in the pathophysiology of depression and anxiety disorders. Depress Anxiety, 2000. 12 Suppl 1: p. 2–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D’Andrea G. and Leon A, Pathogenesis of migraine: from neurotransmitters to neuromodulators and beyond. Neurological Sciences, 2010. 31(1): p. 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Godfrey KEM, et al. , Differences in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter levels between depressed patients and healthy controls: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res, 2018. 105: p. 33–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jiang M, Qin P, and Yang X, Comorbidity between depression and asthma via immuneinflammatory pathways: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord, 2014. 166: p. 22–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dudeney J, et al. , Anxiety in youth with asthma: A meta-analysis. Pediatr Pulmonol, 2017. 52(9): p. 1121–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg JI, Selected comorbidities of atopic dermatitis: Atopy, neuropsychiatric, and musculoskeletal disorders. Clin Dermatol, 2017. 35(4): p. 360–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bandelow B, et al. , Biological markers for anxiety disorders, OCD and PTSD: A consensus statement. Part II: Neurochemistry, neurophysiology and neurocognition. World J Biol Psychiatry, 2017. 18(3): p. 162–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Waldie KE and Poulton R, Physical and psychological correlates of primary headache in young adulthood: a 26 year longitudinal study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry, 2002. 72(1): p. 86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ashina S, et al. , Depression and risk of transformation of episodic to chronic migraine. J Headache Pain, 2012. 13(8): p. 615–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balottin U, et al. , Psychopathological symptoms in child and adolescent migraine and tension-type headache: a meta-analysis. Cephalalgia, 2013. 33(2): p. 112–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Peterlin BL, et al. , Episodic migraine and obesity and the influence of age, race, and sex. Neurology, 2013. 81(15): p. 1314–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winsvold BS, et al. , Headache, migraine and cardiovascular risk factors: the HUNT study. Eur J Neurol, 2011. 18(3): p. 504–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Peterlin BL, et al. , Post-traumatic stress disorder, drug abuse and migraine: new findings from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). Cephalalgia, 2011. 31(2): p. 235–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kalaydjian A. and Merikangas K, Physical and mental comorbidity of headache in a nationally representative sample of US adults. Psychosom Med, 2008. 70(7): p. 773–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Merikangas KR, et al. , Medication use in US youth with mental disorders. JAMA Pediatr, 2013. 167(2): p. 141–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Costello EJ, et al. , Services for adolescents with psychiatric disorders: 12-month data from the National Comorbidity Survey-Adolescent. Psychiatr Serv, 2014. 65(3): p. 359–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Oedegaard KJ, et al. , Migraine with and without aura: association with depression and anxiety disorder in a population-based study. The HUNT Study. Cephalalgia, 2006. 26(1): p. 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Macgregor EA, Rosenberg JD, and Kurth T, Sex-related differences in epidemiological and clinic-based headache studies. Headache, 2011. 51(6): p. 843–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thapar A, et al. , Depression in adolescence. Lancet, 2012. 379(9820): p. 1056–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.MacGregor EA, et al. , Incidence of migraine relative to menstrual cycle phases of rising and falling estrogen. Neurology, 2006. 67(12): p. 2154–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vetvik KG and MacGregor EA, Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol, 2017. 16(1): p. 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saunders EF, et al. , Gender differences, clinical correlates, and longitudinal outcome of bipolar disorder with comorbid migraine. J Clin Psychiatry, 2014. 75(5): p. 512–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Abu-Arafeh I, et al. , Prevalence of headache and migraine in children and adolescents: a systematic review of population-based studies. Dev Med Child Neurol, 2010. 52(12): p. 1088–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wöber-Bingöl C, Epidemiology of migraine and headache in children and adolescents. Curr Pain Headache Rep, 2013. 17(6): p. 341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Genizi J, et al. , Frequency of pediatric migraine with aura in a clinic-based sample. Headache, 2016. 56(1): p. 113–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.O’Brien HL, et al. , Treatment of pediatric migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol, 2015. 17(1): p. 326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Rabner J, et al. , Pediatric Headache and Sleep Disturbance: A Comparison of Diagnostic Groups. Headache, 2018. 58(2): p. 217–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Powers SW, et al. , Cognitive behavioral therapy plus amitriptyline for chronic migraine in children and adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. Jama, 2013. 310(24): p. 2622–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Powers SW, et al. , Trial of Amitriptyline, Topiramate, and Placebo for Pediatric Migraine. N Engl J Med, 2017. 376(2): p. 115–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Emslie G, et al. , Treatment for Adolescents with Depression Study (TADS): safety results. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry, 2006. 45(12): p. 1440–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table s1 depicts the association between lifetime mental disorders and headache subtypes in adolescent males, adjusted for demographic characteristics (left) and demographics and other mental disorders (right). Patterns of association were similar between males and females, with unique associations between migraine headache with aura and depression and headache and anxiety and substance use disorders noted in male youth.

Table s2 depicts the association between lifetime mental disorders and headache subtypes in adolescent females, adjusted for demographic characteristics (left) and demographics and other mental disorders (right). Patterns of association were similar between males and females, with unique associations between migraine headache with aura and mania and headache and eating and behavior disorders noted in female youth.